Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

3D printing

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

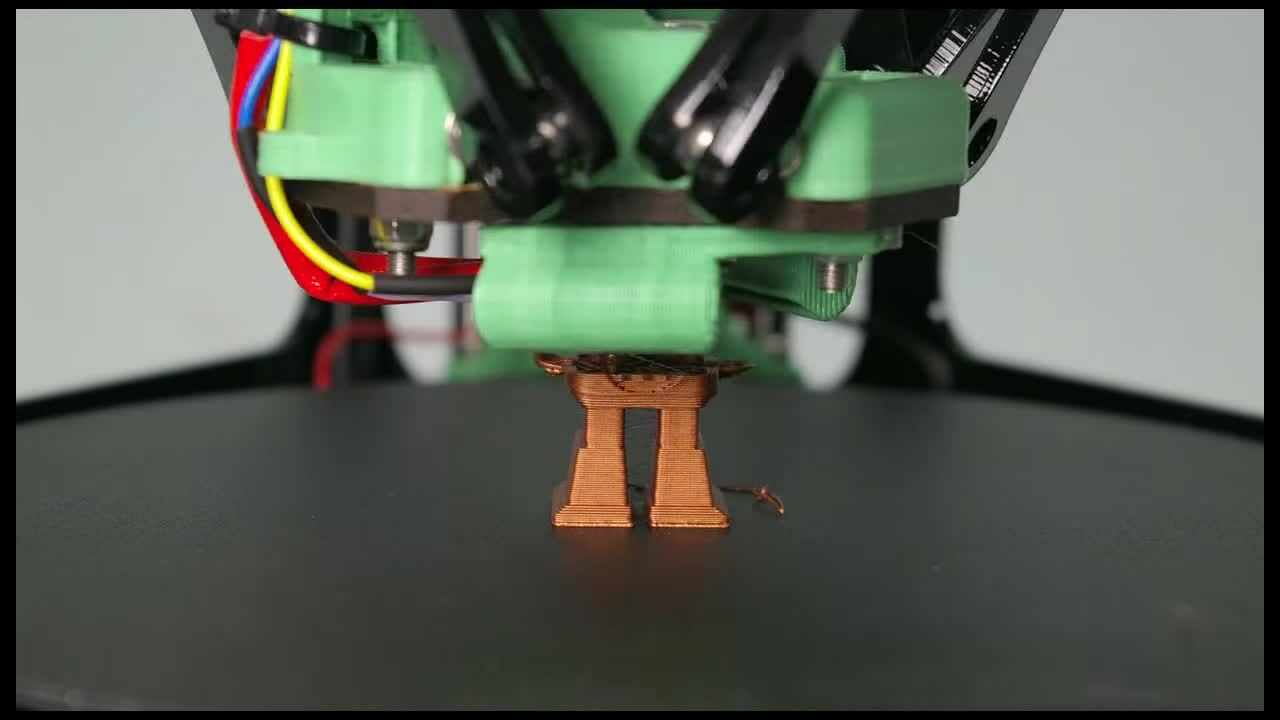

3D printing, also called additive manufacturing, is the construction of a three-dimensional object from a CAD model or a digital 3D model.[1][2][3] It can be done in a variety of processes in which material is deposited, joined or solidified under computer control,[4] with the material being added together (e.g. plastics, liquids, or powder grains being fused), typically layer by layer.

In the 1980s, 3D printing techniques were considered suitable only for the production of functional or aesthetic prototypes, and a more appropriate term for it at the time was rapid prototyping.[5] As of 2019[update], the precision, repeatability, and material range of 3D printing have increased to the point that some 3D printing processes are considered viable as an industrial-production technology; in this context, the term additive manufacturing can be used synonymously with 3D printing.[6] One of the key advantages of 3D printing[7] is the ability to produce very complex shapes or geometries that would be otherwise infeasible to construct by hand, including hollow parts or parts with internal truss structures to reduce weight while creating less material waste. Fused deposition modeling (FDM), which uses a continuous filament of a thermoplastic material, is the most common 3D printing process in use as of 2020[update].[8]

Terminology

[edit]The umbrella term additive manufacturing (AM) gained popularity in the 2000s,[9] inspired by the theme of material being added together (in any of various ways). In contrast, the term subtractive manufacturing appeared as a retronym for the large family of machining processes with material removal as their common process. The term 3D printing still referred only to the polymer technologies in most minds, and the term AM was more likely to be used in metalworking and end-use part production contexts than among polymer, inkjet, or stereolithography enthusiasts.

By the early 2010s, the terms 3D printing and additive manufacturing evolved senses in which they were alternate umbrella terms for additive technologies, one being used in popular language by consumer-maker communities and the media, and the other used more formally by industrial end-use part producers, machine manufacturers, and global technical standards organizations. Until recently, the term 3D printing has been associated with machines low in price or capability.[10] 3D printing and additive manufacturing reflect that the technologies share the theme of material addition or joining throughout a 3D work envelope under automated control. Peter Zelinski, the editor-in-chief of Additive Manufacturing magazine, pointed out in 2017 that the terms are still often synonymous in casual usage,[11] but some manufacturing industry experts are trying to make a distinction whereby additive manufacturing comprises 3D printing plus other technologies or other aspects of a manufacturing process.[11]

Other terms that have been used as synonyms or hypernyms have included desktop manufacturing, rapid manufacturing (as the logical production-level successor to rapid prototyping), and on-demand manufacturing (which echoes on-demand printing in the 2D sense of printing). The fact that the application of the adjectives rapid and on-demand to the noun manufacturing was novel in the 2000s reveals the long-prevailing mental model of the previous industrial era during which almost all production manufacturing had involved long lead times for laborious tooling development. Today, the term subtractive has not replaced the term machining, instead complementing it when a term that covers any removal method is needed. Agile tooling is the use of modular means to design tooling that is produced by additive manufacturing or 3D printing methods to enable quick prototyping and responses to tooling and fixture needs. Agile tooling uses a cost-effective and high-quality method to quickly respond to customer and market needs, and it can be used in hydroforming, stamping, injection molding and other manufacturing processes.

History

[edit]1940s and 1950s

[edit]The general concept of and procedure to be used in 3D-printing was first described by Murray Leinster in his 1945 short story "Things Pass By": "But this constructor is both efficient and flexible. I feed magnetronic plastics — the stuff they make houses and ships of nowadays — into this moving arm. It makes drawings in the air following drawings it scans with photo-cells. But plastic comes out of the end of the drawing arm and hardens as it comes ... following drawings only"[12]

It was also described by Raymond F. Jones in his story, "Tools of the Trade", published in the November 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine. He referred to it as a "molecular spray" in that story.

1970s

[edit]In 1971, Johannes F Gottwald patented the Liquid Metal Recorder, U.S. patent 3596285A,[13] a continuous inkjet metal material device to form a removable metal fabrication on a reusable surface for immediate use or salvaged for printing again by remelting. This appears to be the first patent describing 3D printing with rapid prototyping and controlled on-demand manufacturing of patterns.

The patent states:

As used herein the term printing is not intended in a limited sense but includes writing or other symbols, character or pattern formation with an ink. The term ink as used in is intended to include not only dye or pigment-containing materials, but any flowable substance or composition suited for application to the surface for forming symbols, characters, or patterns of intelligence by marking. The preferred ink is of a hot melt type. The range of commercially available ink compositions which could meet the requirements of the invention are not known at the present time. However, satisfactory printing according to the invention has been achieved with the conductive metal alloy as ink.

But in terms of material requirements for such large and continuous displays, if consumed at theretofore known rates, but increased in proportion to increase in size, the high cost would severely limit any widespread enjoyment of a process or apparatus satisfying the foregoing objects.

It is therefore an additional object of the invention to minimize use to materials in a process of the indicated class.

It is a further object of the invention that materials employed in such a process be salvaged for reuse.

According to another aspect of the invention, a combination for writing and the like comprises a carrier for displaying an intelligence pattern and an arrangement for removing the pattern from the carrier.

In 1974, David E. H. Jones laid out the concept of 3D printing in his regular column Ariadne in the journal New Scientist.[14][15]

1980s

[edit]Early additive manufacturing equipment and materials were developed in the 1980s.[16]

In April 1980, Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute invented two additive methods for fabricating three-dimensional plastic models with photo-hardening thermoset polymer, where the UV exposure area is controlled by a mask pattern or a scanning fiber transmitter.[17] He filed a patent for this XYZ plotter, which was published on 10 November 1981. (JP S56-144478).[18] His research results as journal papers were published in April and November 1981.[19][20] However, there was no reaction to the series of his publications. His device was not highly evaluated in the laboratory and his boss did not show any interest. His research budget was just 60,000 yen or $545 a year. Acquiring the patent rights for the XYZ plotter was abandoned, and the project was terminated.

A US 4323756 patent, method of fabricating articles by sequential deposition, granted on 6 April 1982 to Raytheon Technologies Corp describes using hundreds or thousands of "layers" of powdered metal and a laser energy source and represents an early reference to forming "layers" and the fabrication of articles on a substrate.

On 2 July 1984, American entrepreneur Bill Masters filed a patent for his computer automated manufacturing process and system (US 4665492).[21] This filing is on record at the USPTO as the first 3D printing patent in history; it was the first of three patents belonging to Masters that laid the foundation for the 3D printing systems used today.[22][23]

On 16 July 1984, Alain Le Méhauté, Olivier de Witte, and Jean Claude André filed their patent for the stereolithography process.[24] The application of the French inventors was abandoned by the French General Electric Company (now Alcatel-Alsthom) and CILAS (The Laser Consortium).[25] The claimed reason was "for lack of business perspective".[26]

In 1983, Robert Howard started R.H. Research, later named Howtek, Inc. in Feb 1984 to develop a color inkjet 2D printer, Pixelmaster, commercialized in 1986, using Thermoplastic (hot-melt) plastic ink.[27] A team was put together, 6 members[27] from Exxon Office Systems, Danbury Systems Division, an inkjet printer startup and some members of Howtek, Inc group who became popular figures in the 3D printing industry. One Howtek member, Richard Helinski (patent US5136515A, Method and Means for constructing three-dimensional articles by particle deposition, application 11/07/1989 granted 8/04/1992) formed a New Hampshire company C.A.D-Cast, Inc, name later changed to Visual Impact Corporation (VIC) on 8/22/1991. A prototype of the VIC 3D printer for this company is available with a video presentation showing a 3D model printed with a single nozzle inkjet. Another employee Herbert Menhennett formed a New Hampshire company HM Research in 1991 and introduced the Howtek, Inc, inkjet technology and thermoplastic materials to Royden Sanders of SDI and Bill Masters of Ballistic Particle Manufacturing (BPM) where he worked for a number of years. Both BPM 3D printers and SPI 3D printers use Howtek, Inc style Inkjets and Howtek, Inc style materials. Royden Sanders licensed the Helinksi patent prior to manufacturing the Modelmaker 6 Pro at Sanders prototype, Inc (SPI) in 1993. James K. McMahon who was hired by Howtek, Inc to help develop the inkjet, later worked at Sanders Prototype and now operates Layer Grown Model Technology, a 3D service provider specializing in Howtek single nozzle inkjet and SDI printer support. James K. McMahon worked with Steven Zoltan, 1972 drop-on-demand inkjet inventor, at Exxon and has a patent in 1978 that expanded the understanding of the single nozzle design inkjets (Alpha jets) and helped perfect the Howtek, Inc hot-melt inkjets. This Howtek hot-melt thermoplastic technology is popular with metal investment casting, especially in the 3D printing jewelry industry.[28] Sanders (SDI) first Modelmaker 6Pro customer was Hitchner Corporations, Metal Casting Technology, Inc in Milford, NH a mile from the SDI facility in late 1993–1995 casting golf clubs and auto engine parts.

On 8 August 1984 a patent, US4575330, assigned to UVP, Inc., later assigned to Chuck Hull of 3D Systems Corporation[29] was filed, his own patent for a stereolithography fabrication system, in which individual laminae or layers are added by curing photopolymers with impinging radiation, particle bombardment, chemical reaction or just ultraviolet light lasers. Hull defined the process as a "system for generating three-dimensional objects by creating a cross-sectional pattern of the object to be formed".[30][31] Hull's contribution was the STL (Stereolithography) file format and the digital slicing and infill strategies common to many processes today. In 1986, Charles "Chuck" Hull was granted a patent for this system, and his company, 3D Systems Corporation was formed and it released the first commercial 3D printer, the SLA-1,[32] later in 1987 or 1988.

The technology used by most 3D printers to date—especially hobbyist and consumer-oriented models—is fused deposition modeling, a special application of plastic extrusion, developed in 1988 by S. Scott Crump and commercialized by his company Stratasys, which marketed its first FDM machine in 1992.[28]

Owning a 3D printer in the 1980s cost upwards of $300,000 ($650,000 in 2016 dollars).[33]

1990s

[edit]AM processes for metal sintering or melting (such as selective laser sintering, direct metal laser sintering, and selective laser melting) usually went by their own individual names in the 1980s and 1990s. At the time, all metalworking was done by processes that are now called non-additive (casting, fabrication, stamping, and machining); although plenty of automation was applied to those technologies (such as by robot welding and CNC), the idea of a tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope transforming a mass of raw material into a desired shape with a toolpath was associated in metalworking only with processes that removed metal (rather than adding it), such as CNC milling, CNC EDM, and many others. However, the automated techniques that added metal, which would later be called additive manufacturing, were beginning to challenge that assumption. By the mid-1990s, new techniques for material deposition were developed at Stanford and Carnegie Mellon University, including microcasting[34] and sprayed materials.[35] Sacrificial and support materials had also become more common, enabling new object geometries.[36]

The term 3D printing originally referred to a powder bed process employing standard and custom inkjet print heads, developed at MIT by Emanuel Sachs in 1993 and commercialized by Soligen Technologies, Extrude Hone Corporation, and Z Corporation.[citation needed]

The year 1993 also saw the start of an inkjet 3D printer company initially named Sanders Prototype, Inc and later named Solidscape, introducing a high-precision polymer jet fabrication system with soluble support structures, (categorized as a "dot-on-dot" technique).[28]

In 1995 the Fraunhofer Society developed the selective laser melting process.

2000s

[edit]In the early 2000s 3D printers were still largely being used just in the manufacturing and research industries, as the technology was still relatively young and was too expensive for most consumers to be able to get their hands on. The 2000s was when larger scale use of the technology began being seen in industry, most often in the architecture and medical industries, though it was typically used for low accuracy modeling and testing, rather than the production of common manufactured goods or heavy prototyping.[37]

In 2005 users began to design and distribute plans for 3D printers that could print around 70% of their own parts, the original plans of which were designed by Adrian Bowyer at the University of Bath in 2004, with the name of the project being RepRap (Replicating Rapid-prototyper).[38]

Similarly, in 2006 the Fab@Home project was started by Evan Malone and Hod Lipson, another project whose purpose was to design a low-cost and open source fabrication system that users could develop on their own and post feedback on, making the project very collaborative.[39]

Much of the software for 3D printing available to the public at the time was open source, and as such was quickly distributed and improved upon by many individual users. In 2009 the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printing process patents expired. This opened the door to a new wave of startup companies, many of which were established by major contributors of these open source initiatives, with the goal of many of them being to start developing commercial FDM 3D printers that were more accessible to the general public.[40]

2010s

[edit]As the various additive processes matured, it became clear that soon metal removal would no longer be the only metalworking process done through a tool or head moving through a 3D work envelope, transforming a mass of raw material into a desired shape layer by layer. The 2010s were the first decade in which metal end-use parts such as engine brackets[41] and large nuts[42] would be grown (either before or instead of machining) in job production rather than obligately being machined from bar stock or plate. It is still the case that casting, fabrication, stamping, and machining are more prevalent than additive manufacturing in metalworking, but AM is now beginning to make significant inroads, and with the advantages of design for additive manufacturing, it is clear to engineers that much more is to come.

One place that AM is making a significant inroad is in the aviation industry. With nearly 3.8 billion air travelers in 2016,[43] the demand for fuel efficient and easily produced jet engines has never been higher. For large OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) like Pratt and Whitney (PW) and General Electric (GE) this means looking towards AM as a way to reduce cost, reduce the number of nonconforming parts, reduce weight in the engines to increase fuel efficiency and find new, highly complex shapes that would not be feasible with the antiquated manufacturing methods. One example of AM integration with aerospace was in 2016 when Airbus delivered the first of GE's LEAP engines. This engine has integrated 3D-printed fuel nozzles, reducing parts from 20 to 1, a 25% weight reduction, and reduced assembly times.[44] A fuel nozzle is the perfect inroad for additive manufacturing in a jet engine since it allows for optimized design of the complex internals and it is a low-stress, non-rotating part. Similarly, in 2015, PW delivered their first AM parts in the PurePower PW1500G to Bombardier. Sticking to low-stress, non-rotating parts, PW selected the compressor stators and synch ring brackets[45] to roll out this new manufacturing technology for the first time. While AM is still playing a small role in the total number of parts in the jet engine manufacturing process, the return on investment can already be seen by the reduction in parts, the rapid production capabilities and the "optimized design in terms of performance and cost".[46]

As technology matured, several authors began to speculate that 3D printing could aid in sustainable development in the developing world.[47]

In 2012, Filabot developed a system for closing the loop[48] with plastic and allows for any FDM or FFF 3D printer to be able to print with a wider range of plastics.

In 2014, Benjamin S. Cook and Manos M. Tentzeris demonstrated the first multi-material, vertically integrated printed electronics additive manufacturing platform (VIPRE) which enabled 3D printing of functional electronics operating up to 40 GHz.[49]

As the price of printers started to drop people interested in this technology had more access and freedom to make what they wanted. As of 2014, the price for commercial printers was still high with the cost being over $2,000.[50]

The term "3D printing" originally referred to a process that deposits a binder material onto a powder bed with inkjet printer heads layer by layer. More recently, the popular vernacular has started using the term to encompass a wider variety of additive-manufacturing techniques such as electron-beam additive manufacturing and selective laser melting. The United States and global technical standards use the official term additive manufacturing for this broader sense.

The most commonly used 3D printing process (46% as of 2018[update]) is a material extrusion technique called fused deposition modeling, or FDM.[8] While FDM technology was invented after the other two most popular technologies, stereolithography (SLA) and selective laser sintering (SLS), FDM is typically the most inexpensive of the three by a large margin,[citation needed] which lends to the popularity of the process.

2020s

[edit]As of 2020, 3D printers have reached the level of quality and price that allows most people to enter the world of 3D printing. In 2020 decent quality printers can be found for less than US$200 for entry-level machines. These more affordable printers are usually fused deposition modeling (FDM) printers.[51]

In November 2021 a British patient named Steve Verze received the world's first fully 3D-printed prosthetic eye from the Moorfields Eye Hospital in London.[52][53]

In April 2024, the world's largest 3D printer, the Factory of the Future 1.0 was revealed at the University of Maine. It is able to make objects 96 feet long, or 29 meters.[54]

In 2024, researchers used machine learning to improve the construction of synthetic bone[55] and set a record for shock absorption.[56]

In July 2024, researchers published a paper in Advanced Materials Technologies describing the development of artificial blood vessels using 3D-printing technology, which are as strong and durable as natural blood vessels.[57] The process involved using a rotating spindle integrated into a 3D printer to create grafts from a water-based gel, which were then coated in biodegradable polyester molecules.[57]

Benefits of 3D printing

[edit]Additive manufacturing or 3D printing has rapidly gained importance in the field of engineering due to its many benefits. The vision of 3D printing is design freedom, individualization,[58] decentralization[59] and executing processes that were previously impossible through alternative methods.[60] Some of these benefits include enabling faster prototyping, reducing manufacturing costs, increasing product customization, and improving product quality.[61]

Furthermore, the capabilities of 3D printing have extended beyond traditional manufacturing, like lightweight construction,[62] or repair and maintenance[63] with applications in prosthetics,[64] bioprinting,[65] food industry,[66] rocket building,[67] design and art[68] and renewable energy systems.[69] 3D printing technology can be used to produce battery energy storage systems, which are essential for sustainable energy generation and distribution.

Another benefit of 3D printing is the technology's ability to produce complex geometries with high precision and accuracy.[70] This is particularly relevant in the field of microwave engineering, where 3D printing can be used to produce components with unique properties that are difficult to achieve using traditional manufacturing methods.[71]

Additive Manufacturing processes generate minimal waste by adding material only where needed, unlike traditional methods that cut away excess material.[72] This reduces both material costs and environmental impact.[73] This reduction in waste also lowers energy consumption for material production and disposal, contributing to a smaller carbon footprint.[74][75]

General principles

[edit]Modeling

[edit]

3D printable models may be created with a computer-aided design (CAD) package, via a 3D scanner, or by a plain digital camera and photogrammetry software. 3D printed models created with CAD result in relatively fewer errors than other methods. Errors in 3D printable models can be identified and corrected before printing.[76] The manual modeling process of preparing geometric data for 3D computer graphics is similar to plastic arts such as sculpting. 3D scanning is a process of collecting digital data on the shape and appearance of a real object, and creating a digital model based on it.

CAD models can be saved in the stereolithography file format (STL), a de facto CAD file format for additive manufacturing that stores data based on triangulations of the surface of CAD models. STL is not tailored for additive manufacturing because it generates large file sizes of topology-optimized parts and lattice structures due to the large number of surfaces involved. A newer CAD file format, the additive manufacturing file format (AMF), was introduced in 2011 to solve this problem. It stores information using curved triangulations.[77]

Printing

[edit]Before printing a 3D model from an STL file, it must first be examined for errors. Most CAD applications produce errors in output STL files,[78][79] of the following types:

A step in the STL generation known as "repair" fixes such problems in the original model.[82][83] Generally, STLs that have been produced from a model obtained through 3D scanning often have more of these errors[84] as 3D scanning is often achieved by point to point acquisition/mapping. 3D reconstruction often includes errors.[85]

Once completed, the STL file needs to be processed by a piece of software called a "slicer", which converts the model into a series of thin layers and produces a G-code file containing instructions tailored to a specific type of 3D printer (FDM printers).[86] This G-code file can then be printed with 3D printing client software (which loads the G-code and uses it to instruct the 3D printer during the 3D printing process).

Printer resolution describes layer thickness and X–Y resolution in dots per inch (dpi) or micrometers (μm). Typical layer thickness is around 100 μm (250 DPI), although some machines can print layers as thin as 16 μm (1,600 DPI).[87] X–Y resolution is comparable to that of laser printers. The particles (3D dots) are around 0.01 to 0.1 μm (2,540,000 to 250,000 DPI) in diameter.[88] For that printer resolution, specifying a mesh resolution of 0.01–0.03 mm and a chord length ≤ 0.016 mm generates an optimal STL output file for a given model input file.[89] Specifying higher resolution results in larger files without increase in print quality.

Construction of a model with contemporary methods can take anywhere from several hours to several days, depending on the method used and the size and complexity of the model. Additive systems can typically reduce this time to a few hours, although it varies widely depending on the type of machine used and the size and number of models being produced simultaneously.

Finishing

[edit]Though the printer-produced resolution and surface finish are sufficient for some applications, post-processing and finishing methods allow for benefits such as greater dimensional accuracy, smoother surfaces, and other modifications such as coloration.

The surface finish of a 3D-printed part can improved using subtractive methods such as sanding and bead blasting. When smoothing parts that require dimensional accuracy, it is important to take into account the volume of the material being removed.[90]

Some printable polymers, such as acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), allow the surface finish to be smoothed and improved using chemical vapor processes[91] based on acetone or similar solvents.

Some additive manufacturing techniques can benefit from annealing as a post-processing step. Annealing a 3D-printed part allows for better internal layer bonding due to recrystallization of the part. It allows for an increase in mechanical properties, some of which are fracture toughness,[92] flexural strength,[93] impact resistance,[94] and heat resistance.[94] Annealing a component may not be suitable for applications where dimensional accuracy is required, as it can introduce warpage or shrinkage due to heating and cooling.[95]

Additive or subtractive hybrid manufacturing (ASHM) is a method that involves producing a 3D printed part and using machining (subtractive manufacturing) to remove material.[96] Machining operations can be completed after each layer, or after the entire 3D print has been completed depending on the application requirements. These hybrid methods allow for 3D-printed parts to achieve better surface finishes and dimensional accuracy.[97]

The layered structure of traditional additive manufacturing processes leads to a stair-stepping effect on part-surfaces that are curved or tilted with respect to the building platform. The effect strongly depends on the layer height used, as well as the orientation of a part surface inside the building process.[98] This effect can be minimized using "variable layer heights" or "adaptive layer heights". These methods decrease the layer height in places where higher quality is needed.[99]

Painting a 3D-printed part offers a range of finishes and appearances that may not be achievable through most 3D printing techniques. The process typically involves several steps, such as surface preparation, priming, and painting.[100] These steps help prepare the surface of the part and ensuring the paint adheres properly.

Some additive manufacturing techniques are capable of using multiple materials simultaneously. These techniques are able to print in multiple colors and color combinations simultaneously and can produce parts that may not necessarily require painting.

Some printing techniques require internal supports to be built to support overhanging features during construction. These supports must be mechanically removed or dissolved if using a water-soluble support material such as PVA after completing a print.

Some commercial metal 3D printers involve cutting the metal component off the metal substrate after deposition. A new process for the GMAW 3D printing allows for substrate surface modifications to remove aluminium[101] or steel.[102]

Materials

[edit]

Traditionally, 3D printing focused on polymers for printing, due to the ease of manufacturing and handling polymeric materials. However, the method has rapidly evolved to not only print various polymers[104] but also metals,[105][106] chocolates,[107] and ceramics,[108] making 3D printing a versatile option for manufacturing. Layer-by-layer fabrication of three-dimensional physical models is a modern concept that "stems from the ever-growing CAD industry, more specifically the solid modeling side of CAD. Before solid modeling was introduced in the late 1980s, three-dimensional models were created with wire frames and surfaces."[109] but in all cases the layers of materials are controlled by the printer and the material properties. The three-dimensional material layer is controlled by the deposition rate as set by the printer operator and stored in a computer file. The earliest printed patented material was a hot melt type ink for printing patterns using a heated metal alloy.

Charles Hull filed the first patent on August 8, 1984, to use a UV-cured acrylic resin using a UV-masked light source at UVP Corp to build a simple model. The SLA-1 was the first SL product announced by 3D Systems at Autofact Exposition, Detroit, November 1978. The SLA-1 Beta shipped in Jan 1988 to Baxter Healthcare, Pratt and Whitney, General Motors and AMP. The first production SLA-1 shipped to Precision Castparts in April 1988. The UV resin material changed over quickly to an epoxy-based material resin. In both cases, SLA-1 models needed UV oven curing after being rinsed in a solvent cleaner to remove uncured boundary resin. A post cure apparatus (PCA) was sold with all systems. The early resin printers required a blade to move fresh resin over the model on each layer. The layer thickness was 0.006 inches and the HeCd laser model of the SLA-1 was 12 watts and swept across the surface at 30 inch per second. UVP was acquired by 3D Systems in January 1990.[110]

A review of the history shows that a number of materials (resins, plastic powder, plastic filament and hot-melt plastic ink) were used in the 1980s for patents in the rapid prototyping field. Masked lamp UV-cured resin was also introduced by Cubital's Itzchak Pomerantz in the Soldier 5600, Carl Deckard's (DTM) laser sintered thermoplastic powders, and adhesive-laser cut paper (LOM) stacked to form objects by Michael Feygin before 3D Systems made its first announcement. Scott Crump was also working with extruded "melted" plastic filament modeling (FDM) and drop deposition had been patented by William E Masters a week after Hull's patent in 1984, but he had to discover thermoplastic inkjets, introduced by Visual Impact Corporation 3D printer in 1992, using inkjets from Howtek, Inc., before he formed BPM to bring out his own 3D printer product in 1994.[110]

The most common polymers for personal 3D printers are polylactic acid (PLA) and PETG.

Multi-material 3D printing

[edit]

Efforts to achieve multi-material 3D printing range from enhanced FDM-like processes like VoxelJet to novel voxel-based printing technologies like layered assembly.[111]

A drawback of many existing 3D printing technologies is that they only allow one material to be printed at a time, limiting many potential applications that require the integration of different materials in the same object. Multi-material 3D printing solves this problem by allowing objects of complex and heterogeneous arrangements of materials to be manufactured using a single printer. Here, a material must be specified for each voxel (or 3D printing pixel element) inside the final object volume.

The process can be fraught with complications, however, due to the isolated and monolithic algorithms. Some commercial devices have sought to solve these issues, such as building a Spec2Fab translator, but the progress is still very limited.[112] Nonetheless, in the medical industry, a concept of 3D-printed pills and vaccines has been presented.[113] With this new concept, multiple medications can be combined, which is expected to decrease many risks. With more and more applications of multi-material 3D printing, the costs of daily life and high technology development will become inevitably lower.

Metallographic materials of 3D printing is also being researched.[114] By classifying each material, CIMP-3D can systematically perform 3D printing with multiple materials.[115]

4D printing

[edit]Using 3D printing and multi-material structures in additive manufacturing has allowed for the design and creation of what is called 4D printing. 4D printing is an additive manufacturing process in which the printed object changes shape with time, temperature, or some other type of stimulation. 4D printing allows for the creation of dynamic structures with adjustable shapes, properties or functionality. The smart/stimulus-responsive materials that are created using 4D printing can be activated to create calculated responses such as self-assembly, self-repair, multi-functionality, reconfiguration and shape-shifting. This allows for customized printing of shape-changing and shape-memory materials.[116]

4D printing has the potential to find new applications and uses for materials (plastics, composites, metals, etc.) and has the potential to create new alloys and composites that were not viable before. The versatility of this technology and materials can lead to advances in multiple fields of industry, including space, commercial and medical fields. The repeatability, precision, and material range for 4D printing must increase to allow the process to become more practical throughout these industries.

To become a viable industrial production option, there are a few challenges that 4D printing must overcome. The challenges of 4D printing include the fact that the microstructures of these printed smart materials must be close to or better than the parts obtained through traditional machining processes. New and customizable materials need to be developed that have the ability to consistently respond to varying external stimuli and change to their desired shape. There is also a need to design new software for the various technique types of 4D printing. The 4D printing software will need to take into consideration the base smart material, printing technique, and structural and geometric requirements of the design.[117]

Processes and printers

[edit]This section should include only a brief summary of 3D printing processes. (August 2017) |

ISO/ASTM52900-15 defines seven categories of additive manufacturing (AM) processes within its meaning.[118][119] They are:

- Vat photopolymerization

- Material jetting

- Binder jetting

- Powder bed fusion

- Material extrusion

- Directed energy deposition

- Sheet lamination

The main differences between processes are in the way layers are deposited to create parts and in the materials that are used. Each method has its own advantages and drawbacks, which is why some companies offer a choice of powder and polymer for the material used to build the object.[120] Others sometimes use standard, off-the-shelf business paper as the build material to produce a durable prototype. The main considerations in choosing a machine are generally speed, costs of the 3D printer, of the printed prototype, choice and cost of the materials, and color capabilities.[121] Printers that work directly with metals are generally expensive. However, less expensive printers can be used to make a mold, which is then used to make metal parts.[122]

Material jetting

[edit]The first process where three-dimensional material is deposited to form an object was done with material jetting[28] or as it was originally called particle deposition. Particle deposition by inkjet first started with continuous inkjet technology (CIT) (1950s) and later with drop-on-demand inkjet technology (1970s) using hot-melt inks. Wax inks were the first three-dimensional materials jetted and later low-temperature alloy metal was jetted with CIT. Wax and thermoplastic hot melts were jetted next by DOD. Objects were very small and started with text characters and numerals for signage. An object must have form and can be handled. Wax characters tumbled off paper documents and inspired a liquid metal recorder patent to make metal characters for signage in 1971. Thermoplastic color inks (CMYK) were printed with layers of each color to form the first digitally formed layered objects in 1984. The idea of investment casting with Solid-Ink jetted images or patterns in 1984 led to the first patent to form articles from particle deposition in 1989, issued in 1992.

Material extrusion

[edit]

Some methods melt or soften the material to produce the layers. In fused filament fabrication, also known as fused deposition modeling (FDM), the model or part is produced by extruding small beads or streams of material that harden immediately to form layers. A filament of thermoplastic, metal wire, or other material is fed into an extrusion nozzle head (3D printer extruder), which heats the material and turns the flow on and off. FDM is somewhat restricted in the variation of shapes that may be fabricated. Another technique fuses parts of the layer and then moves upward in the working area, adding another layer of granules and repeating the process until the piece has built up. This process uses the unfused media to support overhangs and thin walls in the part being produced, which reduces the need for temporary auxiliary supports for the piece.[123] Recently, FFF/FDM has expanded to 3-D print directly from pellets to avoid the conversion to filament. This process is called fused particle fabrication (FPF) (or fused granular fabrication (FGF) and has the potential to use more recycled materials.[124]

Powder bed fusion

[edit]Powder bed fusion techniques, or PBF, include several processes such as DMLS, SLS, SLM, MJF and EBM. Powder bed fusion processes can be used with an array of materials and their flexibility allows for geometrically complex structures,[125] making it a good choice for many 3D printing projects. These techniques include selective laser sintering, with both metals and polymers and direct metal laser sintering.[126] Selective laser melting does not use sintering for the fusion of powder granules but will completely melt the powder using a high-energy laser to create fully dense materials in a layer-wise method that has mechanical properties similar to those of conventional manufactured metals. Electron beam melting is a similar type of additive manufacturing technology for metal parts (e.g. titanium alloys). EBM manufactures parts by melting metal powder layer by layer with an electron beam in a high vacuum.[127][128] Another method consists of an inkjet 3D printing system, which creates the model one layer at a time by spreading a layer of powder (plaster or resins) and printing a binder in the cross-section of the part using an inkjet-like process. With laminated object manufacturing, thin layers are cut to shape and joined. In addition to the previously mentioned methods, HP has developed the Multi Jet Fusion (MJF) which is a powder base technique, though no lasers are involved. An inkjet array applies fusing and detailing agents which are then combined by heating to create a solid layer.[129]

Binder jetting

[edit]The binder jetting 3D printing technique involves the deposition of a binding adhesive agent onto layers of material, usually powdered, and then this "green" state part may be cured and even sintered. The materials can be ceramic-based, metal or plastic. This method is also known as inkjet 3D printing. To produce a part, the printer builds the model using a head that moves over the platform base to spread or deposit alternating layers of powder (plaster and resins) and binder. Most modern binder jet printers also cure each layer of binder. These steps are repeated until all layers have been printed. This green part is usually cured in an oven to off-gas most of the binder before being sintered in a kiln with a specific time-temperature curve for the given material(s).

This technology allows the printing of full-color prototypes, overhangs, and elastomer parts. The strength of bonded powder prints can be enhanced by impregnating in the spaces between the necked or sintered matrix of powder with other compatible materials depending on the powder material, like wax, thermoset polymer, or even bronze.[130][131]

Stereolithography

[edit]Other methods cure liquid materials using different sophisticated technologies, such as stereolithography. Photopolymerization is primarily used in stereolithography to produce a solid part from a liquid. Inkjet printer systems like the Objet PolyJet system spray photopolymer materials onto a build tray in ultra-thin layers (between 16 and 30 μm) until the part is completed.[132] Each photopolymer layer is cured with UV light after it is jetted, producing fully cured models that can be handled and used immediately, without post-curing. Ultra-small features can be made with the 3D micro-fabrication technique used in multiphoton photopolymerisation. Due to the nonlinear nature of photo excitation, the gel is cured to a solid only in the places where the laser was focused while the remaining gel is then washed away. Feature sizes of under 100 nm are easily produced, as well as complex structures with moving and interlocked parts.[133] Yet another approach uses a synthetic resin that is solidified using LEDs.[134]

In Mask-image-projection-based stereolithography, a 3D digital model is sliced by a set of horizontal planes. Each slice is converted into a two-dimensional mask image. The mask image is then projected onto a photocurable liquid resin surface and light is projected onto the resin to cure it in the shape of the layer.[135] Continuous liquid interface production begins with a pool of liquid photopolymer resin. Part of the pool bottom is transparent to ultraviolet light (the "window"), which causes the resin to solidify. The object rises slowly enough to allow the resin to flow under and maintain contact with the bottom of the object.[136] In powder-fed directed-energy deposition, a high-power laser is used to melt metal powder supplied to the focus of the laser beam. The powder-fed directed energy process is similar to selective laser sintering, but the metal powder is applied only where material is being added to the part at that moment.[137][138]

Computed axial lithography

[edit]Computed axial lithography is a method for 3D printing based on computerised tomography scans to create prints in photo-curable resin. It was developed by a collaboration between the University of California, Berkeley with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.[139][140][141] Unlike other methods of 3D printing it does not build models through depositing layers of material like fused deposition modelling and stereolithography, instead it creates objects using a series of 2D images projected onto a cylinder of resin.[139][141] It is notable for its ability to build an object much more quickly than other methods using resins and the ability to embed objects within the prints.[140]

Liquid additive manufacturing

[edit]Liquid additive manufacturing (LAM) is a 3D printing technique that deposits a liquid or high viscosity material (e.g. liquid silicone rubber) onto a build surface to create an object which then is vulcanised using heat to harden the object.[142][143][144] The process was originally created by Adrian Bowyer and was then built upon by German RepRap.[142][145][146]

A technique called programmable tooling uses 3D printing to create a temporary mold, which is then filled via a conventional injection molding process and then immediately dissolved.[147]

Lamination

[edit]In some printers, paper can be used as the build material, resulting in a lower cost to print. During the 1990s some companies marketed printers that cut cross-sections out of special adhesive coated paper using a carbon dioxide laser and then laminated them together.

In 2005 Mcor Technologies Ltd developed a different process using ordinary sheets of office paper, a tungsten carbide blade to cut the shape, and selective deposition of adhesive and pressure to bond the prototype.[148]

Directed-energy deposition (DED)

[edit]Powder-fed directed-energy deposition

[edit]In powder-fed directed-energy deposition (also known as laser metal deposition), a high-power laser is used to melt metal powder supplied to the focus of the laser beam. The laser beam typically travels through the center of the deposition head and is focused on a small spot by one or more lenses. The build occurs on an X-Y table which is driven by a tool path created from a digital model to fabricate an object layer by layer. The deposition head is moved up vertically as each layer is completed. Some systems even make use of 5-axis[149][150] or 6-axis systems[151] (i.e. articulated arms) capable of delivering material on the substrate (a printing bed, or a pre-existing part[152]) with few to no spatial access restrictions. Metal powder is delivered and distributed around the circumference of the head or can be split by an internal manifold and delivered through nozzles arranged in various configurations around the deposition head. A hermetically sealed chamber filled with inert gas or a local inert shroud gas (sometimes both combined) is often used to shield the melt pool from atmospheric oxygen, to limit oxidation and to better control the material properties. The powder-fed directed-energy process is similar to selective laser sintering, but the metal powder is projected only where the material is being added to the part at that moment. The laser beam is used to heat up and create a "melt pool" on the substrate, in which the new powder is injected quasi-simultaneously. The process supports a wide range of materials including titanium, stainless steel, aluminium, tungsten, and other specialty materials as well as composites and functionally graded materials. The process can not only fully build new metal parts but can also add material to existing parts for example for coatings, repair, and hybrid manufacturing applications. Laser engineered net shaping (LENS), which was developed by Sandia National Labs, is one example of the powder-fed directed-energy deposition process for 3D printing or restoring metal parts.[153][154]

Metal wire processes

[edit]Laser-based wire-feed systems, such as laser metal deposition-wire (LMD-w), feed the wire through a nozzle that is melted by a laser using inert gas shielding in either an open environment (gas surrounding the laser) or in a sealed chamber. Electron beam freeform fabrication uses an electron beam heat source inside a vacuum chamber.

It is also possible to use conventional gas metal arc welding attached to a 3D stage to 3-D print metals such as steel, bronze and aluminium.[155][156] Low-cost open source RepRap-style 3-D printers have been outfitted with Arduino-based sensors and demonstrated reasonable metallurgical properties from conventional welding wire as feedstock.[157]

Selective powder deposition (SPD)

[edit]In selective powder deposition, build and support powders are selectively deposited into a crucible, such that the build powder takes the shape of the desired object and support powder fills the rest of the volume in the crucible. Then an infill material is applied, such that it comes in contact with the build powder. Then the crucible is fired up in a kiln at the temperature above the melting point of the infill but below the melting points of the powders. When the infill melts, it soaks the build powder. But it does not soak the support powder, because the support powder is chosen to be such that it is not wettable by the infill. If at the firing temperature, the atoms of the infill material and the build powder are mutually defusable, such as in the case of copper powder and zinc infill, then the resulting material will be a uniform mixture of those atoms, in this case, bronze. But if the atoms are not mutually defusable, such as in the case of tungsten and copper at 1100 °C, then the resulting material will be a composite. To prevent shape distortion, the firing temperature must be below the solidus temperature of the resulting alloy.[158]

Cryogenic 3D printing

[edit]Cryogenic 3D printing is a collection of techniques that forms solid structures by freezing liquid materials while they are deposited. As each liquid layer is applied, it is cooled by the low temperature of the previous layer and printing environment which results in solidification. Unlike other 3D printing techniques, cryogenic 3D printing requires a controlled printing environment. The ambient temperature must be below the material's freezing point to ensure the structure remains solid during manufacturing and the humidity must remain low to prevent frost formation between the application of layers.[159] Materials typically include water and water-based solutions, such as brine, slurry, and hydrogels.[160][161] Cryogenic 3D printing techniques include rapid freezing prototype (RFP),[160] low-temperature deposition manufacturing (LDM),[162] and freeze-form extrusion fabrication (FEF).[163]

Applications

[edit]This section may benefit from being shortened by the use of summary style. |

3D printing or additive manufacturing has been used in manufacturing, medical, industry and sociocultural sectors (e.g. cultural heritage) to create successful commercial technology.[164] More recently, 3D printing has also been used in the humanitarian and development sector to produce a range of medical items, prosthetics, spares and repairs.[165] The earliest application of additive manufacturing was on the toolroom end of the manufacturing spectrum. For example, rapid prototyping was one of the earliest additive variants, and its mission was to reduce the lead time and cost of developing prototypes of new parts and devices, which was earlier only done with subtractive toolroom methods such as CNC milling, turning, and precision grinding.[166] In the 2010s, additive manufacturing entered production to a much greater extent.

Food

[edit]Additive manufacturing of food is being developed by squeezing out food, layer by layer, into three-dimensional objects. A large variety of foods are appropriate candidates, such as chocolate and candy, and flat foods such as crackers, pasta,[167] and pizza.[168][169] NASA is looking into the technology in order to create 3D-printed food to limit food waste and to make food that is designed to fit an astronaut's dietary needs.[170] In 2018, Italian bioengineer Giuseppe Scionti developed a technology allowing the production of fibrous plant-based meat analogues using a custom 3D bioprinter, mimicking meat texture and nutritional values.[171][172]

Fashion

[edit]

3D printing has entered the world of clothing, with fashion designers experimenting with 3D-printed bikinis, shoes, and dresses.[173] In commercial production, Nike used 3D printing to prototype and manufacture the 2012 Vapor Laser Talon football shoe for players of American football, and New Balance has 3D manufactured custom-fit shoes for athletes.[173][174] 3D printing has come to the point where companies are printing consumer-grade eyewear with on-demand custom fit and styling (although they cannot print the lenses). On-demand customization of glasses is possible with rapid prototyping.[175]

Transportation

[edit]

In cars, trucks, and aircraft, additive manufacturing is beginning to transform both unibody and fuselage design and production, and powertrain design and production. For example, General Electric uses high-end 3D printers to build parts for turbines.[176] Many of these systems are used for rapid prototyping before mass production methods are employed. Other prominent examples include:

- In early 2014, Swedish sports car manufacturer Koenigsegg announced the One:1, a sports car that utilizes many components that were 3D printed.[177] Urbee is the first car produced using 3D printing (the bodywork and car windows were "printed").[178][179][180]

- In 2014, Local Motors debuted Strati, a functioning vehicle that was entirely 3D printed using ABS plastic and carbon fiber, except the powertrain.[181]

- In May 2015 Airbus announced that its new Airbus A350 XWB included over 1000 components manufactured by 3D printing.[182]

- In 2015, a Royal Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jet flew with printed parts. The United States Air Force has begun to work with 3D printers, and the Israeli Air Force has also purchased a 3D printer to print spare parts.[183]

- In 2017, GE Aviation revealed that it had used design for additive manufacturing to create a helicopter engine with 16 parts instead of 900, with great potential impact on reducing the complexity of supply chains.[184]

Firearms

[edit]AM's impact on firearms involves two dimensions: new manufacturing methods for established companies, and new possibilities for the making of do-it-yourself firearms. In 2012, the US-based group Defense Distributed disclosed plans to design a working plastic 3D-printed firearm "that could be downloaded and reproduced by anybody with a 3D printer".[185][186] After Defense Distributed released their plans, questions were raised regarding the effects that 3D printing and widespread consumer-level CNC machining[187][188] may have on gun control effectiveness.[189][190][191][192] Moreover, armor-design strategies can be enhanced by taking inspiration from nature and prototyping those designs easily, using AM.[193]

Health

[edit]Surgical uses of 3D printing-centric therapies began in the mid-1990s with anatomical modeling for bony reconstructive surgery planning. Patient-matched implants were a natural extension of this work, leading to truly personalized implants that fit one unique individual.[194] Virtual planning of surgery and guidance using 3D printed, personalized instruments have been applied to many areas of surgery including total joint replacement and craniomaxillofacial reconstruction with great success.[195][196] One example of this is the bioresorbable trachial splint to treat newborns with tracheobronchomalacia[197] developed at the University of Michigan. The use of additive manufacturing for serialized production of orthopedic implants (metals) is also increasing due to the ability to efficiently create porous surface structures that facilitate osseointegration. The hearing aid and dental industries are expected to be the biggest areas of future development using custom 3D printing technology.[198]

3D printing is not just limited to inorganic materials; there have been a number of biomedical advancements made possible by 3D printing. As of 2012[update], 3D bio-printing technology has been studied by biotechnology firms and academia for possible use in tissue engineering applications in which organs and body parts are built using inkjet printing techniques. In this process, layers of living cells are deposited onto a gel medium or sugar matrix and slowly built up to form three-dimensional structures including vascular systems.[199] 3D printing has been considered as a method of implanting stem cells capable of generating new tissues and organs in living humans.[200] In 2018, 3D printing technology was used for the first time to create a matrix for cell immobilization in fermentation. Propionic acid production by Propionibacterium acidipropionici immobilized on 3D-printed nylon beads was chosen as a model study. It was shown that those 3D-printed beads were capable of promoting high-density cell attachment and propionic acid production, which could be adapted to other fermentation bioprocesses.[201]

3D printing has also been employed by researchers in the pharmaceutical field. During the last few years, there has been a surge in academic interest regarding drug delivery with the aid of AM techniques. This technology offers a unique way for materials to be utilized in novel formulations.[202] AM manufacturing allows for the usage of materials and compounds in the development of formulations, in ways that are not possible with conventional/traditional techniques in the pharmaceutical field, e.g. tableting, cast-molding, etc. Moreover, one of the major advantages of 3D printing, especially in the case of fused deposition modelling (FDM), is the personalization of the dosage form that can be achieved, thus, targeting the patient's specific needs.[203] In the not-so-distant future, 3D printers are expected to reach hospitals and pharmacies in order to provide on-demand production of personalized formulations according to the patients' needs.[204]

3D printing has also been used for medical equipment. During the COVID-19 pandemic 3D printers were used to supplement the strained supply of PPE through volunteers using their personally owned printers to produce various pieces of personal protective equipment (i.e. frames for face shields).

Education

[edit]3D printing, and open source 3D printers, in particular, are the latest technologies making inroads into the classroom.[205][206][207] Higher education has proven to be a major buyer of desktop and professional 3D printers which industry experts generally view as a positive indicator.[208] Some authors have claimed that 3D printers offer an unprecedented "revolution" in STEM education.[209][210] The evidence for such claims comes from both the low-cost ability for rapid prototyping in the classroom by students, but also the fabrication of low-cost high-quality scientific equipment from open hardware designs forming open-source labs.[211] Additionally, Libraries around the world have also become locations to house smaller 3D printers for educational and community access.[212] Future applications for 3D printing might include creating open-source scientific equipment.[211][213]

Replicating archeological artifacts

[edit]In the 2010s, 3D printing became intensively used in the cultural heritage field for preservation, restoration and dissemination purposes.[214] Many Europeans and North American Museums have purchased 3D printers and actively recreate missing pieces of their relics[215] and archaeological monuments such as Tiwanaku in Bolivia.[216] The Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum have started using their 3D printers to create museum souvenirs that are available in the museum shops.[217] Other museums, like the National Museum of Military History and Varna Historical Museum, have gone further and sell through the online platform Threeding digital models of their artifacts, created using Artec 3D scanners, in 3D printing friendly file format, which everyone can 3D print at home.[218] Morehshin Allahyari, an Iranian-born U.S. artist, considers her use of 3D sculpting processes of re-constructing Iranian cultural treasures as feminist activism. Allahyari uses a 3D modeling software to reconstruct a series of cultural artifacts that were demolished by ISIS militants in 2014.[219]

Replicating historic buildings and architectural structures

[edit]

The application of 3D printing for the representation of architectural assets has many challenges. In 2018, the structure of Iran National Bank was traditionally surveyed and modeled in computer graphics software (specifically, Cinema4D) and was optimized for 3D printing. The team tested the technique for the construction of the part and it was successful. After testing the procedure, the modellers reconstructed the structure in Cinema4D and exported the front part of the model to Netfabb. The entrance of the building was chosen due to the 3D printing limitations and the budget of the project for producing the maquette. 3D printing was only one of the capabilities enabled by the produced 3D model of the bank, but due to the project's limited scope, the team did not continue modelling for the virtual representation or other applications.[220] In 2021, Parsinejad et al. comprehensively compared the hand surveying method for 3D reconstruction ready for 3D printing with digital recording (adoption of photogrammetry method).[220]

The world's first 3D-printed steel bridge was unveiled in Amsterdam in July 2021. Spanning 12 meters over the Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal, the bridge was created using robotic arms that printed over 4,500 kilograms of stainless steel. It took six months to complete.[221]

Soft actuators

[edit]3D printed soft actuators is a growing application of 3D printing technology that has found its place in the 3D printing applications. These soft actuators are being developed to deal with soft structures and organs, especially in biomedical sectors and where the interaction between humans and robots is inevitable. The majority of the existing soft actuators are fabricated by conventional methods that require manual fabrication of devices, post-processing/assembly, and lengthy iterations until the maturity of the fabrication is achieved. Instead of the tedious and time-consuming aspects of the current fabrication processes, researchers are exploring an appropriate manufacturing approach for the effective fabrication of soft actuators. Thus, 3D-printed soft actuators are introduced to revolutionize the design and fabrication of soft actuators with custom geometrical, functional, and control properties in a faster and inexpensive approach. They also enable incorporation of all actuator components into a single structure eliminating the need to use external joints, adhesives, and fasteners.

Circuit boards

[edit]Circuit board manufacturing involves multiple steps which include imaging, drilling, plating, solder mask coating, nomenclature printing and surface finishes. These steps include many chemicals such as harsh solvents and acids. 3D printing circuit boards remove the need for many of these steps while still producing complex designs.[222] Polymer ink is used to create the layers of the build while silver polymer is used for creating the traces and holes used to allow electricity to flow.[223] Current circuit board manufacturing can be a tedious process depending on the design. Specified materials are gathered and sent into inner layer processing where images are printed, developed and etched. The etch cores are typically punched to add lamination tooling. The cores are then prepared for lamination. The stack-up, the buildup of a circuit board, is built and sent into lamination where the layers are bonded. The boards are then measured and drilled. Many steps may differ from this stage however for simple designs, the material goes through a plating process to plate the holes and surface. The outer image is then printed, developed and etched. After the image is defined, the material must get coated with a solder mask for later soldering. Nomenclature is then added so components can be identified later. Then the surface finish is added. The boards are routed out of panel form into their singular or array form and then electrically tested. Aside from the paperwork that must be completed which proves the boards meet specifications, the boards are then packed and shipped. The benefits of 3D printing would be that the final outline is defined from the beginning, no imaging, punching or lamination is required and electrical connections are made with the silver polymer which eliminates drilling and plating. The final paperwork would also be greatly reduced due to the lack of materials required to build the circuit board. Complex designs which may take weeks to complete through normal processing can be 3D printed, greatly reducing manufacturing time.

Hobbyists

[edit]In 2005, academic journals began to report on the possible artistic applications of 3D printing technology.[224] Off-the-shelf machines were increasingly capable of producing practical household applications, for example, ornamental objects. Some practical examples include a working clock[225] and gears printed for home woodworking machines among other purposes.[226] Websites associated with home 3D printing tended to include backscratchers, coat hooks, door knobs, etc.[227] As of 2017, domestic 3D printing was reaching a consumer audience beyond hobbyists and enthusiasts. Several projects and companies are making efforts to develop affordable 3D printers for home desktop use. Much of this work has been driven by and targeted at DIY/maker/enthusiast/early adopter communities, with additional ties to the academic and hacker communities.

Sped on by decreases in price and increases in quality, As of 2019[update] an estimated 2 million people worldwide have purchased a 3D printer for hobby use.[228]

Legal aspects

[edit]Intellectual property

[edit]3D printing has existed for decades within certain manufacturing industries where many legal regimes, including patents, industrial design rights, copyrights, and trademarks may apply. However, there is not much jurisprudence to say how these laws will apply if 3D printers become mainstream and individuals or hobbyist communities begin manufacturing items for personal use, for non-profit distribution, or for sale.

Any of the mentioned legal regimes may prohibit the distribution of the designs used in 3D printing or the distribution or sale of the printed item. To be allowed to do these things, where active intellectual property was involved, a person would have to contact the owner and ask for a licence, which may come with conditions and a price. However, many patent, design and copyright laws contain a standard limitation or exception for "private" or "non-commercial" use of inventions, designs or works of art protected under intellectual property (IP). That standard limitation or exception may leave such private, non-commercial uses outside the scope of IP rights.

Patents cover inventions including processes, machines, manufacturing, and compositions of matter and have a finite duration which varies between countries, but generally 20 years from the date of application. Therefore, if a type of wheel is patented, printing, using, or selling such a wheel could be an infringement of the patent.[229]

Copyright covers an expression[230] in a tangible, fixed medium and often lasts for the life of the author plus 70 years thereafter.[231] For example, a sculptor retains copyright over a statue, such that other people cannot then legally distribute designs to print an identical or similar statue without paying royalties, waiting for the copyright to expire, or working within a fair use exception.

When a feature has both artistic (copyrightable) and functional (patentable) merits when the question has appeared in US court, the courts have often held the feature is not copyrightable unless it can be separated from the functional aspects of the item.[231] In other countries the law and the courts may apply a different approach allowing, for example, the design of a useful device to be registered (as a whole) as an industrial design on the understanding that, in case of unauthorized copying, only the non-functional features may be claimed under design law whereas any technical features could only be claimed if covered by a valid patent.

Gun legislation and administration

[edit]The US Department of Homeland Security and the Joint Regional Intelligence Center released a memo stating that "significant advances in three-dimensional (3D) printing capabilities, availability of free digital 3D printable files for firearms components, and difficulty regulating file sharing may present public safety risks from unqualified gun seekers who obtain or manufacture 3D printed guns" and that "proposed legislation to ban 3D printing of weapons may deter, but cannot completely prevent their production. Even if the practice is prohibited by new legislation, online distribution of these 3D printable files will be as difficult to control as any other illegally traded music, movie or software files."[232]

Attempting to restrict the distribution of gun plans via the Internet has been likened to the futility of preventing the widespread distribution of DeCSS, which enabled DVD ripping.[233][234][235][236] After the US government had Defense Distributed take down the plans, they were still widely available via the Pirate Bay and other file sharing sites.[237] Downloads of the plans from the UK, Germany, Spain, and Brazil were heavy.[238][239] Some US legislators have proposed regulations on 3D printers to prevent them from being used for printing guns.[240][241] 3D printing advocates have suggested that such regulations would be futile, could cripple the 3D printing industry and could infringe on free speech rights, with early pioneers of 3D printing professor Hod Lipson suggesting that gunpowder could be controlled instead.[242][243][244][245][246][247]

Internationally, where gun controls are generally stricter than in the United States, some commentators have said the impact may be more strongly felt since alternative firearms are not as easily obtainable.[248] Officials in the United Kingdom have noted that producing a 3D-printed gun would be illegal under their gun control laws.[249] Europol stated that criminals have access to other sources of weapons but noted that as technology improves, the risks of an effect would increase.[250][251]

Aerospace regulation

[edit]In the United States, the FAA has anticipated a desire to use additive manufacturing techniques and has been considering how best to regulate this process.[252] The FAA has jurisdiction over such fabrication because all aircraft parts must be made under FAA production approval or under other FAA regulatory categories.[253] In December 2016, the FAA approved the production of a 3D-printed fuel nozzle for the GE LEAP engine.[254] Aviation attorney Jason Dickstein has suggested that additive manufacturing is merely a production method, and should be regulated like any other production method.[255][256] He has suggested that the FAA's focus should be on guidance to explain compliance, rather than on changing the existing rules, and that existing regulations and guidance permit a company "to develop a robust quality system that adequately reflects regulatory needs for quality assurance".[255]

Quality assurance

[edit]In 2021, first standards were issued, e.g. ASTM ISO/ASTM52900-21 Additive manufacturing general principles, fundamentals and vocabulary, and the above mentioned ISO/ASTM52900-15.[118][119] In 2023, the ISO/ASTM 52920:2023[257] defined the requirements for industrial additive manufacturing processes and production sites using additive manufacturing to ensure required quality level. Aforetime in Germany there was a draft of DIN norm issued, DIN SPEC 17071:2019.

Health and safety

[edit]Polymer feedstock materials can release ultrafine particles and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) if sufficiently heated, which in combination have been associated with adverse respiratory and cardiovascular health effects. In addition, temperatures of 190 °C to 260 °C are typically reached by an FFF extrusion nozzle, which can cause skin burns. Vat photopolymerization stereolithography printers use high-powered lasers that present a skin and eye hazard, although they are considered nonhazardous during printing because the laser is enclosed within the printing chamber.[258]

3D printers also contain many moving parts that include stepper motors, pulleys, threaded rods, carriages, and small fans, which generally do not have enough power to cause serious injuries but can still trap a user's finger, long hair, or loose clothing. Most desktop FFF 3D printers do not have any added electrical safety features beyond regular internal fuses or external transformers, although the voltages in the exposed parts of 3D printers usually do not exceed 12V to 24V, which is generally considered safe.[258]

Research on the health and safety concerns of 3D printing is new and in development due to the recent proliferation of 3D printing devices. In 2017, the European Agency for Safety and Health at Work published a discussion paper on the processes and materials involved in 3D printing, the potential implications of this technology for occupational safety and health and avenues for controlling potential hazards.[259]

Noise level is measured in decibels (dB), and can vary greatly in home printers from 15 dB to 75 dB.[260] Some main sources of noise in filament printers are fans, motors and bearings, while in resin printers the fans usually are responsible for most of the noise.[260] Some methods for dampening the noise from a printer may be to install vibration isolation, use larger diameter fans, perform regular maintenance and lubrication, or use a soundproofing enclosure.[260]

Impact

[edit]Additive manufacturing, starting with today's infancy period, requires manufacturing firms to be flexible, ever-improving users of all available technologies to remain competitive. Advocates of additive manufacturing also predict that this arc of technological development will counter globalization, as end users will do much of their own manufacturing rather than engage in trade to buy products from other people and corporations.[16] The real integration of the newer additive technologies into commercial production, however, is more a matter of complementing traditional subtractive methods rather than displacing them entirely.[261]

The futurologist Jeremy Rifkin[262] claimed that 3D printing signals the beginning of a third industrial revolution,[263] succeeding the production line assembly that dominated manufacturing starting in the late 19th century.

Social change

[edit]

Since the 1950s, a number of writers and social commentators have speculated in some depth about the social and cultural changes that might result from the advent of commercially affordable additive manufacturing technology.[264] In recent years, 3D printing has created a significant impact in the humanitarian and development sector. Its potential to facilitate distributed manufacturing is resulting in supply chain and logistics benefits, by reducing the need for transportation, warehousing and wastage. Furthermore, social and economic development is being advanced through the creation of local production economies.[165]

Others have suggested that as more and more 3D printers start to enter people's homes, the conventional relationship between the home and the workplace might get further eroded.[265] Likewise, it has also been suggested that, as it becomes easier for businesses to transmit designs for new objects around the globe, so the need for high-speed freight services might also become less.[266] Finally, given the ease with which certain objects can now be replicated, it remains to be seen whether changes will be made to current copyright legislation so as to protect intellectual property rights with the new technology widely available.

Some call attention to the conjunction of commons-based peer production with 3D printing and other low-cost manufacturing techniques.[267][268][269] The self-reinforced fantasy of a system of eternal growth can be overcome with the development of economies of scope, and here, society can play an important role contributing to the raising of the whole productive structure to a higher plateau of more sustainable and customized productivity.[267] Further, it is true that many issues, problems, and threats arise due to the democratization of the means of production, and especially regarding the physical ones.[267] For instance, the recyclability of advanced nanomaterials is still questioned; weapons manufacturing could become easier; not to mention the implications for counterfeiting[270] and on intellectual property.[271] It might be maintained that in contrast to the industrial paradigm whose competitive dynamics were about economies of scale, commons-based peer production 3D printing could develop economies of scope. While the advantages of scale rest on cheap global transportation, the economies of scope share infrastructure costs (intangible and tangible productive resources), taking advantage of the capabilities of the fabrication tools.[267] And following Neil Gershenfeld[272] in that "some of the least developed parts of the world need some of the most advanced technologies", commons-based peer production and 3D printing may offer the necessary tools for thinking globally but acting locally in response to certain needs.