Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

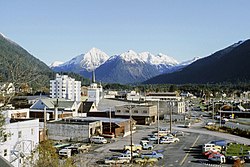

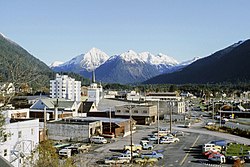

Sitka, Alaska

View on Wikipedia

Sitka (Tlingit: Sheetʼká; Russian: Ситка) is a unified city-borough in the southeast portion of the U.S. state of Alaska. It was under Russian rule from 1799 to 1867. The city is situated on the west side of Baranof Island and the south half of Chichagof Island in the Alexander Archipelago of the Pacific Ocean (part of the Alaska Panhandle). As of the 2020 census, Sitka had a population of 8,458,[4] making it the fifth-most populated city in the state.

Key Information

With a consolidated land area of 2,870.3 square miles (7,434 square kilometers) and total area (including water) of 4,811.4 square miles (12,461 km2), Sitka is the largest city by total area in the U.S.

History

[edit]As part of Russia, it was known as New Archangel (Russian: Ново-Архангельск, romanized: Novo-Arkhangelsk).[5]

The current name, Sitka (derived from Sheetʼká, a contraction of the Tlingit Shee Atʼiká),[6] means "People on the Edge of Shee", with Shee being the Tlingit name for Baranof Island (the Tlingit name for the island is Sheetʼ-ká Xʼáatʼl but is often contracted to Shee).[5]

Russian America

[edit]

Russian explorers settled Old Sitka in 1799, naming it the Fort of Archangel Michael (Russian: форт Архангела Михаила, romanized: Fort Arkhangela Mikhaila). The governor of Russian America, Alexander Baranov, arrived under the auspices of the Russian-American Company, a colonial trading company chartered by Russian emperor Paul I. In June 1802, Tlingit warriors destroyed the original settlement, killing many of the Russians, with only a few managing to escape.[7]: 37–39 Baranov was forced to levy 10,000 rubles in ransom to Captain Barber of the British sailing ship Unicorn for the safe return of the surviving settlers.[8][9]

Baranov returned to Sitka in August 1804 with a large force, including Yuri Lisyansky's Neva. The ship bombarded the Tlingit fortification on the 20th but was not able to cause significant damage. The Russians then launched an attack on the fort and were repelled. Following two days of bombardment, the Tlingit "hung out a white flag" on the 22nd, deserting the fort on the 26th.[7]: 44–49

Following their victory at the Battle of Sitka in October 1804, the Russians established the settlement called New Archangel, named after Arkhangelsk. As a permanent settlement, New Archangel became the largest city in the region. The Tlingit re-established their fort on the Chatham Strait side of Peril Strait to enforce a trade embargo with the Russian establishment. In 1808, with Baranov still governor, Sitka was designated the capital of Russian America.[10]

Bishop Innocent lived in Sitka after 1840. He was known for his interest in education, and his house, the Russian Bishop's House, parts of which served as a schoolhouse, has since been restored by the National Park Service as part of the Sitka National Historical Park.

The original Cathedral of Saint Michael was built in Sitka in 1848 and became the seat of the Russian Orthodox bishop of Kamchatka, the Kurile and Aleutian Islands, and Alaska. The original church burned to the ground in 1966, losing its handmade bells, the large icon of the Last Supper that decorated the top of the royal doors, and the clock in the bell tower. Also lost was the large library containing books in the Russian, Tlingit, and Aleut languages. Although the church was restored to its original appearance, one exception was its clock face, which is black in photographs taken before 1966, but white in subsequent photos.[11]

Swedes, Finns and other nationalities of Lutherans worked for the Russian-American Company,[12] which led to the creation of a Lutheran congregation. The Sitka Lutheran Church building was built in 1840 and was the first Protestant church on the Pacific coast. After the transition to American control, following the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States in 1867, the influence of other Protestant religions increased, and Saint-Peter's-by-the-Sea Episcopal Church was consecrated as "the Cathedral of Alaska" in 1900.[13]

Territorial Alaska

[edit]

Sitka was the site of the transfer ceremony for the Alaska Purchase on October 18, 1867. Russia was going through economic and political turmoil after it lost the Crimean War to Britain, France, and the Ottoman Empire in 1856, and decided it wanted to sell Alaska before British Canadians tried to conquer the territory. Russia offered to sell it to the United States. Secretary of State William Seward had wanted to purchase Alaska for quite some time, as he saw it as an integral part of Manifest Destiny and America's reach to the Pacific Ocean.[14] While the agreement to purchase Alaska was made in April 1867, the actual purchase and transfer of control took place on October 18, 1867. The cost to purchase Alaska was $7.2 million, at 2 cents per acre.

Sitka served as both the U.S. Government Capital of the Department of Alaska (1867–1884) and District of Alaska (1884–1906). The seat of government was relocated north to Juneau in 1906 due to the declining economic importance of Sitka relative to Juneau, which gained population in the Klondike Gold Rush.

Alaska Native Brotherhood, Alaska Native Sisterhood

[edit]The Alaska Native Brotherhood was founded in Sitka in 1912 to address racism against Alaska Native people in Alaska.[15] By 1914, the organization had constructed the Alaska Native Brotherhood Hall on Katlian Street, which was named after a Tlingit war chief in the early period of Russian colonization.[16]

World War II

[edit]In 1937, the United States Navy established the first seaplane base in Alaska on Japonski Island, across the Sitka Channel from the town.[17] In 1941, construction began on Fort Ray, an army garrison to protect the naval air station.[17] Both the army and navy remained in Sitka until the end of WWII, when the army base was put into caretaker status. The naval station in Sitka was deactivated in June 1944.[17] A shore boat system was then established to transfer the approximately 1,000 passengers a day until the O'Connell Bridge was built in 1972.[18]

Economy

[edit]The Alaska Pulp Corporation was the first Japanese investment in the United States after WWII. In 1959, it began to produce pulp harvested from the Tongass National Forest under a 50-year contract with the US Forest Service.[19] At its peak, the mill employed around 450 people before closing in 1993.

Sitka's Filipino community established itself in Sitka before 1929. It later became institutionalized as the Filipino Community of Sitka in 1981.[20]

Gold mining and fish canning paved the way for the town's initial growth. Today Sitka encompasses portions of Baranof Island and the smaller Japonski Island, which is connected to Baranof Island by the John O'Connell Bridge (which uses the cable-stayed suspension method as its means of support). Japonski Island is home to Sitka Rocky Gutierrez Airport (IATA: SIT; ICAO: PASI), the Sitka branch campus of the University of Alaska Southeast, Mt. Edgecumbe High School (a state-run boarding school for rural Alaskans), Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium's Mt. Edgecumbe Hospital, U.S. Coast Guard Air Station Sitka, and the port and facilities for the USCGC Kukui.[21]

Sitka has become a destination for visiting cruise ships.[22] In May 2025, a special referendum on restricting cruise ship tourism took place in the town with 3,000 votes cast.[22] The referendum was less than 10 percent from their all-time high for a special election and some 73% of the voters rejected the limits on cruise ships with only 27% voting in favor of the proposed limits.[22]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough is the largest incorporated city by area in the U.S., with a total area of 4,811 square miles (12,460.4 km2), of which 2,870 square miles (7,400 km2) is land and 1,941 square miles (5,030 km2), comprising 40.3%, is water. As a comparison, this is almost four times the size of the state of Rhode Island.

Sitka displaced Juneau, Alaska, as the largest incorporated city by area in the United States upon the 2000 incorporation with 2,874 square miles (7,440 km2) of incorporated area. Juneau's incorporated area is 2,717 square miles (7,040 km2). Jacksonville, Florida, is the largest city in area in the contiguous 48 states at 758 square miles (1,960 km2).

Climate

[edit]

Sitka has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb) with moderate, but generally cool, temperatures and abundant precipitation. The average annual precipitation is 131.74 inches (3,350 mm); average seasonal snowfall is 33 inches (84 cm), falling on 233 and 19 days, respectively. The mean annual temperature is 45.3 °F (7.4 °C), with monthly means ranging from 36.4 °F (2.4 °C) in January to 57.2 °F (14.0 °C) in August.

The climate is relatively mild when compared to other parts of the state. Only 5.1 days per year see highs at or above 70 °F (21 °C); conversely, there are only 10 days with the high not above freezing.[23] The winters are extremely mild compared to inland areas of similar and much more southerly parallels, due to the intense maritime moderation. The relatively mild nights ensure that four months stay above the 50 °F (10 °C) isotherm that normally separates inland areas from being boreal in nature. Due to the mild winter nights, hardiness zone is high for the latitude (from 6b to 8a).

The highest temperature ever recorded was 88 °F (31.1 °C) on July 30, 1976, and July 31, 2020. The lowest temperature ever recorded was −1 °F (−18.3 °C) on February 16–17, 1948.[23]

| Climate data for Sitka, Alaska (Japonski Island, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1944–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 60 (16) |

61 (16) |

67 (19) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

83 (28) |

88 (31) |

84 (29) |

77 (25) |

70 (21) |

65 (18) |

65 (18) |

88 (31) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 50.9 (10.5) |

50.8 (10.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

60.1 (15.6) |

65.8 (18.8) |

69.5 (20.8) |

70.8 (21.6) |

71.4 (21.9) |

67.1 (19.5) |

58.5 (14.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

50.6 (10.3) |

75.6 (24.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 40.5 (4.7) |

41.2 (5.1) |

42.5 (5.8) |

48.1 (8.9) |

53.3 (11.8) |

57.6 (14.2) |

60.4 (15.8) |

61.8 (16.6) |

57.9 (14.4) |

50.8 (10.4) |

44.3 (6.8) |

41.5 (5.3) |

50.0 (10.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.5 (2.5) |

36.7 (2.6) |

37.5 (3.1) |

42.6 (5.9) |

48.1 (8.9) |

53.0 (11.7) |

56.5 (13.6) |

57.3 (14.1) |

53.2 (11.8) |

46.4 (8.0) |

40.0 (4.4) |

37.5 (3.1) |

45.4 (7.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

32.1 (0.1) |

32.5 (0.3) |

37.2 (2.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

48.3 (9.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

52.9 (11.6) |

48.5 (9.2) |

41.9 (5.5) |

35.8 (2.1) |

33.4 (0.8) |

40.9 (4.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 18.1 (−7.7) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

35.9 (2.2) |

42.1 (5.6) |

47.5 (8.6) |

47.1 (8.4) |

40.1 (4.5) |

32.0 (0.0) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

13.3 (−10.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 0 (−18) |

−1 (−18) |

4 (−16) |

15 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

35 (2) |

41 (5) |

34 (1) |

31 (−1) |

20 (−7) |

2 (−17) |

1 (−17) |

−1 (−18) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 8.22 (209) |

5.93 (151) |

5.60 (142) |

4.31 (109) |

3.81 (97) |

2.92 (74) |

4.62 (117) |

7.25 (184) |

11.69 (297) |

11.78 (299) |

9.91 (252) |

8.43 (214) |

84.47 (2,146) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.5 (24) |

8.0 (20) |

4.9 (12) |

0.9 (2.3) |

trace | 0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

4.7 (12) |

4.0 (10) |

32.3 (82) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 21.2 | 16.9 | 18.4 | 17.5 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 18.9 | 19.4 | 22.4 | 23.7 | 22.0 | 21.6 | 235.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 19.0 |

| Source: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[23][24][25] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Sitka, Alaska (Hidden Falls, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1992–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

57 (14) |

53 (12) |

66 (19) |

73 (23) |

85 (29) |

83 (28) |

83 (28) |

69 (21) |

61 (16) |

54 (12) |

51 (11) |

85 (29) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 44.9 (7.2) |

44.9 (7.2) |

46.7 (8.2) |

53.7 (12.1) |

63.4 (17.4) |

66.7 (19.3) |

69.2 (20.7) |

68.8 (20.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

47.4 (8.6) |

44.4 (6.9) |

72.5 (22.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 34.7 (1.5) |

35.7 (2.1) |

38.5 (3.6) |

45.7 (7.6) |

53.3 (11.8) |

57.9 (14.4) |

59.9 (15.5) |

59.6 (15.3) |

54.7 (12.6) |

46.8 (8.2) |

39.0 (3.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

46.8 (8.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.3 (−0.4) |

32.0 (0.0) |

34.0 (1.1) |

39.6 (4.2) |

46.8 (8.2) |

52.3 (11.3) |

55.0 (12.8) |

55.0 (12.8) |

50.5 (10.3) |

43.1 (6.2) |

35.6 (2.0) |

32.9 (0.5) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.8 (−2.3) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

33.5 (0.8) |

40.3 (4.6) |

46.6 (8.1) |

50.2 (10.1) |

50.4 (10.2) |

46.3 (7.9) |

39.4 (4.1) |

32.2 (0.1) |

29.9 (−1.2) |

37.8 (3.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.5 (−9.7) |

17.1 (−8.3) |

19.9 (−6.7) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

34.1 (1.2) |

40.5 (4.7) |

45.3 (7.4) |

45.4 (7.4) |

39.1 (3.9) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 4 (−16) |

6 (−14) |

6 (−14) |

15 (−9) |

28 (−2) |

35 (2) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

29 (−2) |

13 (−11) |

11 (−12) |

3 (−16) |

3 (−16) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 13.57 (345) |

9.27 (235) |

10.66 (271) |

8.11 (206) |

4.77 (121) |

4.03 (102) |

5.06 (129) |

6.90 (175) |

12.94 (329) |

15.96 (405) |

18.98 (482) |

17.83 (453) |

128.08 (3,253) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 29.7 (75) |

20.0 (51) |

21.1 (54) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

11.5 (29) |

22.8 (58) |

106.2 (269.8) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 21.1 | 13.2 | 20.4 | 16.9 | 13.1 | 15.6 | 14.9 | 12.8 | 20.5 | 22.0 | 23.0 | 23.6 | 217.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.1 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 6.6 | 28.5 |

| Source: NOAA[23][26] | |||||||||||||

This graph was using the legacy Graph extension, which is no longer supported. It needs to be converted to the new Chart extension. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Geology

[edit]

Mount Edgecumbe, a 3,200-foot (980 m) "historically active"[27] stratovolcano, is located on southern Kruzof Island, approximately 24 km (15 mi) west of Sitka and can be seen from the city on a clear day.

On April 22, 2022, the Alaska Volcano Observatory reported that:

[a] swarm of earthquakes was detected in the vicinity of Mount Edgecumbe volcano beginning on Monday, April 11, 2022. There were hundreds of small quakes in the swarm, though the large majority were too small to locate. Over the past few days, earthquake activity has declined and is currently at background levels.

[...]

The recent swarm inspired an in-depth analysis of the last 7.5 years of ground deformation detectable with radar satellite data. Analysis of these data from recent years reveals a broad area, about 17 km (11 mi) in diameter, of surface uplift centered about 2.5 km (1.6 mi) to the east of Mt Edgecumbe. This uplift began in August 2018 and has been continuing to the present at a rate of up to 8.7 cm/yr (3.4 in/yr) in the center of the deforming area. Deformation has been constant since 2018, and there has not been an increase with the recent earthquake activity. The total deformation since 2018 is about 27 cm (11 in). [...] The coincidence of earthquakes and ground deformation in time and location suggests that these signals are likely due to the movement of magma beneath Mount Edgecumbe, as opposed to tectonic activity. Initial modeling of the deformation signal shows that it is consistent with an intrusion of new material (magma) at about 5 km (3.1 mi) below sea level. The earthquakes likely are caused by stresses in the crust due to this intrusion and the substantial uplift that it is causing.

Intrusions of new magma under volcanoes do not always result in volcanic eruptions. The deformation and earthquake activity at Edgecumbe may cease with no eruption occurring. If the magma rises closer to the surface, this would lead to changes in the deformation pattern and an increase in earthquake activity. Therefore, it is very likely that if an eruption were to occur it would be preceded by additional signals that would allow advance warning.[28]

Adjacent boroughs and census areas

[edit]- Hoonah-Angoon Census Area, Alaska – north, northeast

- Prince of Wales–Hyder Census Area, Alaska – southeast

National protected areas

[edit]- Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge (part of Gulf of Alaska unit)

- Sitka National Historical Park

- Tongass National Forest (part)

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 916 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,190 | 29.9% | |

| 1900 | 1,396 | 17.3% | |

| 1910 | 1,039 | −25.6% | |

| 1920 | 1,175 | 13.1% | |

| 1930 | 1,056 | −10.1% | |

| 1940 | 1,987 | 88.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,985 | −0.1% | |

| 1960 | 3,237 | 63.1% | |

| 1970 | 3,370 | 4.1% | |

| 1980 | 7,803 | 131.5% | |

| 1990 | 8,588 | 10.1% | |

| 2000 | 8,835 | 2.9% | |

| 2010 | 8,881 | 0.5% | |

| 2020 | 8,458 | −4.8% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 8,355 | [29] | −1.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] 2010-2020[4] | |||

1880 and 1890 censuses

[edit]Sitka first reported on the 1880 census as an unincorporated village. Of 916 residents, there were 540 Tlingit, 219 Creole (Mixed Russian and Native) and 157 Whites reported.[31] It was the largest community in Alaska at that census. In 1890, it fell to second place behind Juneau. It reported 1,190 residents, of whom 861 were Native, 280 were White, 31 were Asian, 17 Creole, and 1 Other.[32] In 1900, it fell to 4th place behind Nome, Skagway and Juneau. It did not report a racial breakdown.[33]

1910 and 1920 censuses

[edit]In 1910, Sitka was reported as two separate communities based on race: the village with mostly non-natives (population 539) and the part of the village with natives (population 500).[34] Separately, they placed as the 15th and 17th largest communities. United, they would be 8th largest. For the purposes of comparison and the fact that the village was not officially politically/racially divided except by the census bureau report, the combined total (1,039) is reported on the historic population list. In 1913, Sitka was incorporated as a city, rendering the division by the census bureau for 1910 moot. In 1920, Sitka became the 4th largest city in the territory.[35] In 1930, it fell to 7th place with 1,056 residents. Of those, 567 reported as Native, 480 as White and 9 as Other.[36] In 1940, it rose to 5th place, but did not report a racial breakdown.[37]

1950 and 1960 censuses

[edit]In 1950, it reported as the 9th largest community in Alaska (6th largest incorporated city).[38] It did not report a racial breakdown. At statehood in 1960, it became the 6th largest community (5th largest incorporated city). With the annexations increasing its population to 3,237, it reported a White majority for its first time: 2,160 Whites, 1,054 Others (including Natives) and 23 Blacks.[39] In 1970, it fell to 14th place overall (though 7th largest incorporated city) with 3,370 residents. Of those, 2,503 were White, 676 Native Americans, 95 Others, 74 Asians and 22 Blacks.[40] In 1980, Sitka rose to 4th largest city with 7,803 residents (of whom 5,718 were non-Hispanic White, 1,669 were Native American, 228 were Asian, 108 were Hispanic (of any race), 87 were Other, 44 were Black and 7 were Pacific Islander).[41]

1990 and 2000 censuses

[edit]In 1990, Sitka fell to 5th largest (4th largest incorporated) with 8,588 residents. 6,270 were non-Hispanic White; 1,797 were Native American; 315 were Asian; 209 were Hispanic (of any race); 60 were Other; 39 were Black and 18 Pacific Islanders.[42] In 2000, Sitka retained its 5th largest (and 4th largest incorporated) position. In 2010, it slipped to 7th largest community overall (but still remained the 4th largest incorporated city).

2010 census

[edit]As of the census of 2010, there were 8,881 people living in the borough. The racial makeup of the borough, based on one race alone or in combination with one or more other races, was, 64.6% White (including White Hispanic and Latino Americans), 1% Black or African American, 24.6% Native American, 8.1% Asian, 0.9% Pacific Islander, 1.8% from other races. In addition, 4.9% of the population were Hispanic and Latino Americans of any race.

There were 3,545 households, out of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.5% were married couples living together, 10.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 6.1% had a male householder with no wife present, and 37.6% were non-families. The average household size was 2.43 and the average family size was 3.01.[43]

2020 census

[edit]| Race (NH = Non-Hispanic) | % 2020[44] | % 2010[45] | % 2000[46] | Pop 2020 | Pop 2010 | Pop 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 59.7% | 63.5% | 67.1% | 5,050 | 5,641 | 5,927 |

| Black alone (NH) | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 37 | 43 | 24 |

| American Indian alone (NH) | 14.3% | 16.2% | 18.1% | 1,206 | 1,442 | 1,597 |

| Asian alone (NH) | 6.8% | 5.7% | 3.7% | 573 | 509 | 329 |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | 14 | 29 | 31 |

| Other race alone (NH) | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.2% | 53 | 11 | 17 |

| Multiracial (NH) | 12.1% | 8.7% | 7% | 1,024 | 769 | 620 |

| Hispanic/Latino (any race) | 5.9% | 4.9% | 3.3% | 501 | 437 | 290 |

Economy

[edit]In 2010, Sitka's two largest employers were the Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC), employing 482 people, and the Sitka School District, which employs 250 people. However, there are more people employed in the seafood industry than in any other sector. An estimated 18% of Sitka's population earns at least a portion of their income from fishing and seafood harvesting and processing. Many Sitkans hunt and gather subsistence foods such as fish, deer, berries, seaweeds and mushrooms for personal use.[48]

Within the total 2010 population of 8,881 residents, an estimated 7,161 were over 16 years of age. Of residents aged 16 and over, an estimated 4,692 were employed within the civilian labor force, 348 were unemployed (looking for work), 192 were employed in the armed forces (U.S. Coast Guard), and 1,929 were not in the labor force. The average unemployment rate between 2006 and 2010 was 6.9%. The median household income in 2010 inflation adjusted dollars was $62,024. An estimated 4.3% of all families / 7% of all residents had incomes below the poverty level "in the past twelve months"(2010).[49]

Sitka's electrical power is generated by dams at Blue Lake and Green Lake, with supplemental power provided by burning diesel when electric demand exceeds hydro capacity. In December 2012 the Blue Lake Expansion project began, which added 27 percent more electricity for the residents of Sitka. The project was completed in November 2014.[50]

Port

[edit]

Sitka is the 6th largest port by value of seafood harvest in the United States.[48] International trade is relatively minor, with total exports and imports valued at $474,000 and $146,000, respectively, in 2005 by the American Association of Port Authorities.[51] The port has the largest harbor system in Alaska with 1,347 permanent slips.

During Russian rule, Sitka was a busy seaport on the west coast of North America,[52] mentioned a number of times by Dana in his popular account of an 1834 sailing voyage Two Years Before the Mast. After the transfer of Alaska to U.S. rule, the Pacific Coast Steamship Company began tourist cruises to Sitka in 1884. By 1890, Sitka was receiving 5,000 tourist passengers a year.[53]

Old Sitka Dock,[54] located at Halibut Point, one mile south of the Old Sitka State Historical Park, commemorating the 1800s Russian settlement, and six miles north of downtown Sitka, is a private deep water port offering moorage facilities.[55] A 470-foot-long floating dock for vessels up to 1100 feet was constructed there by its owners in 2012 and was first used in 2013.[56] In Spring 2016, Holland America Line agreed to dock its ships at the Old Sitka Dock. [57] Since then, the majority of the cruise ships calling on Sitka berth at the Old Sitka Dock, with the remainder anchoring offshore in Crescent Harbor and tendering their passengers to downtown Sitka. In the 2017 season, there were 136 cruise ship calls at Sitka with more than 150,000 passengers in total; of these fewer than 30,000 were tendered.[58] The number of cruise ships visitors to Sitka more than doubled over two seasons in the years 2022 and 2023.[22] At its peak, the city can receive some 13,000 visitors a day, exceeding the number of residents.[22]

The United States Coast Guard plans to homeport one of its Sentinel-class cutters in Sitka.[56]

Arts and culture

[edit]There are 22 buildings and sites in Sitka that appear in the National Register of Historic Places.[59]

On October 18, Alaska celebrates Alaska Day to commemorate the Alaska purchase. The City of Sitka holds an annual Alaska Day Festival. This week-long event includes a reenactment ceremony of the signing of the Alaska purchase, as well as interpretive programs at museums and parks, special exhibits, aircraft displays and film showings, receptions, historic sites and buildings tours, food, prose writing contest essays, Native and other dancing, and entertainment and more. The first recorded Alaska Day Festival was held in 1949.[60]

Government

[edit]| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 1960 | 982 | 46.28% | 1,140 | 53.72% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1964 | 629 | 28.59% | 1,571 | 71.41% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 1,023 | 44.29% | 1,148 | 49.70% | 139 | 6.02% |

| 1972 | 1,280 | 52.61% | 1,080 | 44.39% | 73 | 3.00% |

| 1976 | 1,559 | 58.41% | 1,004 | 37.62% | 106 | 3.97% |

| 1980 | 1,862 | 53.00% | 1,212 | 34.50% | 439 | 12.50% |

| 1984 | 2,380 | 61.09% | 1,403 | 36.01% | 113 | 2.90% |

| 1988 | 2,232 | 54.89% | 1,720 | 42.30% | 114 | 2.80% |

| 1992 | 1,741 | 37.79% | 1,695 | 36.79% | 1,171 | 25.42% |

| 1996 | 1,823 | 42.10% | 1,732 | 40.00% | 775 | 17.90% |

| 2000 | 2,067 | 48.20% | 1,484 | 34.61% | 737 | 17.19% |

| 2004 | 1,726 | 47.59% | 1,737 | 47.89% | 164 | 4.52% |

| 2008 | 2,129 | 46.00% | 2,355 | 50.89% | 144 | 3.11% |

| 2012 | 1,832 | 41.49% | 2,340 | 53.00% | 243 | 5.50% |

| 2016 | 1,830 | 40.89% | 2,135 | 47.71% | 510 | 11.40% |

| 2020 | 1,745 | 43.29% | 2,124 | 52.69% | 162 | 4.02% |

| 2024 | 1,659 | 42.92% | 2,057 | 53.22% | 149 | 3.86% |

The City and Borough of Sitka is a Unified Home Rule[63][64] city. The home rule charter of the City and Borough of Sitka was adopted on December 2, 1971,[65] for the region of the Greater Sitka Borough, which included Japonski Island and Port Alexander and Baranof Warm Springs on Baranof Island. The city was incorporated on September 24, 1963.[66] On October 23, 1973, the city of Port Alexander was detached from the borough.[67]

Police

[edit]Education

[edit]Colleges and universities

[edit]Sitka hosts one active post-secondary institution, the University of Alaska Southeast-Sitka Campus, located on Japonski Island in an old World War II hangar. Sheldon Jackson College, a small Presbyterian-affiliated private college, suspended operations in June 2007, after several years of financial stress.[68] Outer Coast College, a private liberal arts college established in 2015, is currently in development as an undergraduate institution founded on the former campus of Sheldon Jackson College.

Schools

[edit]

The Sitka School District, the designated public school district,[69] runs several schools in Sitka, including Sitka High School and Pacific High School, as well as the town's only middle school, Blatchley Middle School. It also runs a home school assistance program through Terry's Learning Center.

Mt. Edgecumbe High School, a State of Alaska-run boarding high school for rural, primarily Native students, is located on Japonski Island adjacent to University of Alaska Southeast.

One private school is available in Sitka: Sitka Adventist School.[70]

Alaska State Trooper Academy

[edit]The Alaska State Trooper Academy – the academy for all Alaska State Troopers – is located in Sitka.

Libraries

[edit]Sitka Public Library, formerly Kettleson Memorial Library, is the public library for Sitka. It receives about 100,000 guests annually and houses a collection of 75,000 books, audiobooks, music recordings, reference resources, videos (DVD and VHS), as well as an assortment of Alaskan and national periodicals. Its annual circulation is 133,000. The library is well known by visitors for its view. The large windows in front of the reading area look south across Eastern Channel towards the Pyramids.

Until its closing, Sitka was also home to Stratton Library, the academic library of Sheldon Jackson College.[71]

Media

[edit]Sitka is served by the Daily Sitka Sentinel, one of the few remaining independently owned daily newspapers in the state. Sitka also receives circulation of the Capital City Weekly, a weekly regional newspaper based out of Juneau.

Alaska's first newspaper following the Alaska purchase, the Sitka Times, was published by Barney O. Ragan on September 19, 1868. Only four issues were published that year, as Ragan cited a lack of resources available at the time. The paper resumed publishing the following year as the Alaska Times. In 1870, it moved to Seattle, where the year following it was renamed the Seattle Times (not to be confused with the modern-day newspaper of the same name).[72]

Radio

[edit]Sitka has three radio stations, public radio station KCAW (Raven Radio), and commercial radio stations KIFW, and KSBZ. Sitka previously had a Presbyterian Church owned KSEW.

Television

[edit]KTNL-TV (MeTV) broadcasts out of Sitka on Channel 13 (Cable 6) serving Southeast Alaska. Additionally, KSCT-LP (NBC) Channel 5, KTOO (PBS) Channel 10,[73] and KJUD (ABC/CW) serve the region. There was a previous NBC affiliate in the Region, KSA-TV, available to cable systems, which is now defunct.

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]

Sitka is only accessible by boat or plane as it is on a pair of islands in the Pacific Ocean. Vehicles are usually brought to Sitka via the Alaska Marine Highway ferry system or the barge. However, a vehicle is not an absolute necessity in Sitka, as there are only 14 miles (23 kilometers) of road from one end of the island to another. Almost everything is within walking distance from the downtown area, which is where the majority of employers are situated. Public transportation is also available.

By air, Sitka Rocky Gutierrez Airport offers scheduled passenger jet service operated year-round by Alaska Airlines and seasonally by Delta Connection.

Delays in fall and winter due to Sitka's weather are frequent. The airport is located on Japonski Island, which is connected to Baranof Island by the O'Connell Bridge. The O'Connell Bridge, completed in 1972, was the first vehicular cable-stayed bridge in the United States. The Sitka Seaplane Base is a seaplane landing area situated in the Sitka Channel, adjacent to the airport.

Ferry travel back and forth to Juneau, Ketchikan and other towns in Southeast Alaska is provided through the Alaska Marine Highway System. The ferry terminal is located 7 miles (11 km) north of downtown and a ferry ticket costs about $89 per person each way to Juneau (as of February 2023). Vehicles, pets and bicycles can also be taken on the ferry for an additional charge.

Sitka's location on the outer coast of the Alaska Panhandle is removed from routes running through Chatham Strait. The tides of Peril Strait allow mainline vessels through only at slack tide.[74]

Alaska Marine Lines, a barge and freight company, has the ability to move cars to other communities connected to the mainland by road systems.

A three-way partnership of non-profits (Center for Community, Sitka Tribe of Alaska, and Southeast Senior Services) offers public bus transit, funded by the Federal Transit Administration and the Alaska Department of Transportation. All buses are fully accessible, with service from 6:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m., Monday through Friday.

In 2008, the League of American Bicyclists awarded Sitka the bronze level in bicycle friendliness, making Sitka the first bicycle-friendly community in Alaska. In 2013, the Walk Friendly Communities[75] program awarded Sitka with a bronze award, making Sitka the first Alaska community with a Walk Friendly Communities designation. Sitka is the only Alaska community to have both a Bicycle Friendly Community and a Walk Friendly Communities designation.

Healthcare

[edit]There is currently one hospital serving Sitka, Edgecumbe Hospital, which sits on Japonski Island across Sitka Harbor from the city. The facility is part of the Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium, or SEARHC, a non-profit tribal health consortium of 18 Native communities. The hospital serves as a regional referral center for people throughout Southeast Alaska, and also provides primary outpatient care. Numerous specialty clinics are offered at the hospital that are not available in the smaller communities such as neurology, orthopedic, dermatology, ophthalmology and denture clinics.

The former Sitka Community Hospital was purchased by the Southeast Alaska Regional Health Consortium (SEARHC) in April 2019, and now functions as a long-term care facility for patients of Edgecumbe hospital.[76]

Notable people

[edit]- Augusta Cohen Coontz (1867–1940), American First Lady of Guam

- Dale DeArmond (1914–2006), printmaker, book illustrator

- Annie Furuhjelm (1859–1937), Finnish journalist, legislator

- Sheldon Jackson (1834–1909), Presbyterian missionary in Alaska in the late 19th century

- Rebecca Himschoot, State representative

- Richard Nelson (1941–2019), cultural anthropologist, writer, activist

- Teri Rofkar (1956–2016), Tlingit weaver

- John Straley (born 1953), award-winning author

- Mary Bong (1880-1958), as Sing Deuh, Ah Fuh/Fur, or Qui Fah.[77] One of the first Chinese immigrants to live in Sitka; also known as "China Mary".[78]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Attractions

[edit]

Sitka's attractions include:

- Alaska Raptor Center

- Baranof Castle Hill

- Fortress of the Bear

- Sheet'ká Kwáan Naa Kahídi

- Russian Bishop's House

- Saint Lazaria National Wildlife Refuge

- St. Michael's Cathedral

- Sheldon Jackson Museum

- Sitka Fine Arts Camp

- Sitka Historical Museum

- Sitka Jazz Festival

- Sitka Lutheran Church

- Sitka National Historical Park

- Sitka Pioneer Home

- Sitka Summer Music Festival

- Swan Lake

- Tongass National Forest

The flora and fauna of Sitka and its surrounding area are popular. Day cruises and guided day trips (hiking) are large enterprises in Sitka. Floatplane "flightseeing" excursions are a way to view the area's sights from above.

Outdoor opportunities

[edit]Sitka's position between the Pacific Ocean and the most mountainous island in the Alexander Archipelago creates a variety of outdoor opportunities:

- Kayaking is a popular activity and small guided day excursions are offered locally.

- There are a number of maintained trails in the Sitka area, many of which are accessible from Sitka's road system.

- The dormant volcano Mount Edgecumbe is also a popular mountain to summit and features a seven-mile (11 km) trail up to the top. Guided day-trips are available, but the trip does not require much knowledge to undertake.

In popular culture

[edit]- Louis L'Amour penned Sitka, his fictional account of the events surrounding the United States' purchase of the Alaska Territory from the Russians for $7.2 million in 1867.

- Novelist James Michener lived at Sitka's Sheldon Jackson College while doing research for his epic work, Alaska.

- The 1952 film The World in His Arms has Russian Sitka as one of its settings.

- Sitka is the opening setting in Ivan Doig's 1982 historical fiction, The Sea Runners.

- Sitka is mentioned in Chapter 53 of James Clavell's 1993 historical fiction about Japan, Gai-Jin.

- Mystery author John Straley described Sitka as "...an island town where people feel crowded by the land and spread out on the sea."

- Part of the action in the novel César Cascabel by Jules Verne takes place in Sitka in May–June 1867, during the transfer of ownership to the United States.

- A fictionalized Sitka, inhabited by several million Jews who fled from Nazi-occupied Europe and their descendants, is the setting of the alternate history detective novel The Yiddish Policemen's Union, by Michael Chabon.

- Sitka is featured in the episode "Z-9000" of the Argentine TV series Los simuladores as the place where its antagonist, Lorenzo, is sent to keep him away from his wife whom he used to assault, under the pretext that a clone of him is trying to kill him.

- Sitka is a setting in the 2009 film The Proposal starring Sandra Bullock and Ryan Reynolds, although the scenes were filmed in Rockport, Massachusetts.

- Sitka is the name of one of the characters in the Disney film Brother Bear (2004).

- Sitka was featured in a 2012 episode of the Travel Channel's popular series Bizarre Foods,[81] starring Andrew Zimmern. In this episode Zimmern ate herring eggs, stink heads, and sea cucumbers.

- Sitka was named one of the Top 20 Small Towns to Visit in 2013[82] by Smithsonian magazine.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ From November 1867 to February 1873, the earliest American settlers in Sitka established and conducted affairs under a "provisional city government", as Alaskan communities were prohibited from legally incorporating until the U.S. Congress passed legislation allowing them to do so in 1900. Mayors of Sitka under this government included William Sumner Dodge and John Henry Kinkead. See Atwood, Evangeline; DeArmond, Robert N. (1977). Who's Who in Alaskan Politics. Portland, Oregon: Binford & Mort for the Alaska Historical Commission. p. 24.; Wheeler, Keith (1977). "Learning to cope with 'Seward's Icebox'". The Alaskans. Alexandria, Virginia: Time–Life Books. pp. 57–64. ISBN 0-8094-1506-2.

- ^ "City and Borough of Sitka Alaska - Government - City Assembly". www.cityofsitka.com. City of Sitka. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Everett-Heath, John (October 22, 2020). "Sitka". Concise Oxford Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-190563-6.

- ^ Joseph, Charlie; Brady, I.; Makinen, E.; David, R.; Davis, V.; Johnson, A.; Lord, N. (2001). "Sheet'kwaan Aani Aya". Sitka Tribe of Alaska. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Khlebnikov, K.T., 1973, Baranov, Chief Manager of the Russian Colonies in America, Kingston: The Limestone Press, ISBN 0919642500

- ^ Chevigny, Hector (1942). Lord of Alaska: Baranov and the Russian adventure. Cornell University: Viking Press. p. 320. OCLC 11877412. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Black, Lydia (2014). Russians in Alaska. Alaska: University of Alaska Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 9781889963044.

- ^ "The City & Borough of Sitka Alaska - About Sitka". www.cityofsitka.com. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Swaney, Deanna (2012). Alaska. Inc DK Publishing. London: DK. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-7566-9191-2. OCLC 794289670.

- ^ Sitka Lutheran Church Archived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NRHP nomination for St. Peter's Church". National Park Service. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ "Meeting of Frontiers: Alaska — The Alaska Purchase". Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "ANB celebrates 100th at ANB/ANS Grand Camp in Sitka" (Press release). Raven Radio. September 29, 2012. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2013.

- ^ Historic Sitka Harbor and Waterfront Self-Guided Tour:Points of Interest on Sitka's Historic Waterfront (Map). Sitka Maritime Heritage Society.

- ^ a b c Yarborough, Michael R. (April 10, 2009), Statement of Significance for the Fort Ray Historic District (Charcoal and Alice Islands) and the Mermaid Cove Mausoleum (PDF), Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2016, retrieved October 24, 2016

- ^ "Sitka Yesterday", Daily Sitka Sentinel, p. 2, September 2, 2022

- ^ "The Evolution of a Marine Industrial Park". www.sitka.net. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2016.

- ^ Klaney, Carol Kelty (1995). Gunalcheesh!. Haines, Alaska: Ptarmigan Press. pp. 77–78.

- ^ "Japonski Island". Visit Sitka. September 21, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e The Maritime Executive (May 29, 2025). "Sitka, a Small Town in Alaska, Resoundingly Rejects Cruise Ship Limits". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved June 3, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Sitka, Airport (1991–2020)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Sitka Airport, AK (1981-2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 6, 2023. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Hidden Falls Hatchery, AK". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ "Mount Edgecumbe volcanic field changes from 'dormant' to 'active' – what does that mean?". Alaska Volcano Observatory. May 9, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

The Mount Edgecumbe volcanic field (MEVF) is now classed as 'historically active' by the standards of the Alaska Volcano Observatory (AVO) because it is experiencing deformation related to the presence of magma intruding three miles below the surface.

- ^ "Mount Edgecumbe Information Statement, April 22, 2022". Alaska Volcano Observatory. April 22, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ "County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2024". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 3, 2025.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 23, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "American FactFinder: Results". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019.

- ^ "HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE (2020)". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ "HISPANIC OR LATINO, AND NOT HISPANIC OR LATINO BY RACE (2010)". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Alaska: 2000 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. pp. 30–31.

- ^ "TOTAL POPULATION". data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ a b Sitka, Alaska: 2010–2011 Community Profile (Report). Sitka Economic Development Association. p. 3.

- ^ "American Community Survey, 2006–2010 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ "Completing the Blue Lake expansion". International Water Power & Dam Construction magazine. January 6, 2015. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "Table of 2005 U.S. Port Rankings by Foreign Commerce Cargo Value: American Association of Port Authorities". cms-plus.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ Bunten, Alexis Celeste (2008). "Sharing Culture or Selling Out?: Developing the commodified persona in the heritage industry". American Ethnologist. 35 (3). American Anthropological Association: 382. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2008.00041.x. ISSN 0094-0496.

- ^ Ashley, McClelland (March 31, 2012). The Art of Innovation: The Effects of Trade and Tourism on Tlingit Dagger Production in the Nineteenth Century (Speech). Wooshteen Kanaxtulaneegí Haa At Wuskóowu / Sharing Our Knowledge, A conference of Tlingit Tribes and Clans: Haa eetí ḵáa yís / For Those Who Come After Us. Sitka, Alaska. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ^ "Halibut Point Marine Services: Cruise Terminal; Boat Yard". Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

Old Sitka Dock located at Halibut Point is the docking location for the majority of the large cruise ships that visit Sitka.

- ^ "Sitka's new dock is old Sitka Dock: private infrastructure for public good". thefreelibrary.com. November 1, 2013. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

McGraw [owner] designed his floating dock and named it the Old Sitka Dock in recognition of its proximity to the Old Sitka historical site.

- ^ a b "Sitka dock to get first regular visits in 2013". kcaw.org. December 4, 2012. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "Sitka cruises to bring passengers to shore". Alaska public media. April 26, 2016. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "RFP for transit services between Old Sitka Dock and Harrigan Centennial Hall" (PDF). cityofsitka.com. March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places, Sitka, Alaska". Archived from the original on August 16, 2004. Retrieved May 17, 2005.

- ^ "Alaska Day Festival, Sitka, Alaska". Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ "The City & Borough of Sitka Alaska - Election Results and Sample Ballots by Year". cityofsitka.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Alaska Taxable 2011: Municipal Taxation – Rates and Policies" (PDF). Division of Community and Regional Affairs, Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development. January 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ "City-Borough Sitka" (PDF). Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development (FTP). Retrieved July 16, 2008.[dead ftp link] (To view documents see Help:FTP)

- ^ "Home Rule Charter of the City and Borough of Sitka" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2007.

- ^ "Community/Borough Map: State of Alaska Department of Community and Economic Development" (PDF). ak-prepared.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2007.

- ^ "Certificate of Organization of the Unified Home Rule Municipality of the City an Borough of Sitka" (PDF). Alaska Department of Commerce, Community and Economic Development, Division of Community and Regional Affairs (DCRA). June 18, 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2010. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Hesse, Tom (December 20, 2015). "Group targets Sheldon Jackson campus for new college". Daily Sitka Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved December 22, 2017 – via Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

- ^ "2020 Census – School District Reference Map: Sitka City and Borough, AK" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022. - Text list

- ^ "Sitka, AK Private Schools". www.privateschoolreview.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ Woolsey, Robert (December 22, 2010). "Book sale brings end to Stratton Library story". KCAW. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ Guide to Alaska Newspapers on Microfilm (PDF). Juneau: Alaska State Library. 1998. pp. 324, 332. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 28, 2007. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ How to Find KTOO on Your Dial www.ktoo.org Archived July 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tides - Suemez Island, Port Santa Cruz, Sitka, Alaska". www.geotides.com. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Walk Friendly Communities". www.walkfriendly.org. January 5, 2017. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018.

- ^ "Assembly approves sale of Sitka Community Hospital". April 16, 2019.

- ^ CHINESE WOMEN IN THE NORTHWEST www.cinarc.org

- ^ Welcome to Sitka Borough, Alaska genealogytrails.com

- ^ "Alaska sister cities index". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Data Visualizations – Asia – Sister Partnerships – Asia – Asia Matters for America". Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- ^ "Diving for Dinner in Alaska". Travel Channel. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Spano, Susan (March 31, 2013). "The 20 Best Small Towns to Visit in 2013". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on August 21, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrews, C.L. (1944). The Story of Alaska. Caldwell, Ohio: The Caxton Printers, Ltd.

- Fedorova, Svetlana G. (1973). The Russian Population in Alaska and California: Late 18th century – 1867 (trans. & ed. by Richard A. Pierce and Alton S. Donnelly). Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press. ISBN 0-919642-53-5.

- Hope, Herb (2000). "The Kiks.ádi Survival March 1804". In Andrew Hope III; Thomas F. Thornton (eds.). Will the Time Ever Come? A Tlingit Source Book. Fairbanks, Alaska: Alaska Native Knowledge Network. pp. 48–79.

- Naske, Claus-M & Herman E. Slotnick (2003). Alaska: A History of the 49th State. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2099-1.

- Nordlander, David J. (1994). For God & Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America 1741–1867. Anchorage: Alaska Natural History Association. ISBN 0-930931-15-7.

- Vaillant, John (2006). The Golden Spruce: A True Story of Myth, Madness and Greed. Vintage Canada. ISBN 978-0-676-97646-5.

- Wharton, David (1991). They Don't Speak Russian in Sitka: A New Look at the History of Southern Alaska. Menlo Park, California: Markgraf Publications Group. ISBN 0-944109-08-X.

- Wilber, Glenn (1993). The Sitka Story: Crown Jewel of Baranof Island. "Land of Destiny"—Alaska Publications.

- Tlingit Geographical Place Names for the Sheet'ká Kwáan — Sitka Tribe of Alaska, an interactive map of Sitka Area native place names.

External links

[edit]- City & Borough of Sitka website

- Historic images

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . . 1914.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Sitka, Alaska

View on GrokipediaThe City and Borough of Sitka is a consolidated municipality in southeastern Alaska, United States, situated on the western shore of Baranof Island within the Alexander Archipelago and encompassing surrounding waters and islands.[1] With a land area of 2,874 square miles, it ranks as the largest incorporated city in the United States by land area, despite a sparse population density of about 3 people per square mile and a 2020 census count of 8,458 residents.[1] [2] Originally established by Russian fur traders as the settlement of New Archangel (Novoarkhangelsk) in 1804 following their victory over Tlingit forces in the Battle of Sitka, it functioned as the capital and primary administrative center of Russian America until the U.S. acquisition of Alaska in 1867.[3] Sitka's defining characteristics blend indigenous Tlingit heritage, dating back approximately 10,000 years, with Russian colonial influences evident in preserved architecture such as St. Michael's Cathedral and the Russian Bishop's House, alongside its status as a hub for commercial fishing—particularly salmon, halibut, and black cod—and ecotourism drawn to the Tongass National Forest, abundant wildlife, and coastal scenery.[1] [3] The local economy relies heavily on seafood harvesting and processing, which remains the largest private-sector employer, supplemented by visitor services including charter fishing and wildlife viewing, though challenges include fluctuating fish stocks and seasonal tourism patterns.[1] Its maritime climate features high precipitation, with 86 inches of annual rainfall, supporting lush temperate rainforest ecosystems while limiting agricultural development.[1] Notable sites include Sitka National Historical Park, preserving Tlingit totem poles and the site of the 1804 battle, underscoring the area's layered cultural and historical significance without major ongoing controversies beyond typical resource management debates in Alaska's fisheries.[3]

History

Pre-Contact Tlingit Settlement

Archaeological investigations in the Sitka area reveal human occupation dating back at least 8,000 to 8,600 years, with Tlingit oral histories and material evidence supporting continuous indigenous presence by specific clans for millennia prior to European contact.[4] The Sheet'ká Kwáan, the Tlingit group associated with the Sitka region, maintained fortified villages such as Sheet'ká on Baranof Island's western coast, occupied by clans including the Kiks.ádi (Raven moiety) and Kaagwaantaan (Eagle/Wolf moiety), alongside others like L'uknax.adi and Coho.[5][6] These clans structured settlements around plank houses and defensive palisades, reflecting adaptations to the coastal environment and interpersonal conflicts.[6] Tlingit subsistence in the region centered on seasonal salmon runs, which formed the economic backbone through fishing, drying, and storage practices essential for winter survival.[6] This was supplemented by hunting marine mammals such as seals and sea otters for meat, oil, and hides, with zooarchaeological analysis of precontact assemblages confirming their dietary role despite cultural taboos on routine consumption in some contexts.[7] Inter-group trade networks exchanged these resources, along with furs and eulachon oil, across Tlingit territories and with neighboring peoples, fostering economic interdependence without centralized markets.[6] Precontact population estimates for Tlingit in southeastern Alaska, including the Sitka area, range conservatively from 10,000 to 15,000, sustained by these localized, resource-intensive practices.[8] Social organization followed a matrilineal clan system divided into exogamous moieties—Raven and Eagle/Wolf—with status hierarchies validated through potlatch distributions of wealth and goods to affirm rank and resolve disputes.[9] Shamans held influence in mediating spiritual and healing matters, interpreting omens and conducting rituals tied to clan crests and natural forces.[10] Inter-clan warfare, often stemming from revenge feuds or resource competition, was common, prompting the construction of fortified villages and occasional raids that shaped territorial boundaries and alliances.[11]Russian Colonization and Conflicts

In 1799, Alexander Baranov, chief manager of the Russian-American Company, established a trading post known as Old Sitka (or Arkhangelsk) approximately seven miles north of the main Tlingit village on Baranof Island, following negotiations with local Kiks.ádi clan leaders for a fur hunting base amid the lucrative sea otter trade.[3] The post relied on relocated Aleut hunters, conscripted for their expertise in pursuing sea otters whose pelts fetched high prices in Asian markets, enabling the economic viability of Russian expansion despite logistical challenges from Siberia.[3][12] Tlingit resistance escalated, culminating in a coordinated attack on June 20, 1802 (Julian calendar), when warriors overran the underdefended fort, killing around 20 Russians and colonists while destroying structures and seizing thousands of pelts, forcing survivors to evacuate by sea.[13] This expulsion disrupted Russian operations but highlighted the strategic necessity of controlling prime otter hunting grounds, as the Tlingit controlled access to these resources essential for sustaining the colony's trade-based economy.[3] Baranov returned in September 1804 with reinforced forces totaling about 150 Russians and 400-500 Aleut auxiliaries aboard the ship Neva, launching an assault on the Tlingit stronghold at what became known as the Battle of Sitka.[14] Initial Tlingit defenses repelled the land advance, inflicting casualties including a chest wound to Baranov, but Neva's cannon bombardment from October 4-6 shattered the wooden fort, prompting Tlingit retreat northward and abandonment of the site without decisive counterattack.[14] Russian losses numbered around 12 killed and many wounded, securing the area for a permanent fortified settlement and underscoring naval artillery's role in overcoming fortified indigenous positions to protect fur trade assets.[3] This victory facilitated sustained resource extraction, with Aleut labor parties continuing otter hunts under Russian oversight to offset high operational costs and imperial ambitions.[3]Russian America Capital Period

In 1808, following the reconstruction after the 1804 Tlingit attack, New Archangel (Novo-Arkhangelsk) was designated the capital of Russian America, serving as the administrative center for the Russian-American Company until 1867.[15] This relocation centralized governance, with the company managing colonial operations from Sitka, including oversight of fur trade expeditions and settlement expansion across Alaska.[3] By 1867, the colonial population in New Archangel comprised approximately 800 Russians, Creoles (mixed Russian-native descendants), and European settlers, alongside thousands of coerced Tlingit and Aleut laborers who supported the economy but were not integrated as full residents.[16] The settlement featured fortified infrastructure to defend against Tlingit resistance, including palisade walls, blockhouses, and the Baranov-built stockade on Castle Hill, which housed administrative buildings and warehouses.[17] St. Michael's Cathedral, constructed between 1844 and 1848 under Bishop Innokenty Veniaminov's design, stood as the largest structure in Russian America, symbolizing Orthodox influence and serving as a center for missionary activities aimed at native conversion.[18] The Russian Orthodox Church played a key role in cultural assimilation, with clergy like Veniaminov adapting Christian practices to indigenous customs, providing education to Creoles, and administering smallpox vaccinations during epidemics, such as the 1836 outbreak that threatened Tlingit populations despite saving some lives.[19] However, assimilation efforts coexisted with systemic exploitation, as natives faced forced labor contracts and subjugation under company rule.[3] Economically, New Archangel peaked as a fur trade hub, hosting auctions of sea otter and other pelts that generated significant revenue for the Russian-American Company, with operations peaking in the early 19th century before overhunting depleted stocks.[20] Shipbuilding emerged as a vital industry, with at least 24 vessels constructed locally between 1804 and 1867, utilizing abundant timber to support trade fleets and reduce reliance on imported ships.[21] These achievements masked harsh realities, including native servitude where Tlingit and Aleuts were compelled into hunting and labor under threat of violence, contributing to demographic collapse from introduced diseases like smallpox, which repeatedly decimated indigenous groups lacking immunity.[3] Epidemics, including major outbreaks in the 1830s, reduced Tlingit numbers significantly, exacerbating labor shortages and dependency on coerced workforces.[22]American Acquisition and Early Territorial Years

The formal transfer of Alaska from Russia to the United States occurred on October 18, 1867, at Castle Hill in Sitka, where U.S. Army troops raised the American flag after lowering the Russian ensign in a ceremony attended by approximately 250 American soldiers and Russian officials.[23][24] This event marked the legal acquisition of the territory for $7.2 million, with Sitka serving as the initial U.S. administrative center, though the Tlingit people, who had never ceded control of the surrounding lands, viewed the Russian departure as an opportunity to reassert dominance over the area beyond the hill itself.[25][26] October 18 became known as Alaska Day, signifying the official end of Russian claims despite ongoing native assertions of territorial rights.[27] Following the handover, U.S. military governance under the Army lasted until 1877, during which infrastructure inherited from Russian operations, including forts and administrative buildings, deteriorated due to neglect and insufficient funding, while tensions with Tlingit clans escalated over land access and resource disputes.[25][28] The Army's withdrawal in 1877 left Sitka without formal civil authority, fostering a period of lawlessness characterized by unregulated saloons, transient populations, and sporadic violence, including incidents of native incursions into abandoned areas and retaliatory U.S. military actions such as the 1869 bombardment of Kake village after killings of American citizens.[25][29] No significant native raids directly targeted Sitka proper in this era, but unresolved grievances contributed to broader instability until naval and revenue cutter patrols provided intermittent order.[26] Presbyterian missionary efforts began in earnest in 1878 with the arrival of Sheldon Jackson, who established the Sitka Industrial Training School to promote assimilation through education and vocational training aimed at integrating Tlingit youth into American societal norms.[30] Jackson's initiatives, funded largely through church networks rather than federal support, focused on displacing traditional practices with Protestant values and manual labor skills, though economic activity in Sitka remained stagnant, reliant on subsistence and limited trade amid abandoned Russian enterprises.[31] This dormancy persisted until the 1880s, when gold discoveries elsewhere in the region, such as Juneau in 1880, began diverting population and investment away from Sitka, underscoring the territory's initial administrative and developmental failures.[32][33]Native Advocacy and Organizational Developments

The Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB) was founded on November 5, 1912, in Sitka by twelve Tlingit and Tsimshian men and one woman, who sought to address discrimination against Alaska Natives by advocating for U.S. citizenship, land rights, and economic equality.[34][35] The organization drew inspiration from non-Native fraternal groups like the Arctic Brotherhood and focused on promoting Native solidarity while challenging legal barriers that prevented Natives from owning land, voting, or accessing equal education.[34] In 1915, the Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS) formed in Wrangell as a women's auxiliary to the ANB, collaborating on civil rights efforts including pushes for Native suffrage and integrated schools during territorial legislative sessions that year.[36] These groups lobbied federal authorities, contributing to the Indian Citizenship Act of June 2, 1924, which extended U.S. citizenship to all Native Americans born in the United States, including Alaska Natives, though full voting rights in Alaska faced ongoing state-level obstacles until later reforms.[37][38] Post-World War II, the ANB and ANS intensified land claims advocacy amid growing pressures from resource development, helping catalyze the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) signed into law on December 18, 1971, which extinguished aboriginal title in exchange for $962.5 million in cash and nearly 44 million acres of land distributed to newly formed Native corporations.[39] In Sitka, this resulted in the creation of Shee Atiká Incorporated as the urban Native corporation under ANCSA, alongside regional entity Sealaska Corporation for Southeast Alaska, enabling Natives to hold shares in for-profit businesses focused on timber, fisheries, and other resources.[40][41] While these developments provided economic mechanisms and legal resolution to claims unresolved since the 1867 Alaska Purchase, critics have argued that ANCSA's structure of racially exclusive corporations reinforced separatist tendencies by prioritizing group-based entitlements over individual integration into broader markets, potentially hindering assimilation and perpetuating reliance on government subsidies.[42] Empirical outcomes include persistent high unemployment and poverty in many Native communities, with some analysts attributing this to a legacy of welfare dependency fostered by advocacy emphasizing collective claims rather than self-reliant economic participation, as evidenced by ongoing federal funding dependencies documented in regional studies.[43][44]World War II Military Role

The establishment of military bases in Sitka during World War II transformed the town into a strategic hub for defending Alaska's southeastern approaches against Japanese forces, particularly following the 1942 Aleutian Islands campaign. In response to escalating threats after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Army authorized Fort Ray in early 1941 as Alaska's inaugural World War II military installation, positioned for harbor defense across Alice and Charcoal Islands to safeguard naval assets in Sitka Sound.[45] Designed to house 2,988 enlisted men and 194 officers in 136 structures, including semi-permanent barracks and defensive batteries, Fort Ray's rapid construction emphasized coastal artillery and observation posts integrated with searchlight stations to monitor potential incursions.[46] Complementing this, the U.S. Navy expanded its presence on Japonski Island, commissioning the Sitka Naval Operating Base in March 1942 as Alaska's first dedicated air station, from which patrol aircraft conducted surveillance over the Gulf of Alaska and supported Aleutian reinforcements amid heightened alerts after Japanese landings at Attu and Kiska.[47][48] These fortifications directly bolstered North American continental defense by enabling early warning and interdiction capabilities, with Army coastal defenses incorporating base-end stations and gun emplacements to protect the naval airfield's vulnerability to air and sea attack. Construction projects, including dredging, causeways, and auxiliary facilities like Fort Rousseau, drew civilian contractors and local laborers—encompassing Tlingit residents and non-Native workers—for fortification and maintenance tasks, providing a surge in wartime employment tied to federal funding and material shipments.[47][49] The bases' operational scale, peaking with integrated Army-Navy coordination for patrols and anti-submarine warfare, underscored Sitka's role in deterring further Japanese advances beyond the Aleutians, though no direct engagements occurred locally.[50] By late 1944, as Pacific threats receded, both Fort Ray and the Sitka Naval Operating Base deactivated, with Army garrisons transferred out by August and naval operations ceasing amid demobilization, marking the end of Sitka's acute military phase and reverting infrastructure to civilian use.[45][51] This temporary expansion, driven by immediate defensive imperatives rather than long-term planning, yielded short-lived economic activity from base-related labor but left remnants like observation posts as artifacts of Alaska's broader wartime mobilization.[47]Post-Statehood Growth and Transitions

Alaska's admission to statehood on January 3, 1959, facilitated expanded local management of marine resources, spurring growth in Sitka's fisheries sector as the state prioritized sustainable practices over prior federal trap systems.[52] The Magnuson-Stevens Act of 1976 further extended U.S. jurisdiction to 200 nautical miles, enabling Alaskan fisheries—including those around Sitka—to capture greater shares of salmon and shellfish harvests, with production volumes rising amid improved regulatory frameworks.[12] Population in the Sitka area increased from approximately 2,500 residents in 1960 to over 6,100 by 1970, reflecting influxes tied to resource-based employment opportunities.[53] In the 1970s, the formation of the unified City and Borough of Sitka consolidated municipal and regional governance, streamlining administration across the expansive Baranof Island territory and supporting infrastructure development for growing industries. Logging operations in the Tongass National Forest peaked during this era, with statewide timber harvests reaching 570 million board feet in 1980, much of it from Southeast Alaska including Sitka-area mills, before market saturation and competition from Pacific Northwest sources initiated declines in the mid-1980s. Seafood processing similarly boomed through the early 1980s via longline innovations but faced volatility from overharvest signals and global price fluctuations, prompting diversification.[52] By the late 1980s, tourism emerged as a stabilizing force, with visitor numbers in Sitka climbing from resource-dependent lows as cruise operations expanded, reaching 167,000 arrivals by 1992 and nearing 250,000 by 1996, thereby buffering against fishery and timber contractions.[54] This shift underscored a transition toward service-oriented self-reliance, though federal land management in the Tongass continued influencing resource access and local economic dependencies.[55] Population stabilized around 8,000-8,500 through the 1990s, with employment metrics reflecting moderated unemployment amid these adaptations, averaging below state highs during downturns.[56]Geography and Environment

Location and Physical Features

The City and Borough of Sitka occupies portions of Baranof Island and the southern part of Chichagof Island in the Alexander Archipelago of southeastern Alaska, facing the Pacific Ocean along the outer coast.[1][57] This island setting places Sitka amid a network of islands separated by narrow channels and fjords characteristic of the archipelago's topography.[1] The consolidated borough spans a land area of 2,870 square miles, yielding a population density of approximately 3 residents per square mile based on recent census data.[58] Sitka is situated about 95 miles southwest of Juneau, the Alaska state capital, and roughly 150 miles west of Petersburg, with access limited to air and sea travel due to the surrounding rugged terrain.[59] The physical landscape features steep, glacially carved mountains rising sharply from the coast, including prominent peaks such as Mount Verstovia, located just east of the city center.[60] Deep fjords and coastal bays define the shoreline, contributing to the area's intricate waterway system and isolating the community from mainland Alaska.[1]Climate Characteristics

Sitka possesses a marine west coast climate, classified as Köppen Cfb, marked by mild year-round temperatures moderated by the adjacent Pacific Ocean and Gulf of Alaska, alongside persistently high moisture levels.[61] Annual average temperatures hover around 45°F, with extremes seldom exceeding 80°F or dropping below 0°F, reflecting the absence of continental polar influences.[62] Precipitation averages 86 inches annually, falling as rain on approximately 230 days and snow on about 20 days, yielding 39 inches of seasonal snowfall primarily from November to March.[1] Summer months (June through September) feature cool conditions, with average daily highs ranging from 58°F to 62°F and lows near 50°F, accompanied by partial cloud cover and reduced precipitation relative to winter.[63] Winters (December through February) remain mild for Alaska's latitude, averaging highs of 42°F to 45°F and lows of 32°F to 35°F, though overcast skies and persistent drizzle prevail, with no monthly mean below freezing.[63] October stands as the wettest month, typically delivering over 10 inches of rain.[63] Fog occurs frequently, especially during summer due to coastal upwelling and temperature inversions, often reducing visibility and complicating maritime and air navigation in the surrounding channels.[64] Winds average 8-10 mph year-round, with prevailing southerlies strengthening to gusts over 20 mph in winter storms, contributing to turbulent seas but rarely hurricane-force events.[63] These patterns derive from long-term observations at the NOAA-operated Sitka Airport station, with reliable records extending from the 1950s onward, standardized in 30-year normals for the 1991-2020 period.[65]Geological Formation and Hazards