Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

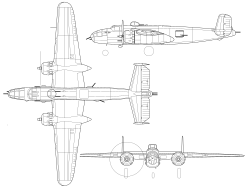

North American B-25 Mitchell

View on Wikipedia

The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Brigadier General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation.[2] Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in every theater of World War II, and after the war ended, many remained in service, operating across four decades. Produced in numerous variants, nearly 10,000 B-25s were built.[1] It was the most-produced American medium bomber and the third-most-produced American bomber overall. These included several limited models such as the F-10 reconnaissance aircraft, the AT-24 crew trainer, and the United States Marine Corps' PBJ-1 patrol bomber.

Key Information

Design and development

[edit]On 11 March 1939, the US Army Air Corps issued Proposal No. 39-640 specifying a medium bomber capable of carrying a 3,000 lb (1,400 kg) bombload over a range of 2,000 miles (3,200 km) at top speed in excess of 300 mph (480 km/h). North American Aviation (NAA) used its NA-40B design to develop the NA-62 proposal. More state of the art compared to the competing Martin No. 179 proposal, the North American team included easy field maintenance and repair features, and according to Avery, "It promised to be an easy airplane to fly and placed no special requirements on pilot training programs." On 20 September. the Air Corps issued North American contract No. W353-ac-13258 for 184 B-25s powered by the Wright R-2600. The plane used the NACA 23017 airfoil at the wing root changing to a NACA 4409-R at the wingtip. On 19 August 1940, Vance Breese and NAA test engineer Roy Ferren flew the first flight test, when Ferren noted a severe roll-yaw condition.[3]

Preliminary flights by the Air Corps noted the Dutch roll characteristic, accentuated by wind and gusts and demanded a fix. NAA's first nine aircraft had a constant-dihedral, the wing having a consistent upward angle from the fuselage to the wingtip. "Flattening", or changing the outer wing panels dihedral to zero degrees, was a simple solution that solved the aerodynamic problem. This gave the B-25 its gull wing configuration. The 25 February 1941 flight test confirmed the change resulted in optimum flight characteristics.[4] The vertical tail also went through five variations before being finalized. By the time of the Attack on Pearl Harbor, 130 B-25s had been delivered.[3]

Special variations were made to accommodate photo reconnaissance, armament, long range ferry, anti-submarine patrol, winterizing, and use in a desert environment. By February 1941, the first 24 B-25s were configured with three .30 cal guns and a single .50 cal tail gun. The B-25A had self-sealing fuel cells. The B-25B had top and bottom turrets with twin .50 cal guns each, though the tail gun was removed. By December 1941, the B-25C had additional self-sealing fuel cells outboard the wing center section. By February 1942, the first B-25D, and then in May 1943, the 75mm cannon-armed B-25G series were accepted by the Air Corps. By August 1943, the B-25H had a lighter 75mm cannon, 4 nose guns instead of 2, two waist guns. two in the tail turret, four blister gun packs, and eliminated the co-pilot after Jimmy Doolittle questioned the need. In December 1943, the B-25J was introduced, the final variant and the most produced, reincorporated the co-pilot position and included a bombardier.[3]

NAA manufactured the greatest number of aircraft in World War II, the first time a company had produced trainers, bombers, and fighters simultaneously (the AT-6/SNJ Texan/Harvard, B-25 Mitchell, and the P-51 Mustang).[5] It produced B-25s at both its Inglewood main plant and an additional 6,608 aircraft at its Kansas City, Kansas, plant at Fairfax Airport.[6][7][8]

After the war, the USAF placed a contract for the TB-25L trainer in 1952. This was a modification program by Hayes of Birmingham, Alabama. Its primary role was reciprocating engine pilot training.[9]

A development of the B-25 was the North American XB-28 Dragon, designed as a high-altitude bomber. Two prototypes were built with the second prototype, the XB-28A, evaluated as a photo-reconnaissance platform, but the aircraft did not enter production.[10]

Flight characteristics

[edit]The B-25 was a safe and forgiving aircraft to fly.[11] With one engine out, 60° banking turns into the dead engine were possible, and control could be easily maintained down to 145 mph (230 km/h). The pilot had to remember to maintain engine-out directional control at low speeds after takeoff with rudder; if this maneuver were attempted with ailerons, the aircraft could snap out of control. The tricycle landing gear made for excellent visibility while taxiing. The only significant complaint about the B-25 was its extremely noisy engines; as a result, many pilots eventually suffered from some degree of hearing loss.[12] A Clayton S stack, introduced to quench the exhaust flame, was introduced in the B-25C series. These stacks protruded through the cowling, and though they weighed less than the replaced collector ring, they reduced aircraft speed by 9 mph due to the required aircraft fairings. According to Avery, "The increase in noise as compared to collector rings ported on the outboard side of the nacelles was a general crew complaint."[3]

Durability

[edit]

The Mitchell was exceptionally sturdy and could withstand tremendous punishment. One B-25C of the 321st Bomb Group was nicknamed "Patches" because its crew chief painted all the aircraft's flak hole patches with bright yellow zinc chromate primer. By the end of the war, this aircraft had completed over 300 missions, had been belly-landed six times, and had over 400 patched holes. The airframe of "Patches" was so distorted from battle damage that straight-and-level flight required 8° of left aileron trim and 6° of right rudder, causing the aircraft to "crab" sideways across the sky.[13]

Operational history

[edit]

Asia-Pacific

[edit]Most B-25s in American service were used in the war against Japan in Asia and the Pacific. The Mitchell fought from the North to the South Pacific and the Far East. These areas included the campaigns in the Aleutian Islands, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, New Britain, China, Burma, and the island hopping campaign in the Central Pacific, as well as in the Doolittle Raid. The aircraft's potential as a ground-attack aircraft emerged during the Pacific war. The jungle environment reduced the usefulness of medium-level bombing, and made low-level attack the best tactic. Using similar mast height level tactics and skip bombing, the B-25 proved itself to be a capable anti-shipping weapon and sank many enemy sea vessels. An ever-increasing number of forward firing guns made the B-25 a formidable strafing aircraft for island warfare. The Paul Gunn and Jack Fox modified strafer models with four .50 caliber guns were the B-25C1/D1, while the factory B-25J was equipped with a factory made eight gun strafer nose.[3]: 89–110

In Burma, bridge busting was a primary target of the Tenth Air Force 341st Bomb Group operating B-25C and D airplanes. A glide and skip technique, called "glip" bombing, was most the effective for the Burma Bridge Busters. The 341st ranged as far as the Formosa Strait, the East China coast and French Indochina.[3]: 115–122

Middle East and Italy

[edit]The first B-25s arrived in Egypt and were carrying out independent operations by October 1942.[14] Operations there against Axis airfields and motorized-vehicle columns supported the ground actions of the Second Battle of El Alamein. Thereafter, the aircraft took part in the rest of the campaign in North Africa, the invasion of Sicily, and the advance up Italy. In the Strait of Messina to the Aegean Sea, the B-25 conducted sea sweeps as part of the coastal air forces. In Italy, the B-25 was used in the ground attack role, concentrating on attacks against road and rail links in Italy, Austria, and the Balkans. The B-25 had a longer range than the Douglas A-20 Havoc and Douglas A-26 Invader, allowing it to reach further into occupied Europe. The five bombardment groups – 20 squadrons – of the Ninth and Twelfth Air Forces that used the B-25 in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations were the only U.S. units to employ the B-25 in Europe.[15]

Europe

[edit]In October 1943, the Ninth Air Force 340th was transferred from the African and Mediterranean theater to England in support of the assault on Germany. In November 1944 the medium bombers eliminated the use of electric locomotives along Brenner Pass.[3]: 128–129 [16]

Use as a gunship

[edit]

In antishipping operations, the USAAF had an urgent need for hard-hitting aircraft, and North American responded with the B-25G. In this series, the transparent nose and bombardier/navigator position was changed for a shorter, hatched nose with two fixed .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns and a manually loaded 75 mm (2.95 in) M4 cannon.[17]

The B-25H series continued the development of the gunship version. NAA Inglewood produced 1000. The H had even more firepower; most replaced the M4 gun with the lighter T13E1,[17] designed specifically for the aircraft, but 20-odd H-1 block aircraft completed by the Republic Aviation modification center at Evansville had the M4 and two-machine-gun nose armament. The 75 mm (2.95 in) gun fired at a muzzle velocity of 2,362 ft/s (720 m/s). Due to its slow rate of fire (about four rounds could be fired in a single strafing run), relative ineffectiveness against ground targets, and the substantial recoil, the 75 mm gun was sometimes removed from both G and H models and replaced with two additional .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns as a field modification.[18]

The H series normally came from the factory mounting four fixed, forward-firing .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns in the nose; four in a pair of under-cockpit conformal flank-mount gun pod packages (two guns per side); two more in the manned dorsal turret, relocated forward to a position just behind the cockpit (which became standard for the J-model); one each in a pair of new waist positions, introduced simultaneously with the forward-relocated dorsal turret; and lastly, a pair of guns in a new tail-gunner's position. Company promotional material bragged that the B-25H could "bring to bear 10 machine guns coming and four going, in addition to the 75 mm cannon, eight rockets, and 3,000 lb (1,360 kg) of bombs."[19]

The H had a modified cockpit with single flight controls operated by the pilot. The co-pilot's station and controls were removed and replaced by a smaller seat used by the navigator/cannoneer, The radio operator crew position was aft of the bomb bay with access to the waist guns.[20] Factory production totals were 405 B-25Gs and 1,000 B-25Hs, with 248 of the latter being used by the Navy as PBJ-1Hs.[17] Elimination of the co-pilot saved weight, and moving the dorsal turret forward partially counterbalanced the waist guns and the manned rear turret.[21]

Return to medium bomber

[edit]

The final, and most numerous, series of the Mitchell, the B-25J, looked less like earlier series apart from the well-glazed bombardier's nose of nearly identical appearance to the earliest B-25 subtypes.[17] Instead, the J followed the overall configuration of the H series from the cockpit aft. It had the forward dorsal turret and other armament and airframe advancements. All J models included four .50 in (12.7 mm) light-barrel Browning AN/M2 guns in a pair of "fuselage packages", conformal gun pods each flanking the lower cockpit, each pod containing two Browning M2s. By 1945, however, combat squadrons removed these. The J series restored the co-pilot's seat and dual flight controls. The factory-made kits available to the Air Depot system to create the strafer-nose B-25J-2. This configuration carried a total of 18 .50 in (12.7 mm) light-barrel AN/M2 Browning M2 machine guns: eight in the nose, four in the flank-mount conformal gun pod packages, two in the dorsal turret, one each in the pair of waist positions, and a pair in the tail – with 14 of the guns either aimed directly forward or aimed to fire directly forward for strafing missions. Some aircraft had eight 5-inch (130 mm) high-velocity aircraft rockets.[17]

Postwar (USAF) use

[edit]In 1947, legislation created an independent United States Air Force (USAF) and by that time, the B-25 inventory numbered only a few hundred. Some B-25s continued in service into the 1950s in training, reconnaissance, and support roles. The principal use during this period was as pilot trainers, radar control trainers, weather reconnaissance, and transports. Others were assigned to units of the Air National Guard in training roles in support of Northrop F-89 Scorpion and Lockheed F-94 Starfire operations.[3]: 141–143

During its USAF tenure, many B-25s received the so-called "Hayes modification" and as a result, surviving B-25s often have exhaust systems with a semicollector ring that splits emissions into two different systems. The upper seven cylinders are collected by a ring, while the other cylinders remain directed to individual ports.

TB-25J-25-NC Mitchell, 44-30854, the last B-25 in the USAF inventory, assigned at March AFB, California, as of March 1960,[22] was flown to Eglin AFB, Florida, from Turner Air Force Base, Georgia, on 21 May 1960, the last flight by a USAF B-25. It was presented by Brigadier General A. J. Russell, Commander of SAC's 822d Air Division at Turner AFB, to the Air Proving Ground Center Commander, Brigadier General Robert H. Warren. He in turn presented the bomber to Valparaiso, Florida, Mayor Randall Roberts on behalf of the Niceville-Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce. Four of the original Tokyo Raiders were present for the ceremony, Colonel (later Major General) David Jones, Colonel Jack Simms, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Manske, and retired Master Sergeant Edwin W. Horton.[23] It was donated back to the Air Force Armament Museum around 1974 and marked as Doolittle's 40-2344.[24]

U.S. Navy and USMC

[edit]

The U.S. Navy designation for the Mitchell B-25 was the PBJ-1, similarly the PBJ-1C and PBJ-1D reflected their AAF counterparts. Night search PBJs incorporated a retractable APS-3 radome scope. Under the pre-1962 USN/USMC/USCG aircraft designation system, PBJ-1 stood for Patrol (P) Bomber (B) built by North American Aviation (J), first variant (-1) under the existing American naval aircraft designation system of the era. In early 1943, the Navy took delivery of an initial 706 B-25s, assigned to the Marine Corps for patrol and anti-submarine duties initially, but then transitioning into an attack aircraft with bombs, torpedoes and radar directed rockets. The PBJ had its origin in an inter-service agreement of mid-1942 between the Navy and the USAAF exchanging the Boeing Renton plant for the Kansas plant for B-29 Superfortress production. The Boeing XPBB Sea Ranger flying boat, competing for B-29 engines, was cancelled in exchange for part of the Kansas City Mitchell production. On 1 March 1943, VMB-413 was the first of sixteen USMC squadrons equipped with PBJs, all commissioned at MCAS Cherry Point. The large quantities of B-25H and J series became known as PBJ-1H and PBJ-1J, respectively.[3]: 65–72

From 1944 onwards, the Marine PBJs flew from the Philippines, Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. Their primary mission was radar directed night strikes against enemy shipping. Weapons included the five-inch HVAR rocket, and the 11.75 inch "Tiny Tim" rocket. Long range night operations meant more fuel, with weight reductions achieved removing the top turret and slide blisters.[25][3]: 67–68

During the war, the Navy tested the cannon-armed G series and conducted carrier trials with an H equipped with arresting gear. After World War II, some PBJs stationed at the Navy's rocket laboratory in Inyokern, California, site of the present-day Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, tested air-to-ground rockets and arrangements. One arrangement was a twin-barrel nose that could fire 10 spin-stabilized five-inch rockets in one salvo.[26]

Royal Air Force

[edit]Great Britain received 910 B-25s during WWII, but many were returned afterwards.[3]: 192

The Royal Air Force (RAF) was an early customer for the B-25 via Lend-Lease. The first Mitchells were given the service name Mitchell I by the RAF and were delivered in August 1941, to No. 111 Operational Training Unit based in the Bahamas. These bombers were used exclusively for training and familiarization and never became operational. The B-25Cs and Ds were designated Mitchell II. Altogether, 167 B-25Cs and 371 B-25Ds were delivered to the RAF. The RAF tested the cannon-armed G series but did not adopt the series nor the follow-on H series.

By the end of 1942, the RAF had taken delivery of 93 Mitchells, marks I and II. Some served with squadrons of No. 2 Group RAF, the RAF's tactical medium-bomber force, including No. 139 Wing RAF at RAF Dunsfold. The first RAF operation with the Mitchell II took place on 22 January 1943, when six aircraft from No. 180 Squadron RAF attacked oil installations at Ghent. After the invasion of Europe (by which point 2 Group was part of Second Tactical Air Force), all four Mitchell squadrons moved to bases in France and Belgium (Melsbroek) to support Allied ground forces. The British Mitchell squadrons were joined by No. 342 (Lorraine) Squadron of the French Air Force in April 1945.

As part of its move from Bomber Command, No 305 (Polish) Squadron flew Mitchell IIs from September to December 1943 before converting to the de Havilland Mosquito. In addition to No. 2 Group, the B-25 was used by various second-line RAF units in the UK and abroad. In the Far East, No. 3 PRU, which consisted of Nos. 681 and 684 Squadrons, flew the Mitchell (primarily Mk IIs) on photographic reconnaissance sorties.

Royal Canadian Air Force

[edit]The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) used the B-25 Mitchell for training during the war. Postwar use continued operations with most of the 162 Mitchells received. The first B-25s had been diverted to Canada from RAF orders. These included one Mitchell I, 42 Mitchell IIs, and 19 Mitchell IIIs. No 13 (P) Squadron was formed unofficially at RCAF Rockcliffe in May 1944 and used Mitchell IIs on high-altitude aerial photography sorties. No. 5 Operational Training Unit at Boundary Bay, British Columbia and Abbotsford, British Columbia, operated the B-25D Mitchell in the training role together with B-24 Liberators for Heavy Conversion as part of the BCATP. The RCAF retained the Mitchell until October 1963.[27]

No 418 (Auxiliary) Squadron received its first Mitchell IIs in January 1947. It was followed by No 406 (auxiliary), which flew Mitchell IIs and IIIs from April 1947 to June 1958. No 418 operated a mix of IIs and IIIs until March 1958. No 12 Squadron of Air Transport Command also flew Mitchell IIIs along with other types from September 1956 to November 1960. In 1951, the RCAF received an additional 75 B-25Js from USAF stocks to make up for attrition and to equip various second-line units.[28]

Royal Australian Air Force

[edit]The Australians received Mitchells by the spring of 1944. The joint Australian-Dutch No. 18 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron RAAF had more than enough Mitchells for one squadron, so the surplus went to re-equip the RAAF's No. 2 Squadron, replacing their Beauforts.

Dutch Air Force

[edit]

During World War II, the Mitchell served in fairly large numbers with the Air Force of the Dutch government-in-exile. They participated in combat in the East Indies, as well as on the European front. On 30 June 1941, the Netherlands Purchasing Commission, acting on behalf of the Dutch government-in-exile in London, signed a contract with North American Aviation for 162 B-25C aircraft. The bombers were to be delivered to the Netherlands East Indies to help deter any Japanese threatened expansion into the region.[3]: 81–87

In February 1942, the British Overseas Airways Corporation agreed to ferry 20 Dutch B-25s from Florida to Australia travelling via Africa and India, and an additional 10 via the South Pacific route from California. During March, five of the bombers on the Dutch order had reached Bangalore, India, and 12 had reached Archerfield in Australia. The B-25s in Australia were used as the nucleus of a new squadron, No. 18 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron RAAF.[3]: 81–87

In June 1940, No. 320 (Netherlands) Squadron RAF had been formed from personnel formerly serving with the Royal Dutch Naval Air Service, who had escaped to England after the German occupation of the Netherlands. Equipped with various British aircraft, No. 320 Squadron flew antisubmarine patrols, convoy escort missions, and performed air-sea rescue duties. In March 1943, they acquired the B-25 Mark II nd III Mitchells. In October 1944, they deployed to Belgium, but then disbanded in August 1945.[3]: 86

Soviet Air Force

[edit]The USSR received 862 B-25s (B, C, D, G, and J types) from the United States under Lend-Lease during World War II[29] via the Alaska–Siberia ALSIB ferry route. A total of 870 B-25s were sent to the Soviets,[30] meaning that 8 aircraft were lost during transportation.

Other damaged B-25s arrived or crashed in the Far East of Russia, and one Doolittle Raid aircraft landed there short of fuel after attacking Japan. This lone airworthy Doolittle Raid aircraft to reach the Soviet Union was lost in a hangar fire in the early 1950s while undergoing routine maintenance. In general, the B-25 was operated as a ground-support and tactical day bomber (as similar Douglas A-20 Havocs were used). It saw action in fights from Stalingrad (with B/C/D models) to the German surrender during May 1945 (with G/J types).

The B-25s that remained in Soviet Air Force service after the war were assigned the NATO reporting name "Bank".

China

[edit]Well over 100 B-25Cs and Ds were supplied to the Nationalist Chinese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. An unknown number were abandoned with the retreat to Formosa.[3]: 192

Brazilian Air Force

[edit]

During the war and after WWII, Brazil received 80 B-25s, with the first delivery prior to December 1941.[3]: 191

Free French

[edit]The Royal Air Force issued at least 21 Mitchell IIIs to No 342 Squadron, which was made up primarily of Free French aircrews. Following the liberation of France, this squadron transferred to the newly formed French Air Force (Armée de l'Air) as GB I/20 Lorraine. The aircraft continued in operation after the war, with some being converted into fast VIP transports. They were struck off charge in June 1947.

Biafra

[edit]In October 1967, during the Nigerian Civil War, Biafra bought two Mitchells. After a few bombings in November, they were put out of action in December.[31]

Indonesia

[edit]

Indonesian Air Force received 25 ex-Dutch B-25 Mitchells after the end of Indonesian National Revolution in 1950,[32] consisting of 5 B-25C photo-reconnaissance, 1 B-25C transport, 10 B-25J bombers and 9 B-25J gunship/strafer variants.[33] A pair of B-25J were used to attack a radio station in Ambon during South Maluku rebellion in August 1950.[34] They were used to bomb rebel targets during the PRRI and Permesta rebellions in 1958, where one was hit by anti-aircraft fire and three were damaged by strafing run from rebel-flown B-26 Invader.[35]

To extend its service life, the B-25s were sent to Hong Kong for major overhaul in 1959–1960.[33] Indonesian B-25s once again saw combat during the Operation Trikora against the Dutch in 1962, where one was used for strafing runs against a Dutch warship, while two others were used in Maluku.[36] The last Indonesian B-25s were retired in 1974.[37]

Variants

[edit]

- B-25

- The initial production version of B-25s, they were powered by 1,350 hp (1,007 kW) R-2600-9 engines. and carried up to 3,600 lb (1,600 kg) of bombs and defensive armament of three .30 machine guns in nose, waist, and ventral positions, with one .50 machine gun in the tail. The first nine aircraft were built with constant dihedral angle. Due to low stability, the wing was redesigned so that the dihedral was eliminated on the outboard section (number made: 24).[38][39]

- B-25A

- This version of the B-25 was modified to make it combat ready; additions included self-sealing fuel tanks, crew armor, and an improved tail-gunner station. No changes were made in the armament. It was redesignated obsolete (RB-25A) in 1942 (number made: 40).[40]

- B-25B

- The tail and gun position were removed and replaced by a manned dorsal turret on the rear fuselage and retractable, remotely operated ventral turret, each with a pair of .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns. A total of 120 were built (this version was used in the Doolittle Raid). A total of 23 were supplied to the Royal Air Force as the Mitchell Mk I.[41][42]

- B-25C

- An improved version of the B-25B, its powerplants were upgraded from Wright R-2600-9 radials to R-2600-13s; de-icing and anti-icing equipment were added; the navigator received a sighting blister; and nose armament was increased to two .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns, one fixed and one flexible. The B-25C model was the first mass-produced B-25 version; it was also used in the United Kingdom (as the Mitchell Mk II), in Canada, China, the Netherlands, and the Soviet Union (number made: 1,625).

- ZB-25C

- B-25D

- Through block 20, the series was near identical to the B-25C. The series designation differed in that the B-25D was made in Kansas City, Kansas, whereas the B-25C was made in Inglewood, California. Later blocks with interim armament upgrades, the D2s, first flew on 3 January 1942 (number made: 2,290).

- F-10

- The F-10 designation distinguished 45 B-25Ds modified for photographic reconnaissance. All armament, armor, and bombing equipment were stripped. Three K.17 cameras were installed, one pointing down and two more mounted at oblique angles within blisters on each side of the nose. Optionally, a second downward-pointing camera could also be installed in the aft fuselage. Although designed for combat operations, these aircraft were mainly used for ground mapping.

- B-25D weather reconnaissance variant

- In 1944, four B-25Ds were converted for weather reconnaissance. One later user was the 53d Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, originally called the Army Hurricane Reconnaissance Unit, now called the "Hurricane Hunters". Weather reconnaissance first started in 1943 with the 1st Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, with flights on the North Atlantic ferry routes.[43][44]

- ZB-25D

- XB-25E

- A single B-25C was modified to test de-icing and anti-icing equipment that circulated exhaust from the engines in chambers in the leading and trailing edges and empennage. The aircraft was tested for almost two years, beginning in 1942; while the system proved extremely effective, no production models were built that used it before the end of World War II. Many surviving warbird-flown B-25 aircraft today use the de-icing system from the XB-25E (number made: 1, converted).

- ZXB-25E

- XB-25F-A

- A modified B-25C, it used insulated electrical coils mounted inside the wing and empennage leading edges to test the effectiveness as a de-icing system. The hot air de-icing system tested on the XB-25E was determined to be the more practical of the two (number made: 1, converted).

- XB-25G

- This modified B-25C had the transparent nose replaced to create a short-nosed gunship carrying two fixed .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns and a 75 mm (2.95 in) M4 cannon, then the largest weapon ever carried on an American bomber (number made: 1, converted).

- B-25G

- The B-25G followed the success of the prototype XB-25G and production was a continuation of the NA96. The production model featured increased armor and a greater fuel supply than the XB-25G. One B-25G was passed to the British, who gave it the name Mitchell II that had been used for the B-25C. The USSR also tested the G (number made: 463; five converted Cs, 58 modified Cs, 400 production).

- B-25H

- An improved version of the B-25G, this version relocated the manned dorsal turret to a more forward location on the fuselage just aft of the flight deck. It also featured two additional fixed .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns in the nose and in the H-5 onward, four in fuselage-mounted pods. The T13E1 light weight cannon replaced the heavy M4 cannon 75 mm (2.95 in). Single controls were installed from the factory with navigator in the right seat (number made: 1000; two airworthy as of 2015[update]).

- B-25J-NC

- Follow-on production at Kansas City, the B-25J could be called a cross between the B-25D and the B-25H. It had a transparent nose, but many of the delivered aircraft were modified to have a strafer nose (J2). Most of its 14–18 machine guns were forward-facing for strafing missions, including the two guns of the forward-located dorsal turret. The RAF received 316 aircraft, which were known as the Mitchell III. The J series was the last factory series production of the B-25 (number made: 4,318).

- CB-25J

- Utility transport version

- VB-25J

- A number of B-25s were converted for use as staff and VIP transports. Henry H. Arnold and Dwight D. Eisenhower both used converted B-25Js as their personal transports. The last VB-25J in active service was retired in May 1960 at the Eglin Air Force Base in Florida.[45]

Trainer variants

[edit]Most models of the B-25 were used at some point as training aircraft.

- TB-25D

- Originally designated AT-24A (Advanced Trainer, Model 24, Version A), trainer modification of B-25D often with the dorsal turret omitted, in total, 60 AT-24s were built.

- TB-25G

- Originally designated AT-24B, trainer modification of B-25G

- TB-25C

- Originally designated AT-24C, trainer modification of B-25C

- TB-25J

- Originally designated AT-24D, trainer modification of B-25J, another 600 B-25Js were modified after the war.

- TB-25K

- Hughes E1 fire-control radar trainer (Hughes) (number made: 117)

- TB-25L

- Hayes pilot-trainer conversion (number made: 90)

- TB-25M

- Hughes E5 fire-control radar trainer (number made: 40)

- TB-25N

- Hayes navigator-trainer conversion (number made: 47)

U.S. Navy / U.S. Marine Corps variants

[edit]

- PBJ-1C

- Similar to the B-25C for the U.S. Navy, it was often fitted with airborne search radar and used in the antisubmarine role.

- PBJ-1D

- Similar to the B-25D for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, it differed in having a single .50 in (12.7 mm) machine gun in the tail turret and waist gun positions similar to the B-25H. Often it was fitted with airborne search radar and used in the antisubmarine role.

- PBJ-1G

- U.S. Navy/U.S. Marine Corps designation for the B-25G, trials only

- PBJ-1H

- U.S. Navy/U.S. Marine Corps designation for the B-25H

- One PBJ-1H was modified with carrier takeoff and landing equipment and successfully tested on the USS Shangri-La, but the Navy did not continue development.[3]: 69–70

- PBJ-1J

- U.S. Navy designation for the B-25J (Blocks −1 through −35), it had improvements in radio and other equipment. Beside the standard armament package, the Marines often fitted it with 5-inch underwing rockets and search radar for the antishipping/antisubmarine role. The 11.75 inch Tiny Tim rocket-powered warhead was used in 1945 on PBJ-1H.[3]: 67–68

Operators

[edit]- An ex-USAAF TB-25N (s/n 44-31173) was acquired in June 1961 and registered locally as LV-GXH, it was privately operated as a smuggling aircraft. It was confiscated by provincial authorities in 1971 and handed over to Empresa Provincial de Aviacion Civil de San Juan, which operated it until its retirement due to a double engine failure in 1976. Currently, it is under restoration to airworthiness.[46]

- Royal Australian Air Force – 50 aircraft, including three joint units with Military Aviation – Royal Dutch East Indies Army (ML-KNIL):

- Biafran Air Force operated two aircraft.[48]

- Bolivian Air Force operated 13 aircraft

- Brazilian Air Force operated 75 aircraft, including B-25B, B-25C, and B-25J.

- Royal Canadian Air Force operated 164 aircraft in bomber, light transport, trainer, and special mission roles.

- No. 13 (P) Squadron Mitchell II at RCAF Station Rockcliffe

- No. 406 Auxiliary Squadron Mitchell III

- Republic of China Air Force operated more than 180 aircraft.

- People's Liberation Army Air Force operated captured Nationalist Chinese aircraft.

- Chilean Air Force operated 12 aircraft.

- Colombian Air Force operated three aircraft.

- Cuban Army Air Force operated six aircraft.

- Fuerza Aérea del Ejército de Cuba

- Cuerpo de Aviación del Ejército de Cuba

- Dominican Air Force operated five aircraft.

- French Air Force operated 11 aircraft.

- Free French Air Force operated 18 aircraft.

- Indonesian Air Force in 1950, received 25 B-25C and B-25J Mitchells previously operated by the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army Air Force (ML-KNIL).[33] The last of these served until 1974.[37]

- Mexican Air Force received three B-25Js in December 1945, which remained in use until at least 1950.[49]

- Eight Mexican civil registrations were allocated to B-25s, including one aircraft registered to the Bank of Mexico, but used by the President of Mexico.[50]

- Military Aviation – Royal Dutch East Indies Army (ML-KNIL; 1942–1950): 149 aircraft (initially in three joint units with the Royal Australian Air Force) during World War II and the Indonesian War of Independence:

- No. 18 Squadron (NEI) RAAF/18 Squadron ML-KNIL (1942–1950) – bomber

- No. 119 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadron RAAF (1943–1943) – bomber

- No. 19 Squadron (NEI) RAAF/19 Squadron ML-KNIL (1944–1948) – transport

- 16 Squadron ML-KNIL (1946–1948) – ground attack

- 20 Squadron ML-KNIL (1946–1950) – transport

- Naval Aviation Service (MLD) – 107 aircraft; initially in a joint unit with the UK Royal Air Force:

- No. 320 (Netherlands) Squadron RAF (1942–1946)

- Peruvian Air Force received eight B-25Js in 1947, which formed Bomber Squadron N° 21 at Talara.

- Spanish Air Force operated one ex-USAAF example interned in 1944 and operated between 1948 and 1956.[51]

- Soviet Air Force (Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily. VVS) received a total of 866 B-25s of the C, D, G*, and J series.[52] * trials only (5).

- Royal Air Force received just over 700 aircraft.[b][53]

- No. 98 Squadron RAF – September 1942 – November 1945 (converted to the Mosquito[53]

- No. 180 Squadron RAF – September 1942 – September 1945 (converted to the Mosquito)[53]

- No. 226 Squadron RAF – May 1943 – September 1945 (disbanded)[53]

- No. 305 Polish Bomber Squadron – September 1943 – December 1943 (converted to the Mosquito)[53]

- No. 320 (Netherlands) Squadron RAF – March 1943 – August 1945 (transferred to Netherlands)[53]

- No. 342 (GB I/20 'Lorraine') Squadron RAF – March 1945 – December 1945 (transferred to France)[53]

- No. 681 Squadron RAF – January 1943 – December 1943 (Mitchell withdrawn)[53]

- No. 684 Squadron RAF – September 1943 – April 1944 (Replaced by Mosquito)[53]

- No. 111 Operational Training Unit RAF, Nassau Airport, Bahamas, August 1942 – August 1945 (disbanded)[53]

- Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm

- operated 1 aircraft for evaluation [citation needed]

- United States Navy received 706 aircraft, most of which were then transferred to the USMC.[54]

- United States Marine Corps

- Uruguayan Air Force operated 15 aircraft.

- Venezuelan Air Force operated 24 aircraft.

Accidents and incidents

[edit]Training mission incident

[edit]On 1 November 1941, a B-25 on a training mission flying out of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, crashed near Benton Ridge, Ohio.[55]

Empire State Building crash

[edit]At 9:40 on 28 July 1945, a USAAF B-25D crashed in thick fog into the north side of the Empire State Building between the 79th and 80th floors. Fourteen people died — 11 in the then world’s tallest building and the three occupants of the aircraft, including the pilot, Colonel William F. Smith.[56] Betty Lou Oliver, an elevator attendant, survived the impact and the subsequent fall of the elevator cage 75 stories to the basement.[57]

General Leclerc's aviation accident

[edit]French general Philippe Leclerc was aboard his North American B-25 Mitchell, Tailly II, when it crashed near Colomb-Béchar in French Algeria on 28 November 1947, killing everyone on board.[58]

Lake Erie skydiving disaster

[edit]A bit after 16:00 on 27 August 1967, a converted civilian B-25 mistakenly dropped eighteen skydivers over Lake Erie, four or five nautical miles (7.5–9.3 km) from Huron, Ohio. The air traffic controller had confused the B-25 with a Cessna 180 Skywagon that was trailing it to take photographs, causing the B-25 pilot to think he was over the intended drop site at Ortner Airport. Sixteen of the jumpers drowned, while two were rescued.[59] A National Transportation Safety Board report faulted the pilot, and to a lesser extent the skydivers, for executing a jump when they could not see the ground, and faulted the controller for the misidentification.[60][61] The United States was subsequently held liable for the controller's negligence.[62]

Surviving aircraft

[edit]

Many B-25s are currently kept in airworthy condition by air museums and collectors.

Specifications (B-25H)

[edit]

Data from United States Military Aircraft since 1909[63]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5 (one pilot, navigator/bombardier, turret gunner/engineer, radio operator/waist gunner, tail gunner)

- Length: 52 ft 11 in (16.13 m)

- Wingspan: 67 ft 7 in (20.60 m)

- Height: 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m)

- Wing area: 618 sq ft (57.4 m2)

- Airfoil: root: NACA 23017; tip: NACA 4409R[64]

- Empty weight: 19,480 lb (8,836 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 35,000 lb (15,876 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Wright R-2600-92 Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder two-row air-cooled radial piston engines, 1,700 hp (1,300 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 272 mph (438 km/h, 236 kn) at 13,000 ft (4,000 m)

- Cruise speed: 230 mph (370 km/h, 200 kn)

- Range: 1,350 mi (2,170 km, 1,170 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 24,200 ft (7,400 m)

Armament

- Guns: 12–18 × .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns and 75 mm (2.95 in) T13E1 cannon

- Hardpoints: 2,000 lb (900 kg) ventral shackles to hold one external Mark 13 torpedo[65]

- Rockets: racks for eight 5 in (127 mm) high velocity aircraft rockets (HVAR)

- Bombs: 3,000 lb (1,360 kg) bombs

Notable appearances in media

[edit]See also

[edit]Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle

- de Havilland Mosquito

- Douglas A-26 Invader

- Junkers Ju 188

- Martin B-26 Marauder

- Mitsubishi Ki-67 Hiryū

- Nakajima Ki-49 Donryu

- Vickers Wellington

Related lists

Notes

[edit]- ^ This number does not include aircraft built after World War II.

- ^ The maximum on RAF strength was 517 in December 1944[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "North American B-25B Mitchell." U.S. Air Force. Retrieved: 8 July 2017.

- ^ United Press, "Bomber Named For Mitchell", The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Friday 23 January 1942, Volume 48, page 21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Avery, N.L. (1992). B-25 Mitchell: The Magnificent Medium. St. Paul: Phalanx Publishing Vo., Ltd. pp. 22–52. ISBN 9780962586057.

- ^ Chorlton Aeroplane May 2013, p. 74.

- ^ "T-6/SNJ/HVD Information (Ray) – NATA". flynata.org. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Parker 2013, pp. 77–79, 83, 88, 92.

- ^ Borth 1945, pp. 70, 92, 244.

- ^ Herman 2012, pp. 11, 88, 115, 140–143, 263, 297.

- ^ Johnson, E. R. (2015). American Military Training Aircraft: Fixed and Rotary-Wing Trainers Since 1916. McFarland. p. 162. ISBN 9780786470945.

- ^ Norton 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Tallman 1973, pp. 216, 228.

- ^ Higham 1975, 8; Higham 1978, 59.

- ^ "A Brief history of the B-25." Archived 3 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine USAF.com. Accessed: 25 May 2015.

- ^ Pace, 2002 p23

- ^ Pace 2002, p. 6.

- ^ "340th Bomb Group History". 57thbombwing.com.

- ^ a b c d e Merriam, Ray, ed. "U. S. Warplanes of World War II." World War II Journal, No. 15, 1 July 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Kinzey 1999, pp. 51, 53.

- ^ Yenne 1989, p. 40.

- ^ Kinzey 1999, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Baugher, Joe. North American B-25H Mitchell." Archived 25 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine American Military Aircraft: US Bomber Aircraft, 11 March 2000. Retrieved: 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Doolittle Park Will Have AF B-25 Bomber". Playground News (Fort Walton Beach, Florida), Volume 15, Number 7, 10 March 1960, p. 10.

- ^ "B-25 Makes Last Flight During Ceremony at Eglin". Playground News (Fort Walton Beach, Florida), Volume 15, Number "17" (actually No. 18: Special), 26 May 1960, p. 2.

- ^ "B-25 44-330854." warbirdregistry.org. Retrieved: 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Closing In: Marines in the Seizure of Iwo Jima (Assault Preparations)". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "Smash Hits." Popular Mechanics, March 1947, p. 113.

- ^ Skaarup 2009, pp. 333–334.

- ^ Walker, R.W.R. "RCAF 5200 to 5249, Detailed List." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Canadian Military Aircraft Serial Numbers, 25 May 2013. Retrieved: 25 May 2015.

- ^ Hardesty, Von (1982). Red Phoenix: The Rise of Soviet Air Power 1941–1945. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 253. ISBN 0874745101.

- ^ Glantz, David (2005). Companion to Colossus Reborn: Key Documents and Statistics. United States of America: University Press of Kansas. p. 148. ISBN 0700613595.

- ^ Jowett, Philip (2016). Modern African Wars (5): The Nigerian-Biafran War 1967–70. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1472816092.

- ^ Heyman, Jos (November 2005). "Indonesian aviation 1945-1950" (PDF). nei.adf-serials.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ a b c "Duet B-25 Mitchell dan B-26 Invader" [B-25 Mitchell and B-26 Invader Duet]. Angkasa Edisi Koleksi. Pesawat Kombatan TNI-AU 1946-2011: Dari Legenda Churen Hingga Kedigdayaan Flanker (in Indonesian). No. 72. PT Mediarona Dirgantara. 2011. p. 20-23.

- ^ Beny Adrian (2011). "Bungkam Radio RMS" [Silencing RMS Radio]. Angkasa Edisi Koleksi. Pesawat Kombatan TNI-AU 1946-2011: Dari Legenda Churen Hingga Kedigdayaan Flanker (in Indonesian). No. 72. PT Mediarona Dirgantara. p. 22-23.

- ^ Cooper, Tom; Koelich, Mark (1 September 2003). "Clandestine US Operations: Indonesia 1958, Operation "Haik"". ACIG.info. Archived from the original on 15 August 2004. Retrieved 28 July 2025.

- ^ Poetra (19 July 2023). "Pembom B-25 Mitchell AURI pernah menembak kapal perang Belanda". Airspace Review. Retrieved 28 December 2024.

- ^ a b Tim Subdisjarah Dispenau (2019). Alat Utama Sistem Senjata TNI AU Periode Tahun 1951-1960 [Main Weapons Systems of the Indonesian Air Force 1951-1960 Period] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Sub-Direktorat Sejarah Dinas Penerangan TNI Angkatan Udara. p. 50.

- ^ Dorr Wings of Fame Volume 3, p. 124.

- ^ "Factsheets: North American B-25." National Museum of the United States Air Force, 26 June 2009. Retrieved: 16 July 2017.

- ^ "Factsheets: North American B-25A". National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, 26 June 2009. Retrieved: 16 July 2017.

- ^ Dorr Wings of Fame Volume 3, pp. 125–126.

- ^ "Factsheets: North American B-25B." National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, 26 June 2009. Retrieved: 16 July 2017.

- ^ Robison, Tom. "B-29 in Weather Reconnaissance." Aerial Weather Reconnaissance Association: Hurricane Hunters. Retrieved: 2 October 2010.

- ^ Gibbins, Scott and Jeffrey Long. "The History of the Hurricane Hunters." Archived 12 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine Hurricane Hunters Association. Retrieved: 2 October 2010.

- ^ Drucker, Graham."North American B-25 Mitchell." fleetairarmarchive.net. Retrieved: 31 March 2013.

- ^ "B-25J-30-NC SN 44-31173 "Huaira Bajo"". The B-25 History Project. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

- ^ Chorlton, Aeroplane May 2013, p. 85.

- ^ Chorlton. Aeroplane May 2013, p. 86.

- ^ Hagedorn, Air Enthusiast May/June 2003, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Hagedorn, Air Enthusiast May/June 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Leeuw, Ruud. "Cuatro Vientos – Madrid." ruudleeuw.com. Retrieved: 25 August 2010.

- ^ Hardesty 1991, p. 253.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Mitchells: The North American Mitchell in Royal Air Force service." Aeromilitaria (Air-Britain Historians), Issue 2, 1978, pp. 41–48.

- ^ Swanborough 1976, p. 457

- ^ "History saved in Benton Ridge memorial". The Toledo Blade. 6 November 2024. Retrieved 7 December 2024.

- ^ Roberts, William."ESB News." Elevator World, March 1996.

- ^ Kingwell 2007, p. 12.

- ^ Fonton, Mickaël (5 August 2010). "Les morts mystérieuses : 4. Leclerc, l'énigme du 13e passager". Valeurs actuelles (in French). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ Jackson, Tom (14 August 2017). "Disaster 50 years ago killed 16 sport parachutists". Sandusky Register. Ogden Newspapers. Retrieved 2 July 2023.

- ^ Clark, Evert (26 September 1967). "Pilot, Controller and Jumpers Found at Fault in Deaths of 16 Sky Divers". The New York Times. p. 36. ProQuest 117481014.

- ^ Fatal Parachuting Accident Near Huron, Ohio, August 27, 1967: Special Investigation Report (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. 1967.

- ^ McCarthy, James J. (1978). "Aerobatics, Sport Aviation and Student Instruction". Journal of Air Law and Commerce. 44 (2): 315. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Swanborough and Bowers 1963, p. 359.

- ^ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- ^ Caiden 1957, p. 176.

Bibliography

[edit]- Borth, Christy. Masters of Mass Production. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1945.

- Bridgman, Leonard, ed. "The North American Mitchell." Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London: Studio, 1946. ISBN 1-85170-493-0.

- Caidin, Martin. Air Force. New York: Arno Press, 1957.

- Chorlton, Martyn. "Database: North American B-25 Mitchell". Aeroplane, Vol. 41, No. 5, May 2013. pp. 69–86.

- Dorr, Robert F. "North American B-25 Variant Briefing". Wings of Fame, Volume 3, 1996. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-874023-70-0. ISSN 1361-2034. pp. 118–141.

- Green, William. Famous Bombers of the Second World War. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1975. ISBN 0-385-12467-8.

- Hagedorn, Dan. "Latin Mitchells: North American B-25s in South America, Part One". Air Enthusiast No. 105, May/June 2003. pp. 52–55. ISSN 0143-5450

- Hagedorn, Dan. "Latin Mitchells: North American B-25s in South America, Part Three". Air Enthusiast Mo. 107, September/October 2003. pp. 36–41. ISSN 0143-5450

- Hardesty, Von. Red Phoenix: The Rise of Soviet Air Power 1941–1945. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1991, first edition 1982. ISBN 0-87474-510-1.

- Heller, Joseph. Catch 22. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961. ISBN 0-684-83339-5.

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, New York: Random House, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4.

- Higham, Roy and Carol Williams, eds. Flying Combat Aircraft of USAAF-USAF (Vol. 1). Andrews AFB, Maryland: Air Force Historical Foundation, 1975. ISBN 0-8138-0325-X.

- Higham, Roy and Carol Williams, eds. Flying Combat Aircraft of USAAF-USAF (Vol. 2). Andrews AFB, Maryland: Air Force Historical Foundation, 1978. ISBN 0-8138-0375-6.

- Johnsen, Frederick A. North American B-25 Mitchell. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 1997. ISBN 0-933424-77-9.

- Kingwell, Mark. Nearest Thing to Heaven: The Empire State Building and American Dreams. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-12612-9.

- Kinzey, Bert. B-25 Mitchell in Detail. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1999. ISBN 1-888974-13-3.

- Kit, Mister and Jean-Pierre De Cock. North American B-25 Mitchell (in French). Paris, France: Éditions Atlas, 1980.

- Lawrence, Joseph (1945). The Observer's Book Of Airplanes. London and New York: Frederick Warne & Co.

- McDowell, Ernest R. B-25 Mitchell in Action (Aircraft number 34). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1978. ISBN 0-89747-033-8.

- McDowell, Ernest R. North American B-25A/J Mitchell (Aircam No.22). Canterbury, Kent, UK: Osprey Publications Ltd., 1971. ISBN 0-85045-027-6.

- Mizrahi, J.V. North American B-25: The Full Story of World War II's Classic Medium. Hollywood, California: Challenge Publications Inc., 1965.

- Norton, Bill. American Bomber Aircraft Development in World War 2. Hersham, Surrey, UK: Midland Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-1-85780-330-3.

- Pace, Steve. B-25 Mitchell Units in the MTO. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84176-284-5.

- Pace, Steve. Warbird History: B-25 Mitchell. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1994. ISBN 0-87938-939-7.

- Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II. Cypress, California: Dana Parker Enterprises, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906-0-4.

- "Pentagon Over the Islands: The Thirty-Year History of Indonesian Military Aviation". Air Enthusiast Quarterly (2): 154–162. n.d. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Powell, Albrecht. "Mystery in the Mon". Archived 31 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine 1994

- Reinhard, Martin A. (January–February 2004). "Talkback". Air Enthusiast. No. 109. p. 74. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Scutts, Jerry. B-25 Mitchell at War. London: Ian Allan, 1983. ISBN 0-7110-1219-9.

- Scutts, Jerry. "Medium with the mostest-The B-25 Mitchell (Part 1)". Air International, February 1993, Vol. 44, No. 2. pp. 83–91. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Scutts, Jerry. "Medium with the mostest - the B-25 Mitchell (Part 2)". Air International, March 1993, Vol. 44, No. 3. pp 144–151. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Scutts, Jerry. North American B-25 Mitchell. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press, 2001. ISBN 1-86126-394-5.

- Skaarup, Harold A. Canadian Warplanes. Bloomington, Indiana: IUniverse, 2009. ISBN 978-1-4401-6758-4.

- Swanborough, F.G. and Peter M. Bowers. United States Military Aircraft since 1909. London: Putnam, 1963.

- Swanborough, Gordon (1976). United States Navy aircraft since 1911. London : Putnam. ISBN 978-0-370-10054-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - Swanborough, Gordon. North American, An Aircraft Album No. 6. New York: Arco Publishing Company Inc., 1973. ISBN 0-668-03318-5.

- Tallman, Frank. Flying the Old Planes. New York: Doubleday and Company, 1973. ISBN 978-0-385-09157-2.

- Vernon, Jerry (Winter 1993). "Talkback". Air Enthusiast. No. 52. pp. 78–79. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Wolf, William. North American B-25 Mitchell, The Ultimate Look: from Drawing Board to Flying Arsenal. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7643-2930-2.

- Yenne, Bill. Rockwell: The Heritage of North American. New York: Crescent Books, 1989. ISBN 0-517-67252-9.

External links

[edit]- North American B-25 Mitchell Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Joe Baugher, American Military Aircraft: US Bomber Aircraft

- "How to Fly the North American B-25 "Mitchell" Medium Bomber (1944)" on YouTube

- I Fly Mitchell's, February 1944 Popular Science article on B-25s in North Africa Theater

- Flying Big Gun, February 1944, Popular Science article on 75 mm cannon mount

- Early B-25 model's tail gun position, extremely rare photo

- A collection photos of the Marine VMB-613 post in the Kwajalein Island at the University of Houston Digital Library Archived 15 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Hi-res spherical panoramas; B-25H: A look inside & out – "Barbie III"

- (1943) Report No. NA-5785 Temporary Handbook of Erection and Maintenance Instructions for the B-25 H-1-NA Medium Bombardment Airplanes[dead link]

- "The B-25 Mitchell in the USSR", an account of the service history of the Mitchell in the Soviet Union's VVS during World War II

- Lake Murray's Mitchell

- B-25 Recovery and Preservation Project Rubicon Foundation

- Pilot training manual for the Mitchell bomber B-25 Archived 16 August 2024 at the Wayback Machine – The Museum of Flight Digital Collections

- B-25 instructor's manual – The Museum of Flight Digital Collections

.jpg/250px-B25_Mitchell_-_Chino_Airshow_2014_(14033501440).jpg)

.jpg)