Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

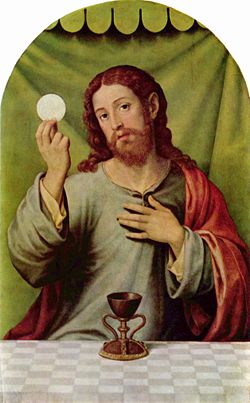

Eucharist

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Eucharist |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Eucharist (/ˈjuːkərɪst/ YOO-kər-ist; from Koine Greek: εὐχαριστία, romanized: eucharistía, lit. 'thanksgiving'), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an ordinance in others. Christians believe that the rite was instituted by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper, the night before his crucifixion, giving his disciples bread and wine. Passages in the New Testament state that he commanded them to "do this in memory of me" while referring to the bread as "my body" and the cup of wine as "the blood of my covenant, which is poured out for many".[1][2] According to the synoptic Gospels, this was at a Passover meal.[3]

The elements of the Eucharist, sacramental bread—either leavened or unleavened—and sacramental wine (among Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox) or non-alcoholic grape juice (among Methodists, Baptists and Plymouth Brethren), are consecrated on an altar or a communion table and consumed thereafter. The consecrated elements are the end product of the Eucharistic Prayer.[4]

Christians generally recognize a special presence of Christ in this rite, though they differ about exactly how, where, and when Christ is present. The Catholic Church states that the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ under the species of bread and wine. It maintains that by the consecration, the substances of the bread and wine actually become the substances of the body and blood of Christ (transubstantiation) while the form and appearances of the bread and wine remain unaltered (e.g. colour, taste, feel, and smell). The Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches agree that an objective change occurs of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. Lutherans believe the true body and blood of Christ are really present "in, with, and under" the forms of the bread and wine, known as the sacramental union.[5] Reformed Christians believe in a real spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[6] Anglican eucharistic theologies universally affirm the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, though Evangelical Anglicans believe that this is a spiritual presence, while Anglo-Catholics hold to a corporeal presence.[7][8] Others, such as the Plymouth Brethren, hold the Lord's Supper to be a memorial in which believers are "one with Him".[9][10] As a result of these different understandings, "the Eucharist has been a central issue in the discussions and deliberations of the ecumenical movement."[3]

Terminology

[edit]

Eucharist

[edit]The New Testament was originally written in the Greek language and the Greek noun εὐχαριστία (eucharistia), meaning "thanksgiving", appears a few times in it,[12] while the related Greek verb εὐχαριστήσας is found several times in New Testament accounts of the Last Supper,[13][14][15][16][17] including the earliest such account:[14]

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks (εὐχαριστήσας), he broke it, and said, "This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me".

— 1 Corinthians 11:23–24[18]

The term eucharistia (thanksgiving) is that by which the rite is referred to[14] in the Didache (a late 1st or early 2nd century document),[19]: 51 [20][21]: 437 [22]: 207 by Ignatius of Antioch (who died between 98 and 117)[21][23] and by Justin Martyr (First Apology written between 155 and 157).[24][21][25] Today, "the Eucharist" is the name still used by Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholics, Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Lutherans. Other Protestant denominations rarely use this term, preferring "Communion", "the Lord's Supper", "Remembrance", or "the Breaking of Bread". Latter-day Saints call it "the Sacrament".[26]

Lord's Supper

[edit]In the First Epistle to the Corinthians Paul uses the term "Lord's Supper", in Greek Κυριακὸν δεῖπνον (Kyriakon deipnon), in the early 50s of the 1st century:[14][15]

When you come together, it is not the Lord's Supper you eat, for as you eat, each of you goes ahead without waiting for anybody else. One remains hungry, another gets drunk.

— 1 Corinthians 11:20–21[27]

The term "Lord's Supper" came into popular use after the Protestant Reformation and remains the predominant term among certain Evangelicals, such as Baptists and Pentecostals.[28]: 123 [29]: 259 [30]: 371

Communion

[edit]Use of the term Communion (or Holy Communion) to refer to the Eucharistic rite began by some groups originating in the Protestant Reformation. Others, such as the Catholic Church, do not formally use this term for the rite, but instead mean by it the act of partaking of the consecrated elements;[31] they speak of receiving Holy Communion at Mass or outside of it, they also use the term First Communion when one receives the Eucharist for the first time. The term Communion is derived from Latin communio ("sharing in common"), translated from the Greek κοινωνία (koinōnía) in 1 Corinthians 10:16:

The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ?

— 1 Corinthians 10:16

Other terms

[edit]Breaking of bread

[edit]The phrase κλάσις τοῦ ἄρτου (klasis tou artou, 'breaking of the bread'; in later liturgical Greek also ἀρτοκλασία artoklasia) appears in various related forms five times in the New Testament[32] in contexts which, according to some, may refer to the celebration of the Eucharist, in either closer or symbolically more distant reference to the Last Supper.[33] This term is used by the Plymouth Brethren.[34]

Sacrament or Blessed Sacrament

[edit]The "Blessed Sacrament", the "Sacrament of the Altar", and other variations, are common terms used by Catholics,[35] Lutherans[36] and some Anglicans (Anglo-Catholics)[37] for the consecrated elements, particularly when reserved in a tabernacle. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints the term "The Sacrament" is used of the rite.[26]

Mass

[edit]The term "Mass" is used in the Catholic Church, the Lutheran churches (especially the Churches of Sweden, Norway and Finland), and by some Anglicans. It derives from the Latin word missa, a dismissal: "Ite missa est", or "go, it is sent", the very last phrase of the service.[38] That Latin word has come to imply "mission" as well because the congregation is sent out to serve Christ.[39]

At least in the Catholic Church, the Mass is a long rite in two parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The former consists of readings from the Bible and a homily, or sermon, given by a priest or deacon. The latter, which follows seamlessly, includes the "Offering" of the bread and wine at the altar, their consecration by the priest through prayer, and their reception by the congregation in Holy Communion.[40] Among the many other terms used in the Catholic Church are "Holy Mass", "the Memorial of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of the Lord", the "Holy Sacrifice of the Mass", and the "Holy Mysteries".[41]

Divine Liturgy and Divine Service

[edit]The term Divine Liturgy (Ancient Greek: Θεία Λειτουργία) is used in Byzantine Rite traditions, whether in the Eastern Orthodox Church or among the Eastern Catholic Churches. These also speak of "the Divine Mysteries", especially in reference to the consecrated elements, which they also call "the Holy Gifts".[a]

The term Divine Service (German: Gottesdienst) has often been used to refer to Christian worship more generally and is still used in Lutheran churches, in addition to the terms "Eucharist", "Mass" and "Holy Communion".[42] Historically this refers (like the term "worship" itself) to service of God, although more recently it has been associated with the idea that God is serving the congregants in the liturgy.[43]

Other Eastern rites

[edit]Some Eastern rites have yet more names for the Eucharist. Holy Qurbana is common in Syriac Christianity and Badarak[44] in the Armenian Rite; in the Alexandrian Rite, the term prosphora (from the Greek προσφορά) is common in Coptic Christianity and Keddase in Ethiopian and Eritrean Christianity.[45]

History

[edit]

Biblical basis

[edit]The Last Supper appears in all three synoptic Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke. It also is found in the First Epistle to the Corinthians,[3][46][47] which suggests how early Christians celebrated what Paul the Apostle called the Lord's Supper. Although the Gospel of John does not reference the Last Supper explicitly, some argue that it contains theological allusions to the early Christian celebration of the Eucharist, especially in the chapter 6 Bread of Life Discourse but also in other passages.[48]

Gospels

[edit]The synoptic Gospels, Mark 14:22–25,[49] Matthew 26:26–29[50] and Luke 22:13–20[51] depict Jesus as presiding over the Last Supper prior to his crucifixion. The versions in Matthew and Mark are almost identical,[52] but the Gospel of Luke presents a textual difference, in that a few manuscripts omit the second half of verse 19 and all of verse 20 ("given for you […] poured out for you"), which are found in the vast majority of ancient witnesses to the text.[53] If the shorter text is the original one, then Luke's account is independent of both that of Paul and that of Matthew/Mark. If the majority longer text comes from the author of the third gospel, then this version is very similar to that of Paul in 1 Corinthians, being somewhat fuller in its description of the early part of the Supper,[54] particularly in making specific mention of a cup being blessed before the bread was broken.[55]

In the one prayer given to posterity by Jesus, the Lord's Prayer, the word epiousion—which is otherwise unknown in Classical Greek literature—was interpreted by some early Christian writers as meaning "super-substantial", and hence a possible reference to the Eucharist as the Bread of Life.[56]

In the Gospel of John, however, the account of the Last Supper does not mention Jesus taking bread and "the cup" and speaking of them as his body and blood; instead, it recounts other events: his humble act of washing the disciples' feet, the prophecy of the betrayal, which set in motion the events that would lead to the cross, and his long discourse in response to some questions posed by his followers, in which he went on to speak of the importance of the unity of the disciples with him, with each other, and with God.[57][58] Some would find in this unity and in the washing of the feet the deeper meaning of the Communion bread in the other three Gospels.[59] In John 6:26–65,[60] a long discourse is attributed to Jesus that deals with the subject of the living bread; John 6:51–59[61] also contains echoes of Eucharistic language.

First Epistle to the Corinthians

[edit]1 Corinthians 11:23–25[62] gives the earliest recorded description of Jesus' Last Supper: "The Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, 'This is my body, which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.'" The Greek word used in the passage for 'remembrance' is ἀνάμνησιν (anamnesis), which itself has a much richer theological history than the English word "remember".

The expression "The Lord's Supper", derived from Paul's usage in 1 Corinthians 11:17–34,[63] may have originally referred to the Agape feast (or love feast), the shared communal meal with which the Eucharist was originally associated.[64] The Agape feast is mentioned in Jude 12[65] but "The Lord's Supper" is now commonly used in reference to a celebration involving no food other than the sacramental bread and wine.

Early Christian sources

[edit]The Didache (Greek: Διδαχή, "teaching") is an Early Church treatise that includes instructions for baptism and the Eucharist. Most scholars date it to the late 1st century,[66] and distinguish in it two separate Eucharistic traditions, the earlier tradition in chapter 10 and the later one preceding it in chapter 9.[67][b] The Eucharist is mentioned again in chapter 14.[c]

Ignatius of Antioch (born c. 35 or 50, died between 98 and 117), one of the Apostolic Fathers,[d] mentions the Eucharist as "the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ":

They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again. [...] Let that be deemed a proper Eucharist, which is [administered] either by the bishop, or by one to whom he has entrusted it.

— Smyrnaeans, 7–8[69]

Take heed, then, to have but one Eucharist. For there is one flesh of our Lord Jesus Christ, and one cup to [show forth ] the unity of His blood; one altar; as there is one bishop, along with the presbytery and deacons, my fellow-servants: that so, whatsoever you do, you may do it according to [the will of] God.

— Philadephians, 4[70]

Justin Martyr (born c. 100, died c. 165) mentions in this regard:

And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.[71][72]

Paschasius Radbertus (785–865) was a Carolingian theologian, and the abbot of Corbie, whose best-known and influential work is an exposition on the nature of the Eucharist written around 831, entitled De Corpore et Sanguine Domini. In it, Paschasius agrees with St Ambrose in affirming that the Eucharist contains the true, historical body of Jesus Christ. According to Paschasius, God is truth itself, and therefore, his words and actions must be true. Christ's proclamation at the Last Supper that the bread and wine were his body and blood must be taken literally, since God is truth.[73]: 9 He thus believes that the transubstantiation of the bread and wine offered in the Eucharist really occurs. Only if the Eucharist is the actual body and blood of Christ can a Christian know it is salvific.[73]: 10 [e]

Jews and the Eucharist

[edit]The concept of the Jews both destroying and partaking in some perverted version of the Eucharist has been a vessel to promote anti-Judaism and anti-Jewish ideology and violence. In medieval times, Jews were often depicted stabbing or in some other way physically harming communion wafers.[citation needed] These characterizations drew parallels to the idea that the Jews killed Christ; murdering this transubstantiation or "host" was thought of as a repetition of the event. Jewish people's eagerness to destroy hosts were also a variation of blood libel charges, with Jews being accused of murdering bodies of Christ, whether they be communion wafers or Christian children. The blood libel charges and the concept of Eucharist are also related in the belief that blood is efficacious, meaning it has some sort of divine power.[74]

Eucharistic theology

[edit]Most Christians, even those who deny that there is any real change in the elements used, recognize a special presence of Christ in this rite. However, Christians differ about exactly how, where and how long Christ is present in it.[3] Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Church of the East teach that the reality (the "substance") of the elements of bread and wine is wholly changed into the body and blood of Jesus Christ, while the appearances (the "species") remain. Transubstantiation ("change of the substance") is the term used by Catholics to denote what is changed, not to explain how the change occurs, since the Catholic Church teaches that "the signs of bread and wine become, in a way surpassing understanding, the Body and Blood of Christ".[75] The Orthodox use various terms such as transelementation, but no explanation is official as they prefer to leave it a mystery.

Lutherans believe Christ to be "truly and substantially present" with the bread and wine that are seen in the Eucharist,[76] in a manner referred to as the sacramental union. They attribute the real presence of Jesus' living body to his word spoken in the Eucharist, and not to the faith of those receiving it. They also believe that "forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation" are given through the words of Christ in the Eucharist to those who believe his words ("given and shed for you").[77]

Reformed Christians also believe Christ to be present in the Eucharist, but describe this presence as a spiritual presence, not a physical one.[78] Anglicans adhere to a range of views depending on churchmanship although the teaching in the Anglican Thirty-Nine Articles also holds that the body of Christ is received by the faithful only in a heavenly and spiritual manner, a doctrine also taught in the Methodist Articles of Religion.[79]

Christians adhering to the theology of Memorialism, such as the Anabaptist Churches, do not believe in the concept of the real presence, believing that the Eucharist is only a ceremonial remembrance or memorial of the death of Christ.[80]

The Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document of the World Council of Churches,[81] attempting to present the common understanding of the Eucharist on the part of the generality of Christians, describes it as "essentially the sacrament of the gift which God makes to us in Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit", "Thanksgiving to the Father", "Anamnesis or Memorial of Christ", "the sacrament of the unique sacrifice of Christ, who ever lives to make intercession for us", "the sacrament of the body and blood of Christ, the sacrament of his real presence", "Invocation of the Spirit", "Communion of the Faithful", and "Meal of the Kingdom".

Ritual and liturgy

[edit]Many Christian denominations classify the Eucharist as a sacrament.[f] Anabaptists usually refer to the Lord's Supper as being an ordinance, viewing it as an expression of faith and of obedience to Christ, though Anabaptists have used the word sacrament interchangeably with the word ordinance.[83]

Catholic Church

[edit]

In the Catholic Church the Eucharist is considered as a sacrament, according to the church the Eucharist is "the source and summit of the Christian life".[84] "The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it. For in the blessed Eucharist is contained the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ himself, our Pasch."[85] ("Pasch" is a word that sometimes means Easter, sometimes Passover.)[86]

As a sacrifice

[edit]In the Eucharist the same sacrifice that Jesus made only once on the cross is believed to be made present at every Mass. According to Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Eucharist is the very sacrifice of the Body and Blood of the Lord Jesus which he instituted to perpetuate the sacrifice of the cross throughout the ages until his return in glory."[87]

"When the Church celebrates the Eucharist, she commemorates Christ's Passover, and it is made present the sacrifice Christ offered once for all on the cross remains ever present. [...] The Eucharist is thus a sacrifice because it re-presents (makes present) the same and only sacrifice offered once for all on the cross"[88]

The sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Eucharist are considered as one single sacrifice: "The victim is one and the same: the same now offers through the ministry of priests, who then offered himself on the cross; only the manner of offering is different."[89] In the holy sacrifice of the Mass, "it is Christ himself, the eternal high priest of the New Covenant who, acting through the ministry of the priests, offers the Eucharistic sacrifice. And it is the same Christ, really present under the species of bread and wine, who is the offering of the Eucharistic sacrifice."[90]

As a real presence

[edit]

According to the Catholic Church Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist in a true, real and substantial way, with his body, blood, soul and divinity.[91] By the consecration, the substances of the bread and wine actually become the substances of the body and blood of Christ (transubstantiation) while the appearances or "species" of the bread and wine remain unaltered (e.g. colour, taste, feel, and smell). This change is brought about in the eucharistic prayer through the efficacy of the word of Christ and by the action of the Holy Spirit.[92][93][94] The Eucharistic presence of Christ begins at the moment of the consecration and endures as long as the Eucharistic species subsist,[95][96] that is, until the Eucharist is digested, physically destroyed, or decays by some natural process[97] (at which point, theologian Thomas Aquinas argued, the substance of the bread and wine cannot return).[98]

The Fourth Council of the Lateran in 1215 spoke of the bread and wine as "transubstantiated" into the body and blood of Christ: "His body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine, the bread and wine having been transubstantiated, by God's power, into his body and blood".[g][101] In 1551, the Council of Trent definitively declared: "Because Christ our Redeemer said that it was truly his body that he was offering under the species of bread,[102] it has always been the conviction of the Church of God, and this holy Council now declares again that by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation."[103][104][105]

The church holds that the body and blood of Jesus can no longer be truly separated. Where one is, the other must be. Therefore, although the priest (or extraordinary minister of Holy Communion) says "The Body of Christ" when administering the Host and "The Blood of Christ" when presenting the chalice, the communicant who receives either one receives Christ, whole and entire. "Christ is present whole and entire in each of the species and whole and entire in each of their parts, in such a way that the breaking of the bread does not divide Christ."[106]

The Catholic Church sees as the main basis for this belief the words of Jesus himself at his Last Supper: the synoptic Gospels[107] and Paul's recount that Jesus at the time of taking the bread and the cup said: "This is my body […] this is my blood."[108] The Catholic understanding of these words, from the Patristic authors onward, has emphasized their roots in the covenantal history of the Old Testament. The interpretation of Christ's words against this Old Testament background coheres with and supports belief in the Real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[109]

Reception and devotions

[edit]According to the Catholic Church doctrine receiving the Eucharist in a state of mortal sin is a sacrilege[110] and only those who are in a state of grace, that is, without any mortal sin, can receive it.[111] Based on 1 Corinthians 11:27–29, it affirms the following: "Anyone who is aware of having committed a mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion, even if he experiences deep contrition, without having first received sacramental absolution, unless he has a grave reason for receiving Communion and there is no possibility of going to confession."[112][113]

Since the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ, "the worship due to the sacrament of the Eucharist, whether during the celebration of the Mass or outside it, is the worship of latria, that is, the adoration given to God alone.""[114] The Blessed Sacrament can be exposed (displayed) on an altar in a monstrance. Rites involving the exposure of the Blessed Sacrament include Benediction and eucharistic adoration. According to Catholic theology, the host, after the Rite of Consecration, is no longer bread, but is the Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity of Christ. Catholics believe that Jesus is the sacrificial Lamb of God prefigured in the Old Testament Passover. The flesh of that Passover sacrificial lamb was to be consumed by the family members. Any left overs were to be burned before daybreak so that none of the Passover Lamb's flesh remained. Only by marking the doorposts and lintel of one's home with the Blood of the Lamb were the members of the household saved from death. The consumption of the Lamb was not to save them but rather to give them energy for the journey of escape (Exodus = escape from slavery in Egypt) as was also true for the unleavened bread (Exodus 12:3–13) As the Passover was the Old Covenant, so the Eucharist became the New Covenant. (Matthew 26:26–28, Mark 14:22–24, Luke 22: 19–20, and John 6:48–58)

Eastern Orthodoxy

[edit]

Within Eastern Christianity, the Eucharistic service is called the "Divine Liturgy" (Byzantine Rite) or similar names in other rites. It comprises two main divisions: the first is the "Liturgy of the Catechumens" which consists of introductory litanies, antiphons and scripture readings, culminating in a reading from one of the Gospels and, often, a homily; the second is the "Liturgy of the Faithful" in which the Eucharist is offered, consecrated, and received as Holy Communion. Within the latter, the actual Eucharistic prayer is called the anaphora, (literally "offering" or "carrying up", from the Greek ἀνα- + φέρω). In the Rite of Constantinople, two different anaphoras are currently used: one is attributed to John Chrysostom, the other to Basil the Great.

. In the Oriental Orthodox Church, a variety of anaphoras are used, but all are similar in structure to those of the Constantinopolitan Rite, in which the Anaphora of Saint John Chrysostom is used most days of the year; Saint Basil's is offered on the Sundays of Great Lent, the eves of Christmas and Theophany, Holy Thursday, Holy Saturday, and upon his feast day (1 January). At the conclusion of the Anaphora, the bread and wine are held to be the body and blood of Christ. Unlike the Latin Church, the Byzantine Rite uses leavened bread, with the leaven symbolizing the presence of the Holy Spirit.[115] The Greek Orthodox Church utilizes leavened bread in their celebration and requires parishioners to recite The Kanon of Preparation to Receive Holy Communion before receiving communion.[116]

In Eastern theology, one idea of consecration as a process has been suggested. This understands the change in the elements to be accomplished at the epiclesis ("invocation") by which the Holy Spirit is invoked and the consecration of the bread and wine as the genuine body and blood of Christ is specifically requested, but since the anaphora as a whole is considered a unitary (albeit lengthy) prayer, no one moment within it can readily be singled out.[117]

Protestantism

[edit]Anabaptists

[edit]Anabaptist denominations, such as the Mennonites and German Baptist Brethren Churches like the Church of the Brethren churches and congregations have the Agape feast, footwashing, as well as the serving of the bread and wine in the celebration of the Lovefeast. In the more modern groups, Communion is only the serving of the Lord's Supper. In the communion meal, the members of the Mennonite churches renew their covenant with God and with each other.[118]

Moravian/Hussite

[edit]The Moravian Church adheres to a view known as the "sacramental presence",[119] teaching that in the sacrament of Holy Communion:[120]

Christ gives his body and blood according to his promise to all who partake of the elements. When we eat and drink the bread and the wine of the Supper with expectant faith, we thereby have communion with the body and blood of our Lord and receive the forgiveness of sins, life, and salvation. In this sense, the bread and wine are rightly said to be Christ's body and blood which he gives to his disciples.[120]

Nicolaus Zinzendorf, a bishop of the Moravian Church, stated that Holy Communion is the "most intimate of all connection with the person of the Saviour."[121] The Order of Service for the observance of the Lord's Supper includes a salutation, hymns, the right hand of fellowship, prayer, consecration of the elements, distribution of the elements, partaking of the elements, and a benediction.[122] Moravian Christians traditionally practice footwashing before partaking in the Lord's Supper, although in certain Moravian congregations, this rite is observed chiefly on Maundy Thursday.[123][124]

Anglican

[edit]

Anglican theology on the matter of the Eucharist is nuanced. The Eucharist is neither wholly a matter of transubstantiation nor simply devotional and memorialist in orientation. The Anglican churches do not adhere to the belief that the Lord's Supper is merely a devotional reflection on Christ's death. For some Anglicans, Christ is spiritually present in the fullness of his person in the Eucharist.

The Church of England itself has repeatedly refused to make official any definition of "the presence of Christ". Church authorities prefer to leave it a mystery while proclaiming the consecrated bread and wine to be "spiritual food" of "Christ's Most Precious Body and Blood"; the bread and wine are an "outward sign of an inner grace".[125]: 859 The words of administration at communion allow for real presence or for a real but spiritual presence (Calvinist receptionism and virtualism). This concept was congenial to most Anglicans well into the 19th century.[126] From the 1840s, the Tractarians reintroduced the idea of "the real presence" to suggest a corporeal presence, which could be done since the language of the BCP rite referred to the body and blood of Christ without details as well as referring to these as spiritual food at other places in the text. Both are found in the Latin and other rites, but in the former, a definite interpretation as corporeal is applied.

Both receptionism and virtualism assert the real presence. The former places emphasis on the recipient and the latter states "the presence" is confected by the power of the Holy Spirit but not in Christ's natural body. His presence is objective and does not depend on its existence from the faith of the recipient. The liturgy petitions that elements "be" rather than "become" the body and blood of Christ leaving aside any theory of a change in the natural elements: bread and wine are the outer reality and "the presence" is the inner invisible except as perceived in faith.[127]: 314–324

In 1789, the Episcopal Church in the United States restored explicit language that the Eucharist is an oblation (sacrifice) to God. Subsequent revisions of the Book of Common Prayer by member churches of the Anglican Communion have done likewise (the Church of England did so in the proposed 1928 prayer book).[128]: 318–324

The so-called "Black Rubric" in the 1552 prayer book, which allowed kneeling when receiving Holy Communion was omitted in the 1559 edition at Queen Elizabeth I's insistence. It was reinstated in the 1662 prayer book, modified to deny any corporal presence of Christ's natural flesh and blood, which are in Heaven and not here. [citation needed]

Baptists

[edit]

The bread and "fruit of the vine" indicated in Matthew, Mark and Luke as the elements of the Lord's Supper[129] are interpreted by many Baptists as unleavened bread (although leavened bread is often used) and, in line with the historical stance of some Baptist groups (since the mid-19th century) against partaking of alcoholic beverages, grape juice, which they commonly refer to simply as "the Cup".[130] The unleavened bread also underscores the symbolic belief attributed to Christ's breaking the bread and saying that it was his body.

Some Baptists, such as certain Independent Baptist congregations, consider the Communion to be primarily an act of remembrance of Christ's atonement, and a time of renewal of personal commitment (memorialism),[131][132] while others, such as Reformed Baptists (Calvinistic Baptists) affirm the Reformed doctrine of a pneumatic presence,[133] which is expressed in confessions of faith such as the Second London Baptist Confession, specifically in Chapter 30, Articles 3 and 7. As such, those within the Founders movement (a Calvinistic movement among the Southern Baptist Convention) adhere to the real spiritual presence.[133] Apart from the Reformed Baptists, there are certain General Baptists adhere to the view of the real spiritual presence of Christ in the Lord's Supper, which was taught in Helwys Confession (1611).[134]

Communion practices and frequency vary among congregations. A typical practice among some Baptists is to have small cups of juice and plates of broken bread distributed to the seated congregation. In other congregations, especially the more traditional ones, communicants may proceed to the altar or communion table to receive the elements, then return to their pews. A widely accepted practice is for all to receive and hold the elements until everyone is served, then consume the bread and cup in unison. Usually, hymns are performed and Scripture such as the precise verses of Jesus speaking at the Last Supper is read during the receiving of the elements.

Some Baptist churches are closed-Communionists (even requiring full membership in the local church congregation before partaking), with others being partially or fully open-Communionists. Adults and children in attendance who have not received baptism are expected to not participate.

Lutheran

[edit]

Lutherans believe that the body and blood of Christ are "truly and substantially present in, with, and under the forms" of the consecrated bread and wine (the elements), so that communicants eat and drink the body and blood of Christ himself as well as the bread and wine in the Eucharistic sacrament.[135] The Lutheran doctrine of the Real Presence is more accurately and formally known as the "sacramental union".[136][137] Others have erroneously called this consubstantiation, a Lollardist doctrine, though this term is specifically rejected by Lutheran churches and theologians since it creates confusion about the actual doctrine and subjects the doctrine to the control of a non-biblical philosophical concept in the same manner as, in their view, does the term "transubstantiation".[138]

In the Church of Sweden, the Eucharist is celebrated at least every Sunday, with some churches offering it daily, as with monasteries and convents.[139] There is in Lutheran congregations, a movement to celebrate Eucharist weekly, though it was historically common for congregations to celebrate the Eucharist monthly or even quarterly.[140][141] Even in congregations where Eucharist is offered weekly, there is not a requirement that every church service be a Eucharistic service, nor that all members of a congregation must receive it weekly.[142]

Open Brethren and Exclusive Brethren

[edit]Among Open assemblies, also termed Plymouth Brethren, the Eucharist is more commonly called the Breaking of Bread or the Lord's Supper. They believe it is only a symbolic reenactment of the Last Supper and a memorial "to remind believers of his body given and his blood shed for their salvation".[9][143] and is central to the worship of both individual and assembly.[144]: 375 In principle, the service is open to all baptized Christians, but an individual's eligibility to participate depends on the views of each particular assembly. The service takes the form of non-liturgical, open worship with all male participants allowed to pray audibly and select hymns or readings. The breaking of bread itself typically consists of one leavened loaf, which is prayed over and broken by a participant in the meeting[145]: 279–281 and then shared around. The wine is poured from a single container into one or several vessels, and these are again shared around.[146]: 375 [147]

The Exclusive Brethren follow a similar practice to the Open Brethren. They also call the Eucharist the Breaking of Bread or the Lord's Supper.[144]

Reformed (Continental Reformed, Presbyterian and Congregationalist)

[edit]In the Reformed tradition (which includes the Continental Reformed Churches, the Presbyterian Churches, and the Congregationalist Churches), the Eucharist is variously administered. The Calvinist view of the Sacrament sees a real presence of Christ in the supper which differs both from the objective ontological presence of the Catholic view, and from the real absence of Christ and the mental recollection of the memorialism of the Zwinglians[148]: 189 and their successors.

The bread and wine become the means by which the believer has real communion with Christ in his death and Christ's body and blood are present to the faith of the believer as really as the bread and wine are present to their senses but this presence is "spiritual", that is the work of the Holy Spirit.[149] There is no standard frequency; John Calvin desired weekly communion, but the city council only approved monthly, and monthly celebration has become the most common practice in Reformed churches today.

Many, on the other hand, follow John Knox in celebration of the Lord's supper on a quarterly basis, to give proper time for reflection and inward consideration of one's own state and sin. Recently, Presbyterian and Reformed Churches have been considering whether to restore more frequent communion, including weekly communion in more churches, considering that infrequent communion was derived from a memorialist view of the Lord's Supper, rather than Calvin's view of the sacrament as a means of grace.[150] Some churches use bread without any raising agent (whether yeast or another leaven.) in view of the use of unleavened bread at Jewish Passover meals, while others use any bread available.

The Presbyterian Church (USA), for instance, prescribes "bread common to the culture". Harking back to the regulative principle of worship, the Reformed tradition had long eschewed coming forward to receive communion, preferring to have the elements distributed throughout the congregation by the presbyters (elders) more in the style of a shared meal. Over the last half a century it is much more common in Presbyterian churches to have Holy Communion monthly or on a weekly basis. It is also becoming common to receive the elements by intinction (receiving a piece of consecrated bread or wafer, dipping it in the blessed wine, and consuming it). Wine and grape juice are both used, depending on the congregation.[151][152] Most Reformed churches practice "open communion", i.e., all believers who are united to a church of like faith and practice, and who are not living in sin, would be allowed to join in the Sacrament.

Methodist

[edit]

The British Catechism for the use of the people called Methodists states that, "[in the Eucharist] Jesus Christ is present with his worshipping people and gives himself to them as their Lord and Saviour".[153] Methodist theology of this sacrament is reflected in one of the fathers of the movement, Charles Wesley, who wrote a Eucharistic hymn with the following stanza:[154]

We need not now go up to Heaven,

To bring the long sought Saviour down;

Thou art to all already given,

Thou dost e'en now Thy banquet crown:

To every faithful soul appear,

And show Thy real presence here!

Reflecting Wesleyan covenant theology, Methodists also believe that the Lord's Supper is a sign and seal of the covenant of grace.[155][156]

In many Methodist denominations, non-alcoholic wine (grape juice) is used, so as to include those who do not take alcohol for any reason, as well as a commitment to the Church's historical support of temperance.[157][158] Variations of the Eucharistic Prayer are provided for various occasions, including communion of the sick and brief forms for occasions that call for greater brevity. Though the ritual is standardized, there is great variation amongst Methodist churches, from typically high-church to low-church, in the enactment and style of celebration. Methodist clergy are not required to be vested when celebrating the Eucharist.

John Wesley, a founder of Methodism, said that it was the duty of Christians to receive the sacrament as often as possible. Methodists in the United States are encouraged to celebrate the Eucharist every Sunday, though it is typically celebrated on the first Sunday of each month, while a few go as long as celebrating quarterly (a tradition dating back to the days of circuit riders that served multiple churches). Communicants may receive standing, kneeling, or while seated. Gaining more wide acceptance is the practice of receiving by intinction (receiving a piece of consecrated bread or wafer, dipping it in the blessed wine, and consuming it). The most common alternative to intinction is for the communicants to receive the consecrated juice using small, individual, specially made glass or plastic cups known as communion cups.[159] The United Methodist Church practices open communion (which it describes as an "open table"), inviting "all who intend a Christian life, together with their children" to receive the eucharistic elements.[160] The Doctrines and Discipline of the Methodist Church specifies, on days during which Holy Communion is celebrated, that "Upon entering the church let the communicants bow in prayer and in the spirit of prayer and meditation approach the Blessed Sacrament."[161]

Nondenominational Christians

[edit]

Many non-denominational Christians, including the Churches of Christ, receive communion every Sunday. Others, including Evangelical churches such as the Church of God and Calvary Chapel, typically receive communion on a monthly or periodic basis. Many non-denominational Christians hold to the Biblical autonomy of local churches and have no universal requirement among congregations.

Some Churches of Christ, among others, use grape juice and unleavened wafers or unleavened bread and practice open communion.

Syriac Christianity

[edit]Edessan Rite (Church of the East)

[edit]Holy Qurbana or Qurbana Qaddisha, the "Holy Offering" or "Holy Sacrifice", refers to the Eucharist as celebrated according to the East Syriac Christianity. The main Anaphora of the East Syrian tradition is the Holy Qurbana of Addai and Mari.

Syro-Antiochene Rite (West Syriac)

[edit]Holy Qurobo or Qurobo Qadisho refers to the Eucharist as celebrated in the West Syrian traditions of Syriac Christianity, while that of the West Syrian tradition is the Liturgy of Saint James.

Both are extremely old, going back at least to the third century, and are the oldest extant liturgies continually in use.

Restorationism

[edit]Irvingian

[edit]In the Irvingian Churches, Holy Communion, along with Holy Baptism and Holy Sealing, is one of the three sacraments.[162][163] It is the focus of the Divine Service in the liturgies of Irvingism.[164]

Edward Irving, who founded the Irvingian Churches, such as the New Apostolic Church, taught the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, emphasizing "the humiliated humanity of Christ in the Lord's Supper."[165][166][167] Additionally, the Irvingian Churches affirm the "real presence of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ in Holy Communion":[167]

Jesus Christ is in the midst of the congregation as the crucified, risen, and returning Lord. Thus His once-brought sacrifice is also present in that its effect grants the individual access to salvation. In this way, the celebration of Holy Communion causes the partakers to repeatedly envision the sacrificial death of the Lord, which enables them to proclaim it with conviction (1 Corinthians 11: 26).[168]

In the Irvingian tradition of Restorationist Christianity, consubstantiation is taught as the explanation of how the real presence is effected in the liturgy.[169]

Seventh-day Adventists

[edit]In the Seventh-day Adventist Church the Holy Communion service customarily is celebrated once per quarter. The service includes the ordinance of footwashing and the Lord's Supper. Unleavened bread and unfermented (non-alcoholic) grape juice is used. Open communion is practised: all who have committed their lives to the Saviour may participate. The communion service must be conducted by an ordained pastor, minister or church elder.[170][171]

Jehovah's Witnesses

[edit]Jehovah's Witnesses commemorate Jesus' death annually on the evening that corresponds to the Passover,[172] Nisan 14, according to the ancient Jewish calendar.[173] They generally refer to the observance as "the Lord's Evening Meal" or the "Memorial of Christ's Death". They believe the event is the only annual religious observance commanded for Christians in the Bible.[174]

Of those who attend the Memorial, a small minority worldwide partake of the wine and unleavened bread. Jehovah's Witnesses believe that only 144,000 people will go to heaven, to serve as under-priests and co-rulers with Christ the King in God's Kingdom. They are referred to as the "anointed" class. They believe that the baptized "other sheep" also benefit from the ransom sacrifice, and are respectful observers and viewers of the Lord's Supper, but they hope to obtain everlasting life in Paradise restored on earth.[175]

The Memorial, held after sundown, includes a sermon on the meaning and importance of the celebration and gathering, and includes the circulation of unadulterated red wine and unleavened bread (matzo). Jehovah's Witnesses believe that the bread represents Jesus' perfect body which he gave on behalf of mankind, and that the wine represents his perfect blood which he shed to redeem fallen man from inherited sin and death. The wine and the bread (sometimes referred to as "emblems") are viewed as symbolic and commemorative; the Witnesses do not believe in transubstantiation or consubstantiation.[175][176]

Latter-day Saints

[edit]In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the "Holy Sacrament of the Lord's Supper",[26] more simply referred to as the Sacrament, is administered every Sunday (except General Conference or other special Sunday meeting) in each Latter-Day Saint Ward or branch worldwide at the beginning of Sacrament meeting. The Sacrament, which consists of both ordinary bread and water (rather than wine or grape juice), is prepared by priesthood holders prior to the beginning of the meeting. At the beginning of the Sacrament, priests say specific prayers to bless the bread and water.[177] The Sacrament is passed row-by-row to the congregation by priesthood holders (typically deacons).[178]

The prayer recited for the bread and the water is found in the Book of Mormon[179][180] and Doctrine and Covenants. The prayer contains the above essentials given by Jesus: "Always remember him, and keep his commandments […] that they may always have his Spirit to be with them." (Moroni, 4:3.)[181]

Non-observing denominations

[edit]Salvation Army

[edit]While the Salvation Army does not reject the Eucharistic practices of other churches or deny that their members truly receive grace through this sacrament, it does not practice the sacraments of Communion or Baptism. This is because they believe that these are unnecessary for the living of a Christian life, and because in the opinion of Salvation Army founders William and Catherine Booth, the sacrament placed too much stress on outward ritual and too little on inward spiritual conversion.[182]

Quakers

[edit]Emphasizing the inward spiritual experience of their adherents over any outward ritual, the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) historically do not baptize or observe physical Communion.[183] George Fox, founder of the society, emphasized a personal relationship with God. Quakers associated with the Friends General Conference, Conservatives, and the Friends United Meeting[184] continue to not observe the practice. Some Evangelical Quakers, however, do sometimes offer voluntary outward rituals, although most continue to emphasize an inward spiritual experience.[185]

Christian Scientists

[edit]Although the early Church of Christ, Scientist observed Communion, founder Mary Baker Eddy eventually discouraged the physical ritual as she believed it distracted from the true spiritual nature of the sacrament. As such, Christian Scientists do not observe physical communion with bread and wine, but spiritual communion at two special Sunday services each year by "uniting together with Christ in silent prayer and on bended knee".[186]

Shakers

[edit]The United Society of Believers (commonly known as Shakers) do not take communion, instead viewing every meal as a Eucharistic feast.[187]

Practice and customs

[edit]Open and closed communion

[edit]

Christian denominations differ in their understanding of whether they may celebrate the Eucharist with those with whom they are not in full communion. The apologist Justin Martyr (c. 150) wrote of the Eucharist "of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined."[188] This was continued in the practice of dismissing the catechumens (those still undergoing instruction and not yet baptized) before the sacramental part of the liturgy, a custom which has left traces in the expression "Mass of the Catechumens" and in the Byzantine Rite exclamation by the deacon or priest, "The doors! The doors!", just before recitation of the Creed.[189]

Churches such as the Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox Churches practice closed communion under normal circumstances. However, the Catholic Church allows administration of the Eucharist, at their spontaneous request, to properly disposed members of the eastern churches (Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Church of the East) not in full communion with it and of other churches that the Holy See judges to be sacramentally in the same position as these churches; and in grave and pressing need, such as danger of death, it allows the Eucharist to be administered also to individuals who do not belong to these churches but who share the Catholic Church's faith in the reality of the Eucharist and have no access to a minister of their own community.[190] Some Protestant communities exclude non-members from Communion.

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) practices open communion, provided those who receive are baptized,[191][192] but the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod and the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod (WELS) practice closed communion, excluding non-members and requiring communicants to have been given catechetical instruction.[193][194] The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada, the Evangelical Church in Germany, the Church of Sweden, and many other Lutheran churches outside of the U.S. also practice open communion.

Some use the term "close communion" for restriction to members of the same denomination, and "closed communion" for restriction to members of the local congregation alone.

Most Protestant communities including Congregational churches, the Church of the Nazarene, the Assemblies of God, Methodists, most Presbyterians and Baptists, Anglicans, and Churches of Christ and other non-denominational churches practice various forms of open communion. Some churches do not limit it to only members of the congregation, but to any people in attendance (regardless of Christian affiliation) who consider themselves to be Christian. Others require that the communicant be a baptized person, or a member of a church of that denomination or a denomination of "like faith and practice". Some Progressive Christian congregations offer communion to any individual who wishes to commemorate the life and teachings of Christ, regardless of religious affiliation.[h]

Most Latter-Day Saint churches practice closed communion; one notable exception is the Community of Christ, the second-largest denomination in this movement.[196] While The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the largest of the LDS denominations) technically practice a closed communion, their official direction to local Church leaders (in Handbook 2, section 20.4.1, last paragraph) is as follows: "Although the sacrament is for Church members, the bishopric should not announce that it will be passed to members only, and nothing should be done to prevent nonmembers from partaking of it."[197]

In the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church the Eucharist is only given to those who have come prepared to receive the life-giving body and blood. Therefore, in a manner to worthily receive, believers fast the night before the liturgy, from around 6pm or the conclusion of evening prayer, and remain fasting until they receive Holy Qurbana the next morning. Additionally, members who plan to receive the holy communion have to follow a strict guide of prescribed prayers from the Shehimo, or the book of common prayers, for the week.[198]

Preparation

[edit]Catholic

[edit]The Catholic Church requires its members to receive the sacrament of Penance or Reconciliation before taking Communion if they are aware of having committed a mortal sin[199][200] and to prepare by fasting, prayer, and other works of piety.[200][201]

Eastern Orthodox

[edit]Traditionally, the Eastern Orthodox church has required its members to have observed all church-appointed fasts (most weeks, this will be at least Wednesday and Friday) for the week prior to partaking of communion, and to fast from all food and water from midnight the night before. In addition, Orthodox Christians are to have made a recent confession to their priest (the frequency varying with one's particular priest),[202] and they must be at peace with all others, meaning that they hold no grudges or anger against anyone.[203] In addition, one is expected to attend Vespers or the All-Night Vigil, if offered, on the night before receiving communion.[203] Furthermore, various pre-communion prayers have been composed, which many (but not all) Orthodox churches require or at least strongly encourage members to say privately before coming to the Eucharist.[204] However, all this will typically vary from priest to priest and jurisdiction to jurisdiction, but abstaining from food and water for several hours beforehand is a fairly universal rule.

Protestant confessions

[edit]Many Protestant congregations generally reserve a period of time for self-examination and private, silent confession just before partaking in the Lord's Supper.[citation needed]

Adoration

[edit]

Eucharistic adoration is a practice in the Latin Church, Anglo-Catholic and some Lutheran traditions, in which the Blessed Sacrament is exposed to and adored by the faithful. When this exposure and adoration is constant (twenty-four hours a day), it is called "Perpetual Adoration". In a parish, this is usually done by volunteer parishioners; in a monastery or convent, it is done by the resident monks or nuns. In the Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, the Eucharist is displayed in a monstrance, typically placed on an altar, at times with a light focused on it, or with candles flanking it.

Health issues

[edit]Gluten

[edit]The gluten in wheat bread is dangerous to people with celiac disease and other gluten-related disorders, such as non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy.[205][206][207] For the Catholic Church, this issue was addressed in the 24 July 2003 letter[208] of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, which summarized and clarified earlier declarations. The Catholic Church believes that the matter for the Eucharist must be wheaten bread and fermented wine from grapes: it holds that, if the gluten has been entirely removed, the result is not true wheaten bread.[209] For celiacs, but not generally, it allows low-gluten bread. It also permits Holy Communion to be received under the form of either bread or wine alone, except by a priest who is celebrating Mass without other priests or as principal celebrant.[210] Many Protestant churches offer communicants gluten-free alternatives to wheaten bread, usually in the form of a rice-based or other gluten-free wafer.[211]

Alcohol

[edit]As already indicated, the one exception is in the case of a priest celebrating Mass without other priests or as principal celebrant. The water that in the Roman Rite is prescribed to be mixed with the wine must be only a relatively small quantity.[212] The practice of the Coptic Church is that the mixture should be two parts wine to one part water.[213]

Some Protestant churches allow communion in a non-alcoholic form, either normatively or as a pastoral exception. Since the invention of the necessary technology, grape juice which has been pasteurized to stop the fermentation process the juice naturally undergoes and de-alcoholized wine from which most of the alcohol has been removed (between 0.5% and 2% remains) are commonly used, and more rarely water may be offered.[214] Exclusive use of unfermented grape juice is common in Baptist churches, the United Methodist Church, Seventh-day Adventists, Christian Churches/Churches of Christ, Churches of Christ, Church of God (Anderson, Indiana), some Lutherans, Assemblies of God, Pentecostals, Evangelicals, the Christian Missionary Alliance, and other American independent Protestant churches.

For members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, water is exclusively used in place of wine.[215]

Transmission of diseases

[edit]

Risk of infectious disease transmission related to use of a common communion cup exists but it is low. No case of transmission of an infectious disease related to a common communion cup has ever been documented. Experimental studies have demonstrated that infectious diseases can be transmitted. The most likely diseases to be transmitted would be common viral illnesses such as the common cold. A study of 681 individuals found that taking communion up to daily from a common cup did not increase the risk of infection beyond that of those who did not attend services at all.[216][217]

In influenza epidemics, some churches suspend the giving wine at communion, for fear of spreading the disease. This is in full accord with Catholic Church belief that communion under the form of bread alone makes it possible to receive all the fruit of Eucharistic grace. However, the same measure has also been taken by churches that normally insist on the importance of receiving communion under both forms. This was done in 2009 by the Church of England.[218]

Some fear contagion through the handling involved in distributing the hosts to the communicants, even if they are placed on the hand rather than on the tongue. Accordingly, some churches use mechanical wafer dispensers or "pillow packs" (communion wafers with wine inside them). While these methods of distributing communion are not generally accepted in Catholic parishes, one parish provides a mechanical dispenser to allow those intending to commune to place in a bowl, without touching them by hand, the hosts for use in the celebration.[219]

See also

[edit]- Catholic social teaching

- Catholic theology of the body

- Concomitance

- Perichoresis

- Pihta

- Fatira

- Hamra

- Sacrament (Latter Day Saints)

Eucharistic practice

[edit]History

[edit]- Marburg Colloquy (1529)

- Sacramentarians (approx. 16th century)

- The Adoration of the Sacrament by Martin Luther (1523)

- Confession Concerning Christ's Supper by Martin Luther (1528)

- Ubiquitarians (1530 and 1540)

- Year of the Eucharist (2004–2005)

- Host desecration

Notes

[edit]- ^ Within Oriental Orthodoxy, the "Oblation" is the term used in the Syriac, Coptic and Armenian churches, while "Consecration" is used in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. "Oblation" and "Consecration" are of course used also by the Eastern Catholic Churches that are of the same liturgical tradition as these churches. Likewise, in the Gaelic language of Ireland and Scotland the word Aifreann, usually translated into English as "Mass", is derived from Late Latin Offerendum, meaning "oblation", "offering".

- ^ "9.1 Concerning the thanksgiving give thanks thus: 9.2 First, concerning the cup: "We give thanks to you, our Father, For the holy vine of David your servant which you have revealed to us through Jesus your servant. To you be glory for ever". 9.3 And concerning the fragment: "We give thanks to you, our Father, For the life and knowledge, which you have revealed to us through Jesus your servant". But let no one eat or drink of your Eucharist, unless they have been baptized into the name of the Lord; for concerning this also the Lord has said, "Give not that which is holy to the dogs". 10.1 After you have had your fill, give thanks thus: 10.2 We give thanks to you holy Father for your holy Name which you have made to dwell in our hearts and for the knowledge, faith and immortality which you have revealed to us through Jesus your servant. To you be glory for ever. 10.3 You Lord almighty have created everything for the sake of your Name; you have given human beings food and drink to partake with enjoyment so that they might give thanks; but to us you have given the grace of spiritual food and drink and of eternal life through Jesus your servant. 10.4 Above all we give you thanks because you are mighty. To you be glory for ever. 10.5 Remember Lord your Church, to preserve it from all evil and to make it perfect in your love. And, sanctified, gather it from the four winds into your kingdom which you have prepared for it. Because yours is the power and the glory for ever. ..."

- ^ "14.1 But every Lord's day do ye gather yourselves together, and break bread, and give thanksgiving after having confessed your transgressions, that your sacrifice may be pure. 14.2. But let no one that is at variance with his fellow come together with you, until they be reconciled, that your sacrifice may not be profaned. 14.3. For this is that which was spoken by the Lord: In every place and time offer to me a pure sacrifice; for I am a great King, saith the Lord, and my name is wonderful among the nations."

- ^ The tradition that Ignatius was a direct disciple of the Apostle John is consistent with the content of his letters.[68]

- ^ Radbertus was canonized in 1073 by Pope Gregory VII. His works are edited in Patrologia Latina, volume 120 (1852).

- ^ For example, Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Lutherans, Anglicans, Old and Catholics; and cf. the presentation of the Eucharist as a sacrament in the Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document[82] of the World Council of Churches

- ^ A misprint in the English translation of the Medieval Sourcebook: Canons of the Fourth Lateran Council, 1215 gives "transubstantiatio" in place of "transubstantiatis" in Canon 1,[99] as opposed to the original: "Iesus Christus, cuius corpus et sanguis in sacramento altaris sub speciebus panis et vini veraciter continentur, transsubstantiatis pane in corpus, et vino in sanguinem potestate divina".[100]

- ^ In most United Church of Christ local churches, the Communion Table is "open to all Christians who wish to know the presence of Christ and to share in the community of God's people".[195]

References

[edit]- ^ Luke 22:19–20, 1 Corinthians 11:23–25

- ^ Wright, N. T. (2015). The Meal Jesus Gave Us: Understanding Holy Communion (Revised ed.). Louisville, Kentucky. p. 63. ISBN 9780664261290.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d "Encyclopædia Britannica, s.v. Eucharist". Britannica.com. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Keeping the Feast: Thoughts on Virtual Communion in a Lockdown Era". 27 March 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- ^ Mattox, Mickey L.; Roeber, A. G. (2012). Changing Churches: An Orthodox, Catholic, and Lutheran Theological Conversation. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-0802866943.

In this "sacramental union", Lutherans taught, the body and blood of Christ are so truly united to the bread and wine of the Holy Communion that the two may be identified. They are at the same time body and blood, bread and wine. This divine food is given, more-over, not just for the strengthening of faith, nor only as a sign of our unity in faith, nor merely as an assurance of the forgiveness of sin. Even more, in this sacrament the Lutheran Christian receives the very body and blood of Christ precisely for the strengthening of the union of faith. The "real presence" of Christ in the Holy Sacrament is the means by which the union of faith, effected by God's Word and the sacrament of baptism, is strengthened and maintained. Intimate union with Christ, in other words, leads directly to the most intimate communion in his holy body and blood.

- ^ McKim, Donald K. (1998). Major Themes in the Reformed Tradition. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 263. ISBN 978-1579101046.

- ^ Poulson, Christine (1999). The Quest for the Grail: Arthurian Legend in British Art, 1840–1920. Manchester University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0719055379.

By the late 1840s Anglo-Catholic interest in the revival of ritual had given new life to doctrinal debate over the nature of the Eucharist. Initially, 'the Tractarians were concerned only to exalt the importance of the sacrament and did not engage in doctrinal speculation'. Indeed they were generally hostile to the doctrine of transubstantiation. For an orthodox Anglo-Catholic such as Dyce the doctrine of the Real Presence was acceptable, but that of transubstantiation was not.

- ^ Campbell, Ted (1996). Christian Confessions: A Historical Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 325. ISBN 9780664256500.

- ^ a b Bristow, George (2007). "The Remembrance Meeting: The Theology of the Lord's Supper among the Christian Brethren". The Emmaus Journal. 16 (1): 182–220.

- ^ Gibson, Jean. "Lesson 13: The Lord's Supper". Plymouth Brethren Writings. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

On the night of this sacred observance, Jesus introduced the memorial observance of bread and wine. Thereafter it was to remind believers of his body given and his blood shed for their salvation.

- ^ Gospel Figures in Art by Stefano Zuffi 2003 ISBN 978-0892367276 p. 252

- ^ "Strong's Greek: 2169. εὐχαριστία (eucharistia) – thankfulness, giving of thanks". Biblehub.com. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Strong's Greek: 2168. εὐχαριστέω (eucharisteó) – to be thankful". biblehub.com. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d LaVerdiere, Eugene (1996), The Eucharist in the New Testament and the Early Church, Liturgical Press, pp. 1–2, ISBN 978-0814661529

- ^ a b Thomas R. Schreiner, Matthew R. Crawford, The Lord's Supper (B&H Publishing Group 2011 ISBN 978-0805447576), p. 156

- ^ John H. Armstrong, Four Views on the Lord's Supper (Zondervan 2009 ISBN 978-0310542759)

- ^ Robert Benedetto, James O. Duke, The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History (Westminster John Knox Press 2008 ISBN 978-0664224165), volume 2

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:23–24

- ^ Eucharist in the New Testament by Jerome Kodell 1988 ISBN 0814656633

- ^ Milavec, Aaron (2003). 'Didache' 9:1. Liturgical Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0814658314. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Theological Dictionary of the New Testament by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich and Geoffrey W. Bromiley 1985 ISBN 0802824048

- ^ Stanley E. Porter, Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation (Taylor & Francis 2007 ISBN 978-0415201001)

- ^ Epistle to the Ephesians 13:1; Epistle to the Philadelphians 4; Epistle to the Smyrnaeans 7:1, 8:1

- ^ Introducing Early Christianity by Laurie Guy ISBN 0830839429 p. 196

- ^ "First Apology, 66". Ccel.org. 1 June 2005. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ a b c See, e.g., Roberts, B. H. (1938). Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Deseret News Press. OCLC 0842503005.

- ^ 11:20–21

- ^ Christopher A. Stephenson, Types of Pentecostal Theology: Method, System, Spirit, OUP US, 2012[ISBN missing]

- ^ Roger E. Olson, The Westminster Handbook to Evangelical Theology, Westminster John Knox Press, UK, 2004

- ^ Edward E. Hindson, Daniel R. Mitchell, The Popular Encyclopedia of Church History: The People, Places, and Events That Shaped Christianity, Harvest House Publishers, US, 2013, [ISBN missing]

- ^ Higgins, Jethro (2018), Holy Communion: What is the Eucharist?, Oregon Catholic Press

- ^ Luke 24:35; Acts 2:42, 2:46, 20:7 and 20:11

- ^ Richardson, Alan (1958). Introduction to the Theology of the New Testament. London: SCM Press. p. 364.

- ^ Bayne, Brian L. (1974). "Plymouth Brethren". In Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A. (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church; Nature. Vol. 329. Oxford University Press. p. 578. Bibcode:1987Natur.329..578B. doi:10.1038/329578b0. PMID 3309679.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1330.

- ^ "Small Catechism (6): The Sacrament of the Altar". Christ Lutheran Church. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Prestige, Leonard (1927). "Anglo-Catholics: What they believe". Society of SS. Peter and Paul. Retrieved 23 June 2020 – via anglicanhistory.org.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "mass".

- ^ "Concluding Rites". www.usccb.org. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ "liturgy of the Eucharist | Definition & Rite". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Catholic Church (2006). Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. p. 275., and Catholic Church (1997). Catechism of the Catholic Church. United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. pp. 1328–32. ISBN 978-1574551105.

- ^ Spicer, Andrew (2016). Lutheran Churches in Early Modern Europe. Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 978-1351921169.

- ^ Kellerman, James. "The Lutheran Way of Worship". First Bethlehem Lutheran Church. Archived from the original on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Hovhanessian, Vahan (2011), "Badarak (Patarag)", The Encyclopedia of Christian Civilization, American Cancer Society, doi:10.1002/9780470670606.wbecc0112, ISBN 978-0470670606

- ^ Bradshaw, Paul F.; Johnson, Maxwell E. (2012). The Eucharistic Liturgies: Their Evolution and Interpretation. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814662663.

- ^ Tyndale Bible Dictionary / editors, Philip W. Comfort, Walter A. Elwell, 2001 ISBN 0842370897, article: Lord's Supper, The

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church / editors, F. L. Cross & E. A. Livingstone 2005 ISBN 978-0192802903, article Eucharist

- ^ Moloney, Francis (2001). "A Hard Saying" : The Gospel and Culture. The Liturgical Press. pp. 109–30.

- ^ Mark 14:22–25

- ^ Matthew 26:26–29

- ^ Luke 22:13–20

- ^ Heron, Alisdair >I.C. Table and Tradition Westminster Press, Philadelphia (1983) p. 3 ISBN 9780664245160

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. A Textual Commentary on the New Testament UBS (1971) pp. 173ff [ISBN missing]

- ^ Heron, Alisdair >I.C. Table and Tradition Westminster Press, Philadelphia (1983) p. 5

- ^ Caird, G.B. The Gospel of Luke Pelican (1963) p. 237 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 2837.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Tyndale Bible Dictionary / editors, Philip W. Comfort, Walter A. Elwell, 2001 ISBN 0842370897, article: "John, Gospel of"

- ^ "Eucharist and Gospel of John". VatiKos Theologie. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ John 6:26–65

- ^ John 6:51–59

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:23–25

- ^ 1 Corinthians 11:17–34

- ^ Lambert, J.C. (1978). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia (reprint ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0802880451.

- ^ Jude 12

- ^ Bruce Metzger, The canon of the New Testament. 1997

- ^ "There are now two quite separate Eucharistic celebrations given in Didache 9–10, with the earlier one now put in second place". Crossan. The historical Jesus. Citing Riggs, John W. 1984

- ^ O'Connor, John Bonaventure. "St. Ignatius of Antioch." The Catholic Encyclopedia Archived 2023-01-25 at the Wayback Machine Vol. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 15 Feb. 2016

- ^ Letter to the Smyrnaeans, 7-8

- ^ Letter to the Philadelphians, 4

- ^ St. Justin Martyr. CHURCH FATHERS: The First Apology Chapter 66. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ See First Apology, 65–67

- ^ a b Chazelle[full citation needed]

- ^ Niremberg, David (4 February 2013). Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393347913.

- ^ "The Eucharist in the Economy of Salvation". Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1333. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. (emphasis added)

- ^ Mahler, Corey (10 December 2019). "Art. X: Of the Holy Supper | Book of Concord". bookofconcord.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Mahler, Corey (21 October 2020). "Part VI | Book of Concord". bookofconcord.org. Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ^ Horton, Michael S. (2008). People and Place: A Covenant Ecclesiology. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0664230715.

- ^ Strout, Shawn O. (29 February 2024). Of Thine Own Have We Given Thee: A Liturgical Theology of the Offertory in Anglicanism. James Clarke & Company. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-227-17995-6.

- ^ Finger, Thomas N. (26 February 2010). A Contemporary Anabaptist Theology: Biblical, Historical, Constructive. InterVarsity Press. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-8308-7890-1.

Anabaptists here, despite sharp disagreement with Zwingli over baptism, generally affirmed his memorialism.

- ^ "Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry (Faith and Order Paper no. 111, the "Lima Text")". Oikoumene.org. 15 January 1982. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ html#c10499 Baptism, Eucharist and Ministry document[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kauffman, Daniel (1898). Manual of Bible Doctrines. Elkhart: Mennonite Publishing Co. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Lumen gentium 11. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ Presbyterorum ordinis 5. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ "Definition of PASCH". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ "Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church #271". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraphs 1362–67.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church #1367".

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church #1410".

- ^ Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church #282. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ "The Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of the Eucharist: Basic Questions and Answers". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Summa Theologiæ Article 2". New Advent. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Council of Trent, Decree concerning the Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist, chapter IV and canon II". History.hanover.edu. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Council of Trent, Decree concerning the Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist, canon III

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1377.

- ^ Mulcahy, O.P., Bernard. "The Holy Eucharist" (PDF). kofc.org. Knights of Columbus. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Aquinas, Thomas. "Summa Theologiae, Question 77". New Advent. Kevin Knight. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ "Canon 1". Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ^ "Denzinger 8020". Catho.org. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Fourth Lateran Council (1215)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. of Faith Fourth Lateran Council: 1215, 1. Confession of Faith, retrieved 2010-03-13.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Fourth Lateran Council (1215)". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.. of Faith Fourth Lateran Council: 1215, 1. Confession of Faith, retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ^ John 6:51

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1376.

- ^ Under Julius III Council of Trent Session 13 Chapter IV. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Session XIII, chapter IV; cf. canon II)

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The sacrament of the Eucharist #1377". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- ^ Matthew 26:26–28; Mark 14:22–24; Luke 22:19–20

- ^ 1 Cor. 11:23–25

- ^ "'Abrahamic, Mosaic, and Prophetic Foundations of the Eucharist'. Inside the Vatican 16, no. 4 (2008): 102–05". Archived from the original on 10 December 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Holy Communion". www.catholicity.com.

- ^ Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church # 291. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1385.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 1457.

- ^ "Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church #286".

- ^ Runciman, Steven (1968). The Great Church in Captivity. Cambridge University Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0521313100.

- ^ Why do the Orthodox use leavened bread since leaven is a symbol of sin? Is not Christ's body sinless? Archived 26 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine – orthodoxanswers.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.