Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hadad

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (August 2010) |

| Hadad | |

|---|---|

God of Weather, Hurricanes, Storms, Thunder and Rain | |

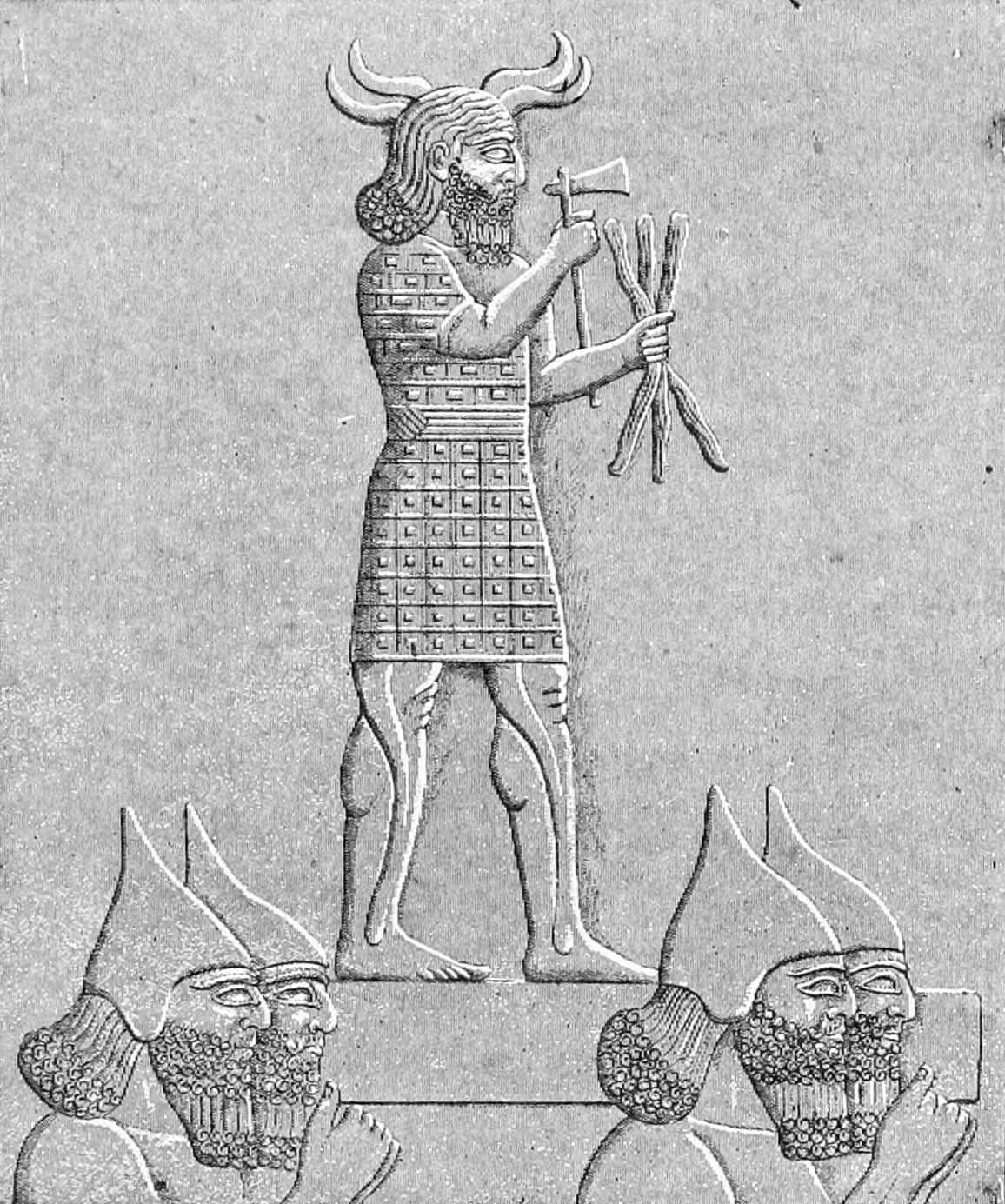

Assyrian soldiers carrying a statue of Adad | |

| Abode | Heaven |

| Symbol | Thunderbolt, bull, lion |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Most common tradition: Sin and Ningal, or Dagon |

| Siblings | Kishar, Inanna |

| Consort | Shala, Medimsha |

| Children | Gibil or Girra |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek | Zeus |

| Roman | Jupiter |

| Egyptian | Horus |

| Hurrian | Teshub |

| Part of a series on Ancient Semitic religion |

| Levantine mythology |

|---|

| Deities |

|

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

Hadad (Ugaritic: 𐎅𐎄, romanized: Haddu), Haddad, Adad (Akkadian: 𒀭𒅎 DIM, pronounced as Adād), or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm- and rain-god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE.[1][2]

From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad.[3][4][5][6] Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram 𒀭𒅎 dIM[7] - the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub.[8] Hadad was also called Rimon/Rimmon, Pidar, Rapiu, Baal-Zephon,[9] or often simply Baʿal (Lord); however, the latter title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded,[10][11] often holding a club and thunderbolt and wearing a bull-horned headdress.[12][13] Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter (Jupiter Dolichenus), as well as the Babylonian Bel.[citation needed]

The Baal Cycle or Epic of Baal is a collection of stories about the Canaanite Baal, also referred to as Hadad. It was composed between 1400 and 1200 B.C. and rediscovered in the excavation of Ugarit, an ancient city in modern-day Syria.

The storm-god Adad and the sun-god Shamash jointly became the patron gods of oracles and divination in Mesopotamia.

Adad in Akkad and Sumer

[edit]In Akkadian, Adad is also known as Rammanu ("Thunderer") cognate with Imperial Aramaic: רעמא Raˁmā and Hebrew: רַעַם Raˁam, a byname of Hadad. Many scholars formerly took Rammanu to be an independent Akkadian god, but he was later identified with Hadad.

Though originating in northern Mesopotamia, Adad was identified by the same Sumerogram dIM that designated Iškur in the south.[14] His worship became widespread in Mesopotamia after the First Babylonian dynasty.[15] A text dating from the reign of Ur-Ninurta characterizes the two sides of Adad/Iškur as threatening in his stormy rage, and benevolent in giving life.[16]

Iškur appears in the list of gods found at Shuruppak but was of far less importance, perhaps because storms and rain were scarce in Sumer and agriculture there depended on irrigation instead. The gods Enlil and Ninurta also had storm god features that diminished Iškur's distinct role, and he sometimes appears as the assistant or companion of these more prominent gods.

When Enki distributed the destinies, he made Iškur inspector of the cosmos. In one litany, Iškur is proclaimed again and again as "great radiant bull, your name is heaven" and also called son of Anu, lord of Karkara; twin-brother of Enki, lord of abundance, lord who rides the storm, lion of heaven.

In other texts Adad/Iškur is sometimes son of the moon god Nanna/Sin by Ningal and brother of Utu/Shamash and Inanna/Ishtar. He is also sometimes described as the son of Enlil.[17]

The bull was portrayed as Adad/Iškur's sacred animal starting in the Old Babylonian period[18] (early 2nd millennium BCE).

Adad/Iškur's consort (both in early Sumerian and the much later Assyrian texts) was the grain goddess Shala, who is also sometimes associated with the god Dagānu. She was also called Gubarra in the earliest texts. The fire god Gibil (Girra in Akkadian) is sometimes the son of Iškur and Shala.

| Part of a series on |

| Religion in Mesopotamia |

|---|

|

He is identified with the Anatolian storm-god Teshub, whom the Mitannians designated with the same Sumerogram dIM.[8] Occasionally he is identified with the Amorite god Amurru.[citation needed]

The Babylonian center of Adad/Iškur's cult was Karkara in the south, his chief temple being É.Kar.kar.a; his spouse Shala was worshipped in a temple named É.Dur.ku. In Assyria, Adad was developed along with his warrior aspect. During the Middle Assyrian Empire, from the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I (1115-1077 BCE), Adad had a double sanctuary with Anu in Assur, and the two are often associated in invocations. The name Adad and various alternate forms (Dadu, Bir, Dadda) are often found in Assyrian king names.

Adad/Iškur presents two aspects in hymns, incantations, and votive inscriptions. On the one hand, he brings rain in due season to fertilize the land; on the other, he sends storms to wreak havoc and destruction. He is pictured on monuments and cylinder seals (sometimes with a horned helmet) with the lightning and the thunderbolt (sometimes in the form of a spear), and in hymns his sombre aspects predominate. His association with the sun-god Shamash, with the two deities alternating in the control of nature, tends to imbue him with some traits of a solar deity.

According to Alberto Green, descriptions of Adad starting in the Kassite period and in the region of Mari emphasize his destructive, stormy character and his role as a fearsome warrior deity,[19] in contrast to Iškur's more peaceful and pastoral character.[20]

Shamash and Adad jointly became the gods of oracles and divination, invoked in all the ceremonies to determine the divine will: through inspecting a sacrificial animal's liver, the action of oil bubbles in a basin of water, or the movements of the heavenly bodies. They are similarly addressed in royal annals and votive inscriptions as bele biri (lords of divination).

Hadad in Ugarit

[edit]

In religious texts, Ba‘al/Hadad is the lord of the sky who governs rain and crops, master of fertility and protector of life and growth. His absence brings drought, starvation, and chaos. Texts of the Baal Cycle from Ugarit are fragmentary and assume much background knowledge.

The supreme god El resides on Mount Lel (Night?) where the assembly of the gods meets. At the beginning of the cycle, there appears to a feud between El and Ba‘al. El appoints one of his sons, called both prince Yamm (Sea) and judge Nahar (River), as king over the gods and changes Yamm's name from yw to mdd ’il (darling of El). El tells his son that he will have to drive off Ba‘al to secure the throne.

In this battle Ba‘al is somehow weakened, but the divine craftsman Kothar-wa-Khasis crafts two magic clubs for Ba’al as weapons that help Ba’al strike down Yamm and Ba'al is supreme. ‘Athtart proclaims Ba‘al's victory and salutes Ba‘al/Hadad as lrkb ‘rpt (Rider on the Clouds), a phrase applied by editors of modern English Bibles to Yahweh in Psalm 68.4. At ‘Athtart's urging Ba‘al "scatters" Yamm and proclaims that he is dead and warmth is assured.

A later passage refers to Ba‘al's victory over Lotan, the many-headed sea dragon. Due to gaps in the text it is not known whether Lotan is another name for Yamm or a character in a similar story. These stories may have been allegories of crops threatened by the winds, storms, and floods from the Mediterranean sea.

A palace is built for Ba‘al with silver, gold, and cedar wood from Mount Lebanon and Sirion. In his new palace Ba‘al hosts a great feast for the other gods. When urged by Kothar-wa-Khasis, Ba’al reluctantly opens a window in his palace and sends forth thunder and lightning. He then invites Mot (Death, the god of drought and the underworld), another son of El, to join the feast.

But Mot, the eater of human flesh and blood, is insulted when offered only bread and wine. He threatens to break Ba‘al to pieces and swallow him, and even Ba‘al cannot stand against Death. Gaps here make interpretation dubious. It seems that by the advice of the sun goddess Shapash, Ba‘al mates with a heifer and dresses the resultant calf in his own clothes as a gift to Mot, and then himself prepares to go down to the underworld in the guise of a helpless shade. News of Ba‘al's apparent death leads even El to mourn. Ba‘al's sister ‘Anat finds Ba‘al's corpse, presumably really the dead calf, and she buries the body with a funeral feast. The god ‘Athtar is appointed to take Ba‘al's place, but he is a poor substitute. Meanwhile, ‘Anat finds Mot, cleaves him with a sword, burns him with fire, and throws his remains to the birds. But the earth is still cracked with drought until Shapsh fetches Ba‘al back.

Seven years later Mot returns and attacks Ba‘al, but the battle is quelled when Shapsh tells Mot that El now supports Ba’al. Mot surrenders to Ba‘al and recognizes him as king.

Hadad in Egypt

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (March 2024) |

In the Amherst Papyrus, Baal Zephon (Hadad) is identified with the Egyptian god Horus: "May Baal from Zephon bless you", Amherst Papyrus 63, 7:3 and in 11:13-14: "and from Zephon may Horus help us". Classical sources translate this name as Zeus Kasios, since in Pelusium, the statue of Zeus Kasios was considered the image of Harpocrates (Horus the Child).[21] Zeus Casius had inherited some traits from Apollo as well. They also recall his conflict with Typhon over that mountain (Mount Casius on the Syrian-Turkish border or Casion near Pelusium in Egypt). The reason why Baal could be both identified with Horus and his rival Set; is because in Egypt the element of the storm was considered foreign as Set was a god of strangers and outsiders, thus because the Egyptians had no better alternative to identify their native god Set with another neighboring deity, they tentatively associated him with Hadad since he was a storm-god, but when the god Baal (Hadad) is not specifically attributed the traits of rain and thunder and is instead perceived as a god of the sky generically, which is what is embodied by his form "Baal Zaphon" as the chief deity who resides on the mountain (for example a 14th-century letter from the king of Ugarit to the Egyptian pharaoh places Baʿal Zaphon as equivalent to Amun also),[22] in that case he's more similar to the Egyptian Horus in that capacity (comparable to Baalshamin as well). The different interpretation could also be based on the fact that Set had been associated with Hadad by the Hyksos. Most likely originally Set referred to another deity also addressed by the title "Baal" (one of the many; an example of this would be the Baal of Tyre) who happened to display storm-like traits especially in Egypt since they were foreign and as such duly emphasized; when instead his weather features probably weren't all that prominent in other cultures who worshipped equivalents of him, but given that the only storm-god available for identification in Semitic culture was Hadad and in Hittite Sutekh (a war-god who's been hypothesized to be an alternative name of Teshub, but it remains unclear), the traits matched the characteristics of the Egyptian deity, and an association between the two was considered plausible, also given by the fact that both the Hittites and Semitic Hyksos were foreigners in the Egyptian land who brought their gods with them, and their main god happened to display storm-like traits and was also associated with these foreigners who came to Egypt, a characteristic that would make him similar to the perception that the Egyptians had of Set. This would once again echo the mythological motif of a previous chief of the Pantheon who gets replaced by the new generation of deities represented by the younger ascendant ruler and newly appointed chief of the gods, as is the case also for the Hittite "Cycle of Kumarbi" where Teshub displaces the previously established father of the gods Kumarbi. In Amherst XII/15 the same identification as before is once again stated: "Baal from Zephon, Horus" (BT mn Şpn Hr).

Hadad in Aram and ancient Israel

[edit]This section uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyse them. (July 2019) |

In the second millennium BCE, the king of Yamhad or Halab (modern Aleppo), who claimed to be "beloved of Hadad", received the tribute of statue of Ishtar from the king of Mari, to be displayed in the temple of Hadad in Halab Citadel.[23][24] Hadad is called "the god of Aleppo" on a stele of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser I.

The element Hadad appears in a number of theophoric names borne by kings of the region. Hadad son of Bedad, who defeated the Midianites in Moab, was the fourth king of Edom. Hadadezer ("Hadad-is-help") was the Aramean king defeated by David. Later Aramean kings of Damascus seem to have habitually assumed the title of Ben-Hadad (son of Hadad). One was Ben-Hadad, the king of Aram whom the Judean king Asa sent to invade the northern Kingdom of Israel.[25] A votive basalt stele from the 9th or 8th century, BCE found in Bredsh north of Aleppo, is dedicated to Melqart and bears the name Ben-Hadad, king of Aram.[26] The seventh of the twelve sons of Ishmael is also named Hadad.

A set of related bynames include Aramaic rmn, Old South Arabic rmn, Hebrew rmwn, and Akkadian Rammānu ("Thunderer"), presumably originally vocalized as Ramān in Aramaic and Hebrew. The Hebrew spelling rmwn with Masoretic vocalization Rimmôn[27] is identical with the Hebrew word meaning 'pomegranate' and may be an intentional misspelling and/or parody of the deity's original name.[28]

The word Hadad-rimmon (or Hadar-rimmon) in the phrase "the mourning of (or at) Hadad-rimmon",[30] has aroused much discussion. According to Jerome and the older Christian interpreters, the mourning is for something that occurred at a place called Hadad-rimmon (Maximianopolis) in the valley of Megiddo. This event was generally held to be the death of Josiah (or, as in the Targum, the death of Ahab at the hands of Hadadrimmon). But even before the discovery of the Ugaritic texts, some suspected that Hadad-rimmon might be a dying-and-rising god like Adonis or Tammuz, perhaps even the same as Tammuz, and the allusion could then be to mournings for Hadad such as those of Adonis festivals.[31] T. K. Cheyne pointed out that the Septuagint reads simply Rimmon, and argues that this may be a corruption of Migdon (Megiddo) and ultimately of Tammuz-Adon. He would render the verse, "In that day there shall be a great mourning in Jerusalem, as the mourning of the women who weep for Tammuz-Adon" (Adon means "lord").[32] No further evidence has come to light to resolve such speculations.

In the Books of Kings, Jezebel – the wife of the Northern Israelite King Ahab promoted the cult of Ba'al in her adopted nation. John Day argues that Jezebel's Baʿal was possibly Baʿal Shamem (Lord of the Heavens), a title most often applied to Hadad.[33]

Sanchuniathon

[edit]In Sanchuniathon's account Hadad is once called Adodos, but is mostly named Demarûs. This is a puzzling form, probably from Ugaritic dmrn, which appears in parallelism with Hadad,[34] or possibly a Greek corruption of Hadad Ramān. Sanchuniathon's Hadad is son of Sky by a concubine who is then given to the god Dagon while she is pregnant by Sky. This appears to be an attempt to combine two accounts of Hadad's parentage, one of which is the Ugaritic tradition that Hadad was son of Dagon.[35] The cognate Akkadian god Adad is also often called the son of Anu ("Sky"). The corresponding Hittite god Teshub is likewise son of Anu (after a fashion).

In Sanchuniathon's account, it is Sky who first fights against Pontus ("Sea"). Then Sky allies himself with Hadad. Hadad takes over the conflict but is defeated, at which point unfortunately no more is said of this matter. Sanchuniathion agrees with Ugaritic tradition in making Muth, the Ugaritic Mot, whom he also calls "Death", the son of El.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sarah Iles Johnston (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780674015173.

- ^ Spencer L. Allen (5 March 2015). The Splintered Divine: A Study of Istar, Baal, and Yahweh Divine Names and Divine Multiplicity in the Ancient Near East. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 10. ISBN 9781614512363.

- ^ Albert T. Clay (1 May 2007). The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 50. ISBN 9781597527187.

- ^ Theophilus G. Pinches (1908). The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Library of Alexandria. p. 15. ISBN 9781465546708.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Joseph Eddy Fontenrose (1959). Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins. University of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 9780520040915.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Green (2003), p. 166.

- ^ ORACC – Iškur/Adad (god)

- ^ a b Green (2003), p. 130.

- ^ Gibson, John C. (1 April 1978). Canaanite Myths and Legends. T&T Clark. p. 208. ISBN 978-0567080899.

- ^ Sacred bull, holy cow: a cultural study of civilization's most important animal. By Donald K. Sharpes –Page 27

- ^ Studies in Biblical and Semitic Symbolism - Page 63. By Maurice H. Farbridge

- ^ Academic Dictionary Of Mythology - Page 126. By Ramesh Chopra

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. By Encyclopædia Britannica, inc – Page 605

- ^ Green (2003), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Green (2003), p. 52.

- ^ Green (2003), p. 54.

- ^ Green (2003), p. 59.

- ^ Green (2003), pp. 18–24.

- ^ Green (2003), pp. 59–60.

- ^ Green (2003), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Kramer 1984, p. 266.

- ^ Niehr (1999), p. 153.

- ^ Trevor Bryce (March 2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. OUP Oxford. p. 111. ISBN 9780199646678.

- ^ Ulf Oldenburg. The Conflict Between El and Ba'al in Canaanite Religion. p. 67.

- ^ 1Kings 15:18

- ^ National Museum, Aleppo, accession number KAI 201.

- ^ 2Kings 5:18

- ^ See Klein, Reuven Chaim (2018). God versus Gods: Judasim in the Age of Idolatry. Mosaica Press. pp. 351–354. ISBN 978-1946351463. OL 27322748M.

- ^ Stefan Jakob Wimmer 2011, Eine Mondgottstele aus et-Turra/Jordanien. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins ZDPV 127/2, 2011, 135-141 - academia.edu

- ^ Zechariah 12:11

- ^ Hitzig on Zechariah 12:2, Isaiah 17:8; Movers, Phonizier, 1.196.

- ^ T. K. Cheyne (1903), Encyclopædia Biblica IV "Rimmon".

- ^ Day (2000), p. 75.

- ^ Oldenburg, Ulf. The conflict between El and Baʿal in Canaanite religion. Brill Archive. pp. 59–. GGKEY:NN7C21Q6FFA. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Schwemer 2007, p. 156.

References

[edit]- Day, John (2000). "Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 265. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850759867..

- Driver, Godfrey Rolles, and John C. L. Gibson. Canaanite Myths and Legends. Edinburgh: Clark, 1978. ISBN 9780567023513.

- Green, Alberto R. W. (2003). The Storm-God in the Ancient Near East. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575060699.

- Hadad, Husni & Mja'is, Salim (1993) Ba'al Haddad, A Study of Ancient Religious History of Syria

- Handy, Lowell K (1994). Among the Host of Heaven: The Syro-Palestinian Pantheon As Bureaucracy. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464843.

- Rabinowitz, Jacob (1998). The Faces of God: Canaanite Mythology As Hebrew Theology. Woodstock, CT: Spring Publications. ISBN 9780882141176..

- Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0802839725..

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Adad". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Niehr, H. (1999), "Baal-zaphon", Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, pp. 152–154.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (1984). Studies in Literature from the Ancient Near East: Dedicated to Samuel Noah Kramer. American Oriental Society. ISBN 978-0-940490-65-9.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2007). "The Storm-Gods of the Ancient Near East: Summary, Synthesis, Recent Studies Part I" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions. 7 (2): 121–168. doi:10.1163/156921207783876404. ISSN 1569-2116.

External links

[edit]- Jewish Encyclopedia

- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Online text: The Epic of Ba'al (Hadad)

- Kadash Kinahu: Complete Directory

- Gateways to Babylon: Adad/Rimon

- Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses: Iškur/Adad (god)

- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- Mesopotamian Gods: Adad (Ishkur)

- Stela with the storm god Adad brandishing thunderbolts Archived 24 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine