Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Saka language

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2025) |

| Saka | |

|---|---|

| Khotanese, Tumshuqese | |

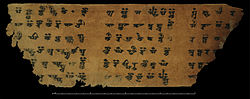

Khotanese animal zodiac BLI6 OR11252 1R2 1 | |

| Native to | Kingdom of Khotan, Tumshuq, Murtuq, Shule Kingdom,[1] and Indo-Scythian Kingdom |

| Region | Tarim Basin (Xinjiang, China) |

| Ethnicity | Saka |

| Era | 100 BC – 1,000 AD developed into Wakhi[2] |

| Dialects |

|

| Brahmi, Kharosthi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | kho |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:kho – Khotanesextq – Tumshuqese |

kho (Khotanese) | |

xtq (Tumshuqese) | |

| Glottolog | saka1298 |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Saka, or Sakan, was a variety of Eastern Iranian languages, attested from the ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Khotan, Kashgar and Tumshuq in the Tarim Basin, in what is now southern Xinjiang, China. It is a Middle Iranian language.[3] The two kingdoms differed in dialect, their speech known as Khotanese and Tumshuqese.

The Saka rulers of the western regions of the Indian subcontinent, such as the Indo-Scythians and Western Satraps, are traditionally assumed to have spoken practically the same language.[4] This has however been questioned by more recent research.[5]

Documents on wood and paper were written in modified Brahmi script with the addition of extra characters over time and unusual conjuncts such as ys for z.[6] The documents date from the fourth to the eleventh century. Tumshuqese was more archaic than Khotanese,[7] but it is much less understood because it appears in fewer manuscripts compared to Khotanese. The Khotanese dialect is believed to share features with the modern Wakhi and Pashto.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Saka was known as "Hvatanai" (from which the name Khotan) in contemporary documents.[15] Many Prakrit terms were borrowed from Khotanese into the Tocharian languages.

Classification

[edit]Khotanese and Tumshuqese are closely related Eastern Iranian languages.[16]

The unusual phonological development of Proto-Iranian *ćw to Khotanese śś sets the latter apart from most other Iranian languages (which usually have sp or a product thereof). Similarities with Sogdian exist but could be due to parallel developments or areal features.[17]

History

[edit]The two known dialects of Saka are associated with a movement of the Scythians. No invasion of the region is recorded in Chinese records and one theory is that two tribes of the Saka, speaking the two dialects, settled in the region in about 200 BC before the Chinese accounts commence.[18]

Michaël Peyrot (2018) rejects a direct connection with the "Saka" (塞) of the Chinese Hanshu, who are recorded as having immigrated in the 2nd century BC to areas further west in Xinjiang, and instead connects Khotanese and Tumshuqese to the long-established Aqtala culture (also Aketala, in pinyin) which developed since ca. 1000 BC in the region.[19]

The Khotanese dialect is attested in texts between the 7th and 10th centuries, though some fragments are dated to the 5th and 6th centuries. The far more limited material in the Tumshuqese dialect cannot be dated with precision, but most of it is thought to date to the late 7th or the 8th century.[20][21]

The Saka language became extinct after invading Turkic Muslims conquered the Kingdom of Khotan in the Islamicisation and Turkicisation of Xinjiang.

In the 11th century, it was remarked by Mahmud al-Kashgari that the people of Khotan still had their own language and script and did not know Turkic well.[22][23] According to Kashgari some non-Turkic languages like the Kanchaki and Sogdian were still used in some areas.[24] It is believed that the Saka language group was what Kanchaki belonged to.[25] It is believed that the Tarim Basin became linguistically Turkified by the end of the 11th century.[26]

Old Khotanese phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Retroflex | Palatal/ | Velar | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | Voiceless | Unaspirated | p /p/ | tt, t /t/ | ṭ /ʈ/ | k /k/ | (t, g [ʔ])[a] | |

| Aspirated | ph /pʰ/ | th /tʰ/ | ṭh /ʈʰ/ | kh /kʰ/ | ||||

| Voiced | b /b/ | d /d/ | ḍ /ɖ/ | gg /ɡ/ | ||||

| Affricate | Voiceless | Unaspirated | tc /ts/ | kṣ /ʈʂ/ | c, ky /tʃ/ | |||

| Aspirated | ts /tsʰ/ | ch /tʃʰ/ | ||||||

| Voiced | js /dz/ | j, gy /dʒ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | Non-Sibilant | t /ð/ (later > ʔ) | g /ɣ/ (later > ʔ) | |||||

| Sibilant | Voiceless | s /s/ | ṣṣ, ṣ /ʂ/ | śś, ś /ʃ/ | h /h/ | |||

| Voiced | ys /z/ | ṣ /ʐ/ | ś /ʒ/ | |||||

| Nasal | m /m/ | n, ṃ, ṅ /n/ | ṇ /ɳ/ | ñ /ɲ/ | ||||

| Approximant | Central | v /w/ hv /wʰ/, /hʷ/ |

rr, r /ɹ/ | r /ɻ/ | y /j/ | |||

| Lateral | l /l/ | |||||||

Vowels

[edit]| Khotanese Transliteration[30] |

IPA Phonemic | IPA Phonetic |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/ | [a] |

| ā | /a:/ | [a:] |

| i | /i/ | [i] |

| ī | /i:/ | [i:] |

| u | /u/ | [u] |

| ū | /u:/ | [u:] |

| ä | /ə/ | [ə] |

| e | /e:/[b] | [æ~æ:][c] |

| o | /o:/[b] | [o~o:][c] |

| ai | /ai̯/ | |

| au | /au̯/ | |

| ei | /ae̯/ |

Sound changes

[edit]Khotanese was characterized by pervasive lenition, developments of retroflexes and voiceless aspirated consonants.[31]

- Changes shared in common Sakan

- *ć, *j́ → s, ys, but *ćw, *j́w → śś, ś

- *ft, *xt → *βd, *ɣd

- Lenition of *b, *d, and *g → *β, ð, ɣ when initially or after vowels or *r

- Nasals + voiceless consonants → nasals + voiced consonants (*mp, *nt, *nč, *nk → *mb, *nd, *nj, *ng)

- *ər (syllabic consonant) → *ur after labials *m, *p, *b, *β; then *ir or *ar elsewhere

- *rn, *rm → rr

- *sr → ṣ

- *č, *ǰ → tc, js

- Changes shared in East Sakan

- Nasals + voiced consonants → geminate nasals (*mb, *nd → *mm, *nn, but *ng remained)

- Questionable umlaut of *a into i and u before syllables with *i and *u, respectively (*masita → *misita → mista ~ mästa "big")

- Lenition of *p, *t, *č, and *k → b, d, ǰ, and g after vowels or *r

- *f, *x → *β, *ɣ before consonants

- *ɣ → *i̯ between vowels a, i and a consonant (*daxsa- → *daɣsa- → *daisa- → dīs- "to burn")

- *β → w; *ð, *ɣ → ∅ after vowels

- *rð → l

- *f, *θ, *x → *h after vowels

- *w, *j → *β, *ʝ initially

- *f, *θ, *x → *β, ð, ɣ initially before *r (θrayah → ðrayi → drai "three")

- Lengthening of stressed vowels before clusters *rC and *ST (sibilants + dentals) (*sarta → *sārta → sāḍa "cold", *astaka → āstaa "bone" but not *aštā́ → haṣṭā "eight").

- Compensatory lengthening of vowels, before clusters containing non-sibilant fricatives and *r (*puhri → pūrä "son", darɣa → dārä "long"), however, -ir- and -ur- from earlier *ər were unaffected (*mərɣa- → mura- "fowl").

- Reduction of internal unstressed short and long vowels (*hámānaka → *haman

aka → hamaṅgä) - *uw → u

- *β, ð, ʝ, ɣ > b, d, ɟ, g initially

- *f, *θ, *x → ph, th, kh (remaining instances)

- *rth → ṭh; *rt, *rd → ḍ

- Lenition of b, d, g (from earlier voiceless consonants) → β (→ w), ð, ɣ after vowels or *r

- ḍ also phonetically became ḷ or ṛ in this position.

- Palatalization of certain consonants:

| Earlier | Later |

|---|---|

| *ky | c, ky |

| *gy | j, gy |

| *khy | ch |

| *tcy | c |

| *jsy | j |

| *tsy | ch |

| *ny | ñ, ny |

| *sy | śś |

| *ysy | ś |

| *st, *ṣṭ | śt, śc |

Texts

[edit]

Other than an inscription from Issyk kurgan that has been tentatively identified as Khotanese (although written in Kharosthi), all of the surviving documents originate from Khotan or Tumshuq. Khotanese is attested from over 2,300 texts[32] preserved among the Dunhuang manuscripts, as opposed to just 15 texts[33] in Tumshuqese. These were deciphered by Harold Walter Bailey.[34] The earliest texts, from the fourth century, are mostly religious documents. There were several viharas in the Kingdom of Khotan and Buddhist translations are common at all periods of the documents. There are many reports to the royal court (called haṣḍa aurāsa) which are of historical importance, as well as private documents. An example of a document is Or.6400/2.3.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Mallory, J. P. (2010). "Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin" (PDF). Expedition. Vol. 52, no. 3. Penn Museum. pp. 44–53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ^ Parpola, Asko; Koskikallio, Petteri, eds. (2001). Early contacts between Uralic and Indo-European: linguistic and archaeological considerations: papers presented at an international symposium held at the Tvärminne Research Station of the University of Helsinki, 8-10 January, 1999. Suomalais-ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. ISBN 978-952-5150-59-9.

- ^ "Saka Language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Diringer, David (1953) [1948]. The Alphabet: A Key to the History of Mankind (Second and revised ed.). London: Hutchinson's Scientific and Technical Publications. p. 350.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

In sum, the evidence that the Saka language [of North India] is Khotanese or an earlier form of it is weak. Many of the features are found in other languages as well, and it is known from other sources that non-Khotanese Iranians found their way to northern India. In any case, the large number of Indic elements in Khotanese is no proof "daß das 'Nordarisch' sprechende Volk längere Zeit auf indischem Boden saß" (Lüders 1913), since there is ample evidence that instead speakers of Middle Indian migrated into the Tarim Basin.

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1970). "Saka Studies: The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". Iran. 8: 65–72. doi:10.2307/4299633. JSTOR 4299633.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Paris: UNESCO. 1992. p. 283. ISBN 92-3-103211-9.

- ^ Frye, R.N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. p. 192. ISBN 9783406093975.

[T]hese western Saka he distinguishes from eastern Saka who moved south through the Kashgar-Tashkurgan-Gilgit-Swat route to the plains of the sub-continent of India. This would account for the existence of the ancient Khotanese-Saka speakers, documents of whom have been found in western Sinkiang, and the modern Wakhi language of Wakhan in Afghanistan, another modern branch of descendants of Saka speakers parallel to the Ossetes in the west.

- ^ Bailey, H.W. (1982). The culture of the Sakas in ancient Iranian Khotan. Caravan Books. pp. 7–10.

It is noteworthy that the Wakhi language of Wakhan has features, phonetics, and vocabulary the nearest of Iranian dialects to Khotan Saka.

- ^ Carpelan, C.; Parpola, A.; Koskikallio, P. (2001). "Early Contacts Between Uralic and Indo-European: Linguistic and Archaeological Considerations: Papers Presented at an International Symposium Held at the Tvärminne Research Station of the University of Helsinki, 8–10 January, 1999". Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. 242: 136.

...descendants of these languages survive now only in the Ossete language of the Caucasus and the Wakhi language of the Pamirs, the latter related to the Saka once spoken in Khotan.

- ^ "Encolypedia Iranica, AFGHANISTAN vi. Paṣ̌tō".

It is, however, possible that the original home of Paṣ̌tō may have been in Badaḵšān, somewhere between Munǰī and Sangl. and Shugh., with some contact with a Saka dialect akin to Khotanese.

- ^ Indo-Iranica. Kolkata, India: Iran Society. 1946. pp. 173–174.

... and their language is most closely related to on the one hand with Saka on the other with Munji-Yidgha

- ^ Bečka, Jiří (1969). A Study in Pashto Stress. Academia. p. 32.

Pashto in its origin, is probably a Saka dialect.

- ^ Cheung, Jonny (2007). Etymological Dictionary of the Iranian Verb. (Leiden Indo-European Etymological Dictionary Series).

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1939). "The Rāma Story in Khotanese". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 59 (4): 460–468. doi:10.2307/594480. JSTOR 594480.

- ^ Emmerick, Ronald (2009). "Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 377–415.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. pp. 270–283. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Bailey, H. W. (1970). "Saka Studies: The Ancient Kingdom of Khotan". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 8 (1): 68. doi:10.2307/4299633. JSTOR 4299633.

- ^ Michaël Peyrot (2018). "Tocharian B etswe 'mule' and Eastern East Iranian". Farnah. Indo-Iranian and Indo-European Studies in Honor of Sasha Lubotsky. Ann Arbor, N.Y.: Beech Stave Press. pp. 270–283. Retrieved 14 November 2024.

- ^ Emmerick, Ronald E. (2009). "7. Khotanese and Tumshuqese". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. Routledge. pp. 377–415. ISBN 978-1-135-79704-1.

- ^ "Saka language" at Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Kocaoğlu, Timur (2004). "Diwanu Lugatı't-Turk and Contemporary Linguistics" (PDF). MANAS Journal of Turkic Civilization Studies. 1: 165–169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ Levi, Scott Cameron; Sela, Ron, eds. (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ Levi, Scott Cameron; Sela, Ron, eds. (2010). Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ^ History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Crossroads of Civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO Publishing. 1996. pp. 283–. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ^ Akiner, Shirin, ed. (2013). Cultural Change and Continuity in Central Asia. London: Routledge. pp. 71–. ISBN 978-1-136-15034-0.

- ^ Hitch, Douglas (2016). The Old Khotanese Metanalysis (Thesis). Harvard University.

- ^ Emmerick, R. E.; Pulleyblank, E. G. (1993). A Chinese text in Central Asian Brahmi script: new evidence for the pronunciation of Late Middle Chinese and Khotanese. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

- ^ Maggi, M. (2022). "Some remarks on the history of the Khotanese orthography and the Brāhmī script in Khotan". Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University. 25: 149–172.

- ^ Hitch, Douglas (2016). The Old Khotanese Metanalysis (Thesis). Harvard University.

- ^ Kümmel, M. J. (2016). "Einführung ins Ostmitteliranische".

- ^ Wilson, Lee (2015-01-26). "Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Khotanese Script" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21 – via unicode.org.

- ^ "Brāhmī". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- ^ "Bailey, Harold Walter". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2021-08-14. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

Sources

[edit]- "International Dunhuang Project". Archived from the original on 2011-07-20.

- Bailey, H. W. (1944). "A Turkish-Khotanese Vocabulary" (PDF). Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 290–296. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00072475. JSTOR 609315. S2CID 163021887. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-15.

Further reading

[edit]- ""Prothetic H-" in Khotanese and the Reconstruction of Proto-Iranic" (PDF). Martin Kümmel. Script and Reconstruction in Linguistic History―Univerzita Karlova v Praze, March 2020.

- Bailey, H. W. (1979). Dictionary of Khotan Saka. Cambridge University Press.

- "Iranian Languages". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Emmerick, R. E.; Pulleyblank, E. G. (1993). A Chinese text in Central Asian Brahmi script: new evidence for the pronunciation of Late Middle Chinese and Khotanese. Roma: Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. (On connections between Chinese and Khotanese, such as loan words and pronunciations)

- Litvinsky, Boris Abramovich; Vorobyova-Desyatovskaya, M. I. (1999). "Religions and Religious Movements". History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 421–448. ISBN 8120815408.

- Maggi, M. (2022). "Some remarks on the history of the Khotanese orthography and the Brāhmī script in Khotan". Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University. 25: 149–172.

Saka language

View on GrokipediaClassification

Linguistic affiliation

The Saka language is classified within the Indo-European language family, specifically as part of the Indo-Iranian branch, the Iranian subgroup, and the Eastern Iranian division, forming its own Saka branch alongside other extinct varieties like Scythian and Alanian.[1][4] This hierarchical placement reflects its evolution from Proto-Indo-European through shared Indo-Iranian features, such as the merger of PIE *s with *ś and the development of aspirated stops into fricatives, before diverging into Iranian-specific traits.[7] As a Middle Iranian language group, Saka is distinguished from Western Iranian languages like Parthian and Middle Persian by its geographical and linguistic separation, with Saka attested primarily in Central Asia during the first millennium CE.[8][4] Unlike Western Iranian, which shows innovations such as the loss of initial *y- and widespread rhotacism, Saka retains certain Eastern characteristics, including the preservation of intervocalic stops in some forms.[1] Comparative linguistics provides key evidence for Saka's Eastern Iranian affiliation through shared innovations, notably the development of Proto-Iranian *č (from Indo-Iranian *ć < PIE *ḱ) to /s/ in Eastern Iranian languages, contrasting with /θ/ in Western Iranian; for instance, "hundred" appears as Avestan *satəm and Khotanese Saka *sa- versus Old Persian *θata-.[7][4] This sound shift, along with the retention of *θ in other positions (e.g., Sogdian myθ "month"), underscores the unity of the Eastern branch.[1] The name "Saka" originates from ancient attestations linking it to the nomadic peoples described in classical sources, where Herodotus (Histories 4.6) identifies the Saka as Scythians of the eastern steppes, with the term appearing in Old Persian inscriptions as Saka- for these tribes.[9] This etymological connection ties the language to the ethnic Saka/Scythian identity, though the precise root remains debated among Iranists.[10]Relation to other Iranian languages

The Saka language belongs to the Eastern Iranian branch and is classified as part of the broader Scythian group of languages, which encompasses various nomadic Iranian dialects spoken across the Eurasian steppes and Central Asia. This affiliation is evidenced by shared phonological innovations.[11] Saka exhibits close links to Avestan and Sogdian through retained archaisms from Old Iranian, including certain nominal endings like the genitive plural forms that preserve long-vowel patterns not generalized in all Eastern Iranian languages. In Khotanese Saka, the third-person plural ending -āre mirrors developments in Sogdian and Yaghnobi, while causative suffixes like *-āuśaiśa- appear in both Saka and Sogdian, indicating shared morphological heritage. However, Saka diverges by losing aspiration in voiced stops, a change common across Iranian languages but leading to unique phonetic outcomes, such as simplified consonant clusters compared to Avestan's more conservative system. Cognates like Saka *aspa- 'horse' directly correspond to Avestan aspa- and Sogdian asb-, underscoring lexical continuity.[11][12][13] Relative to modern Eastern Iranian languages, Saka represents an early parallel branch rather than a direct ancestor, sharing retroflexion patterns (e.g., *rt > ḍ) with Pashto and Wakhi but differing in specifics like *śr > ṣ. It aligns with Ossetic in broader Scythian traits, as Ossetic descends from the Alanian dialect of the Scytho-Sarmatian continuum, though debates persist on whether Saka forms a coordinate subgroup or a distinct eastern offshoot within this phylum. Examples include Saka nāma- 'name' cognate with Pashto nām and Ossetic nom, highlighting persistent lexical ties despite geographic separation. Scholars debate the exact phyletic position, with some viewing Saka as more innovative than Avestan but archaically conservative compared to later Pashto developments.[11][14][15]Dialects

Khotanese

Khotanese, the most extensively documented dialect of the Saka language, was spoken in the Kingdom of Khotan located in the southern Tarim Basin of modern-day Xinjiang, China, where it served as the primary language of a vibrant Buddhist culture from the 5th to the 10th centuries CE.[2] This dialect flourished amid the oasis city-states along the Silk Road, with its speakers engaging in trade, administration, and religious scholarship, producing a rich literary tradition centered on Mahayana Buddhism.[3] The Khotanese dialect is traditionally divided into two main phases: Old Khotanese (ca. 5th–8th centuries CE) and Late Khotanese (9th–10th centuries CE), with some scholars proposing a transitional Middle Khotanese phase in the 7th–8th centuries.[2] Old Khotanese represents an earlier, more conservative stage, characterized by a complex phonological system with 11 vowel phonemes distinguished by quantity, while Late Khotanese shows shifts toward qualitative distinctions in vowels and greater simplification in morphology, such as the merger of certain case endings and the reduction of plural forms. Morphologically, Old Khotanese retains a relatively intact inflectional system inherited from Old Iranian, including six cases in the singular (nominative, accusative, instrumental, ablative, genitive-dative, and locative) and five in the plural, reflecting a partial preservation of the proto system's eight cases; in Late Khotanese, these undergo further syncretism, with the genitive-dative plural evolving into a general oblique marker.[16][17] Key linguistic features of Khotanese include its use of a Brahmi-derived script, adapted into a distinctive cursive form known as Khotanese Brahmi, which evolved from earlier ornamental styles to more fluid variants in later periods.[18] This script facilitated the recording of Buddhist sutras, commentaries, and administrative documents, underscoring the dialect's role in preserving Indo-Iranian heritage within a Buddhist context.[19] Attestation of Khotanese is abundant, with over 2,300 manuscripts and fragments surviving, predominantly Buddhist texts such as translations of the Tripitaka and indigenous compositions like the Book of Zambasta.[18][20] These documents, discovered in sites like Dunhuang and the Khotan region, highlight the dialect's conservatism in vocabulary, retaining archaic Iranian terms such as ssa from Old Iranian sata- 'hundred', which persisted unchanged across phases unlike innovations in neighboring languages.[21] In contrast to the fragmentarily attested Tumshuqese, Khotanese's extensive corpus provides the primary window into Saka linguistic evolution.Tumshuqese

Tumshuqese, a dialect of the Saka language, was spoken in the Tumshuq region of the northern Tarim Basin in what is now Xinjiang, China, located north of the Khotan oasis and in proximity to areas where Tocharian languages were used, suggesting it may represent a northern or earlier variant of Eastern Iranian speech.[22] This geographic position likely contributed to its distinct development, potentially incorporating substrate influences from neighboring non-Iranian languages.[1] The attestation of Tumshuqese is extremely limited, consisting of roughly 15 fragmentary manuscripts discovered by archaeologist Aurel Stein during his second Central Asian expedition (1906–1908) at the ancient site of Tumxuk (modern Tumshuq); recent handlists identify around 67 fragments, though many are small, with key publications by Konow (1935) and Maue (2009).[23][24] These documents, primarily written in a Northern Brahmi-derived script, date to the late 7th or early 8th century CE based on paleographic and historical analysis, and include a mix of secular materials such as administrative contracts, letters, and economic records, alongside a few Buddhist texts like portions of jātakas.[25] The small corpus has made comprehensive study challenging, with many fragments remaining unpublished or only partially transliterated, limiting insights into its full grammatical structure.[26] Key phonological features of Tumshuqese distinguish it as more archaic than its southern counterpart, Khotanese; notably, it retains initial *s- from Proto-Iranian where Khotanese innovates with h-, such as 'seven' (Tumshuqese sapt vs. Khotanese hapta).[22] Morphologically, Tumshuqese displays a simplified system with fewer nominal cases—typically reduced to nominative, accusative, and genitive-dative—compared to the more elaborate case inventory in Khotanese, reflecting possible analogical leveling or contact-induced changes.[26] Pronominal forms also preserve earlier Indo-Iranian stages, such as the first-person singular *azū versus Khotanese āzu.[22] Scholars debate the precise status of Tumshuqese within the Saka dialect continuum, with some viewing it as a distinct northern dialect closely related to Khotanese but conservative in phonology, while others propose it as a transitional form potentially influenced by Tocharian due to shared geographic and cultural contacts, evidenced by lexical borrowings and script adaptations.[1] This uncertainty stems from the sparse evidence, but analyses of shared innovations confirm its affiliation as an Eastern Middle Iranian language alongside Khotanese.[26]History

Origins and speakers

The Sakas were nomadic Eastern Iranian tribes belonging to the broader Scythian cultural and linguistic confederations, originating from the Central Asian and Eurasian steppes. Emerging as distinct groups by the 9th century BCE, they undertook significant migrations southward and eastward between the 8th and 2nd centuries BCE, prompted by conflicts with neighboring nomads such as the Yuezhi and Xiongnu, which displaced them from their steppe homelands toward the Tarim Basin and beyond.[27][28] Linguistically, the Saka language developed from post-Avestan Old Iranian as an Eastern Iranian variety within the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European family, reflecting the divergence of Iranian speakers in Central Asia after the 2nd millennium BCE. Through interactions in the Tarim Basin, it incorporated influences from neighboring Indo-Aryan languages, seen in shared substrate vocabulary related to agriculture and religion (e.g., terms for camel and brick), and from Tocharian, including loans for materials like mud bricks and iron, indicative of early cultural exchanges in the Bactria-Margiana region around 2000 BCE.[29][30] Early historical evidence of the Sakas appears in Han dynasty Chinese annals (ca. 206 BCE–220 CE), which refer to them as the "Sai" tribes and document their presence in the western regions of Central Asia, including migrations southward due to Yuezhi incursions before 128 BCE. In Indian literary sources, the Mahābhārata (composed ca. 400 BCE–400 CE) portrays the Sakas as a foreign mleccha tribe settled along the Indus River banks, associating them with northwestern borderlands and conflicts involving Indo-Aryan kingdoms.[31][32] By the 1st century BCE, Saka groups had settled in the Tarim Basin oases, founding kingdoms in Khotan and Kashgar, where they shifted from pastoral nomadism to sedentary agrarian and mercantile societies, increasingly integrating Buddhism as a dominant cultural and religious framework.[28][27]Period of attestation

The attested corpus of the Saka language, comprising both the Khotanese and Tumshuqese dialects, spans approximately from the mid-5th century CE to the early 11th century CE, with the bulk of surviving manuscripts dating to the 7th–10th centuries. The earliest fragments in Tumshuqese, a dialect spoken in the region near modern Tumxuk, are assigned to the late 7th or 8th century CE based on paleographic analysis and contextual associations with dated Buddhist artifacts from the Tarim Basin. Old Khotanese texts, representing the primary dialect from the Kingdom of Khotan, begin in the second half of the 5th century CE and reach their peak production between the 7th and 9th centuries CE, as evidenced by literary and documentary works such as Buddhist sūtras and administrative records.[33] Late Khotanese, characterized by phonological and orthographic shifts, continued until around 1100 CE, with some fragments possibly extending slightly later.[34] In the sociolinguistic context of the Tarim Basin, Saka served as a key administrative and religious language in the Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan, facilitating governance, trade along the Silk Road, and the dissemination of Mahāyāna Buddhism through translations and commentaries.[21] It coexisted with Tocharian in the northern and eastern oases and Chinese as a lingua franca for imperial interactions, reflecting the multilingual environment of the region where Iranian, Indo-European, and Sino-Tibetan languages interacted in Buddhist monastic and commercial settings.[35] The decline of Saka began with the gradual Turkic migrations into the Tarim Basin, culminating in the conquest of Khotan by the Kara-Khanid Khanate around 1006 CE, which imposed Islam and accelerated language shift toward Turkic varieties, including early Uyghur, leading to the extinction of Saka as a spoken language in the following centuries.[36] Archival evidence for these dates derives primarily from colophons—scribes' notes appended to manuscripts that often include explicit calendar dates—and supplementary radiocarbon analyses of the supporting materials, such as paper or wood, which corroborate the textual attributions for many Khotanese documents from Dunhuang and Khotan sites.[37]Writing system

Scripts employed

The Saka language, encompassing the Khotanese and Tumshuqese dialects, was recorded using adapted variants of the Brahmi script, an abugida derived ultimately from ancient Indian writing systems that trace their origins to Aramaic influences through early Indic developments. This script was introduced to the Tarim Basin regions around the 4th to 5th centuries CE by Indian Buddhist missionaries, marking the earliest attested writing for Saka; no indigenous pre-Buddhist script has been documented for the language.[38][39][18] For Old Khotanese texts, the primary script was a formal variant of Central Asian Brahmi, influenced by Kushan and Gupta forms, which included modifications such as digraphs (e.g., ys for /z/) and new signs to accommodate Iranian phonemes absent in standard Sanskrit orthography. By the period of Late Khotanese (roughly 9th–10th centuries CE), the script evolved into more fluid cursive styles, particularly for administrative and documentary purposes, while retaining core Brahmi structures.[40][18][38] Tumshuqese, attested in fewer fragments from the 5th–8th centuries CE, employed formal Brahmi in its North Turkestan literary style for religious texts like the Karmavacana, alongside cursive business script variants for practical documents; these shared close paleographic ties with Khotanese but featured distinct adaptations for local phonology.[41][40] Manuscripts in these scripts were inscribed on diverse materials, including wooden slips for early economic records, palm leaves for Buddhist sutras, and paper for later compositions, reflecting the technological exchanges along the Silk Road. The writing direction was consistently left-to-right, aligning with the standard orientation of Brahmi derivatives.[18][38][42]Phonology

Consonants

The consonant system of Old Khotanese Saka distinguishes phonemes across labial, dental, retroflex, palatal, velar, and glottal places of articulation, with voiceless (plain and aspirated), voiced pairs for stops and affricates, reflecting typical Eastern Iranian features including frequent palatalization and retroflexion.[43][2] This inventory is reconstructed primarily from transliterations of Brāhmī-script manuscripts and comparative analysis with other Iranian languages.[44] The core stops include voiceless plain /p, t, ṭ, k/ and aspirated /ph, th, ṭh, kh/, with voiced /b, d, ḍ, g/. Affricates comprise palatal voiceless /č/ and aspirated /čh/, voiced /ǰ/, as well as alveolar /ts/ and aspirated /tsh/, voiced /dz/. Fricatives include voiceless /s/ (dental), /ṣ/ (retroflex), /š/ (palatal), /x/ (velar), and /h/ (glottal), with voiced counterparts /z/, /ẓ/, /ž/, /γ/; nasals by /m/ (labial), /n/ (dental, with allophones including palatal /ñ/ and retroflex /ṇ/), liquids by /r/ and /l/ (dental/alveolar, with retroflex /ṛ/), and semivowels by /w/ (labial) and /y/ (palatal). Palatalization processes, common in Eastern Iranian branches, often affect dentals and velars before front vowels, yielding affricates or palatal variants.[45]| Labial | Dental | Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops (voiceless plain) | p | t | ṭ | k | ||

| Stops (aspirated voiceless) | ph | th | ṭh | kh | ||

| Stops (voiced) | b | d | ḍ | g | ||

| Affricates (voiceless palatal) | č | |||||

| Affricates (aspirated palatal) | čh | |||||

| Affricates (voiced palatal) | ǰ | |||||

| Affricates (voiceless alveolar) | ts | |||||

| Affricates (aspirated alveolar) | tsh | |||||

| Affricates (voiced alveolar) | dz | |||||

| Fricatives (voiceless) | s | ṣ | š | x | h | |

| Fricatives (voiced) | z | ẓ | ž | γ | ||

| Nasals | m | n | ṇ | ñ | ||

| Liquids | r, l | ṛ | ||||

| Semivowels | w | y |