Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maser

View on Wikipedia

A maser is a device that produces coherent electromagnetic waves (microwaves), through amplification by stimulated emission. The term is an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. Nikolay Basov, Alexander Prokhorov and Joseph Weber introduced the concept of the maser in 1952, and Charles H. Townes, James P. Gordon, and Herbert J. Zeiger built the first maser at Columbia University in 1953. Townes, Basov and Prokhorov won the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics for theoretical work leading to the maser. Masers are used as timekeeping devices in atomic clocks, and as extremely low-noise microwave amplifiers in radio telescopes and deep-space spacecraft communication ground-stations.

Modern masers can be designed to generate electromagnetic waves at microwave frequencies and radio and infrared frequencies. For this reason, Townes suggested replacing "microwave" with "molecular" as the first word in the acronym "maser".[1]

The laser works by the same principle as the maser, but produces higher-frequency coherent radiation at visible wavelengths. The maser was the precursor to the laser, inspiring theoretical work by Townes and Arthur Leonard Schawlow that led to the invention of the laser in 1960 by Theodore Maiman. When the coherent optical oscillator was first imagined in 1957, it was originally called the "optical maser". This was ultimately changed to laser, for "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation". Gordon Gould is credited with creating this acronym in 1957.

History

[edit]The theoretical principles governing the operation of a maser were first described by Joseph Weber of the University of Maryland, College Park at the Electron Tube Research Conference in June 1952 in Ottawa,[2] with a summary published in the June 1953 Transactions of the Institute of Radio Engineers Professional Group on Electron Devices,[3] and simultaneously by Nikolay Basov and Alexander Prokhorov from Lebedev Institute of Physics, at an All-Union Conference on Radio-Spectroscopy held by the USSR Academy of Sciences in May 1952, published in October 1954.

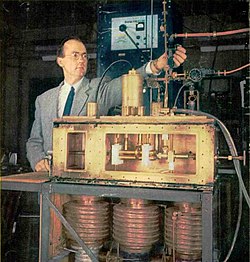

Independently, Charles Hard Townes, James P. Gordon, and H. J. Zeiger built the first ammonia maser at Columbia University in 1953. This device used stimulated emission in a stream of energized ammonia molecules to produce amplification of microwaves at a frequency of about 24.0 gigahertz.[4] Townes later worked with Arthur L. Schawlow to describe the principle of the optical maser, or laser,[5] of which Theodore H. Maiman created the first working model in 1960.

For their research in the field of stimulated emission, Townes, Basov and Prokhorov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1964.[6]

Technology

[edit]The maser is based on the principle of stimulated emission proposed by Albert Einstein in 1917. When atoms have been induced into an excited energy state, they can amplify radiation at a frequency particular to the element or molecule used as the masing medium (similar to what occurs in the lasing medium in a laser).

By putting such an amplifying medium in a resonant cavity, feedback is created that can produce coherent radiation.

Some common types

[edit]- Atomic beam masers

- Ammonia maser

- Free electron maser

- Hydrogen maser

- Gas masers

- Rubidium maser

- Liquid-dye and chemical laser

- Solid state masers

- Ruby maser

- Whispering-gallery modes iron-sapphire maser

- Dual noble gas maser (The dual noble gas of a masing medium which is nonpolar.[7])

21st-century developments

[edit]In 2012, a research team from the National Physical Laboratory and Imperial College London developed a solid-state maser that operated at room temperature by using optically pumped, pentacene-doped p-Terphenyl as the amplifier medium.[8][9][10] It produced pulses of maser emission lasting for a few hundred microseconds.

In 2018, a research team from Imperial College London and University College London demonstrated continuous-wave maser oscillation using synthetic diamonds containing nitrogen-vacancy defects.[11][12]

In 2025 a team from Northumbria University created a low-cost energy-efficient unit that works at room temperature and uses an LED as the source of emission.[13]

Uses

[edit]Masers serve as high precision frequency references. These "atomic frequency standards" are one of the many forms of atomic clocks. Masers were also used as low-noise microwave amplifiers in radio telescopes, though these have largely been replaced by amplifiers based on FETs.[14]

During the early 1960s, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory developed a maser to provide ultra-low-noise amplification of S-band microwave signals received from deep space probes.[15] This maser used deeply refrigerated helium to chill the amplifier down to a temperature of 4 kelvin. Amplification was achieved by exciting a ruby comb with a 12.0 gigahertz klystron. In the early years, it took days to chill and remove the impurities from the hydrogen lines.

Refrigeration was a two-stage process, with a large Linde unit on the ground, and a crosshead compressor within the antenna. The final injection was at 21 MPa (3,000 psi) through a 150 μm (0.006 in) micrometer-adjustable entry to the chamber. The whole system noise temperature looking at cold sky (2.7 kelvin in the microwave band) was 17 kelvin. This gave such a low noise figure that the Mariner IV space probe could send still pictures from Mars back to the Earth, even though the output power of its radio transmitter was only 15 watts, and hence the total signal power received was only −169 decibels with respect to a milliwatt (dBm).

Hydrogen maser

[edit]

The hydrogen maser is used as an atomic frequency standard. Together with other kinds of atomic clocks, these help make up the International Atomic Time standard ("Temps Atomique International" or "TAI" in French). This is the international time scale coordinated by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Norman Ramsey and his colleagues first conceived of the maser as a timing standard. More recent masers are practically identical to their original design. Maser oscillations rely on the stimulated emission between two hyperfine energy levels of atomic hydrogen.

Here is a brief description of how they work:

- First, a beam of atomic hydrogen is produced. This is done by submitting the gas at low pressure to a high-frequency radio wave discharge (see the picture on this page).

- The next step is "state selection"—in order to get some stimulated emission, it is necessary to create a population inversion of the atoms. This is done in a way that is very similar to the Stern–Gerlach experiment. After passing through an aperture and a magnetic field, many of the atoms in the beam are left in the upper energy level of the lasing transition. From this state, the atoms can decay to the lower state and emit some microwave radiation.

- A high Q factor (quality factor) microwave cavity confines the microwaves and reinjects them repeatedly into the atom beam. The stimulated emission amplifies the microwaves on each pass through the beam. This combination of amplification and feedback is what defines all oscillators. The resonant frequency of the microwave cavity is tuned to the frequency of the hyperfine energy transition of hydrogen: 1,420,405,752 hertz.[16]

- A small fraction of the signal in the microwave cavity is coupled into a coaxial cable and then sent to a coherent radio receiver.

- The microwave signal coming out of the maser is very weak, a few picowatts. The frequency of the signal is fixed and extremely stable. The coherent receiver is used to amplify the signal and change the frequency. This is done using a series of phase-locked loops and a high performance quartz oscillator.

Astrophysical masers

[edit]

Maser-like stimulated emission has also been observed in nature from interstellar space, and it is frequently called "superradiant emission" to distinguish it from laboratory masers. These emissions are observed from molecules such as water (H2O), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), methanol (CH3OH), formaldehyde (HCHO), silicon monoxide (SiO), and carbodiimide (HNCNH).[17] Water molecules in star-forming regions can undergo a population inversion and emit radiation at about 22.0 GHz, creating the brightest spectral line in the radio universe. Some water masers also emit radiation from a rotational transition at a frequency of 96 GHz.[18][19]

Extremely powerful masers, associated with active galactic nuclei, are known as megamasers and are up to a million times more powerful than stellar masers.

Terminology

[edit]The meaning of the term maser has changed slightly since its introduction. Initially the acronym was universally given as "microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation", which described devices which emitted in the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The principle and concept of stimulated emission has since been extended to more devices and frequencies. Thus, the original acronym is sometimes modified, as suggested by Charles H. Townes,[1] to "molecular amplification by stimulated emission of radiation." Some have asserted that Townes's efforts to extend the acronym in this way were primarily motivated by the desire to increase the importance of his invention, and his reputation in the scientific community.[20]

When the laser was developed, Townes and Schawlow and their colleagues at Bell Labs pushed the use of the term optical maser, but this was largely abandoned in favor of laser, coined by their rival Gordon Gould.[21] In modern usage, devices that emit in the X-ray through infrared portions of the spectrum are typically called lasers, and devices that emit in the microwave region and below are commonly called masers, regardless of whether they emit microwaves or other frequencies.

Gould originally proposed distinct names for devices that emit in each portion of the spectrum, including grasers (gamma ray lasers), xasers (x-ray lasers), uvasers (ultraviolet lasers), lasers (visible lasers), irasers (infrared lasers), masers (microwave masers), and rasers (RF masers). Most of these terms never caught on, however, and all have now become (apart from in science fiction) obsolete except for maser and laser.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Townes, Charles H. (1964-12-11). "Production of coherent radiation by atoms and molecules - Nobel Lecture" (PDF). The Nobel Prize. p. 63. Archived (pdf) from the original on 2020-08-27. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

We called this general type of system the maser, an acronym for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation. The idea has been successfully extended to such a variety of devices and frequencies that it is probably well to generalize the name - perhaps to mean molecular amplification by stimulated emission of radiation.

- ^ American Institute of Physics Oral History Interview with Weber

- ^ Mario Bertolotti (2004). The History of the Laser. CRC Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1420033403.

- ^ Gordon, J. P.; Zeiger, H. J.; Townes, C. H. (1955). "The Maser—New Type of Microwave Amplifier, Frequency Standard, and Spectrometer". Phys. Rev. 99 (4): 1264. Bibcode:1955PhRv...99.1264G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.99.1264.

- ^ Schawlow, A.L.; Townes, C.H. (15 December 1958). "Infrared and Optical Masers". Physical Review. 112 (6): 1940–1949. Bibcode:1958PhRv..112.1940S. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.112.1940.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1964". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 2020-08-27.

- ^ The Dual Noble Gas Maser, Harvard University, Department of Physics

- ^ Brumfiel, G. (2012). "Microwave laser fulfills 60 years of promise". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11199. S2CID 124247048.

- ^ Palmer, Jason (16 August 2012). "'Maser' source of microwave beams comes out of the cold". BBC News. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Microwave Laser Fulfills 60 Years of Promise

- ^ Liu, Ren-Bao (March 2018). "A diamond age of masers". Nature. 555 (7697): 447–449. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..447L. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-03215-3. PMID 29565370.

- ^ Scientists use diamond in world's first continuous room-temperature solid-state maser, phys.org

- ^ Long, Sophia; Lopez, Lisa; Ford, Bethan; Balembois, François; Montis, Riccardo; Ng, Wern; Arroo, Daan M.; Alford, Neil McN; Torun, Hamdi; Sathian, Juna (2025-07-09). "LED-pumped room-temperature solid-state maser". Communications Engineering. 4 (1) 122: 1–7. doi:10.1038/s44172-025-00455-w. ISSN 2731-3395. PMC 12241473. PMID 40634466.

- ^ "Low Noise Amplifiers – Pushing the limits of low noise". National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO).

- ^ Macgregor S. Reid, ed. (2008). "Low-Noise Systems in the Deep Space Network" (PDF). JPL.

- ^ "Time and Frequency From A to Z: H". NIST. 12 May 2010.

- ^ McGuire, Brett A.; Loomis, Ryan A.; Charness, Cameron M.; Corby, Joanna F.; Blake, Geoffrey A.; Hollis, Jan M.; Lovas, Frank J.; Jewell, Philip R.; Remijan, Anthony J. (2012-10-20). "Interstellar Carbodiimide (HNCNH): A New Astronomical Detection from the GBT Primos Survey Via Maser Emission Features". The Astrophysical Journal. 758 (2): L33. arXiv:1209.1590. Bibcode:2012ApJ...758L..33M. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/758/2/L33. ISSN 2041-8205. S2CID 26146516.

- ^ Neufeld, David A.; Melnick, Gary J. (1991). "Excitation of Millimeter and Submillimeter Water Masers in Warm Astrophysical Gas". Atoms, Ions and Molecules: New Results in Spectral Line Astrophysics, ASP Conference Series (ASP: San Francisco). 16: 163. Bibcode:1991ASPC...16..163N.

- ^ Tennyson, Jonathan; et al. (March 2013). "IUPAC critical evaluation of the rotational–vibrational spectra of water vapor, Part III: Energy levels and transition wavenumbers for H216O". Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer. 117: 29–58. Bibcode:2013JQSRT.117...29T. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2012.10.002. hdl:10831/91303.

- ^ Taylor, Nick (2000). LASER: The inventor, the Nobel laureate, and the thirty-year patent war. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-83515-0.

- ^ Taylor, Nick (2000). LASER: The inventor, the Nobel laureate, and the thirty-year patent war. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 66–70. ISBN 978-0-684-83515-0.

Further reading

[edit]- J.R. Singer, Masers, John Whiley and Sons Inc., 1959.

- J. Vanier, C. Audoin, The Quantum Physics of Atomic Frequency Standards, Adam Hilger, Bristol, 1989.

External links

[edit]- The Feynman Lectures on Physics Vol. III Ch. 9: The Ammonia Maser

- arXiv.org search for "maser"

- "The Hydrogen Maser Clock Project". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Archived from the original on 2006-10-10.

- Bright Idea: The First Lasers Archived 2014-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Invention of the Maser and Laser, American Physical Society

- Shawlow and Townes Invent the Laser, Bell Labs

Maser

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Principles

A maser, standing for Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation, is a device that generates or amplifies coherent electromagnetic waves in the microwave spectrum by exploiting the quantum process of stimulated emission in a suitable medium, such as atoms or molecules.[5] This amplification produces highly monochromatic and phase-coherent output, distinguishing masers from incoherent microwave sources like thermal emitters.[1] The fundamental physics of masers relies on interactions between photons and matter at the quantum level, where atoms or molecules possess discrete energy levels. An atom in a lower energy state (level 1) can absorb a photon of energy (where is Planck's constant and is frequency) to transition to a higher state (level 2), known as induced absorption. Conversely, an excited atom in level 2 can decay to level 1 either spontaneously, emitting a random photon in an arbitrary direction (spontaneous emission), or be induced by an incident photon of matching energy to emit a second photon that is identical in phase, frequency, and direction (stimulated emission).[6] These processes are governed by Einstein's coefficients: for absorption rate per unit energy density , for stimulated emission, and for spontaneous emission, with the relations (where and are the degeneracies of levels 1 and 2) and derived from thermal equilibrium assumptions.[7] For net amplification in a maser, a population inversion must be achieved, where more atoms occupy the upper energy level than the lower one, adjusted for degeneracy: specifically, the condition (with and as populations) ensures that the stimulated emission rate exceeds the absorption rate, leading to exponential growth of the electromagnetic field.[7] This inversion is unstable in thermal equilibrium and requires external "pumping" to maintain, enabling the maser to function as a low-noise amplifier or oscillator. Masers typically operate over wavelengths from 1 mm to 1 m, corresponding to microwave frequencies of 300 GHz to 300 MHz.[8]Relation to Lasers

Maser and laser technologies share fundamental operational principles, both relying on stimulated emission of radiation to produce coherent electromagnetic waves. In both devices, population inversion is achieved in an active medium to enable amplification, and a resonant cavity provides feedback to sustain oscillation, ensuring high spatial and temporal coherence. These shared mechanisms were first demonstrated in the maser and later extended to higher frequencies in the laser, as proposed in the seminal theoretical framework for optical masers.[9] Despite these similarities, masers and lasers differ significantly in their operational characteristics, primarily due to the wavelength regimes they target. Masers operate in the microwave portion of the spectrum, typically requiring gaseous or solid-state media at cryogenic temperatures to maintain population inversion, and they produce lower power outputs with exceptional frequency stability suitable for precision applications. In contrast, lasers function in the visible, infrared, or ultraviolet ranges, utilizing a broader array of media including semiconductors that often operate at room temperature, enabling higher power outputs for diverse uses.[2] The maser served as the direct precursor to the laser, providing the proof-of-concept for coherent amplification that inspired the development of optical devices. Charles Townes and his collaborators built the first maser in 1953, and by 1958, Townes and Arthur Schawlow outlined the principles for extending maser techniques to infrared and optical wavelengths, dubbing the resulting device an "optical maser"—a term that persisted until "laser" was coined to distinguish it from microwave counterparts. This evolutionary progression positioned masers as the foundational technology in quantum electronics, paving the way for lasers' widespread adoption.[1][10]| Aspect | Maser | Laser |

|---|---|---|

| Output Frequency | Microwave (typically 1–100 GHz) | Optical (typically 100 THz – 1 PHz) |

| Coherence Length | Extremely long (often >1 km, enabling atomic clocks) | Variable (typically 1 m to several km, depending on type) |

| Common Applications | Frequency standards, low-noise amplification in radio astronomy | Material processing (e.g., cutting/welding), optical communications, medical procedures |

Historical Development

Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical foundations of the maser trace back to early 20th-century quantum theory, particularly Albert Einstein's seminal 1917 paper "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung," where he introduced the concept of stimulated emission as a counterpart to spontaneous emission and absorption.[11] Einstein postulated that an excited atom could be triggered by an incoming photon to emit a second photon of identical frequency, phase, and direction, leading to coherent amplification of radiation; he derived the relationships between the Einstein coefficients A (spontaneous emission), B (stimulated emission and absorption), and showed their balance in thermal equilibrium via Planck's law. This work extended quantum ideas to radiation processes, but stimulated emission was initially overshadowed by the dominance of spontaneous emission in observable phenomena.[11] Despite its elegance, Einstein's prediction of stimulated emission received little attention for over three decades, as experimental techniques at the time focused on absorption and fluorescence, where stimulated effects were negligible due to low photon densities and thermal populations favoring ground states. The concept languished amid the rapid advancements in quantum mechanics during the 1920s and 1930s, which prioritized wave functions and uncertainty principles over radiation-matter interactions at high frequencies. It was not until the mid-20th century, with improved understanding of atomic energy levels and electromagnetic interactions, that stimulated emission reemerged as a viable mechanism for amplification. Post-World War II developments in radar and microwave technology provided crucial electromagnetic infrastructure, including high-Q cavity resonators that could sustain microwaves with minimal losses and precise frequency control. These resonators, refined from wartime applications like the cavity magnetron, enabled theoretical explorations of low-noise amplification by confining electromagnetic fields to interact selectively with atomic or molecular systems. Concurrently, the concept of negative resistance—where an active medium absorbs less power than it supplies at certain frequencies—gained traction in microwave theory, offering a pathway to oscillators and amplifiers beyond vacuum tubes; this arose from analyses showing how inverted populations could yield effective negative conductance in resonant circuits. Pioneering work on molecular beams by physicists such as Isidor Isaac Rabi and Norman F. Ramsey in the 1930s and 1940s laid essential groundwork for applying quantum transitions to microwave regimes. Rabi, a Columbia University professor, developed the molecular beam resonance method in 1937, using magnetic fields to measure hyperfine splittings in atoms and molecules with unprecedented precision, revealing inversion doublets in species like ammonia that would later prove ideal for stimulated emission. Ramsey, collaborating with Rabi during the 1940s at Harvard and MIT Radiation Laboratory, advanced this through separated oscillatory fields, theoretically enabling coherent manipulation of beam states over longer paths and minimizing Doppler broadening—concepts that theoretically supported feedback mechanisms for sustained emission. Charles H. Townes, influenced by Rabi as his doctoral advisor, began exploring microwave spectroscopy in the late 1940s at Bell Laboratories, theoretically linking molecular energy levels to cavity interactions for potential low-temperature amplification. Central theoretical challenges involved achieving population inversion, where more particles occupy higher energy states than lower ones, defying Boltzmann thermal distribution and enabling stimulated emission to exceed absorption. In equilibrium, thermal noise—governed by the Nyquist theorem—populates lower states preferentially, leading to net absorption; theorists proposed optical or RF pumping to selectively excite molecules into metastable states, creating inversion while avoiding rapid decay. Another hurdle was suppressing thermal fluctuations in cavities, where blackbody radiation at room temperature generates noise equivalent to thousands of quanta per mode, theoretically limiting sensitivity; inversion promised quantum-limited noise, approaching the standard quantum limit for phase-insensitive amplification. These ideas, rooted in quantum statistical mechanics, highlighted the need for selective state preparation to realize negative absorption without excessive heating.Invention and Early Milestones

The first maser was successfully operated in April 1954 by Charles H. Townes, James P. Gordon, and Herbert J. Zeiger at Columbia University in New York.[1] This device, known as the ammonia maser, employed a beam of ammonia molecules passing through a microwave cavity, where stimulated emission amplified signals at a frequency of about 23.8 GHz, demonstrating coherent microwave generation for the first time.[12] The invention built on theoretical predictions of stimulated emission but required innovative engineering, such as using inhomogeneous electric fields to focus excited ammonia molecules into the cavity while defocusing those in lower energy states.[13] Parallel to Townes's work, Soviet physicists Nikolai G. Basov and Aleksandr M. Prokhorov at the P.N. Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow pursued similar ideas, publishing proposals in 1954 and 1955 for molecular beam masers and, crucially, a three-level pumping scheme that facilitated population inversion in solids.[14] Their 1955 work laid the groundwork for solid-state masers by suggesting optical or electrical pumping to achieve inversion without relying solely on molecular beams, enabling more compact devices.[15] These independent efforts highlighted the global race in quantum electronics during the early Cold War era. The groundbreaking contributions of Townes, Basov, and Prokhorov were recognized with the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded for "fundamental work in the field of quantum electronics, which has led to the construction of oscillators and amplifiers based on the maser-laser principle."[15] This accolade underscored the maser's role as a precursor to lasers and its impact on precision technology. Early maser development encountered significant technical hurdles, including the necessity for cryogenic cooling in solid-state variants to minimize thermal noise and achieve stable population inversion, often requiring liquid helium temperatures around 4 K.[16] Beam focusing techniques also posed challenges, as imprecise separation of excited and ground-state molecules reduced efficiency; solutions involved refined quadrupole electric fields and resonant cavity designs to enhance signal amplification.[13]| Year | Key Event | Inventors/Contributors | Maser Variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | First operational maser | Charles H. Townes, James P. Gordon, Herbert J. Zeiger | Ammonia gas maser |

| 1955 | Proposal of three-level pumping scheme for solids | Nikolai G. Basov, Aleksandr M. Prokhorov | Solid-state maser concepts |

| 1957 | Development of ruby-based maser | Chihiro Kikuchi et al. | Ruby maser |

| 1964 | Nobel Prize in Physics awarded | Charles H. Townes, Nikolai G. Basov, Aleksandr M. Prokhorov | Quantum electronics (maser foundations) |