Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

View on Wikipedia

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor also known as class E basic helix-loop-helix protein 32 or bHLHe32 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MITF gene.

MITF is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor involved in lineage-specific pathway regulation of many types of cells including melanocytes, osteoclasts, and mast cells.[5] The term "lineage-specific", since it relates to MITF, means genes or traits that are only found in a certain cell type. Therefore, MITF may be involved in the rewiring of signaling cascades that are specifically required for the survival and physiological function of their normal cell precursors.[6]

MITF, together with transcription factor EB (TFEB), TFE3 and TFEC, belong to a subfamily of related bHLHZip proteins, termed the MiT-TFE family of transcription factors.[7][8] The factors are able to form stable DNA-binding homo- and heterodimers.[9] The gene that encodes for MITF resides at the mi locus in mice,[10] and its protumorogenic targets include factors involved in cell death, DNA replication, repair, mitosis, microRNA production, membrane trafficking, mitochondrial metabolism, and much more.[11] Mutation of this gene results in deafness, bone loss, small eyes, and poorly pigmented eyes and skin.[12] In human subjects, because it is known that MITF controls the expression of various genes that are essential for normal melanin synthesis in melanocytes, mutations of MITF can lead to diseases such as melanoma, Waardenburg syndrome, and Tietz syndrome.[13] Its function is conserved across vertebrates, including in fishes such as zebrafish[14] and Xiphophorus.[15]

An understanding of MITF is necessary to understand how certain lineage-specific cancers and other diseases progress. In addition, current and future research can lead to potential avenues to target this transcription factor mechanism for cancer prevention.[16]

Clinical significance

[edit]Mutations

[edit]As mentioned above, changes in MITF can result in serious health conditions. For example, mutations of MITF have been implicated in both Waardenburg syndrome and Tietz syndrome.

Waardenburg syndrome is a rare genetic disorder. Its symptoms include deafness, minor defects, and abnormalities in pigmentation.[17] Mutations in the MITF gene have been found in certain patients with Waardenburg syndrome, type II. Mutations that change the amino acid sequence of that result in an abnormally small MITF are found. These mutations disrupt dimer formation, and as a result cause insufficient development of melanocytes.[citation needed] The shortage of melanocytes causes some of the characteristic features of Waardenburg syndrome.[citation needed]

Tietz syndrome, first described in 1923, is a congenital disorder often characterized by deafness and leucism. Tietz is caused by a mutation in the MITF gene.[18] The mutation in MITF deletes or changes a single amino acid base pair specifically in the base motif region of the MITF protein. The new MITF protein is unable to bind to DNA and melanocyte development and subsequently melanin production is altered. A reduced number of melanocytes can lead to hearing loss, and decreased melanin production can account for the light skin and hair color that make Tietz syndrome so noticeable.[13]

Melanoma

[edit]Melanocytes are commonly known as cells that are responsible for producing the pigment melanin which gives coloration to the hair, skin, and nails. The exact mechanisms of how melanocytes become cancerous are relatively unclear, but there is ongoing research to gain more information about the process. For example, it has been uncovered that the DNA of certain genes is often damaged in melanoma cells, most likely as a result of damage from UV radiation, and in turn increases the likelihood of developing melanoma.[19] Specifically, it has been found that a large percentage of melanomas have mutations in the B-RAF gene which leads to melanoma by causing an MEK-ERK kinase cascade when activated.[20] In addition to B-RAF, MITF is also known to play a crucial role in melanoma progression. Since it is a transcription factor that is involved in the regulation of genes related to invasiveness, migration, and metastasis, it can play a role in the progression of melanoma.

Target genes

[edit]MITF recognizes E-box (CAYRTG) and M-box (TCAYRTG or CAYRTGA) sequences in the promoter regions of target genes. Known target genes (confirmed by at least two independent sources) of this transcription factor include,

| ACP5[21][22] | BCL2[22][23] | BEST1[22][24] | BIRC7[22][25] |

| CDK2[22][26] | CLCN7[22][27] | DCT[22][28] | EDNRB[22][29] |

| GPNMB[22][30] | GPR143[22][31] | MC1R[22][32] | MLANA[22][33] |

| OSTM1[22][27] | RAB27A[22][34] | SILV[22][33] | SLC45A2[22][35] |

| TBX2[22][36] | TRPM1[22][37] | TYR[22][38] | TYRP1[22][39] |

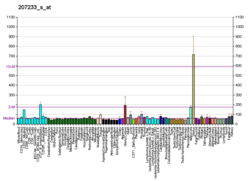

Additional genes identified by a microarray study (which confirmed the above targets) include the following,[22]

| MBP | TNFRSF14 | IRF4 | RBM35A |

| PLA1A | APOLD1 | KCNN2 | INPP4B |

| CAPN3 | LGALS3 | GREB1 | FRMD4B |

| SLC1A4 | TBC1D16 | GMPR | ASAH1 |

| MICAL1 | TMC6 | ITPKB | SLC7A8 |

The LysRS-Ap4A-MITF signaling pathway

[edit]The LysRS-Ap4A-MITF signaling pathway was first discovered in mast cells, in which, the A mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is activated upon allergen stimulation. The binding of immunoglobulin E to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) provides the stimulus that starts the cascade.

Lysyl-tRNA synthetase (LysRS) normally resides in the multisynthetase complex. This complex consists of nine different aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and three scaffold proteins and has been termed the "signalosome" due to its non-catalytic signalling functions.[40] After activation, LysRS is phosphorylated on Serine 207 in a MAPK-dependent manner.[41] This phosphorylation causes LysRS to change its conformation, detach from the complex and translocate into the nucleus, where it associates with the encoding histidine triad nucleotide–binding protein 1 (HINT1) thus forming the MITF-HINT1 inhibitory complex. The conformational change also switches LysRS activity from aminoacylation of Lysine tRNA to diadenosine tetraphosphate (Ap4A) production. Ap4A, which is an adenosine joined to another adenosine through a 5'-5'tetraphosphate bridge, binds to HINT1 and this releases MITF from the inhibitory complex, allowing it to transcribe its target genes.[42] Specifically, Ap4A causes a polymerization of the HINT1 molecule into filaments. The polymerization blocks the interface for MITF and thus prevents the binding of the two proteins. This mechanism is dependent on the precise length of the phosphate bridge in the Ap4A molecule so other nucleotides such as ATP or AMP will not affect it.[43]

MITF is also an integral part of melanocytes, where it regulates the expression of a number of proteins with melanogenic potential. Continuous expression of MITF at a certain level is one of the necessary factors for melanoma cells to proliferate, survive and avoid detection by host immune cells through the T-cell recognition of the melanoma-associated antigen (melan-A).[44] Post-translational modifications of the HINT1 molecules have been shown to affect MITF gene expression as well as the binding of Ap4A.[45] Mutations in HINT1 itself have been shown to be the cause of axonal neuropathies.[46] The regulatory mechanism relies on the enzyme diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase, a member of the Nudix type 2 enzymatic family (NUDT2), to cleave Ap4A, allow the binding of HINT1 to MITF and thus suppress the expression of the MITF transcribed genes.[47] NUDT2 itself has also been shown to be associated with human breast carcinoma, where it promotes cellular proliferation.[48] The enzyme is 17 kDa large and can freely diffuse between the nucleus and cytosol explaining its presence in the nucleus. It has also been shown to be actively transported into the nucleus by directly interacting with the N-terminal domain of importin-β upon immunological stimulation of the mast cells. Growing evidence is pointing to the fact that the LysRS-Ap4A-MITF signalling pathway is in fact an integral aspect of controlling MITF transcriptional activity.[49]

Activation of the LysRS-Ap4A-MITF signalling pathway by isoproterenol has been confirmed in cardiomyocytes. A heart specific isoform of MITF is a major regulator of cardiac growth and hypertrophy responsible for heart growth and for the physiological response of the cardiomyocytes to beta-adrenergic stimulation.[50]

Phosphorylation

[edit]MITF is phosphorylated on several serine and tyrosine residues.[51][52][53] Serine phosphorylation is regulated by several signaling pathways including MAPK/BRAF/ERK, receptor tyrosine kinase KIT, GSK-3 and mTOR. In addition, several kinases including PI3K, AKT, SRC and P38 are also critical activators of MITF phosphorylation.[54] In contrast, tyrosine phosphorylation is induced by the presence of the KIT oncogenic mutation D816V.[53] This KITD816V pathway is dependent on SRC protein family activation signaling. The induction of serine phosphorylation by the frequently altered MAPK/BRAF pathway and the GSK-3 pathway in melanoma regulates MITF nuclear export and thereby decreasing MITF activity in the nucleus.[55] Similarly, tyrosine phosphorylation mediated by the presence of the KIT oncogenic mutation D816V also increases the presence of MITF in the cytoplasm.[53]

Interactions

[edit]Most transcription factors function in cooperation with other factors by protein–protein interactions. Association of MITF with other proteins is a critical step in the regulation of MITF-mediated transcriptional activity. Some commonly studied MITF interactions include those with MAZR, PIAS3, Tfe3, hUBC9, PKC1, and LEF1. Looking at the variety of structures gives insight into MITF's varied roles in the cell.

The Myc-associated zinc-finger protein related factor (MAZR) interacts with the Zip domain of MITF. When expressed together, both MAZR and MITF increase promoter activity of the mMCP-6 gene. MAZR and MITF together transactivate the mMCP-6 gene. MAZR also plays a role in the phenotypic expression of mast cells in association with MITF.[56]

PIAS3 is a transcriptional inhibitor that acts by inhibiting STAT3's DNA binding activity. PIAS3 directly interacts with MITF, and STAT3 does not interfere with the interaction between PIAS3 and MITF. PIAS3 functions as a key molecule in suppressing the transcriptional activity of MITF. This is important when considering mast cell and melanocyte development.[57]

MITF, TFE3 and TFEB are part of the basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper family of transcription factors.[7][9] Each protein encoded by the family of transcription factors can bind DNA. MITF is necessary for melanocyte and eye development and new research suggests that TFE3 is also required for osteoclast development, a function redundant of MITF. The combined loss of both genes results in severe osteopetrosis, pointing to an interaction between MITF and other members of its transcription factor family.[58][59] In turn, TFEB has been termed as the master regulator of lysosome biogenesis and autophagy.[60][61] Interestingly, MITF, TFEB and TFE3 separate roles in modulating starvation-induced autophagy have been described in melanoma.[62] Moreover, MITF and TFEB proteins, directly regulate each other's mRNA and protein expression while their subcellular localization and transcriptional activity are subject to similar modulation, such as the mTOR signaling pathway.[8]

UBC9 is a ubiquitin conjugating enzyme whose proteins associates with MITF. Although hUBC9 is known to act preferentially with SENTRIN/SUMO1, an in vitro analysis demonstrated greater actual association with MITF. hUBC9 is a critical regulator of melanocyte differentiation. To do this, it targets MITF for proteasome degradation.[63]

Protein kinase C-interacting protein 1 (PKC1) associates with MITF. Their association is reduced upon cell activation. When this happens MITF disengages from PKC1. PKC1 by itself, found in the cytosol and nucleus, has no known physiological function. It does, however, have the ability to suppress MITF transcriptional activity and can function as an in vivo negative regulator of MITF induced transcriptional activity.[64]

The functional cooperation between MITF and the lymphoid enhancing factor (LEF-1) results in a synergistic transactivation of the dopachrome tautomerase gene promoter, which is an early melanoblast marker. LEF-1 is involved in the process of regulation by Wnt signaling. LEF-1 also cooperates with MITF-related proteins like TFE3. MITF is a modulator of LEF-1, and this regulation ensures efficient propagation of Wnt signals in many cells.[28]

Translational regulation

[edit]Translational regulation of MITF is still an unexplored area with only two peer-reviewed papers (as of 2019) highlighting the importance.[65][66] During glutamine starvation of melanoma cells ATF4 transcripts increases as well as the translation of the mRNA due to eIF2α phosphorylation.[65] This chain of molecular events leads to two levels of MITF suppression: first, ATF4 protein binds and suppresses MITF transcription and second, eIF2α blocks MITF translation possibly through the inhibition of eIF2B by eIF2α.

MITF can also be directly translationally modified by the RNA helicase DDX3X.[66] The 5' UTR of MITF contains important regulatory elements (IRES) that is recognized, bound and activated by DDX3X. Although, the 5' UTR of MITF only consists of a nucleotide stretch of 123-nt, this region is predicted to fold into energetically favorable RNA secondary structures including multibranched loops and asymmetric bulges that is characteristics of IRES elements. Activation of this cis-regulatory sequences by DDX3X promotes MITF expression in melanoma cells.[66]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000187098 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000035158 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Hershey CL, Fisher DE (April 2004). "Mitf and Tfe3: members of a b-HLH-ZIP transcription factor family essential for osteoclast development and function". Bone. 34 (4): 689–96. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2003.08.014. PMID 15050900.

- ^ Garraway LA, Sellers WR (August 2006). "Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 6 (8): 593–602. doi:10.1038/nrc1947. PMID 16862190. S2CID 20829389.

- ^ a b Hemesath TJ, Steingrímsson E, McGill G, Hansen MJ, Vaught J, Hodgkinson CA, et al. (November 1994). "microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family". Genes & Development. 8 (22): 2770–80. doi:10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. PMID 7958932.

- ^ a b Ballesteros-Álvarez J, Dilshat R, Fock V, Möller K, Karl L, Larue L, et al. (3 September 2020). "MITF and TFEB cross-regulation in melanoma cells". PLOS ONE. 15 (9) e0238546. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1538546B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238546. PMC 7470386. PMID 32881934.

- ^ a b Pogenberg V, Ballesteros-Álvarez J, Schober R, Sigvaldadóttir I, Obarska-Kosinska A, Milewski M, et al. (January 2020). "Mechanism of conditional partner selectivity in MITF/TFE family transcription factors with a conserved coiled coil stammer motif". Nucleic Acids Research. 48 (2): 934–948. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz1104. PMC 6954422. PMID 31777941.

- ^ Hughes MJ, Lingrel JB, Krakowsky JM, Anderson KP (October 1993). "A helix-loop-helix transcription factor-like gene is located at the mi locus". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (28): 20687–90. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36830-9. PMID 8407885.

- ^ Cheli Y, Ohanna M, Ballotti R, Bertolotto C (February 2010). "Fifteen-year quest for microphthalmia-associated transcription factor target genes". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 23 (1): 27–40. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00653.x. PMID 19995375. S2CID 43471663.

- ^ Moore KJ (November 1995). "Insight into the microphthalmia gene". Trends in Genetics. 11 (11): 442–8. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(00)89143-x. PMID 8578601.

- ^ a b "MITF gene". Genetics Home Reference. National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

- ^ Lister JA, Robertson CP, Lepage T, Johnson SL, Raible DW (September 1999). "nacre encodes a zebrafish microphthalmia-related protein that regulates neural-crest-derived pigment cell fate". Development. 126 (17): 3757–67. doi:10.1242/dev.126.17.3757. PMID 10433906.

- ^ Delfgaauw J, Duschl J, Wellbrock C, Froschauer C, Schartl M, Altschmied J (November 2003). "MITF-M plays an essential role in transcriptional activation and signal transduction in Xiphophorus melanoma". Gene. 320: 117–26. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00817-5. PMID 14597395.

- ^ Ballotti R, Cheli Y, Bertolotto C (December 2020). "The complex relationship between MITF and the immune system: a Melanoma ImmunoTherapy (response) Factor?". Mol Cancer. 19 (1): 170. doi:10.1186/s12943-020-01290-7. PMC 7718690. PMID 33276788.

- ^ Kumar S, Rao K (May 2012). "Waardenburg syndrome: A rare genetic disorder, a report of two cases". Indian Journal of Human Genetics. 18 (2): 254–5. doi:10.4103/0971-6866.100804. PMC 3491306. PMID 23162308.

- ^ Smith SD, Kelley PM, Kenyon JB, Hoover D (June 2000). "Tietz syndrome (hypopigmentation/deafness) caused by mutation of MITF". Journal of Medical Genetics. 37 (6): 446–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.37.6.446. PMC 1734605. PMID 10851256.

- ^ "Melanoma Skin Cancer. " American Cancer Society, 29. Oct. 2014. Web. 15 October 2014. <http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003120-pdf.pdf>

- ^ Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM, Grob JJ, Simeone E, Grimaldi AM, Maio M, et al. (July 2012). "The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma". Journal of Translational Medicine. 10: 85. doi:10.1186/1479-5876-10-85. PMC 3391993. PMID 22554099.

- ^ Luchin A, Purdom G, Murphy K, Clark MY, Angel N, Cassady AI, et al. (March 2000). "The microphthalmia transcription factor regulates expression of the tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase gene during terminal differentiation of osteoclasts". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 15 (3): 451–60. doi:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.3.451. PMID 10750559. S2CID 24064612.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Hoek KS, Schlegel NC, Eichhoff OM, Widmer DS, Praetorius C, Einarsson SO, et al. (December 2008). "Novel MITF targets identified using a two-step DNA microarray strategy". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 21 (6): 665–76. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00505.x. PMID 19067971. S2CID 24698373.

- ^ McGill GG, Horstmann M, Widlund HR, Du J, Motyckova G, Nishimura EK, et al. (June 2002). "Bcl2 regulation by the melanocyte master regulator Mitf modulates lineage survival and melanoma cell viability". Cell. 109 (6): 707–18. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00762-6. PMID 12086670. S2CID 14863011.

- ^ Esumi N, Kachi S, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ (January 2007). "VMD2 promoter requires two proximal E-box sites for its activity in vivo and is regulated by the MITF-TFE family". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (3): 1838–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M609517200. PMID 17085443.

- ^ Dynek JN, Chan SM, Liu J, Zha J, Fairbrother WJ, Vucic D (May 2008). "Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor is a critical transcriptional regulator of melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis in melanomas". Cancer Research. 68 (9): 3124–32. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6622. PMID 18451137.

- ^ Du J, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, Ramaswamy S, Ross K, Huber WE, et al. (December 2004). "Critical role of CDK2 for melanoma growth linked to its melanocyte-specific transcriptional regulation by MITF". Cancer Cell. 6 (6): 565–76. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.014. PMID 15607961.

- ^ a b Meadows NA, Sharma SM, Faulkner GJ, Ostrowski MC, Hume DA, Cassady AI (January 2007). "The expression of Clcn7 and Ostm1 in osteoclasts is coregulated by microphthalmia transcription factor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (3): 1891–904. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608572200. PMID 17105730.

- ^ a b Yasumoto K, Takeda K, Saito H, Watanabe K, Takahashi K, Shibahara S (June 2002). "Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor interacts with LEF-1, a mediator of Wnt signaling". The EMBO Journal. 21 (11): 2703–14. doi:10.1093/emboj/21.11.2703. PMC 126018. PMID 12032083.

- ^ Sato-Jin K, Nishimura EK, Akasaka E, Huber W, Nakano H, Miller A, et al. (April 2008). "Epistatic connections between microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and endothelin signaling in Waardenburg syndrome and other pigmentary disorders". FASEB Journal. 22 (4): 1155–68. doi:10.1096/fj.07-9080com. PMID 18039926. S2CID 14304386.

- ^ Loftus SK, Antonellis A, Matera I, Renaud G, Baxter LL, Reid D, et al. (February 2009). "Gpnmb is a melanoblast-expressed, MITF-dependent gene". Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 22 (1): 99–110. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2008.00518.x. PMC 2714741. PMID 18983539.

- ^ Vetrini F, Auricchio A, Du J, Angeletti B, Fisher DE, Ballabio A, Marigo V (August 2004). "The microphthalmia transcription factor (Mitf) controls expression of the ocular albinism type 1 gene: link between melanin synthesis and melanosome biogenesis". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (15): 6550–9. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.15.6550-6559.2004. PMC 444869. PMID 15254223.

- ^ Aoki H, Moro O (September 2002). "Involvement of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) in expression of human melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1R)". Life Sciences. 71 (18): 2171–9. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(02)01996-3. PMID 12204775.

- ^ a b Du J, Miller AJ, Widlund HR, Horstmann MA, Ramaswamy S, Fisher DE (July 2003). "MLANA/MART1 and SILV/PMEL17/GP100 are transcriptionally regulated by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma". The American Journal of Pathology. 163 (1): 333–43. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63657-7. PMC 1868174. PMID 12819038.

- ^ Chiaverini C, Beuret L, Flori E, Busca R, Abbe P, Bille K, et al. (May 2008). "Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor regulates RAB27A gene expression and controls melanosome transport". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (18): 12635–42. doi:10.1074/jbc.M800130200. PMID 18281284.

- ^ Du J, Fisher DE (January 2002). "Identification of Aim-1 as the underwhite mouse mutant and its transcriptional regulation by MITF". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (1): 402–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110229200. PMID 11700328.

- ^ Carreira S, Liu B, Goding CR (July 2000). "The gene encoding the T-box factor Tbx2 is a target for the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in melanocytes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (29): 21920–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M000035200. PMID 10770922.

- ^ Miller AJ, Du J, Rowan S, Hershey CL, Widlund HR, Fisher DE (January 2004). "Transcriptional regulation of the melanoma prognostic marker melastatin (TRPM1) by MITF in melanocytes and melanoma". Cancer Research. 64 (2): 509–16. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2440. PMID 14744763.

- ^ Hou L, Panthier JJ, Arnheiter H (December 2000). "Signaling and transcriptional regulation in the neural crest-derived melanocyte lineage: interactions between KIT and MITF". Development. 127 (24): 5379–89. doi:10.1242/dev.127.24.5379. PMID 11076759.

- ^ Fang D, Tsuji Y, Setaluri V (July 2002). "Selective down-regulation of tyrosinase family gene TYRP1 by inhibition of the activity of melanocyte transcription factor, MITF". Nucleic Acids Research. 30 (14): 3096–106. doi:10.1093/nar/gkf424. PMC 135745. PMID 12136092.

- ^ Han JM, Lee MJ, Park SG, Lee SH, Razin E, Choi EC, Kim S (December 2006). "Hierarchical network between the components of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex: implications for complex formation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (50): 38663–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M605211200. PMID 17062567.

- ^ Yannay-Cohen N, Carmi-Levy I, Kay G, Yang CM, Han JM, Kemeny DM, et al. (June 2009). "LysRS serves as a key signaling molecule in the immune response by regulating gene expression". Molecular Cell. 34 (5): 603–11. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.019. PMID 19524539.

- ^ Lee YN, Nechushtan H, Figov N, Razin E (February 2004). "The function of lysyl-tRNA synthetase and Ap4A as signaling regulators of MITF activity in FcepsilonRI-activated mast cells". Immunity. 20 (2): 145–51. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(04)00020-2. PMID 14975237.

- ^ Yu J, Liu Z, Liang Y, Luo F, Zhang J, Tian C, et al. (October 2019). "4A polymerizes target protein HINT1 to transduce signals in FcεRI-activated mast cells". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 4664. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-12710-8. PMC 6789022. PMID 31604935.

- ^ Gray-Schopfer V, Wellbrock C, Marais R (February 2007). "Melanoma biology and new targeted therapy". Nature. 445 (7130): 851–7. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..851G. doi:10.1038/nature05661. PMID 17314971. S2CID 4421616.

- ^ Motzik A, Amir E, Erlich T, Wang J, Kim BG, Han JM, et al. (August 2017). "Post-translational modification of HINT1 mediates activation of MITF transcriptional activity in human melanoma cells". Oncogene. 36 (33): 4732–4738. doi:10.1038/onc.2017.81. PMID 28394346. S2CID 6790116.

- ^ Zimoń M, Baets J, Almeida-Souza L, De Vriendt E, Nikodinovic J, Parman Y, et al. (October 2012). "Loss-of-function mutations in HINT1 cause axonal neuropathy with neuromyotonia". Nature Genetics. 44 (10): 1080–3. doi:10.1038/ng.2406. PMID 22961002. S2CID 205345993.

- ^ Carmi-Levy I, Yannay-Cohen N, Kay G, Razin E, Nechushtan H (September 2008). "Diadenosine tetraphosphate hydrolase is part of the transcriptional regulation network in immunologically activated mast cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 28 (18): 5777–84. doi:10.1128/MCB.00106-08. PMC 2546939. PMID 18644867.

- ^ Oka K, Suzuki T, Onodera Y, Miki Y, Takagi K, Nagasaki S, et al. (April 2011). "Nudix-type motif 2 in human breast carcinoma: a potent prognostic factor associated with cell proliferation". International Journal of Cancer. 128 (8): 1770–82. doi:10.1002/ijc.25505. PMID 20533549. S2CID 26481581.

- ^ Carmi-Levy I, Motzik A, Ofir-Birin Y, Yagil Z, Yang CM, Kemeny DM, et al. (May 2011). "Importin beta plays an essential role in the regulation of the LysRS-Ap(4)A pathway in immunologically activated mast cells". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 31 (10): 2111–21. doi:10.1128/MCB.01159-10. PMC 3133347. PMID 21402779.

- ^ Tshori S, Gilon D, Beeri R, Nechushtan H, Kaluzhny D, Pikarsky E, Razin E (October 2006). "Transcription factor MITF regulates cardiac growth and hypertrophy". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 116 (10): 2673–81. doi:10.1172/JCI27643. PMC 1570375. PMID 16998588.

- ^ Hemesath TJ, Price ER, Takemoto C, Badalian T, Fisher DE (January 1998). "MAP kinase links the transcription factor Microphthalmia to c-Kit signalling in melanocytes". Nature. 391 (6664): 298–301. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..298H. doi:10.1038/34681. PMID 9440696. S2CID 26589863.

- ^ Wu M, Hemesath TJ, Takemoto CM, Horstmann MA, Wells AG, Price ER, et al. (February 2000). "c-Kit triggers dual phosphorylations, which couple activation and degradation of the essential melanocyte factor Mi". Genes & Development. 14 (3): 301–12. doi:10.1101/gad.14.3.301. PMC 316361. PMID 10673502.

- ^ a b c Phung B, Kazi JU, Lundby A, Bergsteinsdottir K, Sun J, Goding CR, et al. (September 2017). "D816V Induces SRC-Mediated Tyrosine Phosphorylation of MITF and Altered Transcription Program in Melanoma". Molecular Cancer Research. 15 (9): 1265–1274. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-17-0149. PMID 28584020.

- ^ Phung B, Sun J, Schepsky A, Steingrimsson E, Rönnstrand L (24 August 2011). Capogrossi MC (ed.). "C-KIT signaling depends on microphthalmia-associated transcription factor for effects on cell proliferation". PLOS ONE. 6 (8) e24064. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...624064P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0024064. PMC 3161112. PMID 21887372.

- ^ Ngeow KC, Friedrichsen HJ, Li L, Zeng Z, Andrews S, Volpon L, et al. (September 2018). "BRAF/MAPK and GSK3 signaling converges to control MITF nuclear export". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (37): E8668 – E8677. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E8668N. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810498115. PMC 6140509. PMID 30150413.

- ^ Morii E, Oboki K, Kataoka TR, Igarashi K, Kitamura Y (March 2002). "Interaction and cooperation of mi transcription factor (MITF) and myc-associated zinc-finger protein-related factor (MAZR) for transcription of mouse mast cell protease 6 gene". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (10): 8566–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110392200. PMID 11751862.

- ^ Levy C, Nechushtan H, Razin E (January 2002). "A new role for the STAT3 inhibitor, PIAS3: a repressor of microphthalmia transcription factor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (3): 1962–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109236200. PMID 11709556.

- ^ Steingrimsson E, Tessarollo L, Pathak B, Hou L, Arnheiter H, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA (April 2002). "Mitf and Tfe3, two members of the Mitf-Tfe family of bHLH-Zip transcription factors, have important but functionally redundant roles in osteoclast development". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (7): 4477–82. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.4477S. doi:10.1073/pnas.072071099. PMC 123673. PMID 11930005.

- ^ Mansky KC, Sulzbacher S, Purdom G, Nelsen L, Hume DA, Rehli M, Ostrowski MC (February 2002). "The microphthalmia transcription factor and the related helix-loop-helix zipper factors TFE-3 and TFE-C collaborate to activate the tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase promoter". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 71 (2): 304–10. doi:10.1189/jlb.71.2.304. PMID 11818452. S2CID 22801820.

- ^ Sardiello M, Palmieri M, di Ronza A, Medina DL, Valenza M, Gennarino VA, et al. (July 2009). "A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function". Science. 325 (5939): 473–7. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..473S. doi:10.1126/science.1174447. PMID 19556463. S2CID 20353685.

- ^ Palmieri M, Impey S, Kang H, di Ronza A, Pelz C, Sardiello M, Ballabio A (October 2011). "Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways". Human Molecular Genetics. 20 (19): 3852–66. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr306. PMID 21752829.

- ^ Möller K, Sigurbjornsdottir S, Arnthorsson AO, Pogenberg V, Dilshat R, Fock V, et al. (January 2019). "MITF has a central role in regulating starvation-induced autophagy in melanoma". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 1055. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.1055M. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37522-6. PMC 6355916. PMID 30705290.

- ^ Xu W, Gong L, Haddad MM, Bischof O, Campisi J, Yeh ET, Medrano EE (March 2000). "Regulation of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor MITF protein levels by association with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme hUBC9". Experimental Cell Research. 255 (2): 135–43. doi:10.1006/excr.2000.4803. PMID 10694430.

- ^ Razin E, Zhang ZC, Nechushtan H, Frenkel S, Lee YN, Arudchandran R, Rivera J (November 1999). "Suppression of microphthalmia transcriptional activity by its association with protein kinase C-interacting protein 1 in mast cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 274 (48): 34272–6. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.48.34272. PMID 10567402.

- ^ a b Falletta P, Sanchez-Del-Campo L, Chauhan J, Effern M, Kenyon A, Kershaw CJ, et al. (January 2017). "Translation reprogramming is an evolutionarily conserved driver of phenotypic plasticity and therapeutic resistance in melanoma". Genes & Development. 31 (1): 18–33. doi:10.1101/gad.290940.116. PMC 5287109. PMID 28096186.

- ^ a b c Phung B, Cieśla M, Sanna A, Guzzi N, Beneventi G, Cao Thi Ngoc P, et al. (June 2019). "The X-Linked DDX3X RNA Helicase Dictates Translation Reprogramming and Metastasis in Melanoma". Cell Reports. 27 (12): 3573–3586.e7. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.069. PMID 31216476.

External links

[edit]- Microphthalmia-associated+transcription+factor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)