Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Separation of powers

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

|

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state power (usually law-making, adjudication, and execution) and requires these operations of government to be conceptually and institutionally distinguishable and articulated, thereby maintaining the integrity of each.[1] To put this model into practice, government is divided into structurally independent branches to perform various functions[2] (most often a legislature, a judiciary and an administration, sometimes known as the trias politica). When each function is allocated strictly to one branch, a government is described as having a high degree of separation; whereas, when one person or branch plays a significant part in the exercise of more than one function, this represents a fusion of powers. When one branch holds unlimited state power and delegates its powers to other organs as it sees fit, as is the case in communist states, that is called unified power.

History

[edit]| Part of the Politics series on |

| Republicanism |

|---|

|

|

Antiquity

[edit]Polybius (Histories, Book 6, 11–13) described the Roman Republic as a mixed government ruled by the Roman Senate, Consuls and the Assemblies. Polybius explained the system of checks and balances in detail, crediting Lycurgus of Sparta with the first government of this kind.[3]

Tripartite system

[edit]During the English Civil War, the parliamentarians viewed the English system of government as composed of three branches – the King, the House of Lords and the House of Commons – where the first should have executive powers only, and the latter two legislative powers. One of the first documents proposing a tripartite system of separation of powers was the Instrument of Government, written by the English general John Lambert in 1653, and soon adopted as the constitution of England for few years during The Protectorate. The system comprised a legislative branch (the Parliament) and two executive branches, the English Council of State and the Lord Protector, all being elected (though the Lord Protector was elected for life) and having checks upon each other.[4]

A further development in English thought was the idea that the judicial powers should be separated from the executive branch. This followed the use of the juridical system by the Crown to prosecute opposition leaders following the Restoration, in the late years of Charles II and during the short reign of James II (namely, during the 1680s).[5]

John Locke's legislative, executive, and federative powers

[edit]

An earlier forerunner to Montesquieu's tripartite system was articulated by John Locke in his work Two Treatises of Government (1690).[6] In the Two Treatises, Locke distinguished between legislative, executive, and federative power. Locke defined legislative power as having "the right to direct how the force of the commonwealth shall be employed" (Second Treatise, § 143), while executive power entailed the "execution of the laws that are made, and remain in force" (Second Treatise, § 144). Locke further distinguished federative power, which entailed "the power of war and peace, leagues and alliances, and all transactions with all persons and communities without [outside] the commonwealth" (Second Treatise, § 145), or what is now known as foreign policy. Locke distinguishes between separate powers but not discretely separate institutions, and notes that one body or person can share in two or more of the powers.[7] For instance, Locke noted that while the executive and federative powers are different, they are often combined in a single institution (Second Treatise, § 148).

Locke believed that the legislative power was supreme over the executive and federative powers, which are subordinate.[8] Locke reasoned that the legislative was supreme because it has law-giving authority; "[F]or what can give laws to another, must need to be superior to him" (Second Treatise, § 150). According to Locke, legislative power derives its authority from the people, who have the right to make and unmake the legislature. He argues that once people consent to be governed by laws, only those representatives they have chosen can create laws on their behalf, and they are bound solely by laws enacted by these representatives.[9]

Locke maintained that there are restrictions on the legislative power. Locke says that the legislature cannot govern arbitrarily, cannot levy taxes, or confiscate property without the consent of the governed (cf. "No taxation without representation"), and cannot transfer its law-making powers to another body, known as the nondelegation doctrine (Second Treatise, § 142).

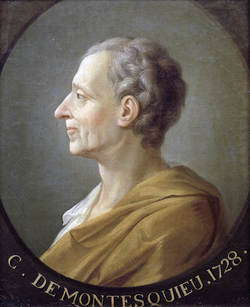

Montesquieu's separation of powers system

[edit]

The term "tripartite system" is commonly ascribed to French Enlightenment political philosopher Montesquieu, although he did not use such a term but referred to the "distribution" of powers. In The Spirit of Law (1748),[10] Montesquieu described the various forms of distribution of political power among a legislature, an executive, and a judiciary. Montesquieu's approach was to present and defend a form of government whose powers were not excessively centralized in a single monarch or similar ruler (a form known then as "aristocracy"). He based this model on the Constitution of the Roman Republic and the British constitutional system. Montesquieu took the view that the Roman Republic had powers separated so that no one could usurp complete power.[11][12][13] In the British constitutional system, Montesquieu discerned a separation of powers among the monarch, Parliament, and the courts of law.[14]

In every government there are three sorts of power: the legislative; the executive in respect to things dependent on the law of nations; and the executive in regard to matters that depend on the civil law.

By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws and amends or abrogates those that have been already enacted. By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies, establishes public security, and provides against invasions. By the third, he punishes criminals or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other simply the executive power of the state.

Montesquieu argues that each Power should only exercise its own functions. He was quite explicit here:[15]

When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty; because apprehensions may arise, lest the same monarch or senate should enact tyrannical laws, to execute them in a tyrannical manner.

Again, there is no liberty, if the judiciary power is not separated from the legislative and executive. Were it joined with the legislative, the life and liberty of the subject would be exposed to arbitrary control; for the judge would be then the legislator. Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression.

There would be an end to everything, were the same man or the same body, whether of the nobles or of the people, to exercise those three powers, that of enacting laws, executing the public resolutions, and trying the causes of individuals.

Separation of powers requires a different source of legitimization, or a different act of legitimization from the same source, for each of the separate powers. If the legislative branch appoints the executive and judicial powers, as Montesquieu indicated, there will be no separation or division of its powers, since the power to appoint carries with it the power to revoke.[16]

The executive power ought to be in the hands of a monarch, because this branch of government, having need of despatch, is better administered by one than by many: on the other hand, whatever depends on the legislative power is oftentimes better regulated by many than by a single person.

But if there were no monarch, and the executive power should be committed to a certain number of persons selected from the legislative body, there would be an end then of liberty; by reason, the two powers would be united, as the same persons would sometimes possess, and would be always able to possess, a share in both.

Checks and balances

[edit]In most modern constitutions, the separation of powers doctrine is modified by the notion of moderate, balanced government or "checks and balances"[17] – a distinct idea that was developed from the ancient theory of mixed government.[18] Since the two concepts developed alongside each other,[19] they have been closely associated, even though they are in conflict to some extent.[20] Further, constitutional provisions – notably those of the United States Constitution[21] – may reflect compromises between the two principles,[22] leading the terms "separation of powers" and "checks and balances" to become shorthand for the institutional distribution of legal authority under a specific constitution. They are at times even used interchangeably.

A government with checks and balances comprises more than one institution (often called a "branch" or "a power") exercising state power, and intends for each institution to have some influence over the other (interdependence). One institution may then "check" the other, or hinder it from using its power to pursue its ends – such as by declaring one of its actions a legal nullity or by questioning and removing one of its officers from their position. For instance, many parliaments consist of two houses; both of which are required to pass a bill before it becomes a law. A system of checks and balances also requires a balance of power between the institutions, so that the goals and actions of one are not completely determined by the other (independence); if both institutions were always in agreement by dint of one dominating the other, they would never challenge each other.

In a democratic state, where all government institutions are constituted by popular elections or through appointment by an elected body, disagreement between institutions may arise from conflicting institutional identities, fostered by differing internal power structures, decision-making processes or appointment procedures.[23] To continue the example of a bicameral parliament, members of the upper house of the United States Congress are each elected by the entire people of one federal state; whereas each member of its lower house is elected by their electoral district, a smaller and more localized constituency. A member representing a larger and more diverse base may require a broader coalition, composed of people with opposing interests, to win election, and is thus incentivized to moderate their stance; and vice versa.

One branch's efforts to prevent another branch from becoming supreme are thought to perpetually hinder any branch from imposing unduly severe measures on the governed. Immanuel Kant took this view, saying that "the problem of setting up a state can be solved even by a nation of devils,"[24] so long as they possess an appropriate constitution to pit opposing factions against each other.

Checks and balances are designed to maintain the system of separation of powers keeping each branch in its place. The idea is that it is not enough to separate the powers and guarantee their independence but the branches need to have the constitutional means to defend their own legitimate powers from the encroachments of the other branches.[25] Under this influence it was implemented in 1787 in the Constitution of the United States separation of powers. In Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton, citing Montesquieu, redefined the judiciary as a separately distinct branch of government with the legislative and the executive branches.[26][27] Before Hamilton, many colonists in the American colonies had adhered to British political ideas and conceived of government as divided into executive and legislative branches (with judges operating as appendages of the executive branch).[26]

James Madison wrote about checks (and balances) in Federalist No. 51:[28]

If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government that is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.

A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control of the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other and that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the State.

Thomas Paine wrote about balances in Common Sense:[29]

Some writers have explained the English Constitution thus: the king, say they, is one, the people another; the peers are a house in behalf of the king, the Commons in behalf of the people; but this hath all the distinctions of a house divided against itself; and though the expressions be pleasantly arranged, yet when examined they appear idle and ambiguous [...] for as the greater weight will always carry up the less, and as all the wheels of a machine are put in motion by one, it only remains to know which power in the constitution has the most weight, for that will govern: and though the others [may] check the rapidity of its motion, yet so long as they cannot stop it, their endeavours will be ineffectual: The first moving power will at last have its way, and what it wants in speed is supplied by time.

Importantly, Thomas Paine rejected the theory that English liberty was secured by constitutionally guaranteed checks and balances. Denouncing the whole notion of checks and balances, at least as far as the English constitution was concerned, Paine articulated the case for republican virtue as follows:[30]

[T]he plain truth is that it is wholly owing to the constitution of the people and not to the constitution of the government that the crown is not as oppressive in England as in Turkey.

Theories of division of state power

[edit]There are different theories about how to differentiate the functions of the state (or types of government power), so that they may be distributed among multiple structures of government (usually called branches of government, or arms).[31] There are analytical theories that provide a conceptual lens through which to understand the separation of powers as realized in real-world governments (developed by the academic discipline of comparative government); there are also normative theories,[32] both of political philosophy and constitutional law, meant to propose a reasoned (not conventional or arbitrary) way to separate powers. Disagreement arises between various normative theories in particular about what is the (desirable, in the case of political philosophy, or prescribed, in the case of legal studies) allocation of functions to specific governing bodies or branches of government.[33] How to correctly or usefully delineate and define the 'state functions' is another major bone of contention.[34]

Legislation

[edit]The legislative function of the government broadly consists of authoritatively issuing binding rules.

Adjudication

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

The function of adjudication (judicial function) is the binding application of legal rules to a particular case, which usually involves creatively interpreting and developing these rules.

Execution

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

The executive function of government includes many exercises of powers in fact, whether in carrying into effect legal decisions or affecting the real world on its own initiative.

Additional types

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

Adjudicating constitutional disputes is sometimes conceptually distinguished from other types of power, because applying the often unusually indeterminate provisions of constitutions tends to call for exceptional methods to come to reasoned decisions. Administration is sometimes proposed as a hybrid function, combining aspects of the three other functions; opponents of this view conceive of the actions of administrative agencies as consisting of the three established functions being exercised next to each other merely in fact. Supervision and integrity-assuring activities (e.g., supervision of elections), as well as mediating functions (pouvoir neutre), are also in some instances regarded as their own type, rather than a subset or combination of other types. For instance, Sweden has four powers, judicial, executive, legislative and administrative branches.

One example of a country with more than 3 branches is Taiwan, which uses a five-branch system. This system consists of the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Control Yuan, and Examination Yuan.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citation footnotes

[edit]- ^ Waldron 2013, pp. 457–458.

- ^ Waldron 2013, pp. 459–460.

- ^ Polibius. (~150 B.C.). The Rise of the Roman Empire. Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert (1979). Penguin Classics. London, England.

- ^ Vile, Maurice J. C. (April 2008). "The separation of powers". In Greene, Jack P.; Pole, J. R. (eds.). A companion to the American Revolution. Wiley (Blackwell imprint). pp. 686–690. doi:10.1002/9780470756454.ch87. ISBN 978-0-470-75644-7.

- ^ Marshall J. (2013). Whig Thought and the Revolution of 1688–91. In: Harris, T., & Taylor, S. (Eds.). (2015). The final crisis of the Stuart monarchy: the revolutions of 1688–91 in their British, Atlantic and European contexts, Chapter 3. Boydell & Brewer.

- ^ Kurland 1986, p. 595.

- ^ Tuckness, Alex (2002). "Institutional Roles, Legislative View". Locke and the Legislative Point of View: Toleration, Contested Principles, and the Law. Princeton University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0691095043.

- ^ Tuckness, Locke and the Legislative Point of View: Toleration, Contested Principles, and the Law, at p. 126

- ^ Locke, John (1824). Two Treatises of Government. C. and J. Rivington. p. 215.

- ^ "Esprit des lois (1777)/L11/C6 - Wikisource". fr.wikisource.org (in French). Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Price, Sara (22 February 2011), The Roman Republic in Montesquieu and Rousseau – Abstract, SSRN 1766947

- ^ Schindler, Ronald, Montesquieu's Political Writings, archived from the original on 12 October 2013, retrieved 19 November 2012

- ^ Lloyd, Marshall Davies (22 September 1998), Polybius and the Founding Fathers: the separation of powers, retrieved 17 November 2012

- ^ Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws, trans. by Thomas Nugent, revised ed. (New York: Colonial Press, 1899), Book 11, s. 6, pp. 151–162 at 151.

- ^ Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws, at pp. 151–52.

- ^ Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws, at p. 156.

- ^ For the case of the United States constitution: Kurland 1986, p. 593

- ^ Vile 1967, p. 18.

- ^ Vile 1967, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Vile 1967, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Vile 1967, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Vile 1967, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Magill 2000, pp. 1170–72.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (1971). "Perpetual Peace". In Reiss, Hans (ed.). Political Writings. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–13. ISBN 9781107268364.

- ^ "The Federalist No 48". Avalon Project. Yale University. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ a b Wood, Gordon S. (2018). "Comment". In Scalia, Antonin (ed.). A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 49–64. doi:10.2307/j.ctvbj7jxv.6. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ The Strengths of the Weakest Arm. Australian Bar Association Conference. Florence, Italy. 2 July 2004. Archived from the original on 22 August 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ James, Madison. "Federalist No. 51". The Avalon Project. Yale University. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ Paine, Thomas (1776). "Republican Government: On the Origin and Design of Government in General, With Concise Remarks on the English Constitution". Common Sense.

- ^ Kuklick, Bruce (2018). Thomas Paine. Taylor & Francis.

- ^ Möllers 2019, p. 239: "The modern theory of separated powers [...] addresses the necessary or possible relations between [institutional] actors and their normative ‘functions’. Legislation, execution of laws and adjudication are ‘functions’ that the states or other public authorities fulfil and that are carried out by respective ‘branches’. In this context, the notion of ‘function’ refers to different types of legally relevant actions."

- ^ On this distinction, see Möllers 2019, p. 231.

- ^ Möllers 2019, p. 234.

- ^ Möllers 2019, p. 240.

Works cited

[edit]- Barber, Nicholas W. (March 2001). "Prelude to the Separation of Powers". The Cambridge Law Journal. 60 (1): 59–88. doi:10.1017/S0008197301000629. JSTOR 4508751.

- Gwyn, William B. (1965). The Meaning of the Separation of Powers. An Analysis of the Doctrine from its Origin to the Adoption of the United States Constitution. Tulane Studies in Political Science. Vol. IX. New Orleans/The Hague: Tulane University Press/Martinus Nijhoff. OCLC 174573519.

- Kurland, Philip B. (December 1986). "The Rise and Fall of the 'Doctrine' of Separation of Powers". Michigan Law Review. 85 (3): 592–613. doi:10.2307/1288758. JSTOR 1288758.

- Magill, M. Elizabeth (2000). "The Real Separation in Separation of Powers Law". Virginia Law Review. 86 (6): 1127–1198. JSTOR 1073943. SSRN 224797.

- Möllers, Christoph [in German] (2013). The Three Branches: A Comparative Model of Separation of Powers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198738084. OCLC 818450015.

- Möllers, Christoph (September 2019). "Separation of Powers (ch. 9)". In Masterman, Roger; Schütze, Robert (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Comparative Constitutional Law. Cambridge Companions to Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230‒257. doi:10.1017/9781316716731. ISBN 978-1-107-16781-0. OCLC 1099539425.

- Sandro, Paolo (2022). The Making of Constitutional Democracy: From Creation to Application of Law. Law and Practical Reason. Vol. 13. Oxford: Bloomsbury (Hart imprint). doi:10.5040/9781509905249. ISBN 978-1-50990-524-9. OCLC 1274231156. OAPEN 20.500.12657/74777.

- Vile, Maurice J. C. (1967). Constitutionalism and the Separation of Powers. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 390050.

- Waldron, Jeremy (28 March 2013). "Separation of Powers in Thought and Practice?". Boston College Law Review. 54 (2): 433–468.

Further reading

[edit]- Peter Barenboim, Biblical Roots of Separation of Powers, Moscow, Letny Sad, 2005. ISBN 5-94381-123-0, Permalink: LC Catalog - Item Information (Full Record)

- Biancamaria Fontana (ed.), The Invention of the Modern Republic (2007) ISBN 978-0-521-03376-3

- Bernard Manin, Principles of Representative Government (1995; English version 1997) ISBN 0-521-45258-9 (hbk), ISBN 0-521-45891-9 (pbk)

- José María Maravall and Adam Przeworski (eds), Democracy and the Rule of Law (2003) ISBN 0-521-82559-8 (hbk), ISBN 0-521-53266-3 (pbk)

- Paul A. Rahe, Montesquieu and the Logic of Liberty (2009) ISBN 978-0-300-14125-2 (hbk), ISBN 978-0-300-16808-2 (pbk)

- Iain Stewart, "Men of Class: Aristotle, Montesquieu and Dicey on 'Separation of Powers' and 'the Rule of Law'" 4 Macquarie Law Journal 187 (2004)

- Iain Stewart, "Montesquieu in England: his 'Notes on England', with Commentary and Translation" (2002)

- Alec Stone Sweet, Governing with Judges: Constitutional Politics in Europe (2000) ISBN 978-0-19-829730-7

- Evan C. Zoldan, Is the Federal Judiciary Independent of Congress?, 70 Stan. L. Rev. Online 135 (2018).