Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mobile telephony

View on Wikipedia

This article needs to be updated. (May 2025) |

| Part of a series on the |

| Wireless network technologies |

|---|

|

| Analog |

| Digital |

| Mobile telecommunications |

Mobile telephony is the provision of wireless telephone services to mobile phones, distinguishing it from fixed-location telephony provided via landline phones. Traditionally, telephony specifically refers to voice communication, though the distinction has become less clear with the integration of additional features such as text messaging and data services.

Modern mobile phones connect to a terrestrial cellular network of base stations (commonly referred to as cell sites), using radio waves to facilitate communication. Satellite phones use wireless links to orbiting satellites, providing an alternative in areas lacking local terrestrial communication infrastructure, such as landline and cellular networks. Cellular networks, satellite networks, and landline systems are all linked to the public switched telephone network (PSTN), enabling calls to be made to and from nearly any telephone worldwide.

As of 2010, global estimates indicated approximately five billion mobile cellular subscriptions, highlighting the significant role of mobile telephony in global communication systems.

History

[edit]According to internal memos, American Telephone & Telegraph discussed developing a wireless phone in 1915, but were afraid that deployment of the technology could undermine its monopoly on wired service in the U.S.[1]

Public mobile phone systems were first introduced in the years after the Second World War and made use of technology developed before and during the conflict. The first system opened in St. Louis, Missouri, United States in 1946 whilst other countries followed in the succeeding decades. The UK introduced its 'System 1' manual radiotelephone service as the South Lancashire Radiophone Service in 1958.[2] Calls were made via an operator using handsets identical to ordinary phone handsets.[3] The phone itself was a large box located in the boot (trunk) of the vehicle containing valves and other early electronic components. Although an uprated manual service ('System 3') was extended to cover most of the UK, automation did not arrive until 1981 with 'System 4'. Although this non-cellular service, based on German B-Netz technology, was expanded rapidly throughout the UK between 1982 and 1985 and continued in operation for several years before finally closing in Scotland, it was overtaken by the introduction in January 1985 of two cellular systems - the British Telecom/Securicor 'Cellnet' service and the Racal/Millicom/Barclays 'Vodafone' (from voice + data + phone) service. These cellular systems were based on US Advanced Mobile Phone Service (AMPS) technology, the modified technology being named Total Access Communication System (TACS).

In 1947, Bell Labs was the first to propose a cellular radio telephone network. The primary innovation was the development of a network of small overlapping cell sites supported by a call switching infrastructure that tracks users as they move through a network and passes their calls from one site to another without dropping the connection. In 1956, the MTA system was launched in Sweden. The early efforts to develop mobile telephony faced two significant challenges: allowing a great number of callers to use the comparatively few available frequencies simultaneously and allowing users to seamlessly move from one area to another without having their calls dropped. Both problems were solved by Bell Labs employee Amos Joel who, in 1970 applied for a patent for a mobile communications system.[4] However, a business consulting firm calculated the entire U.S. market for mobile telephones at 100,000 units and the entire worldwide market at no more than 200,000 units based on the ready availability of pay telephones and the high cost of constructing cell towers. As a consequence, Bell Labs concluded that the invention was "of little or no consequence," leading it not to attempt to commercialize the invention. The invention earned Joel induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2008.[5]

The development of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) large-scale integration (LSI) technology, information theory and cellular networking led to the development of affordable mobile communications.[6] The first call on a handheld mobile phone was made on April 3, 1973, by Martin Cooper, then of Motorola[7] to his opposite number in Bell Labs who were also racing to be first. Bell Labs went on to install the first trial cellular network in Chicago in 1978. This trial system was licensed by the FCC to ATT for commercial use in 1982 and, as part of the divestiture arrangements for the breakup of ATT, the AMPS technology was distributed to local telcos. The first commercial system opened in Chicago in October 1983.[8][9] A system designed by Motorola also operated in the Washington D.C./Baltimore area from summer 1982 and became a full public service later the following year.[10] Japan's first commercial radiotelephony service was launched by NTT in 1979.

The first fully automatic first generation cellular system was the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system, simultaneously launched in 1981 in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.[11] NMT was the first mobile phone network featuring international roaming. The Swedish electrical engineer Östen Mäkitalo started to work on this vision in 1966, and is considered as the father of the NMT system and some also consider him the father of the cellular phone.[12][13]

There was a rapid growth of wireless telecommunications towards the end of the 20th century, primarily due to the introduction of digital signal processing in wireless communications, driven by the development of low-cost, very large-scale integration (VLSI) RF CMOS (radio-frequency complementary MOS) technology.[6]

In 1990, AT&T Bell Labs engineers Jesse Russell, Farhad Barzegar and Can A. Eryaman filed a patent for a digital mobile phone that supports the transmission of digital data. Their patent was cited several years later by Nokia and Motorola when they were developing 2G digital mobile phones.[14]

In 1991, WiLAN founders Hatim Zaghloul and Michel Fattouche invented wideband orthogonal frequency-division multiplexing (WOFDM), the basis for wideband wireless communication applications,[15] including 4G mobile communications.[16]

The advent of cellular technology encouraged European countries to co-operate in the development of a pan-European cellular technology to rival those of the US and Japan. This resulted in the GSM system, the initials originally from the Groupe Spécial Mobile that was charged with the specification and development tasks but latterly as the 'Global System for Mobile Communications'. The GSM standard eventually spread outside Europe and is now the most widely used cellular technology in the world and the de facto standard. The industry association, the GSMA, now represents 219 countries and nearly 800 mobile network operators.[17] There are now estimated to be over 5 billion phone subscriptions according to the "List of countries by number of mobile phones in use" (although some users have multiple subscriptions, or inactive subscriptions), which also makes the mobile phone the most widely spread technology and the most common electronic device in the world.[18]

The first mobile phone to enable internet connectivity and wireless email, the Nokia Communicator, was released in 1996, creating a new category of multi-use devices called smartphones. In 1999 the first mobile internet service was launched by NTT DoCoMo in Japan under the i-Mode service. By 2007 over 798 million people around the world accessed the internet or equivalent mobile internet services such as WAP and i-Mode at least occasionally using a mobile phone rather than a personal computer.

Cellular systems

[edit]

Mobile phones receive and send radio signals with any number of cell site base stations fitted with microwave antennas. These sites are usually mounted on a tower, pole or building, located throughout populated areas, then connected to a cabled communication network and switching system. The phones have a low-power transceiver that transmits voice and data to the nearest cell sites, normally not more than 8 to 13 km (approximately 5 to 8 miles) away. In areas of low coverage, a cellular repeater may be used, which uses a long-distance high-gain dish antenna or yagi antenna to communicate with a cell tower far outside of normal range, and a repeater to rebroadcast on a small short-range local antenna that allows any cellphone within a few meters to function properly.

When the mobile phone or data device is turned on, it registers with the mobile telephone exchange, or switch, with its unique identifiers, and can then be alerted by the mobile switch when there is an incoming telephone call. The handset constantly listens for the strongest signal being received from the surrounding base stations, and is able to switch seamlessly between sites. As the user moves around the network, the "handoffs" are performed to allow the device to switch sites without interrupting the call.

Cell sites have relatively low-power (often only one or two watts) radio transmitters which broadcast their presence and relay communications between the mobile handsets and the switch. The switch in turn connects the call to another subscriber of the same wireless service provider or to the public telephone network, which includes the networks of other wireless carriers. Many of these sites are camouflaged to blend with existing environments, particularly in scenic areas.

The dialogue between the handset and the cell site is a stream of digital data that includes digitised audio (except for the first generation analog networks). The technology that achieves this depends on the system which the mobile phone operator has adopted. The technologies are grouped by generation. The first-generation systems started in 1979 with Japan, are all analog and include AMPS and NMT. Second-generation systems, started in 1991 in Finland, are all digital and include GSM, CDMA and TDMA.

The GSM standard is a European initiative expressed at the CEPT ("Conférence Européenne des Postes et Telecommunications", European Postal and Telecommunications conference). The Franco-German R&D cooperation demonstrated the technical feasibility, and in 1987 a Memorandum of Understanding was signed between 13 European countries who agreed to launch a commercial service by 1991. The first version of the GSM (=2G) standard had 6,000 pages. The IEEE/RSE awarded to Thomas Haug and Philippe Dupuis the 2018 James Clerk Maxwell medal for their contributions to the first digital mobile telephone standard.[19] In 2018, the GSM was used by over 5 billion people in over 220 countries. The GSM (2G) has evolved into 3G, 4G and 5G. The standardisation body for GSM started at the CEPT Working Group GSM (Group Special Mobile) in 1982 under the umbrella of CEPT. In 1988, ETSI was established and all CEPT standardization activities were transferred to ETSI. Working Group GSM became the Technical Committee GSM. In 1991, it became the Technical Committee SMG (Special Mobile Group) when ETSI tasked the committee with UMTS (3G).

The nature of cellular technology renders many phones vulnerable to 'cloning': anytime a cell phone moves out of coverage (for example, in a road tunnel), when the signal is re-established, the phone sends out a 're-connect' signal to the nearest cell-tower, identifying itself and signalling that it is again ready to transmit. With the proper equipment, it is possible to intercept the re-connect signal and encode the data it contains into a 'blank' phone—in all respects, the 'blank' is then an exact duplicate of the real phone and any calls made on the 'clone' will be charged to the original account. This problem was widespread with the first generation analogue technology, however the modern digital standards such as GSM greatly improve security and make cloning hard to achieve.

In an effort to limit the potential harm from having a transmitter close to the user's body, the first fixed/mobile cellular phones that had a separate transmitter, vehicle-mounted antenna, and handset (known as car phones and bag phones) were limited to a maximum 3 watts Effective Radiated Power. Modern handheld cellphones which must have the transmission antenna held inches from the user's skull are limited to a maximum transmission power of 0.6 watts ERP. Regardless of the potential biological effects, the reduced transmission range of modern handheld phones limits their usefulness in rural locations as compared to car/bag phones, and handhelds require that cell towers are spaced much closer together to compensate for their lack of transmission power.

Usage

[edit]By civilians

[edit]

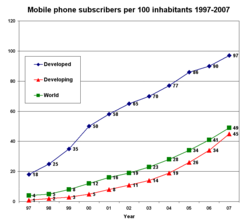

An increasing number of countries, particularly in Europe, now have more mobile phones than people. According to the figures from Eurostat, the European Union's in-house statistical office, Luxembourg had the highest mobile phone penetration rate at 158 mobile subscriptions per 100 people, closely followed by Lithuania and Italy.[20] In Hong Kong the penetration rate reached 139.8% of the population in July 2007.[21] Over 50 countries have mobile phone subscription penetration rates higher than that of the population and the Western European average penetration rate was 110% in 2007 (source Informa 2007).

There are over five hundred million active mobile phone accounts in China, as of 2007, but the total penetration rate there still stands below 50%.[22] The total number of mobile phone subscribers in the world was estimated at 2.14 billion in 2005.[23] The subscriber count reached 3.3 billion by November 2007,[18] thus reaching an equivalent of over half the planet's population. Around 80% of the world's population had access to mobile phone coverage as of 2006.

The rise of mobile phone technology in developing countries is often cited as an example of the leapfrog effect. Many remote regions in the third world went from having no telecommunications infrastructure to having satellite based communications systems. In 2005, Africa had the largest growth rate of cellular subscribers in the world,[24] its markets expanding nearly twice as fast as Asian markets.[25] The availability of prepaid or 'pay-as-you-go' services, where the subscriber is not committed to a long-term contract, has helped fuel this growth in Africa as well as in other continents.

In absolute numbers, India was the largest growth market in 2007, adding about 6 million mobile phones every month.[26] In 2015, it had a mobile subscriber base of 937.06 million mobile phones.[27]

Traffic

[edit]Since the world is operating quickly to 3G and 4G networks, mobile traffic through video is heading high. It was expected that by the end of 2018, the global traffic would reach an annual rate of 190 exabytes/year. This is the result of people shifting to smartphones.

Mobile traffic was predicted to reach by 10 billion connections by 2018, with 94% of traffic coming from smartphones, laptops and tablets. 69% of mobile traffic will be from videos, since we have high definition screens available in smart phones and 176.9 wearable devices to be at use. 4G was expected to dominate the traffic by 51% of total mobile data by 2018.[28]

By government agencies

[edit]Law enforcement

[edit]Law enforcement have used mobile phone evidence in a number of different ways. Evidence about the physical location of an individual at a given time can be obtained by triangulating the individual's cellphone between several cellphone towers. This triangulation technique can be used to show that an individual's cellphone was at a certain location at a certain time. The concerns over terrorism and terrorist use of technology prompted an inquiry by the British House of Commons Home Affairs Select Committee into the use of evidence from mobile phone devices, prompting leading mobile telephone forensic specialists to identify forensic techniques available in this area.[29] NIST have published guidelines and procedures for the preservation, acquisition, examination, analysis, and reporting of digital information present on mobile phones can be found under the NIST Publication SP800-101.[30]

In the UK in 2000 it was claimed that recordings of mobile phone conversations made on the day of the Omagh bombing were crucial to the police investigation. In particular, calls made on two mobile phones which were tracked from south of the Irish border to Omagh and back on the day of the bombing, were considered of vital importance.[31]

Further example of criminal investigations using mobile phones is the initial location and ultimate identification of the terrorists of the 2004 Madrid train bombings. In the attacks, mobile phones had been used to detonate the bombs. However, one of the bombs failed to detonate, and the SIM card in the corresponding mobile phone gave the first serious lead about the terrorists to investigators. By tracking the whereabouts of the SIM card and correlating other mobile phones that had been registered in those areas, police were able to locate the terrorists.[32]

Disaster response

[edit]The Finnish government decided in 2005 that the fastest way to warn citizens of disasters was the mobile phone network. In Japan, mobile phone companies provide immediate notification of earthquakes and other natural disasters to their customers free of charge.[33] In the event of an emergency, disaster response crews can locate trapped or injured people using the signals from their mobile phones. An interactive menu accessible through the phone's web browser notifies the company if the user is safe or in distress.[citation needed] In Finland rescue services suggest hikers carry mobile phones in case of emergency even when deep in the forests beyond cellular coverage, as the radio signal of a cellphone attempting to connect to a base station can be detected by overflying rescue aircraft with special detection gear. Also, users in the United States can sign up through their provider for free text messages when an Amber alert goes out for a missing person in their area.

However, most mobile phone networks operate close to capacity during normal times, and spikes in call volumes caused by widespread emergencies often overload the system just when it is needed the most. Examples reported in the media where this has occurred include the September 11, 2001 attacks, the 2003 Northeast blackouts, the 2005 London Tube bombings, Hurricane Katrina, the 2006 Kiholo Bay earthquake, and the 2007 Minnesota bridge collapse.

Under FCC regulations, all mobile telephones must be capable of dialing emergency telephone numbers, regardless of the presence of a SIM card or the payment status of the account.

Impact on society

[edit]Human health

[edit]Since the introduction of mobile phones, concerns (both scientific and public) have been raised about the potential health impacts from regular use.[34] However, by 2008, American mobile phones transmitted and received more text messages than phone calls.[35] Numerous studies have reported no significant relationship between mobile phone use and health, but the effect of mobile phone usage on health continues to be an area of public concern.[citation needed]

For example, at the request of some of their customers, Verizon created usage controls that meter service and can switch phones off, so that children could get some sleep.[35] There have also been attempts to limit use by persons operating moving trains or automobiles, coaches when writing to potential players on their teams, and movie theater audiences.[35] By one measure, nearly 40% of automobile drivers aged 16 to 30 years old text while driving, and by another, 40% of teenagers said they could text blindfolded.[35]

18 studies have been conducted on the link between cell phones and brain cancer. A review of these studies found that cell phone use of 10 years or more "give a consistent pattern of an increased risk for acoustic neuroma and glioma".[36] The tumors are found mostly on the side of the head that the mobile phone is in contact with. In July 2008, Dr. Ronald Herberman, director of the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, warned about the radiation from mobile phones. He stated that there was no definitive proof of the link between mobile phones and brain tumors but there was enough studies that mobile phone usage should be reduced as a precaution.[37] To reduce the amount of radiation being absorbed hands free devices can be used or texting could supplement calls. Calls could also be shortened or limit mobile phone usage in rural areas. Radiation is found to be higher in areas that are located away from mobile phone towers.[38]

According to Reuters, The British Association of Dermatologists is warning of a rash occurring on people's ears or cheeks caused by an allergic reaction from the nickel surface commonly found on mobile devices’ exteriors. There is also a theory it could even occur on the fingers if someone spends a lot of time text messaging on metal menu buttons. In 2008, Lionel Bercovitch of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and his colleagues tested 22 popular handsets from eight different manufacturers and found nickel on 10 of the devices.[39]

Human behaviour

[edit]Culture and customs

[edit]

Between the 1980s and the 2000s, the mobile phone has gone from being an expensive item used by the business elite to a pervasive, personal communications tool for the general population. In most countries, mobile phones outnumber land-line phones, with fixed landlines numbering 1.3 billion but mobile subscriptions 3.3 billion at the end of 2007.

In many markets from Japan and South Korea, to Europe, to Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong, most children age 8-9 have mobile phones and the new accounts are now opened for customers aged 6 and 7. Where mostly parents tend to give hand-me-down used phones to their youngest children, in Japan already new cameraphones are on the market whose target age group is under 10 years of age, introduced by KDDI in February 2007. The USA also lags on this measure, as in the US so far, about half of all children have mobile phones.[40] In many young adults' households it has supplanted the land-line phone. Mobile phone usage is banned in some countries, such as North Korea and restricted in some other countries such as Burma.[41]

Given the high levels of societal mobile phone service penetration, it is a key means for people to communicate with each other. The SMS feature spawned the "texting" sub-culture amongst younger users. In December 1993, the first person-to-person SMS text message was transmitted in Finland. Currently, texting is the most widely used data service; 1.8 billion users generated $80 billion of revenue in 2006 (source ITU). Many phones offer Instant Messenger services for simple, easy texting. Mobile phones have Internet service (e.g. NTT DoCoMo's i-mode), offering text messaging via e-mail in Japan, South Korea, China, and India. Most mobile internet access is much different from computer access, featuring alerts, weather data, e-mail, search engines, instant messages, and game and music downloading; most mobile internet access is hurried and short.

Because mobile phones are often used publicly, social norms have been shown to play a major role in the usage of mobile phones.[42] Furthermore, the mobile phone can be a fashion totem custom-decorated to reflect the owner's personality[43] and may be a part of their self-identity.[42] This aspect of the mobile telephony business is, in itself, an industry, e.g. ringtone sales amounted to $3.5 billion in 2005.[44] Mobile phone use on aircraft is starting to be allowed with several airlines already offering the ability to use phones during flights. Mobile phone use during flights used to be prohibited and many airlines still claim in their in-plane announcements that this prohibition is due to possible interference with aircraft radio communications. Shut-off mobile phones do not interfere with aircraft avionics. The recommendation why phones should not be used during take-off and landing, even on planes that allow calls or messaging, is so that passengers pay attention to the crew for any possible accident situations, as most aircraft accidents happen on take-off and landing.

Etiquette

[edit]Mobile phone use can be an important matter of social discourtesy: phones ringing during funerals or weddings; in toilets, cinemas and theatres. Some book shops, libraries, bathrooms, cinemas, doctors' offices and places of worship prohibit their use, so that other patrons will not be disturbed by conversations. Some facilities install signal-jamming equipment to prevent their use, although in many countries, including the US, such equipment is illegal.

Many US cities with subway transit systems underground are studying or have implemented mobile phone reception in their tunnels for their riders, and trains, particularly those involving long-distance services, often offer a "quiet carriage" where phone use is prohibited, much like the designated non-smoking carriage of the past. Most schools in the United States and Europe and Canada have prohibited mobile phones in the classroom, or in school in an effort to limit class disruptions.

A working group made up of Finnish telephone companies, public transport operators and communications authorities has launched a campaign to remind mobile phone users of courtesy, especially when using mass transit—what to talk about on the phone, and how to. In particular, the campaign wants to impact loud mobile phone usage as well as calls regarding sensitive matters.[45]

Use by drivers

[edit]The use of mobile phones by people who are driving has become increasingly common, for example as part of their job, as in the case of delivery drivers who are calling a client, or socially as for commuters who are chatting with a friend. While many drivers have embraced the convenience of using their cellphone while driving, some jurisdictions have made the practice against the law, such as Australia, the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador as well as the United Kingdom, consisting of a zero-tolerance system operated in Scotland and a warning system operated in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Officials from these jurisdictions argue that using a mobile phone while driving is an impediment to vehicle operation that can increase the risk of road traffic accidents.

Studies have found vastly different relative risks (RR). Two separate studies using case-crossover analysis each calculated RR at 4,[46][47] while an epidemiological cohort study found RR, when adjusted for crash-risk exposure, of 1.11 for men and 1.21 for women.[48]

A simulation study from the University of Utah Professor David Strayer compared drivers with a blood alcohol content of 0.08% to those conversing on a cell phone, and after controlling for driving difficulty and time on task, the study concluded that cell phone drivers exhibited greater impairment than intoxicated drivers.[49] Meta-analysis by The Canadian Automobile Association[50] and The University of Illinois[51] found that response time while using both hands-free and hand-held phones was approximately 0.5 standard deviations higher than normal driving (i.e., an average driver, while talking on a cell phone, has response times of a driver in roughly the 40th percentile).

Driving while using a hands-free device is not safer than driving while using a hand-held phone, as concluded by case-crossover studies.[47][46] epidemiological studies,[48] simulation studies,[49] and meta-analysis.[50][51] Even with this information, California initiated new Wireless Communications Device Law (effective January 1, 2009) makes it an infraction to write, send, or read text-based communication on an electronic wireless communications device, such as a cell phone, while driving a motor vehicle. Two additional laws dealing with the use of wireless telephones while driving went into effect July 1, 2008. The first law prohibits all drivers from using a handheld wireless telephone while operating a motor vehicle. The law allows a driver to use a wireless telephone to make emergency calls to a law enforcement agency, a medical provider, the fire department, or other emergency services agency. The base fine for the FIRST offense is $20 and $50 for subsequent convictions. With penalty assessments, the fine can be more than triple the base fine amount.[52][53] According to California Vehicle Code [VC] §23123, Motorists 18 and over may use a “hands-free device". The second law effective July 1, 2008, prohibits drivers under the age of 18 from using a wireless telephone or hands-free device while operating a motor vehicle (VC §23124). The consistency of increased crash risk between hands-free and hand-held phone use is at odds with legislation in over 30 countries that prohibit hand-held phone use but allow hands-free. Scientific literature is mixed on the dangers of talking on a phone versus those of talking with a passenger, with the Accident Research Unit at the University of Nottingham finding that the number of utterances was usually higher for mobile calls when compared to blindfolded and non-blindfolded passengers,[54] but the University of Illinois meta-analysis concluding that passenger conversations were just as costly to driving performance as cell phone ones.[51]

Use on aircraft

[edit]As of 2007, several airlines are experimenting with base station and antenna systems installed on the airplane, allowing low power, short-range connection of any phones aboard to remain connected to the aircraft's base station.[55] Thus, they would not attempt connection to the ground base stations as during takeoff and landing.[citation needed] Simultaneously, airlines may offer phone services to their travelling passengers either as full voice and data services, or initially only as SMS text messaging and similar services. The Australian airline Qantas is the first airline to run a test aeroplane in this configuration in the autumn of 2007.[citation needed] Emirates has announced plans to allow limited mobile phone usage on some flights.[citation needed] However, in the past, commercial airlines have prevented the use of cell phones and laptops, due to the assertion that the frequencies emitted from these devices may disturb the radio waves contact of the airplane.

On March 20, 2008, an Emirates flight was the first time voice calls have been allowed in-flight on commercial airline flights. The breakthrough came after the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and the United Arab Emirates-based General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) granted full approval for the AeroMobile system to be used on Emirates. Passengers were able to make and receive voice calls as well as use text messaging. The system automatically came into operation as the Airbus A340-300 reached cruise altitude. Passengers wanting to use the service received a text message welcoming them to the AeroMobile system when they first switched their phones on. The approval by EASA has established that GSM phones are safe to use on airplanes, as the AeroMobile system does not require the modification of aircraft components deemed "sensitive," nor does it require the use of modified phones.

In any case, there are inconsistencies between practices allowed by different airlines and even on the same airline in different countries. For example, Delta Air Lines may allow the use of mobile phones immediately after landing on a domestic flight within the US, whereas they may state "not until the doors are open" on an international flight arriving in the Netherlands. In April 2007 the US Federal Communications Commission officially prohibited passengers' use of cell phones during a flight.[56]

In a similar vein, signs are put up in many countries, such as Canada, the UK and the U.S., at petrol stations prohibiting the use of mobile phones, due to possible safety issues.[citation needed] However, it is unlikely that mobile phone use can cause any problems,[57] and in fact "petrol station employees have themselves spread the rumour about alleged incidents."

Environmental impacts

[edit]

Like all high structures, cellular antenna masts pose a hazard to low flying aircraft. Towers over a certain height or towers that are close to airports or heliports are normally required to have warning lights. There have been reports that warning lights on cellular masts, TV-towers and other high structures can attract and confuse birds. US authorities estimate that millions of birds are killed near communication towers in the country each year.[58]

Some cellular antenna towers have been camouflaged to make them less obvious on the horizon, and make them look more like a tree.

An example of the way mobile phones and mobile networks have sometimes been perceived as a threat is the widely reported and later discredited claim that mobile phone masts are associated with the Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) which has reduced bee hive numbers by up to 75% in many areas, especially near cities in the US. The Independent newspaper cited a scientific study claiming it provided evidence for the theory that mobile phone masts are a major cause in the collapse of bee populations, with controlled experiments demonstrating a rapid and catastrophic effect on individual hives near masts.[59] Mobile phones were in fact not covered in the study, and the original researchers have since emphatically disavowed any connection between their research, mobile phones, and CCD, specifically indicating that the Independent article had misinterpreted their results and created "a horror story".[60][61] While the initial claim of damage to bees was widely reported, the corrections to the story were almost non-existent in the media.

There are more than 500 million used mobile phones in the US sitting on shelves or in landfills,[62] and it is estimated that over 125 million will be discarded this year alone.[citation needed] The problem is growing at a rate of more than two million phones per week, putting tons of toxic waste into landfills daily. Several companies offer to buy back and recycle mobile phones from users. In the United States many unwanted but working mobile phones are donated to women's shelters to allow emergency communication.

Tariff models

[edit]

Payment methods

[edit]There are two principal ways to pay for mobile telephony: the 'pay-as-you-go' model where conversation time is purchased and added to a phone unit via an Internet account or in shops or ATMs, or the contract model where bills are paid by regular intervals after the service has been consumed. It is increasingly common for a consumer to purchase a basic package and then bolt-on services and functionality to create a subscription customised to the users needs.

Pay as you go (also known as "pre-pay" or "prepaid") accounts were invented simultaneously in Portugal and Italy and today form more than half of all mobile phone subscriptions.[citation needed] USA, Canada, Costa Rica, Japan, Israel and Finland are among the rare countries left where most phones are still contract-based.[citation needed]

Incoming call charges

[edit]In the early days of mobile telephony, the operators (carriers) charged for all air time consumed by the mobile phone user, which included both outbound and inbound telephone calls. As mobile phone adoption rates increased, competition between operators meant that some decided not to charge for incoming calls in some markets (also called "calling party pays").

The European market adopted a calling party pays model throughout the GSM environment and soon various other GSM markets also started to emulate this model.

In Hong Kong, Singapore, Canada, and the United States, it is common for the party receiving the call to be charged per minute, although a few carriers are beginning to offer unlimited received phone calls. This is called the "Receiving Party Pays" model. In China, it was reported that both of its two operators were to adopt the caller-pays approach as early as January 2007.[63]

One disadvantage of the receiving party pays systems is that phone owners keep their phones turned off to avoid receiving unwanted calls, which results in the total voice usage rates (and profits) in Calling Party Pays countries outperforming those in Receiving Party Pays countries.[64] To avoid the problem of users keeping their phone turned off, most Receiving Party Pays countries have either switched to Calling Party Pays, or their carriers offer additional incentives such as a large number of monthly minutes at a sufficiently discounted rate to compensate for the inconvenience.

When a user roams in another country, international roaming tariffs apply to all calls received, regardless of the model adopted in the home country.[65]

Technologies used

[edit]| Generation | Year | Max. speed | Frequency | Max. range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major | Minor | Standards | Band | Channel spacing | |||

| 0G | 0G (Pre-cellular) | MTS, IMTS, AMTS | 1940s–1970s | ~14.4 kbps | VHF/UHF (30–900 MHz) | ~20–50 kHz | ~30 km |

| 1G | 1G | AMPS, NMT, TACS | 1980s | ~2.4 kbps | 800–900 MHz | 30 kHz | ~10–30 km |

| 1.5G (Digital signaling) | AMPS with digital control channels | Late 1980s | ~9.6 kbps | 800–900 MHz | 30 kHz | ~10–30 km | |

| 2G | 2G | GSM, IS-95 (CDMAOne), D-AMPS | Early 1990s | ~9.6–14.4 kbps | 850 MHz, 900 MHz, 1800 MHz, 1900 MHz | 200 kHz (GSM), 1.25 MHz (CDMAOne) | ~35 km (GSM) |

| 2.5G | GPRS, EDGE | Late 1990s | ~40–144 kbps | Same as 2G | 200 kHz (GSM) | ~35 km | |

| 2.75G | EDGE (E-GPRS) | Early 2000s | ~473 kbps | Same as 2G | 200 kHz (GSM) | ~35 km | |

| 2.9G | EV-DO Rev. 0 (CDMA2000) | Mid-2000s | ~2.4 Mbps | 850/1900 MHz | 1.25 MHz | ~35 km | |

| 3G | 3G | UMTS, CDMA2000, WCDMA | Early 2000s | ~2 Mbps | 850/900/1900/2100 MHz | 5 MHz | ~2–5 km (urban), ~30 km (rural) |

| 3.5G | HSPA, EV-DO Rev. A | Mid-2000s | ~14.4 Mbps | Same as 3G | 5 MHz | ~2–5 km | |

| 3.75G | HSPA+, EV-DO Rev. B | Late 2000s | ~42 Mbps | Same as 3G | 5 MHz | ~2–5 km | |

| 3.9G/3.95G | LTE (Pre-4G) | Early 2010s | ~100 Mbps (DL) / 50 Mbps (UL) | 600 MHz – 2.5 GHz | 1.4–20 MHz | ~5–10 km | |

| 4G | 4G | LTE-A (4G) | 2010s | ~1 Gbps | 600 MHz – 5 GHz | 1.4–20 MHz | ~5–10 km |

| 4.5G | LTE-A Pro | Mid-2010s | ~3 Gbps | Same as 4G | 1.4–100 MHz | ~5–10 km | |

| 4.9G | LTE-A Pro (High-band) | Late 2010s | ~10 Gbps | Same as 4G, includes mmWave (24 GHz–40 GHz) | 1.4–100 MHz | ~1 km (mmWave) | |

| 5G | 5G | 5G NR (Release 15) | 2020s | ~20 Gbps (DL) / ~10 Gbps (UL) | Sub-6 GHz (600 MHz – 7 GHz), mmWave (24 GHz – 100 GHz) | 10–400 MHz | ~1 km (mmWave), ~10 km (Sub-6 GHz) |

| 5.25G | 5G-Advanced (Release 18) | 2023+ | ~50 Gbps | Same as 5G | 10–400 MHz | ~1 km (mmWave), ~10 km (Sub-6 GHz) | |

| 5.5G | 5G-Advanced (Release 19) | 2025+ | ~100 Gbps | Same as 5G | 10–400 MHz | ~1 km (mmWave), ~10 km (Sub-6 GHz) | |

| 6G | 6G | IMT-2030 (Expected) | 2030s | ~1 Tbps | Terahertz (THz) bands (100 GHz – 1 THz) | Wideband (GHz-level channels) | ~100–200 m (THz), ~5 km (Sub-THz) |

The list below is a non-comprehensive attempt at listing the technologies used in mobile telephony:

0G (mobile radio telephone)

1G networks (analog networks)

2G networks (the first digital networks):

- Digital AMPS

- cdmaOne

- GSM

- GPRS

- EDGE(IMT-SC)

- Evolved EDGE

3G networks:

4G networks:

- LTE (TD-LTE)

- LTE Advanced

- LTE Advanced Pro

- WiMAX

- WiMAX-Advanced (WirelessMAN-Advanced)

- Ultra Mobile Broadband (never commercialized)

5G networks:

Starting with EVDO the following techniques can also be used to improve performance:

- MIMO, SDMA and Beamforming

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wu, Tim (June 10, 2008). "iSurrender: Apple's new iPhone augurs the inevitable return of the Bell telephone monopoly". Slate.

- ^ "Asset Bank | Image Details". Imagelibrary.btplc.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "Asset Bank | Image Details". Imagelibrary.btplc.com. Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Patent No. 3,663,762, issued May 16, 1972.

- ^ List of National Inventors Hall of Fame inductees

- ^ a b Srivastava, Viranjay M.; Singh, Ghanshyam (2013). MOSFET Technologies for Double-Pole Four-Throw Radio-Frequency Switch. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1. ISBN 9783319011653.

- ^ "30th Anniversary of First Wireless Cell Phone Call". 3g.co.uk. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Article by Larry Kahaner and Alan Green in the Chicago Tribune of December 22, 1983 Reach out and touch someone--by land, sea or air

- ^ Phil Ament. "Mobile Phone History - Invention of the Mobile Phone". Ideafinder.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Visited and evaluated by a group of (soon-to-be) British Telecoms staff (including writer) in September 1982.

- ^ "Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology". Tekniskamuseet.se. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2009.

- ^ "Mobile and technology: The Basics of Mobile Phones". Sharelie-download.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "Facts about the Mobile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2010. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ^ US5257397A, Barzegar, Farhad; Eryaman, Can A. & Russell, Jesse E. et al., "Mobile data telephone", issued 1993-10-26 (filed 1990-08-13)

- ^ Hassanien, Aboul Ella; Shaalan, Khaled; Gaber, Tarek; Azar, Ahmad Taher; Tolba, M. F. (October 20, 2016). Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics 2016. Springer. pp. xiv. ISBN 978-3-319-48308-5.

- ^ Ergen, Mustafa (2009). Mobile Broadband: including WiMAX and LTE. Springer Science+Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68192-4. ISBN 978-0-387-68189-4.

- ^ "Full Members ~ GSM World". Gsmworld.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ a b "Global cellphone penetration reaches 50 pct". Reuters. November 29, 2007. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023.

- ^ "Duke of Cambridge Presents Maxwell Medals to GSM Developers". IEEE United Kingdom and Ireland Section. September 1, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "Europeans hang up on fixed lines". BBC News. November 28, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Office of the Telecommunications Authority in Hong Kong Archived March 9, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "500 mln cell phone accounts in China". ITFacts Mobile usage. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- ^ "Total mobile subscribers top 1.8 billion - MobileTracker". www.mobiletracker.net.

- ^ "Mobile growth fastest in Africa". BBC News. March 9, 2005.

- ^ Rice, Xan (March 4, 2006). "Phone revolution makes Africa upwardly mobile". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ "The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved February 8, 2009. (444 KB)

- ^ "The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Mobile Network 2018". www.Phoneam.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ^ The Committee Office, House of Commons. "Supplementary memorandum submitted by Gregory Smith". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Jansen, W.; Ayers, R. P. (2007). Guidelines on cell phone forensics (PDF). doi:10.6028/NIST.SP.800-101.

- ^ "Mobile phones key to Omagh probe". BBC News. October 10, 2000. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "Communication safety". Nokia-n98.org. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "New Japanese phones offer Earthquake early warning alerts". Archived from the original on January 21, 2008. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

- ^ Campbell, Jonathan. "Cellular Phones and Cancer". Archived from the original on January 20, 1998. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Steinhauser, Jennifer & Holson, Laura M. (September 19, 2008). "Text Messages Seen as Dangerously Distracting". The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ^ Hamilton, Tyler. "Listening to Cell Phone Warnings: Researchers Working Overtime to Find Out If the Greatest Tool of Business is Causing Brain Cancer in Those Who Use it Constantly" Toronto Star. May 31, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- ^ "The BBC. "US Cancer Boss in Mobiles Warning." BBC News 24 July 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008". BBC News. July 24, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Rachel Lieberman, Brandel France de Bravo, MPH, and Diana Zuckerman, Ph.D. "Can Cell Phones Harm Our Health? Archived February 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine" National Research Center for Women and Families. August 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2013. /

- ^ Doctors warn of rash from mobile phone use Reuters.com. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ^ "Mobile Phones for Kids Under 15: a Responsible Question". Point.com. April 13, 2006. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ "Rise in executions for mobile use". ITV News. June 15, 2007. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved June 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Burger, Christoph; Riemer, Valentin; Grafeneder, Jürgen; Woisetschläger, Bianca; Vidovic, Dragana; Hergovich, Andreas (2010). "Reaching the Mobile Respondent: Determinants of High-Level Mobile Phone Use Among a High-Coverage Group" (PDF). Social Science Computer Review. 28 (3): 336–349. doi:10.1177/0894439309353099. S2CID 61640965.

- ^ Aquino, Grace (April 28, 2006). "Cell Phone Fashion Show". PC World. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Gundersen, Edna, "Mastertones ring up profits", USA Today, 11/29/2006

- ^ campaign to promote cell phone manners (in finish)

- ^ a b Redelmeier, Donald; Tibshirani, Robert (February 13, 1997). "Association Between Cellular-Telephone Calls And Motor Vehicle Collisions" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (7): 453–458. doi:10.1056/NEJM199702133360701. PMID 9017937. S2CID 23723296. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 18, 2009.

- ^ a b McEvoy, Suzanne; Stevenson, MR; McCartt, AT; Woodward, M; Haworth, C; Palamara, P; Cercarelli, R (2005). "Role of mobile phones in motor vehicle crashes resulting in hospital attendance: a case-crossover study". BMJ. 331 (7514): 428. doi:10.1136/bmj.38537.397512.55. PMC 1188107. PMID 16012176.

- ^ a b Laberge-Nadeau, Claire (September 2003). "Wireless telephones and the risk of road crashes". Accident Analysis & Prevention. 35 (5): 649–660. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(02)00043-X. PMID 12850065.

- ^ a b Strayer, David; Drews, Frank; Crouch, Dennis (2003). "Fatal Distraction? A Comparison Of The Cell-Phone Driver And The Drunk Driver" (PDF). University of Utah Department of Psychology. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Jeffrey K. Caird; et al. (October 25, 2004). "Effects of Cellular Telephones on Driving Behaviour and Crash Risk: Results of Meta-Analysis" (PDF). Ama.ab.ca. CAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Horrey, William; Christopher Wickens (Spring 2006). "Examining the Impact of Cell Phone Conversations on Driving Using Meta-Analytic Techniques" (PDF). Human Factors. 38 (1). Human Factors and Ergonomics Society: 196–205. doi:10.1518/001872006776412135. PMID 16696268. S2CID 3918855. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2009. Retrieved June 27, 2009.

- ^ Domain, Public. "Text Messaging Law Effective January 1, 2009 Cellular Phone Laws Effective July 1, 2008". California Department of Motor Vehicles. California, USA: State of California. Archived from the original on August 7, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

- ^ "Untitled Document". November 21, 2013. Archived from the original on November 21, 2013.

- ^ David Crundall; Manpreet Bains; Peter Chapman; Geoffrey Underwood (2005). "Regulating conversation during driving: a problem for mobile telephones?" (PDF). Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 8F (3): 197–211. Bibcode:2005TRPF....8..197C. doi:10.1016/j.trf.2005.01.003. S2CID 143502056. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2007.

- ^ "Europe closer to allowing in-flight cellphone use". Engadget. October 18, 2007. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Clark, Amy (April 3, 2007). "FCC Says No To Cell Phones On Planes". CBS News. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ [1] Mobile Phones and Service Stations: Rumour, Risk and Precaution, by Adam Burgess (2007) Diogenes 213 54: 1

- ^ "Communication Towers and the Fish and Wildlife Service". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on August 5, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ Lean, Geoffrey; Shawcross, Harriet (April 15, 2007). "Are mobile phones wiping out our bees?". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ^ Eric Sylvers (April 22, 2007). "Wireless: Case of the disappearing bees creates a buzz about cellphones". International Herald Tribune.

- ^ Chloe Johnson (April 22, 2007). "Researchers: Often-cited study doesn't relate to bee colony collapse". Foster's Online.

- ^ "Study: Cell Phone Waste Harmful". Wired. Associated Press. May 7, 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Amy Gu, "Mainland mobile services to be cheaper", South China Morning Post, December 18, 2006, Page A1.

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). www.oecd.org.

- ^ "REGULATORY AND MARKET ENVIRONMENT" (PDF).

Further reading

[edit]- Chen, Adrian, "The Confidence Game: How Silicon Valley broke the economy", The Nation, vol. 309, no. 11 (4 November 2019), pp. 27–30. The multifarious abuses perpetrated by individuals, organizations, corporations, and governments, using the Internet and mobile telephony, prompt Adrian Chen to muse whether "a technical complex born... of Cold War militarism and mainstreamed in a free-market frenzy might not be fundamentally always at odds with human flourishing." (p. 30.)

Mobile telephony

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Pre-Cellular Mobile Radio Systems

Pre-cellular mobile radio systems relied on wide-area coverage from single base stations, operating without frequency reuse and constrained by limited spectrum allocation and manual operator intervention. These systems, primarily using amplitude modulation (AM) initially and later frequency modulation (FM) after World War II, faced inherent limitations such as single-channel per user at a time, line-of-sight propagation requirements for higher frequencies, and severe capacity bottlenecks due to the inability to serve multiple simultaneous users beyond the available channels. Engineering challenges included interference from shared spectrum and the need for high-power transmitters to achieve usable range, often 20-50 miles in urban areas, but demand quickly outstripped supply, with wait times for connection extending to hours in major cities.[14] Pioneering applications emerged in public safety and maritime communications. In 1928, the Detroit Police Department implemented the first one-way police radio system, allowing dispatchers to broadcast to patrol cars equipped with receivers built by officers Kenneth Cox and Robert Batts, marking a shift from call boxes to real-time mobile alerts amid rising urban crime during Prohibition. Ship-to-shore radiotelephony, operational by 1930, enabled voice calls between ocean liners like the SS Leviathan and coastal stations using shortwave frequencies with crystal-controlled transmitters—one for each direction—to connect passengers to landlines, though limited to a few ships and prone to atmospheric interference.[15] Commercial land mobile telephone services expanded post-1946, exemplified by Bell System's Mobile Telephone Service (MTS) launched in St. Louis on June 17, 1946, with equipment weighing about 80 pounds installed in vehicles and supporting only five channels via a single base station, requiring operator assistance for all calls.[14] Similar systems in other cities, such as New York with around 12 channels by the early 1950s, served fewer than 10,000 subscribers nationwide despite millions of potential users, as each channel could handle just one conversation at a time, underscoring the scalability issues that manual switching and spectrum scarcity imposed.[16] These constraints prompted theoretical advancements in spectrum efficiency. In 1947, Bell Labs engineer Douglas H. Ring proposed dividing service areas into smaller hexagonal cells, each with its own low-power transmitter reusing frequencies from non-adjacent cells, based on principles of signal propagation and interference avoidance to multiply capacity without additional spectrum—a concept derived from first-principles analysis of radio wave coverage patterns rather than immediate implementation.[17] This idea addressed the causal bottleneck of single-site architectures but remained conceptual until technological and regulatory developments enabled cellular deployment in the 1970s.Emergence of Cellular Technology (1970s-1980s)

The concept of cellular telephony, involving the division of geographic areas into small cells with reusable frequencies to overcome spectrum limitations in analog mobile radio, was advanced through private-sector experimentation in the 1970s, building on earlier theoretical work by enabling practical handoff and capacity gains via empirical field testing. Engineers at Motorola, motivated by competition with AT&T, focused on developing portable devices and network architectures that could support multiple simultaneous users far beyond the single-transmitter constraints of prior systems like Improved Mobile Telephone Service (IMTS). This innovation prioritized real-world deployment over regulatory mandates, with prototypes rigorously tested for reliability in urban environments. A pivotal demonstration occurred on April 3, 1973, when Motorola engineer Martin Cooper placed the first public handheld mobile phone call using a DynaTAC prototype on a New York City street, dialing a rival at Bell Labs to showcase portability.[18][19] The device weighed roughly 2 kilograms, featured a 30-minute talk time on its battery, and represented a leap from vehicle-mounted units by integrating transceiver miniaturization with cellular principles.[20] This event underscored Motorola's private initiative in proving handheld viability, contrasting with AT&T's focus on larger systems. The first commercial cellular service launched on October 13, 1983, with the Advanced Mobile Phone Service (AMPS) in Chicago by Ameritech, marking the operational debut of a 1G analog system using frequency division multiple access (FDMA).[21] AMPS allocated 666 duplex channels across the 800 MHz band (824-849 MHz uplink, 869-894 MHz downlink) with 30 kHz spacing and frequency reuse in a seven-cell cluster pattern, facilitating seamless handoffs and yielding approximately a 100-fold capacity increase over non-cellular mobile radio by allowing spectrum recycling across sites.[22][23] Competitive deployments followed internationally without centralized edicts, as in the Nordic Mobile Telephone (NMT) system's rollout across Scandinavia starting October 1, 1981, which adapted similar analog FDMA techniques for regional roaming.[24] In the United Kingdom, the Total Access Communication System (TACS), an AMPS derivative, commenced service on January 1, 1985, via Vodafone and Cellnet, spurring infrastructure buildout through duopoly rivalry.[25] These market-led efforts drove subscriber numbers from thousands in early deployments to over 4 million globally by late 1988, validating cellular's scalability through operator investments in base stations and empirical optimization of signal propagation.[26]Transition to Digital and Global Standards (1990s)

The first commercial deployment of a 2G digital cellular network occurred on July 1, 1991, when Finland's Radiolinja operator launched GSM services, marking the initial shift from analog to digital mobile telephony.[27] GSM utilized time-division multiple access (TDMA) to multiplex signals, dividing channels into time slots for multiple users, while incorporating subscriber identity module (SIM) cards to store authentication keys and enable encryption, thereby curbing fraud through mutual verification between device and network.[28] These mechanisms, absent in 1G analog systems, facilitated secure international roaming via standardized protocols and improved voice quality through digital compression and error correction, reducing noise and dropouts empirically observed in field trials.[29] An competing standard, IS-95 based on code-division multiple access (CDMA), emerged in the United States with its standardization by the Telecommunications Industry Association in 1995, enabling initial commercial rollouts by carriers like Sprint and Verizon predecessors.[30] CDMA employed spread-spectrum modulation, assigning unique codes to users for simultaneous transmission across the same bandwidth, yielding superior spectral efficiency—typically 2-3 times higher user capacity than TDMA under comparable conditions—due to power control and interference rejection.[31] The GSM-CDMA rivalry, unfolding without centralized government mandates, spurred vendor investments in optimization, such as adaptive antennas and handover algorithms, accelerating deployment efficiencies and feature enhancements across both camps.[32] Short Message Service (SMS), standardized within GSM, debuted with its inaugural transmission on December 3, 1992, over the Vodafone network in the United Kingdom, allowing 160-character text exchanges via out-of-band signaling.[33] By the late 1990s, enhancements like General Packet Radio Service (GPRS), specified in GSM Release 97 and commercially launched around 1999, introduced always-on packet data at speeds up to 114 kbps, bridging to rudimentary internet access without circuit-switched overhead.[34] GPRS's successor, Enhanced Data rates for GSM Evolution (EDGE), further boosted rates to 384 kbps via phase-shifted modulation, extending 2G viability for data while GSM captured over 80% global market share by 2000 through scale-driven cost reductions and operator licensing.[35]Broadband Era: 3G and 4G (2000s-2010s)

The third-generation (3G) mobile networks marked a shift toward packet-switched data services, enabling higher-speed internet access beyond voice and SMS dominance of prior eras. NTT DoCoMo launched the world's first commercial 3G service using Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (W-CDMA), a core component of Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS), on October 1, 2001, in Tokyo, Japan.[36][37] Initial deployments supported downlink data rates of up to 384 kbps in outdoor environments, facilitating basic web browsing, email, and multimedia messaging, though actual performance varied with signal conditions and device capabilities.[38][39] Subsequent enhancements like High-Speed Packet Access (HSPA) improved 3G performance, with High-Speed Downlink Packet Access (HSDPA) achieving peak speeds of up to 14 Mbps by the mid-2000s, supporting applications such as video calling and early streaming. Devices like the Nokia N95, released in 2007, exemplified this era's capabilities with HSDPA support for faster downloads and integrated video telephony features. These upgrades addressed growing consumer demand for mobile broadband, prompting widespread infrastructure investments in spectrum auctions and base station upgrades globally. The transition to fourth-generation (4G) networks accelerated packet-switched dominance with Long-Term Evolution (LTE), emphasizing all-IP architecture for seamless data handling without circuit-switched fallbacks. TeliaSonera initiated the first commercial LTE deployments on December 14, 2009, in Oslo, Norway, and Stockholm, Sweden, offering initial peak downlink speeds exceeding 100 Mbps via Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiple Access (OFDMA) modulation.[40][41] This all-IP core enabled efficient resource allocation and lower latency, contrasting with 3G's hybrid approach, and facilitated scalable broadband services like high-definition video and cloud access.[42][43] Market forces, including the 2007 iPhone launch and the 2008 debut of the Android platform with its app ecosystem, drove explosive demand for data-intensive applications, shifting networks from voice-centric (over 90% of traffic in early 2000s) to data-dominant usage.[44][45][46] By the mid-2010s, mobile data traffic had grown exponentially, comprising the majority of total mobile network load and surpassing voice in many regions, fueled by app economies and smartphone penetration exceeding 50% globally.[47] 4G subscriptions expanded rapidly, reaching over 1 billion connections by 2016 and overtaking 3G accumulations in key markets by the late 2010s, underscoring infrastructure shifts toward higher-capacity spectrum and denser cell sites.[48][49]5G Deployment and Recent Advances (2020s)

The initial commercial deployments of 5G New Radio (NR) began in 2019, with Verizon launching the first mobile 5G service in the United States in April of that year, initially leveraging millimeter-wave spectrum for high-speed fixed wireless access before expanding to sub-6 GHz bands for broader coverage.[50][51] These early rollouts achieved peak download speeds exceeding 1 Gbps in optimal conditions, enabling empirical demonstrations of enhanced throughput for data-intensive applications, though real-world performance varied due to propagation limits of higher frequencies.[52] By late 2025, global 5G connections had surpassed 2.7 billion, representing about 30% population coverage and driven by private sector investments in spectrum auctions and infrastructure, which proceeded despite regulatory delays in some regions related to health and security concerns.[53] Key technological advances in the 2020s have focused on massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) antennas and beamforming to boost spectral efficiency and support dense IoT deployments, yielding measurable reductions in latency to under 10 ms for ultra-reliable low-latency communication (URLLC) in industrial settings.[54] Edge computing integrations have further enabled real-time processing for Industry 4.0 applications, such as predictive maintenance in manufacturing, where private 5G networks—deployed by firms like Tesla and John Deere—have demonstrated improved automation reliability over legacy Wi-Fi.[55] From 2023 onward, AI-driven algorithms have optimized network slicing and resource allocation, enhancing dynamic traffic management and reducing operational costs by up to 20% in trials, as reported by equipment vendors.[56][57] Emerging hybrid architectures include satellite backhaul using low-Earth orbit constellations like Starlink, which empirical tests show can sustain 100 Mbps aggregate rates for remote 5G base stations, addressing coverage gaps in underserved areas.[58] Open radio access network (RAN) initiatives have promoted vendor interoperability to counter supply chain concentrations, though adoption remains limited to select pilots due to integration complexities.[59] Concurrently, 6G research and development, initiated around 2023, emphasizes terahertz bands for potential terabit-per-second rates by 2030, with early prototypes validating higher bandwidths but highlighting propagation and hardware challenges.[60][61] These developments underscore 5G's evolution toward integrated, low-latency ecosystems, supported by operator-led investments exceeding regulatory timelines in most markets.[62]Technical Architecture

Cellular Network Design and Spectrum Management

Cellular networks divide geographic areas into contiguous cells, each served by a base station, to exploit radio signal attenuation over distance for frequency reuse, enabling scalable coverage and capacity beyond single-transmitter limits imposed by propagation physics. Lower frequencies propagate farther with less path loss, supporting wide-area macrocells, while higher frequencies attenuate more rapidly, suiting denser microcells or picocells for urban capacity. This hexagonal or irregular cell geometry, derived from empirical models like Okumura-Hata, optimizes signal-to-interference ratios by spacing co-channel cells sufficiently to maintain viable signal-to-noise levels.[63][64] Hierarchical deployments integrate macrocells for baseline coverage with overlaid microcells, picocells, and femtocells to address capacity hotspots, reducing handover latency and load via intelligent cell selection. Base stations—eNodeB in LTE or gNodeB in 5G—manage air-interface resources, coordinating with backhaul infrastructure like fiber optics for low-latency, high-throughput links or microwave for cost-effective rural extensions, feeding into a core network for session routing, authentication, and seamless handover during mobility.[65][66] Spectrum management allocates scarce radio bands, balancing coverage from sub-1 GHz (e.g., 700 MHz) against capacity in mid-band (e.g., 3.5 GHz), with refarming repurposing legacy allocations for efficient dynamic sharing via techniques like carrier aggregation. Regulatory auctions, such as the U.S. FCC's Auction 100 concluding in February 2021 for the 600 MHz band, use market pricing to assign spectrum, outperforming administrative methods by reflecting true scarcity and incentivizing investment.[67] Interference mitigation relies on reuse patterns grouping cells into clusters, typically size 7 in hexagonal layouts, ensuring co-channel cells are separated by a factor derived from propagation models to keep interference below thresholds for acceptable bit error rates. Empirical signal-to-noise analyses guide cluster sizing, trading reuse efficiency against interference risk, with modern beamforming further enhancing spatial isolation without enlarging clusters.[63][68]Generations of Standards: From 1G to 5G

The evolution of mobile telephony standards from 1G to 5G reflects progressive enhancements in spectral efficiency, network capacity, and support for data services, driven by shifts from analog to digital transmission and adoption of advanced multiple access techniques. Each generation has empirically increased user throughput and cell capacity through wider channel bandwidths, improved modulation, and interference mitigation, as evidenced by real-world deployments where 2G systems supported 3-5 times more subscribers per cell than 1G due to digital processing and frequency reuse patterns.[23][69] Later generations further amplified these gains via packet-switched architectures and massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) antennas, reducing latency from tens of milliseconds in early digital systems to sub-millisecond targets in 5G.[70] First-generation (1G) standards employed analog frequency division multiple access (FDMA) for voice-only service, with the Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) using 30 kHz channels in the 800 MHz band, enabling limited capacity of approximately 395 voice channels per carrier with frequency reuse clusters of 7 cells to manage co-channel interference requiring 18 dB carrier-to-interference ratios.[71][23] These systems, deployed starting in 1983, lacked data capabilities and encryption, resulting in poor efficiency and vulnerability to eavesdropping, with spectral utilization below 1 bit/s/Hz due to narrowband analog modulation.[22]| Generation | Primary Standards | Multiple Access | Typical Channel Bandwidth | Peak Data Rate (Initial) | Key Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1G | AMPS, NMT | FDMA | 30 kHz | Voice only (~64 kbps equiv.) | Analog voice, basic mobility |

| 2G | GSM, IS-95 | TDMA/CDMA | 200 kHz / 1.25 MHz | 9.6-14.4 kbps | Digital voice, SMS, encryption; 3x capacity |

| 3G | UMTS WCDMA, CDMA2000 | CDMA | 5 MHz | 384 kbps-2 Mbps | Packet data, higher efficiency via spread spectrum |

| 4G | LTE | OFDMA (DL), SC-FDMA (UL) | 20 MHz | ~150-300 Mbps DL | All-IP, MIMO; 10x throughput, ~10 ms latency |

| 5G | NR (Rel. 15+) | OFDMA | 100 MHz (sub-6), 400 MHz (mmWave) | 5-10 Gbps DL | Ultra-low latency (<1 ms), 100x capacity via beamforming |