Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

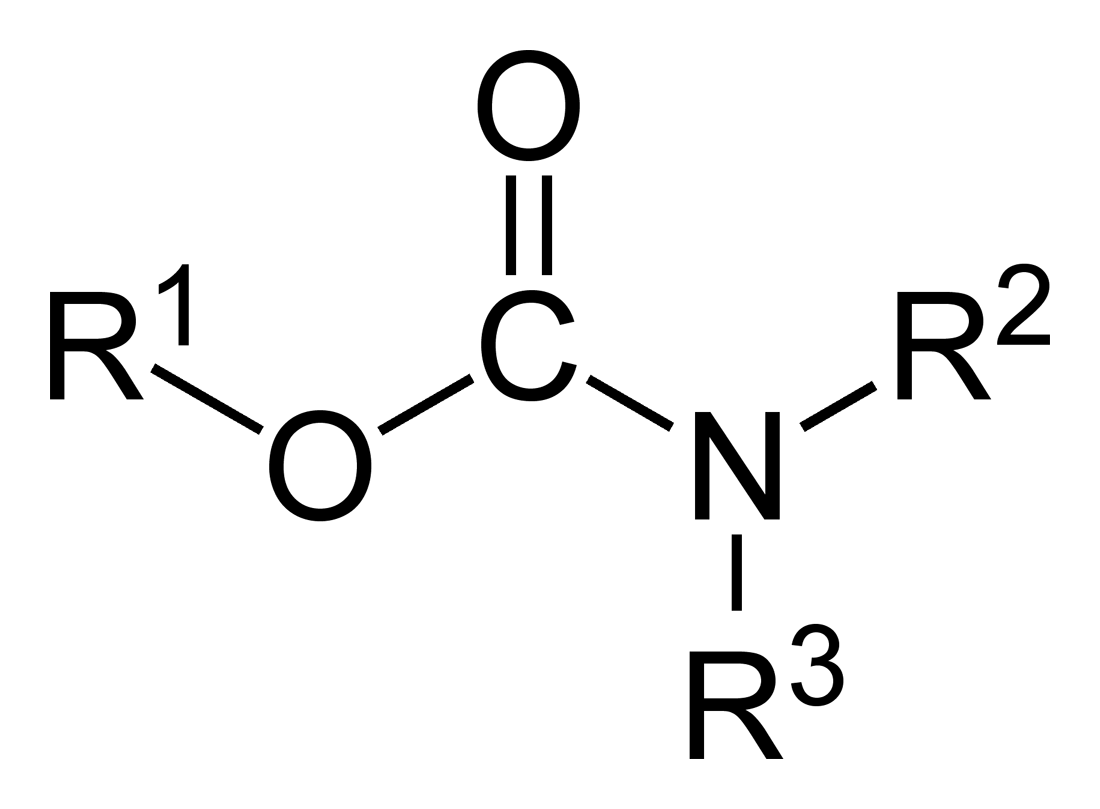

Carbamate

View on Wikipedia

In organic chemistry, a carbamate is a category of organic compounds with the general formula R2NC(O)OR and structure >N−C(=O)−O−, which are formally derived from carbamic acid (NH2COOH). The term includes organic compounds (e.g., the ester ethyl carbamate), formally obtained by replacing one or more of the hydrogen atoms by other organic functional groups; as well as salts with the carbamate anion H2NCOO− (e.g. ammonium carbamate).[1]

Polymers whose repeat units are joined by carbamate like groups −NH−C(=O)−O− are an important family of plastics, the polyurethanes. See § Etymology for clarification.

Properties

[edit]While carbamic acids are unstable, many carbamate esters and salts are stable and well known.[2]

Equilibrium with carbonate and bicarbonate

[edit]In water solutions, the carbamate anion slowly equilibrates with the ammonium NH+

4 cation and the carbonate CO2−

3 or bicarbonate HCO−

3 anions:[3][4][5]

- H2NCO−2 + 2 H2O ⇌ NH+4 + HCO−3 + OH−

- H2NCO−2 + H2O ⇌ NH+4 + CO2−3

Calcium carbamate is soluble in water, whereas calcium carbonate is not. Adding a calcium salt to an ammonium carbamate/carbonate solution will precipitate some calcium carbonate immediately, and then slowly precipitate more as the carbamate hydrolyzes.[3]

Synthesis

[edit]Carbamate salts

[edit]The salt ammonium carbamate is generated by treatment of ammonia with carbon dioxide:[6]

- 2 NH3 + CO2 → NH4[H2NCO2]

Carbamate esters

[edit]Carbamate esters also arise via alcoholysis of carbamoyl chlorides:[1]

- R2NC(O)Cl + R'OH → R2NCO2R' + HCl

Alternatively, carbamates can be formed from chloroformates and amines:[7]

- R'OC(O)Cl + R2NH → R2NCO2R' + HCl

Carbamates may be formed from the Curtius rearrangement, where isocyanates formed are reacted with an alcohol.[7]

- RCON3 → RNCO + N2

- RNCO + R′OH → RNHCO2R′

Natural occurrence

[edit]Within nature carbon dioxide can bind with neutral amine groups to form a carbamate, this post-translational modification is known as carbamylation. This modification is known to occur on several important proteins; see examples below.[8]

Hemoglobin

[edit]The N-terminal amino groups of valine residues in the α- and β-chains of deoxyhemoglobin exist as carbamates. They help to stabilise the protein when it becomes deoxyhemoglobin, and increases the likelihood of the release of remaining oxygen molecules bound to the protein. This stabilizing effect should not be confused with the Bohr effect (an indirect effect caused by carbon dioxide).[9]

Urease and phosphotriesterase

[edit]The ε-amino groups of the lysine residues in urease and phosphotriesterase also feature carbamate. The carbamate derived from aminoimidazole is an intermediate in the biosynthesis of inosine. Carbamoyl phosphate is generated from carboxyphosphate rather than CO2.[10]

CO2 capture by ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase

[edit]Perhaps the most prevalent carbamate is the one involved in the capture of CO2 by plants. This process is necessary for their growth. The enzyme ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) fixes a molecule of carbon dioxide as phosphoglycerate in the Calvin cycle. At the active site of the enzyme, a Mg2+ ion is bound to glutamate and aspartate residues as well as a lysine carbamate. The carbamate is formed when an uncharged lysine side chain near the ion reacts with a carbon dioxide molecule from the air (not the substrate carbon dioxide molecule), which then renders it charged, and, therefore, able to bind the Mg2+ ion.[11]

Applications

[edit]Synthesis of urea

[edit]Although not usually isolated as such, the salt ammonium carbamate is produced on a large scale as an intermediate in the production of the commodity chemical urea from ammonia and carbon dioxide.[1]

Polyurethane plastics

[edit]Polyurethanes contain multiple carbamate groups as part of their structure. The "urethane" in the name "polyurethane" refers to these carbamate groups; the term "urethane links" describe how carbamates polymerize. In contrast, the substance commonly called "urethane", ethyl carbamate, is neither a component of polyurethanes, nor is it used in their manufacture. Urethanes are usually formed by reaction of an alcohol with an isocyanate. Commonly, urethanes made by a non-isocyanate route are called carbamates.[citation needed]

Polyurethane polymers have a wide range of properties and are commercially available as foams, elastomers, and solids. Typically, polyurethane polymers are made by combining diisocyanates, e.g. toluene diisocyanate, and diols, where the carbamate groups are formed by reaction of the alcohols with the isocyanates:[12]

- RN=C=O + R′OH → RNHC(O)OR′

Carbamate insecticides

[edit]

The so-called carbamate insecticides feature the carbamate ester functional group. Included in this group are aldicarb (Temik), carbofuran (Furadan), carbaryl (Sevin), ethienocarb, fenobucarb, oxamyl, and methomyl. These insecticides kill insects by reversibly inactivating the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE inhibition)[13] (IRAC mode of action 1a).[14] The organophosphate pesticides also inhibit this enzyme, although irreversibly, and cause a more severe form of cholinergic poisoning[15] (the similar IRAC MoA 1b).[14]

Fenoxycarb has a carbamate group but acts as a juvenile hormone mimic, rather than inactivating acetylcholinesterase.[16]

The insect repellent icaridin is a substituted carbamate.[17]

Besides their common use as arthropodocides/insecticides, they are also nematicidal.[18] One such is Oxamyl.[18]

Sales have declined dramatically over recent decades.[18]

Resistance

[edit]Among insecticide resistance mutations in esterases, carbamate resistance most commonly involves acetylcholinesterase (AChE) desensitization, while organophosphate resistance most commonly is carboxylesterase metabolization.[19]

Carbamate nerve agents

[edit]While the carbamate acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are commonly referred to as "carbamate insecticides" due to their generally high selectivity for insect acetylcholinesterase enzymes over the mammalian versions, the most potent compounds such as aldicarb and carbofuran are still capable of inhibiting mammalian acetylcholinesterase enzymes at low enough concentrations that they pose a significant risk of poisoning to humans, especially when used in large amounts for agricultural applications. Other carbamate based acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are known with even higher toxicity to humans, and some such as T-1123 and EA-3990 were investigated for potential military use as nerve agents. However, since all compounds of this type have a quaternary ammonium group with a permanent positive charge, they have poor blood–brain barrier penetration, and also are only stable as crystalline salts or aqueous solutions, and so were not considered to have suitable properties for weaponisation.[20][21]

Preservatives and cosmetics

[edit]Iodopropynyl butylcarbamate is a wood and paint preservative and used in cosmetics.[22]

Chemical research

[edit]Some of the most common amine protecting groups, such as Boc,[23] Fmoc,[24] benzyl chloroformate[25] and trichloroethyl chloroformate[26] are carbamates.

Medicine

[edit]Ethyl carbamate

[edit]Urethane (ethyl carbamate) was once produced commercially in the United States as a chemotherapy agent and for other medicinal purposes. It was found to be toxic and largely ineffective.[27] It is occasionally used in veterinary medicine in combination with other drugs to produce anesthesia.[28]

Carbamate derivatives

[edit]Some carbamate derivatives are used in human pharmacotherapy:

- The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor chemical class includes neostigmine and rivastigmine, both of which have a chemical structure based on the natural alkaloid physostigmine.[citation needed]

- The tranquilizer, sedative-hypnotic, and muscle relaxant, meprobamate (branded Miltown) was commonly prescribed from the 1950s through the 1970s.[29][failed verification]

- Soma (carisoprodol) is a CNS depressant and a prodrug of meprobamate; initially acting primarily as a mildy-sedating muscle relaxant and muscle pain reliever; after 2-3 hours, 20-30% of initial dose converts into active metabolite meprobamate, synergistically working together to potentiate, or add on to/increase, the existing sedation and muscle relaxation and analgesia.[citation needed]

- Valmid or Valamin was a carbamate derivative chemically named ethinamate. It was withdrawn from the market in the U.S. and Netherlands around 1990.[30]

- The protease inhibitor darunavir for HIV treatment also contains a carbamate functional group.[31]

- Ephedroxane, an aminorex analogue used as a stimulant, also falls into the carbamate category.[32]

Toxicity

[edit]Besides inhibiting human acetylcholinesterase[33] (although to a lesser degree than the insect enzyme), carbamate insecticides also target human melatonin receptors.[34] The human health effects of carbamates are well documented in the list of known endocrine disruptor compounds.[35] Clinical effects of carbamate exposure can vary from slightly toxic to highly toxic depending on a variety of factors including such as dose and route of exposure with ingestion and inhalation resulting in the most rapid clinical effects.[35] These clinical manifestations of carbamate intoxication are muscarinic signs, nicotinic signs, and in rare cases central nervous system signs.[35]

Sulfur analogues

[edit]There are two oxygen atoms in a carbamate (1), ROC(=O)NR2, and either or both of them can be conceptually replaced by sulfur. Analogues of carbamates with only one of the oxygens replaced by sulfur are called thiocarbamates (2 and 3). Carbamates with both oxygens replaced by sulfur are called dithiocarbamates (4), RSC(=S)NR2.[36]

There are two different structurally isomeric types of thiocarbamate:

- O-thiocarbamates (2), ROC(=S)NR2, where the carbonyl group (C=O) is replaced with a thiocarbonyl group (C=S)[37]

- S-thiocarbamates (3), RSC(=O)NR2, where the R–O– group is replaced with an R–S– group[37]

O-thiocarbamates can isomerise to S-thiocarbamates, for example in the Newman–Kwart rearrangement.[38]

Etymology

[edit]The etymology of the words "urethane" and "carbamate" are highly similar but not the same. The word "urethane" was first coined in 1833 by French chemist Jean-Baptiste Dumas.[39][40] Dumas states "Urethane. The new ether, brought into contact with liquid and concentrated ammonia, exerts on this substance a reaction so strong that the mixture boils, and sometimes even produces a sort of explosion. If the ammonia is in excess, all the ether disappears. It forms ammonium hydrochlorate and a new substance endowed with interesting properties."[40] Dumas appears to be naming this compound urethane. However, later Dumas states "While waiting for opinion to settle on the nature of this body, I propose to designate by the names of urethane and oxamethane the two materials which I have just studied, and which I regard as types of a new family, among nitrogenous substances. These names which, in my eyes, do not prejudge anything in the question of alcohol and ethers, will at least have the advantage of satisfying chemists who still refuse to accept our theory."[40] The word urethane is derived from the words "urea" and "ether" with the suffix "-ane" as a generic chemical suffix, making it specific for the R2NC(=O)OR' (R' not = H) bonding structure.[41]

The use of the word "carbamate" appears to come later only being traced back to at least 1849, in a description of Dumas's work by Henry Medlock.[42] Medlock states "It is well known that the action of ammonia on chloro-carbonate (phosgene) of ethyl gives rise to the formation of the substance which Dumas, the discoverer, called urethane, and which we are now in the habit of considering as the ether of carbamic acid."[42] This suggests that instead of continuing with the urethane family naming convention Dumas coined, they altered the naming convention to ethyl ether of carbamic acid. Carbamate is derived from the words "carbamide", otherwise known as urea, and "-ate" a suffix which indicates the salt or ester of an acid.[43][44]

Both words have roots deriving from urea. Carbamate is less-specific because the -ate suffix is ambiguous for either the salt or ester of a carbamic acid. However, the -ate suffix is also more specific because it suggests carbamates must be derived from the acid of carbamate, or carbamic acids. Although, a urethane has the same chemical structure as a carbamate ester moiety, a urethane not derived from a carbamic acid is not a carbamate ester. In other words, any synthesis of the R2NC(=O)OR' (R' not = H) moiety that does not derive from carbamic acids is not a carbamate ester but instead a urethane. Furthermore, carbamate esters are urethanes but not all urethanes are carbamate esters. This further suggests that polyurethanes are not simply polycarbamate-esters because polyurethanes are not typically synthesized using carbamic acids.

IUPAC states "The esters are often called urethanes or urethans, a usage that is strictly correct only for the ethyl esters."[45] But also states, "An alternative term for the compounds R2NC(=O)OR' (R' not = H), esters of carbamic acids, R,NC(=O)OH, in strict use limited to the ethyl esters, but widely used in the general sense".[46] IUPAC provides these statements without citation.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jäger, Peter; Rentzea, Costin N.; Kieczka, Heinz (2000). "Carbamates and Carbamoyl Chlorides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a05_051. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Ghosh, Arun K.; Brindisi, Margherita (2015-04-09). "Organic Carbamates in Drug Design and Medicinal Chemistry". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 58 (7): 2895–2940. doi:10.1021/jm501371s. ISSN 0022-2623. PMC 4393377. PMID 25565044.

- ^ a b Burrows, George H.; Lewis, Gilbert N. (1912). "The equilibrium between ammonium carbonate and ammonium carbamate in aqueous solution at 25°". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 34 (8): 993–995. Bibcode:1912JAChS..34..993B. doi:10.1021/ja02209a003.

- ^ Clark, K. G.; Gaddy, V. L.; Rist, C. E. (1933). "Equilibria in the Ammonium Carbamate-Urea-Water System". Ind. Eng. Chem. 25 (10): 1092–1096. doi:10.1021/ie50286a008.

- ^ Mani, Fabrizio; Peruzzini, Maurizio; Stoppioni, Piero (2006). "CO2 absorption by aqueous NH

3 solutions: speciation of ammonium carbamate, bicarbonate and carbonate by a 13

C NMR study". Green Chemistry. 8 (11). Royal Society of Chemistry: 995. doi:10.1039/b602051h. ISSN 1463-9262. - ^ Brooks, L. A.; Audrieta, L. F.; Bluestone, H.; Jofinsox, W. C. (1946). "Ammonium Carbamate". Inorganic Syntheses. Vol. 2. pp. 85–86. doi:10.1002/9780470132333.ch23. ISBN 978-0-470-13233-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ a b Chaturvedi, Devdutt (1 May 2011). "Recent Developments on the Carbamation of Amines". Current Organic Chemistry. 15 (10). Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.: 1593–1624. doi:10.2174/138527211795378173. ISSN 1385-2728.

- ^ Linthwaite, Victoria L.; Janus, Joanna M.; Brown, Adrian P.; Wong-Pascua, David; O'Donoghue, AnnMarie C.; Porter, Andrew; Treumann, Achim; Hodgson, David R. W.; Cann, Martin J. (2018-08-06). "The identification of carbon dioxide mediated protein post-translational modifications". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3092. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3092L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05475-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6078960. PMID 30082797.

- ^ Ferguson, J. K. W.; Roughton, F. J. W. (1934-12-14). "The direct chemical estimation of carbamino compounds of CO2 with hæmoglobin". The Journal of Physiology. 83 (1): 68–86. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1934.sp003212. ISSN 0022-3751. PMC 1394306. PMID 16994615.

- ^ Bartoschek, S.; Vorholt, J. A.; Thauer, R. K.; Geierstanger, B. H.; Griesinger, C. (2001). "N-Carboxymethanofuran (carbamate) formation from methanofuran and CO2 in methanogenic archaea: Thermodynamics and kinetics of the spontaneous reaction". Eur. J. Biochem. 267 (11): 3130–3138. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01331.x. PMID 10824097.

- ^ T, Lundqvist; G, Schneider (1991-01-29). "Crystal Structure of the Ternary Complex of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate Carboxylase, Mg(II), and Activator CO2 at 2.3-A Resolution". Biochemistry. 30 (4): 904–8. doi:10.1021/bi00218a004. PMID 1899197.

- ^ Adam, Norbert; Avar, Geza; Blankenheim, Herbert; Friederichs, Wolfgang; Giersig, Manfred; Weigand, Eckehard; Halfmann, Michael; Wittbecker, Friedrich-Wilhelm; Larimer, Donald-Richard; Maier, Udo; Meyer-Ahrens, Sven; Noble, Karl-Ludwig; Wussow, Hans-Georg (2005). "Polyurethanes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_665.pub3. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Fukuto, T. R. (1990). "Mechanism of action of organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides". Environmental Health Perspectives. 87: 245–254. Bibcode:1990EnvHP..87..245F. doi:10.1289/ehp.9087245. PMC 1567830. PMID 2176588.

- ^ a b "IRAC Mode of Action Classification Scheme Version 9.4" (pdf). Insecticide Resistance Action Committee. March 2020.

- ^ Metcalf, Robert L. "Insect Control". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_263. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ "Pesticide Information Project: Fenoxycarb". Cornell University. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information. "PubChem Compound Summary for CID 125098, Icaridin". Pubchem. Retrieved 2024-01-08.

- ^ a b c Sparks, Thomas; Crossthwaite, Andrew; Nauen, Ralf; Banba, Shinichi; Cordova, Daniel; Earley, Fergus; Ebbinghaus-Kintscher, Ulrich; Fujioka, Shinsuke; Hirao, Ayako; Karmon, Danny; Kennedy, Robert; Nakao, Toshifumi; Popham, Holly; Salgado, Vincent; Watson, Gerald; Wedel, Barbara; Wessels, Frank (2020). "Insecticides, biologics and nematicides: Updates to IRAC's mode of action classification - a tool for resistance management". Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 167 104587. Elsevier. Bibcode:2020PBioP.16704587S. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2020.104587. ISSN 0048-3575. PMID 32527435.

- ^ Oakeshott, John; Devonshire, Alan; Claudianos, Charles; Sutherland, Tara; Horne, Irene; Campbell, Peter; Ollis, David; Russell, Robyn (2005). "Comparing the organophosphorus and carbamate insecticide resistance mutations in cholin- and carboxyl-esterases". Chemico-Biological Interactions. 157–158. Elsevier BV: 269–275. Bibcode:2005CBI...157..269O. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.041. ISSN 0009-2797. PMID 16289012. S2CID 32597626.

- ^ Gupta, Ramesh C, ed. (2015). Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents. Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States: Academic Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0-12-800494-4.

- ^ Ellison, D (2008). Handbook of chemical and biological warfare agents. Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-1434-6. OCLC 82473582.

- ^ Badreshia, S. (2002). "Iodopropynyl butylcarbamate". Am. J. Contact Dermat. 13 (2): 77–79. doi:10.1053/ajcd.2002.30728. ISSN 1046-199X. PMID 12022126.

- ^ Vommina V. Sureshbabu; Narasimhamurthy Narendra (2011). "Protection Reactions". In Andrew B. Hughes (ed.). Protection Reactions, Medicinal Chemistry, Combinatorial Synthesis. Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry. Vol. 4. Wiley-VCH. pp. XVIII–LXXXIV. doi:10.1002/9783527631827.ch1. ISBN 9783527641574.

- ^ Wellings, Donald A.; Atherton, Eric (1997). "[4] Standard Fmoc protocols". Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 289. pp. 44–67. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(97)89043-x. ISBN 9780121821906. PMID 9353717.

- ^ Katsoyannis, P. G., ed. (1973). The Chemistry of Polypeptides. New York: Plenum Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-4571-8. ISBN 978-1-4613-4571-8. S2CID 35144893. Archived from the original on 2022-10-13. Retrieved 2021-04-01.

- ^ Marullo, N. P.; Wagener, E. H. (1969-01-01). "Structural organic chemistry by nmr. III. Isomerization of compounds containing the carbon-nitrogen double bond". Tetrahedron Letters. 10 (30): 2555–2558. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)88566-X.

- ^ Holland, J. R.; Hosley, H.; Scharlau, C.; Carbone, P. P.; Frei, E. III; Brindley, C. O.; Hall, T. C.; Shnider, B. I.; Gold, G. L.; Lasagna, L.; Owens, A. H. Jr; Miller, S. P. (1 March 1966). "A controlled trial of urethane treatment in multiple myeloma". Blood. 27 (3): 328–42. doi:10.1182/blood.V27.3.328.328. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 5933438.

- ^ The Chemical/Biological Safety Section (CBSS) of the Office of Environmental Health and Safety. "Working with Urethane" (PDF). Virginia Commonwealth University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-11.

- ^ Carbachol Multum Consumer Information. Accessed 27 April 2021.

- ^ PubChem. "Ethinamate". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2025-07-03.

- ^ DrugBank DB01264 . Accessed 27 April 2021.

- ^ Hikino H, Ogata K, Kasahara Y, Konno C (May 1985). "Pharmacology of ephedroxanes". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 13 (2): 175–191. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(85)90005-4. PMID 4021515.

- ^ Colović, MB; Krstić, DZ; Lazarević-Pašti, TD; Bondžić, AM; Vasić, VM (2013). "Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology". Curr Neuropharmacol. 11 (3): 315–35. doi:10.2174/1570159X11311030006. PMC 3648782. PMID 24179466.

- ^ Popovska-Gorevski, M; Dubocovich, ML; Rajnarayanan, RV (2017). "Carbamate Insecticides Target Human Melatonin Receptors". Chem Res Toxicol. 30 (2): 574–582. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00301. PMC 5318275. PMID 28027439.

- ^ a b c Marais, Simone; Diase, Elsa; Pereira, Maria de Lourdes (2012). "Carbamates: Human Exposure and Health Effects". The Impact of Pesticides. 21: 38 – via Research Gate.

- ^ Rüdiger Schubart (2000). "Dithiocarbamic Acid and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a09_001. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ a b Walter, W.; Bode, K.-D. (April 1967). "Syntheses of Thiocarbamates". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 6 (4): 281–293. doi:10.1002/anie.196702811.

- ^ Newman, Melvin S.; Hetzel, Frederick W. (1971). "Thiophenols from Phenols: 2-Naphthalenethiol". Org. Synth. 51: 139. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.051.0139.

- ^ A dictionary of chemistry. John Daintith (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-1-61583-965-0. OCLC 713875281.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Dumas, Jean (1833). "Recherches de chimie organique". Annales de Chimie et de Physique. 2nd series. 56: 496–556.

- ^ "urethane | Etymology, origin and meaning of urethane by etymonline". www.etymonline.com. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ a b Medlock, Henry (1849). "XXIX.—Researches on the amyl series". Q. J. Chem. Soc. 1 (4): 368–379. doi:10.1039/qj8490100368. ISSN 1743-6893.

- ^ "Definition of CARBAMATE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Divers, Edward (1870-01-01). "XXVII.—On the precipitation of solutions of ammonium carbonate, sodium carbonate, and ammonium carbamate by calcium chloride". Journal of the Chemical Society. 23: 359–364. doi:10.1039/JS8702300359. ISSN 0368-1769.

- ^ "Carbamates (C00803)". Goldbook. IUPAC. doi:10.1351/goldbook.C00803. Retrieved 2023-03-29.

- ^ Moss, G. P.; Smith, P. a. S.; Tavernier, D. (1995-01-01). "Glossary of class names of organic compounds and reactivity intermediates based on structure (IUPAC Recommendations 1995)". Pure and Applied Chemistry (in German). 67 (8–9): 1307–1375. doi:10.1351/pac199567081307. ISSN 1365-3075. S2CID 95004254.

Carbamate

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Nomenclature

Carbamates are organic compounds classified as esters or salts of carbamic acid, which has the molecular formula . The general formula for carbamates is , where the two R groups attached to the nitrogen atom may be hydrogen or hydrocarbyl substituents, and R' is typically an alkyl or aryl group for esters, or a cation (such as a metal ion) for salts. This structure derives directly from carbamic acid, where one or both hydrogens on the amino group may be replaced by organic groups, and the acidic hydrogen is substituted by an alkyl or cationic moiety.[1] Carbamic acid is inherently unstable, readily decomposing into ammonia and carbon dioxide, and computational studies indicate the neutral form is the most stable configuration, with the zwitterionic tautomer being significantly higher in energy.[7][8] Despite this instability, carbamates themselves are often stable under standard conditions, forming the basis for various derivatives. A key distinction exists between carbamate salts and esters. Salts involve the carbamate anion paired with a cation, as in ammonium carbamate , a white crystalline solid used in fertilizers. Esters, on the other hand, replace the anionic charge with an alkoxy group, yielding structures like methyl carbamate , a simple compound with applications in organic synthesis. IUPAC nomenclature for carbamates emphasizes substitutive naming rooted in the parent carbamic acid. Unsubstituted esters are designated as alkyl carbamates, such as ethyl carbamate , commonly referred to as urethane—though "urethane" strictly applies only to the ethyl derivative, with broader use for similar esters historically termed urethans. For N-substituted variants, prefixes indicate the nitrogen substituents, e.g., N-phenylcarbamic acid methyl ester for . Salts follow ionic naming conventions, combining the cation name with "carbamate," as in potassium carbamate. These rules ensure systematic identification while accommodating structural variations.[1]Historical Development and Etymology

The study of carbamates originated in the early 19th century as part of broader investigations into nitrogenous compounds and the synthesis of organic molecules from inorganic precursors. A pivotal milestone occurred in 1828 when German chemist Friedrich Wöhler reported the synthesis of urea from ammonium cyanate, marking the first laboratory production of an organic compound previously thought to require a vital force. This discovery not only challenged the prevailing theory of vitalism but also spurred research into related structures, including ammonium carbamate, which decomposes to urea and water upon heating—a reaction later utilized in industrial processes.[9] Wöhler's work revolutionized organic chemistry by establishing synthesis as a core method for exploring compound relationships and influenced subsequent research, including his later collaborations with Justus von Liebig. Further developments in the 19th century focused on the preparation and properties of ammonium carbamate, formed by the reaction of ammonia and carbon dioxide. Although the compound was recognized in chemical literature by the mid-century, the direct conversion of ammonium carbamate to urea was first demonstrated in 1870 by Bassarov through heating in sealed tubes at 130–140 °C, providing insight into the equilibrium between these species.[10] This finding built on earlier urea studies and highlighted carbamates' role in nitrogen chemistry, influencing subsequent applications in fertilizers and synthesis. The etymology of "carbamate" derives from "carbamic acid," a term first recorded in English between 1860 and 1865, combining "carb-" from carbon with "-amic" from ammonia to denote the NH₂COOH structure.[11] The nomenclature evolved to distinguish carbamates as salts or esters of this unstable acid. By the late 19th century, "carbamate" became standard in chemical terminology, reflecting the field's shift toward systematic naming influenced by figures like Jean-Baptiste Dumas.Chemical Properties

Structure and Bonding

Carbamates possess a functional group with the general formula R₂N–C(=O)–OR', where the central carbonyl carbon is bonded to a nitrogen atom and an alkoxy group, exhibiting hybrid characteristics of amides and esters. The molecular structure is stabilized by resonance delocalization involving the nitrogen lone pair and the carbonyl π-system, resulting in three primary resonance contributors: one with a C=O double bond and C–N single bond, a second with charge separation on oxygen and nitrogen, and a third emphasizing partial double bond character in the C–N linkage. This delocalization imparts partial double bond character to the C–N bond, restricting rotation and leading to rotational barriers of approximately 12–16 kcal/mol, which is 3–4 kcal/mol lower than in typical amides due to the adjacent oxygen atom's electronic and steric influences.[12] X-ray crystallographic studies of simple carbamates reveal characteristic bond lengths consistent with this resonance stabilization. For instance, in ethyl N-phenylcarbamate, the C=O bond measures approximately 1.21 Å, indicative of strong double bond character, while the C–N bond is shortened to about 1.35 Å compared to a typical single C–N bond of 1.47 Å, reflecting the partial double bond nature. Bond angles around the carbonyl carbon are typically near 120–125° for the O=C–N and O=C–O angles, approaching planarity due to the sp² hybridization and resonance effects. The carbamate group is highly polar, with the electronegative oxygen atoms in the carbonyl and alkoxy moieties creating a dipole moment that enhances solubility in polar solvents. The N–H protons (in non-tertiary carbamates) enable hydrogen bonding as donors, while the C=O serves as an acceptor, facilitating intermolecular interactions such as dimer formation or association with water or other protic species. This polarity and hydrogen-bonding capability contribute to the group's stability and role in molecular recognition.[5] Spectroscopic methods confirm these structural features. In infrared (IR) spectroscopy, the C=O stretching vibration appears as a strong absorption band around 1700 cm⁻¹, slightly higher than in amides due to reduced resonance donation from nitrogen influenced by the alkoxy group. In ¹³C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, the carbonyl carbon resonates at approximately 155–165 ppm, shifted upfield relative to esters (170–180 ppm) owing to the electron-donating nitrogen.[13][14]Equilibrium with Carbonates and Bicarbonates

Carbamate salts, formed from the reaction of amines with carbon dioxide, exist in equilibrium with carbonate and bicarbonate species in aqueous media. For primary or secondary amines (RNH₂ or R₂NH), the initial zwitterionic carbamate intermediate reacts further to form: 2 RNH₂ + CO₂ ⇌ RNH₃⁺ + RNHCOO⁻ The carbamate anion (RNHCOO⁻) is subject to hydrolysis: RNHCOO⁻ + H₂O ⇌ RNH₂ + HCO₃⁻ These equilibria determine the distribution of species in amine-based CO₂ absorption systems and influence the stability of carbamates under physiological conditions. The equilibrium constant for carbamate formation (K_carb) for monoethanolamine, for example, is approximately 4.3 at 298 K, decreasing with temperature.[15][16]Synthesis

Carbamate Salts

Carbamate salts are ionic compounds formed by the protonation of carbamic acid (NH₂COOH) or its derivatives, typically consisting of ammonium or alkylammonium cations paired with carbamate anions (NH₂COO⁻ or RNHCOO⁻). These salts are prepared through several laboratory and industrial methods, primarily involving the direct reaction of amines with carbon dioxide, which proceeds via the formation of an intermediate carbamic acid that subsequently deprotonates one amine molecule to yield the salt.[17] A primary route for synthesizing carbamate salts is the reaction of ammonia or primary/secondary amines with CO₂. For ammonia, the process involves the absorption of CO₂ into liquid ammonia, leading to the formation of ammonium carbamate via the equilibrium 2NH₃ + CO₂ ⇌ NH₄[NH₂CO₂]; this reaction is exothermic and often conducted under pressure to favor salt formation, with yields exceeding 90% in industrial settings.[18] Similarly, for alkylamines, the general reaction 2RNH₂ + CO₂ → [RNH₃][RNHCO₂] produces alkylammonium alkylcarbamates, typically carried out in anhydrous solvents or under supercritical CO₂ conditions to enhance solubility and selectivity, achieving up to 80% yields for primary aliphatic amines. These methods are distinct from ester synthesis, as they emphasize ionic product formation without alcohol involvement. Ammonium carbamate is specifically prepared by reacting gaseous CO₂ with excess ammonia, often in liquid ammonia as the medium to dissolve the reactants and precipitate the salt: NH₃ + CO₂ + NH₃ → NH₄[NH₂CO₂]. This approach is scalable for industrial use, particularly as an intermediate in urea production, where the salt is generated at 150–200 bar and 180–210°C before dehydration.[19] An alternative laboratory method involves the hydrolysis of urea under pressure, where (NH₂)₂CO + H₂O → NH₂COOH + NH₃ occurs, followed by salting out with a base to isolate the carbamate salt; this route is useful for generating ammonium carbamate in aqueous systems at elevated temperatures (around 120–150°C) and pressures (10–20 bar), with conversion efficiencies up to 70%.[20] Purification of carbamate salts typically involves recrystallization from alcohols or filtration from reaction mixtures, as they exhibit moderate solubility in water and organic solvents. These salts are thermally unstable, decomposing reversibly above approximately 50–60°C to regenerate CO₂ and the parent amine, which limits their storage to cool, dry conditions; for instance, ammonium carbamate volatilizes around 60°C with an enthalpy of decomposition of about 2000 kJ/kg.[21]Carbamate Esters

Carbamate esters, also known as urethanes, are commonly synthesized in the laboratory by the reaction of an amine with an alkyl chloroformate (ROCOCl) in the presence of a base such as pyridine or triethylamine, which facilitates the nucleophilic attack by the amine on the carbonyl carbon to form RNHC(O)OR'.[22] This method allows for the preparation of a wide variety of substituted carbamates under mild conditions, typically at room temperature in organic solvents like dichloromethane. In industrial applications, particularly for polyurethane production, carbamate esters are formed by the addition of alcohols or polyols to isocyanates (RNCO), where the alcohol acts as a nucleophile to yield the –NH–C(O)–O– linkage. This step-growth polymerization is catalyzed by bases or organometallic compounds and conducted at elevated temperatures (50–150°C) to control viscosity and reaction rate.[6] Alternative green methods have been developed to avoid toxic phosgene derivatives, including the direct carboxylation of amines with CO₂ to form carbamate salts, followed by O-alkylation with alkyl halides or dialkyl carbonates under basic conditions. For example, primary amines react with CO₂ and ethyl iodide in the presence of cesium carbonate to produce ethyl carbamates in yields up to 90%. These approaches utilize supercritical CO₂ or ionic liquids to improve efficiency and sustainability.[23]Natural Occurrence

In Hemoglobin and CO2 Transport

In the physiological process of carbon dioxide (CO₂) transport in blood, carbamates play a crucial role through their formation with hemoglobin. Carbon dioxide reacts with the N-terminal amino groups of hemoglobin's globin chains, specifically the α-amino groups of the α- and β-subunits, to form carbaminohemoglobin via the reversible reaction:This carbamate linkage occurs preferentially in deoxygenated hemoglobin, facilitating CO₂ carriage from tissues to the lungs.[24][25] Carbaminohemoglobin accounts for approximately 20-25% of the total CO₂ transported in venous blood, with the majority (about 70%) carried as bicarbonate ions and the remainder (5-7%) dissolved directly in plasma. This proportion underscores the significance of carbamate formation in efficient gas exchange, particularly under varying physiological conditions.[26][27] The formation of carbamates is influenced by blood pH and oxygenation state, with enhanced binding in acidic, deoxygenated environments typical of peripheral tissues. This pH dependence aligns with the Bohr effect, where decreased pH (from elevated CO₂ levels) reduces hemoglobin's oxygen affinity, promoting deoxygenation and thereby increasing sites available for carbamate formation to aid CO₂ loading. In the lungs, the reverse occurs: higher pH and oxygenation favor carbamate dissociation, releasing CO₂ for exhalation.[28][25] Structurally, the carbamate groups formed at the N-terminal valine residues of the globin chains contribute to stabilizing the tense (T) state of deoxyhemoglobin through additional salt bridges and electrostatic interactions, which further support the cooperative unloading of oxygen and loading of CO₂. This stabilization enhances the efficiency of respiratory gas transport without requiring enzymatic catalysis.[24][29]