Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

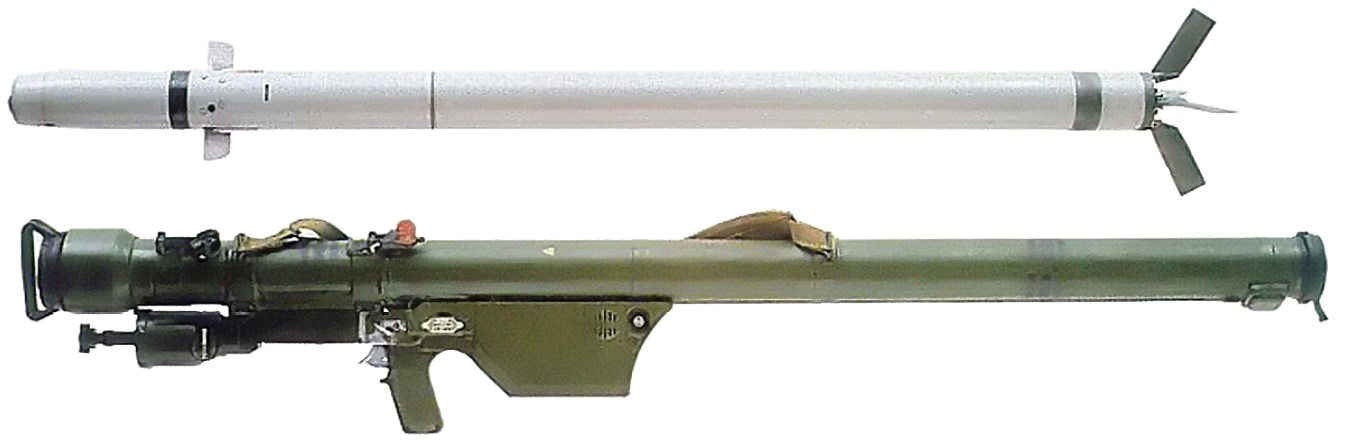

9K32 Strela-2

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The 9K32 Strela-2 (Russian: Cтрела, lit. 'Arrow'; NATO reporting name SA-7 Grail) is a light-weight, shoulder-launched, surface-to-air missile or MANPADS system. It is designed to target aircraft at low altitudes with passive infrared-homing guidance and destroy them with a high-explosive warhead.

Key Information

Broadly comparable in performance with the US Army FIM-43 Redeye, the Strela-2 was the first Soviet man-portable SAM – full-scale production began in 1970.[4] While the Redeye and 9K32 Strela-2 were similar, the missiles were not identical.

The Strela-2 was a staple of the Cold War and was produced in huge numbers for the Soviet Union and their allies, as well as revolutionary movements.[5] Though since surpassed by more modern systems, the Strela and its variants remain in service in many countries, and have seen use in nearly every regional conflict since 1972.

Development

[edit]The end of World War II led to a major shift in Soviet defence policy. The advent of long range, high altitude, nuclear-armed American bombers, capable of penetrating Soviet airspace at heights and speeds unreachable and unmatchable by anti-aircraft guns and most interceptors, appeared to render every conventional weapon obsolete at a stroke. Numerous long-range, high-altitude SAM systems, such as the S-25 Berkut and S-75 Dvina, were rapidly developed and fielded to counter this large vulnerability. Due to the apparent obsolescence of conventional arms, however, relatively little development took place to field mobile battlefield air defences.

This direction was soon changed with the beginning of the Korean War. An entirely conventional conflict, it proved that nuclear weapons were not the be-all and end-all of warfare. In the face of a powerful and modern American air force, carrying non-nuclear payloads, the Soviet Union invested heavily in a multi-tier air defence system, consisting of several new mobile SAMs, to cover all altitude ranges and protect ground forces. The new doctrine listed five requirements:

- Front-level medium-to-high-altitude area defense system 9K8 Krug (NATO designation SA-4 "Ganef")

- Army-level low-to-medium-range area defense system 3K9 Kub (NATO designation SA-6 "Gainful")

- Division-level low-altitude short-range system 9K33 Osa (NATO designation SA-8 "Gecko")

- Regiment-level all-weather radar-guided gun system ZSU-23-4 "Shilka" and very-short-range missile systems 9K31 Strela-1 (NATO designation SA-9 "Gaskin")

- Battalion-level man-portable 9K32 Strela-2 (NATO designation SA-7 "Grail")

Both Strela-1 and Strela-2 were initially intended to be man-portable systems. As the Strela-2 proved to be a considerably smaller and lighter package, however, the role of the Strela-1 was changed, becoming a heavier, vehicle-mounted system with increased range and performance to better support the ZSU-23-4 in the regimental air defense role.

As development began in the Turopov OKB (later changed to Kolomna), detailed information on the design of the US FIM-43 Redeye became available. While it was not a reverse-engineered copy, in many ways the Strela design borrowed heavily from the Redeye, which had started development a few years earlier.[citation needed] Due to the comparatively primitive Soviet technical base, development was protracted, and many problems arose, especially in designing a sufficiently small seeker head and rocket. Eventually, the designers settled for a simpler seeker head than that of the Redeye, allowing the initial version, the 9K32 "Strela-2" (US DoD designation SA-7A, missile round 9M32) to finally enter service in 1968, five years behind schedule. At the time, it was described by one expert as being "the premier Russian export line".[6]

Improvements

[edit]The initial variant suffered from numerous shortcomings: it could only engage targets flying at relatively slow airspeeds and low altitudes and then only from rear hemisphere, it suffered from poor guidance reliability (particularly in the presence of natural or man-made background IR radiation sources), and even when a hit was achieved, it often failed to destroy the target.[7][8] Poor lethality was an issue especially when used against jet aircraft: the hottest part of the target was the nozzle behind the actual engine, which the missile therefore usually hit; but there its small warhead often failed to cause significant damage to the engine itself.

In order to address the shortcomings, two improved versions were ordered in 1968; as an intermediate stop-gap the slightly improved 9K32M "Strela-2M" (NATO reporting name SA-7b) to replace the original, as well as the more ambitious Strela-3.

As the modifications introduced with the Strela-2M were relatively minor, the process was fast and it was accepted in service in 1970.[8] The Strela-2M replaced the Strela-2 in production lines immediately. Improvements were made particularly to increase the engagement envelope of the new system:[7]

- Higher thrust propellant increased slant range from 3.4 to 4.2 km (2.1 to 2.6 mi) and ceiling from 1.5 to 2.3 km (0.93 to 1.43 mi)

- Improved guidance and control logic allowed the engagement of helicopters and propeller-driven aircraft (but not jets) approaching at a maximum speed of 150 m/s (490 ft/s; 340 mph)

- Maximum speed of receding targets was increased from 220 to 260 m/s (720 to 850 ft/s; 490 to 580 mph)

- More automated gripstock provided a simplified firing method against fast targets: a single trigger pull followed by lead and superelevation replacing the separate stages of releasing the seeker to track, and launching the missile (see description below)

Contrary to what was initially reported in some Western publications, more recent information indicates that, while lethality on impact had proven to be a problem, the warhead remained the same 1.17 kg (2.6 lb) unit (including 370-gram (13 oz) TNT charge) as in the original.[9] This remained the warhead of all Soviet MANPADS up to and including most 9K38 Igla variants; to address the problem of poor lethality, a more powerful HE filling than TNT, improved fuzing, a terminal maneuver, and finally a separate charge to set off any remaining rocket fuel were gradually introduced in later MANPADS systems, but the original Strela-2/2M warhead design of a 370-gram (13 oz) directed-energy HE charge in a pre-fragmented casing remained.

The seeker head improvements were only minor changes to allow better discrimination of the target signal against background emissions.[7][9] Some sources claim that the seeker sensitivity was also improved.[8] The only defence against infra-red countermeasures remained the seeker head's narrow field of view, which could be hoped to help the rapidly slowing flare fall off the missile field of view as it was tracking a fast-moving target.[7] In practice, flares proved to be a highly effective countermeasure against both versions of the Strela-2.

The seeker is commonly referred to as a hot metal tracker. The seeker can only see infrared energy in the near infrared (NIR) spectrum, emitted by very hot surfaces only seen on the inside of the jet nozzle. This allows only rear-aspect engagement of jet targets, earning the weapon its other moniker as a revenge weapon, since the missile has to "chase" an aircraft after it has already passed by.

The Strela-2M was also procured for use on-board Warsaw Pact warships;[10] installed on four-round pedestal mounts[10] aboard Soviet amphibious warfare vessels and various smaller combatants, the weapon remained unchanged, but was assigned the NATO reporting name SA-N-5 "Grail".[10]

Description

[edit]The missile launcher system consists of the green missile launch tube containing the missile, a grip stock and a cylindrical thermal battery. The launch tube is reloadable at depot, but missile rounds are delivered to fire units in their launch tubes. The device can be reloaded up to five times.[11]

When engaging slow or straight-receding targets, the operator tracks the target with the iron sights in the launch tube and applies half-trigger. This action "uncages" the seeker and allows its attempt to track. If a target IR signature can be tracked against the background present, this is indicated by a light and a buzzer sound. The shooter then pulls the trigger fully, and immediately applies lead and superelevation. This method is called a manual engagement. An automatic mode, which is used against fast targets, allows the shooter to fully depress the trigger in one pull followed by immediate lead and superelevation of the launch tube. The seeker will uncage and will automatically launch the missile if a strong enough signal is detected.

The manufacturer lists reaction time measured from the carrying position (missile carried on a soldier's back with protective covers) to missile launch to be 13 seconds, a figure that is achievable but requires considerable training and skill in missile handling. With the launcher on the shoulder, covers removed and sights extended, reaction time from fire command to launch reduces to 6–10 seconds, depending greatly on the target difficulty and the shooter's skill.

After activating the power supply to the missile electronics, the gunner waits for electricity supply and gyros to stabilize, puts the sights on target and tracks it smoothly with the launch tube's iron sights, and pulls the trigger on the grip stock. This activates the seeker electronics and the missile attempts to lock onto the target. If the target is producing a strong enough signal and the angular tracking rate is within acceptable launch parameters, the missile alerts the gunner that the target is locked on by illuminating a light in the sight mechanism, and producing a constant buzzing noise. The operator then has 0.8 seconds to provide lead to the target while the missile's on-board power supply is activated and the throw-out motor ignited.

Should the target be outside acceptable parameters, then the light cue in the sight and the buzzer signal tell the gunner to re-aim the missile.

On launch, the booster burns out before the missile leaves the launch tube at 32 m/s (100 ft/s) and rotating at around 20 revolutions per second. As the missile leaves the tube, the two forward steering fins unfold, as do the four rear stabilizing tail fins. The self-destruct mechanism is then armed, which is set to destroy the missile after between 14 and 17 seconds to prevent it hitting the ground if it should miss the target.

Once the missile is five and a half meters away from the gunner, about 0.3 seconds after leaving the launch tube, it activates the rocket sustainer motor. The sustainer motor takes it to a velocity of 430 metres per second (1,400 ft/s; 960 mph), and sustains it at this speed. Once it reaches peak speed, at a distance of around 120 metres (390 ft) from the gunner, the final safety mechanism is disabled and the missile is fully armed. All told, the booster burns for 0.5 seconds and the driving engine for another 2.0 seconds.[11]

The missile's uncooled lead sulfide passive infra-red seeker head detects infrared radiation at below 2.8 μm in wavelength. It has a 1.9 degree field of view and can track at 9 degrees per second. The seeker head tracks the target with an amplitude-modulated spinning reticle (spin-scan or AM tracking), which attempts to keep the seeker constantly pointed towards the target. The spinning reticle measures the amount of incoming infrared (IR) energy. It does this by using a circular pattern that has solid portions and slats that allow the IR energy to pass through to the seeker. As the reticle spins IR energy passes through the open portions of the reticle. Based on where the IR energy falls on the reticle the amount or amplitude of IR energy allowed through to the seeker increases the closer to the center of the reticle. Therefore, the seeker is able to identify where the center of the IR energy is. If the seeker detects a decrease in the amplitude of the IR energy it steers the missile back towards where the IR energy was the strongest. The seeker's design creates a dead-space in the middle of the reticle. The center mounted reticle has no detection capability. This means that as the seeker tracks a target as soon as the seeker is dead center, (aimed directly at the IR source) there is a decrease in the amplitude of IR energy. The seeker interprets this decrease as being off target so it changes direction. This causes the missile to move off target until another decrease in IR energy is detected and the process repeats itself. This gives the missile a very noticeable wobble in flight as the seeker bounces in and out from the dead-space. This wobble becomes more pronounced as the missile closes on the target as the IR energy fills a greater portion of the reticle. These continuous course corrections effectively bleed energy from the missile reducing its range and velocity.

The guidance of the SA-7 follows proportional convergence logic, also known as angle rate tracking system or pro-logic. In this method, as the seeker tracks the target, the missile is turned towards where the seeker is turning towards – not where it is pointing at – relative to the missile's longitudinal axis. Against a target flying in a straight-line course at constant speed, the angle rate of seeker-to-body reduces to zero when the missile is in a straight-line flight path to intercept point.

Combat use

[edit]As a consequence of their widespread availability and large numbers, the Strela system has seen use in conflicts across the globe.

Middle East

[edit]Egypt

[edit]The first combat use of the missile is credited as being in 1969 during the War of Attrition by Egyptian soldiers.[12] The first "kill" was claimed on 19 August 1969. An Israeli 102 Squadron A-4H Skyhawk was hit with a shoulder-fired missile 19 km (12 mi) west of the Suez Canal and pilot SqL Nassim Ezer Ashkenazi captured. Between this first firing and June 1970 the Egyptian army fired 99 missiles resulting in 36 hits. The missile proved to have poor kinematic reach against combat jets, and also poor lethality as many aircraft that were hit managed to return safely to base.

The missile was used later in the Yom Kippur War,[13][14] where 4,356 Strelas were fired,[13] scoring few hits and just 2[14] to 4[13] kills, with 26[14] to 28[13] damaged. A-4s were fitted with lengthened exhaust pipes in order to prevent fatal damage to the engine, a solution made in the previous war, together with flare launchers. However, together with Shilka and SA-2/3/6s, they caused very heavy losses to the Israeli Air Force in the first days. Subsequently, Arab forces fired so many SAMs that they almost depleted their weapon stocks. SA-7s were not that effective against fast jets, but they were the best weapon available to Arab infantry at the time.[citation needed]

A Strela 2 was reportedly used by the Islamist militant group Ansar Bait al-Maqdis to destroy an Egyptian military Mil-8 helicopter operating in the northern Sinai region on 26 January 2014 near Sheikh Zuweid (close to the border with Gaza), killing its five occupants. This is the first attack of this type during the Sinai insurgency, which has raged on the peninsula due to the security and political turmoil since the 2011 revolution. The MANPADS is reported by United Nations to have come from former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi's large stocks, which have been widely proliferated after Libya's civil war chaos and have become a concern to regional and world security.[15]

Syria

[edit]The Strela was deployed by Syrian forces occupying Lebanon, along with other Soviet air-defence systems that challenged U.S., French and Israeli airpower in the aftermath of the 1982 conflict and the deployment of the Multinational Force in Lebanon during that year. On 10 November 1983, an SA-7 was fired at a French Super Etendard near Bourj el-Barajneh while flying over Druze People's Liberation Army (PLA) positions. On 3 December, more Strelas and anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) were fired at United States Navy F-14 Tomcats flying a reconnaissance mission.[16][17]

The Americans responded with a large strike package of 12 A-7 Corsairs and 16 A-6 Intruders (supported by a single E-2C Hawkeye, two EA-6B Prowlers and two F-14As) launched from the carriers USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) and USS Independence (CV-62) sailing in the Mediterranean. The aircraft were to bomb Syrian installations, AAA sites and weapons depots near Falouga and Hammana, some 16 km (10 mi) north of Beirut-Damascus highway, when they were received by a volley of (possibly up to 40) Syrian SAMs, one of which hit a Corsair (AE305 of the VA-15), forcing the pilot to eject over the sea before being rescued by a USN search and rescue mission.[17]

The attack formation broke, with each pilot attacking each objective on its own, leading to the downing of a second U.S. aircraft, an Intruder from VA-85, hit by either an SA-7 or an SA-9. The navigator, Lieutenant Bobby Goodman ejected near a village surrounded by Syrian positions. The pilot, Lt. Mark Lange, ejected too late and died from his wounds soon after being captured by Syrian soldiers and Lebanese civilians. Goodman was captured by the Syrians and taken to Damascus before being freed in January 1984.[16][18]

A second Corsair, searching for the downed Intruder crew, was later hit by an SA-7. The pilot, Cdr. Edward Andrews, managed to eject over the sea near Beirut and was rescued by a fisherman and his son who in turn handed him over to the U.S Marines.[16][18]

During the civil war, several Strelas have made their way to rebel hands, and YouTube videos have shown them being fired. In 2013, Foreign Policy, citing rebels sources, reported the shipment, with Qatari help, of some 120 SA-7s from Libya (with large stocks acquired by Gaddafi and proliferated after that country's civil war) through Turkey and with Turkish authorities' knowledge.[19][20]

Lebanon

[edit]On 24 June 1974, Palestinian guerrillas operating in southern Lebanon fired two SA-7s against invading Israel Air Force (IAF) aircraft, though no hits were scored.[21]

The Lebanese Al-Mourabitoun militia received either from Syria or the PLO a number of SA-7s, which they employed against Israeli Air Force (IAF) fighter-bomber jets during the 1982 Lebanon War.[22]

During the 1983–84 Mountain War, the Druze People's Liberation Army (PLA) militia received from Syria a number of Strela missiles, which were used to bring down two Lebanese Air Force Hawker Hunter fighter jets[23] and one Israeli IAI Kfir fighter-bomber aircraft, on 20 November over the mountainous Chouf district southeast of Beirut (the pilot was rescued by the Lebanese Army).[24][25][26] The Christian Maronite Lebanese Forces militia (LF) also received from Iraq a number of Strela missiles in 1988–89.[27]

The Shiite Hezbollah guerrilla group also acquired some Strelas in the late 1980s and fired them against Israeli aircraft in November 1991.[28] Since then, they have fired many Strelas against Israeli aircraft, including two against Israeli warplanes on 12 June 2001 near Tyre, but have never scored a hit.[29]

Iraq

[edit]In the early dawn of 31 January 1991 during the Battle of Khafji in Operation Desert Storm, an Iraqi soldier shot down an American AC-130H gunship with a Strela 2, killing all 14 crewmembers.[30]

Strela-2 missiles have been used against Turkish Army helicopters by the PKK in northern Iraq. During Operation Hammer; on 18 May 1997, a Strela-2 missile was used to shoot down an AH-1W Super Cobra attack helicopter. On 4 June 1997, another Strela was used to bring down a Turkish Army AS-532UL Cougar transport helicopter in the Zakho area, killing the 11 soldiers on board.[31][32][33] The video of the first attack was used extensively for PKK propaganda and eventually released to the Internet. Greece and Serbia's intelligence services, as well as Iran, Syria, Armenia, and Cyprus were traced as possible sources of the missiles.[31][34]

A Strela-2 missile is said to have been used in April 2005, when members of the insurgents shot down an Mi-8 helicopter operated by Blackwater, killing all 11 crew members. The Islamic Army in Iraq took responsibility for the action and a video showing the downing was released on the Internet.[35] The missile launcher is not visible on the video, however, making it impossible to confirm the type of MANPADS used.

The spate of helicopter shoot-downs during 2006 and 2007 in Iraq has been partly attributed to the prevalence of the Strela amongst Sunni insurgent groups of that time;[36] while al Qaeda is said to have produced an hour-long training video on how to use SA-7s.[29]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]In late 2001, a Sudanese man with links to Al-Qaida fired an SA-7 at an American F-15 Eagle fighter taking off from Prince Sultan Air Base in Saudi Arabia. The missile missed the target and was not detected by the pilot or anyone at the base. Saudi police found the empty launcher in the desert in May 2002, and a suspect was arrested in Sudan a month later. He led police to a cache in the desert where a second missile was buried.[37]

Gaza

[edit]During October 2012, militants in Gaza fired a Strela at an IDF helicopter.[38] During Operation Pillar of Defense, Hamas released a video purporting to be a Strela missile launch at an IAF target.[39] In March 2013, one was also reportedly fired from Gaza at an IAF helicopter.[38]

In October 2023, Hamas claimed to have used these missiles to down an IAF helicopter during the Gaza war.[40]

Yemen

[edit]Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula allegedly shot down a UAE Mirage fighter jet with a Strela during the Yemeni Civil War (2014–present).[41] Houthi rebels were seen carrying 9K32 Strela-2s.[42]

Southeast Asia

[edit]

The Strela-2 system was also given to North Vietnam, where along with the more advanced Strela-2M it achieved 204 hits out of 589 firings against US and South Vietnamese aircraft between 1972 and 1975 according to Russian sources.[9] (Some sources, such as Fiszer (2004),[8] claim that it was used from 1968 onwards).

Roughly 95–120 kills and several dozen damaged are attributed to Strela-2/2M hits between April 1972 and the Fall of Saigon in April 1975, almost all against helicopters and propeller-driven aircraft. As in the War of Attrition, the missile's speed and range proved insufficient against fast jets and results were poor: only one U.S. A-4 Skyhawk, one U.S. F-4 Phantom and three South Vietnamese F-5 Freedom Fighter are known to have been shot down with Strela-2s during the conflict.

U.S. fixed-wing losses are listed in the following table.[43] The internet site Arms-expo.ru states 14 fixed-wing aircraft and 10 helicopters were shot down with 161 missile rounds used between 28 April and 14 July 1972.[9] Between April 1972 and January 1973, 29 fixed-wing aircraft and 14 helicopters were shot down (01 F-4, 7 O-1, 03 O-2, 04 OV-10, 09 A-1, 04 A-37, 01 CH-47, 04 AH-1, 09 UH-1)[44] The difference in fixed-wing losses may be at least partly due to South Vietnamese aircraft shot down by the weapon.

| Date | Type | Unit | Altitude when hit | Casualties | Mission | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ft | m | ||||||

| 1972-05-01 | O-2A | 20th TASS | 0 | FAC | Quang Tri | ||

| 1972-05-01 | A-1H | 1 SOS | 3,500 | 1,100 | 0 | SAR | Quang Tri |

| 1972-05-02 | A-1E | 1 SOS | 5,500 | 1,700 | 0 | SAR | Quang Tri |

| 1972-05-02 | A-1G | 1 SOS | 6,500 | 2,000 | 1 WIA | SAR | Quang Tri |

| 1972-05-02 | UH-1 | 5 KIA | Quang Tri[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-11 | AH-1 | 2 KIA | A Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-11 | O-2 | 2 KIA | A Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-11 | O-2 | 2 KIA | An Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-14 | O-1 | 4,000 | 1,200 | 0 | FAC | An Loc | |

| 1972-05-22 | F-4 | 0 | |||||

| 1972-05-24 | UH-1 | 4 KIA | Hue[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-24 | AH-1 | 2 KIA | An Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-25 | OV-10 | 0 | Hue[45] | ||||

| 1972-05-26 | TA-4F | H&MS-15 | 4,500 | 1,400 | 0 | armed recce | Hue |

| 1972-06-11 | OH-6 | 2 KIA | Hue[45] | ||||

| 1972-06-18 | AC-130A | 16 SOS | 12 KIA | armed recce | A Shau | ||

| 1972-06-20 | AH-1 | 2 KIA | An Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-06-21 | AH-1 | 0 | An Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-06-29 | OV-10A | 20 TASS | 6,500 | 2,000 | 1 KIA | FAC | Quang Tri |

| 1972-07-02 | O-1 | 0 | FAC | Phum Long (Cambodia) | |||

| 1972-07-05 | A-37 | 0 | Hue[45] | ||||

| 1972-07-11 | CH-53 | 46 KIA[46] | Transport | Quang Tri | |||

| 1972-10-31 | CH-47 | 15 KIA | Sai Gon[45] | ||||

| 1972-11-23 | O-2 | 0 | An Loc[45] | ||||

| 1972-03-12 | AH-1 | 0 | |||||

| 1972-12-19 | OV-10A | 20 TASS | 1 KIA | FAC | Quang Tri | ||

| 1973-01-08 | UH-1 | 6 KIA | Quang Tri[45] | ||||

| 1973-01-27 | OV-10A | 23 TASS | 6,000 | 1,800 | 2 MIA | FAC | Quang Tri |

The table shows heavy losses particularly in the beginning of May, with especially lethal results on the 1st and 2nd, where the shootdown of the O-2 FAC led to further losses when a rescue operation was attempted. After these initial losses, changes in tactics and widespread introduction of decoy flares helped to counter the threat, but a steady flow of attrition [clarification needed] and necessity of minimizing time spent in the Strela's engagement envelope nonetheless continued to limit the effectiveness of US battlefield air operations until the end of US involvement in South-East Asia. The United States lost at least 10 AH-1 Cobras and several UH-1 Hueys to Strela-2/2M hits in South East Asia.

From 28 January 1973 to July 1973, the Republic of Vietnam Air Force lost 8 aircraft and helicopter with 22 missile rounds used (1 A-37, 3 A-1, 1 F-5, 2 UH-1, 1 CH-47)[45] From January 1973 to December 1974, the Republic of Vietnam Air Force lost at least 28 planes and helicopters to Strela-2s.[13]

In 1975 spring offensive, a few dozen aircraft and helicopter were shot down by SA-7s. On 14 April, one F-5 was shot down[47] In Ho Chi Minh campaign, PAVN claimed 34 aircraft and helicopter were shot down by SA-7s, including 9 on 29 April[48]

Vietnam claims that throughout the war, PAVN gunner Hoàng Văn Quyết fired 30 missiles and shotdown 16 aircraft.[49]

In the late 1980s, Strela-2s were used against Royal Thai Air Force aircraft by Laotian and Vietnamese forces during numerous border clashes. An RTAF F-5E was damaged on 4 March 1987 and another F-5E was shot down on 4 February 1988 near the Thai-Cambodian border.

Western Asia

[edit]Afghanistan

[edit]

In 1977, the Republic of Afghanistan received the Strela-2M for use by the Afghan Army.[50] The Strela-2M was used also in Afghanistan during the Soviet–Afghan War by the Mujahiddeen. The missiles were obtained from various sources, some from Egypt and China (locally manufactured Sakr Eye and HN-5 versions of the SAM), and the CIA also assisted the guerrillas in finding missiles from other sources.

Results from combat use were not dissimilar from experiences with the Strela-2/2M from Vietnam: while 42 helicopters were shot down by various Strela-2 variants (including a few Mi-24s until exhaust shrouds made them next to invisible to the short-wavelength Strela-2 seeker) only five fixed-wing aircraft were destroyed with the weapon. Due to its poor kinematic performance and vulnerability to even the most primitive infra-red countermeasures, the guerrillas considered the Strela-2 suitable for use against helicopters and prop-driven transports, but not combat jets.

However, the recent studies and interviews after the Cold war say that most Strelas sold to the Mujahiddeen on the black market were broken/damaged or faulty. This is possibly another reason why the Soviet army in Afghanistan didn't expect working anti-aircraft missiles like the Stinger to be used.[51]

On 22 July 2007 the first reported attack of the Taliban against a coalition aircraft using MANPADS was reported. The weapon was reported to be an SA-7 allegedly smuggled from Iran to the Taliban. The missile failed after the crew of the USAF C-130, flying over the Nimroz province, launched flares and made evasive manoeuvers.[52]

However, most of the Strelas operated by al-Qaeda in Afghanistan are probably inherited from fighters that used it during the Soviet invasion. Most are probably faulty, broken or in other ways not usable (even from the beginning) against military helicopters, with the intercepts of NATO aviation by Stingers (acquired also during 80s) or other missiles.[citation needed]

Chechnya

[edit]Chechen forces had access to old Soviet stockpiles of Strela-2M and Igla missiles, as well former Soviet Army personnel trained to operate them. In the First Chechen War Russian forces lost about 38 aircraft of which 15 were caused by MANPADS with another 10 probably caused by MANPADS, while the rest were caused by other anti-aircraft weapons. During the Second Chechen war the Russians lost 45 helicopters and 8 fixed-wing aircraft, the majority presumably caused by MANPADS.[53]

Georgia

[edit]The SA-7 saw heavy usage by all sides during the Georgian Civil War. The first known loss to an SA-7 happened on 13 June 1993, when a GAF Su-25 was shot down by a Strela over Shubara. On two later occasions, Georgian airliners (a Tu-134A and a Tu-134B) were shot down by SA-7s, killing a total of 110 people.[54]

Africa

[edit]Guinea-Bissau

[edit]PAIGC rebels fighting for independence from Portugal began to receive SA-7s in early 1973, a development that immediately became a threat to Portuguese air supremacy. On 23 March 1973, two Portuguese Air Force (FAP) Fiat G.91s were shot down by SA-7s, followed six weeks later by another Fiat, and a Dornier Do 27.[55]

Mozambique

[edit]FRELIMO fighters in Mozambique were also able to field some SA-7s with Chinese support, although the weapon is not known to have caused any losses to the FAP, even if it forced Portuguese pilots to change their tactics. In one case a Douglas DC-3 carrying foreign military attaches and members of the senior Portuguese military command was hit by an SA-7 in one of the engines. The crippled plane managed to land safely and was later repaired.[56]

Angola

[edit]In Angola and Namibia, SA-7s were deployed against the South African Air Force with limited success. The SAAF lost Atlas Impalas to Strelas on 24 January 1980 and 10 October 1980. Another Impala was hit by an SA-7 on 23 December 1983, but the pilot was able to fly the aircraft back to Ondangwa AB.[57] UNITA also reportedly obtained 50 SA-7s that Israel had captured, via the CIA. The first one was fired at Cuban aircraft by a French mercenary on 13 March 1976, but the missile failed to hit the target. The individual missiles may have been in poor condition, as none scored a direct hit.[58] Additionally, it is claimed that UNITA used SA-7s to shoot down two Transafrik International Lockheed L-100-30 Hercules flying UN charters, on 26 December 1998[59] and 2 January 1999,[60] both near Huambo.[61]

Sudan

[edit]Using an SA-7, the Sudan People's Liberation Army shot down a Sudan Airways Fokker F-27 Friendship 400M taking off from Malakal on 16 August 1986, killing all 60 on board.[62] On 21 December 1989, an Aviation Sans Frontières Britten-Norman BN-2A-9 Islander (F-OGSM) was shot down by an SA-7 while taking off from Aweil Sudan, killing the four crew on board.[62]

Western Sahara

[edit]The Polisario Front used SA-7s against the Royal Moroccan Air Force and Mauritanian Air Force during the Western Sahara War over the former Spanish colonies of the Spanish Sahara. The Mauritania Air Force lost a Britten-Norman Defender to a SA-7 fired by the Polisario on 29 December 1976.[63] Between 1975 and 1991, the Royal Moroccan Air Force has lost several Northrop F-5A Freedom Fighters and Dassault Mirage F1s to SA-7s fired by the Polisario.[64] In a case of mistaken identity, a Dornier 228 owned by the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research was shot down over the Western Sahara near Dakhla on 24 February 1985. Two Dornier 228s named Polar 2 and Polar 3 were on a return flight to Germany following a South Pole expedition. After having taken off from Dakar, Senegal, en route to Arrecife, Canary Islands, flying 5 minutes behind Polar 2 and at a lower altitude of 2,700 m (9,000 ft), Polar 3 was shot down by a SA-7 fired by the Polisario.[65] The crew of three was killed. In another incident, on 8 December 1988, two Douglas DC-7CFs flying at 3,400 m (11,000 ft) from Dakar, Senegal to Agadir, Morocco for a locust control mission there, had SA-7s fired at them by the Polisario. One aircraft, N284, was hit and lost one of its engines and part of a wing. This led to the aircraft crashing, killing the crew of five.[66] The other aircraft, N90804, also was hit and lost an engine along with suffering other damage, but it was able to land safely at Sidi Ifni Morocco.[66]

Airliner attacks

[edit]During the Rhodesian Bush War, members of the military wing of the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army brought down two Vickers Viscount civilian airliners near Kariba; the first in September 1978, the second in February 1979. There was great loss of life in both instances as the flights were returning from a well known tourist attraction.[67]

- Vickers Viscount, Flight RH825, 3 September 1978 – downed by a Strela missile near Kariba Dam. After initial impact, the pilot was able to make an emergency landing in a nearby field but the aircraft broke up on impact. Eighteen of the fifty-six passengers in the tail section survived the crash. Ten of these survivors were shot dead at the crash-site by insurgents, who later looted the bodies and wreckage.[67]

- Vickers Viscount, Flight RH827, 12 February 1979 – shot by down Strela missile near Kariba Dam; all 59 people on board were killed.

UNITA claimed that they used one to shoot down a TAAG Boeing 737-2M2 taking off from Lubango on 8 November 1983.[68] A Lignes Aériennes Congolaises Boeing 727-30 taking off from Kindu was shot down by an SA-7 fired by rebel forces in 1998, killing all 41 on board.[68] Two missiles were fired at a Boeing 757 during the 2002 Mombasa attacks in Kenya. Neither missile struck its target.[69][70]

Latin America

[edit]Argentina

[edit]Strela-2M missiles were available to Argentinian troops in the Falkland Islands during the Falklands War. War Machine Encyclopedia shows no records of any launches, but several missiles were captured.[71]

Nicaragua

[edit]The Strela-2 was used by both Sandinista government forces and US-backed Contra insurgents during the 1979–1990 civil war.

On 3 October 1983, at about 10:00 am, Sandinista soldier Fausto Palacios used a Strela to shoot down a Contra-operated Douglas DC-3 that had taken off from Catamacas airport in Honduras, carrying supplies, over the area of Los Cedros, in the Nueva Segovia Department. One crewman died in the crash and four were captured by government forces. The pilot, Major Roberto Amador Alvarez, as well as his co-pilot Capt. Hugo Reinaldo Aguilar were former members of the extinct National Guard of the former dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle.[72][73][74]

On 27 August 1984, Sandinista soldier Fanor Medina Leyton shot down a Contra-operated Douglas C-47 Skytrain with a Strela. Sources differ over the attack and crash area: both a Russian source and Sandinista officials reported the Jinotega Department, while the Aviation Safety Network reports the Quilalí area in the Nueva Segovia department. All eight occupants were killed. The pilot, José Luis Gutiérrez Lugo, was reported as a former pilot for the Somoza family. Sandinista and Contra forces subsequently battled for the control of six packages dropped from the plane.[72][75][76]

On 5 October 1986 a Corporate Air Services C-123 Provider (HPF821, previously N4410F and USAF 54-679, (c/n 20128))[77] conducting a covert drop of arms to Contra fighters in Nicaragua was shot down by Sandinista soldier José Fernando Canales Alemán, using an SA-7. CIA pilots William J. Cooper and Wallace "Buzz" Sawyer as well as radio operator Freddy Vilches were killed in the crash. Loadmaster Eugene Hasenfus parachuted to safety and was taken prisoner. He was later released in December 1986.[78] The flight had departed Ilopango Airport, El Salvador loaded with 70 Soviet-made AK-47 rifles and 100,000 rounds of ammunition, rocket grenades and other supplies.[79]

On 15 June 1987, a Contra-operated Beechcraft Baron 56TC (reg. N666PF, msn. TG-60) was hit by Sandinista anti-aircraft fire over the Nueva Segovia Department. The (formerly civilian) light utility aircraft, which was removed from the US registry two years before,[citation needed] and was reportedly modified to carry rockets for use in an air-to-ground light strike role, was downed after an attack that reportedly included dropping leaflets and, possibly, reconnaissance.[80][81][82] The aircraft crashed 6 km (4 mi) inside Honduras, in an area known as Cerro El Tigre and its three occupants, all former military elements of the Somoza dictatorship, were injured and captured after the crash landing and were treated in Honduras.[83] The pilot, Juan Gomez, a former colonel in Somoza's National Guard was also reported to be the head of the Contra air force.[84] A Russian source credits the Baron's downing to an Strela-2 fired from Murra by Sandinista soldier Jose Manuel Rodriguez.[82][85]

El Salvador

[edit]FMLN rebels acquired SA-7 missiles around 1989 and employed them extensively in the closing years of the Salvadoran Civil War, dramatically increasing the combat losses of Salvadoran Air Force aircraft. At least two O-2 Skymasters (on 26 September and 19 November 1990), one A-37 Dragonfly (on 23 November 1990), two Hughes 500 helicopters (2 February and 18 May 1990), and two UH-1Hs were lost to SA-7s. One of the UH-1Hs (on 2 January 1991) was crewed by US Army personnel, while the other was operated by the Honduran Air Force.[86][87]

Colombia

[edit]In late December 2012, a video showing FARC rebels attempting to shoot down a Colombian Air Force Arpía helicopter with an SA-7 in the Cauca raised the alarm in the Colombian military, though the missile failed.[88][89] During that same month, a Strela was captured by the Colombian military. It is believed that they might came from Cuba, Nicaragua or Peru; the only Latin American operators of the type.[90]

Furthermore, the CIA's motive to remove and destroy Chinese copies of the SA-7 (HN-5s) from Bolivia in 2005 was the fear of them reaching FARC rebels because, according to a US military magazine, "they used the HN-5 against Colombian-operated U.S-made helicopters".[91] The Ecuadorian Army captured an HN-5 allegedly destined for the FARC in the border province of Sucumbíos, near Colombia, in July 2013.[92][93]

Europe

[edit]Bosnia

[edit]The Army of Republika Srpska, backed by the Armed Forces of Serbia and Montenegro, used Strela-2M and upgraded Strela-2M/A missiles against Bosnian, Croatian, and NATO forces. On 3 September 1992, an Italian Air Force G.222 transport was presumably shot down by an Strela-2M during a United Nations relief mission near Sarajevo. Serbian forces shot down a Croatian Air Force MiG-21 in September 1993 with a Strela-2M. On 17 December 1994, a French Navy Dassault Étendard IVP was hit by a Strela-2M, but managed to return to its carrier.[94]

During Operation Deliberate Force, NATO pilots were instructed to fly in medium altitudes to avoid Bosnian Serb MANPADS, such as the Strela-2 and the more modern Igla, although on 30 August 1995 a French Air Force Mirage 2000N was shot down by a Bosnian Serb MANPADS and its crew captured, the only aircraft lost during the campaign due hostile fire.[94]

Northern Ireland

[edit]The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) acquired some missiles from Libya. One was reported to have been fired at a British Army Air Corps Lynx helicopter in July 1991 in South Armagh; however, it missed its target.[95] To counter the new threat, the British helicopters flew in pairs below 15 meters (50 feet) or above 150 meters (500 feet).

Spain

[edit]In 2001, the Basque separatist group ETA tried on three occasions (29 April, 4 and 11 May) to use Strela 2 missiles to shoot down the Dassault Falcon 900 aircraft with the then-Spanish Prime Minister Jose Maria Aznar on board. The attempts, which were made near the Fuenterrabía and Foronda airports, were unsuccessful as each time the missiles failed to launch. In 2004, several systems were captured by the Civil Guard.[96] Some Strela 2 missiles were bought from the IRA in 1999, while Libya was tracked as the original source used by the IRA.[97]

Ukraine

[edit]During the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Germany reversed its ban on weapon sales to provide Ukraine with military support.[98] On 23 March 2022, German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock confirmed the delivery of 500 Strela-2 missiles which were part of former East German arsenals.[99]

Versions

[edit]- 9K32M Strela-2M: "SA-7b Grail"

- Fasta-4M: East German variant consisting 4 Strela-2Ms mounted to a fully rotating turret. used by the NVA and Volksmarine

- Strela 2M/A: Yugoslav upgraded version with larger warhead

- CA-94 and CA-94M: Romanian license-built versions of the 9K32 and 9K32M, respectively

- HN-5: Chinese unlicensed copy

- Anza Mk-I: Pakistani version based on SA-7.[100]

- Ayn al Saqr (عين الصقر; "Hawk Eye"): Egyptian copy[101]

- Hwasung-Chong: North Korean license-built copy of Egyptian Ayn al Saqr system[5]

Operators

[edit]

Current operators

[edit] Al-Nasser Salah al-Deen Brigades[102]

Al-Nasser Salah al-Deen Brigades[102] Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula[103]

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula[103] al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb[103]

al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb[103] Al-Shabaab[104]

Al-Shabaab[104] Algeria[105]

Algeria[105]- Alliance for National Resistance[106]

Angola[105]

Angola[105] Azerbaijan[105]

Azerbaijan[105] Benin[5]

Benin[5] Boko Haram[104]

Boko Haram[104] Botswana[105]

Botswana[105] Bulgaria[105] license-built[5]

Bulgaria[105] license-built[5] Burkina Faso[105]

Burkina Faso[105] Burundi[105]

Burundi[105] Cambodia[107]

Cambodia[107] Cape Verde[5]

Cape Verde[5] Chad[5]

Chad[5] Cuba[105]

Cuba[105] Czech Republic[105]

Czech Republic[105] Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda: 2 systems[108]

Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda: 2 systems[108] Democratic Republic of the Congo[105]

Democratic Republic of the Congo[105] Ecuador[105]

Ecuador[105] Egypt[105]

Egypt[105] El Salvador[109]

El Salvador[109] Eritrea[105]

Eritrea[105] Ethiopia[105]

Ethiopia[105] Free Syrian Army[105]

Free Syrian Army[105] Georgia[105]

Georgia[105] Ghana[105]

Ghana[105] Guinea[105]

Guinea[105] Guinea-Bissau[105]

Guinea-Bissau[105] Guyana[107]

Guyana[107] Hamas[104]

Hamas[104]- Popular Resistance Committees[104]

Hezbollah[104]

- Hizbul Mujahideen[103]

Houthis[42][110]

Houthis[42][110] India[105]

India[105] Indonesia[111][112][113]

Indonesia[111][112][113] Iran[105]

Iran[105] Islamic State[103]

Islamic State[103] Ivory Coast[105]

Ivory Coast[105]- Jaish al-Islam[114]

Kazakhstan[5]

Kazakhstan[5] Kurdistan[115]

Kurdistan[115] Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)[31][116]

Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK)[31][116] Kuwait[107]

Kuwait[107] Kyrgyzstan[105]

Kyrgyzstan[105] Laos[105]

Laos[105] Lebanon[105]

Lebanon[105] Libya[117]

Libya[117]- Lord's Resistance Army[103]

Mali[5]

Mali[5] March 23 Movement[118][119]

March 23 Movement[118][119] Mauritania[105]

Mauritania[105] Mauritius[5]

Mauritius[5] Moldova[5]

Moldova[5] Mongolia[120][107]

Mongolia[120][107] Morocco[117]

Morocco[117] Mozambique[107]

Mozambique[107] Namibia[105]

Namibia[105] New People's Army[121]

New People's Army[121] Nicaragua[105]

Nicaragua[105] Nigeria[105]

Nigeria[105] North Korea[105]

North Korea[105] Oman[105]

Oman[105] Palestinian Islamic Jihad[103] (also known as al-Quds Brigades)

Palestinian Islamic Jihad[103] (also known as al-Quds Brigades) Peru[105]

Peru[105]- Popular Defense Forces[122]

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command[105]

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command[105]- Popular Front for the Rebirth of Central African Republic (FPRC)[123]

- Popular Mobilization Units[124]

Qatar[105]

Qatar[105]- Rally of Democratic Forces[103]

Rapid Support Forces[125][126][better source needed][127]

Rapid Support Forces[125][126][better source needed][127] Romania[107]

Romania[107] Russia[105]

Russia[105] Rwanda[105]

Rwanda[105] Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic[128]

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic[128] Serbia[105]

Serbia[105] Seychelles[107]

Seychelles[107] Sierra Leone[117]

Sierra Leone[117] Slovakia[105]

Slovakia[105] Somalia[107]

Somalia[107] Somaliland[103]

Somaliland[103] South Sudan[105]

South Sudan[105] South Sudan Liberation Movement[104]

South Sudan Liberation Movement[104] Sudan[105]

Sudan[105] Sudan Revolutionary Front[103]

Sudan Revolutionary Front[103] Syria[105]

Syria[105] Tajikistan[105]

Tajikistan[105] Tanzania[105]

Tanzania[105] Tunisia[5]

Tunisia[5] Turkmenistan[105]

Turkmenistan[105] Uganda[105]

Uganda[105] Ukraine[105]

Ukraine[105] United Arab Emirates[117]

United Arab Emirates[117] United Wa State Army[103]

United Wa State Army[103] Uzbekistan[5]

Uzbekistan[5] Vietnam[105]

Vietnam[105] Yemen[107]

Yemen[107] Zambia[105]

Zambia[105] Zimbabwe[105]

Zimbabwe[105]

Former operators

[edit] Afghanistan[5]

Afghanistan[5] Afghan Mujahideen[129]

Afghan Mujahideen[129] African National Congress[107]

African National Congress[107] Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a[104]

Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a[104] Ansar al-Islam[130]

Ansar al-Islam[130] Ansar al-Sharia (Libya)[131]

Ansar al-Sharia (Libya)[131] Argentina[71]

Argentina[71]- Armed Forces Revolutionary Council[104]

Army of Republika Srpska[94][132]

Army of Republika Srpska[94][132] Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina[133]

Army of the Republic of Serb Krajina[133] Al-Mourabitoun[22]

Al-Mourabitoun[22] Belarus: Phased out from active service. 29 disposed of[134]

Belarus: Phased out from active service. 29 disposed of[134]- Black September Organization[135]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[132]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[132] Caucasus Emirate[103]

Caucasus Emirate[103]- Chadian Union of Forces for Democracy and Development[103]

Chechen Republic of Ichkeria[53]

Chechen Republic of Ichkeria[53] CNRDR[104]

CNRDR[104] Contras[136]

Contras[136] Croatia[5]

Croatia[5] Cyprus[117]

Cyprus[117] Czechoslovakia[107]

Czechoslovakia[107] East Germany[107]

East Germany[107] ETA[104]

ETA[104]- FAN[121]

Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)[86]

Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)[86] FARC[103]

FARC[103] Finland: Strela-2M operated under designation 'ItO-78'[107]

Finland: Strela-2M operated under designation 'ItO-78'[107] Frelimo[56]

Frelimo[56] Germany: Former East German stocks. 2,700 Strela-2s were donated to Ukraine in response to the 2022 Russian invasion[137][138]

Germany: Former East German stocks. 2,700 Strela-2s were donated to Ukraine in response to the 2022 Russian invasion[137][138] Harkat ul-Ansar[104]

Harkat ul-Ansar[104] Hungary[107]

Hungary[107] Iraq[103]

Iraq[103]- Islamic Army in Iraq[35]

Islamic Courts Union[104]

Islamic Courts Union[104] Islamic State in Libya[139]

Islamic State in Libya[139] Islamic State – Sinai Province[140]

Islamic State – Sinai Province[140]- Jaish al-Haramoun[141]

Jamiat-e Islami[104]

Jamiat-e Islami[104] Jordan[5]

Jordan[5]- Jumbish-e-Mili[104]

- Justice and Equality Movement[142][143]

Khmer People's National Liberation Front[121]

Khmer People's National Liberation Front[121] Khmer Rouge[121]

Khmer Rouge[121] Kosovo Liberation Army[104]

Kosovo Liberation Army[104]- Kurdistan Democratic Party

Kuwait[144]

Kuwait[144] Latvia: 5 Strela 2M in 2008[145]: 136

Latvia: 5 Strela 2M in 2008[145]: 136  Lebanese Forces[146]

Lebanese Forces[146] Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam[104]

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam[104]- Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy[104]

Moro National Liberation Front[121]

Moro National Liberation Front[121] Mozambique National Resistance[121]

Mozambique National Resistance[121] Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa[104]

Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa[104]- Mujahideen Shura Council of Derna[147]

National Congress for the Defense of the Congolese People[104]

National Congress for the Defense of the Congolese People[104] National Liberation Army (Macedonia)[104]

National Liberation Army (Macedonia)[104] National Liberation Movement (Albania)[148]

National Liberation Movement (Albania)[148]- National Redemption Front[149]

- Niger Movement for Justice[104]

North Macedonia: 54 in 2008[145]: 179

North Macedonia: 54 in 2008[145]: 179  North Vietnam[9]

North Vietnam[9] National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad[103]

National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad[103] North Yemen[107]

North Yemen[107] PAIGC[55]

PAIGC[55] Palestinian Authority[104]

Palestinian Authority[104] Palestine Liberation Organization factions in Lebanon;[21] likely As-Sa'iqa[150]

Palestine Liberation Organization factions in Lebanon;[21] likely As-Sa'iqa[150]- Patriotic Movement of Côte d'Ivoire[104]

People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola[151]

People's Armed Forces of Liberation of Angola[151] People's Liberation Army (Lebanon)[16]

People's Liberation Army (Lebanon)[16] People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola[152]

People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola[152] Poland: Used until 2018[153]

Poland: Used until 2018[153] Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf[154]

Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf[154] Provisional Irish Republican Army[104]

Provisional Irish Republican Army[104] Republic of the Congo[155]

Republic of the Congo[155] Revolutionary United Front[104]

Revolutionary United Front[104] Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat[104]

Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat[104] Sandinista National Liberation Front[72]

Sandinista National Liberation Front[72] São Tomé and Príncipe[155]

São Tomé and Príncipe[155] Shan State Army[103]

Shan State Army[103] Slovenia[5]

Slovenia[5]- Somali National Alliance[104]

- Somali Salvation Alliance[104]

South Africa[117]

South Africa[117] South Yemen[107]

South Yemen[107] Soviet Union[156]

Soviet Union[156] Sudan People's Liberation Army:[104] Incorporated into the South Sudan government

Sudan People's Liberation Army:[104] Incorporated into the South Sudan government Tahrir al-Sham[105]

Tahrir al-Sham[105] UNITA[58]

UNITA[58] Viet Cong[107]

Viet Cong[107] White mercenaries in the Congo[157]

White mercenaries in the Congo[157] Yugoslavia[107]

Yugoslavia[107] Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army[67]

Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army[67]

Bibliography

[edit]- Cullen, Tony; Foss, Christopher F., eds. (1992). Jane's Land-Based Air Defence 1992–93 (5th ed.). Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Data Division. ISBN 0-7106-0979-5.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (19 January 2023). Infantry Antiaircraft Missiles: Man-Portable Air Defense Systems. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-5345-5.

References

[edit]- ^ Efrat, Moshe (1983). "The Economics of Soviet Arms Transfers to the Third World. A Case Study: Egypt". Soviet Studies. 35 (4): 437–456. doi:10.1080/09668138308411496. ISSN 0038-5859. JSTOR 151253.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Переносной зенитно-ракетный комплекс 9К32М "Стрела-2М"". New-factoria.ru. Archived from the original on 11 October 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Зенитная управляемая ракета 9М32М | Ракетная техника". New-factoria.ru. 14 November 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ James C. O'Halloran. Jane's Land Based Air Defence 2005–2006 (10th ed.). Jane's Information Group, London.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Dr. Michael Ashkenazi; Princess Mawuena Amuzu; Jan Grebe; Christof Kögler; Marc Kösling (February 2013). "MANPADS: A Terrorist Threat to Civilian Aviation?" (PDF). Bonn International Center of Conversion (BICC) – Internationales Konversionszentrum Bonn GmbH. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ Twentieth Century Artillery (ISBN 1-84013-315-5), 2000, Ian Hogg, Chapter 6, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d Lappi, Ahti: Ilmatorjunta Kylmässä Sodassa, 2003

- ^ a b c d On arrows and needles: Russia's Strela and Igla portable killers. Journal of Electronic Defense, January 2004. Michal Fiszer and Jerzy Gruszczynski

- ^ a b c d e ""Стрела-2" (9К32, SA-7, Grail), переносный зенитный ракетный комплекс — ОРУЖИЕ РОССИИ, Информационное агентство". Arms-expo.ru. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b c War Machine, issue 64 (magazine), 1984, Orbis Publications, p. 1274.

- ^ a b "SA-7 "Grail" (9K32 "Strela-2")". bellum.nu. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Cullen & Foss 1992, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e Cullen & Foss 1992, p. 42.

- ^ a b c "China's Search for Air Defense: On the Verge of Foreign Acquisitions?" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 8 April 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, David D. (27 January 2014). "Militants Down Egyptian Helicopter, Killing 5 Soldiers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d Tom Cooper & Eric L. Palmer (26 September 2003). "Disaster in Lebanon: US and French Operations in 1983". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b Micah Zenko (13 February 2012). "When America Attacked Syria". Politics, Power, and Preventive Action. Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b "2005". Ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Chivers, C.J. (24 July 2013). "The Risky Missile Systems That Syria's Rebels Believe They Need". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Chivers, C. J.; Schmitt, Eric; Mazzetti, Mark (21 June 2013). "In Turnabout, Syria Rebels Get Libyan Weapons". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ a b See US State Department Cable Beirut 7015, 20 June 1974.

- ^ a b Samer Kassis, Invasion of Lebanon 1982, Abteilung 502, 2019, p. 196. ISBN 978-84-120935-1-3

- ^ Ken Guest, Lebanon, in Flashpoint! At the Front Line of Today's Wars, Arms and Armour Press, London 1994, p. 106. ISBN 1-85409-247-2 This source reports on the loss of an American-made F-16, though the plane was actually an Israeli-made Kfir.

- ^ "Israeli Plane Shot Down by Surface-to-air Missiles over Lebanon". 21 November 1983.

- ^ "Israelis Bomb Lebanese Sites, Lose One Plane". The Washington Post. 21 November 1983. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Friedman, Thomas L. (21 November 1983). "Israeli Jets Bomb Palestinian Bases In Lebanon Hills – The New York Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Samer Kassis, 30 Years of Military Vehicles in Lebanon, Beirut: Elite Group, 2003, p. 36. ISBN 9953-0-0705-5

- ^ Nicolas Blanford (2011) Warriors of God: Inside Hezbollah's Thirty-Year Struggle Against Israel. New York: Random House.

- ^ a b "Terrorists known to possess SAMs". CNN. 28 November 2002. Archived from the original on 22 March 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Spirit 03 and the Battle for Khafji". Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b c "Netzwerk Friedenskooperative – Themen – Türkei/Kurdistan-Invasion – turkhg52". Friedenskooperative.de. 6 June 1997. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident 04-JUN-1997 Aérospatiale AS 532UL Cougar 140". Aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Sabah Politika Haber". Arsiv.sabah.com.tr. Archived from the original on 23 October 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Rebel Missiles Could End Up Being a Nightmare for Turkey – Al-Monitor: the Pulse of the Middle East". Al-Monitor. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b John F. Burns (23 April 2005). "Video Appears to Show Insurgents Kill a Downed Pilot". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Why are U.S. helicopters getting shot down in Iraq? | FP Passport". Blog.foreignpolicy.com. 19 February 2007. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Traces of Terror: The Dragnet; Sudanese Says He Fired Missile at U.S. Warplane". New York Times. 14 June 2002. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ a b Harel, Amos (16 October 2012). "For first time, Palestinians in Gaza fire missile at IAF helicopter Israel News Broadcast". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Small Arms, Big Problems – By Damien Spleeters". Foreign Policy. 19 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "The Al-Qassam Brigades of Hamas are claiming to have Targeted and Struck an Israeli Helicopter operating to the East of the Al-Buriej Camp in Southern Gaza with a 9K32 "Strela-2" Man-Portable Air Defense System; so far there has been No Statement from the IDF on any such Incident". X (formerly Twitter). Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda Brought Down Jet With Surface-to-Air Missile – iHLS Israel Homeland Security". i-hls.com. 4 April 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ a b "YouTube". youtube.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Vietnam Air Losses, Christopher Hobson, 2002

- ^ Dân Trí (2 May 2015). "Người Nga nói thật về Chiến tranh Việt Nam | Báo Dân trí". Dantri.com.vn. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Strela – 'Nỏ thần' gây khiếp đảm trên chiến trường Việt nam". 17 July 2013.

- ^ Melson, Charles D.; Arnold, Curtis G. (1991). U.S. Marines in Vietnam, The war that would not end, 1971-1973 (PDF). History and Museums Division, U.S. Marine Corps. PCN 190 003112 00.

- ^ Ý kiến của bạn. "Hạ gục F-5". Sknc.qdnd.vn. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Ngày cuối bi thảm của Không quân Việt Nam Cộng hòa". Soha.vn. 24 November 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ "Kỷ lục đỉnh cao suốt 50 năm nay trong lịch sử phòng không thế giới". 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977–1980, Volume XII, Afghanistan". history.state.gov.

- ^ "Roads of terror", ep. 1 Planete documentary film

- ^ Coghlan, Tom (28 July 2007). "Taliban in first heat-seeking missile attack". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b Zaloga 2023, p. 74.

- ^ "CIS region – Авиация в локальных конфликтах – www.skywar.ru". skywar.ru. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

- ^ a b CMS [dead link]

- ^ a b CMS [dead link]

- ^ Angola: Claims & Reality about SAAF Losses Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b Angola since 1961 Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2016-01-19 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2016-01-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Man-Portable Air Defence Systems Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Morocco, Mauritania & West Sahara since 1972 Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Western Sahara war 1975–1991 Archived 2011-10-04 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2012-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2016-02-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Anthony Trethowan (2008). Delta Scout: Ground Coverage operator (2008 ed.). 30deg South Publishers. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-920143-21-3.

- ^ a b Criminal Occurrence description Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- ^ "Proliferation of MANPADS and the threat to civil aviation". Archived from the original on 1 March 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Bolkcom; Elias; Feickert. "MANPADs Threat to Commercial Aviation" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ a b War Machine, Italian version printed by De Agostini, Novara, 1983, p.155

- ^ a b c "Nicaragua – Авиация в локальных конфликтах – www.skywar.ru". Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Nicaragua Reports Shooting Down Rebel DC-3 Registered in Oklahoma". NewsOK.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Daily News – Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (29 August 1984). "Nicaragua says it downed a rebel supply plane". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Omang, Joanne, and Wilson, George C., "Questions About Plane's Origins Grow", The Washington Post, 9 October 1986, pages A-1, A-32.

- ^ "Intrusions, Overflights, Shootdowns and Defections During the Cold War and Thereafter". Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "ASN Aircraft accident Fairchild C-123K Provider HPF821 San Carlos". 5 October 1986. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Branigin, William (25 June 1987). "Contras Said to Break Up Sandinista Spy Network". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Tyroler, Deborah (19 June 1987). "Contra Aircraft Downed By Sandinistas; Nicaraguan Government Identifies Three-man Crew". University of New Mexico Digital Repository. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Авиация Контрас - Авиация в локальных конфликтах - www.skywar.ru". www.skywar.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Tyroler, 1987

- ^ Tyroler, 19 June 1987

- ^ "Nicaragua - Авиация в локальных конфликтах - www.skywar.ru". www.skywar.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ a b Cooper, Tom. "El Salvador, 1980–1992". ACIG.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ "Blog de las Fuerzas de Defensa de la República Argentina: Conflictos americanos: El factor aéreo en El Salvador, 1980–1992 (2/2)". Fdra.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Misiles tierra-aire SA-7 en posesión de las FARC – Analisis 24". 7 April 2013. Archived from the original on 7 April 2013.

- ^ "Misiles Antiaéreos en Poder de las FARC. MANPAD SA-7 Strela". YouTube. 9 December 2012. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Incautado Misil Antiaéreo SA-7 "Grail" a las FARC, en el Departamento del Cauca ~ WebInfomil". Webinfomil.com. December 2012. Archived from the original on 7 June 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Revista dice que misiles chinos eran efectivos". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Ejercito Ecuatoriano incauta misil antiaéreo destinado a las FARC ~ Webinfomil". 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Militares ecuatorianos descubren un misil cerca de la frontera con Colombia". YouTube. Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Zaloga 2023, p. 73.

- ^ Jackson, Brian A., et al. Aptitude for Destruction, Volume 2: Case Studies of Organizational Learning in Five Terrorist Groups, Volume 2 Rand Corporation, 5 May 2005, pg. 110.

- ^ "ETA quiso atentar con misiles contra Aznar en 2001". Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ Govan, Fiona (18 January 2010). "Spanish PM 'saved' by faulty IRA missile". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Germany reverses ban on weapon sales to Ukraine — as it happened". DW. 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Deutschland sendet weitere »Strela«-Raketenwerfer in die Ukraine". Spiegel. 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Anza Mk-I Mk-II Mk-III Man- Portable air defense missile system". armyrecognition.com. 8 May 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ^ "ÇáäŮÇă ÇáŐÇŃćÎě Úíä ŐŢŃ". Aoi.com.eg. Archived from the original on 16 February 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Number of Gaza terror groups possess Strela 2 MANPADS". FDD's Long War Journal. 25 September 2013. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Armed Actor Research Notes: Armed Groups' Holding of Guided Light Weapons. Number 31, June 2013" (PDF). Small Arms Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Guided light weapons reportedly held by non-state armed groups 1998–2013" (PDF). Small Arms Survey. March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) (14 February 2018). "The Military Balance 2018". The Military Balance. 118.

- ^ "Chad rebels say destroyed army helicopter gunship". Reuters. 19 January 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Trade Register". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Small Arms Survey (2015). "Waning Cohesion: The Rise and Fall of the FDLR–FOCA" (PDF). Small Arms Survey 2015: weapons and the world (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. 203. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ "Defense & Security Intelligence & Analysis: IHS Jane's | IHS". Janes.com. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Oryx on Twitter". Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "KESATRIA ELANG PERKASA GELAR LATIHAN PERTAHAN UDARA KOMPOSIT". tnial.mil.id (in Indonesian). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "Strela – Rudal Pemburu Panas Andalan Korvet Parchim dan Arhanud Korps Marinir". indomiliter.com (in Indonesian). 4 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "AL-1M: Wujud Reinkarnasi Rudal Strela dengan Proximity Fuse". indomiliter.com (in Indonesian). 2 October 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "MENASTREAM on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 2016). The Military Balance 2016. Vol. 116. Routledge. p. 492. ISBN 9781857438352.

- ^ "Turan Oguz on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas W. Zarzecki, (2002). Arms Diffusion: The Spread of Military Innovations in the International System. Routledge ISBN 0415935148

- ^ "The UN Intervention Brigade: A Force for Change in DR Congo?".

- ^ "L'Avenir : «Kigali dote le M23 de 450 combattants et de trois missiles SAM 7»". 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Mongolian Army". 2 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Cullen & Foss 1992, p. 43.

- ^ "Sudan Country Report 2015" (PDF). Asylum Research Centre. 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ Aurélien Llorca, Mélanie De Groof, Paul-Simon Handy, Ruben de Koning, and Reyes Aragón (21 December 2015). "Letter dated 21 December 2015 from the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2196 (2015) addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF). Letter to President of the Security Council.

{{cite press release}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Iraq: Turning a blind eye: The arming of the Popular Mobilization Units" (PDF). Amnesty International. 5 January 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Wagner Group supplies air defense missiles to Sudan's Rapid Support Fo". 30 May 2023.

- ^ https://x.com/HammerOfWar5/status/1881083584234295360?mx=2 [better source needed]

- ^ "UN Sudan Panel Final Report 2023" (PDF). United Nations. 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2025 – via The Guardian.

- ^ Mitzer, Stijn; Oliemans, Joost (15 December 2021). "Desert Storm: Listing The Polisario's Inventory of AFVs". Oryx.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies (1989). The Military Balance, 1989-1990. London: Brassey's. p. 153. ISBN 978-0080375694.

- ^ "Syria war: Rebel group supplied with anti-air missiles". Middle East Eye. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Alex Mello on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (2004). Langton, Christopher (ed.). The Military Balance 2004/2005. Oxford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-19-856622-9.

- ^ Bosnia Country Handbook: Peace Implementation Force (IFOR). Department of Defense. 1995. pp. 13–9. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ "Белоруссия полностью утилизировала ПЗРК "Стрела-2М" — ОРУЖИЕ РОССИИ, Информационное агентство". Arms-expo.ru. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ Sean K. Anderson with Stephen Sloan (2009). Historical Dictionary of Terrorism. HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF WAR, REVOLUTION, AND CIVIL UNREST. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 86.

- ^ "Struggle for Nicaragua: escalation" (PDF). 10 December 1985. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Germany to ship anti-aircraft missiles to Ukraine – DW – 03/03/2022". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "German minister says further Strela missiles are on way to Ukraine". Reuters. 23 March 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ "Oded Berkowitz on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "MENASTREAM on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Sami on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ United Nations Security Council (11 November 2008). "Report of the Panel of Experts established pursuant to resolution 1591 (2005) concerning the Sudan" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ Claudio Gramizzi; Jérôme Tubiana (July 2012). "Forgotten Darfur: Old Tactics and New Players" (PDF). HSBA Working Paper 28. Small Arms Survey. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ Mitzer, Stijn; Oliemans, Joost (22 December 2020). "The Forgotten Deterrent: Kuwait's Luna-M 'FROG-7' Artillery Rockets". Oryx Blog.

- ^ a b International Institute for Strategic Studies (5 February 2008). The Military Balance. 2008. Routledge. ISBN 978-1857434613.

- ^ Samer Kassis, 30 Years of Military Vehicles in Lebanon, Beirut: Elite Group, 2003. ISBN 9953-0-0705-5 p. 36.

- ^ "MENASTREAM on Twitter". Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ PROSECUTOR v. LJUBE BOŠKOSKI JOHAN TARČULOVSKI, Case No. IT-04-82-T (United Nations International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the Former Yugoslavia since 1991 10 July 2008).

- ^ "Sudan's Plan for Darfur Involves Its Own Force, Not the U.N.'s". The New York Times. 22 August 2006. Archived from the original on 28 January 2025. Retrieved 9 June 2025.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency (27 April 1974). "Palestinians in Lebanon Reportedly receive SA-7s" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ Jaster, Robert Scott (1997). The Defence of White Power: South African Foreign Policy under Pressure. Basingstoke: Palgrave-Macmillan. pp. 66–68, 93–103. ISBN 978-0333454558.

- ^ Geraint Hughes, My Enemy's Enemy: Proxy Warfare in International Politics. Sussex Academic Press, 2014. p. 73.

- ^ Dmitruk, Tomasz (2018), "Dwie dekady w NATO. Modernizacja techniczna Sił Zbrojnych RP [3]" [Two decades in NATO. Technical modernization of Polish Armed Forces [3]], www.magnum-x.pl (in Polish), archived from the original on 16 June 2021

- ^ Jeapes, Tony (1980). SAS Operation Oman. London: William Kimber. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-7183-0018-0.

- ^ a b Schroeder, Matt (31 August 2013). The MANPADS Threat and International Efforts to Address It: Ten Years after Mombasa (PDF). Federation of American Scientists. ISBN 9781938187025.

- ^ International Institute for Strategic Studies (1989). The Military Balance, 1989-1990. London: Brassey's. p. 34. ISBN 978-0080375694.

- ^ S. Boyne, "The White Legion: Mercenaries in Zaire", Jane's Intelligence Review, London. June 1997, p. 279.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Strela-2 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Strela-2 at Wikimedia Commons

9K32 Strela-2

View on GrokipediaDevelopment

Origins and Initial Design

The development of the 9K32 Strela-2 man-portable air-defense system began in 1960 within the Soviet Union, initiated as a response to the limitations of existing anti-aircraft artillery in engaging low-altitude, high-speed jet aircraft during tactical operations. Traditional towed or self-propelled guns struggled with rapid target acquisition and tracking against aircraft flying below 3,000 meters, prompting the military to seek a lightweight, infantry-portable solution analogous to emerging Western systems like the U.S. FIM-43 Redeye, whose design work had started in 1959. The program proceeded in parallel with the vehicle-launched 9K31 Strela-1, prioritizing passive infrared homing to enable uncued, fire-and-forget engagements without reliance on radar or complex electronics, thereby reducing size, weight, and vulnerability to electronic countermeasures.[7][8] Leadership of the effort fell to Boris I. Shavyrin, chief designer at the Tula-based Instrument Design Bureau (KBP), who assembled a cross-bureau team for initial conceptualization; this included intensive early-phase collaboration to define requirements such as a shoulder-fired launcher under 15 kg total weight, a range of up to 3.7 km, and a seeker optimized for rear-aspect targeting of engine exhaust plumes in the 3-5 micrometer infrared band. The missile's core components—drawn from solid-fuel rocket technology and proven warhead designs—emphasized ruggedness for field use, with the guidance section developed separately by the Scientific Research Institute of Physicotechnical Measurements (NIIFIZM) to ensure uncooled lead-sulfide detector sensitivity without cryogenic needs. This approach stemmed from causal priorities: minimizing mechanical complexity to achieve high production rates and operator simplicity, while accepting trade-offs like vulnerability to solar glare and basic decoys inherent to first-generation infrared seekers.[7][9] Prototyping and testing iterated on these foundations through the mid-1960s, addressing early seeker false locks and boost-sustain motor stability, before state trials confirmed viability against subsonic targets like helicopters and fixed-wing jets at altitudes up to 1.5 km. Acceptance into Soviet Armed Forces inventory occurred on March 8, 1968, marking the first operational MANPADS in the Eastern Bloc, though full-scale manufacturing ramped up by 1970 to meet export and domestic demands.[7][10]Production Milestones and Improvements