Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mohawk people

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Key Information

| kanien "flint" | |

|---|---|

| People | Kanienʼkehá:ka |

| Language | Kanienʼkéha |

| Country | Kanièn:ke Haudenosauneega |

The Mohawk, also known by their own name, Kanien'kehá:ka (lit. 'People of the Flint'[2]), are an Indigenous people of North America and the easternmost nation of the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy (also known as the Five Nations or later the Six Nations).

Mohawk are an Iroquoian-speaking people with communities in southeastern Canada and northern New York State, primarily around Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. As one of the five original members of the Iroquois Confederacy, the Mohawk are known as the Keepers of the Eastern Door who are the guardians of the confederation against invasions from the east.

Today, Mohawk people belong to the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne, Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte First Nation, Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke, Mohawks of Kanesatake, Six Nations of the Grand River, and Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, a federally recognized tribe in the United States.[3]

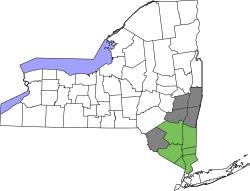

At the time of European contact, Mohawk people were based in the valley of the Mohawk River in present-day upstate New York, west of the Hudson River. Their territory ranged north to the St. Lawrence River, southern Quebec and eastern Ontario; south to greater New Jersey and into Pennsylvania; eastward to the Green Mountains of Vermont; and westward to the border with the Iroquoian Oneida Nation's traditional homeland territory.

Mohawk communities

[edit]

Members of the Kanienʼkehá:ka people now live in settlements in northern New York State and southeastern Canada.

Many Kanienʼkehá:ka communities have two sets of chiefs, who are in some sense competing governmental rivals. One group are the hereditary chiefs (royaner), nominated by Clan Mother matriarchs in the traditional Mohawk fashion. Mohawks of most of the reserves have established constitutions with elected chiefs and councilors, with whom the Canadian and U.S. governments usually prefer to deal exclusively. The self-governing communities are listed below, grouped by broad geographical cluster, with notes on the character of community governance found in each.

- Northern New York:

- Kanièn:ke (Ganienkeh) "Place of the flint". Traditional governance.

- Kanaʼtsioharè:ke "Place of the washed pail". Traditional governance.

- Along the St Lawrence in Quebec:

- Ahkwesáhsne (St. Regis, New York and Quebec/Ontario, Canada) "Where the partridge drums". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Kahnawà:ke (south of Montréal) "On the rapids". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Kanehsatà:ke (Oka) "Where the snow crust is". Canada, traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Tioweró:ton (Sainte-Lucie-des-Laurentides, Quebec). Canada, shared governance between Kahnawà꞉ke and Kanehsatà꞉ke.

- Southern Ontario:

- Kenhtè꞉ke (Tyendinaga) "On the bay". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Wáhta (Gibson) "Maple tree". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections.

- Ohswé:ken "Six Nations of the Grand River". Traditional governance, band/tribal elections. Mohawks form the majority of the population of this Iroquois Six Nations reserve. There are also Mohawk Orange Lodges in Canada.

Given increased activism for land claims, a rise in tribal revenues due to establishment of gaming on certain reserves or reservations, competing leadership, traditional government jurisdiction, issues of taxation, and the Canadian Indian Act, Mohawk communities have been dealing with considerable internal conflict since the late 20th century.

Language

[edit]The Mohawk language, or its native name, Kanyen'kéha, is a Northern Iroquoian language. Like many Indigenous languages of the Americas, Mohawk is a polysynthetic language. Written in the Roman alphabet, its orthography was standardized in 1993 at the Mohawk Language Standardization Conference.[4]

Name

[edit]In the Mohawk language, the Mohawk people call themselves the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka ("people of the flint"). The Mohawk became wealthy traders as other nations in their confederacy needed their flint for tool making. Their Algonquian-speaking neighbors (and competitors), the people of Muh-heck Haeek Ing ("food area place"), the Mohicans, referred to the people of Ka-nee-en Ka as Maw Unk Lin, meaning "bear people". The Dutch heard and wrote this term as Mohawk, and also referred to the Kanienʼkehá꞉ka as Egil or Maqua.

The French colonists adapted these latter terms as Aignier and Maqui, respectively. They also referred to the people by the generic Iroquois, a French derivation of the Algonquian term for the Five Nations, meaning "Big Snakes". The Algonquians and Iroquois were traditional competitors and enemies.

History

[edit]First contact with European settlers

[edit]In the upper Hudson and Mohawk Valley regions, the Mohawks long had contact with the Algonquian-speaking Mohican people who occupied territory along the Hudson, as well as other Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples to the north around the Great Lakes. The Mohawks had extended their own influence into the St. Lawrence River Valley, which they maintained for hunting grounds.

The Mohawk likely defeated the St. Lawrence Iroquoians in the 16th century, and kept control of their territory. In addition to hunting and fishing, for centuries the Mohawks cultivated productive maize fields on the fertile floodplains along the Mohawk River, west of the Pine Bush.

On June 28, 1609, a band of Hurons led Samuel De Champlain and his crew into Mohawk country, the Mohawks being completely unaware of this situation. De Champlain made it clear he wanted to strike the Mohawks down after their raids on the neighboring nations. On July 29, 1609, hundreds of Hurons and many of De Champlain's French crew fell back from the mission, daunted by what lay ahead. Sixty Huron Indians, De Champlain, and two Frenchmen saw some Mohawks in a lake near Ticonderoga; the Mohawks spotted them as well. De Champlain and his crew fell back, then advanced to the Mohawk barricade after landing on a beach. They met the Mohawks at the barricade; 200 warriors advanced behind four chiefs. They were equally astonished to see each other—De Champlain surprised at their stature, confidence, and dress; the Mohawks surprised by De Champlain's steel cuirass and helmet. One of the chiefs raised his bow at Champlain and the Indians. Champlain fired three shots that pierced the Mohawk chiefs' wooden armor, killing them instantly. The Mohawks stood in shock until they started flinging arrows at the crowd. A brawl began and the Mohawks fell back seeing the damage this new technology dealt on their chiefs and warriors. This was the first contact the Mohawks had with Europeans. This incident also sparked the Beaver Wars.

Beaver Wars

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

In the seventeenth century, the Mohawk encountered both the Dutch, who went up the Hudson River and established a trading post in 1614 at the confluence of the Mohawk and Hudson Rivers, and the French, who came south into their territory from New France (present-day Quebec). The Dutch were primarily merchants and the French also conducted fur trading. During this time the Mohawk fought with the Huron in the Beaver Wars for control of the fur trade with the Europeans. Their Jesuit missionaries were active among First Nations and Native Americans, seeking converts to Catholicism.

In 1614, the Dutch opened a trading post at Fort Nassau, New Netherland. The Dutch initially traded for furs with the local Mohican, who occupied the territory along the Hudson River. Following a raid in 1626 when the Mohawks resettled along the south side of the Mohawk River,[5]: pp.xix–xx in 1628, they mounted an attack against the Mohican, pushing them back to the area of present-day Connecticut. The Mohawks gained a near-monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch by prohibiting the nearby Algonquian-speaking peoples to the north or east to trade with them but did not entirely control this.

European contact resulted in a devastating smallpox epidemic among the Mohawk in 1635; this reduced their population by 63%, from 7,740 to 2,830, as they had no immunity to the new disease. By 1642 they had regrouped from four into three villages, recorded by Catholic missionary priest Isaac Jogues in 1642 as Ossernenon, Andagaron, and Tionontoguen, all along the south side of the Mohawk River from east to west. These were recorded by speakers of other languages with different spellings, and historians have struggled to reconcile various accounts, as well as to align them with archeological studies of the areas. For instance, Johannes Megapolensis, a Dutch minister, recorded the spelling of the same three villages as Asserué, Banagiro, and Thenondiogo.[5] Late 20th-century archeological studies have determined that Ossernenon was located about 9 miles west of the current city of Auriesville; the two were mistakenly conflated by a tradition that developed in the late 19th century in the Catholic Church.[6][7]

While the Dutch later established settlements in present-day Schenectady and Schoharie, further west in the Mohawk Valley, merchants in Fort Nassau continued to control the fur trading. Schenectady was established essentially as a farming settlement, where the Dutch took over some of the former Mohawk maize fields in the floodplain along the river. Through trading, the Mohawk and Dutch became allies of a kind.

During their alliance, the Mohawks allowed Dutch Protestant missionary Johannes Megapolensis to come into their communities and teach the Christian message. He operated from the Fort Nassau area for about six years, writing a record in 1644 of his observations of the Mohawk, their language (which he learned), and their culture. While he noted their ritual of torture of captives, he recognized that their society had few other killings, especially compared to the Netherlands of that period.[8][9]

The trading relations between the Mohawk and Dutch helped them maintain peace even during the periods of Kieft's War and the Esopus Wars, when the Dutch fought localized battles with other native peoples. In addition, Dutch trade partners equipped the Mohawk with guns to fight against other First Nations who were allied with the French, including the Ojibwe, Huron-Wendat, and Algonquin. In 1645, the Mohawk made peace for a time with the French, who were trying to keep a piece of the fur trade.[10]

During the Pequot War (1634–1638), the Pequot and other Algonquian Indians of coastal New England sought an alliance with the Mohawks against English colonists of that region. Disrupted by their losses to smallpox, the Mohawks refused the alliance. They killed the Pequot sachem Sassacus who had come to them for refuge, and returned part of his remains to the English governor of Connecticut, John Winthrop, as proof of his death.[11]

In the winter of 1651, the Mohawk attacked on the southeast and overwhelmed the Algonquian in the coastal areas. They took between 500 and 600 captives. In 1664, the Pequot of New England killed a Mohawk ambassador, starting a war that resulted in the destruction of the Pequot, as the English and their allies in New England entered the conflict, trying to suppress the Native Americans in the region. The Mohawk also attacked other members of the Pequot confederacy, in a war that lasted until 1671.[citation needed]

In 1666, the French attacked the Mohawk in the central New York area, burning the three Mohawk villages south of the river and their stored food supply. One of the conditions of the peace was that the Mohawk accept Jesuit missionaries. Beginning in 1669, missionaries attempted to convert Mohawks to Christianity, operating a mission in Ossernenon 9 miles west[6][7] of present-day Auriesville, New York until 1684, when the Mohawks destroyed it, killing several priests.

Over time, some converted Mohawk relocated to Jesuit mission villages established south of Montreal on the St. Lawrence River in the early 1700s: Kahnawake (used to be spelled as Caughnawaga, named for the village of that name in the Mohawk Valley) and Kanesatake. These Mohawk were joined by members of other Indigenous peoples but dominated the settlements by number. Many converted to Roman Catholicism. In the 1740s, Mohawk and French set up another village upriver, which is known as Akwesasne. Today a Mohawk reserve, it spans the St. Lawrence River and present-day international boundaries to New York, United States, where it is known as the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation.

Kateri Tekakwitha, born at Ossernenon in the late 1650s, has become noted as a Mohawk convert to Catholicism. She moved with relatives to Caughnawaga on the north side of the Mohawk river after her parents' deaths.[5] She was known for her faith and a shrine was built to her in New York. In the late 20th century, she was beatified and was canonized in October 2012 as the first Native American Catholic saint. She is also recognized by the Episcopal and Lutheran churches.

After the fall of New Netherland to England in 1664, the Mohawk in New York traded with the English and sometimes acted as their allies. During King Philip's War, Metacom, sachem of the warring Wampanoag Pokanoket, decided to winter with his warriors near Albany in 1675. Encouraged by the English, the Mohawk attacked and killed all but 40 of the 400 Pokanoket.[citation needed]

From the 1690s, Protestant missionaries sought to convert the Mohawk in the New York colony. Many were baptized with English surnames, while others were given both first and surnames in English.

During the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Mohawk and Abenaki First Nations in New England were involved in raids conducted by the French and English against each other's settlements during Queen Anne's War and other conflicts. They conducted a growing trade in captives, holding them for ransom. Neither of the colonial governments generally negotiated for common captives, and it was up to local European communities to raise funds to ransom their residents. In some cases, French and Abenaki raiders transported captives from New England to Montreal and the Mohawk mission villages. The Mohawk at Kahnawake forcibly adopted numerous young women and children to add to their own members, having suffered losses to disease and warfare. For instance, among them were numerous survivors of the more than 100 captives taken in the Deerfield raid in western Massachusetts. The minister of Deerfield was ransomed and returned to Massachusetts, but his daughter was forcibly adopted by a Mohawk family and ultimately assimilated and married a Mohawk man.[12]

During the era of the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War), Anglo-Mohawk partnership relations were maintained by men such as Sir William Johnson in New York (for the British Crown), Conrad Weiser (on behalf of the colony of Pennsylvania), and Hendrick Theyanoguin (for the Mohawk). Johnson called the Albany Congress in June 1754, to discuss with the Iroquois chiefs repair of the damaged diplomatic relationship between the British and the Mohawk, along with securing their cooperation and support in fighting the French,[13] in engagements in North America.

American Revolutionary War

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

During the second and third quarters of the 18th century, most of the Mohawks in the Province of New York lived along the Mohawk River at Canajoharie. A few lived at Schoharie, and the rest lived about 30 miles downstream at the Tionondorage Castle, also called Fort Hunter. These two major settlements were traditionally called the Upper Castle and the Lower Castle. The Lower Castle was almost contiguous with Sir Peter Warren's Warrensbush. Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, built his first house on the north bank of the Mohawk River almost opposite Warrensbush and established the settlement of Johnstown.

The Mohawk were among the four Iroquois people that allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War. They had a long trading relationship with the British and hoped to gain support to prohibit colonists from encroaching into their territory in the Mohawk Valley. Joseph Brant acted as a war chief and successfully led raids against British and ethnic German colonists in the Mohawk Valley, who had been given land by the British administration near the rapids at present-day Little Falls, New York.

A few prominent Mohawk, such as the sachem Little Abraham (Tyorhansera) at Fort Hunter, remained neutral throughout the war.[14] Joseph Louis Cook (Akiatonharónkwen), a veteran of the French and Indian War and ally of the rebels, offered his services to the Americans, receiving an officer's commission from the Continental Congress. He led Oneida warriors against the British. During this war, Johannes Tekarihoga was the civil leader of the Mohawk. He died around 1780. Catherine Crogan, a clan mother and wife of Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, named her brother Henry Crogan as the new Tekarihoga.

In retaliation for Brant's raids in the valley, the rebel colonists organized Sullivan's Expedition. It conducted extensive raids against other Iroquois settlements in central and western New York, destroying 40 villages, crops, and winter stores. Many Mohawk and other Iroquois migrated to Canada for refuge near Fort Niagara, struggling to survive the winter.

After the Revolution

[edit]

After the American victory, the British ceded their claim to land in the colonies, and the Americans forced their allies, the Mohawks and others, to give up their territories in New York. Most of the Mohawks migrated to Canada, where the Crown gave them some land in compensation. The Mohawks at the Upper Castle fled to Fort Niagara, while most of those at the Lower Castle went to villages near Montreal.

Joseph Brant led a large group of Iroquois out of New York to what became the reserve of the Six Nations of the Grand River, Ontario. Brant continued as a political leader of the Mohawks for the rest of his life. This land extended 100 miles from the head of the Grand River to the head of Lake Erie where it discharges.[15] Another Mohawk war chief, John Deseronto, led a group of Mohawk to the Bay of Quinte. Other Mohawks settled in the vicinity of Montreal and upriver, joining the established communities (now reserves) at Kahnawake, Kanesatake, and Akwesasne.

On November 11, 1794, representatives of the Mohawk (along with the other Iroquois nations) signed the Treaty of Canandaigua with the United States, which allowed them to own land there.

The Mohawks fought as allies of the British against the United States in the War of 1812.

20th century to present

[edit]In 1971, the Mohawk Warrior Society, also Rotisken’rakéhte in the Mohawk language, was founded in Kahnawake. The duties of the Warrior Society are to use roadblocks, evictions, and occupations to gain rights for their people, and these tactics are also used among the warriors to protect the environment from pollution. The notable movements started by the Mohawk Warrior Society have been the Oka Crisis blockades in 1990 and the Caledonia Ontario, Douglas Creek occupation of a construction site in summer of 2006.

On May 13, 1974, at 4:00 a.m, Mohawks from the Kahnawake and Akwesasne reservations repossessed traditional Mohawk land near Old Forge, New York, occupying Moss Lake, an abandoned girls camp. The New York state government attempted to shut the operation down, but after negotiation, the state offered the Mohawk some land in Miner Lake, where they have since settled.

The Mohawks have organized for more sovereignty at their reserves in Canada, pressing for authority over their people and lands. Tensions with the Quebec provincial and national governments have been strained during certain protests, such as the Oka Crisis in 1990.

In 1993, a group of Akwesasne Mohawks purchased 322 acres of land in the Town of Palatine in Montgomery County, New York which they named Kanatsiohareke. It marked a return to their ancestral land.

Mohawk ironworkers in New York

[edit]Mohawks came from Kahnawake and other reserves to work in the construction industry in New York City in the early through the mid-20th century. They had also worked in construction in Quebec. The men were ironworkers who helped build bridges and skyscrapers, and who were called skywalkers because of their seeming fearlessness.[16] They worked from the 1930s to the 1970s on special labor contracts as specialists and participated in building the Empire State Building. The construction companies found that the Mohawk ironworkers did not fear heights or dangerous conditions. Their contracts offered lower than average wages to the First Nations people and limited labor union membership.[17] About 10% of all ironworkers in the New York area are Mohawks,[when?] down from about 15% earlier in the 20th century.[18]

The work and home life of Mohawk ironworkers was documented in Don Owen's 1965 National Film Board of Canada documentary High Steel.[19] The Mohawk community that formed in a compact area of Brooklyn, which they called "Little Caughnawaga", after their homeland, is documented in Reaghan Tarbell's Little Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back, shown on PBS in 2008. This community was most active from the 1920s to the 1960s. The families accompanied the men, who were mostly from Kahnawake; together they would return to Kahnawake during the summer. Tarbell is from Kahnawake and was working as a film curator at the George Gustav Heye Center of the National Museum of the American Indian, located in the former Custom House in Lower Manhattan.[20]

Since the mid-20th century, Mohawks have also formed their own construction companies. Others returned to New York projects. Mohawk skywalkers had built the World Trade Center buildings that were destroyed during the September 11 attacks, helped rescue people from the burning towers in 2001, and helped dismantle the remains of the building afterwards.[21] Approximately 200 Mohawk ironworkers (out of 2,000 total ironworkers at the site) participated in rebuilding the One World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. They typically drive the 360 miles from the Kahnawake reserve on the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to work the week in lower Manhattan and then return on the weekend to be with their families. A selection of portraits of these Mohawk ironworkers were featured in an online photo essay for Time magazine in September 2012.[22]

Contemporary issues

[edit]Gambling

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Surely the two cases mentioned in the last paragraph have been resolved in the intervening 15 years. (July 2025) |

Both the elected chiefs and the Warrior Society have encouraged gambling as a means of ensuring tribal self-sufficiency on the various reserves or Indian reservations. Traditional chiefs have tended to oppose gaming on moral grounds and out of fear of corruption and organized crime. Such disputes have also been associated with religious divisions: the traditional chiefs are often associated with the Longhouse tradition, practicing consensus-democratic values, while the Warrior Society has attacked that religion and asserted independence. Meanwhile, the elected chiefs have tended to be associated (though in a much looser and general way) with democratic, legislative and Canadian governmental values.

On October 15, 1993, Governor Mario Cuomo entered into the "Tribal-State Compact Between the St. Regis Mohawk First Nation and the State of New York". The compact allowed the Indigenous people to conduct gambling, including games such as baccarat, blackjack, craps and roulette, on the Akwesasne Reservation in Franklin County under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). According to the terms of the 1993 compact, the New York State Racing and Wagering Board, the New York State Police and the St. Regis Mohawk Tribal Gaming Commission were vested with gaming oversight. Law enforcement responsibilities fell under the state police, with some law enforcement matters left to the community. As required by IGRA, the compact was approved by the United States Department of the Interior before it took effect. There were several extensions and amendments to this compact, but not all of them were approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

On June 12, 2003, the New York Court of Appeals affirmed the lower courts' rulings that Governor Cuomo exceeded his authority by entering into the compact absent legislative authorization and declared the compact void.[23] On October 19, 2004, Governor George Pataki signed a bill passed by the State Legislature that ratified the compact as being nunc pro tunc, with some additional minor changes.[24]

In 2008 the Mohawk Nation was working to obtain approval to own and operate a casino in Sullivan County, New York, at Monticello Raceway. The U.S. Department of the Interior disapproved this action although the Mohawks gained Governor Eliot Spitzer's concurrence, subject to the negotiation and approval of either an amendment to the current compact or a new compact. Interior rejected the Mohawks' application to take this land into trust.[25]

In the early 21st century, two legal cases were pending that related to Native American gambling and land claims in New York. The State of New York has expressed similar objections to the Dept. of Interior taking other land into trust for federally recognized 'tribes', which would establish the land as sovereign Native American territory, on which they might establish new gaming facilities.[26] The other suit contends that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act violates the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution as it is applied in the State of New York. In 2010 it was pending in the United States District Court for the Western District of New York.[27]

Culture

[edit]Social organization

[edit]The main structures of social organization are the clans (ken'tara'okòn:'a). The number of clans vary among the Haudenosaunee; the Mohawk have three: Bear (Ohkwa:ri), Turtle (A'nó:wara), and Wolf (Okwaho).[28] Clans are nominally the descendants of a single female ancestor, with women possessing the leadership role. Each member of the same clan, across all the Six Nations, is considered a relative. Traditionally, marriages between people of the same clan are forbidden.[note 1] Children belong to their mother's clan.[29]

Religion

[edit]Traditional Mohawk religion is mostly Animist. "Much of the religion is based on a primordial conflict between good and evil."[30] Many Mohawks continue to follow the Longhouse Religion.

In 1632 a band of Jesuit missionaries now known as the Canadian Martyrs led by Isaac Jogues was captured by a party of Mohawks and brought to Ossernenon (now Auriesville, New York). Jogues and company attempted to convert the Mohawks to Catholicism, but the Mohawks took them captive, tortured, abused and killed them.[31] Following their martyrdom, new French Jesuit missionaries arrived and many Mohawks were baptized into the Catholic faith. Ten years after Jogues' death Kateri Tekakwitha, the daughter of a Mohawk chief and Tagaskouita, a Roman Catholic Algonquin woman, was born in Ossernenon and later was canonized as the first Native American saint. Religion became a tool of conflict between the French and British in Mohawk country. The Reformed clergyman Godfridius Dellius also preached among the Mohawks.[32]

Traditional attire

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

Historically, the traditional hairstyle of Mohawk men, and many men of the other groups of the Iroquois Confederacy, was to remove most of the hair from the head by plucking (not shaving) tuft by tuft of hair until all that was left was a smaller section, that was worn in a variety of styles, which could vary by community. The women wore their hair long, often dressed with traditional bear grease, or tied back into a single braid.

In traditional dress women often went topless in summer and wore a skirt of deerskin. In colder seasons, women wore a deerskin dress. Men wore a breech cloth of deerskin in summer. In cooler weather, they added deerskin leggings, a deerskin shirt, arm and knee bands, and carried a quill and flint arrow hunting bag. Women and men wore puckered-seam, ankle-wrap moccasins with earrings and necklaces made of shells. Jewelry was also created using porcupine quills such as Wampum belts. For headwear, the men would use a piece of animal fur with attached porcupine quills and features. The women would occasionally wear tiaras of beaded cloth. Later, dress after European contact combined some cloth pieces such as wool trousers and skirts.[33][34]

Marriage

[edit]The Mohawk Nation people have a matrilineal kinship system, with descent and inheritance passed through the female line. Today, the marriage ceremony may follow that of the old tradition or incorporate newer elements, but is still used by many Mohawk Nation marrying couples. Some couples choose to marry in the European manner and the Longhouse manner, with the Longhouse ceremony usually held first.[35]

Longhouses

[edit]Replicas of 17th-century longhouses have been built at landmarks and tourist villages, such as Kanata Village, Brantford, Ontario, and Akwesasne's "Tsiionhiakwatha" interpretation village. Other Mohawk Nation Longhouses are found on the Mohawk territory reserves that hold the Mohawk law recitations, ceremonial rites, and Longhouse Religion (or "Code of Handsome Lake"). These include:

- Ohswé꞉ken (Six Nations)[36] First Nation Territory, Ontario holds six Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouses.

- Wáhta[37] First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kenhtè꞉ke (Tyendinaga)[38] First Nation Territory, Ontario holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Ahkwesásne[39] First Nation Territory, which straddles the borders of Quebec, Ontario and New York, holds two Mohawk Ceremonial Community Longhouses.

- Kaʼnehsatà꞉ke First Nation Territory, Quebec holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kahnawà꞉ke[40] First Nation Territory, Quebec holds three Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouses.

- Kanièn꞉ke[41] First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

- Kanaʼtsioharà꞉ke[42] First Nation Territory, New York State holds one Ceremonial Mohawk Community Longhouse.

Notable historical Mohawk

[edit]These are notable historical Mohawk people. Contemporary people can be found under their First Nation or tribe.

- Joseph Brant or Thayendanegea (1743–1771), Mohawk leader, British officer, brother of Molly Brant

- Molly Brant or Degonwadonti (c. 1736 – 1796), Mohawk leader, sister of Joseph Brant

- Canaqueese (17th century), Mohawk war chief and diplomat from the Ohio Valley

- Esther Louise Georgette Deer or Princess White Deer (1891–1992), Kahnawá:ke Mohawk dancer and singer

- John Deseronto (c. 1745 – 1811), Tyendinaga Mohawk chief

- Hiawatha (c. 12th century), precontact Mohawk chief and cofounder of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy

- Karonghyontye or Captain David Hill (1745–1790), Mohawk leader during the American Revolutionary War

- E. Pauline Johnson or Tekahionwake (1861–1913), poet, author, and public speaker from the Six Nations Reserve of the Grand River

- George Henry Martin Johnson or Onwanonsyshon (1816–1884), Mohawk chief and interpreter

- John Norton or Teyoninhokarawen (c. 1770 – c. 1827), Scottish born, adopted into the Mohawk First Nation and made an honorary "Pine Tree Chief"

- Oronhyatekha (1841–1907), physician, scholar from Six Nations of the Grand River

- Ots-Toch (1600 – c. 1640), wife of Dutch colonist Cornelius A. Van Slyck

- Hendrick Tejonihokarawa (c. 1660 – c. 1735), Mohawk chief of the Wolf clan; one of the four kings to visit England to see Queen Anne to ask for help fighting the French

- St. Kateri Tekakwitha (Mohawk/Algonquin, 1656–1680), "Lily of the Mohawks", Roman Catholic saint

- Black Hawk, lacrosse player

Late 20th and 21st-century Mohawk people are listed under their specific First Nation or tribe at:

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Within certain clans there may also be different types of one animal or bird. For example, the turtle clan has three different types of turtles, the wolf clan has three different types of wolves and the bear clan includes three different types of bears allowing for marriage within the clan as long as each belongs to a different species of the clan."[29]

References

[edit]- ^ "Canada Census Profile 2021". Census Profile, 2021 Census. Statistics Canada Statistique Canada. 7 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ "HAUDENOSAUNEE GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS" (PDF). National Museum of the American Indian. 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "Meet the People". National Museum of the American Indian. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ Green, Jeremy. "Kanyen'kéha: Mohawk Language". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Snow, Dean R.; Gehring, Charles T.; Starna, William A. (1996). In Mohawk Country. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2723-8. Archived from the original on 2016-12-31. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- ^ a b Rumrill, Donald A. (1985). "An Interpretation and Analysis of the Seventeenth Century Mohawk Nation: Its Chronology and Movements". The Bulletin and Journal of Archaeology for New York State. 90: 1–39.

- ^ a b Snow, Dean R. (1995). Mohawk Valley Archaeology: The Sites (1st ed.). University at Albany Institute for Archaeological Studies. See also Snow, Dean R. (2016). Mohawk Valley Archaeology: The Sites. Occasional Papers in Anthropology. Vol. 23 (2nd ed.). Matson Museum of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University.

- ^ "Dutch missionary John Megapolensis on the Mohawks (Iroquois), 1644". Smithsonian Source. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2016.

- ^ Snow, Dean R.; Gehring, Charles T.; Starna, William A., eds. (1996). "A Short History of the Mohawk". In Mohawk Country: Early Narratives about a Native People. Syracuse University Press. pp. 38–46. ISBN 978-0-8156-0410-5. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24.

- ^ Fenton, William N.; Jennings, Francis; Druke, Mary A. (1985). "The Earliest Recorded Description. The Mohawk Treaty with New France at Three Rivers 1645". In Jennings, Francis (ed.). The History and Culture of Iroquois Diplomacy. Syracuse University Press. pp. 127–153.

- ^ Smith, Philip H. (1877). General History of Duchess County, From 1609 to 1876, Inclusive. Pawling, New York: self-published. p. 154.

- ^ Demos, John (1994). The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ "The Albany Congress". US History. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Little Abraham Tyorhansera, Mohawk Indian, Wolf Clan Chief". Native Heritage Project. 16 August 2012. Archived from the original on July 1, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2016.

- ^ Stone, William (September 1838). "Life of Joseph Brant—Thayendanegea; including the Border Wars of the American Revolution". American Monthly Magazine. 12: 12, 273–284.

- ^ "Sky Walking: Raising Steel, A Mohawk Ironworker Keeps Tradition Alive". WNYC. Archived from the original on 2016-11-01. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ Mitchell, Joseph (1960). "The Mohawks in High Steel". Apologies to the Iroquois. By Wilson, Edmund. New York: Vintage. pp. 3–36.

- ^ Nessen, Stephen (19 March 2012). "Sky Walking: Raising Steel, A Mohawk Ironworker Keeps Tradition Alive". WNYC. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ Owen, Don. High Steel. Online documentary. National Film Board of Canada. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- ^ Tarbell, Reaghan (2008). Little Caughnawaga: To Brooklyn and Back. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved August 31, 2009.

- ^ Wolf, White. "The Mohawks Who Built Manhattan (Photos)". White Wolf. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ Wallace, Vaughn (2012-09-11). "The Mohawk Ironworkers: Rebuilding the Iconic Skyline of New York". Time. Archived from the original on 2012-09-15. Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ^ Saratoga County Chamber of Commerce Inc., et al. v. George Pataki, as Governor of the State of New York, et al., 2003 NY Int. 83 (Court of Appeals of New York 12 June 2003), archived from the original on 24 October 2017 – via Cornell University Law School.

- ^ C. 590 of the Laws of 2004

- ^ "The Associate Deputy Secretary of the Interior" (PDF). Washington, D.C. 4 January 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Former Website of the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Warren v. United States of America, et al". Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- ^ "Mohawk Language Lessons 2017 Lesson 5 Clans". Kenhtè:ke nene kanyen’kehá:ka. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "Clan System". Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

- ^ "mohawk". Cultural Survival. 10 March 2010. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Emma (2013). The Death and Afterlife of the North American Martyrs. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 25.

- ^ Corwin, Edward Tanjore (1902). A Manual of the Reformed Church in America (formerly Reformed Protestant Dutch Church). 1628-1902. Board of publication of the Reformed church in America. pp. 408–410. ISBN 9780524060162.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Inglish, Patty (February 27, 2020). "Traditional Mohawk Nation Daily and Ceremonial Clothing". Owlcation. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- ^ Johannes Megapolensis Jr., "A Short Account of the Mohawk Indians." Short Account of the Mohawk Indians, August 2017, 168

- ^ Anne Marie Shimony, "Conservatism among the Iroquois at Six Nations Reserve", 1961

- ^ "Six Nations Of The Grand River". Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ "Home Page". www.wahta.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- ^ "Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte – Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory » Home". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ "She꞉kon/Greetings – Mohawk Council of Akwesasne". Archived from the original on 2007-12-26. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ Kahnawá:ke, Mohawk Council of. "Mohawk Council of Kahnawá:ke". www.kahnawake.com. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06.

- ^ "— ganienkeh.net-- Information from the People of Ganienkeh". Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2012-12-02.

- ^ "Kanatsiohareke Mohawk Community". Archived from the original on 2007-10-18. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

Bibliography

[edit]- Snow, Dean R. (1994). The Iroquois. Boston: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 1-55786-938-3.

- Dean R. Snow; William A. Starna; Charles T. Gehring, eds. (1996). In Mohawk Country: Early Narratives about a Native People. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815604105.

External links

[edit]- Culture of the Haudenosaunee Archived 2019-04-14 at the Wayback Machine on the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte website

- Akwesasne News at the Akwesasne website

- The Wampum Chronicles: Mohawk Territory articles on history and culture

- "Mohawk Institute", Geronimo Henry archived site

- Mohawk skyscraper builders and construction workers in New York City?

- The Iroquois Book of Rites by Horatio Hale, at Project Gutenberg

Mohawk people

View on GrokipediaIdentity and Terminology

Etymology and external names

The exonym "Mohawk" originated from a Narragansett-Algonquian term mohowawog, meaning "they eat animate things" or "man-eaters," applied by enemy tribes to the easternmost Iroquoian nation due to perceptions of their warfare practices.[10] European settlers, including the Dutch who first encountered them in the early 17th century along the Hudson River, adopted and anglicized this term, recording it as "Mohawk" by the 1630s in colonial documents.[10] Dutch variants included "Maqua," derived from the same Algonquian root, used in trade records and treaties as early as 1614.[11] In contrast, the Mohawk people's autonym is Kanien'kehá:ka, translating to "People of the Flint" or "People of the Chert" in their Iroquoian language, referencing abundant flint deposits in their ancestral lands near the Mohawk River and Lake Champlain, which were vital for tool-making.[11] [12] This self-designation underscores their identity tied to specific territorial resources, distinct from the pejorative external labels imposed by Algonquian rivals and later Europeans.[12] Within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, they are positioned as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door," a functional title emphasizing their role in diplomacy and defense rather than etymology.[1]Self-designation and cultural identity

The Kanien'kehá:ka, meaning "People of the Chert" or "People of the Flint," is the autonym preferred by the Mohawk people to designate themselves, referring to the flint-like chert stone abundant in their traditional eastern territories along the Mohawk River valley.[12][11] This self-name underscores their historical association with the material used for tools and weapons, distinguishing them from exonyms like "Mohawk," which originated from Algonquian or Dutch terms applied by early European observers.[12] The term Kanien'kehá:ka encapsulates their identity tied to specific landscapes, with "Kanien'ke" denoting the flint place.[13] As the easternmost nation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—known as the "People of the Longhouse"—the Kanien'kehá:ka serve as the Keepers of the Eastern Door, a role symbolizing their responsibility to guard the confederacy's eastern frontier and maintain diplomatic relations with external groups.[1][4] This position within the alliance of six nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora) formed under the Great Law of Peace emphasizes unity, participatory governance, and harmony with natural law, with the Mohawk acting as an Elder Brother alongside the Seneca and Onondaga.[4] Their cultural identity integrates oral traditions of the Peacemaker and Hiawatha, who established the confederacy's condolence ceremonies and Tree of Peace symbol to end intertribal warfare, fostering a worldview centered on balance between society, environment, and spirituality.[12] Kanien'kehá:ka society is matrilineal, with descent and clan membership inherited through the mother's line, organizing communities into three primary clans: Bear (Ohkwa:ri), Turtle (A'nó:wara), and Wolf (Okwaho:).[9] Clan mothers hold authority to select and remove chiefs (royaner), ensuring governance aligns with communal welfare and traditional protocols, a system that persists in longhouse communities despite colonial disruptions.[4] This clan structure reinforces identity through exogamous marriage rules, shared responsibilities for territory stewardship, and ceremonies like the midwinter festival, which renew cultural continuity and the Kaianere'kó:wa (Great Law).[12] The Kanyen'kéha language remains a core marker of identity, with revitalization efforts addressing its decline to fewer than 3,000 speakers as of 2016.[13]Language

Linguistic features of Kanien'kéha

Kanien'kéha belongs to the Northern branch of the Iroquoian language family, which includes languages like Oneida, Onondaga, and Cayuga, and is distinguished by its polysynthetic morphology where verbs and nouns combine multiple morphemes to encode predicate-argument structure, tense, aspect, and modality within single words.[13][14] This structure allows a single Kanien'kéha word, such as akwéyikonhroriiohkwa ("they are cleaning their houses"), to convey what requires a full clause in English, reflecting a head-marking grammar that prioritizes verb-internal agreement over separate pronouns or auxiliaries.[13] Phonologically, Kanien'kéha features a modest inventory of eight consonants: voiceless stops /t/ and /k/, affricate /ts/, fricatives /s/ and /h/, nasal /n/, alveolar flap /r/, and glides /w/ and /j/ (with /r/ realized as a flap similar to English "tt" in "butter").[15] Vowels comprise four oral qualities /a, e, i, o/—where /e/ approximates [ɛ]—each occurring in short, long, and nasalized forms, with nasalization marked orthographically by "en" or "on" and phonetically involving vowel height adjustments before nasal consonants.[15][16] Stress falls predictably on heavy syllables (long vowels or those followed by /h/), contributing to rhythmic patterns, while dialectal variations, such as in Kahnawà:ke versus Kanesatake communities, affect vowel realization and cluster simplification without altering core phonemic contrasts.[17] Morphologically, the language distinguishes three word classes: verbs (which serve as predicates and incorporate nouns), nouns (prefixed for possession or classification, e.g., raoti'kówa "her house" with feminine prefix rao-), and particles (invariant elements for adverbs or connectives).[14] Verbs exhibit templatic structure with up to 58 pronominal prefixes (yielding 328 allomorphs) encoding agent-patient relations, such as unified prefixes for dual subjects (tsi- for "we two inclusive") or transitivity-based alternations, alongside suffixes for aspect (e.g., habitual -Ø, punctual -ne) and noun incorporation, as in ionterihwà:ien ("she is dog-walking" from verb root for "walk" incorporating "dog").[18] Nouns lack plural marking on roots but use classifiers or quantifiers, and possession is obligatory via prefixes distinguishing alienable (body parts, kinship) from inalienable forms.[14] Syntactically, Kanien'kéha is flexible in word order, often verb-subject-object (VSO) or verb-initial, with discourse-driven variations, and relies on verb agreement rather than case marking for arguments; particles like tsi ("that") frame clauses, while complex predicates arise from serial verb constructions or light verb incorporation.[20][21] This system underscores causal event encoding through morphological fusion, though revitalization efforts note challenges in documenting dialectal syntax amid fewer than 3,000 fluent speakers as of recent surveys.[17][18]Historical usage and modern revitalization

Prior to European contact in the early 17th century, Kanien'kéha served as the exclusive language of the Mohawk people, essential for oral governance, storytelling, wampum diplomacy, and coordination within the Haudenosaunee Confederacy across their traditional territories in the Mohawk Valley and surrounding regions.[22] [17] During the colonial era, the language remained central to Mohawk social and economic systems, including trade and warfare alliances, though French Jesuit missionaries began documenting it in the mid-1600s through catechisms, grammars, and dictionaries to facilitate religious instruction, marking early European engagement with its polysynthetic structure.[13] Migrations in the 1660s, prompted by conflicts like the Beaver Wars, established the eastern dialect in Canadian communities such as Kahnawà:ke, diverging from western varieties while preserving core usage in kinship, ceremonies, and resistance to assimilation.[13] By the 19th and 20th centuries, Kanien'kéha usage declined sharply due to colonial education policies favoring English and French, residential schooling, and urbanization, reducing intergenerational transmission as parents shifted to dominant languages in households and institutions.[23] This erosion positioned the language as endangered by the late 20th century, with fluent first-language speakers concentrated among elders in reserves, though pockets of daily use persisted in ceremonial contexts.[24] Modern revitalization efforts, accelerating since the 1970s, emphasize immersion to rebuild fluency, with programs prioritizing adult and child acquisition over partial bilingualism. In Kahnawà:ke, the Karihwanoron School launched full Kanien'kéha immersion for pre-kindergarten through elementary students in 1988, producing graduates capable of basic conversational proficiency after sustained exposure.[25] Similarly, Akwesasne's adult immersion program, the first full-time offering there, graduated its inaugural cohort of eight participants in July 2021 after intensive residential training with elders, aiming to create new fluent speakers for community transmission.[26] The Ratiwennóhkwas initiative, launched in 2023, unites first-language elders from six Mohawk communities—including Tyendinaga, Six Nations, and Kahnawà:ke—for weekly sessions teaching youth, addressing dialect variations and elder scarcity. As of the 2016 Canadian census, approximately 2,350 people reported knowledge of Kanien'kéha, though only 1,295 identified it as their mother tongue, with fluent speakers numbering around 1,000 in Akwesasne alone; U.S. figures add several hundred, but overall, fewer than 10% of Mohawk Nation members under 40 are fluent without intervention. [27] Adult immersion models have proven effective for rapid proficiency gains, as evidenced by programs producing second-language speakers who mentor youth, countering prior suppression in church-run schools.[28] These efforts, funded partly by federal grants, focus on digital resources and master-apprentice pairings to sustain causal chains of transmission amid demographic pressures.[29]Territories and Communities

Traditional homelands and migrations

The Kanien'kehá:ka, or Mohawk people, traditionally occupied Kanien'ke, a territory centered in the Mohawk Valley of present-day northeastern New York State, with extensions northward into the St. Lawrence River Valley of southern Quebec and eastern Ontario, eastward along the Hudson River and Lake Champlain to the Richelieu River, southward into northern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and westward to the adjacent lands of the Oneida nation.[1][22] This region, known for its fertile river valleys and proximity to key waterways, supported semi-sedentary longhouse villages reliant on maize agriculture, hunting, and fishing.[1] Archaeological investigations confirm Mohawk presence in the Mohawk Valley from at least the early 16th century, with over four dozen documented village sites reflecting periodic relocations—typically every 10 to 20 years—driven by soil exhaustion from intensive farming, resource depletion, and strategic considerations such as defense against neighboring groups.[30][31] Key 16th-century sites, including those in the middle Mohawk Valley, yielded artifacts like Iroquoian pottery, corn processing tools, and palisade remnants, indicating stable but adaptive settlement patterns rather than nomadic lifestyles.[32][31] These movements were localized within Kanien'ke, facilitating renewal of agricultural lands without necessitating broader territorial shifts.[33] Pre-contact oral traditions, preserved through Haudenosaunee narratives, emphasize continuity in the northeastern woodlands without evidence of large-scale migrations; any earlier dispersals likely involved gradual expansions or contractions within the Iroquoian cultural sphere, predating the formation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy around the 12th to 15th centuries CE as dated by tree-ring analysis of longhouse timbers.[1][30] Historical accounts suggest possible southernward movements into the Mohawk Valley from higher northern elevations, establishing fortified hilltop sites overlooking the river, though these remain interpretive based on site distributions rather than direct textual records.[34]Modern settlements and population distribution

The principal modern communities of the Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawk people) are situated along the Canada–United States border, centered on the St. Lawrence River and extending into northern New York State and southern Quebec. These settlements emerged from historical relocations following colonial conflicts and treaties, with many established in the 18th and 19th centuries on lands granted or purchased near traditional territories. Smaller, independent communities in New York, such as Ganienkeh (established 1974 near Altona) and Kanatsiohareke (reestablished 1993 near Fonda), focus on cultural preservation and sovereignty assertions outside federal reservation systems, though their populations remain limited, typically under 100 residents each based on historical accounts of their founding groups.[35][36] The largest community is Akwesasne, which straddles the international border across New York, Quebec, and Ontario, encompassing the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation in the United States. As of July 2024, it had 13,442 registered members, with approximately 10,226 residing on reserve lands that total over 12,000 residents overall. The U.S. portion, managed by the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, reported a population of 3,657 in the 2023 American Community Survey. Kahnawà:ke, located on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, serves as a major cultural and economic hub, with 11,802 registered members as of July 2025, including 8,125 on reserve. Kanesatà:ke, near Oka in Quebec, has 3,161 registered members, with 1,347 on reserve. These figures reflect registered status under Canadian Indian Act provisions, which may undercount non-registered or urban-dispersed individuals.[37][38][39] Population distribution shows a concentration in Quebec, where over 20,000 Kanien'kehá:ka members reside across communities, compared to several thousand in the U.S. Many Mohawk individuals live off-reserve in nearby cities such as Montreal, Ottawa, and Albany, engaged in industries like construction, gaming, and manufacturing, contributing to a broader diaspora estimated in the tens of thousands worldwide, though precise global totals lack comprehensive enumeration beyond community-level data.[11]| Community | Location | Registered Population (approx., recent) | On-Reserve Residents (approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Akwesasne | NY/Quebec/Ontario border | 13,442 (2024) | 10,226 |

| Kahnawà:ke | Quebec | 11,802 (2025) | 8,125 |

| Kanesatà:ke | Quebec | 3,161 (2025) | 1,347 |

| St. Regis (U.S. part of Akwesasne) | New York | N/A (census: 3,657 in 2023) | N/A |

Pre-Columbian and Early History

Origins within Iroquois Confederacy

The Mohawk, known in their language as Kanien'kehá:ka ("People of the Flint"), formed one of the five original nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, alongside the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca.[1] [40] As the easternmost nation, the Mohawk served as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door," tasked with vigilance against external threats from Algonquian-speaking groups to the east and north.[1] [41] This positional role within the confederacy's longhouse metaphor underscored their strategic importance in maintaining the alliance's eastern flank, with decision-making centered at Onondaga but Mohawk sachems holding veto power in council deliberations.[41] Haudenosaunee oral traditions attribute the confederacy's origins to the Peacemaker (Dekanawida), aided by the Mohawk adoptee Hiawatha and the Onondaga leader Atotarho, who united the warring nations through the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere'kó:wa), a constitution emphasizing consensus, wampum diplomacy, and matrilineal clan structures to end cycles of intertribal vengeance.[42] These accounts, preserved through wampum belts and recited by faithkeepers, describe a pre-contact formation motivated by mutual exhaustion from warfare, with the Mohawk initially resistant but ultimately joining after Hiawatha's influence.[42] However, empirical dating from archaeological and ethnohistorical analysis places the confederacy's effective consolidation later, around 1450–1600 CE, aligning with evidence of synchronized settlement patterns and reduced intra-Iroquoian conflict rather than the traditional oral claim of circa 1142 CE tied to a solar eclipse.[43] [42] Archaeological excavations of Mohawk sites, such as the Moon Site (ca. 1500–1525 CE), Jiminy Hill (ca. 1525–1550 CE), and Shea Site (ca. 1550–1580 CE) in New York's Mohawk Valley, reveal palisaded villages with maize-based economies, longhouse architecture, and artifact distributions indicating cultural continuity and emerging confederative ties through shared pottery styles and absence of warfare markers among core nations by the mid-16th century.[44] [32] These findings support a gradual coalescence driven by defensive needs against Huron and Algonquian rivals, with Mohawk sites showing population nucleation and trade networks predating European contact, though full political unity likely postdated initial cultural alignments.[45] Early 17th-century European records, including Jesuit accounts from 1615 onward, depict the Mohawk already operating within the confederacy framework during initial Dutch interactions.[41]Pre-contact social and economic systems

The Mohawk maintained a matrilineal social organization, wherein clan membership, inheritance, and family lineage were transmitted through the mother's line, fostering extended kinship networks that extended across Haudenosaunee nations.[46][47] Mohawk society centered on three primary clans—Bear, Wolf, and Turtle—each linked to a common female ancestor and symbolized by animal totems representing land or water moieties.[46][48] Clan Mothers, as senior female leaders, presided over clan affairs, preserved cultural identity, selected male sachems (chiefs) for consensus-based roles, and enforced exogamy rules prohibiting marriage within the same clan to maintain alliance-building ties.[46][47][48] Extended matrilineal families resided in longhouses, communal bark-covered dwellings housing multiple related households under the Clan Mother's authority, with sons relocating to their wives' longhouses upon marriage while retaining ties to their birth clan.[47] Local governance operated through clan councils, incorporating input from women's councils, warriors' councils, and elders, with decisions requiring unanimity to ensure collective harmony and prevent internal conflict.[48] As the easternmost Haudenosaunee nation, the Mohawk integrated into the pre-contact Iroquois Confederacy (formed circa 1142–1450 CE), where clan representatives participated in a grand council for intertribal diplomacy, but retained autonomous village-level authority focused on kinship obligations, dispute resolution, and ritual practices.[48] Economically, the Mohawk pursued a mixed subsistence strategy emphasizing horticulture, with women responsible for planting, tending, and harvesting crops in communal fields using hoes fashioned from stone or elk antlers.[49][48] Primary staples included the "Three Sisters" intercropped system of corn (maize), beans, and squash, supplemented by sunflowers and tobacco; men cleared fields annually in late March via controlled burns and stone axes, yielding plots from 10 to hundreds of acres that supported village self-sufficiency but necessitated periodic relocation every 10–20 years due to soil exhaustion from slash-and-burn methods.[49] Men conducted seasonal group hunts of 6–12 individuals targeting deer, bear, beaver, and fowl using drives, traps, and bows, while also fishing rivers; women gathered forest resources like berries, mushrooms, roots, and nuts, with all yields shared communally to buffer scarcity.[49][48] Limited pre-contact trade occurred via kinship networks for prestige goods like wampum shells and flint, reinforcing social bonds without market exchange.[48]Colonial Era Interactions

Initial European contact and trade

The earliest recorded European contact with the Mohawk occurred in July 1609, when French explorer Samuel de Champlain, allied with Algonquin and Huron warriors, encountered a Mohawk war party near Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain.[50] Champlain fired his arquebus, killing at least two Mohawk chiefs and wounding others, which routed the Mohawk and initiated long-term hostility between the French and the Iroquois Confederacy, of which the Mohawk were the easternmost nation.[51] This violent clash stemmed from pre-existing intertribal rivalries over hunting territories, with Champlain's intervention tipping the balance against the Mohawk and establishing a pattern of French-Iroquois antagonism that influenced subsequent alliances.[52] In contrast, initial Dutch interactions with the Mohawk, beginning around 1614, centered on commerce rather than conflict. Dutch traders from the New Netherland colony constructed Fort Nassau on the Hudson River near present-day Albany to facilitate fur exchanges, with Mohawk delegations traveling there to barter beaver pelts—abundant in their Mohawk Valley homeland—for European goods such as metal tools, cloth, and kettles.[53] This post was replaced by Fort Orange in 1624, solidifying the Mohawk's role as primary suppliers in the burgeoning transatlantic beaver fur trade, driven by European demand for felt hats.[54] Mohawk control of eastern access routes positioned them advantageously, enabling direct overland transport of pelts to Dutch posts while excluding rivals like the Mahican.[55] The trade rapidly transformed Mohawk society, introducing firearms and other technologies that enhanced hunting efficiency but also intensified competition for beaver resources, foreshadowing broader conflicts.[56] By the 1620s, Mohawk exchanges at Fort Orange yielded thousands of pelts annually, fostering economic interdependence with the Dutch while exposing the Mohawk to epidemic diseases that halved their population from pre-contact estimates of around 8,000-10,000.[57] These early partnerships prioritized mutual gain over colonization, with Mohawk leaders negotiating terms to maintain autonomy in trade protocols.[1]Beaver Wars and territorial expansion

The Beaver Wars, a protracted series of conflicts from approximately 1620 to 1680, arose from the Mohawk and other Iroquois nations' need to secure new beaver hunting grounds after local populations were depleted by intensive trapping for the European fur trade, compounded by their alliances with Dutch traders who supplied firearms in exchange for pelts.[58] As the easternmost nation in the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and self-designated "Keepers of the Eastern Door," the Mohawk initiated and directed many early offensives to eliminate rivals allied with the French, such as the Mahican, Algonquin, and Huron, thereby gaining access to northern fur-bearing territories.[58] [59] In the 1620s, escalating competition for Dutch trade routes along the Hudson River led to open warfare between the Mohawk and the Mahican, with the Mohawk leveraging superior access to European guns to decisively defeat their rivals by 1628, displacing the Mahican eastward and monopolizing the Albany-area fur trade until the mid-1650s when regional beaver stocks further declined.[54] This victory expanded Mohawk influence over approximately 6,500 square miles of former Mahican territory west of Fort Orange (present-day Albany), securing a steady flow of trade goods that amplified their military advantage in subsequent campaigns.[54] By the 1630s, Mohawk raids extended into the Ottawa Valley against Algonquin groups, intercepting French-bound furs and weakening enemy supply lines.[59] The 1640s marked intensified confederacy-wide assaults, with Mohawk warriors joining Oneida forces in strikes on New France settlements and St. Lawrence Valley allies, while coordinating with Seneca kin in devastating attacks on the Huron-Wendat Confederacy; in 1649, over 1,000 Mohawk and Seneca fighters razed multiple Wendat villages, leading to the confederacy's dispersal and the absorption or flight of its estimated 20,000-30,000 survivors.[59] These operations, fueled by Dutch-supplied muskets since the late 1620s, dismantled French-aligned networks and opened vast hunting expanses in the Great Lakes region, including parts of the Ohio Country by the 1670s.[58] [60] Through these conquests, the Mohawk not only claimed tributary rights over displaced groups like the Neutral and Erie but also incorporated thousands of captives via adoption practices, bolstering their population and labor force for sustained fur procurement; this territorial reach—from the Hudson Valley northward to the St. Lawrence and westward toward the Ohio Valley—positioned the Mohawk as pivotal brokers in the Anglo-French colonial rivalry, though French retaliatory expeditions, such as the 1666 burning of Mohawk villages by the Carignan-Salières Regiment, temporarily disrupted their gains before the 1701 Great Peace of Montreal stabilized boundaries.[59] [60] [58]18th-Century Conflicts and Alliances

French and Indian War involvement

The Mohawk people, as the easternmost nation of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, predominantly allied with the British during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), driven by longstanding fur trade dependencies and territorial rivalries with French-allied tribes. This alignment provided British forces with critical scouting, intelligence, and combat support, particularly in the northern frontier regions of New York and the Champlain Valley. Mohawk warriors, numbering in the hundreds at key engagements, leveraged their knowledge of local terrain to counter French incursions aimed at severing British supply lines to Fort Oswego and beyond.[61][62] A significant internal division emerged among the Mohawks, with Catholic converts residing in mission villages near Montreal, such as Kahnawà:ke, aligning with the French due to religious ties and proximity to French colonial centers. These Canadian Mohawks, estimated at several hundred warriors, joined French expeditions, creating rare instances of intra-tribal conflict. This split reflected broader Haudenosaunee efforts to maintain neutrality under the Two Row Wampum treaty principles but was undermined by Mohawk exposure to British colonial pressures in the Mohawk Valley.[1][63] The Battle of Lake George on September 8, 1755, exemplified Mohawk military contributions and fraternal tensions. British colonial forces under Sir William Johnson, bolstered by approximately 200–300 Mohawk warriors led by sachem Hendrick Theyanoguin (Tiyanoga), clashed with a French army of about 1,500 under Jean-Armand, Baron Dieskau, which included Kahnawà:ke Mohawks. The Mohawks initially provided effective ambush and flanking support, but hesitation arose when facing kin from the Canadian missions, leading some to attempt parleys mid-battle. Hendrick's death during a counterattack—reportedly by French musket fire while rallying troops—marked a severe blow, with Mohawk casualties contributing to overall British losses of around 216 killed and 137 wounded. The engagement halted French advances temporarily and solidified British control over the lake approach to Crown Point.[64][65][66] Following Lake George, Mohawk participation persisted in British campaigns, including raids on French posts and support for the 1758 capture of Louisbourg and Fort Frontenac, though numbers dwindled due to losses and war weariness. By the war's 1763 conclusion under the Treaty of Paris, Mohawk alliances yielded British promises of protection against encroachments, yet foreshadowed postwar land disputes that eroded these gains. Their strategic value to the British stemmed from proven efficacy in irregular warfare, contrasting with French reliance on less cohesive native coalitions.[62][61]American Revolutionary War divisions

The Mohawk nation, as "keepers of the eastern door" of the Iroquois Confederacy, predominantly allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775–1783), driven by historical diplomatic ties, British frontier forts offering security, and promises to curb settler encroachment on indigenous lands.[67][68] This stance contrasted with the Confederacy's overall fracture, where the Oneida and Tuscarora nations supported the American Patriots, while the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga backed the Crown, leading to inter-tribal conflict and raids that devastated shared territories.[69][68] Under the leadership of Joseph Brant (Thayendanegea), a Mohawk war chief and British captain, warriors served as scouts, spies, and raiders, organizing Brant's Volunteers—a unit comprising Mohawks and Loyalist settlers—to target Patriot frontier communities.[70][69] Key actions included participation in Barry St. Leger's 1777 expedition, the Battle of Oriskany on August 6, 1777, where Mohawks fought alongside British and other Iroquois against American and Oneida forces, and the raid on German Flatts on September 17, 1778.[70][69] Brant's efforts convinced four of the six Iroquois nations to align with Britain, though neutrality pleas from some Confederacy members were overridden by wartime pressures.[69][68] Internal divisions within the Mohawk nation were limited compared to the broader Confederacy split, with most clans and leaders unified under Brant's influence and the influence of his sister Molly Brant, who leveraged kinship networks to sustain Loyalist support.[68] Individual defections occurred amid the chaos of frontier civil war, but the Mohawks' cohesive pro-British orientation reflected calculated self-preservation against American expansionism, as evidenced by prior British policies like the 1763 Proclamation restraining colonial settlement.[67][68] This alignment, however, exposed Mohawk communities to retaliatory campaigns, such as the 1779 Sullivan Expedition, which razed over 40 Iroquois villages and crops, forcing many to seek refuge at British-held Fort Niagara.[67][70]Post-Independence Developments

Loyalist migrations and Canadian settlements

Following the American Revolutionary War, Mohawk communities allied with the British faced expulsion and land confiscation in the newly independent United States, prompting migrations northward to British-controlled territories in Canada beginning in 1783.[71] Joseph Brant, a prominent Mohawk leader, negotiated land grants from British officials to facilitate resettlement for Loyalist Iroquois, including Mohawk, under the Haldimand Proclamation of 1784, which allocated approximately 950,000 acres along the Grand River in present-day Ontario to the Six Nations.[72] Starting in October 1784, Brant oversaw the relocation of around 1,800 to 2,241 Mohawk and other Iroquois individuals to this tract, establishing the foundation for the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve, where a Mohawk village developed near the Mohawk Chapel and Brant's residence.[73] [74] Concurrent with the Grand River settlement, a group of approximately 20 Mohawk families from the Fort Hunter band, displaced from the Mohawk Valley, received a grant of 92,700 acres on the Bay of Quinte in 1784, forming the Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory in eastern Ontario.[75] This tract, deeded by Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe in 1793 via the Crawford Purchase, became a key Loyalist Mohawk enclave, with initial settlements focused on agriculture and fishing along the lakefront.[71] These migrations preserved Mohawk cultural continuity amid displacement, though subsequent land surrenders reduced reserve sizes; for instance, Tyendinaga shrank to about 7,362 hectares by the 19th century due to sales and encroachments.[71] British compensation for Loyalist Mohawk included annuity payments and tools, reflecting recognition of their wartime service, such as in raids and battles alongside British forces.[76] By the early 1790s, these Canadian settlements had stabilized, with Mohawk populations integrating traditional governance while adapting to new environments, marking a pivotal shift from New York Valley homelands to Ontario and Quebec frontiers.[73]19th-century treaties and land losses

In Canada, the Mohawk-inhabited Grand River territory, granted under the 1784 Haldimand Proclamation as approximately 950,000 acres to the Six Nations for their loyalty to the British Crown, underwent substantial reductions in the 19th century through unauthorized grants and expropriations. In 1807, 30,800 acres in Block No. 5 of Moulton Township were allocated to the Earl of Selkirk without Six Nations consent, exemplifying early encroachments that diminished communal holdings.[77] Further losses occurred between 1829 and 1835 when about 2,500 acres were taken for the Welland Canal without compensation to the Six Nations, prioritizing infrastructure development over Indigenous title.[77] Additionally, starting in 1834, the Grand River Navigation Company exploited Six Nations lands and funds without proper authorization, contributing to financial and territorial erosion when the venture collapsed.[77] These actions, often lacking broad consensus among clan mothers and chiefs, reflected settler expansion pressures and inadequate enforcement of perpetual grant terms, reducing the effective reserve to roughly 46,000 acres by mid-century.[77] In the United States, the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation faced illegal land acquisitions by New York State in the 1820s, contravening the 1790 Nonintercourse Act that mandated federal oversight for tribal land transfers. State purchases in 1824 and 1825 encompassed around 2,000 acres, including the Hogansburg Triangle (also known as the Bombay Triangle) and a one-square-mile parcel in Massena, located in St. Lawrence and Franklin counties.[78] These transactions bypassed congressional ratification required under federal law, stemming from the 1796 Treaty with the Seven Nations of Canada that had reserved the original reservation boundaries.[79] A 2022 federal court ruling affirmed the illegality of these takings, highlighting New York's direct dealings with select Mohawk individuals without communal or national approval, which perpetuated disputes over sovereignty and title integrity.[78] The U.S. Department of Justice later endorsed the Mohawk claims, noting thousands of acres affected across multiple invalid sales.[79]20th-Century Transformations

World Wars military contributions

During the First World War, Mohawk individuals from Canadian communities including Kahnawà:ke and Six Nations voluntarily enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force despite initial restrictions on Indigenous recruitment. Approximately 50 Mohawks from Kahnawà:ke joined the 114th Battalion (Grand River), raised primarily in the Six Nations territory, contributing to infantry operations on the Western Front.[80] Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture, a Mohawk woman from the Six Nations of the Grand River, overcame barriers to nursing training in the United States and served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps from 1917 to 1919, treating wounded soldiers in France; she was the first Indigenous Canadian to become a registered nurse.[81] Dr. Gilbert Monture, also Mohawk from Six Nations, held a commission as an officer and served in administrative roles supporting Canadian forces.[82] In the Second World War, Mohawk service expanded across Canadian and U.S. forces, with notable contributions in combat, signals intelligence, and independent Haudenosaunee declarations of war. On June 13, 1942, the Iroquois Confederacy—including the Mohawk Nation—formally declared war on Germany, Italy, and Japan from the steps of the U.S. Capitol, asserting sovereignty while aligning against the Axis powers.[83] Mohawk code talkers from Akwesasne, such as Louis Levi Oakes, enlisted in the U.S. Army in January 1943 and transmitted secure messages in the Mohawk language, supporting General George Patton's Third Army during the European invasion; Oakes was wounded in action, received the Purple Heart, and was the last surviving Mohawk code talker when he died in 2019.[84] In Canadian service, Huron Brant, a Mohawk from Ontario, earned the Military Medal on July 15, 1943, for displaying courage under fire while serving with the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment during the Allied invasion of Sicily.[85] Dr. Gilbert Monture continued his service, acting as executive officer in combined Canadian-American-British operations.[82] These efforts reflected a pattern of high voluntary enlistment rates from Mohawk reserves, building on historical alliances with Britain and emphasizing individual and communal commitment to the Allied cause.[86]Urban migration and ironworking profession