Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Visible spectrum

View on Wikipedia

The visible spectrum is the band of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. Electromagnetic radiation in this range of wavelengths is called visible light (or simply light). The optical spectrum is sometimes considered to be the same as the visible spectrum, but some authors define the term more broadly, to include the ultraviolet and infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum as well, known collectively as optical radiation.[1][2]

A typical human eye will respond to wavelengths from about 380 to about 750 nanometers.[3] In terms of frequency, this corresponds to a band in the vicinity of 400–790 terahertz. These boundaries are not sharply defined and may vary per individual.[4] Under optimal conditions, these limits of human perception can extend to 310 nm (ultraviolet) and 1100 nm (near infrared).[5][6][7]

The spectrum does not contain all the colors that the human visual system can distinguish. Unsaturated colors such as pink, or purple variations like magenta, for example, are absent because they can only be made from a mix of multiple wavelengths. Colors containing only one wavelength are also called pure colors or spectral colors.[8][9]

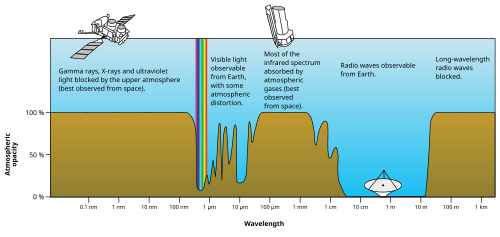

Visible wavelengths pass largely unattenuated through the Earth's atmosphere via the "optical window" region of the electromagnetic spectrum. An example of this phenomenon is when clean air scatters blue light more than red light, and so the midday sky appears blue (apart from the area around the Sun which appears white because the light is not scattered as much). The optical window is also referred to as the "visible window" because it overlaps the human visible response spectrum. The near infrared (NIR) window lies just out of the human vision, as well as the medium wavelength infrared (MWIR) window, and the long-wavelength or far-infrared (LWIR or FIR) window, although other animals may perceive them.[2][4]

Spectral colors

[edit] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Wavelength (nm) |

Frequency (THz) |

Photon energy (eV) |

| 380–450 | 670–790 | 2.75–3.26 | |

| 450–485 | 620–670 | 2.56–2.75 | |

| 485–500 | 600–620 | 2.48–2.56 | |

| 500–565 | 530–600 | 2.19–2.48 | |

| 565–590 | 510–530 | 2.10–2.19 | |

| 590–625 | 480–510 | 1.98–2.10 | |

| 625–750 | 400–480 | 1.65–1.98 | |

Colors that can be produced by visible light of a narrow band of wavelengths (monochromatic light) are called spectral colors. The various color ranges indicated in the illustration are an approximation: The spectrum is continuous, with no clear boundaries between one color and the next.[10]

History

[edit]

In the 13th century, Roger Bacon theorized that rainbows were produced by a similar process to the passage of light through glass or crystal.[11]

In the 17th century, Isaac Newton discovered that prisms could disassemble and reassemble white light, and described the phenomenon in his book Opticks. He was the first to use the word spectrum (Latin for "appearance" or "apparition") in this sense in print in 1671 in describing his experiments in optics. Newton observed that, when a narrow beam of sunlight strikes the face of a glass prism at an angle, some is reflected and some of the beam passes into and through the glass, emerging as different-colored bands. Newton hypothesized light to be made up of "corpuscles" (particles) of different colors, with the different colors of light moving at different speeds in transparent matter, red light moving more quickly than violet in glass. The result is that red light is bent (refracted) less sharply than violet as it passes through the prism, creating a spectrum of colors.

Newton originally divided the spectrum into six named colors: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. He later added indigo as the seventh color since he believed that seven was a perfect number as derived from the ancient Greek sophists, of there being a connection between the colors, the musical notes, the known objects in the Solar System, and the days of the week.[12] The human eye is relatively insensitive to indigo's frequencies, and some people who have otherwise-good vision cannot distinguish indigo from blue and violet. For this reason, some later commentators, including Isaac Asimov,[13] have suggested that indigo should not be regarded as a color in its own right but merely as a shade of blue or violet. Evidence indicates that what Newton meant by "indigo" and "blue" does not correspond to the modern meanings of those color words. Comparing Newton's observation of prismatic colors with a color image of the visible light spectrum shows that "indigo" corresponds to what is today called blue, whereas his "blue" corresponds to cyan.[14][15][16]

In the 18th century, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote about optical spectra in his Theory of Colours. Goethe used the word spectrum (Spektrum) to designate a ghostly optical afterimage, as did Schopenhauer in On Vision and Colors. Goethe argued that the continuous spectrum was a compound phenomenon. Where Newton narrowed the beam of light to isolate the phenomenon, Goethe observed that a wider aperture produces not a spectrum but rather reddish-yellow and blue-cyan edges with white between them. The spectrum appears only when these edges are close enough to overlap.

In the early 19th century, the concept of the visible spectrum became more definite, as light outside the visible range was discovered and characterized by William Herschel (infrared) and Johann Wilhelm Ritter (ultraviolet), Thomas Young, Thomas Johann Seebeck, and others.[17] Young was the first to measure the wavelengths of different colors of light, in 1802.[18]

The connection between the visible spectrum and color vision was explored by Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz in the early 19th century. Their theory of color vision correctly proposed that the eye uses three distinct receptors to perceive color.

Limits to visible range

[edit]

The visible spectrum is limited to wavelengths that can both reach the retina and trigger visual phototransduction (excite a visual opsin). Insensitivity to UV light is generally limited by transmission through the lens. Insensitivity to IR light is limited by the spectral sensitivity functions of the visual opsins. The range is defined psychometrically by the luminous efficiency function, which accounts for all of these factors. In humans, there is a separate function for each of two visual systems, one for photopic vision, used in daylight, which is mediated by cone cells, and one for scotopic vision, used in dim light, which is mediated by rod cells. Each of these functions have different visible ranges. However, discussion on the visible range generally assumes photopic vision.

Atmospheric transmission

[edit]The visible range of most animals evolved to match the optical window, which is the range of light that can pass through the atmosphere. The ozone layer absorbs almost all UV light (below 315 nm).[19] However, this only affects cosmic light (e.g. sunlight), not terrestrial light (e.g. Bioluminescence).

Ocular transmission

[edit]

Before reaching the retina, light must first transmit through the cornea and lens. UVB light (< 315 nm) is filtered mostly by the cornea, and UVA light (315–400 nm) is filtered mostly by the lens.[20] The lens also yellows with age, attenuating transmission most strongly at the blue part of the spectrum.[20] This can cause xanthopsia as well as a slight truncation of the short-wave (blue) limit of the visible spectrum. Subjects with aphakia are missing a lens, so UVA light can reach the retina and excite the visual opsins; this expands the visible range and may also lead to cyanopsia.

Opsin absorption

[edit]Each opsin has a spectral sensitivity function, which defines how likely it is to absorb a photon of each wavelength. The luminous efficiency function is approximately the superposition of the contributing visual opsins. Variance in the position of the individual opsin spectral sensitivity functions therefore affects the luminous efficiency function and the visible range. For example, the long-wave (red) limit changes proportionally to the position of the L-opsin. The positions are defined by the peak wavelength (wavelength of highest sensitivity), so as the L-opsin peak wavelength blue shifts by 10 nm, the long-wave limit of the visible spectrum also shifts 10 nm. Large deviations of the L-opsin peak wavelength lead to a form of color blindness called protanomaly and a missing L-opsin (protanopia) shortens the visible spectrum by about 30 nm at the long-wave limit. Forms of color blindness affecting the M-opsin and S-opsin do not significantly affect the luminous efficiency function nor the limits of the visible spectrum.

Different definitions

[edit]Regardless of actual physical and biological variance, the definition of the limits is not standard and will change depending on the industry. For example, some industries may be concerned with practical limits, so would conservatively report 420–680 nm,[21][22] while others may be concerned with psychometrics and achieving the broadest spectrum would liberally report 380–750, or even 380–800 nm.[23][24] The luminous efficiency function in the NIR does not have a hard cutoff, but rather an exponential decay, such that the function's value (or vision sensitivity) at 1,050 nm is about 109 times weaker than at 700 nm; much higher intensity is therefore required to perceive 1,050 nm light than 700 nm light.[25]

Vision outside the visible spectrum

[edit]Under ideal laboratory conditions, subjects may perceive infrared light up to at least 1,064 nm.[25] While 1,050 nm NIR light can evoke red, suggesting direct absorption by the L-opsin, there are also reports that pulsed NIR lasers can evoke green, which suggests two-photon absorption may be enabling extended NIR sensitivity.[25]

Similarly, young subjects may perceive ultraviolet wavelengths down to about 310–313 nm,[26][27][28] but detection of light below 380 nm may be due to fluorescence of the ocular media, rather than direct absorption of UV light by the opsins. As UVA light is absorbed by the ocular media (lens and cornea), it may fluoresce and be released at a lower energy (longer wavelength) that can then be absorbed by the opsins. For example, when the lens absorbs 350 nm light, the fluorescence emission spectrum is centered on 440 nm.[29]

Non-visual light detection

[edit]In addition to the photopic and scotopic systems, humans have other systems for detecting light that do not contribute to the primary visual system. For example, melanopsin has an absorption range of 420–540 nm and regulates circadian rhythm and other reflexive processes.[30] Since the melanopsin system does not form images, it is not strictly considered vision and does not contribute to the visible range.

In non-humans

[edit]The visible spectrum is defined as that visible to humans, but the variance between species is large. Not only can cone opsins be spectrally shifted to alter the visible range, but vertebrates with 4 cones (tetrachromatic) or 2 cones (dichromatic) relative to humans' 3 (trichromatic) will also tend to have a wider or narrower visible spectrum than humans, respectively.

Vertebrates tend to have 1-4 different opsin classes:[19]

- longwave sensitive (LWS) with peak sensitivity between 500–570 nm,

- middlewave sensitive (MWS) with peak sensitivity between 480–520 nm,

- shortwave sensitive (SWS) with peak sensitivity between 415–470 nm, and

- violet/ultraviolet sensitive (VS/UVS) with peak sensitivity between 355–435 nm.

Testing the visual systems of animals behaviorally is difficult, so the visible range of animals is usually estimated by comparing the peak wavelengths of opsins with those of typical humans (S-opsin at 420 nm and L-opsin at 560 nm).

Mammals

[edit]Most mammals have retained only two opsin classes (LWS and VS), due likely to the nocturnal bottleneck. However, old world primates (including humans) have since evolved two versions in the LWS class to regain trichromacy.[19] Unlike most mammals, rodents' UVS opsins have remained at shorter wavelengths. Along with their lack of UV filters in the lens, mice have a UVS opsin that can detect down to 340 nm. While allowing UV light to reach the retina can lead to retinal damage, the short lifespan of mice compared with other mammals may minimize this disadvantage relative to the advantage of UV vision.[31] Dogs have two cone opsins at 429 nm and 555 nm, so see almost the entire visible spectrum of humans, despite being dichromatic.[32] Horses have two cone opsins at 428 nm and 539 nm, yielding a slightly more truncated red vision.[33]

Birds

[edit]Most other vertebrates (birds, lizards, fish, etc.) have retained their tetrachromacy, including UVS opsins that extend further into the ultraviolet than humans' VS opsin.[19] The sensitivity of avian UVS opsins vary greatly, from 355–425 nm, and LWS opsins from 560–570 nm.[34] This translates to some birds with a visible spectrum on par with humans, and other birds with greatly expanded sensitivity to UV light. The LWS opsin of birds is sometimes reported to have a peak wavelength above 600 nm, but this is an effective peak wavelength that incorporates the filter of avian oil droplets.[34] The peak wavelength of the LWS opsin alone is the better predictor of the long-wave limit. A possible benefit of avian UV vision involves sex-dependent markings on their plumage that are visible only in the ultraviolet range.[35][36]

Fish

[edit]Teleosts (bony fish) are generally tetrachromatic. The sensitivity of fish UVS opsins vary from 347-383 nm, and LWS opsins from 500-570 nm.[37] However, some fish that use alternative chromophores can extend their LWS opsin sensitivity to 625 nm.[37] The popular belief that the common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infrared and ultraviolet light[38] is incorrect, because goldfish cannot see infrared light.[39]

Invertebrates

[edit]The visual systems of invertebrates deviate greatly from vertebrates, so direct comparisons are difficult. However, UV sensitivity has been reported in most insect species.[40] Bees and many other insects can detect ultraviolet light, which helps them find nectar in flowers. Plant species that depend on insect pollination may owe reproductive success to their appearance in ultraviolet light rather than how colorful they appear to humans. Bees' long-wave limit is at about 590 nm.[41] Mantis shrimp exhibit up to 14 opsins, enabling a visible range of less than 300 nm to above 700 nm.[19]

Thermal vision

[edit]Some snakes can "see"[42] radiant heat at wavelengths between 5 and 30 μm to a degree of accuracy such that a blind rattlesnake can target vulnerable body parts of the prey at which it strikes,[43] and other snakes with the organ may detect warm bodies from a meter away.[44] It may also be used in thermoregulation and predator detection.[45][46]

Spectroscopy

[edit]

Spectroscopy is the study of objects based on the spectrum of color they emit, absorb or reflect. Visible-light spectroscopy is an important tool in astronomy (as is spectroscopy at other wavelengths), where scientists use it to analyze the properties of distant objects. Chemical elements and small molecules can be detected in astronomical objects by observing emission lines and absorption lines. For example, helium was first detected by analysis of the spectrum of the Sun. The shift in frequency of spectral lines is used to measure the Doppler shift (redshift or blueshift) of distant objects to determine their velocities towards or away from the observer. Astronomical spectroscopy uses high-dispersion diffraction gratings to observe spectra at very high spectral resolutions.

See also

[edit]- Cosmic ray visual phenomena

- Electromagnetic absorption by water

- High-energy visible light

- Two-photon absorption - a method for seeing outside the visible spectrum

References

[edit]- ^ Pedrotti, Frank L.; Pedrotti, Leno M.; Pedrotti, Leno S. (December 21, 2017). Introduction to Optics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-108-42826-2.

- ^ a b "What Is the Visible Light Spectrum?". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on 2024-09-18. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ Starr, Cecie (2005). Biology: Concepts and Applications. Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-534-46226-0.

- ^ a b "The visible spectrum". Britannica. 27 May 2024. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ D. H. Sliney (February 2016). "What is light? The visible spectrum and beyond". Eye. 30 (2): 222–229. doi:10.1038/eye.2015.252. ISSN 1476-5454. PMC 4763133. PMID 26768917.

- ^ W. C. Livingston (2001). Color and light in nature (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77284-2. Archived from the original on 2024-10-04. Retrieved 2021-03-05.

- ^ Grazyna Palczewska; et al. (December 2014). "Human infrared vision is triggered by two-photon chromophore isomerization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (50): E5445 – E5454. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E5445P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1410162111. PMC 4273384. PMID 25453064.

- ^ Nave, R. "Spectral Colors". Hyperphysics. Archived from the original on 2017-10-27. Retrieved 2022-05-11.

- ^ "Colour - Visible Spectrum, Wavelengths, Hues | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2024-09-10. Archived from the original on 2022-07-12. Retrieved 2024-10-04.

- ^ Bruno, Thomas J. and Svoronos, Paris D. N. (2005). CRC Handbook of Fundamental Spectroscopic Correlation Charts. Archived 2024-10-04 at the Wayback Machine CRC Press. ISBN 9781420037685

- ^ Coffey, Peter (1912). The Science of Logic: An Inquiry Into the Principles of Accurate Thought. Longmans. p. 185.

roger bacon prism.

- ^ Isacoff, Stuart (16 January 2009). Temperament: How Music Became a Battleground for the Great Minds of Western Civilization. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-307-56051-3. Archived from the original on 4 October 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1975). Eyes on the universe: a history of the telescope. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-395-20716-1.

- ^ Evans, Ralph M. (1974). The perception of color (null ed.). New York: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-471-24785-2.

- ^ McLaren, K. (March 2007). "Newton's indigo". Color Research & Application. 10 (4): 225–229. doi:10.1002/col.5080100411.

- ^ Waldman, Gary (2002). Introduction to light: the physics of light, vision, and color (Dover ed.). Mineola: Dover Publications. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-486-42118-6. Archived from the original on 2024-10-04. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ Mary Jo Nye, ed. (2003). The Cambridge History of Science: The Modern Physical and Mathematical Sciences. Vol. 5. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-521-57199-9. Archived from the original on 2024-10-04. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ John C. D. Brand (1995). Lines of light: the sources of dispersive spectroscopy, 1800–1930. CRC Press. pp. 30–32. ISBN 978-2-88449-163-1. Archived from the original on 2024-10-04. Retrieved 2020-10-29.

- ^ a b c d e Hunt, D.M.; Wilkie, S.E.; Bowmaker, J.K.; Poopalasundaram, S. (October 2001). "Vision in the ultraviolet". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 58 (11): 1583–1598. doi:10.1007/PL00000798. PMC 11337280. PMID 11706986. S2CID 22938704.

Radiation below 320 nm [ultraviolet (UV)A] is largely screened out by the ozone layer in the Earth's upper atmosphere and is therefore unavailable to the visual system,

- ^ a b Boettner, Edward A.; Wolter, J. Reimer (December 1962). "Transmission of Ocular Media". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1: 776-783.

- ^ Laufer, Gabriel (1996). "Geometrical Optics". Introduction to Optics and Lasers in Engineering. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. Bibcode:1996iole.book.....L. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139174190.004. ISBN 978-0-521-45233-5. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Bradt, Hale (2004). Astronomy Methods: A Physical Approach to Astronomical Observations. Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-521-53551-9. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Ohannesian, Lena; Streeter, Anthony (2001). Handbook of Pharmaceutical Analysis. CRC Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-8247-4194-5. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Ahluwalia, V.K.; Goyal, Madhuri (2000). A Textbook of Organic Chemistry. Narosa. p. 110. ISBN 978-81-7319-159-6. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ a b c Sliney, David H.; Wangemann, Robert T.; Franks, James K.; Wolbarsht, Myron L. (1976). "Visual sensitivity of the eye to infrared laser radiation". Journal of the Optical Society of America. 66 (4): 339–341. Bibcode:1976JOSA...66..339S. doi:10.1364/JOSA.66.000339. PMID 1262982.

The foveal sensitivity to several near-infrared laser wavelengths was measured. It was found that the eye could respond to radiation at wavelengths at least as far as 1,064 nm. A continuous 1,064 nm laser source appeared red, but a 1,060 nm pulsed laser source appeared green, which suggests the presence of second harmonic generation in the retina.

- ^ Lynch, David K.; Livingston, William Charles (2001). Color and Light in Nature (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-521-77504-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

Limits of the eye's overall range of sensitivity extends from about 310 to 1,050 nanometers

- ^ Dash, Madhab Chandra; Dash, Satya Prakash (2009). Fundamentals of Ecology 3E. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-259-08109-5. Archived from the original on 8 October 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

Normally the human eye responds to light rays from 390 to 760 nm. This can be extended to a range of 310 to 1,050 nm under artificial conditions.

- ^ Saidman, Jean (15 May 1933). "Sur la visibilité de l'ultraviolet jusqu'à la longueur d'onde 3130" [The visibility of the ultraviolet to the wave length of 3130]. Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences (in French). 196: 1537–9. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Kurzel, Richard B.; Wolbarsht, Myron L.; Yamanashi, Bill S. (1977). "Ultraviolet Radiation Effects on the Human Eye". Photochemical and Photobiological Reviews. pp. 133–167. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2577-2_3. ISBN 978-1-4684-2579-6.

- ^ Enezi J, Revell V, Brown T, Wynne J, Schlangen L, Lucas R (August 2011). "A "melanopic" spectral efficiency function predicts the sensitivity of melanopsin photoreceptors to polychromatic lights". Journal of Biological Rhythms. 26 (4): 314–323. doi:10.1177/0748730411409719. PMID 21775290. S2CID 22369861.

- ^ Gouras, Peter; Ekesten, Bjorn (December 2004). "Why do mice have ultra-violet vision?". Experimental Eye Research. 79 (6): 887–892. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2004.06.031. PMID 15642326.

- ^ Neitz, Jay; Geist, Timothy; Jacobs, Gerald H. (August 1989). "Color vision in the dog". Visual Neuroscience. 3 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1017/S0952523800004430. PMID 2487095. S2CID 23509491.

- ^ Carroll, Joseph; Murphy, Christopher J.; Neitz, Maureen; Ver Hoeve, James N.; Neitz, Jay (3 October 2001). "Photopigment basis for dichromatic color vision in the horse". Journal of Vision. 1 (2): 80–87. doi:10.1167/1.2.2. PMID 12678603. S2CID 8503174.

- ^ a b Hart, Nathan S.; Hunt, David M. (January 2007). "Avian Visual Pigments: Characteristics, Spectral Tuning, and Evolution". The American Naturalist. 169 (S1): S7 – S26. Bibcode:2007ANat..169S...7H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.502.4314. doi:10.1086/510141. PMID 19426092. S2CID 25779190.

- ^ Cuthill, Innes C (1997). "Ultraviolet vision in birds". In Peter J.B. Slater (ed.). Advances in the Study of Behavior. Vol. 29. Oxford, England: Academic Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-12-004529-7.

- ^ Jamieson, Barrie G. M. (2007). Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny of Birds. Charlottesville VA: University of Virginia. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-57808-386-2.

- ^ a b Carleton, Karen L.; Escobar-Camacho, Daniel; Stieb, Sara M.; Cortesi, Fabio; Marshall, N. Justin (15 April 2020). "Seeing the rainbow: mechanisms underlying spectral sensitivity in teleost fishes". Journal of Experimental Biology. 223 (8) jeb193334. Bibcode:2020JExpB.223B3334C. doi:10.1242/jeb.193334. PMC 7188444. PMID 32327561.

- ^ "True or False? "The common goldfish is the only animal that can see both infra-red and ultra-violet light."". Skeptive. 2013. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ Neumeyer, Christa (2012). "Chapter 2: Color Vision in Goldfish and Other Vertebrates". In Lazareva, Olga; Shimizu, Toru; Wasserman, Edward (eds.). How Animals See the World: Comparative Behavior, Biology, and Evolution of Vision. Oxford Scholarship Online. ISBN 978-0-19-533465-4.

- ^ Briscoe, Adriana D.; Chittka, Lars (January 2001). "The evolution of color vision in insects". Annual Review of Entomology. 46 (1): 471–510. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.46.1.471. PMID 11112177.

- ^ Skorupski, Peter; Chittka, Lars (10 August 2010). "Photoreceptor Spectral Sensitivity in the Bumblebee, Bombus impatiens (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". PLOS ONE. 5 (8) e12049. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512049S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012049. PMC 2919406. PMID 20711523.

- ^ Newman, EA; Hartline, PH (1981). "Integration of visual and infrared information in bimodal neurons in the rattlesnake optic tectum". Science. 213 (4509): 789–91. Bibcode:1981Sci...213..789N. doi:10.1126/science.7256281. PMC 2693128. PMID 7256281.

- ^ Kardong, KV; Mackessy, SP (1991). "The strike behavior of a congenitally blind rattlesnake". Journal of Herpetology. 25 (2): 208–211. doi:10.2307/1564650. JSTOR 1564650.

- ^ Fang, Janet (14 March 2010). "Snake infrared detection unravelled". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.122.

- ^ Krochmal, Aaron R.; George S. Bakken; Travis J. LaDuc (15 November 2004). "Heat in evolution's kitchen: evolutionary perspectives on the functions and origin of the facial pit of pitvipers (Viperidae: Crotalinae)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 207 (Pt 24): 4231–4238. Bibcode:2004JExpB.207.4231K. doi:10.1242/jeb.01278. PMID 15531644.

- ^ Greene HW. (1992). "The ecological and behavioral context for pitviper evolution", in Campbell JA, Brodie ED Jr. Biology of the Pitvipers. Texas: Selva. ISBN 0-9630537-0-1.