Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sint Eustatius

View on Wikipedia

Sint Eustatius,[b][7] known locally as Statia,[c][8] is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially "public body") of the Netherlands.[9]

Key Information

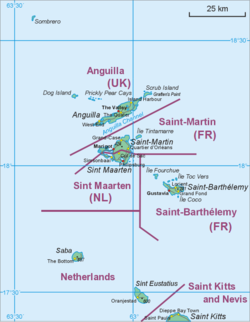

The island is in the northern Leeward Islands, southeast of the Virgin Islands. Sint Eustatius is immediately to the northwest of Saint Kitts and southeast of Saba. The regional capital is Oranjestad. The island has an area of 21 square kilometres (8.1 sq mi).[2] Travelers to the island by air arrive through F. D. Roosevelt Airport.

Formerly part of the Netherlands Antilles, Sint Eustatius became a public body of the Netherlands in 2010.[10] It is part of the Dutch Caribbean, which consists of Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao, Saba, Sint Eustatius, and Sint Maarten. Together with Bonaire and Saba, it forms the BES Islands, also referred to as the Caribbean Netherlands.[11]

Sint Eustatius played a major role in the American War for Independence, supplying American insurgents with war material, especially gunpowder. The British captured St. Eustatius, which was a major blow to the U.S. and its European allies. The French navy later in the war recaptured the island.[12]

Etymology

[edit]The island's name, Sint Eustatius, is Dutch for Saint Eustace (also spelled Eustachius or Eustathius), a legendary Christian martyr, known in Spanish as San Eustaquio and in Portuguese as Santo Eustáquio or Santo Eustácio.

The island's prior Dutch name was Nieuw Zeeland ('New Zeeland'), named by the Zeelanders who settled there in the 1630s.[13][14] It was renamed Sint Eustatius shortly thereafter.[13]

The Arawak name for the island was Aloi "Cashew Island".[15][16]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The earliest inhabitants were Caribs[17] believed to have come from the Amazon basin (South America) and migrated north from Venezuela[17] via the Lesser Antilles.[17] In the early 20th century, settlement traces were discovered at Golden Rock and Orange Bay. Multiple pre-Columbian sites have been found on the island, most notably the site referred to as the "Golden Rock Site".[18]

While the island may have been seen by Christopher Columbus in 1493,[19] the first recorded sighting was in 1595 by Francis Drake and John Hawkis.[19][20] From the first European settlement in the 17th century, until the early 19th century, St. Eustatius changed hands twenty-one times between the Netherlands, Britain, and France.[19][21]

In 1625, English and French settlers arrived on the island.[22][23] In 1629, the French built a wooden battery at the present-day location of Fort Oranje.[24] Both the English and the French left the island within a few years due to lack of drinkable water.[25][26]

Dutch West India Company

[edit]In 1636, the chamber of Zeeland of the Dutch West India Company took possession of the island,[27][23] reported to be uninhabited at the time.[28][29] In 1678 the islands of St. Eustatius, Sint Maarten and Saba were under the direct command of the Dutch West India Company, with a commander stationed on St. Eustatius to govern all three.[citation needed] At the time, the island was of some importance for the cultivation of tobacco and sugar.[30] More important was the role of St. Eustatius in the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the intercolonial slave trade.[19][31]

Free port and slave trade

[edit]

Sint Eustatius became the most profitable asset of the Dutch West India Company[citation needed] and a transit point for enslaved Africans in the transatlantic slave trade.[30][32] The ruins of the Waterfort on the southwest coast of the island are reminders of this past. A slave house of two floors was in the Waterfort. Plantations of sugarcane, cotton, tobacco, coffee and indigo were established on the island and worked with labor of enslaved Africans.[32] In 1774 there were 75 plantations on the island[citation needed] with names such as Gilboa, Kuilzak, Zelandia, Zorg en Rust, Nooit Gedacht, Ruym Sigt and Golden Rock.

In the 18th century, St. Eustatius's geographical placement in the middle of Danish (Virgin Islands), British (Jamaica, St. Kitts, Barbados, Antigua), French (St. Domingue, Ste. Lucie, Martinique, Guadeloupe) and Spanish (Cuba, Santo Domingo, Puerto Rico) territories—along with its large harborage, neutrality and status from 1756[8] as a free port with no customs duties—were all factors in it becoming a major point of transhipment of African slaves, goods, and a locus for trade in contraband.[8][33] Transshipment of captured Africans to the British, French, and Spanish islands of the eastern Caribbean was significant enough that the colonists built a two-story slave house at the fortress Amsterdam (also known as Waterfort) to serve as a depot of enslaved Africans until around 1740.[34] The depot housed about 400–450 people.[35]

St. Eustatius's economy flourished under the Dutch by ignoring the monopolistic trade restrictions of the British, French and Spanish islands[citation needed]; it became known as the "Golden Rock".[36][37][38] Edmund Burke said of the island in 1781:

It has no produce, no fortifications for its defence, nor martial spirit nor military regulations ... Its utility was its defence. The universality of its use, the neutrality of its nature was its security and its safeguard. Its proprietors had, in the spirit of commerce, made it an emporium for all the world. ... Its wealth was prodigious, arising from its industry and the nature of its commerce.[8]

"First Salute"

[edit]

The island sold arms and ammunition to anyone willing to pay, and it was therefore one of the few places from which the young United States could obtain military stores. The good relationship between St. Eustatius and the United States resulted in the noted "First Salute". On 16 November 1776, the 14-gun American brig Andrew Doria commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson[39][33] sailed, flying the Continental Colors of the fledgling United States, into the anchorage below St. Eustatius's Fort Oranje. Robinson announced his arrival by firing a thirteen gun salute, one gun for each of the thirteen American colonies in rebellion against Britain. Governor Johannes de Graaff replied with an eleven-gun salute from the cannons of Fort Oranje (international protocol required two guns fewer to acknowledge a sovereign flag). It was the first international acknowledgment of American independence.[Note 1] The Andrew Doria had arrived to purchase munitions for the American Revolutionary forces. She was carrying a copy of the Declaration of Independence which was presented to Governor De Graaff. An earlier copy had been captured by the British on its way to Holland. It was wrapped in documents that the British believed to be a strange cipher, but were actually written in Yiddish, addressed to Jewish merchants in Holland.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited St. Eustatius for two hours on 27 February 1939 on USS Houston to recognise the importance of the 1776 "First Salute". He presented a large brass plaque to St. Eustatius, displayed today under a flagpole atop the walls of Fort Oranje, reading:

In commemoration to the salute to the flag of the United States, Fired in this fort November 16. 1776, By order of Johannes de Graaff, Governor of Saint Eustatius, In reply to a National Gun-Salute, Fired by the United States Brig of War Andrew Doria, Under Captain Isaiah Robinson of the Continental Navy, Here the sovereignty of the United States of America was first formally acknowledged to a national vessel by a foreign official. Presented by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, President of the United States of America

The recognition provided the title for Barbara W. Tuchman's 1988 book The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution.

Capture by British Admiral George Rodney 1781

[edit]The British took the Andrew Doria incident seriously, and protested bitterly against the continuous trade between the United Colonies and St. Eustatius. In 1778, Lord Stormont claimed in Parliament that, "if Sint Eustatius had sunk into the sea three years before, the United Kingdom would already have dealt with George Washington". Nearly half of all American Revolutionary military supplies were obtained through St. Eustatius. Nearly all American communications to Europe first passed through the island. The trade between St. Eustatius and the United States was the main reason for the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War of 1780–1784.[33] Notably, the British Admiral George Brydges Rodney, having occupied the island for Great Britain in 1781, urged the commander of the landing troops, Major-General Sir John Vaughan, to seize "Mr. Smith at the house of Jones – they (the Jews of St. Eustatius, Caribbean Antilles)[40] cannot be too soon taken care of – they are notorious in the cause of America and France".[41][42] The war was disastrous for the Dutch economy.

Britain declared war on the Dutch Republic on 20 December 1780. Even before officially declaring war, Britain had outfitted a massive battle fleet to take and destroy the weapons depot and vital commercial centre that St. Eustatius had become. British Admiral George Brydges Rodney was appointed the commander of the battle fleet. 3 February 1781, the massive fleet of 15 ships of the line and numerous smaller ships transporting over 3,000 soldiers appeared before St. Eustatius prepared to invade. Governor De Graaff did not know about the declaration of war. Rodney offered De Graaff a bloodless surrender to his superior force. Rodney had more than 1,000 cannon to De Graaff's one dozen cannon and a garrison of sixty men. De Graaff surrendered the island, but first fired two rounds as a show of resistance in honor of Dutch Admiral Lodewijk van Bylandt, who commanded a ship of the Dutch Navy which was in the harbor.[8] Ten months later, the island was conquered by the French, allies of the Dutch Republic in the war. The Dutch regained control over the looted and plundered island in 1784.[41][43]

A series of French and British occupations of Sint Eustatius from 1795 to 1815 during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars diverted trade to the occupiers' islands. St. Eustatius's economy collapsed, and the merchants, including the Jews left. St. Eustatius reverted permanently to Dutch control from 1816.

At its peak, St. Eustatius may have had a largely transient population of about 10,000 people. Most were engaged in commercial and maritime interests. A census list of 1790 gives a total population (free and enslaved people combined) of 8,124. Commerce revived after the island returned to Dutch control. Many of the merchants (including the Jews) returned to the island. However, the French and British occupations disrupted trade and also the Americans, now globally recognised as an independent nation, had meanwhile developed their own trading network and did not need St. Eustatius anymore. The island was eclipsed by other Dutch ports, such as those on the islands of Curaçao and Sint Maarten. During the last years of the 18th century Statia developed trade in bay rum. The economy declined in the early 19th century. From about 1795 the population declined, dropping to 921 in 1948.

Jewish population

[edit]The first record of Jews on St. Eustatius dates to 1660.[44][45][46][47][48][49][50] The Jews were mainly merchants with significant international trading and maritime commercial ties. Jews were captains, owners or co-owners with Christian partners, of significant numbers of ships originating out of St. Eustatius. A few were island plantation owners. By 1750, Jews comprised over half of the island's free population, with more than 450 individuals among 802 free citizens.[48][49]

Ten days after the island surrendered to the British on 3 February 1781, Rodney ordered that the entire Jewish male adult population assemble for him. They were rounded up and 31 heads of families were summarily deported to St. Kitts without word or mercy to their dependents.[51] The choice of exiling the Jews to St. Kitts was significant. The nearby British colony of Nevis had a large Jewish population and an established community capable of aiding the refugees. St. Kitts did not have any Jewish community or population. The other seventy-one were locked up in the weighing house in Lower Town where they were held for three days.

Expulsion of Americans followed on 23 February, of merchants from Amsterdam on 24 February and of other Dutch citizens and Frenchmen on 5 March. The crews of the Dutch ships Rodney took were sent to St. Kitts for imprisonment – after first stripping them of all their belongings. Because of their maltreatment, many perished. The Jews were well received on St. Kitts – where many knew them as their respected business partners. They were supported in their protest against their deportation and it proved successful. They were allowed to return to St. Eustatius after a few weeks to observe all their property being sold at small fractions of the original value after having been confiscated by Rodney. There were numerous complaints about "individuals of both sexes being halted in the streets and being body searched in a most scandalous way."[52] Pieter Runnels, an eighty-year-old member of the island council and captain of the civic guard, did not survive the rough treatment he received aboard Rodney's ship. He, a member of one of the island's oldest-established families, became the only civilian casualty of the British occupation.

Rodney singled out the Jews: the harshness was reserved for them alone. He did not do the same to French, Dutch, Spanish or even the American merchants on the island. He permitted the French to leave with all their possessions. Rodney was concerned that his unprecedented behavior would be repeated upon British islands by French forces when events were different. However, Governor De Graaff was also deported. As he did with all other warehouses, Rodney confiscated the Jewish warehouses, looted Jewish personal possessions, even cutting the lining of their clothes to find money hidden in there. When Rodney realized that the Jews might be hiding additional treasure, he dug up the Jewish cemetery.[51]

Later, in February 1782, Edmund Burke, the leading opposition member of the Whig Party, upon learning of Rodney's actions in St. Eustatius, rose to condemn Rodney's actions in Parliament:

...and a sentence of general beggary pronounced in one moment upon a whole people. A cruelty unheard of in Europe for many years… The persecution was begun with the people whom of all others it ought to be the care and the wish of human nations to protect, the Jews… the links of communication, the mercantile chain… the conductors by which credit was transmitted through the world... a resolution taken to banish this unhappy people from the island. They suffered in common with the rest of the inhabitants, the loss of their merchandise, their bills, their houses, and their provisions; and after this they were ordered to quit the island, and only one day was given them for preparation; they petitioned, they remonstrated against so hard a sentence, but in vain; it was irrevocable. [53]

The synagogue and the cemetery

[edit]

From about 1815, when there was no longer a viable Jewish community using and maintaining the synagogue on St. Eustatius, it gradually fell into ruin.

The synagogue building, known as Honen Dalim, (חונן דלים, He who is charitable to the Poor) was built in 1737.[54][47][55][50] Permission for building the synagogue came from the Dutch West India Company, additional funding came from the Jewish community on Curaçao. Permission was conditional on the fact that the Jewish house of worship would be sited where "the exercise of their (Jewish) religious duties would not molest those of the Gentiles".[56] The building is off a small lane called Synagogue Path, away from the main street. The synagogue attested to the wealth of the Jews of St. Eustatius and their influence on the island.[57]

In 2001, its walls were restored as part of the Historic Core Restoration Project, although there are no known images showing what the synagogue looked like when still in use, so that archeological research is attempting to restore the structure to the best estimate of its former condition. The grounds include a Jewish ritual bath (mikveh) and an oven used on Passover. A restored and respectfully maintained Jewish cemetery is next to the Old Church Cemetery, at the top of Oranjestad, Sint Eustatius.

Slave Revolt of 1848

[edit]After 1848, slavery only existed on the Dutch and Danish Eastern Caribbean islands, which caused unrest on the islands colonized by the Netherlands. As a result, a proclamation declared on 6 June 1848 on Sint Maarten that enslaved Africans would be treated as free persons.[58]

Unrest also arose on Sint Eustatius. On 12 June 1848, a group of free and enslaved Africans gathered in front of Lieutenant Governor Johannes de Veer's home demanding their declaration of liberty, increased rations, and more free hours. The Island Governor addressed the group, but it persisted in its demands. The militia was mobilized and, after consultation with the Colonial Council and the main residents, an attack was decided by the Lieutenant Governor. After another warning to leave the city or otherwise experience the consequences, fire was opened on the group. The insurgents fled the city, leaving two or three seriously injured. From a hill just outside the city they pelted the militia with stones and pieces of rock. A group of 35 shooters stormed the hill, killing two insurgents and injuring several. The six leaders of the uprising were exiled from the island and transferred to Curaçao. Thomas Dupersoy, a free African, is considered the chief leader of the uprising. One of the other leaders sent a death notice to his owner in 1851. After the uprising, the largest plantation owners on Sint Eustatius decided to give their enslaved workers a certain wage for fear of repetition of revolt.[59]

Abolition of slavery

[edit]In 1863 slavery was officially abolished in the Netherlands. The Dutch were among the last to abolish slavery.[60] The freed slaves no longer wanted to live in the field and moved to the city. Due to a lack of trade, the bay of Sint Eustatius underwent a recession. Natural disasters such as the hurricane of September 1928 and May 1929 accelerated the process of economic decline on the island.

Dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles

[edit]Sint Eustatius became a member of the Netherlands Antilles when that grouping was created in 1954. Between 2000 and 2005 the member islands of the Netherlands Antilles voted on their future status. In a referendum on 8 April 2005, 77% of Sint Eustatius voters voted to remain within the Netherlands Antilles, compared to 21% who voted for closer ties with the Netherlands. None of the other islands voted to remain.

After the other islands decided to leave, ending the Netherlands Antilles, the island council opted to become a special municipality of the Netherlands, like Saba and Bonaire. This process was completed in October 2010.[33] In 2011 the island officially adopted the US dollar as its currency.[61]

Geography

[edit]

Sint Eustatius is 6 miles (10 km) long and up to 3 miles (5 km) wide.[33] Topographically, the island is saddle-shaped, with the 602-metre (1,975 ft) high dormant volcano Quill (Mount Mazinga), (from Dutch kuil, meaning 'pit'—originally referring to its crater) to the southeast and the smaller summits of Signal Hill/Little Mountain (or Bergje) and Boven Mountain to the northwest. The Quill crater is a popular tourist attraction on the island. The bulk of the island's population lives in the flat saddle between the two elevated areas, which forms the centre of the island.[33]

Climate

[edit]St. Eustatius has a tropical monsoon climate. Tropical storms and hurricanes are common. The Atlantic hurricane season runs from 1 June to 30 November, sharply peaking from late August through September. Tropical Cyclone Climatology

Nature

[edit]

As St. Eustatius is a volcanic island and very small, all of the beaches on the island are made up of black volcanic sand. These volcanic sands, especially one of the more popular nesting beaches called Zeelandia, are very important nesting sites for several endangered sea turtles such as: the green turtle, leatherback, loggerhead and hawksbill.[62]

Sint Eustatius is home to one of the last remaining populations of the critically endangered Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima).[63] The population was strongly affected during the high-intensity hurricane year of 2017, with especially Hurricane Maria, during which the population declined by 25%.[64]

National parks

[edit]Sint Eustatius has three nature parks – on land and at sea: the Sint Eustatius National Marine Park, Quill/Boven National Park, and Miriam Schmidt Botanical Garden. Two of them have national park status. These areas have been designated as important bird areas. The nature parks are maintained by the St Eustatius National Parks Foundation (STENAPA).[65]

Archaeology

[edit]Due to its turbulent history, Sint Eustatius is rich in archaeological sites. Nearly 300 sites have been documented.[66] The island is said to have the highest concentration of archaeological sites of any area of comparable size.[67] In the 1920s, J. P. B. de Josselin de Jong conducted archaeological research into Saladoid sites on the island and in the 1980s a great deal of research at the Golden Rock site was done by archaeologist Aad Versteeg of Leiden University. Around 1981, under the direction of archaeologist Norman F. Barka, the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia also started archaeological research on Sint Eustatius. The documented archaeological sites include prehistoric sites, plantations, military sites, commercial trading sites (including shipwrecks), and urban sites (churches, government buildings, cemeteries, residences). The St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research (SECAR) has been conducting archaeological research on the island since 2004[68] including excavations at the Godet African Burial Ground and the Golden Rock African Burial Ground.

In June 2021, SECAR became involved in protests against excavations at the 18th-century burial ground Golden Rock on the island. The Ubuntu Connected Front and other concerned citizens of Sint Eustatius denounced the non-involvement of the community in the excavation process through a petition and letters to the government.[69][70][71] The majority of the population on St. Eustatius are of African descent. Participation in cultural heritage, i.e. involving the community whose ancestors are being excavated, is good practice in contemporary archaeology.[72] Archaeological excavations on St. Eustatius apparently fall under the old Monuments Act for the BES islands[73] that is very brief on these issues. The 2016 Dutch Heritage Act[74] offers more protection for cultural heritage. The Committee on Kingdom Relations asked State Secretary Raymond Knops questions about the matter.[75] The Statia Heritage and Research Commission (SHRC) set up by the government of St. Eustatius investigated the allegations of the protest groups and published its report in January 2022.[76][77]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]As of January 2025, the population was 3,270,[78] with a population density of 154 inhabitants per square kilometre.

The majority of Sint Eustatius is of African descent, with minorities of European and Asian descent also present. Around 20 nationalities live on the island as well.[79]

Language

[edit]The official language is Dutch, but English is the "language of everyday life" on the island and education is solely in English.[80] A local English-based creole is also spoken informally. More than 52% of the population speak more than one language. The most widely spoken languages are English (92.7%), Dutch (36%), Spanish (33.8%) and Papiamento (20.8%).

Religion

[edit]The population of Sint Eustatius is predominantly Christian. The main denominations are Methodism (28.6%), Roman Catholicism (23.7%), Seventh-Day Adventist (17.8%), Pentecostalism (7.2%) and Anglicanism (2.6%).[81]

- Protestant (56.2%)

- Roman Catholic (23.7%)

- Other Christian denomination or religion (5.20%)

- No denomination (14.9%)

Economy

[edit]

In the 18th century, "Statia" was the most important Dutch island in the Caribbean and was a center of great wealth from trading. At this time it was known as the "Golden Rock" because of its immense wealth. A very large number of warehouses lined the road that runs along Oranje Bay; most (but not all) of these warehouses are now ruined and some of the ruins are partially underwater.

A French occupation in 1795 was the beginning of the end of great prosperity for Sint Eustatius.

The government is the largest employer on the island, and the oil terminal owned by GTI Statia is the largest private employer.[82]

Energy and water

[edit]

Statia Utility Company N.V. provides electricity to the island, as well as drinking water per truck and on part of the island by a water network. The electricity supply is rapidly being made green. Until 2016 all electricity was produced by diesel generators. In March 2016 the first phase of the solar park with 1.89 MWp capacity became operational, covering 23% of entire electricity demand. In November 2017[83] another 2.15 MWp was added, totaling 14,345 solar panels, with 4.1 MW capacity and a yearly production of 6.4 GWh. The solar park includes lithium-ion batteries of 5.9 MWh size. These provide power for grid stability, as well as energy shifting. On a sunny day the diesel generators are switched off from 9 a.m. to 8 pm. This is made possible by grid-forming inverters produced by SMA. This is one of the first such solar parks in the world and provides 40% to 50% of the island's electricity.[citation needed]

Transportation

[edit]The F. D. Roosevelt Airport (IATA: EUX) offers flights to Sint Maarten and Anguilla.[84]

As of March 2025, Makana operated ferries six days a week to and from Philipsburg on the Dutch part of Sint Maarten, with continuing service to the Dutch island of Saba, as well as a direct ferry link to and from St. Kitts (Port Zante in Basseterre).[85][86]

There is no regularly scheduled public transportation, such as public buses or minibuses, on Statia.[87]

Education

[edit]Dutch government policy towards St. Eustatius and other SSS islands promoted English medium education. Sint Eustatius has bilingual English–Dutch education.[88]

Gwendoline van Putten School (GVP) is a secondary school on the island.

Other schools include: Golden Rock School, Gov. de Graaff School, Methodist School, SDA School.[89]

Sports

[edit]The most popular sports on Sint Eustatius are football,[90] futsal,[91][92] softball,[93] basketball, swimming and volleyball. Due to the small population, there are few sport associations. One of them, the Sint Eustatius Volleyball Association, is a member of ECVA and NORCECA. Currently St. Eustatius is a non-active member of the Caribbean zone of Pony Baseball and Softball leagues.

Famous Statians

[edit]- Mariana Franko (1718–1779), freedom fighter

- Antony Beaujon (c. 1763–1805), colonial governor

- Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832–1912), educator and diplomat; born in Saint Thomas from Statian parents

- Gerald Berkel (b. 1969), politician

- Black Harry (18th century), methodist preacher

- Kizzy (b. 1979), artist

- Lolita Euson (1914–1994), writer and poet

- Ziggi Recado (b. 1981), artist

- Shirma Rouse (b. 1980), singer

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ .bq is designated, but not in use, for the Caribbean Netherlands.[5][6] Like the rest of the Netherlands, .nl is primarily in use.

- ^ /juːˈsteɪʃəs/ yoo-STAY-shəs, Dutch: [sɪnt øːˈstaː(t)sijʏs] ⓘ

- ^ /ˈsteɪʃə/ STAY-shə

- ^ The first salute to the Colors may have occurred one month earlier. It is debatable if a Colonial merchantman received a formal salute from Fort Frederik on the Danish island of St Croix (The birth of our Flag page 13 published 1921) and (Americas Library) Translated from the Danish Wikipedia article on Frederiksted "Frederiksted is a town on St Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands which were previously the Danish West Indies. .. The town is dominated by the red and white Fort Frederik from the 1750s. The fort has special meaning to both USA and Denmark-Norway. It was from here that the first foreign salute of recognition of USA independence was given in 1776."

References

[edit]- ^ "Benoeming regeringscommissaris en plaatsvervanger Sint Eustatius". Rijksoverheid (in Dutch). 18 June 2021. Archived from the original on 28 May 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Waaruit bestaat het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden?". Rijksoverheid (in Dutch). 19 May 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Population of the Caribbean Netherlands up by nearly 1.6 thousand in 2024". 19 May 2025.

- ^ English can be used in relations with the government, see, Invoeringswet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba (in Dutch) – via Overheid.nl.

- ^ "BQ – Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba". ISO. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Delegation Record for .BQ". IANA. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Mangold, Max. Duden – Das Aussprachewörterbuch. In: Der Duden in zwölf Bänden, Band 6. 7. Auflage. Berlin: Dudenverlag; Mannheim : Institut für Deutsche Sprache, 2015, Seite 786.

- ^ a b c d e Tuchman, Barbara W. (1988). The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution. New York: Ballantine Books.

- ^ Wet openbare lichamen Bonaire, Sint Eustatius en Saba [Law on the public bodies of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba] (in Dutch) – via Overheid.nl.

- ^ "Antillen opgeheven op 10-10-2010". NOS Nieuws (in Dutch). 18 November 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ Zaken, Ministerie van Algemene (19 May 2015). "Waaruit bestaat het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden? – Rijksoverheid.nl". www.rijksoverheid.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 28 March 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jameson, J. Franklin. "St. Eustatius in the American Revolution". American Historical Review 8 (1903):683–708. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1834346

- ^ a b Attema, Y. (1976). St. Eustatius: A Short History of the Island and Its Monuments. Walburg Pers. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-6011-153-6.

- ^ De Gids. Nieuwe vaderlandsche letteroefeningen (in Dutch). Amsterdam: Stichting de Gids. 1905. p. 299.

- ^ Hartog, Johannes (1976). History of St. Eustatius. Central U.S.A. Bicentennial Committee of the Netherlands Antilles : distributors, De Witt Stores N.V.

- ^ "Archaeological Excavations at Old Gin House: Remains of a mid-18th to late 18th century domesticate area on a terrace in Lower Town, St. Eustatius, Dutch Caribbean." (2013). The St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research.

- ^ a b c Joh. Hartog, De Bovenwindse eilanden Sint Maarten – saba – Sint Eustatius. De Wit N.N. Aruba (1964), pp. 1–3.

- ^ Haviser, Jay B. Jr. (1981). An Inventory of Prehistoric Sites on St. Eustatius, Netherlands Antilles (PDF). Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "About St. Eustatius: History". Statia Government. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2023.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hartog, Johannes (1978). St. Maarten, Saba, St. Eustatius. De Wit Stores. p. 13.

- ^ "Netherlands Antilles". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 15 April 2023. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Westergaard, Waldemar (1917). The Danish West Indies Under Company Rule (1671–1754): With a Supplementary Chapter, 1755–1917. Macmillan. p. 12.

- ^ a b Aspinall, Sir Algernon Edward (1927). "St. Eustatius & Saba". The Pocket Guide to the West Indies, British Guiana, British Honduras, Bermuda, the Spanish Main, Surinam, and the Panama Canal. Sifton, Praed & Company, Limited. p. 343.

- ^ Klingelhofer, Eric (11 November 2010). "French Fortifications in the New World". First Forts: Essays on the Archaeology of Proto-colonial Fortifications. BRILL. p. 61. ISBN 978-90-04-18732-0.

- ^ Aceto, Michael (10 December 2008). "Eastern Caribbean English-derived language varieties: Phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W. (ed.). The Americas and the Caribbean. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020840-5.

- ^ Panton, Kenneth J. (7 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-8108-7524-1.

- ^ Hartog, Johannes (1976). History of St. Eustatius. Central U.S.A. Bicentennial Committee of the Netherlands Antilles : distributors, De Witt Stores N.V. p. 21.

- ^ Attema, Y. (1976). St. Eustatius: A Short History of the Island and Its Monuments. Walburg Pers. p. 16. ISBN 978-90-6011-153-6.

- ^ Klooster, Wim (19 October 2016). The Dutch Moment: War, Trade, and Settlement in the Seventeenth-Century Atlantic World. Cornell University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-5017-0667-7.

- ^ a b Emmer, Pieter C.; Gommans, Jos J. L. (15 October 2020). The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600–1800. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–179. ISBN 978-1-108-42837-8.

- ^ Inikori, Joseph E.; Engerman, Stanley L. (30 April 1992). The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe. Duke University Press. pp. 292–295. ISBN 978-0-8223-1243-7.

- ^ a b McGreevy, Nora (2 June 2021). "Remains of Enslaved People Found at Site of 18th-Century Caribbean Plantation". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "St Eustatius". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Gregory E. O'Malley and Alex Borucki, "Patterns in the intercolonial slave trade across the Americas before the nineteenth century," Tempo, 23 (May/Aug 2017): 315–338.

- ^ ENTHOVEN, VICTOR (2012). ""That Abominable Nest of Pirates": St. Eustatius and the North Americans, 1680—1780". Early American Studies. 10 (2): 239–301. ISSN 1543-4273. JSTOR 23547669.

- ^ "Discover the "Golden Rock": an island teeming with history". Statia Tourism. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ Oostindie, Gert; Roitman, Jessica V. (20 June 2014). Dutch Atlantic Connections, 1680–1800: Linking Empires, Bridging Borders. BRILL. p. 135. ISBN 978-90-04-27131-9.

- ^ Emmer, Pieter C.; Gommans, Jos J. L. (15 October 2020). The Dutch Overseas Empire, 1600–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-108-67994-7.

- ^ "[Home page]". Andrew Doria – The First Salute, Inc. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ "Jews in British America". The American Revolution. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ a b Botta, Carlo (1837). History of the War of Independence of the United States of America. N. Whiting.

- ^ Jong, Cornelius de (1807). Reize naar de Caribische Eilanden in de jaren 1780 en 1781. Haarlem. p. 179

- ^ "The British Capture of Sint Eustatius".

- ^ Gramarye, Eliza. "1725 St. Eustatius Census". Academia.

- ^ ""A Medley of Contradictions": The Jewish Diaspora in St Eustatius and Barbados" (PDF).

- ^ Miller, Derek (1 January 2013). ""A Medley of Contradictions": The Jewish Diaspora in St Eustatius and Barbados". Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. doi:10.21220/s2-c1t3-w516.

- ^ a b "Honen Dalim". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ a b "La Nacion". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ a b "St Eustatius". Jews were here. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ a b Pilgrim, Lucy (10 December 2024). "Sint Eustatius : Jewish Heritage In Focus". Outlook Travel Magazine. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ a b Norton, Louis Arthur (October 2006). "Retribution: Admiral Rodney and the Jews of St. Eustatius". Jewish Magazine. Retrieved 4 April 2022.N

- ^ West Indisch Plakaatboek. Amsterdam. 1979.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Abbattista, Guido (2008). "Edmund Burke, the Atlantic American War and the 'Poor Jews at St. Eustatius': Empire and the Law of Nations". Cromohs. 13: 1–39.

- ^ "Honen Dalim Synagogue | Sint Eustatius Sightseeing | Sint Eustatius". www.inyourpocket.com. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ "Honen Dalim". Richard Varr's Travel Blog. Retrieved 15 May 2025.

- ^ Arbell, Mordehai (2002). The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean: The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas. Jerusalem: Geffen.

- ^ "Honen Dalim Synagogue Restoration Project". St. Eustius Historical Foundation. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- ^ Paula, A. F. (1993). 'Vrije' slaven: Een sociaal-historische studie over de dualistische slavenemancipatie op Nederlands Sint Maarten, 1816–1863. Centraal Historisch Archief, Universiteit van de Nederlandse Antillen. p. 98. ISBN 90-6011-841-3.

- ^ Hartog, Joh. (1969). De Bovenwindse eilanden: Sint Maarten, Saba, Sint Eustatius (in Dutch). Aruba: De Wit N. V. pp. 296–297.

- ^ 1863 Abolition of slavery – Timeline Dutch History – Rijksstudio

- ^ "Introduction of the Dollar on Bonaire, Saint Eustace, Saba". Government of the Netherlands. 18 May 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ "Zeelandia Bay". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ van den Burg, Matthijs P; Meirmans, Patrick G; van Wagensveld, Timothy P; Kluskens, Bart; Madden, Hannah; Welch, Mark E; Breeuwer, Johannes A J (19 February 2018). "The Lesser Antillean Iguana (Iguana delicatissima) on St. Eustatius: Genetically Depauperate and Threatened by Ongoing Hybridization". Journal of Heredity. 109 (4): 426–437. doi:10.1093/jhered/esy008. eISSN 1465-7333. ISSN 0022-1503. PMID 29471487.

- ^ van den Burg, Matthijs P.; Madden, Hannah; van Wagensveld, Timothy P.; Boman, Erik (21 March 2022). "Hurricane-associated population decrease in a critically endangered long-lived reptile" (PDF). Biotropica. 54 (3): 708–720. Bibcode:2022Biotr..54..708V. doi:10.1111/btp.13087. eISSN 1744-7429. ISSN 0006-3606. S2CID 247602866.

- ^ "About Us". St. Eustatius National Parks. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Eastman, John (1996). An Archaeological Assessment of St Eustatius, Netherlands Antilles (MA thesis). College of William and Mary. doi:10.21220/s2-aq12-3j05.

- ^ "Underwater Archaeology on St. Eustatius – The Caribbean's Historic Gem". The Shipwreck Survey. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "About Us". St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Ubuntu Connected Front (17 June 2021). ""Let Our Enslaved Ancestors Rest" – Says UCF Caribbean Chair" (PDF) (Press release). Ubuntu Connected Front.

- ^ "Statia Suspends Archaeological Dig at the Airport". St. Eustatius. 14 July 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Meijer, J. H. T. (9 October 2021). [Letter from J.H.T. (Jan) Meijer] (PDF) – via Caraïbisch Uitzicht.

- ^ "Faro – Participation in Cultural Heritage –". Cultural Heritage Agency. 3 July 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Monumentenwet BES (in Dutch) – via Overheid.nl.

- ^ Heritage Act https://english.inspectie-oe.nl/publications/publication/2016/9/14/[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Reactie op verzoek commissie over de stand van zaken voortgang opgravingen vliegveld Sint Eustatius". Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 April 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Statia Heritage Research Commission Officially Installed". St. Eustatius. 22 September 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "Report of the Statia Heritage Research Commission (SHRC) for the Government of St. Eustatius, Netherlands Caribbean". St. Eustatius Government. 28 January 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ Netherlands, Statistics (19 May 2025). "Population of the Caribbean Netherlands up by nearly 1.6 thousand in 2024". Statistics Netherlands. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ^ "Practical Information". Statia Tourism. Retrieved 9 September 2025.

- ^ "English to Be Sole Language of Instruction in St Eustatian Schools". Government of the Netherlands. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ a b Statistics Netherlands (2018). Trends in the Caribbean Netherlands 2018 (PDF). The Hague: Statistics Netherlands. p. 80. ISBN 978-90-357-2238-5.

- ^ "St. Eustatius". Rijksdienst Caribisch Nederland. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ^ Bouma, Joop (3 November 2017). "Sint-Eustatius haalt nu al de helft van de stroombehoefte uit zon". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "How to get here". Statia Tourism. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "Schedules". Makana Ferry Services. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "About Us". Makana Ferry Services. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "Practical Information". Statia Tourism. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ Dijkhoff, Marta, Silvia Kowenberg, and Paul Tjon Sie Fat. Chapter 215 "The Dutch-speaking Caribbean Die niederländischsprachige Karibik." In: Sociolinguistics / Soziolinguistik. Walter de Gruyter, 1 January 2006. ISBN 3110199874, 9783110199871. Start: p. 2105. CITED: p. 2108.

- ^ "Education". St. Eustatius. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Stokkermans, Karel (29 June 2012). "Sint Eustatius – Football History". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. RSSSF. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Cruyff Courts Sint Maarten / Sint Eustatius / Saba". Windward Roads. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ "1st Cruyff Court Dutch Caribbean Futsal Championship 2007 (Aruba)". RSSSF. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Saba and St. Eustatius Compete in Softball". Pearl FM Radio – Pearl of the Caribbean. 27 June 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

Further reading

[edit]- Arbell, Mordechai (2002). The Jewish Nation of the Caribbean, The Spanish-Portuguese Jewish Settlements in the Caribbean and the Guianas. Jerusalem: Geffen Press. ISBN 978-9652292797.

- Attema, Y (1976). A Short History of St. Eustatius and its Monuments. Zutphen: Walburg Pers. ISBN 978-9060111536.

- Bernardini, P; Fierling, N, eds. (2001). The Jews and the Expansion of Europe to the West, 1450–1800. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1571811530.

- Ezratty, Harry (2002) [1997]. 500 Years in the Jewish Caribbean – The Spanish and Portuguese Jews in the West Indies. Baltimore, MD: Omni Arts. ISBN 978-0942929188.

- Hartog, J (1976). History of St. Eustatius. Central USA Bicentennial Committee of the Netherlands Antilles.

- Hearst, Ronald (1996). The Golden Rock. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press.

- Jameson, J. Franklin. "St. Eustatius in the American Revolution". American Historical Review 8 (1903):683-708. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1834346

- Morse, Jedidiah (1797). "St. Eustatius". The American Gazetteer. Boston, MA: At the presses of S. Hall, and Thomas & Andrews. OL 23272543M.

- Spinney, David (1969). Rodney. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0049200227.

- O'Shaughessy, Andrew Jackson (2013). The men who lost America: British Command during the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-78074-246-5.

- Schulte Nordholt, Jan Willem. The Dutch Republic and American Independence, trans. Herbert H. Rowen. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1982 ISBN 0807815306

- Tuchman, Babara W (1988). The First Salute. Westminster, MD: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394553337.

External links

[edit]- St. Eustatius Government

- St. Eustatius Tourist Office's homepage Archived 7 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- The website of STENAPA, the National Parks of St. Eustatius

- St. Eustatius info in Lonely Planet website

- St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research

- The Farm in St. Eustatius: Not Dead Yet

- Colorful stories from St. Eustatius's eventful history. Saba invasion Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Colorful stories from St. Eustatius's eventful history. Bermuda connection Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Retribution: Admiral Rodney and the Jews of St. Eustatius", by Louis Arthur Norton

Sint Eustatius

View on GrokipediaName and Etymology

Etymology

The name Sint Eustatius is the Dutch rendering of "Saint Eustace," honoring the third-century Christian martyr Saint Eustace (also Eustachius or Eustathius), a Roman general who converted to Christianity following a vision of Christ manifested between the antlers of a stag while hunting.[7] This designation reflects the island's adoption into Dutch nomenclature upon European settlement, aligning with the tradition of naming Caribbean territories after saints.[7] Upon Dutch colonization on April 25, 1636, by the West India Company, the island was initially termed Nieuw Zeeland ("New Zealand") by settlers originating from the Dutch province of Zeeland, evoking their homeland.[8] It was promptly renamed Sint Eustatius thereafter, supplanting the provisional toponym as the official Dutch appellation.[8] The local shorthand Statia, derived from truncating "Eustatius," emerged as a vernacular usage in West Indian contexts and persists in contemporary references.[9]Nicknames and historical designations

Sint Eustatius is commonly abbreviated and referred to locally as Statia, a nickname derived from shortening its full Dutch name and widely used by residents and visitors alike.[10][11] During the late 18th century, particularly amid its peak as a neutral free port under Dutch control from 1753 onward, the island earned the moniker the Golden Rock due to its extraordinary economic prosperity from trade, including smuggling and arms shipments to American revolutionaries, with over 10,000 vessels reportedly docking there between 1775 and 1779.[12][13] Prior to its official Dutch naming as Sint Eustatius in the 1630s, the island was initially designated Nieuw Zeeland (New Zealand) following Dutch capture from French and English settlers in 1632, reflecting early colonial naming practices inspired by European locales.[14][15]History

Pre-colonial and early European contact

Archaeological evidence from sites such as Golden Rock demonstrates that Sint Eustatius was inhabited during the pre-Columbian era by peoples of the Saladoid culture, characterized by their production of red-slipped pottery and settlement patterns dating to approximately 500 BCE to 600 CE. Excavations at Golden Rock have uncovered remnants of a late Saladoid village, including household structures and artifacts indicative of agricultural and fishing economies adapted to the island's volcanic terrain.[16] Additional findings, including the repatriation of nine indigenous skeletons in 2023 originally excavated over 30 years prior, point to the presence of Carib or Kalinago groups, likely migrants from the South American mainland, who may have occupied the island intermittently before European arrival.[17][18] The indigenous population appears to have declined or abandoned the island by the early 17th century, possibly due to inter-island conflicts, disease, or environmental pressures, leaving it uninhabited when Europeans established a sustained presence.[19] No large-scale native communities were documented at the time of Dutch settlement, though sporadic pre-colonial artifacts continue to surface in modern surveys, underscoring the island's role in broader Caribbean indigenous networks.[20] European awareness of Sint Eustatius began with its sighting by Christopher Columbus during his second voyage in 1493, though no immediate settlement followed due to the island's perceived lack of immediate resources.[10] Further reconnaissance occurred in 1595 under Sir Francis Drake, who noted its strategic position amid trade winds. The French mounted a brief occupation attempt in 1629, but it proved unsuccessful, paving the way for Dutch claims. Formal European colonization commenced in 1636 when Dutch forces under the West India Company arrived, finding the island deserted and suitable for tobacco cultivation and fortification against regional rivals.[21][20] This marked the onset of continuous European influence, transforming the uninhabited outpost into a colonial foothold.Dutch settlement and West India Company era

The chamber of Zeeland within the Dutch West India Company claimed Sint Eustatius on April 25, 1636, establishing the first permanent European settlement on an island reported as uninhabited after failed French attempts in 1629.[7] [8] The settlers prioritized defense by erecting Fort Oranje on a cliff overlooking the harbor, rebuilding upon the ruins of a rudimentary French battery from the prior occupation.[22] [11] Early colonial efforts focused on agriculture to exploit the island's fertile volcanic soil, introducing crops such as tobacco, cotton, and indigo despite challenges from limited fresh water sources, which were mitigated through the construction of cisterns.[20] The West India Company's monopoly on trade and colonization directed these activities, laying the foundation for economic development amid the broader Dutch Atlantic enterprise.[7] By 1678, the Dutch West India Company centralized authority over Sint Eustatius, Saba, and Sint Maarten, stationing a commander on Sint Eustatius to govern the trio of islands and coordinate their administration.[7] [21] This era saw the importation of enslaved Africans to bolster plantation labor for expanding sugar, tobacco, and cotton production, integrating the island into the Company's transatlantic networks.[21] The settlement grew modestly around Oranjestad, with infrastructure for housing, churches, and governance emerging on the upper cliff and lower harbor areas.[20]Free port prosperity and the Golden Rock

In 1756, the Dutch authorities abolished import duties on Sint Eustatius, establishing it as a free port to capitalize on its strategic location in the northeastern Caribbean, where trade winds converged from Europe, Africa, and the Americas.[23] [24] This policy, enacted amid mercantilist restrictions imposed by other colonial powers, allowed duty-free transshipment of goods, attracting merchants evading blockades and tariffs during conflicts like the Seven Years' War (1756–1763).[9] The island's neutrality under Dutch control further facilitated smuggling, particularly to British North American colonies seeking European manufactures and military supplies.[25] Prosperity peaked in the 1770s and early 1780s, with annual ship arrivals reaching 3,551 in 1779 and often exceeding 3,000 vessels per year, including up to 300 anchored simultaneously in the roadstead.[24] [21] Population swelled from around 1,000 in the early 18th century to nearly 9,000 permanent residents by 1790, with transients pushing totals to approximately 20,000, reflecting a boom driven by commerce rather than local agriculture.[24] Warehouses in Lower Town overflowed, generating annual rents estimated at £1,000,000, underscoring the island's transformation into a vital entrepôt.[25] Trade encompassed diverse commodities, including 25 million pounds of sugar and 12,000 hogsheads of tobacco exported in 1779, alongside 1.5 million ounces of indigo from North America, exchanged for arms, gunpowder (such as 4,000 barrels supplied in 1775), coffee, and European luxuries.[24] [25] The port also handled slave auctions and ship repairs, serving as a nexus for Atlantic networks. This economic dominance earned Sint Eustatius the moniker "Golden Rock," evoking its wealth akin to untapped gold reserves, a term contemporaries used to describe its unparalleled Caribbean commercial preeminence.[24]Role in the American Revolution and the First Salute

Sint Eustatius, as a Dutch free port, maintained nominal neutrality during the American War of Independence but served as a critical conduit for smuggling arms, ammunition, and gunpowder to the Continental forces, with estimates indicating that up to 90% of gunpowder reaching the American rebels passed through the island in the early years of the conflict.[25] Merchants on the island, leveraging its status as a entrepôt, facilitated the transshipment of European goods, including muskets and military stores, evading British blockades and contributing substantially to the revolutionary supply chain.[26] This trade, conducted under the cover of Dutch neutrality, boosted the island's economy and earned it the moniker "Golden Rock" for its commercial prosperity.[27] On November 16, 1776, the Continental Navy brigantine Andrew Doria, commanded by Captain Isaiah Robinson and flying the Grand Union flag (the first national flag of the United States), entered Oranjestad harbor and fired an 11-gun salute to the Dutch authorities as per maritime custom for warships entering neutral ports.[27] Governor Johannes de Graaff, acting on behalf of the Dutch West India Company, ordered the guns of Fort Oranje to return the salute with 11 shots, marking the first instance of a foreign power acknowledging the American flag through such a reciprocal gesture.[28] This event, later termed the "First Salute" by John Adams, was interpreted by American leaders as de facto recognition of their independence, though the Dutch government in Europe had not yet formally acknowledged it.[29] The salute provoked outrage in Britain, contributing to escalating tensions that culminated in the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War.[25] The Andrew Doria's visit was part of a broader American effort to procure supplies from Sint Eustatius, where the brig loaded gunpowder and other materiel before departing, underscoring the island's strategic importance in sustaining the revolutionary war effort against British forces.[27] Despite the risks, including British naval patrols, Statia's role persisted until its capture in 1781, with the 1776 salute symbolizing an early international validation of the American cause amid widespread European reluctance to openly support the rebellion.[30]British capture and economic devastation (1781)

British naval and army forces under Admiral George Brydges Rodney and Lieutenant-General John Vaughan captured Sint Eustatius on February 3, 1781, during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. The expedition, consisting of about 3,000 troops and a fleet with multiple ships of the line, sailed from Saint Lucia on January 30 and arrived off the island undetected in the early morning. The Dutch defenders, numbering around 60 soldiers and three small warships, offered negligible resistance; after a summons to surrender Fort Oranje, the garrison capitulated within hours, enabling the British to secure the island without major combat.[31][32] The victors seized vast spoils, including approximately 150 merchant ships anchored in the harbor, loaded with arms, gunpowder, tobacco, and other supplies intended for American revolutionaries. British troops and sailors proceeded to ransack warehouses, private residences, and commercial establishments, confiscating goods and property on a massive scale. This plunder extended to neutral traders' assets, with Admiral Rodney personally overseeing the adjudication of prizes, which delayed his fleet's redeployment for weeks amid accusations of excessive greed from contemporaries. The total value of captured commodities has been estimated in the millions of pounds sterling, reflecting the island's peak as a conduit for wartime commerce.[32][33] The occupation inflicted irreversible economic damage on Sint Eustatius, dismantling its infrastructure as a premier free port. Merchants, facing arbitrary seizures and forced expulsions, abandoned the island en masse, eroding the transient population that had sustained its "Golden Rock" moniker through handling thousands of vessels yearly. Although French forces under the Marquis de Bouillé recaptured the island on November 26, 1781, and restored Dutch sovereignty by 1784, the loss of trading networks, capital, and expertise proved insurmountable; commerce permanently shifted to rival entrepôts like Danish St. Thomas, initiating a prolonged decline that persisted into the 19th century.[33][32]Jewish economic contributions

Sephardic Jews began settling in Sint Eustatius in the mid-17th century, following Dutch control established in 1632, and established a formal congregation known as Honen Dalim by 1737, leading to the construction of a synagogue in 1739.[34][35] By 1750, the Jewish population numbered approximately 450 individuals among 802 free inhabitants, comprising a significant portion of the merchant class engaged in transatlantic trade.[33] These merchants, often owning ships and employing Jewish captains, facilitated commerce with Europe, North Africa, and the Americas, handling commodities such as sugar— with 25 million pounds exported in 1779 alone—along with foodstuffs, timber, and munitions.[35][36] The declaration of Sint Eustatius as a free port in 1757 accelerated Jewish immigration and economic activity, with annual ship arrivals reaching 1,800 to 2,700 by 1760 and exceeding 3,000 in 1779, many under Jewish ownership or operation.[35][33] Jewish traders formed the core of the island's commercial network, which earned Sint Eustatius the moniker "Golden Rock" for its pivotal role in circumventing colonial trade restrictions and fostering a bustling entrepôt economy.[35] Over 100 Jewish families, primarily Sephardim with some Ashkenazim, dominated the export-import sector, leveraging familial and communal ties across ports to sustain high-volume, duty-free exchanges.[35] During the American Revolution from 1776 to 1781, Jewish merchants disproportionately supplied arms, gunpowder, food, and other materiel to the Continental forces, with instances such as 18 ships delivering goods in May 1776 alone, bolstering the island's trade volume and underscoring their integral contribution to Sint Eustatius's wartime prosperity.[33][35] Agents like Samson Mears, representing figures such as Aaron Lopez, coordinated these shipments, enabling the island to serve as a critical nexus for revolutionary logistics despite Dutch neutrality.[35] This activity not only amplified economic output but also positioned Jewish networks as essential to the broader Atlantic financial interconnections that defined the era's colonial capitalism.[37]Slave-based economy, revolt, and emancipation

The economy of Sint Eustatius relied heavily on enslaved labor from the mid-17th century onward, supporting both agricultural production and the island's role as a transatlantic trade hub. Enslaved Africans worked on small-scale plantations cultivating sugar, cotton, tobacco, and provisions, with archaeological evidence indicating residential structures and hearths associated with slave quarters on sites like English Quarter plantation.[38] Slaves also provided labor for port activities, including loading and unloading goods, as the island's free port status facilitated commerce in commodities that included human cargoes from the transatlantic slave trade.[21] By the late 18th century, enslaved individuals formed the majority of the island's population, though exact figures varied; the slave population declined from the 1840s amid natural decrease and limited imports following Dutch prohibitions on the trade.[39] Tensions culminated in a slave revolt on June 12, 1848, at Green and White Cove near Fort Oranje, where enslaved people, led by free Black man Thomas Dupersoy and five enslaved leaders—Abraham, Joseph, Prince, Oscar, and Valentine—demanded immediate freedom inspired by recent emancipations in neighboring French and Danish colonies.[40] The uprising involved armed resistance against planters, resulting in executions of some participants, but it highlighted the precarious control of colonial authorities and pressured Dutch officials to accelerate abolition discussions.[41] This event, though suppressed, underscored the slaves' agency and the broader regional momentum toward emancipation, with one leader later documented as surviving to witness full abolition.[42] Slavery was formally abolished across Dutch Caribbean colonies, including Sint Eustatius, on July 1, 1863, following the Emancipation Act, with the proclamation read on the island on October 21, 1862.[43] Planters received compensation of 200 guilders per able-bodied slave, though this varied slightly in adjacent territories; freed individuals gained legal liberty but no reparations or land allocations, leading many to migrate to Oranjestad for wage labor while plantations languished due to labor shortages.[39] The transition exacerbated economic decline, as formerly enslaved people adopted survival strategies amid persistent poverty, with the slave population having already contracted sharply before 1863 due to low birth rates, disease, and flight attempts.[44]19th-20th century decline and modernization

Following the devastation of the British capture in 1781 and subsequent return to Dutch control, Sint Eustatius experienced a prolonged economic decline beginning in the early 19th century, driven by the loss of its free port status, shifting global trade patterns, and the abolition of slavery in 1863.[45][46] Trade, once the island's mainstay, dwindled as competing ports in the Caribbean and Europe captured former markets, reducing Oranjestad from a bustling hub to a quiet settlement with decaying warehouses and plantations.[47] Small-scale agriculture, including bay rum distillation and aloe cultivation, provided limited subsistence, but could not offset the broader stagnation.[48] Population figures reflected this downturn; from a peak of over 20,000 in the late 18th century, numbers fell sharply after 1795 due to emigration, warfare, and economic hardship, reaching just 921 residents by 1948.[49] Urban decay persisted through the mid-20th century, with Oranjestad's infrastructure crumbling and the island integrated into the Netherlands Antilles in 1954 without significant revival, as global shipping routes bypassed its location.[47][50] Modernization accelerated in the late 20th century with the establishment of an oil transshipment terminal in 1982, featuring 67 storage tanks with a capacity exceeding 13 million barrels, transforming the island's economy from agrarian decline to a logistics hub for petroleum products.[51] The facility, initially operated by independent entities and later acquired by NuStar Energy in 2005 and Prostar Capital in 2019 (rebranded GTI Statia), leveraged Sint Eustatius's deep-water harbor for blending, storage, and bunkering, injecting revenue and employment into the local economy.[51][52] This development marked a shift from isolation to integration in international energy supply chains, though it also introduced environmental pressures on the small island's marine ecosystem.[53]Integration into the Kingdom and recent political changes

On 10 October 2010, the Netherlands Antilles was dissolved as part of a constitutional restructuring of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with Sint Eustatius transitioning from an island territory within the Antilles to a special municipality (bijzondere gemeente) directly incorporated into the Netherlands, alongside Bonaire and Saba.[54][55] This status endowed Sint Eustatius with the public body framework, subjecting it to Dutch national legislation in areas such as taxation, social security, and public administration, while retaining a local Island Council of five elected members responsible for island-specific policies and an appointed Island Commissioner as executive head.[56] The change aligned with earlier preferences expressed by Sint Eustatius residents for closer ties to the Netherlands, though implementation proceeded amid broader Kingdom negotiations despite a 2000 referendum where the island had initially favored remaining within the Antilles structure.[57] Post-integration governance faced challenges, including fiscal mismanagement and conflicts between local officials and Dutch oversight authorities. In February 2018, the Kingdom Representative for the public entities dismissed the Island Council and Board of Commissioners, citing violations of principles of good administration, such as improper financial practices and failure to adhere to Dutch integrity standards; a temporary committee was appointed to restore order until elections could be held.[58] This intervention marked a rare direct federal override, reflecting tensions over local autonomy versus national accountability in the BES framework. Island Council elections in October 2020 and March 2023 subsequently reinstated elected bodies, with the 2023 vote yielding a council comprising members from parties including the Progressive Labour Party and Democratic Party, focusing on local priorities like infrastructure and education amid ongoing adaptation to Dutch regulatory standards.[59] Recent developments through 2025 have emphasized stabilization and policy alignment, including participation in Dutch Second Chamber elections and local decisions such as the August 2025 Island Council vote to dismiss and replace the GVP School Board due to performance issues, signaling continued emphasis on administrative reform.[60] These changes have integrated Sint Eustatius more firmly into the Kingdom's administrative orbit, with Dutch funding supporting sectors like renewable energy and disaster resilience, though local discourse persists on balancing federal oversight with island-specific needs.[61]Geography

Location and physical features

Sint Eustatius lies in the northeastern Caribbean Sea within the Leeward Islands of the Lesser Antilles, positioned approximately 26 km southeast of Saba and 8 km northwest of Saint Kitts. The island's central coordinates are roughly 17°29′ N, 62°59′ W.[62] As part of the volcanic island arc extending from the Virgin Islands southward, it forms one of the inner arc islands influenced by subduction zone tectonics.[63] The island spans 21 km², measuring about 10 km in length and up to 5 km in width, with a saddle-shaped topography dominated by volcanic features.[64] Its highest elevation is 601 m at the summit of The Quill, a large andesitic stratovolcano occupying the southeastern portion.[63] The Quill features a steep-sided crater 760 m wide and exceeding 300 m in depth, breached by a notch on the western rim that has channeled past pyroclastic flows.[65] This dormant volcano, last active around 1,600 years ago, rises symmetrically from sea level, with slopes blanketed in pyroclastic deposits including limestone fragments from its formation on a submerged bank 32,000–22,000 years ago.[66] The northern half of Sint Eustatius consists of lower hills, including Signal Hill at about 130 m, and coastal cliffs where Oranjestad is situated, overlooking anchorages and beaches formed by wave erosion on volcanic rocks.[64] Submarine extensions and fringing reefs contribute to the island's physical outline, while inland areas exhibit rugged terrain dissected by gullies and supporting limited arable land due to steep gradients and thin soils.[63]Climate patterns

Sint Eustatius exhibits a tropical savanna climate (Köppen classification Aw) with minimal seasonal temperature variation due to its equatorial proximity and oceanic influences. Average daytime highs range from 28°C in January to 31°C from June to October, while nighttime lows vary between 22°C in the cooler months of January and February and 25°C during the warmer period from June to September.[67] Annual mean temperatures hover around 27-28°C, rarely dropping below 24°C or exceeding 32°C, moderated by consistent northeast trade winds averaging 15-20 mph (24-32 km/h), which are strongest from December to August.[68] Humidity remains oppressively high year-round, with conditions described as muggy 100% of the time, contributing to a perceived temperature often above actual readings.[68] Precipitation totals approximately 1,000-1,100 mm annually, with a pronounced wet season from September to December accounting for the majority of rainfall—peaking at around 139 mm in September and accompanied by 18-20 rainy days per month in October and November.[69] [67] The dry season spans January to August, with the lowest totals in February-March (36-42 mm) and fewer than 15 rainy days monthly, though brief showers can occur. Cloud cover is lowest in January (about 49% clear skies) and highest in October (77% overcast), aligning with the shift to wetter conditions.[68] The island lies within the Atlantic hurricane belt, exposing it to tropical storms and cyclones during the official season from June 1 to November 30, with peak activity from August to October. Historical events, such as Hurricanes Irma and Maria in 2017, have demonstrated vulnerability through heavy rains, high winds, and storm surges, despite no direct hits on Sint Eustatius in recent decades; such extremes can exacerbate erosion and flooding on its volcanic terrain.[70] [71] Prevailing easterly winds generally mitigate heat but can intensify during disturbances, underscoring the need for resilient infrastructure amid projected increases in storm intensity from climate variability.Natural environment and geology

Sint Eustatius is a volcanic arc island characterized by explosive volcanism, primarily from the Quill stratovolcano at its southeastern end. The Quill, a dominantly andesitic stratovolcano reaching 601 meters in height, formed between 22,000 and 32,000 years ago. Its steep-sided summit crater measures 760 meters wide and exceeds 300 meters in depth, now overgrown with tropical rainforest. Pyroclastic deposits rich in limestone fragments indicate eruptions through a submerged limestone substrate, shaped further by tectonic uplift and marine erosion.[65] The Quill's eruption history includes events dated to approximately 6140 BC (VEI 4), 550 BC, and 250 AD, with the most recent confirmed activity around 1,600 years ago involving pyroclastic flows; no eruptions have occurred in historical records. The island's geology reflects a young central-vent structure composed largely of Pelean-, St. Vincent-, and Plinian-style pyroclastic materials.[65] The natural environment encompasses diverse tropical habitats driven by the island's volcanic topography and microclimates, ranging from cloud and rainforests atop the Quill to dry tropical forests, xeric shrublands, and coastal zones covering about 900 hectares of degraded dry forest. Vegetation is mostly secondary and pioneer-stage, featuring evergreen forests, deciduous shrublands, and open woodlands with tree densities of 3 to 82 per 25x25 meter plot and species richness up to 17 trees per plot; invasive plants like Corallita compete with natives such as cacti and orchids.[72][73] Terrestrial fauna includes 54 bird species, reptiles such as the endangered Lesser Antillean iguana impacted by invasive green iguanas, and endemics threatened by predators like rats and cats. Marine biodiversity features coral reefs (fringing, patch, and drop-off types), seagrass beds (120 hectares), and species including three sea turtle types, queen conch, reef sharks, lobsters, and groupers, though overfishing affects some populations. Conservation efforts by St. Eustatius National Parks (STENAPA) protect 33 km² across the Quill/Boven terrestrial park and the national marine park, addressing threats from invasives, grazing cattle (1.07 per hectare), pollution, and climate-driven coral bleaching.[72][74]Archaeology and Cultural Heritage

Terrestrial archaeological sites

Terrestrial archaeological investigations on Sint Eustatius have revealed evidence of both pre-Columbian indigenous occupation and extensive colonial-era remains, particularly from the 17th to 19th centuries. The island's central location in the Lesser Antilles and its volcanic terrain have preserved middens, structures, and artifacts, though erosion and modern development pose ongoing threats. Key work is conducted by the St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research (SECAR), which documents and excavates terrestrial sites in collaboration with institutions like Leiden University.[75][76] Pre-Columbian sites primarily date to the Saladoid period (circa 500 BCE to 545 CE), characterized by ceramic production, shellfish exploitation, and village settlements. The Golden Rock site, located in the island's center near the airport, represents a late Saladoid village with posthole structures, pottery sherds, and jadeitite celts indicating trade networks extending to mainland South America.[76][77] Excavations in the 1980s and later revealed a central plaza with burials, typical of Saladoid patterns, alongside evidence of resource processing like shellfish middens.[76] Other sites include Corre Corre Bay, yielding Saladoid pottery and Cittarium pica shells suggesting localized exploitation possibly linked to Golden Rock inhabitants, and Smith Gut, with shell, flint, and stone artifacts exposed by erosion.[76] Colonial terrestrial archaeology centers on plantation landscapes and associated enslaved labor sites, reflecting the island's peak as a trade hub in the 18th century. Sugar plantations such as English Quarter (occupying 303 hectares on the Atlantic side from the late 17th century) and Schotsenhoek have been excavated, uncovering estate structures, slave quarters, and industrial features like boiling houses tied to tobacco, sugar, and cotton production.[78] Enslaved African burial grounds form a significant subset, with Golden Rock yielding 48 skeletons (mostly adult males, some women and infants) from the mid-18th century, interred in unmarked graves amid plantation decline.[79] The Godet site on the southeast coast similarly documents enslaved burials, both recognized in 2024 by UNESCO's Routes of Enslaved Peoples project for their role in tracing transatlantic forced migration.[80] These findings underscore the spatial integration of residential, productive, and funerary zones on plantations, often threatened by infrastructure like airport expansions.[76]Underwater archaeology and shipwrecks

The waters surrounding Sint Eustatius harbor a concentration of 18th-century maritime artifacts and shipwreck remains, reflecting the island's peak as a free-trade entrepôt where 1,800 to 3,551 ships arrived annually from 1760 to 1779, with up to 200 vessels anchored simultaneously in Oranje Bay's roadstead spanning approximately 4.2 square kilometers at depths of 9 to 15 fathoms.[24] Historical losses stemmed from frequent hurricanes—such as 18 ships wrecked in 1733, 7 near Boven Hill in 1780, and 5 in 1792—and conflicts, including the 1758 wreck of the Duke Compagni (with salvaged silver coins) and the 1781 British raid under Admiral Rodney, which captured or scuttled dozens of vessels while halting trade.[24] Documentary evidence suggests five confirmed wrecks in the roadstead, with dozens to hundreds more probable over four centuries of intense activity, particularly during the August-to-October hurricane season.[24] Underwater surveys since the 1980s have mapped key sites using magnetometer, multibeam sonar, side-scan sonar, and SCUBA dives. Early efforts identified SE-501, SE-502, SE-504, and SE-505 as potential wreck clusters in the harbor.[24] The 2014–2015 campaign documented 41 anchors (90% clustered near reefs), ballast piles, submerged ceramics, and cannons across sites like SE-510 and SE-511 through 97 dives and geophysical scanning.[24] Notable among these is the Blue Bead Wreck at Gallows Bay (15–17 meters depth), featuring thousands of WIIf*(d)-type glass beads traded in the slave economy, alongside ceramics, glass bottles, ballast bricks, and a possible swivel gun; the site, likely a Dutch or French slaver, has been heavily looted for decades.[24] The SE-504 site, known as Triple Wreck (named for three visible anchors and exposed by 2017 hurricanes Irma and Maria), consists not of a single hull but a conglomerate of 18th-century flotsam, jetsam, lost anchors, and debris assessed by the St. Eustatius Center for Archaeological Research (SECAR) and field schools from The Shipwreck Survey, which mapped the area and recovered dozens of artifacts for conservation.[81][82] Other documented features include the Twelve Guns site (8–17 cannons), Kay Bay's isolated cannon (designated 1001), and the Twin Sisters anchor; these scatters in Oranje Bay and adjacent areas like Jenkins Bay and Tumble Down Dick Bay underscore patterns of anchor loss and cargo dispersal rather than intact wrecks.[24] Recreational and research diving, protected within the island's marine park, accesses archaeological sites such as Double Wreck, Triple Wreck, and the intentionally sunk Charles L. Brown (a 20th-century freighter at 30 meters), yielding insights into trade goods like "Statia blue beads" used as currency.[83][84]Demographics

Population dynamics and trends

The population of Sint Eustatius has remained small and fluctuated modestly around 3,000 to 3,900 residents since the island's integration as a special municipality of the Netherlands in 2010, reflecting a balance between positive natural increase and variable net migration.[85] On 1 January 2025, the population stood at 3,270, marking a 2 percent increase of 66 persons from the 3,204 recorded on 1 January 2024.[86] This recent uptick contrasts with a decade-long decline from 3,611 in 2011 to 3,142 in 2021, driven primarily by net emigration and adjustments in population registers, including the departure of U.S.-born residents.[87] Natural population growth has consistently been positive, albeit limited by the island's scale, with annual live births ranging from 33 to 50 and deaths from 11 to 21 over the 2011–2024 period.[85] For instance, in 2024, 40 births and 21 deaths yielded a natural increase of 19 persons.[86] Migration patterns have been the dominant factor in fluctuations: net inflows reached +110 in 2011 but plunged to -704 in 2015 amid high emigration (849 departures), before stabilizing near zero or slightly positive, as in +38 net migrants in 2024 with 167 arrivals and 129 departures.[85] Inflows often originate from nearby Caribbean islands like Sint Maarten or the Dominican Republic, while outflows reflect economic opportunities elsewhere.[87]| Year (1 Jan) | Population | Natural Increase | Net Migration | Total Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 3,611 | +20 | +110 | +181 |

| 2015 | 3,877 | +25 | -704 | -684 |

| 2020 | 3,139 | +34 | -31 | +3 |

| 2024 | 3,204 | +19 | +38 | +66 |