Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bicycle

View on Wikipedia

| Bicycle | |

|---|---|

The most popular bicycle model—and most popular vehicle of any kind in the world—is the Chinese Flying Pigeon, with about 500 million produced.[1] | |

| Classification | Vehicle |

| Application | Transportation |

| Fuel source | Human or motor-power |

| Wheels | 2 |

| Components | Frame, wheels, tires, saddle, handlebar, pedals, drivetrain |

| Inventor | Karl von Drais, Kirkpatrick MacMillan |

| Invented | 19th century |

| Types | Utility bicycle, mountain bicycle, racing bicycle, touring bicycle, hybrid bicycle, cruiser bicycle, BMX bike, tandem, low rider, tall bike, fixed gear, folding bicycle, amphibious cycle, cargo bike, recumbent, electric bicycle |

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike, push-bike or cycle, is a human-powered or motor-assisted, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, with two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other. A bicycle rider is called a cyclist, or bicyclist.

The bicycle was introduced in the 19th century in Europe. By the early 21st century, there were more than 1 billion bicycles.[1][2]. Bicycles are the principal means of transport in many regions. They also provide a popular form of recreation, and have been adapted for use as children's toys. Bicycles are used for fitness, military and police applications, courier services, bicycle racing, and artistic cycling.

The basic shape and configuration of a typical upright or "safety" bicycle, has changed little since the first chain-driven model was developed around 1885.[3][4][5] However, many details have been improved, especially since the advent of modern materials and computer-aided design. These have allowed for a proliferation of specialized designs for many types of cycling. In the 21st century, electric bicycles have become popular.

The bicycle's invention has had an enormous effect on society, both in terms of culture and of advancing modern industrial methods. Several components that played a key role in the development of the automobile were initially invented for use in the bicycle, including ball bearings, pneumatic tires, chain-driven sprockets, and tension-spoked wheels.[6]

Etymology

[edit]The word bicycle first appeared in English print in The Daily News in 1868, to describe "Bysicles and trysicles" on the "Champs Elysées and Bois de Boulogne".[7] The word was first used in 1847 in a French publication to describe an unidentified two-wheeled vehicle, possibly a carriage.[7] The design of the bicycle was an advance on the velocipede, although the words were used with some degree of overlap for a time.[7][8]

Other words for bicycle include "bike",[9] "pushbike",[10] "pedal cycle",[11] or "cycle".[12] In Unicode, the code point for "bicycle" is 0x1F6B2. The entity 🚲 in HTML produces 🚲.[13]

Although bike and cycle are used interchangeably to refer mostly to two types of two-wheelers, the terms still vary across the world. In India, for example, a cycle[14] refers only to a two-wheeler using pedal power whereas the term bike is used to describe a two-wheeler using internal combustion engine or electric motors as a source of motive power instead of motorcycle/motorbike.

History

[edit]The "dandy horse",[15] also called Draisienne or Laufmaschine ("running machine"), was the first human means of transport to use only two wheels in tandem and was invented by the German Baron Karl von Drais. It is regarded as the first bicycle and von Drais is seen as the "father of the bicycle",[16][17][18][19] but it did not have pedals.[20][21][22][23] Von Drais introduced it to the public in Mannheim in 1817 and in Paris in 1818.[24][25] Its rider sat astride a wooden frame supported by two in-line wheels and pushed the vehicle along with his or her feet while steering the front wheel.[24]

The first mechanically propelled, two-wheeled vehicle may have been built by Kirkpatrick MacMillan, a Scottish blacksmith, in 1839, although the claim is often disputed.[26] He is also associated with the first recorded instance of a cycling traffic offense, when a Glasgow newspaper in 1842 reported an accident in which an anonymous "gentleman from Dumfries-shire... bestride a velocipede... of ingenious design" knocked over a little girl in Glasgow and was fined five shillings (equivalent to £30 in 2023).[27]

In the early 1860s, the Frenchmen Pierre Michaux and Pierre Lallement took bicycle design in a new direction by adding a mechanical crank drive with pedals on an enlarged front wheel (the velocipede). This was the first in mass production. Another French inventor named Douglas Grasso had a failed prototype of Pierre Lallement's bicycle several years earlier. Several inventions followed using rear-wheel drive, the best known being the rod-driven velocipede by Scotsman Thomas McCall in 1869. In that same year, bicycle wheels with wire spokes were patented by Eugène Meyer of Paris.[28] The French vélocipède, made of iron and wood, developed into the "penny-farthing" (historically known as an "ordinary bicycle", a retronym, since there was then no other kind).[29] It featured a tubular steel frame on which were mounted wire-spoked wheels with solid rubber tires. These bicycles were difficult to ride due to their high seat and poor weight distribution. In 1868, Rowley Turner, a sales agent of the Coventry Sewing Machine Company (which soon became the Coventry Machinists Company), brought a Michaux cycle to Coventry, England. His uncle, Josiah Turner, and business partner James Starley, used this as a basis for the 'Coventry Model' in what became Britain's first cycle factory.[30]

The dwarf ordinary addressed some of these faults by reducing the front wheel diameter and setting the seat further back. This, in turn, required gearing—effected in a variety of ways—to efficiently use pedal power. Having to both pedal and steer via the front wheel remained a problem. Englishman J.K. Starley (nephew of James Starley), J.H. Lawson, and Shergold solved this problem by introducing the chain drive (originated by the unsuccessful "bicyclette" of Englishman Henry Lawson),[31] connecting the frame-mounted cranks to the rear wheel. These models were known as safety bicycles, dwarf safeties, or upright bicycles for their lower seat height and better weight distribution. Although, without pneumatic tires, the ride of the smaller-wheeled bicycle would be much rougher than that of the larger-wheeled variety. Starley's 1885 Rover, manufactured in Coventry[32] is usually described as the first recognizably modern bicycle.[33] Soon, the seat tube was added, which created the modern bike's double-triangle diamond frame.

Further innovations increased comfort and ushered in a second bicycle craze, the 1890s Golden Age of Bicycles. In 1888, Scotsman John Boyd Dunlop introduced the first practical pneumatic tire, which soon became universal. Willie Hume demonstrated the supremacy of Dunlop's tyres in 1889, winning the tyre's first-ever races in Ireland and then England.[34][35] Soon after, the rear freewheel was developed, enabling the rider to coast. This refinement led to the 1890s invention[36] of coaster brakes. Dérailleur gears and hand-operated Bowden cable-pull brakes were also developed during these years, but were only slowly adopted by casual riders.

The Svea Velocipede with vertical pedal arrangement and locking hubs was introduced in 1892 by the Swedish engineers Fredrik Ljungström and Birger Ljungström. It attracted attention at the World Fair and was produced in a few thousand units.

In the 1870s, many cycling clubs flourished. They were popular in a time when there were no cars on the market and the principal mode of transportation was horse-drawn vehicles. Among the earliest clubs was The Bicycle Touring Club, which has operated since 1878. By the turn of the century, cycling clubs flourished on both sides of the Atlantic, and touring and racing became widely popular. The Raleigh Bicycle Company was founded in Nottingham, England in 1888. It became the biggest bicycle manufacturing company in the world, making over two million bikes per year.[37]

Bicycles and horse buggies were the two mainstays of private transportation just prior to the automobile, and the grading of smooth roads in the late 19th century was stimulated by the widespread advertising, production, and use of these devices.[5] More than 1 billion bicycles have been manufactured worldwide as of the early 21st century.[1][2] Bicycles are the most common vehicle of any kind in the world, and the most numerous model of any kind of vehicle, whether human-powered or motor vehicle, is the Chinese Flying Pigeon, with numbers exceeding 500 million.[1] The next most numerous vehicle, the Honda Super Cub motorcycle, has more than 100 million units made,[38] while most produced car, the Toyota Corolla, has reached 44 million and counting.[39][40][41][42]

-

Women on bicycles on unpaved road, US, late 19th century

-

A penny-farthing or ordinary bicycle photographed in the Škoda Auto museum in the Czech Republic

-

The Svea Velocipede by Fredrik Ljungström and Birger Ljungström, exhibited at the Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology

-

Bicycle in Plymouth, England, at the start of the 20th century

-

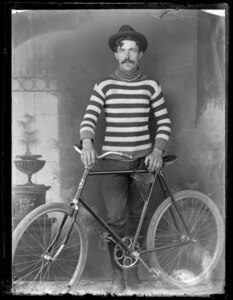

Man with a bicycle in Glengarry County, Ontario between 1895 and 1910

-

The first bicycle by Baron Karl von Drais

-

Drawing from an 1896 newspaper of The London Hansom Cycle

-

Wooden draisine (around 1820), the first two-wheeler and as such the archetype of the bicycle

-

Michaux's son on a velocipede 1868

-

Cyclists' Touring Club sign on display at the National Museum of Scotland

-

John Boyd Dunlop on a bicycle c. 1915

-

1886 Rover safety bicycle at the British Motor Museum. The first modern bicycle, it featured a rear-wheel-drive, chain-driven cycle with two similar-sized wheels. Dunlop's pneumatic tire was added to the bicycle in 1888.

Uses

[edit]Bicycles are used for transportation, bicycle commuting, and utility cycling.[43] They are also used professionally by mail carriers, paramedics, police, messengers, and general delivery services. Military uses of bicycles include communications, reconnaissance, troop movement, supply of provisions, and patrol, such as in bicycle infantries.[44]

They are also used for recreational purposes, including bicycle touring, mountain biking, physical fitness, and play. Bicycle sports include racing, BMX racing, track racing, criterium, roller racing, sportives and time trials. Major multi-stage professional events are the Giro d'Italia, the Tour de France, the Vuelta a España, the Tour de Pologne, and the Volta a Portugal. They are also used for entertainment and pleasure in other ways, such as in organised mass rides, artistic cycling and freestyle BMX.

Technical aspects

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

The bicycle has undergone continual adaptation and improvement since its inception. These innovations have continued with the advent of modern materials and computer-aided design, allowing for a proliferation of specialized bicycle types, improved bicycle safety, and riding comfort.[45]

Types

[edit]

Bicycles can be categorized in many different ways: by function, by number of riders, by general construction, by gearing or by means of propulsion. The more common types include utility bicycles, mountain bicycles, racing bicycles, touring bicycles, hybrid bicycles, cruiser bicycles, and BMX bikes. Less common are tandems, low riders, tall bikes, fixed gear, folding models, amphibious bicycles, cargo bikes, recumbents and electric bicycles.

Unicycles, tricycles and quadracycles are not strictly bicycles, as they have respectively one, three and four wheels, but are often referred to informally as "bikes" or "cycles".

Dynamics

[edit]

A bicycle stays upright while moving forward by being steered so as to keep its center of mass over the wheels.[46] This steering is usually provided by the rider, but under certain conditions, may be provided by the bicycle itself.[47]

The combined center of mass of a bicycle and its rider must lean into a turn to successfully navigate it. This lean is induced by a method known as countersteering, which can be performed by the rider turning the handlebars directly with the hands[48] or indirectly by leaning the bicycle.[49]

Short-wheelbase or tall bicycles, when braking, can generate enough stopping force at the front wheel to flip longitudinally.[50] The act of purposefully using this force to lift the rear wheel and balance on the front without tipping over is a trick known as a stoppie, endo, or front wheelie.

Performance

[edit]The bicycle is extraordinarily efficient in both biological and mechanical terms. The bicycle is the most efficient human-powered means of transportation in terms of energy a person must expend to travel a given distance.[51] From a mechanical viewpoint, up to 99% of the energy delivered by the rider into the pedals is transmitted to the wheels, although the use of gearing mechanisms may reduce this by 10–15%.[52][53] In terms of the ratio of cargo weight a bicycle can carry to total weight, it is also an efficient means of cargo transportation.

A human traveling on a bicycle at low to medium speeds of around 16–24 km/h (10–15 mph) uses only the power required to walk. Air drag, which is proportional to the square of speed, requires dramatically higher power outputs as speeds increase. If the rider is sitting upright, the rider's body creates about 75% of the total drag of the bicycle/rider combination. Drag can be reduced by seating the rider in a more aerodynamically streamlined position. Drag can also be reduced by covering the bicycle with an aerodynamic fairing. The fastest recorded unpaced speed on a flat surface is 144.18 km/h (89.59 mph).[54]

In addition, the carbon dioxide generated in the production and transportation of the food required by the bicyclist, per mile traveled, is less than 1⁄10 that generated by energy efficient motorcars.[55]

-

Balance bicycle for young children

Parts

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

Frame

[edit]The great majority of modern bicycles have a frame with upright seating that looks much like the first chain-driven bike.[3][4][5] These upright bicycles almost always feature the diamond frame, a truss consisting of two triangles: the front triangle and the rear triangle. The front triangle consists of the head tube, top tube, down tube, and seat tube. The head tube contains the headset, the set of bearings that allows the fork to turn smoothly for steering and balance. The top tube connects the head tube to the seat tube at the top, and the down tube connects the head tube to the bottom bracket. The rear triangle consists of the seat tube and paired chain stays and seat stays. The chain stays run parallel to the chain, connecting the bottom bracket to the rear dropout, where the axle for the rear wheel is held. The seat stays connect the top of the seat tube (at or near the same point as the top tube) to the rear fork ends.

Historically, women's bicycle frames had a top tube that connected in the middle of the seat tube instead of the top, resulting in a lower standover height at the expense of compromised structural integrity, since this places a strong bending load in the seat tube, and bicycle frame members are typically weak in bending. This design, referred to as a step-through frame or as an open frame, allows the rider to mount and dismount in a dignified way while wearing a skirt or dress. While some women's bicycles continue to use this frame style, there is also a variation, the mixte, which splits the top tube laterally into two thinner top tubes that bypass the seat tube on each side and connect to the rear fork ends. The ease of stepping through is also appreciated by those with limited flexibility or other joint problems. Because of its persistent image as a "women's" bicycle, step-through frames are not common for larger frames.

Step-throughs were popular partly for practical reasons and partly for social mores of the day. For most of the history of bicycles' popularity women have worn long skirts, and the lower frame accommodated these better than the top-tube. Furthermore, it was considered "unladylike" for women to open their legs to mount and dismount—in more conservative times women who rode bicycles at all were vilified as immoral or immodest. These practices were akin to the older practice of riding horse sidesaddle.[56]

Another style is the recumbent bicycle. These are inherently more aerodynamic than upright versions, as the rider may lean back onto a support and operate pedals that are on about the same level as the seat. The world's fastest bicycle is a recumbent bicycle but this type was banned from competition in 1934 by the Union Cycliste Internationale.[57]

Historically, materials used in bicycles have followed a similar pattern as in aircraft, the goal being high strength and low weight. Since the late 1930s, alloy steels have been used for frame and fork tubes in higher quality machines. By the 1980s, aluminum welding techniques had improved to the point that aluminum tube could safely be used in place of steel. Since then aluminum alloy frames and other components have become popular due to their light weight, and most mid-range bikes are now principally aluminum alloy of some kind.[where?] More expensive bikes use carbon fibre due to its significantly lighter weight and profiling ability, allowing designers to make a bike both stiff and compliant by manipulating the lay-up. Virtually all professional racing bicycles now use carbon fibre frames, as they have the best strength to weight ratio. A typical modern carbon fiber frame can weigh less than 2 pounds (1 kg).

Other exotic frame materials include titanium and advanced alloys. Bamboo, a natural composite material with high strength-to-weight ratio and stiffness[58] has been used for bicycles since 1894.[59] Recent versions use bamboo for the primary frame with glued metal connections and parts, priced as exotic models.[59][60][61]

-

Diagram of a bicycle

-

A Triumph with a step-through frame

-

A carbon fiber Trek Y-Foil from the late 1990s

Drivetrain and gearing

[edit]The drivetrain begins with pedals which rotate the cranks, which are held in axis by the bottom bracket. Most bicycles use a chain to transmit power to the rear wheel. A very small number of bicycles use a shaft drive to transmit power, or special belts. Hydraulic bicycle transmissions have been built, but they are currently inefficient and complex.

Since cyclists' legs are most efficient over a narrow range of pedaling speeds, or cadence, a variable gear ratio helps a cyclist to maintain an optimum pedalling speed while covering varied terrain. Some, mainly utility, bicycles use hub gears with between 3 and 14 ratios, but most use the generally more efficient dérailleur system, by which the chain is moved between different cogs called chainrings and sprockets to select a ratio. A dérailleur system normally has two dérailleurs, or mechs, one at the front to select the chainring and another at the back to select the sprocket. Most bikes have two or three chainrings, and from 5 to 12 sprockets on the back, with the number of theoretical gears calculated by multiplying front by back. In reality, many gears overlap or require the chain to run diagonally, so the number of usable gears is fewer.

An alternative to chaindrive is to use a synchronous belt. These are toothed and work much the same as a chain—popular with commuters and long distance cyclists they require little maintenance. They cannot be shifted across a cassette of sprockets, and are used either as single speed or with a hub gear.

Different gears and ranges of gears are appropriate for different people and styles of cycling. Multi-speed bicycles allow gear selection to suit the circumstances: a cyclist could use a high gear when cycling downhill, a medium gear when cycling on a flat road, and a low gear when cycling uphill. In a lower gear, every turn of the pedals leads to fewer rotations of the rear wheel. This allows the energy required to move the same distance to be distributed over more pedal turns, reducing fatigue when riding uphill, with a heavy load, or against strong winds. A higher gear allows a cyclist to make fewer pedal turns to maintain a given speed, but with more effort per turn of the pedals.

With a chain drive transmission, a chainring attached to a crank drives the chain, which in turn rotates the rear wheel via the rear sprocket(s) (cassette or freewheel). There are four gearing options: two-speed hub gear integrated with chain ring, up to 3 chain rings, up to 12 sprockets, hub gear built into rear wheel (3-speed to 14-speed). The most common options are either a rear hub or multiple chain rings combined with multiple sprockets (other combinations of options are possible but less common).

-

A bicycle with shaft drive instead of a chain

-

A set of rear sprockets (also known as a cassette) and a derailleur

-

Hub gear

Steering

[edit]

The handlebars connect to the stem that connects to the fork that connects to the front wheel, and the whole assembly connects to the bike and rotates about the steering axis via the headset bearings. Three styles of handlebar are common. Upright handlebars, the norm in Europe and elsewhere until the 1970s, curve gently back toward the rider, offering a natural grip and comfortable upright position. Drop handlebars "drop" as they curve forward and down, offering the cyclist best braking power from a more aerodynamic "crouched" position, as well as more upright positions in which the hands grip the brake lever mounts, the forward curves, or the upper flat sections for increasingly upright postures. Mountain bikes generally feature a 'straight handlebar' or 'riser bar' with varying degrees of sweep backward and centimeters rise upwards, as well as wider widths which can provide better handling due to increased leverage against the wheel.

Seating

[edit]

Saddles also vary with rider preference, from the cushioned ones favored by short-distance riders to narrower saddles which allow more room for leg swings. Comfort depends on riding position. With comfort bikes and hybrids, cyclists sit high over the seat, their weight directed down onto the saddle, such that a wider and more cushioned saddle is preferable. For racing bikes where the rider is bent over, weight is more evenly distributed between the handlebars and saddle, the hips are flexed, and a narrower and harder saddle is more efficient. Differing saddle designs exist for male and female cyclists, accommodating the genders' differing anatomies and sit bone width measurements, although bikes typically are sold with saddles most appropriate for men. Suspension seat posts and seat springs provide comfort by absorbing shock but can add to the overall weight of the bicycle.

A recumbent bicycle has a reclined chair-like seat that some riders find more comfortable than a saddle, especially riders who suffer from certain types of seat, back, neck, shoulder, or wrist pain. Recumbent bicycles may have either under-seat or over-seat steering.

Brakes

[edit]

Bicycle brakes may be rim brakes, in which friction pads are compressed against the wheel rims; hub brakes, where the mechanism is contained within the wheel hub, or disc brakes, where pads act on a rotor attached to the hub. Most road bicycles use rim brakes, but some use disc brakes.[63] Disc brakes are more common for mountain bikes, tandems and recumbent bicycles than on other types of bicycles, due to their increased power, coupled with an increased weight and complexity.[64]

With hand-operated brakes, force is applied to brake levers mounted on the handlebars and transmitted via Bowden cables or hydraulic lines to the friction pads, which apply pressure to the braking surface, causing friction which slows the bicycle down. A rear hub brake may be either hand-operated or pedal-actuated, as in the back pedal coaster brakes which were popular in North America until the 1960s.

Track bicycles do not have brakes, because all riders ride in the same direction around a track which does not necessitate sharp deceleration. Track riders are still able to slow down because all track bicycles are fixed-gear, meaning that there is no freewheel. Without a freewheel, coasting is impossible, so when the rear wheel is moving, the cranks are moving. To slow down, the rider applies resistance to the pedals, acting as a braking system which can be as effective as a conventional rear wheel brake, but not as effective as a front wheel brake.[65]

Suspension

[edit]Bicycle suspension refers to the system or systems used to suspend the rider and all or part of the bicycle. This serves two purposes: to keep the wheels in continuous contact with the ground, improving control, and to isolate the rider and luggage from jarring due to rough surfaces, improving comfort.

Bicycle suspensions are used primarily on mountain bicycles, but are also common on hybrid bicycles, as they can help deal with problematic vibration from poor surfaces. Suspension is especially important on recumbent bicycles, since while an upright bicycle rider can stand on the pedals to achieve some of the benefits of suspension, a recumbent rider cannot.

Basic mountain bicycles and hybrids usually have front suspension only, whilst more sophisticated ones also have rear suspension. Road bicycles tend to have no suspension.

Wheels and tires

[edit]

The wheel axle fits into fork ends in the frame and fork. A pair of wheels may be called a wheelset, especially in the context of ready-built "off the shelf", performance-oriented wheels.

Tires vary enormously depending on their intended purpose. Road bicycles use tires 0.7 to 1.0 inch (18 to 25 mm) wide, most often completely smooth, or slick, and inflated to high pressure to roll fast on smooth surfaces. Off-road tires are usually between 1.5 and 2.5 inches (38 and 64 mm) wide, and have treads for gripping in muddy conditions or metal studs for ice.

Groupset

[edit]Groupset generally refers to all of the components that make up a bicycle excluding the bicycle frame, fork, stem, wheels, tires, and rider contact points, such as the saddle and handlebars.

Accessories

[edit]

Some components, which are often optional accessories on sports bicycles, are standard features on utility bicycles to enhance their usefulness, comfort, safety and visibility. Fenders with spoilers (mudflaps) protect the cyclist and moving parts from spray when riding through wet areas. In some countries (e.g. Germany, UK), fenders are called mudguards. The chainguards protect clothes from oil on the chain while preventing clothing from being caught between the chain and crankset teeth. Kick stands keep bicycles upright when parked, and bike locks deter theft. Front-mounted baskets, front or rear luggage carriers or racks, and panniers mounted above either or both wheels can be used to carry equipment or cargo. Pegs can be fastened to one, or both of the wheel hubs to either help the rider perform certain tricks, or allow a place for extra riders to stand, or rest.[citation needed] Parents sometimes add rear-mounted child seats, an auxiliary saddle fitted to the crossbar, or both to transport children. Bicycles can also be fitted with a hitch to tow a trailer for carrying cargo, a child, or both.

Toe-clips and toestraps and clipless pedals help keep the foot locked in the proper pedal position and enable cyclists to pull and push the pedals. Technical accessories include cyclocomputers for measuring speed, distance, heart rate, GPS data etc. Other accessories include lights, reflectors, mirrors, racks, trailers, bags, water bottles and cages, and bell.[66] Bicycle lights, reflectors, and helmets are required by law in some geographic regions depending on the legal code. It is more common to see bicycles with bottle generators, dynamos, lights, fenders, racks and bells in Europe. Bicyclists also have specialized form fitting and high visibility clothing.

Children's bicycles may be outfitted with cosmetic enhancements such as bike horns, streamers, and spoke beads.[67] Training wheels are sometimes used when learning to ride, but a dedicated balance bike teaches independent riding more effectively.[68][69]

Bicycle helmets can reduce injury in the event of a collision or accident, and a suitable helmet is legally required of riders in many jurisdictions.[70][71] Helmets may be classified as an accessory[66] or as an item of clothing.[72]

Bike trainers are used to enable cyclists to cycle while the bike remains stationary. They are frequently used to warm up before races or indoors when riding conditions are unfavorable.[73]

Standards

[edit]A number of formal and industry standards exist for bicycle components to help make spare parts exchangeable and to maintain a minimum product safety.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has a special technical committee for cycles, TC149, that has the scope of "Standardization in the field of cycles, their components and accessories with particular reference to terminology, testing methods and requirements for performance and safety, and interchangeability".

The European Committee for Standardization (CEN) also has a specific Technical Committee, TC333, that defines European standards for cycles. Their mandate states that EN cycle standards shall harmonize with ISO standards. Some CEN cycle standards were developed before ISO published their standards, leading to strong European influences in this area. European cycle standards tend to describe minimum safety requirements, while ISO standards have historically harmonized parts geometry.[note 1]

Maintenance and repair

[edit]Like all devices with mechanical moving parts, bicycles require a certain amount of regular maintenance and replacement of worn parts. A bicycle is relatively simple compared with a car, so some cyclists choose to do at least part of the maintenance themselves. Some components are easy to handle using relatively simple tools, while other components may require specialist manufacturer-dependent tools.

Many bicycle components are available at several different price/quality points; manufacturers generally try to keep all components on any particular bike at about the same quality level, though at the very cheap end of the market there may be some skimping on less obvious components (e.g. bottom bracket).

- There are several hundred assisted-service community bicycle organizations worldwide.[74] At a community bicycle organization, laypeople bring in bicycles needing repair or maintenance; volunteers teach them how to do the required steps.

- Full service is available from bicycle mechanics at a local bike shop.

- In areas where it is available, some cyclists purchase roadside assistance from companies such as the Better World Club or the American Automobile Association.

Maintenance

[edit]The most basic maintenance item is keeping the tires correctly inflated; this can make a noticeable difference as to how the bike feels to ride. Bicycle tires usually have a marking on the sidewall indicating the pressure appropriate for that tire. Bicycles use much higher pressures than cars: car tires are normally in the range of 30 to 40 pounds per square inch (210 to 280 kPa), whereas bicycle tires are normally in the range of 60 to 100 pounds per square inch (410 to 690 kPa).

Another basic maintenance item is regular lubrication of the chain and pivot points for derailleurs and brake components. Most of the bearings on a modern bike are sealed and grease-filled and require little or no attention; such bearings will usually last for 10,000 miles (16,000 km) or more. The crank bearings require periodic maintenance, which involves removing, cleaning and repacking with the correct grease.

The chain and the brake blocks are the components which wear out most quickly, so these need to be checked from time to time, typically every 500 miles (800 km) or so. Most local bike shops will do such checks for free. Note that when a chain becomes badly worn, it will also wear out the rear cogs/cassette and eventually the chain ring(s), so replacing a chain when only moderately worn will prolong the life of other components.

Over the longer term, tires do wear out, after 2,000 to 5,000 miles (3,200 to 8,000 km); a rash of punctures is often the most visible sign of a worn tire.

Repair

[edit]Very few bicycle components can actually be repaired; replacement of the failing component is the normal practice.

The most common roadside problem is a puncture of the tire's inner tube. A patch kit may be employed to fix the puncture or the tube can be replaced, though the latter solution comes at a greater cost and waste of material.[75] Some brands of tires are much more puncture-resistant than others, often incorporating one or more layers of Kevlar; the downside of such tires is that they may be heavier and more difficult to fit and remove.

Tools

[edit]

There are specialized bicycle tools for use both in the shop and at the roadside. Many cyclists carry tool kits. These may include a tire patch kit (which, in turn, may contain any combination of a hand pump or CO2 pump, tire levers, spare tubes, self-adhesive patches, or tube-patching material, an adhesive, a piece of sandpaper or a metal grater (for roughening the tube surface to be patched) and sometimes even a block of French chalk), wrenches, hex keys, screwdrivers, and a chain tool. Special, thin wrenches are often required for maintaining various screw-fastened parts, specifically, the frequently lubricated ball-bearing "cones".[76][77] There are also cycling-specific multi-tools that combine many of these implements into a single compact device. More specialized bicycle components may require more complex tools, including proprietary tools specific for a given manufacturer.

Social and historical aspects

[edit]The bicycle has had a considerable effect on human society, in both the cultural and industrial realms.[78][79]

In daily life

[edit]

Around the turn of the 20th century, bicycles reduced crowding in inner-city tenements by allowing workers to commute from more spacious dwellings in the suburbs. They also reduced dependence on horses. Bicycles allowed people to travel for leisure into the country, since bicycles were three times as energy efficient as walking and three to four times as fast.

In built-up cities around the world, urban planning uses cycling infrastructure like bikeways to reduce traffic congestion and air pollution.[80] A number of cities around the world have implemented schemes known as bicycle sharing systems or community bicycle programs.[81][82] The first of these was the White Bicycle plan in Amsterdam in 1965. It was followed by yellow bicycles in La Rochelle and green bicycles in Cambridge. These initiatives complement public transport systems and offer an alternative to motorized traffic to help reduce congestion and pollution.[83] In Europe, especially in the Netherlands and parts of Germany and Denmark, bicycle commuting is common. In Copenhagen, a cyclists' organization runs a Cycling Embassy that promotes biking for commuting and sightseeing. The United Kingdom has a tax break scheme (IR 176) that allows employees to buy a new bicycle tax free to use for commuting.[84]

In the Netherlands, all train stations offer free bicycle parking, or a more secure parking place for a small fee, with the larger stations also offering bicycle repair shops. Cycling is so popular that the parking capacity may be exceeded, while in some places such as Delft, the capacity is usually exceeded.[85] In Trondheim in Norway, the Trampe bicycle lift has been developed to encourage cyclists by giving assistance on a steep hill. Buses in many cities have bicycle carriers mounted on the front.

There are towns in some countries where bicycle culture has been an integral part of the landscape for generations, even without much official support. That is the case of Ílhavo, in Portugal.

In cities where bicycles are not integrated into the public transportation system, commuters often use bicycles as elements of a mixed-mode commute, where the bike is used to travel to and from train stations or other forms of rapid transit. Some students who commute several miles drive a car from home to a campus parking lot, then ride a bicycle to class. Folding bicycles are useful in these scenarios, as they are less cumbersome when carried aboard. Los Angeles removed a small amount of seating on some trains to make more room for bicycles and wheel chairs.[86]

Some US companies, notably in the tech sector, are developing both innovative cycle designs and cycle-friendliness in the workplace. Foursquare, whose CEO Dennis Crowley "pedaled to pitch meetings ... [when he] was raising money from venture capitalists" on a two-wheeler, chose a new location for its New York headquarters "based on where biking would be easy". Parking in the office was also integral to HQ planning. Mitchell Moss, who runs the Rudin Center for Transportation Policy & Management at New York University, said in 2012: "Biking has become the mode of choice for the educated high tech worker".[87]

Bicycles offer an important mode of transport in many developing countries. Until recently, bicycles have been a staple of everyday life throughout Asian countries. They are the most frequently used method of transport for commuting to work, school, shopping, and life in general. In Europe, bicycles are commonly used.[88] They also offer a degree of exercise to keep individuals healthy.[89]

Bicycles are also celebrated in the visual arts. An example of this is the Bicycle Film Festival, a film festival hosted all around the world.

Poverty alleviation

[edit]

Bicycle poverty reduction is the concept that access to bicycles and the transportation infrastructure to support them can dramatically reduce poverty.[90][91][92][93] This has been demonstrated in various pilot projects in South Asia and Africa.[94][95][96] Experiments done in Africa (Uganda and Tanzania) and Sri Lanka on hundreds of households have shown that a bicycle can increase the income of a poor family by as much as 35%.[94][97][98]

Transport, if analyzed for the cost–benefit analysis for rural poverty alleviation, has given one of the best returns in this regard. For example, road investments in India were a staggering 3–10 times more effective than almost all other investments and subsidies in rural economy in the decade of the 1990s. A road can ease transport on a macro level, while bicycle access supports it at the micro level. In that sense, the bicycle can be one of the most effective means to eradicate poverty in poor nations.Female emancipation

[edit]

The safety bicycle gave women unprecedented mobility, contributing to their emancipation in Western nations. As bicycles became safer and cheaper, more women had access to the personal freedom that bicycles embodied, and so the bicycle came to symbolize the New Woman of the late 19th century, especially in Britain and the United States.[4][100] The bicycle craze in the 1890s also led to a movement for so-called rational dress, which helped liberate women from corsets and ankle-length skirts and other restrictive garments, substituting the then-shocking bloomers.[4]

The bicycle was recognized by 19th-century feminists and suffragists as a "freedom machine" for women. American Susan B. Anthony said in a New York World interview on 2 February 1896: "I think it has done more to emancipate woman than any one thing in the world. I rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel. It gives her a feeling of self-reliance and independence the moment she takes her seat; and away she goes, the picture of untrammelled womanhood."[101]: 859 In 1895 Frances Willard, the tightly laced president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, wrote A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, with Some Reflections by the Way, a 75-page illustrated memoir praising "Gladys", her bicycle, for its "gladdening effect" on her health and political optimism.[99] Willard used a cycling metaphor to urge other suffragists to action.[99]

In 1985, Georgena Terry started the first women-specific bicycle company. Her designs featured frame geometry and wheel sizes chosen to better fit women, with shorter top tubes and more suitable reach.[102]

Economic implications

[edit]

Bicycle manufacturing proved to be a training ground for other industries and led to the development of advanced metalworking techniques, both for the frames themselves and for special components such as ball bearings, washers, and sprockets. These techniques later enabled skilled metalworkers and mechanics to develop the components used in early automobiles and aircraft.

Wilbur and Orville Wright, a pair of businessmen, ran the Wright Cycle Company which designed, manufactured and sold their bicycles during the bike boom of the 1890s.[103]

They also served to teach the industrial models later adopted, including mechanization and mass production (later copied and adopted by Ford and General Motors),[104][105][106] vertical integration[105] (also later copied and adopted by Ford), aggressive advertising[107] (as much as 10% of all advertising in US periodicals in 1898 was by bicycle makers),[108] lobbying for better roads (which had the side benefit of acting as advertising, and of improving sales by providing more places to ride),[106] all first practiced by Pope.[106] In addition, bicycle makers adopted the annual model change[104][109] (later derided as planned obsolescence, and usually credited to General Motors), which proved very successful.[110]

Early bicycles were an example of conspicuous consumption, being adopted by the fashionable elites.[111][112][113][104][114][115][116][117] In addition, by serving as a platform for accessories, which could ultimately cost more than the bicycle itself, it paved the way for the likes of the Barbie doll.[104][118][119]

Bicycles helped create, or enhance, new kinds of businesses, such as bicycle messengers,[120] traveling seamstresses,[121] riding academies,[122] and racing rinks.[123][122] Their board tracks were later adapted to early motorcycle and automobile racing. There were a variety of new inventions, such as spoke tighteners,[124] and specialized lights,[119][124] socks and shoes,[125] and even cameras, such as the Eastman Company's Poco.[126] Probably the best known and most widely used of these inventions, adopted well beyond cycling, is Charles Bennett's Bike Web, which came to be called the jock strap.[127]

They also presaged a move away from public transit[128] that would explode with the introduction of the automobile.

J. K. Starley's company became the Rover Cycle Company Ltd. in the late 1890s, and then renamed the Rover Company when it started making cars. Morris Motors Limited (in Oxford) and Škoda also began in the bicycle business, as did the Wright brothers.[129] Alistair Craig, whose company eventually emerged to become the engine manufacturers Ailsa Craig, also started from manufacturing bicycles, in Glasgow in March 1885.

In general, US and European cycle manufacturers used to assemble cycles from their own frames and components made by other companies, although very large companies (such as Raleigh) used to make almost every part of a bicycle (including bottom brackets, axles, etc.) In recent years, those bicycle makers have greatly changed their methods of production. Now, almost none of them produce their own frames.

Many newer or smaller companies only design and market their products; the actual production is done by Asian companies. For example, some 60% of the world's bicycles are now being made in China. Despite this shift in production, as nations such as China and India become more wealthy, their own use of bicycles has declined due to the increasing affordability of cars and motorcycles.[130] One of the major reasons for the proliferation of Chinese-made bicycles in foreign markets is the lower cost of labor in China.[131]

In line with the European financial crisis of that time, in 2011 the number of bicycle sales in Italy (1.75 million) passed the number of new car sales.[132]

Environmental impact

[edit]

One of the profound economic implications of bicycle use is that it liberates the user from motor fuel consumption. (Ballantine, 1972) The bicycle is an inexpensive, fast, healthy and environmentally friendly mode of transport. Ivan Illich stated that bicycle use extended the usable physical environment for people, while alternatives such as cars and motorways degraded and confined people's environment and mobility.[133] Currently, two billion bicycles are in use around the world. Children, students, professionals, laborers, civil servants and seniors are pedaling around their communities. They all experience the freedom and the natural opportunity for exercise that the bicycle easily provides. Bicycle also has lowest carbon intensity of travel.[134]

Manufacturing

[edit]

The global bicycle market is $61 billion in 2011.[135] As of 2009[update], 130 million bicycles were sold every year globally and 66% of them were made in China.[136]

| Year | production (M) | sales (M) |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 14.531 | 18.945 |

| 2001 | 13.009 | 17.745 |

| 2002 | 12.272 | 17.840 |

| 2003 | 12.828 | 20.206 |

| 2004 | 13.232 | 20.322 |

| 2005 | 13.218 | 20.912 |

| 2006 | 13.320 | 21.033 |

| 2007 | 13.086 | 21.344 |

| 2008 | 13.246 | 20.206 |

| 2009 | 12.178 | 19.582 |

| 2010 | 12.241 | 20.461 |

| 2011 | 11.758 | 20.039 |

| 2012 | 11.537 | 19.719 |

| 2013 | 11.360 | 19.780 |

| 2014 | 11.939 | 20.234 |

| Country | Production (M) | Parts (M€) | Sales (M) | Avg | Sales (M€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | 2.729 | 491 | 1.696 | 288 | 488.4 |

| Germany | 2.139 | 286 | 4.100 | 528 | 2164.8 |

| Poland | .991 | 58 | 1.094 | 380 | 415.7 |

| Bulgaria | .950 | 9 | .082 | 119 | 9.8 |

| The Netherlands | .850 | 85 | 1.051 | 844 | 887 |

| Romania | .820 | 220 | .370 | 125 | 46.3 |

| Portugal | .720 | 120 | .340 | 160 | 54.4 |

| France | .630 | 170 | 2.978 | 307 | 914.2 |

| Hungary | .370 | 10 | .044 | 190 | 8.4 |

| Spain | .356 | 10 | 1.089 | 451 | 491.1 |

| Czech Republic | .333 | 85 | .333 | 150 | 50 |

| Lithuania | .323 | 0 | .050 | 110 | 5.5 |

| Slovakia | .210 | 9 | .038 | 196 | 7.4 |

| Austria | .138 | 0 | .401 | 450 | 180.5 |

| Greece | .108 | 0 | .199 | 233 | 46.4 |

| Belgium | .099 | 35 | .567 | 420 | 238.1 |

| Sweden | .083 | 0 | .584 | 458 | 267.5 |

| Great Britain | .052 | 34 | 3.630 | 345 | 1252.4 |

| Finland | .034 | 32 | .300 | 320 | 96 |

| Slovenia | .005 | 9 | .240 | 110 | 26.4 |

| Croatia | 0 | 0 | .333 | 110 | 36.6 |

| Cyprus | 0 | 0 | .033 | 110 | 3.6 |

| Denmark | 0 | 0 | .470 | 450 | 211.5 |

| Estonia | 0 | 0 | .062 | 190 | 11.8 |

| Ireland | 0 | 0 | .091 | 190 | 17.3 |

| Latvia | 0 | 0 | .040 | 110 | 4.4 |

| Luxembourg | 0 | 0 | .010 | 450 | 4.5 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 | .011 | 110 | 1.2 |

| EU 28 | 11.939 | 1662 | 20.234 | 392 | 7941.2 |

Legal requirements

[edit]Early in its development, as with automobiles, there were restrictions on the operation of bicycles. Along with advertising, and to gain free publicity, Albert A. Pope litigated on behalf of cyclists.[106]

The 1968 Vienna Convention on Road Traffic of the United Nations considers a bicycle to be a vehicle, and a person controlling a bicycle (whether actually riding or not) is considered an operator or driver.[citation needed][138][139] The traffic codes of many countries reflect these definitions and demand that a bicycle satisfy certain legal requirements before it can be used on public roads. In many jurisdictions, it is an offense to use a bicycle that is not in a roadworthy condition.[140][141]

In some countries, bicycles must have functioning front and rear lights when ridden after dark.[142][143]

Some countries require cyclists to wear helmets, as this may protect riders from head trauma. Countries which require adult cyclists to wear helmets include Spain, New Zealand and Australia. Mandatory helmet wearing is one of the most controversial topics in the cycling world, with proponents arguing that it reduces head injuries and thus is an acceptable requirement, while opponents argue that by making cycling seem more dangerous and cumbersome, it reduces cyclist numbers on the streets, creating an overall negative health effect (fewer people cycling for their own health, and the remaining cyclists being more exposed through a reversed safety in numbers effect).[144]

Theft

[edit]

Bicycles are popular targets for theft, due to their value and ease of resale.[145] The number of bicycles stolen annually is difficult to quantify as a large number of crimes are not reported.[146] Around 50% of the participants in the Montreal International Journal of Sustainable Transportation survey were subjected to a bicycle theft in their lifetime as active cyclists.[147] Most bicycles have serial numbers that can be recorded to verify identity in case of theft.[148]

See also

[edit]- Bicycle and motorcycle geometry

- Bicycle drum brake

- Bicycle fender

- Bicycle lighting

- Bicycle parking station

- Bicycle-friendly

- Bicycle-sharing system

- Cyclability

- Cycling advocacy

- Cycling in the Netherlands

- Danish bicycle VIN-system

- List of bicycle types

- List of films about bicycles and cycling

- Outline of bicycles

- Outline of cycling

- rattleCAD (software for bicycle design)

- Skirt guard

- Twike

- Velomobile

- Wooden bicycle

- World Bicycle Day

Notes

[edit]- ^ The TC149 ISO bicycle committee, including the TC149/SC1 ("Cycles and major sub-assemblies") subcommittee, has published the following standards:[citation needed]

- ISO 4210 Cycles – Safety requirements for bicycles

- ISO 6692 Cycles – Marking of cycle components

- ISO 6695 Cycles – Pedal axle and crank assembly with square end fitting – Assembly dimensions

- ISO 6696 Cycles – Screw threads used in bottom bracket assemblies

- ISO 6697 Cycles – Hubs and freewheels – Assembly dimensions

- ISO 6698 Cycles – Screw threads used to assemble freewheels on bicycle hubs

- ISO 6699 Cycles – Stem and handlebar bend – Assembly dimensions

- ISO 6701 Cycles – External dimensions of spoke nipples

- ISO 6742 Cycles – Lighting and retro-reflective devices – Photometric and physical requirements

- ISO 8090 Cycles – Terminology (same as BS 6102-4)

- ISO 8098 Cycles – Safety requirements for bicycles for young children

- ISO 8488 Cycles – Screw threads used to assemble head fittings on bicycle forks

- ISO 8562 Cycles – Stem wedge angle

- ISO 10230 Cycles – Splined hub and sprocket – Mating dimensions

- ISO 11243 Cycles – Luggage carriers for bicycles – Concepts, classification and testing

- EN 14764 City and trekking bicycles – Safety requirements and test methods

- EN 14765 Bicycles for young children – Safety requirements and test methods

- EN 14766 Mountain-bicycles – Safety requirements and test methods

- EN 14781 Racing bicycles – Safety requirements and test methods

- EN 14782 Bicycles – Accessories for bicycles – Luggage carriers

- EN 15496 Cycles – Requirements and test methods for cycle locks

- EN 15194 Cycles – Electrically power assisted cycles (Electric bicycle)

- EN 15532 Cycles – Terminology

- 00333011 Cycles – Bicycles trailers – safety requirements and test methods

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Koeppel, Dan (January–February 2007). "Flight of the Pigeon". Bicycling. Vol. 48, no. 1. Rodale. pp. 60–66. ISSN 0006-2073. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Bicycling; A way of life; Faster in town than going by car, bus, tube or on foot". The Economist. 20 April 2011.

- ^ a b Herlihy 2004, pp. 200–50.

- ^ a b c d Herlihy 2004, pp. 266–71.

- ^ a b c Herlihy 2004, p. 280.

- ^ Heitmann, J. A. The Automobile and American Life. McFarland, 2009, ISBN 0-7864-4013-9, pp. 11ff

- ^ a b c "bicycle". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "bicycle (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "bike". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "pushbike". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "pedal cycle". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "cycle". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Transport and Map Symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ "Why has India's Calcutta city banned cycling?". BBC News. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ Javorsky, Nicole (24 April 2019). "How an Ancestor of the Bicycle Relates to Climate Resilience". Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "200 years since the father of the bicycle Baron Karl von Drais invented the 'running machine' | Cycling UK".

- ^ "Karl von Drais "Father of Bicycles"". YouTube. 17 November 2021.

- ^ "DPMA | World Day of the Bicycle".

- ^ "Karl Drais and the Mechanical Horse | SciHi Blog". 29 April 2018.

- ^ Scally, Derek (10 June 2017). "World's first bicycle ride took place 200 years ago". The Irish Times. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "Frames & Materials". Science of Cycling. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Gliemann, Jennifer (21 March 2017). "200th anniversary: How the bicycle changed society". Bike Citizens. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ Limebeer, D. J. N.; Massaro, Matteo (2018). Dynamics and Optimal Control of Road Vehicles. Oxford University Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 9780192559814.

- ^ a b "Baron von Drais' Bicycle". Canada Science and Technology Museum. Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- ^ Herlihy 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Herlihy 2004, pp. 66–67.

- ^ "Is dangerous cycling a problem?". BBC News. 13 April 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Bulletin des lois de la République française (1873) 12th series, vol. 6, p. 648, patent no. 86,705: "Perfectionnements dans les roues de vélocipèdes" ("Improvements in the wheels of bicycles"), issued 4 August 1869.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 50.

- ^ McGrory, David. A History of Coventry (Chichester: Phillimore, 2003), p. 221.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 47.

- ^ McGrory, p. 222.

- ^ "Cycle market: Moving into the fast lane". The Independent. London. 26 February 2018.

- ^ Hume, William (1938). The Golden Book of Cycling. Archive maintained by 'The Pedal Club'. Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Dunlop, What sets Dunlop apart, History, 1889". Archived from the original on 2 April 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "One-Speed Bicycle Coaster Brakes". Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

Coaster brakes were invented in the 1890s.

- ^ "On Your Bike..." BBC. 26 February 2018.

- ^ "Honda|SUPER CUB FANSITE|スーパーカブファンのためのポータルサイト". Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Squatriglia, Chuck (23 May 2008). "Honda Sells Its 60 Millionth – Yes, Millionth – Super Cub". Wired. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ American Motorcyclist Association (May 2006). "That's 2.5 billion cc!". American Motorcyclist. Westerville, OH. p. 24. ISSN 0277-9358. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ^ "Toyota ponders recall of world's best-selling car". Australian Broadcasting Corporation News Online. 18 February 2010.

- ^ 24/7 Wall St. (26 January 2012). "The Best-Selling Cars of All Time". Fox Business. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016.

- ^ Fishman, Elliot (2 January 2016). "Cycling as transport". Transport Reviews. 36 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/01441647.2015.1114271. ISSN 0144-1647.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian; Kindy, David. "The Black Buffalo Soldiers Who Biked Across the American West". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Game changers | 12 innovations that changed road cycling". BikeRadar. 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Various (9 December 2006). "Like falling off". New Scientist (2581): 93. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^ Meijaard, J.P.; Papadopoulos, Jim M.; Ruina, Andy; Schwab, A.L. (2007). "Linearized dynamics equations for the balance and steer of a bicycle: a benchmark and review". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 463 (2084): 1955–82. Bibcode:2007RSPSA.463.1955M. doi:10.1098/rspa.2007.1857. ISSN 1364-5021. S2CID 18309860.

- ^ Wilson, David Gordon; Jim Papadopoulos (2004). Bicycling Science (Third ed.). The MIT Press. pp. 270–72. ISBN 978-0-262-73154-6.

- ^ Fajans, Joel (July 1738). "Steering in bicycles and motorcycles" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 68 (7): 654–59. Bibcode:2000AmJPh..68..654F. doi:10.1119/1.19504. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

- ^ Cossalter, Vittore (2006). Motorcycle Dynamics (Second ed.). Lulu. pp. 241–342. ISBN 978-1-4303-0861-4.

- ^ S.S. Wilson, "Bicycle Technology", Scientific American, March 1973

- ^ "Pedal power probe shows bicycles waste little energy". Johns Hopkins Gazette. 30 August 1999.

- ^ Whitt, Frank R.; David G. Wilson (1982). Bicycling Science (Second ed.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. pp. 277–300. ISBN 978-0-262-23111-4.

- ^ "AeroVelo Eta: bullet-shaped bike sets new human-powered speed record". International Business Times. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "How Much Do Bicycles Pollute? Looking at the Carbon Dioxide Produced by Bicycles". Kenkifer.com. 20 November 1999. Archived from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Cyclist, Average Joe (10 April 2017). "How the Bicycle Became a Symbol for Women's Emancipation". Average Joe Cyclist. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "History Loudly Tells Why The Recumbent Bike Is Popular Today". Recumbent-bikes-truth-for-you.com. 1 April 1934. Archived from the original on 2 August 2003. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Lakkad; Patel (June 1981). "Mechanical properties of bamboo, a natural composite". Fibre Science and Technology. 14 (4): 319–22. doi:10.1016/0015-0568(81)90023-3.

- ^ a b Jen Lukenbill. "About My Planet: Bamboo Bikes". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Teo Kermeliotis (31 May 2012). "Made in Africa: Bamboo bikes put Zambian business on right track". CNN.

- ^ Bamboo bicycles made in Zambia (TV news). Tokyo: NHK World News in English. 14 January 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013.

- ^ Patterson, J.M.; Jaggars, M.M.; Boyer, M.I. (2003). "Ulnar and median nerve palsy in long-distance cyclists. A prospective study". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 31 (4): 585–89. doi:10.1177/03635465030310041801. PMID 12860549. S2CID 22497516.

- ^ Wade Wallace (1 October 2013). "Disc Brakes and Road Bikes: What does the Future Hold?". cyclingtips.com.au. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ John Allan. "Disc Brakes". sheldonbrown.com. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ Brown, Sheldon. "Fixed Gear Conversions: Braking". Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ a b Bluejay, Michael. "Safety Accessories". Bicycle Accessories. BicycleUniverse.info. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- ^ Kicinski-Mccoy, James (3 August 2015). "The Coolest Bike Accessories For Kids". MOTHER. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Blommenstein, Biko; Kamp, John (2022). "Mastering balance: The use of balance bicycles promotes the development of independent cycling". British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 40 (2): 242–253. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12409. ISSN 0261-510X. PMC 9310799. PMID 35262200.

- ^ Mercê, Cristiana; Branco, Marco; Catela, David; Lopes, Frederico; Cordovil, Rita (2022). "Learning to cycle: From training wheels to balance bike". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 19 (3): 1814. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031814. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8834827. PMID 35162834.

- ^ Clarke, Colin; Gillham, Chris (November 2019). "Effects of bicycle helmet wearing on accident and injury rates". Researchgate.

- ^ Bachynski, Kathleen; Bateman-House, Alison (2020). "Mandatory Bicycle Helmet Laws in the United States: Origins, Context, and Controversies". American Journal of Public Health. 110 (8): 1198–1204. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305718. PMC 7349454. PMID 32552017.

- ^ "The Essentials of Bike Clothing". About Bicycling. About.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- ^ "Bicycle Advisor". bicycleadvisor.com. 2 May 2015. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Community Bicycle Organizations". Bike Collective Network wiki. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ^ Van Mead, Nick (3 May 2016). "Cycling: how to fix a puncture (even if you don't have the right tools)". theguardian.com. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ "Sheldon Brown: Flat tires". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ^ "BikeWebSite: Bicycle Glossary – Patch kit". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2008.

- ^ "How bicycles transformed our world". National Geographic. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2024.

- ^ Stoffers, Manuel (2022). "Chapter Two - The bicycle: Technology and culture". Advances in Transport Policy and Planning. 10: 7–26. doi:10.1016/bs.atpp.2022.04.002.

- ^ Winters, M; Brauer, M; Setton, EM; Teschke, K (2010). "Built environment influences on healthy transportation choices: bicycling versus driving". J Urban Health. 87 (6): 969–93. doi:10.1007/s11524-010-9509-6. PMC 3005092. PMID 21174189.

- ^ Shaheen, Susan; Guzman, Stacey; Zhang, Hua (2010). "Bikesharing in Europe, the Americas, and Asia". Transportation Research Record. 2143: 159–67. doi:10.3141/2143-20. S2CID 40770008.

- ^ Shaheen, Stacey; Stacey Guzman (2011). "Worldwide Bikesharing". Access Magazine. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012.

- ^ Shaheen, Susan; Zhang, Hua; Martin, Elliot; Guzman, Stacey (2011). "China's Hangzhou Public Bicycle" (PDF). Transportation Research Record. 2247: 33–41. doi:10.3141/2247-05. S2CID 111120290.

- ^ "Tax free bikes for work through the Government's Green Transport Initiative". Cyclescheme.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ Broekaert, Joel & Kist, Reinier (12 February 2010). "So many bikes, so little space". NRC Handelsblad. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2010.

- ^ Damien Newton (16 October 2008). "Metro Making Room for Bikes on Their Trains". LA.StreetsBlog.Org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Bernstein, Andrea, "Techies on the cutting edge... of bike commuting", Marketplace, 22 February 2012. "Bernstein reports from the Transportation Nation project at WNYC". Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev (24 October 2013). "In Almost Every European Country, Bikes Are Outselling New Cars". NPR.

- ^ Lowe, Marcia D. (1989). The Bicycle: Vehicle for a Small Planet. Worldwatch Institute. ISBN 978-0-916468-91-0.[page needed]

- ^ Annie Lowrey (30 April 2013). "Is It Crazy to Think We Can Eradicate Poverty?". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Nicholas D. Kristof (12 April 2010). "A Bike for Abel". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ Fred P. Hochberg (5 January 2002). "Practical Help for Afghans". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "Our Impact". Bicycles Against Poverty. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-07.

- ^ a b "Bicycle: The Unnoticed Potential". BicyclePotential.org. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ^ "How can the bicycle assist in poverty eradication and social development in Africa?" (PDF). International Bicycle Fund. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2014. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ "Pedal Powered Hope Project (PPHP)". Bikes Without Borders. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ Niklas Sieber (1998). "Appropriate Transportation and Rural Development in Makete District, Tanzania" (PDF). Journal of Transport Geography. 6 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1016/S0966-6923(97)00040-9. Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- ^ "Project Tsunami Report Confirms The Power of Bicycle" (PDF). World Bicycle Relief. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c Willard, Frances Elizabeth (1895). A Wheel Within a Wheel: How I Learned to Ride the Bicycle, with Some Reflections by the Way. Woman's Temperance Publishing Association. pp. 53, 56.

- ^ Roberts, Jacob (2017). "Women's work". Distillations. 3 (1): 6–11. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Husted Harper, Ida (1898). The life and work of Susan B. Anthony: including public addresses, her own letters and many from her contemporaries during fifty years. A story of the evolution of the status of woman. Vol. 2. The Bowen-Merrill Company.

- ^ "6 Questions for Women's Bicycling Pioneer Georgena Terry". Velojoy. 4 July 2012. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ^ "Wilbur Wright Working in the Bicycle Shop". World Digital Library. 1897. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Norcliffe 2001, p. 23.

- ^ a b Norcliffe 2001, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Norcliffe 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 142–47.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 145.

- ^ Babaian, Sharon. The Most Benevolent Machine: A Historical Assessment of Cycles in Canada (Ottawa: National Museum of Science and Technology, 1998), p. 97.

- ^ Babaian, p. 98.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 147–48.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 208.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 243–45.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 121.

- ^ a b Norcliffe 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 214.

- ^ a b Norcliffe 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 30.

- ^ a b Norcliffe 2001, p. 125.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 125–26.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 238.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Norcliffe 2001, pp. 214–15.

- ^ "The Wrights' bicycle shop". 2007. Archived from the original on 25 January 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Francois Bougo (26 May 2010). "Beijing looks to revitalise bicycle culture". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010.

- ^ The Economist, 15 February 2003

- ^ "Italian bicycle sales 'surpass those of cars'". BBC News. 2 October 2012.

- ^ Illich, I. (1974). Energy and equity. New York, Harper & Row.

- ^ "Global cyclists say NO to carbon – opt for CDM" Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The World Bank, 27 October 2015

- ^ "High Growth and Big Margins in the $61 Billion Bicycle Industry". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ "The Business of Bicycles | Manufacturing | Opportunities". DARE. 1 June 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ a b "2014 European Bicycle Industry & Market Profile". Confederation of the European Bicycle Industry. 2015.

- ^ United Nations (8 November 1968). "General Provisions". Convention on Road Traffic (PDF). United Nations Conference on Road Traffic. Vienna. p. 69.

- ^ "Rules of the road for bicycles". www.progressive.com. 17 April 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Arthurs-Brennan, Michelle (22 March 2019). "What can cyclist legally do, and not do, in Europe?". cyclingweekly.com. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Vienna Convention on Road Traffic, Chapter XI Transport and Communications, B. Road Traffic, 19. Convention on Road Traffic". United Nations Treaty Collection. 8 November 1968. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Bicycle road rules : VicRoads". Home Page. 1 July 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Accessoires obligatoires à vélo". Service-public.fr (in French). 16 August 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ "Want Safer Streets for Cyclists? Ditch the Helmet Laws". Bloomberg.com. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Van Lierop, Dea; Grimsrud, Michael; El-Geneidy, Ahmed (2014). "Breaking into Bicycle Theft: Insights from Montreal, Canada". International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 9 (7): 490–501. Bibcode:2015IJSTr...9..490V. doi:10.1080/15568318.2013.811332. S2CID 44047626.

- ^ "About Bicycle Theft". bicyclelaw.com. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ^ van Lierop Grimsrud El-Geneidy (2015). "Breaking into bicycle theft: Insights from Montreal, Canada" (PDF). International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 9 (7): 490. Bibcode:2015IJSTr...9..490V. doi:10.1080/15568318.2013.811332. S2CID 44047626. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Bike serial numbers". Retrieved 2 August 2017.

Okay, fine, so maybe there are a few bikes without serial numbers, but this is rare and typical only on hand made bikes or really old bicycles.

Sources

[edit]- General

- Herlihy, David V. (2004). Bicycle: The History. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12047-9.

- Norcliffe, Glen (2001). The Ride to Modernity: The Bicycle in Canada, 1869–1900. Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8205-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Glaskin, Max (2013). Cycling Science: How Rider and Machine Work Together. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92187-7.

External links

[edit]Bicycle

View on GrokipediaThe bicycle is a two-wheeled vehicle primarily propelled by human power via pedals driving a rear wheel through a chain or other mechanism, equipped with handlebars for steering and a saddle for the rider.[1] It includes variants with electric assistance under 750 watts, but the core design emphasizes mechanical efficiency in transferring pedaling force to motion.[1] Originating in 1817 with Karl Drais's wooden draisine—a steerable, pedal-less two-wheeler propelled by foot-pushing against the ground—the bicycle evolved rapidly through the 19th century.[2] Early models like the velocipede added pedals to the front wheel, but instability led to the "boneshaker" nickname due to iron wheels on rough roads. The pivotal advancement came in 1885 with John Kemp Starley's Rover safety bicycle, featuring two similar-sized wheels, a diamond-shaped frame, and chain-driven rear wheel for stability and control.[3] In 1888, John Boyd Dunlop's pneumatic tire further improved ride comfort and efficiency by cushioning impacts and reducing rolling resistance.[4] Bicycles transformed personal mobility, enabling affordable transport independent of horses or railroads, and fostering urban commuting, recreation, and sports like road racing and touring.[5] Their defining characteristic is exceptional energy efficiency: a cyclist can sustain speeds of 15-20 km/h (9-12 mph) using about one-fifth the caloric energy per distance compared to walking, outperforming other human or animal locomotion in converting metabolic energy to distance traveled.[6] This efficiency, combined with low material and maintenance costs, sustains bicycles' global use exceeding one billion units, though vulnerabilities to theft, weather, and traffic integration pose ongoing challenges.[6]

Etymology and Definition

Etymology

The term bicycle derives from the French bicyclette, coined in the 1860s to describe a two-wheeled vehicle with a mechanical drive, combining the prefix bi- (from Greek bi-, meaning "two") with cycle (from Greek kyklos, meaning "circle" or "wheel," Latinized as cyclus).[7] [8] The word first appeared in English print in 1868, supplanting earlier terms for similar devices.[7] Preceding nomenclature included velocipede, a French term from the early 19th century meaning "swift foot," derived from Latin velox ("swift") and pes ("foot"), initially applied to foot-propelled two- or three-wheeled vehicles like the 1817 Laufmaschine.[9] This term persisted into the 1860s for pedal-driven models before bicycle gained prevalence around 1869.[10] The draisine, named after German inventor Karl Drais who patented his Laufmaschine in 1817–1818, directly references the baron and marked an early shift toward eponymous naming for two-wheeled walkers. Regional variations emerged, such as the British penny-farthing (coined around 1887), alluding to the size disparity between the large front wheel (like a penny coin) and small rear wheel (like a farthing coin), serving as a retronym for high-wheel "ordinary" bicycles of the 1870s–1880s.[11] These inventor-influenced and descriptive terms standardized around bicycle by the late 19th century, reflecting the device's evolution from pedestrian aids to propelled vehicles.[7]Definition and Types

A bicycle is a vehicle consisting of two wheels attached to a frame, one behind the other, propelled primarily by pedals driving a chain to the rear wheel, intended for human operation on the ground.[12] This design excludes unicycles, which have a single wheel, and tricycles or quadracycles, which have three or more wheels.[12] Stability during motion arises mainly from the fork's geometry creating positive trail—typically 40-60 mm—which causes the front wheel to self-steer into leans, restoring balance without rider intervention at speeds above about 6 km/h, augmented by active steering and weight shifting; gyroscopic precession from wheel rotation plays a secondary role, insufficient alone for upright travel.[13][14] Standard bicycles support a maximum total system weight of 125-136 kg, encompassing rider, bicycle, and cargo, with frames and components tested to withstand dynamic loads exceeding this under ISO protocols.[15][16] Bicycles are categorized by design features such as frame geometry, wheel diameter, tire width, and handlebar type, tailored to specific terrains and purposes. Road bicycles prioritize aerodynamics and efficiency on smooth pavement, employing drop handlebars for multiple riding positions, lightweight frames often under 8 kg, and narrow tires (23-28 mm) on 700c wheels to minimize rolling resistance.[17] Mountain bicycles feature robust frames, wide tires (2-3 inches) for traction on rough trails, front or full suspension travel of 100-200 mm, and flat handlebars, with wheel sizes of 27.5 or 29 inches to handle obstacles.[17] Hybrid bicycles combine upright postures from flat handlebars with road-bike wheel sizes (700c) and moderate tire widths (28-38 mm), suiting mixed urban and light off-road use via versatile gearing.[17] Folding bicycles incorporate hinged frames and small wheels (16-20 inches) for compact storage, often with smaller gears suited to city commuting despite reduced efficiency from higher rolling resistance.[17] Recumbent bicycles position the rider in a reclined seat behind the pedals, lowering the center of gravity for enhanced stability and reduced wind resistance, though they sacrifice visibility and maneuverability in traffic; undercranked or long-wheelbase variants achieve speeds comparable to upright bikes on flats.[17]

Electric bicycles (e-bikes) integrate a battery-powered motor providing pedal-assist up to regulatory limits, classified separately from pure human-powered models but retaining core bicycle mechanics. In the European Union, e-bikes (pedelecs) limit assistance to 250 W and 25 km/h, requiring pedaling for activation without throttle beyond 6 km/h startup aid.[18] In the United States, Class 1 e-bikes offer pedal-assist up to 20 mph (32 km/h) with motors under 750 W, Class 2 adds throttle to the same speed, and Class 3 extends pedal-assist to 28 mph (45 km/h), all mandating functional pedals and excluding full-motor operation.[19] These distinctions ensure e-bikes function as assisted pedal cycles rather than motorized vehicles, with total weight limits often increased to 150-200 kg to accommodate batteries.[20]

History

Precursors and Early Concepts