Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Citron

View on Wikipedia

| Citron | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Rutaceae |

| Genus: | Citrus |

| Species: | C. medica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Citrus medica | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

The citron (Citrus medica), historically cedrate,[4] is a large fragrant citrus fruit with a thick rind. It is said to resemble a 'huge, rough lemon'.[5] It is one of the original citrus fruits from which all other citrus types developed through natural hybrid speciation or artificial hybridization.[6] Though citron cultivars take on a wide variety of physical forms, they are all closely related genetically. It is used in Asian and Mediterranean cuisine, traditional medicines, perfume, and religious rituals and offerings. Hybrids of citrons with other citrus are commercially more prominent, notably lemons and many limes.

Etymology

[edit]The fruit's name is derived from the Latin citrus, which is also the origin of the genus name. The binomial name Citrus medica derives from Media, the kingdom of the Medes, where it was believed to originate (but see "Origin and distribution" below).[7]

Other languages

[edit]A source of confusion is that 'citron' in French and English are false friends, as the French word 'citron' refers to what in English is a lemon; whereas the French word for the citron is 'cédrat'. Into the 16th century, the English term citron included the lemon and perhaps the lime as well.[8][failed verification] Other languages that use variants of citron to refer to the lemon include Armenian, Czech, Dutch, Finnish, German, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Hungarian, Esperanto, Polish and the Scandinavian languages.[9]

In Italian it is known as cedro, the same name used also to indicate the coniferous tree cedar. Similarly, in Latin, citrus, or thyine wood referred to the wood of a North African cypress, Tetraclinis articulata. In Indo-Iranian languages, it is called toranj, as against naranj ('bitter orange'). Both names were borrowed into Arabic and introduced into Spain and Portugal after their occupation by Muslims in AD 711, whence the latter became the source of the name orange through rebracketing (and the former of 'toronja' and 'toranja', which today describe the grapefruit in Spanish and Portuguese respectively).[10]

Dutch merchants seasonally import Sukade for baked goods; a thick, light green colored commercially candied half peeling from Indonesia and other countries (sukade – Indonesian word for love, Citrus médica variety 'Macrocárpa'), which can reach 2.5 kilograms mass. A bitter taste is removed by salt treatment before processing into confectionery.[11]

In Hebrew it is called an Etrog (אתרוג); in Yiddish, it is pronounced "esrog" or "esreg". The citron plays an important role in the harvest holiday of Sukkot paired with lulavim (fronds of the date palm).

Origin and distribution

[edit]

The citron is an old and original citrus species.[13]

There is molecular evidence that most cultivated citrus species arose by hybridization of a small number of ancestral types: the citron, pomelo, mandarin and, to a lesser extent, papedas and kumquat. The citron is usually fertilized by self-pollination, which results in their displaying a high degree of genetic homozygosity. It is the male parent of any citrus hybrid rather than a female one.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

Archaeological evidence for citrus fruits has been limited, as neither seeds nor pollen are likely to be routinely recovered in archaeology.[21] The citron is thought to have been native to the southeast foothills of the Himalayas.[20] Despite its scientific designation, which is an adaptation of the old name in classical Greek sources “Median pome”, this fruit was not indigenous to Media or ancient Media;[22][23] it was mostly cultivated on shores of the Caspian Sea (north of Mazandarn and Gilan) on its way to the Mediterranean basin, where it was cultivated during the later centuries in different areas as described by Erich Isaac.[24] Many mention the role of Alexander the Great and his armies as they attacked Iran and what is today Pakistan, as being responsible for the spread of the citron westward, reaching the European countries such as Greece and Italy.[25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

Antiquity

[edit]Leviticus mentions the "fruit of the beautiful ('hadar') tree" as being required for ritual use during the Feast of Tabernacles (Lev. 23:40). According to Jewish Rabbinical tradition, the "fruit of the tree hadar" refers to the citron. Mishna Sukkah, c. 2nd century AD, deals with halakhic aspects of the citron.

The Egyptologist and archaeologist Victor Loret said he had identified it depicted on the walls of the botanical garden at the Karnak Temple, which dates back to the time of Thutmosis III, approximately 3,500 years ago.[33] Citron was also cultivated in Sumer as early as the 3rd millennium BC.

The citron has been cultivated since ancient times, predating the cultivation of other citrus species.[34]

Theophrastus

[edit]The following description on citron was given by Theophrastus[35]

In the east and south there are special plants ... i.e. in Media and Persia there are many types of fruit, between them there is a fruit called Median or Persian Apple. The tree has a leaf similar to and almost identical with that of the andrachn (Arbutus andrachne L.), but has thorns like those of the apios (the wild pear, Pyrus amygdaliformis Vill.) or the firethorn (Cotoneaster pyracantha Spach.), except that they are white, smooth, sharp and strong. The fruit is not eaten, but is very fragrant, as is also the leaf of the tree; and the fruit is put among clothes, it keeps them from being moth-eaten. It is also useful when one has drunk deadly poison, for when it is administered in wine; it upsets the stomach and brings up the poison. It is also useful to improve the breath, for if one boils the inner part of the fruit in a dish or squeezes it into the mouth in some other medium, it makes the breath more pleasant.

The seed is removed from the fruit and sown in the spring in carefully tilled beds, and it is watered every fourth or fifth day. As soon the plant is strong it is transplanted, also in the spring, to a soft, well watered site, where the soil is not very fine, for it prefers such places.

And it bears its fruit at all seasons, for when some have gathered, the flower of the others is on the tree and is ripening others. Of the flowers I have said[36] those that have a sort of distaff [meaning the pistil] projecting from the middle are fertile, while those that do not have this are sterile. It is also sown, like date palms, in pots punctured with holes.

This tree, as has been remarked, grows in Media and Persia.

Pliny the Elder

[edit]Citron was also described by Pliny the Elder, who called it nata Assyria malus. The following is from his book Natural History:

There is another tree also with the same name of "citrus", and bears a fruit that is held by some persons in particular dislike for its smell and remarkable bitterness; while, on the other hand, there are some who esteem it very highly. This tree is used as an ornament to houses; it requires, however, no further description.[37]

The citron tree, called the Assyrian, and by some the Median or Persian apple, is an antidote against poisons. The leaf is similar to that of the arbute, except that it has small prickles running across it. As to the fruit, it is never eaten, but it is remarkable for its extremely powerful smell, which is the case, also, with the leaves; indeed, the odour is so strong, that it will penetrate clothes, when they are once impregnated with it, and hence it is very useful in repelling the attacks of noxious insects.

The tree bears fruit at all seasons of the year; while some is falling off, other fruit is ripening, and other, again, just bursting into birth. Various nations have attempted to naturalize this tree among them, for the sake of its medica or Persian properties, by planting it in pots of clay, with holes drilled in them, for the purpose of introducing the air to the roots; and I would here remark, once for all, that it is as well to remember that the best plan is to pack all slips of trees that have to be carried to any distance, as close together as they can possibly be placed.

It has been found, however, that this tree will grow nowhere except in Persia. It is this fruit, the pips of which, as we have already mentioned, the Parthian grandees employ in seasoning their ragouts, as being peculiarly conducive to the sweetening of the breath. We find no other tree very highly commended that is produced in Media.[38]

Citrons, either the pulp of them or the pips, are taken in wine as an antidote to poisons. A decoction of citrons, or the juice extracted from them, is used as a gargle to impart sweetness to the breath. The pips of this fruit are recommended for pregnant women to chew when affected with qualmishness. Citrons are good, also, for a weak stomach, but it is not easy to eat them except with vinegar.[39]

Medieval authors

[edit]Ibn al-'Awwam's 12th-century agricultural encyclopedia, Book on Agriculture, contains an article on citron tree cultivation in Spain.[40]

Description and variation

[edit]

Fruit

[edit]The citron fruit is usually ovate or oblong, narrowing towards the stylar end. However, the citron's fruit shape is highly variable, due to the large quantity of albedo, which forms independently according to the fruits' position on the tree, twig orientation, and many other factors. The rind is leathery, furrowed, and adherent. The inner portion is thick, white and hard; the outer is uniformly thin and very fragrant. The pulp is usually acidic, but also can be sweet, and some varieties are entirely pulpless.

Most citron varieties contain a large number of monoembryonic seeds. The seeds are white with dark inner coats and red-purplish chalazal spots for the acidic varieties, and colorless for the sweet ones. Some citron varieties have persistent styles which do not fall off after fecundation. Those are usually preferred for ritual etrog use in Judaism.

Some citrons have medium-sized oil bubbles at the outer surface, medially distant to each other. Some varieties are ribbed and faintly warted on the outer surface. A fingered citron variety is commonly called Buddha's hand.

The color varies from green, when unripe, to a yellow-orange when overripe. The citron does not fall off the tree and can reach 8–10 pounds (4–5 kg) if not picked before fully mature.[41][14] However, they should be picked before the winter, as the branches might bend or break to the ground, and may cause numerous fungal diseases for the tree.

Despite the wide variety of forms taken on by the fruit, citrons are all closely related genetically, representing a single species.[20][42] Genetic analysis divides the known cultivars into three clusters: a Mediterranean cluster thought to have originated in India, and two clusters predominantly found in China, one representing the fingered citrons, and another consisting of non-fingered varieties.[42]

Plant

[edit]

Citrus medica is a slow-growing shrub or small tree that reaches a height of about 2.5 to 4.5 metres (8 to 15 feet). It has irregular straggling branches and stiff twigs and long spines at the leaf axils. The evergreen leaves are green and lemon-scented with slightly serrate edges, ovate-lanceolate or ovate elliptic 60 to 180 millimetres (2+1⁄2–7 in) long. Petioles are usually wingless or with minor wings. The clustered flowers of the acidic varieties are purplish tinted from outside, but the sweet ones are white-yellowish.

| Citron varieties |

|---|

|

| Acidic-pulp varieties |

| Non-acidic varieties |

| Pulpless varieties |

| Citron hybrids |

| Related articles |

The citron tree is very vigorous with almost no dormancy, blooming several times a year, and is therefore fragile and extremely sensitive to frost.[43]

Varieties and hybrids

[edit]The acidic varieties include the Florentine and Diamante citron from Italy, the Greek citron and the Balady citron from Israel.[44] The sweet varieties include the Corsican and Moroccan citrons. The pulpless varieties also include some fingered varieties and the Yemenite citron.

There are also a number of citron hybrids; for example, ponderosa lemon, the lumia and rhobs el Arsa are known citron hybrids. Some claim[45] that even the Florentine citron is not pure citron, but a citron hybrid.

Uses

[edit]Culinary

[edit]While the lemon and orange are primarily peeled to consume their pulpy and juicy segments, the citron's pulp is dry, containing a small quantity of juice, if any. The main content of a citron fruit is its thick white rind, which adheres to the segments and cannot easily be separated from them. The citron gets halved and depulped, then its rind (the thicker the better) is cut into pieces. Those are cooked in sugar syrup and used as a spoon sweet known in Greek as "kítro glykó" (κίτρο γλυκό), or diced and candied with sugar and used as a confection in cakes. In Italy, a soft drink called "Cedrata" is made from the fruit[46] as well as a dense and powerful citron liqueur called “cedro” or “cedrello”.[7]

In Samoa a refreshing drink called "vai tipolo" is made from squeezed juice. It is also added to a raw fish dish called "oka" and to a variation of palusami or luáu.

Citron is a regularly used item in Asian cuisine.

Today the citron is also used for the fragrance or zest of its flavedo, but the most important part is still the inner rind (known as pith or albedo), which is a fairly important article in international trade and is widely employed in the food industry as succade,[25] as it is known when it is candied in sugar.

The dozens of varieties of citron are collectively known as Lebu in Bangladesh, West Bengal, where it is the primary citrus fruit.

In Iran the citron's thick white rind is used to make jam; in Pakistan the fruit is used to make jam but is also pickled; in South Indian cuisine, some varieties of citron (collectively referred to as "Narthangai" in Tamil and "Heralikayi" in Kannada) are widely used in pickles and preserves. In Karnataka, heralikayi (citron) is used to make lemon rice. In Kutch, Gujarat, it is used to make pickle, wherein entire slices of fruits are salted, dried and mixed with jaggery and spices to make sweet spicy pickle.[47] In the United States, citron is an important ingredient in holiday fruitcakes.

-

A citron halved and depulped, cooked in sugar

-

Cedrata, a citron soft drink from Italy

-

Citron torte

Medicine

[edit]From ancient through medieval times, the citron was used mainly for supposed medical purposes to combat seasickness, scurvy and other disorders. Pietro Andrea Mattioli's Commentaries (1544) recommended using the essential oil of citrons to preserve dead bodies and suggested using it as a contraceptive.[7]

Citron and its bioactive phytochemicals have demonstrated activity against various pathogenic microorganisms.[48] The juice of the citron has a high content of vitamin C and dietary fiber (pectin) which can be extracted from the thick albedo of the citron.[49]

Religious

[edit]In Judaism

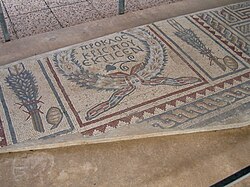

[edit]The citron (the word for which in Hebrew is etrog) is used by Jews for a religious ritual during the Jewish harvest holiday of Sukkot, the Feast of Tabernacles; therefore, it is considered to be a Jewish symbol, one found on various Hebrew antiques and archaeological findings.[50]

In Buddhism

[edit]A variety of citron native to China has sections that separate into finger-like parts and is used as an offering in Buddhist temples.[51]

In Hinduism

[edit]In Nepal, the citron (Nepali: बिमिरो, romanized: bimiro) is worshipped during the Bhai Tika ceremony during Tihar.[52] The worship is thought to stem from the belief that it is a favorite of Yama, Hindu god of death, and his sister Yami.[53]

Perfumery

[edit]For many centuries, citron's fragrant essential oil (oil of cedrate) has been used in perfumery, the same oil that was used medicinally for its antibiotic properties. Its major constituent is limonene.[54]

See also

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

In a German market, for culinary use

-

In fruit market of Italy

-

Naxos citrons and leaf

-

A wild citron in India

-

Citron flowers

-

Unknown citron type in pot

-

Citron growing in Uttarakhand,

Citations

[edit]- ^ Plummer, J. 2021. Citrus medica. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T62041221A62041228. Downloaded on 06 September 2021.

- ^ Ollitrault, Patrick; Curk, Franck; Krueger, Robert (2020). "Citrus taxonomy". In Talon, Manuel; Caruso, Marco; Gmitter, Fred G Jr. (eds.). The Citrus Genus. Elsevier. pp. 57–81. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-812163-4.00004-8. ISBN 9780128121634. S2CID 242819146.

- ^ "Citrus medica L. Sp. Pl. : 782 (1753)". World Flora Online. World Flora Consortium. 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Cedrate". Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2014). Tom Jaine (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Food. Illustrated by Soun Vannithone (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-19-967733-7. OCLC 890807357.

- ^ Klein, J. (2014). "Citron Cultivation, Production and Uses in the Mediterranean Region". In Z. Yaniv; N. Dudai (eds.). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the Middle-East. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of the World. Vol. 2. Springer Netherlands. pp. 199–214. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-9276-9_10. ISBN 978-94-017-9275-2.

- ^ a b c Attlee, Helena (2015). The land where lemons grow: the story of Italy and its citrus fruit. London: Penguin Books. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-241-95257-3.

- ^ "Home : Oxford English Dictionary". oed.com.

- ^ ""Lemon" in European languages". Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ "Citrus medica" (PDF). plantlives.com. 2 October 2021. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021.

- ^ Hvass, Else (1965). Nuttige Planten In Kleur (nedersland ed.). Amsterdam: Mousault. pp. 76, 161. ISBN 9789022610220.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Castillo, Cristina; Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Qin, Ling; Weisskopf, Alison (2017). "Charred pomelo peel, historical linguistics and other tree crops: approaches to framing the historical context of early Citrus cultivation in East, South and Southeast Asia". In Zech-Matterne, Véronique; Fiorentino, Girolamo (eds.). AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean (PDF). Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. pp. 29–48. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.2107. hdl:11573/1077421. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ Chambers, William and Robert (1862). Chambers's Encyclopedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge for the People. London: W. and R. Chambers. p. 55, vol. 3.

- ^ a b The Search for the Authentic Citron: Historic and Genetic Analysis; HortScience 40(7):1963–1968. 2005

- ^ E. Nicolosi; Z. N. Deng; A. Gentile; S. La Malfa; G. Continella; E. Tribulato (June 2000). "Citrus phylogeny and genetic origin of important species as investigated by molecular markers". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 100 (8): 1155–1166. doi:10.1007/s001220051419. S2CID 24057066.

- ^ Noelle A. Barkley; Mikeal L. Roose; Robert R. Krueger; Claire T. Federici (May 2006). "Assessing genetic diversity and population structure in a citrus germplasm collection utilizing simple sequence repeat markers (SSRs)". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 112 (8): 1519–1531. doi:10.1007/s00122-006-0255-9. PMID 16699791. S2CID 7667126. Archived from the original on 2021-03-09. Retrieved 2018-12-04.

- ^ Asad Asadi Abkenar; Shiro Isshiki; Yosuke Tashiro (1 November 2004). "Phylogenetic relationships in the 'true citrus fruit trees' revealed by PCR-RFLP analysis of cpDNA". Scientia Horticulturae. 102 (2): 233–242. Bibcode:2004ScHor.102..233A. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2004.01.003.

- ^ C. A. Krug (June 1943). "Chromosome Numbers in the Subfamily Aurantioideae with Special Reference to the Genus Citrus". Botanical Gazette. 104 (4): 602–611. doi:10.1086/335173. JSTOR 2472147. S2CID 84015769.

- ^ R. Carvalho; W. S. Soares Filho; A. C. Brasileiro-Vidal; M. Guerra (March 2005). "The relationships among lemons, limes and citron: a chromosomal comparison". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 109 (1–3): 276–282. doi:10.1159/000082410. PMID 15753587. S2CID 26046238.

- ^ a b c Wu, Guohong Albert; Terol, Javier; Ibanez, Victoria; López-García, Antonio; Pérez-Román, Estela; Borredá, Carles; Domingo, Concha; Tadeo, Francisco R; Carbonell-Caballero, Jose; Alonso, Roberto; Curk, Franck; Du, Dongliang; Ollitrault, Patrick; Roose, Mikeal L. Roose; Dopazo, Joaquin; Gmitter Jr, Frederick G.; Rokhsar, Daniel; Talon, Manuel (2018). "Genomics of the origin and evolution of Citrus". Nature. 554 (7692): 311–316. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..311W. doi:10.1038/nature25447. hdl:20.500.11939/5741. PMID 29414943.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Castillo, Cristina; Kingwell-Banham, Eleanor; Qin, Ling; Weisskopf, Alison (15 January 2018). "Charred pummelo peel, historical linguistics and other tree crops: Approaches to framing the historical context of early Citrus cultivation in East, South and Southeast Asia". AGRUMED: Archaeology and history of citrus fruit in the Mediterranean : Acclimatization, diversifications, uses. Publications du Centre Jean Bérard. ISBN 9782918887775.

- ^ "Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ Inquiry into Plants 4.iv.2.

- ^ Erich Isaac (January 1959). "The Citron in the Mediterranean: a study in religious influences". Economic Geography. 35 (1): 71–78. doi:10.2307/142080. JSTOR 142080.

- ^ a b "Citron: Citrus medica Linn". Purdue University.

- ^ Frederick J. Simoons (1990). Food in China: a cultural and historical inquiry. CRC Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780849388040.

- ^ "ethrog". University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2015-06-08. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ^ Marion Eugene Ensminger; Audrey H. Ensminger (1993). Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). CRC Press. p. 424. ISBN 9780849389818.

- ^ Francesco Calabrese (2003). "Origin and history". In Giovanni Dugo; Angelo Di Giacomo (eds.). Citrus: The Citrus Genus. CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780203216613.

- ^ Biology of Citrus[dead link]

- ^ H. Harold Hume (2007). Citrus Fruits and Their Culture. Read Books. p. 59. ISBN 9781406781564.

- ^ Emmanuel Bonavia (1888). The Cultivated Oranges and Lemons, Etc. of India and Ceylon. W. H. Allen. p. 255.

- ^ Britain), Royal Horticultural Society (Great (1894). "Scientific Committee, March 28, 1893: The Antiquity of the Citron in Egypt". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 16.

- ^ Ramón-Laca, L. (Winter 2003). "The Introduction of Cultivated Citrus to Europe via Northern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula". Economic Botany. 57 (4): 502–514. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2003)057[0502:tiocct]2.0.co;2. S2CID 33447866.

- ^ Historia plantarum 4.4.2–3 (exc. Athenaeus Deipnosophistae 3.83.d-f); cf. Vergil Georgics 2.126-135; Pliny Naturalis historia 12.15,16.

- ^ Historia plantarum 1.13.4.

- ^ "Chap. 31.—The Citron-Tree". Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. excerpting from John Bostock; H. T. Riley, eds. (1855). The Natural History. Pliny the Elder. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book XII. The Natural History of Trees, Chap. 7. (3.)—How the Citron Is Planted". Tufts University.

- ^ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book XXIII. The Remedies Derived from the Cultivated Trees., Chap. 56.—Citrons: Five Observations upon Them". Tufts University.

- ^ Ibn al-'Awwam, Yaḥyá (1864). Le livre de l'agriculture d'Ibn-al-Awam (kitab-al-felahah) (in French). Translated by J.-J. Clement-Mullet. Paris: A. Franck. pp. 292–297 (ch. 7 - Article 29). OCLC 780050566. (pp. 292–297 (Article XXIX)

- ^ Un curieux Cedrat marocain, Chapot 1950.

- ^ a b Ramadugu, Chandrika; Keremane, Manjunath L; Hu, Xulan; Karp, David; Frederici, Claire T; Kahn, Tracy; Roose, Mikeal L; Lee, Richard F. (2015). "Genetic analysis of citron (Citrus medica L.) using simple sequence repeats and single nucleotide polymorphisms". Scientia Horticulturae. 195: 124–137. Bibcode:2015ScHor.195..124R. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.09.004.

- ^ "Website Disabled". University of California, Riverside. Archived from the original on 2008-03-08.

- ^ Meena, Ajay Kumar; Kandale, Ajit; Rao, M. M.; Panda, P.; Reddy, Govind (2011). "A review on citron-pharmacognosy, phytochemistry and medicinal uses". The Journal of Pharmacy. 2 (1): 14–20.

- ^ "ponderosa". citrusvariety.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-06.

- ^ Parla, Katie (2009-05-10). "Cedrata, A Strange and Refreshing Beverage". Katie Parla. Retrieved 2025-08-20.

- ^ "Bijora Pickle". Jain World. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-08-23.

- ^ Dahan, Arik; Yarmolinsky, Ludmila; Nakonechny, Faina; Semenova, Olga; Khalfin, Boris; Ben-Shabat, Shimon (2025-06-09). "Etrog Citron (Citrus medica) as a Novel Source of Antimicrobial Agents: Overview of Its Bioactive Phytochemicals and Delivery Approaches". Pharmaceutics. 17 (6): 761. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics17060761. ISSN 1999-4923. PMC 12196015. PMID 40574073.

- ^ Frederick Hardy (1924). "The Extraction of Pectin from the Fruit Rind of the Lime (Citrus medica acida)". Biochemical Journal. 18 (2): 283–290. doi:10.1042/bj0180283. PMC 1259415. PMID 16743304.

- ^ See Etrog

- ^ "buddha". citrusvariety.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-06.

- ^ "बिमिरो पूजासँगै खाउँ पनि!". shikshakmasik.com (in Nepali). Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ Nasana (2016-10-29). "Decoding Bhai Tika symbols". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Inouye, S.; Takizawa, T.; Yamaguchi, H. (2001). "Antibacterial activity of essential oils and their major constituents against respiratory tract pathogens by gaseous contact". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 47 (5): 565–573. doi:10.1093/jac/47.5.565. PMID 11328766.

Further reading

[edit]- H. Harold Hume, Citrus Fruits and Their Culture

- Frederick J. Simoons, Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry

- Pinhas Spiegel-Roy, Eliezer E. Goldschmidt, Biology of Citrus

- Alphonse de Candolle, Origin of Cultivated Plants

External links

[edit]- USDA Plants Profile – Citrus medica Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Citron" Purdue University

- University of California- "Citrus Diversity"

- Buddha's Hand citron by David Karp (pomologist)

Citron

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and etymology

Scientific classification

The citron is classified in the genus Citrus under the binomial name Citrus medica L., within the family Rutaceae and subfamily Aurantioideae.[7][8] Citrus medica is recognized as one of the three primary ancestral species of the Citrus genus, along with the pomelo (Citrus maxima) and mandarin (Citrus reticulata), from which the majority of modern cultivated citrus fruits—such as sweet oranges (Citrus × sinensis) and lemons (Citrus × limon)—have derived through a combination of natural interspecific hybridization and human selection.[8] Genomic analyses of diverse Citrus accessions reveal that the divergence of these ancestral taxa, including C. medica, occurred approximately 8–12 million years ago in the eastern Himalayan foothills, a region identified as the likely center of origin for the genus based on phylogenetic and biogeographic evidence.[8] The species exhibits notable heterozygosity, a characteristic prevalent across Citrus due to ancient admixture events and subsequent clonal propagation, though C. medica shows relatively lower levels compared to many derived hybrids.[8][9] Accepted synonyms for Citrus medica include Citrus cedra Link, while the fingered citron variant is denoted as Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis (Hoola van Nooten) Swingle.[10]Etymology and nomenclature

The term "citron" originates from the Latin citrus, denoting the citron tree and serving as the basis for the botanical genus Citrus. This Latin word is believed to derive from the ancient Greek kitron (κιτρόν), referring to the fruit, or possibly from the Persian turunj, ultimately linked to Sanskrit roots associated with citrus trees.[11][12][13] Across cultures, the citron has borne various historical names reflecting its early spread along trade routes from Asia to the Mediterranean. In Hebrew, it is called etrog (אֶתְרוֹג), a term used since biblical times for the fruit in religious observances. The Sanskrit name bijapura (बीजपूर) translates to "seed-filled," highlighting the fruit's abundant seeds and its mention in ancient Indian texts. In Arabic, it is known as utrujj (أترج) or utrunj (أترنج), borrowed from the Persian bāzārang (باذرنگ), indicating its introduction via Persian commerce.[14][15][13] The nomenclature evolved significantly with the advent of modern botany; in 1753, Carl Linnaeus established the binomial Citrus medica in Species Plantarum, with medica alluding to the fruit's medicinal reputation originating from ancient Media (modern-day Iran). Common names in European languages often draw from perceived resemblances, such as the French cédrat, derived from cèdre (cedar) due to the fruit's aromatic similarity to cedar wood. In East Asian languages, the names tie to cultural symbolism and trade dissemination: Chinese fó shǒu (佛手, "Buddha's hand") evokes the finger-like form of certain varieties, introduced through Buddhist trade networks, while the Japanese term bushukan (仏手柑) similarly reflects this shape and continental influences.[16][17][18][19]Botanical description

Tree morphology

The citron tree (Citrus medica) is a small evergreen shrub or tree that typically attains a height of 2 to 4 meters, characterized by a slow growth rate, an open and straggly habit, and irregular branches bearing stout, sharp spines up to 4 cm long.[20][2][21] Young shoots are often purplish, pubescent, and emit a strong aromatic scent when crushed, contributing to the tree's distinctive citrus fragrance.[22][18] The leaves are simple, alternate, and evergreen, appearing large and leathery with an ovate to elliptic shape, glossy dark green coloration, and lengths of 10 to 15 cm.[23][21] They feature serrate or undulate margins, prominent venation that creates a slightly wrinkled or rumpled surface, and short articulate petioles with broad wings, which are a hallmark of citron foliage.[18][22] The leaves are also faintly lemon-scented when bruised.[20] The bark on mature stems is grayish and rough, while younger stems remain smoother and more flexible.[2] The root system consists of shallow, fibrous roots that spread widely near the surface, facilitating adaptation to well-drained soils in subtropical and Mediterranean environments.[24]Fruit and flower characteristics

The flowers of the citron (Citrus medica) are highly fragrant and typically measure 3 to 5 cm in diameter, featuring five white petals that may be tinged with pink, especially in the buds.[25] They are hermaphroditic and self-fertile, allowing for effective pollination without external agents, though bees and other insects are attracted to their scent.[1] These blooms emerge in small axillary clusters or racemes throughout the year in suitable climates, with peak production in spring and fall.[26] The fruit is notably large, ranging from 10 to 30 cm in length, and adopts an ovoid or oblong shape reminiscent of an oversized lemon.[2] Its rind is thick—often up to several centimeters—and bumpy or rough-textured, turning from green to bright yellow upon ripening, while containing numerous oil glands that contribute to its intense aromatic profile.[20] The interior features minimal pulp that is mildly acidic, with flesh varying from dry and spongy in some forms to slightly juicier in others, alongside numerous white seeds that are typically monoembryonic.[27] Citron fruits require 8 to 12 months to mature from flowering, ripening primarily in late fall to winter depending on the cultivar and growing conditions.[28] A distinctive trait is their ability to remain on the tree for extended periods—sometimes over a year—without significant deterioration, maintaining quality due to the protective thick rind.[20]Varieties and hybrids

Pure citron varieties

Pure citron varieties encompass distinct cultivars of Citrus medica that have been selected and maintained without hybridization, preserving their ancestral traits such as thick rinds and minimal pulp. These varieties differ primarily in fruit shape, rind texture, and regional adaptations, reflecting centuries of cultivation in the Mediterranean and Asia. Notable examples include the etrog, diamante, and fingered forms, each valued for unique morphological features and cultural roles.[17] The etrog, a traditional variety central to Jewish religious practices, produces oblong fruits measuring 10-15 cm in length with a thick, bumpy, and ridged rind that is glossy and dotted with prominent oil glands. This rind emits a strong floral aroma combining lemon, violet, and pine-like citrus notes, while the interior features minimal acidic pulp and large vesicles. Primarily grown in Israel and Morocco, the etrog is selected for its unblemished, tapered form and the intact pitam (dried stigma), ensuring ritual purity during Sukkot observances.[29][30][17] The diamante citron, originating from Calabria in southern Italy, yields large, pear-shaped or ellipsoid fruits with square shoulders, thick white albedo, and a smooth to faintly ribbed yellow rind that is highly aromatic. Fruits typically weigh 0.5-1 kg, with fleshy, lemon-like acidic pulp enclosed in strong membranes, and the rind's intense scent makes it ideal for candying and culinary uses. This variety thrives in the Tyrrhenian coastal "Riviera dei Cedri," where it has been cultivated for centuries, distinguishing it from rougher Mediterranean types by its refined, glossy texture.[31][17][32] The Corsican or fingered citron (Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis), known as Buddha's hand, features elongated fruits 15-30 cm long that split into 5-20 finger-like segments resembling a hand, with no central pulp or seeds in standard strains. Its bright yellow rind is smooth yet corrugated, exuding a potent fragrance of violet, osmanthus, and citrus due to compounds like beta-ionone, and the solid albedo is edible when candied. Of Chinese origin and widely grown in East Asia, this variety was introduced to California in the 1970s, prized for ornamental and aromatic qualities rather than juice yield.[18][33][17] Other pure types include the Eretz Yisrael etrog, a knobby Israeli cultivar with cone-shaped fruits exhibiting a deeply corrugated, rough rind that contrasts with smoother etrogs, grown mainly in regions like Nablus and Jerusalem for its robust texture and traditional symbolism. The liscio, a smooth Italian variant akin to the diamante but with an even more uniform, unribbed rind, produces medium-large oval fruits with bright green lanceolate leaves on thorny trees, emphasizing its glossy, aromatic peel in Calabrian cultivation. These varieties highlight C. medica's diversity in rind profiles—from bumpy and aromatic to smooth and fleshy—adapted to specific locales without crossbreeding.[17]Hybrids and derivatives

The lemon (Citrus × limon) is a well-known hybrid derived from the citron (Citrus medica) and the bitter orange (Citrus aurantium), with the bitter orange acting as the maternal parent based on cytoplasmic inheritance patterns.[8] This cross imparts the lemon's characteristic thick, aromatic rind from the citron and intense acidity influenced by both progenitors.[34] Genetic analyses confirm this parentage through nuclear markers, highlighting the citron's paternal role in shaping the lemon's morphology and flavor profile.[8] The lime (Citrus × aurantifolia), exemplified by the Mexican lime, arises from a hybridization between the citron and a papeda relative such as Citrus micrantha, where the papeda serves as the maternal parent as evidenced by chloroplast DNA haplotypes.[34] These hybrids exhibit compact fruit size and exceptionally high juice content, traits that distinguish them from pure citron varieties while reflecting the papeda's influence on vigor and the citron's contribution to aroma.[8] Among other derivatives, the limetta or sweet lemon (Citrus limetta) represents another citron-bitter orange hybrid, sharing a similar parentage with the standard lemon but yielding mildly sweet, low-acid juice suitable for fresh consumption.[34] Molecular markers, including chloroplast DNA sequencing, provide genetic evidence of the citron's foundational role in citrus evolution, demonstrating its predominant role as the paternal parent in key hybrids like lemons and limes.[34] These analyses underscore the citron's pervasive influence across Citrus taxonomy, with nuclear and organelle data aligning to trace interspecies crosses.[8]History and distribution

Ancient origins

The citron (Citrus medica), one of the ancestral citrus species, is native to the Himalayan foothills in Northeast India and adjacent regions of Southeast Asia, where wild forms of the species and related progenitors persist.[8] Genomic analyses indicate that domestication likely occurred around 3000–4000 BCE in this area, involving selection for larger fruits and self-fertile traits through human cultivation, marking the beginning of its role as a prestige crop.[8] This early domestication is supported by the species' low genetic diversity, suggestive of a bottleneck event during initial human propagation.[35] Possible but disputed carbonized seeds, potentially of citron, have been reported from Mesopotamian sites like Nippur in southern Iraq, dating to approximately 4000–3500 BCE, though their identification remains tentative.[36] Further robust finds include fossilized pollen grains from a Persian royal garden at Ramat Rahel near Jerusalem, indicating cultivation by the 5th–4th centuries BCE, while artistic depictions on Achaemenid Persian reliefs from the same period portray the fruit as a symbol of luxury.[37] These remains highlight the citron's integration into elite horticulture, likely transported as seeds or grafts due to its thick rind aiding preservation. Early written records further document the citron's significance. The Greek botanist Theophrastus, in his Enquiry into Plants (c. 310 BCE), described the "Persian apple" (mēle Persikón) as a thorny tree bearing aromatic fruits used medicinally against poisons and digestive ailments, noting its introduction from Media (modern Iran).[38] Similarly, Pliny the Elder, in Natural History (c. 77 CE), detailed the citron's import to Rome from Persia and Media, emphasizing its value as an exotic remedy preserved in clay pots for trade, underscoring its status as a high-end commodity.[39] The citron's initial spread occurred via ancient trade routes, such as the Royal Road and incense trails, reaching Egypt by the late first millennium BCE—evidenced by textual references in Ptolemaic records—and Greece around 300 BCE following Persian influences and Alexander the Great's campaigns.[40] This diffusion positioned the citron as a cultural emblem in the Mediterranean, tied to ancient names like the "Median apple," reflecting its Persian provenance.[41]Historical spread and modern cultivation

The citron (Citrus medica), one of the ancestral citrus species, originated in the central Himalayan foothills, where it was domesticated before migrating westward as the first citrus crop, facilitated by its thick albedo and extended shelf life.[37] Pollen evidence indicates its gradual spread from Southeast Asia through Persia to the Mediterranean Basin, with the earliest archaeobotanical remains—citron pollen and seeds—dating to the 5th century BCE in a Persian royal garden near Jerusalem.[37] By the 4th century BCE, Greek botanist Theophrastus documented its cultivation in Media (modern Iran), describing it as the "Median fruit" and noting its use in perfumery and medicine.[37] Jewish communities adopted the citron for religious rituals, such as the etrog in Sukkot, by the 1st century CE, playing a key role in its further dissemination across the Mediterranean during the diaspora starting in the 2nd century BCE.[42] Following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, citron cultivation expanded into southern Italy through Jewish settlers, where it became integrated into local agriculture alongside other citrus.[42] By the late 16th century, the citron accompanied the rising popularity of orange cultivation in Europe, spreading to regions like France and Spain as ornamental and medicinal plants in formal gardens.[43] Its introduction to the Americas occurred with Spanish and Portuguese explorers in the 16th century, though it remained niche compared to more versatile citrus hybrids.[44] Throughout these expansions, the citron's cultural significance—particularly in Jewish Sukkot rituals as the etrog—ensured its persistence in religious and ceremonial contexts, even as commercial interest waned.[42] In modern times, citron cultivation is concentrated in subtropical and Mediterranean climates, with primary production in the Mediterranean region, particularly Italy's Calabria along the "Riviera dei Cedri," where about 79 hectares yield approximately 1,160 metric tons annually (as of 2015), centered in Santa Maria del Cedro.[42] Significant production also occurs in Israel for religious etrog use. Smaller-scale cultivation occurs in Corsica (France) and Crete (Greece), often for local candied peel production and religious use.[42] In Asia, it thrives in warmer areas of China, including Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, where varieties like Buddha's hand (C. medica var. sarcodactylis) are grown for medicinal, ornamental, and culinary purposes, with Sichuan emerging as China's largest hub for fingered citron.[45][46] Limited cultivation also persists in northeastern India, Myanmar, and parts of Southeast Asia, though often as an ornamental or wild relative rather than a major crop.[47] Globally, production remains modest due to the tree's sensitivity to cold winds and intense heat, favoring well-drained, loamy soils in temperate zones with optimal temperatures of 15–27°C.[48]Cultivation and production

Growing conditions and propagation

Citron trees (Citrus medica) require subtropical climates with minimal frost risk, as they are highly sensitive to cold temperatures below 5°C (41°F), which can cause wilting or tree death. They thrive in full sun, receiving at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight daily, and benefit from moderate humidity and consistent moisture without waterlogging. Well-drained soils rich in organic matter are essential, with an optimal pH range of 6.0–7.5 to support nutrient uptake and prevent root issues.[33][48][2] Propagation of citron can occur through seeds, which produce true-to-type plants but result in slow growth taking 3–5 years to fruit; semi-hardwood cuttings treated with rooting hormones like 500–1000 ppm indole-3-butyric acid (IBA); or grafting onto disease-resistant rootstocks such as trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata) to enhance vigor and adaptability. For ritual varieties like etrog, seeds or cuttings from certified pure strains are preferred to maintain varietal purity, avoiding grafting. The best propagation timing is spring or early summer in warm conditions.[33][5][49] Ongoing care involves annual pruning in late winter or early spring to shape the canopy, remove dead wood, and promote airflow, using citrus-specific fertilizers with balanced NPK ratios applied 3–4 times per year during the growing season. Watering should keep soil evenly moist, particularly for young trees, while established ones tolerate short dry periods. Fruits are harvested when the rind turns yellow, typically November to January in subtropical regions, though some varieties produce year-round.[33][28] Citron cultivation faces challenges including relatively low yields of 40–100 kg per mature tree and a tendency toward biennial bearing, where heavy cropping alternates with light or no production years, requiring management techniques like controlled pruning to mitigate.[2][50]Pests, diseases, and management

Citron trees (Citrus medica), like other citrus species, are susceptible to several insect pests that can damage foliage, twigs, and fruit. Aphids, such as the black citrus aphid (Toxoptera aurantii), feed on new growth, causing leaf curling and honeydew production that promotes sooty mold. Scale insects, including red scale (Aonidiella aurantii) and California red scale, attach to stems and leaves, extracting sap and weakening the plant while secreting honeydew.[51] The citrus leafminer (Phyllocnistis citrella) mines serpentine trails in young leaves, distorting growth and providing entry points for pathogens. Additionally, the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) targets ripening fruit, with larvae burrowing into the pulp and causing premature drop or internal decay, making it one of the most destructive pests for citron production in Mediterranean regions.[52] Key diseases affecting citron include bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens that threaten tree vigor and yield. Citrus greening, or Huanglongbing (HLB), caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, is vectored primarily by the Asian citrus psyllid (Diaphorina citri) and leads to mottled leaves, stunted fruit, and eventual tree decline; it has devastated citrus groves worldwide, including potential impacts on citron.[53] Phytophthora root rot, induced by soilborne oomycetes like Phytophthora citrophthora and P. nicotianae, thrives in poorly drained conditions and causes root decay, girdling, and canopy wilt. Citrus tristeza virus (CTV), transmitted by aphids, induces stem pitting and decline, particularly when citron is used as rootstock for other citrus, though tolerant varieties exist. Management of these threats relies on integrated pest management (IPM) strategies that combine cultural, biological, and chemical controls to minimize environmental impact. Biological controls include releasing natural enemies such as lady beetles for aphids and parasitic wasps (Aphytis melinus) for scales, alongside conservation of predatory mites against leafminers.[54] For fruit flies, trapping with protein baits and sterile insect techniques are effective non-chemical options.[55] Disease control involves using copper-based fungicides, such as copper hydroxide, applied preventively to suppress Phytophthora and bacterial infections, though resistance management is essential.[54] Quarantine protocols ensure propagation from HLB-free stock, while grafting onto resistant rootstocks like trifoliate orange (Poncirus trifoliata) mitigates tristeza and root rot risks.[53] Regular scouting and soil drainage improvements further support IPM efficacy.[54] As of 2025, climate change is exacerbating fungal pathogen pressures on citron in Mediterranean cultivation areas, with warmer temperatures and erratic rainfall favoring emerging threats like Phytophthora inundata root rot and increased incidence of Alternaria brown spot, necessitating adaptive IPM adjustments such as enhanced monitoring and resilient cultivars.[56][57]Global production and economic importance

Citron (Citrus medica) is a niche crop within the global citrus industry, with worldwide production primarily geared toward specialized markets rather than mass consumption. Estimates indicate that annual global output for commercial purposes, such as candied peel production, totals approximately 7,000 metric tons, cultivated on around 1,000 hectares, predominantly in Mediterranean regions.[58] In Israel, etrog varieties contribute an additional roughly 400 metric tons annually, derived from about 1 million fruits grown on 150 hectares dedicated to religious and ceremonial use.[59] Leading producers include Italy, where the Diamante variety dominates cultivation in Calabria, alongside Israel and smaller contributions from China and other Mediterranean countries like Greece and Turkey.[60] Economically, citron holds value as a high-margin specialty fruit, with the global market estimated in the tens of millions of USD, driven by premium pricing for etrogim ($20–$100 per fruit depending on quality and origin) and candied Diamante peels used in confectionery.[61] In Calabria, Italy, citron farming provides essential income for local families, supporting small-scale operations that integrate traditional methods with emerging sustainable technologies like agrivoltaics to combat climate challenges.[62] The crop's economic role is amplified by its non-perishable rind, which commands high prices in processed forms for marmalades, liqueurs, and essential oils. Trade in citron is concentrated in niche channels, with Israel exporting around 300,000 etrogim annually—primarily to the United States for Sukkot celebrations—generating significant seasonal revenue through kosher-certified supply chains.[14] Italian Diamante exports target European and North American markets for industrial applications, while overall global trade remains modest compared to major citrus like oranges, emphasizing quality over volume. Sustainability efforts focus on smallholder farming, which prevails in production areas; innovations such as solar-integrated orchards in Italy enhance resilience to drought and heat, fostering potential for expanded cultivation amid rising demand for natural, bioactive products.[60]Nutritional composition

Macronutrients and micronutrients

The citron fruit (Citrus medica) exhibits a low-calorie profile, providing approximately 25–73 kcal per 100 g of fresh weight, making it a nutrient-dense option with minimal energy contribution.[63] Macronutrients are present in modest amounts, with carbohydrates ranging from 9–17 g per 100 g fresh weight (primarily dietary fiber rather than sugars), trace protein at 0.8–3 g, and negligible fat at 0.4–0.6 g; the pulp, in contrast, consists largely of water (82–86 g per 100 g), contributing to the fruit's overall low density of macronutrients.[63] Sugars such as glucose (0.9–2.3 g), fructose (1.6–3.0 g), and sucrose (0.3–1.0 g) per 100 g are notably lower than in sweeter citrus varieties like oranges.[63] Among micronutrients, vitamin C (ascorbic acid) stands out, with concentrations of 50–100 mg per 100 g across the fruit, highest in the juice (around 54 mg per 100 g), with lower concentrations in the peel (e.g., 3–8 mg per 100 g in exocarp and mesocarp).[63] Vitamin B vitamins are also present, particularly in the peel, with B6 ranging from 0.75–10.12 mg per 100 g, B1 (thiamine) 1.32–3.65 mg, and B2 (riboflavin) 0.37–1.16 mg.[63] Key minerals include potassium (126–263 mg per 100 g, averaging about 150 mg) and calcium (107–196 mg per 100 g), both more abundant in the peel than the pulp; other trace elements like iron (0.8–2.9 mg) and magnesium (6–16 mg) are also present.[63] Flavonoids such as naringin contribute to the micronutrient profile, particularly in the rind.[64] Scientific analyses, akin to USDA compositional data for related citrus, emphasize the peel as the primary edible portion due to its higher nutrient density, while the bitter, fibrous pulp is less consumed raw.[63] In comparison to other citrus fruits like lemons or oranges, citron features elevated dietary fiber (up to 11 g per 100 g in dried equivalents, higher proportionally in fresh peel) and reduced sugar content, enhancing its suitability for low-glycemic applications.[65] Nutrient levels vary between rind and pulp—the former richer in vitamins and minerals, the latter in moisture—and can fluctuate seasonally based on maturity and environmental factors like sunlight exposure.[63]| Nutrient Category | Key Components (per 100 g fresh weight, approximate ranges) | Primary Location |

|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | Calories: 25–73 kcal Carbohydrates: 9–17 g (mostly fiber) Protein: 0.8–3 g Fat: 0.4–0.6 g Water: 82–86 g | Pulp (high water); peel (fiber) |

| Micronutrients | Vitamin C: 50–100 mg Potassium: 126–263 mg Calcium: 107–196 mg Naringin (flavonoid): Present (quantitative data variable) | Rind (richest in vitamin C, minerals) |