Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Passport

View on Wikipedia

A passport is a formal travel document issued by a government that certifies a person's identity and nationality for international travel.[1] A passport allows its bearer to enter and temporarily reside in a foreign country, access local aid and protection, and obtain consular assistance from their government. In addition to facilitating travel, passports are a key mechanism for border security and regulating migration; they may also serve as identity documents for various domestic purposes.

State-issued travel documents have existed in some form since antiquity; the modern passport was universally adopted and standardized in 1920.[2] The passport takes the form of a booklet bearing the name and emblem of the issuing government and containing the biographical information of the individual, including their full name, photograph, place and date of birth, and signature. A passport does not create any rights in the country being visited nor impose any obligation on the issuing country; rather, it provides certification to foreign government officials of the holder's identity and right to travel, with pages available for inserting entry and exit stamps and travel visas—endorsements that allow the individual to enter and temporarily reside in a country for a period of time and under certain conditions.

Since 1998, many countries have transitioned to biometric passports, which contain an embedded microchip to facilitate authentication and safeguard against counterfeiting.[3] As of July 2024, over 150 jurisdictions issue such "e-passports";[4] previously issued non-biometric passports usually remain valid until expiration.

Eligibility for a passport varies by jurisdiction, although citizenship is a common prerequisite. However, a passport may be issued to individuals who do not have the status or full rights of citizenship, such as American or British nationals. Likewise, certain classes of individuals, such as diplomats and government officials, may be issued special passports that provide certain rights and privileges, such as immunity from arrest or prosecution.[3]

While passports are typically issued by national governments, certain subnational entities are authorised to issue passports to citizens residing within their borders.[a] Additionally, other types of travel documents may serve a similar role to passports but are subject to different eligibility requirements, purposes, or restrictions.

History

[edit]Etymology and origin

[edit]Etymological sources[example needed] show that the term "passport" may derive from a document required by some medieval Italian states in order for an individual to pass through the physical harbor (Italian passa porto, "to pass the harbor") or gate (Italian passa porte, "to pass the gates") of a walled city or jurisdiction.[5][6] Such documents were issued by local authorities to foreign travellers—as opposed to local citizens, as is the modern practice—and generally contained a list of towns and cities the document holder was permitted to enter or pass through. On the whole, documents were not required for travel to seaports, which were considered open trading points, but documents were required to pass harbor controls and travel inland from seaports.[7] The transition from private to state control over movement was an essential aspect of the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Communal obligations to provide poor relief were an important source of the desire for controls on movement.[8]:10

Antecedents

[edit]One of the earliest known references to paperwork that served an analogous role to a passport is found in the Hebrew Bible. Nehemiah 2:7–9, dating from approximately 450 BC, states that Nehemiah, an official serving King Artaxerxes I of Persia, asked permission to travel to Judea; the king granted leave and gave him a letter "to the governors beyond the river" requesting safe passage for him as he traveled through their lands.[9]

The ancient Indian political text Arthashastra (third century BCE) mentions passes issued at the rate of one masha per pass to enter and exit the country, and describes the duties of the Mudrādhyakṣa (lit. 'Superintendent of Seals') who must issue sealed passes before a person could enter or leave the countryside.[10]

Passports were an important part of the Chinese bureaucracy as early as the Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD), if not in the Qin dynasty. They required such details as age, height, and bodily features.[11] These passports (傳; zhuan) determined a person's ability to move throughout imperial counties and through points of control. Even children needed passports, but those of one year or less who were in their mother's care may not have needed them.[11]

In the medieval Islamic Caliphate, a form of passport was the bara'a, a receipt for taxes paid. Only people who paid their zakah (for Muslims) or jizya (for dhimmis) taxes were permitted to travel to different regions of the Caliphate; thus, the bara'a receipt was a "basic passport".[12]

In the 12th century, the Republic of Genoa issued a document called Bulletta, which was issued to the nationals of the Republic who were traveling to the ports of the emporiums and the ports of the Genoese colonies overseas, as well as to foreigners who entered them.

King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what some consider the first British passport in the modern sense, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign lands. The earliest reference to these documents is found in a 1414 Act of Parliament.[13][14] In 1540, granting travel documents in England became a role of the Privy Council of England, and it was around this time that the term "passport" was used. In 1794, issuing British passports became the job of the Office of the Secretary of State.[13] In the Holy Roman Empire, the 1548 Imperial Diet of Augsburg required the public to hold imperial documents for travel, at the risk of permanent exile.[15]

In 1791, Louis XVI masqueraded as a valet during his Flight to Varennes as passports for the nobility typically included a number of persons listed by their function but without further description.[8]:31–32

A Pass-Card Treaty of October 18, 1850 among German states standardized information including issuing state, name, status, residence, and description of bearer. Tramping journeymen and jobseekers of all kinds were not to receive pass-cards.[8]:92–93

Before World War I, in most situations only adult males could receive a passport; their family members were written in their passport if they traveled with them. Even if a married woman had her own passport, she could not use it without her husband present.[16]:93–94

Modern development

[edit]A rapid expansion of railway infrastructure and wealth in Europe beginning in the mid-nineteenth century led to large increases in the volume of international travel and a consequent unique dilution of the passport system for approximately thirty years prior to World War I. The speed of trains, as well as the number of passengers that crossed multiple borders, made enforcement of passport laws difficult. The general reaction was the relaxation of passport requirements.[17] In the later part of the nineteenth century and up to World War I, passports were not required, on the whole, for travel within Europe, and crossing a border was a relatively straightforward procedure. Consequently, comparatively few people held passports.

During World War I, European governments introduced border passport requirements for security reasons, and to control the emigration of people with useful skills. These controls remained in place after the war, becoming a standard, though controversial, procedure. British tourists of the 1920s complained, especially about attached photographs and physical descriptions, which they considered led to a "nasty dehumanisation".[18] The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act was passed in 1914, clearly defining the notions of citizenship and creating a booklet form of the passport. It also made a photographs in a passport mandatory.[16]:93

In 1920, the League of Nations held a conference on passports, the Paris Conference on Passports & Customs Formalities and Through Tickets.[19] Passport guidelines and a general booklet design resulted from the conference,[20] which was followed up by conferences in 1926 and 1927.[21] The League of Nations issued Nansen passports to stateless refugees from 1922 to 1938.[22]

While the United Nations held a travel conference in 1963, no passport guidelines resulted from it. Passport standardization came about in 1980, under the auspices of the ICAO. ICAO standards include those for machine-readable passports.[23] Such passports have an area where some of the information otherwise written in textual form is written as strings of alphanumeric characters, printed in a manner suitable for optical character recognition. This enables border controllers and other law enforcement agents to process these passports more quickly, without having to input the information manually into a computer. ICAO publishes Doc 9303 Machine Readable Travel Documents, the technical standard for machine-readable passports.[24] A more recent standard is for biometric passports. These contain biometrics to authenticate the identity of travellers. The passport's critical information is stored on a small RFID computer chip, much like information stored on smartcards. Like some smartcards, the passport booklet design calls for an embedded contactless chip that is able to hold digital signature data to ensure the integrity of the passport and the biometric data.

Historically, legal authority to issue passports is founded on the exercise of each country's executive discretion. Certain legal tenets follow, namely: first, passports are issued in the name of the state; second, no person has a legal right to be issued a passport; third, each country's government, in exercising its executive discretion, has complete and unfettered discretion to refuse to issue or to revoke a passport; and fourth, that the latter discretion is not subject to judicial review. However, legal scholars including A.J. Arkelian have argued that evolutions in both the constitutional law of democratic countries and the international law applicable to all countries now render those historical tenets both obsolete and unlawful.[25][26]

-

Arabic papyrus with an exit permit, dated January 24, 722 AD, pointing to the regulation of travel activities. From Hermopolis Magna, Egypt

-

First Japanese passport, issued in 1866

-

Italian passport, issued in 1872

-

Chinese passport from the Qing dynasty, 24th Year of the Guangxu Reign, 1898

-

World War II Spanish official passport issued in late 1944 and used during the last six months of the war by an official being sent to Berlin

Types

[edit]

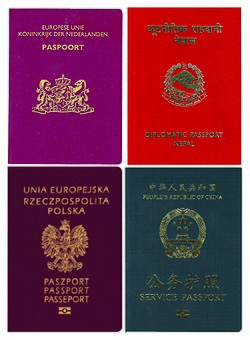

Governments around the world issue a variety of passports for different purposes. The most common variety are ordinary passports issued to individual citizens and other nationals. In the past, certain countries issued collective passports[b] or family passports.[c] Today, passports are typically issued to individual travellers rather than groups. Aside from ordinary passports issued to citizens by national governments, there are a variety of other types of passports by governments in specific circumstances.

While individuals are typically only permitted to hold one passport, certain governments permit citizens to hold more than one ordinary passport.[d] Individuals may also simultaneously hold an ordinary passport and an official or diplomatic passport.

Emergency passport

[edit]Emergency passports (also called temporary passports) are issued to persons with urgent need to travel who do not have passports, e.g. someone abroad whose passport has been lost or stolen who needs to travel home within a few days, someone whose passport expires abroad, or someone who urgently needs to travel abroad who does not have a passport with sufficient validity. These passports are intended for very short durations, e.g. to allow immediate one-way travel back to the home country. Laissez-passer are also used for this purpose.[29] Uniquely, the United Kingdom issues emergency passports to citizens of certain Commonwealth states who lose their passports in non-Commonwealth countries where their home state does not maintain a diplomatic or consular mission.

Diplomatic and official passports

[edit]Pursuant to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, and the immunity afforded to officials of a foreign state under customary international law, diplomats and other individuals travelling on government business are entitled to reduced scrutiny at border checkpoints when travelling overseas. Consequently, such individuals are typically issued special passports indicating their status. These passports come in three distinct varieties:

Diplomatic passports

[edit]- Typically issued to accredited diplomats, senior consular staff, heads of state or government, and to senior foreign ministry employees. Individuals holding diplomatic passports are usually entitled to certain degrees of immunity from border control inspections, depending on their home countries and their countries of entry.

Service/official passports

[edit]- Issued to senior government officials travelling on state business who are not eligible for diplomatic passports. Holders of official passports are typically entitled to similar immunity from border control inspections. In the United States of America, official and service passports are two distinct categories of passport, with official passports being issued to senior government officials while service passports are issued to government contractors.[e]

Public affairs passports

[edit]- Issued to Chinese citizens holding senior positions in state-owned companies. While public affairs passports do not usually entitle their bearers to exemption from searches at border checkpoints, they are subject to more liberal visa policies in several countries primarily in Africa and Asia (see: Visa requirements for Chinese citizens).

Passports without right of abode

[edit]Unlike most countries, the United Kingdom and the Republic of China issue various categories of passports to individuals without the right of abode in their territory. In the United Kingdom's case, these passports are typically issued to individuals connected with a former British colony while, in the ROC's case, these passports are the result of the legal distinction between ROC nationals with and without residence in the area it administers.[f] In both cases, holders of such passports are able to obtain residence on an equal footing with foreigners by applying for indefinite leave to remain (UK) or a resident certificate (ROC).

Republic of China (Taiwan)

[edit]

A Republic of China citizen who does not have household registration (Chinese: 戶籍; pinyin: hùjí) in the area administered by the ROC[f] is classified as a National Without Household Registration (NWOHR; Chinese: 無戶籍國民) and is subject to immigration controls when clearing ROC border controls, does not have automatic residence rights, and cannot vote in Taiwanese elections. However, they are exempt from conscription. Most individuals with this status are children born overseas to ROC citizens who do hold household registration. Additionally, because the ROC observes the principle of jus sanguinis, members of the overseas Chinese community are also regarded as citizens.[33] During the Cold War, both the ROC and PRC governments actively sought the support of overseas Chinese communities in their attempts to secure the position as the legitimate sole government of China. The ROC also encouraged overseas Chinese businessmen to settle in Taiwan to facilitate economic development and regulations concerning evidence of ROC nationality by descent were particularly lax during the period, allowing many overseas Chinese the right to settle in Taiwan.[34] About 60,000 NWOHRs currently hold Taiwanese passports with this status.[35]

United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom issues several similar but distinct passports which correspond to the country's several categories of nationality. Full British citizens are issued a standard British passport. British citizens resident in the Crown Dependencies may hold variants of the British passport which confirm their Isle of Man, Jersey, or Guernsey identity. Many of the other categories of nationality do not grant bearers right of abode in the United Kingdom itself.

British National (Overseas) passports are issued to individuals connected to Hong Kong prior to the territory's transfer from Britain to China. British Overseas Citizen passports are primarily issued to individuals who did not acquire the citizenship of the colony they were connected to when it obtained independence (or their stateless descendants). British Overseas Citizen passports are also issued to certain categories of Malaysian nationals in Penang and Malacca, and individuals connected to Cyprus as a result of the legislation granting independence to those former British colonies. British Protected Person passports are issued to otherwise stateless people connected to a former British protectorate. British subject passports are issued to otherwise stateless individuals connected to British India or to certain categories of Irish citizens (though, in the latter case, they do convey right of abode).

Additionally, individuals connected to a British overseas territory are accorded British Overseas Territories citizenship and may hold passports issued by the governments of their respective territory. All overseas territory citizens are also now eligible for full British citizenship. Each territory maintains its own criteria for determining whom it grants right of abode. Consequently, individuals holding BOTC passports are not necessarily entitled to enter or reside in the territory that issued their passport. Most countries distinguish between BOTC and other classes of British nationality for border control purposes. For instance, only Bermudian passport holders with an endorsement stating that they possess right of abode or belonger status in Bermuda are entitled to enter America without an electronic travel authorisation.[36]

Border control policies in many jurisdictions distinguish between holders of passports with and without right of abode, including NWOHRs and holders of the various British passports that do not confer right of abode upon the bearer. Certain jurisdictions may additionally distinguish between holders of such British passports with and without indefinite leave to remain in the United Kingdom. NWOHRs do not, for instance, have access to the Visa Waiver Program, or to visa free access to the Schengen Area or Japan. Other countries, such as India which allows all Chinese nationals to apply for eVisas, do not make such a distinction. Notably, while Singapore does permit visa free entry to all categories of British passport holders, it reduces length of stay for British nationals without right of abode in the United Kingdom, but does not distinguish between ROC passport holders with and without household registration.

Until 31 January 2021, holders of British National (Overseas) passports were able to use their UK passports for immigration clearance in Hong Kong[37] and to seek consular protection from overseas Chinese diplomatic missions. This was a unique arrangement as it involved a passport issued by one state conferring right of abode (or, more precisely right to land) in and consular protection from another state. Since that date, the Chinese and Hong Kong governments have prohibited the use of BN(O) passports as travel documents or proof of identity and it; much like British Overseas Citizen, British Protected Person, or ROC NWOHR passports; is not associated with right of abode in any territory. BN(O)s who do not possess Chinese (or any other) nationality are required to use a Document of Identity for Visa Purposes for travel.[37] This restriction disproportionally affects ease of travel for permanent residents of Indian, Pakistani, and Nepali ethnicity,[38] who were not granted Chinese nationality in 1997. As an additional consequence, Hongkongers seeking early pre-retirement withdrawals from the Mandatory Provident Fund pension scheme may not use BN(O) passports for identity verification.[39]

Latvia and Estonia

[edit]Similarly, non-citizens in Latvia and in Estonia are individuals, primarily of Russian or Ukrainian ethnicity, who are not citizens of Latvia or Estonia, but who have settled during the Soviet occupation, and thus have the right to a special non-citizen passport issued by the government as well as some other specific rights. Approximately two thirds of them are ethnic Russians, followed by ethnic Belarusians, ethnic Ukrainians, ethnic Poles and ethnic Lithuanians.[40][41] According to the UN Special Rapporteur, the citizenship and naturalization laws in Latvia "are seen by the Russian community as discriminatory practices".[42] Per Russian visa policy, holders of the Estonian alien's passport or the Latvian non-citizen passport are entitled to visa free entry to Russia, in contrast to Estonian and Latvian citizens who must obtain an electronic visa.

Regional and subnational passports

[edit]China

[edit]The People's Republic of China (PRC) authorises its Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau to issue passports to their permanent residents with Chinese nationality under the "one country, two systems" arrangement. Visa policies imposed by foreign authorities on Hong Kong and Macau permanent residents holding such passports are different from those holding ordinary passports of the People's Republic of China. A Hong Kong Special Administrative Region passport (HKSAR passport) and Macau Special Administrative Region passport (MSAR passport) gain visa-free access to many more countries than ordinary PRC passports.[43]

On 1 July 2011, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China launched a trial issuance of e-passports for individuals conducting public affairs work overseas on behalf of the Chinese government.[44][45] The face, fingerprints, and other biometric features of the passport holder is digitized and stored in pre-installed contactless smart chip,[46][47] along with "the passport owner's name, sex and personal photo as well as the passport's term of validity and [the] digital certificate of the chip".[48] Ordinary biometric passports were introduced by the Ministry of Public Security on 15 May 2012.[49] As of January 2015, all new passports issued by China are biometric e-passports, and non-biometric passports are no longer issued.[48]

In 2012, over 38 million Chinese citizens held ordinary passports, comprising only 2.86 percent of the total population at the time.[50] In 2014, China issued 16 million passports, ranking first in the world, surpassing the United States (14 million) and India (10 million).[51] The number of ordinary passports in circulation rose to 120 million by October 2016, which was approximately 8.7 percent of the population.[52] As of April 2017 to date, China had issued over 100 million biometric ordinary passports.[53]

Kingdom of Denmark

[edit]The three constituent countries of the Danish Realm have a common nationality. Denmark proper is a member of the European Union, but Greenland and Faroe Islands are not. Danish citizens residing in Greenland or Faroe Islands can choose between holding a Danish EU passport and a Greenlandic or Faroese non-EU Danish passport.

As of 21 September 2022, Danish citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 188 countries and territories, thus ranking the Danish passport fifth in the world (tied with the passports of Austria, the Netherlands, and Sweden) according to the Henley Passport Index.[54] According to the World Tourism Organization 2016 report, the Danish passport is first in the world (tied with Finland, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Singapore, and the United Kingdom) in terms of travel freedom, with the mobility index of 160 (out of 215 with no visa weighted by 1, visa on arrival weighted by 0.7, eVisa by 0.5 and traditional visa weighted by 0).[55]

Serbian Coordination Directorate Passports in Kosovo

[edit]Under Serbian law, people born or otherwise legally settled in Kosovo[g] are considered Serbian nationals and as such they are entitled to a Serbian passport.[56] However, these passports are not issued directly by the Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs but by the Serbian Coordination Directorate for Kosovo and Metohija instead.[57] These particular passports do not allow the holder to enter the Schengen Area without a visa.[58][59]

As of August 2023, Serbian citizens had visa-free or visa on arrival access to 138 countries and territories, ranking the Serbian passport 38th overall in terms of travel freedom according to the Henley Passport Index.[60][61] The Serbian passport is one of the 5 passports with the most improved rating globally since 2006, in terms of the number of countries that its holders may visit without a visa.[62][63][64]

American Samoa

[edit]Although all U.S. citizens are also U.S. nationals, the reverse is not true. As specified in 8 U.S.C. § 1408, a person whose only connection to the United States is through birth in an outlying possession (which is defined in 8 U.S.C. § 1101 as American Samoa and Swains Island, the latter of which is administered as part of American Samoa), or through descent from a person so born, acquires U.S. nationality but not the citizenship. This was formerly the case in a few other current or former U.S. overseas possessions, i.e. the Panama Canal Zone and Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.[65] The passport issued to non-citizen nationals contains the endorsement code 9 which states: "THE BEARER IS A UNITED STATES NATIONAL AND NOT A UNITED STATES CITIZEN." on the annotations page.[66] Non-citizen nationals may reside and work in the United States without restrictions, and may apply for citizenship under the same rules as resident aliens. Like resident aliens, they are not presently allowed by any U.S. state to vote in federal or state elections.

Passports issued by entities without sovereign territory

[edit]Several entities without a sovereign territory issue documents described as passports, most notably Iroquois League,[67][68] the Aboriginal Provisional Government in Australia and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[69] Such documents are not necessarily accepted for entry into a country.

Details and specifications

[edit]

Criteria for issuance

[edit]Each country sets its own conditions for the issue of passports.[71] Under the law of most countries, passports are government property, and may be limited or revoked at any time, usually on specified grounds, and possibly subject to judicial review.[72] In many countries, surrender of one's passport is a condition of granting bail in lieu of imprisonment for a pending criminal trial due to the risk of the person leaving the country.[73] When passport holders apply for a new passport (commonly, due to expiration of the previous passport, insufficient validity for entry to some countries or lack of blank pages), they may be required to surrender the old passport for invalidation. In some circumstances an expired passport is not required to be surrendered or invalidated (for example, if it contains an unexpired visa).

Requirements for passport applicants vary significantly from country to country, with some states imposing stricter measures than others. For example, Pakistan requires applicants to be interviewed before a Pakistani passport will be granted.[74] When applying for a passport or a national ID card, all Pakistanis are required to sign an oath declaring Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to be an impostor prophet and all Ahmadis to be non-Muslims.[75] In contrast, individuals holding British National (Overseas) status are legally entitled to hold a passport in that capacity.

Countries with conscription or national service requirements may impose restrictions on passport applicants who have not yet completed their military obligations. For example, in Finland, male citizens aged 18–30 years must prove that they have completed, or are exempt from, their obligatory military service to be granted an unrestricted passport; otherwise a passport is issued valid only until the end of their 28th year, to ensure that they return to carry out military service.[76] Other countries with obligatory military service, such as South Korea and Syria, have similar requirements, e.g. South Korean passport and Syrian passport.[77]

Validity

[edit]Passports have a limited validity, usually between 5 and 10 years. Many countries require passports to be valid for a minimum of six months beyond the planned date of departure, as well as having at least two to four blank pages.[78] It is recommended that a passport be valid for at least six months from the departure date as many airlines deny boarding to passengers whose passport has a shorter expiry date, even if the destination country does not have such a requirement for incoming visitors.

There is an increasing trend for adult passports to be valid for ten years, such as a United Kingdom passport, United States Passport, New Zealand Passport (after 30 November 2015)[79] or Australian passport.

Some countries issue passports that are valid for longer than 10 years, which the ICAO does not recommend due to their security concerns. Some countries, including all member states of the European Union, do not accept passports older than 10 years.

Cover designs

[edit]

Passport booklets from almost all countries around the world display the national coat of arms of the issuing country on the front cover. The United Nations keeps a record of national coats of arms, but displaying a coat of arms is not an internationally recognised requirement for a passport.

There are several groups of countries that have, by mutual agreement, adopted common designs for their passports:

- The European Union. The design and layout of passports of the member states of the European Union are a result of consensus and recommendation, rather than of directive.[80] Passports are issued by member states and may consist of either the usual passport booklet or the newer passport card format. The covers of ordinary passport booklets are burgundy-red (except for Croatia which has a blue cover), with "European Union" written in the national language or languages. Below that are the name of the country, the national coat of arms, the word or words for "passport", and, at the bottom, the symbol for a biometric passport. The data page can be at the front or at the back of a passport booklet and there are significant design differences throughout to indicate which member state is the issuer. Member states that participate in the Schengen Agreement have agreed that their e-passports should contain fingerprint information in the chip.[81]

- In 2006, the members of the CA-4 Treaty (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua) adopted a common-design passport, called the Central American passport, following a design already in use by Nicaragua and El Salvador since the mid-1990s. It features a navy-blue cover with the words "América Central" and a map of Central America, and with the territory of the issuing country highlighted in gold (in place of the individual nations' coats of arms). At the bottom of the cover are the name of the issuing country and the passport type.

- The members of the Andean Community of Nations (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) began to issue commonly designed passports in 2005. Specifications for the common passport format were outlined in an Andean Council of Foreign Ministers meeting in 2002.[82] Previously issued national passports will be valid until their expiry dates. Andean passports are bordeaux (burgundy-red), with words in gold. Centred above the national seal of the issuing country is the name of the regional body in Spanish (Comunidad Andina). Below the seal is the official name of the member country. At the bottom of the cover is the Spanish word "pasaporte" along with the English "passport". Venezuela had issued Andean passports, but has subsequently left the Andean Community, so they will no longer issue Andean passports.

- The Union of South American Nations had signaled an intention to establish a common passport design, but it is doubtful that this will happen since the group effectively broke up in 2019.

- Twelve member states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) began issuing passports with a common design since early 2009.[83][84] It features the CARICOM symbol along with the national coat of arms and name of the member state, rendered in a CARICOM official language (English, French, Dutch). The member states which use the common design are Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. There was a movement by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to issue a common designed passport, but the implementation of the CARICOM passport made that redundant, and it was abandoned.[85]

Request page

[edit]

Passports sometimes contain a message, usually near the front, requesting that the passport's bearer be allowed to pass freely, and further requesting that, in the event of need, the bearer be granted assistance. The message is sometimes made in the name of the government or the head of state, and may be written in more than one language, depending on the language policies of the issuing authority.

Languages

[edit]In 1920, an international conference on passports and through tickets held by the League of Nations recommended that passports be issued in the French language, historically the language of diplomacy, and one other language.[86] Currently, the ICAO recommends that passports be issued in English, French, and Spanish; or in the national language of the issuing country and in either English, French, or Spanish.[87] Many European countries use their national language, along with English and French.

Some additional language combinations are:

- National passports of the European Union bear all of the official languages of the European Union. Two or three languages are printed at the relevant points, followed by reference numbers which point to the passport page where translations into the remaining languages appear.[citation needed]

- Algerian, Chadian, Lebanese, Mauritanian, Moroccan and Tunisian passports are in three languages: Arabic, English, and French.

- The Barbadian passport and the United States passport are tri-lingual: English, French and Spanish. United States passports were English and French since 1976, but began being printed with a Spanish message and labels during the late 1990s, in recognition of Puerto Rico's Spanish-speaking status. Since 2007, the Data Page, which contains photo, identifying information, and the passport's issuance and expiration dates, and the Personal Data and Emergency Contact page are written in English, French, and Spanish;[88] the cover and instructions pages are printed solely in English.

- On Belgian passports, all three official languages (Dutch, French, German) appear on the cover, in addition to English on the main page. The order of the official languages depends on the official residence of the holder.

- Passports of Bosnia and Herzegovina are in the three official languages of Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian in addition to English.

- Brazilian passports contain four languages: Portuguese, the official country language; Spanish, because of bordering nations; English and French.

- British passports bear English and French on the information page and Spanish, Welsh, Irish and Scottish Gaelic translations on an extra page.

- Cypriot passports are in Greek, Turkish and English.

- Haitian passports are in French and Haitian Creole.

- Passports issued by the Holy See are in Latin (the language of the Catholic Church), French, and English.[88]

- The first page of the old Libyan passport (green cover) was in Arabic only. The current passport has dark-blue cover, is electronically readable, and has Arabic with English translation in the first page (first page from a right-to-left script viewpoint). Similar arrangements are found in the passports of some other Arab countries.

- Iraqi passports are in Arabic, Kurdish and English.

- Macau SAR passports are in three languages: Chinese (in traditional Chinese characters), Portuguese and English.

- New Zealand passports are in English and te reo Māori.

- Norwegian passports are in the two forms of the Norwegian language, Bokmål and Nynorsk, Northern Sami and English.

- Sri Lankan passports are in Sinhala, Tamil and English.

- Swiss passports are in five languages: German, French, Italian, Romansh and English.

Limitations on use

[edit]

A passport is merely an identity document that is widely recognised for international travel purposes, and the possession of a passport does not in itself entitle a traveller to enter any country other than the country that issued it, and sometimes not even then, as with holders of the British Overseas citizen passport. Many countries normally require visitors to obtain a visa. Each country has different requirements or conditions for the grant of visas, such as for the visitor not being likely to become a public charge for financial, health, family, or other reasons, and the holder not having been convicted of a crime or considered likely to commit one.[89][90] Where a country does not recognise another, or is in dispute with it, entry may be prohibited to holders of passports of the other party to the dispute, and sometimes to others who have, for example, visited the other country; examples are listed below. A country that issues a passport may also restrict its validity or use in specified circumstances, such as use for travel to certain countries for political, security, or health reasons.

Many nations implement border controls restricting the entry of people of certain nationalities or who have visited certain countries. For instance, Georgia refuses entry to holders of passports issued by the Republic of China.[91] Similarly, since April 2017, nationals of Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sudan, Syria, Yemen, and Iran have been banned from entering the parts of eastern Libya under the control of the Tobruk government.[91][92][93] The Pakistani passports explicitly mention that these passports are valid in all countries except Israel. The majority of Arab countries, as well as Iran and Malaysia, ban Israeli citizens;[91] however, exceptional entry to Malaysia is possible with approval from the Ministry of Home Affairs.[94] Certain countries may also restrict entry to those with Israeli stamps or visas in their passports. As a result of tension over the former Republic of Artsakh dispute, Azerbaijan currently forbids entry to Armenian citizens as well as to individuals with proof of travel to Artsakh.

Between September 2017 and January 2021, the United States of America did not issue new visas to nationals of Iran, North Korea, Libya, Somalia, Syria, or Yemen pursuant to restrictions imposed by the Trump administration,[95] which were subsequently repealed by the Biden administration on 20 January 2021.[96] Similarly, the United States of America does not issue new visa to nationals of Afghanistan, Burma, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen, as well as limiting the entry of nationals from Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan, and Venezuela.[97] The restrictions were/are conditional and could be lifted if the countries affected met the required security standards specified by the Trump administration. Dual citizens of these countries could/can still enter the United States of America if they presented a passport from a non-designated country.

Value

[edit]One method by which to rank the value of a passport is to calculate its mobility score (MS). The mobility score of a passport is the number of countries that allow the holder of that passport to enter for general tourism visa-free, visa-on-arrival, eTA, or eVisa issued within 3 days. As of 2023, the strongest passport in the world is the Singaporean passport.[98]

However, another way to determine passport mobility score is the number of countries it allows holders to live and work in. For example, by this measure, the Irish passport would be most powerful because it allows the holder to live in all European Union/European Economic Area countries, as well as Switzerland and the United Kingdom, as the Irish passport is the only European Union passport now that still allows its users the right to live/work in the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

Passport issuance volumes

[edit]| Nationality | Number of issuances in year |

Latest year |

Number of issuances per capita |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24,021,257 | 2023 | 73‰ | |

| 5,400,000 | 2022 | 80‰ | |

| 1,745,340 | 2019–2020 | 68‰ | |

| 1,080,000 | 2022 | 210‰ | |

| 71,827 | 2019 | 10‰ | |

| 4,008,870 | 2020 | 61‰ | |

| 5,100,000 | 2014–2015 | 134‰ | |

| 30,080,000 | 2018 | 21‰ | |

| 774,544 | 2015 | 141‰[108] | |

| 1,478,583 | 2013 | 154‰ |

See also

[edit]- Animal passport

- Identity document

- Identity theft

- ISO/IEC 7810 defines the standard size for passport booklets.

- List of passports

- Passport card (disambiguation)

- Passport stamp

- Pet passport

- Self-sovereign identity

- Travel document

Notes

[edit]- ^ The local governments of most inhabited British Overseas Territories issue passports to British Overseas Territories citizens resident holding belonger status in the territory concerned, while the Chinese Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau issue passports to Chinese citizens holding permanent residence in the region concerned. Additionally, the British territories of Gibraltar, Jersey, Guernsey, and the Isle of Man are permitted to issue passports identifying their bearers as full British citizens.

- ^ These were issued to defined groups for travel together to particular destinations, such as a group of school children on a school trip. As of 2021, collective passports are still issued by the United Kingdom for field-trips to certain countries within the Schengen Area.[27]

- ^ Family passports were typically issued to one passport holder, who may travel alone or with other family members included in the passport. A family member not listed as the passport holder could not use the passport for travel without the passport holder. These passports are essentially obsolete as most countries; including all the EU states, Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom; require each traveller to have their own passport.[28]

- ^ This may apply, for example, to people who travel a lot on business, and may need to have, say, a passport to travel on while another is awaiting a visa for another country. The UK for example may issue a second passport if the applicant can show a need and supporting documentation, such as a letter from an employer.

- ^ Service Passports are issued by the Department of State to "certain non-personal services contractors who travel abroad in support of and pursuant to a contract with the U.S. government", to demonstrate the passport holder is travelling "to conduct work in support of the U.S. government while simultaneously indicating that the traveler has a more attenuated relationship with the U.S. government that does not justify a diplomatic or official passport."[30][31][32]

- ^ a b The area under the definition consists of:

- ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008. Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognised as an independent state by 109 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 117 UN member states have recognised Kosovo at some point, of which eight later withdrew their recognition.

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of Passport". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- ^ "A History of the Passport". History. 2017-05-16. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ a b Cane, P & Conaghan, J, eds. (2008). The New Oxford Companion to Law. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199290543.

- ^ "The electronic passport in 2021 and beyond". Thales Group.

- ^ George William Lemon (1783). English etymology; or, A derivative dictionary of the English language. p. 397. said that passport may signify either a permission to pass through a portus or gate, but noted that an earlier work had contained information that a traveling warrant, a permission or license to pass through the whole dominions of any prince, was originally called a pass par tout.

- ^ James Donald (1867). Chamber's etymological dictionary of the English language. W. and R. Chambers. pp. 366.

passport, pass'pōrt, n. orig. permission to pass out of port or through the gates; a written warrant granting permission to travel.

- ^ Lopez, Robert Sebationo; W. Raymond, Irving (2001). Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents. Columbia University Press. pp. 36–39. ISBN 9780231123563.

- ^ a b c Torpey, John (2018). The Invention of the Passport.

- ^

- Nehemiah 2:7–9

- Coskun, Cumhur (28 December 2017). "Cultural Identity and Passport Designs". New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. 4 (11): 139–146. doi:10.18844/prosoc.v4i11.2868. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Davis, John M. (July 1998). "Passport Fraud: Protecting U.S. Passport Integrity". FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Vol. 67, no. 7. pp. 9–13. NCJ 175115. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Meyer, Karl E. (2009). "The Curious Life of the Lowly Passport". World Policy Journal. 26 (1): 71–77. doi:10.1162/wopj.2009.26.1.71. JSTOR 40210108. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ Boesche, Roger (2003). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lexington Books. pp. 62 A superintendent must issue sealed passes before one could enter or leave the countryside(A.2.34.2, 181) a practice that might constitute the first passbooks and passports in world history. ISBN 9780739106075.

- ^ a b Nylan, Michael; Loewe, Michael, eds. (2010). China's early empires: a re-appraisal. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 297, 317–318. ISBN 9780521852975. LCCN 2011378715. OCLC 428776512. OL 24864515M.

- ^ Frank, Daniel (1995). The Jews of Medieval Islam: Community, Society, and Identity. Brill Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 90-04-10404-6.

- ^ a b A brief history of the passport Archived 2019-10-09 at the Wayback Machine – The Guardian

- ^ Casciani, Dominic (2008-09-25). "Analysis: The first ID cards". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- ^ John Torpey, Le contrôle des passeports et la liberté de circulation. Le cas de l'Allemagne au XIXe siècle, Genèses, 1998, n° 1, pp. 53–76

- ^ a b Bixby, Patrick (2023). License to Travel: A Cultural History of the Passport. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-39789-7.

- ^ "History of Passports". Government of Canada. 10 April 2014. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ Marrus, Michael Robert (1985). The unwanted : European refugees in the twentieth century. Mazal Holocaust Collection. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-19-503615-8. OCLC 12344863.

- ^ "League of Nations Photo Archive – Timeline – 1920". Indiana University. Archived from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ "League of Nations 'International' or 'Standard' passport design". Illustrated album of the League of Nations. Geneva: League of Nations Secretariat, Information Section. 1926. p. 63. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- ^ "International Conferences – League of Nations Archives". Center for the Study of Global Change. 2002. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Giaimo, Cara (2017-02-07). "The Little-Known Passport That Protected 450,000 Refugees". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2022-01-30.

- ^ "Welcome to the ICAO Machine Readable Travel Documents Programme". ICAO. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ^ Machine Readable Travel Documents, Doc 9303 (Sixth ed.). ICAO. 2006. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- ^ Arkelian, A.J. "The Right to a Passport in Canadian Law." The Canadian Yearbook of International Law, Volume XXI, 1983. Republished in November 2012 in Artsforum Magazine at http://artsforum.ca/ideas/in-depth Archived 2013-12-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Arkelian, A.J. "Freedom of Movement of Persons Between States and Entitlement to Passports". Saskatchewan Law Review, Volume 49, No. 1, 1984–85.

- ^ "Collective (group) passports". GOV.UK. Government Digital Service. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ "Passports for children". Canada.CA. Government of Canada. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ "Guidance ECB08: What are acceptable travel documents for entry clearance". Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Passports: Service Passports". 30 September 2016.

- ^ "Introduction to Passport Services". Archived from the original on 2018-08-02. Retrieved 2021-11-13.

- ^ "US Diplomatic Note" (PDF).

- ^ Selya 2004, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Cheng 2014, p. 138.

- ^ Chen, Yuren 陳郁仁; Tang, Zhenyu 唐鎮宇 (August 16, 2011). "無戶籍國民 返台將免簽" [Nationals without household registration returning to Taiwan will soon be visa-exempt]. Apple Daily (in Chinese). Archived from the original on February 4, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2019.

- ^ "Visa Exemptions for Bermudians Archived 2016-12-01 at the Wayback Machine". U.S. Consulate General in Bermuda. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- ^ a b "HKSAR Government follows up on China's countermeasures against British Government's handling of issues related to British National (Overseas) passport" (Press release). Government of Hong Kong. 29 January 2021. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Tsang, Emily; Paul, Ethan (2 February 2021). "Hong Kong BN(O): official rejection of passports leaves many members of ethnic minority communities stranded at home". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "MPFA statement" (Press release). Mandatory Provident Fund. 10 March 2021. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Population of Latvia by ethnicity and nationality; Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs Archived 31 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine 2015 (in Latvian)

- ^ "Section 1 and Section 8, Law "On the Status of those Former U.S.S.R. Citizens who do not have the Citizenship of Latvia or that of any Other State"". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ Report on mission to Latvia (2008) Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, UN Special Rapporteur on contemporary forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance — see Para. 30 and 88

- ^ "Visa-Free Access for PRC, HKSAR and MSAR Passports". aipassportphoto.com.

- ^ 中华人民共和国外交部公告 (in Chinese). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "China: Procedure and requirements to obtain a biometric passport,..." Canada. Immigration and Refugee Board. 6 May 2013. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 12 December 2019 – via UNHCR.

- ^ "Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi Attends the Launch Ceremony for the Trial Issuance of E-Passports for Public Affairs". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 5 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "因公电子护照31日试点签发 可使持照人快速通关". 中国网. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ a b "Responses to Information Requests: CHN105049.E China: Information on electronic/biometric passports,..." (PDF). Canada. Immigration and Refugee Board. 22 September 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ "Chinese passports to get chipped". China Daily USA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "3800万中国公民持有普通护照 电子护照正式签发启用". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "India ranks third in issuing passports". Times of India. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- ^ "国务院关于出境入境管理法执行情况的报告". Archived from the original on 2016-11-06. Retrieved 2016-11-05.

- ^ "4月全国启用新号段电子普通护照 你拿到新护照了吗 - 爱旅行网". www.ailvxing.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ "Henley Passport Index 2020 Q1 Infographic Global Ranking" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Visa Openness Report 2016" (PDF). World Tourism Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ^ "Najnovije vesti". Glas javnosti. 7 November 2008.

- ^ "Kako do biometrijskih dokumenata ako sam stanovnik Kosova i Metohije?". Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2021-11-13.

- ^ "Consolidated version of Council regulation No. 539/2001, as of 19 December 2009". Archived from the original on 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Putna isprava – Pasoš" (in Serbian). Ministry of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ^ "The Official Passport Index Ranking".

- ^ "Law on Travel Documents" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ "The Henley & Partners Visa Restrictions Index Celebrates Ten Years" (Press release). Henley & Partners – via www.prnewswire.com.

- ^ "Izdavanje pasoša u diplomatsko-konzularnim predstavništvima Srbije". Archived from the original on 24 September 2009.

- ^ "Izgled biometrijskog pasoša" (in Serbian). Ministry of Internal Affairs. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ^ In the Panama Canal Zone only those persons born there prior to January 1, 2000 with at least one parent as an American citizen were recognised as citizens and were both nationals and citizens. Also in the former Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands the residents were considered nationals and citizens of the Trust Territory and not American nationals.

- ^ "8 FAM 505.2 Passport Endorsements". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ^ "Question 1". Dear Uncle Ezra... Cornell University. 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ Wallace, William N. (1990-06-12). "Putting Tradition to the Test". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "The New e-Passport". Osterreichs Bundesheer (in German and English). Eigentümer und Herausgeber: Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung und Sport. February 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ^ "How Your Passport is Made – Exclusive Behind-The-Scenes Footage". National Archives. July 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014.

- ^ Hannum, Hurst (1987). The Right to Leave and Return in International Law and Practice. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 9789024734450. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ "What Is a Passport Seizure?". 26 August 2016.

- ^ Devine, F. E (1991). Commercial bail bonding: a comparison of common law alternatives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 84, 91, 116, 178. ISBN 978-0-275-93732-4.

- ^ "Government of Pakistan, Directorate General of Immigration & Passports". Dgip.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ^ Hanif, Mohammed (16 June 2010). "Why Pakistan's Ahmadi community is officially detested". BBC News.

- ^ "Passports for persons liable for military service". Finnish Police. 2009. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "Passports for Syrian Citizens". Archived from the original on 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2013-01-11.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". US Department of State. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "10-year passport law passes". The New Zealand Herald. December 4, 2023.

- ^ Resolutions of 23 June 1981, 30 June 1982, 14 July 1986 and 10 July 1995 concerning the introduction of a passport of uniform pattern, OJEC, 19 September 1981, C 241, p. 1; 16 July 1982, C 179, p. 1; 14 July 1986, C 185, p. 1; 4 August 1995, C 200, p. 1.

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 2252/2004 of 13 December 2004 on standards for security features and biometrics in passports and travel documents issued by Member States". Official Journal of the European Union. 29 December 2004. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ Andean Community / Decision 525: Minimum specific technical characteristics of Andean Passport Archived 2016-09-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "More Member States using the new CARICOM passport". Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ "Lesser Known Facts about the CSM". Archived from the original on October 19, 2010.

- ^ "Benefits of CARICOM passport". Best Citizenships. 8 February 2021. Retrieved 2023-03-08.

- ^ Baenninger, Martin (2009). In the eye of the wind: a travel memoir of prewar Japan. Footprints. Vol. Footprints. Cheltenham, England: McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7735-3497-1. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Doc 9303, Machine Readable Travel Documents Part 3 - Specifications Common to all MRTDs (PDF) (8th ed.). Montréal, Quebec, Canada: International Civil Aviation Organization. 2021. p. 3. ISBN 9789292659349. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2025-02-07. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- ^ a b "PRADO". European Council. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

- ^ "ilink – USCIS". uscis.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-03-08. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- ^ Bourke, Latika (September 27, 2015). "Chris Brown won't be able to come to Australia unless he challenges visa refusal and wins". The Age.

- ^ a b c "Country information (passport section)". Timatic. International Air Transport Association (IATA) through Olympic Air. Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Cusack, Robert (11 April 2017). "Khalifa Haftar introduces a 'Muslim ban' in east Libya". Alaraby.co.uk.

- ^ "Haftar issues travel ban on six Muslim countries in eastern Libya". Libyanexpress.com. Libyan Express. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ^ "Visa requirements by country". Immigration Department of Malaysia. Archived from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Shear, Michael D. (24 September 2017). "New Order Indefinitely Bars Almost All Travel from Seven Countries". The New York Times.

- ^ "Proclamation on Ending Discriminatory Bans on Entry to The United States". The White House. 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2021-01-24.

- ^ https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/06/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-restricts-the-entry-of-foreign-nationals-to-protect-the-united-states-from-foreign-terrorists-and-other-national-security-and-public-safety-threats

- ^ "The world's most powerful passports for 2023". 18 July 2023.

- ^ "Reports and Statistics (state.gov)".

- ^ "Nos résultats".

- ^ "2019-20 Passport Facts". 2 March 2018.

- ^ Department of Foreign Affairs (29 December 2022). "2022 sets new record for Irish passports". gov.ie. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ No. of HKSAR passport issued (format: spreadsheet) Archived 2022-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "HM Passport Office data: February 2021".

- ^ "Rapport annuel du Programme de passeport pour 2014–2015". 19 October 2016.

- ^ "2018年,中国护照签发量首次突破3000万". 25 September 2019.

- ^ "Poliisi: Yli 800000 tarvitsee uuden passin tänä vuonna – tiedossa on ruuhkaa". 20 January 2016.

- ^ "Suomen virallinen väkiluku oli vuoden 2015 lopussa 5 487 308". 1 April 2016.

- ^ "Rekordmånga nya pass förra året". 27 February 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Advisory and technical committee for communications and transit. Replies of the governments to the enquiry on the application of the resolutions relating to passports, customs formalities and through tickets. Geneva: League of Nations. 1922. OCLC 46235968.

- Holder IV, Floyd William (Fall 2009). An Empirical Analysis of the State's Monopolization of the Legitimate Means of Movement: Evaluating the Effects of Required Passport use on International Travel (M. P. A. thesis). San Marcos: Texas State University. OCLC 503473693. Docket Applied Research Projects, Paper 308.

- Lloyd, Martin (2008) [2003]. The Passport: The History of Man's Most Travelled Document (2nd ed.). Canterbury: Queen Anne's Fan. ISBN 978-0-9547150-3-8. OCLC 220013999.

- Salter, Mark B. (2003). Rights of Passage: The Passport in International Relations. Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58826-145-8. OCLC 51518371.

- Torpey, John C. (2000). The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge studies in law and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63249-8. OCLC 59408523.

- United States; Hunt, Gaillard (1898). The American Passport; Its History and a Digest of Laws, Rulings and Regulations Governing Its Issuance by the Department of State. Washington: Govt. print. off. OCLC 3836079.

- Bixby, Patrick (2023). License to Travel: A Cultural History of the Passport. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-39789-7.

External links

[edit] Media related to Passports at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Passports at Wikimedia Commons- PRADO – The Council of the European Union Public Register of Authentic Travel- and ID Documents Online

- How Passports Work US-focused information from Howstuffworks

- Investigation into passport fraud, Dateline NBC, December 28, 2007

- Passport-free travel to begin for citizens of nine more European countries, Seattle Times, November 8, 2007

Passport

View on GrokipediaHistory

Etymology and Origin

The term "passport" entered English around 1500 from Middle French passeport, a compound of passer ("to pass") and port ("harbor" or "gate"), denoting permission to pass through a port or controlled entry point.[10] This etymology reflects the document's original function in authorizing transit across maritime or land borders, often during periods of restricted movement such as plagues or conflicts.[11] Equivalent terms in other languages, like Dutch paspoort, trace similarly to French influences, emphasizing the passage through gates or ports rather than identity verification.[12] Precursors to passports existed in ancient civilizations as safe-conduct letters or exit permits regulating travel. An Arabic papyrus from Hermopolis Magna, Egypt, dated January 24, 722 CE, records an exit permit, evidencing early state control over departure.[13] Biblical accounts describe similar authorizations, such as Persian King Artaxerxes I granting Nehemiah letters of safe passage in 445 BCE to travel to Jerusalem and inspect its walls.[14] These early forms focused on royal or official permission for safe transit rather than personal identification, evolving from ad hoc protections into more systematic documents by the medieval period. The modern passport's origin as a standardized travel and identity document emerged in 15th-century Europe amid rising state sovereignty and border controls. In England, King Henry V enacted the Safe Conducts Act of 1414, requiring letters for foreign travel to ensure return and prevent desertion during wars.[15] By the late 15th century, French and Italian city-states issued passeports or similar permits to regulate movement through gates, particularly in response to vagrancy, espionage, and disease outbreaks like the Black Death.[9] This shift marked a transition from feudal safe conducts to state-issued credentials linking individuals to sovereign authority.Early Antecedents and Safe Conducts

One of the earliest documented travel permits is an Arabic papyrus from Hermopolis Magna, Egypt, dated January 24, 722 CE, serving as an exit permit that regulated departure and travel activities under early Islamic administration.[16] This artifact indicates state control over movement, predating European medieval practices, though such regulations were sporadic and tied to administrative needs rather than universal identity verification. In medieval Europe, safe conducts—also known as letters of protection or sauf-conduits—emerged as formal assurances of safe passage issued by monarchs, feudal lords, and city-states to merchants, pilgrims, diplomats, and other travelers.[13] These documents guaranteed protection from arrest, violence, or property seizure within the issuer's domain, facilitating trade and pilgrimage amid fragmented polities and frequent conflicts.[17] Unlike modern passports, safe conducts did not establish nationality or personal identity but were jurisdiction-specific, often requiring renewal at borders or upon entering new territories.[17] By the 12th century in England, safe conducts proliferated due to expanding mercantile activity, with records showing issuance to foreigners for domestic travel and to English subjects abroad.[17] The Safe Conducts Act of 1414 under King Henry V codified this practice, empowering the crown to grant protections primarily to foreign merchants and pilgrims, marking a step toward standardized travel authorization.[18] In France, similar documents appeared earlier; during Louis XI's reign (1461–1483), passports ensured safe transit for nobility and prominent figures across Europe.[19] The term "passport" itself derives from medieval Italian "passa porto," denoting permission to pass ports or gates, reflecting origins in maritime and urban access controls.[20] Examples include a 1425 safe conduct for Roma pilgrims in Iberia en route to Santiago de Compostela, highlighting use for marginalized groups seeking devotional travel.[21] In Spain, such letters protected Christian pilgrims under Catholic Monarchs' authority, underscoring their role in religious mobility.[22] By the 16th century, safe conducts became more uniform across Europe, evolving into precursors of state-issued identity documents amid rising centralized authority.[23]Emergence of Modern Passports

![Italian passport, issued in 1872][float-right] The emergence of modern passports in the 19th century coincided with the rise of nation-states, industrialization, and expanded cross-border mobility via railways, which necessitated systematic identification and control of travelers beyond ad hoc feudal permissions.[20] Prior to this period, travel documents were sporadically issued for specific purposes, often as letters of safe conduct between rulers, lacking the standardized linkage to national citizenship that characterized emerging forms.[9] By the mid-19th century, European states began formalizing passport issuance to manage growing populations and migration flows driven by economic opportunities and technological advancements.[24] In 1850, German states introduced standardized passport formats containing consistent personal details to facilitate rail travel and border verification, reflecting a shift toward bureaucratic uniformity amid unification efforts.[20] France, having experimented with internal passports during the Revolution for population surveillance, relaxed international requirements in 1861 due to the impracticality of enforcing them against surging emigration, a policy trend echoed across much of Europe where passports remained optional for most travelers until the early 20th century.[24] In the United States, passports had been issued since the 1780s by consular officials abroad, primarily as voluntary aids for diplomatic protection rather than mandatory entry controls, with formats featuring physical descriptions but no photographs.[25] These documents typically consisted of thin paper booklets or single sheets detailing the bearer's name, age, occupation, and physical traits, signed by state officials to affirm permission to depart and seek readmission.[26] Unlike earlier safe conducts, which emphasized interpersonal or royal guarantees, 19th-century passports increasingly embodied state sovereignty over citizens' mobility, serving dual roles in emigration oversight and rudimentary immigration screening, though enforcement varied and widespread passport-free travel persisted in regions like Europe and North America.[9] This evolution laid the groundwork for stricter controls, as governments grappled with the challenges of verifying identity without modern biometrics, often relying on written attestations prone to forgery.[24]Post-World War Developments and Standardization

Following World War II, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), formed under the 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation, assumed responsibility for harmonizing travel documents to support burgeoning international air travel and border security. ICAO's Facilitation Division initiated systematic reviews of passports and visas in the late 1940s, emphasizing uniform formats to reduce forgery risks and streamline inspections amid rising refugee movements and decolonization. By the 1960s, with air passenger traffic surging—ICAO recorded over 100 million annual passengers by 1960—the need for technological upgrades prompted the creation of a Panel on Passport Cards in 1968, tasked with developing machine-readable standards for enhanced verification of citizenship and identity.[27] In 1980, ICAO formalized the machine-readable passport (MRP) standard through Document 9303, mandating optical character recognition (OCR) zones on the data page for automated reading, which improved processing efficiency at borders and airports. This addressed inconsistencies in pre-war documents, where varied layouts hindered interoperability; for instance, early post-war passports often lacked standardized fields, leading to delays documented in ICAO facilitation reports. Member states progressively adopted MRPs, with full compliance required by April 1, 2010, after which non-MRPs were phased out globally to mitigate fraud, as evidenced by reduced document rejection rates in ICAO-monitored trials.[28][29] The early 2000s saw further evolution with biometric integration, driven by security imperatives post-9/11 and advances in digital verification. In 2003, ICAO endorsed electronic MRTDs (eMRTDs), incorporating contactless RFID chips storing facial biometrics as the primary identifier, alongside optional fingerprints or iris scans, per updated Doc 9303 specifications. This standard, ratified by over 190 member states, embedded public key infrastructure for chip authentication, verifying document integrity against counterfeiting—a vulnerability in paper-based MRPs, where forgery rates exceeded 10% in some regions per Interpol data shared with ICAO. By 2006, initial ePassport issuances began in countries like Malaysia and the EU, with global adoption accelerating; as of 2023, over 150 nations issued biometric passports, correlating with a 40% drop in identity fraud at e-gates according to ICAO analytics.[27][30] Ongoing refinements include 2024 updates to Doc 9303 for flexible biometric data encoding, allowing transitions to advanced formats like JPEG 2000 while maintaining backward compatibility until 2030, ensuring interoperability amid evolving threats such as deepfakes. These developments reflect causal priorities: empirical security gains from verifiable biometrics outweighed implementation costs, as validated by ICAO's cross-state validations showing error rates below 0.1% in facial matching. Standardization has thus shifted passports from discretionary safe-conducts to rigorously encoded proofs of nationality, underpinning causal chains in global migration control and aviation facilitation.[31]Types and Categories

Ordinary and Full Validity Passports

Ordinary passports, also referred to as regular or tourist passports, are the standard travel documents issued by national governments to civilian citizens for purposes of international travel, verifying the holder's identity, nationality, and right to return to the issuing country. These passports are distinct from diplomatic, official, or service variants, as they are provided to individuals not engaged in government duties, and they facilitate general tourism, business, or personal travel subject to destination countries' entry regulations. Under ICAO standards outlined in Doc 9303, ordinary passports are designated with the document code "PP" in machine-readable zones, ensuring interoperability for border controls worldwide.[32][33][34][35] Full-validity ordinary passports are issued for the maximum standard duration permitted by the issuing authority, typically ranging from 5 to 10 years for adults, in contrast to limited-validity documents provided for emergencies or provisional needs, which may expire within 1 year or less. This full term supports extended international mobility without frequent renewals, though actual usability depends on remaining validity requirements imposed by receiving nations, such as the common 6-month rule for visa-free entry. For instance, in Pakistan, ordinary passports are granted to all eligible citizens upon fulfilling procedural requirements, without specified validity distinctions in issuance but aligned with national norms.[36][37][38][33] Validity periods for full-validity ordinary passports vary by country and applicant age. In the United States, they are valid for 10 years for persons 16 and older, and 5 years for children under 16.[39] Canada's regular passports offer 10 years for adults aged 16 or over and 5 years for minors.[40] Tanzania issues ordinary passports to citizens without age-based validity caps specified in general issuance, though aligned with regional standards. These durations reflect national policies balancing security, administrative efficiency, and holder convenience, with ICAO recommending but not mandating uniform terms to accommodate diverse sovereign practices.[34][32]Special Purpose Passports

Special purpose passports are travel documents issued by governments or international organizations for targeted uses, such as diplomatic representation, official non-diplomatic duties, urgent repatriation, religious pilgrimages, or employment with supranational bodies, differing from ordinary passports in privileges, validity, and eligibility. These passports typically confer specific immunities or facilitations aligned with the holder's role, but their recognition varies by receiving state under bilateral agreements or conventions.[41] Diplomatic passports are allocated to personnel with diplomatic rank, including ambassadors, consuls, and foreign service officers on representational missions, enabling visa exemptions or expedited entry in many jurisdictions per the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961. In the United States, these black-covered documents are issued by the Department of State to individuals with comparable status and remain valid for no more than five years, strictly for official travel. Holders must often carry a regular passport for personal trips to avoid misuse implications.[35][42] Official and service passports target government employees undertaking administrative, technical, or military duties without diplomatic immunity, such as civil servants or contractors on state business. These documents, exemplified by U.S. official passports for Department of Defense personnel, provide limited fee waivers or endorsements but generally require visas akin to regular passports. Pakistan distinguishes official passports for public servants on duty from diplomatic ones reserved for higher envoys. Validity mirrors diplomatic types at up to five years, with issuance tied to verified employment and purpose.[41][33][43] Emergency passports or limited-validity travel documents address acute needs, like lost credentials abroad or life-or-death urgency, permitting one-way return or essential transit. U.S. authorities issue these through embassies with short-term validity, requiring replacement upon arrival home, while Pakistan offers emergency travel documents for citizens stranded without papers. Such instruments prioritize repatriation over broad travel, often lacking biometric features of standard passports.[44][33] Pilgrimage-specific passports facilitate religious travel, notably for Hajj, where select nations like Indonesia produce dedicated booklets restricting use to Saudi Arabia entry for the annual Mecca pilgrimage. These documents align with Saudi visa quotas and health protocols, ensuring pilgrims' return post-ritual, though many countries now embed Hajj permits in ordinary passports.[45] The United Nations laissez-passer serves UN officials and affiliated agency staff for mission-related journeys, recognized by member states under the 1946 Convention on Privileges and Immunities as a valid travel instrument alongside national passports. Issued in blue for standard staff and occasionally red for senior roles, it supports official duties without conferring nationality-based rights, with over 40,000 in circulation as of recent estimates. Complementary to personal passports, it underscores the bearer's functional immunity during endorsed travel.[46][47]Passports for Refugees, Stateless Persons, and Limited Rights