Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Akron, Ohio

View on Wikipedia

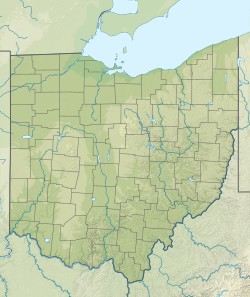

Akron (/ˈækrən/) is a city in Summit County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. It is the fifth-most populous city in Ohio, with a population of 190,469 at the 2020 census. The Akron metropolitan area has an estimated 702,000 residents.[4] Akron is located on the western edge of the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau in Northeast Ohio, about 40 miles (64 km) south of downtown Cleveland.

Key Information

First settled in 1810, the city was founded by Simon Perkins and Paul Williams in 1825 along the Little Cuyahoga River at the summit of the developing Ohio and Erie Canal.[5]

Its name is derived from the Greek word ἄκρον (ákron), signifying a summit or high point. It was briefly renamed South Akron after Eliakim Crosby founded nearby North Akron in 1833, until both merged into an incorporated village in 1836.

In the 1910s, Akron doubled in population, making it the nation's fastest-growing city. A long history of rubber and tire manufacturing, carried on today by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, gave Akron the nickname "Rubber Capital of the World". It was once known as a center of airship development.[6][7] Today, its economy includes manufacturing, education, healthcare, and biomedical research; leading employers include Akron Children's Hospital, Gojo Industries, FirstEnergy, and Summa Health. Other significant institutions include the Akron Art Museum, Akron Civic Theatre, Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens, and University of Akron.

Notable historic events in Akron include the passage of the Akron School Law of 1847, which created the K–12 system; the popularization of the church architectural Akron Plan, the foundation of Alcoholics Anonymous, the Akron Experiment into preventing goiters with iodized salt, the 1983 Supreme Court case City of Akron v. Akron Center for Reproductive Health; and portions of the 2014 Gay Games.

A racially diverse city, Akron saw noted racial relations speeches by Sojourner Truth in 1851 (the Ain't I A Woman? speech), W. E. B. Du Bois in 1920,[8] and President Bill Clinton in 1997.[9] Major episodes of civil unrest in Akron have included the riot of 1900, rubber strike of 1936, the Wooster Avenue riots of 1968, and the 2022 protests surrounding the killing of Jayland Walker.

History

[edit]

The first settler in the Akron area was Major Miner Spicer,[10] who came from Groton, Connecticut. He built a log cabin in the forest in 1810, and became the region's first citizen.[5] In June 1811, Spicer sent for his family, who came that same year by ox teams accompanied by Capt. Amos Spicer and Paul Williams.[11]

In 1811, Paul Williams settled near the corner of what is now Buchtel Avenue and Broadway. He suggested to General Simon Perkins, who was surveyor of the Connecticut Land Company's Connecticut Western Reserve, that they found a town at the summit of the developing Ohio and Erie Canal. The name is adapted from the Greek word ἄκρον (ákron), meaning summit or high point.[12] It was laid out in December 1825, where the south part of the downtown Akron neighborhood sits today. Irish laborers working on the Ohio Canal built about 100 cabins nearby.

After Eliakim Crosby founded "North Akron" (also known as Cascade) in the northern portion of what is now downtown Akron in 1833, "South" was added to Akron's name until about three years later, when the two were merged and became an incorporated village in 1836.[13] In 1840, Summit County formed from portions of Portage, Medina, and Stark Counties. Akron replaced Cuyahoga Falls as its county seat a year later and opened a canal connecting to Beaver, Pennsylvania, helping give birth to the stoneware, sewer pipe, fishing tackle, and farming equipment industries.[6][7] In 1844, abolitionist John Brown moved into the John Brown House across the street from business partner Colonel Simon Perkins, who lived in the Perkins Stone Mansion. The Akron School Law of 1847 founded the city's public schools and created the K–12 grade school system,[14] which currently is used in every U.S. state. The city's first school is now a museum on Broadway Street near the corner of Exchange.

1850s–1890s: Summit City

[edit]When the Ohio Women's Rights Convention came to Akron in 1851, Sojourner Truth extemporaneously delivered her speech named "Ain't I A Woman?", at the Universalist Old Stone Church. In 1870, a local businessman associated with the church, John R. Buchtel, founded Buchtel College, which became the University of Akron in 1913.

Ferdinand Schumacher bought a mill in 1856, and the following decade mass-produced oat bars for the Union Army during the American Civil War; these continued to sell well after the war. Akron incorporated as a city in 1865.[citation needed] Philanthropist Lewis Miller, Walter Blythe, and architect Jacob Snyder designed the widely used Akron Plan, debuting it on Akron's First Methodist Episcopal Church in 1872.[15] Numerous Congregational, Baptist, and Presbyterian churches built between the 1870s and World War I use it.[16][17] In 1883, a local journalist began the modern toy industry by founding the Akron Toy Company. A year later, the first popular toy was mass-produced clay marbles made by Samuel C. Dyke at his shop where Lock 3 Park is now. Other popular inventions include rubber balloons, ducks, dolls, balls, baby buggy bumpers, and little brown jugs. In 1895, the first long-distance electric railway, the Akron, Bedford and Cleveland Railroad, began service.[18] On August 25, 1889, the Boston Daily Globe referred to Akron with the nickname "Summit City".[19] To help local police, the city deployed the first police car in the U.S. that ran on electricity.[20]

1900s–1990s: Rubber Capital of the World

[edit]

The Riot of 1900 saw assaults on city officials, two deaths, and the destruction by fire of Columbia Hall and the Downtown Fire Station (now the City Building since 1925).[21] The American trucking industry was birthed through Akron's Rubber Capital of the World era when the four major tire companies B.F. Goodrich (1869), Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company (1898), Firestone Tire and Rubber Company (1900),[22] and General Tire & Rubber Company (1915)[23][24] were headquartered in the city. The numerous jobs the rubber factories provided for deaf people led to Akron being nicknamed the "Crossroads of the Deaf".[25] On Easter Sunday 1913, 9.55 inches (243 mm) of rain fell, causing floods that killed five people and destroyed the Ohio and Erie Canal system. From 1916 to 1920, 10,000 schoolgirls took part in the successful Akron Experiment, testing iodized salt to prevent goiter in what was known as the "Goiter Belt".[26]

In 1914, Marcus Garvey founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association in Kingston, Jamaica; its Akron branch opened in 1921.[8][27]

Rubber companies responded to housing crunches by building affordable housing for workers. Goodyear's president, Frank A. Seiberling, built the Goodyear Heights neighborhood for employees. Likewise, Harvey S. Firestone built the Firestone Park neighborhood for his employees.[28] During the 1910–1920 decade, Akron became a boomtown, being America's fastest growing city with a 201.8% increase in population. Of the 208,000 citizens, almost one-third were immigrants (also Clark Gable)[29] and their children from places including Europe and West Virginia. In 1929 and 1931, Goodyear's subsidiary Goodyear-Zeppelin Company manufactured two airships for the United States Navy, USS Akron (ZRS-4) and USS Macon (ZRS-5). Goodyear built a number of blimps for the Navy during WWII and later for advertising purposes.[30][31][32]

Akron again grew when Kenmore was annexed by voter approval on November 6, 1928. Found hiding under a bed at one of his hideouts in the city, notorious bank robber Charles Arthur "Pretty Boy" Floyd was arrested under the name "Frank Mitchell" in March 1930.[33] Goodyear became America's top tire manufacturer after merging with the Kelly-Springfield Tire Company in 1935.[34] Lasting five weeks and consisting of roughly 5,000 strikers including union sympathizers from other factories and neighboring states, the Akron Rubber Strike of 1936 successfully used the "sit-down" tactic to force recognition of the United Rubber Workers.[35] During the 1950s–60s Akron surged as use of the automobile did. The historic Rubber Bowl was used by the National Guard of the United States as a base during the racial Wooster Avenue Riots of 1968. Like many other industries of the Rust Belt, both the tire and rubber industries experienced major decline. By the early 1990s, Goodyear was the last major tire manufacturer based in Akron.

2000s: City of Invention

[edit]

Despite the number of rubber workers decreasing by roughly half from 2000 to 2007, Akron's research in polymers gained an international reputation.[36] It now centers on the Polymer Valley which consists of 400 polymer-related companies, of which 94 were located in the city itself.[37] Research is focused at the University of Akron, which is home to the Goodyear Polymer Center and the National Polymer Innovation Center, and the College of Polymer Science and Polymer Engineering. Because of its contributions to the Information Age, Newsweek listed Akron fifth of ten high-tech havens in 2001.[37] In 2008 "City of Invention" was added to the seal when the All-America City Award was received for the third time. Akron received the award again in 2025.[38] Some events of the 2014 Gay Games used the city as a venue. In 2013, the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company opened its new global headquarters on Innovation Way, further cementing the company's relationship with the city.[39] Bridgestone built a new technical center with state-of-the-art R&D labs, and moved its product development operations to the new facility in early 2012.[40][41]

The city also continues to deal with the effects of air and soil pollution from its industrial past. In the southwestern part of the city, soil was contaminated and noxious PCB-laden fumes were put into the air by an electrical transformer deconstruction operation that existed from the 1930s to the 1960s. Cleanup of the site, designated as a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency, began in 1987 and concluded in 2000. The area remains restricted with regular reviews of the site and its underground aquifer.[42][43][44]

Racial history

[edit]City founder Simon Perkins negotiated a treaty with Native Americans to establish a mail route from the Connecticut Western Reserve to Detroit in 1807, an early example of historic humanitarian affairs in Akron. Aside from being part of the Underground Railroad, when active, John Brown was a resident, today having two landmarks (the John Brown House and the John Brown Monument) dedicated to him. During the 1851 Women's Rights Convention, Sojourner Truth delivered her speech entitled "Ain't I A Woman?". In 1905, a statue of an Indian named Unk was erected on Portage Path, which was part of the effective western boundary of the White and Native American lands from 1785 to 1805.[45] The Summit County chapter of the Ku Klux Klan reported having 50,000 members, making it the largest local chapter in the country during the 20th century. At some point the sheriff, county officials, mayor of Akron, judges, county commissioners, and most members of Akron's school board were members. The Klan's influence in the city's politics eventually ended after Wendell Willkie arrived and challenged them.[46] Race played a part in two of Akron's major riots, the Riot of 1900 and the Wooster Ave. Riots of 1968. Others giving speeches on race in the city include W. E. B. Du Bois (1920)[8] and President Bill Clinton (1997).[9] In 1971, Alpha Phi Alpha Homes Inc. was founded in Akron by the Eta Tau Lambda chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, with James R. Williams as chairman. The centerpiece, Henry Arthur Callis Tower, is located in the Channelwood Village area of the city. In 2008, 91-year-old Akron native, Addie Polk, became the poster child of the Great Recession, after shooting herself.[47] In 2022, Akron resident Jayland Walker was killed by police after shooting at them while fleeing, sparking days of protest and the institution of a police review board.

Geography

[edit]Akron is located in the Great Lakes region about 39 miles (63 km) south of Lake Erie, on the Glaciated Allegheny Plateau. It is bordered by Cuyahoga Falls on the north and Barberton in the southwest. It is the center of the Akron metropolitan area which covers Summit and Portage Counties, and a principal city of the larger Cleveland–Akron–Canton Combined Statistical Area. Located on the western end of the plateau, the topography of Akron includes rolling hills and varied terrain. The Ohio and Erie Canal passes through the city, separating the east from west. Akron has the only biogas facility[48] in the United States that produces methane through the decomposition process of sludge to create electricity.[49] According to the 2010 census, the city has a total area of 62.37 square miles (161.5 km2), of which 62.03 square miles (160.7 km2) (or 99.45%) is land and 0.34 square miles (0.88 km2) (or 0.55%) is water.[50]

Climate

[edit]Akron has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), typical of the Midwest, with four distinct seasons, and lies in USDA hardiness zone 6b, degrading to zone 6a in the outlying suburbs.[51] Winters are cold and dry but typically bring a mix of rain, sleet, and snow with occasional heavy snowfall and icing. January is the coldest month with an average mean temperature of 27.9 °F (−2.3 °C),[52] with temperatures on average dropping to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on 3.3 days and staying at or below freezing on 40 days per year.[52] Snowfall averages 47.2 inches (120 cm) per season, significantly less than the snowbelt areas closer to Lake Erie.[52] The snowiest month on record was 37.5 inches (95 cm) in January 1978, while winter snowfall amounts have ranged from 82.0 in (208 cm) in 1977–78 to 18.2 in (46 cm) in 1949–50.[52] Springs generally see a transition to fewer weather systems that produce heavier rainfall. Summers are typically very warm and humid with temperatures at or above 90 °F (32 °C) on 10.7 days per year on average; the annual count has been as high as 36 days in 1931, while the most recent year to not reach that mark is 2023.[52] July is the warmest month with an average mean temperature of 73.9 °F (23 °C).[52] Autumn is relatively dry with many clear warm days and cool nights.

The all-time record high temperature in Akron of 104 °F (40 °C) was established on August 6, 1918, and the all-time record low temperature of −25 °F (−32 °C) was set on January 19, 1994.[52] The most precipitation to fall on one calendar day was on July 7, 1943, when 5.96" of rain was measured.[52] The first and last freezes of the season on average fall on October 21 and April 26, respectively, allowing a growing season of 174 days.[52] The normal annual mean temperature is 51.7 °F (10.9 °C).[52] Normal yearly precipitation based on the 30-year average from 1991 to 2020 is 41.57 inches (1,056 mm), falling on an average 160 days.[52] Monthly precipitation has ranged from 12.55 in (319 mm) in July 2003 to 0.19 in (4.8 mm) in August 2025, while for annual precipitation the historical range is 65.70 in (1,669 mm) in 1990 to 23.79 in (604 mm) in 1963.[52]

| Climate data for Akron, Ohio (Akron–Canton Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1887–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

76 (24) |

83 (28) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

91 (33) |

80 (27) |

76 (24) |

104 (40) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 58.2 (14.6) |

60.0 (15.6) |

70.7 (21.5) |

79.8 (26.6) |

85.8 (29.9) |

90.5 (32.5) |

91.6 (33.1) |

90.4 (32.4) |

87.7 (30.9) |

79.1 (26.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

59.4 (15.2) |

92.7 (33.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 35.5 (1.9) |

38.6 (3.7) |

48.4 (9.1) |

61.8 (16.6) |

72.3 (22.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

84.3 (29.1) |

82.7 (28.2) |

75.9 (24.4) |

63.4 (17.4) |

50.7 (10.4) |

39.9 (4.4) |

61.2 (16.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

38.9 (3.8) |

50.8 (10.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

69.9 (21.1) |

73.9 (23.3) |

72.3 (22.4) |

65.4 (18.6) |

53.7 (12.1) |

42.5 (5.8) |

33.0 (0.6) |

51.7 (10.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.3 (−6.5) |

21.9 (−5.6) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

39.8 (4.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

59.4 (15.2) |

63.4 (17.4) |

61.9 (16.6) |

54.9 (12.7) |

44.0 (6.7) |

34.2 (1.2) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

42.1 (5.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −1.1 (−18.4) |

3.0 (−16.1) |

10.9 (−11.7) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

35.4 (1.9) |

44.4 (6.9) |

52.1 (11.2) |

50.6 (10.3) |

40.9 (4.9) |

30.4 (−0.9) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

8.5 (−13.1) |

−3.4 (−19.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−20 (−29) |

−6 (−21) |

10 (−12) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

39 (4) |

29 (−2) |

20 (−7) |

−1 (−18) |

−16 (−27) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.92 (74) |

2.44 (62) |

3.23 (82) |

3.86 (98) |

4.13 (105) |

4.43 (113) |

4.14 (105) |

3.61 (92) |

3.50 (89) |

3.34 (85) |

3.08 (78) |

2.89 (73) |

41.57 (1,056) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 13.4 (34) |

12.0 (30) |

7.6 (19) |

1.7 (4.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

3.3 (8.4) |

8.9 (23) |

47.2 (120) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 17.8 | 14.5 | 14.2 | 14.6 | 14.1 | 12.4 | 11.8 | 10.1 | 9.9 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 16.0 | 159.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 13.3 | 10.0 | 6.7 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 9.5 | 45.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.4 | 71.6 | 67.8 | 63.6 | 65.9 | 68.4 | 70.2 | 73.2 | 73.9 | 70.3 | 72.2 | 74.8 | 70.4 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 17.2 (−8.2) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

35.2 (1.8) |

46.2 (7.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

60.6 (15.9) |

60.3 (15.7) |

54.0 (12.2) |

41.7 (5.4) |

32.9 (0.5) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

39.4 (4.1) |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and dew point 1961-1990)[53][54] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

[edit]Akron consists of 21 neighborhoods, with an additional three that are unincorporated but recognized within the city. The neighborhoods of the city differ in design largely because of expansions such as town merging, annexation, housing construction in various time periods, and rubber era.

Maple Valley covers the west end of Copley Road, before reaching I-77. Along this strip are several businesses using the name, as well as the Maple Valley Branch of the Akron-Summit County Public Library. Spicertown falls under the blanket of University Park, this term is used frequently to describe the student-centered retail and residential area around East Exchange and Spicer streets, near the University of Akron. West Hill is roughly bounded by West Market Street on the north, West Exchange Street on the south, Downtown on the East, and Rhodes Avenue on the west. It features many stately older homes, particularly in the recently recognized Oakdale Historic District.

Suburbs

[edit]Akron's suburbs include Barberton, Cuyahoga Falls, Fairlawn, Green, Hudson, Mogadore, Montrose-Ghent, Munroe Falls, Norton, Silver Lake, Stow, and Tallmadge. Akron formed Joint Economic Development Districts with Springfield, Coventry, Copley, and Bath (in conjunction with Fairlawn) townships.[55]

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 1,664 | — | |

| 1850 | 3,266 | 96.3% | |

| 1860 | 3,477 | 6.5% | |

| 1870 | 10,006 | 187.8% | |

| 1880 | 16,512 | 65.0% | |

| 1890 | 27,601 | 67.2% | |

| 1900 | 42,728 | 54.8% | |

| 1910 | 69,067 | 61.6% | |

| 1920 | 208,435 | 201.8% | |

| 1930 | 255,040 | 22.4% | |

| 1940 | 244,791 | −4.0% | |

| 1950 | 274,605 | 12.2% | |

| 1960 | 290,351 | 5.7% | |

| 1970 | 275,425 | −5.1% | |

| 1980 | 237,177 | −13.9% | |

| 1990 | 223,019 | −6.0% | |

| 2000 | 217,074 | −2.7% | |

| 2010 | 199,110 | −8.3% | |

| 2020 | 190,469 | −4.3% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 189,664 | [3] | −0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[56][3] | |||

According to census data from 2010 to 2014, the median income for a household in the city was $34,139. The per capita income for the city was $17,596. About 26.7% of persons were in poverty.[57]

The population of the Akron metropolitan area was 702,219 in 2020. Akron is also part of the larger Cleveland-Akron-Canton combined statistical area, which was the 15th largest in the country with a population of over 3.5 million residents. Akron experienced a significant collapse in population having lost over one third (34.6%) of its population between 1960 and 2020.

Although Akron is in northern Ohio, where the Inland North dialect is expected, its settlement history puts it in the North Midland dialect area.[58] Some localisms that have developed include devilstrip, which refers to the grass strip between a sidewalk and street.[59]

2020 census

[edit]| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[60] | Pop 2010[61] | Pop 2020[62] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 144,719 | 121,946 | 102,825 | 66.67% | 61.25% | 53.99% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 61,510 | 62,095 | 59,286 | 28.34% | 31.19% | 31.13% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 526 | 425 | 356 | 0.24% | 0.21% | 0.19% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 3,232 | 4,201 | 10,042 | 1.49% | 2.11% | 5.27% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 40 | 49 | 73 | 0.02% | 0.02% | 0.04% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 365 | 448 | 1,017 | 0.17% | 0.23% | 0.53% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 4,169 | 5,691 | 10,674 | 1.92% | 2.86% | 5.60% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 2,513 | 4,255 | 6,196 | 1.16% | 2.14% | 3.25% |

| Total | 217,074 | 199,110 | 190,469 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the census of 2020, there were 190,469 people living in the city, for a population density of 3,075.40 people per square mile (1,187.42/km2). There were 92,517 housing units. The racial makeup of the city (including Hispanics in the racial counts) was 54.7% White, 31.4% African American, 0.3% Native American, 5.3% Asian, 0.0% Pacific Islander, 1.6% from some other race, and 6.6% from two or more races. Separately, 3.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[63]

There were 85,395 households, out of which 28.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 27.3% were married couples living together, 23.8% had a male householder with no spouse present, and 39.8% had a female householder with no spouse present. 38.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.0% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16, and the average family size was 2.86.[63]

22.1% of the city's population were under the age of 18, 61.6% were 18 to 64, and 16.3% were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36.5. For every 100 females, there were 93.8 males.[63]

According to the U.S. Census American Community Survey, for the period 2016-2020 the estimated median annual income for a household in the city was $45,534, and the median income for a family was $52,976. About 24.4% of the population were living below the poverty line, including 35.0% of those under age 18 and 12.9% of those age 65 or over. About 57.1% of the population were employed, and 24.8% had a bachelor's degree or higher.[63]

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[64] of 2010, there were 199,110 people, 83,712 households, and 47,084 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,209.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,239.3/km2). There were 96,288 housing units at an average density of 1,552.3 per square mile (599.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 62.2% White, 31.5% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 0.8% from other races, and 3.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.1% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 61.2% of the population,[65] down from 81.0% in 1970.[66]

There were 83,712 households, of which 28.8% had children under age 18 living with them, 31.3% were married couples living together, 19.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.8% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.98.

The median age in the city was 35.7 years. 22.9% of residents were under age 18; 12.4% were between 18 and 24; 25.9% were from 25 to 44; 25.9% were from 45 to 64; and 12.6% were 65 or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.3% male and 51.7% female.

Crime

[edit]

In 1999, Akron ranked as the 94th-most-dangerous city (and the 229th safest) on the 7th Morgan Quitno list.[67] Preliminary Ohio crime statistics show aggravated assaults increased by 45% during 2007.[68]

Historically, organized crime operated in the city with the presence of the Black Hand led by Rosario Borgio, once headquartered on the city's north side in the first decade of the 20th century[citation needed] and the Walker-Mitchell mob, of which Pretty Boy Floyd was a member.[69] Akron has experienced several riots in its history, including the Riot of 1900 and the Wooster Avenue Riots of 1968.

The distribution of methamphetamine ("meth") in Akron greatly contributed to Summit County becoming known as the "Meth Capital of Ohio" in the early 2000s.[70] The county ranked third in the nation in the number of registered meth sites.[71] During the 1990s, motorcycle gang the Hells Angels sold the drug from bars frequented by members.[72] Between January 2004 and August 2009, the city had significantly more registered sites than any other city in the state.[73] Authorities believed a disruption of a major Mexican meth operation contributed to the increase of it being made locally.[74] In 2007, the Akron Police Department (APD) received a grant to help continue its work with other agencies and jurisdictions to support them in ridding the city of meth labs.[75] The APD coordinates with the Summit County Drug Unit and the Drug Enforcement Administration, forming the Clandestine Methamphetamine Laboratory Response Team.[76]

Economy

[edit]

After beginning the tire and rubber industry during the 20th century with the founding of Goodrich Corporation, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, General Tire, and the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company merger with Kelly-Springfield Tire Company, Akron gained the nickname of "Rubber Capital of the World". Akron has won economic awards such as for City Livability and All-America City, and deemed a high tech haven greatly contributing to the Information Age.[77] Current Fortune 500 companies headquartered in the city include Goodyear and FirstEnergy. In addition, the city is the headquarters to GOJO, Advanced Elastomer Systems, Babcock & Wilcox, Myers Industries, Acme Fresh Market, and Sterling Jewelers. Goodyear built a new world headquarters in the city in 2013.[78][79] Bridgestone built a new technical center with research and development labs, and moved its product development operations to the new facility in early 2012.[40][41] The Eastern Ohio division of KeyBank, which has six branches in the city, built a regional headquarters downtown.[80]

Polymer Valley

[edit]Northeast Ohio's Polymer Valley is centered in Akron. The area holds forty-five percent of the state's polymer industries, with the oldest dating to the 19th century. During the 1980s and 1990s, an influx of new polymer companies came to the region.[81] In 2001, more than 400 companies manufactured polymer-based materials in the region.[82] Many University of Akron scientists became world-renowned for their research done at the Goodyear Polymer Center.[83] The first College of Polymer Science and Polymer Engineering was begun by the university. In 2010, the National Polymer Innovation Center opened on campus.

Hospitals

[edit]

Akron has designated an area called the Biomedical Corridor, aimed at luring health-related ventures to the region. It encompasses 1,240 acres (5.0 km2) of private and publicly owned land, bounded by Akron General on the west and Akron City on the east, and also includes Akron Children's near the district's center with the former Saint Thomas Hospital to the north of its northern boundaries.[84] Since its start in 2006, the corridor added the headquarters of companies such as Akron Polymer Systems.[85]

Akron's adult hospitals are owned by two health systems, Summa Health System and Akron General Health System. Summa Health System operates Summa Akron City Hospital and the former St. Thomas Hospital, which in 2008 were recognized for the 11th consecutive year as one of "America's Best Hospitals" by U.S. News & World Report.[86][87] Summa is recognized as having one of the best orthopaedics programs in the nation with a ranking of 28th.[88] Akron General Health in affiliation with the Cleveland Clinic operates Akron General Medical Center, which in 2009, was recognized as one of "America's Best Hospitals" by U.S. News & World Report.[89][90] Akron Children's Hospital is an independent entity that specializes in pediatric care and burn care.[91] In 1974, Howard Igel and Aaron Freeman successfully grew human skin in a lab to treat burn victims, making Akron Children's Hospital the first hospital in the world to achieve such a feat.[92] Akron City and Akron General hospitals are designated Level I Trauma Centers.

Top employers

[edit]According to the city's 2020 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[93] the principal employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Summa Health System | 8,609 |

| 2 | University of Akron | 5,933 |

| 3 | Akron Children's Hospital | 5,773 |

| 4 | FirstEnergy | 5,538 |

| 5 | Cleveland Clinic- Akron General | 4,779 |

| 6 | Akron Public Schools | 4,544 |

| 7 | Summit County | 3,323 |

| 8 | Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company | 2,954 |

| 9 | City of Akron | 2,406 |

| 10 | Signet Jewelers | 2,094 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

Akron is home to E. J. Thomas Hall, one of three Akron performance halls. Regular acts include the Akron Symphony Orchestra, Tuesday Musical Club, and Children's Concert Society. World-class performance events include Broadway musicals, ballets, comedies, lectures, and entertainers attracting 400,000 visitors annually.[citation needed] The hall seats 2,955, divided among three tiers. Located downtown is the Akron Civic Theatre, a movie palace which opened in 1929 and contains many Moorish features, including arches and decorative tiles.[94] The theater seats 5,000. Lock 3, a historic Ohio and Erie Canalway landmark, has been transformed into an entertainment amphitheater that hosts festivals, concerts, and community events throughout the year. In Highland Square, Akron hosts a convergence of art, music, and community annually called Art in the Square, a festival featuring local artists and musicians.[95]

The downtown Akron Art Museum features art produced since 1850 along with national and international exhibitions.[96] It opened in 1922 as the Akron Art Institute, in the basement of the Akron Public Library. It moved to its current location at the renovated 1899 post office building in 1981. In 2007, the museum more than tripled in size with the addition of the John S. and James L. Knight Building, which received the 2005 American Architecture Award from the Chicago Athenaeum[97] while still under construction.[98][99]

The Akron Zoo is located just outside downtown and was an initial gift of property from the city's founding family.[100] Built between 1912 and 1915 for Goodyear Tire & Rubber co-founder Frank Seiberling, Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens is the seventh-largest historic house in the United States. It hosts various attractions and public events throughout the year. Akron is home to the American Marble and Toy Museum.[101]

National events hosted annually in Akron cover a wide variety of hobbies and interests. The PGA World Golf Championships travel to Akron each year for the Bridgestone Invitational at Firestone Country Club. The All-American Soap Box Derby is a youth racing program which has its World Championship finals at Derby Downs. In mid July, the National Hamburger Festival consists of different vendors serving original recipe hamburgers and has a Miss Hamburger contest.[102] Lock 3 Park annually hosts the First Night Akron celebration on New Year's Eve.[103] The park also annually hosts the Italian Festival and the "Rib, White & Blue" food festival in July.[95] Founders Day is celebrated annually because of the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous within the city. The Dr. Robert Smith House is located in Akron.[104][105]

Architecture

[edit]

As a result of multiple towns merging, and industry boom, Akron's architecture is diverse. Originally a canal town, the city is divided into two parts by the Ohio and Erie Canal, with downtown being centered on it. Along the locks, the city has a path paved with rubber. The contrasting neighborhoods of Goodyear Heights and Firestone Park were built during the rubber industry to house workers and their families. Both are communities filled with houses based on mail-order plans.[citation needed] In 2009, the National Arbor Day Foundation designated Akron as a Tree City USA for the 14th time.[106]

Many of the city's government and civic buildings, including City Hall and the Summit County Courthouse are from pre-World War Two, but the Akron-Summit County Public Library, and John S. Knight Center are considerably newer. The library originally opened in 1969, but reopened as a greatly expanded facility in 2004. The Knight Center opened in 1994.

The First Methodist Episcopal Church first used the Akron Plan in 1872. The plan later gained popularity, being used in many Congregationalist, Baptist, and Presbyterian church buildings.[15][107]

Completed in 1931, Akron's tallest building, the Huntington Tower features the art deco style and is covered in glazed architectural terra-cotta.[108] Standing 330 feet (100 m) tall, it is built on top of the Hamilton Building, completed in 1900 in the neo-Gothic style.[citation needed] Near the turn of the millennium the tower was given a $2.5 million facelift, including a $1.8 million restoration of the tower's terra-cotta, brick, and limestone.[108] The top of the building has a television broadcast tower formerly used by WAKR-TV (now WVPX-TV) and WAKR-AM.[109] Located on the University of Akron campus, the Goodyear Polymer Center consists of glass twin towers connected by walkways. The university also formerly used the old Quaker Oats factory as a dormitory, including using it as a quarantine center during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. For many years it had been a shopping center called Quaker Square. There had also been a hotel there.

The Akron Art Museum commissioned Coop Himmelblau to design an expansion in 2007. The new building connects to the old building and is divided into three parts known as the "Crystal",[110] the "Gallery Box",[111] and the "Roof Cloud".[112]

Akron is home to the 70 acre National Historic Landmark Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens, a historic steel frame house and gardens that includes the seventh-largest house in the United States, was the home of Frank Seiberling, co-founder of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, and is now a museum.[113][114][115]

Cuisine

[edit]Several residents of Akron have played a role in defining American cuisine. Ferdinand Schumacher created the first American oatmeal and is a pioneer of breakfast cereal.[116] He also founded the Empire Barley Mill and German Mills American Oatmeal Company,[117] which would later merge several times with other companies, with the result being the Quaker Oats Company.[118] The Menches Brothers, are the disputed inventors of the waffle ice cream cone,[119] caramel corn,[119] and hamburger.[120] Strickland's Frozen Custard is located in Akron.

Sports

[edit]| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akron RubberDucks | Baseball | Eastern League (AA) | 7 17 Credit Union Park (7,630) | 5,074 |

| Akron Aviators | Basketball | American Basketball Association | Innes Community Learning Center | |

| Akron City FC | Soccer | National Premier Soccer League (Rust Belt Conference) | Green Street Stadium (3,000) | 625 |

| Akron Zips football | American football | Mid-American Conference (NCAA) | InfoCision Stadium (30,000) | 18,098 |

| Akron Zips men's basketball | Basketball | Mid-American Conference (NCAA) | James A. Rhodes Arena (5,500) | 3,351 |

| Akron Zips men's soccer | Soccer | Big East (NCAA) | FirstEnergy Stadium (4,000) | 2,186 |

The Akron RubberDucks baseball team moved to Akron from Canton in 1997 and have won the Eastern League Championship six times, most recently in 2021. The Akron Marathon is an annual marathon in the city which offers a team relay and shorter races throughout the summer and fall.[121] The All-American Soap Box Derby takes place each year at the Derby Downs since 1936. LeBron James' King for Kids bike-a-thon feature James riding with kids through the city each June.[122] In November, the city hosts the annual Home Run for the Homeless 4-mile run. Akron hosted some of the events of the 2014 Gay Games including the marathon, the men's and women's golf tournaments at Firestone Country Club, and softball at Firestone Stadium.[123]

The University of Akron's Akron Zips compete in the NCAA and the Mid-American Conference (MAC) in a variety of sports at the Division I level. The men's basketball team appeared in the NCAA Tournament in 1986, 2009, 2011, and 2013. In 2009, the Zips men's soccer team completed the regular-season undefeated, then won the NCAA Men's Division I Soccer Championship in 2010. Zippy, one of the eight female NCAA mascots, won the National Mascot of the Year contest in 2007.

Former teams of Akron include the Akron Professionals of the National Football League who played in the historic Rubber Bowl and won the 1920 championship; the Goodyear Silents, a deaf semi-professional football; the Akron Black Tyrites of the Negro National League; the Akron Americans of the International Hockey League; the Akron Lightning of the International Basketball League; the Akron Summit Assault of the USL Premier Development League, the fourth tier of the American Soccer Pyramid; the Akron Wingfoots of the National Basketball League, who won the first NBL Championship and the International Cup three times; the Akron Firestone Non-Skids, also of the National Basketball League, who won the title consecutively, in 1939 and 1940; and the Akron Vulcans, a professional football team that played in the Continental Football League for part of the 1967 season.[124] Akron had 2 teams who won the National Basketball League in the '30s and '40s, before the foundation of the NBA.

The Firestone Country Club, which annually hosted the WGC-Bridgestone Invitational, has in the past hosted the PGA Championship, American Golf Classic, and Rubber City Open Invitational. On January 7, 1938, Akron became the birthplace of women's professional Mud Wrestling, in a match including Professional Wrestling, WWE, and Wrestling Observer Hall of Famer, Mildred Burke.[125] The Professional Bowlers Association started in the city during 1958.

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Summit Metro Parks is the metroparks system serving Akron. Major parks in Akron include Lock 3, Firestone, Goodyear Heights, the F.A. Seiberling Nature Realm, and part of Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Located within the Sand Run Metro Park, the 104 acres (0.42 km2) F.A. Seiberling Nature Realm features a visitor center, hiking trails, three ponds, gardens, and an array of special programs throughout the year. The Akron Police Museum displays mementos including items from Pretty Boy Floyd, whose gang frequented the city.[126][127]

Several of the parks are along the locks of the Ohio and Erie Canal. Lock 3 Park in downtown Akron features an outdoor amphitheater hosting live music, festivals and special events year-round. The park was created in the early 21st century to provide green space within the city. In the winter, the park is temporarily converted into an outdoor ice-skating rink.[128] Adjacent to the Derby Downs race hill is a 19,000-square-foot (1,800 m2) outdoor skatepark, and nearby is a BMX racing course where organized races are often held in the warmer months. Akron residents can enjoy various ice skating activities year-round at the historic Akron Ice House.

The Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail is a regional bike and hike trail that follows the canal north to Cleveland and south to New Philadelphia, Ohio. The trail features a floating observation deck section over Summit Lake. It is a popular tourist attraction, as it attracts over 2 million visits annually.[129][130][131] The Portage Hike and Bike Trail connects with the hike and bike trails in the county.[132]

Government

[edit]

Biden: 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 80–90% 90–100%

Trump: 40–50% 50–60%

The mayor of Akron is elected in a citywide vote. In 2023, the city elected its 63rd mayor. The city is divided into 10 wards, each elect a member to the Akron City Council, while an additional 3 are elected at large. The mayor's cabinet currently consist of directors and deputy directors of administration, communications, community relations, economic development, intergovernmental relations, labor relations, law, planning & urban development, planning director – deputy, public safety, and public service.[134] The city adopted a new charter of the commissioner manager type in 1920, but reverted to its old form in 1924.

The current mayor is Shammas Malik, who succeeded Dan Horrigan after the 2023 election. Longtime Akron Mayor Don Plusquellic announced on May 8, 2015, that he would resign on May 31 after 28 years as mayor and 41 years of service to the city.[135][136] On May 31, 2015, Garry Moneypenny was sworn in as the new mayor at East High School. Moneypenny was former Chief Deputy and Assistant Sheriff of the Summit County Sheriff's Department, former Springfield Township Police Department Chief of Police,[137] and former Akron City Council President.[136]

On June 5, 2015, less than a week after he took office, Mayor Moneypenny announced he would not run for a full term because of inappropriate contact with a city employee.[138] Three days later, Moneypenny announced he would resign effective at midnight on June 10. Council president Jeff Fusco assumed the duties of mayor on June 11, 2015. Fusco ran for and was elected to an at-large council seat, rather than seeking a full term as mayor. Fusco also announced he would temporarily step down as Chair of the Summit County Democratic Party, because the city charter calls for the Mayor to devote his full attention to the city.[139]

As of July 1, 2015, three Democrats and one Republican were running for Mayor of Akron. The Democratic candidates were Summit County Clerk of Courts and former ward 4 Councilman Dan Horrigan; at-large Councilman Mike Williams; and Summit County Councilman Frank Communale. Horrigan won the Democratic primary, held on September 8. In the general election, he faced the lone GOP candidate, Eddie Sipplen, an African-American criminal defense attorney.[140] On November 3, 2015, Horrigan was elected as the 62nd mayor of the city of Akron. He took office on January 1, 2016. On November 5, 2019, Mayor Horrigan was re-elected to a second term.[141]

The current members of the city council are all Democrats.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]

Preschool, elementary, and secondary education is mainly provided by the Akron City School District. The district's planning began in 1840 when Ansel Miller proposed building free public schools for all children, funded by property taxes. After facing opposition, Miller teamed up with Isaac Jennings, who became chair of a committee to improve the school system. On November 21, 1846, their plan was unanimously approved by citizens, and the Ohio Legislature adopted it as "An Act for the Support and Better Regulation of the Common Schools of the Town of Akron" on February 8, 1847.[142]

Akron's first public schools opened in the fall of 1847 and were led by Mortimer Leggett. he first annual report showed that it cost less than $2 a year to educate a child. By 1857, the annual operating cost had risen to $4,200 (~$111,185 in 2024). Primary schools were taught by young women, who were paid less and supervised by a male superintendent. From 1877 to 1952, Akron graduated students semi-annually instead of annually. In the 1920s, an Americanization program was designed to help the many Akron students who were first-generation Americans.[142] All Akron public schools are going through a 15-year, $800 million rebuilding process.[143] The city's schools have been moved from "Academic Watch" to "Continuous Improvement" by the Ohio Department of Education.[144]

Akron also has many private, parochial and charter schools. As part of his charitable foundation's initiatives in the city, LeBron James founded the I Promise School, which serves underprivileged kids.[145][146][147] Akron was served by the Akron Digital Academy from 2002 to 2018, when it shut down.[148]

The city is home to the University of Akron.[149] Originally Buchtel College, the school is home of the Goodyear Polymer Center and the National Polymer Innovation Center.[150] Part of the University System of Ohio, the university enrolls approximately 15,000 students.[151]

Media

[edit]

Akron was served in print by the daily Akron Beacon Journal, formerly the flagship newspaper of the Knight Newspapers chain; the weekly "The Akron Reporter"; and the weekly West Side Leader newspapers and the monthly magazine Akron Life. The Buchtelite newspaper is published by the University of Akron.[152]

TV

[edit]Akron is part of the Cleveland-Akron-Canton TV market, the 18th largest market in the U.S.[153] Within the market, WEAO (PBS), WVPX (ION), and WBNX-TV (The CW) are licensed to Akron. WEAO serves Akron specifically, while WBNX and WVPX identify as "Akron/Cleveland", serving the entire market. Akron has no native news broadcast, having lost its only news station when the former WAKC became WVPX in 1996. WVPX and Cleveland's WKYC later provided a joint news program, which was cancelled in 2005.[154][155]

Radio

[edit]Though it is part of a combined TV market with Cleveland, Akron is its own radio market, with 12 stations directly serving it, including music stations WQMX 94.9 (Country), WONE 97.5 (Classic rock), WKDD 98.1 (Contemporary Hits), and WAKR 1590/93.5 (Soft AC/Full service).

WHLO 640 and WNIR-FM 100.1 feature news/talk formats, while WCUE 1150 and WKJA 91.9 air religious programming.

As the regional NPR affiliate, WKSU 89.7 serves all of Northeast Ohio (including both the Cleveland and Akron markets).[156] College and school run stations include WZIP 88.1 (Top 40 – University of Akron), WSTB 88.9 (Alternative – Streetsboro City Schools), and WAPS 91.3 (AAA – Akron Public Schools)

Film and television

[edit]Akron has served as the setting for several major studio and independent films. Inducted into the National Film Registry, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940), tells the story of two dancers from Akron who go to New York City.[157][158] My Name is Bill W. (1989) tells the true story of Bill Wilson who co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous, which held its first meetings at the Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens and has over two million members today.[159] The program's connection to the Saint Thomas Hospital is alluded to in an episode of the television series Prison Break (2005), where Michael Scofield talks to Sara Tancredi on the phone while there.[160] The Akron Armory is used as a venue for a female wrestling team in ...All the Marbles (1981).[161] More than a Game (2009) documents National Basketball Association player LeBron James and his St. Vincent – St. Mary High School high school basketball team's journey.[162] In Drake's music video to Forever (2009) off the More than a Game soundtrack (2009), the iconic Goodyear's logo on top the company's theater is shown. The city has been frequently portrayed in media, from "Hell on Earth" in the television series I'm In Hell (2007),[163] to the whereabouts of a holy woman in The Virgin of Akron, Ohio (2007).[164] Henry Spivey of My Own Worst Enemy (2008), travels to Akron through the series many times.[165] George Costanza in an episode of Seinfeld (1989), flies to Akron and has a meeting at Firestone.[166] M.Y.O.B. (2008) is centered on an Akron runaway girl named Riley Veatch.[167] Jake Foley of Jake 2.0 (2003), Pickles family of the Rugrats (1991), and J.Reid of In Too Deep (1999), and Avery Barkley of Nashville (2016) are also from the city. Akron was also in the spotlight on the television show Criminal Minds "Compromising Positions" (2010) Season 6, Episode 4. The 2015 film Room is set in Akron, filmed in Toronto with staging to signify Akron.

Transportation

[edit]Airports

[edit]

The primary terminal that airline passengers traveling to or from Akron use is the Akron–Canton Airport, serving nearly 2 million passengers a year. The Akron-Canton Airport is a commercial Class C airport located in the suburb of Green, Ohio,[168] roughly 10 mi (16 km) southeast of Akron operated jointly by Stark and Summit counties. It serves as an alternative for travelers to or from the Cleveland area as well. Akron Fulton International Airport is a general aviation airport located in and owned by the city that serves private planes. It first opened in 1929 and has operated in several different capacities since then. The airport had commercial scheduled airline service until the 1950s and it is now used for both cargo and private planes.[169] It is home of the Lockheed Martin Airdock, where the Goodyear airships, dirigibles, and blimps were originally stored and maintained. The Goodyear blimps are now housed outside of Akron in a facility on the shores of Wingfoot Lake in nearby Suffield Township.

Railroads

[edit]

Akron Northside Station is a train station at 27 Ridge Street along the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad.[170]

Because of the city's large rubber industry, Akron was once served by a variety of railroads that competed for the city's freight and passenger business. The largest were the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Erie Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Smaller regional railroads included the Akron, Canton, and Youngstown Railroad, Northern Ohio Railway, and the Akron Barberton Belt Railroad.[171][page needed] Today, the city is served by CSX Corporation, the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad, and their subsidiary Akron-Barberton-Cluster, which operate out of the W&LE's Akron Yard near Brittain Road on the eastern end of the city.

From 1891 to 1971 passenger service to points throughout the Midwest, as well as Washington and New York City, was provided at Akron Union Station.[172] The last legacy passenger trains were the Erie Lackawanna's Lake Cities (ended, 1970) and the B&O's Shenandoah (ended, 1971).[173] There is currently no passenger rail transportation with the elimination of Amtrak's former Three Rivers service in 2005. The nearest Amtrak service is in Alliance, Ohio or Cleveland.

Bus and public transit

[edit]

Public transportation is available through the METRO Regional Transit Authority system, whose fleet of over 200 buses and trolleys operates local routes and commuter buses into downtown Cleveland. Stark Area Regional Transit Authority (SARTA) also has a bus line running between Canton and Akron and the Portage Area Regional Transportation Authority (PARTA) runs an express route connecting the University of Akron with Kent State University.[174] Metro RTA operates out of the Robert K. Pfaff Transit Center on South Broadway Street. This facility, which opened in 2009, also houses inter-city bus transportation available through Greyhound Lines.[175]

Freeways

[edit]Akron is served by two major interstate highways that bisect the city. Unlike other cities, the bisection does not occur in the Central Business District, nor do the interstates serve downtown; rather, the Akron Innerbelt and to a lesser extent Ohio State Route 8 serve these functions.

- Interstate 77 connects Marietta and Cleveland, Ohio. In Akron, it has 15 interchanges, four of which permit freeway-to-freeway movements. It runs north–south in the southern part of the city to its intersection with I-76, where it takes a westerly turn as a concurrency with Interstate 76.

- Interstate 76 connects Interstate 71 to Youngstown, Ohio, and farther. It runs east–west and has 18 interchanges in Akron, four of which are freeway-to-freeway. The East Leg was rebuilt in the 1990s to feature six lanes and longer merge lanes. The concurrency with Interstate 77 is eight lanes. The Kenmore Leg is a four-lane leg that is slightly less than two miles (3 km) long and connects to Interstate 277.

- Interstate 277 is an east–west spur that it forms with US 224 after I-76 splits to the north to form the Kenmore Leg. It is six lanes and cosigned with U.S. 224.

- The Akron Innerbelt is a six-lane, 1.78-mile (2.86 km) spur from the I-76/I-77 concurrency and serves the urban core of the city. Its ramps are directional from the interstates, so it only serves west side drivers. ODOT is considering changing this design to attract more traffic to the route. The freeway comes to an abrupt end near the northern boundary of downtown where it becomes Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The freeway itself is officially known as "The Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Freeway". The freeway was originally designed to connect directly to State Route 8, but plans were laid to rest in the mid-1970s because of financial troubles.

- Ohio State Route 8 is an original state highway that is a limited access route that connects Akron's northern suburbs with Interstates 76 and 77. State Route 8's southern terminus is at the central interchange, where it meets I-76 and I-77. The second freeway in Akron to be completed, it went through a major overhaul in 2003 with new ramps and access roads. In 2007 ODOT began a project to upgrade the road to interstate highway standards north of Akron from State Route 303 to I-271, providing a high speed alternative to Cleveland.[176]

Notable people

[edit]

Akron has produced and been home to a number of notable individuals in varying fields. Its natives and residents are called "Akronites". The first postmaster of the Connecticut Western Reserve and president of its bank, General Simon Perkins (1771–1844), co-founded Akron in 1825. His son, Colonel Simon Perkins (1805–1877), while living in Akron during the same time as abolitionist John Brown (1800–1859), went into business with Brown. Wendell Willkie, the Republican nominee for president in 1940, worked in Akron as a lawyer for Firestone. Pioneering televangelist Rex Humbard rose to prominence in Akron. Beacon Journal publisher John S. Knight ran the national Knight Newspapers chain from Akron. Broadcaster Hugh Downs was born in Akron. In the mid- to late 1940s, pioneering rock 'n' roll DJ Alan Freed was musical director at Akron's WAKR. Watergate figure John Dean was born in Akron.

Noted athletes to have come from Akron include multi-time National Basketball Association Champions and MVPs LeBron James and Stephen Curry, Basketball Hall of Famers Gus "Honeycomb" Johnson and Nate "The Great" Thurmond, Major League Baseball player Thurman Munson, International Boxing Hall of Famer Gorilla Jones, WBA Heavyweight Boxing Champion Michael Dokes, Houston Texans linebacker Whitney Mercilus, former Northwestern University and Notre Dame coach Ara Parseghian, and Butch Reynolds, former world record holder in the 400 meter dash. Former NFL linebacker James Harrison was born in Akron, as was former Tennessee Titans head coach and current New England Patriots Head Coach, Mike Vrabel. Clayton Murphy, professional middle-distance runner and 2016 Olympic Games bronze medalist, competed in cross country and track & field for the Akron Zips.

Performing artists to come from Akron include bands such as Ruby and the Romantics; Devo; The Black Keys; The Cramps, whose lead singer, Lux Interior, was a native of the town; rapper Ampichino; The Waitresses; and 1964 the Tribute; singers Vaughn Monroe; Chrissie Hynde, lead singer and main composer with British New Wave band The Pretenders; James Ingram; Joseph Arthur; Jani Lane; Maynard James Keenan, lead singer for Tool, A Perfect Circle, and Puscifer; Rachel Sweet; and outlaw country singer David Allan Coe; Actors Frank Dicopoulos, David McLean, Melina Kanakaredes, Elizabeth Franz, William Boyett, Lola Albright, Ray Wise and Jesse White. Clark Gable and John Lithgow also lived in Akron.

Poet Rita Dove was born and grew up in Akron. She went on to become the first African-American United States Poet Laureate. Many of her poems are about or take place in Akron, foremost among them Thomas and Beulah, which earned her the 1987 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

Owner of over 400 patents, native Stanford R. Ovshinsky invented the widely used nickel-metal hydride battery. Richard Smalley, winner of a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering buckminsterfullerene (buckyballs) was born in the city during 1943. Another native, the second U.S. female astronaut in space, Judith Resnik, died in the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster and has the Resnik Moon crater named in her honor.

The Silver Screen, which came to symbolize Hollywood's movie entertainment industry, was invented by Kenmore resident and projectionist Harry Coulter Williams. First used in Akron's Majestic Theater and then Norka Theater, the "Williams Perlite" tear-proof, vinyl plastic indoor motion picture screen was installed in all the major movie houses, including the rapidly expanding theaters built by Warner Bros. of nearby Youngstown OH. Williams' unique silver-painted screens were adapted for CinemaScope, VistaVision, and later 3-D movies. They provided a brighter picture at all angles with top reflectivity at direct viewing and extra diffusion for side seats and balconies.[177]

Carol Folt, the 11th chancellor and 29th chief executive, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was born in Akron in 1951. She was previously provost (chief academic officer) and interim president of Dartmouth College. She assumed her duties on July 1, 2013, and is the first woman to lead UNC.

The philosopher and logician Willard van Orman Quine was born and grew up in Akron.

In popular culture

[edit]

Thomas and Beulah, a 1986 book of poetry written by native and former Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, Rita Dove, tells the story of her grandmother and grandfather, who separately moved from the South to the city, where they lived through the Great Depression and the rest of their lives.[178] The city is also the setting for the 2005 novel The Coast of Akron, by former editor of Esquire, Adrienne Miller.[179] To reflect Akron's decline during the 1980s, Akron native Chrissie Hynde wrote the 1982 Pretenders song "My City Was Gone".[180] The Black Keys' 2004 album title Rubber Factory refers to the former General Tire & Rubber Company factory in which it was recorded.[181] Akron serves as a setting in the 2002 first-person-shooter PC platform video game No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy In H.A.R.M.'s Way.[182][183]

Sister cities

[edit]Akron, as of 2015, has two sister cities:[184]

|

References

[edit]- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Akron, Ohio

- ^ a b c "Akron city, Ohio". QuickFacts. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ a b First Universalist Church (1904). "Views of Akron, Ohio and Environs" (PDF). p. 4.

- ^ a b "Butler: Clay Products". Akronhistory.org. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Howe, Henry (1896). "Historical collections of Ohio: An encyclopedia of the state: History both general and local, geography with descriptions of its counties, cities and villages, its agricultural, manufacturing, mining and business development, sketches of eminent and interesting characters, etc., with notes of a tour over it in 1886". state of Ohio, Laning printing Company. p. 631.

Paul Williams founder akron ohio.

- ^ a b c "Akron's Black History Timeline: 1920–1929: The Third Decade". City of Akron. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "Akron Ohio Historical Timeline 1950–1999". City of Akron. Archived from the original on June 22, 2018.

- ^ Smith, Oscar (October 23, 1952). "He Digs Up History Of City's Street Names". The Akron Beacon Journal. p. 33. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ A Portrait and Biographical Record of Portage and Summit Counties, Ohio. A. W. Bowen & Company. 1898. p. 307.

- ^ ἄκρον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "Akron's Historic Timeline: 1800–1849". City of Akron. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ "Akron School Law". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ a b Robert T. Englert (February 2004). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: First Presbyterian Church". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2009.

- ^ Kilde, Jeanne Halgren (2005). When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-19-517972-9.

- ^ Jenks, Christopher Stephen (December 1995). "American Religious Buildings: The Akron Plan Sunday School". Partners for Sacred Places. New York Landmarks Conservancy. Archived from the original on March 18, 2003. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

Thousands of Akron Plan Sunday Schools were built throughout New York State and the country between 1870 and the First World War.

- ^ Newton, Ken (May 5, 2013). "A victim of its own success". St. Joseph News-Press. p. A7.

- ^ Barry Popik, Smoky City Archived May 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, barrypopik.com website, March 27, 2005

- ^ a b "Police Technology". Inventors.about.com. April 3, 2008. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ "Akron Ohio History: 1900 Riot". Ci.akron.oh.us. Archived from the original on February 15, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Goodyear Corporate || Historic Overview". Goodyear.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "General Tire * Our Company". Generaltire.com. March 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "CONTENTdm Collection". Summitmemory.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Exhibit reveals history from deaf perspective". Deaftoday.com. March 24, 2003. Archived from the original on January 8, 2009.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Giffin, William (2005). African Americans and the Color Line in Ohio, 1915–1930. Thompson Shore, Inc. p. 210. ISBN 9780814210031 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Firestone Park" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 20, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Clark Gable – Ohio History Central – A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on October 3, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Goodyear Blimps". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on October 3, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Cragg, Dan (2001). Guide to military installations (6th ed.). Stackpole Books. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-8117-2781-5. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2009.

- ^ Akron-Summit County Public Library. "Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation, Facts About the World's Largest Airship Factory & Dock". Summit Memory. Archived from the original on April 18, 2009. Retrieved November 15, 2008.

- ^ "Charles Arthur 'Pretty Boy' Floyd". Ngeorgia.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Claims to Fame – Products". Epodunk. Archived from the original on April 8, 2007. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ "Akron Rubber Strike of 1936 – Ohio History Central – A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Akron, Ohio" (PDF). www.brookings.edu. Retrieved April 3, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ a b "A New Brand Of Tech Cities – Newsweek and The Daily Beast". Newsweek.com. April 29, 2001. Archived from the original on November 26, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "City of Akron Named 2025 All-America City". City of Akron. June 30, 2025. Retrieved July 16, 2025.

- ^ Mackinnon, Jim (May 8, 2013). "Goodyear's new headquarters reflects a new company". Akron Beacon Journal Ohio.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Mackinnon, Jim (November 25, 2009). "Tech center plans progressing". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Bridgestone Americas, Inc". Bridgestone-firestone.com. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ Downing, Bob (December 10, 2012). "EPA begins new review of Superfund cleanup at Akron's Summit Equipment". Ohio.com. Beacon Journal. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016.

- ^ Harper, John (December 28, 2015). "When PCBs, heavy metal spewed from smokestacks in southwest Akron: Toxic Remains". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "SUMMIT EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES INCORPORATION". epa.gov. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016.

- ^ "ASCPL Digital Exhibit". Akronlibrary.org. July 4, 1905. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ "Ku Klux Klan – Ohio History Central – A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Ohio History Central. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ Grevatt, Martha (October 9, 2008). "Ohio foreclosure prompts suicide attempt". Workers.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ^ "Hungry Bacteria Begins Saving Akron Money" (Press release). City of Akron, Ohio. December 12, 2007. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "Akron leads the way". Builders Exchange. 2007. Archived from the original on April 3, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files for Places – Ohio". United States Census. Archived from the original on May 4, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture. "USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map". United States National Arboretum. Archived from the original on March 3, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Weather Service. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Akron Canton RGNL AP, OH". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Akron Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Akron: News Releases 2005: Mayor Brings $2 Million to Weekly News Conference". Ci.akron.oh.us. March 25, 2005. Archived from the original on September 4, 2005. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ "Population estimates, July 1, 2015, (V2015)". Archived from the original on April 11, 2016.

- ^ Shuy, Roger (September 17, 2006). "Language Log: Wut? Wen? Wich?". Itre.cis.upenn.edu. Archived from the original on December 16, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Hall, Joan Houston (2003). Dictionary of American Regional English. p. 38. ISBN 978-0674008847.

It may be called the devil's strip in Akron...

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Akron city, Ohio". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Akron city, Ohio". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Akron city, Ohio". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b c d "Akron city, Ohio - Census Bureau Profile". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Akron (city), Ohio". State & County QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 12, 2013.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Morgan Quitno's 7th Annual Safest City Award in Dangerous Rank Order". Morganquitno.com. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Preliminary Ohio Crime Statistics for 2007". Funkhouserlaw.com. June 2, 2008. Archived from the original on November 19, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ King, Jeffery S (August 1, 1999). The Life and Death of Pretty Boy Floyd. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-650-0.

- ^ "Ohio's Meth Problem Centered in Akron Area". thecrimereport.org. The Crime Report. August 10, 2005. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ^ Armon, Rick (September 5, 2008). "Summit County has third most methamphetamine sites in U.S". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Methamphetamine – Ohio Drug Threat Assessment". Justice.gov. June 15, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "National Clandestine Laboratory Register – Ohio" (PDF). Justice.Gov. United States Department of Justice. August 19, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2010.Note- The list uses the mailing address for each site, so not all sites listed as being in Akron are actually within the Akron city limits but instead have an Akron ZIP code

- ^ Armon, Rick (February 15, 2009). "Meth lab raids jump 42% in Summit". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "City of Akron: News Releases 2008: State of the City Presentation". Ci.akron.oh.us. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "Greater Akron's Competitive Advantages". Greater Akron Chamber. Archived from the original on August 4, 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2010.

- ^ Byard, Katie (December 5, 2007). "Goodyear has tentative deal to stay in Akron". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Goodyear Holds Grand Opening of New Global Headquarters" (Press release). Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company. May 9, 2013. Retrieved August 12, 2025 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Lin, Betty (May 26, 2009). "KeyBank breaks ground on Akron, Ohio office building |". Securityinfowatch.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Polymer Valley – Ohio History Central – A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Ohio History Central. July 1, 2005. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "A New Brand Of Tech Cities". Newsweek. April 30, 2001. Archived from the original on January 29, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Bowles, Mark (2008). Chains of Opportunity: The University of Akron and the Emergence of the Polymer Age 1909-2007. University of Akron Press; Illustrated edition. ISBN 978-1931968539.

- ^ "Akron's biomedical corridor taking shape". Archived from the original on June 15, 2011.

- ^ "Akron Ohio: Akron Ohio: Mayor's Office of Economic Development". Ci.akron.oh.us. Archived from the original on September 19, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

- ^ "Summa Health System – Summa Celebrates 11th Consecutive Year on U.S. New". Ssl.summahealth.org. July 11, 2008. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ^ "Summa Health System – Locations". Summahealth.org. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Summa Health System – Hospital Rankings". Summahealth.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2006. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ^ "Akron General Medical Center". Akron General. September 22, 2008. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Powell, Cheryl. "Akron General earns honors". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ "Akron Children's Hospital : Why Akron Children's?". Akronchildrens.org. June 19, 2007. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Microsoft Word - BIA History of Innovation Timeline Web Version 10.13.08.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report : City of Akron". www.akronohio.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ Price, Mark (October 12, 2009). "Local history: Akron's lost landmark retains a grand facade".

- ^ a b "Lock 3 Akron, Ohio Concerts". City of Akron. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ "Museum Collection: On View Now". Akron Art Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on January 9, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

...dedicated to the display of its collection, which focuses on art produced since 1850.

- ^ "Akron Art Museum". 2005 American Architecture Awards. The Chicago Athenaeum. 2005. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Architecture". Akron Art Museum. Archived from the original on March 9, 2010. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Museum History". Akron Art Museum. 2007. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ "Akron Zoo History | Akron Zoo". www.akronzoo.org. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "The American Toy Marble Museum Akron, Ohio". Americantoymarbles.com. Archived from the original on March 26, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Hamburger festivals, special events have participants flipping". Post-gazette.com. July 15, 2007. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ "First Night Akron". Downtown Akron Partnership. 2009. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ Carney, Jim (June 11, 2009). "This Founders' Day marks A.A. milestones". Ohio.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ "Akron, Ohio – Birthplace of Alcoholics Anonymous". Akron Area Intergroup Council of Alcoholics Anonymous. Archived from the original on June 16, 2009. Retrieved January 20, 2010.

- ^ "Akron Named Tree City USA by the Arbor Day Foundation" (Press release). City of Akron. April 17, 2009. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- ^ When Church Became Theatre: The Transformation of Evangelical Architecture and Worship in Nineteenth-Century America Archived January 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Jeanne Halgren Kilde. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-19-517972-2. p.185

- ^ a b FirstMerit Restoration, "FirstMerit Tower". Archived from the original on March 11, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ^ "Scraping the Sky". Beacon Journal. Knight-Ridder. March 14, 1999. p. Beacon Magazine 13.

- ^ "Akron Art Museum – Building the Akron Art Museum". Akronartmuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Akron Art Museum – Building the Akron Art Museum". Akronartmuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ "Akron Art Museum – Building the Akron Art Museum". Akronartmuseum.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2012.

- ^ A&E, with Richard Guy Wilson, Ph.D., (2000). America's Castles: The Auto Baron Estates, A&E Television Network

- ^ "NHL nomination for Stan Hywet Hall and Gardens". National Park Service. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ^ Annasue McCleave Wilson (September 20, 1998). "English Manor In the Heartland". The New York Times.

- ^ "F. Schumacher Milling Company". Brandnamecooking.com. April 16, 1908. Archived from the original on January 3, 2010. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "The Ohio Academy of Science". Heartland Science. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2010.