Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solar cell

View on Wikipedia

A conventional crystalline silicon solar cell (as of 2005). Electrical contacts made from busbars (the larger silver-colored strips) and fingers (the smaller ones) are printed on the silicon wafer. | |

| Component type | Active |

|---|---|

| Working principle | Photovoltaic effect |

| Inventor | Edmond Becquerel |

| Invention year | 1839 |

| First produced | 1950s |

| Electronic symbol | |

A solar cell, also known as a photovoltaic cell (PV cell), is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by means of the photovoltaic effect.[1] It is a type of photoelectric cell, a device whose electrical characteristics (such as current, voltage, or resistance) vary when it is exposed to light. Individual solar cell devices are often the electrical building blocks of photovoltaic modules, known colloquially as "solar panels". Almost all commercial PV cells consist of crystalline silicon, with a market share of 95%. Cadmium telluride thin-film solar cells account for the remainder.[2] The common single-junction silicon solar cell can produce a maximum open-circuit voltage of approximately 0.5 to 0.6 volts.[3]

Photovoltaic cells may operate under sunlight or artificial light. In addition to producing solar power, they can be used as a photodetector (for example infrared detectors), to detect light or other electromagnetic radiation near the visible light range, as well as to measure light intensity.

The operation of a PV cell requires three basic attributes:

- The absorption of light, generating excitons (bound electron-hole pairs), unbound electron-hole pairs (via excitons), or plasmons.

- The separation of charge carriers of opposite types.

- The separate extraction of those carriers to an external circuit.

There are multiple input factors that affect the output power of solar cells, such as temperature, material properties, weather conditions, solar irradiance and more.[4]

A similar type of "photoelectrolytic cell" (photoelectrochemical cell), can refer to devices

- using light to excite electrons that can further be transported by a semiconductor which delivers the energy (like that explored by Edmond Becquerel and implemented in modern dye-sensitized solar cells)

- using light to split water directly into hydrogen and oxygen which can further be used in power generation

In contrast to outputting power directly, a solar thermal collector absorbs sunlight, to produce either

- direct heat as a "solar thermal module" or "solar hot water panel"

- indirect heat to be used to spin turbines in electrical power generation.

Arrays of solar cells are used to make solar modules that generate a usable amount of direct current (DC) from sunlight. Strings of solar modules create a solar array to generate solar power using solar energy, many times using an inverter to convert the solar power to alternating current (AC).

Applications

[edit]Vehicular applications

[edit]

Electric vehicles that operate off of solar energy or sunlight are commonly referred to as solar cars.[5] These vehicles use solar panels to convert absorbed light into electrical energy to be used by electric motors, with any excess energy stored in batteries.[6] Batteries in solar-powered vehicles differ from starting batteries in standard ICE cars because they are fashioned to impart power towards electrical components of the vehicle for a long durations.[7]

The first instance of photovoltaic cells within vehicular applications was around midway through the second half of the 1900s. In an effort to increase publicity and awareness in solar powered transportation Hans Tholstrup decided to set up the first edition of the World Solar Challenge in 1987.[8] It was a 3000 km race across the Australian outback where competitors from industry research groups and top universities around the globe were invited to compete. General Motors ended up winning the event by a significant margin with their Sunraycer vehicle that achieved speeds of over 40 mph. Contrary to popular belief, solar powered cars are one of the oldest alternative energy vehicles.[9]

Cells, modules, panels and systems

[edit]

Multiple solar cells in an integrated group, all oriented in one plane, constitute a solar photovoltaic panel or module. Photovoltaic modules often have a sheet of glass on the sun-facing side, allowing light to pass while protecting the semiconductor wafers. Solar cells connected in series creates an additive higher voltage, while connecting in parallel yields an additive higher current.

Parallel cells without bypass or shunt diodes that experience shade can shut down the weaker (less illuminated) parallel string (each string a number of series connected cells) causing substantial power loss and possible damage because of the reverse bias applied to the shaded cells by their illuminated partners.[10]

Solar modules can be interconnected to create an array with a desired peak DC voltage and loading current capacity. This functionality can also be accomplished with various other solar devices that do more than just create the desired voltages and currents, such as with MPPTs (maximum power point trackers) or module level power electronic (MLPE) units: microinverters or DC-DC optimizers.

Multiple solar cells assembled together in a single plane form a solar photovoltaic (PV) panel or module. These modules typically feature a glass sheet on the sun-facing side, which allows sunlight to pass through while safeguarding the semiconductor wafers from environmental factors. Connecting solar cells in series increases the voltage output, whereas parallel connections enhance the current output.[11]

Solar modules are often equipped with bypass diodes that isolate shaded cells, preventing them from affecting the performance of the entire string. These diodes allow the current to bypass the shaded or underperforming cells, thereby minimizing power loss and reducing the risk of damage.[12]

| Australia | China | France | Germany | Italy | Japan | United Kingdom | United States | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential | 1.8 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 4.9 |

| Commercial | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 4.5 |

| Utility-scale | 2.0 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Source: IEA – Technology Roadmap: Solar Photovoltaic Energy report, 2014 edition[13]: 15 Note: DOE – Photovoltaic System Pricing Trends reports lower prices for the U.S.[14] | ||||||||

By 2020, the United States cost per watt for a utility scale system had declined to $0.94.[15]

Space

[edit]

Solar cells were first used in a prominent application when they were proposed and flown on the Vanguard satellite in 1958, as an alternative power source to the primary battery power source. By adding cells to the outside of the body, the mission time could be extended with no major changes to the spacecraft or its power systems. In 1959 the United States launched Explorer 6, featuring large wing-shaped solar arrays, which became a common feature in satellites. These arrays consisted of 9600 Hoffman solar cells.

By the 1960s, solar cells were (and still are) the main power source for most Earth orbiting satellites and a number of probes into the Solar System, since they offered the best power-to-weight ratio. The success of the space solar power market drove the development of higher efficiencies in solar cells, due to limited other power options and the desire for the best possible cells, up until the National Science Foundation "Research Applied to National Needs" program began to push development of solar cells for terrestrial applications.

In the early 1990s the technology used for space solar cells diverged from the silicon technology used by terrestrial panels, with the spacecraft application shifting to gallium arsenide-based III-V semiconductor materials, which then evolved into the modern III-V multijunction photovoltaic cell used on spacecraft that are lightweight, compact, flexible, and highly efficient. State of the art technology implemented on satellites uses multi-junction photovoltaic cells, which are composed of different p–n junctions with varying bandgaps in order to utilize a wider spectrum of the Sun's energy. Space solar cells additionally diverged from the protective layer used by terrestrial panels, with space applications using flexible laminate layers.

Additionally, large satellites require the use of large solar arrays to produce electricity. These solar arrays need to be broken down to fit in the geometric constraints of the launch vehicle the satellite travels on before being injected into orbit. Historically, solar cells on satellites consisted of several small terrestrial panels folded together. These small panels would be unfolded into a large panel after the satellite is deployed in its orbit. Newer satellites aim to use flexible rollable solar arrays that are very lightweight and can be packed into a very small volume. The smaller size and weight of these flexible arrays drastically decreases the overall cost of launching a satellite due to the direct relationship between payload weight and launch cost of a launch vehicle.[16]

In 2020, the US Naval Research Laboratory conducted its first test of solar power generation in a satellite, the Photovoltaic Radio-frequency Antenna Module (PRAM) experiment aboard the Boeing X-37.[17][18]

History

[edit]The photovoltaic effect was experimentally demonstrated first by French physicist Edmond Becquerel. In 1839, at age 19, he built the world's first photovoltaic cell in his father's laboratory. Willoughby Smith first described the "Effect of Light on Selenium during the passage of an Electric Current" in a 20 February 1873 issue of Nature. In 1883 Charles Fritts built the first solid state photovoltaic cell by coating the semiconductor selenium with a thin layer of gold to form the junctions; the device was only around 1% efficient.[19] Other milestones include:

- 1888 – Russian physicist Aleksandr Stoletov built the first cell based on the outer photoelectric effect discovered by Heinrich Hertz in 1887.[20]

- 1904 – Julius Elster, together with Hans Friedrich Geitel, devised the first practical photoelectric cell.[21]

- 1905 – Albert Einstein proposed a new quantum theory of light and explained the photoelectric effect in a landmark paper, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921.[22]

- 1941 – Vadim Lashkaryov discovered p–n junctions in Cu2O and Ag2S protocells.[23]

- 1946 – Russell Ohl patented the modern junction semiconductor solar cell,[24] while working on the series of advances that would lead to the transistor.

- 1948 - Introduction to the World of Semiconductors states Kurt Lehovec may have been the first to explain the photo-voltaic effect in the peer-reviewed journal Physical Review.[25][26]

- 1954 – The first practical photovoltaic cell was publicly demonstrated at Bell Laboratories.[27] The inventors were Calvin Souther Fuller, Daryl Chapin and Gerald Pearson.[28]

- 1958 – Solar cells gained prominence with their incorporation onto the Vanguard I satellite.[29]

Improved manufacturing methods post 1960s

[edit]Pricing and efficiency Improvements were gradual over the 1960s. One reason that costs remained high was because space users were willing to pay for the best possible cells, leaving no reason to invest in lower-cost, less-efficient solutions. Also, price was determined largely by the semiconductor industry; their move to integrated circuits in the 1960s led to the availability of larger boules at lower relative prices. As their price fell, the price of the resulting cells did as well. These effects lowered 1971 cell costs to some $100,000 per watt.[30]

In late 1969 Elliot Berman joined Exxon's task force which was looking for projects 30 years in the future and in April 1973 he founded Solar Power Corporation (SPC), a wholly owned subsidiary of Exxon at that time.[31][32][33] The group concluded that electrical power would be much more expensive by 2000, and felt that the increase in price would make alternative energy sources more attractive. He conducted a market study and concluded that a price per watt of about $20/watt would create significant demand.[31] To reduce costs, the team

- eliminated the steps of polishing the wafers and coating them with an anti-reflective layer, by relying on rough-sawn wafer surfaces.

- replaced the expensive materials and hand wiring used in space applications with a printed circuit board on the back, acrylic plastic on the front, and silicone glue between the two, "potting" the cells.[34]

- used solar cells that could be made using cast-off material from the electronics market.

By 1973 they announced a product, and SPC convinced Tideland Signal to use its panels to power navigational buoys, initially for the U.S. Coast Guard.[32]

Research and industrial production post 1970's

[edit]Research into solar power for terrestrial applications became prominent with the U.S. National Science Foundation's Advanced Solar Energy Research and Development Division within the "Research Applied to National Needs" program, which ran from 1969 to 1977,[35] and funded research on developing solar power for ground electrical power systems. A 1973 conference, the "Cherry Hill Conference", set forth the technology goals required to achieve this goal and outlined an ambitious project for achieving them, kicking off an applied research program that would be ongoing for several decades.[36] The program was eventually taken over by the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA),[37] which was later merged into the U.S. Department of Energy.

Following the 1973 oil crisis, oil companies used their higher profits to start (or buy) solar firms, and were for decades the largest producers. Exxon, ARCO, Shell, Amoco (later purchased by BP) and Mobil all had major solar divisions during the 1970s and 1980s. Technology companies also participated, including General Electric, Motorola, IBM, Tyco and RCA.[38]

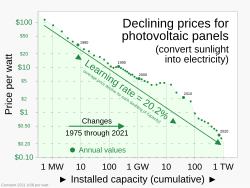

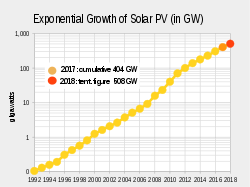

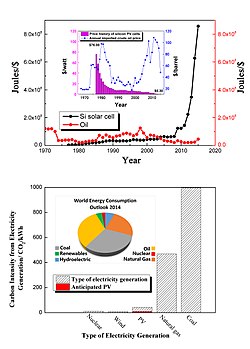

Declining costs and exponential capacity growth

[edit]Adjusting for inflation, it cost $96 per watt for a solar module in the mid-1970s. Process improvements and a very large boost in production have brought that figure down more than 99%, to 30¢ per watt in 2018 [41] and as low as 20¢ per watt in 2020. [42] Swanson's law is an observation similar to Moore's Law that states that solar cell prices fall 20% for every doubling of industry capacity. It was featured in an article in the British weekly newspaper The Economist in late 2012.[43] Balance of system costs are now higher than the solar panels alone, where in 2018 commercial arrays could be built at below $1.00 a watt, fully commissioned.[15]

Over decades, costs for solar cells and panels has declined for many reasons:

- Larger boules. When the semiconductor industry moved to ever-larger boules, older equipment became inexpensive.

- Larger physical solar cell size. Sizes grew as surplus semiconductor equipment became available. ARCO Solar's original panels used cells 2 to 4 inches (50 to 100 mm) in diameter. Panels in the 1990s and early 2000s generally used 125 mm wafers; since 2008, almost all new panels use greater than 156mm cells,[44] and by 2020 even larger 182mm 'M10' cells.[45]

- Availability of large, high-quality glass sheets to cover the panels. Widespread introduction of flat screen televisions in the late 1990s and early 2000s led to such availability.

- Thinner solar cells. High silicon prices in 2004–2008 encouraged silicon solar cell manufacturers to reduce silicon consumption by making them thinner; whereby 2008, according to Jef Poortmans, director of IMEC's organic and solar department, cells used 8–9 grams (0.28–0.32 oz) of silicon per watt of power generation, with typical wafer thicknesses in the neighborhood of 200 microns.

During the 1990s, polysilicon ("poly") cells became increasingly popular. These cells offer less efficiency than their mono-silicon ("mono") counterparts, but are grown in large vats that reduce cost. By the mid-2000s, poly was dominant in the low-cost panel market, but more recently the mono-silicon cells have returned to widespread use due to the efficiency gains.

Crystalline silicon panels dominate worldwide markets and are mostly manufactured in China and Taiwan. By late 2011, a drop in European demand dropped prices for crystalline solar modules to about $1.09[46] per watt down sharply from 2010. Prices continued to fall in 2012, reaching $0.62/watt by 4Q2012.[47]

It was anticipated that electricity from PV will be competitive with wholesale electricity costs all across Europe and the energy payback time of crystalline silicon modules can be reduced to below 0.5 years by 2020.[48]

Falling costs are considered one of the biggest factors in the rapid growth of renewable energy, of 2016, solar PV is growing fastest in Asia, with China and Japan currently accounting for half of worldwide deployment.[49] Costs of solar photovoltaic electricity fell by ~85% between 2010 (when solar and wind made up 1.7% of global electricity generation) and 2021 (where they made up 8.7%).[50] Global installed PV capacity reached at least 301 gigawatts in 2016, and grew to supply 1.3% of global power by 2016.[51] In 2019 solar cells accounted for ~3 % of the world's electricity generation at 720 Tw-hr.[52]

Subsidies and grid parity

[edit]Solar-specific feed-in tariffs vary by and within country countries. Such tariffs can encourage the development of solar power projects and to achieve grid parity. Grid parity, the point at which photovoltaic electricity is equal to or cheaper than grid power without subsidies, is expected to be first achieved in areas with abundant sun and high electricity costs such as in California and Japan.[53] In 2007 BP claimed grid parity for Hawaii and other islands that otherwise use diesel fuel to produce electricity. George W. Bush set 2015 as the date for grid parity in the US.[54][55] The Photovoltaic Association reported in 2012 that Australia had reached grid parity (ignoring feed in tariffs).[56]

The price of solar panels fell steadily for 40 years, interrupted in 2004 when high subsidies in Germany drastically increased demand there and greatly increased the price of purified silicon (which is used in computer chips as well as solar panels). The Great Recession and the onset of Chinese manufacturing caused prices to resume their decline. In the four years after January 2008 prices for solar modules in Germany dropped from €3 to €1 per peak watt. During that same time production capacity surged with an annual growth of more than 50%. China increased solar panel production market share from 8% in 2008 to over 55% in the last quarter of 2010.[57] In December 2012 the price of Chinese solar panels had dropped to $0.60/Wp (crystalline modules).[58] (The abbreviation Wp stands for watt peak capacity, or the maximum capacity under optimal conditions.[59])

As of the end of 2016, it was reported that spot prices for assembled solar panels (not cells) had fallen to a record-low of US$0.36/Wp. The second largest supplier, Canadian Solar Inc., had reported costs of US$0.37/Wp in the third quarter of 2016, having dropped $0.02 from the previous quarter, and hence was probably still at least breaking even. Many producers expected costs would drop to the vicinity of $0.30 by the end of 2017.[60] It was also reported that new solar installations were cheaper than coal-based thermal power plants in some regions of the world, and this was expected to be the case in most of the world within a decade.[61]

Theory

[edit]

A solar cell is made of semiconducting materials, such as silicon, that have been fabricated into a p–n junction. Such junctions are made by doping one side of the device p-type and the other n-type, for example in the case of silicon by introducing small concentrations of boron or phosphorus respectively.

Solar cells use "doping" of the silicon substrate to lower the activation energy thereby making the cell more efficient in converting photons to retrievable electrons.[63] Doping chemicals such as boron (p-type) are applied into the semiconductor crystal in order to create donor and acceptor energy levels substantially closer to the valence and conductor bands.[64] In doing so, the addition of boron impurity allows the activation energy to decrease twenty-fold from 1.12 eV to 0.05 eV. Since the potential difference (EB) is so low, the boron is able to thermally ionize at room temperatures. This allows for free energy carriers in the conduction and valence bands thereby allowing greater conversion of photons to electrons.

In operation, photons in sunlight hit the solar cell and are absorbed by the semiconductor. When the photons are absorbed, electrons are excited from the valence band to the conduction band (or from occupied to unoccupied molecular orbitals in the case of an organic solar cell), producing electron-hole pairs. If the electron-hole pairs are created near the junction between p-type and n-type materials the local electric field sweeps them apart to opposite electrodes, producing an excess of electrons on one side and an excess of holes on the other. When the solar cell is unconnected (or the external electrical load is very high) the electrons and holes will ultimately restore equilibrium by diffusing back across the junction against the field and recombine with each other giving off heat, but if the load is small enough then it is easier for equilibrium to be restored by the excess electrons going around the external circuit, doing useful work along the way.

The most commonly known solar cell is configured as a large-area p–n junction made from silicon. Other possible solar cell types are organic solar cells, dye sensitized solar cells, perovskite solar cells, quantum dot solar cells, etc. The illuminated side of a solar cell generally has a transparent conducting film for allowing light to enter into the active material and to collect the generated charge carriers. Typically, films with high transmittance and high electrical conductance such as indium tin oxide, conducting polymers, or conducting nanowire networks are used for the purpose.[62]

Efficiency

[edit]

Solar cell efficiency may be broken down into reflectance efficiency, thermodynamic efficiency, charge carrier separation efficiency and conductive efficiency. The overall efficiency is the product of these individual metrics.

The power conversion efficiency of a solar cell is a parameter which is defined by the fraction of incident power converted into electricity.[65]

A solar cell has a voltage dependent efficiency curve, temperature coefficients, and allowable shadow angles.

Due to the difficulty in measuring these parameters directly, other parameters are substituted: thermodynamic efficiency, quantum efficiency, integrated quantum efficiency, VOC ratio, and fill factor. Reflectance losses are a portion of quantum efficiency under "external quantum efficiency". Recombination losses make up another portion of quantum efficiency, VOC ratio, and fill factor. Resistive losses are predominantly categorized under fill factor, but also make up minor portions of quantum efficiency, VOC ratio.

The fill factor is the ratio of the actual maximum obtainable power to the product of the open-circuit voltage and short-circuit current. This is a key parameter in evaluating performance. In 2009, typical commercial solar cells had a fill factor > 0.70. Grade B cells were usually between 0.4 and 0.7.[66] Cells with a high fill factor have a low equivalent series resistance and a high equivalent shunt resistance, so less of the current produced by the cell is dissipated in internal losses.

Single p–n junction crystalline silicon devices are now approaching the theoretical limiting power efficiency of 33.16%,[67] noted as the Shockley–Queisser limit in 1961. In the extreme, with an infinite number of layers, the corresponding limit is 86% using concentrated sunlight.[68]

In 2014, three companies broke the record of 25.6% for a silicon solar cell. Panasonic's was the most efficient. The company moved the front contacts to the rear of the panel, eliminating shaded areas. In addition they applied thin silicon films to the (high quality silicon) wafer's front and back to eliminate defects at or near the wafer surface.[69]

In 2015, a 4-junction GaInP/GaAs//GaInAsP/GaInAs solar cell achieved a new laboratory record efficiency of 46.1% (concentration ratio of sunlight = 312) in a French-German collaboration between the Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems (Fraunhofer ISE), CEA-LETI and SOITEC.[70]

In September 2015, Fraunhofer ISE announced the achievement of an efficiency above 20% for epitaxial wafer cells. The work on optimizing the atmospheric-pressure chemical vapor deposition (APCVD) in-line production chain was done in collaboration with NexWafe GmbH, a company spun off from Fraunhofer ISE to commercialize production.[71][72]

For triple-junction thin-film solar cells, the world record is 13.6%, set in June 2015.[73]

In 2016, researchers at Fraunhofer ISE announced a GaInP/GaAs/Si triple-junction solar cell with two terminals reaching 30.2% efficiency without concentration.[74]

In 2017, a team of researchers at National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), EPFL and CSEM (Switzerland) reported record one-sun efficiencies of 32.8% for dual-junction GaInP/GaAs solar cell devices. In addition, the dual-junction device was mechanically stacked with a Si solar cell, to achieve a record one-sun efficiency of 35.9% for triple-junction solar cells.[75]

Materials

[edit]

Solar cells are typically named after the semiconducting material of which they are composed. These materials have varying characteristics to absorb optimal available sunlight spectrum. Some cells are designed to handle sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface, while others are optimized for use in space. Solar cells can be made of a single layer of light-absorbing material (single-junction) or use multiple physical configurations (multi-junctions) to take advantage of various absorption and charge separation mechanisms.

Solar cells can be classified into first, second and third generation:

- First generation cells—also called conventional, traditional or wafer-based cells—are made of crystalline silicon, the commercially predominant PV technology, that includes materials such as polysilicon and monocrystalline silicon.

- Second generation cells are thin film solar cells, that include amorphous silicon, CdTe and CIGS cells and are commercially significant in utility-scale photovoltaic power stations, building integrated photovoltaics or in small stand-alone power system.

- Third generation of solar cells includes a number of thin-film technologies often described as emerging photovoltaics—most of them have not yet been commercially applied and are still in the research or development phase. Many use organic materials, often organometallic compounds as well as inorganic substances. Despite the fact that their efficiencies had been low and the stability of the absorber material was often too short for commercial applications, there is research into these technologies as they promise to achieve the goal of producing low-cost, high-efficiency solar cells.[77]

As of 2016, the most popular and efficient solar cells were those made from thin wafers of silicon which are also the oldest solar cell technology.[78]

Crystalline silicon

[edit]By far, the most prevalent bulk material for solar cells is crystalline silicon (c-Si), also known as "solar grade silicon". Bulk silicon is separated into multiple categories according to crystallinity and crystal size in the resulting ingot, ribbon or wafer. These cells are entirely based around the concept of a p–n junction. Solar cells made of c-Si are made from wafers between 160 and 240 micrometers thick.

Monocrystalline silicon

[edit]

Monocrystalline silicon (mono-Si) solar cells feature a single-crystal composition that enables electrons to move more freely than in a multi-crystal configuration. Consequently, monocrystalline solar panels deliver a higher efficiency than their multicrystalline counterparts.[79] The corners of the cells look clipped, like an octagon, because the wafer material is cut from cylindrical ingots, that are typically grown by the Czochralski process. Solar panels using mono-Si cells display a distinctive pattern of small white diamonds.

Epitaxial silicon development

[edit]Epitaxial wafers of crystalline silicon can be grown on a monocrystalline silicon "seed" wafer by chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and then detached as self-supporting wafers of some standard thickness (e.g., 250 μm) that can be manipulated by hand, and directly substituted for wafer cells cut from monocrystalline silicon ingots. Solar cells made with this "kerfless" technique can have efficiencies approaching those of wafer-cut cells, but at appreciably lower cost if the CVD can be done at atmospheric pressure in a high-throughput inline process.[71][72] The surface of epitaxial wafers may be textured to enhance light absorption.[80][81]

In June 2015, it was reported that heterojunction solar cells grown epitaxially on n-type monocrystalline silicon wafers had reached an efficiency of 22.5% over a total cell area of 243.4 cm.[82]

Polycrystalline silicon

[edit]Polycrystalline silicon, or multicrystalline silicon (multi-Si) cells are made from cast square ingots—large blocks of molten silicon carefully cooled and solidified. They consist of small crystals giving the material its typical metal flake effect. Polysilicon cells are the most common type used in photovoltaics and are less expensive, but also less efficient, than those made from monocrystalline silicon.

Ribbon silicon

[edit]Ribbon silicon is a type of polycrystalline silicon—it is formed by drawing flat thin films from molten silicon and results in a polycrystalline structure. These cells are cheaper to make than multi-Si, due to a great reduction in silicon waste, as this approach does not require sawing from ingots.[83] However, they are also less efficient.

Mono-like-multi silicon (MLM)

[edit]This form was developed in the 2000s and introduced commercially around 2009. Also called cast-mono, this design uses polycrystalline casting chambers with small "seeds" of mono material. The result is a bulk mono-like material that is polycrystalline around the outsides. When sliced for processing, the inner sections are high-efficiency mono-like cells (but square instead of "clipped"), while the outer edges are sold as conventional poly. This production method results in mono-like cells at poly-like prices.[84]

Thin film

[edit]Thin-film technologies reduce the amount of active material in a cell. Most designs sandwich active material between two panes of glass. Since silicon solar panels only use one pane of glass, thin film panels are approximately twice as heavy as crystalline silicon panels, although they have a smaller ecological impact (determined from life cycle analysis).[85][86]

Cadmium telluride

[edit]Cadmium telluride is the only thin film material so far to rival crystalline silicon in cost/watt. However cadmium is highly toxic and tellurium (anion: "telluride") supplies are limited. The cadmium present in the cells would be toxic if released. However, release is impossible during normal operation of the cells and is unlikely during fires in residential roofs.[87] A square meter of CdTe contains approximately the same amount of Cd as a single C cell nickel-cadmium battery, in a more stable and less soluble form.[87]

Copper indium gallium selenide

[edit]Copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) is a direct band gap material. It has the highest efficiency (~20%) among all commercially significant thin film materials (see CIGS solar cell). Traditional methods of fabrication involve vacuum processes including co-evaporation and sputtering. Recent developments at IBM and Nanosolar attempt to lower the cost by using non-vacuum solution processes.[88]

Silicon thin film

[edit]Silicon thin-film cells are mainly deposited by chemical vapor deposition (typically plasma-enhanced, PE-CVD) from silane gas and hydrogen gas. Depending on the deposition parameters, this can yield amorphous silicon (a-Si or a-Si:H), protocrystalline silicon or nanocrystalline silicon (nc-Si or nc-Si:H), also called microcrystalline silicon.[89]

Amorphous silicon is the most well-developed thin film technology to-date. An amorphous silicon (a-Si) solar cell is made of non-crystalline or microcrystalline silicon. Amorphous silicon has a higher bandgap (1.7 eV) than crystalline silicon (c-Si) (1.1 eV), which means it absorbs the visible part of the solar spectrum more strongly than the higher power density infrared portion of the spectrum. The production of a-Si thin film solar cells uses glass as a substrate and deposits a very thin layer of silicon by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD).

Protocrystalline silicon with a low volume fraction of nanocrystalline silicon is optimal for high open-circuit voltage.[90] Nc-Si has about the same bandgap as c-Si and nc-Si and a-Si can advantageously be combined in thin layers, creating a layered cell called a tandem cell. The top cell in a-Si absorbs the visible light and leaves the infrared part of the spectrum for the bottom cell in nc-Si.

Gallium arsenide thin film

[edit]The semiconductor material gallium arsenide (GaAs) is also used for single-crystalline thin film solar cells. Although GaAs cells are very expensive[91], they hold the world's record in efficiency for a single-junction solar cell at 28.8%.[92] Typically fabricated on crystalline silicon wafer[93] with a 41% fill factor, by moving to porous silicon fill factor can be increased to 56% with potentially reduced cost. Using less active GaAs material by fabricating nanowires is another potential pathway to cost reduction.[94] GaAs is more commonly used in multijunction photovoltaic cells for concentrated photovoltaics (CPV, HCPV) and for solar panels on spacecraft, as the industry favours efficiency over cost for space-based solar power.

Multijunction cells

[edit]

Multi-junction cells consist of multiple thin films, each essentially a solar cell grown on top of another, typically using metalorganic vapour phase epitaxy. Each layer has a different band gap energy to allow it to absorb electromagnetic radiation over a different portion of the spectrum. Multi-junction cells were originally developed for special applications such as satellites and space exploration, but are now used increasingly in terrestrial concentrator photovoltaics (CPV), an emerging technology that uses lenses and curved mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto small, highly efficient multi-junction solar cells. By concentrating sunlight up to a thousand times, High concentration photovoltaics (HCPV) has the potential to outcompete conventional solar PV in the future.[95]: 21, 26

Tandem solar cells based on monolithic, series connected, gallium indium phosphide (GaInP), gallium arsenide (GaAs), and germanium (Ge) p–n junctions, are increasing sales, despite cost pressures.[96] Between December 2006 and December 2007, the cost of 4N gallium metal rose from about $350 per kg to $680 per kg. Additionally, germanium metal prices have risen substantially to $1000–1200 per kg this year. Those materials include gallium (4N, 6N and 7N Ga), arsenic (4N, 6N and 7N) and germanium, pyrolitic boron nitride (pBN) crucibles for growing crystals, and boron oxide, these products are critical to the entire substrate manufacturing industry.[97]

A triple-junction cell, for example, may consist of the semiconductors: GaAs, Ge, and GaInP

2.[98] Triple-junction GaAs solar cells were used as the power source of the Dutch four-time World Solar Challenge winners Nuna in 2003, 2005 and 2007 and by the Dutch solar cars Solutra (2005), Twente One (2007) and 21Revolution (2009).[99] GaAs based multi-junction devices are the most efficient solar cells to date. On 15 October 2012, triple junction metamorphic cells reached a record high of 44%.[100] In 2022, researchers at Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE in Freiburg, Germany, demonstrated a record solar cell efficiency of 47.6% under 665-fold sunlight concentration with a four-junction concentrator solar cell.[101][102]

GaInP/Si dual-junction solar cells

[edit]In 2016, a new approach was described for producing hybrid photovoltaic wafers combining the high efficiency of III-V multi-junction solar cells with the economies and wealth of experience associated with silicon. The technical complications involved in growing the III-V material on silicon at the required high temperatures, a subject of study for some 30 years, are avoided by epitaxial growth of silicon on GaAs at low temperature by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD).[103]

Si single-junction solar cells have been widely studied for decades and are reaching their practical efficiency of ~26% under 1-sun conditions.[104] Increasing this efficiency may require adding more cells with bandgap energy larger than 1.1 eV to the Si cell, allowing to convert short-wavelength photons for generation of additional voltage. A dual-junction solar cell with a band gap of 1.6–1.8 eV as a top cell can reduce thermalization loss, produce a high external radiative efficiency and achieve theoretical efficiencies over 45%.[105] A tandem cell can be fabricated by growing the GaInP and Si cells. Growing them separately can overcome the 4% lattice constant mismatch between Si and the most common III–V layers that prevent direct integration into one cell. The two cells therefore are separated by a transparent glass slide so the lattice mismatch does not cause strain to the system. This creates a cell with four electrical contacts and two junctions that demonstrated an efficiency of 18.1%. With a fill factor (FF) of 76.2%, the Si bottom cell reaches an efficiency of 11.7% (± 0.4) in the tandem device, resulting in a cumulative tandem cell efficiency of 29.8%.[106] This efficiency exceeds the theoretical limit of 29.4%[107] and the record experimental efficiency value of a Si 1-sun solar cell, and is also higher than the record-efficiency 1-sun GaAs device. However, using a GaAs substrate is expensive and not practical. Hence researchers try to make a cell with two electrical contact points and one junction, which does not need a GaAs substrate. This means there will be direct integration of GaInP and Si.

Research in solar cells

[edit]Perovskite solar cells

[edit]Perovskite solar cells are solar cells that include a perovskite-structured material as the active layer. Most commonly, this is a solution-processed hybrid organic-inorganic tin or lead halide based material. Efficiencies have increased from below 5% at their first usage in 2009 to 25.5% in 2020, making them a very rapidly advancing technology and a hot topic in the solar cell field.[108] Researchers at University of Rochester reported in 2023 that significant further improvements in cell efficiency can be achieved by utilizing Purcell effect.[109]

Perovskite solar cells are also forecast to be extremely cheap to scale up, making them a very attractive option for commercialisation. So far most types of perovskite solar cells have not reached sufficient operational stability to be commercialised, although many research groups are investigating ways to solve this.[110] Energy and environmental sustainability of perovskite solar cells and tandem perovskite are shown to be dependent on the structures.[111][112][113] Photonic front contacts for light management can improve the perovskite cells' performance, via enhanced broadband absorption, while allowing better operational stability due to protection against the harmful high-energy (above Visible) radiation.[114] The inclusion of the toxic element lead in the most efficient perovskite solar cells is a potential problem for commercialisation.[115]

Bifacial solar cells

[edit]

With a transparent rear side, bifacial solar cells can absorb light from both the front and rear sides. Hence, they can produce more electricity than conventional monofacial solar cells. The first patent of bifacial solar cells was filed by Japanese researcher Hiroshi Mori, in 1966.[116] Later, it is said that Russia was the first to deploy bifacial solar cells in their space program in the 1970s.[citation needed] In 1976, the Institute for Solar Energy of the Technical University of Madrid, began a research program for the development of bifacial solar cells led by Prof. Antonio Luque. Based on 1977 US and Spanish patents by Luque, a practical bifacial cell was proposed with a front face as anode and a rear face as cathode; in previously reported proposals and attempts both faces were anodic and interconnection between cells was complicated and expensive.[117][118][119] In 1980, Andrés Cuevas, a PhD student in Luque's team, demonstrated experimentally a 50% increase in output power of bifacial solar cells, relative to identically oriented and tilted monofacial ones, when a white background was provided.[120] In 1981 the company Isofoton was founded in Málaga to produce the developed bifacial cells, thus becoming the first industrialization of this PV cell technology. With an initial production capacity of 300 kW/yr of bifacial solar cells, early landmarks of Isofoton's production were the 20kWp power plant in San Agustín de Guadalix, built in 1986 for Iberdrola, and an off grid installation by 1988 also of 20kWp in the village of Noto Gouye Diama (Senegal) funded by the Spanish international aid and cooperation programs.

Due to the reduced manufacturing cost, companies have again started to produce commercial bifacial modules since 2010. By 2017, there were at least eight certified PV manufacturers providing bifacial modules in North America. The International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaics (ITRPV) predicted that the global market share of bifacial technology will expand from less than 5% in 2016 to 30% in 2027.[121]

Due to the significant interest in the bifacial technology, a recent study has investigated the performance and optimization of bifacial solar modules worldwide.[122][123] The results indicate that, across the globe, ground-mounted bifacial modules can only offer ~10% gain in annual electricity yields compared to the monofacial counterparts for a ground albedo coefficient of 25% (typical for concrete and vegetation groundcovers). However, the gain can be increased to ~30% by elevating the module 1 m above the ground and enhancing the ground albedo coefficient to 50%. Sun et al. also derived a set of empirical equations that can optimize bifacial solar modules analytically.[122] In addition, there is evidence that bifacial panels work better than traditional panels in snowy environments as bifacials on dual-axis trackers made 14% more electricity in a year than their monofacial counterparts and 40% during the peak winter months.[124]

An online simulation tool is available to model the performance of bifacial modules in any arbitrary location across the entire world. It can also optimize bifacial modules as a function of tilt angle, azimuth angle, and elevation above the ground.[125]

Intermediate band

[edit]Intermediate band photovoltaics in solar cell research provides methods for exceeding the Shockley–Queisser limit on the efficiency of a cell. It introduces an intermediate band (IB) energy level in between the valence and conduction bands. Theoretically, introducing an IB allows two photons with energy less than the bandgap to excite an electron from the valence band to the conduction band. This increases the induced photocurrent and thereby efficiency.[126]

Luque and Marti first derived a theoretical limit for an IB device with one midgap energy level using detailed balance. They assumed no carriers were collected at the IB and that the device was under full concentration. They found the IB maximum efficiency to be 63.2%, for a bandgap of 1.95eV with the IB 0.71eV from either the valence or conduction band ans compared to the under one sun illumination limiting efficiency of 47%.[127] Several means are under study to realize IB semiconductors with such optimum 3-bandgap configuration, namely via materials engineering (controlled inclusion of deep level impurities or highly mismatched alloys) and nano-structuring (quantum-dots in host hetero-crystals).[128]

Liquid inks

[edit]In 2014, researchers at California NanoSystems Institute discovered using kesterite and perovskite improved electric power conversion efficiency for solar cells.[129]

In December 2022, it was reported that MIT researchers had developed ultralight fabric solar cells. These cells offer a weight one-hundredth that of traditional panels while generating 18 times more power per kilogram. Thinner than a human hair, these cells can be laminated onto various surfaces, such as boat sails, tents, tarps, or drone wings, to extend their functionality. Using ink-based materials and scalable techniques, researchers coat the solar cell structure with printable electronic inks, completing the module with screen-printed electrodes. Tested on high-strength fabric, the cells produce 370 watts-per-kilogram, representing an improvement over conventional solar cells.[130]

Upconversion and downconversion

[edit]Photon upconversion is the process of using two low-energy (e.g., infrared) photons to produce one higher energy photon; downconversion is the process of using one high energy photon (e.g., ultraviolet) to produce two lower energy photons. Either of these techniques could be used to produce higher efficiency solar cells by allowing solar photons to be more efficiently used. The difficulty, however, is that the conversion efficiency of existing phosphors exhibiting up- or down-conversion is low, and is typically narrow band.

One upconversion technique is to incorporate lanthanide-doped materials (Er3+

, Yb3+

, Ho3+

or a combination), taking advantage of their luminescence to convert infrared radiation to visible light. Upconversion process occurs when two infrared photons are absorbed by rare-earth ions to generate a (high-energy) absorbable photon. As example, the energy transfer upconversion process (ETU), consists in successive transfer processes between excited ions in the near infrared. The upconverter material could be placed below the solar cell to absorb the infrared light that passes through the silicon. Useful ions are most commonly found in the trivalent state. Er+

ions have been the most used. Er3+

ions absorb solar radiation around 1.54 μm. Two Er3+

ions that have absorbed this radiation can interact with each other through an upconversion process. The excited ion emits light above the Si bandgap that is absorbed by the solar cell and creates an additional electron–hole pair that can generate current. However, the increased efficiency was small. In addition, fluoroindate glasses have low phonon energy and have been proposed as suitable matrix doped with Ho3+

ions.[131]

Light-absorbing dyes

[edit]Dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) are made of low-cost materials and do not need elaborate manufacturing equipment, so they can be made in a DIY fashion. In bulk it should be significantly less expensive than older solid-state cell designs. DSSC's can be engineered into flexible sheets and although its conversion efficiency is less than the best thin film cells, its price/performance ratio may be high enough to allow them to compete with fossil fuel electrical generation.

Typically a ruthenium metalorganic dye (Ru-centered) is used as a monolayer of light-absorbing material, which is adsorbed onto a thin film of titanium dioxide. The dye-sensitized solar cell depends on this mesoporous layer of nanoparticulate titanium dioxide (TiO2) to greatly amplify the surface area (200–300 m2/g TiO

2, as compared to approximately 10 m2/g of flat single crystal) which allows for a greater number of dyes per solar cell area (which in term in increases the current). The photogenerated electrons from the light absorbing dye are passed on to the n-type TiO

2 and the holes are absorbed by an electrolyte on the other side of the dye. The circuit is completed by a redox couple in the electrolyte, which can be liquid or solid. This type of cell allows more flexible use of materials and is typically manufactured by screen printing or ultrasonic nozzles, with the potential for lower processing costs than those used for bulk solar cells. However, the dyes in these cells also suffer from degradation under heat and UV light and the cell casing is difficult to seal due to the solvents used in assembly. Due to this reason, researchers have developed solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells that use a solid electrolyte to avoid leakage.[132] The first commercial shipment of DSSC solar modules occurred in July 2009 from G24i Innovations.[133]

Quantum dots

[edit]Quantum dot solar cells (QDSCs) are based on the Gratzel cell, or dye-sensitized solar cell architecture, but employ low band gap semiconductor nanoparticles, fabricated with crystallite sizes small enough to form quantum dots (such as CdS, CdSe, Sb

2S

3, PbS, etc.), instead of organic or organometallic dyes as light absorbers. Due to the toxicity associated with Cd and Pb based compounds there are also a series of "green" QD sensitizing materials in development (such as CuInS2, CuInSe2 and CuInSeS).[134] QD's size quantization allows for the band gap to be tuned by simply changing particle size. They also have high extinction coefficients and have shown the possibility of multiple exciton generation.[135]

In a QDSC, a mesoporous layer of titanium dioxide nanoparticles forms the backbone of the cell, much like in a DSSC. This TiO

2 layer can then be made photoactive by coating with semiconductor quantum dots using chemical bath deposition, electrophoretic deposition or successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction. The electrical circuit is then completed through the use of a liquid or solid redox couple. The efficiency of QDSCs has increased[136] to over 5% shown for both liquid-junction[137] and solid state cells,[138] with a reported peak efficiency of 11.91%.[139] In an effort to decrease production costs, the Prashant Kamat research group[140] demonstrated a solar paint made with TiO

2 and CdSe that can be applied using a one-step method to any conductive surface with efficiencies over 1%.[141] However, the absorption of quantum dots (QDs) in QDSCs is weak at room temperature.[142] The plasmonic nanoparticles can be utilized to address the weak absorption of QDs (e.g., nanostars).[143] Adding an external infrared pumping source to excite intraband and interband transition of QDs is another solution.[142]

Organic/polymer solar cells

[edit]Organic solar cells and polymer solar cells are built from thin films (typically 100 nm) of organic semiconductors including polymers, such as polyphenylene vinylene and small-molecule compounds like copper phthalocyanine (a blue or green organic pigment) and carbon fullerenes and fullerene derivatives such as PCBM.

They can be processed from liquid solution, offering the possibility of a simple roll-to-roll printing process, potentially leading to inexpensive, large-scale production. In addition, these cells could be beneficial for some applications where mechanical flexibility and disposability are important. Current cell efficiencies are, however, very low, and practical devices are essentially non-existent.

Energy conversion efficiencies achieved to date using conductive polymers are very low compared to inorganic materials. However, Konarka Power Plastic reached efficiency of 8.3%[144] and organic tandem cells in 2012 reached 11.1%.[citation needed]

The active region of an organic device consists of two materials, one electron donor and one electron acceptor. When a photon is converted into an electron hole pair, typically in the donor material, the charges tend to remain bound in the form of an exciton, separating when the exciton diffuses to the donor-acceptor interface, unlike most other solar cell types. The short exciton diffusion lengths of most polymer systems tend to limit the efficiency of such devices. Nanostructured interfaces, sometimes in the form of bulk heterojunctions, can improve performance.[145]

In 2011, MIT and Michigan State researchers developed solar cells with a power efficiency close to 2% with a transparency to the human eye greater than 65%, achieved by selectively absorbing the ultraviolet and near-infrared parts of the spectrum with small-molecule compounds.[146][147] Researchers at UCLA more recently developed an analogous polymer solar cell, following the same approach, that is 70% transparent and has a 4% power conversion efficiency.[148][149][150] These lightweight, flexible cells can be produced in bulk at a low cost and could be used to create power generating windows.

In 2013, researchers announced polymer cells with some 3% efficiency. They used block copolymers, self-assembling organic materials that arrange themselves into distinct layers. The research focused on P3HT-b-PFTBT that separates into bands some 16 nanometers wide.[151][152]

Adaptive cells

[edit]Adaptive cells change their absorption/reflection characteristics depending on environmental conditions. An adaptive material responds to the intensity and angle of incident light. At the part of the cell where the light is most intense, the cell surface changes from reflective to adaptive, allowing the light to penetrate the cell. The other parts of the cell remain reflective increasing the retention of the absorbed light within the cell.[153]

In 2014, a system was developed that combined an adaptive surface with a glass substrate that redirect the absorbed to a light absorber on the edges of the sheet. The system also includes an array of fixed lenses/mirrors to concentrate light onto the adaptive surface. As the day continues, the concentrated light moves along the surface of the cell. That surface switches from reflective to adaptive when the light is most concentrated and back to reflective after the light moves along.[153]

Surface texturing

[edit]

Incident light rays onto a textured surface do not reflect out to the air as opposed to rays onto a flat surface, but rather some light rays are bounced back onto the other surface again due to the geometry of the surface; increasing light absorption and light to electricity conversion efficiency. Surface texturing is one technique used to reduce optical losses, primarily in cost-effective, low light absorption thin-film solar cells. In combination with anti-reflective coating, surface texturing technique can effectively trap light rays within a thin film silicon solar cell. Consequently, at the same power output, thickness for solar cells can decrease with the increased absorption of light rays.

Surface texture geometry and texturing techniques can be done in multiple ways. Etching c-Si substrates can produce randomly distributed square based pyramids on the surface using anisotropic etchants.[154] Studies show that c-Si wafers could be etched down to form nano-scale inverted pyramids. In 2012, researchers at MIT reported that c-Si films textured with nanoscale inverted pyramids could achieve light absorption comparable to 30 times thicker planar c-Si.[155] While easier to manufacture, but with less efficiency, multicrystalline solar cells can be surface-textured through isotopic etching or photolithography methods to yield solar energy conversion efficiency comparable to that of monocrystalline silicon cells.[156][157]

This texture effect as well as the interaction with other interfaces in the PV module is a challenging optical simulation task, but at least one efficient method for modeling and optimization that exists is the OPTOS formalism.[158]

Encapsulation

[edit]Solar cells are commonly encapsulated in a transparent polymeric resin to protect the delicate solar cell regions for coming into contact with moisture, dirt, ice, and other environmental conditions expected during operation. Encapsulants are commonly made from polyvinyl acetate or glass. Most encapsulants are uniform in structure and composition, which increases light collection owing to light trapping from total internal reflection of light within the resin. Research has been conducted into structuring the encapsulant to provide further collection of light. Such encapsulants have included roughened glass surfaces,[159] diffractive elements,[160] prism arrays,[161] air prisms,[162] v-grooves,[163] diffuse elements, as well as multi-directional waveguide arrays.[164] Prism arrays show an overall 5% increase in the total solar energy conversion.[162] Arrays of vertically aligned broadband waveguides provide a 10% increase at normal incidence, as well as wide-angle collection enhancement of up to 4%,[165] with optimized structures yielding up to a 20% increase in short circuit current.[166] Active coatings that convert infrared light into visible light have shown a 30% increase.[167] Nanoparticle coatings inducing plasmonic light scattering increase wide-angle conversion efficiency up to 3%. Optical structures have also been created in encapsulation materials to effectively "cloak" the metallic front contacts.[168][169]

Manufacture

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2014) |

Solar cells share some processing and manufacturing techniques with other semiconductor devices and are commonly used in calculators, watches, and to power satellites in space.[170] However, the strict requirements for cleanliness and quality control of semiconductor fabrication are more relaxed for solar cells, lowering costs.

Polycrystalline silicon wafers are made by wire-sawing block-cast silicon ingots into 180 to 350 micrometer thick wafers. The wafers are usually lightly p-type-doped. A surface diffusion of n-type dopants is performed on the front side of the wafer. This forms a p–n junction a few hundred nanometers below the surface.

Anti-reflection coatings are then typically applied to increase the amount of light coupled into the solar cell. Silicon nitride has gradually replaced titanium dioxide as the preferred material, because of its excellent surface passivation qualities. It prevents carrier recombination at the cell surface. A layer several hundred nanometers thick is applied using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. Some solar cells have textured front surfaces that, like anti-reflection coatings, increase the amount of light reaching the wafer. Such surfaces were first applied to single-crystal silicon, followed by multicrystalline silicon somewhat later.

A full area metal contact is made on the back surface, and a grid-like metal contact made up of fine "fingers" and larger "bus bars" are screen-printed onto the front surface using a silver paste. This is an evolution of the so-called "wet" process for applying electrodes, first described in a US patent filed in 1981 by Bayer AG.[171] The rear contact is formed by screen-printing a metal paste. To maximize frontal surface area available for sunlight and improve solar cell efficiency, manufacturers use various rear contact electrode techniques:

- Passivated emitter rear contact (PERC) uses a solid aluminum rear contact surface and adds a polymer film to capture light[172]

- Tunnel oxide passivated contact (TOPCon) uses a grid pattern of increasingly smaller silver rear bus bars and adds an oxidation layer to the PERC film to capture more light[173][172][174]

- Interdigitated back contact (IBC)[175]

The paste is then fired at several hundred degrees Celsius to form metal electrodes in ohmic contact with the silicon. Some companies use an additional electroplating step to increase efficiency. After the metal contacts are made, the solar cells are interconnected by flat wires or metal ribbons, and assembled into modules or "solar panels". Solar panels have a sheet of tempered glass on the front, and a polymer or glass encapsulation on the back.

Different types of manufacturing and recycling partly determine how effective it is in decreasing emissions and having a positive environmental effect.[52] Such differences and effectiveness could be quantified[52] for production of the most optimal types of products for different purposes in different regions across time.

Manufacturers and certification

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2021) |

National Renewable Energy Laboratory tests and validates solar technologies. Three reliable groups certify solar equipment: UL and IEEE (both U.S. standards) and IEC[citation needed].

The IEA's 2022 Special Report highlights China's dominance over the solar PV supply chain, with an investment exceeding US$50 billion and the creation of around 300,000 jobs since 2011. China commands over 80% of all manufacturing stages for solar panels. This control has drastically cut costs but also led to issues like supply-demand imbalances and polysilicon production constraints. Nevertheless, China's strategic policies have reduced solar PV costs by more than 80%, increasing global affordability. In 2021, China's solar PV exports were over US$30 billion.[177]

Meeting global energy and climate targets necessitates a major expansion in solar PV manufacturing, aiming for over 630 GW by 2030 according to the IEA's "Roadmap to Net Zero Emissions by 2050". China's dominance, controlling nearly 95% of key solar PV components and 40% of the world's polysilicon production in Xinjiang, poses risks of supply shortages and cost surges. Critical mineral demand, like silver, may exceed 30% of 2020's global production by 2030.[177]

In 2021, China's share of solar PV module production reached approximately 70%, an increase from 50% in 2010. Other key producers included Vietnam (5%), Malaysia (4%), Korea (4%), and Thailand (2%), with much of their production capacity developed by Chinese companies aimed at exports, notably to the United States.[177]

China

[edit]As of September 2018, sixty percent of the world's solar photovoltaic modules were made in China.[178] As of May 2018, the largest photovoltaic plant in the world is located in the Tengger desert in China.[179] In 2018, China added more photovoltaic installed capacity (in GW) than the next 9 countries combined.[180] In 2021, China's share of solar PV module production reached approximately 70%.[177]

In the first half of 2023, China's production of PV modules exceeded 220 GW, marking an increase of over 62% compared to the same period in 2022. In 2022, China maintained its position as the world's largest PV module producer, holding a dominant market share of 77.8%.[181]

Vietnam

[edit]In 2022, Vietnam was the second-largest PV module producer, only behind China, with its production capacity rising to 24.1 GW, marking a significant 47% increase from the 16.4 GW produced in 2021. Vietnam accounts for 6.4% of the world's photovoltaic production.[181]

Malaysia

[edit]In 2022, Malaysia was the third-largest PV module producer, with a production capacity of 10.8 GW, accounting for 2.8% of global production. This placed it behind China, which dominated with 77.8%, and Vietnam, which contributed 6.4%.[181]

United States

[edit]Solar energy production in the U.S. doubled from 2013 to 2019.[182] This was driven first by the falling price of quality silicon,[183][184][185] and later simply by the globally plunging cost of photovoltaic modules.[179][186] In 2018, the U.S. added 10.8GW of installed solar photovoltaic energy, an increase of 21%.[180]

Latin America: Latin America has emerged as a promising region for solar energy development in recent years, with over 10 GW of installations in 2020. The solar market in Latin America has been driven by abundant solar resources, falling costs, competitive auctions and growing electricity demand. Some of the leading countries for solar energy in Latin America are Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Argentina. However, the solar market in Latin America also faces some challenges, such as political instability, financing gaps and power transmission bottlenecks.[187]

Middle East and Africa: The Middle East and Africa have also experienced significant growth in solar energy deployment in recent years, with over 8 GW installations in 2020. The solar market in the Middle East and Africa has been driven by the low-cost generation of solar energy, the diversification of energy sources, the fight against climate change and rural electrification are motivated. Some of the notable countries for solar energy in the Middle East and Africa are Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Morocco and South Africa. However, the solar market in the Middle East and Africa also faces several obstacles, including social unrest, regulatory uncertainty and technical barriers.[188]

Materials sourcing

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2021) |

Like many other energy generation technologies, the manufacture of solar cells, especially its rapid expansion, has many environmental and supply-chain implications. Global mining may adapt and potentially expand for sourcing the needed minerals which vary per type of solar cell.[189][190] Recycling solar panels could be a source for materials that would otherwise need to be mined.[52]

Disposal

[edit]Solar cells degrade over time and lose their efficiency. Solar cells in extreme climates, such as desert or polar, are more prone to degradation due to exposure to harsh UV light and snow loads respectively.[191] Usually, solar panels are given a lifespan of 25–30 years before decommissioning.[192]

The International Renewable Energy Agency estimated that the amount of solar panel electronic waste generated in 2016 was 43,500–250,000 metric tons. This number is estimated to increase substantially by 2030, reaching an estimated waste volume of 60–78 million metric tons in 2050.[193]

Recycling

[edit]The most widely used solar cells in the market are crystalline solar cells. A product is truly recyclable if it can be harvested again. In the 2016 Paris Agreement, 195 countries agreed to reduce their carbon emissions by shifting their focus away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy sources. Owing to this, Solar will be a major contributor to electricity generation all over the world. So, there will be a plethora of solar panels to be recycled after the end of their life cycle. In fact, many researchers around the globe have voiced their concern about finding ways to use silicon cells after recycling.[194][195][196][197]

Additionally, these cells have hazardous elements/compounds, including lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd) or cadmium sulfide (CdS), selenium (Se), and barium (Ba) as dopants aside from the valuables silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), silver (Ag), and copper (Cu). The harmful elements/compounds if not disposed of with the proper technique can have severe harmful effects on human life and wildlife alike.[198]

There are various ways c-Si can be recycled. Mainly thermal and chemical separation methods are used. This happens in two stages[199]

- PV solar cell separation: in thermal delamination, the ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) is removed and materials such as glass, Tedlar®, aluminium frame, steel, copper and plastics are separated;

- cleansing the surface of PV solar cells: unwanted layers (antireflection layer, metal coating and p–n semiconductor) are removed from the silicon solar cells separated from the PV modules; as a result, the silicon substrate, suitable for re-use, can be recovered.

The first solar panel recycling plant opened in Rousset, France in 2018. It was set to recycle 1300 tonnes of solar panel waste a year, and can increase its capacity to 4000 tonnes.[200][201][202] If recycling is driven only by market-based prices, rather than also environmental regulations, the economic incentives for recycling remain uncertain and as of 2021 the environmental impact of different types of developed recycling techniques still need to be quantified.[52]

See also

[edit]- Anomalous photovoltaic effect

- Autonomous building

- Black silicon

- Electromotive force (solar cell)

- Energy development

- Flexible substrate

- Green technology

- Hot spot (photovoltaics)

- Inkjet solar cell

- List of solar engines

- List of types of solar cells

- Metallurgical grade silicon

- Microgeneration

- Nanoflake

- Photovoltaics

- Plasmonic solar cell

- Printed electronics

- Roll-to-roll processing

- Shockley-Queisser limit

- Solar cell research

- Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells (journal)

- Solar module quality assurance

- Solar roof

- Solar shingles

- Solar tracker

- Spectrophotometry

- Standardization#Environmental protection

- Sustainable development

- Theory of solar cells

- Thermophotovoltaics

- Variable renewable energy

References

[edit]- ^ Solar Cells. chemistryexplained.com

- ^ Special Report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains (PDF). International Energy Agency. August 2022.

- ^ "Solar cells – performance and →use". solarbotic s.net.

- ^ Al-Ezzi, Athil S.; Ansari, Mohamed Nainar M. (8 July 2022). "Photovoltaic Solar Cells: A Review". Applied System Innovation. 5 (4): 67. doi:10.3390/asi5040067. ISSN 2571-5577.

- ^ Messenger, Roger A.; Ventre, Jerry (2010). Photovoltaic Systems Engineering. CRC Press. pp. 455–460.

- ^ Arulious, Jora A; Earlina, D; Harish, D; Sakthi Priya, P; Inba Rexy, A; Nancy Mary, J S (1 November 2021). "Design of solar powered electric vehicle". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2070 (1) 012105. Bibcode:2021JPhCS2070a2105A. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2070/1/012105. ISSN 1742-6588.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (14 May 2021). "Electric Vehicle Myths". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 31 May 2025.

- ^ "Recent Advances in Solar Cell Technology and Future Aspects in India" (PDF). International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development. January 2024.

- ^ Connors, John (21–23 May 2007). "On the Subject of Solar Vehicles and the Benefits of the Technology". 2007 International Conference on Clean Electrical Power. Capri, Italy. pp. 700–705. doi:10.1109/ICCEP.2007.384287.

- ^ Özkalay, Ebrar; Valoti, Flavio; Caccivio, Mauro; Virtuani, Alessandro; Friesen, Gabi; Ballif, Christophe (2024). "The effect of partial shading on the reliability of photovoltaic modules in the built-environment". EPJ Photovoltaics. 15: 7. Bibcode:2024EPJPv..15....7O. doi:10.1051/epjpv/2024001. ISSN 2105-0716.

- ^ "Shading losses in PV systems, and techniques to mitigate them". aurora. 17 October 2023. Retrieved 28 March 2025.

- ^ "Shading". PVEducation. Retrieved 28 March 2025.

- ^ "Technology Roadmap: Solar Photovoltaic Energy" (PDF). IEA. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ "Photovoltaic System Pricing Trends – Historical, Recent, and Near-Term Projections, 2014 Edition" (PDF). NREL. 22 September 2014. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Documenting a Decade of Cost Declines for PV Systems". National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Garcia, Mark (31 July 2017). "International Space Station Solar Arrays". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ David, Leonard (4 October 2021). "Air Force's X-37B robotic space plane wings past 500 days in Earth orbit". LiveScience. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ David, Leonard (3 November 2021). "Space solar power's time may finally be coming". Space.com. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Marques Lameirinhas, Ricardo A.; N. Torres, João Paulo; de Melo Cunha, João P. (2022). "A photovoltaic technology review: history, fundamentals and applications". Energies. 15 (5): 1823. doi:10.3390/en15051823.

- ^ Gevorkian, Peter (2007). Sustainable energy systems engineering: the complete green building design resource. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-147359-0.

- ^ "Julius (Johann Phillipp Ludwig) Elster: 1854 - 1920". Adventures in Cybersound. Archived from the original on 8 March 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1921: Albert Einstein", Nobel Prize official page

- ^ Lashkaryov, V. E. (2008). "Investigation of a barrier layer by the thermoprobe method" (PDF). Ukr. J. Phys. 53 (Special Issue): 53–56. ISSN 2071-0194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2015. Translated and reprinted from Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR, Ser. Fiz. 5, No. 4–5, pp. 442–446 (1941)

- ^ "Light sensitive device" U.S. patent 2,402,662 Issue date: June 1946

- ^ Lehovec, K. (15 August 1948). "The Photo-Voltaic Effect". Physical Review. 74 (4): 463–471. Bibcode:1948PhRv...74..463L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.74.463.

- ^ Lau, W.S. (October 2017). "Introduction to the World of Semiconductors". ULSI Front-End Technology: Covering from the First Semiconductor Paper to CMOS FINFET Technology. p. 7. doi:10.1142/10495. ISBN 978-981-322-215-1.

- ^ "April 25, 1954: Bell Labs Demonstrates the First Practical Silicon Solar Cell". APS News. 18 (4). American Physical Society. April 2009.

- ^ Tsokos, K. A. (28 January 2010). Physics for the IB Diploma Full Colour. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-13821-5.

- ^ "NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1958-002B". NASA. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ Perlin 1999, p. 50.

- ^ a b Perlin 1999, p. 53.

- ^ a b Williams, Neville (2005). Chasing the Sun: Solar Adventures Around the World. New Society Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-55092-312-4.

- ^ Jones, Geoffrey; Bouamane, Loubna (2012). "Power from Sunshine": A Business History of Solar Energy (PDF). Harvard Business School. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Perlin 1999, p. 54.

- ^ The National Science Foundation: A Brief History, Chapter IV, NSF 88-16, 15 July 1994 (retrieved 20 June 2015)

- ^ Herwig, Lloyd O. (1999). "Cherry Hill revisited: Background events and photovoltaic technology status". National center for photovoltaics (NCPV) 15th program review meeting. Vol. 462. p. 785. Bibcode:1999AIPC..462..785H. doi:10.1063/1.58015.

- ^ Deyo, J. N.; Brandhorst, H. W. Jr.; Forestieri, A. F. (15–18 November 1976). Status of the ERDA/NASA photovoltaic tests and applications project. 12th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conf.

- ^ "The multinational connections-who does what where". New Scientist. Vol. 84, no. 1177. Reed Business Information. 18 October 1979. ISSN 0262-4079.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Solar (photovoltaic) panel prices vs. cumulative capacity". OurWorldInData.org. 2024. Archived from the original on 24 January 2025. OWID credits source data to: Nemet (2009); Farmer & Lafond (2016); International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA, 2024).

- ^ Yu, Peng; Wu, Jiang; Liu, Shenting; Xiong, Jie; Jagadish, Chennupati; Wang, Zhiming M. (1 December 2016). "Design and fabrication of silicon nanowires towards efficient solar cells" (PDF). Nano Today. 11 (6): 704–737. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2016.10.001.

- ^ "U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System Cost Benchmark: Q1 2018" (PDF) (pdf). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). p. 26. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Solar Photovoltaic System and Energy Storage Cost Benchmark: Q1 2020" (PDF) (pdf). National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). p. 28. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "Sunny Uplands: Alternative energy will no longer be alternative". The Economist. 21 November 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ "From M0 to M12 - different wafer sizes in the market". IBC SOLAR Blog. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Bhambhani, Anu (25 June 2020). "Group Proposes M10 As New Silicon Wafer Standard Size". TaiyangNews - All About Solar Power. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Solar Stocks: Does the Punishment Fit the Crime?. 24/7 Wall St. (6 October 2011). Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Parkinson, Giles (7 March 2013). "Plunging Cost of Solar PV (Graphs)". Clean Technica. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ Mann, Sander A.; de Wild-Scholten, Mariska J.; Fthenakis, Vasilis M.; van Sark, Wilfried G.J.H.M.; Sinke, Wim C. (1 November 2014). "The energy payback time of advanced crystalline silicon PV modules in 2020: a prospective study". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 22 (11): 1180–1194. doi:10.1002/pip.2363. hdl:1874/306424. ISSN 1099-159X. S2CID 97151576.

- ^ "Snapshot of Global PV 1992–2014" (PDF). International Energy Agency – Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme. 30 March 2015. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015.

- ^ Jaeger, Joel (20 September 2021). "Explaining the Exponential Growth of Renewable Energy". Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "Solar energy – Renewable energy – Statistical Review of World Energy – Energy economics – BP". bp.com. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Solar panels are a pain to recycle. These companies are trying to fix that". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ "BP Global – Reports and publications – Going for grid parity". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2012.. Bp.com. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ BP Global – Reports and publications – Gaining on the grid. Bp.com. August 2007.

- ^ The Path to Grid Parity. bp.com

- ^ Peacock, Matt (20 June 2012) Solar industry celebrates grid parity, ABC News.

- ^ Baldwin, Sam (20 April 2011) Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy: Challenges and Opportunities. Clean Energy SuperCluster Expo Colorado State University. U.S. Department of Energy.

- ^ "Small Chinese Solar Manufacturers Decimated in 2012". ENF Solar Trade Platform and Directory of Solar Companies. ENF Ltd. 8 January 2013. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ^ "What is a solar panel and how does it work?". Energuide.be. Sibelga. Retrieved 3 January 2017.