Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conservation movement

View on Wikipedia| Part of the Politics Series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

The conservation movement, also known as nature conservation, is a political, environmental, and social movement that seeks to manage and protect natural resources, including animal, fungus, and plant species as well as their habitat for the future. Conservationists are concerned with leaving the environment in a better state than the condition they found it in.[1] Evidence-based conservation seeks to use high quality scientific evidence to make conservation efforts more effective.

The early conservation movement evolved out of necessity to maintain natural resources such as fisheries, wildlife management, water, soil, as well as conservation and sustainable forestry. The contemporary conservation movement has broadened from the early movement's emphasis on use of sustainable yield of natural resources and preservation of wilderness areas to include preservation of biodiversity. Some say the conservation movement is part of the broader and more far-reaching environmental movement, while others argue that they differ both in ideology and practice. Conservation is seen as differing from environmentalism and it is generally a conservative school of thought which aims to preserve natural resources expressly for their continued sustainable use by humans.[2]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

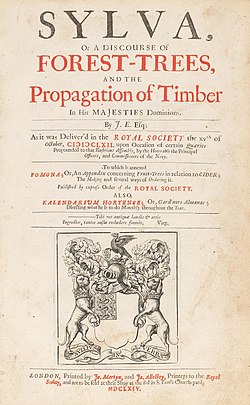

The conservation movement can be traced back to John Evelyn's work Sylva, which was presented as a paper to the Royal Society in 1662. Published as a book two years later, it was one of the most highly influential texts on forestry ever published.[3] Timber resources in England were becoming dangerously depleted at the time, and Evelyn advocated the importance of conserving the forests by managing the rate of depletion and ensuring that the cut down trees get replenished.

Khejarli massacre:

The Bishnoi narrate the story of Amrita Devi, a member of the sect who inspired as many as 363 other Bishnois to go to their deaths in protest of the cutting down of Khejri trees on 12 September 1730.[4] The Maharaja of Jodhpur, Abhay Singh, requiring wood for the construction of a new palace, sent soldiers to cut trees in the village of Khejarli, which was called Jehnad at that time. Noticing their actions, Amrita Devi hugged a tree in an attempt to stop them. Her family then adopted the same strategy, as did other local people when the news spread. She told the soldiers that she considered their actions to be an insult to her faith and that she was prepared to die to save the trees. The soldiers did indeed kill her and others until Abhay Singh was informed of what was going on and intervened to stop the massacre. Some of the 363 Bishnois who were killed protecting the trees were buried in Khejarli, where a simple grave with four pillars was erected. Every year, in September, i.e., Shukla Dashmi of Bhadrapad (Hindi month) the Bishnois assemble there to commemorate the sacrifice made by their people to preserve the trees.

The field developed during the 18th century, especially in Prussia and France where scientific forestry methods were developed. These methods were first applied rigorously in British India from the early 19th century. The government was interested in the use of forest produce and began managing the forests with measures to reduce the risk of wildfire in order to protect the "household" of nature, as it was then termed. This early ecological idea was in order to preserve the growth of delicate teak trees, which was an important resource for the Royal Navy.

Concerns over teak depletion were raised as early as 1799 and 1805 when the Navy was undergoing a massive expansion during the Napoleonic Wars; this pressure led to the first formal conservation Act, which prohibited the felling of small teak trees. The first forestry officer was appointed in 1806 to regulate and preserve the trees necessary for shipbuilding.[5]

This promising start received a setback in the 1820s and 30s, when laissez-faire economics and complaints from private landowners brought these early conservation attempts to an end.

In 1837, American poet George Pope Morris published "Woodman, Spare that Tree!", a Romantic poem urging a lumberjack to avoid an oak tree that has sentimental value. The poem was set to music later that year by Henry Russell. Lines from the song have been quoted by environmentalists.[6]

Origins of the modern conservation movement

[edit]Conservation was revived in the mid-19th century, with the first practical application of scientific conservation principles to the forests of India. The conservation ethic that began to evolve included three core principles: that human activity damaged the environment, that there was a civic duty to maintain the environment for future generations, and that scientific, empirically based methods should be applied to ensure this duty was carried out. Sir James Ranald Martin was prominent in promoting this ideology, publishing many medico-topographical reports that demonstrated the scale of damage wrought through large-scale deforestation and desiccation, and lobbying extensively for the institutionalization of forest conservation activities in British India through the establishment of Forest Departments.[7] Edward Percy Stebbing warned of desertification of India. The Madras Board of Revenue started local conservation efforts in 1842, headed by Alexander Gibson, a professional botanist who systematically adopted a forest conservation program based on scientific principles. This was the first case of state management of forests in the world.[8]

These local attempts gradually received more attention by the British government as the unregulated felling of trees continued unabated. In 1850, the British Association in Edinburgh formed a committee to study forest destruction at the behest of Hugh Cleghorn a pioneer in the nascent conservation movement.

He had become interested in forest conservation in Mysore in 1847 and gave several lectures at the Association on the failure of agriculture in India. These lectures influenced the government under Governor-General Lord Dalhousie to introduce the first permanent and large-scale forest conservation program in the world in 1855, a model that soon spread to other colonies, as well the United States. In the same year, Cleghorn organised the Madras Forest Department and in 1860 the department banned the use shifting cultivation.[9] Cleghorn's 1861 manual, The forests and gardens of South India, became the definitive work on the subject and was widely used by forest assistants in the subcontinent.[10] In 1861, the Forest Department extended its remit into the Punjab.[11]

Sir Dietrich Brandis, a German forester, joined the British service in 1856 as superintendent of the teak forests of Pegu division in eastern Burma. During that time Burma's teak forests were controlled by militant Karen tribals. He introduced the "taungya" system,[12] in which Karen villagers provided labor for clearing, planting and weeding teak plantations. After seven years in Burma, Brandis was appointed Inspector General of Forests in India, a position he served in for 20 years. He formulated new forest legislation and helped establish research and training institutions. The Imperial Forest School at Dehradun was founded by him.[13][14]

Germans were prominent in the forestry administration of British India. As well as Brandis, Berthold Ribbentrop and Sir William P.D. Schlich brought new methods to Indian conservation, the latter becoming the Inspector-General in 1883 after Brandis stepped down. Schlich helped to establish the journal Indian Forester in 1874, and became the founding director of the first forestry school in England at Cooper's Hill in 1885.[15] He authored the five-volume Manual of Forestry (1889–96) on silviculture, forest management, forest protection, and forest utilization, which became the standard and enduring textbook for forestry students.

Conservation in the United States

[edit]

The American movement received its inspiration from 19th century works that exalted the inherent value of nature, quite apart from human usage. Author Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862) made key philosophical contributions that exalted nature. Thoreau was interested in peoples' relationship with nature and studied this by living close to nature in a simple life. He published his experiences in the book Walden, which argued that people should become intimately close with nature.[16] The ideas of Sir Brandis, Sir William P.D. Schlich and Carl A. Schenck were also very influential—Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the USDA Forest Service, relied heavily upon Brandis' advice for introducing professional forest management in the U.S. and on how to structure the Forest Service.[17][18] In 1864 Abraham Lincoln established the federally preserved Yosemite, before the first national park was created (Yellowstone National Park).

Both conservationists and preservationists appeared in political debates during the Progressive Era (the 1890s–early 1920s). There were three main positions.

- Laissez-faire: The laissez-faire position held that owners of private property, including lumber and mining companies, should be allowed to do anything they wished on their properties. Environmental protection therefore becomes their choice.[19] Businesses are pressured somewhat by the incentive of occupational preservation which requires that they not wholly destroy or consume the resources they rely upon. Said businesses need to innovate or pivot in the event that the exhaustion of a resource is imminent.

- Conservationists: The conservationists, led by future President Theodore Roosevelt and his close ally George Bird Grinnell, were motivated by the wanton waste that was taking place at the hand of market forces, including logging and hunting.[20] This practice resulted in placing a large number of North American game species on the edge of extinction. Roosevelt believed that the laissez-faire approach of the U.S. Government was too wasteful and inefficient. In any case, they noted, most of the natural resources in the western states were already owned by the federal government. The best course of action, they argued, was a long-term plan devised by national experts to maximize the long-term economic benefits of natural resources. To accomplish the mission, Roosevelt and Grinnell formed the Boone and Crockett Club, whose members were some of the best minds and influential men of the day. Its contingency of conservationists, scientists, politicians, and intellectuals became Roosevelt's closest advisers during his march to preserve wildlife and habitat across North America.[21]

- Preservationists: Preservationists, led by John Muir (1838–1914), argued that the conservation policies were not strong enough to protect the interest of the natural world because they continued to focus on the natural world as a source of economic production.

The debate between conservation and preservation reached its peak in the public debates over the construction of California's Hetch Hetchy dam in Yosemite National Park which supplies the water supply of San Francisco. Muir, leading the Sierra Club, declared that the valley must be preserved for the sake of its beauty: "No holier temple has ever been consecrated by the heart of man."

President Roosevelt put conservationist issues high on the national agenda.[22] He worked with all the major figures of the movement, especially his chief advisor on the matter, Gifford Pinchot and was deeply committed to conserving natural resources. He encouraged the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902 to promote federal construction of dams to irrigate small farms and placed 230 million acres (360,000 sq mi; 930,000 km2) under federal protection. Roosevelt set aside more federal land for national parks and nature preserves than all of his predecessors combined.[23]

Roosevelt established the United States Forest Service, signed into law the creation of five national parks, and signed the year 1906 Antiquities Act, under which he proclaimed 18 new national monuments. He also established the first 51 bird reserves, four game preserves, and 150 national forests, including Shoshone National Forest, the nation's first. The area of the United States that he placed under public protection totals approximately 230,000,000 acres (930,000 km2).

Gifford Pinchot had been appointed by McKinley as chief of Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. In 1905, his department gained control of the national forest reserves. Pinchot promoted private use (for a fee) under federal supervision. In 1907, Roosevelt designated 16 million acres (65,000 km2) of new national forests just minutes before a deadline.[24]

In May 1908, Roosevelt sponsored the Conference of Governors held in the White House, with a focus on natural resources and their most efficient use. Roosevelt delivered the opening address: "Conservation as a National Duty".

In 1903 Roosevelt toured the Yosemite Valley with John Muir, who had a very different view of conservation, and tried to minimize commercial use of water resources and forests. Working through the Sierra Club he founded, Muir succeeded in 1905 in having Congress transfer the Mariposa Grove and Yosemite Valley to the federal government.[25] While Muir wanted nature preserved for its own sake, Roosevelt subscribed to Pinchot's formulation, "to make the forest produce the largest amount of whatever crop or service will be most useful, and keep on producing it for generation after generation of men and trees."[26]

Theodore Roosevelt's view on conservationism remained dominant for decades; Franklin D. Roosevelt authorised the building of many large-scale dams and water projects, as well as the expansion of the National Forest System to buy out sub-marginal farms. In 1937, the Pittman–Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act was signed into law, providing funding for state agencies to carry out their conservation efforts.

Since 1970

[edit]Environmental reemerged on the national agenda in 1970, with Republican Richard Nixon playing a major role, especially with his creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. The debates over the public lands and environmental politics played a supporting role in the decline of liberalism and the rise of modern environmentalism. Although Americans consistently rank environmental issues as "important", polling data indicates that in the voting booth voters rank the environmental issues low relative to other political concerns.

The growth of the Republican party's political power in the inland West (apart from the Pacific coast) was facilitated by the rise of popular opposition to public lands reform. Successful Democrats in the inland West and Alaska typically take more conservative positions on environmental issues than Democrats from the Coastal states. Conservatives drew on new organizational networks of think tanks, industry groups, and citizen-oriented organizations, and they began to deploy new strategies that affirmed the rights of individuals to their property, protection of extraction rights, to hunt and recreate, and to pursue happiness unencumbered by the federal government at the expense of resource conservation.[27]

In 2019, convivial conservation was an idea proposed by Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher. Convivial conservation draws on social movements and concepts like environmental justice and structural change to create a post-capitalist approach to conservation.[28] Convivial conservation rejects both human-nature dichotomies and capitalistic political economies. Built on a politics of equity, structural change and environmental justice, convivial conservation is considered a radical theory as it focuses on the structural political-economy of modern nation states and the need to create structural change.[29] Convivial conservation creates a more integrated approach which reconfigures the nature-human configuration to create a world in which humans are recognized as a part of nature. The emphasis on nature as for and by humans creates a human responsibility to care for the environment as a way of caring for themselves. It also redefines nature as not only being pristine and untouched, but cultivated by humans in everyday formats. The theory is a long-term process of structural change to move away from capitalist valuation in favor of a system emphasizing everyday and local living.[29] Convivial conservation creates a nature which includes humans rather than excluding them from the necessity of conservation. While other conservation theories integrate some of the elements of convivial conservation, none move away from both dichotomies and capitalist valuation principles.

The five elements of convivial conservation

[edit]Source:[29]

- The promotion of nature for, to and by humans

- The movement away from the concept of conservation as saving only nonhuman nature

- Emphasis on the long-term democratic engagement with nature rather than elite access and tourism,

- The movement away from the spectacle of nature and instead focusing on the mundane 'everyday nature'

- The democratic management of nature, with nature as commons and in context

Racism and the Conservation Movement

[edit]The early years of the environmental and conservation movements were rooted in the safeguarding of game to support the recreation activities of elite white men, such as sport hunting.[30] This led to an economy to support and perpetuate these activities as well as the continued wilderness conservation to support the corporate interests supplying the hunters with the equipment needed for their sport.[30] Game parks in England and the United States allowed wealthy hunters and fishermen to deplete wildlife, while hunting by Indigenous groups, laborers and the working class, and poor citizens - especially for the express use of sustenance - was vigorously monitored.[30] Scholars have shown that the establishment of the U.S. national parks, while setting aside land for preservation, was also a continuation of preserving the land for the recreation and enjoyment of elite white hunters and nature enthusiasts.[30]

While Theodore Roosevelt was one of the leading activists for the conservation movement in the United States, he also believed that the threats to the natural world were equally threats to white Americans. Roosevelt and his contemporaries held the belief that the cities, industries and factories that were overtaking the wilderness and threatening the native plants and animals were also consuming and threatening the racial vigor that they believed white Americans held which made them superior.[31] Roosevelt was a big believer that white male virility depended on wildlife for its vigor, and that, consequently, depleting wildlife would result in a racially weaker nation.[31] This lead Roosevelt to support the passing of many immigration restrictions, eugenics legislations and wildlife preservation laws.[31] For instance, Roosevelt established the first national parks through the Antiquities Act of 1906 while also endorsing the removal of Indigenous Americans from their tribal lands within the parks.[32] This move was promoted and endorsed by other leaders of the conservation movement, including Frederick Law Olmsted, a leading landscape architect, conservationist, and supporter of the national park system, and Gifford Pinchot, a leading eugenicist and conservationist.[32] Furthering the economic exploitation of the environment and national parks for wealthy whites was the beginning of ecotourism in the parks, which included allowing some Indigenous Americans to remain so that the tourists could get what was to be considered the full "wilderness experience".[33]

Another long-term supporter, partner, and inspiration to Roosevelt, Madison Grant, was a well known American eugenicist and conservationist.[31] Grant worked alongside Roosevelt in the American conservation movement and was even secretary and president of the Boone and Crockett Club.[34] In 1916, Grant published the book The Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History, which based its premise on eugenics and outlined a hierarchy of races, with white, "Nordic" men at the top, and all other races below.[34] The German translation of this book was used by Nazi Germany as the source for many of their beliefs[34] and was even proclaimed by Hitler to be his "Bible".[32]

One of the first established conservation agencies in the United States is the National Audubon Society. Founded in 1905, its priority was to protect and conserve various waterbird species.[35] However, the first state-level Audubon group was created in 1896 by Harriet Hemenway and Minna B. Hall to convince women to refrain from buying hats made with bird feathers- a common practice at the time.[35] The organization is named after John Audubon, a naturalist and legendary bird painter.[36] Audubon was also a slaveholder who also included many racist tales in his books.[36] Despite his views of racial inequality, Audubon did find black and Indigenous people to be scientifically useful, often using their local knowledge in his books and relying on them to collect specimens for him.[36]

The ideology of the conservation movement in Germany paralleled that of the U.S. and England.[37] Early German naturalists of the 20th century turned to the wilderness to escape the industrialization of cities. However, many of these early conservationists became part of and influenced the Nazi party. Like elite and influential Americans of the early 20th century, they embraced eugenics and racism and promoted the idea that Nordic people are superior.[37]

Conservation in Costa Rica

[edit]

Although the conservation movement developed in Europe in the 18th century, Costa Rica as a country has been heralded its champion in the current times.[38] Costa Rica hosts an astonishing number of species, given its size, having more animal and plant species than the US and Canada combined[39] hosting over 500,000 species of plants and animals. Despite this, Costa Rica is only 250 miles long and 150 miles wide. A widely accepted theory for the origin of this unusual density of species is the free mixing of species from both North and South America occurring on this "inter-oceanic" and "inter-continental" landscape.[39] Preserving the natural environment of this fragile landscape, therefore, has drawn the attention of many international scholars and scientists.

MINAE (Ministry of Environment, Energy and Telecommunications) and its responsible for many conservation efforts in Costa Rica it achieves through its many agencies, including SINAC (National System of Conservation Areas), FONAFIFO (national forest fund), and CONAGEBIO (National Commission for Biodiversity Management).

Costa Rica has made conservation a national priority, and has been at the forefront of preserving its natural environment with 28% of its land protected in the form of national parks, reserves, and wildlife refuges, which is under the administrative control of SINAC (National System of Conservation Areas) [40] a division of MINAE (Ministry of Environment, Energy and Telecommunications). SINAC has subdivided the country into various zones depending on the ecological diversity of that region - as seen in figure 1. The country has used this ecological diversity to its economic advantage in the form of a thriving ecotourism industry, putting its commitment to nature, on display to visitors from across the globe. The tourism market in Costa Rica is estimated to grow by USD 1.34 billion from 2023 to 2028, growing at a CAGR of 5.76%.

It is also the only country in the world that generates more than 99% of its electricity from renewable sources, relying on hydropower (72%), wind (13%), geothermal energy (15%), biomass and solar (1%). Critics have pointed out however, that in achieving this milestone, the country has built several dams (providing the bulk of its electricity) some of which have negatively impacted indigenous communities as well as the local flora and fauna.[41]World Wide Fund for Nature

[edit]You know, when we first set up WWF, our objective was to save endangered species from extinction. But we have failed completely; we haven't managed to save a single one. If only we had put all that money into condoms, we might have done some good.

— Sir Peter Scott, Founder of the World Wide Fund for Nature, Cosmos Magazine, 2010[42]

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) is an international non-governmental organization founded in 1961, working in the field of the wilderness preservation, and the reduction of human impact on the environment.[43] It was formerly named the "World Wildlife Fund", which remains its official name in Canada and the United States.[43]

WWF is the world's largest conservation organization with over five million supporters worldwide, working in more than 100 countries, supporting around 1,300 conservation and environmental projects.[44] They have invested over $1 billion in more than 12,000 conservation initiatives since 1995.[45] WWF is a foundation with 55% of funding from individuals and bequests, 19% from government sources (such as the World Bank, DFID, USAID) and 8% from corporations in 2014.[46][47]

WWF aims to "stop the degradation of the planet's natural environment and to build a future in which humans live in harmony with nature."[48] The Living Planet Report is published every two years by WWF since 1998; it is based on a Living Planet Index and ecological footprint calculation.[43] In addition, WWF has launched several notable worldwide campaigns including Earth Hour and Debt-for-Nature Swap, and its current work is organized around these six areas: food, climate, freshwater, wildlife, forests, and oceans.[43][45]

"Conservation Far" approach

[edit]Institutions such as the WWF have historically been the cause of the displacement and divide between Indigenous populations and the lands they inhabit. The reason is the organization's historically colonial, paternalistic, and neoliberal approaches to conservation. Claus, in her article "Drawing the Sea Near: Satoumi and Coral Reef Conservation in Okinawa", expands on this approach, called "conservation far", in which access to lands is open to external foreign entities, such as researchers or tourists, but prohibited to local populations. The conservation initiatives are therefore taking place "far" away. This entity is largely unaware of the customs and values held by those within the territory surrounding nature and their role within it.[49]

"Conservation near" approach

[edit]In Japan, the town of Shiraho had traditional ways of tending to nature that were lost due to colonization and militarization by the United States. The return to traditional sustainability practices constituted a "conservation near" approach. This engages those near in proximity to the lands in the conservation efforts and holds them accountable for their direct effects on its preservation. While conservation-far drills visuals and sight as being the main interaction medium between people and the environment, conservation near includes a hands-on, full sensory experience permitted by conservation-near methodologies.[49] An emphasis on observation only stems from a deeper association with intellect and observation. The alternative to this is more of a bodily or "primitive" consciousness, which is associated with lower-intelligence and people of color. A new, integrated approach to conservation is being investigated in recent years by institutions such as WWF.[49] The socionatural relationships centered on the interactions based in reciprocity and empathy, making conservation efforts being accountable to the local community and ways of life, changing in response to values, ideals, and beliefs of the locals. Japanese seascapes are often integral to the identity of the residents and includes historical memories and spiritual engagements which need to be recognized and considered.[49] The involvement of communities gives residents a stake in the issue, leading to a long-term solution which emphasizes sustainable resource usage and the empowerment of the communities. Conservation efforts are able to take into consideration cultural values rather than the foreign ideals that are often imposed by foreign activists.

Evidence-based conservation

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Evidence-based practices |

|---|

|

|

Evidence-based conservation is the application of evidence in conservation biology and environmental management actions and policy making. It is defined as systematically assessing scientific information from published, peer-reviewed publications and texts, practitioners' experiences, independent expert assessment, and local and indigenous knowledge on a specific conservation topic. This includes assessing the current effectiveness of different management interventions, threats and emerging problems and economic factors.[50]

Evidence-based conservation was organized based on the observations that decision making in conservation was based on intuition and or practitioner experience often disregarding other forms of evidence of successes and failures (e.g. scientific information). This has led to costly and poor outcomes.[51] Evidence-based conservation provides access to information that will support decision making through an evidence-based framework of "what works" in conservation.[52]

The evidence-based approach to conservation is based on evidence-based practice which started in medicine and later spread to nursing, education, psychology and other fields. It is part of the larger movement towards evidence-based practices.Areas of concern

[edit]

Deforestation and overpopulation are issues affecting all regions of the world. The consequent destruction of wildlife habitat has prompted the creation of conservation groups in other countries, some founded by local hunters who have witnessed declining wildlife populations first hand. Also, it was highly important for the conservation movement to solve problems of living conditions in the cities and the overpopulation of such places.

Boreal forest and the Arctic

[edit]The idea of incentive conservation is a modern one but its practice has clearly defended some of the sub Arctic wildernesses and the wildlife in those regions for thousands of years, especially by indigenous peoples such as the Evenk, Yakut, Sami, Inuit and Cree. The fur trade and hunting by these peoples have preserved these regions for thousands of years. Ironically, the pressure now upon them comes from non-renewable resources such as oil, sometimes to make synthetic clothing which is advocated as a humane substitute for fur. (See Raccoon dog for case study of the conservation of an animal through fur trade.) Similarly, in the case of the beaver, hunting and fur trade were thought to bring about the animal's demise, when in fact they were an integral part of its conservation. For many years children's books stated and still do, that the decline in the beaver population was due to the fur trade. In reality however, the decline in beaver numbers was because of habitat destruction and deforestation, as well as its continued persecution as a pest (it causes flooding). In Cree lands, however, where the population valued the animal for meat and fur, it continued to thrive. The Inuit defend their relationship with the seal in response to outside critics.[53]

Latin America (Bolivia)

[edit]The Izoceño-Guaraní of Santa Cruz Department, Bolivia, is a tribe of hunters who were influential in establishing the Capitania del Alto y Bajo Isoso (CABI). CABI promotes economic growth and survival of the Izoceno people while discouraging the rapid destruction of habitat within Bolivia's Gran Chaco. They are responsible for the creation of the 34,000 square kilometre Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park and Integrated Management Area (KINP). The KINP protects the most biodiverse portion of the Gran Chaco, an ecoregion shared with Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil. In 1996, the Wildlife Conservation Society joined forces with CABI to institute wildlife and hunting monitoring programs in 23 Izoceño communities. The partnership combines traditional beliefs and local knowledge with the political and administrative tools needed to effectively manage habitats. The programs rely solely on voluntary participation by local hunters who perform self-monitoring techniques and keep records of their hunts. The information obtained by the hunters participating in the program has provided CABI with important data required to make educated decisions about the use of the land. Hunters have been willing participants in this program because of pride in their traditional activities, encouragement by their communities and expectations of benefits to the area.

Africa (Botswana)

[edit]In order to discourage illegal South African hunting parties and ensure future local use and sustainability, indigenous hunters in Botswana began lobbying for and implementing conservation practices in the 1960s. The Fauna Preservation Society of Ngamiland (FPS) was formed in 1962 by the husband and wife team: Robert Kay and June Kay, environmentalists working in conjunction with the Batawana tribes to preserve wildlife habitat.

The FPS promotes habitat conservation and provides local education for preservation of wildlife. Conservation initiatives were met with strong opposition from the Botswana government because of the monies tied to big-game hunting. In 1963, BaTawanga Chiefs and tribal hunter/adventurers in conjunction with the FPS founded Moremi National Park and Wildlife Refuge, the first area to be set aside by tribal people rather than governmental forces. Moremi National Park is home to a variety of wildlife, including lions, giraffes, elephants, buffalo, zebra, cheetahs and antelope, and covers an area of 3,000 square kilometers. Most of the groups involved with establishing this protected land were involved with hunting and were motivated by their personal observations of declining wildlife and habitat.

See also

[edit]- Air pollution in the United Kingdom

- Air pollution in the United States

- Australian Grains Genebank

- Conservation biology

- Conservation ethic

- Ecology

- Ecology movement

- Energy conservation

- Environmental history

- Environmental history of the United States

- Environmental movement

- Environmental protection

- Environmentalism

- Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850–1920

- Factor 10

- Forest protection

- Habitat conservation

- History of environmentalism in Germany

- List of environmental organizations

- List of environment topics

- Marine conservation

- Natural environment

- Natural landscape

- Soil conservation

- Sustainability

- Timeline of history of environmentalism

- U.S. National Park Service

- Water conservation

- Wetland conservation

- Wildlife conservation

- Wildlife management

References

[edit]- ^ Harding, Russ. "Conservationist or Environmentalist?". Mackinac Center for Public Policy. Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2021-05-02.

- ^ Gifford, John C. (1945). Living by the Land. Coral Gables, Florida: Glade House. p. 8. ASIN B0006EUXGQ.

- ^ John Evelyn, Sylva, Or A Discourse of Forest Trees ... with an Essay on the Life and Works of the Author by John Nisbet, Fourth Edition (1706), reprinted London: Doubleday & Co., 1908, V1, p. lxv; online edn, March 2007 [1], accessed 29 Dec 2012. This source (John Nisbet) states: "There can be no doubt that John Evelyn, both during his own lifetime and throughout the two centuries which have elapsed since his death in 1706, has exerted more individual influence, through his charming Sylva, ... than can be ascribed to any other individual." Nisbet adds that "Evelyn was by no means the first [author] who wrote on [forestry]. That honour belongs to Master Fitzherbert, whose Boke of Husbandrie was published in 1534" (V1, p. lxvi).

- ^ Badri, Adarsh (2024-03-04). "Feeling for the Anthropocene: affective relations and ecological activism in the global South". International Affairs. 100 (2): 731–749. doi:10.1093/ia/iiae010. ISSN 0020-5850.

- ^ "History of forests in India". Archived from the original on 2018-09-04. Retrieved 2013-10-13.

- ^ Best remembered poems. Martin Gardner. New York: Dover Publications. 1992. p. 118. ISBN 0-486-27165-X. OCLC 26401592.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Stebbing, E.P. (1922)The forests of India vol. 1, pp. 72-81

- ^ Barton, Greg (2002). Empire Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781139434607.

- ^ MUTHIAH, S. (Nov 5, 2007). "A life for forestry". The Hindu. Archived from the original on November 8, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ^ Cleghorn, Hugh Francis Clarke (1861). The Forests and Gardens of South India (Original from the University of Michigan, Digitized Feb 10, 2006 ed.). London: W. H. Allen. OCLC 301345427.

- ^ Oliver, J.W. (1901). "Forestry in India". The Indian Forester. Vol. v.27 (Original from Harvard University, Digitized Apr 4, 2008 ed.). Allahabad: R. P. Sharma, Business Manager, Indian Forester. pp. 617–623.

- ^ King KFS (1968). "Agro-silviculture (the taungya system)". University of Ibadan / Dept. of Forestry, Bulletin no. 1, 109

- ^ Weil, Benjamin (1 April 2006). "Conservation, Exploitation, and Cultural Change in the Indian Forest Service, 1875-1927". Environmental History. 11 (2): 319–343. doi:10.1093/envhis/11.2.319.

- ^ Madhav Gadgil and Ramachandra Guha, This Fissured Land: An Ecological History of India (1993)

- ^ Burley, Jeffery, et al. 2009. "A History of Forestry at Oxford", British Scholar, Vol. 1, No. 2., pp.236-261. Accessed: May 6, 2012.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David, Walden, OCLC 1189910652

- ^ America has been the context for both the origins of conservation history and its modern form, environmental history Archived 2012-03-13 at the Wayback Machine. Asiaticsociety.org.bd. Retrieved on 2011-09-01.

- ^ Rawat, Ajay Singh (1993). Indian Forestry: A Perspective. Indus Publishing. pp. 85–88. ISBN 9788185182780.

- ^ Samuel P. Hays, Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency: The Progressive Conservation Movement, 1890-1920 (1959)

- ^ Benjamin Redekop, "Embodying the Story: The Conservation Leadership of Theodore Roosevelt" in Leadership (2015). DOI: 10.1177/1742715014546875. online Archived 2016-01-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Archives of the Boone and Crockett Club". Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ Douglas G. Brinkley, The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (2009)

- ^ W. Todd Benson, President Theodore Roosevelt's Conservations Legacy (2003)

- ^ Char Miller, Seeking the Greatest Good: The Conservation Legacy of Gifford Pinchot (2013)

- ^ "U.S. Statutes at Large, Vol. 26, Chap. 1263, pp. 650-52. "An act to set apart certain tracts of land in the State of California as forest reservations." [H.R. 12187]". Evolution of the Conservation Movement, 1850-1920. Library of Congress.

- ^ Gifford Pinchot, Breaking New Ground, (1947) p. 32.

- ^ * Turner, James Morton, "The Specter of Environmentalism": Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right. The Journal of American History 96.1 (2009): 123-47 online at History Cooperative Archived 2009-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Büscher, Bram; Dressler, Wolfram; Fletcher, Robert, eds. (2014-05-29). Nature Inc. University of Arizona Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt183pdh2. ISBN 978-0-8165-9885-4.

- ^ a b c Büscher, B. and Fletcher, R., 2019. Towards convivial conservation. Conservation & Society, 17(3), pp.283-296.

- ^ a b c d Hellegers, Desiree (December 2017). "The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege and Environmental Protection by Dorceta E. Taylor". Canadian Journal of History. 52 (3): 609–611. doi:10.3138/cjh.ach.52.3.rev22. ISSN 0008-4107.

- ^ a b c d Powell, Miles A. (2016). Vanishing America : species extinction, racial peril, and the origins of conservation. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97295-7. OCLC 973532814.

- ^ a b c Purdy, Jedediah (August 13, 2015). "Environmentalism's Racist History". The New Yorker.

- ^ Merchant, Carolyn (2003-07-01). "Shades of Darkness: Race and Environmental History". Environmental History. 8 (3): 380–394. doi:10.2307/3986200. ISSN 1084-5453. JSTOR 3986200.

- ^ a b c Peter., Spiro, Jonathan (2009). Defending the master race : conservation, eugenics, and the legacy of Madison Grant. University of Vermont Press. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-6. OCLC 227929377.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "The History of Audubon". Audubon. 2015-01-09. Retrieved 2022-03-29.

- ^ a b c "The Myth of John James Audubon". Audubon. 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2022-03-29.

- ^ a b Landry, Marc (February 2010). "How Brown were the Conservationists? Naturism, Conservation, and National Socialism, 1900–1945". Contemporary European History. 19 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1017/S0960777309990208. ISSN 0960-7773.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (2010-10-25). "Costa Rica recognised for biodiversity protection". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-06-09.

- ^ a b Evans, Sterling (2010-06-28). The Green Republic: A Conservation History of Costa Rica. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292789289.

- ^ "Estado de la Biodiversidad en Costa Rica". inbio.ac.cr. Archived from the original on 2010-03-01. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- ^ "Costa Rica runs entirely on renewable energy for 300 days this year". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- ^ "A plague of people". Cosmos. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d Troëng, Sebastian; Rankin, Eddy (2005-01-01). "Long-term conservation efforts contribute to positive green turtle Chelonia mydas nesting trend at Tortuguero, Costa Rica". Biological Conservation. 121 (1): 111–116. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2004.04.014. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ^ "WWF conservation projects around the world".

- ^ a b "WWF - Endangered Species Conservation". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ "How is WWF run?". Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- ^ WWFN-International Annual Review (PDF). World Wide Fund for Nature. 2014. p. 37. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ "WWF's Mission, Guiding Principles and Goals". WWF. Archived from the original on 2019-01-13. Retrieved 2019-01-13.

- ^ a b c d Claus, C. Anne (2020). Drawing the sea near : Satoumi and coral reef conservation in Okinawa. Minneapolis. ISBN 978-1-4529-5947-4. OCLC 1156432505.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Basics". Conservation Evidence. Retrieved 2015-03-07.

- ^ Sutherland, William J; Pullin, Andrew S.; Dolman, Paul M.; Knight, Teri M. (June 2004). "The need for evidence-based conservation". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 19 (6): 305–308. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.018. PMID 16701275.

- ^ Sutherland, William J. (July 2003). "Evidence-based Conservation". Conservation in Practice. 4 (3): 39–42. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4629.2003.tb00068.x.

- ^ "Inuit Ask Europeans to Support Its Seal Hunt and Way of Life" (PDF). 6 March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 June 2007. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

Further reading

[edit]World

[edit]- Barton, Gregory A. Empire, Forestry and the Origins of Environmentalism, (2002), covers British Empire

- Clover, Charles. The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. (2004) Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

- Haq, Gary, and Alistair Paul. Environmentalism since 1945 (Routledge, 2013).

- Jones, Eric L. "The History of Natural Resource Exploitation in the Western World," Research in Economic History, 1991 Supplement 6, pp 235–252

- McNeill, John R. Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century (2000).

Regional studies

[edit]Africa

[edit]- Adams, Jonathan S.; McShane, Thomas O. Myth of Wild Africa: Conservation without Illusion (1992) 266p; covers 1900 to 1980s

- Anderson, David; Grove, Richard. Conservation in Africa: People, Policies & Practice (1988), 355pp

- Bolaane, Maitseo. "Chiefs, Hunters & Adventurers: The Foundation of the Okavango/Moremi National Park, Botswana". Journal of Historical Geography. 31.2 (Apr. 2005): 241–259.

- Carruthers, Jane. "Africa: Histories, Ecologies, and Societies," Environment and History, 10 (2004), pp. 379–406;

- Showers, Kate B. Imperial Gullies: Soil Erosion and Conservation in Lesotho (2005) 346pp

Asia-Pacific

[edit]- Bolton, Geoffrey. Spoils and Spoilers: Australians Make Their Environment, 1788-1980 (1981) 197pp

- Economy, Elizabeth. The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China's Future (2010)

- Elvin, Mark. The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China (2006)

- Grove, Richard H.; Damodaran, Vinita Jain; Sangwan, Satpal. Nature and the Orient: The Environmental History of South and Southeast Asia (1998) 1036pp

- Johnson, Erik W., Saito, Yoshitaka, and Nishikido, Makoto. "Organizational Demography of Japanese Environmentalism," Sociological Inquiry, Nov 2009, Vol. 79 Issue 4, pp 481–504

- Thapar, Valmik. Land of the Tiger: A Natural History of the Indian Subcontinent (1998) 288pp

Latin America

[edit]- Boyer, Christopher. Political Landscapes: Forests, Conservation, and Community in Mexico. Duke University Press (2015)

- Dean, Warren. With Broadax and Firebrand: The Destruction of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (1997)

- Evans, S. The Green Republic: A Conservation History of Costa Rica. University of Texas Press. (1999)

- Funes Monzote, Reinaldo. From Rainforest to Cane Field in Cuba: An Environmental History since 1492 (2008)

- Melville, Elinor G. K. A Plague of Sheep: Environmental Consequences of the Conquest of Mexico (1994)

- Miller, Shawn William. An Environmental History of Latin America (2007)

- Noss, Andrew and Imke Oetting. "Hunter Self-Monitoring by the Izoceño -Guarani in the Bolivian Chaco". Biodiversity & Conservation. 14.11 (2005): 2679–2693.

- Simonian, Lane. Defending the Land of the Jaguar: A History of Conservation in Mexico (1995) 326pp

- Wakild, Emily. An Unexpected Environment: National Park Creation, Resource Custodianship, and the Mexican Revolution. University of Arizona Press (2011).

Europe and Russia

[edit]- Arnone Sipari, Lorenzo, Scritti scelti di Erminio Sipari sul Parco Nazionale d'Abruzzo (1922–1933) (2011), 360pp.

- Barca, Stefania, and Ana Delicado. "Anti-nuclear mobilisation and environmentalism in Europe: A view from Portugal (1976–1986)." Environment and History 22.4 (2016): 497–520. online[dead link]

- Bonhomme, Brian. Forests, Peasants and Revolutionaries: Forest Conservation & Organization in Soviet Russia, 1917–1929 (2005) 252pp.

- Cioc, Mark. The Rhine: An Eco-Biography, 1815–2000 (2002).

- Dryzek, John S., et al. Green states and social movements: environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway (Oxford UP, 2003).

- Jehlicka, Petr. "Environmentalism in Europe: an east-west comparison." in Social change and political transformation (Routledge, 2018) pp. 112–131.

- Simmons, I.G. An Environmental History of Great Britain: From 10,000 Years Ago to the Present (2001).

- Uekotter, Frank. The greenest nation?: A new history of German environmentalism (MIT Press, 2014).

- Weiner, Douglas R. Models of Nature: Ecology, Conservation and Cultural Revolution in Soviet Russia (2000) 324pp; covers 1917 to 1939.

United States

[edit]- Bates, J. Leonard. "Fulfilling American Democracy: The Conservation Movement, 1907 to 1921", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, (1957), 44#1 pp. 29–57. in JSTOR

- Brinkley, Douglas G. The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America, (2009) excerpt and text search

- Cawley, R. McGreggor. Federal Land, Western Anger: The Sagebrush Rebellion and Environmental Politics (1993), on conservatives

- Flippen, J. Brooks. Nixon and the Environment (2000).

- Hays, Samuel P. Beauty, Health, and Permanence: Environmental Politics in the United States, 1955–1985 (1987), the standard scholarly history

- Hays, Samuel P. A History of Environmental Politics since 1945 (2000), shorter standard history

- Hays, Samuel P. Conservation and the Gospel of Efficiency (1959), on Progressive Era.

- King, Judson. The Conservation Fight, From Theodore Roosevelt to the Tennessee Valley Authority (2009)

- Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind, (3rd ed. 1982), the standard intellectual history

- Pinchot, Gifford (1922). . Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.).

- Rothmun, Hal K. The Greening of a Nation? Environmentalism in the United States since 1945 (1998)

- Scheffer, Victor B. The Shaping of Environmentalism in America (1991).

- Sellers, Christopher. Crabgrass Crucible: Suburban Nature and the Rise of Environmentalism in Twentieth-Century America (2012)

- Strong, Douglas H. Dreamers & Defenders: American Conservationists. (1988) online edition Archived 2007-12-01 at the Wayback Machine, good biographical studies of the major leaders

- Taylor, Dorceta E. The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection (Duke U.P. 2016) x, 486 pp.

- Turner, James Morton, "The Specter of Environmentalism": Wilderness, Environmental Politics, and the Evolution of the New Right. The Journal of American History 96.1 (2009): 123-47 online at History Cooperative

- Vogel, David. California Greenin': How the Golden State Became an Environmental Leader (2018) 280 pp online review

Historiography

[edit]- Cioc, Mark, Björn-Ola Linnér, and Matt Osborn, "Environmental History Writing in Northern Europe," Environmental History, 5 (2000), pp. 396–406

- Bess, Michael, Mark Cioc, and James Sievert, "Environmental History Writing in Southern Europe," Environmental History, 5 (2000), pp. 545–56;

- Coates, Peter. "Emerging from the Wilderness (or, from Redwoods to Bananas): Recent Environmental History in the United States and the Rest of the Americas," Environment and History, 10 (2004), pp. 407–38

- Hay, Peter. Main Currents in Western Environmental Thought (2002), standard scholarly history excerpt and text search

- McNeill, John R. "Observations on the Nature and Culture of Environmental History," History and Theory, 42 (2003), pp. 5–43.

- Robin, Libby, and Tom Griffiths, "Environmental History in Australasia," Environment and History, 10 (2004), pp. 439–74

- Worster, Donald, ed. The Ends of the Earth: Perspectives on Modern Environmental History (1988)

External links

[edit]Conservation movement

View on GrokipediaThe conservation movement arose in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries amid concerns over the rapid exhaustion of natural resources through unchecked exploitation, advocating for their systematic management to support long-term economic productivity and public benefit rather than indefinite preservation without use.[1][2]

Pioneered by figures like Gifford Pinchot, who emphasized scientific forestry and resource efficiency as the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service, the movement gained momentum under President Theodore Roosevelt, who safeguarded approximately 230 million acres of public lands, including national forests, parks, and wildlife refuges, through executive actions and legislative support.[3][4][5]

While contrasting with preservationist ideals championed by John Muir, which prioritized wilderness sanctity over human intervention, conservation's utilitarian approach—rooted in preventing waste and enabling sustained yield—laid foundational policies for federal land administration and influenced global resource stewardship, though it faced opposition from industrial interests seeking unrestricted access.[6][7][8]

Definition and Core Principles

Historical and Philosophical Foundations

The philosophical foundations of the conservation movement trace back to European forestry practices in the 17th and 18th centuries, driven by the depletion of timber resources essential for naval and economic needs. In England, John Evelyn's Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees (1664) urged systematic reforestation to replenish oak supplies exhausted by shipbuilding demands during conflicts like the Anglo-Dutch Wars, emphasizing the cultivation of timber as a renewable national asset rather than unchecked exploitation.[9] This work, presented to the Royal Society, laid early groundwork for viewing forests as managed economic resources, influencing subsequent British and continental approaches to woodland husbandry.[10] By the early 18th century, German foresters formalized the concept of sustained yield, or Nachhaltigkeit, coined by Hans Carl von Carlowitz in 1713 to denote harvesting timber at rates not exceeding natural regrowth, ensuring perpetual supply amid mining and construction pressures in Saxony.[11] This principle rested on empirical assessments of forest growth cycles and carrying capacity, prioritizing long-term productivity over short-term gains—a causal framework recognizing that overexploitation leads to irreversible scarcity and economic collapse, as evidenced by depleted central European woodlands from medieval expansion.[12] Austrian and Prussian administrators implemented these methods around 1800 through state-regulated inventories and rotation systems, establishing conservation as a science of balanced resource extraction grounded in measurable data rather than aesthetic or moral imperatives alone.[13] In the United States, these European ideas were adapted into the core philosophy of the conservation movement by the late 19th century, emphasizing utilitarian management for human welfare. Gifford Pinchot, first chief of the U.S. Forest Service (1905–1910), advocated "the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run," defining conservation as the wise use of resources to prevent waste and secure benefits for future generations, informed by his training at the École Nationale Forestière in Nancy, France.[14] This approach contrasted with preservationist views by permitting regulated exploitation—such as selective logging in national forests—while rejecting laissez-faire depletion, as seen in the rapid deforestation of American frontiers that halved eastern woodlands between 1600 and 1900.[8] Pinchot's framework, rooted in preventing physical and economic waste, prioritized empirical forest management over romantic ideals, influencing policies like the 1891 Forest Reserves Act that protected 107 million acres by 1907.[15]Distinction from Preservationism and Radical Environmentalism

The conservation movement distinguishes itself from preservationism primarily through its advocacy for the sustainable, managed utilization of natural resources to benefit human societies over the long term, rather than prohibiting human intervention altogether. Forester Gifford Pinchot, the first chief of the U.S. Forest Service appointed in 1905, exemplified this approach by promoting "the greatest good for the greatest number" via scientific management of forests for timber harvesting, watershed protection, and recreation, arguing that resources should be used but not wasted.[16] In contrast, preservationism, as championed by naturalist John Muir, sought to safeguard wilderness areas from any extractive or developmental activities, emphasizing nature's intrinsic aesthetic and spiritual value independent of human needs; Muir's efforts led to the establishment of Yosemite National Park in 1890 but clashed with utilitarian policies, such as his opposition to the Hetch Hetchy Valley dam project authorized by Congress in 1913, which Pinchot supported for San Francisco's water supply.[17] This tension culminated in a philosophical rift, with conservation viewing preservation as economically shortsighted and preservation critiquing conservation as subordinating nature to short-term exploitation.[6] Unlike radical environmentalism, which often employs confrontational tactics and prioritizes ecological purity over human welfare, conservation integrates evidence-based practices that accommodate compatible economic activities, such as regulated logging or grazing, to prevent resource depletion. Radical environmentalism, emerging prominently in the 1970s and 1980s through groups like Earth First! founded in 1980, advocates deep ecology principles that assign moral equivalence to all life forms, sometimes endorsing civil disobedience or sabotage—termed "monkeywrenching"—to halt developments like logging roads or dams, as detailed in Dave Foreman's 1985 book Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching.[18] Conservationists, by contrast, favor institutional mechanisms like zoning and quotas, as seen in the U.S. Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960, which mandates balancing timber production, wildlife habitat, and recreation on federal lands without the absolutism that characterizes radical positions, which have been criticized for alienating stakeholders and ignoring human dependencies on ecosystems.[17] This pragmatic orientation aligns conservation with broader societal goals, whereas radical environmentalism's biocentric absolutism can lead to policies that undervalue empirical cost-benefit analyses of human-nature interactions.[19]Emphasis on Sustainable Human Use

In the conservation movement, sustainable human use refers to the managed exploitation of natural resources—such as timber, fisheries, and wildlife—designed to provide economic and societal benefits while preventing depletion and maintaining ecological productivity over the long term. This principle, rooted in utilitarian ethics, prioritizes "the greatest good for the greatest number" through scientific management techniques like sustained-yield harvesting, where annual removals do not exceed natural regeneration rates, ensuring perpetual resource availability.[20][21] Gifford Pinchot, as the inaugural chief of the U.S. Forest Service from 1905 to 1910, championed this ethic by defining conservation as "the wise use of the earth and its resources for the lasting good of men," applying business-like efficiency to public lands to balance development with renewal.[14] This approach starkly contrasts with preservationism, which seeks to shield ecosystems from any extractive human activity to preserve their pristine state; conservation, by contrast, views humans as integral to resource stewardship, advocating active intervention to avert waste from unregulated exploitation.[7][17] In practice, sustainable use in forestry involved establishing national forests for multiple purposes, including timber production, watershed protection, and recreation, with policies mandating reforestation after logging—evident in the U.S. Forest Service's early 20th-century management of over 150 million acres by 1910, where cutting cycles were calibrated to tree growth rates.[20] Wildlife management similarly emphasized regulated hunting quotas and habitat enhancement; for instance, under Theodore Roosevelt's administration (1901–1909), initiatives like the establishment of 51 bird refuges and big-game preserves promoted controlled harvests to curb overhunting while supporting rural economies dependent on game.[22] Historical precedents informed these methods, drawing from European sustained-yield forestry models developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, where German and French foresters quantified annual wood increments to guide harvests, influencing American practices amid rapid 19th-century deforestation that felled over 100 million acres of U.S. timberland by 1900.[23] In fisheries, conservation applied similar logic through early 20th-century stocking programs and size limits, as seen in the U.S. Fish Commission's efforts from 1871 onward to propagate species like salmon for commercial fisheries without exhausting wild stocks.[24] These strategies underscored a causal realism: unchecked human demand drives resource scarcity, but informed regulation—backed by inventory data and yield models—enables perpetual utility, as validated by long-term forest regrowth metrics showing U.S. timber volumes stabilizing post-1920 after conservation reforms.[25] Critics from preservationist circles, such as John Muir, argued that utilitarian use risked commodifying nature, yet empirical outcomes, including averted famines from sustained agriculture and averted species extinctions via bag limits, affirm the movement's efficacy in reconciling human prosperity with resource integrity.[26]Historical Development

Precursors in Traditional Resource Management

Traditional resource management practices in pre-modern societies often involved community-enforced rules to prevent depletion of forests, fisheries, and wildlife, laying groundwork for later systematic conservation efforts. In medieval Europe, forest laws regulated access and use to sustain wood supplies for construction, fuel, and hunting. For instance, the Charter of the Forest, enacted in England in 1217, curtailed expansive royal forest claims established under Norman rule, restoring common rights to pasture, gather wood, and hunt small game while prohibiting wasteful practices like unauthorized clear-cutting.[27] This charter represented an early legal framework for balancing elite privileges with communal sustainability, influencing subsequent European resource governance.[28] Tree-ring data from central Europe indicate that woodland management intensified around the 10th-12th centuries, with coppicing and selective harvesting techniques enabling regeneration cycles that maintained timber availability amid growing demand from population expansion and urbanization.[29] Common lands, governed by local assemblies across regions like England and the Alps, allocated grazing, foraging, and fuelwood rights through rotational use and fines for overuse, fostering resilience against scarcity without centralized state intervention.[30] These systems, rooted in customary law rather than scientific forestry, demonstrated empirical adaptations to local carrying capacities, though vulnerabilities to enclosure and commercialization emerged by the early modern period. In North America, indigenous groups employed controlled burning for millennia to shape ecosystems, enhancing biodiversity and resource productivity. Archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence shows that practices by tribes such as the Salish, Karuk, and Yurok involved low-intensity fires to clear underbrush, promote nut-bearing trees like oaks, and create habitats for game, thereby reducing catastrophic wildfire risks and sustaining yields of food plants and animals.[31][32] Seasonal restrictions on hunting and fishing, informed by observations of animal migrations and spawning cycles, prevented local extinctions; for example, Pacific Northwest tribes regulated salmon harvests through communal quotas and taboos during vulnerable periods.[33] These methods, transmitted orally across generations, prioritized long-term viability over short-term extraction, contrasting with post-colonial overexploitation. Similar approaches appeared in other regions, such as sacred groves in sub-Saharan Africa, where communities in West African societies protected forested areas through taboos and rituals, preserving watersheds and biodiversity hotspots as refugia amid agricultural expansion.[34] In Polynesia, Tongan islanders practiced selective harvesting and rotational fallowing, combined with prohibitions (tapu) on overfishing reefs, maintaining marine and terrestrial stocks in resource-limited atolls.[35] While not uniformly successful—some practices faltered under population pressures or external shocks—these traditional systems emphasized causal links between human actions and ecological feedback, prefiguring conservation's focus on sustainable yields without modern metrics.[36]19th-Century Origins in Europe and North America

In Europe, scientific forestry emerged as a cornerstone of early conservation practices during the 19th century, emphasizing sustained-yield principles to counteract historical overexploitation from mining, shipbuilding, and fuel demands. German foresters, building on 18th-century concepts like those articulated by Hans Carl von Carlowitz in 1713, refined systematic management through yield tables, compartment-based harvesting, and replanting schedules to ensure perpetual resource availability.[37] Heinrich Cotta (1763–1844), a pivotal figure, advanced forestry as a quantitative science by developing valuation methods and management plans, founding the Royal Saxon Academy of Forestry around 1811 and influencing Prussian policies that prioritized calculated annual cuts matching growth rates.[38] These approaches, formalized in early 19th-century Prussian forest laws, treated forests as economic assets requiring empirical inventory and regulation rather than laissez-faire extraction, yielding measurable recoveries in timber stocks by mid-century.[39] France and other Continental states paralleled these efforts, with post-Napoleonic reforms under the 1827 Forest Code mandating protective silviculture and reforestation to combat erosion and secure naval timber, informed by hydrological studies linking deforestation to flooding and soil loss.[40] By the 1850s, European forestry schools trained professionals in data-driven practices, exporting models that underscored conservation as compatible with human utility—prioritizing long-term productivity over wilderness sanctity. These systems demonstrated causal links between mismanagement and scarcity, fostering policies that restored degraded lands through state oversight, though often critiqued for prioritizing monocultures over biodiversity.[41] In North America, 19th-century conservation origins arose from frontier resource exhaustion and transatlantic exchanges, with European forestry informing responses to unchecked logging and agrarian expansion that denuded Eastern woodlands by the 1850s. George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature (1864) provided an empirical foundation, cataloging historical cases of deforestation-induced desertification, erosion, and climate shifts—from Mediterranean antiquity to contemporary America—and arguing for active human intervention to rehabilitate ecosystems via replanting and soil conservation.[42] Drawing on European precedents, Marsh advocated "judicious use" over exploitation, influencing policymakers to view nature as modifiable yet finite, with data on watershed degradation prompting early federal inquiries into timber famine.[43] This intellectual shift materialized in practical steps, such as New York's 1885 Forest Commission recommending preserved reserves for sustainable harvesting, echoing German models of regulated yield.[44] By 1891, the U.S. General Land Law Revision Act authorized forest reserves on public domains, totaling 13 million acres by 1897, to safeguard water flows and timber against private monopolies—marking a transition from ad hoc preservation, like Yellowstone National Park's 1872 establishment, toward managed multiple-use frameworks.[45] These origins reflected causal realism: empirical evidence of depletion drove policies prioritizing stewardship for societal benefit, though implementation lagged until institutional reforms in the subsequent era.[46]Progressive Era and Early 20th-Century Institutionalization

The Progressive Era marked a pivotal phase in the institutionalization of the conservation movement in the United States, driven by federal initiatives emphasizing scientific management of natural resources for sustained human benefit. President Theodore Roosevelt, serving from 1901 to 1909, championed policies rooted in utilitarian principles, appointing Gifford Pinchot as the first Chief of the newly formed United States Forest Service on February 1, 1905. This agency, transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture, was tasked with administering national forests to ensure their productive capacity through practices like selective logging and fire prevention, reflecting Pinchot's doctrine of achieving "the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run."[47][5] Roosevelt's administration expanded protected lands significantly, designating approximately 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reservations, four national game preserves, five national parks, and 18 national monuments by 1909. The Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906, empowered the president to unilaterally proclaim national monuments to safeguard prehistoric ruins, historic sites, and natural features threatened by exploitation, thereby enabling rapid conservation actions without congressional delay. This legislation facilitated the protection of sites like Devils Tower in Wyoming, the first national monument, underscoring a pragmatic approach to preserving resources amid industrialization's pressures.[48][49] Further institutionalization occurred through the National Conservation Commission, established by Roosevelt in June 1908 following the White House Conference of Governors in May, where he delivered his "Conservation as a National Duty" address. The commission, comprising experts from government, industry, and science, conducted the first national inventory of resources, including forests, water, and minerals, to inform policy and prevent waste. Its 1909 report advocated coordinated federal-state efforts for resource management, influencing subsequent legislation like the Weeks Act of 1911, which enabled federal acquisition of forested lands for watershed protection.[50][1] These developments entrenched conservation within federal bureaucracy, shifting from ad hoc protections to systematic oversight, though tensions arose between utilitarian forestry and preservationist ideals, as seen in Pinchot's support for the Hetch Hetchy dam project in Yosemite against John Muir's opposition. By the early 1920s, under subsequent administrations, conservation principles had permeated agencies like the Bureau of Reclamation, established via the Newlands Act of 1902 for irrigation projects that balanced agricultural expansion with water resource sustainability.[1]Post-World War II Global Expansion

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), founded on October 5, 1948, in Fontainebleau, France, marked the initial institutionalization of global conservation efforts following World War II, uniting 18 governments, 7 NGOs, and 27 national conservation groups to address threats to nature amid post-war reconstruction and decolonization.[51] Initially named the International Union for the Protection of Nature, it evolved into the IUCN in 1956 and established the Red List of Threatened Species in 1964, providing the first comprehensive global assessment of species endangerment based on scientific data from member experts.[52] By coordinating international standards for protected areas and advising on policy, the IUCN facilitated the designation of over 1,000 new protected sites worldwide by the 1960s, influencing national strategies in Europe, Africa, and Asia.[53] Complementing the IUCN's framework, the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), established on September 11, 1961, in Morges, Switzerland, by figures including biologist Julian Huxley and IUCN vice-president Peter Scott, focused on fundraising to support field-based conservation projects, raising over $5.6 million in its first decade for grants targeting species like the Arabian oryx and tiger populations.[54] This influx of private capital enabled expansion into developing regions, funding anti-poaching initiatives and habitat surveys in Africa and Asia, where WWF projects by 1970 had supported the protection of approximately 10 million hectares of land.[55] The organization's emphasis on flagship species drew public engagement, amplifying conservation's reach beyond governmental efforts and establishing model reserves that integrated local communities in sustainable resource use. Post-war decolonization spurred national park establishments in the Global South, with sub-Saharan Africa seeing dozens of new parks by the 1960s, such as Kenya's expansion under the 1945 National Parks Ordinance leading to Tsavo National Park's formal protection in 1948, covering 20,808 square kilometers to safeguard elephant herds and savanna ecosystems amid growing human pressures.[56] In Asia and Latin America, European models influenced top-down creations like India's Jim Corbett National Park redesignation in 1957 for tiger conservation and Indonesia's Ujung Kulon National Park in 1950, protecting the last Javan rhinoceros; these efforts, often backed by IUCN assessments, increased protected area coverage from under 1% to over 5% of land in many nations by 1970, though implementation frequently prioritized wildlife over indigenous land rights.[57] The 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm represented a pivotal escalation, convening 113 nations and resulting in the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) headquartered in Nairobi, which coordinated global monitoring of resource depletion and pollution, leading to 26 conventions on biodiversity and chemicals by the 1980s.[58] This conference shifted conservation from ad hoc national initiatives to multilateral frameworks, emphasizing empirical data on habitat loss—such as the documented 20-30% decline in global forest cover since 1950—and prompting integrated strategies like the 1980 World Conservation Strategy co-authored by IUCN, WWF, and UNEP, which advocated sustainable development to balance human needs with ecosystem integrity.[54] By the late 1970s, these efforts had fostered over 3,000 international protected areas, reflecting conservation's transition to a worldwide imperative driven by scientific consensus on overexploitation risks.[59]Developments Since 1970

The conservation movement gained renewed institutional momentum in the 1970s, catalyzed by widespread public awareness following the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970, which mobilized an estimated 20 million participants across the United States to advocate for resource protection and pollution control.[60] This grassroots surge prompted key U.S. legislation, including the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which established federal authority to protect imperiled species and habitats through listing, recovery plans, and habitat safeguards, ultimately preventing the extinction of hundreds of taxa.[61] Internationally, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), adopted in 1973, regulated commercial trade in over 38,000 species to curb poaching and overexploitation, with enforcement leading to documented declines in illegal trafficking for species like African elephants and rhinos.[62] The decade also saw foundational global frameworks emerge from the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, which established the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) to coordinate biodiversity efforts and highlighted resource depletion as a planetary concern.[63] Complementary treaties included the 1971 Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, designating over 2,500 sites covering 250 million hectares by 2023 for habitat conservation, and the 1972 World Heritage Convention, which by the 1980s expanded protections to natural sites emphasizing ecological integrity over purely cultural value.[63] These instruments shifted conservation from national silos to multilateral cooperation, though implementation varied due to enforcement challenges in developing nations reliant on resource extraction. By the 1980s and 1990s, the movement integrated sustainable use principles, as articulated in the 1987 Brundtland Report's definition of sustainable development—meeting present needs without compromising future generations—which influenced policies balancing economic growth with ecosystem maintenance.[17] The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), ratified by 196 parties, set targets for genetic resource access, habitat preservation, and biotechnology benefits-sharing, spurring national biodiversity strategies and the expansion of protected areas from about 3% of global land in 1970 to over 17% by 2020.[64] Conservation biology emerged as a formal discipline in 1978, led by Michael Soulé's synthesis of ecology, genetics, and policy to address extinction risks empirically, fostering data-driven interventions like population viability analysis.[65] Post-2000 developments emphasized measurable outcomes, including the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) documenting habitat loss drivers and recoveries, and the REDD+ mechanism under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, which by 2020 incentivized forest conservation in tropical nations through carbon credit payments, reducing deforestation rates in participating areas like the Brazilian Amazon by up to 80% from peak levels.[66] Empirical successes included delistings under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, such as the American alligator (delisted 1987 after population rebound from <100,000 to over 1 million via regulated harvesting) and the bald eagle (delisted 2007 following pesticide bans and nesting protections that tripled continental numbers).[67] Globally, community-based models in Africa and Asia, like Namibia's conservancies granting locals wildlife management rights since 1990, boosted elephant populations by 400% in some regions through anti-poaching incentives tied to tourism revenue.[68] Despite these advances, ongoing threats like habitat fragmentation underscore the need for adaptive, evidence-based strategies over ideological prescriptions.[69]Key Figures and Organizations

Pioneering Thinkers and Activists