Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Homeobox

View on Wikipedia

| Homeodomain | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

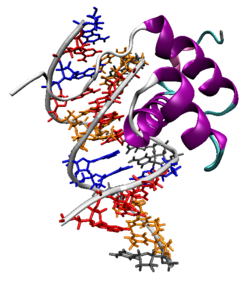

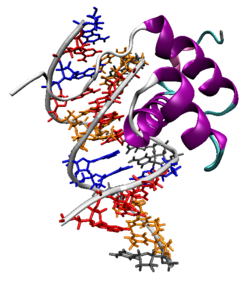

The Antennapedia homeodomain protein from Drosophila melanogaster bound to a fragment of DNA.[1] The recognition helix and unstructured N-terminus are bound in the major and minor grooves respectively. | |||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||

| Symbol | Homeodomain | ||||||||||

| Pfam | PF00046 | ||||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0123 | ||||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001356 | ||||||||||

| SMART | SM00389 | ||||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00027 | ||||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1ahd / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

A homeobox is a DNA sequence, around 180 base pairs long, that regulates large-scale anatomical features in the early stages of embryonic development. Mutations in a homeobox may change large-scale anatomical features of the full-grown organism.

Homeoboxes are found within genes that are involved in the regulation of patterns of anatomical development (morphogenesis) in animals, fungi, plants, and numerous single cell eukaryotes.[2] Homeobox genes encode homeodomain protein products that are transcription factors sharing a characteristic protein fold structure that binds DNA to regulate expression of target genes.[3][4][2] Homeodomain proteins regulate gene expression and cell differentiation during early embryonic development, thus mutations in homeobox genes can cause developmental disorders.[5]

Homeosis is a term coined by William Bateson to describe the outright replacement of a discrete body part with another body part, e.g. antennapedia—replacement of the antenna on the head of a fruit fly with legs.[6] The "homeo-" prefix in the words "homeobox" and "homeodomain" stems from this mutational phenotype, which is observed when some of these genes are mutated in animals. The homeobox domain was first identified in a number of Drosophila homeotic and segmentation proteins, but is now known to be well-conserved in many other animals, including vertebrates.[3][7][8]

Discovery

[edit]

The existence of homeobox genes was first discovered in Drosophila by isolating the gene responsible for a homeotic transformation where legs grow from the head instead of the expected antennae. Walter Gehring identified a gene called antennapedia that caused this homeotic phenotype.[9] Analysis of antennapedia revealed that this gene contained a 180 base pair sequence that encoded a DNA binding domain, which William McGinnis termed the "homeobox".[10] The existence of additional Drosophila genes containing the antennapedia homeobox sequence was independently reported by Ernst Hafen, Michael Levine, William McGinnis, and Walter Jakob Gehring of the University of Basel in Switzerland and Matthew P. Scott and Amy Weiner of Indiana University in Bloomington in 1984.[11][12] Isolation of homologous genes by Edward de Robertis and William McGinnis revealed that numerous genes from a variety of species contained the homeobox.[13][14] Subsequent phylogenetic studies detailing the evolutionary relationship between homeobox-containing genes showed that these genes are present in all bilaterian animals.

Homeodomain structure

[edit]The characteristic homeodomain protein fold consists of a 60-amino acid long domain composed of three alpha helices. The following shows the consensus homeodomain (~60 amino acid chain):[15]

Helix 1 Helix 2 Helix 3/4

______________ __________ _________________

RRRKRTAYTRYQLLELEKEFHFNRYLTRRRRIELAHSLNLTERHIKIWFQNRRMKWKKEN

....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|....|

10 20 30 40 50 60

Helix 2 and helix 3 form a so-called helix-turn-helix (HTH) structure, where the two alpha helices are connected by a short loop region. The N-terminal two helices of the homeodomain are antiparallel and the longer C-terminal helix is roughly perpendicular to the axes of the first two. It is this third helix that interacts directly with DNA via a number of hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions, as well as indirect interactions via water molecules, which occur between specific side chains and the exposed bases within the major groove of the DNA.[7]

Homeodomain proteins are found in eukaryotes.[2] Through the HTH motif, they share limited sequence similarity and structural similarity to prokaryotic transcription factors,[16] such as lambda phage proteins that alter the expression of genes in prokaryotes. The HTH motif shows some sequence similarity but a similar structure in a wide range of DNA-binding proteins (e.g., cro and repressor proteins, homeodomain proteins, etc.). One of the principal differences between HTH motifs in these different proteins arises from the stereochemical requirement for glycine in the turn which is needed to avoid steric interference of the beta-carbon with the main chain: for cro and repressor proteins the glycine appears to be mandatory, whereas for many of the homeotic and other DNA-binding proteins the requirement is relaxed.

Sequence specificity

[edit]Homeodomains can bind both specifically and nonspecifically to B-DNA with the C-terminal recognition helix aligning in the DNA's major groove and the unstructured peptide "tail" at the N-terminus aligning in the minor groove. The recognition helix and the inter-helix loops are rich in arginine and lysine residues, which form hydrogen bonds to the DNA backbone. Conserved hydrophobic residues in the center of the recognition helix aid in stabilizing the helix packing. Homeodomain proteins show a preference for the DNA sequence 5'-TAAT-3'; sequence-independent binding occurs with significantly lower affinity. The specificity of a single homeodomain protein is usually not enough to recognize specific target gene promoters, making cofactor binding an important mechanism for controlling binding sequence specificity and target gene expression. To achieve higher target specificity, homeodomain proteins form complexes with other transcription factors to recognize the promoter region of a specific target gene.

Biological function

[edit]Homeodomain proteins function as transcription factors due to the DNA binding properties of the conserved HTH motif. Homeodomain proteins are considered to be master control genes, meaning that a single protein can regulate expression of many target genes. Homeodomain proteins direct the formation of the body axes and body structures during early embryonic development.[17] Many homeodomain proteins induce cellular differentiation by initiating the cascades of coregulated genes required to produce individual tissues and organs. Other proteins in the family, such as NANOG are involved in maintaining pluripotency and preventing cell differentiation.

Regulation

[edit]Hox genes and their associated microRNAs are highly conserved developmental master regulators with tight tissue-specific, spatiotemporal control. These genes are known to be dysregulated in several cancers and are often controlled by DNA methylation.[18][19] The regulation of Hox genes is highly complex and involves reciprocal interactions, mostly inhibitory. Drosophila is known to use the polycomb and trithorax complexes to maintain the expression of Hox genes after the down-regulation of the pair-rule and gap genes that occurs during larval development. Polycomb-group proteins can silence the Hox genes by modulation of chromatin structure.[20]

Mutations

[edit]Mutations to homeobox genes can produce easily visible phenotypic changes in body segment identity, such as the Antennapedia and Bithorax mutant phenotypes in Drosophila. Duplication of homeobox genes can produce new body segments, and such duplications are likely to have been important in the evolution of segmented animals.

Evolution

[edit]Phylogenetic analysis of homeobox gene sequences and homeodomain protein structures suggests that the last common ancestor of plants, fungi, and animals had at least two homeobox genes.[21] Molecular evidence shows that some limited number of Hox genes have existed in the Cnidaria since before the earliest true Bilatera, making these genes pre-Paleozoic.[22] It is accepted that the three major animal ANTP-class clusters, Hox, ParaHox, and NK (MetaHox), are the result of segmental duplications. A first duplication created MetaHox and ProtoHox, the latter of which later duplicated into Hox and ParaHox. The clusters themselves were created by tandem duplications of a single ANTP-class homeobox gene.[23] Gene duplication followed by neofunctionalization is responsible for the many homeobox genes found in eukaryotes.[24][25] Comparison of homeobox genes and gene clusters has been used to understand the evolution of genome structure and body morphology throughout metazoans.[26]

Types of homeobox genes

[edit]Hox genes

[edit]

Hox genes are the most commonly known subset of homeobox genes. They are essential metazoan genes that determine the identity of embryonic regions along the anterior-posterior axis.[27] The first vertebrate Hox gene was isolated in Xenopus by Edward De Robertis and colleagues in 1984.[28] The main interest in this set of genes stems from their unique behavior and arrangement in the genome. Hox genes are typically found in an organized cluster. The linear order of Hox genes within a cluster is directly correlated to the order in which they are expressed in both time and space during development. This phenomenon is called colinearity.

Mutations in these homeotic genes cause displacement of body segments during embryonic development. This is called ectopia. For example, when one gene is lost the segment develops into a more anterior one, while a mutation that leads to a gain of function causes a segment to develop into a more posterior one. Famous examples are Antennapedia and bithorax in Drosophila, which can cause the development of legs instead of antennae and the development of a duplicated thorax, respectively.[29]

In vertebrates, the four paralog clusters are partially redundant in function, but have also acquired several derived functions. For example, HoxA and HoxD specify segment identity along the limb axis.[30][31] Specific members of the Hox family have been implicated in vascular remodeling, angiogenesis, and disease by orchestrating changes in matrix degradation, integrins, and components of the ECM.[32] HoxA5 is implicated in atherosclerosis.[33][34] HoxD3 and HoxB3 are proinvasive, angiogenic genes that upregulate b3 and a5 integrins and Efna1 in ECs, respectively.[35][36][37][38] HoxA3 induces endothelial cell (EC) migration by upregulating MMP14 and uPAR. Conversely, HoxD10 and HoxA5 have the opposite effect of suppressing EC migration and angiogenesis, and stabilizing adherens junctions by upregulating TIMP1/downregulating uPAR and MMP14, and by upregulating Tsp2/downregulating VEGFR2, Efna1, Hif1alpha and COX-2, respectively.[39][40] HoxA5 also upregulates the tumor suppressor p53 and Akt1 by downregulation of PTEN.[41] Suppression of HoxA5 has been shown to attenuate hemangioma growth.[42] HoxA5 has far-reaching effects on gene expression, causing ~300 genes to become upregulated upon its induction in breast cancer cell lines.[42] HoxA5 protein transduction domain overexpression prevents inflammation shown by inhibition of TNFalpha-inducible monocyte binding to HUVECs.[43][44]

LIM genes

[edit]LIM genes (named after the initial letters of the names of three proteins where the characteristic domain was first identified) encode two 60 amino acid cysteine and histidine-rich LIM domains and a homeodomain. The LIM domains function in protein-protein interactions and can bind zinc molecules. LIM domain proteins are found in both the cytosol and the nucleus. They function in cytoskeletal remodeling, at focal adhesion sites, as scaffolds for protein complexes, and as transcription factors.[45]

Pax genes

[edit]Most Pax genes contain a homeobox and a paired domain that also binds DNA to increase binding specificity, though some Pax genes have lost all or part of the homeobox sequence.[46] Pax genes function in embryo segmentation, nervous system development, generation of the frontal eye fields, skeletal development, and formation of face structures. Pax 6 is a master regulator of eye development, such that the gene is necessary for development of the optic vesicle and subsequent eye structures.[47]

POU genes

[edit]Proteins containing a POU region consist of a homeodomain and a separate, structurally homologous POU domain that contains two helix-turn-helix motifs and also binds DNA. The two domains are linked by a flexible loop that is long enough to stretch around the DNA helix, allowing the two domains to bind on opposite sides of the target DNA, collectively covering an eight-base segment with consensus sequence 5'-ATGCAAAT-3'. The individual domains of POU proteins bind DNA only weakly, but have strong sequence-specific affinity when linked. The POU domain itself has significant structural similarity with repressors expressed in bacteriophages, particularly lambda phage.

Plant homeobox genes

[edit]As in animals, the plant homeobox genes code for the typical 60 amino acid long DNA-binding homeodomain or in case of the TALE (three amino acid loop extension) homeobox genes for an atypical homeodomain consisting of 63 amino acids. According to their conserved intron–exon structure and to unique codomain architectures they have been grouped into 14 distinct classes: HD-ZIP I to IV, BEL, KNOX, PLINC, WOX, PHD, DDT, NDX, LD, SAWADEE and PINTOX.[24] Conservation of codomains suggests a common eukaryotic ancestry for TALE[48] and non-TALE homeodomain proteins.[49]

Human homeobox genes

[edit]The Hox genes in humans are organized in four chromosomal clusters:

| name | chromosome | gene |

| HOXA (or sometimes HOX1) - HOXA@ | chromosome 7 | HOXA1, HOXA2, HOXA3, HOXA4, HOXA5, HOXA6, HOXA7, HOXA9, HOXA10, HOXA11, HOXA13 |

| HOXB - HOXB@ | chromosome 17 | HOXB1, HOXB2, HOXB3, HOXB4, HOXB5, HOXB6, HOXB7, HOXB8, HOXB9, HOXB13 |

| HOXC - HOXC@ | chromosome 12 | HOXC4, HOXC5, HOXC6, HOXC8, HOXC9, HOXC10, HOXC11, HOXC12, HOXC13 |

| HOXD - HOXD@ | chromosome 2 | HOXD1, HOXD3, HOXD4, HOXD8, HOXD9, HOXD10, HOXD11, HOXD12, HOXD13 |

ParaHox genes are analogously found in four areas. They include CDX1, CDX2, CDX4; GSX1, GSX2; and PDX1. Other genes considered Hox-like include EVX1, EVX2; GBX1, GBX2; MEOX1, MEOX2; and MNX1. The NK-like (NKL) genes, some of which are considered "MetaHox", are grouped with Hox-like genes into a large ANTP-like group.[50][51]

Humans have a "distal-less homeobox" family: DLX1, DLX2, DLX3, DLX4, DLX5, and DLX6. Dlx genes are involved in the development of the nervous system and of limbs.[52] They are considered a subset of the NK-like genes.[50]

Human TALE (Three Amino acid Loop Extension) homeobox genes for an "atypical" homeodomain consist of 63 rather than 60 amino acids: IRX1, IRX2, IRX3, IRX4, IRX5, IRX6; MEIS1, MEIS2, MEIS3; MKX; PBX1, PBX2, PBX3, PBX4; PKNOX1, PKNOX2; TGIF1, TGIF2, TGIF2LX, TGIF2LY.[50]

In addition, humans have the following homeobox genes and proteins:[50]

- LIM-class: ISL1, ISL2; LHX1, LHX2, LHX3, LHX4, LHX5, LHX6, LHX8, LHX9;[a] LMX1A, LMX1B

- POU-class: HDX; POU1F1; POU2F1; POU2F2; POU2F3; POU3F1; POU3F2; POU3F3; POU3F4; POU4F1; POU4F2; POU4F3; POU5F1; POU5F1P1; POU5F1P4; POU5F2; POU6F1; and POU6F2

- CERS-class: LASS2, LASS3, LASS4, LASS5, LASS6;

- HNF-class: HMBOX1; HNF1A, HNF1B;

- SINE-class: SIX1, SIX2, SIX3, SIX4, SIX5, SIX6[b]

- CUT-class: ONECUT1, ONECUT2, ONECUT3; CUX1, CUX2; SATB1, SATB2;

- ZF-class: ADNP, ADNP2; TSHZ1, TSHZ2, TSHZ3; ZEB1, ZEB2; ZFHX2, ZFHX3, ZFHX4; ZHX1, HOMEZ;

- PRD-class: ALX1 (CART1), ALX3, ALX4; ARGFX; ARX; DMBX1; DPRX; DRGX; DUXA, DUXB, DUX (1, 2, 3, 4, 4c, 5);[c] ESX1; GSC, GSC2; HESX1; HOPX; ISX; LEUTX; MIXL1; NOBOX; OTP; OTX1, OTX2, CRX; PAX2, PAX3, PAX4, PAX5, PAX6, PAX7, PAX8;[d] PHOX2A, PHOX2B; PITX1, PITX2, PITX3; PROP1; PRRX1, PRRX2; RAX, RAX2; RHOXF1, RHOXF2/2B; SEBOX; SHOX, SHOX2; TPRX1; UNCX; VSX1, VSX2

- NKL-class: BARHL1, BARHL2; BARX1, BARX2; BSX; DBX1, DBX2; EMX1, EMX2; EN1, EN2; HHEX; HLX1; LBX1, LBX2; MSX1, MSX2; NANOG; NOTO; TLX1, TLX2, TLX3; TSHZ1, TSHZ2, TSHZ3; VAX1, VAX2, VENTX;

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ PDB: 1AHD; Billeter M, Qian YQ, Otting G, Müller M, Gehring W, Wüthrich K (December 1993). "Determination of the nuclear magnetic resonance solution structure of an Antennapedia homeodomain-DNA complex". Journal of Molecular Biology. 234 (4): 1084–93. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1661. PMID 7903398.

- ^ a b c Bürglin TR, Affolter M (June 2016). "Homeodomain proteins: an update". Chromosoma. 125 (3): 497–521. doi:10.1007/s00412-015-0543-8. PMC 4901127. PMID 26464018.

- ^ a b Gehring WJ (August 1992). "The homeobox in perspective". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 17 (8): 277–80. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(92)90434-B. PMID 1357790.

- ^ Gehring WJ (December 1993). "Exploring the homeobox". Gene. 135 (1–2): 215–21. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(93)90068-E. PMID 7903947.

- ^ "Homeoboxes". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- ^ Materials for the study of variation, treated with especial regard to discontinuity in the origin of species William Bateson 1861–1926. London : Macmillan 1894 xv, 598 p

- ^ a b Schofield PN (1987). "Patterns, puzzles and paradigms - The riddle of the homeobox". Trends Neurosci. 10: 3–6. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(87)90113-5. S2CID 53188259.

- ^ Scott MP, Tamkun JW, Hartzell GW (July 1989). "The structure and function of the homeodomain". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer. 989 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1016/0304-419x(89)90033-4. PMID 2568852.

- ^ Garber RL, Kuroiwa A, Gehring WJ (1983). "Genomic and cDNA clones of the homeotic locus Antennapedia in Drosophila". The EMBO Journal. 2 (11): 2027–36. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1983.tb01696.x. PMC 555405. PMID 6416827.

- ^ "Walter Jakob Gehring (1939-2014) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia". embryo.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-12-09. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ McGinnis W, Levine MS, Hafen E, Kuroiwa A, Gehring WJ (1984). "A conserved DNA sequence in homoeotic genes of the Drosophila Antennapedia and bithorax complexes". Nature. 308 (5958): 428–33. Bibcode:1984Natur.308..428M. doi:10.1038/308428a0. PMID 6323992. S2CID 4235713.

- ^ Scott MP, Weiner AJ (July 1984). "Structural relationships among genes that control development: sequence homology between the Antennapedia, Ultrabithorax, and fushi tarazu loci of Drosophila". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (13): 4115–9. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.4115S. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.13.4115. PMC 345379. PMID 6330741.

- ^ Carrasco AE, McGinnis W, Gehring WJ, De Robertis EM (June 1984). "Cloning of an X. laevis gene expressed during early embryogenesis coding for a peptide region homologous to Drosophila homeotic genes". Cell. 37 (2): 409–414. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90371-4. PMID 6327066. S2CID 30114443.

- ^ McGinnis W, Garber RL, Wirz J, Kuroiwa A, Gehring WJ (June 1984). "A homologous protein-coding sequence in Drosophila homeotic genes and its conservation in other metazoans". Cell. 37 (2): 403–8. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90370-2. PMID 6327065. S2CID 40456645. Archived from the original on 2021-05-04. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Bürglin TR. "The homeobox page" (gif). Karolinksa Institute. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ "CATH Superfamily 1.10.10.60". www.cathdb.info. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Corsetti MT, Briata P, Sanseverino L, Daga A, Airoldi I, Simeone A, et al. (September 1992). "Differential DNA binding properties of three human homeodomain proteins". Nucleic Acids Research. 20 (17): 4465–72. doi:10.1093/nar/20.17.4465. PMC 334173. PMID 1357628.

- ^ Dunn J, Thabet S, Jo H (July 2015). "Flow-Dependent Epigenetic DNA Methylation in Endothelial Gene Expression and Atherosclerosis". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 35 (7): 1562–9. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305042. PMC 4754957. PMID 25953647.

- ^ Bhatlekar S, Fields JZ, Boman BM (August 2014). "HOX genes and their role in the development of human cancers". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 92 (8): 811–23. doi:10.1007/s00109-014-1181-y. PMID 24996520. S2CID 17159381.

- ^ Portoso M, Cavalli G (2008). "The Role of RNAi and Noncoding RNAs in Polycomb Mediated Control of Gene Expression and Genomic Programming". RNA and the Regulation of Gene Expression: A Hidden Layer of Complexity. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-25-7. Archived from the original on 2012-01-02. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ^ Bharathan G, Janssen BJ, Kellogg EA, Sinha N (December 1997). "Did homeodomain proteins duplicate before the origin of angiosperms, fungi, and metazoa?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (25): 13749–53. Bibcode:1997PNAS...9413749B. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13749. JSTOR 43805. PMC 28378. PMID 9391098.

- ^ Ryan JF, Mazza ME, Pang K, Matus DQ, Baxevanis AD, Martindale MQ, et al. (January 2007). "Pre-bilaterian origins of the Hox cluster and the Hox code: evidence from the sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis". PLOS ONE. 2 (1): e153. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..153R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000153. PMC 1779807. PMID 17252055.

- ^ Garcia-Fernàndez J (December 2005). "The genesis and evolution of homeobox gene clusters". Nature Reviews Genetics. 6 (12): 881–92. doi:10.1038/nrg1723. PMID 16341069. S2CID 42823485.

- ^ a b Mukherjee K, Brocchieri L, Bürglin TR (December 2009). "A comprehensive classification and evolutionary analysis of plant homeobox genes". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26 (12): 2775–94. doi:10.1093/molbev/msp201. PMC 2775110. PMID 19734295.

- ^ Holland PW (2013). "Evolution of homeobox genes". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology. 2 (1): 31–45. doi:10.1002/wdev.78. PMID 23799629. S2CID 44396110.

- ^ Ferrier DE (2016). "Evolution of Homeobox Gene Clusters in Animals: The Giga-Cluster and Primary vs. Secondary Clustering". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 4. doi:10.3389/fevo.2016.00036. hdl:10023/8685. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Alonso CR (November 2002). "Hox proteins: sculpting body parts by activating localized cell death". Current Biology. 12 (22): R776-8. Bibcode:2002CBio...12.R776A. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01291-5. PMID 12445403. S2CID 17558233.

- ^ Carrasco AE, McGinnis W, Gehring WJ, De Robertis EM (June 1984). "Cloning of an X. laevis gene expressed during early embryogenesis coding for a peptide region homologous to Drosophila homeotic genes". Cell. 37 (2): 409–14. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90371-4. PMID 6327066. S2CID 30114443.

- ^ Schneuwly S, Klemenz R, Gehring WJ (1987). "Redesigning the body plan of Drosophila by ectopic expression of the homoeotic gene Antennapedia". Nature. 325 (6107): 816–8. Bibcode:1987Natur.325..816S. doi:10.1038/325816a0. PMID 3821869. S2CID 4320668.

- ^ Fromental-Ramain C, Warot X, Messadecq N, LeMeur M, Dollé P, Chambon P (October 1996). "Hoxa-13 and Hoxd-13 play a crucial role in the patterning of the limb autopod". Development. 122 (10): 2997–3011. doi:10.1242/dev.122.10.2997. PMID 8898214.

- ^ Zákány J, Duboule D (April 1999). "Hox genes in digit development and evolution". Cell and Tissue Research. 296 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1007/s004410051262. PMID 10199961. S2CID 3192774.

- ^ Gorski DH, Walsh K (November 2000). "The role of homeobox genes in vascular remodeling and angiogenesis". Circulation Research. 87 (10): 865–72. doi:10.1161/01.res.87.10.865. PMID 11073881.

- ^ Dunn J, Thabet S, Jo H (July 2015). "Flow-Dependent Epigenetic DNA Methylation in Endothelial Gene Expression and Atherosclerosis". Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 35 (7): 1562–9. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305042. PMC 4754957. PMID 25953647.

- ^ Dunn J, Simmons R, Thabet S, Jo H (October 2015). "The role of epigenetics in the endothelial cell shear stress response and atherosclerosis". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 67: 167–76. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2015.05.001. PMC 4592147. PMID 25979369.

- ^ Boudreau N, Andrews C, Srebrow A, Ravanpay A, Cheresh DA (October 1997). "Induction of the angiogenic phenotype by Hox D3". The Journal of Cell Biology. 139 (1): 257–64. doi:10.1083/jcb.139.1.257. PMC 2139816. PMID 9314544.

- ^ Boudreau NJ, Varner JA (February 2004). "The homeobox transcription factor Hox D3 promotes integrin alpha5beta1 expression and function during angiogenesis". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (6): 4862–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M305190200. PMID 14610084.

- ^ Myers C, Charboneau A, Boudreau N (January 2000). "Homeobox B3 promotes capillary morphogenesis and angiogenesis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 148 (2): 343–51. doi:10.1083/jcb.148.2.343. PMC 2174277. PMID 10648567.

- ^ Chen Y, Xu B, Arderiu G, Hashimoto T, Young WL, Boudreau N, et al. (November 2004). "Retroviral delivery of homeobox D3 gene induces cerebral angiogenesis in mice". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 24 (11): 1280–7. doi:10.1097/01.WCB.0000141770.09022.AB. PMID 15545924.

- ^ Myers C, Charboneau A, Cheung I, Hanks D, Boudreau N (December 2002). "Sustained expression of homeobox D10 inhibits angiogenesis". The American Journal of Pathology. 161 (6): 2099–109. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64488-4. PMC 1850921. PMID 12466126.

- ^ Mace KA, Hansen SL, Myers C, Young DM, Boudreau N (June 2005). "HOXA3 induces cell migration in endothelial and epithelial cells promoting angiogenesis and wound repair". Journal of Cell Science. 118 (Pt 12): 2567–77. doi:10.1242/jcs.02399. PMID 15914537.

- ^ Rhoads K, Arderiu G, Charboneau A, Hansen SL, Hoffman W, Boudreau N (2005). "A role for Hox A5 in regulating angiogenesis and vascular patterning". Lymphatic Research and Biology. 3 (4): 240–52. doi:10.1089/lrb.2005.3.240. PMID 16379594.

- ^ a b Arderiu G, Cuevas I, Chen A, Carrio M, East L, Boudreau NJ (2007). "HoxA5 stabilizes adherens junctions via increased Akt1". Cell Adhesion & Migration. 1 (4): 185–95. doi:10.4161/cam.1.4.5448. PMC 2634105. PMID 19262140.

- ^ Zhu Y, Cuevas IC, Gabriel RA, Su H, Nishimura S, Gao P, et al. (June 2009). "Restoring transcription factor HoxA5 expression inhibits the growth of experimental hemangiomas in the brain". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 68 (6): 626–32. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a491ce. PMC 2728585. PMID 19458547.

- ^ Chen H, Rubin E, Zhang H, Chung S, Jie CC, Garrett E, et al. (May 2005). "Identification of transcriptional targets of HOXA5". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (19): 19373–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.M413528200. PMID 15757903.

- ^ Kadrmas JL, Beckerle MC (November 2004). "The LIM domain: from the cytoskeleton to the nucleus". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 5 (11): 920–31. doi:10.1038/nrm1499. PMID 15520811. S2CID 6030950.

- ^ Gruss P, Walther C (May 1992). "Pax in development". Cell. 69 (5): 719–22. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90281-G. PMID 1591773. S2CID 44613005. Archived from the original on 2021-05-02. Retrieved 2019-12-11.

- ^ Walther C, Gruss P (December 1991). "Pax-6, a murine paired box gene, is expressed in the developing CNS". Development. 113 (4): 1435–49. doi:10.1242/dev.113.4.1435. PMID 1687460.

- ^ Bürglin TR (November 1997). "Analysis of TALE superclass homeobox genes (MEIS, PBC, KNOX, Iroquois, TGIF) reveals a novel domain conserved between plants and animals". Nucleic Acids Research. 25 (21): 4173–80. doi:10.1093/nar/25.21.4173. PMC 147054. PMID 9336443.

- ^ Derelle R, Lopez P, Le Guyader H, Manuel M (2007). "Homeodomain proteins belong to the ancestral molecular toolkit of eukaryotes". Evolution & Development. 9 (3): 212–9. doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00153.x. PMID 17501745. S2CID 9530210.

- ^ a b c d e Holland PW, Booth HA, Bruford EA (October 2007). "Classification and nomenclature of all human homeobox genes". BMC Biology. 5 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-47. PMC 2211742. PMID 17963489.

- ^ Coulier F, Popovici C, Villet R, Birnbaum D (December 2000). "MetaHox gene clusters". The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 288 (4): 345–351. Bibcode:2000JEZ...288..345C. doi:10.1002/1097-010X(20001215)288:4<345::AID-JEZ7>3.0.CO;2-Y. PMID 11144283.

- ^ Kraus P, Lufkin T (July 2006). "Dlx homeobox gene control of mammalian limb and craniofacial development". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 140 (13): 1366–74. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31252. PMID 16688724. S2CID 32619323.

Further reading

[edit]- Lodish H, Berk A, Matsudaira P, Kaiser CA, Krieger M, Scott MP, et al. (2003). Molecular Cell Biology (5th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.

- Tooze C, Branden J (1999). Introduction to protein structure (2nd ed.). New York: Garland Pub. pp. 159–66. ISBN 978-0-8153-2305-1.

- Ogishima S, Tanaka H (January 2007). "Missing link in the evolution of Hox clusters". Gene. 387 (1–2): 21–30. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.08.011. PMID 17098381.

External links

[edit]- The Homeodomain Resource (National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health)

- HomeoDB: a database of homeobox genes diversity. Zhong YF, Butts T, Holland PWH, since 2008. Archived 2021-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource motif class LIG_HOMEOBOX

- Homeobox at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)