Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vault (architecture)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

In architecture, a vault (French voûte, from Italian volta) is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof.[1][2] As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while rings of voussoirs are constructed and the rings placed in position. Until the topmost voussoir, the keystone, is positioned, the vault is not self-supporting. Where timber is easily obtained, this temporary support is provided by centering consisting of a framed truss with a semicircular or segmental head, which supports the voussoirs until the ring of the whole arch is completed.[3]

The Mycenaeans (ca. 1800–1050 BC) were known for their tholos tombs, also called beehive tombs, which were underground structures with conical vaults. This type of vault is one of the earliest evidences of curved brick architecture without the use of stone arches, and its construction represented an innovative technique for covering circular spaces.

Vault types

[edit]Corbelled vaults, also called false vaults, with horizontally joined layers of stone have been documented since prehistoric times; in the 14th century BC from Mycenae. They were built regionally until modern times.

The real vault construction with radially joined stones was already known to the Egyptians and Assyrians and was introduced into the building practice of the West by the Etruscans. The Romans in particular developed vault construction further and built barrel, cross and dome vaults. Some outstanding examples have survived in Rome, e.g. the Pantheon and the Basilica of Maxentius.

Brick vaults have been used in Egypt since the early 3rd millennium BC, and were widely used by the end of the 8th century BC, when Keystone vaults were built.”. However, monumental temple buildings of the pharaonic culture in the Nile Valley did not use vaults, since even the huge portals with widths of more than 7 meters were spanned with cut stone beams.[4]

Dome

[edit]

Amongst the earliest known examples of any form of vaulting is to be found in the Neolithic village of Khirokitia on Cyprus.[citation needed] Dating from c. 6000 BCE, the circular buildings supported beehive shaped corbel domed vaults of unfired mud-bricks and also represent the first evidence for settlements with an upper floor. Similar beehive tombs, called tholoi, exist in Crete and Northern Iraq. Their construction differs from that at Khirokitia in that most appear partially buried and make provision for a dromos entry.

The inclusion of domes, however, represents a wider sense of the word vault. The distinction between the two is that a vault is essentially an arch which is extruded into the third dimension, whereas a dome is an arch revolved around its vertical axis.

Pitched brick barrel vault

[edit]

Pitched-brick vaults are named for their construction, the bricks are installed vertically (not radially) and are leaning (pitched) at an angle: This allows their construction to be completed without the use of centering. Examples have been found in archaeological excavations in Mesopotamia dating to the 2nd and 3rd millennium BCE,[3] which were set in gypsum mortar.

Barrel vault

[edit]

A barrel vault is the simplest form of a vault, semi-circular in cross-section,[5] and resembles a barrel or tunnel cut lengthwise in half. The effect is that of a structure composed of continuous semicircular or pointed sections.[6]

The earliest known examples of barrel vaults were built by the Sumerians, possibly under the ziggurat at Nippur in Babylonia,[7] which was built of fired bricks cemented with clay mortar.[8]

The earliest barrel vaults in ancient Egypt are thought to be those in the granaries built by the 19th dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II, the ruins of which are behind the Ramesseum, at Thebes.[9][10][11] The span was 12 feet (3.7 m) and the lower part of the arch was built in horizontal courses, up to about one-third of the height, and the rings above were inclined back at a slight angle, so that the bricks of each ring, laid flatwise, adhered till the ring was completed, no centering of any kind being required; the vault thus formed was elliptic in section, arising from the method of its construction. A similar system of construction was employed for the vault over the great hall at Ctesiphon, where the material employed was fired bricks or tiles of great dimensions, cemented with mortar; but the span was close upon 83 feet (25 m), and the thickness of the vault was nearly 5 feet (1.5 m) at the top, there being four rings of brickwork.[12]

Assyrian palaces used pitched-brick vaults, made with sun-dried mudbricks, for gates, subterranean graves and drains. During the reign of king Sennacherib they were used to construct aqueducts, such as those at Jerwan. In the provincial city Dūr-Katlimmu they were used to create vaulted platforms. The tradition of their erection, however, would seem to have been handed down to their successors in Mesopotamia, viz. to the Sassanians, who in their palaces in Sarvestan and Firouzabad built domes of similar form to those shown in the Nimrud sculptures, the chief difference being that, constructed in rubble stone and cemented with mortar, they still exist, though probably abandoned on the Islamic invasion in the 7th century.[12]

Groin vaults

[edit]

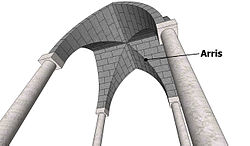

A groin vault is formed by the intersection of two barrel vaults at right angles, resulting in the formation of angles or groins along the lines of transition between the webs.[5][13] In these bays the longer transverse arches are semi-circular, as are the shorter longitudinal arches. The curvatures of these bounding arches were apparently used as the basis for the web centrings, which was created in the form of two intersecting tunnels as though each web was an arch projected horizontally in three dimensions.[13]

The earliest example is thought to be over a small hall at Pergamum, in Asia Minor, but its first employment over halls of great dimensions is due to the Romans. When two semicircular barrel vaults of the same diameter cross one another their intersection (a true ellipse) is known as a groin vault, down which the thrust of the vault is carried to the cross walls; if a series of two or more barrel vaults intersect one another, the weight is carried on to the piers at their intersection and the thrust is transmitted to the outer cross walls; thus in the Roman reservoir at Baiae, known as the Piscina Mirabilis, a series of five aisles with semicircular barrel vaults are intersected by twelve cross aisles, the vaults being carried on 48 piers and thick external walls. The width of these aisles being only about 13 feet (4.0 m) there was no great difficulty in the construction of these vaults, but in the Roman Baths of Caracalla the tepidarium had a span of 80 feet (24 m), more than twice that of an English cathedral, so that its construction both from the statical and economical point of view was of the greatest importance.[12][14] The researches of M. Choisy (L'Art de bâtir chez les Romains), based on a minute examination of those portions of the vaults which still remain in situ, have shown that, on a comparatively slight centering, consisting of trusses placed about 10 feet (3.0 m) apart and covered with planks laid from truss to truss, were laid – to begin with – two layers of the Roman brick (measuring nearly 2 feet (0.61 m) square and 2 in. thick); on these and on the trusses transverse rings of brick were built with longitudinal ties at intervals; on the brick layers and embedding the rings and cross ties concrete was thrown in horizontal layers, the haunches being filled in solid, and the surface sloped on either side and covered over with a tile roof of low pitch laid direct on the concrete. The rings relieved the centering from the weight imposed, and the two layers of bricks carried the concrete till it had set.[12]

As the walls carrying these vaults were also built in concrete with occasional bond courses of brick, the whole structure was homogeneous. One of the important ingredients of the mortar was a volcanic deposit found near Rome, known as pozzolana, which, when the concrete had set, not only made the concrete as solid as the rock itself, but to a certain extent neutralized the thrust of the vaults, which formed shells equivalent to that of a metal lid; the Romans, however, do not seem to have recognized the value of this pozzolana mixture, for they otherwise provided amply for the counteracting of any thrust which might exist by the erection of cross walls and buttresses. In the tepidaria of the Thermae and in the basilica of Constantine, in order to bring the thrust well within the walls, the main barrel vault of the hall was brought forward on each side and rested on detached columns, which constituted the principal architectural decoration. In cases where the cross vaults intersecting were not of the same span as those of the main vault, the arches were either stilted so that their soffits might be of the same height, or they formed smaller intersections in the lower part of the vault; in both of these cases, however, the intersections or groins were twisted, for which it was very difficult to form a centering, and, moreover, they were of disagreeable effect: though every attempt was made to mask this in the decoration of the vault by panels and reliefs modelled in stucco.[12]

Rib vault

[edit]

A rib vault is one in which all of the groins are covered by ribs or diagonal ribs in the form of segmental arches. Their curvatures are defined by the bounding arches. Whilst the transverse arches retain the same semi-circular profile as their groin-vaulted counterparts, the longitudinal arches are pointed with both arcs having their centres on the impost line. This allows the latter to correspond more closely to the curvatures of the diagonal ribs, producing a straight tunnel running from east to west.[15][5]

Reference has been made to the rib vault in Roman work, where the intersecting barrel vaults were not of the same diameter. Their construction must at all times have been somewhat difficult, but where the barrel vaulting was carried round over the choir aisle and was intersected (as in St Bartholomew-the-Great in Smithfield, London) by semicones instead of cylinders, it became worse and the groins more complicated. This would seem to have led to a change of system and to the introduction of a new feature, which completely revolutionized the construction of the vault. Hitherto the intersecting features were geometrical surfaces, of which the diagonal groins were the intersections, elliptical in form, generally weak in construction and often twisting. The medieval builder reversed the process, and set up the diagonal ribs first, which were utilized as permanent centres, and on these he carried his vault or web, which henceforward took its shape from the ribs. Instead of the elliptical curve which was given by the intersection of two semicircular barrel vaults, or cylinders, he employed the semicircular arch for the diagonal ribs; this, however, raised the centre of the square bay vaulted above the level of the transverse arches and of the wall ribs, and thus gave the appearance of a dome to the vault, such as may be seen in the nave of Sant'Ambrogio, Florence. To meet this, at first the transverse and wall ribs were stilted, or the upper part of their arches was raised, as in the Abbaye-aux-Hommes at Caen, and the Abbey of Lessay, in Normandy. The problem was ultimately solved by the introduction of the pointed arch for the transverse and wall ribs – the pointed arch had long been known and employed, on account of its much greater strength and of the less thrust it exerted on the walls. When employed for the ribs of a vault, however narrow the span might be, by adopting a pointed arch, its summit could be made to range in height with the diagonal rib; and, moreover, when utilized for the ribs of the annular vault, as in the aisle round the apsidal termination of the choir, it was not necessary that the half ribs on the outer side should be in the same plane as those of the inner side; for when the opposite ribs met in the centre of the annular vault, the thrust was equally transmitted from one to the other, and being already a broken arch the change of its direction was not noticeable.[16]

The first introduction of the pointed arch rib took place at Cefalù Cathedral and pre-dated the abbey of Saint-Denis. Whilst the pointed rib-arch is often seen as an identifier for Gothic architecture, Cefalù is a Romanesque cathedral whose masons experimented with the possibility of Gothic rib-arches before it was widely adopted by western church architecture.[17] Besides Cefalù Cathedral, the introduction of the pointed arch rib would seem to have taken place in the choir aisles of the abbey of Saint-Denis, near Paris, built by the abbot Suger in 1135. It was in the church at Vezelay (1140) that it was extended to the square bay of the porch. As has been pointed out, the aisles had already in the early Christian churches been covered over with groined vaults, the only advance made in the later developments being the introduction of transverse ribs' dividing the bays into square compartments. In the 12th century[18] the first attempts were made to vault over the naves, which were twice the width of the aisles, so it became necessary to include two bays of the aisles to form one rectangular bay in the nave (although this is often mistaken as square).[15] It followed that every alternate pier served no purpose, so far as the support of the nave vault was concerned, and this would seem to have suggested an alternative to provide a supplementary rib across the church and between the transverse ribs. This resulted in what is known as a sexpartite, or six-celled vault, of which one of the earliest examples is found in the Abbaye-aux-Hommes at Caen. This church, built by William the Conqueror, was originally constructed to carry a timber roof only, but nearly a century later the upper part of the nave walls were partly rebuilt, in order that it might be covered with a vault. The immense size, however, of the square vault over the nave necessitated some additional support, so that an intermediate rib was thrown across the church, dividing the square compartment into six cells, and called the sexpartite vault The intermediate rib, however, had the disadvantage of partially obscuring one side of the clerestory windows, and it threw unequal weights on the alternate piers, so that in the cathedral of Soissons (1205) a quadripartite or four-celled vault was introduced, the width of each bay being half the span of the nave, and corresponding therefore with the aisle piers. To this there are some exceptions, in Sant' Ambrogio, Milan, and San Michele, Pavia (the original vault), and in the cathedrals of Speyer, Mainz and Worms, where the quadripartite vaults are nearly square, the intermediate piers of the aisles being of much smaller dimensions. In England sexpartite vaults exist at Canterbury (1175) (set out by William of Sens), Rochester (1200), Lincoln (1215), Durham (east transept), and St. Faith's chapel, Westminster Abbey.[16]

In the earlier stage of rib vaulting, the arched ribs consisted of independent or separate voussoirs down to the springing; the difficulty, however, of working the ribs separately led to two other important changes: (1) the lower part of the transverse diagonal and wall ribs were all worked out of one stone; and (2) the lower horizontal, constituting what is known as the tas-de-charge or solid springer. The tas-de-charge, or solid springer, had two advantages: (1) it enabled the stone courses to run straight through the wall, to bond the whole together much better; and (2) it lessened the span of the vault, which then required a centering of smaller dimensions. As soon as the ribs were completed, the web or stone shell of the vault was laid on them. In some English work each course of stone was of uniform height from one side to the other; but, as the diagonal rib was longer than either the transverse or wall rib, the courses dipped towards the former, and at the apex of the vault were cut to fit one another. In the early English Gothic period, in consequence of the great span of the vault and the very slight rise or curvature of the web, it was thought better to simplify the construction of the web by introducing intermediate ribs between the wall rib and the diagonal rib and between the diagonal and the transverse ribs; and in order to meet the thrust of these intermediate ribs a ridge rib was required, and the prolongation of this rib to the wall rib hid the junction of the web at the summit, which was not always very sightly, and constituted the ridge rib. In France, on the other hand, the web courses were always laid horizontally, and they are therefore of unequal height, increasing towards the diagonal rib. Each course also was given a slight rise in the centre, so as to increase its strength; this enabled the French masons to dispense with the intermediate rib, which was not introduced by them till the 15th century, and then more as a decorative than a constructive feature, as the domical form given to the French web rendered unnecessary the ridge rib, which, with some few exceptions, exists only in England. In both English and French vaulting centering was rarely required for the building of the web, a template (Fr. cerce) being employed to support the stones of each ring until it was complete. In Italy, Germany and Spain the French method of building the web was adopted, with horizontal courses and a domical form. Sometimes, in the case of comparatively narrow compartments, and more especially in clerestories, the wall rib was stilted, and this caused a peculiar twisting of the web, where the springing of the wall rib is at K: to these twisted surfaces the term ploughshare vaulting is given.[19]

One of the earliest examples of the introduction of the intermediate rib is found in the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, and there the ridge rib is not carried to the wall rib. It was soon found, however, that the construction of the web was much facilitated by additional ribs, and consequently there was a tendency to increase their number, so that in the nave of Exeter Cathedral three intermediate ribs were provided between the wall rib and the diagonal rib. To mask the junction of the various ribs, their intersections were ornamented with richly carved bosses, and this practice increased on the introduction of another short rib, known as the lierne, a term in France given to the ridge rib. Lierne ribs are short ribs crossing between the main ribs, and were employed chiefly as decorative features, as, for instance, in the Liebfrauenkirche (1482) of Mühlacker, Germany. One of the best examples of Lierne ribs exists in the vault of the oriel window of Crosby Hall, London. The tendency to increase the number of ribs led to singular results in some cases, as in the choir of Gloucester Cathedral, where the ordinary diagonal ribs become mere ornamental mouldings on the surface of an intersected pointed barrel vault, and again in the cloisters, where the introduction of the fan vault, forming a concave-sided conoid, returned to the principles of the Roman geometrical vault. This is further shown in the construction of these fan vaults, for although in the earliest examples each of the ribs above the tas-de-charge was an independent feature, eventually it was found easier to carve them and the web out of the solid stone, so that the rib and web were purely decorative and had no constructional or independent functions.[20]

Fan vault

[edit]

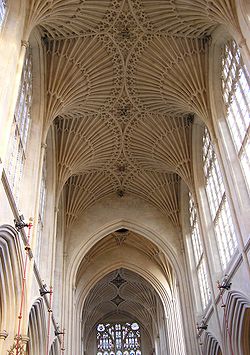

This form of vaulting is found in English late Gothic in which the vault is constructed as a single surface of dressed stones, with the ribs radiating from the springing point resembling a fan, and the resulting conoid forming an ornamental network of blind tracery.[13][5]

The fan vault would seem to have owed its origin to the employment of centerings of one curve for all the ribs, instead of having separate centerings for the transverse, diagonal wall and intermediate ribs; it was facilitated also by the introduction of the four-centred arch, because the lower portion of the arch formed part of the fan, or conoid, and the upper part could be extended at pleasure with a greater radius across the vault. These ribs were often cut from the same stones as the webs, with the entire vault being treated as a single jointed surface covered in interlocking tracery.[21]

The earliest example is perhaps the east walk of the cloister at Gloucester, with its surface consisting of intricately decorated panels of stonework forming conical structures that rise from the springers of the vault.[21][22] In later examples, as in King's College Chapel, Cambridge, on account of the great dimensions of the vault, it was found necessary to introduce transverse ribs, which were required to give greater strength. Similar transverse ribs are found in Henry VII's chapel and in the Divinity School at Oxford, where a new development presented itself. One of the defects of the fan vault at Gloucester is the appearance it gives of being half sunk in the wall; to remedy this, in the two buildings just quoted, the complete conoid is detached and treated as a pendant.[20]

Byzantine vaults and domes

[edit]

The vault of the Basilica of Maxentius, completed by Constantine, was the last great work carried out in Rome before its fall, and two centuries pass before the next important development is found in the Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) at Constantinople. Probably, the realization of the great advance in the science of vaulting shown in this church owed something to the eastern tradition of dome vaulting seen in the Assyrian domes, which are known to us only by the representations in the bas-relief from Nimrud, because in the great water cisterns in Istanbul, known as the Basilica Cistern and Bin bir direk (cistern with a thousand and one columns), we find the intersecting groin vaults of the Romans already replaced by small cupolas or domes. These domes, however, are of small dimensions when compared with that projected and carried out by Justinian in the Hagia Sophia. Previous to this the greatest dome was that of the Pantheon at Rome, but this was carried on an immense wall 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, and except small niches or recesses in the thickness of the wall could not be extended, so that Justinian apparently instructed his architect to provide an immense hemicycle or apse at the eastern end, a similar apse at the western end, and great arches on either side, the walls under which would be pierced with windows.[23] Unlike the Pantheon dome, the upper portions of which are made of concrete, Byzantine domes were made of brick, which were lighter and thinner, but more vulnerable to the forces exerted onto them.

The diagram shows the outlines of the solution of the problem. If a hemispherical dome is cut by four vertical planes, the intersection gives four semicircular arches; if cut in addition by a horizontal plane tangent to the top of these arches, it describes a circle; that portion of the sphere which is below this circle and between the arches, forming a spherical spandrel, is the pendentive, and its radius is equal to the diagonal of the square on which the four arches rest. Having obtained a circle for the base of the dome, it is not necessary that the upper portion of the dome should spring from the same level as the arches, or that its domical surface should be a continuation of that of the pendentive. The first and second dome of the Hagia Sophia fell, so that Justinian determined to raise it, possibly to give greater lightness to the structure, but mainly in order to obtain increased light for the interior of the church. This was effected by piercing it with forty windows – the effect of which, as the light streaming through these windows, gave the dome the appearance of being suspended in the air. The pendentive which carried the dome rested on four great arches, the thrust of those crossing the church being counteracted by immense buttresses which traversed the aisles, and the other two partly by smaller arches in the apse, the thrust being carried to the outer walls, and to a certain extent by the side walls which were built under the arches. From the description given by Procopius we gather that the centering employed for the great arches consisted of a wall erected to support them during their erection. The construction of the pendentives is not known, but it is surmised that to the top of the pendentives they were built in horizontal courses of brick, projecting one over the other, the projecting angles being cut off afterwards and covered with stucco in which the mosaics were embedded; this was the method employed in the erection of the Périgordian domes, to which we shall return; these, however, were of less diameter than those of the Hagia Sophia, being only about 40 to 60 feet (18 m) instead of 107 feet (33 m) The apotheosis of Byzantine architecture was reached in Hagia Sophia, for although it formed the model on which all subsequent Byzantine churches were based, so far as their plan was concerned, no domes approaching the former in dimensions were even attempted. The principal difference in some later examples is that which took place in the form of the pendentive on which the dome was carried. Instead of the spherical spandril of Hagia Sophia, large niches were formed in the angles, as in the Mosque of Damascus, which was built by Byzantine workmen for the Al-Walid I in CE 705; these gave an octagonal base on which the hemispherical dome rested; or again, as in the Sassanian palaces of Sarvestan and Firouzabad of the 4th and 5th century, when a series of concentric arch rings, projecting one in front of the other, were built, giving also an octagonal base; each of these pendentives is known as a squinch.[23]

There is one other remarkable vault, also built by Justinian, in the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Constantinople. The central area of this church was octagonal on plan, and the dome is divided into sixteen compartments; of these eight consist of broad flat bands rising from the centre of each of the walls, and the alternate eight are concave cells over the angles of the octagon, which externally and internally give to the roof the appearance of an umbrella.[23]

Romanesque

[edit]

Although the dome constitutes the principal characteristic of the Byzantine church, throughout Asia Minor are numerous examples in which the naves are vaulted with the semicircular barrel vault, and this is the type of vault found throughout the south of France in the 11th and 12th centuries, the only change being the occasional substitution of the pointed barrel vault, adopted not only on account of its exerting a less thrust, but because, as pointed out by Fergusson (vol. ii. p. 46), the roofing tiles were laid directly on the vault and a less amount of filling in at the top was required.[23]

The continuous thrust of the barrel vault in these cases was met either by semicircular or pointed barrel vaults on the aisles, which had only half the span of the nave; of this there is an interesting example in the Chapel of Saint John in the Tower of London – and sometimes by half-barrel vaults. The great thickness of the walls, however, required in such constructions would seem to have led to another solution of the problem of roofing over churches with incombustible material, viz. that which is found throughout Périgord and La Charente, where a series of domes carried on pendentives covered over the nave, the chief peculiarities of these domes being the fact that the arches carrying them form part of the pendentives, which are all built in horizontal courses.[24]

The intersecting and groined vault of the Romans was employed in the early Christian churches in Rome, but only over the aisles, which were comparatively of small span, but in these there was a tendency to raise the centres of these vaults, which became slightly domical; in all these cases centering was employed.[16]

Gothic Revival and the Renaissance

[edit]

One good example of the fan vault is that over the staircase leading to the hall of Christ Church, Oxford, where the complete conoid is displayed in its centre carried on a central column. This vault, not built until 1640, is an example of traditional workmanship, probably in Oxford transmitted in consequence of the late vaulting of the entrance gateways to the colleges. Fan vaulting is peculiar to England, the only example approaching it in France being the pendant of the Lady-chapel at Caudebec-en-Caux, in Normandy.[20]

In France, Germany, and Spain the multiplication of ribs in the 15th century led to decorative vaults of various kinds, but with some singular modifications. Thus, in Germany, recognizing that the rib was no longer a necessary constructive feature, they cut it off abruptly, leaving a stump only; in France, on the other hand, they gave still more importance to the rib, by making it of greater depth, piercing it with tracery and hanging pendants from it, and the web became a horizontal stone paving laid on the top of these decorated vertical webs. This is the characteristic of the great Renaissance work in France and Spain; but it soon gave way to Italian influence, when the construction of vaults reverted to the geometrical surfaces of the Romans, without, however, always that economy in centering to which they had attached so much importance, and more especially in small structures. In large vaults, where it constituted an important expense, the chief boast of some of the most eminent architects has been that centering was dispensed with, as in the case of the dome of the Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, built by Filippo Brunelleschi, and Ferguson cites as an example the great dome of the church at Mousta in Malta, erected in the first half of the 19th century, which was built entirely without centering of any kind.[25]

Vaulting and faux-vaulting in the Renaissance and after

[edit]It is important to note that whereas Roman vaults, like that of the Pantheon, and Byzantine vaults, like that at Hagia Sophia, were not protected from above (i.e. the vault from the inside was the same that one saw from the outside), the European architects of the Middle Ages protected their vaults with wooden roofs. In other words, one will not see a Gothic vault from the outside. The reasons for this development are hypothetical, but the fact that the roofed basilica form preceded the era when vaults begin to be made is certainly to be taken into consideration. In other words, the traditional image of a roof took precedence over the vault.

The separation between interior and exterior – and between structure and image – was to be developed very purposefully in the Renaissance and beyond, especially once the dome became reinstated in the Western tradition as a key element in church design. Michelangelo's dome for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, as redesigned between 1585 and 1590 by Giacomo della Porta, for example, consists of two domes of which, however, only the inner is structural. Baltasar Neumann, in his baroque churches, perfected light-weight plaster vaults supported by wooden frames.[26] These vaults, which exerted no lateral pressures, were perfectly suited for elaborate ceiling frescoes. In St Paul's Cathedral in London there is a highly complex system of vaults and faux-vaults.[27] The dome that one sees from the outside is not a vault, but a relatively light-weight wooden-framed structure resting on an invisible – and for its age highly original – catenary vault of brick, below which is another dome, (the dome that one sees from the inside), but of plaster supported by a wood frame. From the inside, one can easily assume that one is looking at the same vault that one sees from the outside.

India

[edit]

There are two distinctive "other ribbed vaults" (called "Karbandi" in Persian) in India which form no part of the development of European vaults, but have some unusual features; one carries the central dome of the Jumma Musjid at Bijapur (A.D. 1559), and the other is Gol Gumbaz, the tomb of Muhammad Adil Shah II (1626–1660) in the same town. The vault of the latter was constructed over a hall 135 feet (41 m) square, to carry a hemispherical dome. The ribs, instead of being carried across the angles only, thus giving an octagonal base for the dome, are carried across to the further pier of the octagon and consequently intersect one another, reducing the central opening to 97 feet (30 m) in diameter, and, by the weight of the masonry they carry, serving as counterpoise to the thrust of the dome, which is set back to leave a passage about 12 feet (3.7 m) wide round the interior. The internal diameter of the dome is 124 feet (38 m), its height 175 feet (53 m) and the ribs struck from four centres have their springing 57 feet (17 m) from the floor of the hall. The Jumma Musjid dome was of smaller dimensions, on a square of 70 feet (21 m) with a diameter of 57 feet (17 m), and was carried on piers only instead of immensely thick walls as in the tomb; but any thrust which might exist was counteracted by its transmission across aisles to the outer wall.[28]

Islamic architecture

[edit]The Muqarnas is a form of vaulting common in Islamic architecture.

Modern vaults

[edit]

Hyperbolic paraboloids

[edit]The 20th century saw great advances in reinforced concrete design. The advent of shell construction and the better mathematical understanding of hyperbolic paraboloids allowed very thin, strong vaults to be constructed with previously unseen shapes. The vaults in the Church of Saint Sava are made of prefabricated concrete boxes. They were built on the ground and lifted to 40 m on chains.

Vegetal vault

[edit]When made by plants or trees, either artificially or grown on purpose by humans, structures of this type are called tree tunnels.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Vault". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ^ Reich, Ronny; Katzenstein, Hannah (1992). "Glossary of Archaeological Terms". In Kempinski, Aharon; Reich, Ronny (eds.). The Architecture of Ancient Israel. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society. p. 322. ISBN 978-965-221-013-5.

Vault: Arched roof made of stones or bricks in the shape of a half cylinder.

- ^ a b Lynne C. Lancaster, "Early Examples of So-Called Pitched Brick Barrel Vaulting in Roman Greece and Asia Minor: A Question of Origin and Intention"

- ^ "Niederschlag in Ägypten", Der Starke auf dem Dach, Harrassowitz, O, pp. 7–18, 2015-01-02, doi:10.2307/j.ctvbqs925.6, retrieved 2022-03-26

- ^ a b c d "Architecture". The Ultimate Visual Family Dictionary. New Delhi: DK Pub. 2012. p. 484-485. ISBN 978-0-1434-1954-9.

- ^ "Glossary of Medieval Art and Architecture – barrel vault or tunnel vault". University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ Spiers (1911) states that the vaults under the ziggurat were 4000 BCE; more recent scholarship revises the date forward considerably but imprecisely, and casts doubt on the methodology and conclusions of the original excavations of 1880. See Gibson, McGuire (1992). "Patterns of Occupation at Nippur". The Oriental Institute of The University of Chicago. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ Spiers 1911, p. 956.

- ^ Willockx, Sjef (2003) Building in stone in Ancient Egypt, Part 1: Columns and Pillars

- ^ Photograph of the barrel vaults at the Ramesseum

- ^ Architectural elements used by ancient Egyptian builders

- ^ a b c d e Spiers 1911, p. 957.

- ^ a b c Buchanan, Alexandrina; Hillson, James; Webb, Nicholas (2021). Digital Analysis of Vaults in English Medieval Architecture. Routledge. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-351-01127-3.

- ^ Artlex Art Dictionary

- ^ a b Buchanan, Alexandrina; Hillson, James; Webb, Nicholas (2021). Digital Analysis of Vaults in English Medieval Architecture. Routledge. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-1-351-01127-3.

- ^ a b c Spiers 1911, p. 959.

- ^ "Basic architectural history course" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-30. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ Transverse ribs under the vaulting surfaces had been employed from very early times by the Romans, and utilized as permanent stone centerings for their vaults; perhaps the earliest examples are those in the corridor of the Tabularium in Rome, which is divided into square bays, each vaulted with a cloister dome. Transverse ribs are also found in the Roman Piscinae and in the Nymphaeum at Nimes; they were not introduced by the Romanesque masons till the 11th century.

- ^ Spiers 1911, pp. 959–960.

- ^ a b c Spiers 1911, p. 960.

- ^ a b Buchanan, Alexandrina; Hillson, James; Webb, Nicholas (2021). Digital Analysis of Vaults in English Medieval Architecture. Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-351-01127-3.

- ^ "Gloucester – Tracing the Past: Medieval Vaults". Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ a b c d Spiers 1911, p. 958.

- ^ Spiers 1911, pp. 958–959.

- ^ Spiers 1911, pp. 960–961.

- ^ Maren Holst. Studien zu Balthasar Neumanns Wölbformen (Mittenwald: Mäander, 1981).

- ^ Hart, Vaughan (1995). St. Paul's Cathedral: Sir Christopher Wren. London: Phaidon Press.

- ^ Spiers 1911, p. 961.

Sources

[edit]- Copplestone, Trewin. (ed). (1963). World architecture – An illustrated history. Hamlyn, London.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Spiers, R. Phené (1911). "Vault". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 956–961.

Further reading

[edit]- Block, Philippe, (2005) Equilibrium Systems, studies in masonry structure.

- Severy, Ching, Francis D. K. (1995). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. p. 262. ISBN 0-442-02462-2

External links

[edit]- Documentation on Arches, Domes and Vaults on the Auroville Earth Institute website

- Tracing the past: 3D analysis of medieval vaults, a talk for the British Archaeological Association by Dr Alex Buchanan, Dr James Hillson, and Dr Nick Webb

Vault (architecture)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Purpose

In architecture, a vault is an arched structure whose concavity faces the interior of the space it covers, typically constructed from stone, brick, or other materials to form a self-supporting ceiling or roof that spans an area without relying on flat beams or slabs.[6] This curved form extends the principle of the arch in depth, allowing for the enclosure of expansive interiors while distributing structural loads efficiently to supporting walls or piers.[7] The primary purpose of a vault is to cover large open spaces—such as halls, churches, and tombs—without the need for numerous internal columns, thereby creating unobstructed, lofty enclosures that enhance both functionality and visual grandeur.[6] By channeling weight downward through its curved profile, a vault enables the construction of monumental buildings that emphasize height and volume, as seen in ancient burial chambers and civic structures where it provided durable overhead protection.[8]Structural Principles

Vaults in architecture function by transferring compressive forces along their curved surfaces to supporting abutments or buttresses, enabling the spanning of large spaces without internal supports. This load distribution relies on the principle of the thrust line, which traces the path of resultant forces through the masonry; for stability, the thrust line must remain entirely within the vault's cross-section to ensure uniform compression and prevent tensile stresses that masonry cannot withstand. Lateral support is essential, as vaults generate outward horizontal thrusts that, if unresisted, can cause spreading or collapse; abutments or additional buttresses counter these forces by providing the necessary resistance.[9][10] The key mechanics of vaults derive from the arch principle, where wedge-shaped stones known as voussoirs are arranged in curved courses to form the vault's surface. Equilibrium is achieved geometrically: vertical loads from the vault's self-weight and superimposed elements are balanced by horizontal thrusts at the springing points, creating a state where the sum of forces equals zero and all stresses are compressive. This self-supporting nature emerges only upon completion, as the interlocking voussoirs mutually stabilize each other, with the central keystone often locking the structure in place.[10][9] Construction techniques emphasize precision and temporary support. Centering—temporary wooden frameworks—is erected from the springing line (the base of the curve) upward to hold the voussoirs in position during assembly, allowing sequential layering until the vault closes at the ridge or crown; once complete, the centering is removed, and the structure assumes its load. Corbelling served as an earlier precursor method, involving stepped, overhanging courses of stone or brick to approximate a vault without true curvature, though less efficient for load transfer. Building proceeds in phases, often starting with perimeter walls and rising vaults bay by bay to maintain stability.[10][11] Traditional materials for vaults include cut stone such as limestone or sandstone for durable, load-bearing elements like ribs and webs, with brick used in regions lacking suitable stone; mortar, typically a lime-sand mix, binds the units and fills joints to distribute loads evenly. Early vaults employed solid masonry for mass and strength, but evolved toward lighter ribbed forms in later periods, where skeletal ribs of stone supported thinner infill panels, reducing material use while maintaining structural integrity.[12][10] Stability challenges in vaults include spreading (outward movement of supports) and buckling under uneven loads or settlement, which can shift the thrust line outside the masonry and initiate cracks or hinges leading to partial collapse. These issues are mitigated by incorporating ties (metal or wooden rods) to restrain horizontal thrusts or by external flying buttresses that redirect forces to the ground, often comprising a significant portion of the overall structure's mass.[10][9]Types of Vaults

Barrel Vault

The barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, represents the simplest form of arched vaulting in architecture, characterized by a continuous semicircular or pointed cross-section extended longitudinally to create a tunnel-like enclosure. This geometry forms a semi-cylindrical shape, resembling a barrel halved lengthwise, where the curve is uniform along its length and typically features a consistent radius or profile, though variations such as elliptical or segmental arches can occur for aesthetic or structural adjustments. The vault's profile derives from the extrusion of a single arch curve, resulting in a structure that curves in one direction only, spanning rectangular or linear spaces without intersections.[13][14] Construction of a barrel vault involves erecting the arched form in segments over temporary wooden centering, a scaffold that supports the masonry or concrete until the mortar sets and the structure becomes self-supporting. Materials historically include brick, stone, or concrete, laid in courses that follow the curve, with a uniform thickness to distribute loads evenly; end walls, transverse arches, or buttresses are essential to counter the outward thrust generated along the haunches. In Roman practice, concrete (opus caementicium) allowed for monolithic pours over centering, enabling longer spans, while earlier methods relied on pitched bricks or mud bricks laid in rings to approximate the curve. The process demands precise alignment to manage lateral forces, often requiring thicker walls at the base for stability.[14][15][16] Barrel vaults offer advantages in spanning long distances—up to tens of meters in ancient examples—while supporting heavier loads than flat roofs or lintels, thus facilitating expansive, uninterrupted interiors ideal for corridors, halls, or basilicas. Their compressive strength efficiently transfers weight to the supports, and the addition of transverse ribs can reduce material use and enhance rigidity. However, limitations include the creation of narrow, tunnel-like spaces that restrict natural light admission except through end openings or elevated clerestory windows, which can weaken the structure if not carefully integrated; the continuous outward thrust also necessitates robust abutments, potentially leading to buckling without adequate buttressing, and limits flexibility for complex floor plans.[14][15] Early applications trace to Mesopotamian architecture around the 18th century BCE, where rudimentary barrel vaults constructed from mud bricks formed roofs over tombs and drains, as seen in structures at Tell al-Rimah. In Roman architecture, the form reached monumental scale using concrete, exemplified in the barrel-vaulted halls of the Baths of Caracalla, completed around 216 CE, which spanned over 20 meters in width to cover vast bathing complexes. These precursors highlight the vault's evolution from basic enclosures to engineered spans for public infrastructure.[3][17]Groin Vault

A groin vault, also known as a cross vault, is formed by the intersection at right angles of two or more barrel vaults of equal height, resulting in a structure that covers square or rectangular bays efficiently.[1] The crossing produces prominent diagonal edges called groins or arrises, where the curved surfaces of the barrel vaults meet, creating a series of semi-elliptical sections along these lines that distribute structural forces toward the corners of the supporting piers.[18] This geometry allows architects to "square the circle" in plan, adapting to polygonal or irregular spaces while maintaining stability over spans typically ranging from 10 to 25 meters in ancient applications.[19] In construction, groin vaults were typically erected quadrant by quadrant over temporary wooden centering to support the masonry or concrete until the mortar set, with thrusts concentrated along the groins necessitating robust piers or walls at the corners to counter lateral forces.[18] Roman builders often employed opus caementicium—a pozzolana-based concrete—for seamless, monolithic forms, sometimes reinforced with hidden brick ribs along the groins to mitigate cracking, as seen in large-scale imperial projects.[19] By the Romanesque period, stone construction predominated, with vaults laid in courses following the curve, though the process remained labor-intensive due to the need for precise alignment to avoid uneven settling.[20] Compared to a single barrel vault, the groin vault offers greater flexibility in architectural layouts, enabling the roofing of intersecting spaces like naves and transepts without continuous lateral buttressing along the entire length, and it facilitates better light distribution through side windows since thrusts are localized at the four corners rather than distributed linearly.[18] This design also reduces overall material use, as the intersecting form eliminates redundant coverage over rectangular areas that would require multiple aligned barrel vaults, achieving spans with thinner webs (around 0.20 meters for 10-15 meter bays).[19] Prominent Roman examples include the groin vaults in the vestibule of the Pantheon (c. 126 CE), which transition from the portico to the rotunda, and larger applications in the Baths of Diocletian (c. 298-306 CE) and the Basilica of Maxentius (c. 312 CE), where they spanned vast halls over 25 meters.[21][1] In the Romanesque era, groin vaults became widespread in basilican churches across Europe, such as those in central Italian structures like the Basilica of San Miniato al Monte in Florence (11th century) and Norman examples in England, providing unified roofing for naves and aisles in early medieval cathedrals.[20]Rib Vault

The rib vault represents a significant advancement in medieval vaulting techniques, consisting of a skeletal framework of arched ribs that support thin stone or brick infill panels, known as severies, spanning the spaces between them. This design evolved from the earlier groin vault, which relied on continuous masonry at intersections for strength, by introducing discrete ribs to concentrate structural loads along defined lines.[22] The primary ribs include transverse arches running parallel to the nave's length, diagonal ribs crossing at the center of each bay, and sometimes wall ribs along the edges, forming a geometric skeleton that dictates the vault's overall form.[23] Early rib vaults were typically quadripartite, dividing each rectangular bay into four triangular severies meeting at a central boss, as seen in transitional Romanesque-Gothic structures. Over time, designs progressed to sexpartite vaults, which incorporated additional intermediate ribs to divide the bays into six sections for better load distribution in wider spaces, and later to more complex liérne vaults featuring short intermediary ribs connecting the main ribs without reaching the central boss, enhancing both stability and aesthetic intricacy. These evolutions allowed for irregular bay shapes and greater experimentation in vault profiling.[24] In construction, the ribs were erected first using temporary wooden centering, after which they served as permanent centering to support the lightweight severies laid between them, enabling efficient assembly without extensive temporary scaffolding. This method facilitated taller rises, as the pointed arches commonly used in ribs directed thrusts more vertically to the supporting piers. The advantages of rib vaults included significantly lighter overall weight compared to solid masonry vaults, permitting faster construction and reduced material use while achieving unprecedented heights. By channeling forces along the ribs to clustered columns or piers, they minimized lateral thrust on walls, allowing for thinner masonry and the enlargement of windows to admit more light through stained glass. This structural efficiency was pivotal in enabling the vertical emphasis and luminous interiors characteristic of Gothic architecture.[22][23] Prominent examples include the early rib vaults in the choir aisles of Durham Cathedral, constructed around 1096 CE, marking one of the first uses in England with simple quadripartite designs that demonstrated the potential for height in Romanesque settings. The form was refined in High Gothic cathedrals such as Chartres, where four-part ribbed groin vaults, built between approximately 1194 and 1220 CE from solid limestone, rose to support a nave height of 37 meters, integrating seamlessly with pointed arches and colonnettes for enhanced verticality.[25][23]Dome

A dome is a vaulted structure characterized by its rotational geometry, typically forming a hemispherical or onion-shaped canopy that encloses circular or polygonal spaces, deriving from a circular base that curves upward and inward to meet at a central apex.[26] This form often incorporates a drum—a cylindrical or polygonal wall rising from the base—to elevate the dome and provide space for windows, facilitating the transition from the dome's curve to supporting elements below. To adapt domes over non-circular plans, such as squares, transitional elements like pendentives (triangular curved segments) or squinches (arched corner supports) bridge the geometric mismatch, enabling the dome to span larger, more complex interiors. Variations include saucer domes, which are shallow and flattened for lower profiles, and cloister domes, featuring intricate ribbing that radiates from the center like a vaulted ceiling in monastic settings.[26][27] Construction of domes typically proceeds in concentric rings or horizontal courses, with materials layered to distribute weight evenly and counteract outward thrust; stability often demands an oculus—an open circular aperture at the crown—or a lantern, a small turret-like structure that lightens the top and allows internal illumination while aiding ventilation.[28] In ancient Roman examples, unreinforced concrete poured in graduated layers, with lighter aggregates toward the summit, enabled expansive spans without internal supports. Pendentives or squinches not only provide structural continuity but also channel forces downward to piers or walls, preventing collapse under the dome's self-weight.[29] Domes offer advantages in evoking centrality and unity, their unbroken curves creating a sense of enclosure and focus that draws the eye upward, while features like the oculus introduce dramatic natural light, enhancing spatial depth and atmosphere. In religious architecture, domes frequently symbolize the heavens or divine canopy, representing cosmic order and spiritual ascension, as the curved form mimics the vault of the sky and the light from above signifies enlightenment or the presence of the divine.[30] A seminal example is the Pantheon in Rome, completed around 126 CE under Emperor Hadrian, which features the largest unreinforced concrete dome in history at 43.3 meters in diameter, its coffered interior reducing weight while the central oculus floods the space with light, embodying Roman engineering prowess.[28] Another iconic instance is the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (modern Istanbul), constructed in 537 CE by architects Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles, where a massive central dome, 31 meters in diameter, rests on pendentives over a square base, supported by a drum with 40 windows that illuminate the vast interior and underscore its role as a symbol of Byzantine imperial and religious authority.[31]Fan Vault

The fan vault represents a late development in Gothic architecture, particularly prominent in England during the Perpendicular period, where ribs radiate outward from the capitals in concave, fan-like arcs to form an intricate, ornamental ceiling. These vaults feature ribs of uniform curvature and equidistant spacing, creating half-conoid surfaces that converge at the apex, often adorned with blind tracery—solid stone patterns mimicking openwork window designs—and pendants, which are downward-projecting ornamental bosses that add visual depth and draw the eye upward. This geometry evolved as a decorative refinement of earlier vaulting techniques, emphasizing aesthetic complexity over purely functional ribbing.[32][33] Constructing a fan vault demanded advanced masonry skills, including complex temporary centering—wooden frameworks—to support the curved ribs during assembly, as well as precise stone cutting to ensure seamless joints in the radiating voussoirs. The infill between ribs typically formed lierne networks, short connecting ribs that created intricate webbing, while the overall shell remained thin, often 10-15 cm thick, to achieve spans up to 12.7 meters without excessive weight. This tierceron-influenced style, unique to English late Gothic, required masons to balance ornamental elaboration with structural integrity through careful load distribution along the fan patterns.[34][35][33] The design offered significant aesthetic advantages, with the radiating ribs and tracery enhancing the illusion of height and spaciousness in interiors, while structurally providing lightness despite the elaborate ornamentation, as the thin shell efficiently transferred loads to the walls via the conoid geometry. Building on rib vault principles, fan vaults allowed for greater decorative freedom without compromising stability, making them ideal for grand ecclesiastical spaces.[34][36] Prominent examples include the fan vault in King's College Chapel, Cambridge, constructed around 1512–1515, which spans 12.7 meters—the longest of its kind—with delicately thin ribs and pendants that exemplify the form's elegance. Similarly, the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey, completed circa 1512, showcases a multifaceted fan vault with intricate blind tracery and pendants, integrating the structure seamlessly with the chapel's perimeter walls for a unified ornamental effect.[35][33][37]Other Variants

The corbelled vault represents an early, pre-arched form of vaulting achieved by progressively projecting or overhanging courses of stone that step inward to meet at an apex, forming a beehive-like dome without the use of a true keystone or arch principle.[38] This technique was employed in Mycenaean tholos tombs, such as the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae (ca. 1350 BCE), where a circular subterranean chamber up to 14.5 meters in diameter was roofed with carefully layered ashlar blocks, creating a stable but steeply inclined interior space.[38] Unlike later arched vaults, corbelled construction relied on compression from the weight of overlying earth for stability, limiting spans and requiring immense lintel stones, as seen in the 120-ton triangular block over the tomb's entrance.[38] A pitched brick barrel vault modifies the standard barrel form by laying bricks in inclined, graduated courses that create a sloped crown, enhancing structural integrity by reducing the risk of cracking along the vault's length.[39] This variant, influenced by Mesopotamian and Parthian techniques transmitted through Roman military contacts, appears in early examples like Bath A at Argos (1st century CE), where pitched bricks reinforced a wide span over 8 meters.[39] In structures such as the Church of St. John the Theologian at Ephesus (6th century CE), the method blended with radial brickwork to form durable, low-slope coverings suitable for underground or semi-subterranean settings like Roman hypogea, where the pitch facilitated drainage.[40][3] The cloister vault, also known as a domical or pavilion vault, consists of four convex cylindrical surfaces intersecting to form a low, saucer-shaped dome over a square or polygonal base, often without prominent groins.[1] Constructed from wedge-shaped stone or brick units radiating from the center, it was used for covering small, enclosed spaces such as oratories or chapel bays, as in the 2nd-century CE basilica at Camp Mousmieh, Syria, where it capped a cross-shaped naos within a compact square plan.[41] This form provided a transitional covering between barrel vaults and full domes, appearing in early Byzantine churches like S. Maria delle Cinque Torri in S. Germano (778 CE), emphasizing symbolic enclosure in intimate liturgical areas.[41][42] These variants, including corbelled, pitched, and cloister forms, generally exhibited limitations in efficiency compared to true arched vaults, as they demanded more material for support and restricted maximum spans due to reliance on step-like or inclined layering rather than balanced thrust distribution.[38] Such methods persisted in regions with limited advanced centering technology, serving as practical precursors until more refined arch-based systems prevailed.[39]Historical Development

Ancient and Roman Origins

Corbelled vaults appeared as early as the 4th millennium BCE in the ancient Near East, where mud-brick corbelled vaults—formed by stepping bricks inward from each side—were used in tombs and gateways, as evidenced by archaeological finds in Mesopotamia (such as at Uruk) and Egypt.[3] Later examples predate the classical Mediterranean civilizations, with corbelled vaults appearing in Nubia around 2000 BCE. These structures, constructed from mudbrick without formwork, featured stepped or pitched profiles that approximated curved forms through successive overhanging courses, primarily used in tombs and domestic buildings in the region of Upper Egypt and present-day Sudan.[43] This method represented an early adaptation to local materials and environmental needs, allowing enclosed spaces in arid climates without reliance on timber centering. In pre-Roman Italy and Greece, vaulting remained limited due to a strong preference for post-and-lintel construction, which emphasized vertical supports and horizontal beams in monumental architecture. The Etruscans, while introducing true arches and employing barrel vaults in rock-cut tombs such as the Tomb of the Augurs at Tarquinia (c. 530 BCE), restricted their use to subterranean or small-scale contexts, often combining them with corbelling for stability.[44] Similarly, Greek builders favored the post-and-lintel system in temples and stoas, as seen in the Parthenon (447–432 BCE), where stone lintels spanned intercolumniations up to 4 meters, avoiding the thrust management required for vaults and prioritizing aesthetic clarity over expansive interiors.[45] Roman engineers revolutionized vaulting during the Republic and Empire by extensively applying concrete—known as opus caementicium—to construct large-scale barrel and groin vaults, enabling unprecedented spans and complex forms. This innovation, emerging around the 2nd century BCE, integrated volcanic aggregates like tuff with lime and pozzolana (a reactive ash from the Bay of Naples) to create a cohesive, hydraulic mortar that set underwater and resisted tension, far surpassing earlier lime-based mixtures.[46] Barrel vaults, essentially extended semicircular arches, covered aqueduct channels and basilica naves, while groin vaults—formed by intersecting perpendicular barrel vaults—distributed loads more efficiently, as exemplified in the multi-level tabernae of Trajan's Markets (c. 110 CE), where concrete vaults supported commercial spaces over terraced topography. These techniques allowed Roman vaults to achieve spans up to 30 meters in public baths, such as the 27-meter barrel vaults in the frigidarium of Trajan's Baths (c. 109 CE), where lightweight caementa (rubble fill) and thin facing layers minimized weight while maximizing durability.[47] The empire's expansion disseminated these methods across provinces, influencing hypostyle halls in North African basilicas and barrel-vaulted tombs like the Mausoleum of Augustus (28 BCE), which adapted vaulting for imperial commemoration and civic grandeur.[48]Byzantine and Early Christian

In the Early Christian period, vaulting techniques adapted Roman engineering for ecclesiastical purposes, with basilicas featuring barrel vaults over naves and aisles to create expansive, column-supported interiors. For instance, Old St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, constructed around 333 CE under Emperor Constantine, incorporated barrel vaults in its aisles and a vaulted apse to enclose the sacred space around the apostle's tomb, emphasizing longitudinal processional paths toward the altar.[49] These structures often combined timber roofs over the main nave with masonry vaults in subsidiary areas, allowing for clerestory lighting that filtered divine illumination into the worship space.[50] Byzantine architecture elevated vaulting to new heights of structural innovation and symbolic expression, particularly through the integration of domes over square bays using pendentives—curved triangular sections that smoothly transition from orthogonal walls to circular domes. The paradigmatic example is Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, completed in 537 CE under Emperor Justinian I, where a massive central dome spanning approximately 31 meters in diameter rests on pendentives rising from four large piers, creating an illusion of weightless suspension and evoking the heavenly vault.[51] This design not only solved the engineering challenge of dome-on-square but also symbolized the cosmos, with light penetrating through windows at the dome's base representing divine radiance descending upon the congregation.[52] In regions like Armenia, influenced by Byzantine practices, squinches—arched niches corbeling inward from corners—served a similar transitional role, as seen in early medieval churches where they supported domes over square plans, adapting local stone masonry to centralized layouts.[53] Construction techniques in this era relied on brick laid in mortar, often with lightening courses—layers of hollow tiles or reduced brickwork—to minimize weight and thrust while maintaining stability during erection without extensive centering. These methods, refined in the Eastern Roman Empire, allowed for intricate vaulted forms like semi-domes and exedrae flanking the main dome in Hagia Sophia, distributing loads effectively across piers and walls.[54] Symbolically, vaults and domes channeled light as a metaphor for spiritual enlightenment, with golden mosaics on curved surfaces reflecting illumination to mimic the ethereal glow of heaven, transforming interiors into microcosms of the divine order.[55] The influence of these vaulting innovations spread westward through Byzantine territorial and cultural expansion, notably to Ravenna under Justinian's reconquest. The Basilica of San Vitale, dedicated around 547 CE, exemplifies this dissemination with its octagonal vaulted core supporting a dome via pendentives, integrated with barrel-vaulted ambulatories and adorned with mosaics that echo Constantinopolitan aesthetics, underscoring the empire's role in disseminating centralized, light-filled sacred spaces.[56]Romanesque Period

The Romanesque period, spanning the 11th and 12th centuries in Western Europe, marked a revival of vaulting techniques following the decline of Roman architectural expertise after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. This resurgence was influenced by earlier Carolingian experiments, such as the groin vaults employed in the ambulatory of the Palatine Chapel at Aachen, constructed around 792–805 CE under Charlemagne, which demonstrated an early mastery of intersecting barrel vaults to create stable, domed spaces.[57] These precursors laid the groundwork for Romanesque builders to adapt stone vaulting for larger ecclesiastical structures, particularly in monastic and pilgrimage contexts, where robust designs supported growing communal worship needs. Key advancements in Romanesque vaulting included the widespread adoption of thick-walled groin vaults, as seen in Speyer Cathedral, where the nave was reconstructed with square-bayed groin vaults spanning two bays each around 1061 CE, elevating the structure and showcasing innovative load distribution over robust masonry piers.[58] Further experimentation appeared in early rib vaults at Durham Cathedral, begun in 1093 CE, with the nave featuring pointed transverse arches and diagonal ribs by approximately 1096 CE, marking one of the earliest uses of skeletal ribbing to reinforce groin-like cells and manage weight in a long basilica plan.[59] These developments addressed the limitations of simpler barrel vaults by intersecting them to form groin vaults, allowing for wider spans while distributing lateral forces more effectively.[60] Romanesque vaulting relied on cut stone masonry laid in courses, typically using semi-circular round arches to form the vault's profile, which required massive walls—often up to 3 meters thick—to counter the outward thrust generated by the vault's weight in extended naves.[61] This thrust posed significant challenges, as uneven settlement or inadequate buttressing could lead to cracking or collapse, necessitating additional features like transverse diaphragm arches and external flying buttress precursors to stabilize long vaults spanning over 10 meters.[62] Builders mitigated these issues through layered construction, where ribs or groins were integrated during the infilling of vault cells with lighter rubble cores, ensuring structural integrity without excessive material use. Prominent examples of Romanesque vaulting include Cluny Abbey III, constructed from 1088 to 1130 CE, which featured an expansive barrel-vaulted nave reinforced by groin elements in the aisles, creating the largest church in Christendom at the time with a span of nearly 40 meters.[63] In England, Norman Romanesque churches like Durham exemplified the style's vigor, while in Sicily, Norman structures such as Cefalù Cathedral (begun 1131 CE) incorporated groin and cloister vaults in basilican plans, blending local stonework with the period's emphasis on solidity and symbolism.[64]Gothic Period

The Gothic period, spanning the 12th to 16th centuries, marked a transformative era in vault construction, particularly in Northern Europe, where innovations in rib vaults enabled unprecedented structural height and lightness in cathedrals, symbolizing spiritual aspiration.[65] Key advancements included the widespread adoption of pointed arches and flying buttresses, which concentrated loads more efficiently than rounded Romanesque forms, allowing vaults to rise dramatically while supporting expansive interiors.[66] These elements facilitated the transition from sexpartite vaults—divided into six sections per bay for added stability in wider naves—to simpler quadripartite designs, as exemplified in Notre-Dame de Paris (c. 1163–1345), where the nave's early sexpartite rib vaults evolved into quadripartite forms in the choir to enhance uniformity and height.[67][68] In England, the Perpendicular style represented the culmination of these developments with the introduction of fan vaults, characterized by radiating ribs that created intricate, fan-like patterns for both aesthetic and structural purposes.[69] The cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral (c. 1351–1412) provide the earliest surviving example, where slender ribs converge upward, distributing weight evenly and allowing for delicate, lace-like ceilings that emphasized verticality.[70] Techniques such as thin stone webs—lightweight infill panels between ribs—and lierne ribs (short connecting ribs not reaching the central boss) further enhanced stability, reducing material use while enabling larger glazed areas for stained glass, which flooded interiors with colored light to evoke divine presence.[71] This architectural evolution was deeply intertwined with social and symbolic dimensions, as mason guilds, organized collectives of skilled craftsmen, drove innovation through specialized knowledge passed via apprenticeships and trade secrets. The soaring vaults not only demonstrated technical prowess but also embodied theological ideals, with their upward thrust toward heaven representing the soul's ascent and the integration of light through stained glass symbolizing divine illumination.[72]Renaissance and Baroque

The Renaissance marked a revival of classical vault forms, particularly groin vaults and domes, drawing on ancient Roman precedents to emphasize harmony and proportion in architecture. Filippo Brunelleschi's design for the Pazzi Chapel in Florence, constructed around the 1440s, exemplifies this approach with its innovative umbrella vault—a ribbed dome supported on pendentives over a square plan—that integrated mathematical precision inspired by Vitruvius's principles of symmetry and modular ratios.[73][74]/FAB%2003.36.%20Filipovska,%20T.%20-%20Vitruvian%20Echo%20through%20the%20Renaissance.pdf) This structure employed a twelve-ribbed hemispherical dome, achieving a sense of spatial unity through proportional geometry that echoed Vitruvian ideals of firmitas, utilitas, and venustas, thereby revolutionizing 15th-century vaulting by prioritizing aesthetic balance over medieval structural experimentation.[75] In the Baroque period, vaults evolved toward greater elaboration, incorporating illusionistic frescoes and dynamic geometries to create dramatic, immersive experiences that blurred the boundaries between architecture and painting. Antonio da Correggio's frescoes in the dome of Parma Cathedral, executed in the 1520s, introduced foreshortened perspective (di sotto in sù) to depict the Assumption of the Virgin, transforming the octagonal vault into an apparent heavenly expanse with swirling figures that drew viewers upward.[76][77] This technique influenced later Baroque works, such as Gian Lorenzo Bernini's baldacchino (1624–1633) beneath the dome of St. Peter's Basilica, where twisted Solomonic columns and gilded bronze elements enhanced the vault's theatricality, emphasizing movement and light to evoke spiritual ecstasy.[78] Baroque architects advanced vaulting techniques by employing faux-vaulting through perspective painting and lighter stucco applications over structural ribs, allowing for more fluid, undulating forms without compromising stability. In Michelangelo's Pauline Chapel (c. 1540s), the barrel-vaulted ceiling, though primarily noted for its end-wall frescoes like the Crucifixion of St. Peter, incorporated subtle stucco reliefs that complemented the architectural frame, using cooler tones and restrained illusionism to convey introspective depth.[79] Jesuit churches further exemplified these innovations, with undulating vaults in designs inspired by Guarino Guarini's complex geometries, as seen in the ribbed dome of San Lorenzo in Turin (late 17th century), where interlocking arches created wave-like surfaces that heightened spatial drama and symbolic intricacy.[80][81] These methods, relying on stucco's malleability for ornate detailing over robust ribs, enabled expansive interiors that prioritized visual rhetoric and emotional impact.[82]19th-Century Revivals

The 19th-century revivals of vaulting in architecture emerged amid the Industrial Revolution, blending romantic nostalgia for medieval forms with innovative materials like iron to achieve larger spans and aesthetic grandeur. Neo-Gothic styles, championed by architects such as Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin and theorists like John Ruskin, sought to counter the perceived dehumanizing effects of industrialization by reviving pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and intricate stonework as symbols of moral and spiritual integrity.[83][84][85] In parallel, neoclassical revivals adapted ancient dome forms using cast iron for structural efficiency, reflecting a continued admiration for classical symmetry while embracing industrial fabrication techniques. These movements produced hybrid vaults that integrated traditional masonry with metal reinforcements, enabling ambitious public and institutional projects.[83][86] Pugin's influence was pivotal in the neo-Gothic revival, as he advocated for authentic medieval detailing in his designs, including ribbed vaults that echoed Gothic structural principles to foster a sense of ecclesiastical purity. His collaboration with Charles Barry on the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament), constructed from 1836 to 1870, featured extensive rib vaults in the interiors, such as those in the Commons and Lords chambers, where stone ribs converged to support expansive ceilings while evoking the verticality of medieval cathedrals.[84][87] Ruskin complemented this by theorizing Gothic architecture's organic vitality in works like The Stones of Venice (1851–1853), praising its craftsmanship as an antidote to machine-made uniformity and influencing a generation of architects to prioritize hand-hewn details in vault construction.[83] A notable example of fan vault revival appears in the iron-and-glass roof of St. Pancras Station, completed in 1868 by William Henry Barlow, where curved ribs formed a pointed barrel vault spanning 210 feet, blending Gothic ornamentation with industrial lightness to create a dramatic, light-filled enclosure.[88] Neoclassical dome revivals, meanwhile, utilized cast iron to reinterpret Roman precedents on a monumental scale, as seen in the United States Capitol dome in Washington, D.C., designed by Thomas U. Walter and constructed from 1855 to 1866. This 288-foot-tall structure employed 8,909,200 pounds of cast-iron segments assembled into a double-shell dome, painted to mimic stone and reinforced with hidden iron framework to support its neoclassical proportions without excessive masonry weight.[89] Techniques in these revivals often involved hybrid systems, such as wrought-iron ties and trusses to counteract thrust in masonry vaults, allowing spans up to 100 feet in mills and stations, while cast-iron ribs provided both support and decorative flair in larger assemblies.[86][90] The Gothic Revival's anti-industrial ethos positioned vaulting as a critique of mechanization, yet it paradoxically incorporated iron for practicality, as exemplified at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London's Crystal Palace, where Joseph Paxton's vast iron-skeleton vaults—enclosing 990,000 square feet under glass—showcased revivalist eclecticism alongside modern engineering prowess.[83][91] These World's Fairs highlighted vaults' versatility, blending historical forms with industrial innovation to symbolize progress rooted in tradition.[91]Regional Traditions

Indian Architecture