Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Climate of India

View on Wikipedia

The climate of India includes a wide range of weather conditions, influenced by its vast geographic scale and varied topography. Based on the Köppen system, India encompasses a diverse array of climatic subtypes. These range from arid and semi-arid regions in the west to highland, sub-arctic, tundra, and ice cap climates in the northern Himalayan regions, varying with elevation.

The Indo-Gangetic Plains in the north experience a humid subtropical climate which become more temperate at higher altitudes, like the Sivalik Hills, or continental in some areas like Gulmarg. In contrast, much of the south and the east exhibit tropical climate conditions, which support lush rainforests in parts of these territories. Many regions have starkly different microclimates, making it one of the most climatically diverse countries in the world. The country's meteorological department follows four seasons with some local adjustments: winter (December to February), summer (March to May), monsoon or south-west monsoon (June to September) and post-monsoon or north-east monsoon (October to November). Some parts of the country with subtropical, temperate or continental climates also experience spring and autumn.

India's geography and geology are climatically pivotal: the Thar Desert in the northwest and the Himalayas in the north work in tandem to create a culturally and economically important monsoonal regime. As Earth's highest and most massive mountain range, the Himalayas bar the influx of frigid katabatic winds from the icy Tibetan Plateau and northerly Central Asia. Most of North India is thus kept warm or is only mildly chilly or cold during winter; the same thermal dam keeps most regions in India hot in summer. The climate in South India is generally warmer, and more humid due to its coastlines. However some hill stations in South India such as Ooty are well known for their cold climate.

Though the Tropic of Cancer—the boundary that is between the tropics and subtropics—passes through the middle of India, the bulk of the country can be regarded as climatically tropical. As in much of the tropics, monsoonal and other weather patterns in India can be strongly variable: epochal droughts, heat waves, floods, cyclones, and other natural disasters are sporadic, but have displaced or ended millions of human lives. Such climatic events are likely to change in frequency and severity as a consequence of human-induced climate change. Ongoing and future vegetative changes, sea level rise and inundation of India's low-lying coastal areas are also attributed to global warming.[2]

Paleoclimate

[edit]

History

[edit]During the Triassic period of 251–199.6 Ma, the Indian subcontinent was the part of a vast supercontinent known as Pangaea. Despite its position within a high-latitude belt at 55–75° S—latitudes now occupied by parts of the Antarctic Peninsula, as opposed to India's current position between 8 and 37° N—India likely experienced a humid temperate climate with warm and frost-free weather, though with well-defined seasons.[3] India later merged into the southern supercontinent Gondwana, a process beginning some 550–500 Ma. During the Late Paleozoic, Gondwana extended from a point at or near the South Pole to near the equator, where the Indian craton (stable continental crust) was positioned, resulting in a mild climate favorable to hosting high-biomass ecosystems. This is underscored by India's vast coal reserves—much of it from the late Paleozoic sedimentary sequence—the fourth-largest reserves in the world.[4] During the Mesozoic, the world, including India, was considerably warmer than today. With the coming of the Carboniferous, global cooling stoked extensive glaciation, which spread northwards from South Africa towards India; this cool period lasted well into the Permian.[5]

Tectonic movement by the Indian Plate caused it to pass over a geologic hotspot—the Réunion hotspot—now occupied by the volcanic island of Réunion. This resulted in a massive flood basalt event that laid down the Deccan Traps some 60–68 Ma,[6][7] at the end of the Cretaceous period. This may have contributed to the global Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which caused India to experience significantly reduced insolation. Elevated atmospheric levels of sulphur gases formed aerosols such as sulphur dioxide and sulphuric acid, similar to those found in the atmosphere of Venus; these precipitated as acid rain. Elevated carbon dioxide emissions also contributed to the greenhouse effect, causing warmer weather that lasted long after the atmospheric shroud of dust and aerosols had cleared. Further climatic changes 20 million years ago, long after India had crashed into the Laurasian landmass, were severe enough to cause the extinction of many endemic Indian forms.[8] The formation of the Himalayas resulted in blockage of frigid Central Asian air, preventing it from reaching India; this made its climate significantly warmer and more tropical in character than it would otherwise have been.[9]

More recently, in the Holocene epoch (4,800–6,300 years ago), parts of what is now the Thar Desert were wet enough to support perennial lakes; researchers have proposed that this was due to much higher winter precipitation, which coincided with stronger monsoons.[10] Kashmir's erstwhile subtropical climate dramatically cooled 2.6–3.7 Ma and experienced prolonged cold spells starting 600,000 years ago.[11]

Regions

[edit]

India has many different climates, from tropical in the south to temperate and alpine in the Himalayan north, where higher areas get snowfall in winter. The nation's climate is strongly influenced by the Himalayas and the Thar Desert.[13] The Himalayas, along with the Hindu Kush mountains in Pakistan, prevent cold Central Asian katabatic winds from blowing in, keeping the bulk of the Indian subcontinent warmer than most locations at similar latitudes.[14] Simultaneously, the Thar Desert plays a role in attracting moisture-laden south-west monsoon winds between June and October, which provide the majority of India's rainfall.[13][15] Four major climatic groupings predominate, into which fall the seven climatic zones, that as designated by experts, are defined on the basis of such traits as temperature and precipitation.[16] Groupings are assigned codes (see chart) according to the Köppen climate classification system.

Tropical

[edit]A tropical rainy climate governs regions experiencing persistent warm or high temperatures, which normally do not fall below 18 degrees Celsius (64 °F). India predominantly hosts two climatic subtypes that fall into this group: tropical monsoon climate and tropical savanna climate.

The most humid is the tropical wet climate—also known as the tropical monsoon climate—that covers a strip of southwestern lowlands abutting the Malabar Coast, the Western Ghats, and southern Assam. India's two island territories, Lakshadweep and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, are also subject to this climate. Characterised by moderate to high year-round temperatures, even in the foothills, its rainfall is seasonal but heavy—typically above 2,000 millimetres (79 inches) per year.[17] Most rainfall occurs between May and November; this moisture is enough to sustain lush forests, swampy areas and other vegetation for the rest of the mainly dry year. December to March are the driest months, when days with precipitation are rare. The heavy monsoon rains are responsible for the exceptional biodiversity of tropical wet forests in parts of these regions.

In India a tropical savanna climate is more common. Noticeably drier than areas with a tropical monsoon type of climate, it prevails over most of inland peninsular India except for a semi arid rain shadow east of the Western Ghats. Winter and early summer are long and dry periods with temperatures averaging above 18 °C (64 °F). Summer is exceedingly hot; temperatures in low-lying areas may exceed 50 °C (122 °F) during May, leading to heat waves that can each kill hundreds of Indians.[18] The rainy season lasts from June to September; annual rainfall averages between 750 and 1,500 mm (30 and 59 in) across the region. Once the dry northeast monsoon begins in September, most significant precipitation in India falls on Tamil Nadu and Puducherry leaving other states comparatively dry.

The Ganges Delta lies mostly in the tropical wet climate zone: it receives between 1,500 and 2,000 mm (59 and 79 in) of rainfall each year in the western part, and 2,000 and 3,000 mm (79 and 118 in) in the eastern part. The coolest month of the year, on average, is January; April and May are the warmest months. Average temperatures in January range from 14 to 25 °C (57 to 77 °F), and average temperatures in April range from 25 to 35 °C (77 to 95 °F). July is on average the coldest and wettest month: over 330 mm (13 in) of rain falls on the delta.[19]

Additionally, Nicobar Islands rain forests experience a Tropical rainforest climate.[20]

Arid and semi-arid regions

[edit]Arid and semi-arid climate dominates regions where the rate of moisture loss through evapotranspiration exceeds that from precipitation;

A semi-arid steppe climate (hot semi-arid climate) predominates over a long stretch of land south of Tropic of Cancer and east of the Western Ghats and the Cardamom Hills. The region, which includes Karnataka, inland Tamil Nadu, western Andhra Pradesh, and central Maharashtra, gets between 400 and 750 millimetres (15.7 and 29.5 in) annually. It is drought-prone, as it tends to have less reliable rainfall due to sporadic lateness or failure of the southwest monsoon.[21] Karnataka is divided into three zones—coastal, north interior and south interior. Of these, the coastal zone receives the most precipitation, averaging 3,638 mm (143.2 in) per annum, far in excess of the state average of 1,139 mm (44.8 in). In contrast to norm, Agumbe in the Shivamogga district receives the second highest annual rainfall in India. North of the Krishna River, the summer monsoon is responsible for most rainfall; to the south, significant post-monsoon rainfall also occurs in October and November. In December, the coldest month, temperatures still average around 20–24 °C (68–75 °F). The months between March and May are hot and dry; mean monthly temperatures hover around 32 °C (90 °F), with 320 millimetres (12.6 in) precipitation. Hence, without artificial irrigation, this region is not suitable for permanent agriculture.[citation needed]

Most of western Rajasthan experiences an arid climatic regime (hot desert climate). Cloudbursts are responsible for virtually all of the region's annual precipitation, which totals less than 300 millimetres (11.8 in). Such bursts happen when monsoon winds sweep into the region during July, August, and September. Such rainfall is highly erratic; regions experiencing rainfall one year may not see precipitation for the next couple of years or so. Atmospheric moisture is largely prevented from precipitating due to continuous downdrafts and other factors.[22] The summer months of May and June are exceptionally hot; mean monthly temperatures in the region hover around 35 °C (95 °F), with daily maxima occasionally topping 50 °C (122 °F). During winters, temperatures in some areas can drop below freezing due to waves of cold air from Central Asia. There is a large diurnal range of about 14 °C (25 °F) during summer; this widens by several degrees during winter. There is a small desert area in the south near Adoni in Andhra Pradesh, the only desert in South India, experiencing maximum temperatures of 47 °C (117 °F) in summers and 18 °C (64 °F) in winters.[citation needed]

To the west, in Gujarat, diverse climate conditions prevail. The winters are mild, pleasant, and dry with average daytime temperatures around 29 °C (84 °F) and nights around 12 °C (54 °F) with virtually full sun and clear nights. Summers are hot and dry with daytime temperatures around 41 °C (106 °F) and nights no lower than 29 °C (84 °F). In the weeks before the monsoon temperatures are similar to the above, but high humidity makes the air more uncomfortable. Relief comes with the monsoon. Temperatures are around 35 °C (95 °F) but humidity is very high; nights are around 27 °C (81 °F). Most of the rainfall occurs in this season, and the rain can cause severe floods. The sun is often occluded during the monsoon season.[citation needed]

East of the Thar Desert, the Punjab–Haryana–Kathiawar region experiences a tropical and sub-tropical steppe climate. Haryana's climate resembles other states of the northern plains: extreme summer heat of up to 50 °C (122 °F) and winter cold as low as 1 °C (34 °F). May and June are hottest; December and January are coldest. Rainfall is varied, with the Shivalik Hills region being the wettest and the Bagar region being the driest. About 80 percent of the rainfall occurs in the monsoon season of July–September, which can cause flooding. The Punjabi climate is also governed by extremes of hot and cold. Areas near the Himalayan foothills receive heavy rainfall whereas those eloigned from them are hot and dry. Punjab's three-season climate sees summer months that span from mid-April to the end of June. Temperatures in Punjab typically range from −2 to 40 °C (28–104 °F), but can reach 47 °C (117 °F) in summer and fall to −4 °C (25 °F) in winter (while most of the nation does not experience temperatures below 10 °C (50 °F) even in winter). The zone, a transitional climatic region separating tropical desert from humid sub-tropical savanna and forests, experiences temperatures that are less extreme than those of the desert. Although the average annual rainfall is 300–650 millimetres (11.8–25.6 in), it is very unreliable; like in much of the rest of India, the southwest monsoon accounts for most precipitation. Summer daily maxima are around 40 °C (104 °F). All this results in a natural vegetation typically comprising short, coarse grasses.[citation needed]

Humid subtropical

[edit]Most of Northeast India and much of North India are subject to a humid subtropical climate and a subtropical highland climate. Though they experience warm to hot summers, temperatures during the coldest months generally fall as low as 0 °C (32 °F). Due to ample monsoon rains, India has two subtropical climate subtypes under the Köppen system: Cwa and Cwb.[23] In most of this region, there is very little precipitation during the winter, owing to powerful anticyclonic and katabatic (downward-flowing) winds from Central Asia.

Humid subtropical regions are subject to pronounced dry winters. Winter rainfall—and occasionally snowfall—is associated with large storm systems such as "Nor'westers" and "Western disturbances"; the latter are steered by westerlies towards the Himalayas.[24] Most summer rainfall occurs during powerful thunderstorms associated with the southwest summer monsoon; occasional tropical cyclones also contribute. Annual rainfall ranges from less than 1,000 millimetres (39 in) in the west to over 2,500 millimetres (98 in) in parts of the northeast. As most of this region is far from the ocean, the wide temperature swings more characteristic of a continental climate predominate; the swings are wider than in those in tropical wet regions, ranging from 24 °C (75 °F) in north-central India to 27 °C (81 °F) in the east.[citation needed]

Mountain

[edit]

India's northernmost areas are subject to a montane, or alpine, climate. In the Himalayas, the rate at which an air mass's temperature falls per kilometre (3,281 ft) of altitude gained (the dry adiabatic lapse rate) is 9.8 °C/km.[25] In terms of environmental lapse rate, ambient temperatures fall by 6.5 °C (11.7 °F) for every 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) rise in altitude. Thus, climates ranging from nearly tropical in the foothills to tundra above the snow line can coexist within several hundred metres of each other. Sharp temperature contrasts between sunny and shady slopes, high diurnal temperature variability, temperature inversions, and altitude-dependent variability in rainfall are also common.

The northern side of the western Himalayas, also known as the trans-Himalayan belt, has a cold desert climate. It is a region of barren, arid, frigid and wind-blown wastelands. Areas south of the Himalayas are largely protected from cold winter winds coming in from the Asian interior. The leeward side (northern face) of the mountains receives less rain.

The southern slopes of the western Himalayas, well-exposed to the monsoon, get heavy rainfall. Areas situated at elevations of 1,070–2,290 metres (3,510–7,510 ft) receive the heaviest rainfall, which decreases rapidly at elevations above 2,290 metres (7,513 ft). Most precipitation occurs as snowfall during the late winter and spring months. The Himalayas experience their heaviest snowfall between December and February and at elevations above 1,500 metres (4,921 ft). Snowfall increases with elevation by up to several dozen millimetres per 100 metre (~2 in; 330 ft) increase. Elevations above 6,000 metres (19,685 ft) never experience rain; all precipitation falls as snow.[26]

Seasons

[edit]The India Meteorological Department (IMD) designates four climatological seasons:[27]

- Winter, occurring from December to February. The year's coldest months are December and January, when temperatures average around 10–15 °C (50–59 °F) in the northwest; temperatures rise as one proceeds towards the equator, peaking around 20–25 °C (68–77 °F) in mainland India's southeast.

- Summer or Pre-monsoon season, lasting from March to June. In western and southern regions, the hottest month is April and the beginning of May and for northern regions of India, May is the hottest Month. In May, Temperatures average around 32–40 °C (90–104 °F) in most of the interior.

- Monsoon or South-west monsoon season, lasting from June to September. The season is dominated by the humid southwest summer monsoon, which slowly sweeps across the country beginning in late May or early June. Monsoon rains begin to recede from North India at the beginning of October. South India typically receives more rainfall.

- Post-monsoon or North-east monsoon season, lasting from October to November. In the north of India, October and November are usually cloudless. Tamil Nadu receives most of its annual precipitation in the northeast monsoon season.

The Himalayan and Upper Gangetic Plains, being more temperate, experience an additional season, spring, which coincides with the first weeks of summer in southern India.[28] Traditionally, North Indians note six seasons or Ritu, each about two months long. These are the spring season (Sanskrit: vasanta), summer (grīṣma), monsoon season (varṣā), autumn (śarada), winter (hemanta), and prevernal season[29] (śiśira). These are based on the astronomical division of the twelve months into six parts. The ancient Hindu calendar also reflects these seasons in its arrangement of months.

Tamil seasons

[edit]- In Tamil the seasons are called paruvam which means part or a season and they are summer kōɖai(hot summer) paruvam or kālam, winter kuɭir(chill) Kālam or paruvam and rainy which is maɻai Kālam or paruvam and Autumn which is ilaiyudhir( means leaf falling) Kālam or paruvam and spring is Ila Venir Kālam( leaf growing) or paruvam and rainy or monsoon is Kār(black clouds) paruvam or Kālam.

The word Kālam or paruvam is the word for season in tamil standard. These words are generally derived from proto dravidian and is continuosly used till today to refer seasons which is independent to that of sanskrit. It's not present in other south indian languages but some village dialects of malayalam.

Winter

[edit]

Once the monsoons subside, average temperatures gradually fall across India. As the Sun's vertical rays move south of the equator, most of the country experiences moderately cool weather. December and January are the coldest months, with the lowest temperatures occurring in the Indian Himalayas. Temperatures are higher in the east and south.

In northwestern India region, virtually cloudless conditions prevail in October and November, resulting in wide diurnal temperature swings; as in much of the Deccan Plateau, they register at 16–20 °C (61–68 °F). However, from January to February, "western disturbances" bring heavy bursts of rain and snow. These extra-tropical low-pressure systems originate in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.[30] They are carried towards India by the subtropical westerlies, which are the prevailing winds blowing at North India's range of latitude.[24] Once their passage is hindered by the Himalayas, they are unable to proceed further, and they release significant precipitation over the southern Himalayas.

There is a huge variation in the climatic conditions of Himachal Pradesh due to variation in altitude (450–6500 metres). The climate varies from hot and subtropical humid (450–900 metres) in the southern low tracts, warm and temperate (900–1800 metres), cool and temperate (1900–2400 metres) and cold glacial and alpine (2400–4800 metres) in the northern and eastern elevated mountain ranges. By October, nights and mornings are very cold. Snowfall at elevations of nearly 3000 m is about 3 m and lasts from December start to March end. Elevations above 4500 m support perpetual snow. The spring season starts from mid February to mid April. The weather is pleasant and comfortable in the season. The rainy season starts at the end of the month of June. The landscape lushes green and fresh. During the season streams and natural springs are replenished. The heavy rains in July and August cause a lot of damage resulting in erosion, floods and landslides. Out of all the state districts, Dharamshala receives the highest rainfall, nearly about 3,400 mm (134 in). Spiti is the driest area of the state, where annual rainfall is below 50 mm.[31] The five Himalayan states (Ladakh, Jammu and Kashmir in the extreme north, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh in far east) and Northern West Bengal experience heavy snowfall, Manipur and Nagaland are not located in the Himalayas but experience occasional snowfall; in Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir, blizzards occur regularly, disrupting travel and other activities.

The rest of North India, including the Indo-Gangetic Plain and Madhya Pradesh almost never receives snow. Temperatures in the plains occasionally fall below freezing, though never for more than one or two days. Winter highs in Delhi range from 16 to 21 °C (61 to 70 °F). Nighttime temperatures average 2–8 °C (36–46 °F). In the plains of Punjab, lows can fall below freezing, dropping to around −3 °C (27 °F) in Amritsar.[32] Frost sometimes occurs, but the hallmark of the season is the notorious fog, which frequently disrupts daily life; fog grows thick enough to hinder visibility and disrupt air travel 15–20 days annually. In Bihar in middle of the Ganges plain, hot weather sets in and the summer lasts until the middle of June. The highest temperature is often registered in late May or early June which is the hottest time. Like the rest of the north, Bihar also experiences dust-storms, thunderstorms and dust raising winds during the hot season. Dust storms having a velocity of 48–64 km/h (30–40 mph) are most frequent in May and with second maximum in April and June. The hot winds (loo) of Bihar plains blow during April and May with an average velocity of 8–16 km/h (5–10 mph). These hot winds greatly affect human comfort during this season. Rain follows.[33] The rainy season begins in June. The rainiest months are July and August. The rains are the gifts of the southwest monsoon. There are in Bihar three distinct areas where rainfall exceeds 1,800 mm (71 in). Two of them are in the northern and northwestern portions of the state; the third lies in the area around Netarhat. The southwest monsoon normally withdraws from Bihar in the first week of October.[34] Eastern India's climate is milder but gets colder as one moves north west, experiencing moderately warm days to cool days and cool nights to cold nights. Highs ranges from 18 °C to 23 °C (64 °F to 73 °F) in Patna; to 22 °C to 27 °C (72 °F to 80 °F) in Kolkata (Calcutta); lows averages from 7 °C to 10 °C (45 °F to 50 °F) in Patna; to 12 °C to 15 °C (54 °F to 59 °F) in Kolkata. In Madhya Pradesh which is towards the south-western side of the Gangetic Plain similar conditions prevail albeit with much less humidity levels. Capital Bhopal averages low of 9 °C (48 °F) and high of 24 °C (75 °F).

Frigid winds from the Himalayas can depress temperatures near the Brahmaputra River.[35] The Himalayas have a profound effect on the climate of the Indian subcontinent and the Tibetan plateau by preventing frigid and dry Arctic winds from blowing south into the subcontinent, which keeps South Asia much warmer than corresponding temperate regions in the other continents. It also forms a barrier for the monsoon winds, keeping them from travelling northwards, and causing heavy rainfall in the Terai region instead. The Himalayas are indeed believed to play an important role in the formation of Central Asian deserts such as the Taklamakan and Gobi. The mountain ranges prevent western winter disturbances in Iran from travelling further east, resulting in much snow in Kashmir and rainfall for parts of Punjab and northern India. Despite the Himalayas being a barrier to the cold northerly winter winds, the Brahmaputra valley receives part of the frigid winds, thus lowering the temperature in Northeast India and Bangladesh. The Himalayas contain the greatest area of glaciers and permafrost outside of the poles, and account for the origin of ten of Asia's largest rivers. The two Himalayan states in the east, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh, receive substantial snowfall. The extreme north of West Bengal centred on Darjeeling experiences snowfall, but only rarely.

In South India, particularly the hinterlands of Maharashtra, parts of Karnataka, and Andhra Pradesh, somewhat cooler weather prevails. Minimum temperatures in eastern Maharashtra and Chhattisgarh hover around 10 °C (50 °F); in the southern Deccan Plateau, they reach 16 °C (61 °F). Coastal areas—especially those near the Coromandel Coast and adjacent low-elevation interior tracts—are warm, with daily high temperatures of 30 °C (86 °F) and lows of around 21 °C (70 °F). The Western Ghats, including the Nilgiri Range, are exceptional; lows there can fall below freezing.[36] This compares with a range of 12–14 °C (54–57 °F) on the Malabar Coast; there, as is the case for other coastal areas, the Indian Ocean exerts a strong moderating influence on weather.[14] The region averages 800 millimetres (31 in)

Summer

[edit]

Summer in northwestern India starts from April and ends in July, and in the rest of the country from March to May but sometimes lasts to mid June. The temperatures in the north rise as the vertical rays of the Sun reach the Tropic of Cancer. The hottest month for the western and southern regions of the country is April; for most of North India, it is May. Temperatures of 50 °C (122 °F) and higher have been recorded in parts of India during this season. Another striking feature of summer is the Loo. These are strong, gusty, hot, dry winds that blow during the day in India. Direct exposure to the heat that comes with these winds may be fatal.[18] In cooler regions of North India, immense pre-monsoon squall-line thunderstorms, known locally as "Nor'westers", commonly drop large hailstones. In Himachal Pradesh, Summer lasts from mid April till the end of June and most parts become very hot (except in alpine zone which experience mild summer) with the average temperature ranging from 28 °C (82 °F) to 32 °C (90 °F).[37] Near the coast, the temperature hovers around 36 °C (97 °F), and the proximity of the sea increases the level of humidity. In southern India, the temperatures are higher on the east coast by a few degrees compared to the west coast.

By May, most of the Indian interior experiences mean temperatures over 32 °C (90 °F), while maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F). In the hot months of April and May, western disturbances, with their cooling influence, may still arrive, but rapidly diminish in frequency as summer progresses.[38] Notably, a higher frequency of such disturbances in April correlates with a delayed monsoon onset (thus extending summer) in northwest India. In eastern India, monsoon onset dates have been steadily advancing over the past several decades, resulting in shorter summers there.[24]

Altitude affects the temperature to a large extent, with higher parts of the Deccan Plateau and other areas being relatively cooler. Hill stations, such as Ootacamund ("Ooty") in the Western Ghats and Kalimpong in the eastern Himalayas, with average maximum temperatures of around 25 °C (77 °F), offer some respite from the heat. At lower elevations, in parts of northern and western India, a strong, hot, and dry wind known as the loo blows in from the west during the daytime; with very high temperatures, in some cases up to around 45 °C (113 °F); it can cause fatal cases of sunstroke. Tornadoes may also occur, concentrated in a corridor stretching from northeastern India towards Pakistan. They are rare, however; only several dozen have been reported since 1835.

Monsoon

[edit]

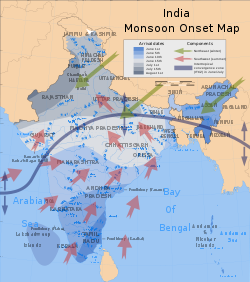

The southwest summer monsoon, a four-month period when massive convective thunderstorms dominate India's weather, is Earth's most productive wet season.[39] A product of southeast trade winds originating from a high-pressure mass centred over the southern Indian Ocean, the monsoonal torrents supply over 80% of India's annual rainfall.[40] Attracted by a low-pressure region centred over South Asia, the mass spawns surface winds that ferry humid air into India from the southwest.[41] These inflows ultimately result from a northward shift of the local jet stream, which itself results from rising summer temperatures over Tibet and the Indian subcontinent. The void left by the jet stream, which switches from a route just south of the Himalayas to one tracking north of Tibet, then attracts warm, humid air.[42]

The main factor behind this shift is the high summer temperature difference between Central Asia and the Indian Ocean.[43] This is accompanied by a seasonal excursion of the normally equatorial intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ), a low-pressure belt of highly unstable weather, northward towards India.[42] This system intensified to its present strength as a result of the Tibetan Plateau's uplift, which accompanied the Eocene–Oligocene transition event, a major episode of global cooling and aridification which occurred 34–49 Ma.[44]

The southwest monsoon arrives in two branches: the Bay of Bengal branch and the Arabian Sea branch. The latter extends towards a low-pressure area over the Thar Desert and is roughly three times stronger than the Bay of Bengal branch. The monsoon typically breaks over Indian territory by around 25 May, when it lashes the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. It strikes the Indian mainland around 1 June near the Malabar Coast of Kerala.[45] By 9 June, it reaches Mumbai; it appears over Delhi by 29 June. The Bay of Bengal branch, which initially tracks the Coromandel Coast northeast from Cape Comorin to Orissa, swerves to the northwest towards the Indo-Gangetic Plain. The Arabian Sea branch moves northeast towards the Himalayas. By the first week of July, the entire country experiences monsoon rain; on average, South India receives more rainfall than North India. However, Northeast India receives the most precipitation. Monsoon clouds begin retreating from North India by the end of August; it withdraws from Mumbai by 5 October. As India further cools during September, the southwest monsoon weakens. By the end of November, it has left the country.[42]

Monsoon rains affect the health of the Indian economy; as Indian agriculture employs 600 million people and constitutes 20% of the national GDP,[4] good monsoons correlate with a booming economy. Weak or failed monsoons (droughts) result in widespread agricultural losses and substantially hinder overall economic growth.[46][47][48] Yet such rains reduce temperatures and can replenish groundwater tables and rivers.

Post-monsoon

[edit]During the post-monsoon or autumn months of October to December, a different monsoon cycle, the northeast (or "retreating") monsoon, brings dry, cool, and dense air masses to large parts of India. Winds spill across the Himalayas and flow to the southwest across the country, resulting in clear, sunny skies.[49] Though the India Meteorological Department (IMD) and other sources refers to this period as a fourth ("post-monsoon") season,[50][51][52] other sources designate only three seasons.[53] Depending on location, this period lasts from October to November, after the southwest monsoon has peaked. Less and less precipitation falls, and vegetation begins to dry out. In most parts of India, this period marks the transition from wet to dry seasonal conditions. Average daily maximum temperatures range between 25 and 34 °C (77 and 93 °F) in the Southern parts.

The northeast monsoon, which begins between September and October, lasts through the post-monsoon seasons, and only ends between December and January. It carries winds that have already lost their moisture out to the ocean (opposite from the summer monsoon). They cross India diagonally from northeast to southwest. However, the large indentation made by the Bay of Bengal into India's eastern coast means that the flows are humidified before reaching Cape Comorin and rest of Tamil Nadu, meaning that the state, and also some parts of Kerala, experience significant precipitation in the post-monsoon and winter periods.[19] However, parts of West Bengal, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Mumbai also receive minor precipitation from the north-east monsoon.

Statistics

[edit]Shown below are temperature and precipitation data for selected Indian cities; these represent the full variety of major Indian climate types. Figures have been grouped by the four-season classification scheme used by the Indian Meteorological Department;[N 1] year-round averages and totals are also displayed.

Temperature

[edit]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Precipitation

[edit]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Disasters

[edit]Climate-related natural disasters cause massive losses of Indian life and property. Droughts, flash floods, cyclones, avalanches, landslides brought on by torrential rains, and snowstorms pose the greatest threats. Other dangers include frequent summer dust storms, which usually track from north to south; they cause extensive property damage in North India[59] and deposit large amounts of dust from arid regions. Hail is also common in parts of India, causing severe damage to standing crops such as rice and wheat.

Floods and landslides

[edit]

In the Lower Himalayas, landslides are common. The young age of the region's hills result in labile rock formations, which are susceptible to slippages. Short duration high intensity rainfall events typically trigger small scale landslides while long duration low intensity rainfall periods tend to trigger large scale catastrophic landslides.[60] Rising population and development pressures, particularly from logging and tourism, cause deforestation. The result, denuded hillsides, exacerbates the severity of landslides, since tree cover impedes the downhill flow of water.[61] Parts of the Western Ghats also suffer from low-intensity landslides. Avalanches occur in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh.

Floods are the most common natural disaster in India. The heavy southwest monsoon rains cause the Brahmaputra and other rivers to distend their banks, often flooding surrounding areas. Though they provide rice paddy farmers with a largely dependable source of natural irrigation and fertilisation, the floods can kill thousands and displace millions. Excess, erratic, or untimely monsoon rainfall may also wash away or otherwise ruin crops.[62] Almost all of India is flood-prone, and extreme precipitation events, such as flash floods and torrential rains, have become increasingly common in central India over the past several decades, coinciding with rising temperatures. Mean annual precipitation totals have remained steady due to the declining frequency of weather systems that generate moderate amounts of rain.[63]

Tropical cyclones

[edit]

Tropical cyclones, which are severe storms spun off from the Intertropical Convergence Zone, may affect thousands of Indians living in coastal regions. Tropical cyclogenesis is particularly common in the northern reaches of the Indian Ocean in and around the Bay of Bengal. Cyclones bring with them heavy rains, storm surges, and winds that often cut affected areas off from relief and supplies. In the North Indian Ocean Basin, the cyclone season runs from April to December, with peak activity between May and November.[64] Each year, an average of eight storms with sustained wind speeds greater than 63 km/h (39 mph) form; of these, two strengthen into true tropical cyclones, which sustain gusts greater than 117 km/h (73 mph). On average, a major (Category 3 or higher) cyclone develops every other year.[64][65]

During summer, the Bay of Bengal is subject to intense heating, giving rise to humid and unstable air masses that morph into cyclones. The 1737 Calcutta cyclone, the 1970 Bhola cyclone, and the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone rank among the most powerful cyclones to strike India, devastating the coasts of eastern India and neighbouring Bangladesh. Widespread death and property destruction are reported every year in the exposed coastal states of West Bengal, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. India's western coast, bordering the more placid Arabian Sea, experiences cyclones only rarely; these mainly strike Gujarat and Maharashtra, less frequently in Kerala.

The 1999 Odisha cyclone was the most intense tropical cyclone in this basin and also the most powerful tropical cyclone to make landfall in India. With peak winds of 260 kilometres per hour (162 mph), it was the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane.[66] Almost two million people were left homeless;[67]another 20 million people lives were disrupted by the cyclone.[67] Officially, 9,803 people died from the storm;[66] unofficial estimates place the death toll at over 10,000.[67]

Droughts

[edit]

Indian agriculture is heavily dependent on the monsoon as a source of water. In some parts of India, the failure of the monsoons results in water shortages, resulting in below-average crop yields. This is particularly true of major drought-prone regions such as southern and eastern Maharashtra, northern Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Western Orissa, Gujarat, and Rajasthan. In the past, droughts have periodically led to major Indian famines. These include the Bengal famine of 1770, in which up to one third of the population in affected areas died; the 1876–1877 famine, in which over five million people died; the 1899 famine, in which over 4.5 million died; and the Bengal famine of 1943, in which over five million died from starvation and famine-related illnesses.[68][69]

All such episodes of severe drought correlate with El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events.[70][71] El Niño-related droughts have also been implicated in periodic declines in Indian agricultural output.[72] Nevertheless, ENSO events that have coincided with abnormally high sea surfaces temperatures in the Indian Ocean—in one instance during 1997 and 1998 by up to 3 °C (5 °F)—have resulted in increased oceanic evaporation, resulting in unusually wet weather across India. Such anomalies have occurred during a sustained warm spell that began in the 1990s.[73] A contrasting phenomenon is that, instead of the usual high pressure air mass over the southern Indian Ocean, an ENSO-related oceanic low pressure convergence centre forms; it then continually pulls dry air from Central Asia, desiccating India during what should have been the humid summer monsoon season. This reversed air flow causes India's droughts.[74] The extent that an ENSO event raises sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean influences the extent of drought.[70]

Heat waves

[edit]A study from 2005 concluded that heat waves significantly increased in frequency, persistence and spatial coverage in the decade 1991–2000, when compared to the period between 1971–80 and 1981–90. A severe heat wave in Orissa in 1998 resulted in nearly 1300 deaths. Based on observations, heat wave related mortality has increased in India prior to 2005.[75] The 2015 Indian heat wave killed more than 2,500 people. In April 2024, the India Meteorological Department (IMD) forecasted a heat wave spell lasting approximately ten to twenty days longer than normal length of four to eight days during the three-month period between April and June.[76] In June 2024, day temperatures reached 44.9 °C (112.8 °F) in New Delhi and temperatures were at their highest in six years overnight. Five people have been reported as dead due to this current heatwave.[77][78]

Extremes

[edit]Extreme temperatures: low

[edit]India's lowest recorded temperature was −45.0 °C (−49 °F) in Dras, Ladakh. However, temperatures on Siachen Glacier near Bilafond La (5,450 metres or 17,881 feet) and Sia La (5,589 metres or 18,337 feet) have fallen below −55 °C (−67 °F),[79] while blizzards bring wind speeds in excess of 250 km/h (155 mph),[80] or hurricane-force winds ranking at 12—the maximum—on the Beaufort scale. These conditions, not hostile actions, caused more than 97% of the roughly 15,000 casualties suffered among Indian and Pakistani soldiers during the Siachen conflict.[79][80][81]

Extreme temperatures: high

[edit]The highest temperature ever recorded in India occurred on 16 May 2016 in Phalodi, Rajasthan at 51.0 °C (124 °F). A temperature of up to 52.4 °C (126 °F) has been recorded in Jaisalmer District on 2 May 2016 near the border of Pakistan but the standard conditions are yet to be verified.

Rain

[edit]

The average annual precipitation of 11,861 millimetres (467 in) in the village of Mawsynram, in the hilly northeastern state of Meghalaya, is the highest recorded in Asia, and possibly on Earth.[82] The village, which sits at an elevation of 1,401 metres (4,596 ft), benefits from its proximity to both the Himalayas and the Bay of Bengal. However, since the town of Cherrapunji, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) to the east, is the nearest town to host a meteorological office—none has ever existed in Mawsynram—it is officially credited as being the world's wettest place.[83] In recent years the Cherrapunji-Mawsynram region has averaged between 9,296 and 10,820 millimetres (366 and 426 in)[9] of rain annually, though Cherrapunji has had at least one period of daily rainfall that lasted almost two years.[84] India's highest recorded one-day rainfall total occurred on 26 July 2005, when Mumbai received 944 mm (37 in);[85] the massive flooding that resulted killed over 900 people.[86][87]

Snow

[edit]Remote regions of Jammu and Kashmir, such as the Pir Panjal Range, experience exceptionally heavy snowfall. Kashmir's highest recorded monthly snowfall occurred in February 1967, when 8.4 metres (27.6 ft) fell in Gulmarg, though the IMD has recorded snowdrifts up to 12 metres (39.4 ft) in several Kashmiri districts. In February 2005, more than 200 people died when, in four days, a western disturbance brought up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) of snowfall to parts of the state.[88]

Climate change

[edit]India was ranked seventh among the list of countries most affected by climate change in 2019.[89] India emits about 3 gigatonnes (Gt) CO2eq of greenhouse gases each year; about two and a half tons per person, which is less than the world average.[90] The country emits 7% of global emissions, despite having 17% of the world population.[91] The climate change performance index of India ranks eighth among 63 countries which account for 92% of all GHG emissions in the year 2021.[92]

Temperature rises on the Tibetan Plateau are causing Himalayan glaciers to retreat, threatening the flow rate of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Yamuna and other major rivers. A 2007 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) report states that the Indus River may run dry for the same reason.[93] Severe landslides and floods are projected to become increasingly common in such states as Assam.[94] Heat waves' frequency and intensity are increasing in India because of climate change.[95] Temperatures in India have risen by 0.7 °C (1.3 °F) between 1901 and 2018.[96]Atmospheric pollution

[edit]

Thick haze and smoke originating from burning biomass in northwestern India[98] and air pollution from large industrial cities in northern India[99] often concentrate over the Ganges Basin. Prevailing westerlies carry aerosols along the southern margins of the sheer-faced Tibetan Plateau towards eastern India and the Bay of Bengal. Dust and black carbon, which are blown towards higher altitudes by winds at the southern margins of the Himalayas, can absorb shortwave radiation and heat the air over the Tibetan Plateau. The net atmospheric heating due to aerosol absorption causes the air to warm and convect upwards, increasing the concentration of moisture in the mid-troposphere and providing positive feedback that stimulates further heating of aerosols.[99]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ IMD-designated post-monsoon season coincides with the northeast monsoon, the effects of which are significant only in some parts of India.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Rowley DB (1996). "Age of initiaotion of collision between India and Asia: A review of stratigraphic data" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 145 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:1996E&PSL.145....1R. doi:10.1016/s0012-821x(96)00201-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2006. Retrieved 31 March 2007.

- ^ Ravindranath, Bala & Sharma 2011.

- ^ Chumakov & Zharkov 2003.

- ^ a b CIA World Factbook.

- ^ Grossman et al. 2002.

- ^ Sheth 2006.

- ^ Iwata, Takahashi & Arai 1997.

- ^ Karanth 2006.

- ^ a b Wolpert 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Enzel et al. 1999.

- ^ Pant 2003.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L. & McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2015. (direct: Final Revised Paper Archived 3 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ a b Chang 1967.

- ^ a b Posey 1994, p. 118.

- ^ NCERT, p. 28.

- ^ Heitzman & Worden 1996, p. 97.

- ^ Chouhan 1992, p. 7.

- ^ a b Farooq 2002.

- ^ a b Healy.

- ^ "Nicobar Islands rain forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 124.

- ^ Singhvi & Kar 2004.

- ^ Kimmel 2000.

- ^ a b c Das et al. 2002.

- ^ Carpenter 2005.

- ^ Singh & Kumar 1997.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)" (PDF). India Meteorological Department. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ "Just Like That: A personal Shalimar Bagh in Delhi's spring". Hindustan Times. 22 March 2025. Retrieved 19 September 2025.

- ^ Michael Allaby (1999). "A Dictionary of Zoology". Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- ^ Hatwar, Yadav & Rama Rao 2005.

- ^ Hara, Kimura & Yasunari.

- ^ "Amritsar Climate Normals 1971–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Government of Bihar.

- ^ Air India 2003.

- ^ Singh, Ojha & Sharma 2004, p. 168.

- ^ Blasco, Bellan & Aizpuru 1996.

- ^ Changnon 1971.

- ^ Pisharoty & Desai 1956.

- ^ Collier & Webb 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Bagla 2006.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 118.

- ^ a b c Burroughs 1999, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Burns et al. 2003.

- ^ Dupont-Nivet et al. 2007.

- ^ India Meteorological Department & A.

- ^ Vaswani 2006b.

- ^ BBC 2004.

- ^ BBC Weather & A.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 119.

- ^ Parthasarathy, Munot & Kothawale 1994.

- ^ India Meteorological Department & B.

- ^ Library of Congress.

- ^ O'Hare 1997.

- ^ "Regional Meteorological Department, Kolkata". Archived from the original on 5 December 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ a b BBC Weather & B.

- ^ a b Weatherbase.

- ^ a b Weather Channel.

- ^ a b Weather Underground.

- ^ Balfour 2003, p. 995.

- ^ Dahal, Ranjan Kumar; Hasegawa, Shuichi (15 August 2008). "Representative rainfall thresholds for landslides in the Nepal Himalaya". Geomorphology. 100 (3–4): 429–443. Bibcode:2008Geomo.100..429D. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.01.014.

- ^ Allaby 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Allaby 1997, pp. 15, 42.

- ^ Goswami et al. 2006.

- ^ a b AOML FAQ G1.

- ^ AOML FAQ E10.

- ^ a b Typhoon Warning Centre.

- ^ a b c BAPS 2005.

- ^ Nash 2002, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Collier & Webb 2002, p. 67.

- ^ a b Kumar et al. 2006.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 121.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 259.

- ^ Nash 2002, pp. 258–259.

- ^ Caviedes 2001, p. 117.

- ^ R.K.Dube and G.S.Prakasa Rao (2005). "Extreme Weather Events over India in the last 100 years" (PDF). Ind. Geophys. Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Jadhav, Rajendra (1 April 2024). "India braces for heat waves in Q2, impact seen on inflation, election". Retrieved 2 April 2024.

- ^ Patel, Shivam; Agarwala, Tora (19 June 2024). "India reports over 40,000 suspected heatstroke cases over summer". Reuters.

- ^ Desk, India TV News; News, India TV (17 June 2024). "Heatwave: Red alert in Delhi, Check IMD's predictions for upcoming days". India TV News. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b McGirk & Adiga 2005.

- ^ a b Ali 2002.

- ^ Desmond 1989.

- ^ NCDC 2004.

- ^ BBC & Giles.

- ^ Kushner 2006.

- ^ BBC 2005.

- ^ The Hindu 2006.

- ^ Vaswani 2006a.

- ^ GOI Ministry of Home Affairs 2005.

- ^ Eckstein, David; Künzel, Vera; Schäfer, Laura (January 2021). "Global Climate Risk Index 2021" (PDF). GermanWatch.org.

- ^ "Greenhouse Gas Emissions in India" (PDF). September 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Emissions Gap Report 2019". UN Environment Programme. 2019. Archived from the original on 20 November 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Climate Change Performance Index" (PDF). November 2022. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "How climate change hits India's poor". BBC News. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "Warmer Tibet can see Brahmaputra flood Assam | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. 3 February 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Coleman, Jude (29 May 2024). "Chance of heatwaves in India rising with climate change". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-01577-5. PMID 38811783.

- ^ Sharma, Vibha (15 June 2020). "Average temperature over India projected to rise by 4.4 degrees Celsius: Govt report on impact of climate change in country". Tribune India. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Haze and smog across Northern India". NASA. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- ^ Badarinath et al. 2006.

- ^ a b Lau 2005.

References

[edit]Articles

- Ali, A. (2002), "A Siachen Peace Park: The Solution to a Half-Century of International Conflict?", Mountain Research and Development, vol. 22, no. 4 (published November 2002), pp. 316–319, doi:10.1659/0276-4741(2002)022[0316:ASPPTS]2.0.CO;2, ISSN 0276-4741

- Badarinath, K. V. S.; Chand, T. R. K.; Prasad, V. K. (2006), "Agriculture Crop Residue Burning in the Indo-Gangetic Plains—A Study Using IRS-P6 AWiFS Satellite Data" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 91, no. 8, pp. 1085–1089, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Bagla, P. (2006), "Controversial Rivers Project Aims to Turn India's Fierce Monsoon into a Friend", Science, vol. 313, no. 5790 (published August 2006), pp. 1036–1037, doi:10.1126/science.313.5790.1036, ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 16931734, S2CID 41809883

- Blasco, F.; Bellan, M. F.; Aizpuru, M. (1996), "A Vegetation Map of Tropical Continental Asia at Scale 1:5 Million", Journal of Vegetation Science, vol. 7, no. 5 (published October 1996), pp. 623–634, Bibcode:1996JVegS...7..623B, doi:10.2307/3236374, JSTOR 3236374

- Burns, S. J.; Fleitmann, D.; Matter, A.; Kramers, J.; Al-Subbary, A. A. (2003), "Indian Ocean Climate and an Absolute Chronology over Dansgaard/Oeschger Events 9 to 13", Science, vol. 301, no. 5638, pp. 635–638, Bibcode:2003Sci...301.1365B, doi:10.1126/science.1086227, ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 12958357, S2CID 41605846

- Carpenter, C. (2005), "The Environmental Control of Plant Species Density on a Himalayan Elevation Gradient", Journal of Biogeography, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 999–1018, Bibcode:2005JBiog..32..999C, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01249.x, S2CID 83279321

- Chang, J. H. (1967), "The Indian Summer Monsoon", Geographical Review, vol. 57, no. 3, American Geographical Society, Wiley, pp. 373–396, Bibcode:1967GeoRv..57..373C, doi:10.2307/212640, JSTOR 212640

- Changnon, S. A. (1971), "Note on Hailstone Size Distributions", Journal of Applied Meteorology, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 168–170, Bibcode:1971JApMe..10..169C, doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1971)010<0169:NOHSD>2.0.CO;2

- Chumakov, N. M.; Zharkov, M. A. (2003), "Climate of the Late Permian and Early Triassic: General Inferences" (PDF), Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 361–375, archived (PDF) from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Das, M. R.; Mukhopadhyay, R. K.; Dandekar, M. M.; Kshirsagar, S. R. (2002), "Pre-Monsoon Western Disturbances in Relation to Monsoon Rainfall, Its Advancement over Northwestern India and Their Trends" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 82, no. 11, pp. 1320–1321, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- De, U.; Dube, R.; Rao, G. (2005), "Extreme Weather Events over India in the last 100 years" (PDF), Journal of Indian Geophysical Union, 3 (3): 173–187, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016, retrieved 31 October 2016

- Dupont-Nivet, G.; Krijgsman, W.; Langereis, C. G.; Abels, H. A.; Dai, S.; Fang, X. (2007), "Tibetan Plateau Aridification Linked to Global Cooling at the Eocene–Oligocene Transition", Nature, vol. 445, no. 7128, pp. 635–638, doi:10.1038/nature05516, ISSN 0028-0836, PMID 17287807, S2CID 2039611

- Enzel, Y.; Ely, L. L.; Mishra, S.; Ramesh, R.; Amit, R.; Lazar, B.; Rajaguru, S. N.; Baker, V. R.; et al. (1999), "High-Resolution Holocene Environmental Changes in the Thar Desert, Northwestern India", Science, vol. 284, no. 5411, pp. 125–128, Bibcode:1999Sci...284..125E, doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.125, ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 10102808

- Goswami, B. N.; Venugopal, V.; Sengupta, D.; Madhusoodanan, M. S.; Xavier, P. K. (2006), "Increasing Trend of Extreme Rain Events over India in a Warming Environment", Science, vol. 314, no. 5804, pp. 1442–1445, Bibcode:2006Sci...314.1442G, doi:10.1126/science.1132027, ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 17138899, S2CID 43711999

- Grossman, E. L.; Bruckschen, P.; Mii, H.; Chuvashov, B. I.; Yancey, T. E.; Veizer, J. (2002), "Climate of the Late Permian and Early Triassic: General Inferences" (PDF), Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Paleogeography in Eurasia, pp. 61–71, archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2005, retrieved 5 April 2007

- Hatwar, H. R.; Yadav, B. P.; Rama Rao, Y. V. (March 2005), "Prediction of Western Disturbances and Associated Weather over the Western Himalayas" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 88, no. 6, pp. 913–920, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2013, retrieved 23 March 2007

- Iwata, N.; Takahashi, N.; Arai, S. (1997), "Geochronological Study of the Deccan Volcanism by the 40Ar-39Ar Method", University of Tokyo (PhD thesis), vol. 10, p. 22, doi:10.1046/j.1440-1738.2001.00290.x, hdl:2297/19562, S2CID 129285078, archived from the original on 21 May 2023, retrieved 3 February 2023

- Karanth, K. P. (2006), "Out-of-India Gondwanan Origin of Some Tropical Asian Biota" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 90, no. 6 (published March 2006), pp. 789–792, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019, retrieved 8 April 2007

- Kumar, B.; Rajagopatan; Hoerling, M.; Bates, G.; Cane, M. (2006), "Unraveling the Mystery of Indian Monsoon Failure During El Niño", Science, vol. 314, no. 5796, pp. 115–119, Bibcode:2006Sci...314..115K, doi:10.1126/science.1131152, ISSN 0036-8075, PMID 16959975, S2CID 7085413

- Kushner, S. (2006), "The Wettest Place on Earth", Faces, vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 36–37, ISSN 0749-1387

- Normile, D. (2000), "Some Coral Bouncing Back from El Niño", Science, vol. 288, no. 5468, pp. 941–942, doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.941a, PMID 10841705, S2CID 128503395, archived from the original on 2 May 2009, retrieved 5 April 2007

- O'Hare, G. (1997), "The Indian Monsoon, Part Two: The Rains", Geography, vol. 82, no. 4, p. 335

- Pant, G. B. (2003), "Long-Term Climate Variability and Change over Monsoonal Asia" (PDF), Journal of the Indian Geophysical Union, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 125–134, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Parthasarathy, B.; Munot, A. A.; Kothawale, D. R. (1994), "All-India Monthly and Seasonal Rainfall Series: 1871–1993", Theoretical and Applied Climatology, vol. 49, no. 4 (published December 1994), pp. 217–224, Bibcode:1994ThApC..49..217P, doi:10.1007/BF00867461, ISSN 0177-798X, S2CID 122512894

- Peterson, R. E.; Mehta, K. C. (1981), "Climatology of Tornadoes of India and Bangladesh", Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics, vol. 29, no. 4 (published December 1981), pp. 345–356, Bibcode:1981AMGBB..29..345P, doi:10.1007/bf02263310, S2CID 118445516

- Pisharoty, P. R.; Desai, B. N. (1956), "Western Disturbances and Indian Weather", Indian Journal of Meteorological Geophysics, vol. 7, pp. 333–338

- Rowley, D. B. (1996), "Age of Initiation of Collision Between India and Asia: A Review of Stratigraphic Data" (PDF), Earth and Planetary Science Letters, vol. 145, no. 1, pp. 1–13, Bibcode:1996E&PSL.145....1R, doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(96)00201-4, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2006, retrieved 31 March 2007

- Sheth, H. C. (2006), Deccan Traps: The Deccan Beyond the Plume Hypothesis (published 29 August 2006), archived from the original on 26 February 2011, retrieved 1 April 2007

- Singh, P.; Kumar, N. (1997), "Effect of Orography on Precipitation in the Western Himalayan Region", Journal of Hydrology, vol. 199, no. 1, pp. 183–206, Bibcode:1997JHyd..199..183S, doi:10.1016/S0022-1694(96)03222-2

- Singhvi, A. K.; Kar, A. (2004), "The Aeolian Sedimentation Record of the Thar Desert" (PDF), Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences (Earth Planet Sciences), vol. 113, no. 3 (published September 2004), pp. 371–401, Bibcode:2004InEPS.113..371S, doi:10.1007/bf02716733, S2CID 128812820, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

Books

- Allaby, M. (1997), Floods, Dangerous Weather, Facts on File (published December 1997), ISBN 978-0-8160-3520-5

- Allaby, M. (2001), Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate, Garratt, R. (illustrator) (1st ed.), Facts on File (published December 2001), ISBN 978-0-8160-4071-1

- Balfour, E. G. (2003), Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising the Indian Subcontinent, Eastern, and Southern Asia, Cosmo Publications (published 30 November 2003), ISBN 978-81-7020-325-4

- Burroughs, W. J. (1999), The Climate Revealed (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-77081-1

- Caviedes, C. N. (2001), El Niño in History: Storming Through the Ages (1st ed.), University Press of Florida (published 18 September 2001), ISBN 978-0-8130-2099-0

- Chouhan, T. S. (1992), Desertification in the World and Its Control, Scientific Publishers, ISBN 978-81-7233-043-9

- Collier, W.; Webb, R. H. (2002), Floods, Droughts, and Climate Change, University of Arizona Press (published 1 November 2002), ISBN 978-0-8165-2250-7

- Heitzman, J.; Worden, R. L. (1996), "India: A Country Study", Library of Congress, Area Handbook Series (5th ed.), United States Government Printing Office (published August 1996), ISBN 978-0-8444-0833-0

- Hossain, M. (2011), "Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies for Bangladesh", Climate Change and Growth in Asia, Edward Elgar Publishing (published 11 May 2011), ISBN 978-1-84844-245-0

- Nash, J. M. (2002), El Niño: Unlocking the Secrets of the Master Weather Maker, Warner Books (published 12 March 2002), ISBN 978-0-446-52481-0

- Posey, C. A. (1994), The Living Earth Book of Wind and Weather, Reader's Digest Association (published 1 November 1994), ISBN 978-0-89577-625-9

- Singh, V. P.; Ojha, C. S. P.; Sharma, N., eds. (2004), The Brahmaputra Basin Water Resources (1st ed.), Springer (published 29 February 2004), ISBN 978-1-4020-1737-7

- Wolpert, S. (1999), A New History of India (6th ed.), Oxford University Press (published 25 November 1999), ISBN 978-0-19-512877-2

Items

- Aggarwal, D.; Lal, M., "Vulnerability of the Indian Coastline to Sea Level Rise", SURVAS Flood Hazard Research Centre

- Dasgupta, S. (2007), Warmer Tibet Can See Brahmaputra Flood Assam, Times of India (published 3 February 2007), archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Desmond, E. W. (1989), The Himalayas: War at the Top of the World, Time (published 31 July 1989), archived from the original on 13 October 2007, retrieved 7 April 2007

- Farooq, O. (2002), "India's Heat Wave Tragedy", BBC News (published 17 May 2002), archived from the original on 10 January 2014, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Giles, B., "Deluges", BBC Weather

- Hara, M.; Kimura, F.; Yasunari, T., "The Generation Mechanism of the Western Disturbances over the Himalayas", Hydrospheric Atmospheric Research Centre, Nagoya University

- Harrabin, R. (2007), "How climate change hits India's poor", BBC News (published 1 February 2007), archived from the original on 27 January 2020, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Healy, M., South Asia: Monsoons, Harper College, archived from the original on 29 September 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Kimmel, T. M. (2000), Weather and Climate: Koppen Climate Classification Flow Chart, University of Texas at Austin, archived from the original on 15 January 2016, retrieved 8 April 2007

- Lau, W. K. M. (2005), Aerosols May Cause Anomalies in the Indian Monsoon, Climate and Radiation Branch, Goddard Space Flight Centre, NASA (published 20 February 2005), archived from the original (PHP) on 1 October 2006, retrieved 10 September 2011

- Mago, C. (2005), High Water, Heat Wave, Hope Floats, Times of India (published 20 June 2005)

- McGirk, T.; Adiga, A. (2005), "War at the Top of the World", Time (published 4 May 2005), archived from the original on 15 December 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Ravindranath, N. H.; Bala, G.; Sharma, S. K. (2011), "In This Issue" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 101, no. 3 (published 10 August 2011), pp. 255–256, archived (PDF) from the original on 12 November 2014, retrieved 3 October 2011

- Sethi, N. (2007), Global Warming: Mumbai to Face the Heat, Times of India (published 3 February 2007), archived from the original on 13 October 2007, retrieved 18 March 2007

- Vaswani, K. (2006), "India's Forgotten Farmers Await Monsoon", BBC News (published 20 June 2006), archived from the original on 11 February 2007, retrieved 23 April 2007

- Vaswani, K. (2006), "Mumbai Remembers Last Year's Floods", BBC News (published 27 July 2006), archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

Other

- "Air India Reschedules Delhi-London/New York and Frankfurt Flights Due to Fog", Air India (published 17 December 2003), 2003, archived from the original on 19 July 2006, retrieved 18 March 2007

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division, Frequently Asked Questions: What Are the Average, Most, and Least Tropical Cyclones Occurring in Each Basin?, NOAA, archived from the original on 31 July 2012, retrieved 25 July 2006

- Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division, Frequently Asked Questions: When Is Hurricane Season?, NOAA, archived from the original on 16 April 2008, retrieved 25 July 2006

- "1999 Supercyclone of Orissa", BAPS Care International, 2005

- "Millions Suffer in Indian Monsoon", BBC News, 1 August 2005, archived from the original on 11 August 2014, retrieved 1 October 2011

- "India Records Double-Digit Growth", BBC News (published 31 March 2004), 2004, archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 23 April 2007

- "Rivers Run Towards "Crisis Point"", BBC News, 20 March 2007, archived from the original on 3 April 2012, retrieved 1 October 2011

- "The Impacts of the Asian Monsoon", BBC Weather, archived from the original on 29 March 2007, retrieved 23 April 2007

- "Country Guide: India", BBC Weather, archived from the original on 25 May 2005, retrieved 23 March 2007

- Soil and Climate of Bihar, Government of Bihar, archived from the original on 28 September 2011, retrieved 13 September 2011

- "Snow Fall and Avalanches in Jammu and Kashmir" (PDF), National Disaster Management Division, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 28 February 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2007, retrieved 24 March 2007

- "Rain Brings Mumbai to a Halt, Rescue Teams Deployed", The Hindu, 5 July 2006, archived from the original on 7 July 2006, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Southwest Monsoon: Normal Dates of Onset, India Meteorological Department, archived from the original on 27 September 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- "Rainfall during pre-monsoon season", India Meteorological Department, archived from the original on 19 December 2006, retrieved 26 March 2007

- "A Country Study: India", Library of Congress Country Studies, Library of Congress (Federal Research Division), archived from the original on 14 July 2012, retrieved 26 March 2007

- Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation, National Climatic Data Centre (published 9 August 2004), 2004, archived from the original on 2 October 2011, retrieved 1 October 2011

- "Climate" (PDF), National Council of Educational Research and Training, p. 28, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2006, retrieved 31 March 2007

- Himalayan Meltdown Catastrophic for India, Times of India, 3 April 2007, archived from the original on 16 December 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- "Tropical Cyclone 05B", Naval Maritime Forecast Centre (Joint Typhoon Warning Centre), United States Navy

- "Early Warning Signs: Coral Reef Bleaching", Union of Concerned Scientists, 2005, archived from the original on 18 July 2008, retrieved 1 October 2011

- Weatherbase, archived from the original on 22 March 2007, retrieved 24 March 2007

- "Wunderground", Weather Underground, archived from the original on 21 March 2007, retrieved 24 March 2007

- "Weather.com", The Weather Channel, archived from the original on 23 March 2007, retrieved 23 March 2007

- "India", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, archived from the original on 18 March 2021, retrieved 1 October 2011

Further reading

[edit]- Toman, M. A.; Chakravorty, U.; Gupta, S. (2003), India and Global Climate Change: Perspectives on Economics and Policy from a Developing Country, Resources for the Future Press (published 1 June 2003), ISBN 978-1-891853-61-6.

External links

[edit]General overview

- "Country Guide: India", BBC Weather, archived from the original on 25 May 2005, retrieved 24 March 2007

Maps, imagery, and statistics

- "India Meteorological Department", Government of India, archived from the original on 4 November 2014, retrieved 2 September 2006

- "Weather Resource System for India", National Informatics Centre, archived from the original on 29 April 2007

- "Extreme Weather Events over India in the last 100 years" (PDF), Indian Geophysical Union, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016, retrieved 31 October 2016

Forecasts

- "India: Current Weather Conditions", National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, archived from the original on 25 April 2007

Climate of India

View on GrokipediaPaleoclimatic History

Geological Formation and Early Climates

The Indian subcontinent originated as part of the Gondwanan supercontinent, which underwent initial fragmentation phases during the late Triassic to early Jurassic periods, with India's subsequent northward drift accelerating after rifting from Antarctica and Australia around 120 million years ago in the Cretaceous.[4] This isolation as a microplate facilitated its rapid migration northward at rates exceeding 15 cm per year, culminating in the collision with the Eurasian plate approximately 50 million years ago during the Eocene epoch.[5] The convergence compressed and uplifted the Tethyan oceanic crust, initiating the formation of the Himalayan orogeny and the Tibetan Plateau, which redirected atmospheric circulation by creating a high-elevation barrier that enhanced seasonal pressure gradients between the Asian landmass and the Indian Ocean.[6][7] This tectonic collision fundamentally altered paleoclimate dynamics, fostering the precursors to modern monsoon systems through intensified summer heating over the elevated Tibetan Plateau, which drew moist air masses northward and promoted rainfall seasonality.[8] Marine sedimentary archives from the Indian Ocean, including oxygen isotope ratios in foraminifera, indicate post-collision increases in precipitation intensity around 45-50 million years ago, reflecting enhanced hydrological cycling tied to the uplift's influence on trade winds and jet stream positioning.[9] Concurrently, continental records show vegetation transitions from gymnosperm-dominated arid-adapted assemblages to angiosperm-rich humid forests, as preserved in Eocene coal and lignite deposits across peninsular India.[10] Paleoclimate proxies further delineate epochal contrasts: Eocene conditions (56-33.9 million years ago) were characterized by elevated temperatures (global averages 5-8°C warmer than present) and high humidity, evidenced by fossil pollen spectra dominated by tropical evergreen taxa and carbon isotope signatures indicating dense forest cover with minimal aridity.[11] In contrast, Miocene phases (23-5.3 million years ago) exhibit proxy-indicated drying trends, with pollen records from Siwalik sediments revealing a shift toward deciduous and savanna elements, likely driven by progressive Himalayan exhumation amplifying rain shadows and global cooling that reduced overall moisture influx despite maturing monsoon dynamics.[12][13] These changes underscore the causal role of orogenic uplift in modulating India's early climate regimes, independent of later orbital or anthropogenic forcings.[14]Quaternary Variations and Monsoon Evolution

The Quaternary Period, encompassing the last 2.6 million years, featured pronounced climatic oscillations in India driven primarily by Milankovitch cycles, which altered seasonal insolation contrasts and thereby modulated the strength of the Indian Summer Monsoon (ISM). Glacial maxima generally corresponded to weakened ISM circulation, reduced precipitation, and expanded arid landscapes, as lower Northern Hemisphere summer insolation suppressed the land-sea thermal gradient essential for monsoon dynamics. Interglacial phases, conversely, exhibited intensified monsoons with higher rainfall, fostering denser vegetation and fuller lakes, as evidenced by multi-proxy reconstructions from marine sediments, terrestrial pollen, and isotopic analyses. These variations were further influenced by global ice volume changes and atmospheric CO₂ levels, with proxy data indicating a causal link between orbital forcing and monsoon precipitation on timescales of 20,000–100,000 years.[15][16] During the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), approximately 21,000–18,000 years ago, the ISM reached a nadir of intensity, resulting in widespread desiccation across peninsular and northern India. Lake levels in regions like the Deccan Plateau and eastern Ghats plummeted, with sediment cores revealing aeolian sands, evaporites, and pollen assemblages indicative of sparse, drought-tolerant xerophytic vegetation rather than monsoon-dependent forests. Sea surface temperatures in the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea were roughly 3°C cooler than present, accompanied by seawater δ¹⁸O depletions of about 0.6‰, signaling diminished vapor transport from ocean sources to the subcontinent. Brackish phases in coastal lakes, such as those inferred from sediment geochemistry in eastern India, reflect episodic marine incursions amid low freshwater inflow, underscoring the monsoon's collapse under reduced insolation and expanded polar ice caps. These conditions likely constrained human populations to refugia, with archaeological evidence suggesting limited migration corridors until post-LGM amelioration.[17][18] The deglaciation phase from ~18,000 to 11,700 years ago marked a progressive ISM revival, accelerating into the early Holocene (11,700–8,000 years ago) with monsoon precipitation surging in response to rising Northern Hemisphere insolation from precessional forcing. Speleothem δ¹⁸O records from caves in southern and northeastern India display enriched values during this interval, denoting increased moisture recycling and intensified convection over the subcontinent. Lake sediment proxies, including ostracod assemblages and organic carbon content, corroborate expanded lacustrine systems and fluvial activity, transitioning landscapes from steppe-like aridity to savanna and woodland mosaics. This Holocene wet phase, peaking in the Climatic Optimum (~9,000–5,000 years ago), facilitated early agricultural dispersals and Neolithic settlements, as stronger monsoons supported reliable rainfall for millet and rice cultivation in river valleys. Orbital maxima at this time shifted the Intertropical Convergence Zone northward, enhancing ISM duration and volume by up to 20–30% relative to LGM baselines, per model-proxy syntheses.[19][20][21] Mid-Holocene monsoon dynamics shifted toward weakening after ~5,000 years ago, culminating in aridification around 4,200 years before present (BP), as declining insolation reduced the thermal contrast driving ISM flow. Proxy indicators, including lowered lake levels in Rajasthan and Gujarat, diminished speleothem growth rates, and pollen shifts to drought-resistant taxa, document a ~10–20% precipitation drop, with regional droughts persisting for centuries. This 4.2 ka event, a global aridity pulse tied to solar minima and high-latitude cooling, stressed rain-fed agroecosystems in northwest India, correlating with the abandonment of major Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) urban centers like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa between 4,200 and 3,900 years BP. While socio-economic factors contributed, paleoclimatic data emphasize hydroclimatic stress—evidenced by silted rivers and reduced fluvial discharge—as a primary driver, prompting population migrations eastward to monsoon-resilient Ganges plains. Late Holocene ISM variability continued at millennial scales, modulated by internal ocean-atmosphere feedbacks, but without reverting to early Holocene intensities.[22][23][24]Climatic Zones and Regional Variations

Tropical Monsoon Climates