Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Boolean network

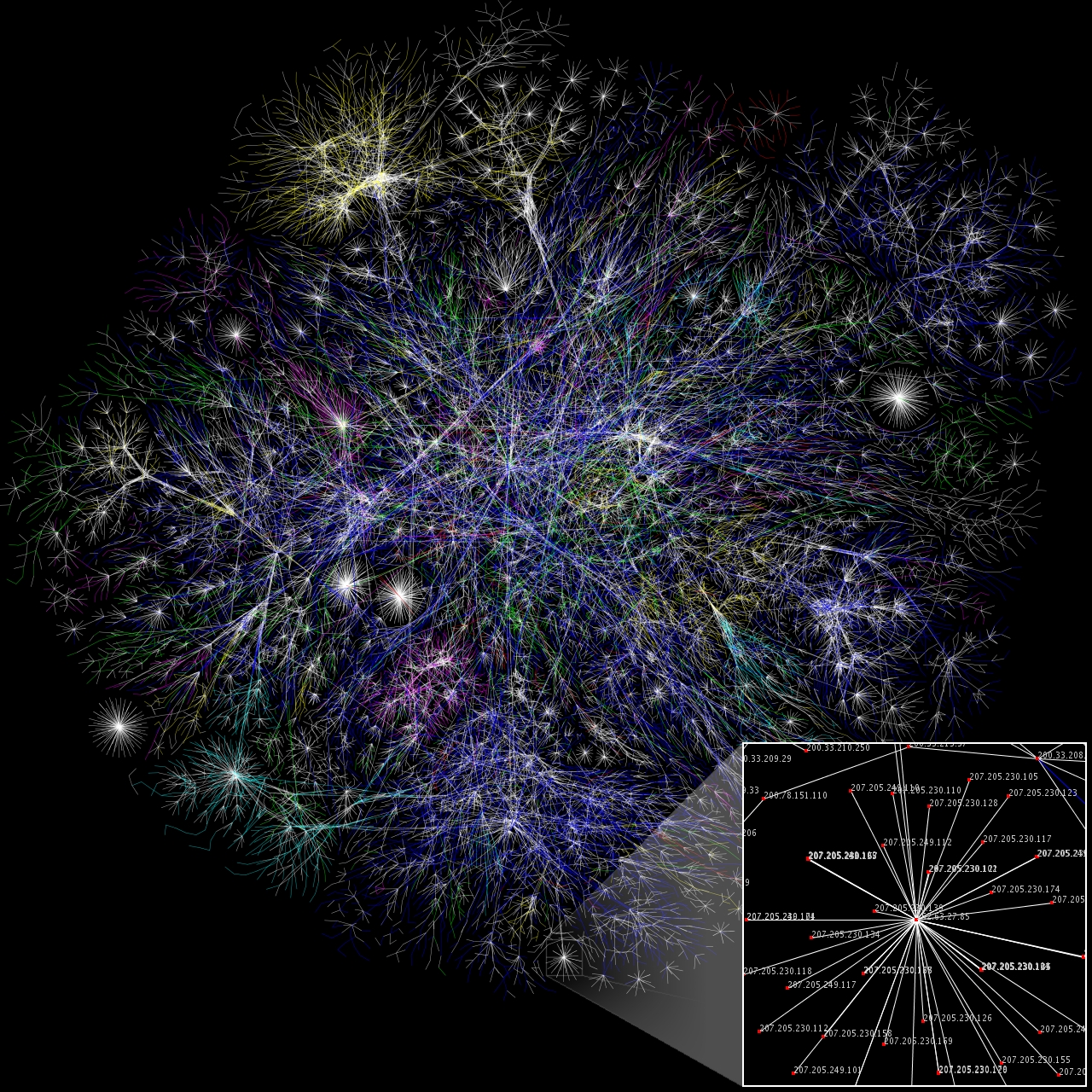

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on | ||||

| Network science | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network types | ||||

| Graphs | ||||

|

||||

| Models | ||||

|

||||

| ||||

A Boolean network consists of a discrete set of Boolean variables each of which has a Boolean function (possibly different for each variable) assigned to it which takes inputs from a subset of those variables and output that determines the state of the variable it is assigned to. This set of functions in effect determines a topology (connectivity) on the set of variables, which then become nodes in a network. Usually, the dynamics of the system is taken as a discrete time series where the state of the entire network at time t+1 is determined by evaluating each variable's function on the state of the network at time t. This may be done synchronously or asynchronously.[1]

Boolean networks have been used in biology to model regulatory networks. Although Boolean networks are a crude simplification of genetic reality where genes are not simple binary switches, there are several cases where they correctly convey the correct pattern of expressed and suppressed genes.[2][3] The seemingly mathematical easy (synchronous) model was only fully understood in the mid 2000s.[4]

Classical model

[edit]A Boolean network is a particular kind of sequential dynamical system, where time and states are discrete, i.e. both the set of variables and the set of states in the time series each have a bijection onto an integer series.

A random Boolean network (RBN) is one that is randomly selected from the set of all possible Boolean networks of a particular size, N. One then can study statistically, how the expected properties of such networks depend on various statistical properties of the ensemble of all possible networks. For example, one may study how the RBN behavior changes as the average connectivity is changed.

The first Boolean networks were proposed by Stuart A. Kauffman in 1969, as random models of genetic regulatory networks[5] but their mathematical understanding only started in the 2000s.[6][7]

Attractors

[edit]Since a Boolean network has only 2N possible states, a trajectory will sooner or later reach a previously visited state, and thus, since the dynamics are deterministic, the trajectory will fall into a steady state or cycle called an attractor (though in the broader field of dynamical systems a cycle is only an attractor if perturbations from it lead back to it). If the attractor has only a single state it is called a point attractor, and if the attractor consists of more than one state it is called a cycle attractor. The set of states that lead to an attractor is called the basin of the attractor. States which occur only at the beginning of trajectories (no trajectories lead to them), are called garden-of-Eden states[8] and the dynamics of the network flow from these states towards attractors. The time it takes to reach an attractor is called transient time.[4]

With growing computer power and increasing understanding of the seemingly simple model, different authors gave different estimates for the mean number and length of the attractors, here a brief summary of key publications.[9]

| Author | Year | Mean attractor length | Mean attractor number | comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kauffman [5] | 1969 | |||

| Bastolla/ Parisi[10] | 1998 | faster than a power law, | faster than a power law, | first numerical evidences |

| Bilke/ Sjunnesson[11] | 2002 | linear with system size, | ||

| Socolar/Kauffman[12] | 2003 | faster than linear, with | ||

| Samuelsson/Troein[13] | 2003 | superpolynomial growth, | mathematical proof | |

| Mihaljev/Drossel[14] | 2005 | faster than a power law, | faster than a power law, | |

| Fink/Sheldon[15] | 2023 | exponential growth, | mathematical proof |

Stability

[edit]In dynamical systems theory, the structure and length of the attractors of a network corresponds to the dynamic phase of the network. The stability of Boolean networks depends on the connections of their nodes. A Boolean network can exhibit stable, critical or chaotic behavior. This phenomenon is governed by a critical value of the average number of connections of nodes (), and can be characterized by the Hamming distance as distance measure. In the unstable regime, the distance between two initially close states on average grows exponentially in time, while in the stable regime it decreases exponentially. In this, with "initially close states" one means that the Hamming distance is small compared with the number of nodes () in the network.

For N-K-model[16] the network is stable if , critical if , and unstable if .

The state of a given node is updated according to its truth table, whose outputs are randomly populated. denotes the probability of assigning an off output to a given series of input signals.

If for every node, the transition between the stable and chaotic range depends on . According to Bernard Derrida and Yves Pomeau[17] , the critical value of the average number of connections is .

If is not constant, and there is no correlation between the in-degrees and out-degrees, the conditions of stability is determined by [18][19][20] The network is stable if , critical if , and unstable if .

The conditions of stability are the same in the case of networks with scale-free topology where the in-and out-degree distribution is a power-law distribution: , and , since every out-link from a node is an in-link to another.[21]

Sensitivity shows the probability that the output of the Boolean function of a given node changes if its input changes. For random Boolean networks, . In the general case, stability of the network is governed by the largest eigenvalue of matrix , where , and is the adjacency matrix of the network.[22] The network is stable if , critical if , unstable if .

Variations of the model

[edit]Other topologies

[edit]One theme is to study different underlying graph topologies.

- The homogeneous case simply refers to a grid which is simply the reduction to the famous Ising model.

- Scale-free topologies may be chosen for Boolean networks.[23] One can distinguish the case where only in-degree distribution in power-law distributed,[24] or only the out-degree-distribution or both.

Other updating schemes

[edit]Classical Boolean networks (sometimes called CRBN, i.e. Classic Random Boolean Network) are synchronously updated. Motivated by the fact that genes don't usually change their state simultaneously,[25] different alternatives have been introduced. A common classification[26] is the following:

- Deterministic asynchronous updated Boolean networks (DRBNs) are not synchronously updated but a deterministic solution still exists. A node i will be updated when t ≡ Qi (mod Pi) where t is the time step.[27]

- The most general case is full stochastic updating (GARBN, general asynchronous random Boolean networks). Here, one (or more) node(s) are selected at each computational step to be updated.

- The Partially-Observed Boolean Dynamical System (POBDS)[28][29][30][31] signal model differs from all previous deterministic and stochastic Boolean network models by removing the assumption of direct observability of the Boolean state vector and allowing uncertainty in the observation process, addressing the scenario encountered in practice.

- Autonomous Boolean networks (ABNs) are updated in continuous time (t is a real number, not an integer), which leads to race conditions and complex dynamical behavior such as deterministic chaos.[32][33]

Application of Boolean Networks

[edit]Classification

[edit]- The Scalable Optimal Bayesian Classification[34] developed an optimal classification of trajectories accounting for potential model uncertainty and also proposed a particle-based trajectory classification that is highly scalable for large networks with much lower complexity than the optimal solution.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Naldi, A.; Monteiro, P. T.; Mussel, C.; Kestler, H. A.; Thieffry, D.; Xenarios, I.; Saez-Rodriguez, J.; Helikar, T.; Chaouiya, C. (25 January 2015). "Cooperative development of logical modelling standards and tools with CoLoMoTo". Bioinformatics. 31 (7): 1154–1159. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btv013. PMID 25619997.

- ^ Albert, Réka; Othmer, Hans G (July 2003). "The topology of the regulatory interactions predicts the expression pattern of the segment polarity genes in Drosophila melanogaster". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 223 (1): 1–18. arXiv:q-bio/0311019. Bibcode:2003JThBi.223....1A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.13.3370. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00035-3. PMC 6388622. PMID 12782112.

- ^ Li, J.; Bench, A. J.; Vassiliou, G. S.; Fourouclas, N.; Ferguson-Smith, A. C.; Green, A. R. (30 April 2004). "Imprinting of the human L3MBTL gene, a polycomb family member located in a region of chromosome 20 deleted in human myeloid malignancies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (19): 7341–7346. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.7341L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308195101. PMC 409920. PMID 15123827.

- ^ a b Drossel, Barbara (December 2009). "Random Boolean Networks". In Schuster, Heinz Georg (ed.). Chapter 3. Random Boolean Networks. Reviews of Nonlinear Dynamics and Complexity. Wiley. pp. 69–110. arXiv:0706.3351. doi:10.1002/9783527626359.ch3. ISBN 978-3-527-62635-9. S2CID 119300231.

- ^ a b Kauffman, Stuart (11 October 1969). "Homeostasis and Differentiation in Random Genetic Control Networks". Nature. 224 (5215): 177–178. Bibcode:1969Natur.224..177K. doi:10.1038/224177a0. PMID 5343519. S2CID 4179318.

- ^ Aldana, Maximo; Coppersmith, Susan; Kadanoff, Leo P. (2003). "Boolean Dynamics with Random Couplings". Perspectives and Problems in Nonlinear Science: A Celebratory Volume in Honor of Lawrence Sirovich. pp. 23–89. arXiv:nlin/0204062. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-21789-5_2. ISBN 978-1-4684-9566-9. S2CID 15024306.

- ^ Gershenson, Carlos (2004). "Introduction to Random Boolean Networks". In Bedau, M., P. Husbands, T. Hutton, S. Kumar, and H. Suzuki (Eds.) Workshop and Tutorial Proceedings, Ninth International Conference on the Simulation and Synthesis of Living Systems (ALife IX). Pp. 2004: 160–173. arXiv:nlin.AO/0408006. Bibcode:2004nlin......8006G.

- ^ Wuensche, Andrew (2011). Exploring discrete dynamics : [the DDLab manual: tools for researching cellular automata, random Boolean and multivalue neworks [sic] and beyond]. Frome, England: Luniver Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-905986-31-6. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ Greil, Florian (2012). "Boolean Networks as Modeling Framework". Frontiers in Plant Science. 3: 178. Bibcode:2012FrPS....3..178G. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00178. PMC 3419389. PMID 22912642.

- ^ Bastolla, U.; Parisi, G. (May 1998). "The modular structure of Kauffman networks". Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 115 (3–4): 219–233. arXiv:cond-mat/9708214. Bibcode:1998PhyD..115..219B. doi:10.1016/S0167-2789(97)00242-X. S2CID 1585753.

- ^ Bilke, Sven; Sjunnesson, Fredrik (December 2001). "Stability of the Kauffman model". Physical Review E. 65 (1) 016129. arXiv:cond-mat/0107035. Bibcode:2001PhRvE..65a6129B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.65.016129. PMID 11800758. S2CID 2470586.

- ^ Socolar, J.; Kauffman, S. (February 2003). "Scaling in Ordered and Critical Random Boolean Networks". Physical Review Letters. 90 (6) 068702. arXiv:cond-mat/0212306. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90f8702S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.068702. PMID 12633339. S2CID 14392074.

- ^ Samuelsson, Björn; Troein, Carl (March 2003). "Superpolynomial Growth in the Number of Attractors in Kauffman Networks". Physical Review Letters. 90 (9) 098701. Bibcode:2003PhRvL..90i8701S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.098701. PMID 12689263.

- ^ Mihaljev, Tamara; Drossel, Barbara (October 2006). "Scaling in a general class of critical random Boolean networks". Physical Review E. 74 (4) 046101. arXiv:cond-mat/0606612. Bibcode:2006PhRvE..74d6101M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.74.046101. PMID 17155127. S2CID 17739744.

- ^ Fink, T; Sheldon, F (December 2023). "Number of attractors in the critical Kauffman model is exponential". Physical Review Letters. 131 (26) 267402. arXiv:2306.01629. Bibcode:2023PhRvL.131z7402F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.267402. PMID 38215388.

- ^ Kauffman, S. A. (1969). "Metabolic stability and epigenesis in randomly constructed genetic nets". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 22 (3): 437–467. Bibcode:1969JThBi..22..437K. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(69)90015-0. PMID 5803332.

- ^ Derrida, B; Pomeau, Y (1986-01-15). "Random Networks of Automata: A Simple Annealed Approximation". Europhysics Letters. 1 (2): 45–49. Bibcode:1986EL......1...45D. doi:10.1209/0295-5075/1/2/001. S2CID 160018158. Archived from the original on 2020-05-17. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- ^ Solé, Ricard V.; Luque, Bartolo (1995-01-02). "Phase transitions and antichaos in generalized Kauffman networks". Physics Letters A. 196 (5–6): 331–334. Bibcode:1995PhLA..196..331S. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(94)00876-Q.

- ^ Luque, Bartolo; Solé, Ricard V. (1997-01-01). "Phase transitions in random networks: Simple analytic determination of critical points". Physical Review E. 55 (1): 257–260. Bibcode:1997PhRvE..55..257L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.55.257.

- ^ Fox, Jeffrey J.; Hill, Colin C. (2001-12-01). "From topology to dynamics in biochemical networks". Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science. 11 (4): 809–815. Bibcode:2001Chaos..11..809F. doi:10.1063/1.1414882. ISSN 1054-1500. PMID 12779520.

- ^ Aldana, Maximino; Cluzel, Philippe (2003-07-22). "A natural class of robust networks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (15): 8710–8714. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.8710A. doi:10.1073/pnas.1536783100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 166377. PMID 12853565.

- ^ Pomerance, Andrew; Ott, Edward; Girvan, Michelle; Losert, Wolfgang (2009-05-19). "The effect of network topology on the stability of discrete state models of genetic control". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (20): 8209–8214. arXiv:0901.4362. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.8209P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900142106. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2688895. PMID 19416903.

- ^ Aldana, Maximino (October 2003). "Boolean dynamics of networks with scale-free topology". Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 185 (1): 45–66. arXiv:cond-mat/0209571. Bibcode:2003PhyD..185...45A. doi:10.1016/s0167-2789(03)00174-x.

- ^ Drossel, Barbara; Greil, Florian (4 August 2009). "Critical Boolean networks with scale-free in-degree distribution". Physical Review E. 80 (2) 026102. arXiv:0901.0387. Bibcode:2009PhRvE..80b6102D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.80.026102. PMID 19792195. S2CID 2487442.

- ^ Harvey, Imman; Bossomaier, Terry (1997). "Time out of joint: Attractors in asynchronous random Boolean networks". In Husbands, Phil; Harvey, Imman (eds.). Proceedings of the Fourth European Conference on Artificial Life (ECAL97). MIT Press. pp. 67–75. ISBN 978-0-262-58157-8. Archived from the original on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Gershenson, Carlos (2002). "Classification of Random Boolean Networks". In Standish, Russell K; Bedau, Mark A (eds.). Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Artificial Life. Vol. 8. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. pp. 1–8. arXiv:cs/0208001. Bibcode:2002cs........8001G. ISBN 978-0-262-69281-6. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gershenson, Carlos; Broekaert, Jan; Aerts, Diederik (14 September 2003). "Contextual Random Boolean Networks". Advances in Artificial Life [7th European Conference, ECAL 2003]. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2801. Dortmund, Germany. pp. 615–624. arXiv:nlin/0303021. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-39432-7_66. ISBN 978-3-540-39432-7. S2CID 4309400.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Imani, M.; Braga-Neto, U. M. (2017-01-01). "Maximum-Likelihood Adaptive Filter for Partially Observed Boolean Dynamical Systems". IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing. 65 (2): 359–371. arXiv:1702.07269. Bibcode:2017ITSP...65..359I. doi:10.1109/TSP.2016.2614798. ISSN 1053-587X. S2CID 178376.

- ^ Imani, M.; Braga-Neto, U. M. (2015). "Optimal state estimation for boolean dynamical systems using a boolean Kalman smoother". 2015 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP). pp. 972–976. doi:10.1109/GlobalSIP.2015.7418342. ISBN 978-1-4799-7591-4. S2CID 8672734.

- ^ Imani, M.; Braga-Neto, U. M. (2016). 2016 American Control Conference (ACC). pp. 227–232. doi:10.1109/ACC.2016.7524920. ISBN 978-1-4673-8682-1. S2CID 7210088.

- ^ Imani, M.; Braga-Neto, U. (2016-12-01). "Point-based value iteration for partially-observed Boolean dynamical systems with finite observation space". 2016 IEEE 55th Conference on Decision and Control (CDC). pp. 4208–4213. doi:10.1109/CDC.2016.7798908. ISBN 978-1-5090-1837-6. S2CID 11341805.

- ^ Zhang, Rui; Cavalcante, Hugo L. D. de S.; Gao, Zheng; Gauthier, Daniel J.; Socolar, Joshua E. S.; Adams, Matthew M.; Lathrop, Daniel P. (2009). "Boolean chaos". Physical Review E. 80 (4) 045202. arXiv:0906.4124. Bibcode:2009PhRvE..80d5202Z. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.80.045202. ISSN 1539-3755. PMID 19905381. S2CID 43022955.

- ^ Cavalcante, Hugo L. D. de S.; Gauthier, Daniel J.; Socolar, Joshua E. S.; Zhang, Rui (2010). "On the origin of chaos in autonomous Boolean networks". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 368 (1911): 495–513. arXiv:0909.2269. Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368..495C. doi:10.1098/rsta.2009.0235. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 20008414. S2CID 426841.

- ^ Hajiramezanali, E. & Imani, M. & Braga-Neto, U. & Qian, X. & Dougherty, E.. Scalable Optimal Bayesian Classification of Single-Cell Trajectories under Regulatory Model Uncertainty. ACMBCB'18. https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=3233689 Archived 2021-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Dubrova, E., Teslenko, M., Martinelli, A., (2005). *Kauffman Networks: Analysis and Applications, in "Proceedings of International Conference on Computer-Aided Design", pages 479-484.

External links

[edit]- Analysis of Dynamic Algebraic Models (ADAM) v1.1

- bioasp/bonesis: Synthesis of Most Permissive Boolean Networks from network architecture and dynamical properties

- CoLoMoTo (Consortium for Logical Models and Tools)

- DDLab

- NetBuilder Boolean Networks Simulator

- Open Source Boolean Network Simulator

- JavaScript Kauffman Network

- Probabilistic Boolean Networks (PBN)

- RBNLab

- A SAT-based tool for computing attractors in Boolean Networks

Boolean network

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A Boolean network is a discrete dynamical system composed of a finite number of nodes, each representing a binary state variable that can take one of two values, conventionally denoted as 0 (inactive or off) or 1 (active or on). These nodes interact through directed connections, where the future state of each node is governed by a predefined Boolean function that evaluates the current states of its input nodes, thereby modeling regulatory relationships such as activation or inhibition.[4] This framework was originally introduced by Stuart Kauffman in 1969 as a means to model random genetic regulatory networks, capturing the emergent behavior of large-scale biological systems through simple logical rules.[5] Mathematically, a Boolean network with nodes is defined by the state update rule for each node : where represents the global state vector at time , and is the Boolean function assigned to node , typically depending only on a subset of the nodes (its inputs).[5] A basic example is a two-node network implementing a mutual inhibition toggle switch, where node 1's function is the logical negation of node 2's state (), and node 2's function is the negation of node 1's state (). From an initial state of (0, 0), the network transitions to (1, 1) in the next step, then returns to (0, 0), forming a cycle of period 2; starting from (0, 1) remains at (0, 1), and (1, 0) remains at (1, 0), illustrating bistable fixed points alongside an oscillatory cycle.Historical Development

The concept of Boolean networks draws foundational inspiration from earlier models in computational neuroscience and automata theory. In 1943, Warren S. McCulloch and Walter Pitts proposed a model of neural activity where neurons function as binary logic units, performing Boolean operations such as AND, OR, and NOT, which laid the groundwork for representing complex information processing through discrete logical gates. This binary threshold model influenced subsequent efforts to simulate biological regulation via interconnected logical elements. Similarly, John von Neumann's work in the 1940s and 1950s on self-reproducing cellular automata explored how simple rules could generate emergent complexity in automata, providing a theoretical basis for studying self-organizing systems that paralleled the regulatory dynamics later modeled in Boolean networks. The formal introduction of Boolean networks as a tool for biological modeling occurred in 1969 through Stuart Kauffman's seminal paper, "Metabolic Stability and Epigenesis in Randomly Constructed Genetic Nets," where he proposed random Boolean networks to simulate gene regulatory interactions in developmental biology. Kauffman envisioned these networks as directed graphs of genes, each acting as a node with a Boolean function determining its state based on inputs from other genes, aiming to explain epigenetic stability and differentiation in cellular systems. Central to his framework was the conjecture that networks with an average of two inputs per node (K=2) exhibit critical dynamics poised at the "edge of chaos," balancing ordered behavior with adaptability, which he argued mirrors the complexity of living systems. In the 1990s, Boolean networks gained traction in genomics amid the rise of high-throughput sequencing and the Human Genome Project, enabling inference of regulatory structures from expression data; for instance, algorithms were developed to reconstruct Boolean models from time-series microarray data, marking a shift toward data-driven applications in gene network analysis.[6] By the 2000s, integration with systems biology accelerated, as probabilistic extensions of Boolean networks incorporated uncertainty in gene interactions, facilitating modeling of pathways like the mammalian cell cycle and cancer signaling, thus embedding the framework within broader computational biology pipelines.Core Components

Nodes and Boolean Functions

In a Boolean network, nodes represent the fundamental entities being modeled, such as genes in a regulatory system, each assigned a binary state from the set , conventionally interpreted as "off" or inactive (0) and "on" or active (1).90015-0) This binary representation simplifies continuous biological processes into discrete logical states, enabling the analysis of qualitative dynamics without requiring quantitative measurements of expression levels.[7] Each node is governed by a Boolean function , where denotes the number of inputs (in-degree) from other nodes that influence its state.90015-0) These functions encapsulate the regulatory logic, mapping the binary states of the input nodes to a single binary output for node . Common Boolean functions include basic logical gates such as AND, which outputs 1 only if all inputs are 1; OR, which outputs 1 if at least one input is 1; and NOT, which inverts a single input (outputs 1 if the input is 0, and vice versa).[8] A notable class of Boolean functions in biological contexts is canalizing functions, where at least one input variable canalizes the output—meaning that for a specific value of that input (the "canalizing variable"), the output is fixed regardless of the other inputs' values. For example, in the function , if , the output is always 1 irrespective of and ; here, is the canalizing variable with canalizing value 1. Canalizing functions promote stability in networks by reducing sensitivity to perturbations in non-canalizing inputs, a property observed in models of gene regulation. To illustrate, consider a node with two inputs governed by the XOR (exclusive OR) function, which outputs 1 only if the inputs differ. The truth table for this function is:| Input A | Input B | Output (A XOR B) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

![{\displaystyle K_{c}=1/[2p(1-p)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c2bd3f5ed2909d2e20e8641b9788d1ba3fca171d)