Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Murder

View on Wikipedia

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse committed with the necessary intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisdiction.[1][2][3] This state of mind may, depending upon the jurisdiction, distinguish murder from other forms of unlawful homicide, such as manslaughter. Manslaughter is killing committed in the absence of malice,[note 1] such as in the case of voluntary manslaughter brought about by reasonable provocation, or diminished capacity. Involuntary manslaughter, where it is recognized, is a killing that lacks all but the most attenuated guilty intent, recklessness.

Most societies consider murder to be an extremely serious crime, and thus believe that a person convicted of murder should receive harsh punishments for the purposes of retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, or incapacitation. In most countries, a person convicted of murder generally receives a long-term prison sentence, a life sentence, or capital punishment.[4] Some countries, states, and territories, including the United Kingdom and other countries with English-derived common law, mandate life imprisonment for murder, whether it is subdivided into first-degree murder or otherwise.[5]

Etymology

[edit]The modern English word "murder" descends from the Proto-Indo-European *mŕ̥-trom which meant "killing", a noun derived from *mer- "to die".[6]

Proto-Germanic, in fact, had two nouns derived from this word, later merging into the modern English noun: *murþrą "death, killing, murder" (directly from Proto-Indo-European*mŕ̥-trom), whence Old English morðor "secret or unlawful killing of a person, murder; mortal sin, crime; punishment, torment, misery";[7] and *murþrijô "murderer; homicide" (from the verb *murþrijaną "to murder"), giving Old English myrþra "homicide, murder; murderer". There was a third word for "murder" in Proto-Germanic, continuing Proto-Indo-European *mr̥tós "dead" (compare Latin mors), giving Proto-Germanic *murþą "death, killing, murder" and Old English morþ "death, crime, murder" (compare German Mord).

The -d- first attested in Middle English mordre, mourdre, murder, murdre could have been influenced by Old French murdre, itself derived from the Germanic noun via Frankish *murþra (compare Old High German murdreo, murdiro), though the same sound development can be seen with burden (from burthen). The alternative murther (attested up to the 19th century) springs directly from the Old English forms. Middle English mordre is a verb from Anglo-Saxon myrðrian from Proto-Germanic *murþrijaną, or, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, from the noun.[8]

Definition

[edit]The eighteenth-century English jurist William Blackstone (citing Edward Coke), in his Commentaries on the Laws of England set out the common law definition of murder, which by this definition occurs

when a person, of sound memory and discretion, unlawfully kills any reasonable creature in being and under the king's peace, with malice aforethought, either express or implied.[9]

At common law, murder was normally punishable by death.[10]

The elements of common law murder are:[11]

- unlawful : This distinguishes murder from killings that are done within the boundaries of law, such as capital punishment, justified self-defense, or the killing of enemy combatants by lawful combatants as well as causing collateral damage to non-combatants during a war.[12]

- killing : At common law life ended with cardiopulmonary arrest[11] – the total and irreversible cessation of blood circulation and respiration.[11] With advances in medical technology courts have adopted irreversible cessation of all brain function as marking the end of life.[11]

- through criminal act or omission : Killing can be committed by an act or an omission.[13]

- of a human : This element presents the issue of when life begins. At common law, a fetus was not a human being.[14] Life began when the fetus passed through the vagina and took its first breath.[11]

- by another human : In early common law, suicide was considered murder.[11] The requirement that the person killed be someone other than the perpetrator excluded suicide from the definition of murder.

- with malice aforethought: Originally malice aforethought carried its everyday meaning – a deliberate and premeditated (prior intent) killing of another motivated by ill will. Murder necessarily required that an appreciable time pass between the formation and execution of the intent to kill. The courts broadened the scope of murder by eliminating the requirement of actual premeditation and deliberation as well as true malice. All that was required for malice aforethought to exist is that the perpetrator act with one of the four states of mind that constitutes "malice".

In contrast with manslaughter, murder requires the mental element known as malice aforethought. Mitigating factors that weigh against a finding of intent to kill, such as "loss of control" or "diminished responsibility", may result in the reduction of a murder charge to voluntary manslaughter.[10]

The four states of mind recognized as constituting "malice" are:[15]

- Intent to kill,

- Intent to inflict grievous bodily harm short of death,

- Reckless indifference to an unjustifiably high risk to human life (sometimes described as an "abandoned and malignant heart"), or

- Intent to commit a dangerous felony (the "felony murder" doctrine).

Under state of mind (i), intent to kill, the deadly weapon rule applies. Thus, if the defendant intentionally uses a deadly weapon or instrument against the victim, such use authorizes a permissive inference of intent to kill. Examples of deadly weapons and instruments include but are not limited to guns, knives, deadly toxins or chemicals or gases and even vehicles when intentionally used to harm one or more victims.

Under state of mind (iii), an "abandoned and malignant heart", the killing must result from the defendant's conduct involving a reckless indifference to human life and a conscious disregard of an unreasonable risk of death or serious bodily injury. In Australian jurisdictions, the unreasonable risk must amount to a foreseen probability of death (or grievous bodily harm in most states), as opposed to possibility.[16]

Under state of mind (iv), the felony-murder doctrine, the felony committed must be an inherently dangerous felony, such as burglary, arson, rape, robbery or kidnapping. Importantly, the underlying felony cannot be a lesser included offense such as assault, otherwise all criminal homicides would be murder as all are felonies.

In Spanish criminal law,[17] asesinato (literally 'assassination'): takes place when any of these requirements concur: Treachery (the use of means to avoid risk for the aggressor or to ensure that the crime goes unpunished), price or reward (financial gain) or viciousness (deliberately increasing the pain of the victim). After the last reform of the Spanish Criminal Code, in force since July 1, 2015, another circumstance that turns homicide (homicidio) into assassination is the desire to facilitate the commission of another crime or to prevent it from being discovered.[18]

As with most legal terms, the precise definition of murder varies between jurisdictions and is usually codified in some form of legislation. Even when the legal distinction between murder and manslaughter is clear, it is not unknown for a jury to find a murder defendant guilty of the lesser offense. The jury might sympathize with the defendant (e.g. in a crime of passion, or in the case of a bullied victim who kills their tormentor), and the jury may wish to protect the defendant from a sentence of life imprisonment or execution.

Degrees

[edit]Some jurisdictions divide murder by degrees. The distinction between first- and second-degree murder exists, for example, in Canadian murder law and U.S. murder law. Some US states maintain the offense of capital murder.

The most common division is between first- and second-degree murder. Generally, second-degree murder is common law murder, and first-degree is an aggravated form. The aggravating factors of first-degree murder depend on the jurisdiction, but may include a specific intent to kill, premeditation, or deliberation. In some, murders committed by acts such as strangulation, poisoning, or lying in wait are also treated as first-degree murder.[19] A few states in the U.S. further distinguish third-degree murder, but they differ significantly in which kinds of murders they classify as second-degree versus third-degree. For example, Minnesota and Pennsylvania define third-degree murder as depraved-heart murder (which in most U.S. jurisdictions is called second-degree), whereas Florida defines third-degree murder as felony murder (except when the underlying felony is specifically listed in the definition of first-degree murder).[20][21][22]

Some jurisdictions also distinguish premeditated murder. This is the crime of wrongfully and intentionally causing the death of another human being (also known as murder) after rationally considering the timing or method of doing so, in order to either increase the likelihood of success, or to evade detection or apprehension.[23] State laws in the United States vary as to definitions of "premeditation". In some states, premeditation may be construed as taking place mere seconds before the murder. Premeditated murder is one of the most serious forms of homicide, and is punished more severely than manslaughter or other types of homicide, often with a life sentence without the possibility of parole, or in some countries, the death penalty. In the U.S., federal law () criminalizes premeditated murder, felony murder and second-degree murder committed under situations where federal jurisdiction applies.[24] In Canada, the criminal code classifies murder as either first- or second-degree. The former type of murder is often called premeditated murder, although premeditation is not the only way murder can be classified as first-degree. In the Netherlands, the traditional strict distinction between premeditated intentional killing (classed as murder, moord) and non-premeditated intentional killing (manslaughter, doodslag) is maintained; when differentiating between murder and manslaughter, the only relevant factor is the existence or not of premeditation (rather than the existence or not of mitigating or aggravated factors). Manslaughter (non-premeditated intentional killing) with aggravating factors is punished more severely, but it is not classified as murder, because murder is an offense which always requires premeditation.[25]

Common law

[edit]According to Blackstone, English common law identified murder as a public wrong.[26] According to common law, murder is considered to be malum in se, that is, an act which is evil within itself. An act such as murder is wrong or evil by its very nature, and it is the very nature of the act which does not require any specific detailing or definition in the law to consider murder a crime.[27]

Some jurisdictions still take a common law view of murder. In such jurisdictions, what is considered to be murder is defined by precedent case law or previous decisions of the courts of law. However, although the common law is by nature flexible and adaptable, in the interests both of certainty and of securing convictions, most common law jurisdictions have codified their criminal law and now have statutory definitions of murder.

Exclusions

[edit]General

[edit]Although laws vary by country, there are circumstances of exclusion that are common in many legal systems.

- The killing of enemy combatants who have not surrendered, when committed by lawful combatants in accordance with lawful orders in war, is generally not considered murder. Illicit killings within a war may constitute murder or homicidal war crimes; see Laws of war.

- Self-defense: acting in self-defense or in defense of another person is generally accepted as legal justification for killing a person in situations that would otherwise have been murder. However, a self-defense killing might be considered manslaughter if the killer established control of the situation before the killing took place, such as imperfect self-defense. In the case of self-defense, it is called a "justifiable homicide".[28]

- Unlawful killings without malice or intent are considered manslaughter.

- In many common law countries, provocation is a partial defense to a charge of murder which acts by converting what would otherwise have been murder into manslaughter (this is voluntary manslaughter, which is more severe than involuntary manslaughter).

- Accidental killings are considered homicides. Depending on the circumstances, these may or may not be considered criminal offenses; they are often considered manslaughter.

- Suicide does not constitute murder in most societies. Assisting a suicide, however, may be considered murder in some circumstances.

Specific to certain countries

[edit]- Capital punishment: some countries practice the death penalty. Capital punishment may be ordered by a legitimate court of law as the result of a conviction in a criminal trial with due process for a serious crime. All member states of the Council of Europe are prohibited from using the death penalty.

- Euthanasia, doctor-assisted suicide: the administration of lethal drugs by a doctor to a terminally ill patient, if the intention is solely to alleviate pain, in many jurisdictions it is seen as a special case (see the doctrine of double effect and the case of Dr John Bodkin Adams).[29]

- Killing to prevent the theft of one's property may be legal under certain circumstances, depending on the jurisdiction.[30][31] In 2013, a jury in south Texas acquitted a man who killed a sex worker who attempted to run away with his money.[32]

- Killing an intruder who is found by an owner to be in the owner's home (having entered unlawfully): legal in most US states (see Castle doctrine).[33]

- Killing to prevent specific forms of aggravated rape or sexual assault – killing of attacker by the potential victim or by witnesses to the scene; legal in parts of the US and in various other countries.[34]

- In some countries, the killing for what are considered reasons connected to family honor, usually involving killing due to sexual, religious or caste reasons (known as honor killing), committed frequently by a husband, father or male relative of the victim, is not considered murder; it may not be considered a criminal act or it may be considered a criminal offense other than murder.[35][36] International law, including the Istanbul Convention (the first legally binding convention against domestic violence and violence against women) prohibits these types of killings (see Article 42 – Unacceptable justifications for crimes, including crimes committed in the name of so-called honor).[37]

- In the United States, in most states and in federal jurisdiction, a killing by a police officer is excluded from prosecution if the officer reasonably believes they are being threatened with deadly force by the victim. This may include such actions by the victim as reaching into a glove compartment or pocket for license and registration, if the officer reasonably believes that the victim might be reaching for a gun.[38]

Victim

[edit]All jurisdictions require that the victim be a natural person; that is, a human being who was still alive before being murdered. In other words, under the law one cannot murder a corpse, a corporation, a non-human animal, or any other non-human organism such as a plant or bacterium.

California's murder statute, penal code section 187, expressly mentioned a fetus as being capable of being killed, and was interpreted by the Supreme Court of California in 1994 as not requiring any proof of the viability of the fetus as a prerequisite to a murder conviction.[39] This holding has two implications. Firstly, a defendant in California can be convicted of murder for killing a fetus which the mother herself could have terminated without committing a crime.[39] And secondly, as stated by Justice Stanley Mosk in his dissent, because women carrying nonviable fetuses may not be visibly pregnant, it may be possible for a defendant to be convicted of intentionally murdering a person they did not know existed.[39]

Mitigating circumstances

[edit]Some countries allow conditions that "affect the balance of the mind" to be regarded as mitigating circumstances. This means that a person may be found guilty of "manslaughter" on the basis of "diminished responsibility" rather than being found guilty of murder, if it can be proved that the killer was suffering from a condition that affected their judgment at the time. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and medication side-effects are examples of conditions that may be taken into account when assessing responsibility.

Insanity

[edit]Mental disorder may apply to a wide range of disorders including psychosis caused by schizophrenia and dementia, and excuse the person from the need to undergo the stress of a trial as to liability. Usually, sociopathy and other personality disorders are not legally considered insanity. In some jurisdictions, following the pre-trial hearing to determine the extent of the disorder, the defense of "not guilty by reason of insanity" may be used to get a not guilty verdict.[40] This defense has two elements:

- That the defendant had a serious mental illness, disease, or defect

- That the defendant's mental condition, at the time of the killing, rendered the perpetrator unable to determine right from wrong, or that what they were doing was wrong

Under New York law, for example:

§ 40.15 Mental disease or defect. In any prosecution for an offense, it is an affirmative defence that when the defendant engaged in the proscribed conduct, he lacked criminal responsibility by reason of mental disease or defect. Such lack of criminal responsibility means that at the time of such conduct, as a result of mental disease or defect, he lacked substantial capacity to know or appreciate either: 1. The nature and consequences of such conduct; or 2. That such conduct was wrong.

— N.Y. Penal Law, § 40.15[41]

Under the French Penal Code:

Article 122-1

- A person is not criminally liable who, when the act was committed, was suffering from a psychological or neuropsychological disorder which destroyed his discernment or his ability to control his actions.

- A person who, at the time he acted, was suffering from a psychological or neuropsychological disorder which reduced his discernment or impeded his ability to control his actions, remains punishable; however, the court shall take this into account when it decides the penalty and determines its regime.

— Penal Code §122-1 found at Legifrance web site

Those who successfully argue a defense based on a mental disorder are usually referred to mandatory clinical treatment until they are certified safe to be released back into the community, rather than prison.[42]

Postpartum depression

[edit]Postpartum depression (also known as post-natal depression) is recognized in some countries as a mitigating factor in cases of infanticide. According to Susan Friedman, "Two dozen nations have infanticide laws that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their children of up to one year of age. The United States does not have such a law, but mentally ill mothers may plead not guilty by reason of insanity."[43] In the law of the Republic of Ireland, infanticide was made a separate crime from murder in 1949, applicable for the mother of a baby under one year old where "the balance of her mind was disturbed by reason of her not having fully recovered from the effect of giving birth to the child or by reason of the effect of lactation consequent upon the birth of the child".[44] Since independence, death sentences for murder in such cases had always been commuted;[45] the new act was intended "to eliminate all the terrible ritual of the black cap and the solemn words of the judge pronouncing sentence of death in those cases ... where it is clear to the Court and to everybody, except perhaps the unfortunate accused, that the sentence will never be carried out."[46] In Russia, murder of a newborn child by the mother has been a separate crime since 1996.[47]

Unintentional

[edit]For a killing to be considered murder in nine out of fifty states in the US, there normally needs to be an element of intent. A defendant may argue that they took precautions not to kill, that the death could not have been anticipated, or was unavoidable. As a general rule, manslaughter[48] constitutes reckless killing, but manslaughter also includes criminally negligent (i.e. grossly negligent) homicide.[49] Unintentional killing that results from an involuntary action generally cannot constitute murder.[50] After examining the evidence, a judge or jury (depending on the jurisdiction) would determine whether the killing was intentional or unintentional.

Diminished capacity

[edit]In jurisdictions using the Uniform Penal Code, such as California, diminished capacity may be a defense. For example, Dan White used this defense[51] to obtain a manslaughter conviction, instead of murder, in the assassination of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk. Afterward, California amended its penal code to provide "As a matter of public policy there shall be no defense of diminished capacity, diminished responsibility, or irresistible impulse in a criminal action...."[52]

Aggravating circumstances

[edit]Murder with specified aggravating circumstances is often punished more harshly. Depending on the jurisdiction, such circumstances may include:

- Premeditation

- Poisoning

- Lying in wait

- Murder of a child

- Murder committed during sexual assault

- Murder committed during kidnapping[53]

- Multiple murders committed within one criminal transaction or in different transactions as part of one broader scheme

- Murder of a police officer,[54][55] judge, firefighter or witness to a crime[56]

- Murder of a pregnant woman[57]

- Crime committed for pay or other reward, such as contract killing[58]

- Exceptional brutality or cruelty, such as that employed in torture murder

- The use of excessive or gratuitous violence beyond that which is necessary to kill; overkill[59]

- Murder committed by an offender previously convicted of murder

- Methods which are dangerous to the public[60] e.g. explosion, arson, shooting in a crowd etc.[61]

- Murder for a political cause[54][62]

- Murder committed in order to conceal another crime or facilitate its commission.[63]

- Murder committed in order to obtain material gain, for example to obtain an inheritance[64]

- Hate crimes, which occur when a perpetrator targets a victim because of their perceived membership in a certain social group.

- Treachery (e.g. Heimtücke in German law)

In the United States and Canada, these murders are referred to as first-degree or aggravated murders.[65] Under English criminal law, murder always carries a mandatory life sentence, but is not classified into degrees. Penalties for murder committed under aggravating circumstances are often higher under English law than the 15-year minimum non-parole period that otherwise serves as a starting point for a murder committed by an adult.

Felony murder rule

[edit]A legal doctrine in some common law jurisdictions broadens the crime of murder: when an offender kills in the commission of a dangerous crime, (regardless of intent), he or she is guilty of murder. The felony murder rule is often justified by its supporters as a means of preventing dangerous felonies,[66] but the case of Ryan Holle[67] shows it can be used very widely.

The felony-murder reflects the versari in re illicita: the offender is objectively responsible for the event of the unintentional crime;[68] in fact the figure of the civil law systems corresponding to felony murder is the preterintentional homicide (art. 222-7 French penal code,[69][70][71] art. 584 Italian penal code,[72] art. 227 German penal code[73] etc.). Felony murder contrasts with the principle of guilt, for which in England it was, at least formally, abolished in 1957, in Canada it was quashed by the Supreme Court, while in the USA it continues to survive.[74][75][76]

Year-and-a-day rule

[edit]In some common law jurisdictions, a defendant accused of murder is not guilty if the victim survives for longer than one year and one day after the attack.[77] This reflects the likelihood that if the victim dies, other factors will have contributed to the cause of death, breaking the chain of causation; and also means that the responsible person does not have a charge of murder "hanging over their head indefinitely".[78] Subject to any statute of limitations, the accused could still be charged with an offense reflecting the seriousness of the initial assault.

With advances in modern medicine, most countries have abandoned a fixed time period and test causation on the facts of the case. This is known as "delayed death" and cases where this was applied or was attempted to be applied go back to at least 1966.[79]

In England and Wales, the "year-and-a-day rule" was abolished by the Law Reform (Year and a Day Rule) Act 1996. However, if death occurs three years or more after the original attack then prosecution can take place only with the attorney-general's approval.

In the United States, many jurisdictions have abolished the rule as well.[80][81] Abolition of the rule has been accomplished by enactment of statutory criminal codes, which displaced the common-law definitions of crimes and corresponding defenses. In 2001 the Supreme Court of the United States held that retroactive application of a state supreme court decision abolishing the year-and-a-day rule did not violate the Ex Post Facto Clause of Article I of the United States Constitution.[82]

The potential effect of fully abolishing the rule can be seen in the case of 74-year-old William Barnes, charged with the murder of a Philadelphia police officer Walter T. Barclay Jr., who he had shot nearly 41 years previously. Barnes had served 16 years in prison for attempting to murder Barkley, but when the policeman died on 19 August 2007, this was alleged to be from complications of the wounds suffered from the shooting – and Barnes was charged with his murder. He was acquitted on May 24, 2010.[83]

Contributing factors

[edit]Certain personality disorders are associated with an increased homicide rate, most notably narcissistic, anti-social, and histrionic personality disorders and those associated with psychopathology.[84]

Several studies have shown that there is a correlation between murder rates and poverty.[85][86][87][88] A 2000 study showed that regions of the state of São Paulo in Brazil with lower income also had higher rates of murder.[88]

Historical attitudes

[edit]

In the past, certain types of homicide were lawful and justified. Georg Oesterdiekhoff wrote:

Evans-Pritchard says about the Nuer from Sudan: "Homicide is not forbidden, and Nuer do not think it wrong to kill a man in fair fight. On the contrary, a man who slays another in combat is admired for his courage and skill." (Evans-Pritchard 1956: 195) This statement is true for most African tribes, for pre-modern Europeans, for Indigenous Australians, and for Native Americans, according to ethnographic reports from all over the world. ... Homicides rise to incredible numbers among headhunter cultures such as the Papua. When a boy is born, the father has to kill a man. He needs a name for his child and can receive it only by a man, he himself has murdered. When a man wants to marry, he must kill a man. When a man dies, his family again has to kill a man.[89]

In many such societies the redress was not via a legal system, but by blood revenge, although there might also be a form of payment that could be made instead—such as the weregild which in early Germanic society could be paid to the victim's family in lieu of their right of revenge.

One of the oldest-known prohibitions against murder appears in the Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu written sometime between 2100 and 2050 BC. The code states, "If a man commits a murder, that man must be killed." In the Abrahamic religions, the first ever murder was committed by Cain against his brother Abel out of jealousy.[90] The prohibition against murder is one of the Ten Commandments given by God to Moses in Exodus and Deuteronomy, which are part of the scripture for both Jews and Christians. In Islam according to the Qur'an, one of the greatest sins is to kill a human being who has committed no fault.[91] The term assassin derives from Hashshashin,[92] a militant Ismaili Shi'ite sect, active from the 8th to 14th centuries. This mystic secret society killed members of the Abbasid, Fatimid, Seljuq and Crusader elite for political and religious reasons.[93] The Thuggee cult that plagued India was devoted to Kali, the goddess of death and destruction.[94][95] According to some estimates the Thuggees murdered one million people between 1740 and 1840.[96] The Aztecs believed that without regular offerings of blood the sun god Huitzilopochtli would withdraw his support for them and destroy the world as they knew it.[97] According to Ross Hassig, author of Aztec Warfare, "between 10,000 and 80,400 persons" were sacrificed in the 1487 re-consecration of the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan.[98][99] Japanese samurai had the right to strike with their sword at anyone of a lower class who compromised their honour.[100]

Slavery

[edit]Southern slave codes did make willful killing of a slave illegal in most cases.[101] For example, the 1860 Mississippi case of Oliver v. State charged the defendant with murdering his own slave.[102] In 1811, the wealthy white planter Arthur Hodge was hanged for murdering several of his slaves on his plantation in the Virgin Islands.[103]

Honor killings in Corsica

[edit]In Corsica, vendetta was a social code that required Corsicans to kill anyone who wronged their family honor. Between 1821 and 1852, no fewer than 4,300 murders were perpetrated in Corsica.[104]

Abortion

[edit]Opponents of abortion consider abortion a form of murder, treating the foetus as a person.[105][106] In some countries, a foetus is a legal person who can be murdered,[note 2] and killing someone who is pregnant is considered a double homicide.[108]

Incidence

[edit]

The World Health Organization reported in October 2002 that a person is murdered every 60 seconds.[109] An estimated 520,000 people were murdered in 2000 around the globe. Another study estimated the worldwide murder rate at 456,300 in 2010 with a 35% increase since 1990.[110] Two-fifths of them were young people between the ages of 10 and 29 who were killed by other young people.[111] Because murder is the least likely crime to go unreported, statistics of murder are seen as a bellwether of overall crime rates.[112]

Historical variation

[edit]

According to scholar Pieter Spierenburg homicide rates per 100,000 in Europe have fallen over the centuries, from 35 per 100,000 in medieval times, to 20 in 1500 AD, five in 1700, to below two per 100,000 in 1900.[113]

In the United States, murder rates have been higher and have fluctuated. They fell below 2 per 100,000 by 1900, rose during the first half of the century, dropped in the years following World War II, and bottomed out at 4.0 in 1957 before rising again.[114] The rate stayed in 9 to 10 range most of the period from 1972 to 1994, before falling to 5 in present times.[113] The increase since 1957 would have been even greater if not for the significant improvements in medical techniques and emergency response times, which mean that more and more attempted homicide victims survive. According to one estimate, if the lethality levels of criminal assaults of 1964 still applied in 1993, the country would have seen the murder rate of around 26 per 100,000, almost triple the actually observed rate of 9.5 per 100,000.[115]

A similar, but less pronounced pattern has been seen in major European countries as well. The murder rate in the United Kingdom fell to 1 per 100,000 by the beginning of the 20th century and as low as 0.62 per 100,000 in 1960, and was at 1.28 per 100,000 as of 2009[update]. The murder rate in France (excluding Corsica) bottomed out after World War II at less than 0.4 per 100,000, quadrupling to 1.6 per 100,000 since then.[116]

The specific factors driving these dynamics in murder rates are complex and not universally agreed upon. Much of the raise in the U.S. murder rate during the first half of the 20th century is generally thought to be attributed to gang violence associated with Prohibition. Since most murders are committed by young males, the near simultaneous low in the murder rates of major developed countries circa 1960 can be attributed to low birth rates during the Great Depression and World War II. Causes of further moves are more controversial. Some of the more exotic factors claimed to affect murder rates include the availability of abortion[117] and the likelihood of chronic exposure to lead during childhood (due to the use of leaded paint in houses and tetraethyllead as a gasoline additive in internal combustion engines).[118]

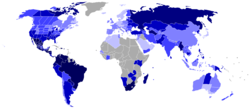

Rates by country

[edit]Murder rates vary greatly among countries and societies around the world. In the Western world, murder rates in most countries have declined significantly during the 20th century and are now between 1 and 4 cases per 100,000 people per year. Latin America and the Caribbean, the region with the highest murder rate in the world,[119] experienced more than 2.5 million murders between 2000 and 2017.[120]

Murder rates in jurisdictions such as Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Iceland, Switzerland, Italy, Spain and Germany are among the lowest in the world, around 0.3–1 cases per 100,000 people per year; the rate of the United States is among the highest of developed countries, around 4.5 in 2014,[121] with rates in larger cities sometimes over 40 per 100,000.[122] The top ten highest murder rates are in Honduras (91.6 per 100,000), El Salvador, Ivory Coast, Venezuela, Belize, Jamaica, U.S. Virgin Islands, Guatemala, Saint Kitts and Nevis and Zambia. (UNODC, 2011 – full table here).

The following absolute murder counts per-country are not comparable because they are not adjusted by each country's total population. Nonetheless, they are included here for reference, with 2010 used as the base year (they may or may not include justifiable homicide, depending on the jurisdiction). There were 52,260 murders in Brazil, consecutively elevating the record set in 2009.[123] Over half a million people were shot to death in Brazil between 1979 and 2003.[124] 33,335 murder cases were registered across India,[125] approximately 17,000 murders in Colombia (the murder rate was 38 per 100,000 people, in 2008 murders went down to 15,000),[126] approximately 16,000 murders in South Africa,[127] approximately 15,000 murders in the United States,[128] approximately 26,000 murders in Mexico,[129] about 8,000 murders committed in Russia,[130] approximately 13,000 murders in Venezuela,[131] approximately 4,000 murders in El Salvador,[132] approximately 1,400 murders in Jamaica,[133] approximately 550 murders in Canada[134] and approximately 470 murders in Trinidad and Tobago.[133] Pakistan reported 12,580 murders.[135]

United States

[edit]

In the United States, 666,160 people were killed between 1960 and 1996.[138] Approximately 90% of murders in the US are committed by males.[139] Between 1976 and 2005, 23.5% of all murder victims and 64.8% of victims murdered by intimate partners were female.[140] For women in the US, homicide is the leading cause of death in the workplace.[141]

In the US, murder is the leading cause of death for African American males aged 15 to 34. Between 1976 and 2008, African Americans were victims of 329,825 homicides.[142][143] In 2006, the Federal Bureau of Investigation's Supplementary Homicide Report indicated that nearly half of the 14,990 murder victims that year were black (7421).[144] In 2007, there were 3,221 black victims and 3,587 white victims of non-negligent homicides. While 2,905 of the black victims were killed by a black offender, 2,918 of the white victims were killed by white offenders. There were 566 white victims of black offenders and 245 black victims of white offenders.[145] The "white" category in the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) includes non-black Hispanics.[146] Murder demographics are affected by the improvement of trauma care, which has resulted in reduced lethality of violent assaults – thus the murder rate may not necessarily indicate the overall level of social violence.[115]

Workplace homicide, which tripled during the 1980s, is the fastest growing category of murder in America.[141][147][148]

Development of murder rates over time in different countries is often used by both supporters and opponents of capital punishment and gun control. Using properly filtered data, it is possible to make the case for or against either of these issues. For example, one could look at murder rates in the United States from 1950 to 2000,[149] and notice that those rates went up sharply shortly after a moratorium on death sentences was effectively imposed in the late 1960s. This fact has been used to argue that capital punishment serves as a deterrent and, as such, it is morally justified. Capital punishment opponents frequently counter that the United States has much higher murder rates than Canada and most European Union countries, although all those countries have abolished the death penalty. Overall, the global pattern is too complex, and on average, the influence of both these factors may not be significant and could be more social, economic, and cultural.

Despite the immense improvements in forensics in the past few decades, the fraction of murders solved has decreased in the United States, from 90% in 1960 to 61% in 2007.[150] Solved murder rates in major U.S. cities varied in 2007 from 36% in Boston, Massachusetts, to 76% in San Jose, California.[151] Major factors affecting the arrest rate include witness cooperation[150] and the number of people assigned to investigate the case.[151]

Investigation

[edit]The success rate of criminal investigations into murders (the clearance rate) tends to be relatively high for murder compared to other crimes, due to its seriousness. In the United States, the clearance rate was 62.6% in 2004.[152]

See also

[edit]Related lists

[edit]Related topics

[edit]- Assassination, the murder of a prominent person, such as a head of state or head of government.

- Capital murder

- Child murder

- Culpable homicide

- Depraved-heart murder

- Letting die

- Mass murder

- Misdemeanor murder

- Murder conviction without a body

- Nonkilling

- Seven laws of Noah

- Soldiers are murderers

- Stigmatized property

- Thrill killing

Laws by country

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This is "malice" in a technical legal sense, not the more usual English sense denoting an emotional state. See malice (law).

- ^ For example, in the United States, the Unborn Victims of Violence Act of 2004 recognizes a foetus as a legal victim if injured or killed during the commission of certain federal crimes. This law applies to federal jurisdictions and certain crimes but excludes legal abortions and medical treatments.[107]

References

[edit]- ^ West's Encyclopedia of American Law Volume 7 (Legal Representation to Oyez). West Group. 1997. ISBN 978-0-314-20160-7. Retrieved 10 September 2017. ("The unlawful killing of another human being without justification or excuse.")

- ^ "Murder". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary (5 ed.). Random House Publishing Group. 2012. ISBN 978-0-553-58322-9. Retrieved 10 September 2017. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the crime of killing a person with malice aforethought or with recklessness manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life.")

- ^ Tran, Mark (28 March 2011). "China and US among top punishers but death penalty in decline". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017.

- ^ See, e.g. United States: 18 USC § 1111 (death or life imprisonment for first-degree murder in the federal jurisdiction of the United States), plus numerous other penalties under state law

United Kingdom: The Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965 (c. 71) s. 1(1) (providing for life imprisonment for murder)

Canada: R.S.C. 1985, c. C-46, s. 235 (providing for life imprisonment for first-degree or second-degree murder in Canada)

Australia: Criminal Code, 1995, s. 71.2 (murder of UN personnel), plus numerous other penalties under state law

New Zealand: Section 102 of the Sentencing Act 2002 (2002 No. 9), providing for the presumption of life imprisonment for murder except where such a sentence would be manifestly unjust

India: Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita § 103(1) (death or life imprisonment mandatory for murder)

Hong Kong: Offences against the Person Ordinance (Cap. 212), § 2 (providing for the mandatory penalty of life imprisonment for murder, with exceptions for juveniles)

the Philippines: Article 248 of the Revised Penal Code. - ^ Bynon, Theodora (1977). Historical Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29188-0. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Murder" Archived 2020-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, in: Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed on 17 July 2020.

- ^ Nielson, William A.; Patch, Howard R. (1921). Selections from Chaucer. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Blackstone, William (1765). Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. Avalon Project, Yale Law School. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Book the Fourth – Chapter the Fourteenth : Of Homicide.

- ^ a b Baker, Dennis J. (2021). Treatise of criminal law (Fifth ed.). London. p. 804. ISBN 978-1-4743-2018-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f Dressler, Joshua (2001). Understanding Criminal Law (3rd ed.). Lexis. ISBN 978-0-8205-5027-5.

- ^ Dennis J. Baker (2012). "Chapter 11". Glanville Williams Textbook of Criminal Law. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ashford, Elizabeth. "Killing & Letting Die". Philosophy 4826, Life and Death. University of St. Andrews. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ R v Tait [1990] 1 QB 290.

- ^ Wise, Edward. "Criminal Law" in Introduction to the Law of the United States (Clark and Ansay, eds.), 154 Archived 2015-05-17 at the Wayback Machine (2002).

- ^ R v Crabbe [1985] HCA 22, (1985) 156 CLR 464 (26 March 1985), High Court; but the common law has been modified in NSW: Royall v R [1991] HCA 27, (1991) 172 CLR 378 (25 June 1991), High Court.

- ^ "Noticias Jurídicas".

- ^ "Ley Orgánica 1/2015, de 30 de marzo, por la que se modifica la Ley Orgánica 10/1995, de 23 de noviembre, del Código Penal". Noticias Jurídicas (in Spanish).

- ^ Murder in the First and Second Degree (14–17) A murder which shall be perpetrated by ... poison, lying in wait, imprisonment, starving, torture, or by any other kind of willful, deliberate and premeditated killing or which shall be committed in the perpetration or attempted perpetration of any arson, rape or sex offense, robbery, kidnapping, burglary, or other felony committed or attempted with the use of a deadly weapon, shall be ... murder in the first degree ... and shall be punished by death or life imprisonment ... except that any person ... under 17 years of age at the time of the murder shall be punished with imprisonment ... for life. All other kinds of murder, including that which shall be proximately caused by the unlawful distribution of opium or any synthetic or natural salt, compound, derivative, or the preparation of opium ... cause the death of the user, shall be ... murder in the second degree and ... shall be punished as a Class C felony

- ^ Brenner, Frank (1953). "The Impulsive Murder and the Degree Device". Fordham Law Review. 22 (3). Archived from the original on 13 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ "Minnesota Second-Degree Murder". findlaw.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Mosites, Jean M. (2006). "Malice Necessary to Convict for Third-Degree Murder in Pennsylvania Still Requires Wickedness of Disposition andPennsylvania Still Requires Wickedness of Disposition and Hardness of Heart:Hardness of Heart: Commonwealth v. Santos". Duquesne Law Review. 44 (3): 600.

- ^ "Premeditation". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Title 18 USC, Sec. 1111, Murder". Legal Information Institute. Cornell Law School. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Koninkrijksrelaties, Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en. "Wetboek van Strafrecht". wetten.overheid.nl.

- ^ "Blackstone, Book 4, Chapter 14". Yale.edu. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ A Dictionary of Modern Legal Usage By Bryan A. Garner, p. 545.

- ^ The French Parliament. "Article 122-5". French Criminal Law (in French). Legifrance. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Otlowski, Margaret (1997). Margaret Otlowski, Voluntary Euthanasia and the Common Law, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 175–177. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-825996-1. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "Man Kills Suspected Intruders While Protecting Neighbor's Property". ABC News. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ see Joe Horn shooting controversy

- ^ "Texas man acquitted of killing Craigslist escort". Yahoo News. 7 June 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Assembly, No. 159, State of New Jersey, 213th Legislature, The "New Jersey Self Defense Law"" (PDF). 6 May 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ^ "5". Criminal Law. University of Minnesota: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. 2015. ISBN 978-1-946135-08-7. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Introduction - Preliminary Examination of so-called honour killings in canada". 24 September 2013.

- ^ ""Honour" Killings in Yemen: Tribal Tradition and the Law - Daraj". 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Full list - Treaty Office - www.coe.int".

- ^ Joseph Goldstein (28 July 2016). "Is a Police Shooting a Crime? It Depends on the Officer's Point of View". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

The longstanding official deference to the viewpoint of police officers is enshrined in the laws of some states and Supreme Court rulings.

- ^ a b c People v. Davis, 7 Cal. 4th 797, 30 Cal. Rptr. 2d 50, 872 P.2d 591 Archived 2015-09-04 at the Wayback Machine (1994).

- ^ M'Naughten's case, [1843] All ER Rep 229.

- ^ N.Y. Penal Law, § 40.15, found at N.Y. Assembly web site, retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ "Code de la Santé Publique Chapitre III: Hospitalisation d'office Article L3213-1" (in French). Legifrance. 2002. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2007., note: this text refers to the procedure of involuntary commitment by the demand of the public authority, but the prefect systematically use that procedure whenever a man is discharged due to his dementia.

- ^ Friedman, SH. "Commentary: Postpartum Psychosis, Infanticide, and Insanity Implications for Forensic Psychiatry", J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 40:3:326-332 (September 2012).

- ^ "Infanticide Act, 1949, Section 1". Irish Statute Book. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Rattigan, Clíona (January 2008). "'Done to death by father or relatives': Irish families and infanticide cases, 1922–1950". The History of the Family. 13 (4): 370–383. doi:10.1016/j.hisfam.2008.09.003. ISSN 1081-602X. S2CID 144571256.

- ^ "Infanticide Bill, 1949—Second and Subsequent Stages". Seanad Éireann debates. 7 July 1949. Vol.36 c.1472. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ Criminal Code of Russia, art.106

- ^ The French Parliament. "Article 222-8". French Criminal Law. Legifrance. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ The French Parliament. "Section II – Involuntary Offences Against Life". French Criminal Law. Legifrance. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ Michaels, Alan C. (1985). "Defining Unintended Murder". Columbia Law Review. 85 (4): 786–811. doi:10.2307/1122334. JSTOR 1122334.

- ^ The so-called "Twinkie defense").

- ^ "2011 California Code :: Penal Code :: PART 1. OF CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS [25 - 680] :: TITLE 1. OF PERSONS LIABLE TO PUNISHMENT FOR CRIME :: Section 28". Justia Law. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Section 630:1 Capital Murder".

- ^ a b See Murder (English law).

- ^ Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) s 19B Mandatory life sentences for murder of police officers.

- ^ See Murder (United States law).

- ^ See Murder (Romanian law).

- ^ See Murder (Brazilian law).

- ^ "Domestic Homicide Sentencing Review - Publication and Interim Response". questions-statements.parliament.uk. Retrieved 2 February 2025.

- ^ Criminal Code of Russia art.105 p.2"e"

- ^ "Постановление Пленума Верховного Суда РФ от 27.01.1999 N 1 (ред. от 03.03.2015) "О судебной практике по делам об убийстве (ст. 105 УК РФ)" \ КонсультантПлюс". www.consultant.ru. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- ^ "Parole Board of Ireland". Citizens Information Board. Parole Board of Ireland. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- ^ Criminal Code of Russia art.105 p.2"k"

- ^ "2006 Utah Code - 76-5-202 — Aggravated murder".

- ^ "Classification of murder". Justice Laws Website. Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Sidak, J. Gregory (2015). "Two Economic Rationals for Felony Murder" (PDF). Cornell Law Review. 101: 51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (4 December 2007). "Serving Life for Providing Car to Killers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017.

- ^ "Hein Online". heinonline.org. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "La praeterintention" (PDF).

- ^ "Article 222-7 - Code pénal - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Journal of law".

- ^ "Art. 584 codice penale - Omicidio preterintenzionale". Brocardi.it (in Italian). Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Körperverletzung mit Todesfolge, § 227 StGB - Exkurs". Jura Online (in German). Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Reimann, Mathias; Zimmermann, Reinhard (26 March 2019). The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256552-5.

- ^ Cadoppi, Alberto (1992). Mens rea (in Italian). Utet.

- ^ Pradel, Jean (14 September 2016). Droit pénal comparé. 4e éd (in French). Editis - Interforum. ISBN 978-2-247-15085-4.

- ^ See State v. Picotte, 2003 WI 42, 261 Wis. 2d 249 (2003)[1](search for "year-and-a-day rule")

- ^ "Criminal lawyers back review of time limit for homicide charges". Radio NZ. 25 February 2017. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ Wofford, Taylor (9 August 2014). "Will John Hinckley Jr. Face Murder Charges for the 'Delayed Death' of James Brady?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "People v. Carrillo, 646 N.E.2d 582 (Ill. 1995)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "State v. Gabehart, 836 P.2d 102 (N.M. 1992)". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Rogers v. Tennessee, 532 U.S. 451 (2001).

- ^ "Shooter acquitted of murder charge in 1966 shooting of Philadelphia police officer". PA Media Group. Associated Press. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ^ Petherick, Wayne (2018). Homicide. London, United Kingdom. pp. 62–65. ISBN 978-0-12-812529-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Dong, Baomin; Egger, Peter H.; Guo, Yibei (18 May 2020). "Is poverty the mother of crime? Evidence from homicide rates in China". PLOS ONE. 15 (5) e0233034. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1533034D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233034. PMC 7234816. PMID 32422646.

- ^ Bailey, William C. (November 1984). "Poverty, Inequality, and City Homicide Rates. Some Not So Unexpected Findings". Criminology. 22 (4): 531–550. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1984.tb00314.x.

- ^ Suhail, Kausar; Javed, Fareha (Winter 2004). "Psychosocial causes of the crime of murder in Pakistan". Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research: 161–174. ProQuest 89070703.

- ^ a b Barata, Rita Barradas; Ribeiro, Manoel Carlos Sampaio de Almeida (February 2000). "Relação entre homicídios e indicadores econômicos em São Paulo, Brasil, 1996" [Correlation between homicide rates and economic indicators in São Paulo, Brazil, 1996]. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública (in Portuguese). 7 (2): 118–124. doi:10.1590/s1020-49892000000200008. PMID 10748663.

- ^ Oesterdiekhoff, Georg (2011). The Steps of Man Towards Civilization. BoD – Books on Demand. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-3-8423-4288-0.

- ^ Schimmel, Solomon (2008). "Envy in Jewish Thought and Literature". Envy. pp. 17–38. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195327953.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-532795-3.

- ^ Shah, Sayed Sikandar (January 1999). "Homicide in Islam: Major Legal Themes". Arab Law Quarterly. 14 (2). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 159–168. doi:10.1163/026805599125826381. JSTOR 3382001.

- ^ American Speech – McCarthy, Kevin M.. Volume 48, pp. 77–83

- ^ Bradley, Michael (2005). The Secret Societies Handbook. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-84403-416-1.[page needed]

- ^ Rushby, Kevin (11 June 2005). "Review: Thug by Mike Dash". The Guardian.

- ^ "Thuggee (Thagi) (13th C. to ca. 1838)". Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Rubinstein, W. D. (2004). Genocide: A History. Pearson Longman. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- ^ "Science and Anthropology". Cdis.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Hassig, Ross (13 March 2017). "El sacrificio y las guerras floridas" [Sacrifice and flowery wars]. Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish).

- ^ Harner, Michael (April 1977). "The Enigma of Aztec Sacrifice". Natural History. 86 (4): 46–51.

- ^ Mako Taniguchi, Kiri-sute Gomen, Yamakawa, 2005

- ^ Morris, Thomas D. (1996). Southern Slavery and the Law, 1619-1860. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-8078-4817-3.

- ^ Fede, Andrew (2012). People Without Rights. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-136-71610-2.

- ^ "A report of the trial of Arthur Hodge, Esquire, (late one of the members of His Majesty's Council for the Virgin-Islands) at the island of Tortola, on the 25th April, 1811, and adjourned to the 29th of the same month, for the murder of his Negro man slave named Prosper". Library of Congress. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "Wanderings in Corsica: Its History and Its Heroes Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine". Ferdinand Gregorovius (1855). p.196.

- ^ Marquis, Don. "An Argument That Abortion Is Wrong". web.csulb.edu.

- ^ Stoltzfus, Abby (6 November 2019). "Crossfire: Abortion should be illegal". Daily American. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019.

- ^ "UNBORN VICTIMS OF VIOLENCE ACT OF 2004" (PDF).

- ^ "Is killing a pregnant woman a case of double homicide?". The Star. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Holguin, Jaime (3 October 2002). "A Murder A Minute". CBS News. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ^ Albrecht, Harro (7 February 2013). "Woran wir sterben" [What we die of]. Zeit (in German).

- ^ "WHO: 1.6 million die in violence annually". Online.sfsu.edu. 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 11 June 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ Rubin, Joel (26 December 2010). "Killing in L.A. drops to 1967 levels". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 January 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ^ a b Spierenburg, Pieter, A History of Murder: Personal Violence in Europe from the Middle Ages to the Present, Polity, 2008. Referred to in "Rap Sheet Why is American history so murderous?" Archived 2010-01-09 at the Wayback Machine by Jill Lepore New Yorker, November 9, 2009

- ^ "US murder rate by year, 1900–2010". Democratic Underground. 16 December 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Harris, Anthony R.; Stephen H. Thomas; Gene A. Fisher; David J. Hirsch (May 2002). "Murder and medicine: the lethality of criminal assault 1960–1999". Homicide Studies. 6 (2): 128–166. doi:10.1177/1088767902006002003.

- ^ Randolph Roth (October 2009). "American Homicide Supplemental Volume (AHSV), European Homicides (EH)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2010.

- ^ "Freakonomics", Steven D. Levitt, Stephen J. Dubner, 2005, ISBN 0-06-073132-X

- ^ Drum, Kevin (11 February 2016). "Lead: America's Real Criminal Element". Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 11 August 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ "Violent crime has undermined democracy in Latin America". Financial Times. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "Latin America Is the Murder Capital of the World". The Wall Street Journal. 20 September 2018. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ^ "2014 Crime in the United States". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017. Table 1, Crime in the United States by Volume and Rate per 100,000 Inhabitants, 1995–2014

- ^ "Crime Rates for Selected Large Cities, 2005". Infoplease. Sandbox Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Óbitos por Causas Externas 1996 a 2010" (in Portuguese). DATASUS. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Kingstone, Steve (27 June 2005). "UN highlights Brazil gun crisis". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ "Crime in India 2010" (PDF). National Crime Records Bureau. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Homicidio 2010" (PDF) (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ "Murder in RSA for April to March 2003/2004 to 2010/2011" (PDF). South African Police Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Crime in the United States by Volume and Rate per 100,000 Inhabitants, 1991–2010". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Estadísticas de Mortalidad" (in Spanish). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ "Information on the death of the population of causes of death in the Russian Federation". Rosstat. Archived from the original on 17 January 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ "Derecho a la seguridad ciudadana" (PDF) (in Spanish). Programa Venezolano de Educación-Acción en Derechos Humanos. p. 397. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ "Homicidios en Centroamérica" (PDF) (in Spanish). La Prensa Grafica de El Salvador. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- ^ a b "Global Study on Homicide" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. p. 95. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ "Police-reported crime for selected offences, Canada, 2009 and 2010". Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ^ "State of Human Rights in 2010" (PDF). Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. p. 98. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ^ Serena, Katie (9 January 2019). "The Lake Bodom Murders: Finland's Most Famous Unsolved Triple Homicide". Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- ^ "BRAZIL: Youth Still in Trouble, Despite Plethora of Social Programmes Archived 2013-10-29 at the Wayback Machine". IPS. March 30, 2007.

- ^ "Twentieth Century Atlas – Homicide". Users.erols.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ "What Motivates Some Women to Kill". ABC News. 13 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Violence Against Women". Office on Violence Against Women. U.S. Department of Justice. 2 December 2016. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Promising Victim-Related Practices in Probation and Parole". Office for Victims of Crime. U.S. Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017. Chapter 6, Responding to Workplace Violence and Staff Victimization.

- ^ "Homicide trends in the United States" (PDF). Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2011.

- ^ "Homicide Victims by Race and Sex". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 23 March 2012.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Victimology and Crime Prevention Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine". Bonnie S. Fisher, Steven P. Lab (2010). p. 706. ISBN 1-4129-6047-9

- ^ Ann L. Pastore; Kathleen Maguire (eds.). Sourcebook of criminal justice statistics Online (PDF) (31st ed.). Albany, New York: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2010.

- ^ "Race and crime: a biosocial analysis Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine". Anthony Walsh (2004). Nova Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 1-59033-970-3

- ^ Csiernik, Rick, ed. (2014). Workplace Wellness: Issues and Responses. Brown Bear Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-55130-571-4.

- ^ thejtal (September 2021). "What is Workplace Violence? - TAL Global". Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Christopher Effgen (11 September 2001). "Disaster Center web site". Disastercenter.com. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ^ a b Beale, Lewis (20 May 2009). "Why Fewer Murder Cases Get Solved These Days". PacificStandard. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ a b Whitley, Brian (24 December 2008). "Why fewer murder cases get solved". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ "Crime in the United States 2004". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 15 August 2025. Table 3.1, Crimes Cleared by Arrest

Bibliography

[edit]- Lord Mustill on the Common Law concerning murder

- Sir Edward Coke Co. Inst., Pt. III, ch.7, p. 50

External links

[edit]- Introduction and Updated Information on the Seville Statement on Violence

- The Seville Statement

- Atlas of United States Mortality – U.S. Centers for Disease Control

- Cezanne's depiction of "The Murder" – National Museums Liverpool

Murder

View on GrokipediaEmpirical data reveal murder as a persistent but variably distributed phenomenon, with approximately 458,000 intentional homicides recorded globally in 2021, yielding an average rate of about 6 per 100,000 population, though regional disparities persist—highest in Latin America and Africa, lowest in Europe and Asia.[4] Long-term historical trends indicate a marked decline in per capita rates over centuries, from dozens per 100,000 in medieval Europe to under 1 in modern developed nations, attributable to state monopolization of force, commerce expansion, and cultural shifts toward self-control rather than feuding.[5] Causally, most murders stem from interpersonal conflicts, organized crime, or domestic disputes, frequently exacerbated by substance intoxication impairing rational restraint, though socioeconomic factors like inequality and weak institutions amplify prevalence in high-risk areas.[4] Prevention efforts emphasize deterrence through swift justice, community interventions targeting at-risk youth, and addressing root impulsivity via education and policing, yielding measurable reductions where implemented rigorously.[6] Controversies arise in classification, such as debates over fetal personhood or self-defense thresholds, and in data reliability, where underreporting in corrupt regimes skews global estimates.[7]

Etymology and Conceptual Foundations

Linguistic Origins

The English term "murder" derives from Old English morþor (also spelled morthor), denoting secret or unlawful killing, a usage attested in texts from the Anglo-Saxon period.[8] This noun traces to Proto-Germanic *murþrą, meaning "murder" or "killing with a weapon," which itself stems from Proto-Indo-European *mr̥trom, a formation related to the root *mer- signifying "to die" or "to harm by rubbing away."[8] The connotation of secrecy distinguished morþor from other Germanic terms for killing, such as open slaying or battle death, reflecting early linguistic emphasis on premeditated or concealed intent.[8] Following the Norman Conquest in 1066, the word evolved through Middle English as murther or murþre, influenced partly by Old French murdrer (itself of Germanic origin), leading to the modern spelling "murder" by the 14th century.[9] The verb form, meaning "to kill unlawfully," appears in records as early as circa 1175 in the Ormulum, an early Middle English text, indicating its established use in legal and moral contexts by that time.[10] Cognates persist in other Germanic languages, including German Mord, Dutch moord, and Old Norse morð ("secret slaughter"), underscoring a shared Indo-European heritage focused on culpable homicide rather than justifiable or accidental death.[8] Semantically, the term's development highlights a persistent legal-linguistic boundary: in early English law, "murder" implied not just killing but malice or stealth, contrasting with manslaughter (from Old English man-slaghter, "man-killing"), which denoted impulsive or excusable acts. This distinction, rooted in Germanic customary law, influenced subsequent statutory definitions, where "murder" required proof of intent beyond mere homicide.[8]Philosophical Underpinnings of Unlawful Killing

The philosophical foundations of unlawful killing, commonly termed murder, rest on the recognition of human life as possessing intrinsic value, prohibiting its intentional termination without moral or legal justification. In natural law theory, as articulated by Thomas Aquinas, murder violates the eternal law imprinted in human nature, which inclines individuals toward self-preservation and the common good; thus, private individuals lack authority to execute death, reserving such power for public authority in cases of justice.[11] This framework posits that unlawful killing disrupts the divinely ordered hierarchy, equating it to a grave sin against charity and natural inclination.[11] Enlightenment thinkers advanced secular rationales through natural rights and social contract doctrines. John Locke contended that in the state of nature, individuals possess an inalienable right to life, derived from God's endowment, rendering arbitrary destruction of another's life unjustifiable; no person can consent to or authorize such deprivation, as it exceeds natural powers.[12] Similarly, Thomas Hobbes described the pre-contractual state as one of mutual threat and violence, where life is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" due to unchecked killings; the social contract transfers the right to enforce peace to a sovereign, making private unlawful killings a breach that reverts society to anarchy.[13] Deontological ethics, exemplified by Immanuel Kant, grounds the prohibition in the categorical imperative, which forbids treating rational beings as mere means to ends; intentional killing of the innocent fails the universalizability test, as a maxim permitting such acts undermines humanity's autonomy and dignity.[14] Kant allowed exceptions like self-defense or retributive punishment by the state, but emphasized that murder's wrongness inheres in its violation of persons' intrinsic worth, independent of consequences.[15] These traditions collectively underpin the moral consensus that unlawful killing lacks the justifying intent or circumstance—such as defense or societal protection—distinguishing it from permissible homicide, prioritizing causal preservation of life over subjective utilities or relativistic permissions.[16]Legal Definitions and Classifications

Core Elements Across Jurisdictions

Across legal jurisdictions, murder is distinguished from other forms of homicide by the presence of specific core elements: an unlawful act or omission causing the death of a human being, accompanied by a culpable mental state, with the act serving as the factual and proximate cause of the harm. These elements ensure that liability attaches only to killings lacking legal justification, such as self-defense or lawful execution, and require proof that the victim was a living person at the time of the fatal act—typically excluding prenatal deaths unless statute specifies otherwise, as in some U.S. states under fetal homicide laws enacted post-2004 Unborn Victims of Violence Act.[2][3][17] The actus reus, or guilty act, universally demands a voluntary conduct—affirmative action or culpable omission—that results in death, excluding involuntary acts like reflexes or automatism. For instance, in common law systems derived from English precedent, this includes any corporeal act accelerating death, even if the victim was already mortally wounded, provided the defendant's intervention hastens the end. Civil law traditions, prevalent in countries like France and Germany, similarly require a causal link via the perpetrator's behavior, but emphasize codified delicts over judge-made expansions, with omissions prosecutable only under duty-to-act statutes, such as parental neglect leading to child death. Causation bifurcates into factual ("but-for" the act, death would not occur) and legal (no superseding intervening cause breaks the chain), a requirement applied rigorously to avoid overreach, as seen in cases where medical intervention post-assault absolves if it independently causes death.[2][17][18] The mens rea, or guilty mind, forms the crux differentiating murder from manslaughter or excusable homicide, demanding proof of intent or equivalent culpability. In common law jurisdictions like the United States and United Kingdom, "malice aforethought" encapsulates four forms: (1) intent to kill; (2) intent to cause grievous bodily harm likely to kill; (3) extreme recklessness showing depraved indifference to human life; or (4) intent to commit an inherently dangerous felony, as codified in U.S. federal law under 18 U.S.C. § 1111, which mandates premeditation for first-degree murder punishable by life or death. Civil law systems, by contrast, hinge on dolus (intent), with direct intent (purposeful killing) or indirect intent (certainty or practical certainty of death), but reserve "murder" for aggravated intentional homicides—e.g., German § 211 StGB requires base motives like greed or cruelty, absent which it constitutes lesser Totschlag under § 212. This intent threshold aligns with international criminal law precedents, where murder within crimes against humanity demands knowledge of death as a probable outcome, as affirmed in ICTY rulings on willful killing.[2][3][19] Concurrence mandates that mens rea exist at the moment of actus reus, preventing retroactive guilt attribution, while the harm element specifies death as the outcome, verified medically—e.g., brain death criteria under U.S. Uniform Determination of Death Act (1981). Jurisdictional variances persist, such as broader felony-murder doctrines in U.S. states versus narrower agency theories in England post-R v. Jogee (2016), yet these cores underpin global prohibitions, evidenced by near-universal ratification of ICCPR Article 6 barring arbitrary deprivation of life, with murder prosecutions reflecting empirical deterrence data showing intent-based convictions reduce recidivism by 20-30% in longitudinal studies.[17][18][19]Degrees and Distinctions

In common law jurisdictions, particularly in the United States, murder is differentiated into degrees primarily based on the perpetrator's mental state, with first-degree murder requiring premeditation and deliberation, signifying a calculated intent to kill. This classification, codified in statutes like 18 U.S.C. § 1111, distinguishes first-degree murder as an unlawful killing with malice aforethought involving willful, deliberate, malicious, and premeditated action, often punishable by death or life imprisonment without parole.[2] Premeditation need not span extended periods; courts have upheld findings of first-degree murder where reflection occurred in seconds, as in cases involving prior threats or procurement of weapons.[3] Second-degree murder encompasses intentional killings lacking premeditation or those demonstrating extreme recklessness akin to implied malice, such as acts showing depraved indifference to human life. Unlike first-degree, it does not necessitate prior planning, focusing instead on the immediate intent or foreseeable deadly outcome during the act, with penalties typically ranging from 15 years to life, depending on jurisdiction.[20] [21] Some states recognize third-degree murder for killings during dangerous felonies not elevating to first-degree or for egregious recklessness without intent, bridging murder and manslaughter but still requiring malice over mere negligence.[22] The core distinction from manslaughter hinges on the presence of malice aforethought, absent in manslaughter which involves lesser culpability: voluntary manslaughter arises from sudden provocation negating deliberation, like adequate provocation reducing murder to manslaughter if rage prevents cooling off, while involuntary manslaughter stems from criminal negligence or unlawful acts risking death without intent. Empirical analyses confirm premeditation as a behavioral differentiator, with murder cases showing higher planning indicators than manslaughter, though provocation intensity varies judicially.[3] [23] [24] These gradations reflect causal culpability, as premeditated acts demonstrate greater foresight of harm, justifying harsher sanctions to deter deliberate violence.[25] Jurisdictional variations persist; for instance, not all U.S. states employ degrees, opting instead for broad murder statutes with sentencing discretion, while English law eschews degrees for murder, imposing mandatory life sentences but allowing manslaughter convictions on provocation or diminished responsibility grounds.[26]Felony Murder and Accessory Rules