Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Recorded history

View on WikipediaThe examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (November 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world history, recorded history begins with the accounts of the ancient world around the 4th millennium BCE, and it coincides with the invention of writing.

For some geographic regions or cultures, written history is limited to a relatively recent period in human history because of the limited use of written records. Moreover, human cultures do not always record all of the information which is considered relevant by later historians, such as the full impact of natural disasters or the names of individuals. Recorded history for particular types of information is therefore limited based on the types of records kept. Because of this, recorded history in different contexts may refer to different periods of time depending on the topic.

The interpretation of recorded history often relies on historical method, or the set of techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write accounts of the past. The question of what constitutes history, and whether there is an effective method for interpreting recorded history, is raised in the philosophy of history as a question of epistemology. The study of different historical methods is known as historiography, which focuses on examining how different interpreters of recorded history create different interpretations of historical evidence.

Prehistory

[edit]Prehistory traditionally refers to the span of time before recorded history, ending with the invention of writing systems.[1] Prehistory refers to the past in an area where no written records exist, or where the writing of a culture is not understood.

Protohistory refers to the transition period between prehistory and history, after the advent of literacy in a society but before the writings of the first historians. Protohistory may also refer to the period during which a culture or civilization has not yet developed writing, but other cultures have noted its existence in their own writings.

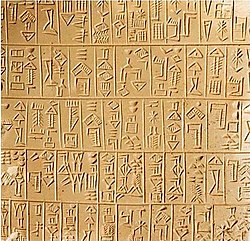

More complete writing systems were preceded by proto-writing. Early examples are the Jiahu symbols (c. 6600 BCE), Vinča signs (c. 5300 BCE), early Indus script (c. 3500 BCE) and Nsibidi script (c. before 500 CE). There is disagreement concerning exactly when prehistory becomes history, and when proto-writing became "true writing".[2] However, invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age in the late Neolithic of the late 4th millennium BCE. The Sumerian archaic cuneiform script and the Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally considered the earliest writing systems, both emerging out of their ancestral proto-literate symbol systems from 3400 to 3200 BCE, with earliest coherent texts from about 2600 BCE.

Historical accounts

[edit]The earliest chronologies date back to the earliest civilizations of Early Dynastic Period of Egypt, Mesopotamia and the Sumerians,[3] which emerged independently of each other from roughly 3500 BCE.[4] Earliest recorded history, which varies greatly in quality and reliability, deals with Pharaohs and their reigns, as preserved by ancient Egyptians.[5] Much of the earliest recorded history was re-discovered relatively recently due to archaeological dig sites findings.[6] A number of different traditions have developed in different parts of the world as to how to interpret these ancient accounts.

Europe

[edit]Dionysius of Halicarnassus knew of seven predecessors of Herodotus, including Hellanicus of Lesbos, Xanthus of Lydia and Hecataeus of Miletus. He described their works as simple, unadorned accounts of their own and other cities and people, Greek or foreign, including popular legends.

Herodotus (484 BCE – c. 425 BCE)[7] has generally been acclaimed as the "father of history" composing his The Histories from the 450s to the 420s BCE. However, his contemporary Thucydides (c. 460 BCE – c. 400 BCE) is credited[by whom?] with having first approached history with a well-developed historical method in his work the History of the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides, unlike Herodotus, regarded history as being the product of the choices and actions of human beings, and looked at cause and effect, rather than as the result of divine intervention.[7] History developed as a popular form of literature in later Greek and Roman societies in the works of Polybius, Tacitus and others.

Saint Augustine was influential in Christian and Western thought at the beginning of the medieval period. Through the Medieval and Renaissance periods, history was often studied through a sacred or religious perspective. Around 1800, German philosopher and historian Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel brought philosophy and a more secular approach into historical study.[8]

According to John Tosh, "From the High Middle Ages (c.1000–1300) onwards, the written word survives in greater abundance than any other source for Western history."[9] Western historians developed methods comparable to modern historiographic research in the 17th and 18th centuries, especially in France and Germany, where they began investigating these source materials to write histories of their past. Many of these histories had strong ideological and political ties to their historical narratives. In the 20th century, academic historians began focusing less on epic nationalistic narratives, which often tended to glorify the nation or great men, to attempt more objective and complex analyses of social and intellectual forces. A major trend of historical methodology in the 20th century was a tendency to treat history more as a social science rather than as an art, which traditionally had been the case. French historians associated with the Annales School introduced quantitative history, using raw data to track the lives of typical individuals, and were prominent in the establishment of cultural history.

East Asia

[edit]The Zuo Zhuan, attributed to Zuo Qiuming in the 5th century BCE, covers the period from 722 to 468 BCE in a narrative form. The Book of Documents is one of the Five Classics of Chinese classic texts and one of the earliest narratives of China. The Spring and Autumn Annals, the official chronicle of the State of Lu covering the period from 722 to 481 BCE, is arranged on annalistic principles. It is traditionally attributed to Confucius (551–479 BCE). Zhan Guo Ce was a renowned ancient Chinese historical compilation of sporadic materials on the Warring States period compiled between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE.

Sima Qian (around 100 BCE) was the first in China to lay the groundwork for professional historical writing. His written work was the Records of the Grand Historian, a monumental lifelong achievement in literature. Its scope extends as far back as the 16th century BCE, and it includes many treatises on specific subjects and individual biographies of prominent people, and also explores the lives and deeds of commoners, both contemporary and those of previous eras. His work influenced every subsequent author of history in China, including the prestigious Ban family of the Eastern Han dynasty era.

South Asia

[edit]In Sri Lanka, the oldest historical text is the Mahavamsa (c. 5th century CE). Buddhist monks of the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya maintained chronicles of Sri Lankan history starting from the 3rd century BCE. These annals were combined and compiled into a single document in the 5th century by the Mahanama of Anuradhapura while Dhatusena of Anuradhapura was ruling the Anuradhapura Kingdom. It was written based on prior ancient compilations known as the Atthakatha, which were commentaries written in Sinhala.[10][page needed] An earlier document known as the Dipavamsa (4th century CE) "Island Chronicles" is much simpler and contains less information than the Mahavamsa and was probably compiled using the Atthakatha on the Mahavamsa as well.

A companion volume, the Culavamsa "Lesser Chronicle", compiled by Sinhala monks, covers the period from the 4th century to the British takeover of Sri Lanka in 1815. The Culavamsa was compiled by a number of authors of different time periods.

The combined work, sometimes referred to collectively as the Mahavamsa, provides a continuous historical record of over two millennia, and is considered one of the world's longest unbroken historical accounts.[11] It is one of the few documents containing material relating to the Nāga and Yakkha peoples, indigenous inhabitants of Lanka prior to the legendary arrival of Prince Vijaya from Singha Pura of Kalinga.

The Sangam literature offers a window into some aspects of the ancient South Indian culture, secular and religious beliefs, and the people. For example, in the Sangam era Ainkurunuru poem 202 is one of the earliest mentions of "pigtail of Brahmin boys".[12] These poems also allude to historical incidents, ancient Tamil kings, the effect of war on loved ones and households.[13] The Pattinappalai poem in the Ten Idylls group, for example, paints a description of the Chola capital, the king Karikala, the life in a harbor city with ships and merchandise for seafaring trade, the dance troupes, the bards and artists, the worship of the Hindu god Murugan and the monasteries of Buddhism and Jainism.

Indica is an account of Mauryan India by the Greek writer Megasthenes. The original book is now lost, but its fragments have survived in later Greek and Latin works. The earliest of these works are those by Diodorus Siculus, Strabo (Geographica), Pliny, and Arrian (Indica).[14][15]

West Asia

[edit]In the preface to his book, the Muqaddimah (1377), the Arab historian and early sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, warned of seven mistakes that he thought that historians regularly committed. In this criticism, he approached the past as strange and in need of interpretation. Ibn Khaldun often criticised "idle superstition and uncritical acceptance of historical data." As a result, he introduced a scientific method to the study of history, and he often referred to it as his "new science".[16] His historical method also laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of state, communication, propaganda and systematic bias in history,[17] and he is thus considered to be the "father of historiography"[18][19] or the "father of the philosophy of history".[20]

Methods of recording history

[edit]While recorded history begins with the invention of writing, over time new ways of recording history have come along with the advancement of technology. History can now be recorded through photography, audio recordings, and video recordings. More recently, Internet archives have been saving copies of webpages, documenting the history of the Internet. Other methods of collecting historical information have also accompanied the change in technologies; for example, since at least the 20th century, attempts have been made to preserve oral history by recording it. Until the 2000s this was done using analogue recording methods such as cassettes and reel-to-reel tapes. With the onset of new technologies, there are now digital recordings, which may be recorded to compact disks.[21] Nevertheless, historical record and interpretation often relies heavily on written records, partially because it dominates the extant historical materials, and partially because historians are used to communicating and researching in that medium.[22]

Historical method

[edit]The historical method comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historians use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write history. Primary sources are first-hand evidence of history (usually written, but sometimes captured in other mediums) made at the time of an event by a present person. Historians think of those sources as the closest to the origin of the information or idea under study.[23][24] These types of sources can provide researchers with, as Dalton and Charnigo put it, "direct, unmediated information about the object of study."[25]

Historians use other types of sources to understand history as well. Secondary sources are written accounts of history based upon the evidence from primary sources. These are sources which, usually, are accounts, works, or research that analyse, assimilate, evaluate, interpret, and/or synthesize primary sources. Tertiary sources are compilations based upon primary and secondary sources and often tell a more generalized account built on the more specific research found in the first two types of sources.[23][26][27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Shotwell, James Thomson. An Introduction to the History of History. Records of civilization, sources and studies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1922.

- ^ Smail, Daniel Lord. On Deep History and the Brain. An Ahmanson foundation book in the humanities. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- ^ "The Cuneiform Writing System in Ancient Mesopotamia: Emergence and Evolution". EDSITEment. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Kott, Ruth E. "The origins of writing". The University of Chicago Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Adès, Harry (2007). A Traveller's History of Egypt. Interlink Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-1566566544.

- ^ Greer, Thomas H. (2004). A Brief History of the Western World. Cengage Learning. p. 16. ISBN 978-0534642365.

- ^ a b Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. & Jeremy A. Sabloff (1979). Ancient Civilizations: The Near East and Mesoamerica. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 0-88133-834-6.

- ^ Graham, Gordon (1997). "Chapter 1". The Shape of the Past. Oxford University.

- ^ Tosh, The Pursuit of History, 90.

- ^ Oldenberg 1879.

- ^ Tripāṭhī, Śrīdhara, ed. (2008). Encyclopaedia of Pali Literature: The Pali canon. Vol. 1. Anmol. p. 117. ISBN 9788126135608.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil 1992, p. 51.

- ^ Kamil Zvelebil (1992). Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. BRILL Academic. pp. 51–56. ISBN 90-04-09365-6. Archived from the original on 29 March 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Pearson Education India. p. 324. ISBN 9788131711200. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

- ^ Christopher I. Beckwith (2015). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9781400866328. Archived from the original on 1 May 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N. J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, p. x, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01754-9.

- ^ H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Journal 1.

- ^ Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9.

- ^ Enan, Muhammed Abdullah (2007). Ibn Khaldun: His Life and Works. The Other Press. p. v. ISBN 978-983-9541-53-3.

- ^ Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3).

- ^ Colin Webb; Kevin Bradley (1997). "Preserving Oral History Recordings". National Library of Australia. Archived from the original on 19 June 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- ^ Tosh, The Pursuit of History 58-59

- ^ a b Cleary, Laura. "Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources". University of Maryland Libraries. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Library Guides: Primary, secondary and tertiary sources" Archived 12 February 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dalton, Margaret Steig; Charnigo, Laurie (September 2004). "Historians and Their Information Sources". College & Research Libraries: 416 n.3. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2020., citing U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2003), Occupational Outlook Handbook; Lorenz, Chris (2001). "History: Theories and Methods". In Neil J. Smelser; Paul B. Bates (eds.). International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences. Vol. 10. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 6871.

- ^ "Glossary, Using Information Resources". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. ("Tertiary Source" is defined as "reference material that synthesizes work already reported in primary or secondary sources")

- ^ "Library Guides: Primary, secondary and tertiary sources". Archived from the original on 12 February 2005.

Sources

[edit]- Works cited

- Oldenberg, Hermann (1879). Dipavamsa. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-0217-5.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Tosh, John (2006). The Pursuit of History (4th ed.). Pearson Longamn. ISBN 9781405823517.