Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Naval mine

View on Wikipedia

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are deposited and left to wait until, depending on their fuzing, they are triggered by the approach of or contact with any vessel.

Naval mines can be used offensively, to hamper enemy shipping movements or lock vessels into a harbour; or defensively, to create "safe" zones protecting friendly sea lanes, harbours, and naval assets. Mines allow the minelaying force commander to concentrate warships or defensive assets in mine-free areas giving the adversary three choices: undertake a resource-intensive and time-consuming minesweeping effort, accept the casualties of challenging the minefield, or use the unmined waters where the greatest concentration of enemy firepower will be encountered.[1]

Although international law requires signatory nations to declare mined areas, precise locations remain secret, and non-complying parties might not disclose minelaying. While mines threaten only those who choose to traverse waters that may be mined, the possibility of activating a mine is a powerful disincentive to shipping. In the absence of effective measures to limit each mine's lifespan, the hazard to shipping can remain long after the war in which the mines were laid is over. Unless detonated by a parallel time fuze at the end of their useful life, naval mines need to be found and dismantled after the end of hostilities; an often prolonged, costly, and hazardous task.

Modern mines containing high explosives detonated by complex electronic fuze mechanisms are much more effective than early gunpowder mines requiring physical ignition. Mines may be placed by aircraft, ships, submarines, or individual swimmers and boatmen. Minesweeping is the practice of the removal of explosive naval mines, usually by a specially designed ship called a minesweeper using various measures to either capture or detonate the mines, but sometimes also with an aircraft made for that purpose. There are also mines that release a homing torpedo rather than explode themselves.

Description

[edit]Mines can be laid in many ways: by purpose-built minelayers, refitted ships, submarines, or aircraft—and even by dropping them into a harbour by hand. They can be inexpensive: some variants can cost as little as US $2,000, though more sophisticated mines can cost millions of dollars, be equipped with several kinds of sensors, and deliver a warhead by rocket or torpedo.

Their flexibility and cost-effectiveness make mines attractive to the less powerful belligerent in asymmetric warfare. The cost of producing and laying a mine is usually between 0.5% and 10% of the cost of removing it, and it can take up to 200 times as long to clear a minefield as to lay it. Parts of some World War II naval minefields still exist because they are too extensive and expensive to clear.[2] Some 1940s-era mines may remain dangerous for many years.[3]

Mines have been employed as offensive or defensive weapons in rivers, lakes, estuaries, seas, and oceans, but they can also be used as tools of psychological warfare. Offensive mines are placed in enemy waters, outside harbours, and across important shipping routes to sink both merchant and military vessels. Defensive minefields safeguard key stretches of coast from enemy ships and submarines, forcing them into more easily defended areas, or keeping them away from sensitive ones.

Shipowners are reluctant to send their ships through known minefields. Port authorities may attempt to clear a mined area, but those without effective minesweeping equipment may cease using the area. Transit of a mined area will be attempted only when strategic interests outweigh potential losses. The decision-makers' perception of the minefield is a critical factor. Minefields designed for psychological effect are usually placed on trade routes to stop ships from reaching an enemy nation. They are often spread thinly, to create an impression of minefields existing across large areas. A single mine inserted strategically on a shipping route can stop maritime movements for days while the entire area is swept. A mine's capability to sink ships makes it a credible threat, but minefields work more on the mind than on ships.[4]

International law, specifically the Eighth Hague Convention of 1907, requires nations to declare when they mine an area, to make it easier for civil shipping to avoid the mines. The warnings do not have to be specific; for example, during World War II, Britain declared simply that it had mined the English Channel, North Sea and French coast.[citation needed]

History

[edit]Early use

[edit]

Naval mines were first invented by Chinese innovators of Imperial China and were described in thorough detail by the early Ming dynasty artillery officer Jiao Yu, in his 14th-century military treatise known as the Huolongjing.[5] Chinese records tell of naval explosives in the 16th century, used to fight against Japanese pirates (wokou). This kind of naval mine was loaded in a wooden box, sealed with putty. General Qi Jiguang made several timed, drifting explosives, to harass Japanese pirate ships.[6] The Tiangong Kaiwu (The Exploitation of the Works of Nature) treatise, written by Song Yingxing in 1637, describes naval mines with a ripcord pulled by hidden ambushers located on the nearby shore who rotated a steel wheel flint mechanism to produce sparks and ignite the fuze of the naval mine.[7] Although this is the rotating steel wheel's first use in naval mines, Jiao Yu described their use for land mines in the 14th century.[8]

The first plan for a sea mine in the West was by Ralph Rabbards, who presented his design to Queen Elizabeth I of England in 1574.[7] The Dutch inventor Cornelius Drebbel was employed in the Office of Ordnance by King Charles I of England to make weapons, including the failed "floating petard".[9] Weapons of this type were apparently tried by the English at the Siege of La Rochelle in 1627.[10]

American David Bushnell developed the first American naval mine, for use against the British in the American War of Independence.[11] It was a watertight keg filled with gunpowder that was floated toward the enemy, detonated by a sparking mechanism if it struck a ship. It was used on the Delaware River as a drift mine, destroying a small boat near its intended target, a British warship.[12]

The 19th century

[edit]

The 1804 Raid on Boulogne made extensive use of explosive devices designed by inventor Robert Fulton. The 'torpedo-catamaran' was a coffer-like device balanced on two wooden floats and steered by a man with a paddle. Weighted with lead so as to ride low in the water, the operator was further disguised by wearing dark clothes and a black cap.[13] His task was to approach the French ship, hook the torpedo to the anchor cable and, having activated the device by removing a pin, remove the paddles and escape before the torpedo detonated.[14] Also to be deployed were large numbers of casks filled with gunpowder, ballast and combustible balls. They would float in on the tide and on washing up against an enemy's hull, explode.[14] Also included in the force were several fireships, carrying 40 barrels of gunpowder and rigged to explode by a clockwork mechanism.[14]

In 1812, Russian engineer Pavel Shilling exploded an underwater mine using an electrical circuit. In 1842 Samuel Colt used an electric detonator to destroy a moving vessel to demonstrate an underwater mine of his own design to the United States Navy and President John Tyler. However, opposition from former president John Quincy Adams, scuttled the project as "not fair and honest warfare".[15] In 1854, during the unsuccessful attempt of the Anglo-French (101 warships) fleet to seize the Kronstadt fortress, British steamships HMS Merlin (9 June 1855, the first successful mining in Western history), HMS Vulture and HMS Firefly suffered damage due to the underwater explosions of Russian naval mines. Russian naval specialists set more than 1,500 naval mines, or infernal machines, designed by Moritz von Jacobi and by Immanuel Nobel,[16] in the Gulf of Finland during the Crimean War of 1853–1856. The mining of Vulcan led to the world's first minesweeping operation.[17][18] During the next 72 hours, 33 mines were swept.[19]

The Jacobi mine was designed by German-born, Russian engineer Jacobi, in 1853. The mine was tied to the sea bottom by an anchor. A cable connected it to a galvanic cell which powered it from the shore, the power of its explosive charge was equal to 14 kg (31 lb) of black powder. In the summer of 1853, the production of the mine was approved by the Committee for Mines of the Ministry of War of the Russian Empire. In 1854, 60 Jacobi mines were laid in the vicinity of the Forts Pavel and Alexander (Kronstadt), to deter the British Baltic Fleet from attacking them. It gradually phased out its direct competitor the Nobel mine on the insistence of Admiral Fyodor Litke. The Nobel mines were bought from Swedish industrialist Immanuel Nobel who had entered into collusion with the Russian head of navy Alexander Sergeyevich Menshikov. Despite their high cost (100 Russian rubles) the Nobel mines proved to be faulty, exploding while being laid, failing to explode or detaching from their wires, and drifting uncontrollably, at least 70 of them were subsequently disarmed by the British. In 1855, 301 more Jacobi mines were laid around Krostadt and Lisy Nos. British ships did not dare to approach them.[20]

In the 19th century, mines were called torpedoes, a name probably conferred by Robert Fulton after the torpedo fish, which gives powerful electric shocks. A spar torpedo was a mine attached to a long pole and detonated when the ship carrying it rammed another one and withdrew a safe distance. The submarine H. L. Hunley used one to sink USS Housatonic on 17 February 1864. A Harvey torpedo was a type of floating mine towed alongside a ship and was briefly in service in the Royal Navy in the 1870s. Other "torpedoes" were attached to ships or propelled themselves. One such weapon called the Whitehead torpedo after its inventor, caused the word "torpedo" to apply to self-propelled underwater missiles as well as to static devices. These mobile devices were also known as "fish torpedoes".

The American Civil War of 1861–1865 also saw the successful use of mines. The first ship sunk by a mine, USS Cairo, foundered in 1862 in the Yazoo River. Rear Admiral David Farragut's famous command during the Battle of Mobile Bay in 1864, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!"[note 1] refers to a minefield laid at Mobile, Alabama.

After 1865 the United States adopted the mine as its primary weapon for coastal defense. In the decade following 1868, Major Henry Larcom Abbot carried out a lengthy set of experiments to design and test moored mines that could be exploded on contact or be detonated at will as enemy shipping passed near them. This initial development of mines in the United States took place under the purview of the US Army Corps of Engineers, which trained officers and men in their use at the Engineer School of Application at Willets Point, New York (later named Fort Totten). In 1901 underwater minefields became the responsibility of the US Army's Artillery Corps, and in 1907 this was a founding responsibility of the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps.[21]

The Imperial Russian Navy, a pioneer in mine warfare, successfully deployed mines against the Ottoman Navy during both the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878).[22]

During the War of the Pacific (1879-1883), the Peruvian Navy, at a time when the Chilean squadron was blockading the Peruvian ports, formed a brigade of torpedo boats under the command of the frigate captain Leopoldo Sánchez Calderón and the Peruvian engineer Manuel Cuadros, who perfected the naval torpedo or mine system to be electrically activated when the cargo weight was lifted. This system was employed on 3 July 1880, in front of the port of Callao, when the gunned transport Loa was sunk while capturing a sloop mined by the Peruvians. A similar fate occurred to the gunboat schooner Covadonga in front of the port of Chancay, on 13 September 1880 when a captured pleasure boat exploded while being hoisted on its side.[23]

During the Battle of Tamsui (1884), in the Keelung Campaign of the Sino-French War, Chinese forces in Taiwan under Liu Mingchuan took measures to reinforce Tamsui against the French; they planted nine torpedo mines in the river and blocked the entrance.[24]

Early 20th century

[edit]During the Boxer Rebellion, Imperial Chinese forces deployed a command-detonated mine field at the mouth of the Hai River before the Dagu forts, to prevent the western Allied forces from sending ships to attack.[25][26]

The next major use of mines was during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905. Two mines blew up when the Petropavlovsk struck them near Port Arthur, sending the holed vessel to the bottom and killing the fleet commander, Admiral Stepan Makarov, and most of his crew in the process. The toll inflicted by mines was not confined to the Russians, however. The Japanese Navy lost two battleships, four cruisers, two destroyers and a torpedo-boat to offensively laid mines during the war. Most famously, on 15 May 1904, the Russian minelayer Amur planted a 50-mine minefield off Port Arthur and succeeded in sinking the Japanese battleships Hatsuse and Yashima.

Following the end of the Russo-Japanese War, several nations attempted to have mines banned as weapons of war at the Hague Peace Conference (1907).[22]

Many early mines were fragile and dangerous to handle, as they contained glass containers filled with nitroglycerin or mechanical devices that activated a blast upon tipping. Several mine-laying ships were destroyed when their cargo exploded.[27]

Beginning around the start of the 20th century, submarine mines played a major role in the defense of US harbours against enemy attacks as part of the Endicott and Taft Programs. The mines employed were controlled mines, anchored to the bottoms of the harbours, and detonated under control from large mine casemates onshore.

During World War I, mines were used extensively to defend coasts, coastal shipping, ports and naval bases around the globe. The Germans laid mines in shipping lanes to sink merchant and naval vessels serving Britain. The Allies targeted the German U-boats in the Strait of Dover and the Hebrides. In an attempt to seal up the northern exits of the North Sea, the Allies developed the North Sea Mine Barrage. During a period of five months from June 1918, almost 70,000 mines were laid spanning the North Sea's northern exits. The total number of mines laid in the North Sea, the British East Coast, Straits of Dover, and Heligoland Bight is estimated at 190,000 and the total number during the whole of WWI was 235,000 sea mines.[28] Clearing the barrage after the war took 82 ships and five months, working around the clock.[29] It was also during World War I, that the British hospital ship, HMHS Britannic, became the largest vessel ever sunk by a naval mine[citation needed]. The Britannic was the sister ship of the RMS Titanic, and the RMS Olympic.[30]

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, the U-boat fleet, which dominated much of the battle of the Atlantic, was small at the beginning of the war and much of the early action by German forces involved mining convoy routes and ports around Britain. German submarines also operated in the Mediterranean Sea, in the Caribbean Sea, and along the US coast.

Initially, contact mines (requiring a ship to physically strike a mine to detonate it) were employed, usually tethered at the end of a cable just below the surface of the water. Contact mines usually blew a hole in ships' hulls. By the beginning of World War II, most nations had developed mines that could be dropped from aircraft, some of which floated on the surface, making it possible to lay them in enemy harbours. The use of dredging and nets was effective against this type of mine, but this consumed valuable time and resources and required harbours to be closed.

Later, some ships survived mine blasts, limping into port with buckled plates and broken backs. This appeared to be due to a new type of mine, detecting ships by their proximity to the mine (an influence mine) and detonating at a distance, causing damage with the shock wave of the explosion. Ships that had successfully run the gantlet of the Atlantic crossing were sometimes destroyed entering freshly cleared British harbours. More shipping was being lost than could be replaced, and Churchill ordered the intact recovery of one of these new mines to be of the highest priority.

The British experienced a stroke of luck in November 1939, when a German mine was dropped from an aircraft onto the mudflats off Shoeburyness during low tide. Additionally, the land belonged to the army and a base with men and workshops was at hand. Experts were dispatched from HMS Vernon to investigate the mine. The Royal Navy knew that mines could use magnetic sensors, Britain having developed magnetic mines in World War I, so everyone removed all metal, including their buttons, and made tools of non-magnetic brass.[31] They disarmed the mine and rushed it to the labs at HMS Vernon, where scientists discovered that the mine had a magnetic arming mechanism. A large ferrous object passing through the Earth's magnetic field will concentrate the field through it, due to its magnetic permeability; the mine's detector was designed to trigger as a ship passed over when the Earth's magnetic field was concentrated in the ship and away from the mine. The mine detected this loss of the magnetic field which caused it to detonate. The mechanism had an adjustable sensitivity, calibrated in milligauss.

From this data, known methods were used to clear these mines. Early methods included the use of large electromagnets dragged behind ships or below low-flying aircraft (a number of older bombers like the Vickers Wellington were used for this). Both of these methods had the disadvantage of "sweeping" only a small strip. A better solution was found in the "Double-L Sweep"[32] using electrical cables dragged behind ships that passed large pulses of current through the seawater. This created a large magnetic field and swept the entire area between the two ships. The older methods continued to be used in smaller areas. The Suez Canal continued to be swept by aircraft, for instance.

While these methods were useful for clearing mines from local ports, they were of little or no use for enemy-controlled areas. These were typically visited by warships, and the majority of the fleet then underwent a massive degaussing process, where their hulls had a slight "south" bias induced into them which offset the concentration-effect almost to zero.

Initially, major warships and large troopships had a copper degaussing coil fitted around the perimeter of the hull, energized by the ship's electrical system whenever in suspected magnetic-mined waters. Some of the first to be so fitted were the carrier HMS Ark Royal and the liners RMS Queen Mary and RMS Queen Elizabeth. It was a photo of one of these liners in New York harbour, showing the degaussing coil, which revealed to German Naval Intelligence the fact that the British were using degaussing methods to combat their magnetic mines.[33] This was felt to be impractical for smaller warships and merchant vessels, mainly because the ships lacked the generating capacity to energise such a coil. It was found that "wiping" a current-carrying cable up and down a ship's hull[34] temporarily canceled the ships' magnetic signature sufficiently to nullify the threat. This started in late 1939, and by 1940 merchant vessels and the smaller British warships were largely immune for a few months at a time until they once again built up a field.

The cruiser HMS Belfast is just one example of a ship that was struck by a magnetic mine during this time. On 21 November 1939, a mine broke her keel, which damaged her engine and boiler rooms, as well as injuring 46 men, one later died from his injuries. She was towed to Rosyth for repairs. Incidents like this resulted in many of the boats that sailed to Dunkirk being degaussed in a marathon four-day effort by degaussing stations.[35]

The Allies and Germany deployed acoustic mines in World War II, against which even wooden-hulled ships (in particular minesweepers) remained vulnerable.[36] Japan developed sonic generators to sweep these; the gear was not ready by war's end.[36] The primary method Japan used was small air-delivered bombs. This was profligate and ineffectual; used against acoustic mines at Penang, 200 bombs were needed to detonate just 13 mines.[36]

The Germans developed a pressure-activated mine and planned to deploy it as well, but they saved it for later use when it became clear the British had defeated the magnetic system. The US also deployed these, adding "counters" which would allow a variable number of ships to pass unharmed before detonating.[36] This made them a great deal harder to sweep.[36]

Mining campaigns could have devastating consequences. The US effort against Japan, for instance, closed major ports, such as Hiroshima, for days,[37] and by the end of the Pacific War had cut the amount of freight passing through Kobe–Yokohama by 90%.[37]

When the war ended, more than 25,000 US-laid mines were still in place, and the Navy proved unable to sweep them all, limiting efforts to critical areas.[38] After sweeping for almost a year, in May 1946, the Navy abandoned the effort with 13,000 mines still unswept.[38] Over the next thirty years, more than 500 minesweepers (of a variety of types) were damaged or sunk clearing them.[38]

The US began adding delay counters to their magnetic mines in June 1945.[39]

Cold War era

[edit]

Since World War II, mines have damaged 14 United States Navy ships, whereas air and missile attacks have damaged four. During the Korean War, mines laid by North Korean forces caused 70% of the casualties suffered by US naval vessels and caused 4 sinkings.[40]

During the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 to 1988, the belligerents mined several areas of the Persian Gulf and nearby waters. On 24 July 1987, the supertanker SS Bridgeton was mined by Iran near Farsi Island. On 14 April 1988, USS Samuel B. Roberts struck an Iranian mine in the central Persian Gulf shipping lane, wounding 10 sailors.

In the summer of 1984, magnetic sea mines damaged at least 19 ships in the Red Sea. The US concluded Libya was probably responsible for the minelaying.[41] In response the US, Britain, France, and three other nations[42] launched Operation Intense Look, a minesweeping operation in the Red Sea involving more than 46 ships.[43]

On the orders of the Reagan administration, the CIA mined Nicaragua's Sandino port in 1984 in support of the Contras.[44] A Soviet tanker was among the ships damaged by these mines.[45] In 1986, in the case of Nicaragua v. United States, the International Court of Justice ruled that this mining was a violation of international law.

Post Cold War

[edit]During the Gulf War, Iraqi naval mines severely damaged USS Princeton and USS Tripoli.[46] When the war concluded, eight countries conducted clearance operations.[42]

Houthi forces in the Yemeni Civil War have made frequent use of naval mines, laying over 150 in the Red Sea throughout the conflict.[47]

In the first month of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Ukraine accused Russia of deliberately employing drifting mines in the Black Sea area. Around the same time, Turkish and Romanian military diving teams were involved in defusing operations, when stray mines were spotted near the coasts of these countries. London P&I Club issued a warning to freight ships in the area, advising them to "maintain lookouts for mines and pay careful attention to local navigation warnings".[48] Ukrainian forces have mined "from the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea which banks the critical city of Odesa."[49]

Types

[edit]

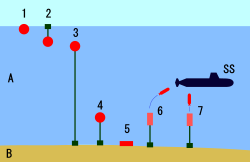

A-underwater, B-bottom, SS-submarine. 1-drifting mine, 2-drifting mine, 3-moored mine (long wire), 4-moored mine (short wire), 5-bottom mines, 6-torpedo mine/CAPTOR mine, 7-rising mine

Naval mines may be classified into three major groups; contact, remote and influence mines.

Contact mines

[edit]The earliest mines were usually of this type. They are still used today, as they are extremely low cost compared to any other anti-ship weapon and are effective, both as a psychological weapon and as a method to sink enemy ships. Contact mines need to be touched by the target before they detonate, limiting the damage to the direct effects of the explosion and usually affecting only the vessel that triggers them.

Early mines had mechanical mechanisms to detonate them, but these were superseded in the 1870s by the "Hertz horn" (or "chemical horn"), which was found to work reliably even after the mine had been in the sea for several years. The mine's upper half is studded with hollow lead protuberances, each containing a glass vial filled with sulfuric acid. When a ship's hull crushes the metal horn, it cracks the vial inside it, allowing the acid to run down a tube and into a lead–acid battery which until then contained no acid electrolyte. This energizes the battery, which detonates the explosive.[50]

Earlier forms of the detonator employed a vial of sulfuric acid surrounded by a mixture of potassium perchlorate and sugar. When the vial was crushed, the acid ignited the perchlorate-sugar mix, and the resulting flame ignited the gunpowder charge.[51]

During the initial period of World War I, the Royal Navy used contact mines in the English Channel and later in large areas of the North Sea to hinder patrols by German submarines. Later, the American antenna mine was widely used because submarines could be at any depth from the surface to the seabed. This type of mine had a copper wire attached to a buoy that floated above the explosive charge which was weighted to the seabed with a steel cable. If a submarine's steel hull touched the copper wire, the slight voltage change caused by contact between two dissimilar metals was amplified[clarification needed] and detonated the explosives.[50]

Limpet mines

[edit]Limpet mines are a special form of contact mine that are manually attached to the target by magnets and remain in place. They are named because of the similarity to the limpet, a mollusk.

Moored contact mines

[edit]

Generally, this type of mine is set to float just below the surface of the water or as deep as five meters. A steel cable connecting the mine to an anchor on the seabed prevents it from drifting away. The explosive and detonating mechanism is contained in a buoyant metal or plastic shell. The depth below the surface at which the mine floats can be set so that only deep draft vessels such as aircraft carriers, battleships or large cargo ships are at risk, saving the mine from being used on a less valuable target. In littoral waters it is important to ensure that the mine does not become visible when the sea level falls at low tide, so the cable length is adjusted to take account of tides. During WWII there were mines that could be moored in 300 m-deep (980 ft) water.

Floating mines typically have a mass of around 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives e.g. TNT, minol or amatol.[52]

Moored contact mines with plummet

[edit]

A special form of moored contact mines are those equipped with a plummet. When the mine is launched (1), the mine with the anchor floats first and the lead plummet sinks from it (2). In doing so, the plummet unwinds a wire, the deep line, which is used to set the depth of the mine below the water surface before it is launched (3). When the deep line has been unwound to a set length, the anchor is flooded and the mine is released from the anchor (4). The anchor begins to sink and the mooring cable unwinds until the plummet reaches the sea floor (5). Triggered by the decreasing tension on the deep line, the mooring cable is clamped. The anchor continues sinking down to the bottom of the sea, pulling the mine below the water surface to a depth equal to the length of the deep line (6). Thus, even without knowing the exact seafloor depth, an exact depth of the mine below the water surface can be set, limited only by the maximum length of the mooring cable.

Drifting contact mines

[edit]Drifting mines were occasionally used during World War I and World War II. However, they were more feared than effective. Sometimes floating mines break from their moorings and become drifting mines; modern mines are designed to deactivate in this event. After several years at sea, the deactivation mechanism might not function as intended and the mines may remain live. Admiral Jellicoe's British fleet did not pursue and destroy the outnumbered German High Seas Fleet when it turned away at the Battle of Jutland because he thought they were leading him into a trap: he believed it possible that the Germans were either leaving floating mines in their wake, or were drawing him towards submarines, although neither of these was the case.

After World War I the drifting contact mine was banned, but was occasionally used during World War II. The drifting mines were much harder to remove than tethered mines after the war, and they caused about the same damage to both sides.[53]

Churchill promoted "Operation Royal Marine" in 1940 and again in 1944 where floating mines were put into the Rhine in France to float down the river, becoming active after a time calculated to be long enough to reach German territory.

Remotely controlled mines

[edit]Frequently used in combination with coastal artillery and hydrophones, controlled mines (or command detonation mines) can be in place in peacetime, which is a huge advantage in blocking important shipping routes. The mines can usually be turned into "normal" mines with a switch (which prevents the enemy from simply capturing the controlling station and deactivating the mines), detonated on a signal or be allowed to detonate on their own. The earliest ones were developed around 1812 by Robert Fulton. The first remotely controlled mines were moored mines used in the American Civil War, detonated electrically from shore. They were considered superior to contact mines because they did not put friendly shipping at risk.[54] The extensive American fortifications program initiated by the Board of Fortifications in 1885 included remotely controlled mines, which were emplaced or in reserve from the 1890s until the end of World War II.[55]

Modern examples usually weigh 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives (TNT or torpex).[citation needed]

Influence mines

[edit]

These mines are triggered by the influence of a ship or submarine, rather than direct contact. Such mines incorporate sensors designed to detect the presence of a vessel and detonate when it comes within the blast range of the warhead. The fuzes on such mines may incorporate one or more of the following sensors: magnetic, passive acoustic or water pressure displacement caused by the proximity of a vessel.[56]

First used during WWI, their use became more general in WWII. The sophistication of influence mine fuzes has increased considerably over the years as first transistors and then microprocessors have been incorporated into designs. Simple magnetic sensors have been superseded by total-field magnetometers. Whereas early magnetic mine fuzes would respond only to changes in a single component of a target vessel's magnetic field, a total field magnetometer responds to changes in the magnitude of the total background field (thus enabling it to better detect even degaussed ships). Similarly, the original broadband hydrophones of 1940s acoustic mines (which operate on the integrated volume of all frequencies) have been replaced by narrow-band sensors which are much more sensitive and selective. Mines can now be programmed to listen for highly specific acoustic signatures (e.g. a gas turbine powerplant or cavitation sounds from a particular design of propeller) and ignore all others. The sophistication of modern electronic mine fuzes incorporating these digital signal processing capabilities makes it much more difficult to detonate the mine with electronic countermeasures because several sensors working together (e.g. magnetic, passive acoustic and water pressure) allow it to ignore signals which are not recognised as being the unique signature of an intended target vessel.[57]

Modern influence mines such as the BAE Stonefish are computerised, with all the programmability this implies, such as the ability to quickly load new acoustic signatures into fuzes, or program them to detect a single, highly distinctive target signature. In this way, a mine with a passive acoustic fuze can be programmed to ignore all friendly vessels and small enemy vessels, only detonating when a very large enemy target passes over it. Alternatively, the mine can be programmed specifically to ignore all surface vessels regardless of size and exclusively target submarines.

Even as far back as WWII it was possible to incorporate a "ship counter" function in mine fuzes. This might set the mine to ignore the first two ships passing over it (which could be minesweepers deliberately trying to trigger mines) but detonate when the third ship passes overhead, which could be a high-value target such as an aircraft carrier or oil tanker. Even though modern mines are generally powered by a long life lithium battery, it is important to conserve power because they may need to remain active for months or even years. For this reason, most influence mines are designed to remain in a semi-dormant state until an unpowered (e.g. deflection of a mu-metal needle) or low-powered sensor detects the possible presence of a vessel, at which point the mine fuze powers up fully and the passive acoustic sensors will begin to operate for some minutes. It is possible to program computerised mines to delay activation for days or weeks after being laid. Similarly, they can be programmed to self-destruct or render themselves safe after a preset period of time. Generally, the more sophisticated the mine design, the more likely it is to have some form of anti-handling device to hinder clearance by divers or remotely piloted submersibles.[57][58]

Moored mines

[edit]The moored mine is the backbone of modern mine systems. They are deployed where water is too deep for bottom mines. They can use several kinds of instruments to detect an enemy, usually a combination of acoustic, magnetic and pressure sensors, or more sophisticated optical shadows or electro potential sensors. These cost many times more than contact mines. Moored mines are effective against most kinds of ships. As they are cheaper than other anti-ship weapons they can be deployed in large numbers, making them useful area denial or "channelizing" weapons. Moored mines usually have lifetimes of more than 10 years, and some almost unlimited. These mines usually weigh 200 kg (440 lb), including 80 kg (180 lb) of explosives (RDX). In excess of 150 kg (330 lb) of explosives the mine becomes inefficient, as it becomes too large to handle and the extra explosives add little to the mine's effectiveness.[citation needed]

Bottom mines

[edit]Bottom mines (sometimes called ground mines) are used when the water is no more than 60 meters (200 feet) deep or when mining for submarines down to around 200 meters (660 feet). They are much harder to detect and sweep, and can carry a much larger warhead than a moored mine. Bottom mines commonly use multiple types of sensors, which are less sensitive to sweeping.[58][59]

These mines usually weigh between 150 and 1,500 kg (330 and 3,300 lb), including between 125 and 1,400 kg (280 and 3,100 lb) of explosives.[60]

Unusual mines

[edit]Several specialized mines have been developed for other purposes than the common minefield.

Bouquet mine

[edit]The bouquet mine is a single anchor attached to several floating mines. It is designed so that when one mine is swept or detonated, another takes its place. It is a very sensitive construction and lacks reliability.

Anti-sweep mine

[edit]

The anti-sweep mine is a very small mine (40 kg (88 lb) warhead) with as small a floating device as possible. When the wire of a mine sweep hits the anchor wire of the mine, it drags the anchor wire along with it, pulling the mine down into contact with the sweeping wire. That detonates the mine and cuts the sweeping wire. They are very cheap and usually used in combination with other mines in a minefield to make sweeping more difficult. One type is the Mark 23 used by the United States during World War II.

Oscillating mine

[edit]The mine is hydrostatically controlled to maintain a pre-set depth below the water's surface independently of the rise and fall of the tide.

Ascending mine

[edit]The ascending mine is a floating distance mine that may cut its mooring or in some other way float higher when it detects a target. It lets a single floating mine cover a much larger depth range.

Homing mines

[edit]

These are mines containing a moving weapon as a warhead, either a torpedo or a rocket.

Rocket mine

[edit]A Russian invention, the rocket mine is a bottom distance mine that fires a homing high-speed rocket (not torpedo) upwards towards the target. It is intended to allow a bottom mine to attack surface ships as well as submarines from a greater depth. One type is the Te-1 rocket propelled mine.

Torpedo mine

[edit]A torpedo mine is a self-propelled variety, able to lie in wait for a target and then pursue it e.g. the Mark 60 CAPTOR. Generally, torpedo mines incorporate computerised acoustic and magnetic fuzes. The US Mark 24 "mine", code-named Fido, was actually an ASW homing torpedo. The mine designation was disinformation to conceal its function.

Mobile mine

[edit]The mine is propelled to its intended position by propulsion equipment such as a torpedo. After reaching its destination, it sinks to the seabed and operates like a standard mine. It differs from the homing mine in that its mobile stage is set before it lies in wait, rather than as part of the attacking phase.

One such design is the Mk 67 Submarine Launched Mobile Mine[61] (which is based on a Mark 37 torpedo), capable of traveling as far as 16 km (10 mi) through or into a channel, harbour, shallow water area, and other zones which would normally be inaccessible to craft laying the device. After reaching the target area they sink to the sea bed and act like conventionally laid influence mines.

Nuclear mine

[edit]During the Cold War, a test was conducted with a naval mine fitted with tactical nuclear warheads for the "Baker" shot of Operation Crossroads. This weapon was experimental and never went into production.[62] The Seabed Arms Control Treaty prohibits the placement of nuclear weapons on the seabed beyond a 12-mile coast zone.

Daisy-chained mine

[edit]This comprises two moored, floating contact mines which are tethered together by a length of steel cable or chain. Typically, each mine is situated approximately 18 m (60 ft) away from its neighbor, and each floats a few meters below the surface of the ocean. When the target ship hits the steel cable, the mines on either side are drawn down the side of the ship's hull, exploding on contact. In this manner it is almost impossible for target ships to pass safely between two individually moored mines. Daisy-chained mines are a very simple concept which was used during World War II. The first prototype of the Daisy-chained mine and the first combat use came in Finland, 1939.[63]

Dummy mine

[edit]Plastic drums filled with sand or concrete are periodically rolled off the side of ships as real mines are laid in large mine-fields. These inexpensive false targets (designed to be of a similar shape and size as genuine mines) are intended to slow down the process of mine clearance: a mine-hunter is forced to investigate each suspicious sonar contact on the sea bed, whether it is real or not. Often a maker of naval mines will provide both training and dummy versions of their mines.[64]

Mine laying

[edit]

Historically several methods were used to lay mines. During WWI and WWII, the Germans used U-boats to lay mines around the UK. In WWII, aircraft came into favour for mine laying with one of the largest examples being the mining of the Japanese sea routes in Operation Starvation.

Laying a minefield is a relatively fast process with specialized ships, which is today the most common method. These minelayers can carry several thousand mines[citation needed] and manoeuvre with high precision. The mines are dropped at predefined intervals into the water behind the ship. Each mine is recorded for later clearing, but it is not unusual for these records to be lost together with the ships. Therefore, many countries demand that all mining operations be planned on land and records kept so that the mines can later be recovered more easily.[65]

Other methods to lay minefields include:

- Converted merchant ships – rolled or slid down ramps

- Aircraft – descent to the water is slowed by a parachute

- Submarines – launched from torpedo tubes or deployed from specialized mine racks on the sides of the submarine

- Combat boats – rolled off the side of the boat

- Camouflaged boats – masquerading as fishing boats

- Dropping from the shore – typically smaller, shallow-water mines

- Attack divers – smaller shallow-water mines

In some cases, mines are automatically activated upon contact with the water. In others, a safety lanyard is pulled (one end attached to the rail of a ship, aircraft or torpedo tube) which starts an automatic timer countdown before the arming process is complete. Typically, the automatic safety-arming process takes some minutes to complete. This allows the people laying the mines sufficient time to move out of its activation and blast zones.[66]

Aerial mining in World War II

[edit]Germany

[edit]In the 1930s, Germany had experimented with the laying of mines by aircraft. It became a crucial element in their overall mining strategy. Aircraft had the advantage of speed, and they would never get caught in their own minefields. German mines held a large 450 kg (1,000 lb) explosive charge. From April to June 1940, the Luftwaffe laid 1,000 mines in British waters. Soviet ports were mined, as was the Arctic convoy route to Murmansk.[67] The Heinkel He 115 could carry two medium or one large mine while the Heinkel He 59, Dornier Do 18, Junkers Ju 88 and Heinkel He 111 could carry more.

Soviet Union

[edit]The USSR was relatively ineffective in its use of naval mines in WWII in comparison with its record in previous wars.[68] Small mines were developed for use in rivers and lakes, and special mines for shallow water. A very large chemical mine was designed to sink through ice with the aid of a melting compound. Special aerial mine designs finally arrived in 1943–1944, the AMD-500 and AMD-1000.[69] Various Soviet Naval Aviation torpedo bombers were pressed into the role of aerial mining in the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, including Ilyushin DB-3s, Il-4s and Lend-Lease Douglas Boston IIIs.[70]

United Kingdom

[edit]In September 1939, the UK announced the placement of extensive defensive minefields in waters surrounding the Home Islands. Offensive aerial mining operations began in April 1940 when 38 mines were laid at each of these locations: the Elbe River, the port of Lübeck and the German naval base at Kiel. In the next 20 months, mines delivered by aircraft sank or damaged 164 Axis ships with the loss of 94 aircraft. By comparison, direct aerial attacks on Axis shipping had sunk or damaged 105 vessels at a cost of 373 aircraft lost. The advantage of aerial mining became clear, and the UK prepared for it. A total of 48,000 aerial mines were laid by the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the European Theatre during World War II.[71]

United States

[edit]

As early as 1942, American mining experts such as Naval Ordnance Laboratory scientist Dr. Ellis A. Johnson, CDR USNR, suggested massive aerial mining operations against Japan's "outer zone" (Korea and northern China) as well as the "inner zone", their home islands. First, aerial mines would have to be developed further and manufactured in large numbers. Second, laying the mines would require a sizable air group. The US Army Air Forces had the carrying capacity but considered mining to be the navy's job. The US Navy lacked suitable aircraft. Johnson set about convincing General Curtis LeMay of the efficacy of heavy bombers laying aerial mines.[72]

B-24 Liberators, PBY Catalinas and other bomber aircraft took part in localized mining operations in the Southwest Pacific and the China Burma India (CBI) theaters, beginning with a successful attack on the Yangon River in February 1943. Aerial minelaying operations involved a coalition of British, Australian and American aircrews, with the RAF and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) carrying out 60% of the sorties and the USAAF and US Navy covering 40%. Both British and American mines were used. Japanese merchant shipping suffered tremendous losses, while Japanese mine sweeping forces were spread too thin attending to far-flung ports and extensive coastlines. Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, who directed nearly all RAAF mining operations in CBI, heartily endorsed aerial mining, writing in July 1944 that "aerial mining operations were of the order of 100 times as destructive to the enemy as an equal number of bombing missions against land targets."[73]

A single B-24 dropped three mines into Haiphong harbour in October 1943. One of those mines sank a Japanese freighter. Another B-24 dropped three more mines into the harbour in November, and a second freighter was sunk by a mine. The threat of the remaining mines prevented a convoy of ten ships from entering Haiphong, and six of those ships were sunk by attacks before they reached a safe harbour. The Japanese closed Haiphong to all steel-hulled ships for the remainder of the war after another small ship was sunk by one of the remaining mines, although they may not have realized no more than three mines remained.[4]

Using Grumman TBF Avenger torpedo bombers, the US Navy mounted a direct aerial mining attack on enemy shipping in Palau on 30 March 1944 in concert with simultaneous conventional bombing and strafing attacks. The dropping of 78 mines deterred 32 Japanese ships from escaping Koror harbour, and 23 of those immobilized ships were sunk in a subsequent bombing raid.[4] The combined operation sank or damaged 36 ships.[74] Two Avengers were lost, and their crews were recovered.[75] The mines brought port usage to a halt for 20 days. Japanese mine sweeping was unsuccessful; and the Japanese abandoned Palau as a base[73] when their first ship attempting to traverse the swept channel was damaged by a mine detonation.[4]

In March 1945, Operation Starvation began in earnest, using 160 of LeMay's B-29 Superfortress bombers to attack Japan's inner zone. Almost half of the mines were the US-built Mark 25 model, carrying 570 kg (1,250 lb) of explosives and weighing about 900 kg (2,000 lb). Other mines used included the smaller 500 kg (1,000 lb) Mark 26.[73] Fifteen B-29s were lost while 293 Japanese merchant ships were sunk or damaged.[76] Twelve thousand aerial mines were laid, a significant barrier to Japan's access to outside resources. Prince Fumimaro Konoe said after the war that the aerial mining by B-29s had been "equally as effective as the B-29 attacks on Japanese industry at the closing stages of the war when all food supplies and critical material were prevented from reaching the Japanese home islands."[77] The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific War) concluded that it would have been more efficient to combine the United States's effective anti-shipping submarine effort with land- and carrier-based air power to strike harder against merchant shipping and begin a more extensive aerial mining campaign earlier in the war. Survey analysts projected that this would have starved Japan, forcing an earlier end to the war.[78] After the war, Dr. Johnson looked at the Japan inner zone shipping results, comparing the total economic cost of submarine-delivered mines versus air-dropped mines and found that, though 1 in 12 submarine mines connected with the enemy as opposed to 1 in 21 for aircraft mines, the aerial mining operation was about ten times less expensive per enemy ton sunk.[79]

Clearing WWII aerial mines

[edit]Between 600,000 and 1,000,000 naval mines of all types were laid in WWII. Advancing military forces worked to clear mines from newly-taken areas, but extensive minefields remained in place after the war. Air-dropped mines had an additional problem for mine sweeping operations: they were not meticulously charted. In Japan, much of the B-29 mine-laying work had been performed at high altitude, with the drifting on the wind of mines carried by parachute adding a randomizing factor to their placement. Generalized danger areas were identified, with only the quantity of mines given in detail. Mines used in Operation Starvation were supposed to be self-sterilizing, but the circuit did not always work. Clearing the mines from Japanese waters took so many years that the task was eventually given to the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force.[80]

For the purpose of clearing all types of naval mines, the Royal Navy employed German crews and minesweepers from June 1945 to January 1948,[81] organised in the German Mine Sweeping Administration (GMSA), which consisted of 27,000 members of the former Kriegsmarine and 300 vessels.[82] Mine clearing was not always successful: a number of ships were damaged or sunk by mines after the war. Two such examples were the liberty ships Pierre Gibault which was scrapped after hitting a mine in a previously cleared area off the Greek island of Kythira in June 1945,[83] and Nathaniel Bacon which hit a minefield off Civitavecchia, Italy in December 1945, caught fire, was beached, and broke in two.[84]

Damage

[edit]The damage that may be caused by a mine depends on the "shock factor value", a combination of the initial strength of the explosion and of the distance between the target and the detonation. When taken in reference to ship hull plating, the term "Hull Shock Factor" (HSF) is used, while keel damage is termed "Keel Shock Factor" (KSF). If the explosion is directly underneath the keel, then HSF is equal to KSF, but explosions that are not directly underneath the ship will have a lower value of KSF.[85]

Direct damage

[edit]Usually only created by contact mines, direct damage is a hole blown in the ship. Among the crew, fragmentation wounds are the most common form of damage. Flooding typically occurs in one or two main watertight compartments, which can sink smaller ships or disable larger ones. Contact mine damage often occurs at or close to the waterline near the bow,[85] but depending on circumstances a ship could be hit anywhere on its outer hull surface (the USS Samuel B. Roberts mine attack being a good example of a contact mine detonating amidships and underneath the ship).

Bubble jet effect

[edit]The bubble jet effect occurs when a mine or torpedo detonates in the water a short distance away from the targeted ship. The explosion creates a bubble in the water, and due to the difference in pressure, the bubble will collapse from the bottom. The bubble is buoyant, and so it rises towards the surface. If the bubble reaches the surface as it collapses, it can create a pillar of water that can go over a hundred meters into the air (a "columnar plume"). If conditions are right and the bubble collapses onto the ship's hull, the damage to the ship can be extremely serious; the collapsing bubble forms a high-energy jet similar to a shaped charge that can break a metre-wide hole straight through the ship, flooding one or more compartments, and is capable of breaking smaller ships apart. The crew in the areas hit by the pillar are usually killed instantly. Other damage is usually limited.[85]

The Baengnyeong incident, in which the ROKS Cheonan broke in half and sank off the coast South Korea in 2010, was caused by the bubble jet effect, according to an international investigation.[86][87]

Shock effect

[edit]If the mine detonates at a distance from the ship, the change in water pressure causes the ship to resonate. This is frequently the most deadly type of explosion, if it is strong enough.[citation needed] The whole ship is dangerously shaken and everything on board is tossed around. Engines rip from their beds, cables from their holders, etc.[clarification needed] A badly shaken ship usually sinks quickly, with hundreds, or even thousands[example needed] of small leaks all over the ship and no way to power the pumps. The crew fare no better, as the violent shaking tosses them around.[85] This shaking is powerful enough to cause disabling injury to knees and other joints in the body, particularly if the affected person stands on surfaces connected directly to the hull (such as steel decks).

The resulting gas cavitation and shock-front-differential over the width of the human body is sufficient to stun or kill divers.[88]

Countermeasures

[edit]

Weapons are frequently a few steps ahead of countermeasures, and mines are no exception. In this field the British, with their large seagoing navy, have had the bulk of world experience, and most anti-mine developments, such as degaussing and the double-L sweep, were British inventions. When on operational missions, such as the invasion of Iraq, the US still relies on British and Canadian minesweeping services. The US has worked on some innovative mine-hunting countermeasures, such as the use of military dolphins to detect and flag mines. Mines in nearshore environments remain a particular challenge. They are small and as technology has developed they can have anechoic coatings, be non-metallic, and oddly shaped to resist detection.[89]: 18 Further, oceanic conditions and the sea bottoms of the area of operations can degrade sweeping and hunting efforts.[89]: 18 Mining countermeasures are far more expensive and time-consuming than mining operations, and that gap is only growing with new technologies.[89]: 18

Passive countermeasures

[edit]Ships can be designed to be difficult for mines to detect, to avoid detonating them. This is especially true for minesweepers and mine hunters that work in minefields, where a minimal signature outweighs the need for armour and speed. These ships have hulls of glass fibre or wood instead of steel to avoid magnetic signatures. These ships may use special propulsion systems, with low magnetic electric motors, to reduce magnetic signature, and Voith-Schneider propellers, to limit the acoustic signature. They are built with hulls that produce a minimal pressure signature. These measures create other problems. They are expensive, slow, and vulnerable to enemy fire. Many modern ships have a mine-warning sonar—a simple sonar looking forward and warning the crew if it detects possible mines ahead. It is only effective when the ship is moving slowly.

(See also SQQ-32 Mine-hunting sonar)

A steel-hulled ship can be degaussed (more correctly, de-oerstedted or depermed) using a special degaussing station that contains many large coils and induces a magnetic field in the hull with alternating current to demagnetize the hull. This is a rather problematic solution, as magnetic compasses need recalibration and all metal objects must be kept in exactly the same place. Ships slowly regain their magnetic field as they travel through the Earth's magnetic field, so the process has to be repeated every six months.[90]

A simpler variation of this technique called wiping, was developed by Charles F. Goodeve which saved time and resources.

Between 1941 and 1943 the US Naval Gun factory (a division of the Naval Ordnance Laboratory) in Washington, D.C., built physical models of all US naval ships. Three kinds of steel were used in shipbuilding: mild steel for bulkheads, a mixture of mild steel and high tensile steel for the hull, and special treatment steel for armor plate. The models were placed within coils which could simulate the Earth's magnetic field at any location. The magnetic signatures were measured with degaussing coils. The objective was to reduce the vertical component of the combination of the Earth's field and the ship's field at the usual depth of German mines. From the measurements, coils were placed and coil currents were determined to minimize the chance of detonation for any ship at any heading at any latitude.[91]

Some ships are built with magnetic inductors, large coils placed along the ship to counter the ship's magnetic field. Using magnetic probes in strategic parts of the ship, the strength of the current in the coils can be adjusted to minimize the total magnetic field. This is a heavy and clumsy solution, suited only to small-to-medium-sized ships. Boats typically lack the generators and space for the solution, while the amount of power needed to overcome the magnetic field of a large ship is impractical.[91]

Active countermeasures

[edit]Active countermeasures are ways to clear a path through a minefield or remove it completely. This is one of the most important tasks of any mine warfare flotilla.

Mine sweeping

[edit]

A sweep is either a contact sweep, a wire dragged through the water by one or two ships to cut the mooring wire of floating mines, or a distance sweep that mimics a ship to detonate the mines. The sweeps are dragged by minesweepers, either purpose-built military ships or converted trawlers. Each run covers between one hundred and two hundred metres (330 and 660 ft), and the ships must move slowly in a straight line, making them vulnerable to enemy fire. This was exploited by the Turkish army in the Battle of Gallipoli in 1915, when mobile howitzer batteries prevented the British and French from clearing a way through minefields.

If a contact sweep hits a mine, the wire of the sweep rubs against the mooring wire until it is cut. Sometimes "cutters", explosive devices to cut the mine's wire, are used to lessen the strain on the sweeping wire. Mines cut free are recorded and collected for research or shot with a deck gun.[92]

Minesweepers protect themselves with an oropesa or paravane instead of a second minesweeper. These are torpedo-shaped towed bodies, similar in shape to a Harvey torpedo, that are streamed from the sweeping vessel thus keeping the sweep at a determined depth and position. Some large warships were routinely equipped with paravane sweeps near the bows in case they inadvertently sailed into minefields—the mine would be deflected towards the paravane by the wire instead of towards the ship by its wake. More recently, heavy-lift helicopters have dragged minesweeping sleds, as in the 1991 Persian Gulf War.[93]

The distance sweep mimics the sound and magnetism of a ship and is pulled behind the sweeper. It has floating coils and large underwater drums. It is the only sweep effective against bottom mines.

During WWII, RAF Coastal Command used Vickers Wellington bombers Wellington DW.Mk I fitted with degaussing coils to trigger magnetic mines.[94] In a parallel development the Luftwaffe adapted some Junkers 52/3m aircraft to also carry a coil operated by electricity supplied from an onboard generator. The Luftwaffe called this adaption Minensuch(e) (lit. mine-search).[95] In both cases pilots were required to fly at low altitude (up to about 200 feet above the sea) and at fairly low speeds to be effective.

Modern influence mines are designed to discriminate against false inputs and are, therefore, much harder to sweep. They often contain inherent anti-sweeping mechanisms. For example, they may be programmed to respond to the unique noise of a particular ship-type, its associated magnetic signature and the typical pressure displacement of such a vessel. As a result, a mine-sweeper must accurately mimic the required target signature to trigger detonation. The task is complicated by the fact that an influence mine may have one or more of a hundred different potential target signatures programmed into it.[96]

Another anti-sweeping mechanism is a ship-counter in the mine fuze. When enabled, this allows detonation only after the mine fuze has been triggered a pre-set number of times. To further complicate matters, influence mines may be programmed to arm themselves (or disarm automatically—known as self-sterilization) after a pre-set time. During the pre-set arming delay (which could last days or even weeks) the mine would remain dormant and ignore any target stimulus, whether genuine or false.[96]

When influence mines are laid in an ocean minefield, they may have various combinations of fuze settings configured. For example, some mines (with the acoustic sensor enabled) may become active within three hours of being laid, others (with the acoustic and magnetic sensors enabled) may become active after two weeks but have the ship-counter mechanism set to ignore the first two trigger events, and still others in the same minefield (with the magnetic and pressure sensors enabled) may not become armed until three weeks have passed. Groups of mines within this mine-field may have different target signatures which may or may not overlap. The fuzes on influence mines allow many different permutations, which complicates the clearance process.[96]

Mines with ship-counters, arming delays and highly specific target signatures in mine fuzes can falsely convince a belligerent that a particular area is clear of mines or has been swept effectively because a succession of vessels have already passed through safely.

Minehunting

[edit]

As naval mines have become more sophisticated, and able to discriminate between targets, so they have become more difficult to deal with by conventional sweeping. This has given rise to the practice of minehunting. Minehunting is very different from sweeping, although some minehunters, known as mine countermeasures vessels (MCMVs) can do both tasks. Minehunters use specialized high-frequency sonars and high fidelity sidescaning sonar to locate mines, which are then inspected and destroyed either by divers or ROVs (remote controlled unmanned mini-submarines).[89]: 18 It is slow, but also the most reliable way to remove mines, as it circumvents most anti-minesweeping countermeasures. Minehunting started during the Second World War, but it was only after the war that it became truly effective.

Sea mammals (mainly the bottlenose dolphin) have been trained to hunt and mark mines, most famously by the US Navy Marine Mammal Program. Mine-clearance dolphins were deployed in the Persian Gulf during the Iraq War in 2003. The US Navy claims that these dolphins were effective in helping to clear more than 100 antiship mines and underwater booby traps from Umm Qasr Port.[97]

French naval officer Jacques Yves Cousteau's Undersea Research Group was once involved in minehunting operations: They removed or detonated a variety of German mines, but one particularly defusion-resistant batch—equipped with acutely sensitive pressure, magnetic, and acoustic sensors and wired together so that one explosion would trigger the rest—was simply left undisturbed for years until corrosion would (hopefully) disable the mines.[98]

Mine running

[edit]

A more drastic method is simply to run a ship through the minefield, letting other ships safely follow the same path. An early example of this was Farragut's actions at Mobile Bay during the American Civil War. However, as mine warfare became more developed this method became uneconomical. This method was revived by the German Imperial German Navy during World War I. Left with a surfeit of idle ships due to the Allied blockade, the Germans introduced a ship known as Sperrbrecher ("block breaker"). The type was also used during World War II. Typically an old cargo ship, loaded with cargo that made her less vulnerable to sinking (wood for example), the Sperrbrecher was run ahead of the ship to be protected, detonating any mines that might be in their path. The use of Sperrbrecher obviated the need to continuous and painstaking sweeping, but the cost was high. Over half the 100 or so ships used as Sperrbrecher in WWII were sunk during the war. Alternatively, a shallow draught vessel can be steamed through the minefield at high speed to generate a pressure wave sufficient to trigger mines, with the minesweeper moving fast enough to be sufficiently clear of the pressure wave so that triggered mines do not destroy the ship itself. These techniques are the only way to sweep pressure mines that is publicly known to be employed. The technique can be simply countered by use of a ship-counter, set to allow a certain number of passes before the mine is actually triggered. Modern doctrine calls for ground mines to be hunted rather than swept. A new system is being introduced for sweeping pressure mines, however counters are going to remain a problem.[99][100]

An updated form of this method is the use of small unmanned ROVs (such as the Seehund drone) that simulate the acoustic and magnetic signatures of larger ships and are built to survive exploding mines. Repeated sweeps would be required in case one or more of the mines had its "ship counter" facility enabled i.e. were programmed to ignore the first 2, 3, or even 6 target activations.

Counter-mining

[edit]Another expedient for clearing mines, especially in a hurry, is counter-mining. By this method an explosive is detonated in the area of a known or suspected minefield and the blast either trips off the fuzes or the actual explosive contained within the mine or mines. This latter is known as a sympathetic detonation. Counter-mining is normally used as a last resort or if other equipment is not available. One example was at the entrance to Grand Harbour, Valletta, Malta in WW2 when the British dropped depth charges into the harbour entrance to detonate suspected mines prior to the arrival of an important convoy. It is especially useful against acoustic or pressure mines due to their activation by sound or increases in water pressure.

National arsenals

[edit]US mines

[edit]The United States Navy MK56 ASW mine (the oldest still in use by the United States) was developed in 1966. More advanced mines include the MK60 CAPTOR (short for "encapsulated torpedo"), the MK62 and MK63 Quickstrike and the MK67 SLMM (Submarine Launched Mobile Mine). Today, most US naval mines are delivered by aircraft.

MK67 SLMM Submarine Launched Mobile Mine

The SLMM was developed by the United States as a submarine deployed mine for use in areas inaccessible for other mine deployment techniques or for covert mining of hostile environments. The SLMM is a shallow-water mine and is basically a modified Mark 37 torpedo.

General characteristics

- Type: Submarine-laid bottom mine

- Detection System: Magnetic/seismic/pressure target detection devices (TDDs)

- Dimensions: 0.485 by 4.09 m (19.1 by 161.0 in)

- Depth Range: Shallow water

- Weight: 754 kg (1,662 lb)

- Explosives: 230 kg (510 lb) high explosive

- Date Deployed: 1987

MK65 Quickstrike

The Quickstrike[101] is a family of shallow-water aircraft-laid mines used by the United States, primarily against surface craft. The MK65 is a 910 kg (2,000 lb) dedicated, purpose-built mine. However, other Quickstrike versions (MK62, MK63, and MK64) are converted general-purpose bombs. These latter three mines are actually a single type of electronic fuze fitted to Mk82, Mk83 and Mk84 air-dropped bombs. Because this latter type of Quickstrike fuze only takes up a small amount of storage space compared to a dedicated sea mine, the air-dropped bomb casings have dual purpose i.e. can be fitted with conventional contact fuzes and dropped on land targets, or have a Quickstrike fuze fitted which converts them into sea mines.

General characteristics

- Type: aircraft-laid bottom mine (with descent to water slowed by a parachute or other mechanism)

- Detection System: Magnetic/seismic/pressure target detection devices (TDDs)

- Dimensions: 0.74 by 3.25 m (29 by 128 in)

- Depth Range: Shallow water

- Weight: 1,086 kg (2,394 lb)

- Explosives: Various loads

- Date Deployed: 1983

MK56

General characteristics

- Type: Aircraft laid moored mine

- Detection System: Total field magnetic exploder

- Dimensions: 0.570 by 2.9 m (22.4 by 114.2 in)[citation needed]

- Depth Range: Moderate depths

- Weight: 909 kg (2,004 lb)

- Explosives: 164 kg (362 lb) HBX-3

- Date Deployed: 1966

Royal Navy

[edit]According to a statement made to the UK Parliament in 2002:[102]

...the Royal Navy does not have any mine stocks and has not had since 1992. Notwithstanding this, the United Kingdom retains the capability to lay mines and continues research into mine exploitation. Practice mines, used for exercises, continue to be laid in order to retain the necessary skills.

However, a British company (BAE Systems) does manufacture the Stonefish influence mine for export to friendly countries such as Australia, which has both war stock and training versions of Stonefish,[103][unreliable source?] in addition to stocks of smaller Italian MN103 Manta mines.[64] The computerised fuze on a Stonefish mine contains acoustic, magnetic and water pressure displacement target detection sensors. Stonefish can be deployed by fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, surface vessels and submarines. An optional kit is available to allow Stonefish to be air-dropped, comprising an aerodynamic tail-fin section and parachute pack to retard the weapon's descent. The operating depth of Stonefish ranges between 30 and 200 metres. The mine weighs 990 kilograms and contains a 600 kilogram aluminised PBX explosive warhead.

Modern mine warfare

[edit]Mine warfare remains the most cost-effective form of asymmetrical naval warfare. Mines are relatively cheap and being small allows them to be easily deployed. Indeed, with some kinds of mines, trucks and rafts will suffice. At present there are more than 300 different mines available. Some 50 countries currently have mining ability. The number of naval mine producing countries has increased by 75% since 1988. It is also noted that these mines are of an increasing sophistication while even the older type mines present a significant problem. It has been noted that mine warfare may become an issue with terrorist organizations. Mining busy shipping straits and mining shipping harbours remain some of the most serious threats.[89]: 9

See also

[edit]- Bomb disposal

- HMHS Britannic

- Corfu Channel case

- Land mine

- Minesweeper

- Minelayer

- Destroyer minesweeper WWII

- Royal Navy's Admiralty Mining Establishment

- Royal Naval Patrol Service

- Shock factor

- Mine planter (vessel)

- Singer (naval mine)

- Submarine mines in United States harbor defense

- Stonefish influence mine

- Operation Pocket Money (aerial mining campaign against North Vietnam in 1972)

- George Gosse

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Farragut's actual wording has been recorded as, "Damn the torpedoes. Four bells, Captain Drayton, go ahead. Jouett, full speed."

Citations

[edit]- ^ McDonald, Wesley (1985). "Mine Warfare: A Pillar of Maritime Strategy". Proceedings. 111 (10). United States Naval Institute: 48.

- ^ Paul O'Mahony (16 June 2009), "Swedish navy locates German WWII mines", The Local Europe AB, archived from the original on 9 March 2016, retrieved 8 March 2016

- ^ "Isle of Wight: WW2 sea mine detonated by Navy". BBC News. 19 May 2019. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d Greer, William L.; Bartholomew, James (1986). "The Psychology of Mine Warfare". Proceedings. 112 (2). United States Naval Institute: 58–62.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 203–205.

- ^ Asiapac Editorial (2007). Origins of Chinese science and technology (3 ed.). Asiapac Books. p. 18. ISBN 978-981-229-376-3.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 205.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 199.

- ^ "Historic Figures: Cornelius Drebbel (1572–1633)". BBC History. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2007.

- ^ Robert Routledge (1989). Discoveries and inventions of the 19th century. Bracken Books. p. 161. ISBN 1-85170-267-9.

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.). Ocean Studies Board, National Research Council (U.S.). Commission on Geosciences, Environment, and Resources (2000). Oceanography and Mine Warfare. National Academies Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-309-06798-7. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gilbert, Jason A., L/Cdr, USN. "Combined Mine Countermeasures Force", Naval War College paper (Newport, RI, 2001), p. 2.

- ^ Philip. Robert Fulton. p. 161.

- ^ a b c Best. Trafalgar. p. 80.

- ^ Schiffer, Michael B. (2008). Power struggles: scientific authority and the creation of practical electricity before Edison. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-19582-9.

- ^ Youngblood, Norman (2006). The Development of Mine Warfare: A Most Murderous and Barbarous Conduct. Praeger Security International; War, technology, and history. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 29. ISBN 9780275984199. ISSN 1556-4924. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

The Crimean War (1854–1856) was the first war to see the successful use of land and sea mines, both of which were the work of Immanuel Nobel.

- ^ Nicholson, Arthur (2015). Very Special Ships: Abdiel Class Fast Minelayers of World War Two. Seaforth Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 9781848322356. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

While nosing about the defences off Kronstadt on 9 June 1855, the British paddle steamer Merlin struck first one and then another mine, giving her the dubious distinction of being the first warship damaged by enemy mines. HMS Firefly came to her assistance after the first explosion, only to strike a mine herself. [...] When HMS Vulcan struck a mine on 20 June, the Royal Navy had had enough, and the next day began carrying out the first minesweeping operation in history, recovering thirty-three 'infernal machines,' the standard British term of the day for sea mines.

- ^ Lambert, Andrew D. (1990). The Crimean War: British Grand Strategy Against Russia, 1853–56. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. (published 2011). pp. 288–289. ISBN 9781409410119. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

On 9 June Merlin, Dragon, Firefly and D'Assas took Penaud and several British captains to examine Cronstadt. While still 2 miles out the two surveying ships were struck by 'infernals'. [...] The fleet left Seskar on the 20th. Vulture, almost the last to arrive, was struck by an infernal. The following day the boats fished up several of the primitive mines, and both Dundas and Seymour inspected them aboard their flagships.

- ^ Brown. D.K., Before the Ironclad, London (1990), pp. 152–154

- ^ Tarle 1944, pp. 44–45.

- ^ "Coast Artillery: Submarine Mine Defenses". 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ a b Kowner, Rotem (2006). Historical Dictionary of the Russo-Japanese War. The Scarecrow Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-8108-4927-5.

- ^ "The Port-Hopping War". Archived from the original on 15 October 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2022.

- ^ Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2009). Maritime Taiwan: Historical Encounters with the East and the West (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 97. ISBN 978-0765623287. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ MacCloskey, Monro (1969). Reilly's Battery: a story of the Boxer Rebellion. R. Rosen Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780823901456. Retrieved 19 February 2011.(Original from the University of Wisconsin – Madison)

- ^ Slocum, Stephan L'H.; Reichmann, Carl; Chaffee, Adna Romanza (1901). Reports on military operations in South Africa and China. Adjutant-General's Office, Military Information Division, Washington, D.C., United States: GPO. p. 533. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

15 June, it was learned that the mouth of the river was protected by electric mines, that the forts at Taku were.

(Issue 143 of Document (United States. War Dept.))(Original from the New York Public Library) - ^ "Naval mine - contained explosive device placed in water to destroy ships or submarines". World Wide Inventions. 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Climate Change & Naval War—A Scientific Assessment 2005—Trafford on demand publishing, Canada/UK" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, p. 4.

- ^ "Mark Chirnside's Reception Room: Olympic, Titanic & Britannic: Olympic Interview, January 2005". Markchirnside.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022. [self-published source]

- ^ Campbell, John, "Naval Weapons of World War Two" (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1985)

- ^ "The Double-L Sweep – Biography of Sir Charles Goodeve". Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ^ Piekalkiewicz, Janusz, "Sea War: 1939–1945" (Poole, UK: Blandford Press, 1987)

- ^ "Wiping – Biography of Sir Charles Goodeve". Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ^ Wingate 2004, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b c d e Parillo, p. 200.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b Parillo, p. 201.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ a b c Gilbert, p. 5.

- ^ Parillo, Mark P. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War Two (Annapolis, Md. : Naval Institute Press, 1993), p. 200.

- ^ Marolda, Edward J. (26 August 2003). "Mine Warfare". U.S. Naval History & Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2011.