Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

- Apex

- Midvein (Primary vein)

- Secondary vein

- Lamina

- Leaf margin

- Petiole

- Bud

- Stem

Bottom: skunk cabbage, Symplocarpus foetidus (simple leaf)

- Apex

- Primary vein

- Secondary vein

- Lamina

- Leaf margin

- Rachis

A leaf (pl.: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant,[1] usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage",[2][3] while the leaves, stem, flower, and fruit collectively form the shoot system.[4] In most leaves, the primary photosynthetic tissue is the palisade mesophyll and is located on the upper side of the blade or lamina of the leaf,[1] but in some species, including the mature foliage of Eucalyptus,[5] palisade mesophyll is present on both sides and the leaves are said to be isobilateral. The leaf is an integral part of the stem system, and most leaves are flattened and have distinct upper (adaxial) and lower (abaxial) surfaces that differ in color, hairiness, the number of stomata (pores that intake and output gases), the amount and structure of epicuticular wax, and other features. Leaves are mostly green in color due to the presence of a compound called chlorophyll which is essential for photosynthesis as it absorbs light energy from the Sun. A leaf with lighter-colored or white patches or edges is called a variegated leaf.

Leaves vary in shape, size, texture and color, depending on the species The broad, flat leaves with complex venation of flowering plants are known as megaphylls and the species that bear them (the majority) as broad-leaved or megaphyllous plants, which also include acrogymnosperms and ferns. In the lycopods, with different evolutionary origins, the leaves are simple (with only a single vein) and are known as microphylls.[6] Some leaves, such as bulb scales, are not above ground. In many aquatic species, the leaves are submerged in water. Succulent plants often have thick juicy leaves, but some leaves are without major photosynthetic function and may be dead at maturity, as in some cataphylls and spines. Furthermore, several kinds of leaf-like structures found in vascular plants are not totally homologous with them. Examples include flattened plant stems called phylloclades and cladodes, and flattened leaf stems called phyllodes which differ from leaves both in their structure and origin.[3][7] Some structures of non-vascular plants look and function much like leaves. Examples include the phyllids of mosses and liverworts.

General characteristics

[edit]Leaves are the most important organs of most vascular plants.[8] Green plants are autotrophic, meaning that they do not obtain food from other living things but instead create their own food by photosynthesis. They capture the energy in sunlight and use it to make simple sugars, such as glucose and sucrose, from carbon dioxide (CO2) and water. The sugars are then stored as starch, further processed by chemical synthesis into more complex organic molecules such as proteins or cellulose, the basic structural material in plant cell walls, or metabolized by cellular respiration to provide chemical energy to run cellular processes. The leaves draw water from the ground in the transpiration stream through a vascular conducting system known as xylem and obtain carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by diffusion through openings called stomata in the outer covering layer of the leaf (epidermis), while leaves are orientated to maximize their exposure to sunlight. Once sugar has been synthesized, it needs to be transported to areas of active growth such as the shoots and roots. Vascular plants transport sucrose in a special tissue called the phloem. The phloem and xylem are parallel to each other, but the transport of materials is usually in opposite directions. Within the leaf these vascular systems branch (ramify) to form veins which supply as much of the leaf as possible, ensuring that cells carrying out photosynthesis are close to the transportation system.[9]

Typically leaves are broad, flat and thin (dorsiventrally flattened), thereby maximizing the surface area directly exposed to light and enabling the light to penetrate the tissues and reach the chloroplasts, thus promoting photosynthesis. They are arranged on the plant so as to expose their surfaces to light as efficiently as possible without shading each other, but there are many exceptions and complications. For instance, plants adapted to windy conditions may have pendent leaves, such as in many willows and eucalypts. The flat, or laminar, shape also maximizes thermal contact with the surrounding air, promoting cooling. Functionally, in addition to carrying out photosynthesis, the leaf is the principal site of transpiration, providing the energy required to draw the transpiration stream up from the roots, and guttation.

Many conifers have thin needle-like or scale-like leaves that can be advantageous in cold climates with frequent snow and frost.[10] These are interpreted as reduced from megaphyllous leaves of their Devonian ancestors.[6] Some leaf forms are adapted to modulate the amount of light they absorb to avoid or mitigate excessive heat, ultraviolet damage, or desiccation, or to sacrifice light-absorption efficiency in favor of protection from herbivory. For xerophytes the major constraint is not light flux or intensity, but drought.[11] Some window plants such as Fenestraria species and some Haworthia species such as Haworthia tesselata and Haworthia truncata are examples of xerophytes.[12]

Leaves function to store chemical energy and water (especially in succulents) and may become specialized organs serving other functions, such as tendrils of peas and other legumes, the protective spines of cacti, and the insect traps in carnivorous plants such as Nepenthes and Sarracenia.[13] Leaves are the fundamental structural units from which cones are constructed in gymnosperms (each cone scale is a modified megaphyll leaf known as a sporophyll)[6]: 408 and from which flowers are constructed in flowering plants.[6]: 445

The internal organization of most kinds of leaves has evolved to maximize exposure of the photosynthetic organelles (chloroplasts) to light and to increase the absorption of CO2 while at the same time controlling water loss. Their surfaces are waterproofed by the plant cuticle, and gas exchange between the mesophyll cells and the atmosphere is controlled by minute (length and width measured in tens of μm) stomata which open or close to regulate the rate exchange of CO2, oxygen (O2), and water vapor into and out of the internal intercellular space system. Stomatal opening is controlled by the turgor pressure in a pair of guard cells that surround the stomatal aperture. In any square centimeter of a plant leaf, there may be from 1,000 to 100,000 stomata.[14]

The shape and structure of leaves vary considerably from species to species of plant, depending largely on their adaptation to climate and available light, but also to other factors such as grazing animals, available nutrients, and ecological competition from other plants. Considerable changes in leaf type occur within species, too, for example as a plant matures (Eucalyptus species commonly have isobilateral, pendent leaves when mature and dominating their neighbors; however, such trees tend to have erect or horizontal dorsiventral leaves as seedlings, when their growth is limited by the available light.)[15] Other factors include the need to balance water loss at high temperature and low humidity against the need to absorb CO2. In most plants, leaves also are the primary organs responsible for transpiration and guttation (beads of fluid forming at leaf margins).

Leaves can also store food and water and are modified accordingly to meet these functions, for example in the leaves of succulent plants and in bulb scales. The concentration of photosynthetic structures in leaves requires that they be richer in protein, minerals, and sugars than, say, woody stem tissues. Accordingly, leaves are prominent in the diet of many animals. Correspondingly, leaves represent heavy investment on the part of the plants bearing them, and their retention or disposition are the subject of elaborate strategies for dealing with pest pressures, seasonal conditions, and protective measures such as the growth of thorns and the production of phytoliths, lignins, tannins and poisons.

Deciduous plants in cold temperate regions typically shed their leaves in autumn, whereas in areas with a severe dry season, some plants may shed their leaves until the dry season ends. In either case, the shed leaves often contribute their retained nutrients to the soil where they fall. In contrast, many other non-seasonal plants, such as palms and conifers, retain their leaves for long periods; Welwitschia retains its two main leaves throughout a lifetime that may exceed a thousand years.

The leaf-like organs of bryophytes (e.g., mosses and liverworts), known as phyllids, differ greatly morphologically from the leaves of vascular plants. In most cases, they lack vascular tissue, are a single cell thick and have no cuticle, stomata, or internal system of intercellular spaces. (The phyllids of the moss family Polytrichaceae are notable exceptions.) The phyllids of bryophytes are only present on the gametophytes, while in contrast the leaves of vascular plants are only present on the sporophytes. These can further develop into either vegetative or reproductive structures.[13]

Simple, vascularized leaves (microphylls), such as those of the early Devonian lycopsid Baragwanathia, first evolved as enations, extensions of the stem. True leaves or euphylls of larger size and with more complex venation did not become widespread in other groups until the Devonian period, by which time the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere had dropped significantly. This occurred independently in several separate lineages of vascular plants, in progymnosperms like Archaeopteris, in Sphenopsida, ferns and later in the gymnosperms and angiosperms. Euphylls are also referred to as macrophylls or megaphylls (large leaves).[6]

Morphology

[edit]

A structurally complete leaf of an angiosperm consists of a petiole (leaf stalk, called a stipe in ferns), a lamina (leaf blade), stipules (small structures located to either side of the base of the petiole) and a sheath. Not every species produces leaves with all of these structural components. The lamina is the expanded, flat component of the leaf which contains the chloroplasts. The sheath is a structure at the base that fully or partially wraps around the stem, above the node where the leaf is attached. Leaf sheathes typically occur in Poaceae (grasses), Apiaceae (umbellifers), and many palms. Between the sheath and the lamina, there may be a pseudopetiole, a petiole like structure. Pseudopetioles occur in some monocotyledons including bananas, palms and bamboos.[17] Stipules may be conspicuous (e.g. beans and roses), soon falling or otherwise not obvious as in Moraceae or absent altogether as in the Magnoliaceae. A petiole may be absent (apetiolate), or the blade may not be laminar (flattened). The petiole mechanically links the leaf to the plant and provides the route for transfer of water and sugars to and from the leaf. The lamina is typically the location of the majority of photosynthesis. The upper (adaxial) angle between a leaf and a stem is known as the axil of the leaf. It is often the location of a bud. Structures located there are called "axillary".

External leaf characteristics, such as shape, margin, hairs, the petiole, and the presence of stipules and glands, are frequently important for identifying plants to family, genus or species levels, and botanists have developed a rich terminology for describing leaf characteristics. Leaves almost always have determinate growth. They grow to a specific pattern and shape and then stop. Other plant parts like stems or roots have non-determinate growth, and will usually continue to grow as long as they have the resources to do so.

The type of leaf is usually characteristic of a species (monomorphic), although some species produce more than one type of leaf (dimorphic or polymorphic). The longest leaves are those of the Raffia palm (Raphia regalis) which may be up to 25 m (82 ft) long and 3 m (9.8 ft) wide.[18] The terminology associated with the description of leaf morphology is presented, in illustrated form, at Wikibooks.

Where leaves are basal, and lie on the ground, they are referred to as prostrate.

Basic leaf types

[edit]

Perennial plants whose leaves are shed annually are said to have deciduous leaves, while leaves that remain through winter are evergreens. Leaves attached to stems by stalks (known as petioles) are called petiolate, and if attached directly to the stem with no petiole they are called sessile.[19]

- Ferns have fronds.

- Conifer leaves are typically needle- or awl-shaped or scale-like; they are usually evergreen but can sometimes be deciduous. Usually, they have a single vein.

- The standard form of flowering plants (angiosperm) includes stipules, a petiole, and a lamina.

- Lycophytes have microphylls.

- Sheath leaves are the type found in most grasses and many other monocots.

- Other specialized leaves include those of Nepenthes, a pitcher plant.

Dicot leaves have blades with pinnate venation (where major veins diverge from one large mid-vein and have smaller connecting networks between them). Less commonly, dicot leaf blades may have palmate venation (several large veins diverging from petiole to leaf edges). Finally, some exhibit parallel venation.[19] Monocot leaves in temperate climates usually have narrow blades and usually parallel venation converging at leaf tips or edges. Some also have pinnate venation.[19]

Arrangement on the stem

[edit]The arrangement of leaves on the stem is known as phyllotaxis.[20] A large variety of phyllotactic patterns occur in nature:

- Alternate

- One leaf, branch, or flower part attaches at each point or node on the stem, and leaves alternate direction—to a greater or lesser degree—along the stem.

- Basal

- Arising from the base of the plant.

- Cauline

- Attached to the aerial stem.

- Opposite

- Two leaves, branches, or flower parts attach at each point or node on the stem. Leaf attachments are paired at each node.

- Decussate

- An opposite arrangement in which each successive pair is rotated 90° from the previous.

- Whorled, or verticillate

- Three or more leaves, branches, or flower parts attach at each point or node on the stem. As with opposite leaves, successive whorls may or may not be decussate, rotated by half the angle between the leaves in the whorl (i.e., successive whorls of three rotated 60°, whorls of four rotated 45°, etc.). Opposite leaves may appear whorled near the tip of the stem. Pseudoverticillate describes an arrangement only appearing whorled, but not actually so.

- Rosulate

- Leaves form a rosette.

- Rows

- The term distichous literally means two rows. Leaves in this arrangement may be alternate or opposite in their attachment. The term 2-ranked is equivalent. The terms tristichous and tetrastichous are sometimes encountered. For example, the "leaves" (actually microphylls) of most species of Selaginella are tetrastichous but not decussate.

In the simplest mathematical models of phyllotaxis, the apex of the stem is represented as a circle. Each new node is formed at the apex, and it is rotated by a constant angle from the previous node. This angle is called the divergence angle. The number of leaves that grow from a node depends on the plant species. When a single leaf grows from each node, and when the stem is held straight, the leaves form a helix.

The divergence angle is often represented as a fraction of a full rotation around the stem. A rotation fraction of 1/2 (a divergence angle of 180°) produces an alternate arrangement, such as in Gasteria or the fan-aloe Kumara plicatilis. Rotation fractions of 1/3 (divergence angles of 120°) occur in beech and hazel. Oak and apricot rotate by 2/5, sunflowers, poplar, and pear by 3/8, and in willow and almond the fraction is 5/13.[21] These arrangements are periodic. The denominator of the rotation fraction indicates the number of leaves in one period, while the numerator indicates the number of complete turns or gyres made in one period. For example:

- 180° (or 1⁄2): two leaves in one circle (alternate leaves)

- 120° (or 1⁄3): three leaves in one circle

- 144° (or 2⁄5): five leaves in two gyres

- 135° (or 3⁄8): eight leaves in three gyres.

Most divergence angles are related to the sequence of Fibonacci numbers Fn. This sequence begins 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13; each term is the sum of the previous two. Rotation fractions are often quotients Fn / Fn + 2 of a Fibonacci number by the number two terms later in the sequence. This is the case for the fractions 1/2, 1/3, 2/5, 3/8, and 5/13. The ratio between successive Fibonacci numbers tends to the golden ratio φ = (1 + √5)/2. When a circle is divided into two arcs whose lengths are in the ratio 1:φ, the angle formed by the smaller arc is the golden angle, which is 1/φ2 × 360° ≈ 137.5°. Because of this, many divergence angles are approximately 137.5°. In plants where a pair of opposite leaves grows from each node, the leaves form a double helix. If the nodes do not rotate (a rotation fraction of zero and a divergence angle of 0°), the two helices become a pair of parallel lines, creating a distichous arrangement as in maple or olive trees. More common in a decussate pattern, in which each node rotates by 1/4 (90°) as in the herb basil. The leaves of tricussate plants such as Nerium oleander form a triple helix. The leaves of some plants do not form helices. In some plants, the divergence angle changes as the plant grows.[22] In orixate phyllotaxis, named after Orixa japonica, the divergence angle is not constant. Instead, it is periodic and follows the sequence 180°, 90°, 180°, 270°.[23]

Divisions of the blade

[edit]

Two basic forms of leaves can be described considering the way the blade (lamina) is divided. A simple leaf has an undivided blade. However, the leaf may be dissected to form lobes, but the gaps between lobes do not reach to the main vein. A compound leaf has a fully subdivided blade, each leaflet of the blade being separated along a main or secondary vein. The leaflets may have petiolules and stipels, the equivalents of the petioles and stipules of leaves. Because each leaflet can appear to be a simple leaf, it is important to recognize where the petiole occurs to identify a compound leaf. Compound leaves are a characteristic of some families of higher plants, such as the Fabaceae. The middle vein of a compound leaf or a frond, when it is present, is called a rachis.

- Palmately compound

- The leaflets all have a common point of attachment at the end of the petiole, radiating like fingers of a hand; for example, Cannabis (hemp) and Aesculus (buckeyes).

- Pinnately compound

- Leaflets are arranged either side of the main axis, or rachis.

- Odd pinnate

- With a terminal leaflet; for example, Fraxinus (ash).

- Even pinnate

- Lacking a terminal leaflet; for example, Swietenia (mahogany). A specific type of even pinnate is bifoliolate, where leaves only consist of two leaflets; for example, Hymenaea.

- Bipinnately compound

- Leaves are twice divided: the leaflets (technically "subleaflets") are arranged along a secondary axis that is one of several branching off the rachis. Each leaflet is called a pinnule. The group of pinnules on each secondary vein forms a pinna; for example, Albizia (silk tree).

- Trifoliate (or trifoliolate)

- A pinnate leaf with just three leaflets; for example, Trifolium (clover), Laburnum (laburnum), and some species of Toxicodendron (for instance, poison ivy).

- Pinnatifid

- Pinnately dissected to the central vein, but with the leaflets not entirely separate; for example, Polypodium, some Sorbus (whitebeams). In pinnately veined leaves the central vein is known as the midrib.

Characteristics of the petiole

[edit]

Leaves which have a petiole (leaf stalk) are said to be petiolate. Sessile (epetiolate) leaves have no petiole, and the blade attaches directly to the stem. Subpetiolate leaves are nearly petiolate or have an extremely short petiole and may appear to be sessile. In clasping or decurrent leaves, the blade partially surrounds the stem. When the leaf base completely surrounds the stem, the leaves are said to be perfoliate, such as in Eupatorium perfoliatum. In peltate leaves, the petiole attaches to the blade inside the blade margin. In some Acacia species, such as the koa tree (Acacia koa), the petioles are expanded or broadened and function like leaf blades; these are called phyllodes. There may or may not be normal pinnate leaves at the tip of the phyllode. A stipule, present on the leaves of many dicotyledons, is an appendage on each side at the base of the petiole, resembling a small leaf. Stipules may be lasting and not be shed (a stipulate leaf, such as in roses and beans), or be shed as the leaf expands, leaving a stipule scar on the twig (an exstipulate leaf). The situation, arrangement, and structure of the stipules is called the "stipulation".

- Free, lateral

- As in Hibiscus.

- Adnate

- Fused to the petiole base, as in Rosa.

- Ochreate

- Provided with ochrea, or sheath-formed stipules, as in Polygonaceae; e.g., rhubarb.

- Encircling the petiole base

- Interpetiolar

- Between the petioles of two opposite leaves, as in Rubiaceae.

- Intrapetiolar

- Between the petiole and the subtending stem, as in Malpighiaceae.

Veins

[edit]

Veins (sometimes referred to as nerves) constitute one of the most visible features of leaves. The veins in a leaf represent the vascular structure of the organ, extending into the leaf via the petiole and providing transportation of water and nutrients between leaf and stem, and play a crucial role in the maintenance of leaf water status and photosynthetic capacity. They also play a role in the mechanical support of the leaf.[24][25] Within the lamina of the leaf, while some vascular plants possess only a single vein, in most this vasculature generally divides (ramifies) according to a variety of patterns (venation) and form cylindrical bundles, usually lying in the median plane of the mesophyll, between the two layers of epidermis.[26] This pattern is often specific to taxa, and of which angiosperms possess two main types, parallel and reticulate (net like). In general, parallel venation is typical of monocots, while reticulate is more typical of eudicots and magnoliids ("dicots"), though there are many exceptions.[27][26][28]

The vein or veins entering the leaf from the petiole are called primary or first-order veins. The veins branching from these are secondary or second-order veins. These primary and secondary veins are considered major veins or lower order veins, though some authors include third order.[29] Each subsequent branching is sequentially numbered, and these are the higher order veins, each branching being associated with a narrower vein diameter.[30]

In parallel veined leaves, the primary veins run parallel and equidistant to each other for most of the length of the leaf and then converge or fuse (anastomose) towards the apex. Usually, many smaller minor veins interconnect these primary veins but may terminate with very fine vein endings in the mesophyll. Minor veins are more typical of angiosperms, which may have as many as four higher orders.[29]

In contrast, leaves with reticulate venation have a single (sometimes more) primary vein in the center of the leaf, referred to as the midrib or costa, which is continuous with the vasculature of the petiole. The secondary veins, also known as second order veins or lateral veins, branch off from the midrib and extend toward the leaf margins. These often terminate in a hydathode, a secretory organ, at the margin. In turn, smaller veins branch from the secondary veins, known as tertiary or third order (or higher order) veins, forming a dense reticulate pattern. The areas or islands of mesophyll lying between the higher order veins, are called areoles. Some of the smallest veins (veinlets) may have their endings in the areoles, a process known as areolation.[30] These minor veins act as the sites of exchange between the mesophyll and the plant's vascular system.[25] Thus, minor veins collect the products of photosynthesis (photosynthate) from the cells where it takes place, while major veins are responsible for its transport outside of the leaf. At the same time water is being transported in the opposite direction.[31][27][26]

The number of vein endings is variable, as is whether second order veins end at the margin, or link back to other veins.[28] There are many elaborate variations on the patterns that the leaf veins form, and these have functional implications. Of these, angiosperms have the greatest diversity.[29] Within these the major veins function as the support and distribution network for leaves and are correlated with leaf shape. For instance, the parallel venation found in most monocots correlates with their elongated leaf shape and wide leaf base, while reticulate venation is seen in simple entire leaves, while digitate leaves typically have venation in which three or more primary veins diverge radially from a single point.[32][25][30][33]

In evolutionary terms, early emerging taxa tend to have dichotomous branching with reticulate systems emerging later. Veins appeared in the Permian, prior to the appearance of angiosperms in the Triassic, during which vein hierarchy appeared enabling higher function, larger leaf size and adaption to a wider variety of climatic conditions.[29] Although it is the more complex pattern, branching veins appear to be plesiomorphic and in some form were present in ancient seed plants as long as 250 million years ago. A pseudo-reticulate venation that is actually a highly modified penniparallel one is an autapomorphy of some Melanthiaceae, which are monocots; e.g., Paris quadrifolia (true-lover's knot). In leaves with reticulate venation, veins form a scaffolding matrix imparting mechanical rigidity to leaves.[34]

Morphology changes within a single plant

[edit]- Homoblasty

- Characteristic in which a plant has small changes in leaf size, shape, and growth habit between juvenile and adult stages, in contrast to;

- Heteroblasty

- Characteristic in which a plant has marked changes in leaf size, shape, and growth habit between juvenile and adult stages.

Anatomy

[edit]Medium-scale features

[edit]Leaves are normally extensively vascularized and typically have networks of vascular bundles containing xylem, which supplies water for photosynthesis, and phloem, which transports the sugars produced by photosynthesis. Many leaves are covered in trichomes (small hairs) which have diverse structures and functions.

Small-scale features

[edit]The major tissue systems present are

- The epidermis, which covers the upper and lower surfaces

- The mesophyll tissue, which consists of photosynthetic cells rich in chloroplasts. (also called chlorenchyma)

- The arrangement of veins (the vascular tissue)

These three tissue systems typically form a regular organization at the cellular scale. Specialized cells that differ markedly from surrounding cells, and which often synthesize specialized products such as crystals, are termed idioblasts.[35]

Major leaf tissues

[edit]Epidermis

[edit]

The epidermis is the outer layer of cells covering the leaf. It is covered with a waxy cuticle which is impermeable to liquid water and water vapor and forms the boundary separating the plant's inner cells from the external world. The cuticle is in some cases thinner on the lower epidermis than on the upper epidermis, and is generally thicker on leaves from dry climates as compared with those from wet climates.[36] The epidermis serves several functions: protection against water loss by way of transpiration, regulation of gas exchange and secretion of metabolic compounds. Most leaves show dorsoventral anatomy: The upper (adaxial) and lower (abaxial) surfaces have somewhat different construction and may serve different functions.

The epidermis tissue includes several differentiated cell types; epidermal cells, epidermal hair cells (trichomes), cells in the stomatal complex; guard cells and subsidiary cells. The epidermal cells are the most numerous, largest, and least specialized and form the majority of the epidermis. They are typically more elongated in the leaves of monocots than in those of dicots.

Chloroplasts are generally absent in epidermal cells, the exception being the guard cells of the stomata. The stomatal pores perforate the epidermis and are surrounded on each side by chloroplast-containing guard cells, and two to four subsidiary cells that lack chloroplasts, forming a specialized cell group known as the stomatal complex. The opening and closing of the stomatal aperture is controlled by the stomatal complex and regulates the exchange of gases and water vapor between the outside air and the interior of the leaf. Stomata therefore play the important role in allowing photosynthesis without letting the leaf dry out. In a typical leaf, the stomata are more numerous over the abaxial (lower) epidermis than the adaxial (upper) epidermis and are more numerous in plants from cooler climates.

Mesophyll

[edit]Most of the interior of the leaf between the upper and lower layers of epidermis is a parenchyma (ground tissue) or chlorenchyma tissue called the mesophyll (Greek for "middle leaf"). This assimilation tissue is the primary location of photosynthesis in the plant. The products of photosynthesis are called "assimilates".

In ferns and most flowering plants, the mesophyll is divided into two layers:

- An upper palisade layer of vertically elongated cells, one to two cells thick, directly beneath the adaxial epidermis, with intercellular air spaces between them. Its cells contain many more chloroplasts than the spongy layer. Cylindrical cells, with the chloroplasts close to the walls of the cell, can take optimal advantage of light. The slight separation of the cells provides maximum absorption of carbon dioxide. Sun leaves have a multi-layered palisade layer, while shade leaves or older leaves closer to the soil are single-layered.

- Beneath the palisade layer is the spongy layer. The cells of the spongy layer are more branched and not so tightly packed, so that there are large intercellular air spaces between them. The pores or stomata of the epidermis open into substomatal chambers, which are connected to the intercellular air spaces between the spongy and palisade mesophyll cell, so that oxygen, carbon dioxide and water vapor can diffuse into and out of the leaf and access the mesophyll cells during respiration, photosynthesis and transpiration.

Leaves are normally green, due to chlorophyll in chloroplasts in the mesophyll cells. Some plants have leaves of different colors due to the presence of accessory pigments such as carotenoids in their mesophyll cells.

Vascular tissue

[edit]

The veins are the vascular tissue of the leaf and are located in the spongy layer of the mesophyll. The pattern of the veins is called venation. In angiosperms the venation is typically parallel in monocotyledons and forms an interconnecting network in broad-leaved plants. They were once thought to be typical examples of pattern formation through ramification, but they may instead exemplify a pattern formed in a stress tensor field.[37][38][39]

A vein is made up of a vascular bundle. At the core of each bundle are clusters of two distinct types of conducting cells:

- Xylem

- Cells that bring water and minerals from the roots into the leaf.

- Phloem

- Cells that usually move sap, with dissolved sucrose (glucose to sucrose) produced by photosynthesis in the leaf, out of the leaf.

The xylem typically lies on the adaxial side of the vascular bundle and the phloem typically lies on the abaxial side. Both are embedded in a dense parenchyma tissue, called the sheath, which usually includes some structural collenchyma tissue.

Leaf development

[edit]According to Agnes Arber's partial-shoot theory of the leaf, leaves are partial shoots,[40] being derived from leaf primordia of the shoot apex. Early in development they are dorsiventrally flattened with both dorsal and ventral surfaces.[13] Compound leaves are closer to shoots than simple leaves. Developmental studies have shown that compound leaves, like shoots, may branch in three dimensions.[41][42] On the basis of molecular genetics, Eckardt and Baum (2010) concluded that "it is now generally accepted that compound leaves express both leaf and shoot properties."[43] Many dicotyledonous leaves show endogenously driven daily rhythmicity in growth.[44][45][46]

Ecology

[edit]Biomechanics

[edit]Plants respond and adapt to environmental factors, such as light and mechanical stress from wind. Leaves need to support their own mass and align themselves in such a way as to optimize their exposure to the sun, generally more or less horizontally. However, horizontal alignment maximizes exposure to bending forces and failure from stresses such as wind, snow, hail, falling debris, animals, and abrasion from surrounding foliage and plant structures. Overall leaves are relatively flimsy with regard to other plant structures such as stems, branches and roots.[47]

Both leaf blade and petiole structure influence the leaf's response to forces such as wind, allowing a degree of repositioning to minimize drag and damage, as opposed to resistance. Leaf movement like this may also increase turbulence of the air close to the surface of the leaf, which thins the boundary layer of air immediately adjacent to the surface, increasing the capacity for gas and heat exchange, as well as photosynthesis. Strong wind forces may result in diminished leaf number and surface area, which while reducing drag, involves a trade off of also reducing photosynthesis. Thus, leaf design may involve compromise between carbon gain, thermoregulation and water loss on the one hand, and the cost of sustaining both static and dynamic loads. In vascular plants, perpendicular forces are spread over a larger area and are relatively flexible in both bending and torsion, enabling elastic deforming without damage.[47]

Many leaves rely on hydrostatic support arranged around a skeleton of vascular tissue for their strength, which depends on maintaining leaf water status. Both the mechanics and architecture of the leaf reflect the need for transportation and support. Read and Stokes (2006) consider two basic models, the "hydrostatic" and "I-beam leaf" form (see Fig 1).[47] Hydrostatic leaves such as in Prostanthera lasianthos are large and thin, and may involve the need for multiple leaves rather single large leaves because of the amount of veins needed to support the periphery of large leaves. But large leaf size favors efficiency in photosynthesis and water conservation, involving further trade offs. On the other hand, I-beam leaves such as Banksia marginata involve specialized structures to stiffen them. These I-beams are formed from bundle sheath extensions of sclerenchyma meeting stiffened sub-epidermal layers. This shifts the balance from reliance on hydrostatic pressure to structural support, an obvious advantage where water is relatively scarce. [47] Long narrow leaves bend more easily than ovate leaf blades of the same area. Monocots typically have such linear leaves that maximize surface area while minimizing self-shading. In these a high proportion of longitudinal main veins provide additional support.[47]

Interactions with other organisms

[edit]

Although not as nutritious as other organs such as fruit, leaves provide a food source for many organisms. The leaf is a vital source of energy production for the plant, and plants have evolved protection against animals that consume leaves, such as tannins, chemicals which hinder the digestion of proteins and have an unpleasant taste. Animals that are specialized to eat leaves are known as folivores.

Some species have cryptic adaptations by which they use leaves in avoiding predators. For example, the caterpillars of some leaf-roller moths will create a small home in the leaf by folding it over themselves. Several other lepidopteran larvae modify leaves for shelter; perhaps the greatest variety of shelter types occurs among the skipper butterflies (Hesperiidae), which will cut, fold, and bind leaves using silk.[48] Some sawflies similarly roll the leaves of their food plants into tubes. Females of the Attelabidae, so-called leaf-rolling weevils, lay their eggs into leaves that they then roll up as means of protection. Other herbivores and their predators mimic the appearance of the leaf. Reptiles such as some chameleons, and insects such as some katydids, also mimic the oscillating movements of leaves in the wind, moving from side to side or back and forth while evading a possible threat.

Seasonal leaf loss

[edit]

Leaves in temperate, boreal, and seasonally dry zones may be seasonally deciduous (falling off or dying for the inclement season). This mechanism to shed leaves is called abscission. When the leaf is shed, it leaves a leaf scar on the twig. In cold autumns, they sometimes change color, and turn yellow, bright-orange, or red, as various accessory pigments (carotenoids and xanthophylls) are revealed when the tree responds to cold and reduced sunlight by curtailing chlorophyll production. Red anthocyanin pigments are now thought to be produced in the leaf as it dies, possibly to mask the yellow hue left when the chlorophyll is lost—yellow leaves appear to attract herbivores such as aphids.[49] Optical masking of chlorophyll by anthocyanins reduces risk of photo-oxidative damage to leaf cells as they senesce, which otherwise may lower the efficiency of nutrient retrieval from senescing autumn leaves.[50]

Evolutionary adaptation

[edit]

In the course of evolution, leaves have adapted to different environments in the following ways:[citation needed]

- Waxy micro- and nanostructures on the surface reduce wetting by rain and adhesion of contamination (See Lotus effect).

- Divided and compound leaves reduce wind resistance and promote cooling.

- Hairs on the leaf surface trap humidity in dry climates and create a boundary layer reducing water loss.

- Waxy plant cuticles reduce water loss.

- Large surface area provides a large area for capture of sunlight.

- In harmful levels of sunlight, specialized leaves, opaque or partly buried, admit light through a translucent leaf window for photosynthesis at inner leaf surfaces (e.g. Fenestraria).

- Kranz leaf anatomy in plants which perform C4 carbon fixation

- Succulent leaves store water and organic acids for use in CAM photosynthesis.

- Aromatic oils, poisons or pheromones produced by leaf borne glands deter herbivores (e.g. eucalypts).

- Inclusions of crystalline minerals deter herbivores (e.g. silica phytoliths in grasses, raphides in Araceae).

- Petals attract pollinators.

- Spines protect the plants from herbivores (e.g. cacti).

- Stinging hairs to protect against herbivory, e.g. in Urtica dioica and Dendrocnide moroides (Urticaceae).

- Special leaves on carnivorous plants are adapted for trapping food, mainly invertebrate prey, though some species trap small vertebrates as well (see carnivorous plants).

- Bulbs store food and water (e.g. onions).

- Tendrils allow the plant to climb (e.g. peas).

- Bracts and pseudanthia (false flowers) replace normal flower structures when the true flowers are greatly reduced (e.g. spurges, spathes in the Araceae and floral heads in the Asteraceae).

Terminology

[edit]

Shape

[edit]

Edge (margin)

[edit]The edge or margin is the outside perimeter of a leaf. The terms are interchangeable.

| Image | Term | Latin | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entire | Forma integra |

Even; with a smooth margin; without toothing | |

| Ciliate | ciliatus | Fringed with hairs | |

| Crenate | crenatus | Wavy-toothed; dentate with rounded teeth | |

| crenulate | crenulatus | Finely crenate | |

| crisped | crispus | Curly | |

| Dentate | dentatus | Toothed;

may be coarsely dentate, having large teeth or glandular dentate, having teeth which bear glands | |

| Denticulate | denticulatus | Finely toothed | |

| Doubly serrate | duplicato-dentatus | Each tooth bearing smaller teeth | |

| Serrate | serratus | Saw-toothed; with asymmetrical teeth pointing forward | |

| Serrulate | serrulatus | Finely serrate | |

| Sinuate | sinuosus | With deep, wave-like indentations; coarsely crenate | |

| Lobate | lobatus | Indented, with the indentations not reaching the center | |

| Undulate | undulatus | With a wavy edge, shallower than sinuate | |

| Spiny or pungent | spiculatus | With stiff, sharp points such as thistles |

Apex (tip)

[edit]

Base

[edit]- Acuminate

- Coming to a sharp, narrow, prolonged point.

- Acute

- Coming to a sharp, but not prolonged point.

- Auriculate

- Ear-shaped.

- Cordate

- Heart-shaped with the notch towards the stalk.

- Cuneate

- Wedge-shaped.

- Hastate

- Shaped like an halberd and with the basal lobes pointing outward.

- Oblique

- Slanting.

- Reniform

- Kidney-shaped but rounder and broader than long.

- Rounded

- Curving shape.

- Sagittate

- Shaped like an arrowhead and with the acute basal lobes pointing downward.

- Truncate

- Ending abruptly with a flat end, that looks cut off.

Surface

[edit]

The leaf surface is also host to a large variety of microorganisms; in this context it is referred to as the phyllosphere.

- Lepidote

- Covered with fine scurfy scales.

Hairiness

[edit]

"Hairs" on plants are properly called trichomes. Leaves can show several degrees of hairiness. The meaning of several of the following terms can overlap.

- Arachnoid, or arachnose

- With many fine, entangled hairs giving a cobwebby appearance.

- Barbellate

- With finely barbed hairs (barbellae).

- Bearded

- With long, stiff hairs.

- Bristly

- With stiff hair-like prickles.

- Canescent

- Hoary with dense grayish-white pubescence.

- Ciliate

- Marginally fringed with short hairs (cilia).

- Ciliolate

- Minutely ciliate.

- Floccose

- With flocks of soft, woolly hairs, which tend to rub off.

- Glabrescent

- Losing hairs with age.

- Glabrous

- No hairs of any kind present.

- Glandular

- With a gland at the tip of the hair.

- Hirsute

- With rather rough or stiff hairs.

- Hispid

- With rigid, bristly hairs.

- Hispidulous

- Minutely hispid.

- Hoary

- With a fine, close grayish-white pubescence.

- Lanate, or lanose

- With woolly hairs.

- Pilose

- With soft, clearly separated hairs.

- Puberulent, or puberulous

- With fine, minute hairs.

- Pubescent

- With soft, short and erect hairs.

- Scabrous, or scabrid

- Rough to the touch.

- Sericeous

- Silky appearance through fine, straight and appressed (lying close and flat) hairs.

- Silky

- With adpressed, soft and straight pubescence.

- Stellate, or stelliform

- With star-shaped hairs.

- Strigose

- With appressed, sharp, straight and stiff hairs.

- Tomentose

- Densely pubescent with matted, soft white woolly hairs.

- Cano-tomentose

- Between canescent and tomentose.

- Felted-tomentose

- Woolly and matted with curly hairs.

- Tomentulose

- Minutely or only slightly tomentose.

- Villous

- With long and soft hairs, usually curved.

- Woolly

- With long, soft and tortuous or matted hairs.

Timing

[edit]- Hysteranthous

- Developing after the flowers [51]

- Synanthous

- Developing at the same time as the flowers [52]

Venation

[edit]Classification

[edit]A number of different classification systems of the patterns of leaf veins (venation or veination) have been described,[28] starting with Ettingshausen (1861),[53] together with many different descriptive terms, and the terminology has been described as "formidable".[28] One of the commonest among these is the Hickey system, originally developed for "dicotyledons" and using a number of Ettingshausen's terms derived from Greek (1973–1979):[54][55][56] (see also: Simpson Figure 9.12, p. 468)[28]

Hickey system

[edit]- 1. Pinnate (feather-veined, reticulate, pinnate-netted, penniribbed, penninerved, or penniveined)

- The veins arise pinnately (feather like) from a single primary vein (mid-vein) and subdivide into secondary veinlets, known as higher order veins. These, in turn, form a complicated network. This type of venation is typical for (but by no means limited to) "dicotyledons" (non monocotyledon angiosperms). E.g., Ostrya. There are three subtypes of pinnate venation:

- Craspedodromous (Greek: kraspedon – edge, dromos – running)

- The major veins reach to the margin of the leaf.

- Camptodromous

- Major veins extend close to the margin, but bend before they intersect with the margin.

- Hyphodromous

- All secondary veins are absent, rudimentary or concealed

These in turn have a number of further subtypes such as eucamptodromous, where secondary veins curve near the margin without joining adjacent secondary veins.

- 2. Parallelodromous (parallel-veined, parallel-ribbed, parallel-nerved, penniparallel, striate)

- Two or more primary veins originating beside each other at the leaf base, and running parallel to each other to the apex and then converging there. Commissural veins (small veins) connect the major parallel veins. Typical for most monocotyledons, such as grasses. The additional terms marginal (primary veins reach the margin), and reticulate (net-veined) are also used.

- 3. Campylodromous (campylos – curve)

- Several primary veins or branches originating at or close to a single point and running in recurved arches, then converging at apex. E.g. Maianthemum .

- 4. Acrodromous

- Two or more primary or well developed secondary veins in convergent arches towards apex, without basal recurvature as in Campylodromous. May be basal or suprabasal depending on origin, and perfect or imperfect depending on whether they reach to 2/3 of the way to the apex. E.g., Miconia (basal type), Endlicheria (suprabasal type).

- 5. Actinodromous

- Three or more primary veins diverging radially from a single point. E.g., Arcangelisia (basal type), Givotia (suprabasal type).

- 6. Palinactodromous

- Primary veins with one or more points of secondary dichotomous branching beyond the primary divergence, either closely or more distantly spaced. E.g., Platanus.

Types 4–6 may similarly be subclassified as basal (primaries joined at the base of the blade) or suprabasal (diverging above the blade base), and perfect or imperfect, but also flabellate.

At about the same time, Melville (1976) described a system applicable to all Angiosperms and using Latin and English terminology.[57] Melville also had six divisions, based on the order in which veins develop.

- Arbuscular (arbuscularis)

- Branching repeatedly by regular dichotomy to give rise to a three dimensional bush-like structure consisting of linear segment (2 subclasses)

- Flabellate (flabellatus)

- Primary veins straight or only slightly curved, diverging from the base in a fan-like manner (4 subclasses)

- Palmate (palmatus)

- Curved primary veins (3 subclasses)

- Pinnate (pinnatus)

- Single primary vein, the midrib, along which straight or arching secondary veins are arranged at more or less regular intervals (6 subclasses)

- Collimate (collimatus)

- Numerous longitudinally parallel primary veins arising from a transverse meristem (5 subclasses)

- Conglutinate (conglutinatus)

- Derived from fused pinnate leaflets (3 subclasses)

A modified form of the Hickey system was later incorporated into the Smithsonian classification (1999) which proposed seven main types of venation, based on the architecture of the primary veins, adding Flabellate as an additional main type. Further classification was then made on the basis of secondary veins, with 12 further types, such as;

- Brochidodromous

- Closed form in which the secondaries are joined in a series of prominent arches, as in Hildegardia.

- Craspedodromous

- Open form with secondaries terminating at the margin, in toothed leaves, as in Celtis.

- Eucamptodromous

- Intermediate form with upturned secondaries that gradually diminish apically but inside the margin, and connected by intermediate tertiary veins rather than loops between secondaries, as in Cornus.

- Cladodromous

- Secondaries freely branching toward the margin, as in Rhus.

terms which had been used as subtypes in the original Hickey system.[58]

Hildegardia migeodii

Celtis occidentalis

Cornus officinalis

Rhus ovata

Further descriptions included the higher order, or minor veins and the patterns of areoles (see Leaf Architecture Working Group, Figures 28–29).[58]

- Flabellate

- Several to many equal fine basal veins diverging radially at low angles and branching apically. E.g. Paranomus.

Analyses of vein patterns often fall into consideration of the vein orders, primary vein type, secondary vein type (major veins), and minor vein density. A number of authors have adopted simplified versions of these schemes.[59][28] At its simplest the primary vein types can be considered in three or four groups depending on the plant divisions being considered;

- pinnate

- palmate

- parallel

where palmate refers to multiple primary veins that radiate from the petiole, as opposed to branching from the central main vein in the pinnate form, and encompasses both of Hickey types 4 and 5, which are preserved as subtypes; e.g., palmate-acrodromous (see National Park Service Leaf Guide).[60]

- Palmate, Palmate-netted, palmate-veined, fan-veined

- Several main veins of approximately equal size diverge from a common point near the leaf base where the petiole attaches, and radiate toward the edge of the leaf. Palmately veined leaves are often lobed or divided with lobes radiating from the common point. They may vary in the number of primary veins (3 or more), but always radiate from a common point.[61] e.g. most Acer (maples).

Other systems

[edit]Alternatively, Simpson uses:[28]

- Uninervous

- Central midrib with no lateral veins (microphyllous), seen in the non-seed bearing tracheophytes, such as horsetails

- Dichotomous

- Veins successively branching into equally sized veins from a common point, forming a Y junction, fanning out. Among temperate woody plants, Ginkgo biloba is the only species exhibiting dichotomous venation. Also some pteridophytes (ferns).[61]

- Parallel

- Primary and secondary veins roughly parallel to each other, running the length of the leaf, often connected by short perpendicular links, rather than form networks. In some species, the parallel veins join at the base and apex, such as needle-type evergreens and grasses. Characteristic of monocotyledons, but exceptions include Arisaema, and as below, under netted.[61]

- Netted (reticulate, pinnate)

- A prominent midvein with secondary veins branching off along both sides of it. The name derives from the ultimate veinlets which form an interconnecting net like pattern or network. (The primary and secondary venation may be referred to as pinnate, while the net like finer veins are referred to as netted or reticulate); most non-monocot angiosperms, exceptions including Calophyllum. Some monocots have reticulate venation, including Colocasia, Dioscorea and Smilax.[61]

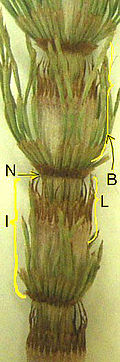

Reduced microphyllous leaves (L) arising in whorl from node

Dichotomous venation

However, these simplified systems allow for further division into multiple subtypes. Simpson,[28] (and others)[62] divides parallel and netted (and some use only these two terms for Angiosperms)[63] on the basis of the number of primary veins (costa) as follows;

- Parallel

- Penni-parallel (pinnate, pinnate parallel, unicostate parallel)

- Single central prominent midrib, secondary veins from this arise perpendicularly to it and run parallel to each other towards the margin or tip, but do not join (anastomose). The term unicostate refers to the prominence of the single midrib (costa) running the length of the leaf from base to apex. e.g. Zingiberales, such as Bananas etc.

- Palmate-parallel (multicostate parallel)

- Several equally prominent primary veins arising from a single point at the base and running parallel towards tip or margin. The term multicostate refers to having more than one prominent main vein. e.g. "fan" (palmate) palms (Arecaceae)

- Multicostate parallel convergent

- Mid-veins converge at apex e.g. Bambusa arundinacea = B. bambos (Aracaceae), Eichornia

- Multicostate parallel divergent

- Mid-veins diverge more or less parallel towards the margin e.g. Borassus (Poaceae), fan palms

- Netted (Reticulate)

- Pinnately (veined, netted, unicostate reticulate)

- Single prominent midrib running from base to apex, secondary veins arising on both sides along the length of the primary midrib, running towards the margin or apex (tip), with a network of smaller veinlets forming a reticulum (mesh or network). e.g. Mangifera, Ficus religiosa, Psidium guajava, Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, Salix alba

- Palmately (multicostate reticulate)

- More than one primary veins arising from a single point, running from base to apex. e.g. Liquidambar styraciflua This may be further subdivided;

- Multicostate convergent

- Major veins diverge from origin at base then converge towards the tip. e.g. Zizyphus, Smilax, Cinnamomum

- Multicostate divergent

- All major veins diverge towards the tip. e.g. Gossypium, Cucurbita, Carica papaya, Ricinus communis

- Ternately (ternate-netted)

- Three primary veins, as above, e.g. (see) Ceanothus leucodermis,[64] C. tomentosus,[65] Encelia farinosa

Palmate-parallel

Multicostate parallel convergent

Multicostate parallel divergent

Pinnately netted

Palmately netted

Multicostate palmate convergent

Multicostate palmate divergent

These complex systems are not used much in morphological descriptions of taxa, but have usefulness in plant identification, [28] although criticized as being unduly burdened with jargon.[66]

An older, even simpler system, used in some flora[67] uses only two categories, open and closed.

- Open: Higher order veins have free endings among the cells and are more characteristic of non-monocotyledon angiosperms. They are more likely to be associated with leaf shapes that are toothed, lobed or compound. They may be subdivided as;

- Pinnate (feather-veined) leaves, with a main central vein or rib (midrib), from which the remainder of the vein system arises

- Palmate, in which three or more main ribs rise together at the base of the leaf, and diverge upward.

- Dichotomous, as in ferns, where the veins fork repeatedly

- Closed: Higher order veins are connected in loops without ending freely among the cells. These tend to be in leaves with smooth outlines, and are characteristic of monocotyledons.

- They may be subdivided into whether the veins run parallel, as in grasses, or have other patterns.

Other descriptive terms

[edit]There are also many other descriptive terms, often with very specialized usage and confined to specific taxonomic groups.[68] The conspicuousness of veins depends on a number of features. These include the width of the veins, their prominence in relation to the lamina surface and the degree of opacity of the surface, which may hide finer veins. In this regard, veins are called obscure and the order of veins that are obscured and whether upper, lower or both surfaces, further specified.[69][61]

Terms that describe vein prominence include bullate, channelled, flat, guttered, impressed, prominent and recessed (Fig. 6.1 Hawthorne & Lawrence 2013).[66][70] Veins may show different types of prominence in different areas of the leaf. For instance Pimenta racemosa has a channeled midrib on the upper surface, but this is prominent on the lower surface.[66]

Describing vein prominence:

- Bullate

- Surface of leaf raised in a series of domes between the veins on the upper surface, and therefore also with marked depressions. e.g. Rytigynia pauciflora,[71] Vitis vinifera

- Channelled (canalicululate)

- Veins sunken below the surface, resulting in a rounded channel. Sometimes confused with "guttered" because the channels may function as gutters for rain to run off and allow drying, as in many Melastomataceae.[72] e.g. (see) Pimenta racemosa (Myrtaceae),[73] Clidemia hirta (Melastomataceae).

- Guttered

- Veins partly prominent, the crest above the leaf lamina surface, but with channels running along each side, like gutters

- Impressed

- Vein forming raised line or ridge which lies below the plane of the surface which bears it, as if pressed into it, and are often exposed on the lower surface. Tissue near the veins often appears to pucker, giving them a sunken or embossed appearance

- Obscure

- Veins not visible, or not at all clear; if unspecified, then not visible with the naked eye. e.g. Berberis gagnepainii. In this Berberis, the veins are only obscure on the undersurface.[74]

- Prominent

- Vein raised above surrounding surface so to be easily felt when stroked with finger. e.g. (see) Pimenta racemosa,[73] Spathiphyllum cannifolium[75]

- Recessed

- Vein is sunk below the surface, more prominent than surrounding tissues but more sunken in channel than with impressed veins. e.g. Viburnum plicatum.

Obscure (under surface)

Prominent

Recessed

Describing other features:

- Plinervy (plinerved)

- More than one main vein (nerve) at the base. Lateral secondary veins branching from a point above the base of the leaf. Usually expressed as a suffix, as in 3-plinerved or triplinerved leaf. In a 3-plinerved (triplinerved) leaf three main veins branch above the base of the lamina (two secondary veins and the main vein) and run essentially parallel subsequently, as in Ceanothus and in Celtis. Similarly, a quintuplinerve (five-veined) leaf has four secondary veins and a main vein. A pattern with 3–7 veins is especially conspicuous in Melastomataceae. The term has also been used in Vaccinieae. The term has been used as synonymous with acrodromous, palmate-acrodromous or suprabasal acrodromous, and is thought to be too broadly defined.[76][76]

- Scalariform

- Veins arranged like the rungs of a ladder, particularly higher order veins

- Submarginal

- Veins running close to leaf margin

- Trinerved

- 2 major basal nerves besides the midrib

Diagrams of venation patterns

[edit]Size

[edit]The terms megaphyll, macrophyll, mesophyll, notophyll, microphyll, nanophyll and leptophyll are used to describe leaf sizes (in descending order), in a classification devised in 1934 by Christen C. Raunkiær and since modified by others.[77][78]

See also

[edit]- Glossary of leaf morphology

- Glossary of plant morphology § Leaves

- Crown (botany)

- Evolutionary history of leaves

- Evolutionary development of leaves

- Leaf area index

- Leaf protein concentrate

- Leaf sensor – a device that measures the moisture level in plant leaves

- Leaf shape

- Vernation – sprouting of leaves, also the arrangement of leaves in the bud

- Musical leaf

References

[edit]- ^ a b Esau 2006.

- ^ Haupt 1953.

- ^ a b Mauseth 2009.

- ^ "Shoot system". Dictionary of botanic terminology. Cactus Art Nursery. n.d. Archived from the original on May 4, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ James et al 1999.

- ^ a b c d e Stewart & Rothwell 1993.

- ^ Cooney-Sovetts & Sattler 1987.

- ^ Tsukaya 2013.

- ^ Feugier 2006.

- ^ Purcell 2016.

- ^ Willert et al 1992.

- ^ Bayer 1982.

- ^ a b c Simpson 2011, p. 356.

- ^ Krogh 2010.

- ^ James & Bell 2000.

- ^ Heywood et al 2007.

- ^ Simpson 2011, pp. 356–357.

- ^ Hallé 1977.

- ^ a b c Botany Illustrated: Introduction to Plants Major Groups Flowering Plant Families. Thomson Science. 1984. p. 21.

- ^ Didier Reinhardt and Cris Kuhlemeier, "Phyllotaxis in higher plants", in Michael T. McManus, Bruce Veit, eds., Meristematic Tissues in Plant Growth and Development, January 2002, ISBN 978-1-84127-227-6, Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ Coxeter HS (1961). Introduction to geometry. Wiley. p. 169.

- ^ Reinhardt and Kuhlemeier, p. 175

- ^ Yonekura, Takaaki; Iwamoto, Akitoshi; Fujita, Hironori; Sugiyama, Munetaka (June 6, 2019). Umulis, David (ed.). "Mathematical model studies of the comprehensive generation of major and minor phyllotactic patterns in plants with a predominant focus on orixate phyllotaxis". PLOS Computational Biology. 15 (6) e1007044. Bibcode:2019PLSCB..15E7044Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007044. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 6553687. PMID 31170142.

- ^ Rolland-Lagan et al 2009.

- ^ a b c Walls 2011.

- ^ a b c Dickison 2000.

- ^ a b Rudall 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Simpson 2011, Leaf venation pp. 465–468

- ^ a b c d Sack & Scoffoni 2013.

- ^ a b c Roth-Nebelsick et al 2001.

- ^ Ueno et al 2006.

- ^ Runions et al 2005.

- ^ Massey & Murphy 1996, Surface-Venation-Texure

- ^ Bagchi et al 2016.

- ^ Cote 2009.

- ^ Clements 1905.

- ^ Couder et al 2002.

- ^ Corson et al 2009.

- ^ Laguna et al 2008.

- ^ Arber 1950.

- ^ Rutishauser & Sattler 1997.

- ^ Lacroix et al 2003.

- ^ Eckardt & Baum 2010.

- ^ Poiré, Richard; Wiese-Klinkenberg, Anika; Parent, Boris; Mielewczik, Michael; Schurr, Ulrich; Tardieu, François; Walter, Achim (2010). "Diel time-courses of leaf growth in monocot and dicot species: endogenous rhythms and temperature effects". Journal of Experimental Botany. 61 (6): 1751–1759. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq049. ISSN 1460-2431. PMC 2852670. PMID 20299442.

- ^ Mielewczik, Michael; Friedli, Michael; Kirchgessner, Norbert; Walter, Achim (July 25, 2013). "Diel leaf growth of soybean: a novel method to analyze two-dimensional leaf expansion in high temporal resolution based on a marker tracking approach (Martrack Leaf)". Plant Methods. 9 (1): 30. Bibcode:2013PlMet...9...30M. doi:10.1186/1746-4811-9-30. hdl:20.500.11850/76534. ISSN 1746-4811. PMC 3750653. PMID 23883317.

- ^ Friedli, Michael; Walter, Achim (2015). "Diel growth patterns of young soybean ( G lycine max ) leaflets are synchronous throughout different positions on a plant". Plant, Cell & Environment. 38 (3): 514–524. Bibcode:2015PCEnv..38..514F. doi:10.1111/pce.12407. ISSN 0140-7791. PMID 25041284.

- ^ a b c d e Read & Stokes 2006.

- ^ Greeney, Harold F; Jones, Meg T (2003). "Shelter building in the Hesperiidae: a classification scheme for larval shelters". The Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera. 37: 27–36. doi:10.5962/p.266551. Retrieved January 13, 2025.

- ^ Doring et al 2009.

- ^ Feild et al 2001.

- ^ "Kew Glossary – definition of hysteranthous". December 3, 2013. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Kew Glossary – definition of synanthous". December 3, 2013. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ettingshausen 1861.

- ^ Hickey 1973.

- ^ Hickey & Wolfe 1975.

- ^ Hickey 1979.

- ^ Melville 1976.

- ^ a b Leaf Architecture Working Group 1999.

- ^ Judd et al 2007.

- ^ Florissant Leaf Key 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Kling et al 2005, Leaf Venation

- ^ Berg 2007.

- ^ Angiosperm Morphology 2017, Venation

- ^ Simpson 2017, Ceanothus leucodermis

- ^ Simpson 2017, Ceanothus tomentosus

- ^ a b c Hawthorne & Lawrence 2013, Leaf venation pp. 135–136

- ^ Cullen et al 2011.

- ^ Neotropikey 2017.

- ^ Oxford herbaria glossary 2017.

- ^ Oxford herbaria glossary 2017, Vein prominence

- ^ Verdcourt & Bridson 1991.

- ^ Hemsley & Poole 2004, Leaf morphology and drying p. 254

- ^ a b Hughes 2017, Pimenta racemosa

- ^ Cullen et al 2011, Berberis gagnepainii vol. II p. 398

- ^ Kwantlen 2015, Spathiphyllum cannifolium

- ^ a b Pedraza-Peñalosa 2013.

- ^ Whitten et al 1997.

- ^ Webb, Len (October 1, 1959). "A Physiognomic Classification of Australian Rain Forests". Journal of Ecology. 47 (3). British Ecological Society : Journal of Ecology Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 551–570: 555. Bibcode:1959JEcol..47..551W. doi:10.2307/2257290. JSTOR 2257290.

Bibliography

[edit]Books and chapters

[edit]- Arber, Agnes (1950). The Natural Philosophy of Plant Form. CUP Archive. GGKEY:HCBB8RZREL4.

- Bayer, M. B. (1982). The New Haworthia Handbook. Kirstenbosch: National Botanic Gardens of South Africa. ISBN 978-0-620-05632-8. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved July 25, 2018.

- Berg, Linda (March 23, 2007). Introductory Botany: Plants, People, and the Environment, Media Edition. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-111-79426-2.

- Cullen, James; Knees, Sabina G.; Cubey, H. Suzanne Cubey, eds. (2011) [1984–2000]. The European Garden Flora, Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both Out-of-Doors and Under Glass. 5 vols (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- Cutter, E.G. (1969). Plant Anatomy, experiment and interpretation, Part 2 Organs. London: Edward Arnold. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7131-2302-9.

- Dickison, William C. (2000). Integrative Plant Anatomy. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-050891-7.

- Esau, Katherine (2006) [1953]. Evert, Ray F (ed.). Esau's Plant Anatomy: Meristems, Cells, and Tissues of the Plant Body: Their Structure, Function, and Development (3rd. ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. ISBN 978-0-470-04737-8. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Ettingshausen, C. (1861). Die Blatt-Skelete der Dicotyledonen mit besonderer Ruchsicht auf die Untersuchung und Bestimmung der fossilen Pflanzenreste. Vienna: Classification of the Architecture of Dicotyledonous.

- Haupt, Arthur Wing (1953). Plant morphology. McGraw-Hill.

- Hawthorne, William; Lawrence, Anna (2013). Plant Identification: Creating User-Friendly Field Guides for Biodiversity Management. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-55972-3.

- Hemsley, Alan R.; Poole, Imogen, eds. (2004). The Evolution of Plant Physiology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-047272-0.

- Heywood, V.H.; Brummitt, R.K.; Culham, A.; Seberg, O. (2007). Flowering plant families of the world. New York: Firefly books. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-55407-206-4.

- Hickey, LJ. A revised classification of the architecture of dicotyledonous leaves. pp. i 5–39., in Metcalfe & Chalk (1979)

- Judd, Walter S.; Campbell, Christopher S.; Kellogg, Elizabeth A.; Stevens, Peter F.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2007) [1st ed. 1999, 2nd 2002]. Plant systematics: a phylogenetic approach (3rd ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-407-2. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Krogh, David (2010), Biology: A Guide to the Natural World (5th ed.), Benjamin-Cummings Publishing Company, p. 463, ISBN 978-0-321-61655-5, archived from the original on January 24, 2023, retrieved May 24, 2016

- Leaf Architecture Working Group (1999). Manual of Leaf Architecture - morphological description and categorization of dicotyledonous and net-veined monocotyledonous angiosperms (PDF). Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-9677554-0-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- Marloth, Rudolf (1913–1932). The Flora of South Africa: With Synopical Tables of the Genera of the Higher Plants. 6 vols. Cape Town: Darter Bros. & Co. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Mauseth, James D. (2009). Botany: an introduction to plant biology (4th ed.). Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-5345-0.

- Metcalfe, CR; Chalk, L, eds. (1979) [1957]. Anatomy of the Dicotyledons: Leaves, stem and wood in relation to taxonomy, with notes on economic uses. 2 vols (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854383-1.

- Prance, Ghillean Tolmie (1985). Leaves: the formation, characteristics and uses of hundreds of leaves found in all parts of the world. Photographs by Kjell B. Sandved. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-54104-3.

- Rudall, Paula J. (2007). Anatomy of flowering plants: an introduction to structure and development (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69245-8. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Simpson, Michael G. (2011). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-051404-8. Archived from the original on January 17, 2023. Retrieved May 24, 2016.

- Stewart, Wilson N; Rothwell, Gar W. (1993) [1983]. Paleobotany and the Evolution of Plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38294-6.

- Verdcourt, Bernard; Bridson, Diane M. (1991). Flora of tropical East Africa - Rubiaceae Volume 3. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-6191-357-3.

- Whitten, Tony; Soeriaatmadja, Roehayat Emon; Afiff, Suraya A. (1997). Ecology of Java and Bali. Oxford University Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-962-593-072-5. Archived from the original on September 6, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- Willert, Dieter J. von; Eller, BM; Werger, MJA; Brinckmann, E; Ihlenfeldt, H-D (1992). Life Strategies of Succulents in Deserts: With Special Reference to the Namib Desert. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-24468-8.

Articles and theses

[edit]- Bagchi, Debjani; Dasgupta, Avik; Gondaliya, Amit D.; Rajput, Kishore S. (2016). "Insights from the Plant World: A Fractal Analysis Approach to Tune Mechanical Rigidity of Scaffolding Matrix in Thin Films". Advanced Materials Research. 1141: 57–64. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.1141.57. S2CID 138338270.

- Clements, Edith Schwartz (December 1905). "The Relation of Leaf Structure to Physical Factors". Transactions of the American Microscopical Society. 26: 19–98. doi:10.2307/3220956. JSTOR 3220956. Archived from the original on August 4, 2023. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- Cooney-Sovetts, C.; Sattler, R. (1987). "Phylloclade development in the Asparagaceae: An example of homoeosis". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 94 (3): 327–371. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1986.tb01053.x.

- Corson, Francis; Adda-Bedia, Mokhtar; Boudaoud, Arezki (2009). "In silico leaf venation networks: Growth and reorganization driven by mechanical forces" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 259 (3): 440–448. Bibcode:2009JThBi.259..440C. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.05.002. PMID 19446571. S2CID 25560670. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017.

- Cote, G. G. (2009). "Diversity and distribution of idioblasts producing calcium oxalate crystals in Dieffenbachia seguine (Araceae)". American Journal of Botany. 96 (7): 1245–1254. Bibcode:2009AmJB...96.1245C. doi:10.3732/ajb.0800276. PMID 21628273.

- Couder, Y.; Pauchard, L.; Allain, C.; Adda-Bedia, M.; Douady, S. (July 1, 2002). "The leaf venation as formed in a tensorial field" (PDF). The European Physical Journal B. 28 (2): 135–138. Bibcode:2002EPJB...28..135C. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2002-00211-1. S2CID 51687210. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 9, 2017.

- Döring, T. F; Archetti, M.; Hardie, J. (January 7, 2009). "Autumn leaves seen through herbivore eyes". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1654): 121–127. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0858. PMC 2614250. PMID 18782744.

- Eckardt, N. A.; Baum, D. (July 20, 2010). "The Podostemad Puzzle: The Evolution of Unusual Morphology in the Podostemaceae". The Plant Cell Online. 22 (7): 2104. Bibcode:2010PlanC..22.2104E. doi:10.1105/tpc.110.220711. PMC 2929115. PMID 20647343.

- Feugier, François (December 14, 2006). Models of Vascular Pattern Formation in Leaves (PhD Thesis). University of Paris VI. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Feild, T. S.; Lee, D. W.; Holbrook, N. M. (October 1, 2001). "Why Leaves Turn Red in Autumn. The Role of Anthocyanins in Senescing Leaves of Red-Osier Dogwood". Plant Physiology. 127 (2): 566–574. doi:10.1104/pp.010063. PMC 125091. PMID 11598230.

- Hallé, F. (1977). "The longest leaf in palms". Principes. 21: 18.

- Hickey, Leo J. (January 1, 1973). "Classification of the Architecture of Dicotyledonous Leaves" (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 60 (1): 17–33. doi:10.2307/2441319. JSTOR 2441319. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- Hickey, Leo J.; Wolfe, Jack A. (1975). "The Bases of Angiosperm Phylogeny: Vegetative Morphology". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 62 (3): 538–589. Bibcode:1975AnMBG..62..538H. doi:10.2307/2395267. JSTOR 2395267. Archived from the original on October 31, 2022. Retrieved September 6, 2023.

- Ingersoll, Ernest (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. XVII.

- James, S. A.; Bell, D. T. (2000). "Influence of light availability on leaf structure and growth of two Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus provenances" (PDF). Tree Physiology. 20 (15): 1007–1018. doi:10.1093/treephys/20.15.1007. PMID 11305455. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- Lacroix, C.; Jeune, B.; Purcell-Macdonald, S. (2003). "Shoot and compound leaf comparisons in eudicots: Dynamic morphology as an alternative approach". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 143 (3): 219–230. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.00222.x. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- Laguna, Maria F.; Bohn, Steffen; Jagla, Eduardo A.; Bourne, Philip E. (2008). "The Role of Elastic Stresses on Leaf Venation Morphogenesis". PLOS Computational Biology. 4 (4) e1000055. arXiv:0705.0902. Bibcode:2008PLSCB...4E0055L. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000055. PMC 2275310. PMID 18404203.

- Melville, R. (November 1976). "The Terminology of Leaf Architecture". Taxon. 25 (5/6): 549–561. Bibcode:1976Taxon..25..549M. doi:10.2307/1220108. JSTOR 1220108.

- Pedraza-Peñalosa, Paola; Salinas, Nelson R.; Wheeler, Ward C. (April 26, 2013). "Venation patterns of neotropical blueberries (Vaccinieae: Ericaceae) and their phylogenetic utility" (PDF). Phytotaxa. 96 (1): 1. Bibcode:2013Phytx..96....1P. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.96.1.1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- Read, J.; Stokes, A. (October 1, 2006). "Plant biomechanics in an ecological context". American Journal of Botany. 93 (10): 1546–1565. Bibcode:2006AmJB...93.1546R. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.10.1546. PMID 21642101.

- Rolland-Lagan, Anne-Gaëlle; Amin, Mira; Pakulska, Malgosia (January 2009). "Quantifying leaf venation patterns: two-dimensional maps". The Plant Journal. 57 (1): 195–205. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03678.x. PMID 18785998.

- Roth-Nebelsick, A; Uhl, Dieter; Mosbrugger, Volker; Kerp, Hans (May 2001). "Evolution and Function of Leaf Venation Architecture: A Review". Annals of Botany. 87 (5): 553–566. Bibcode:2001AnBot..87..553R. doi:10.1006/anbo.2001.1391.

- Runions, Adam; Fuhrer, Martin; Lane, Brendan; Federl, Pavol; Rolland-Lagan, Anne-Gaëlle; Prusinkiewicz, Przemyslaw (January 1, 2005). "Modeling and visualization of leaf venation patterns". ACM SIGGRAPH 2005 Papers. Vol. 24. pp. 702–711. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.102.1926. doi:10.1145/1186822.1073251. ISBN 978-1-4503-7825-3. S2CID 2629700.

- Rutishauser, R.; Sattler, R. (1997). "Expression of shoot processes in leaf development of Polemonium caeruleum". Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik. 119: 563–582.

- Sack, Lawren; Scoffoni, Christine (June 2013). "Leaf venation: structure, function, development, evolution, ecology and applications in the past, present and future". New Phytologist. 198 (4): 983–1000. Bibcode:2013NewPh.198..983S. doi:10.1111/nph.12253. PMID 23600478.

- Shelley, A.J.; Smith, W.K.; Vogelmann, T.C. (1998). "Ontogenetic differences in mesophyll structure and chlorophyll distribution in Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus (Myrtaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 86 (2): 198–207. doi:10.2307/2656937. JSTOR 2656937. PMID 21680359.

- Tsukaya, Hirokazu (January 2013). "Leaf Development". The Arabidopsis Book. 11 e0163. doi:10.1199/tab.0163. PMC 3711357. PMID 23864837.

- Ueno, Osamu; Kawano, Yukiko; Wakayama, Masataka; Takeda, Tomoshiro (April 1, 2006). "Leaf Vascular Systems in C3 and C4 Grasses: A Two-dimensional Analysis". Annals of Botany. 97 (4): 611–621. doi:10.1093/aob/mcl010. PMC 2803656. PMID 16464879.

- Walls, R. L. (January 25, 2011). "Angiosperm leaf vein patterns are linked to leaf functions in a global-scale data set". American Journal of Botany. 98 (2): 244–253. Bibcode:2011AmJB...98..244W. doi:10.3732/ajb.1000154. PMID 21613113.

Websites