Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Education in the United States

View on Wikipedia

| National education budget (2023-24) | |

|---|---|

| Budget | $222.1 billion (0.8% of GDP)[2] |

| Per student | More than $11,000 (2005)[1] |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | English |

| System type | Federal, state, local, private |

| Literacy (2017 est.) | |

| Total | 99%[3] |

| Male | 99%[3] |

| Female | 99%[3] |

| Enrollment (2020[4]) | |

| Total | 49.4 million |

| Primary | 34.1 million1 |

| Secondary | 15.3 million2 |

| Post secondary | 19 million3 |

| Attainment | |

| Secondary diploma | 91% (among 25–68 year-olds, 2018)[6][7][8] |

| Post-secondary diploma | 46.4% (among 25–64 year-olds, 2017)[5] |

| 1Includes kindergarten and middle school 2Includes high school 3Includes graduate school | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Education in the United States |

|---|

| Summary |

| History |

| Curriculum topics |

| Education policy issues |

| Levels of education |

|

|

The United States does not have a national or federal educational system. Although there are more than fifty independent systems of education (one run by each state and territory, the Bureau of Indian Education, and the Department of Defense Dependents Schools), there are a number of similarities between them. Education is provided in public and private schools and by individuals through homeschooling. Educational standards are set at the state or territory level by the supervising organization, usually a board of regents, state department of education, state colleges, or a combination of systems. The bulk of the $1.3 trillion in funding comes from state and local governments, with federal funding accounting for about $260 billion in 2021[9] compared to around $200 billion in past years.[2]

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, most schools in the United States did not mandate regular attendance. In many areas, students attended school for no more than three to four months out of the year.[10] By state law, education is compulsory over an age range starting between five and eight and ending somewhere between ages sixteen and nineteen, depending on the state.[11] This requirement can be satisfied in public or state-certified private schools, or an approved home school program. Compulsory education is divided into three levels: elementary school, middle or junior high school, and high school. As of 2013, about 87% of school-age children attended state-funded public schools, about 10% attended tuition and foundation-funded private schools,[12] and roughly 3% were home-schooled.[13] Enrollment in public kindergartens, primary schools, and secondary schools declined by 4% from 2012 to 2022 and enrollment in private schools or charter schools for the same age levels increased by 2% each.[14]

Numerous publicly and privately administered colleges and universities offer a wide variety of post-secondary education. Post-secondary education is divided into college, as the first tertiary degree, and graduate school. Higher education includes public and private research universities, usually private liberal arts colleges, community colleges, for-profit colleges, and many other kinds and combinations of institutions. College enrollment rates in the United States have increased over the long term.[15] At the same time, student loan debt has also risen to $1.5 trillion. The large majority of the world's top universities, as listed by various ranking organizations, are in the United States, including 19 of the top 25, and the most prestigious – Harvard University.[16][17][18][19] Enrollment in post-secondary institutions in the United States declined from 18.1 million in 2010 to 15.4 million in 2021.[20]

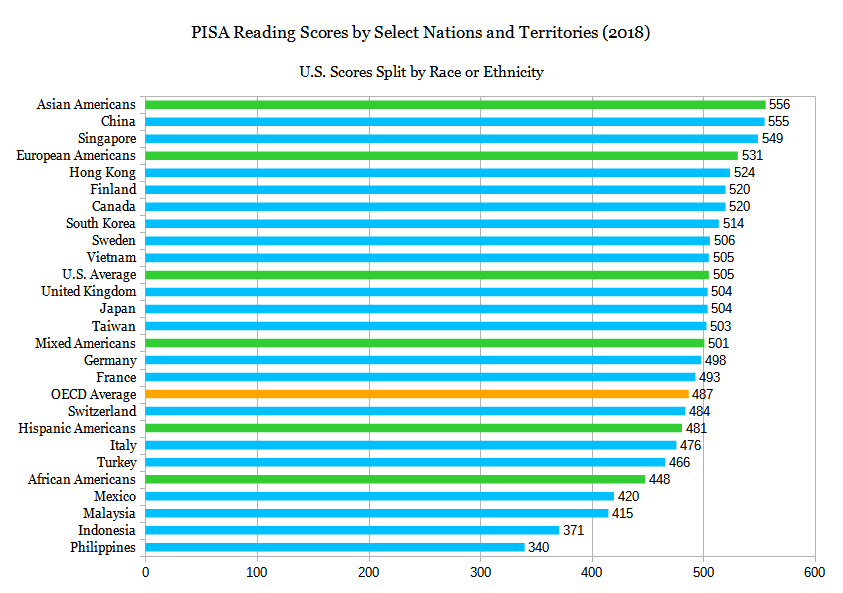

Total expenditures for American public elementary and secondary schools amounted to $927 billion in 2020–21 (in constant 2021–22 dollars).[21] In 2010, the United States had a higher combined per-pupil spending for primary, secondary, and post-secondary education than any other OECD country (which overlaps with almost all of the countries designated as being developed by the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations) and the U.S. education sector consumed a greater percentage of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) than the average OECD country.[22] In 2014, the country spent 6.2% of its GDP on all levels of education—1.0 percentage points above the OECD average of 5.2%.[23] In 2014, the Economist Intelligence Unit rated U.S. education as 14th best in the world. The Programme for International Student Assessment coordinated by the OECD currently ranks the overall knowledge and skills of American 15-year-olds as 19th in the world in reading literacy, mathematics, and science with the average American student scoring 495, compared with the OECD Average of 488.[24][25] In 2017, 46.4% of Americans aged 25 to 64 attained some form of post-secondary education.[5] 48% of Americans aged 25 to 34 attained some form of tertiary education, about 4% above the OECD average of 44%.[26][27][28] 35% of Americans aged 25 and over have achieved a bachelor's degree or higher.[29]

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]New England encouraged its towns to support free public schools funded by taxation. In the early 19th century, Massachusetts took the lead in education reform and public education with programs designed by Horace Mann that were widely emulated across the North. Teachers were specially trained in normal schools and taught the three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic) and also history and geography. Public education was at the elementary level in most places.

After the Civil War end in 1865, cities began building high schools. The South was far behind northern standards on every educational measure and gave weak support to its segregated all-black schools. However, northern philanthropy and northern churches provided assistance to private black colleges across the South. Religious denominations across the country set up their private colleges. States also opened state universities, but they were quite small until well into the 20th century.

In 1823, Samuel Read Hall founded the first normal school, the Columbian School in Concord, Vermont,[30][31] aimed at improving the quality of the burgeoning common school system by producing more qualified teachers.

During Reconstruction, the United States Office of Education was created in an attempt to standardize educational reform across the country. At the outset, the goals of the Office were to track statistical data on schools and provide insight into the educational outcomes of schools in each state. While supportive of educational improvement, the office lacked the power to enforce policies in any state. Educational aims across the states in the nineteenth century were broad, making it difficult to create shared goals and priorities. States like Massachusetts, with long-established educational institutions, had well-developed priorities in place by the time the Office of Education was established. In the South and the West, however, newly formed common school systems had different needs and priorities.[32] Competing interests among state legislators limited the ability of the Office of Education to enact change.

In the mid-19th century, the rapidly increasing Catholic population led to the formation of parochial schools in the largest cities. Theologically oriented Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Jewish bodies on a smaller scale set up their own parochial schools. There were debates over whether tax money could be used to support them, with the answer typically being no. From about 1876, thirty-nine states passed a constitutional amendment to their state constitutions, called Blaine Amendment after James G. Blaine, one of their chief promoters, forbidding the use of public tax money to fund local parochial schools.

States passed laws to make schooling compulsory between 1852 (Massachusetts) and 1917 (Mississippi). They also used federal funding designated by the Morrill Land-Grant Acts of 1862 and 1890 to set up land grant colleges specializing in agriculture and engineering. By 1870, every state had free elementary schools,[33] albeit only in urban centers. According to a 2018 study in the Economic Journal, states were more likely to adopt compulsory education laws during the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1914) if they hosted more European immigrants with lower exposure to civic values.[34]

Following Reconstruction the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute was founded in 1881 as a state college, in Tuskegee, Alabama, to train "Colored Teachers," led by Booker T. Washington, (1856–1915), who was himself a freed slave. His movement spread, leading many other Southern states to establish small colleges for "Colored or Negro" students entitled "A. & M." ("Agricultural and Mechanical") or "A. & T." ("Agricultural and Technical"), some of which later developed into state universities. Before the 1940s, there were very few black students at private or state colleges in the North and almost none in the South.[35]

Responding to the many competing academic philosophies being promoted at the time, an influential working group of educators, known as the Committee of Ten and established in 1892 by the National Education Association, recommended that children should receive twelve years of instruction, consisting of eight years of elementary education (in what were also known as "grammar schools") followed by four years in high school ("freshmen", "sophomores", "juniors" and "seniors").

Gradually by the late 1890s, regional associations of high schools, colleges and universities were being organized to coordinate proper accrediting standards, examinations, and regular surveys of various institutions in order to assure equal treatment in graduation and admissions requirements, as well as course completion and transfer procedures.

Timeline of introduction of compulsory education

[edit]- 1642:

Thirteen Colonies[36] (The Massachusetts Bay Colony introduced compulsory education before the formation of the United States)

Thirteen Colonies[36] (The Massachusetts Bay Colony introduced compulsory education before the formation of the United States) - 1814:

U.S. Virgin Islands[37] (As part of the Danish West Indies; education was additionally made compulsory for slaves in 1839. Territories sold to the

U.S. Virgin Islands[37] (As part of the Danish West Indies; education was additionally made compulsory for slaves in 1839. Territories sold to the  United States in 1916)

United States in 1916) - 1841:

Hawaii[38] (Kingdom of Hawaii)

Hawaii[38] (Kingdom of Hawaii) - 1852:

Massachusetts[39] (First state law enacted by a current State or Territory of the

Massachusetts[39] (First state law enacted by a current State or Territory of the  United States)

United States) - 1864:

Washington, D.C.[39]

Washington, D.C.[39] - 1867:

Vermont[39]

Vermont[39] - 1871:

Michigan,

Michigan,  New Hampshire,

New Hampshire,  Washington,

Washington,  Connecticut[39]

Connecticut[39] - 1873:

Nevada,

Nevada,  Kansas,

Kansas,  New York,

New York,  California[39]

California[39] - 1875:

New Jersey,

New Jersey,  Maine[39]

Maine[39] - 1876:

Wyoming[39]

Wyoming[39] - 1877:

Ohio[39]

Ohio[39] - 1879:

Wisconsin[40]

Wisconsin[40] - 1883:

Montana,

Montana,  Illinois,

Illinois,  North Dakota,

North Dakota,  South Dakota,

South Dakota,  Rhode Island[39]

Rhode Island[39] - 1885:

Minnesota[39]

Minnesota[39] - 1887:

Idaho,

Idaho,  Nebraska[39]

Nebraska[39] - 1889:

Oregon,

Oregon,  Colorado[39]

Colorado[39] - 1890:

Utah[39]

Utah[39] - 1891:

New Mexico[39]

New Mexico[39] - 1895:

Pennsylvania[39]

Pennsylvania[39] - 1896:

Kentucky,

Kentucky,  Hawaii[39] (Hawaii Territory)

Hawaii[39] (Hawaii Territory) - 1897:

Indiana,

Indiana,  West Virginia[39]

West Virginia[39] - 1899:

Arizona[39]

Arizona[39] - 1901:

Philippines[41] (De Facto compulsory under U.S. Military Administration, Philippines later granted independence)

Philippines[41] (De Facto compulsory under U.S. Military Administration, Philippines later granted independence) - 1902:

Iowa,

Iowa,  Maryland,[39]

Maryland,[39]  Puerto Rico[42] (English instruction made mandatory following the Annexation of Puerto Rico)

Puerto Rico[42] (English instruction made mandatory following the Annexation of Puerto Rico) - 1904:

Guam[43]

Guam[43] - 1905:

Tennessee,

Tennessee,  Missouri[39]

Missouri[39] - 1907:

Delaware,

Delaware,  North Carolina,

North Carolina,  Oklahoma[39]

Oklahoma[39] - 1908:

Virginia[39]

Virginia[39] - 1909:

Arkansas[39]

Arkansas[39] - 1910:

Louisiana[39]

Louisiana[39] - 1915:

Alabama,

Alabama,  South Carolina,

South Carolina,  Florida,

Florida,  Texas[39]

Texas[39] - 1916:

Georgia (U.S. state)[39]

Georgia (U.S. state)[39] - 1918:

Mississippi[39]

Mississippi[39] - 1929:

Alaska[39]

Alaska[39] - 1978:

Northern Mariana Islands[44]

Northern Mariana Islands[44] - 1994:

American Samoa[45]

American Samoa[45] - 2019:

U.S. Virgin Islands[46] (De Jure)

U.S. Virgin Islands[46] (De Jure)

20th century

[edit]By 1910, 72% of children were attending school. Between 1910 and 1940 the high school movement resulted in a rapid increase in public high school enrollment and graduations.[47] By 1930, 100% of children were attending school, excluding children with significant disabilities or medical concerns.[47] From 1940 to 1966, the percentage of U.S. adults over the age of 25 that had completed 4 years of high school doubled from 25 percent to 50 percent, while the ratio grew to 75 percent by 1987 and to 85 percent by 2005.[48][49][50] For 4 years of college, the percentage grew from 5 percent in 1940 to 10 percent in 1966, and further to 20 percent by 1987 and 30 percent by 2009.[48][49][50]

Private schools spread during this time, as well as colleges and, in the rural centers, land grant colleges.[47] In 1922, an attempt was made by the voters of Oregon to enact the Oregon Compulsory Education Act, which would require all children between the ages of 8 and 16 to attend public schools, only leaving exceptions for mentally or physically unfit children, exceeding a certain living distance from a public school, or having written consent from a county superintendent to receive private instruction. The law was passed by popular vote but was later ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, determining that "a child is not a mere creature of the state". This case settled the dispute about whether or not private schools had the right to do business and educate within the United States.[51]

By 1938, there was a movement to bring education to six years of elementary school, four years of junior high school, and four years of high school.[52]

During World War II, enrollment in high schools and colleges plummeted as many high school and college students and teachers dropped out to enlist or take war-related jobs.[53][54][55]

The 1946 National School Lunch Act provided low-cost or free school lunch meals to qualified low-income students through subsidies to schools based on the idea that a "full stomach" during the day supports class attention and studying.

The 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas made racial desegregation of public elementary and high schools mandatory, although white families often attempted to avoid desegregation by sending their children to private secular or religious schools.[56][57][58] In the years following this decision, the number of Black teachers rose in the North but dropped in the South.[59]

In 1965, the far-reaching Elementary and Secondary Education Act ('ESEA'), passed as a part of President Lyndon B. Johnson's War on poverty, provided funds for primary and secondary education ('Title I funding'). Title VI explicitly forbade the establishment of a national curriculum.[60] Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965 created the Pell Grant program which provides financial support to students from low-income families to access higher education.

In 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act established funding for special education in schools.

The Higher Education Amendments of 1972 made changes to the Pell Grant. The 1975 Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) required all public schools accepting federal funds to provide equal access to education and one free meal a day for children with physical and mental disabilities. The 1983 National Commission on Excellence in Education report, famously titled A Nation at Risk, touched off a wave of federal, state, and local reform efforts, but by 1990 the country still spent only 2% of its budget on education, compared with 30% on support for the elderly.[61] In 1990, the EHA was replaced with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which placed more focus on students as individuals, and also provided for more post-high school transition services.

21st century

[edit]The No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, passed by a bipartisan coalition in Congress, provided federal aid to the states in exchange for measures to penalize schools that were not meeting the goals as measured by standardized state exams in mathematics and language skills. This made standardized testing a requirement.[62][63][64] In the same year, the U.S. Supreme Court diluted some of the century-old "Blaine" laws upheld an Ohio law allowing aid to parochial schools under specific circumstances.[65] The 2006 Commission on the Future of Higher Education evaluated higher education. In December 2015, then-American President Barack Obama signed legislation replacing No Child Left Behind with the Every Student Succeeds Act.[66]

The Great Recession of 2007–2009 caused a sharp decline in tax revenues in all American states and cities. The response included cuts to education budgets. Obama's $800 billion stimulus package of 2009 included $100 billion for public schools, which every state used to protect its education budget. In terms of sponsoring innovation; however, then-President Obama and then-Education Secretary Arne Duncan pursued K-12 education reform through the Race to the Top grant program. With over $15 billion of grants at stake, 34 states quickly revised their education laws according to the proposals of advanced educational reformers. In the competition, points were awarded for allowing charter schools to multiply, for compensating teachers on a merit basis including student test scores, and for adopting higher educational standards.

There were incentives for states to establish college and career-ready standards, which in practice meant adopting the Common Core State Standards Initiative that had been developed on a bipartisan basis by the National Governors Association, and the Council of Chief State School Officers. The criteria were not mandatory, they were incentives to improve opportunities to get a grant. Most states revised their laws accordingly, even though they realized it was unlikely they would win a highly competitive new grant. Race to the Top had strong bipartisan support, with centrist elements from both parties. It was opposed by the left wing of the Democratic Party, and by the right wing of the Republican Party, and criticized for centralizing too much power in Washington. Complaints also came from middle-class families, who were annoyed at the increasing emphasis on teaching to the test, rather than encouraging teachers to show creativity and stimulating students' imagination.[67][68] Voters in both major parties have been critical of the Common Core initiative.[69]

During the 2010s, American student loan debt became recognized as a social problem.[70][71][72][73][74]

Like every wealthy country, the COVID-19 pandemic and Deltacron hybrid variant had a great impact on education in the United States, requiring schools to implement technology and transition to virtual meetings.[75][76] Although the use of technology improves the grading process and the quality of information received,[77] critics assess it a poor substitute for in-person learning, and that online-only education disadvantages students without internet access, who disproportionately live in poor households, and that technology may make it harder for students to pay attention.[78][79]

Some colleges and universities became vulnerable to permanent closure during the pandemic. Universities and colleges were refunding tuition monies to students while investing in online technology and tools, making it harder to invest into empty campuses. Schools are defined as being in low financial health if their combined revenue and unrestricted assets will no longer cover operating expenses in six years. Before COVID-19, 13 institutions were in danger of closing within 6 years in New England.[80] With the presence of COVID-19, that number has increased to 25 institutions.[80] In the United States due to the financial impact caused by COVID-19, 110 more colleges and universities are now at risk of closing. This labels the total number of colleges and universities in peril due to pandemic to be 345 institutions.[80] While prestigious colleges and universities have historically had financial cushion due to high levels of enrollment, private colleges at a low risk have dropped from 485 to 385.[80] Federal COVID-19 relief has assisted students and universities. However, it has not been enough to bandage the financial wound created by COVID-19. Colby-Sawyer College located in New Hampshire has received about $780,000 in assistance through the United States Department of Education.[80] About half of this money was dispersed amongst the student body. Colby-Swayer College was also capable of receiving a loan of $2.65 million, to avoid layoffs of their 312 employees.[80]

Yale economist Fabrizio Zilibotti co-authored a January 2022 study with professors from the Columbia University, New York University, University of Pennsylvania, Harvard University, Northwestern University, and the University of Amsterdam, showing that "the pandemic is widening educational inequality and that the learning gaps created by the crisis will persist."[79][81] As of result, COVID-19 educational impact in the United States has ended by March 11, 2022, as Deltacron cases fall and ahead of the living with an endemic phase.[citation needed]

Statistics

[edit]

In 2000, 76.6 million students had enrolled in schools from kindergarten through graduate schools. Of these, 72% aged 12 to 17 were considered academically "on track" for their age, i.e. enrolled in at or above grade level. Of those enrolled in elementary and secondary schools, 5.7 million (10%) were attending private schools.[83]

As of 2022, 89% of the adult population had completed high school and 34% had received a bachelor's degree or higher. The average salary for college or university graduates is greater than $51,000, exceeding the national average of those without a high school diploma by more than $23,000, according to a 2005 study by the U.S. Census Bureau.[84] The 2010 unemployment rate for high school graduates was 10.8%; the rate for college graduates was 4.9%.[85]

The country has a reading literacy rate of 99% of the population over age 15,[86] while ranking below average in science and mathematics understanding compared to other developed countries.[87] In 2014, a record high of 82% of high school seniors graduated, although one of the reasons for that success might be a decline in academic standards.[88]

The poor performance has pushed public and private efforts such as the No Child Left Behind Act. In addition, the ratio of college-educated adults entering the workforce to the general population (33%) is slightly below the mean of other[which?] developed countries (35%)[89] and rate of participation of the labor force in continuing education is high.[90] A 2000s (decade) study by Jon Miller of Michigan State University concluded that "A slightly higher proportion of American adults qualify as scientifically literate than European or Japanese adults".[91]

In 2006, there were roughly 600,000 homeless students in the United States, but after the Great Recession this number more than doubled to approximately 1.36 million.[92] The Institute for Child Poverty and Homelessness keeps track of state by state levels of child homelessness.[93] As of 2017[update], 27% of U.S. students live in a mother-only household, 20% live in poverty, and 9% are non-English speaking.[94]

An additional factor in the United States education system is the socioeconomic background of the students being tested. According to the National Center for Children in Poverty, 41% of U.S. children under the age of 18 come from lower-income families.[95] These students require specialized attention to perform well in school and on the standardized tests.[95]

The Human Rights Measurement Initiative[96] finds that the United States is achieving 77.8% of what should be possible on the right to education at its level of income.[97]

Resulting from school closures necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, over one million eligible children were not enrolled in kindergarten for the 2021–2022 school year.[98] The 2022 annual Report on the Condition of Education[99] conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) for the U.S. Department of Education[100] indicates that prekindergarten to grade 12 enrollment decreased from 50.8 million in fall 2019 to 49.4 million students in fall 2020, a 3% decrease, which matches 2009 enrollment, eradicating the previous decade of growth. During the 2019–2020 school year, enrollment rates decreased by 6% for those aged five, dropping from 91% to 84%, and by 13% for those aged three and four, from 54% to 40%.[4]

Summer 2022 polls and surveys revealed that mental health issues were reported by 60% of college students, with educational institutions being understaffed and unprepared to effectively address the crisis.[101]

A five-year, $14 million study of U.S. adult literacy involving lengthy interviews of U.S. adults, the most comprehensive study of literacy ever commissioned by the U.S. government,[102] was released in September 1993. It involved lengthy interviews of over 26,700 adults statistically balanced for age, gender, ethnicity, education level, and location (urban, suburban, or rural) in 12 states across the U.S. and was designed to represent the U.S. population as a whole. This government study showed that 21% to 23% of adult Americans were not "able to locate information in text", could not "make low-level inferences using printed materials", and were unable to "integrate easily identifiable pieces of information".[102]

The U.S. Department of Education's 2003 statistics indicated that 14% of the population—or 32 million adults—had very low literacy skills.[103] Statistics were similar in 2013.[104] In 2015, only 37% of students were able to read at a proficient level, a level which has barely changed since the 1990s.[105]

Attainment

[edit]In the 21st century, the educational attainment of the U.S. population is similar to that of many other industrialized countries with the vast majority of the population having completed secondary education and a rising number of college graduates that outnumber high school dropouts. As a whole, the population of the United States is becoming increasingly more educated.[82]

Post-secondary education is valued very highly by American society and is one of the main determinants of class and status.[citation needed] As with income, however, there are significant discrepancies in terms of race, age, household configuration and geography.[106]

Since the 1980s, the number of educated Americans has continued to grow, but at a slower rate. Some have attributed this to an increase in the foreign-born portion of the workforce. However, the decreasing growth of the educational workforce has instead been primarily due to the slowing down in educational attainment of people schooled in the United States.[107]

Remedial education in college

[edit]Despite high school graduates formally qualifying for college, only 4% of two-year and four-year colleges do not have any students in noncredit remedial courses. Over 200 colleges place most of their first-year students in one or more remedial courses. Almost 40% of students in remedial courses fail to complete them. The cause cannot be excessively demanding college courses, since grade inflation has made those courses increasingly easy in recent decades.[108][109]

Sex differences

[edit]

According to research over the past 20 years, girls generally outperform boys in the classroom on measures of grades across all subjects and graduation rates. This is a turnaround from the early 20th century when boys usually outperformed girls. Boys have still been found to score higher on standardized tests than girls and go on to be better represented in the more prestigious, high-paying STEM fields.

Religious achievement differences

[edit]According to a Pew Research Center study in 2016, there is an association between education and religious affiliation. About 77% of American Hindus have a graduate and post-graduate degree followed by Unitarian Universalists (67%), Jews (59%), Anglicans (59%), Episcopalians (56%), Presbyterians (47%), and United Church of Christ (46%).[111] According to the same study, about 43% of American atheists, 42% of agnostics, and 24% of those who say their religion is "nothing in particular" have a graduate or post-graduate degree.[111] Largely owing to the size of their constituency, more Catholics hold college degrees (over 19 million) than do members of any other faith community in the United States.[111]

International comparison

[edit]In the OECD's Programme for International Student Assessment 2003, which emphasizes problem-solving, American 15-year-olds ranked 24th of 38 in mathematics, 19th of 38 in science, 12th of 38 in reading, and 26th of 38 in problem-solving.[112] In the 2006 assessment, the U.S. ranked 35th out of 57 in mathematics and 29th out of 57 in science. Reading scores could not be reported due to printing errors in the instructions of the U.S. test booklets. U.S. scores were behind those of most other developed nations.[113]

In 2007, Americans stood second only to Canadians in the percentage of 35 to 64-year-olds holding at least two-year degrees. Among 25 to 34-year-olds, the country stands tenth. The nation stands 15 out of 29 rated nations for college completion rates, slightly above Mexico and Turkey.[114]

In 2009, US fourth and eighth graders tested above average on the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study tests, which emphasizes traditional learning.[115]

In 2012, the OECD ranked American students 25th in math, 17th in science, and 14th in reading compared with students in 27 other countries.[116]

In the 2013 OECD Survey of Adult Skills, 33 nations took part with adults ages 16 to 65, surveying skills such as: numeracy, literacy, and problem-solving. The Educational Testing Service (ETS) found that millennials—aged from teens to early 30s—scored low. Millennials in Spain and Italy scored lower than those in the U.S., while in numeracy, the three countries tied for last. U.S. millennials came in last among all 33 nations for problem-solving skills.[117]

In 2014, the United States was one of three OECD countries where the government spent more on schools in rich neighborhoods than in poor neighborhoods, the others being Turkey and Israel.[118]

According to a 2016 report published by the U.S. News & World Report, of the top ten colleges and universities in the world, eight are American.[119]

Educational stages

[edit]

Formal education in the U.S. is divided into a number of distinct educational stages. Most children enter the public education system around the age of five or six. Children are assigned to year groups known as grades.

The American school year traditionally begins at the end of August or early in September, after a traditional summer vacation or break. Children customarily advance together from one grade to the next as a single cohort or "class" upon reaching the end of each school year in late May or early June.

Depending upon their circumstances, children may begin school in pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, or first grade. Students normally attend 12 grades of study over 12 calendar years of primary/elementary and secondary education before graduating and earning a diploma that makes them eligible for admission to higher education. Education is mandatory until age 16 (18 in some states).

In the U.S., ordinal numbers (e.g., first grade) are used for identifying grades. Typical ages and grade groupings in contemporary, public, and private schools may be found through the U.S. Department of Education. Generally, there are three stages: elementary school (grades K/1–2/3/4/5/6), intermediate school (3/4–5/6), middle school / junior high school (grades 5/6/7–8/9), and high school / senior high school (grades 9/10–12).[121] There is variability in the exact arrangement of grades by state, as the following table indicates. Note that many people may not choose to attain higher education immediately after high school graduation, so the age of completing each level of education may vary. The table below shows the traditional education path of a student through preschool to high school.

| Category | School Grade Level | Ages |

|---|---|---|

| Preschool | Pre-kindergarten | 3–5 |

| Compulsory education | ||

| Elementary school | Kindergarten | 5–6 |

| 1st grade | 6–7 | |

| 2nd grade | 7–8 | |

| 3rd grade | 8–9 | |

| 4th grade | 9–10 | |

| 5th grade | 10–11 | |

| Middle school | 6th grade | 11–12 |

| 7th grade | 12–13 | |

| 8th grade | 13–14 | |

| High school | 9th grade / Freshman | 14–15 |

| 10th grade / Sophomore | 15–16 | |

| 11th grade / Junior | 16–17 | |

| 12th grade / Senior | 17–18 | |

| Continuing education | ||

| Vocational education | 16 and up[citation needed] | |

| Adult education | 18 and up | |

| Higher education | Grade level |

|---|---|

| College, University | Freshman |

| Sophomore | |

| Junior | |

| Senior | |

| Graduate school (with various degrees and curricular partitions thereof) | |

In K–12 education, sometimes students who receive failing grades are held back a year and repeat coursework in the hope of earning satisfactory scores on the second try. In 2016, 1.9% of students were held back a year.(compared to the 3.1% in 2000)[122]

High school graduates sometimes take one or more gap years before the first year of college, for travel, work, public service, or independent learning. Some might opt for a postgraduate year before college.[123] Many high schoolers also earn an associate degree when they graduate high school.[124]

Many undergraduate college programs now commonly are five-year programs. This is especially common in technical fields, such as engineering. The five-year period often includes one or more periods of internship with an employer in the chosen field.

Of students who were freshmen in 2005 seeking bachelor's degrees at public institutions, 32% took four years, 12% took five years, 6% took six years, and 43% did not graduate within six years. The numbers for private non-profit institutions were 52% in four, 10% in five, 4% in six, and 35% failing to graduate.[125][needs update]

Some undergraduate institutions offer an accelerated three-year bachelor's degree, or a combined five-year bachelor's and master's degrees. Many times, these accelerated degrees are offered online or as evening courses and are targeted mainly but not always for adult learners/nontraditional students.[citation needed]

Many graduate students do not start professional schools immediately after finishing undergraduate studies but work for a time while saving up money or deciding on a career direction.

The National Center for Education Statistics found that in 1999–2000, 73% of undergraduates had characteristics of nontraditional students.[126]

Early childhood education

[edit]Early childhood teaching in the U.S. relates to the teaching of children (formally and informally) from birth up to the age of eight.[127] The education services are delivered via preschools and kindergartens.

Preschool

[edit]Preschool (sometimes called pre-kindergarten or jr. kindergarten) refers to non-compulsory classroom-based early-childhood education. The Head Start program is a federally funded early childhood education program for low-income children and their families founded in 1965 that prepares children, especially those of a disadvantaged population, to better succeed in school. However, limited seats are available to students aspiring to take part in the Head Start program. Many community-based programs, commercial enterprises, non-profit organizations, faith communities, and independent childcare providers offer preschool education.

Preschool may be general or may have a particular focus, such as arts education, religious education, sports training, or foreign language learning, along with providing general education.[citation needed] In the United States, Preschool programs are not required, but they are encouraged by educators. Only 69% of 4-year-old American children are enrolled in preschool. Preschool age ranges anywhere from 3 to 5 years old. The curriculum for the day will consist of music, art, pretend play, science, reading, math, and other social activities.

K–12 education

[edit]The U.S. is governed by federal, state, and local education policy. Education is compulsory for all children, but the age at which one can discontinue schooling varies by state and is from 14 to 18 years old.[128]

Free public education is typically provided from Kindergarten (ages 5 and 6) to 12th Grade (ages 17 and 18). Around 85% of students enter public schooling while the remainder are educated through homeschooling or privately funded schools.[129]

Schooling is divided into primary education, called elementary school, and secondary education. Secondary education consists of two "phases" in most areas, which includes a middle/junior high school and high school.

Higher education

[edit]

| Education | Percentage |

|---|---|

| High school graduate | 89.8% |

| Some college | 61.20% |

| Associate degree | 45.16% |

| Bachelor's degree | 34.9% |

| Master's degree | 13.05% |

| Doctorate or professional degree | 3.5% |

Higher education in the United States is an optional final stage of formal learning following secondary education, often at one of the 4,495 colleges or universities and junior colleges in the country.[130] In 2008, 36% of enrolled students graduated from college in four years. 57% completed their undergraduate requirements in six years, at the same college they first enrolled in.[131] The U.S. ranks 10th among industrial countries for percentage of adults with college degrees.[85] Over the past 40 years the gap in graduation rates for wealthy students and low-income students has widened significantly. 77% of the wealthiest quartile of students obtained undergraduate degrees by age 24 in 2013, up from 40% in 1970. 9% of the least affluent quartile obtained degrees by the same age in 2013, up from 6% in 1970.[132]

There are over 7,000 post-secondary institutions in the United States offering a diverse number of programs catered to students with different aptitudes, skills, and educational needs.[133] Compared with the higher education systems of other countries, post-secondary education in the United States is largely deregulated, giving students a variety of choices. Common admission requirements to gain entry to any American university requires a meeting a certain age threshold, high school transcript documenting grades, coursework, and rigor of core high school subject areas as well as performance in AP and IB courses, class ranking, ACT or SAT scores, extracurricular activities, an admissions essay, and letters of recommendation from teachers and guidance counselors. Other admissions criteria may include an interview, personal background, legacy preferences (family members having attended the school), ability to pay tuition, potential to donate money to the school development case, evaluation of student character (based on essays or interviews), and general discretion by the admissions office. While universities will rarely list that they require a certain standardized test score, class ranking, or GPA for admission, each university usually has a rough threshold below which admission is unlikely.

Universities and colleges

[edit]

The traditional path to American higher education is typically through a college or university, the most prestigious forms of higher education in the United States. Universities in the United States are institutions that issue bachelor's, master's, professional, or doctorate degrees; colleges often award solely bachelor's degrees. Some universities offer programs at all degree levels from the associate to the doctorate and are distinguished from community and junior colleges where the highest degree offered is the associate degree or a diploma. Though there is no prescribed definition of a university or college in the United States, universities are generally research-oriented institutions offering undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs.

American universities come in a variety of forms that serve different educational needs. Some counties and cities have established and funded four-year institutions. Some of these institutions, such as the City University of New York, are still operated by local governments. Others such as the University of Louisville and Wichita State University are now operated as state universities. Four-year institutions may be public or private colleges or universities. Private institutions are privately funded and there is a wide variety in size, focus, and operation. Some private institutions are large research universities, while others are small liberal arts colleges that concentrate on undergraduate education. Some private universities are nonsectarian and secular, while others are religiously affiliated.

Rankings

[edit]

Among the United States' most prominent and world-renowned institutions are large research universities that are ranked in such annual publications, including the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, QS World University Rankings, U.S. News & World Report, Washington Monthly, ARWU, by test preparation services such as The Princeton Review or by another university such as the Top American Research Universities ranked by The Center at the University of Florida.[134] These rankings are based on factors such as brand recognition, number of Nobel Prize winners, selectivity in admissions, generosity of alumni donors, and volume and quality of faculty research.

Among the elite top forty domestically and internationally ranked institutions identified by the QS 2026 rankings include six of the eight Ivy League schools; private universities Stanford, The University of Chicago, and Johns Hopkins; 1 of the 10 schools in the University of California system (UC Berkeley); and the research intensive schools Caltech and MIT.[135]

Other types of universities in the United States include liberal arts schools (Reed College, Swarthmore College, Barnard College), religiously affiliated and denomination universities (DePaul University, Brigham Young University, Yeshiva University), military (United States Military Academy, United States Merchant Marine Academy, United States Naval Academy), art and design schools (Berklee College of Music, Juilliard School, Fashion Institute of Technology, Parsons School of Design, Rhode Island School of Design), Historically black colleges and universities (Morehouse College, Howard University, Kentucky State University), and for-profit universities (University of Phoenix, Western International University, Liberty University).[136] While most private institutions are non-profit, a growing number in the past decade have been established as for-profit. The American university curriculum varies widely depending on the program and institution. Typically, an undergraduate student will be able to select an academic "major" or concentration, which comprises the core main or special subjects, and students may change their major one or more times.

Graduate degrees

[edit]Some students, typically those with a bachelor's degree, may choose to continue on to graduate or professional school, which are graduate and professional institutions typically attached to a university. Graduate degrees may be either master's degrees (e.g., M.A., M.S., M.S.W.), professional degrees (e.g. M.B.A., J.D., M.D.) or doctorate degrees (e.g. PhD). Programs range from full-time, evening and executive which allows for flexibility with students' schedules.[137] Academia-focused graduate school typically includes some combination of coursework and research (often requiring a thesis or dissertation to be written), while professional graduate-level schools grants a first professional degree. These include medical, law, business, education, divinity, art, journalism, social work, architecture, and engineering schools.

Vocational

[edit]Community and junior colleges in the United States are public comprehensive institutions that offer a wide range of educational services that generally lasts two years. Community colleges are generally publicly funded (usually by local cities or counties) and offer career certifications and part-time programs. Though it is cheaper in terms of tuition, less competitive to get into, and not as prestigious as going to a four-year university, they form another post-secondary option for students seeking to enter the realm of American higher education. Community and junior colleges generally emphasize practical career-oriented education that is focused on a vocational curriculum.[138] Though some community and junior colleges offer accredited bachelor's degree programs, community and junior colleges typically offer a college diploma or an associate degree such as an A.A., A.S., or a vocational certificate, although some community colleges offer a limited number of bachelor's degrees. Community and junior colleges also offer trade school certifications for skilled trades and technical careers. Students can also earn credits at a community or junior college and transfer them to a four-year university afterward. Many community colleges have relationships with four-year state universities and colleges or even private universities that enable some community college students to transfer to these universities to pursue a bachelor's degree after the completion of a two-year program at the community college.

Cost

[edit]

A few charity institutions cover all of the students' tuition, although scholarships (both merit-based and need-based) are widely available. Generally, private universities charge much higher tuition than their public counterparts, which rely on state funds to make up the difference.

Annual undergraduate tuition varies widely from state to state, and many additional fees apply. In 2009, the average annual tuition at a public university for residents of the state was $7,020.[131] Tuition for public school students from outside the state is generally comparable to private school prices, although students can often qualify for state residency after their first year. Private schools are typically much higher, although prices vary widely from "no-frills" private schools to highly specialized technical institutes. Depending upon the type of school and program, annual graduate program tuition can vary from $15,000 to as high as $50,000. Note that these prices do not include living expenses (rent, room/board, etc.) or additional fees that schools add on such as "activities fees" or health insurance. These fees, especially room and board, can range from $6,000 to $12,000 per academic year (assuming a single student without children).[141]

The mean annual total cost, including all costs associated with a full-time post-secondary schooling, such as tuition and fees, books and supplies, room and board, as reported by collegeboard.com for 2010:[142]

- Public university (4 years): $27,967 (per year)

- Private university (4 years): $40,476 (per year)

Total, four-year schooling:

- Public university: $111,868

- Private university: $161,904

College costs are rising at the same time that state appropriations for aid are shrinking. This has led to debate over funding at both the state and local levels. From 2002 to 2004 alone, tuition rates at public schools increased by over 14%, largely due to dwindling state funding. An increase of 6% occurred over the same period for private schools.[141] Between 1982 and 2007, college tuition and fees rose three times as fast as median family income, in constant dollars.[114]

From the U.S. Census Bureau, the median salary of an individual who has only a high school diploma is $27,967; the median salary of an individual who has a bachelor's degree is $47,345.[143] Certain degrees, such as in engineering, typically result in salaries far exceeding high school graduates, whereas degrees in teaching and social work fall below.[144]

The debt of the average college graduate for student loans in 2010 was $23,200.[145]

A 2010 study indicates that the return on investment for graduating from the top 1,000 colleges exceeds 4% over a high school degree.[146]

Student loan debt

[edit]In 2018, student loan debt topped $1.5 trillion. More than 40 million people hold college debt, which is largely owned by the U.S. government and serviced by private, for-profit companies such as Navient. Student loan debt has reached levels that have affected US society, reducing opportunities for millions of people following college.[147]

Academic labor and adjunctification

[edit]According to Uni in the USA, "One of the reasons American universities have thrived is due to their remarkable management of financial resources."[148] To combat costs colleges have hired adjunct professors to teach. In 2008, these teachers cost about $1,800 per 3-credit class as opposed to $8,000 per class for a tenured professor. Two-thirds of college instructors were adjuncts. There are differences of opinion on whether these adjuncts teach better or worse than regular professors. There is a suspicion that student evaluation of adjuncts, along with their subsequent continued employment, can lead to grade inflation.[149]

Credential inflation

[edit]Economics professor Alan Zagier blames credential inflation for the admission of so many unqualified students into college. He reports that the number of new jobs requiring college degrees is less than the number of college graduates.[85] He states that the more money that a state spends on higher education, the slower the economy grows, the opposite of long-held notions.[85] Other studies have shown that the level of cognitive achievement attained by students in a country (as measured by academic testing) is closely correlated with the country's economic growth, but that "increasing the average number of years of schooling attained by the labor force boosts the economy only when increased levels of school attainment also boost cognitive skills. In other words, it is not enough simply to spend more time in school; something has to be learned there."[150]

Governance and funding

[edit]

Governance

[edit]The national and state governments share power over public education, with the states exercising most of the control. Except for Hawaii, states delegate power to county, city or township-level school boards that exercise control over a school district. Some school districts may further delegate significant authority to principals, such as those who have adopted the Portfolio strategy.

The U.S. federal government exercises its control through its Department of Education. Though education is not mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, federal governments traditionally employ threats of decreased funding to enforce laws pertaining to education.[151] Under recent administrations, initiatives such as the No Child Left Behind Act and Race to the Top have attempted to assert more central control in a heavily decentralized system.

Nonprofit private schools are widespread, are largely independent of the government, and include secular as well as parochial schools. Educational accreditation decisions for private schools are made by voluntary regional associations.

Funding for K–12 schools

[edit]

According to a 2005 report from the OECD, the United States is tied for first place with Switzerland when it comes to annual spending per student on its public schools, with each of those two countries spending more than $11,000.[1] However, the United States is ranked 37th in the world in education spending as a percentage of gross domestic product.[152]

Government figures exist for education spending in the United States per student, and by state. They show a very wide range of expenditures and a steady increase in per-pupil funding since 2011.[153][154][155]

Changes in funding appear to have little effect on a school system's performance. Between 1970 and 2012, the full amount spent by all levels of government on the K–12 education of an individual public school student graduating in any given year, adjusted for inflation, increased by 185%. The average funding by state governments increased by 120% per student. However, scores in mathematics, science, and language arts over that same period remained almost unchanged. Multi-year periods in which a state's funding per student declined substantially also appear to have had little effect.[156]

Property taxes as a primary source of funding for public education have become highly controversial, for a number of reasons. First, if a state's population and land values escalate rapidly, many longtime residents may find themselves paying property taxes much higher than anticipated. In response to this phenomenon, California's citizens passed Proposition 13 in 1978, which severely restricted the ability of the Legislature to expand the state's educational system to keep up with growth. Some states, such as Michigan, have investigated or implemented alternative schemes for funding education that may sidestep the problems of funding based mainly on property taxes by providing funding based on sales or income tax. These schemes also have failings, negatively impacting funding in a slow economy.[157]

One of the biggest debates in funding public schools is funding by local taxes or state taxes. The federal government supplies around 8.5% of the public school system funds, according to a 2005 report by the National Center for Education Statistics.[158] The remaining split between state and local governments averages 48.7% from states and 42.8% from local sources.[158]

Rural schools struggle with funding concerns. State funding sources often favor wealthier districts. The state establishes a minimum flat amount deemed "adequate" to educate a child based on equalized assessed value of property taxes. This favors wealthier districts with a much larger tax base. This, combined with the history of slow payment in the state, leaves rural districts searching for funds. Lack of funding leads to limited resources for teachers. Resources that directly relate to funding include access to high-speed internet, online learning programs, and advanced course offerings.[159] These resources can enhance a student's learning opportunities, but may not be available to everyone if a district cannot afford to offer specific programs. One study found that school districts spend less efficiently in areas in which they face little or no competition from other public schools, in large districts, and in areas in which residents are poor or less educated.[160] Some public schools are experimenting with recruiting teachers from developing countries in order to fill the teacher shortage, as U.S. citizens with college degrees are turning away from the demanding, low paid profession.[161]

Currently, K-12 is funded through three primary sources: local, state, and federal funding. However, funding and allocations look different depending on the state. Most of the funding stems from state and local funds, contributing about 86% of the funding.[162] Most recent data reports that in 2022, the federal government funded about $119,089,043,000 while in 2023 $120,315,611,000 were allocated in their respective fiscal years.[163][164] In 2023 from local sources $403,427,498,000 and from state sources $422,757,839,000 were available.[164] Each fiscal year begins on October 1.

Federal funding is used for several different programs, including the hiring of staff and other services. Some of the programs funded are through Title 1, significant sums are provided to schools with a majority of low-income students. Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), funding is awarded to those with disabilities between the ages of 3 and 21. One other is the Child Nutrition Programs that provide free or reduced lunch.[162]

In most states, districts are notified by their state department of education of the amount of funding they will receive. Then, districts use money from their own accounts to make purchases according to spending guidelines. Then they draw down federal money from the state, which in turn draws the amount down from the federal government.[165] The federal government can freeze funding if there is evidence of civil rights violations or if there is fraud committed. Further from freezing funds, funds can also be cut.[166] This can be done through the False Claim Act (FCA). This is a federal statute enacted in 1863 due to contractor fraud during the American Civil War. This act ensures that any person who knowingly submits or causes to submit false claims to the government is liable for three times the government’s damages amount plus a penalty.[167]

Judicial intervention

[edit]Federal

[edit]The reliance on local funding sources has led to a long history of court challenges about how states fund their schools. These challenges have relied on interpretations of state constitutions after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that school funding was not a federal obligation specified in the U.S. Constitution, whose authors left education funding and the management to states. (San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973)). The state court cases, beginning with the California case of Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal.3d 584 (1971), were initially concerned with equity in funding, which was defined in terms of variations in spending across local school districts. More recently, state court cases have begun to consider what has been called 'adequacy.' These cases have questioned whether the total amount of spending was sufficient to meet state constitutional requirements.

From 1985 to 1999, a United States district court judge required the state of Missouri to triple the budget of Kansas City Public Schools, although in the end, test scores in the district did not rise; the racial achievement gap did not diminish; and there was less, not more, integration.[168] Perhaps the most famous adequacy case is Abbott v. Burke, 100 N.J. 269, 495 A.2d 376 (1985), which has involved state court supervision over several decades and has led to some of the highest spending of any U.S. districts in the so-called Abbott districts. The background and results of these cases are analyzed in a book by Eric Hanushek and Alfred Lindseth.[169] That analysis concludes that funding differences are not closely related to student outcomes and thus that the outcomes of the court cases have not led to improved policies.

State

[edit]Judicial intervention has even taken place at the state level. In McCleary v. Washington,[170] a Supreme Court decision that found the state had failed to "amply" fund public education for Washington's 1 million school children. Washington state had budgeted $18.2 billion for education spending in the two-year fiscal period ending in July 2015. The state Supreme Court decided that this budget must be boosted by $3.3 billion in total by July 2019. On September 11, 2014, the state Supreme Court found the legislature in contempt for failing to uphold a court order to come up with a plan to boost its education budget by billions of dollars over the next five years. The state had argued that it had adequately funded education and said diverting tax revenue could lead to shortfalls in other public services.[171]

In 2023, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania ruled in William Penn School District v. Pennsylvania Department of Education that the Pennsylvania General Assembly had created "manifest deficiencies" between high-wealth and low-wealth school districts with "no rational basis" for the funding gaps. The ruling stated that the Pennsylvania Constitution's Education Clause was "clearly, palpably, and plainly violated because of a failure to provide all students with access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education that will give them a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically."[172]

Pensions

[edit]While the hiring of teachers for public schools is done at the local school district level, the pension funds for teachers are usually managed at the state level. Some states have significant deficits when future requirements for teacher pensions are examined. In 2014, these were projected deficits for various states: Illinois -$187 billion, Connecticut -$57 billion, Kentucky -$41 billion, Hawaii -$16.5 billion, and Louisiana -$45.6 billion. These deficits range from 184% to 318% of these states' annual total budget.[173]

Funding for college

[edit]At the college and university level student loan funding is split in half; half is managed by the Department of Education directly, called the Federal Direct Student Loan Program (FDSLP). The other half is managed by commercial entities such as banks, credit unions, and financial services firms such as Sallie Mae, under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP). Some schools accept only FFELP loans; others accept only FDSLP. Still others accept both, and a few schools will not accept either, in which case students must seek out private alternatives for student loans.[174]

Grant funding is provided by the federal Pell Grant program.

Issues

[edit]Affirmative action

[edit]

| Acceptance rates at private universities (2005)[176] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall admit rate | Black admit rate | % difference | |

| Harvard | 10.0% | 16.7% | + 67.0% |

| MIT | 15.9% | 31.6% | + 98.7% |

| Brown | 16.6% | 26.3% | + 58.4% |

| Penn | 21.2% | 30.1% | + 42.0% |

| Georgetown | 22.0% | 30.7% | + 39.5% |

In 2023 the Supreme Court decision, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, the Supreme Court ruled that considering race as a factor in admitting students was a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. This decision overturned previous rulings that allowed colleges to consider race when accepting students.

African American academics Henry Louis Gates and Lani Guinier, while favoring affirmative action, have argued that in practice, it has led to recent black immigrants and their children being greatly overrepresented at elite institutions, at the expense of the historic African American community made up of descendants of slaves.[177]

Behavior

[edit]Corporal punishment

[edit]The United States is one of the very few developed countries where corporal punishment is legal in its public schools. Although the practice has been banned in an increasing number of states beginning in the 1970s, in 2024 only 33 out of 50 states have this ban and the remaining 17 states do not. The punishment virtually always consists of spanking the buttocks of a student with a paddle in a punishment known as "paddling."[178] Students can be physically punished from kindergarten to the end of high school, meaning that even adults who have reached the age of majority are sometimes spanked by school officials.[178]

Although extremely rare relative to the overall U.S. student population, more than 167,000 students were paddled in the 2011–2012 school year in American public schools.[179] Virtually all paddling in public schools occurs in the Southern United States, however, with 70% of paddled students living in just five states: Mississippi, Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia.[179] The practice has been on a steady decline in American schools.[180]

School safety and security

[edit]The National Center for Education Statistics reported statistics about public schools in the United States in 2013–2014. They stated that, during that time, 93% controlled access to their buildings during school hours, and that 88% have in place a written crisis response plan. They also reported that 82% of schools have a system that notifies parents in the event of an emergency. According to their report, 75% of schools have security cameras in use.[181]

During the 2015–16 school year in the United States, the National Center for Education Statistics reported the following: 9% of schools reported that one or more students had threatened a physical attack with a weapon. 95% of schools had given their students lockdown procedure drills, and 92% had drilled them on evacuation procedures.[182] Around 20% of schools had one or more security guards or security personnel while 10.9% had one or more full or part-time law enforcement officers. 42% of schools had at least one school resource officer.[182]

In some schools, a police officer, titled a school resource officer, is on site to screen students for firearms and to help avoid disruptions.[183][184][citation needed]

Some schools are fast adopting facial recognition technology, ostensibly "for the protection of children".[185] The technology is claimed by its proponents to be useful in detecting people falling on the threat list for sex offenses, suspension from school, and so on. However, human rights advocacy group, Human Rights Watch, argues that the technology could also threaten the right to privacy and could pose a great risk to children of color.[186]

Cheating

[edit]In 2022, an article by Waltzer reported that as many as 90% of students have cheated in high school.[187] They report that cheating involves a perception, evaluation, and decision step. The way that high schoolers perceive cheating at these steps determines their decision to cheat or not to cheat.[187] Opinions of what cheating is vary based on the teacher involved, the type of cheating, and the material being given. The various differences between teachers and assignments makes the line of academic cheating blurry.[187] In a study done, students were asked if they knew they were cheating at the time of their actions, and 54% of the students reported that they had not considered their actions cheating.[187] Students often explain their reasoning for cheating to be the "feasibility" of the task (they were unable to complete it without cheating), or the "extrinsic consequences" of the task (to achieve the grade they needed on the assignment).[187]

Literacy

[edit]Reading skills are typically taught using a three cues system based on identifying meaning, sentence structure, and visual information such as the first letter in a word.[188][189] This method has been criticized by psychologists such as Timothy Shanahan for lacking a basis in scientific evidence, citing studies that find that good readers look at all the letters in a word.[190] According to J. Richard Gentry, teachers draw insufficient attention to spelling. Spelling is itself frequently taught in a confusing manner, such as with reading prompts that may use words that are above grade level.[191]

Curriculum

[edit]

Curricula in the United States can vary widely from district to district. Different schools offer classes centering on different topics, and vary in quality. Some private schools even include religious classes as mandatory for attendance. This raises the question of government funding vouchers in states with anti-Catholic Blaine Amendments in their constitution. This in turn has produced camps of argument over the standardization of curricula and to what degree it should exist. These same groups often are advocates of standardized testing, which was mandated by the No Child Left Behind Act. The goal of No Child Left Behind was to improve the education system in the United States by holding schools and teachers accountable for student achievement, including the educational achievement gap between minority and non-minority children in public schools.

While the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) has served as an educational barometer for the US since 1969 by administering standardized tests on a regular basis to random schools throughout the United States, efforts over the last decade at the state and federal levels have mandated annual standardized test administration for all public schools across the country.[192]

Along with administering and scoring the annual standardized tests, in some cases the teachers are being scored on how well their own students perform on the tests. Teachers are under pressure to continuously raise scores to prove they are worthy of keeping their jobs. This approach has been criticized because there are so many external factors, such as domestic violence, hunger, and homelessness among students, that affect how well students perform.[193]

Schools that score poorly wind up being slated for closure or downsizing, which gives direct influence on the administration to result to dangerous tactics such as intimidation, cheating and drilling of information to raise scores.[194]

Uncritical use of standardized test scores to evaluate teacher and school performance is inappropriate, because the students' scores are influenced by three things: what students learn in school, what students learn outside of school, and the students' innate intelligence.[195] The school only has control over one of these three factors. Value-added modeling has been proposed to cope with this criticism by statistically controlling for innate ability and out-of-school contextual factors.[196][self-published source] In a value-added system of interpreting test scores, analysts estimate an expected score for each student, based on factors such as the student's own previous test scores, primary language, or socioeconomic status. The difference between the student's expected score and actual score is presumed to be due primarily to the teacher's efforts.

Content knowledge

[edit]There is debate over which subjects should receive the most focus, with astronomy and geography among those cited as not being taught enough in schools.[197][198][199] A major criticism of American educational curricula is that it overemphasizes mathematical and reading skills without providing the content knowledge needed to understand the texts used to teach the latter. Poor students are more likely to lack said content knowledge, which contributes to the achievement gap in the United States.[200]

English-language education

[edit]Schools in the 50 states, Washington, D.C., the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands teach primarily in English, with the exception of specialized language immersion programs.[citation needed]

In 2015, 584,000 students in Puerto Rico were taught in Spanish, their native language.[201]

The Native American Cherokee Nation instigated a 10-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee language from childhood on up through school immersion programs as well as a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at home.[202][203][204] [205] In 2010, 84 children were being educated in this manner.[206]

As of 2000, some 9.7 million children aged 5 to 17 primarily speak a language other than English at home. Of those, about 1.3 million children do not speak English well or at all.[207]

Mathematics

[edit]

According to a 1997 report by the U.S. Department of Education, passing rigorous high-school mathematics courses predicts successful completion of university programs regardless of major or family income.[208][209] Starting in 2010, mathematics curricula across the country have moved into closer agreement for each grade level. Unlike systems utilized in most other countries, the high school curricula is based around specialized courses (ex. Algebra 1; Geometry; Calculus) rather than integrated math ones. The SAT, a standardized university entrance exam, has been reformed to better reflect the contents of the Common Core.[210] As of 2023, twenty-seven states require students to pass three math courses before graduation from high school, and seventeen states and the District of Columbia require four.[211]

Sex education

[edit]

Almost all students in the U.S. receive some form of sex education at least once between grades 7 and 12; many schools begin addressing some topics as early as grades 4 or 5.[212] However, what students learn varies widely, because curriculum decisions are so decentralized. Many states have laws governing what is taught in sex education classes or allowing parents to opt out. Some state laws leave curriculum decisions to individual school districts.[213]

A 1999 study by the Guttmacher Institute found that most U.S. sex education courses in grades 7 through 12 cover puberty, HIV, STDs, abstinence, implications of teenage pregnancy, and how to resist peer pressure. Other studied topics, such as methods of birth control and infection prevention, sexual orientation, sexual abuse, and factual and ethical information about abortion, varied more widely.[214]

However, according to a 2004 survey, a majority of the 1,001 parent groups polled wants complete sex education in schools. The American people are heavily divided over the issue. Over 80% of polled parents agreed with the statement "Sex education in school makes it easier for me to talk to my child about sexual issues", while under 17% agreed with the statement that their children were being exposed to "subjects I don't think my child should be discussing". 10% believed that their children's sexual education class forced them to discuss sexual issues "too early". On the other hand, 49% of the respondents (the largest group) were "somewhat confident" that the values taught in their children's sex ed classes were similar to those taught at home, and 23% were less confident still. (The margin of error was plus or minus 4.7%.)[215]

According to The 74, an American education news website, the United States uses two methods to teach sex education. Comprehensive sex education focuses on sexual risk reduction. This method focuses on the benefits of contraception and safe sex. The abstinence-emphasized curriculum focuses on sexual risk avoidance, discouraging activity that could become a "gateway" to sexual activities.[216]

LGBT curriculum laws

[edit]At least 20 states have had their legislatures introduce derivative bills of the Florida Parental Rights in Education Act, including Arizona,[217] Georgia,[218] Iowa,[219][220] Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan,[221] Missouri,[222] Ohio,[223] Oklahoma,[224] Tennessee, and South Carolina.[225][226]

In April 2022, Alabama became the second state to pass a similar bill, with governor Kay Ivey signing House Bill 322, legislation which additionally requires all students to use either male or female bathrooms in Alabama public schools based on their sex. Some states have had similar provisions to Florida's law since the 1980s, though they have never gained the name of "Don't Say Gay" bills by critics until recently.[227][228]

Textbook review and adoption

[edit]In some states, textbooks are selected for all students at the state level, and decisions made by larger states, such as California and Texas, that represent a considerable market for textbook publishers and can exert influence over the content of textbooks generally, thereby influencing the curriculum taught in public schools.[229]

In 2010, the Texas Board of Education passed more than 100 amendments to the curriculum standards, affecting history, sociology, and economics courses to 'add balance' given that academia was 'skewed too far to the left'.[230] One specific result of these amendments is to increase education on Moses' influence on the founding of the United States, going as far as calling him a "founding father".[231] A critical review of the twelve most widely used American high school history textbooks argued that they often disseminate factually incorrect, Eurocentric, and mythologized views of American history.[232]

As of January 2009, the four largest college textbook publishers in the United States were: Pearson Education (including such imprints as Addison-Wesley and Prentice Hall), Cengage Learning (formerly Thomson Learning), McGraw-Hill Education, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.[citation needed] Other U.S. textbook publishers include: Abeka, BJU Press, John Wiley & Sons, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, F. A. Davis Company, W. W. Norton & Company, SAGE Publications, and Flat World Knowledge.

Immigrant students and grade placement