Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Karakoram

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Karakoram | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Chinese | 喀喇昆仑山脉 | ||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Kālǎ Kūnlún shānmài | ||||||

| Literal meaning | "Kara-Kunlun mountain range" | ||||||

| |||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||

| Tibetan | ཁར་ཁོ་རུམ་རི | ||||||

| |||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||

| Uyghur | قاراقورام | ||||||

The Karakoram (/ˌkɑːrəˈkɔːrəm, ˌkær-/)[1] is a mountain range in the Kashmir region spanning the border of Pakistan, China, and India, with the northwestern extremity of the range extending to Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Most of the Karakoram mountain range is located within Pakistan's Gilgit-Baltistan region, the northern subdivision of Kashmir.

The mountain range begins in the Wakhan Corridor in Afghanistan in the west, encompasses the majority of Gilgit-Baltistan, controlled by Pakistan, and then extends into Ladakh, controlled by India, and Aksai Chin, controlled by China. It is part of the larger Trans-Himalayan mountain ranges.

The Karakoram is the second-highest mountain range on Earth and part of a complex of ranges that includes the Pamir Mountains, Hindu Kush, and the Indian Himalayas.[2][3] The range contains eighteen summits higher than 7,500 m (24,600 ft) in elevation, with four above 8,000 m (26,000 ft):[4][5][6] K2 (8,611 m (28,251 ft) AMSL) (the highest peak in the Karakorum and second-highest on Earth), Gasherbrum I, Broad Peak, and Gasherbrum II.

The range is about 500 km (311 mi) in length and is the most glaciated place on Earth outside the polar regions. The Siachen Glacier (76 km (47 mi) long) and Biafo Glacier (63 km (39 mi) long) are the second- and third-longest glaciers outside the polar regions.[7]

The Karakoram is bounded on the east by the Aksai Chin plateau, on the northeast by the edge of the Tibetan Plateau, and on the north by the river valleys of the Yarkand and Karakash rivers, beyond which lie the Kunlun Mountains. At the northwest corner are the Pamir Mountains. The southern boundary of the Karakoram is formed, west to east, by the Gilgit, Indus, and Shyok rivers, which separate the range from the northwestern end of the Himalaya range proper. These rivers flow northwest before making an abrupt turn southwestward towards the plains of Pakistan. Roughly in the middle of the Karakoram range is the Karakoram Pass, which was part of a historic trade route between Ladakh and Yarkand that is now inactive.

The Tashkurghan National Nature Reserve and the Pamir Wetlands National Nature Reserve in the Karalorun and Pamir mountains were nominated for inclusion in UNESCO in 2010 by the National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO and have been tentatively added to the list.[8]

Name

[edit]

Karakoram is a Turkic term meaning black gravel. The Central Asian traders originally applied the name to the Karakoram Pass.[9] Early European travelers, including William Moorcroft and George Hayward, started using the term for the range of mountains west of the pass, although they also used the term Muztagh (meaning, "Ice Mountain") for the range now known as Karakoram.[9][10] Later terminology was influenced by the Survey of India, whose surveyor, Thomas Montgomerie, in the 1850s, gave the labels K1 to K6 (K for Karakoram) to six high mountains visible from his station at Mount Haramukh in Kashmir Valley, codes extended further up to more than thirty.

In traditional Indian geography, the mountains were known as Krishnagiri (black mountains), Kanhagiri, and Kanheri.[11]

Exploration

[edit]Due to its altitude and ruggedness, the Karakoram is much less inhabited than parts of the Himalayas further east. European explorers first visited in the early 19th century, followed by British surveyors starting in 1856.

The Muztagh Pass was crossed in 1887 by the expedition of Colonel Francis Younghusband,[12] and the valleys above the Hunza River were explored by General Sir George K. Cockerill in 1892. Explorations in the 1910s and 1920s established most of the geography of the region.

The name Karakoram was used in the early 20th century, for example by Kenneth Mason,[9] for the range now known as the Baltoro Muztagh. The term is now used to refer to the entire range from the Batura Muztagh above Hunza in the west to the Saser Muztagh in the bend of the Shyok River in the east.

Floral surveys were carried out in the Shyok River catchment and from Panamik to Turtuk village by Chandra Prakash Kala during 1999 and 2000.[13][14]

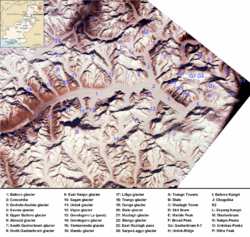

Geology and glaciers

[edit]The Karakoram is in one of the world's most geologically active areas, at the plate boundary between the Indo-Australian plate and the Eurasian plate.[15] A significant part, somewhere between 28 and 50 percent, of the Karakoram Range is glaciated, covering an area of more than 15,000 square kilometres or 5,800 square miles,[16] compared to between 8 and 12 percent of the Himalaya and 2.2 percent of the Alps.[17] Mountain glaciers may serve as an indicator of climate change, advancing and receding with long-term changes in temperature and precipitation. The Karakoram glaciers are slightly retreating,[18][19][20] unlike the Himalayas, where glaciers are losing mass at a significantly higher rate, many Karakoram glaciers are covered in a layer of rubble which insulates the ice from the warmth of the sun.[21] Where there is no such insulation, the rate of retreat is high.[22]

- Siachen Glacier

- Baltoro Glacier

- Hispar Glacier

- Batura Glacier

- Biafo Glacier

- Chogo Lungma Glacier

- Yinsugaiti Glacier

Ice Age

[edit]In the last ice age, a connected series of glaciers stretched from western Tibet to Nanga Parbat, and from the Tarim basin to the Gilgit District.[23][24][25] To the south, the Indus glacier was the main valley glacier, which flowed 120 kilometres (75 mi) down from the Nanga Parbat massif to 870 metres (2,850 ft) elevation.[23][26] In the north, the Karakoram glaciers joined those from the Kunlun Mountains and flowed down to 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) in the Tarim basin.[25][27]

While the current valley glaciers in the Karakoram reach a maximum length of 76 kilometres (47 mi), several of the ice-age valley glacier branches and main valley glaciers, had lengths up to 700 kilometres (430 mi). During the Ice Age, the glacier snowline was about 1,300 metres (4,300 ft) lower than today.[25][26]

Highest peaks

[edit]

- 1:K2

- 2:Gasherbrum I, K5

- 3:Broad Peak

- 4:Gasherbrum II, K4

- 5:Gasherbrum III, K3a

- 6:Gasherbrum IV, K3

- 7:Distaghil Sar

- 8:Kunyang Chhish

- 9:Masherbrum, K1

- 10:Batura Sar, Batura I

- 11:Rakaposhi

- 12:Batura II

- 13:Kanjut Sar

- 14:Saltoro Kangri, K10

- 15:Batura III

- 16: Saser Kangri I, K22

- 17:Chogolisa

- 18:Shispare

- 19:Trivor Sar

- 20:Skyang Kangri

- 21:Mamostong Kangri, K35

- 22:Saser Kangri II

- 23:Saser Kangri III

- 24:Pumari Chhish

- 25:Passu Sar

- 26:Yukshin Gardan Sar

- 27:Teram Kangri I

- 28:Malubiting

- 29:K12

- 30:Sia Kangri

- 31:Momhil Sar

- 32:Skil Brum

- 33:Haramosh Peak

- 34:Ghent Kangri

- 35:Ultar Sar

- 36:Rimo massif

- 37:Sherpi Kangri

- 38:Yazghil Dome South

- 39:Baltoro Kangri

- 40:Crown Peak

- 41:Baintha Brakk

- 42:Yutmaru Sar

- 43:K6

- 44:Muztagh Tower

- 45:Diran

- 46:Apsarasas Kangri I

- 47:Rimo III

- 48:Gasherbrum V

Here is a list for the highest peaks of the Karakoram. Included are some of the mountains named with a K code, the most famous of which is the K2 (mountain).

| Mountain | Height[28] | Ranked | K code | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K2 | 8,611 metres (28,251 ft) | 2 | K2 | |

| Gasherbrum I | 8,080 metres (26,510 ft) | 11 | K5 | |

| Broad Peak | 8,051 metres (26,414 ft) | 12 | ||

| Gasherbrum II | 8,034 metres (26,358 ft) | 13 | K4 | |

| Gasherbrum III | 7,952 metres (26,089 ft) | K3a | ||

| Gasherbrum IV | 7,925 metres (26,001 ft) | 17 | K3 | |

| Distaghil Sar | 7,885 metres (25,869 ft) | 19 | ||

| Kunyang Chhish | 7,852 metres (25,761 ft) | 21 | ||

| Masherbrum I | 7,821 metres (25,659 ft) | 22 | K1 | |

| Batura I | 7,795 metres (25,574 ft) | 25 | ||

| Rakaposhi | 7,788 metres (25,551 ft) | 26 | ||

| Batura II | 7,762 metres (25,466 ft) | |||

| Kanjut Sar | 7,760 metres (25,460 ft) | 28 | ||

| Saltoro Kangri I | 7,742 metres (25,400 ft) | 31 | K10 | |

| Batura III | 7,729 metres (25,358 ft) | |||

| Saltoro Kangri II | 7,705 metres (25,279 ft) | K11 | ||

| Saser Kangri I | 7,672 metres (25,171 ft) | 35 | K22 | |

| Chogolisa | 7,665 metres (25,148 ft) | 36 | ||

| Shispare Sar | 7,611 metres (24,970 ft) | 38 | ||

| Trivor Sar | 7,577 metres (24,859 ft) | 39 | ||

| Skyang Kangri | 7,545 metres (24,754 ft) | 43 | ||

| Mamostong Kangri | 7,516 metres (24,659 ft) | 47 | K35 | |

| Saser Kangri II | 7,513 metres (24,649 ft) | 48 | ||

| Saser Kangri III | 7,495 metres (24,590 ft) | 51 | ||

| Pumari Chhish | 7,492 metres (24,580 ft) | 53 | ||

| Passu Sar | 7,478 metres (24,534 ft) | 54 | ||

| Yukshin Gardan Sar | 7,469 metres (24,505 ft) | 55 | ||

| Teram Kangri I | 7,462 metres (24,482 ft) | 56 | ||

| Malubiting | 7,458 metres (24,469 ft) | 58 | ||

| K12 or Saitang Peak | 7,428 metres (24,370 ft) | 61 | K12 | |

| Sia Kangri | 7,422 metres (24,350 ft) | 63 | ||

| Skilma Gangri or Ghursay Kangri II | 7,422 metres (24,350 ft) | K8 | ||

| Momhil Sar | 7,414 metres (24,324 ft) | 64 | ||

| Skil Brum | 7,410 metres (24,310 ft) | 66 | ||

| Haramosh Peak | 7,409 metres (24,308 ft) | 67 | ||

| Ghent Kangri | 7,401 metres (24,281 ft) | 69 | ||

| Ultar Peak | 7,388 metres (24,239 ft) | 70 | ||

| Rimo I | 7,385 metres (24,229 ft) | 71 | ||

| Sherpi Kangri | 7,380 metres (24,210 ft) | 74 | ||

| Bojohagur Duanasir | 7,329 metres (24,045 ft) | |||

| Yazghil Dome South | 7,324 metres (24,029 ft) | |||

| Baltoro Kangri | 7,312 metres (23,990 ft) | 81 | ||

| Crown Peak | 7,295 metres (23,934 ft) | 83 | ||

| Baintha Brakk | 7,285 metres (23,901 ft) | 86 | ||

| Yutmaru Sar | 7,283 metres (23,894 ft) | 87 | ||

| Baltistan Peak | 7,282 metres (23,891 ft) | 88 | K6 | |

| Muztagh Tower | 7,273 metres (23,862 ft) | 90 | ||

| Diran | 7,266 metres (23,839 ft) | 92 | ||

| Apsarasas Kangri I | 7,243 metres (23,763 ft) | 95 | ||

| Rimo III | 7,233 metres (23,730 ft) | 97 | ||

| Gasherbrum V | 7,147 metres (23,448 ft) | |||

| Link Sar | 7,041 metres (23,100 ft) | |||

| Gamba Gangri | 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) (approx) | K9 | ||

| Gomgma Gangri | 6,934 metres (22,749 ft) | K7 | ||

| Dansam Peak | 6,666 metres (21,870 ft) | K13 | ||

| Paiju Peak | 6,610 metres (21,686 ft) | |||

| Pastan Kangri | 6,523 metres (21,401 ft) | K25 |

The majority of the highest peaks are in the Gilgit–Baltistan region administered by Pakistan. Baltistan has more than 100 mountain peaks exceeding 6,100 metres (20,000 ft) height from sea level.

Subranges

[edit]

The naming and division of the various subranges of the Karakoram is not universally agreed upon. However, the following is a list of the most important subranges, following Jerzy Wala.[29] The ranges are listed roughly west to east.

Passes

[edit]Legend:

![]() 1:Sia La,

1:Sia La,

![]() 2:Bilafond La,

2:Bilafond La,

![]() 3:Gyong La,

3:Gyong La,

![]() 4:Sasser Pass,

4:Sasser Pass,

![]() 5:Burji La,

5:Burji La,

![]() 6:Machulo La,

6:Machulo La,

![]() 7:Naltar Pass,

7:Naltar Pass,

![]() 8:Hispar Pass,

8:Hispar Pass,

![]() 9:Shimshal Pass,

9:Shimshal Pass,

![]() 10:Karakoram Pass,

10:Karakoram Pass,

![]() 11:Turkistan La Pass,

11:Turkistan La Pass,

![]() 12:Windy Gap,

12:Windy Gap,

![]() 13:Mustagh Pass,

13:Mustagh Pass,

![]() 14:Sarpo Laggo Pass,

14:Sarpo Laggo Pass,

![]() 15:Khunjerab Pass,

15:Khunjerab Pass,

![]() 16:Mutsjliga Pass,

16:Mutsjliga Pass,

![]() 17:Mintaka Pass,

17:Mintaka Pass,

![]() 18:Kilik Pass

18:Kilik Pass

Passes from west to east are:

- Dandala Pass is the most important and earlier pass. It starts from Ghursay saitang city to Yarqand in China. It is the main trade route between Khaplu, Ladakh, Kharmang to Yarqand, China.

- Kilik Pass

- Mintaka Pass

- Khunjerab Pass is the highest paved international border crossing at 4,693 m (15,397 ft). It serves the China-Pakistan Friendship Highway, the "8th world wonder".[30]

- Shimshal Pass

- Mustagh Pass

- Karakoram Pass

- Sasser Pass

- Naltar Pass or Pakora Pass[31]

The Khunjerab Pass is the only motorable pass across the range. The Shimshal Pass (which does not cross an international border) is the only other pass still in regular use.

Cultural references

[edit]The Karakoram mountain range has been referred to in a number of novels and movies. Rudyard Kipling refers to the Karakoram mountain range in his novel Kim, which was first published in 1900. Marcel Ichac made a film titled Karakoram, chronicling a French expedition to the range in 1936. The film won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival of 1937. Greg Mortenson details the Karakoram, and specifically K2 and the Balti, extensively in his book Three Cups of Tea, about his quest to build schools for children in the region. K2 Kahani (The K2 Story) by Mustansar Hussain Tarar describes his experiences at K2 base camp.[32]

See also

[edit]- Karakoram Highway

- List of mountain ranges of the world

- List of highest mountains (a list of mountains above 7,200 m (23,600 ft))

- Mount Imeon

- Naltar Valley

- Trans-Karakoram Tract

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Karakoram". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Karakoram Range at the Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Hindu Kush Himalayan Region". International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Shukurov, The Natural Environment of Central and South Asia 2005, p. 512.

- ^ Voiland, Adam (2013). "The Eight-Thousanders". NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "Mountains". Planet Earth. Episode 3. BBC.

- ^ Tajikistan's Fedchenko Glacier is 77 km (48 mi) long. Baltoro and Batura Glaciers in the Karakoram are 57 km (35 mi) long, as is Bruggen or Pio XI Glacier in southern Chile. Measurements are from recent imagery, generally supplemented with Russian 1:200,000 scale topographic mapping as well as Jerzy Wala,Orographical Sketch Map: Karakoram: Sheets 1 & 2, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich, 1990.

- ^ "Karakorum-Pamir". UNESCO. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Mason, Kenneth (1928). Exploration of the Shaksgam Valley and Aghil ranges, 1926. Asian Educational Services. p. 72. ISBN 978-81-206-1794-0.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Close C, Burrard S, Younghusband F, et al. (1930). "Nomenclature in the Karakoram: Discussion". The Geographical Journal. 76 (2). Blackwell Publishing: 148–158. Bibcode:1930GeogJ..76..148C. doi:10.2307/1783980. JSTOR 1783980.

- ^ Kohli, M.S. (2002), Mountains of India: Tourism, Adventure and Pilgrimage, Indus Publishing, p. 22, ISBN 978-81-7387-135-1

- ^ French, Patrick. (1994). Younghusband: The Last Great Imperial Adventurer, pp. 53, 56-60. HarperCollinsPublishers, London. Reprint (1995): Flamingo. London. ISBN 0-00-637601-0.

- ^ Kala, Chandra Prakash (2005). "Indigenous Uses, Population Density, and Conservation of Threatened Medicinal Plants in Protected Areas of the Indian Himalayas". Conservation Biology. 19 (2): 368–378. Bibcode:2005ConBi..19..368K. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00602.x. S2CID 85324142.

- ^ Kala, Chandra Prakash (2005). "Health traditions of Buddhist community and role of amchis in trans-Himalayan region of India" (PDF). Current Science. 89 (8): 1331.

- ^ "Geological evolution of the Karakoram ranges". Italian Journal of Geosciences. 130 (2): 147–159. 2011. doi:10.3301/IJG.2011.08.

- ^ Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide; Khan, Asif (2019). "Early twenty-first century glacier mass losses in the Indus Basin constrained by density assumptions". Journal of Hydrology. 574: 467–475. Bibcode:2019JHyd..574..467M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.04.057.

- ^ Gansser (1975). Geology of the Himalayas. London: Interscience Publishers.

- ^ Gallessich, Gail (2011). "Debris on certain Himalayan glaciers may prevent melting". sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- ^ Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide (2016). "Changes in the ablation zones of glaciers in the western Himalaya and the Karakoram between 1972 and 2015". Remote Sensing of Environment. 187: 505–512. Bibcode:2016RSEnv.187..505M. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2016.10.034.

- ^ Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide; Nüsser, Marcus (2019). "No significant mass loss in the glaciers of Astore Basin (North-Western Himalaya), between 1999 and 2016". Journal of Glaciology. 65 (250): 270–278. Bibcode:2019JGlac..65..270M. doi:10.1017/jog.2019.5.

- ^ Muhammad, Sher; Tian, Lide; Ali, Shaukat; Latif, Yasir; Wazir, Muhammad Atif; Goheer, Muhammad Arif; Saifullah, Muhammad; Hussain, Iqtidar; Shiyin, Liu (2020). "Thin debris layers do not enhance melting of the Karakoram glaciers". Science of the Total Environment. 746 141119. Bibcode:2020ScTEn.74641119M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141119. PMID 32763605.

- ^ Veettil, B.K. (2012). "A Remote sensing approach for monitoring debris-covered glaciers in the high altitude Karakoram Himalayas". International Journal of Geomatics and Geosciences. 2 (3): 833–841.

- ^ a b Kuhle, M. (1988). "The Pleistocene Glaciation of Tibet and the Onset of Ice Ages- An Autocycle Hypothesis.Tibet and High Asia. Results of the Sino-German Joint Expeditions (I)". GeoJournal. 17 (4): 581–596. doi:10.1007/BF00209444. S2CID 129234912.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (2006). "The Past Hunza Glacier in Connection with a Pleistocene Karakoram Ice Stream Network during the Last Ice Age (Würm)". In Kreutzmann, H.; Saijid, A. (eds.). Karakoram in Transition. Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press. pp. 24–48.

- ^ a b c Kuhle, M. (2011). "The High Glacial (Last Ice Age and Last Glacial Maximum) Ice Cover of High and Central Asia, with a Critical Review of Some Recent OSL and TCN Dates". In Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P.L.; Hughes, P.D. (eds.). Quaternary Glaciation – Extent and Chronology, A Closer Look. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV. pp. 943–965. (glacier maps downloadable)

- ^ a b Kuhle, M. (2001). "Tibet and High Asia (VI): Glaciogeomorphology and Prehistoric Glaciation in the Karakoram and Himalaya". GeoJournal. 54 (1–4): 109–396. doi:10.1023/A:1021307330169.

- ^ Kuhle, M. (1994). "Present and Pleistocene Glaciation on the North-Western Margin of Tibet between the Karakoram Main Ridge and the Tarim Basin Supporting the Evidence of a Pleistocene Inland Glaciation in Tibet. Tibet and High Asia. Results of the Sino-German and Russian-German Joint Expeditions (III)". GeoJournal. 33 (2/3): 133–272. doi:10.1007/BF00812877. S2CID 189882345.

- ^ For Nepal, the heights indicated on the Nepal Topographic Maps are followed. For China and the Baltoro Karakoram, the heights are those of Mi Desheng's "The Maps of Snow Mountains in China". For the Hispar Karakoram the heights on a Russian 1:100,000 topo map of "Hispar area expeditions". Archived from the original on 27 April 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Jerzy Wala, Orographical Sketch Map of the Karakoram, Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, Zurich, 1990.

- ^ Shea, Samantha (8 September 2023). "The Road that's the Eighth World Wonder". BBC.

- ^ shuaib (18 August 2019). "Naltar Valley: Heaven on Earth". Mehmaan Resort. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Tarar, Mustansar Hussain (1994). K2 kahani. Lahore: Sang-e-Meel (published in Urdu). p. 179. ISBN 969-35-0523-9. OL 18941738M.

Sources

[edit]- Curzon, George Nathaniel. 1896. The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. Royal Geographical Society, London. Reprint: Elibron Classics Series, Adamant Media Corporation. 2005. ISBN 1-4021-5983-8 (pbk); ISBN 1-4021-3090-2 (hbk).

- Kipling, Rudyard 2002. Kim (novel); ed. by Zohreh T. Sullivan. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 039396650X—This is the most extensive critical modern edition with footnotes, essays, maps, etc.

- Mortenson, Greg and Relin, David Oliver. 2008. Three Cups of Tea. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-103426-3 (pbk); Viking Books ISBN 978-0-670-03482-6 (hbk); Tantor Media ISBN 978-1-4001-5251-3 (MP3 CD).

- Kreutzmann, Hermann, Karakoram in Transition: Culture, Development, and Ecology in the Hunza Valley, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-547210-3.

- Shukurov, E. (2005), "The Natural Environment of Central and South Asia" (PDF), in Chahryar Adle (ed.), History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. VI – Towards the contemporary period: from the mid-nineteenth to the end of the twentieth century, UNESCO, pp. 480–514, ISBN 978-92-3-103985-0

Further reading

[edit]- Dainelli, G. (1932). A Journey to the Glaciers of the Eastern Karakoram. The Geographical Journal, 79(4), 257–268.

External links

[edit]- Blankonthemap The Northern Kashmir Website

- Pakistan's Northern Areas dilemma

- Great Karakorams – images on Flickr

Karakoram

View on GrokipediaEtymology

Name and Historical Designations

The name Karakoram originates from Turkic languages, where it literally translates to "black gravel," a reference to the dark scree and morainal deposits characteristic of the region's passes and valleys.[5][8] Central Asian traders, including Uyghur and other Turkic-speaking groups traversing the Silk Road, first applied the term specifically to the Karakoram Pass, a high-altitude route connecting the Tarim Basin in present-day Xinjiang, China, to the Upper Indus Valley in northern Pakistan, used for commerce and migration as early as the 1st century CE.[8] By the 19th century, European surveyors and explorers extended the designation from the pass to the broader mountain range during systematic mapping efforts. British surveyor Thomas George Montgomerie, working from the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in the 1850s and 1860s, labeled prominent peaks visible from his stations as "K1," "K2," and so on, explicitly denoting the "K" for Karakoram to distinguish them from Himalayan features.[9] This nomenclature formalized the range's identity separate from adjacent systems like the Himalayas, though earlier designations in Persian or Indic texts often subsumed it under vague terms for northern barriers without distinct naming. No specific pre-Turkic or ancient Sanskrit designations for the full range appear in surviving records, reflecting its relative isolation from lowland civilizations until modern exploration.Geography

Location and Political Boundaries

The Karakoram mountain range lies in Central Asia, forming the northwestern extension of the greater Himalayan system and situated between the Pamir Mountains to the northwest and the Tibetan Plateau to the southeast. It primarily spans the border regions of Pakistan, India, and China, with its northwestern extremities extending into Afghanistan and Tajikistan, where the borders of these five countries converge.[10][5] The range measures approximately 500 km in length and covers an area of about 207,000 square kilometers.[5][3] The majority of the Karakoram, including major features such as the Baltoro Glacier and K2, falls within Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan, a region under federal control since 1947. Northern sections align with China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, facilitating connectivity via the Karakoram Pass and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor infrastructure, including the Karakoram Highway completed in 1979.[5] Southeastern portions, encompassing the Saltoro Range and Siachen Glacier, are administered by India as part of the union territory of Ladakh, following India's military occupation during Operation Meghdoot on April 13, 1984, which preempted Pakistani advances in the area.[11] This control remains contested by Pakistan as part of the unresolved Kashmir territorial dispute originating from the 1947 partition.[12] Minor western segments intrude into Afghanistan's narrow Wakhan Corridor, a strip ceded in the 19th century to buffer British India from Russia, and Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, though these areas involve limited territorial overlap and minimal human settlement due to extreme altitude and isolation.[10] The convergence of international boundaries in the Karakoram underscores its geopolitical sensitivity, with no formal delineation in some high-altitude zones beyond the Actual Ground Position Line established post-1984 in the Siachen sector.[11]Physical Extent and Subranges

The Karakoram mountain range spans the borders of Pakistan, India, and China, with extremities extending into Afghanistan and Tajikistan.[13] It forms the northwestern continuation of the Himalayan system, extending from the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region westward into the Tibetan Plateau eastward.[14] The range lies between the Indus River valley to the south and the Tarim Basin to the north, separating the upper Indus watershed from the high Tibetan Plateau.[3] The Karakoram is subdivided into multiple subranges, each characterized by distinct clusters of high peaks and glacial systems. Key subranges include the Baltoro Muztagh, which hosts K2 and several other eight-thousanders along the Pakistan-China border; the Saltoro Mountains in the southwestern sector, notable for peaks like Saltoro Kangri; and the Siachen Muztagh, encompassing the Siachen Glacier area.[3] Eastern extensions feature the Rimo Muztagh and South Ghujerab Mountains, while central areas comprise the Panmah Muztagh, Masherbrum Mountains, and Biafo Group.[3] These divisions reflect variations in topography, with the central and eastern subranges generally exhibiting the highest elevations and densest glaciation.[15]Highest Peaks and Topography

The Karakoram Range hosts four of the fourteen mountains exceeding 8,000 meters worldwide: K2 at 8,611 meters, Gasherbrum I at 8,080 meters, Broad Peak at 8,051 meters, and Gasherbrum II at 8,035 meters.[16] K2, the second-highest peak on Earth, rises dramatically over 3,000 meters above the surrounding glacial valleys on the Pakistan-China border.[17] These summits, along with over 60 peaks above 7,000 meters, cluster primarily in the central subranges like the Baltoro Muztagh and Gasherbrum groups.[2]| Peak | Height (m) | Prominence (m) | First Ascent Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| K2 | 8,611 | 4,020 | 1954 |

| Gasherbrum I | 8,080 | 2,155 | 1958 |

| Broad Peak | 8,051 | 1,701 | 1957 |

| Gasherbrum II | 8,035 | 1,523 | 1956 |

| Gasherbrum IV | 7,925 | 2,325 | 1958 |