Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dynamic random-access memory

View on Wikipedia

| Computer memory and data storage types |

|---|

| Volatile |

| Non-volatile |

Dynamic random-access memory (dynamic RAM or DRAM) is a type of random-access semiconductor memory that stores each bit of data in a memory cell, usually consisting of a tiny capacitor and a transistor, both typically based on metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) technology. While most DRAM memory cell designs use a capacitor and transistor, some only use two transistors. In the designs where a capacitor is used, the capacitor can either be charged or discharged; these two states are taken to represent the two values of a bit, conventionally called 0 and 1. The electric charge on the capacitors gradually leaks away; without intervention the data on the capacitor would soon be lost. To prevent this, DRAM requires an external memory refresh circuit which periodically rewrites the data in the capacitors, restoring them to their original charge. This refresh process is the defining characteristic of dynamic random-access memory, in contrast to static random-access memory (SRAM) which does not require data to be refreshed. Unlike flash memory, DRAM is volatile memory (as opposed to non-volatile memory), since it loses its data quickly when power is removed. However, DRAM does exhibit limited data remanence.

DRAM typically takes the form of an integrated circuit chip, which can consist of dozens to billions of DRAM memory cells. DRAM chips are widely used in digital electronics where low-cost and high-capacity computer memory is required. One of the largest applications for DRAM is the main memory (colloquially called the RAM) in modern computers and graphics cards (where the main memory is called the graphics memory). It is also used in many portable devices and video game consoles. In contrast, SRAM, which is faster and more expensive than DRAM, is typically used where speed is of greater concern than cost and size, such as the cache memories in processors.

The need to refresh DRAM demands more complicated circuitry and timing than SRAM. This complexity is offset by the structural simplicity of DRAM memory cells: only one transistor and a capacitor are required per bit, compared to four or six transistors in SRAM. This allows DRAM to reach very high densities with a simultaneous reduction in cost per bit. Refreshing the data consumes power, causing a variety of techniques to be used to manage the overall power consumption. For this reason, DRAM usually needs to operate with a memory controller; the memory controller needs to know DRAM parameters, especially memory timings, to initialize DRAMs, which may be different depending on different DRAM manufacturers and part numbers.

DRAM had a 47% increase in the price-per-bit in 2017, the largest jump in 30 years since the 45% jump in 1988, while in recent years the price has been going down.[3] In 2018, a "key characteristic of the DRAM market is that there are currently only three major suppliers — Micron Technology, SK Hynix and Samsung Electronics" that are "keeping a pretty tight rein on their capacity".[4] There is also Kioxia (previously Toshiba Memory Corporation after 2017 spin-off) which doesn't manufacture DRAM. Other manufacturers make and sell DIMMs (but not the DRAM chips in them), such as Kingston Technology, and some manufacturers that sell stacked DRAM (used e.g. in the fastest supercomputers on the exascale), separately such as Viking Technology. Others sell such integrated into other products, such as Fujitsu into its CPUs, AMD in GPUs, and Nvidia, with HBM2 in some of their GPU chips.

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]

The cryptanalytic machine code-named Aquarius used at Bletchley Park during World War II incorporated a hard-wired dynamic memory. Paper tape was read and the characters on it "were remembered in a dynamic store." The store used a large bank of capacitors, which were either charged or not, a charged capacitor representing cross (1) and an uncharged capacitor dot (0). Since the charge gradually leaked away, a periodic pulse was applied to top up those still charged (hence the term 'dynamic')".[5]

In November 1965, Toshiba introduced a bipolar dynamic RAM for its electronic calculator Toscal BC-1411.[6][7][8] In 1966, Tomohisa Yoshimaru and Hiroshi Komikawa from Toshiba applied for a Japanese patent of a memory circuit composed of several transistors and a capacitor, in 1967 they applied for a patent in the US.[9]

The earliest forms of DRAM mentioned above used bipolar transistors. While it offered improved performance over magnetic-core memory, bipolar DRAM could not compete with the lower price of the then-dominant magnetic-core memory.[10] Capacitors had also been used for earlier memory schemes, such as the drum of the Atanasoff–Berry Computer, the Williams tube and the Selectron tube.

Single MOS DRAM

[edit]In 1966, Dr. Robert Dennard invented modern DRAM architecture in which there's a single MOS transistor per capacitor,[11] at the IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Center, while he was working on MOS memory and was trying to create an alternative to SRAM which required six MOS transistors for each bit of data. While examining the characteristics of MOS technology, he found it was capable of building capacitors, and that storing a charge or no charge on the MOS capacitor could represent the 1 and 0 of a bit, while the MOS transistor could control writing the charge to the capacitor. This led to his development of the single-transistor MOS DRAM memory cell.[12] He filed a patent in 1967, and was granted U.S. patent number 3,387,286 in 1968.[13] MOS memory offered higher performance, was cheaper, and consumed less power, than magnetic-core memory.[14] The patent describes the invention: "Each cell is formed, in one embodiment, using a single field-effect transistor and a single capacitor."[15]

MOS DRAM chips were commercialized in 1969 by Advanced Memory Systems, Inc of Sunnyvale, CA. This 1024 bit chip was sold to Honeywell, Raytheon, Wang Laboratories, and others. The same year, Honeywell asked Intel to make a DRAM using a three-transistor cell that they had developed. This became the Intel 1102 in early 1970.[16] However, the 1102 had many problems, prompting Intel to begin work on their own improved design, in secrecy to avoid conflict with Honeywell. This became the first commercially available DRAM, the Intel 1103, in October 1970, despite initial problems with low yield until the fifth revision of the masks. The 1103 was designed by Joel Karp and laid out by Pat Earhart. The masks were cut by Barbara Maness and Judy Garcia.[17][original research?] MOS memory overtook magnetic-core memory as the dominant memory technology in the early 1970s.[14]

The first DRAM with multiplexed row and column address lines was the Mostek MK4096 4 Kbit DRAM designed by Robert Proebsting and introduced in 1973. This addressing scheme uses the same address pins to receive the low half and the high half of the address of the memory cell being referenced, switching between the two halves on alternating bus cycles. This was a radical advance, effectively halving the number of address lines required, which enabled it to fit into packages with fewer pins, a cost advantage that grew with every jump in memory size. The MK4096 proved to be a very robust design for customer applications. At the 16 Kbit density, the cost advantage increased; the 16 Kbit Mostek MK4116 DRAM,[18][19] introduced in 1976, achieved greater than 75% worldwide DRAM market share. However, as density increased to 64 Kbit in the early 1980s, Mostek and other US manufacturers were overtaken by Japanese DRAM manufacturers, which dominated the US and worldwide markets during the 1980s and 1990s.

Early in 1985, Gordon Moore decided to withdraw Intel from producing DRAM.[20] By 1986, many, but not all, United States chip makers had stopped making DRAMs.[21] Micron Technology and Texas Instruments continued to produce them commercially, and IBM produced them for internal use.

In 1985, when 64K DRAM memory chips were the most common memory chips used in computers, and when more than 60 percent of those chips were produced by Japanese companies, semiconductor makers in the United States accused Japanese companies of export dumping for the purpose of driving makers in the United States out of the commodity memory chip business. Prices for the 64K product plummeted to as low as 35 cents apiece from $3.50 within 18 months, with disastrous financial consequences for some U.S. firms. On 4 December 1985 the US Commerce Department's International Trade Administration ruled in favor of the complaint.[22][23][24][25]

Synchronous dynamic random-access memory (SDRAM) was developed by Samsung. The first commercial SDRAM chip was the Samsung KM48SL2000, which had a capacity of 16 Mb,[26] and was introduced in 1992.[27] The first commercial DDR SDRAM (double data rate SDRAM) memory chip was Samsung's 64 Mb DDR SDRAM chip, released in 1998.[28]

Later, in 2001, Japanese DRAM makers accused Korean DRAM manufacturers of dumping.[29][30][31][32]

In 2002, US computer makers made claims of DRAM price fixing.

Principles of operation

[edit]

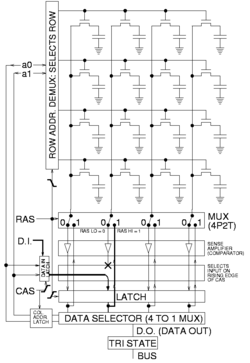

DRAM is usually arranged in a rectangular array of charge storage cells consisting of one capacitor and transistor per data bit. The figure to the right shows a simple example with a four-by-four cell matrix. Some DRAM matrices are many thousands of cells in height and width.[33][34]

The long horizontal lines connecting each row are known as word-lines. Each column of cells is composed of two bit-lines, each connected to every other storage cell in the column (the illustration to the right does not include this important detail). They are generally known as the + and − bit lines.

A sense amplifier is essentially a pair of cross-connected inverters between the bit-lines. The first inverter is connected with input from the + bit-line and output to the − bit-line. The second inverter's input is from the − bit-line with output to the + bit-line. This results in positive feedback which stabilizes after one bit-line is fully at its highest voltage and the other bit-line is at the lowest possible voltage.

Operations to read a data bit from a DRAM storage cell

[edit]- The sense amplifiers are disconnected.[35]

- The bit-lines are precharged to exactly equal voltages that are in between high and low logic levels (e.g., 0.5 V if the two levels are 0 and 1 V). The bit-lines are physically symmetrical to keep the capacitance equal, and therefore at this time their voltages are equal.[35]

- The precharge circuit is switched off. Because the bit-lines are relatively long, they have enough capacitance to maintain the precharged voltage for a brief time. This is an example of dynamic logic.[35]

- The desired row's word-line is then driven high to connect a cell's storage capacitor to its bit-line. This causes the transistor to conduct, transferring charge from the storage cell to the connected bit-line (if the stored value is 1) or from the connected bit-line to the storage cell (if the stored value is 0). Since the capacitance of the bit-line is typically much higher than the capacitance of the storage cell, the voltage on the bit-line increases very slightly if the storage cell's capacitor is discharged and decreases very slightly if the storage cell is charged (e.g., 0.54 and 0.45 V in the two cases). As the other bit-line holds 0.50 V there is a small voltage difference between the two twisted bit-lines.[35]

- The sense amplifiers are now connected to the bit-lines pairs. Positive feedback then occurs from the cross-connected inverters, thereby amplifying the small voltage difference between the odd and even row bit-lines of a particular column until one bit line is fully at the lowest voltage and the other is at the maximum high voltage. Once this has happened, the row is open (the desired cell data is available).[35]

- All storage cells in the open row are sensed simultaneously, and the sense amplifier outputs latched. A column address then selects which latch bit to connect to the external data bus. Reads of different columns in the same row can be performed without a row opening delay because, for the open row, all data has already been sensed and latched.[35]

- While reading of columns in an open row is occurring, current is flowing back up the bit-lines from the output of the sense amplifiers and recharging the storage cells. This reinforces (i.e. refreshes) the charge in the storage cell by increasing the voltage in the storage capacitor if it was charged to begin with, or by keeping it discharged if it was empty. Note that due to the length of the bit-lines there is a fairly long propagation delay for the charge to be transferred back to the cell's capacitor. This takes significant time past the end of sense amplification, and thus overlaps with one or more column reads.[35]

- When done with reading all the columns in the current open row, the word-line is switched off to disconnect the storage cell capacitors (the row is closed) from the bit-lines. The sense amplifier is switched off, and the bit-lines are precharged again.[35]

To write to memory

[edit]

To store data, a row is opened and a given column's sense amplifier is temporarily forced to the desired high or low-voltage state, thus causing the bit-line to charge or discharge the cell storage capacitor to the desired value. Due to the sense amplifier's positive feedback configuration, it will hold a bit-line at stable voltage even after the forcing voltage is removed. During a write to a particular cell, all the columns in a row are sensed simultaneously just as during reading, so although only a single column's storage-cell capacitor charge is changed, the entire row is refreshed (written back in), as illustrated in the figure to the right.[35]

Refresh rate

[edit]Typically, manufacturers specify that each row must be refreshed every 64 ms or less, as defined by the JEDEC standard.

Some systems refresh every row in a burst of activity involving all rows every 64 ms. Other systems refresh one row at a time staggered throughout the 64 ms interval. For example, a system with 213 = 8,192 rows would require a staggered refresh rate of one row every 7.8 μs which is 64 ms divided by 8,192 rows. A few real-time systems refresh a portion of memory at a time determined by an external timer function that governs the operation of the rest of a system, such as the vertical blanking interval that occurs every 10–20 ms in video equipment.

The row address of the row that will be refreshed next is maintained by external logic or a counter within the DRAM. A system that provides the row address (and the refresh command) does so to have greater control over when to refresh and which row to refresh. This is done to minimize conflicts with memory accesses, since such a system has both knowledge of the memory access patterns and the refresh requirements of the DRAM. When the row address is supplied by a counter within the DRAM, the system relinquishes control over which row is refreshed and only provides the refresh command. Some modern DRAMs are capable of self-refresh; no external logic is required to instruct the DRAM to refresh or to provide a row address.

Under some conditions, most of the data in DRAM can be recovered even if the DRAM has not been refreshed for several minutes.[36]

Memory timing

[edit]Many parameters are required to fully describe the timing of DRAM operation. Here are some examples for two timing grades of asynchronous DRAM, from a data sheet published in 1998:[37]

| "50 ns" | "60 ns" | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| tRC | 84 ns | 104 ns | Random read or write cycle time (from one full /RAS cycle to another) |

| tRAC | 50 ns | 60 ns | Access time: /RAS low to valid data out |

| tRCD | 11 ns | 14 ns | /RAS low to /CAS low time |

| tRAS | 50 ns | 60 ns | /RAS pulse width (minimum /RAS low time) |

| tRP | 30 ns | 40 ns | /RAS precharge time (minimum /RAS high time) |

| tPC | 20 ns | 25 ns | Page-mode read or write cycle time (/CAS to /CAS) |

| tAA | 25 ns | 30 ns | Access time: Column address valid to valid data out (includes address setup time before /CAS low) |

| tCAC | 13 ns | 15 ns | Access time: /CAS low to valid data out |

| tCAS | 8 ns | 10 ns | /CAS low pulse width minimum |

Thus, the generally quoted number is the /RAS low to valid data out time. This is the time to open a row, settle the sense amplifiers, and deliver the selected column data to the output. This is also the minimum /RAS low time, which includes the time for the amplified data to be delivered back to recharge the cells. The time to read additional bits from an open page is much less, defined by the /CAS to /CAS cycle time. The quoted number is the clearest way to compare between the performance of different DRAM memories, as it sets the slower limit regardless of the row length or page size. Bigger arrays forcibly result in larger bit line capacitance and longer propagation delays, which cause this time to increase as the sense amplifier settling time is dependent on both the capacitance as well as the propagation latency. This is countered in modern DRAM chips by instead integrating many more complete DRAM arrays within a single chip, to accommodate more capacity without becoming too slow.

When such a RAM is accessed by clocked logic, the times are generally rounded up to the nearest clock cycle. For example, when accessed by a 100 MHz state machine (i.e. a 10 ns clock), the 50 ns DRAM can perform the first read in five clock cycles, and additional reads within the same page every two clock cycles. This was generally described as "5-2-2-2" timing, as bursts of four reads within a page were common.

When describing synchronous memory, timing is described by clock cycle counts separated by hyphens. These numbers represent tCL-tRCD-tRP-tRAS in multiples of the DRAM clock cycle time. Note that this is half of the data transfer rate when double data rate signaling is used. JEDEC standard PC3200 timing is 3-4-4-8[38] with a 200 MHz clock, while premium-priced high performance PC3200 DDR DRAM DIMM might be operated at 2-2-2-5 timing.[39]

| PC-3200 (DDR-400) | PC2-6400 (DDR2-800) | PC3-12800 (DDR3-1600) | Description | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cycles | time | cycles | time | cycles | time | |||

| tCL | Typical | 3 | 15 ns | 5 | 12.5 ns | 9 | 11.25 ns | /CAS low to valid data out (equivalent to tCAC) |

| Fast | 2 | 10 ns | 4 | 10 ns | 8 | 10 ns | ||

| tRCD | Typical | 4 | 20 ns | 5 | 12.5 ns | 9 | 11.25 ns | /RAS low to /CAS low time |

| Fast | 2 | 10 ns | 4 | 10 ns | 8 | 10 ns | ||

| tRP | Typical | 4 | 20 ns | 5 | 12.5 ns | 9 | 11.25 ns | /RAS precharge time (minimum precharge to active time) |

| Fast | 2 | 10 ns | 4 | 10 ns | 8 | 10 ns | ||

| tRAS | Typical | 8 | 40 ns | 16 | 40 ns | 27 | 33.75 ns | Row active time (minimum active to precharge time) |

| Fast | 5 | 25 ns | 12 | 30 ns | 24 | 30 ns | ||

Minimum random access time has improved from tRAC = 50 ns to tRCD + tCL = 22.5 ns, and even the premium 20 ns variety is only 2.5 times faster than the asynchronous DRAM. CAS latency has improved even less, from tCAC = 13 ns to 10 ns. However, the DDR3 memory does achieve 32 times higher bandwidth; due to internal pipelining and wide data paths, it can output two words every 1.25 ns (1600 Mword/s), while the EDO DRAM can output one word per tPC = 20 ns (50 Mword/s).

Timing abbreviations

[edit]

|

|

Memory cell design

[edit]Each bit of data in a DRAM is stored as a positive or negative electrical charge in a capacitive structure. The structure providing the capacitance, as well as the transistors that control access to it, is collectively referred to as a DRAM cell. They are the fundamental building block in DRAM arrays. Multiple DRAM memory cell variants exist, but the most commonly used variant in modern DRAMs is the one-transistor, one-capacitor (1T1C) cell. The transistor is used to admit current into the capacitor during writes, and to discharge the capacitor during reads. The access transistor is designed to maximize drive strength and minimize transistor-transistor leakage (Kenner, p. 34).

The capacitor has two terminals, one of which is connected to its access transistor, and the other to either ground or VCC/2. In modern DRAMs, the latter case is more common, since it allows faster operation. In modern DRAMs, a voltage of +VCC/2 across the capacitor is required to store a logic one; and a voltage of −VCC/2 across the capacitor is required to store a logic zero. The resultant charge is , where Q is the charge in coulombs and C is the capacitance in farads.[40]

Reading or writing a logic one requires the wordline be driven to a voltage greater than the sum of VCC and the access transistor's threshold voltage (VTH). This voltage is called VCC pumped (VCCP). The time required to discharge a capacitor thus depends on what logic value is stored in the capacitor. A capacitor containing logic one begins to discharge when the voltage at the access transistor's gate terminal is above VCCP. If the capacitor contains a logic zero, it begins to discharge when the gate terminal voltage is above VTH.[41]

Capacitor design

[edit]Up until the mid-1980s, the capacitors in DRAM cells were co-planar with the access transistor (they were constructed on the surface of the substrate), thus they were referred to as planar capacitors. The drive to increase both density and, to a lesser extent, performance, required denser designs. This was strongly motivated by economics, a major consideration for DRAM devices, especially commodity DRAMs. The minimization of DRAM cell area can produce a denser device and lower the cost per bit of storage. Starting in the mid-1980s, the capacitor was moved above or below the silicon substrate in order to meet these objectives. DRAM cells featuring capacitors above the substrate are referred to as stacked or folded plate capacitors. Those with capacitors buried beneath the substrate surface are referred to as trench capacitors. In the 2000s, manufacturers were sharply divided by the type of capacitor used in their DRAMs and the relative cost and long-term scalability of both designs have been the subject of extensive debate. The majority of DRAMs, from major manufactures such as Hynix, Micron Technology, Samsung Electronics use the stacked capacitor structure, whereas smaller manufacturers such Nanya Technology use the trench capacitor structure (Jacob, pp. 355–357).

The capacitor in the stacked capacitor scheme is constructed above the surface of the substrate. The capacitor is constructed from an oxide-nitride-oxide (ONO) dielectric sandwiched in between two layers of polysilicon plates (the top plate is shared by all DRAM cells in an IC), and its shape can be a rectangle, a cylinder, or some other more complex shape. There are two basic variations of the stacked capacitor, based on its location relative to the bitline—capacitor-under-bitline (CUB) and capacitor-over-bitline (COB). In the former, the capacitor is underneath the bitline, which is usually made of metal, and the bitline has a polysilicon contact that extends downwards to connect it to the access transistor's source terminal. In the latter, the capacitor is constructed above the bitline, which is almost always made of polysilicon, but is otherwise identical to the COB variation. The advantage the COB variant possesses is the ease of fabricating the contact between the bitline and the access transistor's source as it is physically close to the substrate surface. However, this requires the active area to be laid out at a 45-degree angle when viewed from above, which makes it difficult to ensure that the capacitor contact does not touch the bitline. CUB cells avoid this, but suffer from difficulties in inserting contacts in between bitlines, since the size of features this close to the surface are at or near the minimum feature size of the process technology (Kenner, pp. 33–42).

The trench capacitor is constructed by etching a deep hole into the silicon substrate. The substrate volume surrounding the hole is then heavily doped to produce a buried n+ plate with low resistance. A layer of oxide-nitride-oxide dielectric is grown or deposited, and finally the hole is filled by depositing doped polysilicon, which forms the top plate of the capacitor. The top of the capacitor is connected to the access transistor's drain terminal via a polysilicon strap (Kenner, pp. 42–44). A trench capacitor's depth-to-width ratio in DRAMs of the mid-2000s can exceed 50:1 (Jacob, p. 357).

Trench capacitors have numerous advantages. Since the capacitor is buried in the bulk of the substrate instead of lying on its surface, the area it occupies can be minimized to what is required to connect it to the access transistor's drain terminal without decreasing the capacitor's size, and thus capacitance (Jacob, pp. 356–357). Alternatively, the capacitance can be increased by etching a deeper hole without any increase to surface area (Kenner, p. 44). Another advantage of the trench capacitor is that its structure is under the layers of metal interconnect, allowing them to be more easily made planar, which enables it to be integrated in a logic-optimized process technology, which have many levels of interconnect above the substrate. The fact that the capacitor is under the logic means that it is constructed before the transistors are. This allows high-temperature processes to fabricate the capacitors, which would otherwise degrade the logic transistors and their performance. This makes trench capacitors suitable for constructing embedded DRAM (eDRAM) (Jacob, p. 357). Disadvantages of trench capacitors are difficulties in reliably constructing the capacitor's structures within deep holes and in connecting the capacitor to the access transistor's drain terminal (Kenner, p. 44).

Historical cell designs

[edit]First-generation DRAM ICs (those with capacities of 1 Kbit), such as the archetypical Intel 1103, used a three-transistor, one-capacitor (3T1C) DRAM cell with separate read and write circuitry. The write wordline drove a write transistor which connected the capacitor to the write bitline just as in the 1T1C cell, but there was a separate read wordline and read transistor which connected an amplifier transistor to the read bitline. By the second generation, the drive to reduce cost by fitting the same amount of bits in a smaller area led to the almost universal adoption of the 1T1C DRAM cell, although a couple of devices with 4 and 16 Kbit capacities continued to use the 3T1C cell for performance reasons (Kenner, p. 6). These performance advantages included, most significantly, the ability to read the state stored by the capacitor without discharging it, avoiding the need to write back what was read out (non-destructive read). A second performance advantage relates to the 3T1C cell's separate transistors for reading and writing; the memory controller can exploit this feature to perform atomic read-modify-writes, where a value is read, modified, and then written back as a single, indivisible operation (Jacob, p. 459).

Proposed cell designs

[edit]The one-transistor, zero-capacitor (1T, or 1T0C) DRAM cell has been a topic of research since the late-1990s. 1T DRAM is a different way of constructing the basic DRAM memory cell, distinct from the classic one-transistor/one-capacitor (1T/1C) DRAM cell, which is also sometimes referred to as 1T DRAM, particularly in comparison to the 3T and 4T DRAM which it replaced in the 1970s.

In 1T DRAM cells, the bit of data is still stored in a capacitive region controlled by a transistor, but this capacitance is no longer provided by a separate capacitor. 1T DRAM is a "capacitorless" bit cell design that stores data using the parasitic body capacitance that is inherent to silicon on insulator (SOI) transistors. Considered a nuisance in logic design, this floating body effect can be used for data storage. This gives 1T DRAM cells the greatest density as well as allowing easier integration with high-performance logic circuits since they are constructed with the same SOI process technologies.[42]

Refreshing of cells remains necessary, but unlike with 1T1C DRAM, reads in 1T DRAM are non-destructive; the stored charge causes a detectable shift in the threshold voltage of the transistor.[43] Performance-wise, access times are significantly better than capacitor-based DRAMs, but slightly worse than SRAM. There are several types of 1T DRAMs: the commercialized Z-RAM from Innovative Silicon, the TTRAM[44] from Renesas and the A-RAM from the UGR/CNRS consortium.

Array structures

[edit]

DRAM cells are laid out in a regular rectangular, grid-like pattern to facilitate their control and access via wordlines and bitlines. The physical layout of the DRAM cells in an array is typically designed so that two adjacent DRAM cells in a column share a single bitline contact to reduce their area. DRAM cell area is given as nF2, where n is a number derived from the DRAM cell design, and F is the smallest feature size of a given process technology. This scheme permits comparison of DRAM size over different process technology generations, as DRAM cell area scales at linear or near-linear rates with respect to feature size. The typical area for modern DRAM cells varies between 6–8 F2.

The horizontal wire, the wordline, is connected to the gate terminal of every access transistor in its row. The vertical bitline is connected to the source terminal of the transistors in its column. The lengths of the wordlines and bitlines are limited. The wordline length is limited by the desired performance of the array, since propagation time of the signal that must transverse the wordline is determined by the RC time constant. The bitline length is limited by its capacitance (which increases with length), which must be kept within a range for proper sensing (as DRAMs operate by sensing the charge of the capacitor released onto the bitline). Bitline length is also limited by the amount of operating current the DRAM can draw and by how power can be dissipated, since these two characteristics are largely determined by the charging and discharging of the bitline.

Bitline architecture

[edit]Sense amplifiers are required to read the state contained in the DRAM cells. When the access transistor is activated, the electrical charge in the capacitor is shared with the bitline. The bitline's capacitance is much greater than that of the capacitor (approximately ten times). Thus, the change in bitline voltage is minute. Sense amplifiers are required to resolve the voltage differential into the levels specified by the logic signaling system. Modern DRAMs use differential sense amplifiers, and are accompanied by requirements as to how the DRAM arrays are constructed. Differential sense amplifiers work by driving their outputs to opposing extremes based on the relative voltages on pairs of bitlines. The sense amplifiers function effectively and efficient only if the capacitance and voltages of these bitline pairs are closely matched. Besides ensuring that the lengths of the bitlines and the number of attached DRAM cells attached to them are equal, two basic architectures to array design have emerged to provide for the requirements of the sense amplifiers: open and folded bitline arrays.

Open bitline arrays

[edit]The first generation (1 Kbit) DRAM ICs, up until the 64 Kbit generation (and some 256 Kbit generation devices) had open bitline array architectures. In these architectures, the bitlines are divided into multiple segments, and the differential sense amplifiers are placed in between bitline segments. Because the sense amplifiers are placed between bitline segments, to route their outputs outside the array, an additional layer of interconnect placed above those used to construct the wordlines and bitlines is required.

The DRAM cells that are on the edges of the array do not have adjacent segments. Since the differential sense amplifiers require identical capacitance and bitline lengths from both segments, dummy bitline segments are provided. The advantage of the open bitline array is a smaller array area, although this advantage is slightly diminished by the dummy bitline segments. The disadvantage that caused the near disappearance of this architecture is the inherent vulnerability to noise, which affects the effectiveness of the differential sense amplifiers. Since each bitline segment does not have any spatial relationship to the other, it is likely that noise would affect only one of the two bitline segments.

Folded bitline arrays

[edit]The folded bitline array architecture routes bitlines in pairs throughout the array. The close proximity of the paired bitlines provide superior common-mode noise rejection characteristics over open bitline arrays. The folded bitline array architecture began appearing in DRAM ICs during the mid-1980s, beginning with the 256 Kbit generation. This architecture is favored in modern DRAM ICs for its superior noise immunity.

This architecture is referred to as folded because it takes its basis from the open array architecture from the perspective of the circuit schematic. The folded array architecture appears to remove DRAM cells in alternate pairs (because two DRAM cells share a single bitline contact) from a column, then move the DRAM cells from an adjacent column into the voids.

The location where the bitline twists occupies additional area. To minimize area overhead, engineers select the simplest and most area-minimal twisting scheme that is able to reduce noise under the specified limit. As process technology improves to reduce minimum feature sizes, the signal to noise problem worsens, since coupling between adjacent metal wires is inversely proportional to their pitch. The array folding and bitline twisting schemes that are used must increase in complexity in order to maintain sufficient noise reduction. Schemes that have desirable noise immunity characteristics for a minimal impact in area is the topic of current research (Kenner, p. 37).

Future array architectures

[edit]Advances in process technology could result in open bitline array architectures being favored if it is able to offer better long-term area efficiencies; since folded array architectures require increasingly complex folding schemes to match any advance in process technology. The relationship between process technology, array architecture, and area efficiency is an active area of research.

Row and column redundancy

[edit]The first DRAM integrated circuits did not have any redundancy. An integrated circuit with a defective DRAM cell would be discarded. Beginning with the 64 Kbit generation, DRAM arrays have included spare rows and columns to improve yields. Spare rows and columns provide tolerance of minor fabrication defects which have caused a small number of rows or columns to be inoperable. The defective rows and columns are physically disconnected from the rest of the array by a triggering a programmable fuse or by cutting the wire by a laser. The spare rows or columns are substituted in by remapping logic in the row and column decoders (Jacob, pp. 358–361).

Error detection and correction

[edit]Electrical or magnetic interference inside a computer system can cause a single bit of DRAM to spontaneously flip to the opposite state. The majority of one-off ("soft") errors in DRAM chips occur as a result of background radiation, chiefly neutrons from cosmic ray secondaries, which may change the contents of one or more memory cells or interfere with the circuitry used to read/write them.

The problem can be mitigated by using redundant memory bits and additional circuitry that use these bits to detect and correct soft errors. In most cases, the detection and correction are performed by the memory controller; sometimes, the required logic is transparently implemented within DRAM chips or modules, enabling the ECC memory functionality for otherwise ECC-incapable systems.[46] The extra memory bits are used to record parity and to enable missing data to be reconstructed by error-correcting code (ECC). Parity allows the detection of all single-bit errors (actually, any odd number of wrong bits). The most common error-correcting code, a SECDED Hamming code, allows a single-bit error to be corrected and, in the usual configuration, with an extra parity bit, double-bit errors to be detected.[47]

Recent studies give widely varying error rates with over seven orders of magnitude difference, ranging from 10−10−10−17 error/bit·h, roughly one bit error, per hour, per gigabyte of memory to one bit error, per century, per gigabyte of memory.[48][49][50] The Schroeder et al. 2009 study reported a 32% chance that a given computer in their study would suffer from at least one correctable error per year, and provided evidence that most such errors are intermittent hard rather than soft errors and that trace amounts of radioactive material that had gotten into the chip packaging were emitting alpha particles and corrupting the data.[51] A 2010 study at the University of Rochester also gave evidence that a substantial fraction of memory errors are intermittent hard errors.[52] Large scale studies on non-ECC main memory in PCs and laptops suggest that undetected memory errors account for a substantial number of system failures: the 2011 study reported a 1-in-1700 chance per 1.5% of memory tested (extrapolating to an approximately 26% chance for total memory) that a computer would have a memory error every eight months.[53]

Security

[edit]Data remanence

[edit]Although dynamic memory is only specified and guaranteed to retain its contents when supplied with power and refreshed every short period of time (often 64 ms), the memory cell capacitors often retain their values for significantly longer time, particularly at low temperatures.[54] Under some conditions most of the data in DRAM can be recovered even if it has not been refreshed for several minutes.[55]

This property can be used to circumvent security and recover data stored in the main memory that is assumed to be destroyed at power-down. The computer could be quickly rebooted, and the contents of the main memory read out; or by removing a computer's memory modules, cooling them to prolong data remanence, then transferring them to a different computer to be read out. Such an attack was demonstrated to circumvent popular disk encryption systems, such as the open source TrueCrypt, Microsoft's BitLocker Drive Encryption, and Apple's FileVault.[54] This type of attack against a computer is often called a cold boot attack.

Memory corruption

[edit]Dynamic memory, by definition, requires periodic refresh. Furthermore, reading dynamic memory is a destructive operation, requiring a recharge of the storage cells in the row that has been read. If these processes are imperfect, a read operation can cause soft errors. In particular, there is a risk that some charge can leak between nearby cells, causing the refresh or read of one row to cause a disturbance error in an adjacent or even nearby row. The awareness of disturbance errors dates back to the first commercially available DRAM in the early 1970s (the Intel 1103). Despite the mitigation techniques employed by manufacturers, commercial researchers proved in a 2014 analysis that commercially available DDR3 DRAM chips manufactured in 2012 and 2013 are susceptible to disturbance errors.[56] The associated side effect that led to observed bit flips has been dubbed row hammer.

Packaging

[edit]Memory module

[edit]Dynamic RAM ICs can be packaged in molded epoxy cases, with an internal lead frame for interconnections between the silicon die and the package leads. The original IBM PC design used ICs, including those for DRAM, packaged in dual in-line packages (DIP), soldered directly to the main board or mounted in sockets. As memory density skyrocketed, the DIP package was no longer practical. For convenience in handling, several dynamic RAM integrated circuits may be mounted on a single memory module, allowing installation of 16-bit, 32-bit or 64-bit wide memory in a single unit, without the requirement for the installer to insert multiple individual integrated circuits. Memory modules may include additional devices for parity checking or error correction. Over the evolution of desktop computers, several standardized types of memory module have been developed. Laptop computers, game consoles, and specialized devices may have their own formats of memory modules not interchangeable with standard desktop parts for packaging or proprietary reasons.

Embedded

[edit]DRAM that is integrated into an integrated circuit designed in a logic-optimized process (such as an application-specific integrated circuit, microprocessor, or an entire system on a chip) is called embedded DRAM (eDRAM). Embedded DRAM requires DRAM cell designs that can be fabricated without preventing the fabrication of fast-switching transistors used in high-performance logic, and modification of the basic logic-optimized process technology to accommodate the process steps required to build DRAM cell structures.

Versions

[edit]Since the fundamental DRAM cell and array has maintained the same basic structure for many years, the types of DRAM are mainly distinguished by the many different interfaces for communicating with DRAM chips.

Asynchronous DRAM

[edit]The original DRAM, now known by the retronym asynchronous DRAM was the first type of DRAM in use. From its origins in the late 1960s, it was commonplace in computing up until around 1997, when it was mostly replaced by synchronous DRAM. In the present day, manufacture of asynchronous RAM is relatively rare.[57]

Principles of operation

[edit]An asynchronous DRAM chip has power connections, some number of address inputs (typically 12), and a few (typically one or four) bidirectional data lines. There are three main active-low control signals:

- RAS, the Row Address Strobe. The address inputs are captured on the falling edge of RAS, and select a row to open. The row is held open as long as RAS is low.

- CAS, the Column Address Strobe. The address inputs are captured on the falling edge of CAS, and select a column from the currently open row to read or write.

- WE, Write Enable. This signal determines whether a given falling edge of CAS is a read (if high) or write (if low). If low, the data inputs are also captured on the falling edge of CAS. If high, the data outputs are enabled by the falling edge of CAS and produce valid output after the internal access time.

This interface provides direct control of internal timing: when RAS is driven low, a CAS cycle must not be attempted until the sense amplifiers have sensed the memory state, and RAS must not be returned high until the storage cells have been refreshed. When RAS is driven high, it must be held high long enough for precharging to complete.

Although the DRAM is asynchronous, the signals are typically generated by a clocked memory controller, which limits their timing to multiples of the controller's clock cycle.

For completeness, we mention two other control signals which are not essential to DRAM operation, but are provided for the convenience of systems using DRAM:

- CS, Chip Select. When this is high, all other inputs are ignored. This makes it easy to build an array of DRAM chips which share the same control signals. Just as DRAM internally uses the word lines to select one row of storage cells connect to the shared bit lines and sense amplifiers, CS is used to select one row of DRAM chips to connect to the shared control, address, and data lines.

- OE, Output Enable. This is an additional signal that (if high) inhibits output on the data I/O pins, while allowing all other operations to proceed normally. In many applications, OE can be permanently connected low (output enabled whenever CS, RAS and CAS are low and WE is high), but in high-speed applications, judicious use of OE can prevent bus contention between two DRAM chips connected to the same data lines. For example, it is possible to have two interleaved memory banks sharing the address and data lines, but each having their own RAS, CAS, WE and OE connections. The memory controller can begin a read from the second bank while a read from the first bank is in progress, using the two OE signals to only permit one result to appear on the data bus at a time.

RAS-only refresh

[edit]Classic asynchronous DRAM is refreshed by opening each row in turn.

The refresh cycles are distributed across the entire refresh interval in such a way that all rows are refreshed within the required interval. To refresh one row of the memory array using RAS only refresh (ROR), the following steps must occur:

- The row address of the row to be refreshed must be applied at the address input pins.

- RAS must switch from high to low. CAS must remain high.

- At the end of the required amount of time, RAS must return high.

This can be done by supplying a row address and pulsing RAS low; it is not necessary to perform any CAS cycles. An external counter is needed to iterate over the row addresses in turn.[58] In some designs, the CPU handled RAM refresh. The Zilog Z80 is perhaps the best known example, as it has an internal row counter R which supplies the address for a special refresh cycle generated after each instruction fetch.[59] In other systems, especially home computers, refresh was handled by the video circuitry as a side effect of its periodic scan of the frame buffer.[60]

CAS before RAS refresh

[edit]For convenience, the counter was quickly incorporated into the DRAM chips themselves. If the CAS line is driven low before RAS (normally an illegal operation), then the DRAM ignores the address inputs and uses an internal counter to select the row to open.[58][61] This is known as CAS-before-RAS (CBR) refresh. This became the standard form of refresh for asynchronous DRAM, and is the only form generally used with SDRAM.

Hidden refresh

[edit]Given support of CAS-before-RAS refresh, it is possible to deassert RAS while holding CAS low to maintain data output. If RAS is then asserted again, this performs a CBR refresh cycle while the DRAM outputs remain valid. Because data output is not interrupted, this is known as hidden refresh.[61] Hidden refresh is no faster than a normal read followed by a normal refresh, but does maintain the data output valid during the refresh cycle.

Page mode DRAM

[edit]Page mode DRAM is a minor modification to the first-generation DRAM IC interface which improves the performance of reads and writes to a row by avoiding the inefficiency of precharging and opening the same row repeatedly to access a different column. In page mode DRAM, after a row is opened by holding RAS low, the row can be kept open, and multiple reads or writes can be performed to any of the columns in the row. Each column access is initiated by presenting a column address and asserting CAS. For reads, after a delay (tCAC), valid data appears on the data out pins, which are held at high-Z before the appearance of valid data. For writes, the write enable signal and write data is presented along with the column address.[62]

Page mode DRAM was in turn later improved with a small modification which further reduced latency. DRAMs with this improvement are called fast page mode DRAMs (FPM DRAMs). In page mode DRAM, the chip does not capture the column address until CAS is asserted, so column access time (until data out was valid) begins when CAS is asserted. In FPM DRAM, the column address can be supplied while CAS is still deasserted, and the main column access time (tAA) begins as soon as the address is stable. The CAS signal is only needed to enable the output (the data out pins were held at high-Z while CAS was deasserted), so time from CAS assertion to data valid (tCAC) is greatly reduced.[63] Fast page mode DRAM was introduced in 1986 and was used with the Intel 80486.

Static column is a variant of fast page mode in which the column address does not need to be latched, but rather the address inputs may be changed with CAS held low, and the data output will be updated accordingly a few nanoseconds later.[63]

Nibble mode is another variant in which four sequential locations within the row can be accessed with four consecutive pulses of CAS. The difference from normal page mode is that the address inputs are not used for the second through fourth CAS edges but are generated internally starting with the address supplied for the first CAS edge.[63] The predictable addresses let the chip prepare the data internally and respond very quickly to the subsequent CAS pulses.

Extended data out DRAM

[edit]

Extended data out DRAM (EDO DRAM) was invented and patented in the 1990s by Micron Technology who then licensed technology to many other memory manufacturers.[64] EDO RAM, sometimes referred to as hyper page mode enabled DRAM, is similar to fast page mode DRAM with the additional feature that a new access cycle can be started while keeping the data output of the previous cycle active. This allows a certain amount of overlap in operation (pipelining), allowing somewhat improved performance.[65] It is up to 30% faster than FPM DRAM,[66] which it began to replace in 1995 when Intel introduced the 430FX chipset with EDO DRAM support. Irrespective of the performance gains, FPM and EDO SIMMs can be used interchangeably in many (but not all) applications.[67][68]

To be precise, EDO DRAM begins data output on the falling edge of CAS but does not disable the output when CAS rises again. Instead, it holds the current output valid (thus extending the data output time) even as the DRAM begins decoding a new column address, until either a new column's data is selected by another CAS falling edge, or the output is switched off by the rising edge of RAS. (Or, less commonly, a change in CS, OE, or WE.)

This ability to start a new access even before the system has received the preceding column's data made it possible to design memory controllers which could carry out a CAS access (in the currently open row) in one clock cycle, or at least within two clock cycles instead of the previously required three. EDO's capabilities were able to partially compensate for the performance lost due to the lack of an L2 cache in low-cost, commodity PCs. More expensive notebooks also often lacked an L2 cache due to size and power limitations, and benefitted similarly. Even for systems with an L2 cache, the availability of EDO memory improved the average memory latency seen by applications over earlier FPM implementations.

Single-cycle EDO DRAM became very popular on video cards toward the end of the 1990s. It was very low cost, yet nearly as efficient for performance as the far more costly VRAM.

Burst EDO DRAM

[edit]An evolution of EDO DRAM, burst EDO DRAM (BEDO DRAM), could process four memory addresses in one burst, for a maximum of 5-1-1-1, saving an additional three clocks over optimally designed EDO memory. It was done by adding an address counter on the chip to keep track of the next address. BEDO also added a pipeline stage allowing page-access cycle to be divided into two parts. During a memory-read operation, the first part accessed the data from the memory array to the output stage (second latch). The second part drove the data bus from this latch at the appropriate logic level. Since the data is already in the output buffer, quicker access time is achieved (up to 50% for large blocks of data) than with traditional EDO.

Although BEDO DRAM showed additional optimization over EDO, by the time it was available the market had made a significant investment towards synchronous DRAM, or SDRAM.[69] Even though BEDO RAM was superior to SDRAM in some ways, the latter technology quickly displaced BEDO.

Synchronous dynamic RAM

[edit]Synchronous dynamic RAM (SDRAM) significantly revises the asynchronous memory interface, adding a clock (and a clock enable) line. All other signals are received on the rising edge of the clock.

The RAS and CAS inputs no longer act as strobes, but are instead, along with WE, part of a 3-bit command:

| CS | RAS | CAS | WE | Address | Command |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | x | x | x | x | Command inhibit (no operation) |

| L | H | H | H | x | No operation |

| L | H | H | L | x | Burst Terminate: stop a read or write burst in progress. |

| L | H | L | H | Column | Read from currently active row. |

| L | H | L | L | Column | Write to currently active row. |

| L | L | H | H | Row | Activate a row for read and write. |

| L | L | H | L | x | Precharge (deactivate) the current row. |

| L | L | L | H | x | Auto refresh: refresh one row of each bank, using an internal counter. |

| L | L | L | L | Mode | Load mode register: address bus specifies DRAM operation mode. |

The OE line's function is extended to a per-byte DQM signal, which controls data input (writes) in addition to data output (reads). This allows DRAM chips to be wider than 8 bits while still supporting byte-granularity writes.

Many timing parameters remain under the control of the DRAM controller. For example, a minimum time must elapse between a row being activated and a read or write command. One important parameter must be programmed into the SDRAM chip itself, namely the CAS latency. This is the number of clock cycles allowed for internal operations between a read command and the first data word appearing on the data bus. The Load mode register command is used to transfer this value to the SDRAM chip. Other configurable parameters include the length of read and write bursts, i.e. the number of words transferred per read or write command.

The most significant change, and the primary reason that SDRAM has supplanted asynchronous RAM, is the support for multiple internal banks inside the DRAM chip. Using a few bits of bank address that accompany each command, a second bank can be activated and begin reading data while a read from the first bank is in progress. By alternating banks, a single SDRAM device can keep the data bus continuously busy, in a way that asynchronous DRAM cannot.

Single data rate synchronous DRAM

[edit]Single data rate SDRAM (SDR SDRAM or SDR) is the original generation of SDRAM; it made a single transfer of data per clock cycle.

Double data rate synchronous DRAM

[edit]

Double data rate SDRAM (DDR SDRAM or DDR) was a later development of SDRAM, used in PC memory beginning in 2000. Subsequent versions are numbered sequentially (DDR2, DDR3, etc.). DDR SDRAM internally performs double-width accesses at the clock rate, and uses a double data rate interface to transfer one half on each clock edge. DDR2 and DDR3 increased this factor to 4× and 8×, respectively, delivering 4-word and 8-word bursts over 2 and 4 clock cycles, respectively. The internal access rate is mostly unchanged (200 million per second for DDR-400, DDR2-800 and DDR3-1600 memory), but each access transfers more data.

Direct Rambus DRAM

[edit]Direct RAMBUS DRAM (DRDRAM) was developed by Rambus. First supported on motherboards in 1999, it was intended to become an industry standard, but was outcompeted by DDR SDRAM, making it technically obsolete by 2003.

Reduced Latency DRAM

[edit]Reduced Latency DRAM (RLDRAM) is a high performance double data rate (DDR) SDRAM that combines fast, random access with high bandwidth, mainly intended for networking and caching applications.

Graphics RAM

[edit]Graphics RAMs are asynchronous and synchronous DRAMs designed for graphics-related tasks such as texture memory and framebuffers, found on video cards.

Video DRAM

[edit]Video DRAM (VRAM) is a dual-ported variant of DRAM that was once commonly used to store the frame buffer in some graphics adapters.

Window DRAM

[edit]Window DRAM (WRAM) is a variant of VRAM that was once used in graphics adapters such as the Matrox Millennium and ATI 3D Rage Pro. WRAM was designed to perform better and cost less than VRAM. WRAM offered up to 25% greater bandwidth than VRAM and accelerated commonly used graphical operations such as text drawing and block fills.[70]

Multibank DRAM

[edit]

Multibank DRAM (MDRAM) is a type of specialized DRAM developed by MoSys. It is constructed from small memory banks of 256 kB, which are operated in an interleaved fashion, providing bandwidths suitable for graphics cards at a lower cost to memories such as SRAM. MDRAM also allows operations to two banks in a single clock cycle, permitting multiple concurrent accesses to occur if the accesses were independent. MDRAM was primarily used in graphic cards, such as those featuring the Tseng Labs ET6x00 chipsets. Boards based upon this chipset often had the unusual capacity of 2.25 MB because of MDRAM's ability to be implemented more easily with such capacities. A graphics card with 2.25 MB of MDRAM had enough memory to provide 24-bit color at a resolution of 1024×768—a very popular setting at the time.

Synchronous graphics RAM

[edit]Synchronous graphics RAM (SGRAM) is a specialized form of SDRAM for graphics adapters. It adds functions such as bit masking (writing to a specified bit plane without affecting the others) and block write (filling a block of memory with a single color). Unlike VRAM and WRAM, SGRAM is single-ported. However, it can open two memory pages at once, which simulates the dual-port nature of other video RAM technologies.

Graphics double data rate SDRAM

[edit]

Graphics double data rate SDRAM is a type of specialized DDR SDRAM designed to be used as the main memory of graphics processing units (GPUs). GDDR SDRAM is distinct from commodity types of DDR SDRAM such as DDR3, although they share some core technologies. Their primary characteristics are higher clock frequencies for both the DRAM core and I/O interface, which provides greater memory bandwidth for GPUs. As of 2025, there are eight successive generations of GDDR: GDDR2, GDDR3, GDDR4, GDDR5, GDDR5X, GDDR6, GDDR6X and GDDR7.

Pseudostatic RAM

[edit]

Pseudostatic RAM (PSRAM or PSDRAM) is dynamic RAM with built-in refresh and address-control circuitry to make it behave similarly to static RAM (SRAM). It combines the high density of DRAM with the ease of use of true SRAM. PSRAM is used in the Apple iPhone and other embedded systems such as XFlar Platform.[71]

Some DRAM components have a self-refresh mode. While this involves much of the same logic that is needed for pseudo-static operation, this mode is often equivalent to a standby mode. It is provided primarily to allow a system to suspend operation of its DRAM controller to save power without losing data stored in DRAM, rather than to allow operation without a separate DRAM controller as is in the case of mentioned PSRAMs.

An embedded variant of PSRAM was sold by MoSys under the name 1T-SRAM. It is a set of small DRAM banks with an SRAM cache in front to make it behave much like a true SRAM. It is used in Nintendo GameCube and Wii video game consoles.

Cypress Semiconductor's HyperRAM[72] is a type of PSRAM supporting a JEDEC-compliant 8-pin HyperBus[73] or Octal xSPI interface.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "How to "open" microchip and what's inside? : ZeptoBars". 2012-11-15. Archived from the original on 2016-03-14. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

Micron MT4C1024 — 1 mebibit (220 bit) dynamic ram. Widely used in 286 and 386-era computers, early 90s. Die size - 8662x3969μm.

- ^ "NeXTServiceManualPages1-160" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Are the Major DRAM Suppliers Stunting DRAM Demand?". www.icinsights.com. Archived from the original on 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ^ EETimes; Hilson, Gary (2018-09-20). "DRAM Boom and Bust is Business as Usual". EETimes. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ^ Copeland, B. Jack (2010). Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-19-157366-8.

- ^ "Spec Sheet for Toshiba "TOSCAL" BC-1411". www.oldcalculatormuseum.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Toscal BC-1411 calculator". Science Museum, London. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29.

- ^ "Toshiba "Toscal" BC-1411 Desktop Calculator". Archived from the original on 2007-05-20.

- ^ "Memory Circuit". Google Patents. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "1966: Semiconductor RAMs Serve High-speed Storage Needs". Computer History Museum.

- ^ "DRAM". IBM100. IBM. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "IBM100 — DRAM". IBM. 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Robert Dennard". Encyclopedia Britannica. September 2023.

- ^ a b "1970: Semiconductors compete with magnetic cores". Computer History Museum.

- ^ US3387286A, Dennard, Robert H., "Field-effect transistor memory", issued 1968-06-04

- ^ Mary Bellis (23 Feb 2018). "Who Invented the Intel 1103 DRAM Chip?". ThoughtCo. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved 27 Feb 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-16. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Shirriff, Ken (November 2020). "Reverse-engineering the classic MK4116 16-kilobit DRAM chip".

- ^ Proebsting, Robert (14 September 2005). "Oral History of Robert Proebsting" (PDF). Interviewed by Hendrie, Gardner. Computer History Museum. X3274.2006.

- ^ "Outbreak of Japan-US Semiconductor War" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-29.

- ^ Nester, William R. (2016). American Industrial Policy: Free or Managed Markets?. Springer. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-349-25568-9.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (3 August 1985). "Japan chip 'dumping' is found". New York Times.

- ^ Woutat., Donald (4 November 1985). "6 Japan Chip Makers Cited for Dumping". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "More Japan Firms Accused: U.S. Contends 5 Companies Dumped Chips". Los Angeles Times. 1986.

- ^ Sanger, David E. (3 November 1987). "Japanese Chip Dumping Has Ended, U.S. Finds". New York Times.

- ^ "Electronic Design". Electronic Design. 41 (15–21). Hayden Publishing Company. 1993.

The first commercial synchronous DRAM, the Samsung 16-Mbit KM48SL2000, employs a single-bank architecture that lets system designers easily transition from asynchronous to synchronous systems.

- ^ "KM48SL2000-7 Datasheet". Samsung. August 1992. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ^ "Samsung Electronics Develops First 128Mb SDRAM with DDR/SDR Manufacturing Option". Samsung Electronics. Samsung. 10 February 1999. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Kuriko Miyake (2001). "Japanese chip makers say they suspect dumping by Korean firms". CNN.

- ^ "Japanese chip makers suspect dumping by Korean firms". ITWorld. 2001.

- ^ "DRAM pricing investigation in Japan targets Hynix, Samsung". EETimes. 2001.

- ^ "Korean DRAM finds itself shut out of Japan". Phys.org. 2006.

- ^ "Lecture 12: DRAM Basics" (PDF). utah.edu. 2011-02-17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ^ David August (2004-11-23). "Lecture 20: Memory Technology" (PDF). cs.princeton.edu. pp. 3–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-05-19. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Keeth et al. 2007, pp. 24–30

- ^ Halderman; et al. (2008). "Lest We Remember: Cold Boot Attacks on Encryption Keys". USENIX Security. Archived from the original on 2015-01-05.

- ^ "Micron 4 Meg x 4 EDO DRAM data sheet" (PDF). micron.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Corsair CMX1024-3200 (1 GByte, two bank unbuffered DDR SDRAM DIMM)" (PDF). December 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2008.

- ^ "Corsair TWINX1024-3200XL dual-channel memory kit" (PDF). May 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2006.

- ^ Keeth et al. 2007, p. 22

- ^ Keeth et al. 2007, p. 24

- ^ "Pro Audio Reference". Retrieved 2024-08-08.

- ^ Sallese, Jean-Michel (2002-06-20). Principles of the 1T Dynamic Access Memory Concept on SOI (PDF). MOS Modeling and Parameter Extraction Group Meeting. Wroclaw, Poland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-11-29. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ F. Morishita; et al. (21 September 2005). "A capacitorless twin-transistor random access memory (TTRAM) on SOI". Proceedings of the IEEE 2005 Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, 2005. Vol. Custom Integrated Circuits Conference 2005. pp. 428–431. doi:10.1109/CICC.2005.1568699. ISBN 978-0-7803-9023-2. S2CID 14952912.

- ^ J. Park et al., IEDM 2015.

- ^ "ECC DRAM – Intelligent Memory". intelligentmemory.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ^ Mastipuram, Ritesh; Wee, Edwin C (30 September 2004). "Soft errors' impact on system reliability". EDN. Cypress Semiconductor. Archived from the original on 16 April 2007.

- ^ Borucki, "Comparison of Accelerated DRAM Soft Error Rates Measured at Component and System Level", 46th Annual International Reliability Physics Symposium, Phoenix, 2008, pp. 482–487

- ^ Schroeder, Bianca et al. (2009). "DRAM errors in the wild: a large-scale field study" Archived 2015-03-10 at the Wayback Machine. Proceedings of the Eleventh International Joint Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems, pp. 193–204.

- ^ "A Memory Soft Error Measurement on Production Systems". www.ece.rochester.edu. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "DRAM's Damning Defects—and How They Cripple Computers - IEEE Spectrum". Archived from the original on 2015-11-24. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ^ Li, Huang; Shen, Chu (2010). ""A Realistic Evaluation of Memory Hardware Errors and Software System Susceptibility". Usenix Annual Tech Conference 2010" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-15.

- ^ "Cycles, cells and platters: an empirical analysis of hardware failures on a million consumer PCs. Proceedings of the sixth conference on Computer systems (EuroSys '11). pp 343-356" (PDF). 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-11-14.

- ^ a b "Center for Information Technology Policy » Lest We Remember: Cold Boot Attacks on Encryption Keys". Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. 080222 citp.princeton.edu

- ^ Scheick, Leif Z.; Guertin, Steven M.; Swift, Gary M. (December 2000). "Analysis of radiation effects on individual DRAM cells". IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 47 (6): 2534–2538. Bibcode:2000ITNS...47.2534S. doi:10.1109/23.903804. ISSN 0018-9499.

- ^ Yoongu Kim; Ross Daly; Jeremie Kim; Chris Fallin; Ji Hye Lee; Donghyuk Lee; Chris Wilkerson; Konrad Lai; Onur Mutlu (June 24, 2014). "Flipping Bits in Memory Without Accessing Them: DRAM Disturbance Errors" (PDF). ece.cmu.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-03-26. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Ian Poole. "SDRAM Memory Basics & Tutorial". Archived from the original on 2018-02-27. Retrieved 26 Feb 2018.

- ^ a b Understanding DRAM Operation (PDF) (Application Note). IBM. December 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017.

- ^ Z80 CPU (PDF) (User Manual). 2016. p. 3. UM008011-0816.

- ^ "What is DRAM refresh and why is the weird Apple II video memory layout affected by it?". 3 March 2020.

- ^ a b Various Methods of DRAM Refresh (PDF) (Technical Note). Micron Technology. 1994. TN-04-30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-03.

- ^ Keeth et al. 2007, p. 13

- ^ a b c Keeth et al. 2007, p. 14

- ^ S. Mueller (2004). Upgrading and Repairing Laptops. Que; Har/Cdr Edition. p. 221. ISBN 9780789728005.

- ^ EDO (Hyper Page Mode) (PDF) (Applications Note). IBM. 6 June 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-12-02.

a new address can be provided for the next access cycle before completing the current cycle allowing a shorter CAS pulse width, dramatically decreasing cycle times.

- ^ Lin, Albert (20 December 1999). "Memory Grades, the Most Confusing Subject". Simmtester.com. CST, Inc. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

So for the same –60 part, EDO DRAM is about 30% faster than FPM DRAM in peak data rate.

- ^ Huang, Andrew (14 September 1996). "Bunnie's RAM FAQ". Archived from the original on 12 June 2017.

- ^ Cuppu, Vinodh; Jacob, Bruce; Davis, Brian; Mudge, Trevor (November 2001). "High-Performance DRAMs in Workstation Environments" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. 50 (11): 1133–1153. doi:10.1109/12.966491. hdl:1903/7456. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- ^ Kent, Dean (24 October 1998). "Burst EDO (BEDO) - Ram Guide | Tom's Hardware". Tomshardware.com. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ "Window RAM (WRAM)". Archived from the original on 2010-01-02.

- ^ Mannion, Patrick (2008-07-12). "Under the Hood — Update: Apple iPhone 3G exposed". EETimes. Archived from the original on 2013-01-22.

- ^ "psRAM(HyperRAM)". Cypress semiconductor.

- ^ "Hyperbus". Cypress semiconductor.

- Keeth, Brent; Baker, R. Jacob; Johnson, Brian; Lin, Feng (2007). DRAM Circuit Design: Fundamental and High-Speed Topics. Wiley. ISBN 978-0470184752.

Further reading

[edit]- Jacob, Bruce; Wang, David; Ng, Spencer (2010) [2008]. Memory Systems: Cache, DRAM, Disk. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 978-0-08-055384-9.

External links

[edit]- Culler, David (2005). "Memory Capacity (Single Chip DRAM)". EECS 252 Graduate Computer Architecture: Lecture 1. Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences,University of California, Berkeley. p. 15. Logarithmic graph 1980–2003 showing size and cycle time.

- Benefits of Chipkill-Correct ECC for PC Server Main Memory — A 1997 discussion of SDRAM reliability—some interesting information on soft errors from cosmic rays, especially with respect to error-correcting code schemes

- Tezzaron Semiconductor Soft Error White Paper 1994 literature review of memory error rate measurements.

- Johnston, A. (October 2000). "Scaling and Technology Issues for Soft Error Rates" (PDF). 4th Annual Research Conference on Reliability Stanford University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-03.

- Mandelman, J. A.; Dennard, R. H.; Bronner, G. B.; Debrosse, J. K.; Divakaruni, R.; Li, Y.; Radens, C. J. (2002). "Challenges and future directions for the scaling of dynamic random-access memory (DRAM)". IBM Journal of Research and Development. 46 (2.3): 187–212. doi:10.1147/rd.462.0187. Archived from the original on 2005-03-22.

- Ars Technica: RAM Guide

- Wang, David Tawei (2005). Modern DRAM Memory Systems: Performance Analysis and a High Performance, Power-Constrained DRAM-Scheduling Algorithm (PDF) (PhD). University of Maryland, College Park. hdl:1903/2432. Retrieved 2007-03-10. A detailed description of current DRAM technology.

- Multi-port Cache DRAM — MP-RAM

- Drepper, Ulrich (2007). "What every programmer should know about memory".

Dynamic random-access memory

View on GrokipediaDynamic random-access memory (DRAM) is a type of volatile semiconductor memory that stores each bit of data as an electric charge in an array of capacitors integrated into a single semiconductor chip, with each capacitor paired to a transistor in a one-transistor-one-capacitor (1T1C) configuration.[1][2] The "dynamic" aspect arises because the stored charge in the capacitors leaks over time due to inherent imperfections, requiring periodic refreshing by a dedicated circuit to restore the data before it dissipates.[3][4] Invented by Robert H. Dennard at IBM's Thomas J. Watson Research Center, with a patent application filed in 1967 and granted on June 4, 1968 (U.S. Patent 3,387,286), DRAM achieved commercial viability in 1970 through Intel's production of the first 1-kilobit chip, enabling vastly higher memory densities and lower per-bit costs than static random-access memory (SRAM) due to its simpler cell structure using fewer transistors per bit.[5][1][6] This technology underpins the primary system memory in virtually all modern computers, servers, and electronic devices, supporting scalable capacities from megabits to terabits through iterative advancements like synchronous DRAM (SDRAM) and double data rate (DDR) variants.[7][8]

Fundamentals and Principles of Operation

Storage Mechanism and Physics

The storage mechanism in dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) relies on a one-transistor, one-capacitor (1T1C) cell architecture, where each bit is represented by the presence or absence of electric charge on a small capacitor.[2][9] The access transistor, typically an n-channel MOSFET, controls connectivity between the storage capacitor and the bit line, while the capacitor holds the charge corresponding to the data bit.[2] In the charged state (logical '1'), the storage node of the capacitor is driven to a voltage near the supply voltage VCC, storing a charge Q ≈ Cs · VCC, where Cs is the storage capacitance; the discharged state (logical '0') holds negligible charge.[9][10] To optimize sensing and reduce voltage stress, the capacitor's reference plate is often biased at VCC/2, resulting in effective charge levels of Q = ± (VCC/2) · Cs.[2] The physics of charge storage depends on the electrostatic field across the capacitor's dielectric, which separates conductive plates or electrodes to maintain the potential difference.[10] Capacitance follows Cs = ε · A / d, where ε is the permittivity of the dielectric, A is the effective plate area, and d is the separation distance; modern DRAM cells achieve Cs values of 20–30 fF through high-k dielectrics and three-dimensional structures to counteract scaling limitations.[10] However, charge retention is imperfect due to leakage mechanisms, including dielectric tunneling, junction leakage from thermal carrier generation-recombination, and subthreshold conduction through the off-state transistor.[11][12] These currents, often on the order of 1 fA per cell at room temperature, cause exponential decay of stored charge, with voltage dropping as ΔV = - (Ileak · t) / Cs over time t.[10][13] Retention time, defined as the duration until stored charge falls below a detectable threshold (typically 50–70% of initial voltage), ranges from milliseconds to seconds depending on temperature, process variations, and cell design, but standard DRAM specifications mandate refresh intervals of 64 ms to ensure data integrity across the array.[11][12] This dynamic nature stems from the causal primacy of charge leakage governed by semiconductor physics, where minority carrier generation rates increase exponentially with temperature (following Arrhenius behavior) and electric field, necessitating active refresh to counteract entropy-driven dissipation.[14] Lower temperatures extend retention by reducing leakage, as observed in cryogenic applications where times exceed room-temperature limits by orders of magnitude.[15]Read and Write Operations

In the conventional 1T1C DRAM cell, a write operation stores data by charging or discharging the storage capacitor through an n-channel MOSFET access transistor. The bit line is driven to VDD (typically 1-1.8 V in modern processes) to represent logic '1', charging the capacitor to store positive charge Q ≈ C × VDD, or to ground (0 V) for logic '0', where C is the cell capacitance (around 20-30 fF in sub-10 nm nodes).[16] The word line is pulsed high to turn on the transistor, transferring charge bidirectionally until equilibrium, with write time determined by RC delay (bit line resistance and capacitance).[17] This process overwrites prior cell state without sensing, enabling fast writes limited mainly by transistor drive strength and plate voltage biasing to minimize voltage droop.[18] Read operations in 1T1C cells are destructive due to charge sharing between the capacitor and precharged bit line. The bit line pair (BL and BL-bar) is equilibrated to VDD/2 via equalization transistors, minimizing offset errors.[9] Asserting the row address strobe (RAS) activates the word line, connecting the cell capacitor to the bit line; for a '1' state, charge redistribution raises BL voltage by ΔV ≈ (VDD/2) × (Ccell / (Ccell + CBL)), typically 100-200 mV given CBL >> Ccell (bit line capacitance ~200-300 fF).[16] [19] A differential latch-based sense amplifier then resolves this small differential by cross-coupling PMOS loads for positive feedback and NMOS drivers to pull low, latching BL to full rails (VDD or 0 V) while BL-bar inverts, enabling column access via column address strobe (CAS).[9] The sensed value is restored to the cell by driving the bit line back through the still-open transistor, compensating for leakage-induced loss (retention time ~64 ms at 85°C).[17] Sense amplifiers, often shared across 512-1024 cells per bit line in folded bit line arrays, incorporate reference schemes or open bit line pairing to reject common-mode noise, with timing constrained by tRCD (RAS-to-CAS delay ~10-20 ns) and access time ~30-50 ns in DDR4/5 modules.[18] Write-after-read restore ensures non-volatility within refresh cycles, but amplifies errors from process variations or alpha particle strikes, necessitating error-correcting codes (ECC).[16] In advanced nodes, dual-contact cell designs separate read/write paths in some embedded DRAM variants to mitigate read disturb, though standard commodity DRAM retains single-port 1T1C for density.Refresh Requirements and Timing