Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Medieval Latin

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2013) |

| Medieval Latin | |

|---|---|

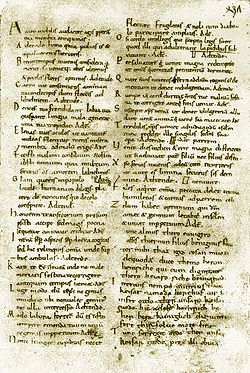

Carmina Cantabrigiensia, Medieval Latin manuscript | |

| Native to | Numerous small states |

| Region | Latin Christianity (Most of Europe. Also among Mozarabs and Roman Africans) |

| Era | Developed from Late Latin between 4th and 10th centuries; replaced by Renaissance Latin from the 14th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | De facto in most Catholic and/or Romance-speaking states during the Middle Ages[a] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

lat-med | |

| Glottolog | medi1250 |

Europe, AD 1000 | |

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidia and Africa Proconsularis under the Vandals, the Byzantines and the Romano-Berber Kingdoms, until it declined after the Arab Conquest. Medieval Latin in Southern and Central Visigothic Hispania, conquered by the Arabs immediately after North Africa, experienced a similar fate, only recovering its importance after the Reconquista by the Northern Christian Kingdoms. In this region, it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned as the main medium of scholarly exchange, as the liturgical language of the Church, and as the working language of science, literature, law, and administration.

Medieval Latin represented a continuation of Classical Latin and Late Latin, with enhancements for new concepts as well as for the increasing integration of Christianity. Despite some meaningful differences from Classical Latin, its writers did not regard it as a fundamentally different language. There is no real consensus on the exact boundary where Late Latin ends and Medieval Latin begins. Some scholarly surveys begin with the rise of early Ecclesiastical Latin in the middle of the 4th century, others around 500,[1] and still others with the replacement of written Late Latin by written Romance languages starting around the year 900.

The terms Medieval Latin and Ecclesiastical Latin are sometimes used synonymously, though some scholars draw distinctions. Ecclesiastical Latin refers specifically to the form that has been used by the Roman Catholic Church (even before the Middle Ages in Antiquity), whereas Medieval Latin refers to all of the (written) forms of Latin used in the Middle Ages. The Romance languages spoken in the Middle Ages were often referred to as Latin, since the Romance languages were all descended from Vulgar Latin itself.[2] Medieval Latin would be replaced by educated humanist Renaissance Latin, otherwise known as Neo-Latin.

Influences

[edit]Christian Latin

[edit]Medieval Latin had an enlarged vocabulary, which freely borrowed from other sources. It was heavily influenced by the language of the Vulgate, which contained many peculiarities alien to Classical Latin that resulted from a more or less direct translation from Greek and Hebrew; the peculiarities mirrored the original not only in its vocabulary but also in its grammar and syntax. Greek provided much of the technical vocabulary of Christianity. The various Germanic languages spoken by the Germanic tribes, who invaded southern Europe, were also major sources of new words. Germanic leaders became the rulers of parts of the Roman Empire that they conquered, and words from their languages were freely imported into the vocabulary of law. Other more ordinary words were replaced by coinages from Vulgar Latin or Germanic sources because the classical words had fallen into disuse.

Latin was also spread to areas such as Ireland and Germany, where Romance languages were not spoken, and which had never known Roman rule. Works written in those lands where Latin was a learned language, having no relation to the local vernacular, also influenced the vocabulary and syntax of Medieval Latin.

Since subjects like science and philosophy, including Rhetoric and Ethics, were communicated in Latin, the Latin vocabulary that developed for them became the source of a great many technical words in modern languages. English words like abstract, subject, communicate, matter, probable and their cognates in other European languages generally have the meanings given to them in Medieval Latin, often terms for abstract concepts not available in English.[3]

Vulgar Latin

[edit]The influence of Vulgar Latin was also apparent in the syntax of some Medieval Latin writers, although Classical Latin continued to be held in high esteem and studied as models for literary compositions. The high point of the development of Medieval Latin as a literary language came with the Carolingian Renaissance, a rebirth of learning kindled under the patronage of Charlemagne, king of the Franks. Alcuin was Charlemagne's Latin secretary and an important writer in his own right; his influence led to a rebirth of Latin literature and learning after the depressed period following the final disintegration of the authority of the Western Roman Empire.

Although it was simultaneously developing into the Romance languages, Latin itself remained very conservative, as it was no longer a native language and there were many ancient and medieval grammar books to give one standard form. On the other hand, strictly speaking there was no single form of "Medieval Latin". Every Latin author in the medieval period spoke Latin as a second language, with varying degrees of fluency and syntax. Grammar and vocabulary, however, were often influenced by an author's native language. This was especially true beginning around the 12th century, after which the language became increasingly adulterated: late Medieval Latin documents written by French speakers tend to show similarities to medieval French grammar and vocabulary; those written by Germans tend to show similarities to German, etc. For instance, rather than following the classical Latin practice of generally placing the verb at the end, medieval writers would often follow the conventions of their own native language instead. Whereas Latin had no definite or indefinite articles, medieval writers sometimes used forms of unus as an indefinite article, and forms of ille (reflecting usage in the Romance languages) as a definite article or even quidam (meaning "a certain one/thing" in Classical Latin) as something like an article. Unlike classical Latin, where esse ("to be") was the only auxiliary verb, Medieval Latin writers might use habere ("to have") as an auxiliary, similar to constructions in Germanic and Romance languages. The accusative and infinitive construction in classical Latin was often replaced by a subordinate clause introduced by quod or quia. This is almost identical, for example, to the use of que in similar constructions in French. Many of these developments are similar to Standard Average European and the use of medieval Latin among the learned elites of Christendom may have played a role in the spread of those features.

In every age from the late 8th century onwards, there were learned writers (especially within the Church) who were familiar enough with classical syntax to be aware that these forms and usages were "wrong" and resisted their use. Thus the Latin of a theologian like St Thomas Aquinas or of an erudite clerical historian such as William of Tyre tends to avoid most of the characteristics described above, showing its period in vocabulary and spelling alone; the features listed are much more prominent in the language of lawyers (e.g. the 11th-century English Domesday Book), physicians, technical writers and secular chroniclers. However the use of quod to introduce subordinate clauses was especially pervasive and is found at all levels.[4]

Changes in vocabulary, syntax, and grammar

[edit]Medieval Latin had ceased to be a living language and was instead a scholarly language of the minority of educated men (and a tiny number of women) in medieval Europe, used in official documents more than for everyday communication. This resulted in two major features of Medieval Latin compared with Classical Latin, though when it is compared to the other vernacular languages, Medieval Latin developed very few changes.[4] There are many prose constructions written by authors of this period that can be considered "showing off" a knowledge of Classical or Old Latin by the use of rare or archaic forms and sequences. Though they had not existed together historically, it is common that an author would use grammatical ideas of the two periods Republican and archaic, placing them equally in the same sentence. Also, many undistinguished scholars had limited education in "proper" Latin, or had been influenced in their writings by Vulgar Latin.

- Word order usually tended towards that of the vernacular language of the author, not the word order of Classical Latin. Conversely, an erudite scholar might attempt to "show off" by intentionally constructing a very complicated sentence. Because Latin is an inflected language, it is technically possible to place related words at opposite ends of a paragraph-long sentence, and owing to the complexity of doing so, it was seen by some as a sign of great skill. The preferred word order in Latin is Subject-Object-Verb; most vernaculars of medieval Latin authors tend to or mandate Subject-Verb-Object which thus is more prevalent in medieval than in classical Latin.

- Typically, prepositions are used much more frequently (as in modern Romance languages) for greater clarity, instead of using the ablative case alone. Furthermore, in Classical Latin the subject of a verb was often left implied, unless it was being stressed: videt = "he sees". For clarity, Medieval Latin more frequently includes an explicit subject: is videt = "he sees" without necessarily stressing the subject. Classical Latin is a pro-drop language whereas most Germanic (including standard English) and some Romance languages are not.

- Various changes occurred in vocabulary, and certain words were mixed into different declensions or conjugations. Many new compound verbs were formed. Some words retained their original structure but drastically changed in meaning: animositas specifically means "wrath" in Medieval Latin while in Classical Latin, it generally referred to "high spirits, excited spirits" of any kind.

- Owing to heavy use of biblical terms, there was a large influx of new words borrowed from Greek and Hebrew and even some grammatical influences. That obviously largely occurred among priests and scholars, not the laity. In general, it is difficult to express abstract concepts in Latin, as many scholars admitted. For example, Plato's abstract concept of "the Truth" had to be expressed in Latin as "what is always true". Medieval scholars and theologians, translating both the Bible and Greek philosophers into Latin out of the Koine and Classical Greek, cobbled together many new abstract concept words in Latin.

Syntax

[edit]- Indirect discourse, which in Classical Latin was achieved by using a subject accusative and infinitive, was now often simply replaced by new conjunctions serving the function of English "that" such as quod, quia, or quoniam. There was a high level of overlap between the old and new constructions, even within the same author's work, and it was often a matter of preference. A particularly famous and often cited example is from the Venerable Bede, using both constructions within the same sentence: "Dico me scire et quod sum ignobilis" = "I say that I know [accusative and infinitive] and that I am unknown [new construction]". The resulting subordinate clause often used the subjunctive mood instead of the indicative. This new syntax for indirect discourse is among the most prominent features of Medieval Latin, the largest syntactical change. However, such use of quod or quia also occurred in the Latin of the late Roman Empire,[5] e.g. the Vulgate's Matthew 2:22: "Audiens autem quod Archelaus regnaret in Judaea pro Herode..." = "But hearing that Archelaus reigned in Judaea in Herod's place..."

- Several substitutions were often used instead of subjunctive clause constructions. They did not break the rules of Classical Latin but were an alternative way to express the same meaning, avoiding the use of a subjunctive clause.

- The present participle was frequently used adverbially in place of qui or cum clauses, such as clauses of time, cause, concession, and purpose. That was loosely similar to the use of the present participle in an ablative absolute phrase, but the participle did not need to be in the ablative case.

- Habeo (I have [to]) and Debeo (I must) would be used to express obligation more often than the gerundive.

- Given that obligation inherently carries a sense of futurity ("Carthage must be destroyed" at some point in the future), this parallels the Romance languages' use of habeo as the basis of their future tenses (abandoning the Latin forms of the future tense). While in Latin amare habeo is the indirect discourse "I have to love", in the French equivalent, aimerai (habeo > ayyo > ai, aimer+ai), it has become the future tense, "I shall love", losing the sense of obligation. In Medieval Latin, however, it was only indirect discourse and not used as simply a future tense.

- Instead of a clause introduced by ut or ne, an infinitive was often used with a verb of hoping, fearing, promising, etc.

- Conversely, some authors might haphazardly switch between the subjunctive and indicative forms of verbs, with no intended difference in meaning.

- The usage of sum changed significantly: it was frequently omitted or implied. Further, many medieval authors did not feel that it made sense for the perfect passive construction "laudatus sum" to use the present tense of esse in a past tense construction so they began using fui, the past perfect of sum, interchangeably with sum.

- Chaos in the usage of demonstrative pronouns. Hic, ille, iste, and even the intensive ipse are often used virtually interchangeably. As in the Romance languages, hic and ille were also frequently used simply to express the definite article "the", which Classical Latin did not possess. Unus was also used for the indefinite article "a, an".

- Use of reflexives became much looser. A reflexive pronoun in a subordinate clause might refer to the subject of the main clause. The reflexive possessive suus might be used in place of a possessive genitive such as eius.

- Comparison of adjectives changed somewhat. The comparative form was sometimes used with positive or superlative meaning. Also, the adverb magis was often used with a positive adjective to indicate a comparative meaning, and multum and nimis could be used with a positive form of adjective to give a superlative meaning.

- Classical Latin used the ablative absolute, but as stated above, in Medieval Latin examples of nominative absolute or accusative absolute may be found. This was a point of difference between the ecclesiastical Latin of the clergy and the "Vulgar Latin" of the laity, which existed alongside it. The educated clergy mostly knew that traditional Latin did not use the nominative or accusative case in such constructions, but only the ablative case. These constructions are observed in the medieval era, but they are changes that developed among the uneducated commoners.

- Classical Latin does not distinguish progressive action in the present tense, thus laudo can mean either "I praise" or "I am praising". In imitation of Greek, Medieval Latin could use a present participle with sum to form a periphrastic tense equivalent to the English progressive. This "Greek Periphrastic Tense" formation could also be done in the past and future tenses: laudans sum ("I am praising"), laudans eram ("I was praising"), laudans ero ("I shall be praising").

- Classical Latin verbs had at most two voices, active and passive, but Greek (the original language of the New Testament) had an additional "middle voice" (or reflexive voice). One use was to express when the subject is acting upon itself: "Achilles put the armor onto himself" or "Jesus clothed himself in the robe" would use the middle voice. Because Latin had no middle voice, Medieval Latin expresses such sentences by putting the verb in the passive voice form, but the conceptual meaning is active (similar to Latin deponent verbs). For example, the Medieval Latin translation of Genesis states literally, "the Spirit of God was moved over the waters" (spiritus Dei ferebatur super aquas, Genesis 1:2), but it is just expressing a Greek middle-voice verb: "God moved [himself] over the waters".

- Overlapping with orthography differences (see below), certain diphthongs were sometimes shortened: "oe" to "e", and "ae" to "e". Thus, oecumenicus becomes the more familiar ecumenicus (more familiar in this later form because religious terms such as "ecumenical" were more common in Medieval Latin). The "oe" diphthong is not particularly frequent in Latin, but the shift from "ae" to "e" affects many common words, such as caelum (heaven) being shortened to celum; even puellae (girls) was shortened to puelle.

- Often, a town would lose its name to that of the tribe which was either accusative or ablative plural; two forms that were then used for all cases, or in other words, considered "indeclinable".[6][clarification needed]

Orthography

[edit]

Many striking differences between classical and Medieval Latin are found in orthography. Perhaps the most striking difference is that medieval manuscripts used a wide range of abbreviations by means of superscripts, special characters etc.: for instance the letters "n" and "s" were often omitted and replaced by a diacritical mark above the preceding or following letter. Apart from this, some of the most frequently occurring differences are as follows. Clearly many of these would have been influenced by the spelling, and indeed pronunciation,[6] of the vernacular language, and thus varied between different European countries.

- Following the Carolingian reforms of the 9th century, Carolingian minuscule was widely adopted, leading to a clear differentiation between capital and lowercase letters.

- A partial or full differentiation between v and u, and between j and i.

- The diphthong ae is usually collapsed and simply written as e (or e caudata, ę); for example, puellae might be written puelle (or puellę). The same happens with the diphthong oe, for example in pena, Edipus, from poena, Oedipus. This feature is already found on coin inscriptions of the 4th century (e.g. reipublice for reipublicae). Conversely, an original e in Classical Latin was often represented by ae or oe (e.g. aecclesia and coena), also reflected in English spellings such as foetus.

- Because of a severe decline in the knowledge of Greek, in loanwords and foreign names from or transmitted through Greek, y and i might be used more or less interchangeably: Ysidorus, Egiptus, from Isidorus, Aegyptus. This is also found in pure Latin words: ocius ("more swiftly") appears as ocyus and silva as sylva, this last being a form which survived into the 18th century and so became embedded in modern botanical Latin (also cf. Pennsylvania).

- h might be lost, so that habere becomes abere, or mihi becomes mi (the latter also occurred in Classical Latin); or mihi may be written michi, indicating that the h had come to be pronounced as [k] or perhaps [x]. This pronunciation is not found in Classical Latin, but had existed very early in vulgar speech.

- The loss of h in pronunciation also led to the addition of h in writing where it did not previously belong, especially in the vicinity of r, such as chorona for corona, a tendency also sometimes seen in Classical Latin.

- -ti- before a vowel is often written as -ci- [tsi], so that divitiae becomes diviciae (or divicie), tertius becomes tercius, vitium vicium.

- The combination mn might have another plosive inserted, so that alumnus becomes alumpnus, somnus sompnus.

- Single consonants were often doubled, or vice versa, so that tranquillitas becomes tranquilitas and Africa becomes Affrica.

- Syncopation became more frequent: vi, especially in verbs in the perfect tense, might be lost, so that novisse becomes nosse (this occurred in Classical Latin as well but was much more frequent in Medieval Latin).

These orthographical differences were often due to changes in pronunciation or, as in the previous example, morphology, which authors reflected in their writing. By the 16th century, Erasmus complained that speakers from different countries were unable to understand each other's form of Latin.[7]

The gradual changes in Latin did not escape the notice of contemporaries. Petrarch, writing in the 14th century, complained about this linguistic "decline", which helped fuel his general dissatisfaction with his own era.

Medieval Latin literature

[edit]The corpus of Medieval Latin literature encompasses a wide range of texts, including such diverse works as sermons, hymns, hagiographical texts, travel literature, histories, epics, and lyric poetry.

The first half of the 5th century saw the literary activities of the great Christian authors Jerome (c. 347–420) and Augustine of Hippo (354–430), whose texts had an enormous influence on theological thought of the Middle Ages, and of the latter's disciple Prosper of Aquitaine (c. 390 – c. 455). Of the later 5th century and early 6th century, Sidonius Apollinaris (c. 430 – after 489) and Ennodius (474–521), both from Gaul, are well known for their poems, as is Venantius Fortunatus (c. 530 – c. 600). This was also a period of transmission: the Roman patrician Boethius (c. 480–524) translated part of Aristotle's logical corpus, thus preserving it for the Latin West, and wrote the influential literary and philosophical treatise De consolatione Philosophiae; Cassiodorus (c. 485 – c. 585) founded an important library at the monastery of Vivarium near Squillace where many texts from Antiquity were to be preserved. Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) collected all scientific knowledge still available in his time into what might be called the first encyclopedia, the Etymologiae.

Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594) wrote a lengthy history of the Frankish kings. Gregory came from a Gallo-Roman aristocratic family, and his Latin, which shows many aberrations from the classical forms, testifies to the declining significance of classical education in Gaul. At the same time, good knowledge of Latin and even of Greek was being preserved in monastic culture in Ireland and was brought to England and the European mainland by missionaries in the course of the 6th and 7th centuries, such as Columbanus (543–615), who founded the monastery of Bobbio in Northern Italy. Ireland was also the birthplace of a strange poetic style known as Hisperic Latin. Other important Insular authors include the historian Gildas (c. 500 – c. 570) and the poet Aldhelm (c. 640–709). Benedict Biscop (c. 628–690) founded the monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow and furnished it with books which he had taken home from a journey to Rome and which were later used by Bede (c. 672–735) to write his Ecclesiastical History of the English People.

Many Medieval Latin works have been published in the series Patrologia Latina, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum and Corpus Christianorum.

Medieval Latin and everyday life

[edit]Medieval Latin was separated from Classical Latin around 800 and at this time was no longer considered part of the everyday language. The speaking of Latin became a practice used mostly by the educated high class population. Even then it was not frequently used in casual conversation. An example of these men includes the churchmen who could read Latin, but could not effectively speak it. Latin's use in universities was structured in lectures and debates, however, it was highly recommended that students use it in conversation. This practice was kept up only due to rules.[8] One of Latin's purposes, writing, was still in practice; the main uses being charters for property transactions and to keep track of the pleadings given in court. Even then, those of the church still used Latin more than the rest of the population. At this time, Latin served little purpose to the regular population but was still used regularly in ecclesiastical culture.[8] Latin also served as a lingua franca among the educated elites of Christendom — long distance written communication, while rarer than in Antiquity, took place mostly in Latin. Most literate people wrote Latin and most rich people had access to scribes who knew Latin for use when the need for long distance correspondence arose. Long-distance communication in the vernacular was rare, but Hebrew, Arabic and Greek served a similar purpose among Jews, Muslims and Eastern Orthodox respectively.

Important Medieval Latin authors

[edit]6th–8th centuries

[edit]- Boëthius (c. 480 – 525)

- Cassiodorus (c. 485 – c. 585)

- Gildas (d. c. 570)

- Flavius Cresconius Corippus (d. c. 570)

- Venantius Fortunatus (c. 530 – c. 600)

- Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594)

- Pope Gregory I (c. 540 – 604)

- Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636)

- Bede (c. 672–735)

- St. Boniface (c. 672 – 754)

- Chrodegang of Metz (d. 766)

- Paul the Deacon (c. 720s – c. 799)

- Beatus of Liébana (c. 730 – c. 800)

- Peter of Pisa (d. 799)

- Paulinus of Aquileia (730s - 802)

- Alcuin (c. 735–804)

9th century

[edit]- Einhard (775–840)

- Rabanus Maurus (780–856)

- Paschasius Radbertus (790–865)

- Rudolf of Fulda (d. 865)

- Dhuoda

- Lupus of Ferrieres (805–862)

- Andreas Agnellus (Agnellus of Ravenna) (c. 805–846?)

- Hincmar (806–882)

- Walafrid Strabo (808–849)

- Florus of Lyon (d. 860?)

- Gottschalk (theologian) (808–867)

- Sedulius Scottus (fl. 840–860)

- Anastasius Bibliothecarius (810–878)

- Johannes Scotus Eriugena (815–877)

- Asser (d. 909)

- Notker Balbulus (840–912)

10th century

[edit]- Ratherius (890–974)

- Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim (935–973)

- Thietmar of Merseburg (975–1018)

11th century

[edit]- Marianus Scotus (1028–1082)

- Adam of Bremen (fl. 1060–1080)

- Anselm of Canterbury (1033/4–1109)

- Marbodius of Rennes (c. 1035–1123)

12th century

[edit]- Pierre Abélard (1079–1142)

- Suger of St Denis (c. 1081–1151)

- Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1100 – c. 1155)

- Ailred of Rievaulx (1110–1167)

- Otto of Freising (c. 1114–1158)

- Archpoet (c. 1130 – c. 1165)

- William of Tyre (c. 1130–1185)

- Peter of Blois (c. 1135 – c. 1203)

- Walter of Châtillon (fl. c. 1200)

- Adam of St. Victor

- Andreas Capellanus

13th century

[edit]- Giraldus Cambrensis (c. 1146 – c. 1223)

- Saxo Grammaticus (c. 1150 – c. 1220)

- Anonymus (notary of Béla III) (fl. late 12th century – early 13th century)

- Thomas of Celano (c. 1200 – c. 1265)

- Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280)

- Roger Bacon (c. 1214–1294)

- Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225–1274)

- Ramon Llull (1232–1315)

- Siger of Brabant (c. 1240–1280s)

- Duns Scotus (c. 1266–1308)

14th century

[edit]- Ranulf Higdon (c. 1280 – c. 1363)

- William of Ockham (c. 1288 – c. 1347)

- Jean Buridan (1300–1358)

- Henry Suso (c. 1295 – 1366)

- John Gower (c. 1330 – 1408)

Literary movements

[edit]Works

[edit]- Carmina Burana (11th–12th century)

- Pange Lingua (c. 1250)

- Summa Theologiae (c. 1270)

- Etymologiae (c. 600)

- Dies Irae (c. 1260)

- Decretum Gratiani (c. 1150)

- De Ortu Waluuanii Nepotis Arturi (c. 1180)

- Magna Carta (c. 1215)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Exceptions include the Romanian Lands of Moldavia and Wallachia

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ziolkowski, Jan M. (1996), "Towards a History of Medieval Latin Literature", in Mantello, F. A. C.; Rigg, A. G. (eds.), Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide, Washington, D.C., pp. 505–536 (pp. 510–511)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Romance languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ Franklin, James (1983). "Mental furniture from the philosophers" (PDF). Et Cetera. 40: 177–191. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b Mantello, F. A. C., Rigg, A. G. (1996). Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide. United States of America: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 85. ISBN 0813208416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Coleman, Robert G. (1999). "Latin language". In Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Anthony (eds.). Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 820.

Latin shares exclusively with Greek the development of the accusative + infinitive construction to render indirect speech. There were not enough infinitives or subjunctives to represent the distinctions required in principal and subordinate clauses respectively, and the whole inefficient construction gave way to clauses with quod, quia (perhaps modelled on Gk. hōs, hóti 'that'), to a larger extent in the later written language and totally in V[ulgar ]L[atin].

- ^ a b Beeson, Charles Henry (1986). A Primer of Medieval Latin: an anthology of prose and poetry. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 0813206359.

- ^ See Desiderius Erasmus, De recta Latini Graecique sermonis pronunciatione dialogus, Basel (Frobenius), 1528.

- ^ a b Mantello, F. A. C., Rigg, A. G. (1996). Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide. United States of America: The Catholic University of America Press. p. 315. ISBN 0813208416.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Sources

[edit]- K.P. Harrington, J. Pucci, and A.G. Elliott, Medieval Latin (2nd ed.), (Univ. Chicago Press, 1997) ISBN 0-226-31712-9

- F.A.C. Mantello and A.G. Rigg, eds., Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide (CUA Press, 1996) ISBN 0-8132-0842-4

- Dictionaries

- Du Cange et al., Glossarium ad scriptores mediæ et infimæ latinitatis, Niort : L. Favre, 1883–1887, Ecole des chartes.

- Thesaurus Linguae Latinae

Further reading

[edit]- Auerbach, Erich, 1965. Literary Language & Its Public: in Late Latin Antiquity and in the Middle Ages. New York, NY, USA, Bollingen Foundation.

- Bacci, Antonii. Varia Latinitatis Scripta II, Inscriptiones Orationes Epistvlae. Rome, Italy, Societas Librania Stvdivm.

- Beeson, Charles H., 1925. A Primer of Medieval Latin: An Anthology of Prose and Poetry. Chicago, United States, Scott, Foresman and Company.

- Chavannes-Mazel, Claudine A., and Margaret M. Smith, eds. 1996. Medieval Manuscripts of the Latin Classics: Production and Use; *Proceedings of the Seminar in the History of the Book to 1500, Leiden, 1993. Los Altos Hills, CA: Anderson-Lovelace.

- Curtius, Ernst Roberts, 1953. European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages. New York, New York, United States, Bollingen Foundation Inc.

- Dronke, Peter, vol. 1, 1965. Medieval Latin and the Rise of European Love-Lyric. Oxford, UK, Clarendon Press.

- Harrington, Karl Pomeroy, 1942. Mediaeval Latin. Norwood, MA, USA, Norwood Press.

- Hexter, Ralph J., and Townsend, David eds. second edition 2012: The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Latin Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lapidge, Michael. 1993. Anglo-Latin Literature 900–1066. London and Rio Grande, OH: Hambledon.

- --. 1996. Anglo-Latin Literature 600–899. London and Rio Grande, OH: Hambledon.

- Mann, Nicholas, and Birger Munk Olsen, eds. 1997. Medieval and Renaissance Scholarship: Proceedings of the Second European Science Foundation Workshop on the Classical Tradition in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, London: Warburg Institute, 27–28 November 1992. New York: Brill.

- Mantello, F. A. C., and George Rigg. 1996. Medieval Latin: An Introduction and Bibliographical Guide. Washington, DC: Catholic University of American Press.

- Pecere, Oronzo, and Michael D. Reeve. 1995. Formative Stages of Classical Traditions: Latin Texts from Antiquity to the Renaissance; Proceedings of a Conference Held at Erice, 16–22 October 1993, as the 6th Course of International School for the Study of Written Records. Spoleto, Italy: Centro Italiano di Studi sull’alto Medioevo.

- Raby, F. J. E. 1957. A History of Secular Latin Poetry in the Middle Ages. 2 vols. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Raby, F.J.E., 1959. The Oxford Book of Medieval Latin Verse. Amen House, London, Oxford University Press.

- Rigg, A. G. 1992. A History of Anglo-Latin Literature A.D. 1066–1422. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Stella, Francesco, Doležalová Lucie, and Shanzer, Danuta eds. 2024: Latin Literatures of Medieval and Early Modern times in Europe and Beyond, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Walde, Christine, ed. 2012. Brill's New Pauly Supplement 5: The Reception of Classical Literature. Leiden, The Netherlands, and Boston: Brill.

- Ziolkowski, Jan M., 1993. Talking Animals: Medieval Latin Beast Poetry, 750–1150. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

External links

[edit]- In-depth Guides to Learning Latin at the UK National Archives.

- The Journal of Medieval Latin

- Wright, Thomas, ed. A Selection of Latin Stories, from Manuscripts of the Thirteenth and Founteenth Centuries: A Contribution to the History of Fiction During the Middle Ages. (London: The Percy Society. 1842.)

- Corpus Corporum (mlat.uzh.ch)

- Corpus Thomisticum (corpusthomisticum.org)

- LacusCurtius (penelope.uchicago.edu)