Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mariner 6 and 7

View on Wikipedia

Mariner 6 and 7 | |

| Mission type | Mars flyby |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 1969-014A |

| SATCAT no. | 3759 |

| Mission duration | 1 year, 9 months and 28 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Mariner-F |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 381 kg[1] |

| Power | 449 W |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | February 25, 1969, 01:29:02 UTC[2] |

| Rocket | Atlas SLV-3D Centaur-D1A |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36B |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Decommissioned |

| Deactivated | December 23, 1970 |

| Flyby of Mars | |

| Closest approach | July 31, 1969 |

| Distance | 3,431 kilometers (2,132 mi) |

| Mission type | Mars flyby |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 1969-030A |

| SATCAT no. | 3837 |

| Mission duration | 1 year, 9 months and 1 day |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Mariner-G |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 381 kg[3] |

| Power | 449 W |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | March 27, 1969, 22:22:00 UTC[4] |

| Rocket | Atlas SLV-3D Centaur-D1A |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36A |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Decommissioned |

| Deactivated | December 28, 1970 |

| Flyby of Mars | |

| Closest approach | August 5, 1969 |

| Distance | 3,430 kilometers (2,130 mi) |

Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 (Mariner Mars 69A and Mariner Mars 69B) were two uncrewed NASA robotic spacecraft that completed the first dual mission to Mars in 1969 as part of NASA's wider Mariner program. Mariner 6 was launched from Launch Complex 36B at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station[2] and Mariner 7 from Launch Complex 36A.[4] The two craft flew over the equator and south polar regions, analyzing the atmosphere and the surface with remote sensors, and recording and relaying hundreds of pictures. The mission's goals were to study the surface and atmosphere of Mars during close flybys, in order to establish the basis for future investigations, particularly those relevant to the search for extraterrestrial life, and to demonstrate and develop technologies required for future Mars missions. Mariner 6 also had the objective of providing experience and data which would be useful in programming the Mariner 7 encounter five days later.

Launch

[edit]

Three Mariner probes were constructed for the mission, with two intended to fly and one as a spare in the event of a mission failure. The spacecraft were shipped to Cape Canaveral with their Atlas-Centaur boosters in December 1968 – January 1969 to begin pre-launch checkouts and testing. On February 14, Mariner 6 was undergoing a simulated countdown on LC-36A, electrical power running, but no propellant loaded in the booster. During the test run, an electrical relay in the Atlas malfunctioned and opened two valves in the pneumatic system which allowed helium pressure gas to escape from the booster's balloon skin. The Atlas began to crumple over, however two pad technicians quickly activated a manual override switch to close the valves and pump helium back in. Although Mariner 6 and its Centaur stage had been saved, the Atlas had sustained structural damage and could not be reused, so they were removed from the booster and placed atop Mariner 7's launch vehicle on the adjacent LC-36B, while a different Atlas was used for Mariner 7.

NASA awarded the quick-thinking technicians, Bill McClure and Charles (Jack) Beverlin, Exceptional Bravery Medals for their courage in risking being crushed underneath the 124-foot (38 m) rocket. In 2014, an escarpment on Mars which NASA'S Opportunity rover had recently visited was named the McClure-Beverlin Ridge in honor of the pair, who had since died.[5][6][7]

Mariner 6 lifted off from LC-36B at Cape Canaveral on February 25, 1969, using the Atlas-Centaur AC-20 rocket, while Mariner 7 lifted off from LC-36A on March 27, using the Atlas-Centaur AC-19 rocket. The boost phase for both spacecraft went according to plan and no serious anomalies occurred with either launch vehicle. A minor LOX leak froze some telemetry probes in AC-20 which registered as a drop in sustainer engine fuel pressure; however, the engine performed normally through powered flight. In addition, BECO occurred a few seconds early due to a faulty cutoff switch, resulting in longer than intended burn time of the sustainer engine, but this had no serious effect on vehicle performance or the flight path. AC-20 was launched at a 108-degree azimuth.[8]

The Centaur stage on both flights was set up to perform a retrorocket maneuver after capsule separation. This served two purposes, firstly to prevent venting propellant from the spent Centaur from contacting the probe, secondly to put the vehicle on a trajectory that would send it into solar orbit and not impact the Martian surface, potentially contaminating the planet with Earth microbes.

Spaceflight

[edit]

On July 29, 1969, less than a week before closest approach, Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) lost contact with Mariner 7. The center regained the signal via the backup low-gain antenna and regained use of the high gain antenna again shortly after Mariner 6's close encounter. Leaking gases from a battery (which later failed) were thought to have caused the anomaly.[4] Based on the observations that Mariner 6 made, Mariner 7 was reprogrammed in flight to take further observations of areas of interest and actually returned more pictures than Mariner 6, despite the battery's failure.[9]

Closest approach for Mariner 6 occurred July 31, 1969, at 05:19:07 UT at a distance of 3,431 kilometers (2,132 mi)[2] above the martian surface. Closest approach for Mariner 7 occurred August 5, 1969 at 05:00:49 UT[4] at a distance of 3,430 kilometers (2,130 mi) above the Martian surface. This was less than half of the distance used by Mariner 4 on the previous US Mars flyby mission.[9]

Both spacecraft are now defunct and in heliocentric orbits.[9]

Science data and findings

[edit]

By chance, both spacecraft flew over cratered regions and missed both the giant northern volcanoes and the equatorial grand canyon discovered later. Their approach pictures did, however, photograph about 20 percent of the planet's surface,[9] showing the dark features long seen from Earth – in the past, these features had been mistaken for canals by some ground-based astronomers. When Mariner 7 flew over the Martian south pole on August 4, 1969, it sent back pictures of ice-filled craters and outlines of the south polar cap.[10] Despite the communication defect suffered by Mariner 7 earlier, these pictures were of better quality than what had been sent by its twin, Mariner 6, a few days earlier when it flew past the Martian equator.[11] In total, 201 photos were taken and transmitted back to Earth, adding more detail than the earlier mission, Mariner 4.[9] Both crafts also studied the atmosphere of Mars.

Coming a week after Apollo 11, Mariner 6 and 7's flyby of Mars received less than the normal amount of media coverage for a mission of this significance.

The ultraviolet spectrometer onboard Mariners 6 and 7 was constructed by the University of Colorado's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP).[12]

The engineering model of Mariners 6 and 7 still exists, and is owned by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). It is on loan to LASP, and is on display in the lab's lobby.[13][14]

Mariner 6 and 7 infrared radiometer observations helped to trigger a scientific revolution in Mars knowledge.[15][16] The Mariner 6 and 7 infrared radiometer results showed that the atmosphere of Mars is composed mostly of carbon dioxide (CO2), and they were also able to detect trace amounts of water on the surface of Mars.[15]

Spacecraft and subsystems

[edit]

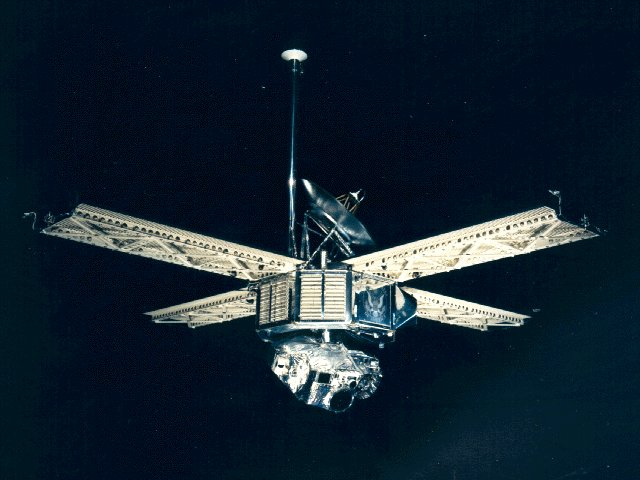

The Mariner 6 and 7 spacecraft were identical, consisting of an octagonal magnesium frame base, 138.4 cm (54.5 in) diagonally and 45.7 cm (18.0 in) deep. A conical superstructure mounted on top of the frame held the high-gain 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) diameter parabolic antenna and four solar panels, each measuring 215 cm (85 in) x 90 cm (35 in), were affixed to the top corners of the frame. The tip-to-tip span of the deployed solar panels was 5.79 m (19.0 ft). A low-gain omnidirectional antenna was mounted on a 2.23 m (7 ft 4 in) high mast next to the high-gain antenna. Underneath the octagonal frame was a two-axis scan platform which held scientific instruments. Overall science instrument mass was 57.6 kg (127 lb). The total height of the spacecraft was 3.35 m (11.0 ft).

The spacecraft was attitude stabilized in three axes, referenced to the Sun and the star Canopus. It utilized 3 gyros, 2 sets of 6 nitrogen jets, which were mounted on the ends of the solar panels, a Canopus tracker, and two primary and four secondary Sun sensors. Propulsion was provided by a 223-newton rocket motor, mounted within the frame, which used the mono-propellant hydrazine. The nozzle, with 4-jet vane vector control, protruded from one wall of the octagonal structure. Power was supplied by 17,472 photovoltaic cells, covering an area of 7.7 square meters (83 sq ft) on the four solar panels. These could provide 800 watts of power near Earth, and 449 watts while near Mars. The maximum power requirement was 380 watts, once Mars was reached. A 1200 watt-hour, rechargeable, silver-zinc battery was used to provide backup power. Thermal control was achieved through the use of adjustable louvers on the sides of the main compartment.

Three telemetry channels were available for telecommunications. Channel A carried engineering data at 8+1⁄3 or 33+1⁄3 bit/s, channel B carried scientific data at 66+2⁄3 or 270 bit/s and channel C carried science data at 16,200 bit/s. Communications were accomplished through the high- and low-gain antennas, via dual S-band traveling wave tube amplifiers, operating at 10 or 20 watts, for transmission. The design also included a single receiver. An analog tape recorder, with a capacity of 195 million bits, could store television images for subsequent transmission. Other science data was stored on a digital recorder. The command system, consisting of a central computer and sequencer (CC&S), was designed to actuate specific events at precise times. The CC&S was programmed with both a standard mission and a conservative backup mission before launch, but could be commanded and reprogrammed in flight. It could perform 53 direct commands, 5 control commands, and 4 quantitative commands.

Scientific Instruments

[edit]Both spacecraft carried the same set of instruments:[17][18]

- Imaging System (Two TV cameras)

- Infrared Spectrometer

- Ultraviolet Spectrometer

- Infrared Radiometer

- Celestial Mechanics Experiment

- S-Band Occultation Experiment

- Conical Radiometer

See also

[edit]- List of missions to Mars

- Space exploration

- Uncrewed space missions

- Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (included an infrared radiometer for the Martian surface)

References

[edit]- ^ "Mariner 6 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Mariner 6". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "Mariner 7 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. NASA. Retrieved November 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Mariner 7". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2011.

- ^ "Opportunity's Southward View of 'McClure-Beverlin Escarpment'". NASA / JPL. 2014.

- ^ "Billy McClure obituary". 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment (veterans' association). 2009. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Charles Beverlin obituary". Dignity Memorial. 2013.

- ^ Mariner-Mars 1969: A Preliminary Report. NASA. 1969. p. 21. SP-225.

- ^ a b c d e Rod Pyle (2012). Destination Mars: New Explorations of the Red Planet. Prometheus Books. pp. 61–66. ISBN 978-1-61614-589-7.

- ^ "From the Archives (August 6, 1969): Ice-filled craters on Mars". The Hindu. August 6, 2019. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ Walter Sullivan (August 6, 1969). "Mariner 7 Sends Sharpest Mars Pictures; Mariner 7 Sends Sharpest Mars Photos So Far". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ J. B. Pearce; K. A. Gause; E. F. Mackey; et al. (April 1, 1971). "Mariner 6 and 7 Ultraviolet Spectrometers". Applied Optics. 10 (4): 805–812. Bibcode:1971ApOpt..10..805P. doi:10.1364/ao.10.000805. ISSN 0003-6935. PMID 20094543.

- ^ "Looking back at 75: Honoring LASP's contributions to historic missions". Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics. October 11, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2025.

- ^ CorrugatedSymphony (2016). "Mariner 6 & 7 working engineering model". Imgur. Retrieved March 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "Infrared Spectrometer and the Exploration of Mars". American Chemical Society. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ S. C. Chase (March 1, 1969). "Infrared radiometer for the 1969 mariner mission to Mars". Applied Optics. 8 (3): 639. Bibcode:1969ApOpt...8..639C. doi:10.1364/AO.8.000639. ISSN 1559-128X. PMID 20072273.

- ^ "Mariner 6 - NASA Science". December 20, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2025.

- ^ "Mariner 7 - NASA Science". January 25, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2025.

External links

[edit]- Mariner Mars 1969 Launches - Press Kit

- Tracking and data system support for the Mariner Mars 1969 mission. Volume 1 - Planning phase through midcourse maneuver

- Tracking and data system support for the Mariner Mars 1969 mission. Volume 2: Midcourse maneuver through end of nominal mission

- Tracking and data system support for the Mariner Mars 1969 mission. Volume 3: Extended operations mission

- The Mariner 6 and 7 flight paths and their determination from tracking data

- Two over Mars - Mariner 6 and Mariner 7, February - August 1969

- Mariner 6 Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Mariner 7 Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Mariner 6 and 7 Data Set Information (highly technical)

- Mariner 6 and 7 Data Viewer Page (includes many images)

- Page with reprocessed Mariner 7 images

- Mariner 6 and 7 images

Mariner 6 and 7

View on GrokipediaBackground and Planning

Historical Context

The Mariner program, initiated by NASA in the early 1960s, represented a pivotal step in interplanetary exploration, building on the success of earlier unmanned missions to the inner solar system. Mariner 2, launched in August 1962, achieved the first successful flyby of Venus, providing critical data on its dense, hot atmosphere and surface conditions, which validated the spacecraft's design for future planetary encounters.[8] This mission established the program's emphasis on low-cost, rapid-development probes using twin spacecraft for redundancy, a strategy that minimized risks in the nascent field of deep-space travel. Following this, Mariner 4 marked NASA's first venture to Mars in November 1964, conducting a flyby in July 1965 that returned the initial close-up images of the planet's surface.[8] Mariner 4's 22 photographs revealed a heavily cratered, moon-like terrain, decisively debunking long-held astronomical myths of artificial canals and advanced civilizations on Mars, which had originated from 19th-century telescopic observations.[9] However, the mission imaged less than 1% of the Martian surface, primarily southern cratered highlands, leaving significant gaps in coverage of polar regions and equatorial zones that limited understanding of the planet's diverse geology and atmosphere.[9] Additionally, radio occultation measurements indicated an atmospheric pressure of approximately 6 millibars, suggesting a thin carbon dioxide envelope unsuitable for complex life as previously speculated.[9] In the broader context of the 1960s, the Mariner missions were driven by the intensifying Cold War space race between the United States and the Soviet Union, where planetary exploration served as a demonstration of technological prowess and national commitment to scientific advancement.[3] A primary motivation was the ongoing search for evidence of extraterrestrial life on Mars, fueled by its proximity to Earth and historical intrigue, while the data gathered also laid groundwork for more ambitious endeavors like the Viking lander missions planned for the mid-1970s.[3] To address the limitations of single-probe flybys and enhance data reliability, NASA opted for a dual-mission approach in 1969, deploying two identical spacecraft to provide complementary observations and redundancy against potential failures.[3] The development of Mariner 6 and 7, designated as Mariner Mars 69A and 69B, was authorized by NASA shortly after the Mariner 4 flyby in 1965 as an extension of the Mariner program's modular design philosophy.[10] Three spacecraft were constructed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory—one as a backup—to ensure mission readiness, reflecting the program's evolution toward more robust engineering informed by prior flights.[11] The total cost for the project was approximately $148 million in 1969 dollars, underscoring the efficient scaling of resources in NASA's planetary exploration efforts during the era.[12]Mission Objectives

The primary objectives of the Mariner 6 and 7 mission were to conduct close flybys of Mars to study its surface and atmosphere, capturing images that collectively mapped approximately 20% of the planet's surface.[13] These flybys aimed to measure key atmospheric properties, including composition and pressure, while searching for signs of life or indications of water on the surface.[4] The missions sought to expand understanding of Martian geology and environmental conditions through remote sensing during the encounters.[1] Secondary objectives focused on engineering demonstrations to support subsequent Mars explorations, such as the Viking program, by validating technologies for orbital and landing missions.[4] This included performing radio occultation to profile the ionosphere and using infrared instruments to map temperature variations across targeted regions.[7] These tests provided critical data on spacecraft performance in the Martian environment, informing designs for more complex future operations.[1] The dual-spacecraft strategy emphasized complementary coverage, with Mariner 6 targeted at equatorial latitudes and Mariner 7 at the south polar cap, separated by five days to detect any short-term atmospheric or surface changes and ensure backup data redundancy.[7] This approach addressed gaps in prior equatorial-focused flybys, such as Mariner 4's limited polar observations.[10]Launch and Trajectory

Launch Details

Mariner 6 was launched on February 25, 1969, at 01:29:02 UT from Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 36B aboard an Atlas SLV-3C Centaur D1A rocket (AC-20).[4] The launch experienced an initial delay following a malfunction during a February 14 countdown test, where a helium pressure gas leak in the unfueled Atlas stage threatened to cause structural deflation of the launch vehicle.[10] Two ground crew technicians heroically entered the area to manually start the pressurizing pumps, preventing collapse and enabling the mission to proceed on schedule; for their actions, they each received NASA's Exceptional Bravery Medal.[10] The Atlas booster ignited first, followed by the Centaur upper stage burn of approximately 7.5 minutes, achieving Earth escape velocity and injecting the spacecraft onto its interplanetary trajectory after a total powered flight of about 12 minutes.[14] Mariner 7 followed on March 27, 1969, at 22:22:01 UT from adjacent Launch Complex 36A using an identical Atlas SLV-3C Centaur D1A rocket configuration (AC-19).[7] During the Centaur phase, a minor anomaly occurred in the propulsion pneumatics subsystem, where the engine controls regulator pressure briefly exceeded limits to 347 N/cm² before returning to normal without impacting performance or causing any adverse effects.[14] The launch successfully placed Mariner 7 on its Mars transfer orbit, mirroring the direct-ascent profile of its twin.[14] Both missions were managed by NASA's Mariner Project Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[2] Following launch, each spacecraft underwent midcourse corrections to refine their trajectories toward Mars. For Mariner 6, the first correction occurred on March 1, 1969, involving a brief 5.35-second thruster burn of its hydrazine propulsion system.[10] Mariner 7 received its midcourse correction on April 8, 1969.[10] A second correction for Mariner 6 took place on April 8, 1969, with a 7.6-second burn.[15] These adjustments ensured precise alignment for the planned flybys. With both primary spacecraft successfully deployed, their designated backups were repurposed for future missions rather than flown.[15]Flight Paths and Encounters

Following launch, Mariner 6 followed a heliocentric trajectory that carried it to Mars in 156 days, achieving closest approach on July 31, 1969, at an altitude of 3,431 kilometers (2,132 miles) south of the Martian equator.[3] The spacecraft's path was refined by midcourse corrections shortly after launch, ensuring precise alignment for the flyby geometry.[4] At encounter, Mariner 6 passed Mars at a relative speed of approximately 10.7 km/s before entering a heliocentric orbit with perihelion and aphelion distances of 1.14 AU and 1.75 AU, respectively.[4] Mariner 7, launched a month later, traversed its interplanetary path in 131 days, reaching closest approach on August 5, 1969, at 3,430 kilometers (2,130 miles) above the south polar region near 59° S, 28° E.[7] Like its twin, it underwent initial midcourse corrections post-launch to optimize its trajectory.[3] The flyby occurred at a similar relative speed of about 10.7 km/s, after which the spacecraft entered a heliocentric orbit of 1.11 AU by 1.70 AU.[7] The missions were planned for complementary geometries, with Mariner 6 targeting equatorial regions and Mariner 7 a more southerly route to enhance coverage of the south polar cap.[3] Mid-mission, ground controllers reprogrammed Mariner 7 to expand south polar imaging from 25 to 33 frames based on preliminary Mariner 6 results.[7] During cruise, Mariner 7 experienced a 7-hour loss of contact approximately five days before encounter, attributed to a possible battery or micrometeoroid issue, but full operations were restored via ground commands using the low-gain antenna by August 2.[3]Spacecraft Design

Structure and Subsystems

The Mariner 6 and 7 spacecraft were identical in design, each featuring an octagonal magnesium frame that served as the central structural base, measuring 138.4 cm across the flats and 45.7 cm deep, with an overall height of 3.35 meters from the scan platform to the top of the low-gain antenna.[4] The frame supported seven electronics compartments and provided mounting points for key components, contributing to a launch mass of 412 kg per spacecraft.[16] A 1.4-meter parabolic high-gain antenna was mounted centrally for deep-space communications, while four rectangular solar panels extended from the frame, each providing approximately 2.1 square meters of area and collectively generating about 450 watts of power at Mars distance.[4][1] Attitude control was achieved through a three-axis stabilization system referenced to the Sun and the star Canopus, utilizing sun sensors, a Canopus star tracker, three gyroscopes, and 12 nitrogen cold gas jets for precise orientation to within 0.05 degrees.[16][17] The propulsion subsystem employed a single hydrazine monopropellant thruster for midcourse trajectory corrections, delivering a total delta-V capability of approximately 100 m/s, with no provision for orbital insertion as the mission was strictly flyby-oriented.[16][18] Thermal control was managed passively through multilayer thermal blankets and actively via bimetallic louvers that regulated heat rejection from radiating surfaces, maintaining component temperatures during the 156-day cruise to Mars.[1][19] Data handling included a digital tape recorder with a capacity of 157 million bits for storing imagery and telemetry prior to transmission.[16]Power and Communications

The power subsystem for Mariner 6 and 7 relied on solar arrays as the primary source, supplemented by batteries for peak and backup demands. Each spacecraft featured four rectangular deployable solar panels equipped with 17,472 solar cells, generating a nominal 449 watts at Mars distance (1.52 AU from the Sun), where the solar constant is approximately 590 W/m²—about 43% of Earth's value—resulting in reduced efficiency compared to near-Earth operations (around 800 watts). These panels were oriented toward the Sun using photoelectric sensors to maximize output, supporting steady-state loads of about 235-241 watts during cruise and up to 360 watts at encounter, including science instruments and propulsion. Rechargeable silver-zinc batteries provided redundancy and handled transient peaks, such as during off-Sun attitude maneuvers or high-power transmissions. The battery system had a capacity of approximately 1200-1350 watt-hours, with nominal discharge depths of 16-20% during operations; for instance, Mariner 6's battery delivered 8.6 ampere-hours during testing, recharged via the solar arrays at rates up to 650 mA to maintain 95-97% charge levels.[22][23] Despite a major anomaly on Mariner 7, where a cell ruptured and vented electrolyte around the flyby (causing a temporary power transient and velocity perturbation of about 39 cm/s), redundant regulators and inverters ensured continued functionality, with the system achieving 44% excess energy margin at Mars.[22][7] The communications subsystem employed a dual-redundant S-band transponder for telemetry, command reception, and tracking, operating coherently with the Deep Space Network (DSN). It used a traveling-wave tube amplifier (TWTA) with selectable 10-watt low-power and 20-watt high-power modes to boost the downlink signal over interplanetary distances, supporting data rates from 33⅓ bits/s in cruise mode to 66⅔ bits/s during near-encounter engineering telemetry and up to 16.2 kbits/s for real-time science data playback via the high-gain antenna.[22] Ground support came from DSN stations at Goldstone (California), Madrid (Spain), and Canberra (Australia), which handled ranging, Doppler tracking, and high-rate receptions using 210-foot antennas for optimal signal acquisition.[22] Reliability was enhanced by redundant transmitters, tape recorders for data storage (enabling playback at accelerated rates), and automatic switchover capabilities, which mitigated anomalies like transponder self-locks and antenna drive offsets. The attitude control system, using sun and Canopus sensors, aided precise high-gain antenna pointing to Earth. Overall, these features enabled a total data return of approximately 800 million bits across both missions, including 201 television images and supporting measurements.[22][24]Scientific Instruments

Imaging System

The Mariner 6 and 7 spacecraft each carried a dual-camera imaging system consisting of two vidicon-tube television cameras designed to capture high-resolution images of Mars during flyby encounters. The wide-angle Camera A featured a 50-millimeter focal length Zeiss planar lens with a field of view of approximately 11 by 14 degrees, enabling broader contextual views of the Martian surface and atmosphere. This camera utilized a filter wheel with blue, green, and red filters to facilitate color imaging through sequential exposures, allowing post-mission synthesis of approximate true-color composites by combining monochrome frames taken through each filter.[6] The narrow-angle Camera B employed a 508-millimeter focal length Cassegrain telephoto lens with a narrower field of view of 1.05 by 1.05 degrees, optimized for detailed close-up imaging of specific surface features. It operated with a minus-blue filter to enhance contrast in longer wavelengths, complementing the wide-angle camera's capabilities. Both cameras used secchi-type vidicon tubes with photosensitive surfaces that stored charge patterns from incoming light, scanned electronically to produce digital data at 704 lines per frame and 945 pixels per line, yielding 665,280 pixels total per image with 256 gray levels.[6][25] During operations, the imaging system acquired a total of 75 images from Mariner 6 (49 during far encounter from distances of about 1.8 million to 130,000 kilometers, and 26 during near encounter within 10,000 kilometers) and 126 from Mariner 7 (93 far-encounter and 33 near-encounter images). Far-encounter sequences primarily used the narrow-angle camera for global coverage at resolutions of 3 to 21 kilometers per pixel, while near-encounter imaging switched between both cameras for resolutions as fine as 300 meters per pixel, marking the highest detail achieved at the time. The first synthesized color image of Mars was produced from Mariner 7 frames combining red, green, and blue filter data, revealing subtle surface color variations.[6][3] Pre-flight calibration involved ground-based tests at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to characterize vidicon sensitivity, filter transmission, and lens performance under simulated Martian illumination conditions, ensuring accurate exposure control. Shutter integration times were adjustable from 5 to 50 milliseconds via ground commands to accommodate varying solar illumination angles and surface albedos during the flybys. Onboard, images were stored on a digital tape recorder and transmitted at high data rates up to 16,200 bits per second, with real-time analog video also available for select frames. These operational parameters enabled robust data return despite the spacecraft's high-speed flyby trajectories.[6]Spectrometers and Radiometers

The spectrometers and radiometers on Mariner 6 and 7 provided critical non-imaging measurements of Mars' atmosphere and surface thermal properties during the 1969 flybys.[4] These instruments targeted infrared, ultraviolet, and radio signals to probe composition, structure, and temperatures without relying on visual imaging.[26] The Infrared Spectrometer (IRS) operated across a wavelength range of 1.9 to 6.0 µm using a lead selenide (PbSe) detector, focusing on CO₂ absorption bands to analyze atmospheric and surface composition.[26] A secondary channel extended to 3.9–14.4 µm with a mercury-doped germanium detector for broader thermal emission studies.[26] The Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) covered 110–430 nm using an Ebert-Fastie design with dual photomultiplier tubes, enabling observations of the upper atmosphere above 170 km altitude through emission spectra of ionized species like CO₂⁺.[27] The Infrared Radiometer (IRR) featured two channels at 8–12 µm and 18–25 µm to measure surface brightness temperatures from 140 K to 325 K, particularly targeting polar regions.[28] Complementing these, the S-band occultation experiment used radio signals at approximately 2.3 GHz to probe the ionosphere during signal passage behind Mars.[4] During operations, the UVS performed scanning sweeps across the planetary disk and limb during each flyby to capture dayglow and auroral emissions, providing vertical profiles of atmospheric densities.[27] The IRR continuously monitored thermal emissions, recording polar cap temperatures in the range of approximately 140–200 K to infer ice composition and diurnal variations.[4] Occultation experiments occurred as the spacecraft crossed Mars' limb, tracking signal refraction and attenuation to derive ionospheric electron densities and neutral atmosphere pressures.[4] These measurements integrated with imaging data to contextualize surface-atmosphere interactions.[29] In 2024, the Planetary Data System (PDS) completed archiving of refined UVS datasets from Mariner 6 and 7, enhancing calibration and accessibility for studies of Mars' atmosphere near solar maximum conditions.[30] This update supports ongoing analyses of upper atmospheric dynamics and composition.[30]Scientific Results

Surface Imaging Analysis

The Mariner 6 and 7 missions collectively returned 201 photographs of Mars during their 1969 flybys, with the high-resolution near-encounter images providing detailed views of approximately 20% of the planet's surface. These images marked the first systematic close-up examination of Martian geology, surpassing the limited resolution of prior Earth-based telescopes and the earlier Mariner 4 flyby. The photographic data highlighted diverse surface features, including heavily cratered southern highlands suggestive of an ancient, Moon-like crust, chaotic and jumbled terrain near the equator possibly resulting from geological disruptions, and relatively flat plains in the polar regions characterized by irregular depressions and sparse craters. Additionally, Mariner 7's far-encounter sequence included the first spacecraft image of the Martian moon Phobos, depicting it as an irregularly shaped, elongated body and the darkest object observed in the solar system up to that point. Analyses of the imaging data focused on crater morphology and distribution, revealing two primary classes: smaller, bowl-shaped craters interpreted as relatively young formations and larger, flat-bottomed ones indicating older structures modified by erosional or depositional processes. Crater densities across both light and dark surface regions were found to be comparable, supporting the inference of a prolonged ancient bombardment phase that shaped much of the southern hemisphere's rugged terrain, with no significant recent activity evident. The images definitively disproved earlier speculations of vegetation or artificial canals on Mars, showing that previously reported linear "canal" features were instead chains of separate dark patches or natural fractures without biological signatures. Color information, obtained by combining black-and-white frames taken through red, green, and blue filters, demonstrated pronounced reddish hues across the surface, with the greatest contrast in red wavelengths; these hues were consistent with the presence of iron oxides in the regolith, contributing to the planet's characteristic rusty appearance. The photographs were captured using vidicon-tube cameras that scanned the scene line by line, producing analog signals digitized into 704 lines of 945 pixels each, with brightness values ranging from 0 to 255. Ground-based processing involved reconstructing these scans into coherent images through noise removal, geometric corrections, and enhancement techniques to preserve both fine-scale details and broad photometric variations. Resolutions achieved by the narrow-angle camera reached down to about 300 meters per pixel, enabling the identification of surface features such as individual craters and terrain boundaries that were previously indistinguishable.Atmospheric Measurements

The radio occultation experiments conducted during the Mariner 6 and 7 flybys measured surface pressures on Mars ranging from approximately 5 to 8.5 millibars, with an average value around 6 to 7 millibars at the latitudes observed, confirming a thin atmosphere compared to Earth's.[31] These measurements, taken at equatorial and polar-adjacent sites, revealed temperature profiles with surface values ranging from 150 K at the polar cap to 280–290 K at the equator, decreasing with altitude (subadiabatic lapse rates observed), with inversions noted near the northern polar region during early fall.[31] Infrared and ultraviolet spectrometry further characterized the atmospheric composition, identifying carbon dioxide as the dominant constituent at approximately 95%, with trace amounts of water vapor, oxygen, and carbon monoxide (each below 1%), and upper limits established for various other minor gases; upper limits for water vapor were established at less than 0.03 cm-atm (about 30 precipitable micrometers globally).[32] The ultraviolet spectrometer detected emissions from CO₂⁺ ions and atomic oxygen and hydrogen, indicating a CO₂-rich environment with negligible heavier hydrocarbons or ammonia.[33] In the upper atmosphere, the ultraviolet spectrometer observed dayglow emissions primarily from CO₂⁺ (A-X and B-X bands) around 1100–4300 Å, along with CO, C I, O I, and H I lines, resulting from solar photoionization and dissociative excitation.[33] Ionospheric electron densities peaked at about 1.5 to 1.7 × 10⁵ electrons per cubic centimeter at altitudes of 136 to 138 km, with topside temperatures around 390 to 420 K, showing no evidence of significant water vapor beyond trace atomic hydrogen.[31][33] Observations of the polar caps indicated they were primarily composed of solid carbon dioxide at temperatures near 150 K, with infrared radiation consistent with frozen CO₂ and potential adsorption of trace ozone (up to 3 × 10¹⁶ molecules per square centimeter) on the south polar cap surface.[4][34] Between the Mariner 6 and 7 flybys in July and August 1969, subtle seasonal variations were noted in polar cap extent and atmospheric pressure, reflecting early southern summer sublimation dynamics.[31] These results established Mars' atmosphere as thin and CO₂-dominated, with insufficient pressure and oxygen levels to support complex terrestrial life forms, while highlighting dynamic polar processes driven by seasonal CO₂ exchange.[31][32]Legacy and Impact

Technological Contributions

The Mariner 6 and 7 missions marked the first successful implementation of a paired flyby strategy in planetary exploration, launching two identical spacecraft to Mars in 1969 to enhance data reliability and mission assurance. By spacing the encounters just five days apart—Mariner 6 on July 31 and Mariner 7 on August 5—this dual-mission approach provided redundancy against potential failures in a single spacecraft, while allowing preliminary data from the first flyby to inform adjustments for the second. This concept demonstrated improved risk mitigation for deep-space missions, ensuring comprehensive coverage of Mars' equatorial and south polar regions despite the technological constraints of the era. Autonomous operations were facilitated by the spacecraft's Control Computer and Sequencer (CC&S), a 26-pound onboard computer that managed flyby sequencing independently, including automatic image capture every 42 seconds via the television cameras without requiring continuous ground intervention. Real-time ground commanding further enhanced adaptability; for instance, after Mariner 6's equatorial flyby, mission controllers reprogrammed Mariner 7 mid-mission to increase south polar imaging from 25 to 33 frames, enabling targeted observations based on emerging insights. A key midcourse maneuver executed on April 8 adjusted Mariner 7's trajectory for optimal polar coverage, utilizing efficient thruster firings from the spacecraft's monopropellant hydrazine system to achieve precise corrections with minimal fuel expenditure, advancing techniques for in-flight trajectory optimization.[4][7][36] Data handling innovations allowed the missions to return approximately 800 million bits of information despite 1960s limitations, employing a combination of analog and digital tape recorders to store high-volume imagery and scientific data during the brief flyby windows. The telemetry system supported variable rates, including a high-rate mode of 16,200 bits per second (bps) for rapid playback of stored pictures—transmitting one frame in about five minutes—and a lower 85 bps rate for real-time television data during near-encounter phases. These capabilities, integrated with three telemetry channels for engineering, scientific, and imaging data, enabled the storage and efficient downlink of 201 total images (75 from Mariner 6 and 126 from Mariner 7), covering about 20% of Mars' surface at resolutions down to 900 feet per pixel.[37][38][39]Influence on Subsequent Missions

The data from Mariner 6 and 7 provided a critical baseline for site selection in the Viking 1 and 2 missions, which successfully landed on Mars in 1976, by confirming the relative safety of equatorial terrains characterized by flat, cratered plains suitable for soft landings. These flybys imaged about 20 percent of the Martian surface, revealing a heavily cratered landscape that informed Viking's choice of Chryse Planitia and Utopia Planitia as landing zones, avoiding more hazardous polar or highland regions. Additionally, the missions' emphasis on equatorial and south polar observations influenced the design of Mariner 9, launched in 1971, which shifted focus to comprehensive orbital mapping, including detailed polar cap studies to build on the earlier flybys' atmospheric and surface data.[40][1] The findings from Mariner 6 and 7 played a pivotal role in debunking earlier speculations about biological activity on Mars, such as those inspired by telescopic observations of "canals," by demonstrating a barren, Moon-like surface and an atmosphere dominated by carbon dioxide with low pressure, thereby redirecting scientific priorities toward geological processes and climate dynamics. This paradigm shift transformed Mars exploration from speculative biology to rigorous studies of planetary evolution, influencing decades of missions focused on surface geology and atmospheric loss. In a recent development, the 2024 re-archiving of ultraviolet spectrometer (UVS) data from Mariner 6 and 7, certified in the Planetary Data System in 2025, has enabled new comparative analyses with the MAVEN orbiter's 2014 observations, shedding light on long-term atmospheric evolution over 50 years.[3][41][30][42] Beyond Mars-specific efforts, the Mariner 6 and 7 missions enhanced the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's (JPL) expertise in high-speed flyby operations and data acquisition, which directly contributed to the success of subsequent interplanetary missions like Voyager (1977) and Cassini (1997), where similar trajectory planning and instrument calibration techniques were applied to outer planet encounters. This accumulated proficiency marked a broader transition in planetary science from ground-based telescopic views to detailed robotic reconnaissance, establishing flybys as a foundational strategy for efficient, cost-effective exploration across the solar system.[43][44]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/mission/mariner-6/

- https://ntrs.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/api/citations/19710010985/downloads/19710010985.pdf

- https://www.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/history/50-years-ago-mariner-6-and-7-explore-mars/