Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

History of erotic depictions

View on Wikipedia

The history of erotic depictions includes paintings, sculpture, photographs, dramatic arts, music and writings that show scenes of a sexual nature throughout time. They have been created by nearly every civilization, ancient and modern.[1] Early cultures often associated the sexual act with supernatural forces and thus their religion is intertwined with such depictions. In Asian countries such as India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Japan, Korea, and China, representations of sex and erotic art have specific spiritual meanings within native religions. The ancient Greeks and Romans produced much art and decoration of an erotic nature, much of it integrated with their religious beliefs and cultural practices.[2][3]

In more recent times, as communication technologies evolved, each new technique, such as printing, photography, motion pictures and computers, has been adapted to display and disseminate these depictions.[4]

Attitudes through history

[edit]

In early times, erotic depictions were often a subset of the indigenous or religious art of cultures and as such were not set aside or treated differently than any other type. The modern concept of pornography did not exist until the Victorian era. Its current definition was added in the 1860s, replacing the older one meaning writings about prostitutes.[6] It first appeared in an English medical dictionary in 1857 defined as "a description of prostitutes or of prostitution, as a matter of public hygiene."[7] By 1864, the first version of the modern definition had appeared in Webster's Dictionary: "licentious painting employed to decorate the walls of rooms sacred to bacchanalian orgies, examples of which exist in Pompeii."[8] This was the beginning of what today refers to explicit pictures in general. Though some specific sex acts were regulated or prohibited by earlier laws, merely looking at objects or images depicting them was not outlawed in any country until 1857. In some cases, the possession of certain books, engravings or image collections was outlawed, but the trend to compose laws that actually restricted viewing sexually explicit things in general was a Victorian construct.[4]

When large-scale excavations of Pompeii were undertaken in the 1860s, much of the erotic art of the Romans came to light, shocking the Victorians who saw themselves as the intellectual heirs of the Roman Empire. They did not know what to do with the frank depictions of sexuality, and endeavored to hide them away from everyone but upper-class scholars. The movable objects were locked away in the Secret Museum in Naples, and what could not be removed was covered and cordoned off so as to not corrupt the sensibilities of women, children and the working class. England's (and the world's) first laws criminalising pornography were enacted with the passage of the Obscene Publications Act 1857.[4] Despite their occasional repression, depictions of erotic themes have been common for millennia.[9]

Pornography has existed throughout recorded history and has adapted to each new medium, including photography, cinema, video, and computers and the internet.

The first instances of modern pornography date back to the sixteenth century when sexually explicit images differentiated itself from traditional sexual representations in European art by combining the traditionally explicit representation of sex and the moral norms of those times.[10]

The first amendment prohibits the U.S. government from restricting speech based on its content. Indecent speech is protected and may be regulated, but not banned. Obscenity is the judicially recognized exception to the first amendment. Historically, this exception was used in an attempt to ban information about sex education, studies on nudism, and sexually explicit literature.[11]

In the case of People v. Freeman, the California Supreme Court ruled to distinguish prostitution as an individual taking part in sexual activities in exchange for money versus an individual who is portraying a sexual act on-screen as part of their acting performance.[12] The case was not appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, thus it is only binding in the state of California.[13]

Early depictions

[edit]Prehistoric

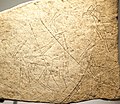

[edit]Among the oldest surviving examples of erotic depictions are Paleolithic cave paintings and carvings. Some of the more common images are of animals, hunting scenes and depictions of human genitalia. Nude human beings with exaggerated sexual characteristics are depicted in some Paleolithic paintings and artifacts (e.g. Venus figurines). Cave art discovered in the early 2000s at Creswell Crags in England, thought to be more than 12,000 years old, includes some symbols that may be stylized versions of female genitalia. As there was no direct evidence of the use of these objects, it was speculated that they may have been used in religious rituals,[14] or for a more directly sexual purpose.[15]

Archaeologists in Germany reported in April 2005 that they had found what they believed to be a 7,200-year-old scene depicting a male figurine bending over a female figurine in a manner suggestive of sexual intercourse. The male figure had been named Adonis von Zschernitz.[16]

-

Stone Age petroglyph of a vulva

-

Stone engraving of a sexual act, 3rd-2nd millennium BC, Museum of Sóller (Mallorca)

-

Petroglyph. Vitlycke, Sweden. Bronze-age.

Mesopotamia

[edit]A vast number of artifacts have been discovered from ancient Mesopotamia depicting explicit sexual intercourse.[17][18] Glyptic art from the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period frequently shows scenes of frontal sex in the missionary position.[17] In Mesopotamian votive plaques from the early second millennium BC, the man is usually shown entering the woman from behind while she bends over, drinking beer through a straw.[17] Middle Assyrian lead votive figurines often represent the man standing and penetrating the woman as she rests on top of an altar.[17] Scholars have traditionally interpreted all these depictions as scenes of ritual sex,[17] but they are more likely to be associated with the cult of Inanna, the goddess of sex and prostitution.[17] Many sexually explicit images were found in the temple of Inanna at Assur,[17] which also contained models of male and female sexual organs,[17] including stone phalli, which may have been worn around the neck as an amulet or used to decorate cult statues,[17] and clay models of the female vulva.[17]

-

Sex between a female and a male on a clay plaque. Mesopotamia 2000 BCE.

-

Sex between a female and a male. Terracotta plaque. Old Babylonian Period. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul, around 2000–1500 BCE.

Egypt

[edit]

Depictions of sexual intercourse were not part of the general repertory of ancient Egyptian formal art,[19] but rudimentary sketches of sexual intercourse have been found on pottery fragments and in graffiti.[19] The Turin Erotic Papyrus (Papyrus 55001) is a 8.5 feet (2.6 m) by 10 inches (25 cm) Egyptian papyrus scroll discovered at Deir el-Medina,[19][20] the last two-thirds of which consist of a series of twelve vignettes showing men and women in various sexual positions.[20] The men in the illustrations are "scruffy, balding, short, and paunchy" with exaggeratedly large genitalia[21] and do not conform to Egyptian standards of physical attractiveness,[19][21] but the women are nubile[19][21] and they are shown with objects from traditional erotic iconography, such as convolvulus leaves and, in some scenes, they are even holding items traditionally associated with Hathor, the goddess of love, such as lotus flowers, monkeys, and sistra.[19][21] The scroll was probably painted in the Ramesside period (1292–1075 BC)[20] and its high artistic quality indicates that was produced for a wealthy audience.[20] No other similar scrolls have yet been discovered.[19]

Greek and Roman

[edit]The ancient Greeks often painted sexual scenes on their ceramics, many of them famous for being some of the earliest depictions of same-sex relations and pederasty. Greek art often portrays sexual activity, but it is impossible to distinguish between what to them was illegal or immoral since the ancient Greeks did not have a concept of pornography. Their art simply reflects scenes from daily life, some more sexual than others. Carved phalli can be seen in places of worship such as the temple of Dionysus on Delos, while a common household item and protective charm was the herm, a statue consisting of a head on a square plinth with a prominent phallus on the front. The Greek male ideal had a small penis, an aesthetic the Romans later adopted.[4][22][23] The Greeks also created the first well-known instance of lesbian eroticism in the West, with Sappho's Hymn to Aphrodite and other homoerotic works.[24]

There are numerous sexually explicit paintings and sculptures from the ruined Roman buildings in Pompeii and Herculaneum but the original purposes of the depictions can vary. On one hand, in the Villa of the Mysteries, there is a ritual flagellation scene that is clearly associated with a religious cult and this image can be seen as having religious significance rather than sexual. On the other hand, graphic paintings in a brothel advertise sexual services in murals above each door. In Pompeii, phalli and testicles engraved in the sidewalks were created to aid visitors in finding their way by pointing to the prostitution and entertainment district as well as general decoration. The Romans considered depictions of sex to be decoration in good taste, and indeed the pictures reflect the sexual mores and practices of their culture, as on the Warren Cup. Sex acts that were considered taboo (such as oral sex) were depicted in baths for comic effect. Large phalli were often used near entryways, for the phallus was a good-luck charm, and the carvings were common in homes. One of the first objects excavated when the complex was discovered was a marble statue showing the god Pan having sex with a goat, a detailed depiction of bestiality considered so obscene that it was not on public display until the year 2000 and remains in the Secret Museum, Naples.[3][4][25]

Show large gallery

|

|---|

|

Peru

[edit]The Moche of Peru are another ancient people that sculpted explicit scenes of sex into their pottery. At least 500 Moche ceramics have sexual themes.[34]

Rafael Larco Hoyle speculates that their purpose was very different from that of other early cultures. He states that the Moche believed that the world of the dead was the exact opposite of the world of the living. Therefore, for funeral offerings, they made vessels showing sex acts such as masturbation, fellatio and anal sex that would not result in offspring. The hope was that in the world of the dead, they would take on their opposite meaning and result in fertility. The erotic pottery of the Moche is depicted in Hoyle's book Checan.[35]

-

Oral sex between a male and a female. Ceramic vessel. Moche, Peru. Larco Museum, Lima 1 CE – 800 CE.

-

A Recuay painted vessel. Terracotta. Museum of America, Madrid, 400 BCE – 300 CE.

-

Ceramic vessel. Moche, Peru.

Larco Museum, Lima 300 CE. -

Ceramic vessel. Moche Culture, Peru. Archaeological Museum of Kraków, 400 CE – 550 CE.

-

Ceramic vessel. Moche, Peru. Larco Museum, Lima, 1 CE – 800 CE.

-

Ceramic vessel. Moche, Peru. Larco Museum, Lima, 1 CE – 800 CE.

India

[edit]India produced copious quantities of art celebrating the human faculty of love. The works depict love between men and women as well as same-sex love. One of the most famous ancient sex manuals was the Kama Sutra, written by Vātsyāyana in India during the first few centuries CE.

-

Fresco murals from the Ajanta caves, 6th–7th century CE

-

Fresco. Ajanta caves. 6th–7th century CE

-

Painting from the Kama Sutra

Sinosphere

[edit]In Japan, erotic art found its widest success in the medium of woodblock printing, in the style known as shunga (春画, 'spring pictures'), to which many classical woodblock artists, such as Suzuki Harunobu and Kitagawa Utamaro, contributed a large number of works. Erotic painted hand scrolls were also very popular. Shunga appeared in the 13th century, and continued to grow in popularity, despite occasionally attempts by the authorities to clamp down on their production, the first instance of which being a ban on erotic books known as kōshokubon (好色本) issued by the Tokugawa shogunate in Kyōhō 7 (1722). Shunga only ceased to be produced in the 19th century, following the invention and wider spread of photography, which mainly usurped the medium.[2][36]

In Korea, chunhwa (Korean: 춘화; Hanja: 春畵) became prevalent during the Joseon era. Although the era was known to be conservative about the relationship between men and women, the introduction and spread of commerce allowed erotic arts to be made by artists.[37]

The Chinese tradition of erotic art was also extensive, with examples dating back as far as the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). The erotic art of China reached its peak during the latter part of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644).[2][38]

In both China and Japan, eroticism played a prominent role in the development of the novel. The Tale of Genji, sometimes considered the world's first novel, was produced in the 11th century by Heian period noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, and featured the depiction of many erotic affairs by its protagonist.[39] The more explicit 16th century Chinese novel The Plum in the Golden Vase, often called one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, was in contrast suppressed as pornography for much of its history, where The Tale of Genji was celebrated from its inception.[40]

Show large gallery

|

|---|

|

West Asia

[edit]The Umayyad caliph Al-Walid II, who ruled the Arab Islamic empire in the 8th century, was a great patron of erotic art. Among the depictions of the Qusayr Amra, which were built by him, is the abundance of naked females and love scenes.[41][42]

The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight (Arabic: الروض العاطر في نزهة الخاطر) is a fifteenth-century Arabic sex manual and work of erotic literature by Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Nefzawi, also known simply as "Nefzawi". The book presents opinions on what qualities men and women should have to be attractive and gives advice on sexual technique, warnings about sexual health, and recipes to remedy sexual maladies. It gives lists of names for the penis and vulva, and has a section on the interpretation of dreams. Interspersed with these there are a number of stories which are intended to give context and amusement.

-

Anal sex between two males. Watercolour on paper. Around 1660 – 1720, Safavid Iran.

-

Anal sex between two males. Watercolour on paper. Around 1660 – 1720, Safavid Iran.

European

[edit]Erotic scenes in medieval illuminated manuscripts also appeared, but were seen only by those who could afford the extremely expensive hand-made books. Most of these drawings occur in the margins of books of hours. Many medieval scholars think that the pictures satisfied the medieval cravings for both erotic pictures and religion in one book, especially since it was often the only book someone owned. Other scholars think the drawings in the margins were a kind of moral caution, but the depiction of priests and other ranking officials engaged in sex acts suggests political origins as well.[4]

It was not until the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg that sexually explicit images entered into any type of mass circulation in the western world. Before that time, erotic images, being hand made and expensive, were limited to upper class males. In Regency England, for example, Thomas Rowlandson produced a body of highly explicit erotica for a private clientele.[43] Even the British Museum had a Secretum filled with a collection of ancient erotica donated by the upper class doctor George Witt in 1865. The remains of the collection, including his scrapbooks, still reside in Cupboard 55, though the majority of it has recently been integrated with the museum's other collections.[44]

-

Die Nacht - Night by Sebald Beham. Engraving. (1548), 108 x 78 mm

-

Masturbation. Hôtel-de-Ville de Saint-Quentin. Saint-Quentin, France. Between 1331 and 1509.

-

"Neptune and Nymph". Bernard van Orley. Private collection. Date: First third of the 16th century.[47]

-

Beautiful Neapolitan woman seen from behind. Engraving from Dominique Vivant Denon's Oeuvre Priapique. 1787

-

Engraving from Dominique Vivant Denon's Oeuvre Priapique. 1793

-

Das Liebespaar (The Lovers), 1910

-

Gerda Wegener. 1925

Beginnings of mass circulation

[edit]Printing

[edit]

Prints became very popular in Europe from the middle of the fifteenth century, and because of their compact nature, were very suitable for erotic depictions that did not need to be permanently on display. Nudity and the revival of classical subjects were associated from very early on in the history of the print.

Many prints of subjects from mythological subjects were clearly in part an excuse for erotic material; the engravings of Giovanni Battista Palumba in particular. An earthier eroticism is seen in a printing plate of 1475–1500 for an Allegory of Copulation where a young couple are having sex, with the woman's legs high in the air, at one end of a bench, while at the other end a huge penis, with legs and wings and a bell tied around the bottom of the glans, is climbing onto the bench. Although the plate has been used until worn out, then re-engraved and heavily used again, none of the contemporary impressions printed, which probably ran into the hundreds, have survived.[48]

The loves of classical gods, especially those of Jupiter detailed in Ovid provided many subjects where actual sex was the key moment in the story, and its depiction was felt to be justified. In particular, Leda and the Swan, where the god appeared as a swan and seduced the woman, was depicted very explicitly; it seems that this was considered more acceptable because he appeared as a bird.[49] For a period ending in the early 16th century the boundaries of what could be depicted in works for display in the semi-privacy of a Renaissance palace seemed uncertain. Michelangelo's Leda was a fairly large painting showing sex in progress, and one of the hundreds of illustrations to the book the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of 1499 shows Leda and the Swan having sex on top of a triumphal car watched by a crowd.[50]

In around 1524 – 1527 the artist Marcantonio Raimondi published I Modi. I modi contained engravings of sexual scenes and was created in a collaboration between Marcantonio raimondi and Giulio Romano. One idea is that Raimondi based the engravings on a series of erotic paintings that Giulio Romano was doing as a commission for the Palazzo del Te in Mantua. Pope Clement VII destroyed all copies of the engravings. Romano did not know of the engravings until Pietro Aretino, considered a founder of pornography,[51][52] came to see the original paintings while Romano was still working on them. Aretino then composed sixteen explicit sonnets ("both in your cunt and your behind, my prick will make me happy, and you happy and blissful")[4][53] to go with the paintings. I Modi was then published a second time in 1527, with the poems and the pictures, making this the first time erotic text and images were combined, though the papacy once more seized all the copies it could find. There are now no known copies of the first two editions of "I modi" by Marcantonio Raimondi and Giulio Romano. The text in existence is only a copy of a copy that was discovered 400 years later.[4][53] In around 1530 Agostino Veneziano is thought to have created a replacement set of engravings for those that were in I modi.

In the 17th century, numerous examples of pornographic or erotic literature began to circulate. These included L'Ecole des Filles, a French work printed in 1655 that is considered to be the beginning of pornography in France. It consists of an illustrated dialogue between two women, a 16-year-old and her more worldly cousin, and their explicit discussions about sex. The author remains anonymous to this day, though a few suspected authors served light prison sentences for supposed authorship of the work.[54] In his famous diary, Samuel Pepys records purchasing a copy for solitary reading and then burning it so that it would not be discovered by his wife; "the idle roguish book, L'escholle de filles; which I have bought in plain binding… because I resolve, as soon as I have read it, to burn it."[55]

During the Enlightenment, many of the French free-thinkers began to exploit pornography as a medium of social criticism and satire. Libertine pornography was a subversive social commentary and often targeted the Catholic Church and general attitudes of sexual repression. The market for the mass-produced, inexpensive pamphlets soon became the bourgeoisie, making the upper class worry, as in England, that the morals of the lower class and weak-minded would be corrupted since women, slaves and the uneducated were seen as especially vulnerable during that time. The stories and illustrations (sold in the galleries of the Palais Royal, along with the services of prostitutes) were often anti-clerical and full of misbehaving priests, monks and nuns, a tradition that in French pornography continued into the 20th century. In the period leading up to the French Revolution, pornography was also used as political commentary; Marie Antoinette was often targeted with fantasies involving orgies, lesbian activities, and the paternity of her children, and rumours circulated about the supposed sexual inadequacies of Louis XVI.[54][56] During and after the Revolution, the famous works of the Marquis de Sade were printed. They were often accompanied by illustrations and served as political commentary for their author.[57]

The English answer to the French was Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (later abridged and renamed Fanny Hill), written in 1748 by John Cleland. While the text satirised the literary conventions and fashionable manners of 18th century England, it was more scandalous for depicting a woman, the narrator, enjoying and even reveling in sexual acts with no dire moral or physical consequences. The text is hardly explicit as Cleland wrote the entire book using euphemisms for sex acts and body parts, employing 50 different ones just for the term penis. Two small earthquakes were credited to the book by the Bishop of London and Cleland was arrested and briefly imprisoned, but Fanny Hill continued to be published and is one of the most reprinted books in the English language. However, it was not legal to own this book in the United States until 1963 and in the United Kingdom until 1970.[58]

Photography

[edit]

In 1839, Louis Daguerre presented the first practical process of photography to the French Academy of Sciences.[59] Unlike earlier photographic methods, his daguerreotypes had stunning quality and detail and did not fade with time. Artists adopted the new technology as a new way to depict the nude form, which in practice was the feminine form. In so doing, at least initially, they tried to follow the styles and traditions of the art form. Traditionally, an académie was a nude study done by a painter to master the female (or male) form. Each had to be registered with the French government and approved or they could not be sold. Soon, nude photographs were being registered as académie and marketed as aids to painters. However, the realism of a photograph as opposed to the idealism of a painting made many of these intrinsically erotic.[4]

The daguerreotypes were not without drawbacks, however. The main difficulty was that they could only be reproduced by photographing the original picture since each image was an original and the all-metal process does not use negatives. In addition, the earliest daguerreotypes had exposure times ranging from three to fifteen minutes, making them somewhat impractical for portraiture. Unlike earlier drawings, action could not be shown. The poses that the models struck had to be held very still for a long time. Because of this, the standard pornographic image shifted from one of two or more people engaged in sex acts to a solitary woman exposing her genitals. Since one picture could cost a week's salary, the audience for these nudes mostly consisted of artists and the upper echelon of society. It was cheaper to hire a prostitute and experience the sex acts than it was to own a picture of them in the 1840s.[4] Stereoscopy was invented in 1838 and became extremely popular for daguerreotypes,[60][61] including the erotic images. This technology produced a type of three dimensional view that suited erotic images quite well. Although thousands of erotic daguerreotypes were created, only around 800 are known to survive; however, their uniqueness and expense meant that they were once the toys of rich men. Due to their rarity, the works can sell for more than 10,000 GBP.[4]

In 1841, William Fox Talbot patented the calotype process, the first negative-positive process, making possible multiple copies.[62] This invention permitted an almost limitless number of prints to be produced from a glass negative. Also, the reduction in exposure time made a true mass market for pornographic pictures possible. The technology was immediately employed to reproduce nude portraits. Paris soon became the centre of this trade. In 1848 only thirteen photography studios existed in Paris; by 1860, there were over 400. Most of them profited by selling illicit pornography to the masses who could now afford it. The pictures were also sold near train stations, by traveling salesmen and women in the streets who hid them under their dresses. They were often produced in sets (of four, eight or twelve), and exported internationally, mainly to England and the United States. Both the models and the photographers were commonly from the working class, and the artistic model excuse was increasingly hard to use. By 1855, no more photographic nudes were being registered as académie, and the business had gone underground to escape prosecution.[4]

The Victorian pornographic tradition in the UK had three main elements: French photographs, erotic prints (sold in shops in Holywell Street, a long vanished London thoroughfare, swept away by the Aldwych), and printed literature. The ability to reproduce photographs in bulk assisted the rise of a new business individual, the porn dealer. Many of these dealers took advantage of the postal system to send out photographic cards in plain wrappings to their subscribers. Therefore, the development of a reliable international postal system facilitated the beginnings of the pornography trade. Victorian pornography had several defining characteristics. It reflected a very mechanistic view of the human anatomy and its functions. Science, the new obsession, was used to ostensibly study the human body. Consequently, the sexuality of the subject is often depersonalised, and is without any passion or tenderness. At this time, it also became popular to depict nude photographs of women of exotic ethnicities, under the umbrella of science. Studies of this type can be found in the work of Eadweard Muybridge. Although he photographed both men and women, the women were often given props like market baskets and fishing poles, making the images of women thinly disguised erotica.[4] Parallel to the British printing history, photographers and printers in France frequently turned to the medium of postcards, producing great numbers of them. Such cards came to be known in the US as "French postcards".[63]

Magazines

[edit]

During the Victorian period, illegal pornographic periodicals such as The Pearl, which ran for eighteen issues between 1879 and 1880, circulated clandestinely among circles of elite urban gentlemen.[64] In 1880, halftone printing was used to reproduce photographs inexpensively for the first time.[59] The invention of halftone printing took pornography and erotica in new directions at the beginning of the 20th century. The new printing processes allowed photographic images to be reproduced easily in black and white, whereas printers were previously limited to engravings, woodcuts and line cuts for illustrations.[65] This was the first format that allowed pornography to become a mass market phenomena, it now being more affordable and more easily acquired than any previous form.[4]

First appearing in France, the new magazines featured nude (often, burlesque actresses were hired as models) and semi-nude photographs on the cover and throughout; while these would now be termed softcore, they were quite shocking for the time. The publications soon either masqueraded as "art magazines" or publications celebrating the new cult of naturism, with titles such as Photo Bits, Body in Art, Figure Photography, Nude Living and Modern Art for Men.[4] Health and Efficiency, started in 1900, was a typical naturist magazine in Britain.[66]

Another early form of pornography were comic books known as Tijuana bibles that began appearing in the U.S. in the 1920s and lasted until the publishing of glossy colour men's magazines commenced. These were crude hand drawn scenes often using popular characters from cartoons and culture.[67]

In the 1940s, the word "pinup" was coined to describe pictures torn from men's magazines and calendars and "pinned up" on the wall by U.S. soldiers in World War II. While the '40s images focused mostly on legs, by the '50s, the emphasis shifted to breasts. Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe were two of the most popular pinup models. In the second half of the 20th century, pornography evolved into the men's magazines such as Playboy and Modern Man of the 1950s. In fact, the beginning of the modern men's glossy magazine (or girlie magazine) can be traced to the 1953 purchase by Hugh Hefner of a photograph of Marilyn Monroe to use as the centerfold of his new magazine Playboy. Soon, this type of magazine was the primary medium in which pornography was consumed.[68]

In postwar Britain digest magazines such as Beautiful Britons, Spick and Span, with their interest in nylons and underwear and the racier Kamera published by Harrison Marks were incredibly popular. The creative force behind Kamera was Harrison Marks' partner Pamela Green. These magazines featured nude or semi-nude women in extremely coy or flirtatious poses with no hint of pubic hair.

Penthouse, started by Bob Guccione in England in 1965, took a different approach. Women looked indirectly at the camera, as if they were going about their private idylls. This change of emphasis was influential in erotic depictions of women. Penthouse was also the first magazine to publish pictures that included pubic hair and full frontal nudity, both of which were considered beyond the bounds of the erotic and in the realm of pornography at the time. In the late 1960s, magazines began to move into more explicit displays often focusing on the buttocks as standards of what could be legally depicted and what readers wanted to see changed. By the 1970s, they were focusing on the pubic area and eventually, by the 1990s, featured sexual penetration, lesbianism and homosexuality, group sex, masturbation, and fetishes in the more hard-core magazines such as Hustler.[4][68]

Magazines for every taste and fetish were soon created due to the low cost of producing them. Magazines for the gay community flourished, the most notable and one of the first being Physique Pictorial, started in 1951 by Bob Mizer when his attempt to sell the services of male models; however, Athletic Model Guild photographs of them failed. It was published in black and white, in a very clear yet photographic manner celebrating the male form and was published for nearly 50 years. The magazine was innovative in its use of props and costumes to depict the now standard gay icons like cowboys, gladiators and sailors.[4][69]

Moving pictures

[edit]

Production of erotic films commenced almost immediately after the invention of the motion picture. Two of the earliest pioneers were Frenchmen Eugène Pirou and Albert Kirchner. Kirchner (under the name "Léar") directed the earliest surviving erotic film for Pirou. The 7-minute 1896 film Le Coucher de la Mariee had Louise Willy performing a bathroom striptease.[70] Other French filmmakers also considered that profits could be made from this type of risqué films, showing women disrobing.[71][72]

Also in 1896, Fatima's Coochie-Coochie dance[73] was released as a short kinetoscope film featuring a gyrating belly dancer named Fatima. Her gyrating and moving pelvis was censored, one of the earliest films to be censored. At the time, there were numerous risqué films that featured exotic dancers.[74] In the same year, The May Irwin Kiss contained the very first kiss on film. It was a 20-second film loop, with a close-up of a nuzzling couple followed by a short peck on the lips ("the mysteries of the kiss revealed"). The kissing scene was denounced as shocking and pornographic to early moviegoers and caused the Roman Catholic Church to call for censorship and moral reform – because kissing in public at the time could lead to prosecution.[74] A tableau vivant style is used in short film The Birth of the Pearl (1901)[75] featuring an unnamed long-haired young model wearing a flesh-colored body stocking in a direct frontal pose[74] that provides a provocative view of the female body.[76] The pose is in the style of Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.

Because Pirou is nearly unknown as a pornographic filmmaker, credit is often given to other films for being the first. In Black and White and Blue (2008), one of the most scholarly attempts to document the origins of the clandestine 'stag film' trade, Dave Thompson recounts ample evidence that such an industry first had sprung up in the brothels of Buenos Aires and other South American cities by around the start of the 20th century, and then quickly spread through Central Europe over the following few years; however, none of these earliest pornographic films is known to survive. According to Patrick Robertson's Film Facts, "the earliest pornographic motion picture which can definitely be dated is A L'Ecu d'Or ou la bonne auberge" made in France in 1908; the plot depicts a weary soldier who has a tryst with a servant girl at an inn. The Argentinian El Satario might be even older; it has been dated to somewhere between 1907 and 1912. He also notes that "the oldest surviving pornographic films are contained in America's Kinsey Collection. One film demonstrates how early pornographic conventions were established. The German film Am Abend (1910) is "a ten-minute film which begins with a woman masturbating alone in her bedroom, and progresses to scenes of her with a man performing straight sex, fellatio and anal penetration."[77]

In Austria, Johann Schwarzer formed his Saturn-Film production company which was able to produce 52 erotic productions between 1906 and 1911, when the company was dissolved by the censorship authorities and the films destroyed.

Soon illegal stag films or blue films, as they were called, were produced underground by amateurs for many years starting in the 1940s. Processing the film took considerable time and resources, with people using their bathtubs to wash the film when processing facilities (often tied to organized crime) were unavailable. The films were then circulated privately or by traveling salesman but being caught viewing or possessing them put one at the risk of prison.[4][78]

The post-war era saw developments that further stimulated the growth of a mass market. Technological developments, particularly the introduction of the 8mm and super-8 film gauges, resulted in the widespread use of amateur cinematography. Entrepreneurs emerged to supply this market. In the UK, the productions of Harrison Marks were "soft core", but considered risqué in the 1950s. On the continent, such films were more explicit. Lasse Braun was as a pioneer in quality colour productions that were, in the early days, distributed by making use of his father's diplomatic privileges. Pornography was first legalized in Denmark July 1969,[79] soon followed by the Netherlands the same year and Sweden in 1971, and this led to an explosion of commercially produced pornography in those countries, with the Color Climax Corporation quickly becoming the leading pornographic producer for the next couple of decades. Now that being a pornographer was a legitimate occupation, there was no shortage of businessmen to invest in proper plant and equipment capable of turning out a mass-produced, cheap, but quality product. Vast amounts of this new pornography, both magazines and films, were smuggled into other parts of Europe, where it was sold "under the counter" or (sometimes) shown in "members only" cinema clubs.[4]

The first explicitly pornographic film with a plot that received a general theatrical release in the U.S. is generally considered to be Mona the Virgin Nymph (also known as Mona), a 59-minute 1970 feature by Bill Osco and Howard Ziehm, who went on to create the relatively high-budget hardcore/softcore (depending on the release) cult film Flesh Gordon.[78][80] The 1971 film Boys in the Sand represented a number of pornographic firsts. As the first generally available gay pornographic film, the film was the first to include on-screen credits for its cast and crew (albeit largely under pseudonyms), to parody the title of a mainstream film (in this case, The Boys in the Band), and to be reviewed by The New York Times.[81] In 1972, pornographic films hit their public peak in the United States with both Deep Throat and Behind the Green Door being met with public approval and becoming social phenomena.

The Devil in Miss Jones followed in 1973 and many predicted that frank depictions of sex onscreen would soon become commonplace, with William Rotsler saying in 1973, "Erotic films are here to stay. Eventually they will simply merge into the mainstream of motion pictures and disappear as a labeled sub-division. Nothing can stop this".[82] In practice, a combination of factors put an end to big budget productions and the mainstreaming of pornography, and in many places it never got close – with Deep Throat not approved in its uncut form in the UK until 2000, and not shown publicly until June 2005.[78][83][84]

Video and digital depictions

[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (December 2023) |

By 1982, most pornographic films were being shot on the cheaper and more convenient medium of videotape. Many film directors resisted this shift at first because of the different image quality that video tape produced; however, those who did change soon were collecting most of the industry's profits since consumers overwhelmingly preferred the new format. The technology change happened quickly and completely when directors realised that continuing to shoot on film was no longer a profitable option. This change moved the films out of the theaters and into people's private homes. This was the end of the age of big budget productions and the mainstreaming of pornography. It soon went back to its lower budget roots and expanded to cover more fetishes and niches possible due to the low cost of production. Instead of hundreds of pornographic films being made each year, thousands now were, including compilations of just the sex scenes from various videos.[4][78]

Erotic CD-ROMs were popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s because they brought an unprecedented element of interactiveness and fantasy. However, their poor quality was a drawback and when the Internet became common in households, their sales declined. Beginning in the 1990s, the Internet became the preferred source of pornography for many people, offering both privacy in viewing and the chance to interact with people. The spread of technology such as digital cameras, both moving and still, blurred the lines between erotic films, photographs and amateur and professional productions. Production became easily achieved by anyone with access to the equipment. Much of the pornography available today is produced by amateurs. Digital media allows photographers and filmmakers to manipulate images in ways previously not possible, heightening the drama or eroticism of a depiction.[4]

High-definition video shows signs of changing the image of pornography as the technology is increasingly used for professional productions. The porn industry was one of the first to adopt the technology and it may have been a deciding factor in the format competition between HD DVD and Blu-ray Disc.[85] Additionally, the clearer sharper images it provides have prompted performers to get cosmetic surgery and professional grooming to hide imperfections that are not visible on other video formats. Other adaptations have been different camera angles and techniques for close-ups and lighting.[86]

See also

[edit]- Charles Guyette

- Cultural history of the buttocks

- Eric Stanton

- Erotica

- Erotic art

- Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

- Gene Bilbrew

- History of human sexuality

- Homosexuality in ancient Greece

- Homosexuality in ancient Rome

- I Modi

- Irving Klaw

- John Willie

- Pederasty in Ancient Greece

- Prostitution in ancient Rome

- Sexuality in ancient Rome

References

[edit]- ^ Ruzgyte, Edita (2015). "Pornography, history of". The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. pp. 861–1042. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs367. ISBN 978-1-4051-9006-0.

- ^ a b c Rawson, Phillip S. (1968). Erotic art of the east; the sexual theme in oriental painting and sculpture. New York: Putnam. p. 380. LCC N7260.R35.

- ^ a b c Clarke, John R. (April 2003). Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 168. ISBN 0-8109-4263-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Chris Rodley, Dev Varma, Kate Williams III (Directors) Marilyn Milgrom, Grant Romer, Rolf Borowczak, Bob Guccione, Dean Kuipers (Cast) (2006-03-07). Pornography: The Secret History of Civilization (DVD). Port Washington, NY: Koch Vision. ISBN 1-4172-2885-7. Archived from the original on 2010-08-22. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ "David's Fig Leaf". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 3 June 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- ^ Sigel, Lisa (2002). Governing Pleasures. Pornography and Social Change in England, 1815–1914. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-3001-6.

- ^ Dunglison, Robley (1857). Medical lexicon. A dictionary of medical science, 1857 edition, s.v. "Pornography". From the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition (1989), Oxford University Press, Retrieved on November 30, 2006.

- ^ An American dictionary of the English language, new and revised edition (1864), s.v. "Pornography". From the Oxford English Dictionary, second edition (1989), Oxford University Press, Retrieved on November 30, 2006.

- ^ Beck, Marianna (May 2003). "The Roots of Western Pornography: Victorian Obsessions and Fin-de-Siècle Predilections". Libido, The Journal of Sex and Sensibility. Libido Inc. Archived from the original on 2003-04-04. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Shepard, 2003

- ^ Reese, Debbie-Anne; Kyle, Deva A. (Fall 2002). "Obscenity and Pornography". Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law. 4 (1): 137–168 – via HeinOnline.

- ^ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions". Findlaw. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ "Porn In The U.S.A." www.cbsnews.com. 21 November 2003. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ Pickrell, John (August 18, 2004). "Unprecedented Ice Age Cave Art Discovered in U.K." National Geographic News. Nationalgeographic.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2004. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ Rudgley, Richard (2000-01-25). The Lost Civilizations of the Stone Age. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684862705.

- ^ Driver, Krysia (2005-04-04). "Archaeologist finds 'oldest porn statue'". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 150–152. ISBN 0-7141-1705-6.

- ^ Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 137. ISBN 978-0313294976.

- ^ a b c d e f g Robins, Gay (1993). Women in Ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 0-674-95469-6.

Turin erotic papyrus.

- ^ a b c d O'Connor, David (September–October 2001). "Eros in Egypt". Archaeology Odyssey. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt, Robert A.; Voss, Barbara L. (2000). Archaeologies of Sexuality. Abingdon-on-Thames, England: Psychology Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-415-22366-9.

- ^ "Herm of Dionysos". The Getty Museum, J.Paul Getty Trust. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (9 December 2005). "Why does so much ancient Greek art feature males with small genitalia?". The Straight Dope. Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2006-10-19.

- ^ Williamson, Margaret (1995). Sappho's Immortal Daughters. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-78912-1.

- ^ Hemingway, Seán (Winter 2004). "Roman Erotic Art". Sculpture Review. 53 (4). National Sculpture Society: 10–15. doi:10.1002/j.2632-3494.2004.tb00171.x. Retrieved 2006-10-24.

- ^ Brendle, Ross (April 2019). "The Pederastic Gaze in Attic Vase-Painting". Arts. 8 (2): 47. doi:10.3390/arts8020047.

- ^ Shapiro, H. A. (Apr 1981). "Courtship Scenes in Attic Vase-Painting". American Journal of Archaeology. 85 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 133–143. doi:10.2307/505033. JSTOR 505033. S2CID 192965111. Archived from the original on 14 April 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Jared Alan Johnson (2015). "The Greek Youthening: Assessing the Iconographic Changes within Courtship during the Late Archaic Period." (Master's thesis). University of Tennessee. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ John R. Clarke (2017). "Sexual representation, visual". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ John R. Clarke (1998). Looking at Lovemaking Constructions of Sexuality in Roman Art, 100 B.C. – A.D. 250. University of California Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9780520229044.

- ^ John R Clarke (1998). Looking at Lovemaking. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520229044.

- ^ John R. Clarke (2007). Looking at Laughter Humor, Power, and Transgression in Roman Visual Culture, 100 B.C.- A.D. 250. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520237339.

- ^ Michael Grant (1975). "Erotic art in Pompeii" The secret collection of the national museum of Naples". Octopus Books. p. 155. ISBN 0-7064-0460-2.

- ^ Weismantel, M. (2004). "Moche sex pots: Reproduction and temporality in ancient South America" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 106 (3): 495–496. doi:10.1525/aa.2004.106.3.495.

- ^ book-review (In British Journal of Aesthetics, Vol. 6, 1966) of Checan

- ^ Parent, Mary N (2001). "Shunga". Japanese Architecture and Art net users system. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Kim, Hyung-eun (15 January 2013). "Exhibit offers rare peek at Joseon eroticism". Korea JoongAng Daily. Retrieved 23 April 2024.

- ^ Bertholet, L.C.P. (October 1997). Dreams of Spring: Erotic Art in China: From the Bertholet Collection. Pepin Press. ISBN 90-5496-039-6.

- ^ Puette, William J. (2004). The Tale of Genji: A Reader's Guide. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3331-1.

- ^ Roy, David Tod (1993). The Plum in the Golden Vase or, Chin P'ing Mei : The Gathering, Volume I. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06932-8.

- ^ "The Archaeology of a Byzantine City – Link IV: Qusayr 'Amra".

- ^ Fowden, Garth (2004). "Luxuries of the Bath". Qusayr Amra Art and the Umayyad Elite in Late Antique Syria. pp. 31–84. doi:10.1525/california/9780520236653.003.0002. ISBN 9780520236653.

- ^ "Thomas Rowlandson | English painter and caricaturist | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-09-09.

- ^ Giamster, David (September 2000). "Sex and Sensibility at the British Museum". History Today. 50 (9): 10–15. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ^ "The Hall of the Months at Palazzo Schifanoia". iGuzzini illuminazione. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ "The Hall of the Months". Civic Museums of Ancient Art, Ferrara. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Becker, Claus; Shy, Marlon; Orlando, Vincenzo; Elder, Irene; Ungerer, Toni (1992). Museum der Erotischen Kunst. Munich: Wilhelm Heyne. ISBN 978-3-453-06268-9.

- ^ Oberhuber, Konrad (1973). Levinson, Jay A. (ed.). Early Italian Engravings from the National Gallery of Art. Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art. pp. 526–27. LOC 7379624.

- ^ Bull, Malcolm (February 21, 2005). The Mirror of the Gods, How Renaissance Artists Rediscovered the Pagan Gods. US: Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-521923-4.

- ^ Lefaivre, Liane (April 1, 2005). Leon Battista Alberti's 'Hypnerotomachia Poliphili': re-cognizing the architectural body in the early Italian Renaissance. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-62195-3. Archived from the original on November 22, 2007.

- ^ Melville, G.; Ruta, C. (2015). Thinking the body as a basis, provocation and burden of life: Studies in intercultural and historical contexts. Challenges of Life: Essays on philosophical and cultural anthropology. De Gruyter. p. 274. ISBN 978-3-11-040747-1. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ Mills, J. (1995). Erotic Literature: Twenty-Four Centuries of Sensual Writing. Harpercollins. ISBN 978-0-06-272036-8. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ a b Lawner, Lynne, ed. (1989). I Modi; the sixteen pleasures: an erotic album of the Italian Renaissance. Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-0803-8.

- ^ a b Beck, Marianna (December 2003). "The Roots of Western Pornography: the French Enlightenment takes on sex". Libido, the Journal of Sex and Sensibility. Libido Inc. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Latham, Robert, ed. (1985). The Shorter Pepys. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03426-0.

- ^ Beck, Marianna (February 2003). "The Roots of Western Pornography: the French Revolution and the spread of politically-motivated pornography". Libido, the Journal of Sex and Sensibility. Libido Inc. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Beck, Marianna (March 2003). "The Roots of Western Pornography: the Marquis de Sade's twisted parody of life". Libido, the Journal of Sex and Sensibility. Libido Inc. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ Beck, Marianna (January 2003). "The Roots of Western Pornography: England bites back with Fanny Hill". Libido, the Journal of Sex and Sensibility. Libido Inc. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ a b Cross, J.M. (2001-02-04). "Nineteenth-Century Photography: A Timeline". the Victorian Web. The University Scholars Programme, National University of Singapore. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Wheatstone, Charles (June 21, 1838). "Contributions to the Physiology of Vision.—Part the First. On some remarkable, and hitherto unobserved, Phenomena of Binocular Vision". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 128. Royal Society of London: 371–394. doi:10.1098/rstl.1838.0019. S2CID 36512205. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ^ Klein, Alexander. "Sir Charles Wheatstone". Stereoscopy.com. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Schaaf, Larry (1999). "The Calotype Process". Glasgow University Library. Archived from the original on 2006-06-19. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Herbst, Philip (1997). The Color of Words: An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Ethnic Bias in the United States. Intercultural Press. p. 86. ISBN 9781877864971.

- ^ Thomas J. Joudrey, "Against Communal Nostalgia: Reconstructing Sociality in the Pornographic Ballad," Victorian Poetry 54.4 (2017).

- ^ St. John, Kristen; Linda Zimmerman (June 1997). "Guided Tour of Print Processes: Black and White Reproduction". Stanford library. Retrieved 2006-08-24.

- ^ "About H&E Naturist". Health and Efficiency Naturist. Archived from the original on 2006-10-14. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ Adelman, Bob; Richard Merkin (September 1, 1997). Tijuana Bibles: Art and Wit in America's Forbidden Funnies, 1930s–1950s. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 160. ISBN 0-684-83461-8.

- ^ a b Gabor, Mark (February 27, 1984). The Illustrated History of Girlie Magazines. New York: Random House Value Publishing. ISBN 0-517-54997-2.

- ^ Bianco, David. "Physique Magazines". Planet Out History. PlanetOut Inc. Archived from the original on 2006-08-30. Retrieved 2006-10-10.

- ^ Richard Abel, Encyclopedia of early cinema, Taylor & Francis, 2005, ISBN 978-0-415-23440-5, p.518

- ^ Bottomore, Stephen (1996). Stephen Herbert; Luke McKernan (eds.). "Léar (Albert Kirchner)". Who's Who of Victorian Cinema. British Film Institute. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ Bottomore, Stephen (1996). Stephen Herbert; Luke McKernan (eds.). "Eugène Pirou". Who's Who of Victorian Cinema. British Film Institute. Retrieved 15 October 2006.

- ^ Produced by James A. White and shot by William Heise for the Edison Manufacturing Co. in 1896.

- ^ a b c Sex in Cinema: Pre-1920s

- ^ Produced by Frederick S. Armitage for the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company.

- ^ "The Birth of the Pearl". Library of Congress. 1901. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Robertson, Patrick (December 2001). Film Facts. Billboard Books. p. 256. ISBN 0-8230-7943-0.

- ^ a b c d Corliss, Richard (March 29, 2005). "That Old Feeling: When Porno Was Chic". Time. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ^ Denmark in the International Encyclopedia of Sexuality Archived 2011-01-13 at the Wayback Machine – "...Denmark was the first country in the world to legitimize written pornography in 1967 (followed by pictorial pornography in 1969)."

- ^ Mehendale, Rachel (February 9, 2006). "Is porn a problem?" (PDF). Sex. The Daily Texan. pp. 17, 22. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ^ Edmonson, Roger; Cal Culver; Casey Donovan (October 1998). Boy in the Sand: Casey Donovan, All-American Sex Star. Alyson Books. p. 264. ISBN 1-55583-457-4.

- ^ Schaefer, Eric (Fall 2005). "Dirty Little Secrets: Scholars, Archivists, and Dirty Movies". The Moving Image. 5 (2). University of Minnesota Press: 79–105. doi:10.1353/mov.2005.0034. S2CID 192079360.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (June 11, 2005). "After 33 years, Deep Throat, the film that shocked the US, gets its first British showing". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ^ "Porn film on 'landmark 100' list". BBC News. BBC. October 5, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ^ Nystedt, Dan; Martyn Williams (July 30, 2007). "Japanese Porn Industry Embraces Blu-Ray Disc". PC World. PC World Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ Richtel, Matt (January 22, 2007). "In Raw World of Sex Movies, High Definition Could Be a View Too Real". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

External links

[edit]- The History of Modern Pornography Patricia Davis, Ph.D., Simon Noble and Rebecca J. White (2010).

- Pan copulating with a goat (statue)

- More Moche pottery

- Erotic Daguerreotype

History of erotic depictions

View on GrokipediaPrehistoric and Ancient Foundations

Prehistoric Cave Art and Artifacts

The Venus of Willendorf, a 11.1 cm limestone figurine discovered in Austria, dates to approximately 30,000 years ago during the Upper Paleolithic Gravettian culture and features exaggerated breasts, hips, abdomen, and vulva with minimal facial or limb details.[6] Similar "Venus" figurines, numbering over 200 from sites across Eurasia including Germany, France, and Russia, consistently emphasize secondary sexual characteristics such as enlarged breasts and steatopygous buttocks, dated between 35,000 and 10,000 years ago.[4] These attributes have been hypothesized as representations of fertility or attractiveness, though direct evidence remains interpretive based on anatomical focus rather than contextual artifacts confirming ritual use.[7] Phallic artifacts from the same period underscore parallel male representations; a polished stone phallus, 20 cm long and 3 cm wide, from Hohle Fels Cave in Germany dates to about 28,000 years ago and shows signs of use as a tool or symbolic object.[8] Earlier examples include ivory phalluses from the Aurignacian culture around 40,000 years ago, indicating deliberate carving to mimic erect penises.[9] Such items, found in domestic or ritual contexts, suggest symbolic emphasis on reproductive anatomy predating settled societies. Cave engravings further evidence isolated sexual motifs; at Abri Castanet in France, vulva carvings on a collapsed rock shelter ceiling date to 37,000 years ago, among Europe's oldest known rock art, with no associated human figures but clear labial detailing.[10] Comparable vulva petroglyphs appear in sites like Chauvet Cave, where panels feature stylized female genitalia alongside animal depictions, potentially linking to reproductive symbolism in Paleolithic worldview.[11] These patterns across European sites, from portable figurines to fixed engravings, reflect recurrent focus on genitalia, consistent with empirical observations of human anatomical priorities in early symbolic expression.[12] Explicit depictions of intercourse remain rare and debated, with abstract engravings at sites like Gönnersdorf possibly interpreted as coupled forms but lacking definitive anatomical confirmation.[13]Mesopotamia and Ancient Near East

Erotic depictions in Mesopotamia emerged prominently in the form of terracotta plaques and figurines during the Sumerian and Babylonian periods, dating from approximately 2500 BCE onward, often portraying sexual acts in explicit detail. These artifacts, mass-produced in southern Mesopotamia, illustrate couples engaged in intercourse, such as missionary positions or rear-entry while the female figure drinks beer through a straw, reflecting everyday and ritualistic sexual practices.[14][15] Such plaques, small enough to hold in the palm, were common in Old Babylonian contexts around 2000–1500 BCE, suggesting widespread cultural acceptance of visualizing copulation without evident moral censure.[16] These representations intertwined with fertility cults centered on the goddess Inanna (Sumerian) or Ishtar (Akkadian), deity of sexual love, procreation, and warfare, whose worship involved cuneiform hymns and rituals emphasizing erotic union as a metaphor for agricultural abundance and divine favor. Cylinder seals from the third millennium BCE occasionally featured motifs of copulating animals or humanoid figures in sexualized poses, interpreted as invoking fertility in ritual sealing of documents or goods, though human intercourse appears more explicitly on later plaques.[17] Terracotta reliefs and nude female figurines, emphasizing exaggerated breasts and genitals, symbolized Ishtar's procreative powers and were deposited in domestic or temple settings to ensure household fertility.[18] Sacred eroticism manifested in practices like the hieros gamos, or sacred marriage rite, where the king symbolically united with a priestess embodying Inanna to ritually stimulate cosmic and earthly fertility, as recorded in Sumerian texts from the Early Dynastic period around 2400 BCE. While Greek historian Herodotus later described temple-based prostitution where women offered sex to strangers in Ishtar's honor, cuneiform evidence from Mesopotamian archives provides no direct corroboration for institutionalized sacred prostitution in the third or second millennia BCE, indicating such accounts may reflect later Hellenistic interpretations rather than indigenous practices.[19][20] Assyrian reliefs from the first millennium BCE shifted toward symbolic fertilization scenes, such as apkallu spirits pollinating sacred trees, representing abstracted erotic potency tied to kingship and abundance rather than overt human sexuality.[21] This integration of erotic imagery into religious and profane life underscores a causal link between sexual depiction and empirical concerns for reproduction and societal continuity, unburdened by later Abrahamic moral frameworks.Ancient Egypt

![Turin Satirical-Erotic Papyrus detail, Museo Egizio, Turin][float-right] In ancient Egyptian cosmology, sexual generation underpinned creation narratives, as seen in the Heliopolitan myth where the god Atum self-created the first divine pair, Shu and Tefnut, through masturbation, an act detailed in the Pyramid Texts inscribed in royal pyramids around 2400 BCE.[22] This motif emphasized auto-erotic fertility as a primal force, linking cosmic origins to the Nile's annual inundation and agricultural renewal, with Atum's ejaculate symbolizing the life-giving flood essential for sustenance and propagation.[23] Temple reliefs reinforced these themes through depictions of fertility deities, such as Min, portrayed with an erect phallus amid offerings of aphrodisiac lettuce, as in Edfu Temple inscriptions from the Ptolemaic period echoing earlier pharaonic traditions, underscoring male potency's role in ensuring cosmic and earthly abundance.[24] Human erotic depictions emerged more explicitly in the New Kingdom, exemplified by the Turin Erotic Papyrus (Papyrus Turin 55001), a Ramesside scroll from circa 1150 BCE discovered at Deir el-Medina, featuring vignettes of oversized women in acrobatic sexual positions with diminutive men, interspersed with satirical animal-human hybrids suggesting humorous commentary on social or ritual excess rather than mere titillation.[25] These scenes, blending obscenity with parody, likely served apotropaic or fertility-enhancing functions in workers' village contexts, aligning with broader Nile Valley emphases on reproduction for afterlife continuity, though their precise ritual intent remains debated among egyptologists due to fragmentary preservation.[26] Practical sexual knowledge grounded these symbolic arts, as evidenced in medical papyri like the Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE), which prescribed pessaries of acacia gum, dates, and honey—compounds with spermicidal properties—to prevent conception, reflecting empirical awareness of female biology and contraception amid concerns for family planning and health.61749-3/fulltext) Similarly, remedies for aphrodisiacs and impotence, including incantations invoking fertility gods, appear in texts like the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (Middle Kingdom, circa 1800 BCE), integrating magical and herbal interventions to sustain procreative vigor, thus bridging divine mythology with mortal physiology in service of societal stability and eternal renewal.[27]Classical Greece and Rome

In Classical Greece, erotic depictions featured extensively on Attic red-figure pottery from the late 6th to 5th centuries BCE, with explicit scenes appearing on approximately 7-10% of surviving vases used in symposia and daily life.[28] These vessels illustrated heterosexual intercourse, pederastic encounters between adult males and youths, and mythological seductions, such as Zeus pursuing mortals in animal forms, reflecting cultural norms of male dominance and mentorship through eros. Heterosexual acts predominated, often in standing or missionary positions, while male-male scenes emphasized intercrural or anal intercourse, underscoring the integration of sexuality in elite male socialization and athletic contexts. Vases from painters like the Shuvalov Painter, dated 430-420 BCE, depicted couples in explicit lovemaking, suggesting these images served both decorative and provocative functions in private gatherings.[29] Literary parallels emerged in Aristophanes' comedies, such as Lysistrata staged in 411 BCE, which employed bawdy sexual humor and themes of withheld intercourse to parody war and gender dynamics, mirroring pottery's candid eroticism.[30] These works highlighted societal hedonism tempered by philosophical discourse, as in Plato's Symposium (circa 385-370 BCE), where eros was debated as a path to virtue amid calls for self-control.[31] In Rome, erotic art proliferated in 1st-century CE wall frescoes at Pompeii, adorning private homes, baths, and brothels with diverse acts including group sex, oral-genital contact, and same-sex interactions between males or females.[32] The Suburban Baths' changing rooms featured sequential panels of cunnilingus, fellatio, and anal penetration involving multiple participants, likely catering to male patrons and indicating tolerance for varied pleasures in leisure settings.[33] Such imagery extended to artifacts like spintriae, small bronze tokens from circa 22-37 CE bearing explicit obverses and numerals I-XVI, possibly used as brothel counters to circumvent prohibitions on imperial coinage in sex trade venues.[34]

Ovid's Ars Amatoria, composed around 1 BCE, complemented visual erotica with didactic elegies instructing on seduction techniques, from flattery to physical advances, reflecting Roman urban libertinism despite Augustus' moral reforms.[35] These depictions collectively expressed hedonistic integration of sexuality into domestic and social spheres, balanced against elite advocacy for moderation in philosophical and literary traditions.

Non-Western Ancient and Medieval Traditions

Indian Subcontinent

Erotic depictions in the Indian subcontinent emerged within Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions, often intertwined with tantric philosophies emphasizing the union of opposites as a path to enlightenment. Ancient texts like Vātsyāyana's Kāma Sūtra, composed around the 3rd century CE, systematized erotic knowledge as one of the four aims of life (puruṣārthas), integrating descriptions of sexual positions, embraces, and caresses with ethical guidelines on courtship, marriage, and social conduct.[36][37] The treatise draws from earlier Kāmaśāstra traditions, framing physical pleasure (kāma) as complementary to duty (dharma) and prosperity (artha), rather than isolated indulgence, with empirical observations on human anatomy and psychology informing its classifications of body types and compatibility.[38] Temple sculptures from the medieval period exemplify this synthesis, particularly at Khajuraho in central India, where the Chandela dynasty constructed over 20 Hindu and Jain temples between approximately 950 and 1050 CE. These feature mithuna (amorous couples) and maithuna (explicit intercourse) carvings covering about 10% of the surfaces, integrated into narrative friezes alongside deities and daily life scenes.[39] In tantric contexts, such motifs symbolize the cosmic merger of male (purusha) and female (prakriti) principles, akin to Shiva-Shakti union, intended to evoke spiritual transcendence rather than provoke mere arousal, as per interpretations rooted in Āgama and Tantra texts.[40][41] Jain temples at the site, like those dedicated to Tirthankaras, incorporate similar sensual figures, reflecting tantra's adaptation across sects to harness erotic energy (kuṇḍalinī) for liberation.[42] Buddhist art from the subcontinent, influenced by Vajrayāna tantra around the 7th-12th centuries CE, occasionally depicts yab-yum (father-mother) pairings of deities in coitus, as seen in eastern Indian paṭa paintings and bronzes, representing the indivisibility of wisdom and compassion.[43] These differ from earlier sensual yakṣī (nature spirits) at sites like Sanchi (2nd century BCE), which emphasize fertility but avoid explicit acts, evolving into tantric esotericism to transmute desire into meditative focus.[44] During the Mughal era (16th-19th centuries), Persian-influenced miniatures shifted toward courtly sensuality, blending indigenous Hindu motifs with Islamic restraint in works like Ragamāla series and harem scenes, depicting lovers in gardens or alcoves to evoke shṛṅgāra (erotic sentiment) without the explicitness of temple art.[45] Examples include Deccani paintings of pleasure pavilions, where figures engage in embraces symbolizing romantic longing, reflecting elite patronage under emperors like Akbar and Jahangir, though less overt than pre-Mughal Hindu erotica due to cultural synthesis.[46][47]East Asia and Sinosphere

In East Asia, encompassing the Sinosphere cultures of China, Japan, and Korea, erotic depictions navigated a philosophical tension between Confucian doctrines prioritizing social harmony, filial piety, and restraint in sexual expression—often confining it to procreative marriage—and Daoist views framing intercourse as a vital exchange of yin-yang energies essential for personal vitality and cosmic equilibrium. This duality permitted private erotic art to thrive, typically in handscrolls, albums, or prints rationalized as instructional tools for health, fertility, or marital duty rather than mere titillation, with production peaking in periods of relative cultural openness despite official moralism. Such works emphasized technical positions, bodily fluids, and physiological benefits, drawing from ancient Daoist bedchamber manuals like those advocating semen retention to replenish brain essence (huanjing bunao).[48][49][50] Chinese erotic art crystallized in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), when chun gong hua—Spring Palace paintings—proliferated as illustrated handscrolls and albums depicting dozens of coital positions, often numbering 20 to 50 scenes per work, sourced from Han-era (206 BCE–220 CE) Daoist sexual treatises. These paintings, executed in ink and color on silk or paper, served didactic roles in imperial harems and bridal chambers, instructing on arousal techniques, orgasm control, and multi-partner scenarios to enhance male longevity and female pleasure, reflecting Daoist hydraulics of internal alchemy over Confucian prudery. Production involved anonymous court artists or literati, with extant examples like the Jieziyuan huazhuan influencing later variants, though Qing-era (1644–1912) censorship sporadically suppressed them.[51][50][52] In Japan, shunga ("spring pictures") emerged during the Edo period (1603–1868) as a subset of ukiyo-e woodblock prints, featuring 12-panel albums or triptychs with graphic intercourse scenes—frequently 8 to 12 per set—involving heterosexual, homosexual, and group acts, rendered with bold lines, vibrant colors, and comically enlarged genitals to evoke humor and ward off evil via apotropaic symbolism. Masters like Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) produced works such as The Dreams of the Fisherman's Wife (c. 1814), blending eroticism with fantasy elements like octopi, while emphasizing mutual ecstasy and ejaculatory abundance for fertility rites, diverging from imported Chinese restraint toward urban pleasure-quarter realism. Annual production reached thousands, circulated among samurai and merchants for private amusement and as talismans, tolerated under Tokugawa policies despite Confucian-influenced edicts against obscenity.[53][54][55] Korean chunhwa, or spring paintings, developed in the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), primarily as intimate albums by genre painters like Shin Yun-bok (c. 1758–after 1813) and Kim Hong-do (1745–c. 1818), illustrating explicit positions—often 10 to 20 per folio—in domestic settings, juxtaposed with Confucian moral annotations on conjugal duty to reconcile eroticism with neo-Confucian orthodoxy's emphasis on chastity and hierarchy. Influenced by Ming Chinese models imported via tribute trade, these works numbered fewer than 100 known complete sets, focusing on heterosexual marital sex with occasional voyeuristic or threesome motifs, produced clandestinely for elite collectors amid yangban scholars' public puritanism. Surviving examples, such as 18th-century ink-on-paper scrolls, highlight restrained yet vivid anatomy, prioritizing instructional harmony over exaggeration.[56]Mesoamerica and South America

In the Moche culture of ancient Peru, dating from approximately 100 to 800 CE, ceramic vessels known as huacos frequently featured explicit depictions of sexual acts, including anal intercourse, group sex, fellatio, and masturbation, often modeled in three-dimensional form.[57] At least 500 such erotic vessels have been recovered from tombs and sites, comprising a notable portion of the thousands of Moche ceramics unearthed, suggesting their use in ritual or ceremonial contexts tied to fertility and cosmology.[58] These artifacts portrayed sexual themes without apparent shame, potentially symbolizing agricultural renewal or sacrificial rites, as phallic-spouted vessels linked copulation motifs to themes of death and regeneration. Among the Maya of Mesoamerica during the Classic period (250–900 CE), painted cylindrical vases illustrated mythological scenes involving copulation, often between deities or elites in ritual settings, including auto-erotic acts such as masturbation by gods like Itzamnaaj to generate cosmic order.[59] These depictions, found on elite grave goods, integrated eroticism into narratives of creation and divine hierarchy, with nude figures engaging in intercourse sometimes alongside animals or supernatural beings to evoke fertility and supernatural potency.[59] Unlike more naturalistic portrayals elsewhere, Maya erotic art emphasized symbolic and hieroglyphic elements, subordinating explicitness to cosmological storytelling. In Andean cultures, including pre-Inca groups like Recuay (1–800 CE) and later Inca influences, phallic motifs appeared in stone sculptures and ceramics, serving as symbols in agricultural fertility rites to invoke rain, crop growth, and renewal.[60] Sites such as the Inca Uyo temple near Lake Titicaca featured monolithic phalli, interpreted as dedications to deities of reproduction and earth productivity, aligning erotic symbolism with cyclical agrarian calendars.[61] These artifacts, less focused on interpersonal acts than on abstracted genitalia, underscored a ritual emphasis on male potency as a mediator between human society and environmental forces.[62]Arabic and Islamic Cultures

In pre-Islamic Arabia, known as the Jahiliyyah period spanning roughly the 6th century CE, oral poetry served as the primary medium for erotic expression, often featuring vivid descriptions of female beauty, seduction, and physical desire within the structure of the qasida form. Poets like Imru' al-Qays (died circa 550 CE), whose Mu'allaqah is among the seven canonical hanging odes, detailed encounters with women, employing metaphors of tribal sensuality such as the curves of lovers' bodies likened to gazelles or tents in the desert, evoking arousal through deductive imagery of undressing and intimacy.[63] [64] These nasib (erotic preludes) contrasted with later Islamic norms by openly celebrating pre-marital liaisons and physical pleasure, reflecting a Bedouin culture where poetry competitions at fairs like 'Ukaz near Mecca amplified such themes for social prestige.[65] Physical artifacts, including stone carvings from Nabataean sites like Petra (circa 1st century BCE to 1st century CE), occasionally depicted nude or semi-nude figures suggesting fertility and sensuality, though explicit eroticism remained subordinate to poetry's dominance.[66] Following the rise of Islam in the 7th century CE, erotic depictions persisted in subtle, often secular or metaphorical forms within Persianate Islamic cultures, particularly in illuminated manuscripts of the Safavid era (1501–1736 CE). Artists produced miniatures illustrating romantic and erotic scenes from literary works, such as lovers in gardens or veiled embraces, navigating Sharia prohibitions against idolatry and explicit nudity by emphasizing stylized beauty and emotional longing over graphic acts. In the Haft Awrang ("Seven Thrones"), a collection of poems by Jami (died 1492 CE) illustrated during the Safavid period around 1556–1565 CE, folios depict courtly unions and sensual motifs, like banquets symbolizing marital intimacy, commissioned for patrons such as Prince Ibrahim Mirza to blend Sufi mysticism with aesthetic pleasure.[67] [68] Safavid wall paintings in private residences sometimes incorporated imported European erotic influences, portraying seminude women in domestic settings, indicating elite tolerance for such art in non-public spaces despite orthodox restrictions.[69] [70] Under Ottoman rule (1299–1922 CE), erotic art manifested in private manuscripts and miniatures, contrasting public adherence to Islamic law with underground elite traditions. Late 18th-century albums, such as those compiling poetry and prose erotica from the 1790s, featured detailed illustrations of intercourse, fellatio, and group scenes, drawn with technical finesse suggesting courtly or scholarly patronage, often anonymized to evade censorship.[71] [72] Hammam (bathhouse) tiles from the 16th–18th centuries occasionally included floral or figural motifs with subtle sensual undertones, evoking steamy communal nudity without overt sexuality, while Bektashi Sufi-influenced folios in Albanian Ottoman contexts preserved veiled homoerotic and heterosexual narratives in manuscript traditions.[73] These works highlight a duality: overt Sharia bans on visual pornography coexisted with tolerated private expressions in literature and art, prioritizing narrative discretion over prohibition.[66]European Developments from Medieval to Enlightenment

Medieval Period