Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Book of Job

View on Wikipedia

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

The Book of Job (Biblical Hebrew: אִיּוֹב, romanized: ʾĪyyōḇ), or simply Job, is a book found in the Ketuvim ("Writings") section of the Hebrew Bible and the first of the Poetic Books in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1]

The language of the Book of Job, combining post-Babylonian Hebrew and Aramaic influences, indicates it was composed during the Persian period (540–330 BCE), with the poet using Hebrew in a learned, literary manner.[2] It addresses the problem of evil, providing a theodicy through the experiences of the eponymous protagonist.[3] It is structured with a prose prologue and epilogue framing poetic dialogues and monologues, including three cycles of debates between Job and his friends, Job’s lamentations, the Poem to Wisdom, Elihu’s speeches, and God’s two speeches from a whirlwind.

Job is a wealthy God-fearing man with a comfortable life and a large family. God discusses Job's piety with a character called the adversary (הַשָּׂטָן, haśśāṭān, lit. 'the adversary'; i.e. “the satan”). The adversary rebukes God, stating that Job would turn away from God if he were to lose everything within his possession. God decides to test that theory by allowing the adversary to inflict pain on Job. Job is tested through extreme suffering, including the loss of his wealth, children, and health, yet he maintains his piety while challenging the justice of God. Job defends himself against his unsympathetic friends, whom God admonishes. The dialogues explore human frailty and the inaccessibility of divine wisdom, culminating in God highlighting His omnipotence and Job confessing his limited understanding. Job’s fortunes and family are restored in the epilogue.

The book has influenced Jewish and Christian theology and liturgy, as well as Western culture. It parallels wisdom traditions from Mesopotamia and Egypt. In Islam, Job (Ayyub) is revered as a prophet exemplifying steadfast faith.

Structure

[edit]

The Book of Job consists of a prose prologue and epilogue narrative framing poetic dialogues and monologues.[4] It is common to view the narrative frame as the original core of the book, enlarged later by the poetic dialogues and discourses, and sections of the book such as the Elihu speeches and the wisdom poem of chapter 28 as late insertions, but recent trends have tended to concentrate on the book's underlying editorial unity.[5]

- Prologue: in two scenes, the first on Earth, the second in Heaven[6]

- Job's opening monologue[7] – seen by some scholars as a bridge between the prologue and the dialogues and by others as the beginning of the dialogues[8] – and three cycles of dialogues between Job and his three friends;[9] the third cycle is not complete, the expected speech of Zophar being replaced by the wisdom poem of chapter 28.[10]

- Three monologues:

- Three speeches by God,[22] with Job's responses

- Epilogue – Job's restoration[23]

Contents

[edit]

Prologue on Earth and in Heaven

[edit]In chapter 1, the prologue on Earth introduces Job as a righteous man, blessed with wealth, sons, and daughters, who lives in the land of Uz. The scene then shifts to Heaven, where God asks Satan (Biblical Hebrew: הַשָּׂטָן, romanized: haśśāṭān, lit. 'the adversary') for his opinion of Job's piety. Satan accuses Job of being pious only because he believes God is responsible for his happiness; if God were to take away everything that Job has, then he would surely curse God.[24]

God gives Satan permission to strip Job of his wealth and kill his children and servants, but Job nonetheless praises God:

- Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return there; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.[25]

In chapter 2, God further allows Satan to afflict Job's body with disfiguring and painful boils. As Job sits in the ashes of his former estate, his wife prompts him to "curse God, and die", but Job answers:

- You speak as any foolish woman would speak. Shall we receive the good at the hand of God, and not receive the bad?[26]

Job's opening monologue and dialogues between Job and his three friends

[edit]In chapter 3, "instead of cursing God",[27] Job laments the night of his conception and the day of his birth; he longs for death, "but it does not come".[28]

His three friends, Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite, visit him, accuse him of sinning, and tell him that his suffering was deserved. Job responds with scorn, calling his visitors "miserable comforters".[29] Job asserts that since a just God would not treat him so harshly, patience in suffering is impossible, and the Creator should not take his creatures so lightly, to come against them with such force.[30]

Job's responses represent one of the most radical restatements of Israelite theology in the Hebrew Bible.[31] He moves away from the pious attitude shown in the prologue and begins to berate God for the disproportionate wrath against him. He sees God as, among others,

Job then shifts his focus from the injustice that he himself suffers to God's governance of the world. He suggests that God does nothing to punish the wicked, who have taken advantage of the needy and the helpless, who, in turn, have been left to suffer the significant hardships inflicted on them.[37]

Three monologues: Poem to Wisdom, Job's closing monologue

[edit]

The dialogues of Job and his friends are followed by a poem (the "hymn to wisdom") on the inaccessibility of wisdom: "Where is wisdom to be found?" it asks; it concludes in chapter 28 that wisdom has been hidden from humankind.[38] Job contrasts his previous fortune with his present plight as an outcast, mocked and in pain. He protests his innocence, lists the principles he has lived by, and demands that God answer him.[39]

Elihu's speeches

[edit]A character not previously mentioned, Elihu, intrudes into the story and occupies chapters 32–37. The narrative describes him as stepping out of a crowd of bystanders irate. He intervenes to state that wisdom comes from God, who reveals it through dreams and visions to those who will then declare their knowledge.[38]

Two speeches by God

[edit]From chapter 38, God speaks from a whirlwind.[40] God's speeches do not explain Job's suffering, defend divine justice, enter into the courtroom of confrontation that Job has demanded, or respond to his oath of innocence of which the narrative prologue shows God is well aware.[41]

Instead, God changes the subject to human frailty and contrasts Job's weakness with divine wisdom and omnipotence: "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth?" Job responds briefly, but God's monologue resumes, never addressing Job directly.[42]

In Job 42:1–6, Job makes his final response, confessing God's power and his own lack of knowledge "of things beyond me which I did not know". Previously, he has only heard God, but now his eyes have seen God, and therefore, he declares, "I retract and repent in dust and ashes".[43]

Epilogue

[edit]God tells Eliphaz that he and the two other friends "have not spoken of me what is right as my servant Job has done".

The three are told to make a burnt offering with Job as their intercessor, "for only to him will I show favour". Elihu, the critic of Job and his friends, is notably omitted from this part of the narrative.

The epilogue describes Job's health being restored, his riches and family being remade, and Job living to see the new children born into his family produce grandchildren up to the fourth generation.[44]

Additions to Job

[edit]Among other alterations to the Book of Job, the Septuagint features an extended epilogue. Continuing from the end of 42:17, the Greek edition confirms that Job will be resurrected with the righteous. The addition further identifies Job with Jobab in Genesis, the great grandson of Esau and a king of Edom. Furthermore, Eliphaz in the story of Job is identified as Esau’s firstborn son, Eliphaz, and the king of Taiman; Baldad is noted as the ruler of the Sauchites, and Sophar is noted as the king of the Minneans.

The addition contains several parallels with the writings of Aristeas the Exegete, quoted by Alexander Polyhistor who in turn was quoted in Eusebius in Praeparatio Evangelica 9.25.1-4.[45]

Composition

[edit]

Authorship, language, texts

[edit]The character Job appears in the 6th-century BCE Book of Ezekiel as an exemplary righteous man of antiquity, and the author of the Book of Job has apparently chosen this legendary hero for his parable.[46] The language of the Book of Job, combining post-Babylonian Hebrew and Aramaic influences, indicates it was composed during the Persian period (540–330 BCE), with the poet using Hebrew in a learned, literary manner.[47] The anonymous author was almost certainly an Israelite—although the story is set outside Israel, in southern Edom or northern Arabia—and alludes to places as far apart as Mesopotamia and Egypt.[48] Despite the Israelite origins, it appears that the Book of Job was composed in a time in which wisdom literature was common but not acceptable to Judean sensibilities (i.e., during the Babylonian exile and shortly thereafter).[49]

The speeches of Elihu differ in style from the rest of the book, and neither God nor Job appear to take any note of what he has said; as a result, it is widely believed that Elihu's speeches are a later addition by another author.[50][51]

The language of Job stands out for its conservative spelling and exceptionally large number of words and word forms not found elsewhere in the Bible.[52] Many later scholars, down to the 20th century, have looked for an Aramaic, Arabic, or Edomite origin, but a close analysis suggests that the foreign words and foreign-looking forms are literary affectations designed to lend authenticity to the book's distant setting and give it a foreign flavor.[48][53]

Modern revisions

[edit]Job exists in a number of forms: the Hebrew Masoretic Text, which underlies many modern Bible translations; the Greek Septuagint made in Egypt in the last centuries BCE; and Aramaic and Hebrew manuscripts found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.[54]

In the Latin Vulgate, the New Revised Standard Version, and in Protestant Bibles, it is placed after the Book of Esther as the first of the poetic books.[1] In the Hebrew Bible, it is located within the Ketuvim. John Hartley notes that in Sephardic manuscripts, the texts are ordered as Psalms, Job, and Proverbs, but in Ashkenazic texts, the order is Psalms, Proverbs, and then Job.[1] In the Catholic Jerusalem Bible, it is described as the first of the "wisdom books" and follows the two books of the Maccabees.[55]

Job and the wisdom tradition

[edit]Job, Ecclesiastes, and the Book of Proverbs belong to the genre of wisdom literature, sharing a perspective that they themselves call the "way of wisdom".[56] Wisdom means both a way of thinking and a body of knowledge gained through such thinking, as well as the ability to apply it to life. In its Biblical application in wisdom literature, it is seen as attainable in part through human effort and in part as a gift from God, but never in its entirety—except by God.[57]

The three books of wisdom literature share attitudes and assumptions but differ in their conclusions: Proverbs makes confident statements about the world and its workings that Job and Ecclesiastes flatly contradict.[58] Wisdom literature from Sumeria and Babylonia can be dated to the third millennium BCE.[59] Several texts from ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt offer parallels to Job,[60] and while it is impossible to tell whether any of them influenced the author of Job, their existence suggests that the author was the recipient of a long tradition of reflection on the existence of inexplicable suffering.[61]

Themes

[edit]

The Book of Job is an investigation of the problem of divine justice.[62] This problem, known in theology as the problem of evil or theodicy, can be rephrased as a question: "Why do the righteous suffer?"[3] The conventional answer in ancient Israel was that God rewards virtue and punishes sin (the principle known as "retributive justice").[63] According to this view the moral status of human choices and actions is consequential, but experience demonstrates that suffering is experienced by those who are good.[64]

The biblical concept of righteousness was rooted in the covenant-making God who had ordered creation for communal well-being, and the righteous were those who invested in the community, showing special concern for the poor and needy (see Job's description of his life in chapter 31). Their antithesis were the wicked, who were selfish and greedy.[65] The Satan (or the Adversary) raises the question of whether there is such a thing as disinterested righteousness: if God rewards righteousness with prosperity, will men not act righteously from selfish motives? He asks God to test this by removing the prosperity of Job, the most righteous of all God's servants.[66]

The book begins with the frame narrative, giving the reader an omniscient "God's eye perspective" which introduces Job as a man of exemplary faith and piety, "blameless and upright", who "fears God" and "shuns evil".[67][68] The contrast between the frame and the poetic dialogues and monologues, in which Job never learns of the opening scenes in heaven or of the reason for his suffering, creates a sense of dramatic irony between the divine view of the Adversary's wager, and the human view of Job's suffering "without any reason" (2:3).[68]

In the poetic dialogues Job's friends see his suffering and assume he must be guilty, since God is just. Job, knowing he is innocent, concludes that God must be unjust.[69] He retains his piety throughout the story (contradicting the Adversary's suspicion that his righteousness is due to the expectation of reward), but makes clear from his first speech that he agrees with his friends that God should and does reward righteousness.[70]

The intruder, Elihu, rejects the arguments of both parties:

- Job is wrong to accuse God of injustice, as God is greater than human beings, and

- the visitors are not correct either; for suffering, far from being a punishment, may "rescue the afflicted from their affliction".

That is, suffering can make those afflicted more amenable to revelation – literally, "open their ears" (Job 36:15).[71][69]

Chapter 28, the Poem (or Hymn) to Wisdom, introduces another theme: Divine wisdom. The hymn does not place any emphasis on retributive justice, stressing instead the inaccessibility of wisdom.[72] Wisdom cannot be invented or purchased, it says; God alone knows the meaning of the world, and he grants it only to those who live in reverence before him.[73] God possesses wisdom because he grasps the complexities of the world (Job 28:24–26)[74] – a theme which anticipates God's speech in chapters 38–41, with its repeated refrain "Where were you when ...?"[75]

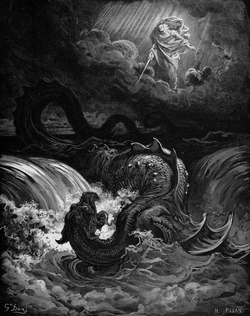

When God finally speaks he neither explains the reason for Job's suffering (known to the reader to be unjust, from the prologue set in heaven) nor defends his justice. The first speech focuses on his role in maintaining order in the universe: The list of things that God does and Job cannot do demonstrates divine wisdom because order is the heart of wisdom. Job then confesses his lack of wisdom, meaning his lack of understanding of the workings of the cosmos and of the ability to maintain it. The second speech concerns God's role in controlling the formidable 'behemoth' and 'leviathan'.[76][b]

Job's reply to God's final speech is longer than his first and more complicated. The usual view is that he admits to being wrong to challenge God and now repents "in dust and ashes" (Job 42:6),[77] but the Hebrew is difficult: An alternative reading is that Job says he was wrong to repent and mourn, and does not retract any of his arguments.[78]

In the concluding part of the frame narrative God restores and increases Job's prosperity, indicating that the divine policy on retributive justice remains unchanged.[79]

Influence and interpretation

[edit]History of interpretation

[edit]

In the Second Temple period (500 BCE–70 CE), the character of Job began to be transformed into something more patient and steadfast, with his suffering a test of virtue and a vindication of righteousness for the glory of God.[80] The process of "sanctifying" Job began with the Greek Septuagint translation (c. 200 BCE) and was furthered in the apocryphal Testament of Job (1st century BCE–1st century CE), which makes him the hero of patience.[81] This reading pays little attention to the Job of the dialogue sections of the book,[82] but it was the tradition taken up by the Epistle of James in the New Testament, which presents Job as one whose patience and endurance should be emulated by believers (James 5:7–11).[83][84]

When Christians began interpreting Job 19:23–29[85] (verses concerning a "redeemer" who Job hopes can save him from God) as a prophecy of Christ,[86] the predominant Jewish view became "Job the blasphemer", with some rabbis even saying that he was rightly punished by God because he had stood by while Pharaoh massacred the innocent Jewish infants.[87][88]

Augustine of Hippo recorded that Job had prophesied the coming of Christ, and Pope Gregory I offered him as a model of right living worthy of respect. The medieval Jewish scholar Maimonides declared his story a parable, and the medieval Christian Thomas Aquinas wrote a detailed commentary declaring it true history. In the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther explained how Job's confession of sinfulness and worthlessness underlay his saintliness, and John Calvin's interpretation of Job demonstrated the doctrine of the resurrection and the ultimate certainty of divine justice.[89]

The contemporary movement known as creation theology, an ecological theology valuing the needs of all creation, interprets God's speeches in Job 38–41 to imply that his interests and actions are not exclusively focused on humankind.[90]

Liturgical use

[edit]Jewish liturgy does not use readings from the Book of Job in the manner of the Pentateuch, Prophets, or Five Megillot, although it is quoted at funerals and times of mourning. However, there are some Jews, particularly the Spanish and Portuguese Jews, who do hold public readings of Job on the Tisha B'Av fast (a day of mourning over the destruction of the First and Second Temples and other tragedies).[91] The cantillation signs for the large poetic section in the middle of the Book of Job differ from those of most of the biblical books, using a system shared with it only by Psalms and Proverbs.

The Eastern Orthodox Church reads from Job and Exodus during Holy Week; Exodus prepares for the understanding of Christ's exodus to His Father and his fulfillment of the whole history of salvation, while Job, the sufferer, is viewed as the Old Testament icon of Christ.[92]

The Roman Catholic Church reads from Job during Matins in the first two weeks of September and in the Office of the Dead,[93] and in the revised Liturgy of the Hours Job is read during the Fifth, Twelfth, and Twenty Sixth Week in Ordinary Time.[94]

In the modern Roman Rite, the Book of Job is read during:

- 5th and 12th Sunday in Ordinary Time – Year B

- Weekday Reading for the 26th Week in Ordinary Time – Year II Cycle

- Ritual Masses for the Anointing of the Sick and Viaticum – First Reading options

- Masses for the Dead – First Reading options

In music, art, literature, and film

[edit]

The Book of Job has been deeply influential in Western culture, to such an extent that no list could be more than representative. Musical settings from Job include Orlande de Lassus's 1565 cycle of motets, the Sacrae Lectiones Novem ex Propheta Iob, and George Frideric Handel's use of Job 19:25 ("I know that my redeemer liveth") as an aria in his 1741 oratorio Messiah.

Modern works based on the book include Ralph Vaughan Williams's Job: A Masque for Dancing; French composer Darius Milhaud's Cantata From Job; and Joseph Stein's Broadway interpretation Fiddler on the Roof, based on the Tevye the Dairyman stories by Sholem Aleichem. Neil Simon wrote God's Favorite, which is a modern retelling of the Book of Job. Breughel and Georges de La Tour depicted Job visited by his wife. William Blake produced an entire cycle of illustrations for the book. It was adapted for Australian radio in 1939.

Archibald MacLeish's drama JB, one of the most prominent uses of the Book of Job in modern literature, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1959. Verses from the Book of Job 3:14 figure prominently in the plot of the film Mission: Impossible (1996).[95] Job's influence can also be seen in the Coen brothers' 2009 film, A Serious Man, which was nominated for two Academy Awards.[96]

Terrence Malick's 2011 film The Tree of Life, which won the Palme d'Or, is heavily influenced by the themes of the Book of Job, with the film starting with a quote from the beginning of God's speech to Job.[97]

The Russian film Leviathan also draws themes from the Book of Job.[98]

The 2014 Indian Malayalam-language film Iyobinte Pusthakam (lit. 'Book of Job') by Amal Neerad tells the story of a man who is losing everything in his life.

"The Sire of Sorrow (Job's Sad Song)" is the final track on Joni Mitchell's 15th studio album, Turbulent Indigo.

In 2015 two Ukrainian composers Roman Grygoriv and Illia Razumeiko created the opera-requiem IYOV. The premiere of the opera was held on 21 September 2015 on the main stage of the international multidisciplinary festival Gogolfest.[99]

In the 3rd episode of the 15th season of ER, the lines of Job 3:23 are quoted by doctor Abby Lockhart shortly before she and her husband (Dr. Luka Covac) leave the series forever.[100]

In season two of Good Omens, the tale of Job and his struggles with good and evil are demonstrated and debated as the demon Crowley is sent to plague Job and his family by destroying his property and children, and the angel Aziraphale struggles with the implications of the actions of God.[101]

In the South Park episode Cartmanland, Kyle Broflovski, who is Jewish, experiences a major crisis of faith. His parents try to cheer him up by reading from the Book of Job, which only serves to demoralize Kyle even more, who despairs at Job's horrific trials by God to prove a point to Satan.[102]

In a series of (now deleted) cryptic tweets detailing the story of an unconfirmed meeting with Bob Dylan, comedian Norm Macdonald makes allusions and references to The Book of Job, calling it his favorite book of the Bible. Dylan allegedly preferred Ecclesiastes.[103][104]

In Islam and Arab folk tradition

[edit]Job (Arabic: ايوب, romanized: Ayyub) is one of the 25 prophets mentioned by name in the Quran, where he is lauded as a steadfast and upright worshipper (Q.38:44). His story has the same basic outline as in the Bible, although the three friends are replaced by his brothers, and his wife stays by his side.[88][105]

In Lebanon, the Muwahideen (or Druze) community maintain a shrine in the Shouf area that is traditionally believed to contain the tomb of Job.[106] In Turkey, Job is known as Eyüp, and he is venerated in Şanlıurfa, where local tradition holds that he lived and suffered.[107] There is also a tomb of Job located outside the city of Salalah in Oman.[108]

See also

[edit]- Answer to Job by Carl Jung

- Book of Job in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts

- Moralia in Job

- Ludlul bēl nēmeqi, the "Babylonian Job"

- Testament of Job

- God's Favorite, a play by Neil Simon, loosely based on the Book of Job

Notes

[edit]- ^ Chapter 28,[19] previously read as part of the speech of Job, is now regarded by most scholars as a separate interlude in the narrator's voice.

- ^ The Hebrew words behemoth and leviathan are sometimes naturalistically translated as the 'hippopotamus' and 'crocodile', but more probably representing more ominous primeval cosmic monsters or chaotic forces, in either case demonstrating God's wisdom and power.[76]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Hartley 1988, p. 3.

- ^ Greenstein, Edward L. (2019). "Introduction". Job: A New Translation. Yale University Press. p. xxvii. ISBN 9780300163766.

Determining the time and place of the book's composition is bound up with the nature of the book's language. The Hebrew prose of the frame tale, notwithstanding many classic features, shows that it was composed in the post-Babylonian era (after 540 BCE). The poetic core of the book is written in a highly literate and literary Hebrew, the eccentricities and occasional clumsiness of which suggest that Hebrew was a learned and not native language of the poet. The numerous words and grammatical shadings of Aramaic spread throughout the mainly Hebrew text of Job make a setting in the Persian era (approximately 540–330) fairly certain, for it was only in that period that Aramaic became a major language throughout the Levant. The poet depends on an audience that will pick up on subtle signs of Aramaic.

- ^ a b Lawson 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Bullock 2007, p. 87.

- ^ Walton 2008, p. 343.

- ^ Job 1–2

- ^ Job 3

- ^ a b Walton 2008, p. 333.

- ^ Job 4–27

- ^ Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 191.

- ^ Job 4–7

- ^ Job 8–10

- ^ Job 11–14

- ^ Job 15–17

- ^ Job 18–19

- ^ Job 20–21

- ^ Job 22–24

- ^ Job 25–27

- ^ Job 28

- ^ Job 29–31

- ^ Job 32–37

- ^ Job 38:1–40:2, Job 40:6–41:34, and Job 42:7–8

- ^ Job 42:9–17

- ^ Job 1:21

- ^ Job 1:21

- ^ Job 2:10

- ^ Crenshaw, J.L. (2001). "17. Job". In Barton, J.; Muddiman, J. (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary. p. 335. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017.

- ^ Job 3:21

- ^ Job 16:2

- ^ Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 190.

- ^ Clines, David J.A. (2004). "Job's God". Concilium. 2004 (4): 39–51.

- ^ Job 7:17–19

- ^ Job 7:20–21

- ^ Job 9:13; Job 14:13; Job 16:9; Job 19:11

- ^ Job 10:13–14

- ^ Job 16:11–14

- ^ Job 24:1–12

- ^ a b Seow 2013, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Sawyer 2013, p. 27.

- ^ Job 38:1

- ^ Walton 2008, p. 339.

- ^ Sawyer 2013, p. 28.

- ^ Habel 1985, p. 575.

- ^ Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 33.

- ^ Charlesworth 1985, p. 855.

- ^ Fokkelman 2012, p. 20.

- ^ Job: A New Translation. Translated by Edward L. Greenstein. Yale University Press. 2019. p. xxvii. ISBN 9780300163766.

Determining the time and place of the book's composition is bound up with the nature of the book's language. The Hebrew prose of the frame tale, notwithstanding many classic features, shows that it was composed in the post-Babylonian era (after 540 BC). The poetic core of the book is written in a highly literate and literary Hebrew, the eccentricities and occasional clumsiness of which suggest that Hebrew was a learned and not native language of the poet. The numerous words and grammatical shadings of Aramaic spread throughout the mainly Hebrew text of Job make a setting in the Persian era (approximately 540–330) fairly certain, for it was only in that period that Aramaic became a major language throughout the Levant. The poet depends on an audience that will pick up on subtle signs of Aramaic.

- ^ a b Seow 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Kugel 2012.

- ^ "Elihu (Biblical figure)". Encyclopedia Brittanica. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2025.

- ^ Alter 2018.

- ^ Seow 2013, p. 17-20.

- ^ Kugel 2012, p. 641.

- ^ Seow 2013, pp. 1–16.

- ^ "Introduction to the Wisdom Books". Jerusalem Bible. 1966. p. 723.

- ^ Farmer 1998, p. 129.

- ^ Farmer 1998, pp. 129–30.

- ^ Farmer 1998, pp. 130–31.

- ^ Bullock 2007, p. 84.

- ^ Hartley 2008, p. 346.

- ^ Hartley 2008, p. 360.

- ^ Bullock 2007, p. 82.

- ^ Hooks 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Brueggemann 2002, p. 201.

- ^ Brueggemann 2002, pp. 177–78.

- ^ Walton 2008, pp. 336–37.

- ^ Hooks 2006, p. 57.

- ^ a b O'Dowd 2008, pp. 242–43.

- ^ a b Seow 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Kugler & Hartin 2009, p. 194.

- ^ Job 36:15

- ^ Dell 2003, p. 356.

- ^ Hooks 2006, pp. 329–30.

- ^ Job 28:24–26

- ^ Fiddes 1996, p. 174.

- ^ a b Walton 2008, p. 338.

- ^ Job 42:6

- ^ Sawyer 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Walton 2008, pp. 338–39.

- ^ Seow 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Allen 2008, pp. 362–63.

- ^ Dell 1991, pp. 6–7.

- ^ James 5:7–11

- ^ Allen 2008, p. 362.

- ^ Job 19:23–29

- ^ Simonetti, Conti & Oden 2006, pp. 105–06.

- ^ Allen 2008, pp. 361–62.

- ^ a b Noegel & Wheeler 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Allen 2008, pp. 368–71.

- ^ Farmer 1998, p. 150.

- ^ "The Connection Between Tisha B'Av and Sefer Iyov (Job)". Orthodox Union. 19 July 2011.

- ^ "With the beginning of the Holy Week they are replaced by Exodus and Job". OMHKSEA (Orthodox Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and Southeast Asia). 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2025.

- ^ Dell 1991, p. 26.

- ^ Bergsma, John Sietze; Pitre, Brant James (2018). A Catholic introduction to the Bible. Volume 1, The Old Testament. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. pp. 556–558. ISBN 978-1-58617-722-5. OCLC 950745091.

- ^ Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda, ed. (2016). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. Handbooks of the Bible and Its Reception (HBR). Vol. 2. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 372. ISBN 9781614513261.

- ^ Tollerton, David (October 2011). "Job of Suburbia? A Serious Man and Viewer Perceptions of the Biblical Biblical". Journal of Religion & Film. 15 (2, Article 7). Omaha: University of Nebraska: 1–11.

- ^ McCracken 2012.

- ^ Moss, Walter G. (16 June 2015). "What Does the Film Leviathan Tell Us about Putin's Russia and Its Past?". History News Network.

- ^ GogolFest. "Program 2015". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "ER: Season 15 Episode 3 Transcript". Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Covill, Max (26 July 2023). "David Tennant, Michael Sheen Continue to Elevate Quality of Good Omens 2". Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on 24 December 2024.

- ^ South Park, Season 5, Episode 6, "Cartmanland". Directed and written by Trey Parker.

- ^ Loofbourow, Lili (16 September 2021). "Norm Macdonald Never Stopped Bulls–tting". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Yakas, Ben (22 January 2015). "Here's Norm Macdonald's Magical Twitter Story About Meeting Bob Dylan". Gothamist. New York Public Radio. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ Wheeler 2002, p. 8.

- ^ "Prophet Job in Lebanon". Al Arabiya. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ "The Cave of Prophet Job (Eyüp Peygamber)". GoTürkiye. Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 3 September 2025.

- ^ Gray, Martin. "Tomb of Prophet Job, Salalah". World Pilgrimage Guide. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, J. (2008). "Job III: History of Interpretation". In Longman III, Tremper; Enns, Peter (eds.). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-83081783-2.

- Alter, Robert (2018). The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary. Vol. 3. W. W. Nortion & Company. ISBN 978-0393292497.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (1996). A History of Prophecy in Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-66425639-5.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of Faith: A Theological Handbook of Old Testament Themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-66422231-4.

- Bullock, C. Hassell (2007). An Introduction to the Old Testament Poetic Books. Moody Publishers. ISBN 978-1-57567450-6.

- Burnight, John (September 2021). Shepherd, David; Tiemeyer, Lena-Sofia (eds.). "Is Eliphaz a false prophet? The vision in Job 4.12–21". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 46 (1). SAGE Publications: 96–116. doi:10.1177/03090892211001404. ISSN 1476-6728. S2CID 238412522.

- Dell, Katharine J. (2003). "Job". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (eds.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-80283711-0.

- Dell, Katherine J. (1991). The Book of Job as Sceptical Literature. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-085873-0. OCLC 857769510.

- Farmer, Kathleen A. (1998). "The Wisdom Books". In McKenzie, Steven L.; Graham, Matt Patrick (eds.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Fiddes, Paul (1996). "'Where Shall Wisdom be Found?' Job 28 as a Riddle for Ancient and Modern Readers". In Barton, John; Reimer, David (eds.). After the Exile: Essays in Honour of Rex Mason. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554524-3.

- Fokkelman, J.P. (2012). The Book of Job in Form: A Literary Translation with Commentary. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-0042-3158-0.

- Hartley, John E. (1988). The Book of Job. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-2528-5.

- Hartley, John E. (2008). "Job II: Ancient Near Eastern Background". In Longman, Tremper; Enns, Peter (eds.). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1783-2.

- Habel, Norman C (1985). The Book of Job: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-6642-2218-5.

- Hooks, Stephen M. (2006). Job. College Press. ISBN 978-0-8990-0886-8.

- Joyce, Paul M. (2009). Ezekiel: A Commentary. Continuum. ISBN 9780567483614.

- Kugel, James L. (2012). How to Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-8909-9.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick J. (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4636-5.

- Lawson, Steven J. (2004). Job. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-9470-9.

- McCracken, Brett (21 May 2012). "The Divine Guide in Terrence Malick's "Tree of Life"". Archived from the original on 13 January 2025. Retrieved 3 August 2025.

- Murphy, Roland Edmund (2002). The Tree of Life: An Exploration of Biblical Wisdom Literature. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-3965-7.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (2010). The A to Z of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1-4617-1895-6.

- O'Dowd, R. (2008). "Frame Narrative". In Longman, Tremper; Enns, Peter (eds.). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1783-2.

- Pihlström, Sami (2015). "Chapter 5. The Problem of Evil and Pragmatic Recognition". In Skowroński, Krzysztof Piotr (ed.). Practicing Philosophy as Experiencing Life. Essays on American Pragmatism. Leiden: Brill. pp. 77–101. doi:10.1163/9789004301993_006. hdl:10138/176976. ISBN 978-9-0043-0199-3.. Docx extract[permanent dead link].

- Sawyer, John F.A. (2013). "Job". In Lieb, Michael; Mason, Emma; Roberts, Jonathan (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1992-0454-0.

- Seow, C.L. (2013). Job 1–21: Interpretation and Commentary. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-4895-6.

- Simonetti, Manlio; Conti, Marco; Oden, Thomas C. (2006). Job. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830814763.

- Vicchio, Stephen J. (2020). The Book of Job: A History of Interpretation and a Commentary. Wipf & Stock. ISBN 978-1-7252-5726-9.

- Walsh, Jerome T (2001). Style and structure in Biblical Hebrew narrative. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658970.

- Walton, J.H. (2008). "Job I: Book of". In Longman, Tremper; Enns, Peter (eds.). Dictionary of the Old Testament: Wisdom, Poetry & Writings. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830817832.

- Wheeler, Brannon M. (18 June 2002). Prophets in the Quran: An Introduction to the Quran and Muslim Exegesis. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-4957-3.

- Wilson, Gerald H. (2012). Job. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-44123839-9.

- Wollaston, Isabell (2013). "Post-Holocaust Interpretations of Job". In Lieb, Michael; Mason, Emma; Roberts, Jonathan (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19967039-0.

Further reading

[edit]- The Dead Sea Scrolls: A New Translation. Translated by Wise, Michael; Abegg Jr, Martin; Cook, Edward (paperback ed.). San Francisco: Harper. 1996. ISBN 0-06-069201-4. (contains the non-biblical portion of the scrolls)

- Papadaki-Oekland, Stella (2009). Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts of the Book of Job. Brepols. ISBN 978-2-503-53232-5.

External links

[edit]- Betesh, David M. "Sephardic Cantillations for the Book of Job". Sephardic Pizmonim Project.

- Translations of The Book of Job at BibleGateway.com

- "Hebrew and English Parallel and Complete Text of the Book of Job". Archived from the original on 16 October 2011 – via Mechon Mamre. English Translation is the 1917 Old JPS

- "Introduction to the Book of Job" (PDF). 6 September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2015.[dead link]

Bible: Job public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Bible: Job public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Book of Job

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Place in the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament

The Book of Job occupies a position in the Ketuvim ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), where it follows Psalms and Proverbs as the third book overall in this division.[4] This placement reflects its classification among the diverse writings that include poetry, wisdom literature, and historical narratives, distinct from the Torah (Law) and Nevi'im (Prophets).[5] In the Christian Old Testament, the Book of Job is commonly grouped with the Poetical or Wisdom Books, typically appearing first in this category after the historical books and before Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon in Protestant canons.[6] Its inclusion in the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures from the third to second centuries BCE, ensured its transmission into early Christian usage and influenced the shape of the broader Old Testament canon.[7] Similarly, Jerome's Vulgate, the late fourth-century Latin translation, incorporated the book intact, reinforcing its canonical status in Western Christianity.[8] Comprising 42 chapters, the Book of Job is distinguished by its hybrid structure: a prose prologue and epilogue frame extensive poetic dialogues and speeches, setting it apart in biblical categorization as a blend of narrative and verse forms.[9] This format underscores its role within the wisdom tradition, addressing profound existential questions through literary artistry.[4]Genre, Form, and Literary Style

The Book of Job is classified as a work of wisdom literature within the Hebrew Bible, sharing thematic concerns with books such as Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, which explore human existence, morality, and divine order through reflective discourse. However, it stands out as a unique theodicy narrative structured as a dramatic debate, where protagonists engage in extended dialogues to probe the justice of suffering, diverging from the more proverbial or observational style of its counterparts.[10] Formally, the book employs a prose frame consisting of a prologue (chapters 1–2) and epilogue (chapter 42:7–17) that narrate Job's trials and restoration, enclosing a lengthy poetic core (chapters 3–42:6) dominated by dialogues and speeches.[11] This poetic section features strophic organization, where verses are grouped into stanzas often following patterns of five or seven lines, enhancing rhythmic flow and emphasis.[12] Parallelism is a hallmark, with synonymous, antithetic, and synthetic structures repeating ideas across lines to build intensity, while repetition of key phrases—such as references to divine "hand" or "way"—underscores thematic persistence.[13] Stylistic techniques abound, including rhetorical questions that propel the debate, as seen in Job's challenges like "Why died I not from the womb?" (Job 3:11), which evoke existential lament.[14] Vivid imagery dominates God's speeches, portraying cosmic creatures like Behemoth and Leviathan as emblems of untamed power under divine control, with Behemoth's "tail" likened to a cedar and Leviathan's scales impenetrable (Job 40:15–24; 41:1–34).[15] Irony permeates the dialogues, evident in the friends' dogmatic assertions of retributive justice that unravel against Job's innocence, subverting conventional wisdom.[16] Subtle acrostic elements appear in places, such as partial alphabetic sequencing in Job 3 and half-line patterns in Job 9:25–31, contributing to mnemonic and structural sophistication.[12] The book's genre parallels ancient Near Eastern suffering laments, particularly Mesopotamian texts like Ludlul bēl nēmeqi ("The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer"), a first-person monologue of undeserved affliction resolved by divine intervention, and the Babylonian Theodicy, a dialogue poem where a sufferer debates friends on injustice, mirroring Job's disputational form.[17] These affinities highlight shared motifs of pious endurance and cosmic questioning, positioning Job within a broader tradition of exploring human-divine tensions.[18]Composition and Textual History

Authorship, Dating, and Historical Context

The traditional attribution of the Book of Job to Moses appears in some ancient Jewish sources, such as the Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14b-15a), which suggests Mosaic authorship for several biblical books including Job, possibly due to its placement among the Torah writings and perceived ancient wisdom style.[19] Other traditions propose Job himself as the author, given the personal nature of the narrative and his role as a central figure, though no explicit internal evidence supports this.[20] In contrast, modern scholarship overwhelmingly views the book as anonymous, with no named author in the text or reliable ancient attributions, emphasizing its composition as a work of collective wisdom literature rather than individual authorship.[21][1] Linguistic evidence, including archaic Hebrew forms mixed with later Aramaic influences, points to a composition date between the 7th and 4th centuries BCE, likely during or after the Babylonian exile in the post-exilic period.[21][1] The prose frame (Job 1–2 and 42:7–17) exhibits features of Late Biblical Hebrew consistent with the Persian era (after 540 BCE), while the poetic core reflects a transitional style from exilic to post-exilic Judaism.[2] Earliest surviving fragments, such as those from the Dead Sea Scrolls (e.g., 4QJob^a and 11Q10 in Aramaic), date to the 2nd century BCE, confirming the book's canonical status by that time but not its original composition.[21][22] The historical context of the Book of Job is rooted in Persian-period Judaism (540–330 BCE), a time of cultural reconstruction following the Babylonian exile's traumas of displacement and suffering, which may have inspired its exploration of undeserved affliction.[2][21] Set in the Land of Uz, associated with Edomite territory east of Israel, the narrative draws on ancient Near Eastern motifs but reflects Judean perspectives, possibly using Job as a non-Israelite figure to universalize themes of divine justice amid Persian imperial influences like Aramaic as a lingua franca.[23][2] Scholarly debates on the book's unity center on whether it stems from a single author or multiple redactors, with evidence from shifts in tone, vocabulary, and theology suggesting composite origins.[1] The prose prologue and epilogue, resembling a folktale with a retributive resolution, contrast with the poetic dialogues' unresolved questioning of suffering, leading many to propose the poetry as an expansion of an earlier prose story by later authors or editors.[21][24] The Elihu speeches (Job 32–37) are often seen as a distinct addition due to their unique style and placement, potentially inserted to bridge tensions between the friends' arguments and God's response, though some argue for overall authorial unity through deliberate stylistic variation.[21][25]Language, Manuscripts, and Textual Variants

The Book of Job is composed primarily in Hebrew, with its framing prose narrative employing standard biblical Hebrew typical of later periods, while the central poetic dialogues exhibit archaic features intended to convey antiquity and poetic elevation.[26] These archaic elements include unusual verbal forms, such as the frequent use of the yqtl conjugation for past actions and jussive moods in narrative contexts, alongside rare syntax that distinguishes it from standard prose.[27] The poetry incorporates loanwords from neighboring Semitic languages, notably around 30 confirmed Aramaisms that clarify otherwise obscure terms, and proposed Arabic influences in approximately 37 words, though the latter theory receives limited scholarly support due to insufficient evidence.[27] The linguistic complexity is amplified by a high density of hapax legomena—unique words appearing only once in the Hebrew Bible—numbering over 180 instances, which pose significant challenges for interpretation and translation by creating ambiguities in key theological passages.[27] For example, terms like yšp in Job 28:17 (possibly denoting a precious stone) and šḥq in Job 41:1 (related to laughter or mockery) remain debated, often requiring recourse to cognate languages for proposed meanings.[26] This poetic ambiguity, combined with deliberate archaisms, has led translators across traditions to vary widely in rendering passages such as Job 3:8, where rare words evoke cosmic curses but resist precise equivalence.[27] The authoritative Hebrew text of Job is the Masoretic Text (MT), preserved in medieval codices like the Leningrad Codex (c. 1008 CE) and Aleppo Codex (c. 925 CE), which standardize vocalization, accents, and consonants through meticulous scribal traditions.[28] Fragments from the Dead Sea Scrolls, dating to the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, provide earlier witnesses, including four Hebrew manuscripts (4QJob^a, 4QJob^b, 4QpaleoJob^c, and 4QJob^d) that generally align closely with the MT, though with minor orthographic and grammatical variants, such as expanded spellings in 4QJob^a at Job 33:28.[29] An Aramaic Targum of Job (11QtgJob) from Qumran Cave 11 expands the text interpretively, adding explanatory phrases to clarify difficult Hebrew, reflecting early Jewish exegesis. The Septuagint (LXX), a Greek translation from the 3rd-2nd centuries BCE, presents a shorter version of the poetic sections—omitting about 400 lines compared to the MT, likely for stylistic simplification—while appending a unique epilogue (Job 42:17a-e) that includes Job's repentance and genealogical details not in the Hebrew.[30] The Latin Vulgate, Jerome's 4th-century CE translation, occasionally alters the MT based on Hebrew consultations and LXX influences, such as rendering ambiguous terms in Job 19:25-27 with Christological overtones that diverge from the Hebrew's poetic uncertainty. Modern critical editions, like the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1977), rely on the Leningrad Codex as the base text while noting variants from the DSS, LXX, and other witnesses in the apparatus, aiding scholars in reconstructing potential earlier forms. These variants highlight transmission challenges, including scribal omissions in the LXX's poetic condensations and interpretive expansions in the Targum, which underscore the text's fluidity before standardization.[28]Narrative Summary

Prologue in Heaven and on Earth

The prologue of the Book of Job, comprising chapters 1 and 2, introduces the central character and establishes the narrative framework through a prose account that contrasts with the poetic dialogues to follow.[31][32] In the land of Uz, Job is depicted as a blameless and upright man who fears God and turns away from evil, possessing immense wealth including seven thousand sheep, three thousand camels, five hundred yoke of oxen, five hundred donkeys, and a large household, making him the greatest among the people of the East.[31] He has seven sons and three daughters, and demonstrates his piety by regularly sanctifying his children after their feasts and offering burnt sacrifices on their behalf in case they had sinned.[31] The narrative shifts to a heavenly scene where the divine beings, including "the satan" as an accuser, present themselves before God.[31] God praises Job's integrity, prompting the satan to challenge whether Job's fear of God is genuine or merely a response to divine blessings and protection.[31][32] God permits the satan to test Job by afflicting his possessions and family but spares his life, setting the stage for an exploration of undeserved suffering.[31][33] On earth, messengers successively report calamities: Sabeans steal Job's oxen and donkeys, killing the servants; fire from heaven consumes his sheep and more servants; Chaldeans raid his camels, slaying additional servants; and a great wind collapses the house where his children are feasting, killing all seven sons and three daughters.[31] Job responds by tearing his robe, shaving his head, falling to the ground in worship, and declaring, "Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return there; the Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord," without sinning or charging God with wrongdoing.[31][33] A second heavenly encounter ensues, with the satan again appearing before God, who reaffirms Job's steadfastness despite the losses.[31] The accuser now proposes testing Job's faith through physical affliction, claiming he would curse God if his body were harmed, and receives permission to strike Job's health but not his life.[31][32] The satan afflicts Job with painful sores from head to foot; Job's wife urges him to curse God and die, but he rebukes her, asking, "Shall we receive the good from the hand of God, and not the bad?" and maintains his integrity without sinning.[31][33] This sequence of events frames the ensuing poetic debates by highlighting Job's unyielding piety amid profound loss, underscoring the tension between divine sovereignty and human endurance in the face of suffering.[32]Dialogues with Job's Friends and Job's Monologues

The dialogues between Job and his three friends—Eliphaz the Temanite, Bildad the Shuhite, and Zophar the Naamathite—form the poetic core of the Book of Job, spanning chapters 3–31 and organized into three cycles of speeches that explore the reasons for Job's suffering.[34] In each cycle, the friends speak in turn, accusing Job of hidden sin as the cause of his afflictions, while Job responds by asserting his innocence and challenging their assumptions.[35] This structure highlights a debate rooted in retributive theology, where the friends maintain that God rewards the righteous and punishes the wicked, implying Job's suffering must stem from moral failing.[36] The section opens with Job's monologue in chapter 3, a poignant lament where he curses the day of his birth and wishes for death as an escape from his unrelenting pain, setting the tone for his subsequent defenses.[34] In the first cycle (chapters 4–14), Eliphaz begins by recalling a terrifying nocturnal vision of a spirit that emphasized human imperfection and the certainty of divine discipline for wrongdoing (Job 4:12–21), urging Job to repent and trust in God's benevolence (Job 5:8–27).[37] Bildad follows, insisting that God does not pervert justice and that Job's children likely perished for their sins (Job 8:3–4), while Zophar accuses Job of mockery and demands submission to divine inscrutability (Job 11:2–6). Job counters each speech, rejecting their logic, affirming his upright life, and pleading for a hearing from God (e.g., Job 6–7, 9–10, 12–14).[35] The second cycle (chapters 15–21) intensifies the friends' rhetoric: Eliphaz rebukes Job's impatience as folly (Job 15:2–6), Bildad warns of the wicked's destruction (Job 18:5–21), and Zophar describes the short-lived prosperity of the unrighteous (Job 20:4–29), all reinforcing retribution as divine order. Job's replies grow bolder, denouncing the friends as "miserable comforters" (Job 16:2) and envisioning his vindication (Job 19:25–27), while emphasizing the apparent injustice of his fate.[34] The third cycle (chapters 22–27) becomes more fragmented; Eliphaz charges Job with specific oppressions like exploiting widows (Job 22:6–9), Bildad questions human worthiness before God (Job 25:4–6), and Zophar's speech is absent or curtailed, with Job dominating to proclaim God's sovereignty amid suffering (Job 27:2–6). Throughout, the friends' arguments consistently invoke retributive theology, viewing suffering as direct punishment, though their speeches progressively shorten and repeat themes without new insight.[36] Interrupting the cycles, chapter 28 presents a poem on wisdom as an interlude, portraying humans' exhaustive searches in mining and exploration as futile in attaining true understanding, which resides solely with God: "The deep says, 'It is not in me,' and the sea says, 'It is not with me.' ... God understands the way to it, and he knows its place" (Job 28:14, 23).[38] This hymn underscores the limits of human knowledge in fathoming divine purposes. The dialogues conclude with Job's extended monologues in chapters 29–31, where he reminisces about his former prosperity and benevolence (Job 29), contrasts it with his current degradation (Job 30), and seals his defense with an oath of purity, calling heaven and earth as witnesses to his blamelessness (Job 31:1–40).[35]Elihu's Speeches and God's Responses

Following the cycles of dialogue between Job and his three friends, who had advocated a strict doctrine of retribution whereby suffering serves as divine punishment for sin, the narrative introduces Elihu, a younger bystander who had remained silent until this point. Elihu delivers four distinct speeches in Job 32–37, positioning himself as a mediator frustrated by the elders' failure to adequately address Job's plight. In his first speech (Job 32:1–22), Elihu rebukes the friends for their inability to refute Job convincingly and asserts that wisdom is not confined to age, claiming divine inspiration for his words (Job 32:8, 18).[39] He then criticizes Job for justifying himself over God (Job 32:2–3; 33:9–12).[40] In the second speech (Job 33:1–33), Elihu emphasizes God's justice through merciful discipline, portraying suffering as a means of correction rather than mere punishment, with examples of divine warnings via dreams during sleep (Job 33:14–18). He describes how God may afflict with pain on a bed to turn individuals from wrongdoing, ultimately ransoming them from death if they repent (Job 33:19–28).[39] The third speech (Job 34:1–37) defends God's impartiality, arguing that the Almighty does no injustice and that prosperity or adversity reflects moral order, urging Job to recognize his error in challenging divine ways (Job 34:5–12, 31–33).[39] Elihu's fourth speech (Job 35:1–37:24) expands on God's transcendence, using natural wonders—such as thunder, lightning, rain, and snow—to illustrate divine sovereignty over creation, which humbles human complaints and reveals God's inscrutable purposes (Job 36:26–37:13). He concludes by evoking awe at God's majesty in the storm, preparing the scene for further revelation (Job 37:14–24).[39][40] Elihu's interventions serve a transitional function, reshaping the retribution theology of the friends by highlighting suffering's potential as educative discipline while critiquing Job's self-justification, thus bridging the human debate toward direct divine address.[40] This sets the stage for Yahweh's appearance, as Elihu's descriptions of stormy phenomena echo the whirlwind from which God speaks (Job 37:1–5; 38:1).[40] The divine speeches commence in Job 38:1, with Yahweh addressing Job from a whirlwind in two extended discourses (Job 38:1–40:2 and 40:6–41:34), shifting the focus from human argumentation to a majestic display of creation's order. The first speech consists of rapid-fire rhetorical questions that underscore human limitations against divine wisdom in forming the cosmos. Yahweh queries Job's presence at the earth's founding: "Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know! Or who stretched the line upon it?" (Job 38:4–5). These evoke the primordial act of creation, emphasizing God's sole agency in establishing boundaries, such as confining the sea behind doors (Job 38:8–11) and regulating dawn, stars, and weather phenomena (Job 38:12–38).[41] The speech continues with questions about untamed animals, illustrating God's provision for creatures beyond human control, including mountain goats, wild donkeys, ostriches, horses, hawks, and eagles (Job 39:1–30). This catalog highlights the wild freedom and instinctive behaviors under divine oversight, contrasting Job's ordered moral expectations with the universe's broader, incomprehensible harmony (Job 39:13–18, 26–30).[41] After Job's initial reply, the second speech intensifies, challenging Job to match divine power in clothing himself with splendor (Job 40:9–14) before describing two primordial beasts: Behemoth, a massive land creature with strength like the cedar in its tail, feeding on grass yet unassailable by humans (Job 40:15–24); and Leviathan, a fire-breathing sea monster armored invincibly, with flashing eyes and mouth like a furnace, reigning as king over the proud (Job 41:1–34). These figures symbolize chaos forces subdued by God at creation, affirming divine mastery over disorder without human intervention.[15] Job responds twice to these speeches, marking his progression toward humility. After the first discourse, he declares, "See, I am of small account; what shall I answer you? I lay my hand on my mouth" (Job 40:3–5), acknowledging his inadequacy in silent submission. Following the second, Job confesses, "I know that you can do all things, and that no purpose of yours can be thwarted... Therefore I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes" (Job 42:2–6), recanting his earlier demands and embracing repentance.[42] Structurally, Elihu's speeches and the divine responses form a pivotal bridge from the friends' failed explanations to the book's resolution, elevating the discourse beyond human limits to reveal the incomprehensibility of God's ordered world, where suffering fits into a vast, sovereign design.[40] Elihu's emphasis on divine discipline through nature anticipates Yahweh's cosmic tour, underscoring that true wisdom lies in awe rather than resolution (Job 37:24; 42:3).[41][40]Epilogue and Resolution

In the epilogue of the Book of Job, following the divine speeches, God addresses Eliphaz the Temanite and his companions, expressing anger at them for not speaking truthfully about Him, in contrast to Job, whom God vindicates as His servant who has spoken correctly.[43] God instructs the three friends to take seven bulls and seven rams, offer a burnt offering for themselves, and have Job pray on their behalf, assuring that He will accept Job's intercession and not treat them according to their folly.[44] The friends comply, and God accepts Job's prayer for them, thereby granting divine forgiveness through Job's intercession.[45] Job's restoration begins after this act of prayer, as the Lord turns his captivity and restores his fortunes, doubling what he had lost in the initial calamities.[46] The Lord blesses the latter part of Job's life more than the former, granting him 14,000 sheep, 6,000 camels, 1,000 yoke of oxen, and 1,000 female donkeys—precisely double his original possessions.[47] Job also receives a new family: seven sons and three daughters, whose names are Jemimah, Keziah, and Keren-happuch, described as more beautiful than any women in the land.[48] Unusually, these daughters inherit a share alongside their brothers, highlighting their prominence in the restoration.[49] This narrative symmetry with the prologue underscores the completeness of Job's reversal, mirroring the initial losses with equivalent or enhanced recoveries.[50] Job lives an additional 140 years after these events, long enough to see his children, grandchildren, and four generations of descendants.[51] He dies at an advanced age, described as old and full of days, bringing the prose frame of the story to a close.[52] In the Septuagint version, an additional epilogue follows verse 17, identifying Job with Jobab from Esau's genealogy in Genesis 36 and providing further details on his lineage as the fifth generation from Abraham, his Edomite connections, and a note on his future resurrection among the righteous.[53]Core Themes

Theodicy and the Problem of Suffering

The Book of Job grapples with the profound theological dilemma of theodicy, particularly the question of why the righteous endure undeserved suffering, as exemplified by Job's catastrophic losses of family, wealth, and health despite his described blamelessness and uprightness.[54] This narrative challenges the conventional doctrine of retribution, which posits that divine justice rewards the good and punishes the wicked in direct proportion to their deeds, a principle echoed in texts like Deuteronomy 28.[55] Job's plight thus raises the acute problem of reconciling God's omnipotence and benevolence with the reality of innocent affliction, a tension that permeates the dialogues and underscores the limits of human reasoning in comprehending divine purposes.[56] Job's three friends—Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar—represent a traditional retributive framework, insisting that suffering must stem from hidden sin or moral failing, and they repeatedly exhort Job to confess and repent to restore harmony with God.[54] For instance, Eliphaz asserts that those who plow iniquity reap the same, implying Job's calamities are punitive consequences of undisclosed wrongdoing (Job 4:8).[55] In stark contrast, Job vehemently defends his innocence throughout his monologues, rejecting the friends' mechanistic view of divine justice as overly simplistic and even accusatory toward God, whom he portrays as an arbitrary sovereign who crushes the righteous without cause (Job 9:22).[56] This debate highlights a core rift: the friends' punitive interpretation versus Job's insistence on suffering's inscrutability, which defies easy moral categorization and exposes the inadequacy of retribution theology in addressing existential pain.[54] The book's resolution offers no explicit resolution to the theodicy question, as God's speeches from the whirlwind (Job 38–41) bypass Job's pleas for justification, instead emphasizing the vastness of divine wisdom and the mysteries of creation, such as the ordering of sea and stars, to affirm God's unchallenged authority over chaos without detailing why suffering occurs.[55] Job responds with humbled submission, acknowledging his own limitations in dust and ashes (Job 42:6), yet the absence of a direct answer leaves the problem of innocent suffering ambiguously suspended, suggesting that full comprehension eludes human grasp and that trust in divine sovereignty must suffice amid unresolved affliction.[54] This open-endedness critiques simplistic explanations while inviting a posture of lament and awe.[56] In broader theodicy, Job's narrative resonates with post-exilic Jewish experiences of collective suffering, paralleling laments in Psalms 73 where the psalmist wrestles with the prosperity of the wicked and the affliction of the godly, ultimately finding solace in divine presence rather than retribution.[54] Scholars note that the book's emphasis on suffering as a test of faith, rather than punishment, influences later theological reflections on evil's coexistence with a just God, prioritizing relational fidelity over causal explanations.[56]Divine Sovereignty and Human Limitations

The Book of Job portrays divine sovereignty through God's direct speeches in chapters 38–41, where God asserts unchallenged authority over creation by interrogating Job about the mysteries of the cosmos, such as the foundations of the earth, the boundaries of the sea, and the governance of celestial bodies. These rhetorical questions emphasize God's role as the sole architect and sustainer of the natural order, highlighting phenomena like the orchestration of stars and the regulation of weather patterns as evidence of omnipotent control beyond human grasp.[57] God's invocation of majestic creatures, including the taming of sea monsters like Leviathan and the might of Behemoth, further underscores this sovereignty as an exercise of raw creative power that defies human categorization or mastery.[58] A central critique of human hubris emerges in the rebuke of Job's insistent demands for an explanation of his suffering, as God's whirlwind address in Job 38:1–3 confronts Job's presumption by questioning his limited knowledge and inability to replicate even basic acts of creation, such as binding the Pleiades or loosing the cords of Orion. This theophany from the whirlwind serves as a motif symbolizing the chaotic yet divinely ordered forces of nature, where God's voice overwhelms human reasoning and enforces epistemic humility.[59] Similarly, Elihu's speeches in chapters 32–37 precede this divine intervention by extolling God's transcendence, portraying the deity as utterly independent and inscrutable, whose justice operates on a plane far removed from human comprehension or moral expectations.[60] Elihu argues that God's purposes transcend mortal judgment, as seen in descriptions of divine oversight of nations and natural elements that evade human insight. Theologically, the Book of Job implies that divine sovereignty is not contingent upon alignment with human ethical frameworks; instead, it demands trust in God's profound wisdom, even amid inexplicable adversity, as Job's eventual submission in chapter 42 acknowledges the limits of his understanding without receiving a direct rationale for his trials. This motif of rhetorical interrogation—probing the intricacies of the animal kingdom, geological formations, and atmospheric phenomena—reinforces the theme that human limitations preclude full apprehension of divine intentions, fostering a posture of reverence over rational mastery.[61] Such depictions distinguish God's authority as absolute, inviting reflection on the vastness of creation as a testament to unassailable power.[62]Wisdom, Retribution, and Moral Order

The Book of Job engages deeply with ancient Near Eastern and Israelite wisdom traditions, portraying wisdom not as a humanly attainable commodity but as an elusive divine mystery. In chapter 28, a poetic interlude known as the "Hymn to Wisdom," the text describes exhaustive human efforts—such as mining precious metals from the earth—to uncover wisdom, yet concludes that it resides beyond human reach, hidden in God's domain.[63] This hymn culminates in the declaration that "the fear of the Lord, that is wisdom, and to depart from evil is understanding" (Job 28:28), echoing proverbial wisdom while emphasizing reverence and ethical living as the closest approximations to divine insight, rather than intellectual mastery.[64] Central to the book's critique is the doctrine of retribution espoused by Job's friends—Eliphaz, Bildad, and Zophar—who insist that prosperity rewards the righteous and suffering punishes the wicked, a view rooted in traditional wisdom teachings.[55] They repeatedly urge Job to confess hidden sins as the cause of his afflictions, assuming a strict moral causality where divine justice operates mechanistically.[65] However, the narrative undermines this doctrine through Job's proclaimed innocence—he maintains his integrity throughout the dialogues—and his eventual restoration without explicit repentance for wrongdoing, revealing the friends' framework as overly simplistic and inadequate for real human experience.[66] This subversion extends to a broader challenge of Proverbs-like formulas that promise direct correlations between virtue and reward, affirming instead a more nuanced divine justice that transcends predictable ethical retribution. The book posits that moral order exists but defies human categorization, as suffering and blessing do not always align with observable righteousness, thus complicating the retributive paradigm without rejecting divine goodness outright.[67] Such complexity highlights the limits of human wisdom in comprehending God's ways, a theme resonant with but distinct from explorations of divine incomprehensibility elsewhere in the text. Intertextually, Job positions itself within the wisdom corpus alongside Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes), both expressing skepticism toward facile retributive ethics and the attainability of wisdom amid life's vanities. While Proverbs upholds a confident moral order, Job and Qoheleth echo each other in questioning why the righteous suffer and the wicked prosper, fostering a shared debate on wisdom's elusive nature in an unpredictable world.[68][69]Interpretations and Reception

Ancient and Medieval Jewish and Christian Views

In ancient Jewish tradition, the Book of Job was interpreted both as a historical account and as a parable designed to explore profound theological questions. The Talmud debates Job's historicity, with some rabbis placing him in the time of Abraham or Moses, while others, such as Rabbi Johanan, regard the narrative as a mashal (parable) to illustrate the problem of undeserved suffering and divine justice. This dual perspective is echoed in midrashic literature, where Job serves as an exemplar of piety amid trial, though his exact identity remains contested.[70] Medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides further developed this parabolic reading in his Guide of the Perplexed (3:22), portraying Job as a fictional construct to demonstrate the limits of human comprehension regarding divine providence. Maimonides argues that Job initially errs by attributing anthropomorphic motives to God, but ultimately recognizes the hiddenness (hester panim) of divine actions, which transcend rational explanation and affirm God's ultimate goodness despite apparent injustice.[71] This philosophical approach reconciles the text with Aristotelian principles of causation while emphasizing humility before the ineffable divine will.[72] Early Christian interpreters adopted allegorical methods to view the Book of Job through a Christological lens, seeing Job's suffering as prefiguring the soul's purification and Christ's passion. Origen of Alexandria, in his homilies and exegetical works, interpreted Job's trials as symbolic of the soul's spiritual ascent, where afflictions serve as divine pedagogy to cleanse impurities and draw the believer closer to God.[73] Gregory the Great's Moralia in Job (c. 578–595 CE), a monumental patristic commentary, expands this by moralizing the text: Job embodies patient endurance (patientia) under tribulation, offering ethical guidance for Christians facing persecution, with each verse unpacked in threefold layers—literal, allegorical, and moral—to instruct on virtue and humility.[74] In the medieval period, Christian exegesis integrated scholastic philosophy, as seen in Thomas Aquinas's Expositio super Job ad litteram (c. 1260s), which employs Aristotelian ethics to analyze retribution and providence. Aquinas views Job's restoration as affirming a balanced moral order where suffering tests and perfects virtues like fortitude, while God's speeches underscore human reason's subordination to divine wisdom, bridging faith and natural philosophy.[75] Complementing this, Jewish commentator Rashi (1040–1105) provided a literal-historical reading in his Torah commentary extension to Job, treating the protagonist as a real figure from patriarchal times and clarifying linguistic obscurities to emphasize straightforward piety over speculative allegory.[76] The Book of Job also held liturgical significance in both traditions. In Judaism, excerpts appear in High Holiday prayers (e.g., Job 1:21 in the Amidah) and mourning rituals like Shivah, reinforcing themes of submission to divine decree during communal lamentation.[77] In Christianity, selections from Job feature prominently in Holy Week liturgies, including readings during the Easter Vigil in some Eastern rites and the Roman Office of Tenebrae, where Job's laments parallel Christ's suffering and invite reflection on redemptive endurance.[78]Modern Scholarly and Theological Interpretations

Modern scholarship on the Book of Job has employed historical-critical methods to dissect its composition, often proposing that the Elihu speeches (Job 32–37) represent a later insertion into the original text. Scholars such as David J.A. Clines argue that these speeches disrupt the narrative flow between Job's final lament and God's response, exhibiting stylistic differences like Aramaisms and repetitive didacticism that suggest an editorial addition from a post-exilic period, possibly to soften the book's radical challenge to retributive justice.[79] Form criticism further analyzes the dialogues as a composite of genres, including wisdom controversy, lament, and lawsuit, with Claus Westermann identifying the central poetic core as a debate that integrates protest laments against the friends' conventional wisdom teachings, highlighting the book's innovative blend of subgenres to explore suffering beyond traditional explanations.[80] Theological interpretations in the 19th and 20th centuries shifted toward existential and revelatory emphases, exemplified by Søren Kierkegaard's reading of Job as a paradigm of the "leap of faith." In works like Repetition and his discourses on Job, Kierkegaard portrays Job's unwavering devotion amid absurdity not as rational theodicy but as doxological surrender, where faith transcends ethical reasoning and embraces the paradox of divine hiddenness, influencing existential theology by framing suffering as a call to absurd trust in God.[81] Similarly, Karl Barth interprets Job in Church Dogmatics as a witness to divine freedom and revelation, rejecting moralistic justifications for suffering; Job's refusal to abandon God despite unanswered questions underscores that true obedience arises from encountering God's sovereign "wholly other" nature, prioritizing revelation over human reason or attempts at theodicy.[82] 20th- and 21st-century scholarship has increasingly focused on the Book of Job as a text of trauma and protest, drawing parallels to modern atrocities like the Holocaust. Elie Wiesel, in post-Holocaust reflections, views Job as an archetype of defiant questioning against divine silence, where the protagonist's unyielding protest mirrors survivors' struggles with meaningless suffering and absent justice, transforming the book into a resource for theological resistance rather than consolation.[83] Building on this, Carol Newsom's 2003 analysis in The Book of Job: A Contest of Moral Imaginations presents the dialogues as clashing "moral imaginations," with Job's voice self-involved in its fixation on personal innocence and retributive fairness, while the whirlwind speeches expose the limits of such anthropocentric frameworks, leaving interpreters to grapple with unresolved ethical tensions in a polyphonic narrative.[84] Debates persist over the epilogue's restoration of Job's fortunes (Job 42:7–17), with many scholars viewing it as ironic or subversive rather than a tidy resolution. Katharine Dell argues that the prose frame's reward motif undercuts the poetic core's radical critique of retribution, creating ironic dissonance that subverts simplistic piety and invites readers to question divine justice's alignment with human expectations.[85] This perspective aligns with broader post-2000 readings, such as those in The Book of Job: Aesthetics, Ethics, Hermeneutics (2017), which see the ending as deliberately ambiguous, reinforcing the book's protest against coercive moral orders by juxtaposing restoration with the unresolved divine mystery.[86] As of 2025, ongoing scholarship continues to explore these tensions, including digital hermeneutics applying computational analysis to Job's linguistic ambiguities in relation to contemporary ethical dilemmas.[87]Feminist and Postcolonial Perspectives