Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electrical grid

View on Wikipedia

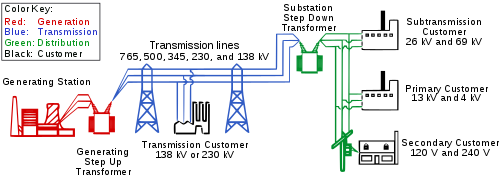

An electrical grid (or electricity network) is an interconnected network for electricity delivery from producers to consumers. Electrical grids consist of power stations, electrical substations to step voltage up or down, electric power transmission to carry power over long distances, and finally electric power distribution to customers. In that last step, voltage is stepped down again to the required service voltage. Power stations are typically built close to energy sources and far from densely populated areas. Electrical grids vary in size and can cover whole countries or continents. From small to large there are microgrids, wide area synchronous grids, and super grids. The combined transmission and distribution network is part of electricity delivery, known as the power grid.

Grids are nearly always synchronous, meaning all distribution areas operate with three phase alternating current (AC) frequencies synchronized (so that voltage swings occur at almost the same time). This allows transmission of AC power throughout the area, connecting the electricity generators with consumers. Grids can enable more efficient electricity markets.

Although electrical grids are widespread, as of 2016[update], 1.4 billion people worldwide were not connected to an electricity grid.[1] As electrification increases, the number of people with access to grid electricity is growing. About 840 million people (mostly in Africa), which is ca. 11% of the World's population, had no access to grid electricity in 2017, down from 1.2 billion in 2010.[2]

Electrical grids can be prone to malicious intrusion or attack; thus, there is a need for electric grid security. Also as electric grids modernize and introduce computer technology, cyber threats start to become a security risk.[3] Particular concerns relate to the more complex computer systems needed to manage grids.[4]

Types (grouped by size)

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Power engineering |

|---|

| Electric power conversion |

| Electric power infrastructure |

| Electric power systems components |

Microgrid

[edit]A microgrid is a local grid that is usually part of the regional wide-area synchronous grid, but which can disconnect and operate autonomously.[5] It might do this in times when the main grid is affected by outages. This is known as islanding, and it might run indefinitely on its own resources.

Compared to larger grids, microgrids typically use a lower voltage distribution network and distributed generators.[6] Microgrids may not only be more resilient, but may be cheaper to implement in isolated areas.

A design goal is that a local area produces all of the energy it uses.[5]

Example implementations include:

- Hajjah and Lahj, Yemen: community-owned solar microgrids.[7]

- Île d'Yeu pilot program: sixty-four solar panels with a peak capacity of 23.7 kW on five houses and a battery with a storage capacity of 15 kWh.[8][9]

- Les Anglais, Haiti:[10] includes energy theft detection.[11]

- Mpeketoni, Kenya: a community-based diesel-powered micro-grid system.[12]

- Stone Edge Farm Winery: micro-turbine, fuel-cell, multiple battery, hydrogen electrolyzer, and PV enabled winery in Sonoma, California.[13][14]

Wide area synchronous grid

[edit]A wide area synchronous grid (also called an "interconnection" in North America) is an electrical grid at a regional scale or greater that operates at a synchronized frequency and is electrically tied together during normal system conditions. For example, there are four major interconnections in North America (the Western Interconnection, the Eastern Interconnection, the Quebec Interconnection and the Texas Interconnection). In Europe, one large grid connects most of Western Europe. These are also known as synchronous zones, the largest of which is the synchronous grid of Continental Europe (ENTSO-E) with 667 gigawatts (GW) of generation, and the widest region served being that of the IPS/UPS system serving countries of the former Soviet Union. Synchronous grids with ample capacity facilitate electricity market trading across wide areas. In the ENTSO-E in 2008, over 350,000 megawatt hours were sold per day on the European Energy Exchange (EEX).[15]

Each of the interconnects in North America are run at a nominal 60 Hz, while those of Europe run at 50 Hz. Neighbouring interconnections with the same frequency and standards can be synchronized and directly connected to form a larger interconnection, or they may share power without synchronization via high-voltage direct current power transmission lines (DC ties), or with variable-frequency transformers (VFTs), which permit a controlled flow of energy while also functionally isolating the independent AC frequencies of each side.

The benefits of synchronous zones include pooling of generation, resulting in lower generation costs; pooling of load, resulting in significant equalizing effects; common provisioning of reserves, resulting in cheaper primary and secondary reserve power costs; opening of the market, resulting in possibility of long-term contracts and short term power exchanges; and mutual assistance in the event of disturbances.[16]

One disadvantage of a wide-area synchronous grid is that problems in one part can have repercussions across the whole grid. For example, in 2018, Kosovo used more power than it generated due to a dispute with Serbia, leading to the phase across the whole synchronous grid of Continental Europe lagging behind what it should have been. The frequency dropped to 49.996 Hz. This caused certain kinds of clocks to become six minutes slow.[17]

-

The synchronous grids of Europe

-

The two major and three minor interconnections of North America

-

Major WASGs around the world

Super grid

[edit]

A super grid or supergrid is a wide-area transmission network that is intended to make possible the trade of high volumes of electricity across great distances. It is sometimes also referred to as a mega grid. Super grids can support a global energy transition by smoothing local fluctuations of wind energy and solar energy. In this context, they are considered as a key technology to mitigate global warming. Super grids typically use high-voltage direct current (HVDC) to transmit electricity long distances. The latest generation of HVDC power lines can transmit energy with losses of only 1.6% per 1000 km.[19]

Electric utilities between regions are many times interconnected for improved economy and reliability. Electrical interconnectors allow for economies of scale, allowing energy to be purchased from large, efficient sources. Utilities can draw power from generator reserves from a different region to ensure continuing, reliable power and diversify their loads. Interconnection also allows regions to have access to cheap bulk energy by receiving power from different sources. For example, one region may be producing cheap hydro power during high water seasons, but in low water seasons, another area may be producing cheaper power through wind, allowing both regions to access cheaper energy sources from one another during different times of the year. Neighboring utilities also help others to maintain the overall system frequency and also help manage tie transfers between utility regions.[20]

Electricity Interconnection Level (EIL) of a grid is the ratio of the total interconnector power to the grid divided by the installed production capacity of the grid. Within the EU, it has set a target of national grids reaching 10% by 2020, and 15% by 2030.[21]

Components

[edit]Generation

[edit]

Electricity generation is the process of generating electric power at power stations. This is done ultimately from sources of primary energy typically with electromechanical generators driven by heat engines from fossil, nuclear, and geothermal sources, or driven by the kinetic energy of water or wind. Other power sources are photovoltaics driven by solar insolation, and grid batteries.[nb 1]

The sum of the power outputs of generators on the grid is the production of the grid, typically measured in gigawatts (GW).

Transmission

[edit]

Electric power transmission is the bulk movement of electrical energy from a generating site, via a web of interconnected lines, to an electrical substation, from which is connected to the distribution system. This networked system of connections is distinct from the local wiring between high-voltage substations and customers. Transmission networks are built with redundant pathways to prevent a single point of failure. In case of line failures this redundancy allows power to be simply rerouted while repairs are done.

Because the power is often generated far from where it is consumed, the transmission system can cover great distances. For a given amount of power, transmission efficiency is greater at higher voltages and lower currents. Therefore, voltages are stepped up at the generating station, and stepped down at local substations for distribution to customers.

Most transmission is three-phase. Three-phase, compared to single-phase, can deliver much more power for a given amount of wire, since the neutral and ground wires are shared.[23] Further, three-phase generators and motors are more efficient than their single-phase counterparts.

However, for conventional conductors one of the main losses are resistive losses which are a square law on current, and depend on distance. High voltage AC transmission lines can lose 1–4% per hundred miles.[24] However, high-voltage direct current can have half the losses of AC. Over very long distances, these efficiencies can offset the additional cost of the required AC/DC converter stations at each end.

Substations

[edit]Substations may perform many different functions but usually transform voltage from low to high (step up) and from high to low (step down). Between the generator and the final consumer, the voltage may be transformed several times.[25]

The three main types of substations, by function, are:[26]

- Step-up substation: these use transformers to raise the voltage coming from the generators and power plants so that power can be transmitted long distances more efficiently, with smaller currents.

- Step-down substation: these transformers lower the voltage coming from the transmission lines which can be used in industry or sent to a distribution substation.

- Distribution substation: these transform the voltage lower again for the distribution to end users.

Aside from transformers, other major components or functions of substations include:

- Circuit breakers: used to automatically break a circuit and isolate a fault in the system.[27]

- Switches: to control the flow of electricity, and isolate equipment.[28]

- The substation busbar: typically a set of three conductors, one for each phase of current. The substation is organized around the buses, and they are connected to incoming lines, transformers, protection equipment, switches, and the outgoing lines.[27]

- Lightning arresters

- Capacitors for power factor correction

- Synchronous condensers for power factor correction and grid stability

Electric power distribution

[edit]

Distribution is the final stage in the delivery of power; it carries electricity from the transmission system to individual consumers. Substations connect to the transmission system and lower the transmission voltage to medium voltage ranging between 2 kV and 35 kV. But the voltage levels varies very much between different countries, in Sweden medium voltage are normally 10 kV between 20 kV.[29] Primary distribution lines carry this medium voltage power to distribution transformers located near the customer's premises. Distribution transformers again lower the voltage to the utilization voltage. Customers demanding a much larger amount of power may be connected directly to the primary distribution level or the subtransmission level.[30]

Distribution networks are divided into two types, radial or network.[31]

In cities and towns of North America, the grid tends to follow the classic radially fed design. A substation receives its power from the transmission network, the power is stepped down with a transformer and sent to a bus from which feeders fan out in all directions across the countryside. These feeders carry three-phase power, and tend to follow the major streets near the substation. As the distance from the substation grows, the fanout continues as smaller laterals spread out to cover areas missed by the feeders. This tree-like structure grows outward from the substation, but for reliability reasons, usually contains at least one unused backup connection to a nearby substation. This connection can be enabled in case of an emergency, so that a portion of a substation's service territory can be alternatively fed by another substation.

Storage

[edit]

Grid energy storage (also called large-scale energy storage) is a collection of methods used for energy storage on a large scale within an electrical power grid. Electrical energy is stored during times when electricity is plentiful and inexpensive (especially from intermittent power sources such as renewable electricity from wind power, tidal power and solar power) or when demand is low, and later power is generated when demand is high, and electricity prices tend to be higher.

As of 2020[update], the largest form of grid energy storage is dammed hydroelectricity, with both conventional hydroelectric generation as well as pumped storage hydroelectricity.

Developments in battery storage have enabled commercially viable projects to store energy during peak production and release during peak demand, and for use when production unexpectedly falls giving time for slower responding resources to be brought online.

Two alternatives to grid storage are the use of peaking power plants to fill in supply gaps and demand response to shift load to other times.

Functionalities

[edit]Demand

[edit]The demand, or load on an electrical grid is the total electrical power being removed by the users of the grid.

The graph of the demand over time is called the demand curve.

Baseload is the minimum load on the grid over any given period, peak demand is the maximum load. Historically, baseload was commonly met by equipment that was relatively cheap to run, that ran continuously for weeks or months at a time, but globally this is becoming less common. The extra peak demand requirements are sometimes produced by expensive peaking plants that are generators optimised to come on-line quickly but these too are becoming less common.[clarification needed]

However, if the demand of electricity exceeds the capacity of a local power grid, it will cause safety issues like burning out.[32]

Voltage

[edit]Grids are designed to supply electricity to their customers at largely constant voltages. This has to be achieved with varying demand, variable reactive loads, and even nonlinear loads, with electricity provided by generators and distribution and transmission equipment that are not perfectly reliable.[33] Often grids use tap changers on transformers near to the consumers to adjust the voltage and keep it within specification.

Frequency

[edit]In a synchronous grid all the generators must run at the same frequency, and must stay very nearly in phase with each other and the grid. Generation and consumption must be balanced across the entire grid, because energy is consumed as it is produced. For rotating generators, a local governor regulates the driving torque, maintaining almost constant rotation speed as loading changes. Energy is stored in the immediate short term by the rotational kinetic energy of the generators.

Although the speed is kept largely constant, small deviations from the nominal system frequency are very important in regulating individual generators and are used as a way of assessing the equilibrium of the grid as a whole. When the grid is lightly loaded the grid frequency runs above the nominal frequency, and this is taken as an indication by Automatic Generation Control (AGC) systems across the network that generators should reduce their output. Conversely, when the grid is heavily loaded, the frequency naturally slows, and governors adjust their generators so that more power is output (droop speed control). When generators have identical droop speed control settings it ensures that multiple parallel generators with the same settings share load in proportion to their rating.

In addition, there's often central control, which can change the parameters of the AGC systems over timescales of a minute or longer to further adjust the regional network flows and the operating frequency of the grid.

For timekeeping purposes, the nominal frequency will be allowed to vary in the short term, but is adjusted to prevent line-operated clocks from gaining or losing significant time over the course of a whole 24 hour period.

Neighbouring grids that aren't directly connected are almost always out-of-phase with each other. Instead, high-voltage direct current lines or variable-frequency transformers are used, which allow two out-of-phase synchronous grids to share power.

Capacity and firm capacity

[edit]The sum of the maximum power outputs (nameplate capacity) of the generators attached to an electrical grid might be considered to be the capacity of the grid.

However, in practice, they are never run flat out simultaneously. Typically, some generators are kept running at lower output powers (spinning reserve) to deal with failures as well as variation in demand. In addition generators can be off-line for maintenance or other reasons, such as availability of energy inputs (fuel, water, wind, sun etc.) or pollution constraints.

Firm capacity is the maximum power output on a grid that is immediately available over a given time period, and is a far more useful figure.

Production

[edit]Most grid codes specify that the load is shared between the generators in merit order according to their marginal cost (i.e. cheapest first) and sometimes their environmental impact. Thus cheap electricity providers tend to be run flat out almost all the time, and the more expensive producers are only run when necessary.

Failures and issues

[edit]Failures are usually associated with generators or power transmission lines tripping circuit breakers due to faults leading to a loss of generation capacity for customers, or excess demand. This will often cause the frequency to reduce, and the remaining generators will react and together attempt to stabilize above the minimum. If that is not possible then a number of scenarios can occur.

A large failure in one part of the grid — unless quickly compensated for — can cause current to re-route itself to flow from the remaining generators to consumers over transmission lines of insufficient capacity, causing further failures. One downside to a widely connected grid is thus the possibility of cascading failure and widespread power outage. A central authority is usually designated to facilitate communication and develop protocols to maintain a stable grid. For example, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation gained binding powers in the United States in 2006, and has advisory powers in the applicable parts of Canada and Mexico. The U.S. government has also designated National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors, where it believes transmission bottlenecks have developed.

Brownout

[edit]

A brownout is an intentional or unintentional drop in voltage in an electrical power supply system. Intentional brownouts are used for load reduction in an emergency.[34] The reduction lasts for minutes or hours, as opposed to short-term voltage sag (or dip). The term brownout comes from the dimming experienced by incandescent lighting when the voltage sags. A voltage reduction may be an effect of disruption of an electrical grid, or may occasionally be imposed in an effort to reduce load and prevent a power outage, known as a blackout.[35]

Blackout

[edit]A power outage (also called a power cut, a power out, a power blackout, power failure or a blackout) is a loss of the electric power to a particular area.

Power failures can be caused by faults at power stations, damage to electric transmission lines, substations or other parts of the distribution system, a short circuit, cascading failure, fuse or circuit breaker operation, and human error.

Power failures are particularly critical at sites where the environment and public safety are at risk. Institutions such as hospitals, sewage treatment plants, mines, shelters and the like will usually have backup power sources such as standby generators, which will automatically start up when electrical power is lost. Other critical systems, such as telecommunication, are also required to have emergency power. The battery room of a telephone exchange usually has arrays of lead–acid batteries for backup and also a socket for connecting a generator during extended periods of outage.

Load shedding

[edit]Electrical generation and transmission systems may not always meet peak demand requirements— the greatest amount of electricity required by all utility customers within a given region. In these situations, overall demand must be lowered, either by turning off service to some devices or cutting back the supply voltage (brownouts), in order to prevent uncontrolled service disruptions such as power outages (widespread blackouts) or equipment damage. Utilities may impose load shedding on service areas via targeted blackouts, rolling blackouts or by agreements with specific high-use industrial consumers to turn off equipment at times of system-wide peak demand.

Black start

[edit]

A black start is the process of restoring an electric power station or a part of an electric grid to operation without relying on the external electric power transmission network to recover from a total or partial shutdown.[36]

Normally, the electric power used within the plant is provided from the station's own generators. If all of the plant's main generators are shut down, station service power is provided by drawing power from the grid through the plant's transmission line. However, during a wide-area outage, off-site power from the grid is not available. In the absence of grid power, a so-called black start needs to be performed to bootstrap the power grid into operation.

To provide a black start, some power stations have small diesel generators, normally called the black start diesel generator (BSDG), which can be used to start larger generators (of several megawatts capacity), which in turn can be used to start the main power station generators. Generating plants using steam turbines require station service power of up to 10% of their capacity for boiler feedwater pumps, boiler forced-draft combustion air blowers, and for fuel preparation. It is uneconomical to provide such a large standby capacity at each station, so black-start power must be provided over designated tie lines from another station. Often hydroelectric power plants are designated as the black-start sources to restore network interconnections. A hydroelectric station needs very little initial power to start (just enough to open the intake gates and provide excitation current to the generator field coils), and can put a large block of power on line very quickly to allow start-up of fossil-fuel or nuclear stations. Certain types of combustion turbine can be configured for black start, providing another option in places without suitable hydroelectric plants.[37] In 2017 a utility in Southern California has successfully demonstrated the use of a battery energy storage system to provide a black start, firing up a combined cycle gas turbine from an idle state.[38]

Obsolescence

[edit]Despite novel institutional arrangements and network designs, power delivery infrastructures is experiencing aging across the developed world. Contributing factors include:

- Aging equipment – older equipment has higher failure rates, leading to customer interruption rates affecting the economy and society; also, older assets and facilities lead to higher inspection maintenance costs and further repair and restoration costs.

- Obsolete system layout – older areas require serious additional substation sites and rights-of-way that cannot be obtained in the current area and are forced to use existing, insufficient facilities.

- Outdated engineering – traditional tools for power delivery planning and engineering are ineffective in addressing current problems of aged equipment, obsolete system layouts, and modern deregulated loading levels.

- Old cultural value – planning, engineering, operating of system using concepts and procedures that worked in vertically integrated industry exacerbate the problem under a deregulated industry.[39]

Trends

[edit]Demand response

[edit]Demand response is a grid management technique where retail or wholesale customers are requested or incentivised either electronically or manually to reduce their load. Currently, transmission grid operators use demand response to request load reduction from major energy users such as industrial plants.[40] Technologies such as smart metering can encourage customers to use power when electricity is plentiful by allowing for variable pricing.

Smart grid

[edit]

The smart grid is an enhancement of the 20th century electrical grid, using two-way communications and distributed so-called intelligent devices.[41] Two-way flows of electricity and information could improve the delivery network. Research is mainly focused on three systems of a smart grid – the infrastructure system, the management system, and the protection system.[42] Electronic power conditioning and control of the production and distribution of electricity are important aspects of the smart grid.[43]

The smart grid represents the full suite of current and proposed responses to the challenges of electricity supply. Numerous contributions to the overall improvement of energy infrastructure efficiency are anticipated from the deployment of smart grid technology, in particular including demand-side management. The improved flexibility of the smart grid permits greater penetration of highly variable renewable energy sources such as solar power and wind power, even without the addition of energy storage. Smart grids could also monitor/control residential devices that are noncritical during periods of peak power consumption, and return their function during nonpeak hours.[44]

A smart grid includes a variety of operation and energy measures:

- Advanced metering infrastructure (of which smart meters are a generic name for any utility side device even if it is more capable e.g. a fiber optic router)

- Smart distribution boards and circuit breakers integrated with home control and demand response (behind the meter from a utility perspective)

- Load control switches and smart appliances, often financed by efficiency gains on municipal programs (e.g. PACE financing)

- Renewable energy resources, including the capacity to charge parked (electric vehicle) batteries or larger arrays of batteries recycled from these, or other energy storage.

- Energy efficient resources

- Electric surplus distribution by power lines and auto-smart switch

- Sufficient utility grade fiber broadband to connect and monitor the above, with wireless as a backup. Sufficient spare if "dark" capacity to ensure failover, often leased for revenue.[45][46]

Concerns with smart grid technology mostly focus on smart meters, items enabled by them, and general security issues. Roll-out of smart grid technology also implies a fundamental re-engineering of the electricity services industry, although typical usage of the term is focused on the technical infrastructure.[47]

Smart grid policy is organized in Europe as Smart Grid European Technology Platform.[48] Policy in the United States is described in Title 42 of the United States Code.[49]Grid defection

[edit]Resistance to distributed generation among grid operators may encourage providers to leave the grid and instead distribute power to smaller geographies.[50][51][52]

The Rocky Mountain Institute[53] and other studies[54] foresee widescale grid defection. However, grid defection may be less likely in places such as Germany that have greater power demands in the winter.[55]

History

[edit]Early electric energy was produced near the device or service requiring that energy. In the 1880s, electricity competed with steam, hydraulics, and especially coal gas. Coal gas was first produced on customer's premises but later evolved into gasification plants that enjoyed economies of scale. In the industrialized world, cities had networks of piped gas, used for lighting. But gas lamps produced poor light, wasted heat, made rooms hot and smoky, and gave off hydrogen and carbon monoxide. They also posed a fire hazard. In the 1880s electric lighting soon became advantageous compared to gas lighting.

Electric utility companies established central stations to take advantage of economies of scale and moved to centralized power generation, distribution, and system management.[56] After the war of the currents was settled in favor of AC power, with long-distance power transmission it became possible to interconnect stations to balance the loads and improve load factors. Historically, transmission and distribution lines were owned by the same company, but starting in the 1990s, many countries have liberalized the regulation of the electricity market in ways that have led to the separation of the electricity transmission business from the distribution business.[57]

In the United Kingdom, Charles Merz, of the Merz & McLellan consulting partnership, built the Neptune Bank Power Station near Newcastle upon Tyne in 1901,[58] and by 1912 had developed into the largest integrated power system in Europe.[59] Merz was appointed head of a parliamentary committee and his findings led to the Williamson Report of 1918, which in turn created the Electricity (Supply) Act 1919. The bill was the first step towards an integrated electricity system. In 1925 the Weir Committee recommended the creation of a "national gridiron" and so the Electricity (Supply) Act 1926 created the Central Electricity Board (CEB).[60] The CEB standardized the nation's electricity supply and established the first synchronized AC grid, running at 132 kilovolts and 50 hertz but initially operated as regional grids. After brief overnight interconnection in 1937 they permanently and officially joined in 1938 becoming the UK National Grid.

In France, electrification began in the 1900s, with 700 communes in 1919, and 36,528 in 1938. At the same time, these close networks began to interconnect: Paris in 1907 at 12 kV, the Pyrénées in 1923 at 150 kV, and finally almost all of the country interconnected by 1938 at 220 kV. In 1946, the grid was the world's most dense. That year the state nationalised the industry, by uniting the private companies as Électricité de France. The frequency was standardised at 50 Hz, and the 225 kV network replaced 110 kV and 120 kV. Since 1956, service voltage has been standardised at 220/380 V, replacing the previous 127/220 V. During the 1970s, the 400 kV network, the new European standard, was implemented. Starting on May 29, 1986, the end user service voltage will progressively change to 230/400 V +/-10%.[61][62]

In the United States in the 1920s, utilities formed joint-operations to share peak load coverage and backup power. In 1934, with the passage of the Public Utility Holding Company Act (USA), electric utilities were recognized as public goods of importance and were given outlined restrictions and regulatory oversight of their operations. The Energy Policy Act of 1992 required transmission line owners to allow electric generation companies open access to their network[56][63] and led to a restructuring of how the electric industry operated in an effort to create competition in power generation. No longer were electric utilities built as vertical monopolies, where generation, transmission and distribution were handled by a single company. Now, the three stages could be split among various companies, in an effort to provide fair access to high voltage transmission.[20][21] The Energy Policy Act of 2005 allowed incentives and loan guarantees for alternative energy production and advance innovative technologies that avoided greenhouse emissions.

In China, electrification began in the 1950s.[64] In August 1961, the electrification of the Baoji-Fengzhou section of the Baocheng Railway was completed and delivered for operation, becoming China's first electrified railway.[65] From 1958 to 1998, China's electrified railway reached 6,200 miles (10,000 kilometres).[66] As of the end of 2017, this number has reached 54,000 miles (87,000 kilometres).[67] In the current railway electrification system of China, State Grid Corporation of China—Archived 2021-12-21 at the Wayback Machine—is an important power supplier. In 2019, it completed the power supply project of China's important electrified railways in its operating areas, such as Jingtong Railway, Haoji Railway, Zhengzhou–Wanzhou high-speed railway, et cetera, providing power supply guarantee for 110 traction stations, and its cumulative power line construction length reached 6,586 kilometres.[68]

See also

[edit]- Dispatchable generation

- Grid code: a specification for grid-connected equipment

- Inertial response

- North American power transmission grid

- Sustainable energy

Notes

[edit]- ^ Note that grid batteries are a useful source of power for grids, but not of primary energy and so they must be charged by another source of energy prior to use.

References

[edit]- ^ Overland, Indra (1 April 2016). "Energy: The missing link in globalization". Energy Research & Social Science. 14: 122–130. Bibcode:2016ERSS...14..122O. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.01.009. hdl:11250/2442076. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018.

[...] if all countries in the world were to make do with their own resources, there would be even more energy poverty in the world than there is now. Currently, 1.4 billion people are not connected to an electricity grid [...]

- ^ Odarno, Lily (2019-08-14). "Closing Sub-Saharan Africa's Electricity Access Gap: Why Cities Must Be Part of the Solution". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Douris, Constance. "As Cyber Threats To The Electric Grid Rise, Utilities And Regulators Seek Solutions". Forbes. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Overland, Indra (1 March 2019). "The geopolitics of renewable energy: Debunking four emerging myths". Energy Research & Social Science. 49: 36–40. Bibcode:2019ERSS...49...36O. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.018. hdl:11250/2579292. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ a b "How Microgrids Work". Energy.gov. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Khaitan, Siddhartha Kumar; Venkatraman, Ramakrishnan. "A Survey of Techniques for Designing and Managing Microgrids". Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "UNDP Yemen wins acclaimed international Ashden Awards for Humanitarian Energy". Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- ^ Spaes, Joel (3 July 2020). "Harmon'Yeu, première communauté énergétique à l'Île d'Yeu, signée Engie". www.pv-magazine.fr. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Wakim, Nabil (16 December 2020). "A L'Île-d'Yeu, soleil pour tous… ou presque". www.lemonde.fr. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Buevich, Maxim; Schnitzer, Dan; Escalada, Tristan; Jacquiau-Chamski, Arthur; Rowe, Anthony (2014). "Fine-grained remote monitoring, control and pre-paid electrical service in rural microgrids". IPSN-14 Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Information Processing in Sensor Networks. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1109/IPSN.2014.6846736. ISBN 978-1-4799-3146-0. S2CID 8593041.

- ^ Buevich, Maxim; Zhang, Xiao; Schnitzer, Dan; Escalada, Tristan; Jacquiau-Chamski, Arthur; Thacker, Jon; Rowe, Anthony (1 January 2015). "Short Paper: Microgrid Losses". Proceedings of the 2nd ACM International Conference on Embedded Systems for Energy-Efficient Built Environments. BuildSys '15. pp. 95–98. doi:10.1145/2821650.2821676. ISBN 9781450339810. S2CID 2742485.

- ^ Kirubi, et al. "Community-Based Electric Micro-Grids Can Contribute to Rural Development: Evidence from Kenya." World Development, vol. 37, no. 7, 2009, pp. 1208–1221.

- ^ "Microgrid at Stone Edge Farm Wins California Environmental Honor". Microgrid Knowledge. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Stone Edge Farm — A Sandbox For Microgrid Development". CleanTechnica. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "EEX Market Monitor Q3/2008" (PDF). Leipzig: Market Surveillance (HÜSt) group of the European Energy Exchange. 30 October 2008. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ Haubrich, Hans-Jürgen; Denzel, Dieter (23 October 2008). "Characteristics of interconnected operation" (PDF). Operation of Interconnected Power Systems (PDF). Aachen: Institute for Electrical Equipment and Power Plants (IAEW) at RWTH Aachen University. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2008. (See "Operation of Power Systems" link for title page and table of contents.)

- ^ "Serbia, Kosovo power grid row delays European clocks". Reuters. 7 March 2018.

- ^ Cooper, Christopher; Sovacool, Benjamin K. (February 2013). "Miracle or mirage? The promise and peril of desert energy part 1". Renewable Energy. 50: 628–636. Bibcode:2013REne...50..628C. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.07.027.

- ^ "UHV Grid". Global Energy Interconnection (GEIDCO). Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b . (2001). Glover J. D., Sarma M. S., Overbye T. J. (2010) Power System and Analysis 5th Edition. Cengage Learning. Pg 10.

- ^ a b Mezősi, András; Pató, Zsuzsanna; Szabó, László (2016). "Assessment of the EU 10% interconnection target in the context of CO2 mitigation†". Climate Policy. 16 (5): 658–672. Bibcode:2016CliPo..16..658M. doi:10.1080/14693062.2016.1160864.

- ^ Cuffe, Paul; Keane, Andrew (2017). "Visualizing the Electrical Structure of Power Systems". IEEE Systems Journal. 11 (3): 1810–1821. Bibcode:2017ISysJ..11.1810C. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2015.2427994. hdl:10197/7108. ISSN 1932-8184. S2CID 10085130.

- ^ Sajip, Jahnavi. "Why Do We Use Three-Phase Power?". www.ny-engineers.com. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). www.aep.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The basic things about substations you MUST know in the middle of the night!". EEP – Electrical Engineering Portal. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Electrical substation". energyeducation.ca. University of Calgary. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Hayes, Brian (2005). Infrastructure : a field guide to the industrial landscape (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-05997-9.

- ^ Hillhouse, Grady. "How Do Substations Work?". Practical Engineering. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Om E.ON | Elnät".

- ^ "How Power Grids Work". HowStuffWorks. April 2000. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Sallam, Abdelhay A. & Malik, Om P. (May 2011). Electric Distribution Systems. IEEE Computer Society Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780470276822.

- ^ Wang, Yingcheng; Gladwin, Daniel (January 2021). "Power Management Analysis of a Photovoltaic and Battery Energy Storage-Based Smart Electrical Car Park Providing Ancillary Grid Services". Energies. 14 (24): 8433. doi:10.3390/en14248433. ISSN 1996-1073.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Steven Warren Blume Electric power system basics: for the nonelectrical professional. John Wiley & Sons, 2007 ISBN 0470129875 p. 199

- ^ Alan Wyatt, Electric Power Challenges and Choices, The Book Press Limited, Toronto, 1986 ISBN 0-920650-00-7 page 63

- ^ Knight, U.G. Power Systems in Emergencies – From Contingency Planning to Crisis Management John Wiley & Sons 2001 ISBN 978-0-471-49016-6 section 7.5 The 'Black Start' Situation

- ^ Philip P. Walsh, Paul Fletcher Gas turbine performance, John Wiley and Sons, 2004 ISBN 0-632-06434-X, page 486

- ^ "California battery's black start capability hailed as 'major accomplishment in the energy industry'". 17 May 2017.

- ^ Willis, H. L., Welch, G. V., and Schrieber, R. R. (2001). Aging Power Delivery Infrastructures. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. 551 pgs.

- ^ "Industry Cross-Section Develops Action Plans at PJM Demand Response Symposium". Reuters. 13 August 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

Demand response can be achieved at the wholesale level with major energy users such as industrial plants curtailing power use and receiving payment for participating.

- ^ Hu, J.; Lanzon, A. (2019). "Distributed finite-time consensus control for heterogeneous battery energy storage systems in droop-controlled microgrids". IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid. 10 (5): 4751–4761. Bibcode:2019ITSG...10.4751H. doi:10.1109/TSG.2018.2868112. S2CID 117469364.

- ^ Fang, Xi; Misra, Satyajayant; Xue, Guoliang; Yang, Dejun (2012). "Smart Grid — the New and Improved Power Grid: A Survey". IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 14 (4): 944–980. doi:10.1109/SURV.2011.101911.00087.

- ^ "Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Assessment of Demand Response & Advanced Metering" (PDF). www.ferc.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ^ Sayed, K.; Gabbar, H. A. (1 January 2017). "Chapter 18 – SCADA and smart energy grid control automation". Smart Energy Grid Engineering. Academic Press: 481–514. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-805343-0.00018-8. ISBN 978-0-12-805343-0.

- ^ "Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Assessment of Demand Response & Advanced Metering" (PDF). United States Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-01-19. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ^ Saleh, M. S.; Althaibani, A.; Esa, Y.; Mhandi, Y.; Mohamed, A. A. (October 2015). "Impact of clustering microgrids on their stability and resilience during blackouts". 2015 International Conference on Smart Grid and Clean Energy Technologies (ICSGCE). pp. 195–200. doi:10.1109/ICSGCE.2015.7454295. ISBN 978-1-4673-8732-3. S2CID 25664994.

- ^ Torriti, Jacopo (2012). "Demand Side Management for the European Supergrid: Occupancy variances of European single-person households". Energy Policy. 44: 199–206. Bibcode:2012EnPol..44..199T. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.01.039.

- ^ "Smart Grids European Technology Platform". SmartGrids. 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "42 U.S. Code Subchapter IX - SMART GRID". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2024-08-05.

- ^ Kantamneni, Abhilash; Winkler, Richelle; Gauchia, Lucia; Pearce, Joshua M. (2016). "free open access Emerging economic viability of grid defection in a northern climate using solar hybrid systems". Energy Policy. 95: 378–389. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.05.013.

- ^ Khalilpour, R.; Vassallo, A. (2015). "Leaving the grid: An ambition or a real choice?". Energy Policy. 82: 207–221. Bibcode:2015EnPol..82..207K. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2015.03.005.

- ^ Kumagai, J (2014). "The rise of the personal power plant". IEEE Spectrum. 51 (6): 54–59. doi:10.1109/mspec.2014.6821622. S2CID 36554641.

- ^ The Economics of Grid Defection - Rocky Mountain Institute "The Economics of Grid Defection". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ Andy Balaskovitz Net metering changes could drive people off grid, Michigan researchers say Archived 15 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine – MidWest Energy News

- ^ "Grid defection and why we don't want it". 16 June 2015.

- ^ a b Borberly, A. and Kreider, J. F. (2001). Distributed Generation: The Power Paradigm for the New Millennium. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 400 pgs.

- ^ Warwick, W.M. (May 2002). "A Primer on Electric Utilities, Deregulation, and Restructuring of U.S. Electricity Markets" (PDF). United States Department of Energy Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP). Retrieved 2023-12-13.

- ^ Mr Alan Shaw (29 September 2005). "Kelvin to Weir, and on to GB SYS 2005" (PDF). Royal Society of Edinburgh. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2009.

- ^ "Survey of Belford 1995". North Northumberland Online. Archived from the original on 2016-04-12. Retrieved 2013-10-06.

- ^ "Lighting by electricity". The National Trust. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ Philippe CARRIVE, Réseaux de distribution – Structure et planification, volume D4210, collection Techniques de l'ingénieur, page 6.

- ^ "Journal Officiel n°0146, page 7895" (in French). 25 June 1986.

- ^ Mazer, A. (2007). Electric Power Planning for Regulated and Deregulated Markets. John, Wiley, and Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ. 313pgs.

- ^ People's Republic of China Year Book. Xinhua Publishing House. 1989. p. 190.

- ^ China Report: Economic affairs. Foreign Broadcast Information Service, Joint Publications Research Service. 1984. p. 54.

- ^ "Hong Kong Express Rail Link officially opens". Xinhuanet.com. 3 October 2018. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018.

- ^ Avishek G Dastidar (13 September 2018). "After initial questions, government clears 100% Railways electrification". The Indian Express.

- ^ "Beijing–Zhangjiakou intercity railway opens". National Development and Reform Commission. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

External links

[edit]- Open Infrastructure Map is a view of the world's hidden power infrastructure mapped in the OpenStreetMap database.

Electrical grid

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Core Functions

The electrical grid, or electric power system, constitutes an interconnected network of electrical components engineered to generate, transmit, and distribute electric power from production facilities to end-users.[8] This system encompasses power generation plants, high-voltage transmission lines, substations for voltage transformation, and lower-voltage distribution networks that deliver electricity to residential, commercial, and industrial consumers.[9] Predominantly operating on alternating current (AC), the grid facilitates efficient long-distance power transfer by minimizing resistive losses through high-voltage transmission, with step-down transformers enabling safe utilization at consumer levels.[3] Core functions of the electrical grid include the real-time balancing of electricity supply and demand to prevent blackouts, achieved via centralized control systems that monitor and adjust generation output.[10] It maintains synchronous operation across interconnected regions, regulating frequency—typically 50 Hz in Europe and 60 Hz in North America—to ensure stable machinery performance and grid integrity.[11] Voltage control represents another essential function, involving reactive power management through capacitors, inductors, and transformers to counteract fluctuations from load variations and line impedances.[12] The grid's design supports reliability through redundancy, such as multiple transmission paths and backup generation, enabling it to withstand faults like equipment failures or natural disasters without widespread disruption.[13] By interconnecting diverse generation sources, it optimizes resource utilization, dispatching cheaper or more available power while isolating issues to localized areas via protective relays and circuit breakers.[3] These functions collectively ensure continuous power delivery, underpinning modern economies dependent on uninterrupted electricity for critical infrastructure.[10]Physical Principles and AC/DC Distinctions

The transmission of electrical power in grids is governed by core electromagnetic principles, including the conservation of charge and energy. Electric current consists of charged particles, primarily electrons in conductors, driven by an electric potential difference (voltage) that induces flow according to Ohm's law, V = IR, where V is voltage, I is current, and R is resistance. Power delivered is P = VI, but transmission lines incur losses primarily as heat via Joule's law, P_loss = I²R, necessitating strategies to minimize current for given power levels.[14][15] Circuit analysis in power systems applies Kirchhoff's laws: the current law (KCL) requires the algebraic sum of currents at any node to be zero, ensuring charge conservation, while the voltage law (KVL) mandates that the sum of potential drops around any closed loop equals zero, reflecting energy conservation. These, alongside Ohm's law, enable modeling of interconnected generators, lines, and loads as linear or nonlinear networks, though real systems incorporate nonlinearities from saturation and faults.[16] Grids primarily employ alternating current (AC), in which voltage and current oscillate sinusoidally, reversing direction periodically—typically 50 Hz in Europe and 60 Hz in North America—facilitated by synchronous generators producing three-phase AC for efficient power delivery. Direct current (DC), by contrast, maintains unidirectional flow, as from batteries or rectified sources. AC dominates conventional grids due to transformers, which exploit Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction to step up voltages for transmission (e.g., to 500 kV or higher, reducing I²R losses by orders of magnitude) and step down for distribution, a process infeasible with DC until semiconductor converters emerged in the mid-20th century.[17][18] The historical adoption of AC traces to the late 1880s "War of the Currents," where Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse demonstrated AC's viability for long-distance transmission at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, powering incandescent lights over 1,000 feet with minimal loss via stepped-up voltages, outperforming Thomas Edison's DC systems limited to short ranges due to voltage drop. Technically, AC incurs skin effect (current concentrating near conductor surfaces, increasing effective resistance at high frequencies) and requires compensation for reactive power (due to inductors and capacitors causing phase shifts), but these are managed via capacitors and synchronous condensers; DC avoids reactivity and corona losses but demands expensive converter stations for voltage control.[18][17] High-voltage DC (HVDC) lines, operational since the 1950s (e.g., the 1954 Gotland link in Sweden at ±100 kV), are used selectively for asynchronous grid interconnections, undersea cables (where AC capacitance causes excessive charging currents), or ultra-long distances exceeding 500 km, achieving 3-4% lower losses than AC equivalents via constant polarity and no synchronization needs, though comprising under 2% of global transmission as of 2023 due to higher upfront costs.[19][20]Components

Power Generation

Power generation supplies electrical grids with alternating current (AC) produced primarily through electromagnetic induction in generators at power plants. This process relies on Faraday's law, which states that a time-varying magnetic field induces an electromotive force (EMF) in a conductor, generating current when the conductor forms a closed circuit.[21] In typical setups, mechanical energy from a prime mover rotates a rotor's magnetic field within stationary stator windings, producing three-phase AC electricity.[22] Synchronous generators dominate conventional power generation, operating at a rotational speed locked to the grid's nominal frequency—50 Hz in most regions or 60 Hz in North America—to ensure phase alignment and stable power delivery.[23] These machines provide rotational inertia that helps maintain grid frequency during disturbances, a property absent in inverter-based systems.[24] Prime movers include steam turbines fueled by coal, natural gas, oil, or nuclear fission heat; water turbines in hydroelectric dams; and combustion turbines in gas-fired plants.[25] For instance, combined-cycle gas turbines achieve efficiencies up to 60% by recovering waste heat to generate additional steam.[26] Renewable sources integrate differently: hydroelectric and some wind installations use synchronous generators directly coupled to turbines, while variable-speed wind turbines employ doubly-fed induction generators with partial power conversion for frequency matching.[26] Solar photovoltaic arrays produce direct current (DC), converted to grid-synchronous AC via inverters that emulate synchronous behavior but contribute minimal inertia, necessitating grid-stabilizing controls at high penetration levels.[27] Geothermal and biomass plants typically mirror thermal designs with steam turbines. In 2023, global electricity generation reached approximately 29,000 terawatt-hours, with fossil fuels comprising over 59%—coal at 35% and gas at 23%—nuclear at 9%, and renewables at 30% including 15% hydro, 7% wind, and 5% solar.[28] Capacity factors reflect dispatchability: nuclear plants average 90% annual utilization, coal around 50%, wind 35%, and solar 25%, underscoring the need for firm, controllable capacity to match variable demand.[29] Generators connect to the grid via step-up transformers raising output voltages (typically 10-25 kV) to transmission levels of 100-765 kV, minimizing losses over long distances.[25] Synchronization requires matching voltage, frequency, and phase before paralleling to avoid damaging currents or instability.[30]Transmission Infrastructure

![500 kV three-phase transmission lines][float-right] Transmission infrastructure refers to the high-voltage components that convey bulk electrical power from generation facilities to load-serving substations over distances often exceeding 50 kilometers. These systems primarily utilize alternating current (AC) at voltages from 110 kV upward to minimize energy losses through reduced current for a given power transfer, as governed by Ohm's law where power loss equals I²R.[31] In the United States, predominant voltage classes include 115 kV, 230 kV, and 500 kV for alternating-current lines, enabling efficient transport of gigawatts across interconnected grids.[31] Core elements encompass overhead conductors, support structures, insulators, and static shielding wires. Conductors are typically aluminum conductor steel-reinforced (ACSR) cables, combining high electrical conductivity of aluminum with tensile strength from steel cores to withstand mechanical stresses like wind and ice loading while spanning distances between supports.[32] Insulators, often porcelain or composite materials, prevent unintended conduction to ground or between phases, designed to endure voltages up to 1,000 kV in ultra-high-voltage applications.[33] Ground wires atop structures intercept lightning strikes, protecting the phase conductors below.[32] Support structures vary by voltage, terrain, and load: lattice steel towers predominate for extra-high voltages due to their rigidity and capacity to handle multiple circuits, while tubular steel poles suit compact urban corridors or lower voltages.[34] Tower types include suspension configurations for straight-line spans, tension or dead-end towers for route deviations up to 60 degrees, and transposition towers to balance phase impedances over long lines.[35] Designs account for factors like span length (typically 300-500 meters), conductor sag under thermal expansion, and electromagnetic fields, with heights reaching 50-100 meters for 500 kV lines to maintain ground clearance.[36] The United States features over 500,000 miles of transmission lines, forming a backbone that has seen annual investment rise to $27.7 billion by 2023 amid demands for expanded capacity.[37] [38] Globally, high-voltage lines total approximately 3 million kilometers, with ongoing expansions adding 1.5 million kilometers over the past decade to integrate remote renewables and support electrification.[39] [40] Transmission efficiency hovers at 95% in mature grids like the US, where losses—primarily resistive heating and corona discharge—average 5% of generated power, varying with load, weather, and line age.[41] Underground cables, used sparingly for high-density areas due to costs 10-20 times overhead equivalents, employ extruded insulation like XLPE for direct burial or ducted installation up to 500 kV. Reliability hinges on redundancy, with N-1 contingency standards ensuring no single failure cascades, though aging infrastructure and permitting delays pose risks to expansion.Substations and Switching

Substations serve as key nodes in electrical power systems, facilitating voltage transformation between generation, transmission, and distribution levels, as well as enabling the switching of circuits to maintain system reliability and isolate faults.[42][43] They house equipment such as power transformers for stepping up voltages to 500 kV or higher for efficient long-distance transmission and stepping down to medium voltages around 11-33 kV for distribution.[44] Circuit breakers and disconnectors within substations allow operators to connect or isolate transmission lines, generators, or loads, preventing widespread outages during faults like short circuits or overloads.[45][46] Switching functions in substations rely on high-voltage switchgear, including circuit breakers capable of interrupting fault currents up to tens of kiloamperes under normal and abnormal conditions.[46] These devices, often gas-insulated or air-insulated for voltages above 36 kV, integrate protective relays that detect abnormalities via current and voltage sensors, triggering automatic disconnection to protect transformers and lines from damage.[47][48] Busbars distribute power within the substation, while lightning arresters and insulators safeguard against surges and ensure insulation integrity.[44][49] Switching stations, a specialized type of substation, operate without transformers at a single voltage level, primarily to interconnect multiple transmission lines and provide reconfiguration flexibility.[50] They employ high-speed switches and circuit switchers for remote fault isolation, minimizing downtime by sectionalizing lines without altering voltage.[51][52] In transmission networks, such stations enhance operational efficiency, as seen in configurations where they link disparate lines to balance loads or reroute power during maintenance.[53] Substations and switching facilities incorporate monitoring systems for real-time data on voltage, current, and equipment status, supporting predictive maintenance and compliance with standards like those from the IEEE for breaker performance.[54] Outdoor designs predominate for high-voltage applications due to space needs for air insulation, though gas-insulated variants reduce footprint in urban areas.[55] Fault-tolerant designs, including redundant bus arrangements, ensure continuity, with typical substation capacities handling gigawatt-scale power flows in major grids.[56][54]Distribution Systems

Distribution systems form the final stage of the electrical grid, delivering power from high-voltage transmission networks to end-users at usable voltages. These systems typically operate at medium voltages ranging from 4 kV to 35 kV for primary distribution feeders, which branch out from substations to local areas.[57] Substations step down transmission-level voltages (often 69 kV or higher) using transformers, enabling efficient power flow over shorter distances while minimizing losses. Secondary distribution then further reduces voltage to standard utilization levels, such as 120/240 V for single-phase residential service or 208/480 V for three-phase commercial and industrial loads in North America. Key components include distribution transformers, which provide localized voltage transformation and isolation; overhead or underground lines and feeders for power conveyance; and protective equipment such as circuit breakers, reclosers, and fuses to detect and isolate faults like short circuits or overloads.[58] Lines are predominantly overhead in rural and suburban areas for cost efficiency, comprising bare conductors on poles, while urban settings increasingly use underground cables to reduce visual impact and weather vulnerability, though at higher installation and maintenance costs. Feeders are designed with sectionalizing devices to limit outage scopes during faults, and voltage regulators maintain levels within ±5% of nominal to ensure equipment compatibility.[59] Configurations vary by load density and reliability needs. Radial systems, the most common and economical arrangement, supply power unidirectionally from a single substation source in a tree-like structure, suitable for low-density areas but vulnerable to widespread outages from feeder failures.[60] In contrast, network systems in high-density urban cores employ multiple interconnected feeders and spot networks, allowing automatic reconfiguration and redundancy to minimize downtime, as power can reroute via parallel paths. Loop or ring main systems offer intermediate reliability by enabling manual or automatic switching between feeder ends, reducing isolation times without full meshing.[61] These designs balance capital costs against service continuity, with radial setups dominating due to their simplicity and lower equipment requirements. Operational challenges in distribution systems stem from inherent vulnerabilities and evolving demands. Aging infrastructure, including poles over 50 years old in many regions, heightens risks of failure from storms or corrosion, contributing to frequent outages.[62] Radial configurations amplify this by lacking backup paths, leading to cascading effects from localized faults. Increasing penetration of distributed generation, such as rooftop solar, introduces bidirectional flows and voltage fluctuations that strain unidirectional designs, necessitating advanced controls like inverters and sensors for stability. Protective coordination remains critical, as improper settings can cause unnecessary tripping or delayed fault clearing, potentially damaging customer equipment.[63] Maintenance focuses on predictive techniques, including infrared thermography for hot spots and ground-penetrating radar for cable integrity, to preempt disruptions in systems handling peak loads up to several megawatts per feeder.Energy Storage Integration

Energy storage systems (ESS) are integrated into electrical grids to address the intermittency of renewable sources, provide ancillary services such as frequency regulation and voltage support, and enable efficient load balancing by storing excess generation for later dispatch.[64] These systems decouple electricity production from consumption, allowing grids to maintain stability amid variable supply and demand patterns.[65] Integration occurs at utility-scale through connections to transmission or distribution networks, often via inverters for AC compatibility, with control systems coordinating charging and discharging based on grid signals.[66] Prominent ESS technologies include pumped hydroelectric storage (PHS), which accounts for the majority of global capacity at approximately 189 GW as of 2024, utilizing elevation differences to store gravitational potential energy by pumping water uphill during low-demand periods and releasing it through turbines for generation.[67] Lithium-ion batteries have seen rapid deployment, with global grid-scale capacity reaching about 28 GW by the end of 2022, primarily for short-duration applications due to their high efficiency (around 85-95%) and rapid response times under one second.[64] Other forms encompass compressed air energy storage (CAES), which compresses air in underground caverns for later expansion through turbines, offering longer-duration storage but with lower round-trip efficiencies of 40-70%; and flywheels, which store kinetic energy in rotating masses for ultra-fast frequency response.[68][69] Integration enhances grid stability by providing inertia-like services through synthetic controls in battery systems, mitigating frequency deviations that arise from sudden generation losses or load changes, as demonstrated in high-renewable penetration scenarios where ESS reduces under-frequency load shedding risks.[70] Economically, ESS supports peak shaving to defer costly infrastructure expansions and facilitates renewable curtailment avoidance, though benefits vary by market design; for instance, in regions with competitive ancillary service markets, batteries have delivered returns via arbitrage and regulation services.[71][72] Challenges to widespread adoption include high upfront capital costs—lithium-ion systems at $147-339/kWh projected for 2035—degradation over cycles limiting lifespan to 10-15 years for frequent use, and regulatory hurdles in compensating stacked services like energy arbitrage combined with frequency response.[73][74] Technical integration issues involve grid code compliance for fault ride-through and harmonic mitigation, while supply chain dependencies, particularly for battery minerals, pose scalability risks absent diversified sourcing.[75][76] Notable projects illustrate successful integration; the Hornsdale Power Reserve in South Australia, a 100 MW/129 MWh lithium-ion facility commissioned in 2017, has stabilized the grid by providing rapid frequency control ancillary services (FCAS), reducing system restart risks and generating over AUD 100 million in first-year savings through FCAS market participation.[77][78] In the United States, cumulative grid storage reached 31.1 GWh by 2024, with facilities like Moss Landing contributing to California's renewable integration by dispatching during evening peaks.[79] These deployments underscore ESS's role in enabling higher renewable shares without compromising reliability, provided markets evolve to value multi-service capabilities.Operational Dynamics

Synchronization and Frequency Regulation

Synchronization in electrical grids ensures that alternating current (AC) generators operate in phase with the existing grid voltage, matching frequency, phase angle, and magnitude before paralleling to avoid damaging currents or equipment failure.[80] This process relies on synchronous machines whose rotor speed is locked to the grid frequency via the synchronous speed formula, , where is frequency in Hz and is the number of poles.[80] In interconnected synchronous grids, such as North America's Eastern and Western Interconnections operating at 60 Hz, all generators must maintain this lockstep to enable power sharing without phase mismatches. Frequency regulation maintains nominal grid frequency—typically 60 Hz in North America and 50 Hz in Europe—by continuously balancing real power generation against load demand, as deviations arise from mismatches where excess load causes frequency decline and surplus generation causes rise.[81] Synchronous generators provide inherent inertia through their rotating masses, resisting rapid frequency changes; for instance, the kinetic energy stored in turbine-generator rotors dampens rate-of-change-of-frequency (RoCoF) during disturbances.[82] Primary frequency control, activated within seconds via turbine governors using droop characteristics (e.g., 4-5% speed droop), adjusts mechanical power input proportionally to frequency deviation to restore balance locally.[83] Secondary control, or automatic generation control (AGC), operates over minutes through centralized area control error (ACE) signals that account for frequency bias, scheduled interchanges, and actual power flows, dispatching reserves to return frequency to nominal and correct tie-line deviations.[81] NERC Reliability Standard BAL-001-2 mandates that balancing authorities maintain interconnection frequency within defined limits, such as ±0.036 Hz around 60 Hz for the Eastern Interconnection, using performance metrics like control performance standards (CPS1 and BAAL). Under extreme imbalances, protective relays trigger under-frequency load shedding (UFLS) at thresholds like 59.5-58.8 Hz to prevent cascading failures, as specified in NERC PRC-024 standards. In modern grids with increasing inverter-based resources, traditional inertia declines, necessitating synthetic inertia emulation and fast frequency response (FFR) from batteries or demand-side participation to mitigate higher RoCoF risks, though synchronous generation remains foundational for stability.[24][84] NERC's 2025 State of Reliability report highlights battery energy storage systems' role in enhancing primary response, as demonstrated in ERCOT where BESS deployment improved frequency nadir during contingencies.[85]Voltage Management and Stability

Voltage management in electrical power grids entails maintaining bus voltages within narrow operational limits, typically ±5% of nominal values, to prevent equipment damage, ensure efficient power transfer, and avoid cascading failures. This process relies on reactive power (VAR) compensation, as transmission lines and loads exhibit inductive characteristics that consume VARs, causing voltage drops according to Ohm's law extended to complex power (V = I * Z, where Z includes reactance). Generators primarily regulate voltage via automatic voltage regulators (AVRs) that modulate field current to control excitation, injecting or absorbing VARs as needed; for instance, overexcitation boosts voltage by supplying leading VARs.[86][87] Secondary controls include on-load tap-changing transformers (OLTCs), which adjust turns ratios to compensate for voltage variations at substations, and switched shunt devices such as capacitor banks for injecting VARs during peak loads or reactors for absorption under light loads. Advanced flexible AC transmission systems (FACTS) devices, like static VAR compensators (SVCs) and static synchronous compensators (STATCOMs), provide dynamic, continuous VAR support by leveraging power electronics to respond within milliseconds to fluctuations, outperforming slower mechanical switches in high-renewable penetration scenarios where inverter-based resources lack inherent reactive capability.[88][89] Voltage stability assesses the grid's resilience to disturbances, defined as the maintenance of power-voltage equilibrium where, for a given active power transfer, there exists a solution satisfying load demands without indefinite voltage decline. Instability arises from mechanisms including load dynamics (e.g., motor stalling drawing excessive inductive current), inadequate generator excitation limits, or OLTC interactions amplifying remote voltage sags; a key indicator is the proximity to the nose point on PV curves, where the Jacobian matrix becomes singular, signaling maximum loadability.[90][91] In systems with high distributed energy resources, reduced short-circuit ratios exacerbate voltage instability by diminishing grid strength, necessitating coordinated inverter control for synthetic inertia and VAR provision.[86] Preventive measures involve real-time monitoring via phasor measurement units (PMUs) for wide-area visibility and stability indices like the L-index or voltage stability margin, which quantify proximity to collapse; contingency analysis simulates N-1 (single element outage) scenarios to enforce reactive reserves, often mandated at 15-20% above peak demand in transmission planning standards. Historical voltage collapses, such as the August 14, 2003, North American blackout—partially attributed to reactive power shortages and high line loading—highlight causal chains where initial faults propagate via under-voltage load shedding failures, affecting 50 million customers across eight states.[92][91] Remedial actions, including generator tripping or FACTS modulation, restore margins but underscore the empirical need for overbuilding reactive capacity to counter causal factors like deferred maintenance or load growth.[90]Capacity Planning and Firm Power

Capacity planning in electrical grids involves forecasting future electricity demand, assessing available generation resources, and determining the necessary infrastructure investments to maintain reliability under varying conditions. This process employs probabilistic reliability criteria, such as the North American Electric Reliability Corporation's (NERC) standard for a "one day in ten years" loss-of-load expectation (LOLE), which quantifies the acceptable risk of insufficient generation to meet demand. Planners use capacity expansion models to simulate scenarios, incorporating factors like load growth, retirements of existing plants, and additions of new capacity, often over 10- to 20-year horizons.[93] These models account for transmission constraints and integrate tools like production cost simulations to evaluate economic dispatch and reserve margins, typically targeting 15-20% above peak load in many regions to buffer against outages or extreme weather.[94] Firm power, defined as dispatchable generation capable of delivering its rated output on demand regardless of external conditions (except scheduled maintenance), forms the core of reliable capacity in planning assessments. Unlike variable renewable sources such as wind or solar, which exhibit low capacity factors—often 20-40% for onshore wind and 15-25% for solar photovoltaics—firm resources like nuclear, coal, natural gas combined-cycle plants, or hydroelectric facilities provide near-100% availability when needed.[95][96] Effective load-carrying capability (ELCC), a metric adjusting for intermittency, assigns renewables lower contributions to peak reliability; for instance, high solar penetration can reduce ELCC to under 10% in some systems due to coincident generation with demand peaks.[97] Grid operators thus prioritize firm capacity to meet firm demand— the portion of load requiring uninterrupted service—ensuring stability during periods of low renewable output, such as calm nights. Integration of intermittent renewables complicates capacity planning by necessitating overbuilding non-firm resources or adding firming mechanisms like long-duration storage or backup gas peakers, which increase system costs and land requirements. NERC standards require balancing authorities to document resource adequacy, revealing shortfalls in regions with rapid renewable growth; for example, California's grid faced reserve margin deficits in 2022 due to solar-dependent planning without sufficient firm backups.[98] Empirical data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows that grids with over 30% variable renewables often require 2-3 times the nameplate capacity in firm equivalents to achieve equivalent reliability, underscoring the causal link between intermittency and expanded planning needs.[99] Planners mitigate this through diversified portfolios, but systemic biases in some academic and policy sources—favoring renewables without fully quantifying backup costs—can lead to optimistic projections that overlook these realities.[100]Demand Response Mechanisms

Demand response mechanisms involve programs and strategies that incentivize electricity consumers to adjust their usage patterns, typically by reducing or shifting demand from peak periods to off-peak times, in order to balance supply constraints and avoid curtailments or blackouts.[101] These approaches treat demand as a flexible resource akin to generation, enabling grid operators to maintain frequency stability and defer investments in new capacity.[102] Implementation relies on communication technologies, such as advanced metering infrastructure, which by 2023 accounted for 111.2 million meters out of 162.8 million total in the United States, facilitating real-time responsiveness.[103] Mechanisms are broadly classified into price-based and incentive-based categories. Price-based programs include time-of-use (TOU) tariffs, which charge higher rates during anticipated peaks to encourage load shifting, and real-time pricing (RTP), which reflects instantaneous wholesale costs to consumers.[101] Incentive-based programs, conversely, offer direct payments or bill credits for verifiable reductions, often through utility-managed direct load control of appliances like air conditioners or interruptible service contracts for industrial loads.[104] In wholesale markets, economic demand response allows aggregated loads to bid into capacity or energy markets, competing with generators; for instance, the PJM Interconnection has integrated demand response to provide up to several gigawatts of capacity during high-demand events.[105] In practice, programs vary by region and regulatory framework. California's investor-owned utilities, overseen by the California Public Utilities Commission, administer demand response targeting commercial and industrial sectors, with economic programs contributing around 1,612 megawatts as of earlier assessments, though participation has faced challenges from measurement baselines and consumer opt-in rates.[105][106] Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) assessments highlight national penetration, with demand response reducing peak loads by 5-10% in participating areas, lowering system costs by avoiding peaker plant dispatch, which can exceed $1,000 per megawatt-hour during scarcity.[107] Empirical studies confirm benefits like enhanced renewable integration by smoothing variability, though costs include program administration and potential rebound effects post-event.[105] Effectiveness depends on verifiable baselines for load reduction credits and automation via smart devices, with peer-reviewed analyses showing net system savings from deferred transmission upgrades and reduced emissions compared to fossil-fired reserves.[108] However, adoption barriers persist, including low voluntary participation among residential users—often below 10% without mandates—and disputes over compensation fairness in competitive markets.[109] In high-renewable scenarios, demand response supports grid inertia by aligning consumption with variable output, as modeled in integrations exceeding 30% wind and solar penetration.[110]Configurations and Scales

Synchronous Wide-Area Grids