Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Thermae

View on Wikipedia

In ancient Rome, thermae (from Greek θερμός thermos, "hot") and balneae (from Greek βαλανεῖον balaneion) were facilities for bathing. Thermae usually refers to the large imperial bath complexes, while balneae were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed in great numbers throughout Rome.[1]

Most Roman cities had at least one – if not many – such buildings, which were centers not only for bathing, but socializing and reading as well. Bathhouses were also provided for wealthy private villas, town houses, and forts.[2] They were supplied with water from an adjacent river or stream, or within cities by aqueduct. The water would be heated by fire then channelled into the caldarium (hot bathing room). The design of baths is discussed by Vitruvius in De architectura (V.10).

Terminology

[edit]

Thermae, balneae, balineae, balneum and balineum may all be translated as 'bath' or 'baths', though Latin sources distinguish among these terms.

Balneum or balineum, derived from the Greek βαλανεῖον[5][6] signifies, in its primary sense, a bath or bathing-vessel, such as most persons of any consequence among the Romans possessed in their own houses,[7] and hence the chamber which contained the bath,[8] which is also the proper translation of the word balnearium. The diminutive balneolum is adopted by Seneca[9] to designate the bathroom of Scipio in the villa at Liternum, and is expressly used to characterize the modesty of republican manners as compared with the luxury of his own times. But when the baths of private individuals became more sumptuous and comprised many rooms, instead of the one small chamber described by Seneca, the plural balnea or balinea was adopted, which still, in correct language, had reference only to the baths of private persons. Thus, Cicero terms the baths at the villa of his brother Quintus[10] balnearia.

Balneae and balineae, which according to Varro[11] have no singular number, were the public baths, but this accuracy of diction is neglected by many of the subsequent writers, and particularly by the poets, amongst whom balnea is not uncommonly used in the plural number to signify the public baths, since the word balneae could not be introduced in a hexameter verse. Pliny also, in the same sentence, makes use of the neuter plural balnea for public, and of balneum for a private bath.[12]

Thermae (Greek: Θέρμαι, Thermai, 'hot springs, hot baths',[13] from the Greek adjective thermos, 'hot') meant properly warm springs, or baths of warm water; but came to be applied to those magnificent edifices which grew up under the empire, in place of the simple balneae of the republic, and which comprised within their range of buildings all the appurtenances belonging to the Greek gymnasia, as well as a regular establishment appropriated for bathing.[14] Writers, however, use these terms without distinction. Thus the baths erected by Claudius Etruscus, the freedman of the Emperor Claudius, are styled by Statius[15] balnea, and by Martial[16] Etrusci thermulae. In an epigram by Martial[17]—subice balneum thermis—the terms are not applied to the whole building, but to two different chambers in the same edifice.

Building layout

[edit]

A public bath was built around three principal rooms: the tepidarium (warm room), the caldarium (hot room), and the frigidarium (cold room). Some thermae also featured steam baths: the sudatorium, a moist steam bath, and the laconicum, a dry hot room.[citation needed][dubious – discuss]

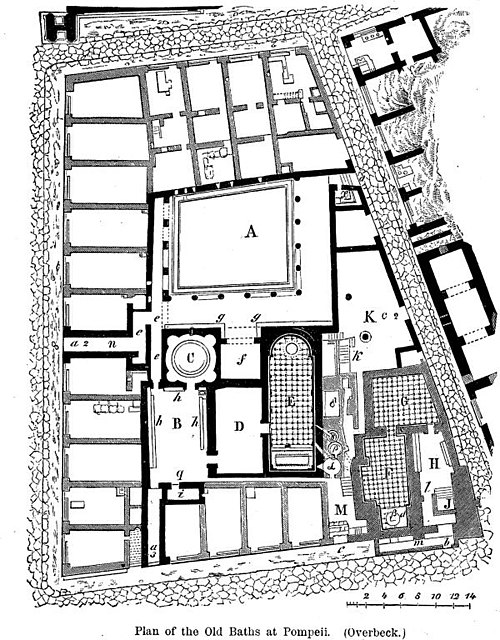

By way of illustration, this article will describe the layout of Pompeii's Old Baths, otherwise known as the Forum Baths, which are among the best-preserved Roman baths. These baths were connected to the forum at Pompeii, hence the name. The references are to the floor plan pictured to the right.[18]

This specific complex consists of a double set of baths, one for men and one for women. It has six different entrances from the street, one of which (b) gives admission to the smaller women's set only. Five other entrances lead to the men's department, of which two (c and c2), communicate directly with the furnaces, and the other three (a3, a2, a) with the bathing apartments.

Palaestra

[edit]Passing through the principal entrance, a (barely visible, right side, one third of the total length from above), which is removed from the street by a narrow footway surrounding the building and after descending three steps, the bather would find a small chamber on his left (x) with a toilet (latrina), and proceed into a covered portico (g, g), which ran round three sides of an open court (palaestra,[clarification needed] A). These together formed the vestibule of the baths (vestibulum balnearum),[19] in which the servants waited.

Use of the palaestra

[edit]This palaestra was the exercise ground for the young men, or perhaps served as a promenade for visitors to the baths. Within this court the keeper of the baths (balneator), who exacted the quadrans paid by each visitor, was also stationed. The room (f) which runs back from the portico, might have been appropriated to him; but most probably it was an oecus or exedra, for the convenience of the better classes while awaiting the return of their acquaintances from the interior. In this court, advertisements for the theatre or other announcements of general interest were posted, one of which, announcing a gladiatorial show, still remains. At the sides of the entrance were seats (scholae).

The 1898 edition of Harper's Dictionary of Classical Antiquities provided illustrations envisioning the rooms of the Old Baths at Pompeii:

Apodyterium and frigidarium

[edit]A passage (c) leads into the apodyterium (B), a room for undressing in which all visitors must have met before entering the baths proper. Here, the bathers removed their clothing, which was taken in charge by slaves known as capsarii notorious in ancient times for their dishonesty.[20] The apodyterium was a spacious chamber, with stone seats along three sides of the wall (h). Holes are still visible on the walls, and probably mark the places where the pegs for the bathers' clothes were set. The chamber was lighted by a glass window, and had six doors. One of these led to the tepidarium (D) and another to the frigidarium (C), with its cold plunge-bath referred to as baptisterium (more commonly called natatorium or piscina), loutron,[dubious – discuss] natatio, or puteus; the terms natatio and natatorium suggest that some of those baths were also swimming pools. The bath in this chamber is of white marble, surrounded by two marble steps.

Tepidarium

[edit]

From the apodyterium the bather who wished to go through the warm bath and sweating process entered the tepidarium (D). It did not contain water either at Pompeii nor at the Baths of Hippias, but was merely heated with warm air of an agreeable temperature, in order to prepare the body for the great heat of the vapour and warm baths, and, upon returning, to prevent a too-sudden transition to the open air. In the baths at Pompeii this chamber also served as an apodyterium for those who took the warm bath. The walls feature a number of separate compartments or recesses for receiving the garments when taken off. The compartments are divided from each other by figures of the kind called atlantes or telamones, which project from the walls and support a rich cornice above them in a wide arch.

Three bronze benches were also found in the room, which was heated as well by its contiguity to the hypocaust of the adjoining chamber, as by a brazier of bronze (foculus), in which the charcoal ashes were still remaining when the excavation was made. Sitting and perspiring beside such a brazier was called ad flammam sudare.[21]

The tepidarium is generally the most highly ornamented room in baths. It was merely a room to sit and be anointed in. In the Forum Baths at Pompeii the floor is mosaic, the arched ceiling adorned with stucco and painting on a coloured ground, the walls red.

Anointing was performed by slaves called unctores and aliptae. It sometimes took place before going to the hot bath, and sometimes after the cold bath, before putting on the clothes, in order to check the perspiration.[22] Some baths had a special room (destrictarium or unctorium) for this purpose.

Caldarium

[edit]From the tepidarium a door opened into the caldarium (E), whose mosaic floor was directly above the furnace or hypocaust. Its walls also were hollow, behind the decorated plaster one part of the wall was made from interconnected hollow bricks called tubuli lateraci, forming a great flue filled with heated air. At one end was a round basin (labrum), and at the other a quadrangular bathing place (puelos, alveus, solium, calida piscina), approached from the platform by steps. The labrum held cold water, for pouring upon the bather's head before he left the room. These basins are of marble in the Old Baths, but we hear of alvei of solid silver.[23] Because of the great heat of the room, the caldarium was but slightly ornamented.

Laconicum

[edit]The Old Baths have no laconicum, which was a chamber still hotter than the caldarium, and used simply as a sweating-room, having no bath. It was said to have been introduced at Rome by Agrippa[24] and was also called sudatorium[contradictory] and assa.

Service areas

[edit]

The apodyterium has a passage (q) communicating with the mouth of the furnace (i), called praefurnium or propigneum and, passing down that passage, we reach the chamber M, into which the praefurnium projects, and which is entered from the street at c. It was assigned to the fornacatores, or persons in charge of the fires. Of its two staircases, one leads to the roof of the baths, and one to the boilers containing the water.

There were three boilers, one of which (caldarium) held the hot water; a second, the tepid (tepidarium); and the third, the cold (frigidarium). The warm water was filled into the warm bath by a pipe through the wall, marked on the plan. Underneath the hot chamber was set the circular furnace d, of more than 2 m (6 ft 7 in). in diameter, which heated the water and poured hot air into the hollow cells of the hypocaustum. It passed from the furnace under the first and last of the caldrons by two flues, which are marked on the plan. The boiler containing hot water was placed immediately over the furnace; as the water was drawn out from there, it was supplied from the next, the tepidarium, which was raised a little higher and stood a little way off from the furnace. It was already considerably heated from its contiguity to the furnace and the hypocaust below it, so that it supplied the deficiency of the former without materially diminishing its temperature; and the vacuum in this last was again filled up from the farthest removed, which contained the cold water received directly from the square reservoir seen behind them. The boilers themselves no longer remain, but the impressions which they have left in the mortar in which they were embedded are clearly visible, and enable us to determine their respective positions and dimensions. Such coppers or boilers appear to have been called miliaria, from their similarity of shape to a milestone.[25]

Behind the boilers, another corridor leads into the court or palaestra (K), appropriated to the servants of the bath.

Women's bath

[edit]The adjoining, smaller set of baths were assigned to the women. The entrance is by the door b, which conducts into a small vestibule (m) and from there into the apodyterium (H), which, like the one in the men's bath, has a seat (pulvinus, gradus) on either side built up against the wall. This opens upon a cold bath (J), answering to the natatio of the men's set, but of much smaller dimensions. There are four steps on the inside to descend into it.

Opposite to the door of entrance into the apodyterium is another doorway which leads to the tepidarium (G), which also communicates with the thermal chamber (F), on one side of which is a warm bath in a square recess, and at the farther extremity the labrum. The floor of this chamber is suspended, and its walls perforated for flues, like the corresponding one in the men's baths. The tepidarium in the women's baths had no brazier, but it had a hanging or suspended floor.

Purpose

[edit]

The baths often included, aside from the three main rooms listed above, a palaestra, or outdoor gymnasium where men would engage in various ball games and exercises. There, among other things, weights were lifted and the discus thrown. Men would oil themselves and remove the excess with a strigil (cf. the well known Apoxyomenus of Lysippus from the Vatican Museum). Often wealthy bathers would bring a capsarius, a slave that carried his master's towels, oils, and strigils to the baths and then watched over them once in the baths, as thieves and pickpockets were known to frequent the baths.

The changing room was known as the apodyterium (from Greek apodyterion from apoduein 'to take off').

Cultural significance

[edit]In many ways, baths were the ancient Roman equivalent of community centres. Because the bathing process took so long, conversation was necessary. Many Romans would use the baths as a place to invite their friends to dinner parties, and many politicians would go to the baths to convince fellow Romans to join their causes. The thermae had many attributes in addition to the baths. There were libraries, rooms for poetry readings, and places to buy and eat food. The modern equivalent would be a combination of a library, art gallery, mall, restaurant, gym, and spa.[26]

One important function of the baths in Roman society was their role as what we would consider a "branch library" today. Many in the general public did not have access to the grand libraries in Rome and so as a cultural institution the baths served as an important resource where the more common citizen could enjoy the luxury of books. The Baths of Trajan, of Caracalla, and Diocletian all contained rooms determined to be libraries. They have been identified through the architecture of the baths themselves. The presence of niches in the walls are assumed to have been bookcases and have been shown to be sufficiently deep to have contained ancient scrolls. There is little documentation from the writers of the time that there did exist definitive public libraries maintained in the baths, but records have been found that indicated a slave from the imperial household was labelled vilicus thermarum bybliothecae Graecae ('maintenance man of the Greek library of the baths'). However, this may only indicate that the same slave held two positions in succession: "maintenance man of the baths" (vilicus thermarum) and "employee in the Greek library" (a bybliothecae Graecae). The reason for this debate is that, although Julius Caesar and Asinius Pollio advocated for public access to books and that libraries be open to all readers, there is little evidence that public libraries existed in the modern sense as we know it. It is more likely that these reserves were maintained for the wealthy elite.[27]

Baths were a site for important sculpture; among the well-known pieces recovered from the Baths of Caracalla are the Farnese Bull and Farnese Hercules and over life-size early 3rd century patriotic figures, (now in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples).

The Romans believed that good health came from bathing, eating, massages, and exercise. The baths, therefore, had all of these things in abundance. Since some citizens would be bathing multiple times a week, Roman society was surprisingly clean.[28] When asked by a foreigner why he bathed once a day, a Roman emperor is said to have replied "Because I do not have the time to bathe twice a day."[29] Emperors often built baths to gain favour for themselves and to create a lasting monument of their generosity. If a rich Roman wished to gain the favour of the people, he might arrange for a free admission day in his name. For example, a senator hoping to become a Tribune might pay all admission fees at a particular bath on his birthday to become well known to the people of the area.[30]

Location

[edit]

Baths sprang up all over the empire. Where natural hot springs existed (as in Bath, England; Băile Herculane, Romania or Aquae Calidae near Burgas and Serdica, Bulgaria) thermae were built around them. Alternatively, a system of hypocausta (from hypo 'below' and kaio 'to burn') were utilised to heat the piped water from a furnace (praefurnium).

Remains of Roman public baths

[edit]A number of Roman public baths survive, either as ruins or in varying degrees of conservation. Among the more notable are those which give the English city of Bath its name and the Ravenglass Roman Bath House in England as well as the Baths of Caracalla, of Diocletian, of Titus, of Trajan in Rome and the baths of Sofia, Serdica and Varna.[31] Probably the most complete are various public and private baths in Pompeii and nearby sites. The Hammam Essalihine is still in use today.

In 1910, Pennsylvania Station was opened in New York City, with a Main Waiting Room that borrowed heavily from the frigidarium of the Baths of Diocletian, especially with the use of repeated groin vaults in the ceiling. The success of the design of Pennsylvania Station in turn was copied in other railroad stations around the world.

See also

[edit]- Ancient Roman bathing

- Chassenon Baths

- Diocletian window (thermal window)

- Greek baths

- History of sanitation

- Roman architecture

- Roman culture

- Roman engineering

- Roman technology

- Spa town

- Thermae Romae (manga and film)

- Victorian Turkish baths

- Ancient Baths of Alauna

- Bliesbruck Baths

- Gallo-Roman site of Sanxay

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Harry B. Evans (1997). Water Distribution in Ancient Rome: The Evidence of Frontinus. University of Michigan Press. pp. 9, 10. ISBN 0-472-08446-1. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07.

- ^ Daily life in ancient Rome : a sourcebook. Brian K. Harvey. Indianapolis. 2016. ISBN 978-1-58510-795-7. OCLC 924682988.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Stefano De Luca and Anna Lena, The Mosaic of the Thermal Bath Complex of Magdala Reconsidered: Archaeological Context, Epigraphy and Iconography [1]

- ^ More explicitly, "SALVOM LAVISSE (GAVDEO)", "(I'm glad) that you bathed safely", a common Latin formula for such wishes.

- ^ βαλανεῖον. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Varro, De Ling. Lat. ix. 68, ed. Müller (cited by Rich, 183)

- ^ Cicero, Ad Atticum ii. 3.

- ^ Cicero, Ad Fam. xiv. 20 (cited by Rich, 183).

- ^ Ep. 86 (cited by Rich, 183)

- ^ Ad Q. Frat. iii. 1. § 1 (cited by Rich, 183)

- ^ De Ling. Lat. viii. 25, ix. 41, ed. Müller (cited by Rich, 183)

- ^ Ep. ii. 17. (cited by Rich, 184)

- ^ Θέρμαι in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Juv. Sat. vii. 233 (cited by Rich, 184)

- ^ Sylv. i. 5. 13 (cited by Rich, 184)

- ^ vi. 42 (cited by Rich, 184)

- ^ ix. 76 (cited by Rich, 184)

- ^ The following is adapted from the 1898 Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities entry edited by Harry Thurston Peck.

- ^ Pro Cael. 26 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Dig. xlvii. 17 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Suet. Aug. 82 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Galen. x. 49 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Plin. H. N.xxxiii. 152 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Dio Cass. liii. 27 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Pallad. i. 40; v. 8 (cited by Peck)

- ^ Garrett G. Fagan (2002). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. University of Michigan Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-472-08865-3. Archived from the original on 2018-05-07.

- ^ Dix, Keith (1994). "'Public Libraries' in Ancient Rome: Ideology and Reality". Libraries & Culture. 29 (3): 288.

- ^ Andrews, Cath. "Ancient Roman Baths: Cleanliness and Godliness under one roof". Explore Italian Culture. Web. 4/22/12.

- ^ "NOVA Online | Secrets of Lost Empires | Roman Bath | A Day at the Baths". PBS. Archived from the original on 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- ^ Shephard, Roy J. (2014). An Illustrated History of Health and Fitness, from Pre-History to our Post-Modern World. Springer. p. 227. ISBN 9783319116716. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ "The Roman Thermae in Varna". Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1890). . Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (3rd ed.). London: John Murray. p. 183 et seq.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Peck, Harry Thurston, ed. (1898). "Balneae". Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper & Brothers.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Peck, Harry Thurston, ed. (1898). "Balneae". Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities. New York: Harper & Brothers.- Aaland, Mikkel (May 15, 1998). "Mass Bathing: The Roman Balnea and Thermae". Cyber-Bohemia. Archived from the original on June 26, 2016. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

Further reading

[edit]- Bruun, Christer. 1991. The water supply of ancient Rome: A study of Roman imperial administration. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica.

- DeLaine, Janet. 1997. The Baths of Caracalla: A Study In the Design, Construction, and Economics of Large-Scale Building Projects In Imperial Rome. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- DeLaine, Janet, and David E Johnston. 1999. Roman Baths and Bathing: Proceedings of the First International Conference On Roman Baths Held At Bath, England, 30 March-4 April 1992. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Fagan, Garrett G. 2001. "The genesis of the Roman public bath: Recent approaches and future directions". American Journal of Archaeology 105, no. 3: 403–26.

- Manderscheid, Hubertus. 2004. Ancient Baths and Bathing: A Bibliography for the Years 1988-2001. Portsmouth, RI: Journal of Roman Archaeology.

- Marvin, M. 1983. "Freestanding sculptures from the Baths of Caracalla". American Journal of Archaeology 87: 347–84.

- Nielsen, Inge. 1993. Thermae Et Balnea: The Architecture and Cultural History of Roman Public Baths. 2nd ed. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press.

- Ring, James W. 1996. "Windows, baths and solar energy in the Roman Empire". American Journal of Archaeology 100: 717–24.

- Rotherham, Ian D. 2012. Roman Baths In Britain. Stroud: Amberley.

- Roupas, N. 2012. "Roman bath tiles". Archaeology 65, no. 2: 12.

- Yegül, Fikret K. 1992. Baths and bathing in classical antiquity. New York: Architectural History Foundation.

- --. 2010. Bathing In the Roman World. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Eliav, Yaron Z., "A Jew in the Roman Bathhouse: Cultural Interaction in the Ancient Mediterranean", Princeton University Press (2023)

External links

[edit]- William Smith Roman Baths (Balneae) from "A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities", pub. John Murray, London, 1875.

- ThermeMuseum (Museum of the Thermae) in Heerlen Archived 2008-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Traianus – Technical investigation of Roman public works

- Roman Bath: a day at the baths An interactive site using the Baths of Caracalla as an example

- Barbara F. McManus Roman baths and bathing

- 3d reconstruction of a Roman baths Limes in Austria Archived 2011-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

- Roman Baths of Weissenburg Digital Media Archive Archived 2011-12-02 at the Wayback Machine (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas) with data from a City of Weissenburg/CyArk research partnership

- Victorian Turkish bath Information regarding a 19th-century version of the Roman or "Turkish" bath

- "The Roman Baths and Solar Heating". solarhousehistory.com. 20 January 2014.