Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Upper limb

View on Wikipedia| Upper limb | |

|---|---|

Front of right upper extremity. | |

Back of right upper extremity. | |

| Details | |

| System | Musculoskeletal |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrum superius |

| MeSH | D034941 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.019 |

| TA2 | 138 |

| FMA | 7183 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The upper limbs or upper extremities are the forelimbs of an upright-postured tetrapod vertebrate, extending from the scapulae and clavicles down to and including the digits, including all the musculatures and ligaments involved with the shoulder, elbow, wrist and knuckle joints.[1] In humans, each upper limb is divided into the shoulder, arm, elbow, forearm, wrist and hand,[2][3] and is primarily used for climbing, lifting and manipulating objects. In anatomy, just as arm refers to the upper arm, leg refers to the lower leg.

Definition

[edit]In formal usage, the term "arm" only refers to the structures from the shoulder to the elbow, explicitly excluding the forearm, and thus "upper limb" and "arm" are not synonymous.[4] However, in casual usage, the terms are often used interchangeably. The term "upper arm" is redundant in anatomy, but in informal usage is used to distinguish between the two terms.

Structure

[edit]In the human body, the muscles of the upper limb can be classified by origin, topography, function, or innervation. While a grouping by innervation reveals embryological and phylogenetic origins, the functional-topographical classification below reflects the similarity in action between muscles (with the exception of the shoulder girdle, where muscles with similar action can vary considerably in their location and orientation.[5]

Musculoskeletal system

[edit]Shoulder girdle

[edit]

The shoulder girdle[6] or pectoral girdle,[7] composed of the clavicle and the scapula, connects the upper limb to the axial skeleton through the sternoclavicular joint (the only joint in the upper limb that directly articulates with the trunk), a ball and socket joint supported by the subclavius muscle which acts as a dynamic ligament. While this muscle prevents dislocation in the joint, strong forces tend to break the clavicle instead. The acromioclavicular joint, the joint between the acromion process on the scapula and the clavicle, is similarly strengthened by strong ligaments, especially the coracoclavicular ligament which prevents excessive lateral and medial movements. Between them these two joints allow a wide range of movements for the shoulder girdle, much because of the lack of a bone-to-bone contact between the scapula and the axial skeleton. The pelvic girdle is, in contrast, firmly fixed to the axial skeleton, which increases stability and load-bearing capabilities. [7]

The mobility of the shoulder girdle is supported by a large number of muscles. The most important of these are muscular sheets rather than fusiform or strap-shaped muscles and they thus never act in isolation but with some fibres acting in coordination with fibres in other muscles.[7]

- Muscles

- of shoulder girdle excluding the glenohumeral joint[5]

- Migrated from head

- Trapezius, sternocleidomastoideus, omohyoideus

- Posterior

- Rhomboideus major, rhomboideus minor, levator scapulae

- Anterior

- Subclavius, pectoralis minor, serratus anterior

Shoulder joint

[edit]

The glenohumeral joint (colloquially called the shoulder joint) is the highly mobile ball and socket joint between the glenoid cavity of the scapula and the head of the humerus. Lacking the passive stabilisation offered by ligaments in other joints, the glenohumeral joint is actively stabilised by the rotator cuff, a group of short muscles stretching from the scapula to the humerus. Little inferior support is available to the joint and dislocation of the shoulder almost exclusively occurs in this direction. [8]

The large muscles acting at this joint perform multiple actions and seemingly simple movements are often the result of composite antagonist and protagonist actions from several muscles. For example, pectoralis major is the most important arm flexor and latissimus dorsi the most important extensor at the glenohumeral joint, but, acting together, these two muscles cancel each other's action leaving only their combined medial rotation component. On the other hand, to achieve pure flexion at the joint the deltoid and supraspinatus must cancel the adduction component and the teres minor and infraspinatus the medial rotation component of pectoralis major. Similarly, abduction (moving the arm away from the body) is performed by different muscles at different stages. The first 10° is performed entirely by the supraspinatus, but beyond that fibres of the much stronger deltoid are in position to take over the work until 90°. To achieve the full 180° range of abduction the arm must be rotated medially and the scapula most be rotated about itself to direct the glenoid cavity upward. [8]

- Muscles

- of shoulder joint proper[5]

- Posterior

- Supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis, deltoideus, latissimus dorsi, teres major

- Anterior

- Pectoralis major, coracobrachialis

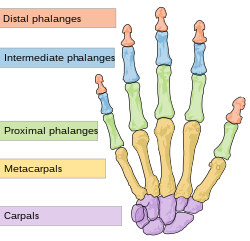

Bones of upper limb

[edit]The bones forming the human upper limb are

- Clavicle

- Scapula

- Humerus

- Radius

- Ulna

- Carpal bones

- Scaphoid

- Lunate

- Triquetral

- Pisiform

- Trapezium

- Trapezoid

- Capitate

- Hamate

- 5 Metacarpal bones

- 14 Phalanges

Arm

[edit]

The arm proper (brachium), sometimes called the upper arm,[6] the region between the shoulder and the elbow, is composed of the humerus with the elbow joint at its distal end.

The elbow joint is a complex of three joints — the humeroradial, humeroulnar, and superior radioulnar joints — the former two allowing flexion and extension whilst the latter, together with its inferior namesake, allows supination and pronation at the wrist. Triceps is the major extensor and brachialis and biceps the major flexors. Biceps is, however, the major supinator and while performing this action it ceases to be an effective flexor at the elbow. [9]

- Muscles

- of the arm[5]

- Posterior

- Triceps brachii, anconeus

- Anterior

- Brachialis, biceps brachii

Forearm

[edit]

The forearm (Latin: antebrachium),[6] composed of the radius and ulna; the latter is the main distal part of the elbow joint, while the former composes the main proximal part of the wrist joint.

Most of the large number of muscles in the forearm are divided into the wrist, hand, and finger extensors on the dorsal side (back of hand) and the ditto flexors in the superficial layers on the ventral side (side of palm). These muscles are attached to either the lateral or medial epicondyle of the humerus. They thus act on the elbow, but, because their origins are located close to the centre of rotation of the elbow, they mainly act distally at the wrist and hand. Exceptions to this simple division are brachioradialis — a strong elbow flexor — and palmaris longus — a weak wrist flexor which mainly acts to tense the palmar aponeurosis. The deeper flexor muscles are extrinsic hand muscles; strong flexors at the finger joints used to produce the important power grip of the hand, whilst forced extension is less useful and the corresponding extensor thus are much weaker. [10]

Biceps is the major supinator (drive a screw in with the right arm) and pronator teres and pronator quadratus the major pronators (unscrewing) — the latter two role the radius around the ulna (hence the name of the first bone) and the former reverses this action assisted by supinator. Because biceps is much stronger than its opponents, supination is a stronger action than pronation (hence the direction of screws). [10]

- Muscles

- of the forearm[5]

- Posterior

- (Superficial) extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi, extensor carpi ulnaris, (deep) supinator, abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis brevis, extensor pollicis longus, extensor indicis

- Anterior

- (Superficial) pronator teres, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, palmaris longus, (deep) flexor digitorum profundus, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus

- Radial

- Brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi radialis brevis

Wrist

[edit]The wrist (Latin: carpus),[6] composed of the carpal bones, articulates at the wrist joint (or radiocarpal joint) proximally and the carpometacarpal joint distally. The wrist can be divided into two components separated by the midcarpal joints. The small movements of the eight carpal bones during composite movements at the wrist are complex to describe, but flexion mainly occurs in the midcarpal joint whilst extension mainly occurs in the radiocarpal joint; the latter joint also providing most of adduction and abduction at the wrist. [11]

How muscles act on the wrist is complex to describe. The five muscles acting on the wrist directly — flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris, extensor carpi radialis, extensor carpi ulnaris, and palmaris longus — are accompanied by the tendons of the extrinsic hand muscles (i.e. the muscles acting on the fingers). Thus, every movement at the wrist is the work of a group of muscles; because the four primary wrist muscles (FCR, FCU, ECR, and ECU) are attached to the four corners of the wrist, they also produce a secondary movement (i.e. ulnar or radial deviation). To produce pure flexion or extension at the wrist, these muscle therefore must act in pairs to cancel out each other's secondary action. On the other hand, finger movements without the corresponding wrist movements require the wrist muscles to cancel out the contribution from the extrinsic hand muscles at the wrist. [11]

Hand

[edit]

The hand (Latin: manus),[6] the metacarpals (in the hand proper) and the phalanges of the fingers, form the metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP, including the knuckles) and interphalangeal joints (IP).

Of the joints between the carpus and metacarpus, the carpometacarpal joints, only the saddle-shaped joint of the thumb offers a high degree of mobility while the opposite is true for the metacarpophalangeal joints. The joints of the fingers are simple hinge joints. [11]

The primary role of the hand itself is grasping and manipulation; tasks for which the hand has been adapted to two main grips — power grip and precision grip. In a power grip an object is held against the palm and in a precision grip an object is held with the fingers, both grips are performed by intrinsic and extrinsic hand muscles together. Most importantly, the relatively strong thenar muscles of the thumb and the thumb's flexible first joint allow the special opposition movement that brings the distal thumb pad in direct contact with the distal pads of the other four digits. Opposition is a complex combination of thumb flexion and abduction that also requires the thumb to be rotated 90° about its own axis. Without this complex movement, humans would not be able to perform a precision grip. [12]

In addition, the central group of intrinsic hand muscles give important contributions to human dexterity. The palmar and dorsal interossei adduct and abduct at the MCP joints and are important in pinching. The lumbricals, attached to the tendons of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and extensor digitorum communis (FDC), flex the MCP joints while extending the IP joints and allow a smooth transfer of forces between these two muscles while extending and flexing the fingers. [12]

- Muscles

- of the hand[5]

Neurovascular system

[edit]Nerve supply

[edit]

The motor and sensory supply of the upper limb is provided by the brachial plexus which is formed by the ventral rami of spinal nerves C5-T1. In the posterior triangle of the neck these rami form three trunks from which fibers enter the axilla region (armpit) to innervate the muscles of the anterior and posterior compartments of the limb. In the axilla, cords are formed to split into branches, including the five terminal branches listed below. [13] The muscles of the upper limb are innervated segmentally proximal to distal so that the proximal muscles are innervated by higher segments (C5–C6) and the distal muscles are innervated by lower segments (C8–T1). [14]

Motor innervation of upper limb by the five terminal nerves of the brachial plexus:[14]

- The musculocutaneous nerve innervates all the muscles of the anterior compartment of the arm.

- The median nerve innervates all the muscles of the anterior compartment of the forearm except flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar part of the flexor digitorum profundus. It also innervates the three thenar muscles and the first and second lumbricals.

- The ulnar nerve innervates the muscles of the forearm and hand not innervated by the median nerve.

- The axillary nerve innervates the deltoid and teres minor.

- The radial nerve innervates the posterior muscles of the arm and forearm

Collateral branches of the brachial plexus:[14]

- The dorsal scapular nerve innervates rhomboid major, minor and levator scapulae .

- The long thoracic nerve innervates serratus anterior.

- The suprascapular nerve innervates supraspinatus and infraspinatus

- The lateral pectoral nerve innervates pectoralis major

- The medial pectoral nerve innervates pectoralis major and minor

- The upper subscapular nerve innervates subscapularis

- The thoracodorsal nerve innervates latissimus dorsi

- The lower subscapular nerve innervates subscapularis and teres major

- The medial brachial cutaneous nerve innervates the skin of medial arm

- The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve innervates the skin of medial forearm

Blood supply and drainage

[edit]Arteries of the upper limb:

- The superior thoracic, thoracoacromial, posterior circumflex humeral and subscapular branches of the axillary artery.

- The deep brachial, superior ulnar collateral, inferior ulnar collateral, radial,

ulnar, nutrient and muscular branches of the brachial artery.

- The radial recurrent, muscular, superficial palmar, dorsal carpal, princeps pollicis and radialis indicis branches of the radial artery.

- The anterior ulnar recurrent, posterior ulnar recurrent, anterior interosseous, posterior interosseous and superficial branches of the ulnar artery.

Veins of the upper limb:

As for the upper limb blood supply, there are many anatomical variations.[15]

Other animals

[edit]Evolutionary variation

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (July 2011) |

The skeletons of all mammals are based on a common pentadactyl ("five-fingered") template but optimised for different functions. While many mammals can perform other tasks using their forelimbs, their primary use in most terrestrial mammals is one of three main modes of locomotion: unguligrade (hoof walkers), digitigrade (toe walkers), and plantigrade (sole walkers). Generally, the forelimbs are optimised for speed and stamina, but in some mammals some of the locomotion optimisation have been sacrificed for other functions, such as digging and grasping. [16]

In primates, the upper limbs provide a wide range of movement which increases manual dexterity. The limbs of chimpanzees, compared to those of humans, reveal their different lifestyle. The chimpanzee primarily uses two modes of locomotion: knuckle-walking, a style of quadrupedalism in which the body weight is supported on the knuckles (or more properly on the middle phalanges of the fingers), and brachiation (swinging from branch to branch), a style of bipedalism in which flexed fingers are used to grasp branches above the head. To meet the requirements of these styles of locomotion, the chimpanzee's finger phalanges are longer and have more robust insertion areas for the flexor tendons while the metacarpals have transverse ridges to limit dorsiflexion (stretching the fingers towards the back of the hand). The thumb is small enough to facilitate brachiation while maintaining some of the dexterity offered by an opposable thumb. In contrast, virtually all locomotion functionality has been lost in humans while predominant brachiators, such as the gibbons, have very reduced thumbs and inflexible wrists. [16]

In ungulates the forelimbs are optimised to maximize speed and stamina to the extent that the limbs serve almost no other purpose. In contrast to the skeleton of human limbs, the proximal bones of ungulates are short and the distal bones long to provide length of stride; proximally, large and short muscles provide rapidity of step. The odd-toed ungulates, such as the horse, use a single third toe for weight-bearing and have significantly reduced metacarpals. Even-toed ungulates, such as the giraffe, uses both their third and fourth toes but a single completely fused phalanx bone for weight-bearing. Ungulates whose habitat does not require fast running on hard terrain, for example the hippopotamus, have maintained four digits. [16]

In species in the order Carnivora, some of which are insectivores rather than carnivores, the cats are some of the most highly evolved predators designed for speed, power, and acceleration rather than stamina. Compared to ungulates, their limbs are shorter, more muscular in the distal segments, and maintain five metacarpals and digit bones; providing a greater range of movements, a more varied function and agility (e.g. climbing, swatting, and grooming). Some insectivorous species in this order have paws specialised for specific functions. The sloth bear uses their digits and large claws to tear logs open rather than kill prey. Other insectivorous species, such as the giant and red pandas, have developed large sesamoid bones in their paws that serve as an extra "thumb" while others, such as the meerkat, uses their limbs primary for digging and have vestigial first digits. [16]

The arboreal two-toed sloth, a South American mammal in the order Pilosa, have limbs so highly adapted to hanging in branches that it is unable to walk on the ground where it has to drag its own body using the large curved claws on its foredigits. [16]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Upper Extremity". MeSH. Archived from the original on January 10, 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ "Upper limb anatomy".

- ^ Wineski, Lawrence E. (2019). Snell's clinical anatomy by regions (10th ed.). Wolters Kluwers. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-4963-4564-6.

- ^ "Arm". MeSH. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Ross & Lamperti 2006, p. 256

- ^ a b c d e Ross & Lamperti 2006, p. 208

- ^ a b c Sellers 2002, pp. 1–3

- ^ a b Sellers 2002, pp. 3–5

- ^ Sellers 2002, p. 5

- ^ a b Sellers 2002, pp. 6–7

- ^ a b c Sellers 2002, pp. 8–9

- ^ a b Sellers 2002, pp. 10–11

- ^ Seiden 2002, p. 243

- ^ a b c Seiden 2002, pp. 233–36

- ^ Konarik M, Musil V, Baca V, Kachlik D (November 2020). "Upper limb principal arteries variations: A cadaveric study with terminological implication". Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 20 (4): 502–513. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2020.4643. PMC 7664784. PMID 32343941.

- ^ a b c d e Gough-Palmer, Maclachlan & Routh 2008, pp. 502–510

References

[edit]- Gough-Palmer, Antony L; Maclachlan, Jody; Routh, Andrew (March 2008). "Paws for Thought: Comparative Radiologic Anatomy of the Mammalian Forelimb" (PDF). RadioGraphics. 28 (2): 501–510. doi:10.1148/rg.282075061. PMID 18349453.

- Ross, Lawrence M; Lamperti, Edward D, eds. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

- Sellers, Bill (2002). "Functional Anatomy of the Upper Limb". Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- Seiden, David (2002). USMLE Step 1 Anatomy Notes. Kaplan Medical.

Upper limb

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

The upper limb, also known as the upper extremity, is the region of the human body that extends from the pectoral girdle to the distal phalanges of the hand, forming a key component of the appendicular skeleton.[4] The pectoral girdle, consisting of the clavicle and scapula, anchors the upper limb to the axial skeleton at the shoulder, while the free portion includes the arm (humerus), forearm (radius and ulna), wrist (carpal bones), and hand (metacarpals and phalanges).[5] This structure encompasses 32 bones per side—4 in the girdle and 28 in the free limb—enabling a wide range of motion from the shoulder to the fingertips.[4] In contrast to the lower limb, which is primarily adapted for weight-bearing and locomotion through stable pelvic attachments and robust skeletal elements, the upper limb is specialized for mobility, prehension, and fine manipulation, reflecting evolutionary priorities for tool use and environmental interaction in primates and humans.[1] Its basic composition integrates bones with synovial joints for articulation, skeletal muscles for movement, peripheral nerves from the brachial plexus for sensory and motor innervation, and a vascular network derived from the subclavian artery and accompanying veins to support dexterity and endurance.[6] The nomenclature of the upper limb draws from classical Latin and Greek roots, with "brachium" denoting the arm (from the shoulder to elbow) and "manus" referring to the hand, terms established in early anatomical texts like those of Galen and later standardized in Renaissance works by Vesalius.[7] These etymologies underscore the limb's historical recognition as a versatile appendage, distinct in form and function from the lower extremity.[5]Functions

The upper limb plays a pivotal role in human physiology by facilitating manipulation and prehension, which involve grasping, reaching, and executing fine motor tasks through the hand's exceptional dexterity. This capability is enabled by the thumb's opposability and the coordinated action of the fingers, allowing precise object handling essential for daily activities such as writing or tool manipulation.[1] The structure supports a range of grip types, from power grips for heavy objects to precision grips for delicate tasks, enhancing environmental interaction and productivity.[1] Sensory functions of the upper limb provide critical tactile feedback through skin receptors and proprioception, enabling spatial awareness and accurate movement control. Tactile sensations detect pressure, texture, and temperature via mechanoreceptors in the skin, while proprioceptors in muscles and joints convey information about limb position and motion to the central nervous system.[8] This sensory integration allows for seamless adjustment during tasks, preventing errors and supporting adaptive responses.[8] In supportive roles, the upper limb contributes to weight-bearing in postures like quadrupedal support or push-up positions, distributing body load through the shoulder girdle and elbow for stability.[9] Additionally, it facilitates communication through gestures, such as pointing or waving, which convey non-verbal information and enhance social interaction.[10] The upper limb's integration with the central nervous system underscores its significance in tool use and the cultural evolution of human dexterity. This connection has driven evolutionary adaptations, allowing early hominins to manipulate objects and innovate technologies, shaping cognitive and societal development.[11]Anatomy

Skeletal components

The skeletal components of the upper limb provide the rigid framework essential for support, mobility, and manipulation, consisting of the pectoral girdle, humerus, radius, ulna, and the bones of the hand. These elements articulate to form a flexible appendage capable of a wide range of movements, with specific features like articular surfaces and fossae facilitating joint stability and motion.[12] The pectoral girdle anchors the upper limb to the axial skeleton and includes the clavicle and scapula. The clavicle, an S-shaped long bone, articulates medially with the manubrium of the sternum at the sternoclavicular joint and laterally with the acromion process of the scapula at the acromioclavicular joint; its sternal end is triangular and enlarged, while the acromial end is flattened and oval.[13] The scapula, a flat triangular bone, features the acromion process projecting anteriorly to articulate with the clavicle, the coracoid process serving as an attachment site, and the glenoid cavity—a shallow, pear-shaped articular surface deepened by the glenoid labrum for humeral articulation at the glenohumeral joint.[13] The humerus forms the skeleton of the arm, extending from the shoulder to the elbow. Proximally, it includes a rounded head that articulates with the glenoid cavity and two tubercles—the larger greater tubercle laterally and the smaller lesser tubercle anteriorly—for rotator cuff attachments. The shaft is cylindrical with a deltoid tuberosity midway. Distally, the humerus features the capitulum (a lateral rounded condyle articulating with the radius), the trochlea (a medial pulley-shaped condyle articulating with the ulna), the medial and lateral epicondyles for ligament attachments, and fossae such as the anterior coronoid and radial fossae (accommodating ulnar and radial processes during flexion) and the posterior olecranon fossa (for the ulna during extension).[13] The forearm comprises the radius and ulna, parallel long bones connected by the interosseous membrane, a fibrous sheet that binds their shafts and transmits forces between them. The radius, lateral and shorter, has a disc-shaped head proximally that articulates with the capitulum of the humerus and the radial notch of the ulna; distally, it features a styloid process projecting laterally for ligament attachment. The ulna, medial and longer, includes a proximal olecranon process and trochlear notch articulating with the humeral trochlea, a radial notch for the radius, and a distal styloid process medially.[13] The hand skeleton includes the carpals, metacarpals, and phalanges, enabling precise dexterity. The eight carpal bones, arranged in two rows, are the proximal scaphoid (with a tubercle and waist prone to fracture), lunate, triquetrum, and pisiform (sesamoid-like), and the distal trapezium (saddle-shaped for thumb articulation), trapezoid, capitate, and hamate (with a hook); they form the wrist's concavity for flexor tendon passage. The five metacarpals are elongated bones with bases articulating proximally with the carpals at carpometacarpal joints and heads distally with phalanges at metacarpophalangeal joints; the first (thumb) is the shortest and most mobile. The 14 phalanges consist of proximal, middle (absent in thumb), and distal bones per digit, with bases articulating proximally and heads distally forming interphalangeal joints; the thumb has two (proximal and distal), while fingers have three each.[13] Ossification of upper limb bones begins in utero via primary centers in diaphyses and secondary centers in epiphyses, with fusion occurring postnatally; timelines vary by bone and sex (earlier in females). The clavicle ossifies first intramembranously at 6 weeks gestation in the diaphysis, with a secondary sternal epiphysis appearing at 18-20 years and full union by 20-25 years.[14] Scapular ossification starts at 8 weeks gestation for the body, spine, and glenoid (primary center), with coracoid at 1 year and epiphyses for acromion (15-18 years), inferior angle (16-18 years), vertebral border (18-20 years), and coracoid/glenoid (16-18 years), uniting by 18-25 years.[14] The humerus has a primary diaphyseal center at 6-7 weeks, with epiphyses for head (1-2 years), greater tubercle (2-3 years), lesser tubercle (3-5 years), capitulum (2-3 years), medial epicondyle (5-8 years), and lateral epicondyle/trochlea (11-14 years), fusing by 16-25 years.[14] Radius and ulna diaphyses appear at 7 weeks; radius epiphyses at carpal end (females 8 months, males 15 months) and humeral end (6-7 years), ulna at carpal end (females 6-7 years, males 7-8 years) and humeral end (10 years), with unions by 17-25 years and 17-24 years, respectively.[14] Carpal ossification is delayed: capitate (females 3-6 months, males 4-10 months), hamate (females 5-10 months, males 6-12 months), triquetrum (females 2-3 years, males ~3 years), lunate (females 3-4 years, males ~4 years), scaphoid (females 4-5 years, males ~5 years), trapezium/trapezoid (females 4-5 years, males 5-6 years), pisiform (females 9-10 years, males 12-13 years). Metacarpal diaphyses form at 9 weeks, with proximal first metacarpal epiphysis at 3 years and distal others at 2 years, uniting by 15-20 years. Phalangeal diaphyses ossify at 7-12 weeks (distal row first, then proximal and middle), with proximal epiphyses at 1-3 years and unions by 18-20 years.[14]| Bone | Primary Center (Diaphysis) | Key Secondary Centers (Epiphyses) | Union Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clavicle | 6 weeks gestation | Sternal end: 18-20 years | 20-25 years |

| Scapula | 8 weeks gestation (body/glenoid) | Acromion: 15-18 years; Coracoid: 1 year (initial), 16-18 years (final); Inferior angle: 16-18 years | 18-25 years |

| Humerus | 6-7 weeks gestation | Head: 1-2 years; Greater tubercle: 2-3 years; Capitulum: 2-3 years; Medial epicondyle: 5-8 years; Trochlea: 11-14 years | 16-25 years |

| Radius | 7 weeks gestation | Distal (carpal): Females 8 months, males 15 months; Proximal (humeral): 6-7 years | 17-25 years |

| Ulna | 7 weeks gestation | Distal (carpal): Females 6-7 years, males 7-8 years; Proximal (humeral): 10 years | 17-24 years |

| Carpals | Variable, postnatal | Capitate: Females 3-6 months, males 4-10 months; Pisiform: Females 9-10 years, males 12-13 years | N/A (no epiphyses) |

| Metacarpals | 9 weeks gestation | Distal: 2 years; Proximal (1st): 3 years | 15-20 years |

| Phalanges | 7-12 weeks gestation | Proximal: 1-3 years | 18-20 years |

Joints and ligaments

The upper limb features a series of synovial joints that provide extensive mobility, from the proximal shoulder to the distal finger articulations, stabilized by ligaments that prevent excessive translation while permitting multi-planar motion. These joints are classified based on their morphology and function, with degrees of freedom ranging from uniaxial to triaxial, enabling precise manipulation and reach.[15] The glenohumeral joint, also known as the shoulder joint, is a multiaxial ball-and-socket synovial joint formed by the articulation of the humeral head with the glenoid cavity of the scapula. It allows flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, and internal-external rotation across three rotational axes, providing the widest range of motion in the body. The joint is enclosed by a loose fibrous capsule reinforced by glenohumeral ligaments, and the glenoid labrum—a fibrocartilaginous rim—deepens the shallow glenoid socket to enhance stability.[16][17][18] The elbow complex comprises the humeroulnar and humeroradial articulations forming a uniaxial hinge joint for flexion-extension, combined with the proximal radioulnar pivot joint enabling pronation-supination. This setup allows two degrees of freedom: one for hinging and one for rotation. Stability is augmented by the annular ligament, which encircles the radial head and binds it to the ulna, preventing subluxation during forearm rotation.[19][20][21] The radiocarpal joint, or wrist joint, is a biaxial ellipsoid synovial joint between the distal radius and the proximal carpal row (scaphoid, lunate, and triquetrum), permitting flexion-extension and radial-ulnar deviation. Its stability relies on collateral ligaments, including the radial collateral (from radius to scaphoid and trapezium) and ulnar collateral (from ulna to triquetrum), which resist lateral deviations.[22][23][24] In the hand, the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb is a unique saddle synovial joint between the trapezium and first metacarpal, allowing opposition and circumduction with three degrees of freedom for enhanced dexterity. The metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints are condyloid synovial joints between metacarpals and proximal phalanges, supporting flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, and circumduction in two planes. Interphalangeal (IP) joints, including proximal and distal, are uniaxial hinge synovial joints between phalanges, restricted to flexion-extension for precise gripping.[25][26][27][28] Key ligaments throughout the upper limb include the coracoclavicular ligament, which connects the coracoid process to the clavicle, suspending the scapula and preventing acromioclavicular dislocation under the weight of the arm. The transverse humeral ligament spans the intertubercular groove of the humerus, retaining the long head of the biceps tendon within the groove during shoulder motion. At the wrist, palmar and dorsal radiocarpal ligaments extend from the radius to the carpals, limiting excessive flexion and extension while guiding carpal alignment.[23][29][24] All upper limb joints are synovial, featuring a cavity filled with synovial fluid secreted by the synovial membrane, which lubricates articular surfaces to minimize friction and provides nutrients to avascular cartilage. This fluid's viscous properties absorb shock and facilitate smooth gliding, essential for the limb's repetitive, high-mobility demands.[26][24][30]Muscles

The muscles of the upper limb enable a wide range of movements, from gross shoulder motions to fine hand manipulations, and are organized into functional groups based on their anatomical regions and actions. These muscles vary in architecture, with fusiform types like the biceps brachii featuring parallel fibers for greater excursion and speed, while pennate types, such as the unipennate flexor pollicis longus or multipennate subscapularis, have oblique fibers attaching to tendons for enhanced force production through larger physiological cross-sectional areas.[31][32] Shoulder muscles primarily stabilize and move the glenohumeral joint, with the rotator cuff providing dynamic stability and others effecting abduction, adduction, and rotation. The supraspinatus originates from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula and inserts on the greater tubercle of the humerus; it is innervated by the suprascapular nerve (C5-C6) and primarily abducts the arm. The infraspinatus arises from the infraspinous fossa and inserts on the greater tubercle; innervated by the suprascapular nerve (C5-C6), it laterally rotates the arm. The teres minor originates from the upper two-thirds of the lateral border of the scapula and inserts on the greater tubercle; supplied by the axillary nerve (C5-C6), it laterally rotates the arm and assists in adduction. The subscapularis originates from the subscapular fossa and inserts on the lesser tubercle; innervated by the upper and lower subscapular nerves (C5-C7), it medially rotates the arm. The deltoid originates from the clavicle, acromion, and spine of the scapula, inserting on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus; innervated by the axillary nerve (C5-C6), it abducts the arm and assists in flexion, extension, and rotation depending on the fiber portion. The pectoralis major originates from the clavicle, sternum, and costal cartilages of ribs 2-6, inserting on the intertubercular groove of the humerus; supplied by the lateral and medial pectoral nerves (C5-T1), it flexes, adducts, and medially rotates the arm.[31][33]| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Primary Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supraspinatus | Supraspinous fossa | Greater tubercle of humerus | Suprascapular nerve | Abducts arm |

| Infraspinatus | Infraspinous fossa | Greater tubercle of humerus | Suprascapular nerve | Laterally rotates arm |

| Teres minor | Lateral border of scapula | Greater tubercle of humerus | Axillary nerve | Laterally rotates arm |

| Subscapularis | Subscapular fossa | Lesser tubercle of humerus | Subscapular nerves | Medially rotates arm |

| Deltoid | Clavicle, acromion, scapular spine | Deltoid tuberosity | Axillary nerve | Abducts arm |

| Pectoralis major | Clavicle, sternum, ribs 2-6 | Intertubercular groove of humerus | Pectoral nerves | Flexes, adducts, medially rotates arm |

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Primary Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biceps brachii (long/short heads) | Supraglenoid tubercle/coracoid process | Radial tuberosity | Musculocutaneous nerve | Flexes forearm, supinates hand |

| Triceps brachii | Infraglenoid tubercle, posterior humerus | Olecranon process | Radial nerve | Extends forearm |

| Brachialis | Anterior distal humerus | Coronoid process of ulna | Musculocutaneous nerve | Flexes forearm |

| Muscle Example | Compartment | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Primary Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexor carpi radialis | Anterior | Medial epicondyle | Bases of metacarpals 2-3 | Median nerve | Flexes, abducts wrist |

| Extensor digitorum | Posterior | Lateral epicondyle | Extensor expansions digits 2-5 | Posterior interosseous nerve | Extends wrist, digits |

| Pronator teres | Anterior | Medial epicondyle, coronoid process | Mid-radius | Median nerve | Pronates forearm |

| Supinator | Posterior | Lateral epicondyle, ulna | Proximal radius | Deep radial nerve | Supinates forearm |

| Muscle Group/Example | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Primary Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thenar (abductor pollicis brevis) | Flexor retinaculum, scaphoid | Proximal phalanx of thumb | Median nerve | Abducts thumb |

| Hypothenar (abductor digiti minimi) | Pisiform, flexor retinaculum | Proximal phalanx of digit 5 | Ulnar nerve | Abducts little finger |

| Palmar interossei | Medial metacarpals 2,4,5 | Extensor expansions | Ulnar nerve | Adduct fingers |

| Dorsal interossei | Adjacent metacarpals | Extensor expansions | Ulnar nerve | Abduct fingers |

| Lumbricals | Flexor digitorum profundus tendons | Extensor expansions digits 2-5 | Median/ulnar nerves | Flex MCP, extend IP joints |