Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ancient Roman engineering

View on Wikipedia

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east,[clarification needed] but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

Roman roads

[edit]

Roman roads were constructed to be immune to floods and other environmental hazards. Some roads built by the Romans are still in use today.

There were several variations on a standard Roman road. Most of the higher quality roads were composed of five layers. The bottom layer, called the pavimentum, was one inch thick and made of mortar. Above this were four strata of masonry. The layer directly above the pavimentum was called the statumen. It was one foot thick, and was made of stones bound together by cement or clay.

Above that, there was the rudens, which was made of ten inches of rammed concrete. The next layer, the nucleus, was made of twelve to eighteen inches of successively laid and rolled layers of concrete. Summa crusta of silex or lava polygonal slabs, one to three feet in diameter and eight to twelve inches thick, were laid on top of the rudens. The final upper surface was made of concrete or well-smoothed and fitted flint.

Generally, when a road encountered an obstacle, the Romans preferred to engineer a solution to the obstacle rather than redirecting the road around it: bridges were constructed over all sizes of waterway; marshy ground was handled by the construction of raised causeways with firm foundations; hills and outcroppings were frequently cut or tunneled through rather than avoided (the tunnels were made with rectangle hard rock block).

Aqueducts

[edit]

A thousand cubic metres (260,000 US gal) of water were brought into Rome by eleven different aqueducts each day. Per capita water usage in ancient Rome matched that of modern-day cities like New York City or modern Rome. Most water was for public use, such as baths and sewers. De aquaeductu is the definitive two-volume treatise on 1st-century aqueducts of Rome, written by Frontinus.

The aqueducts could stretch from 10–100 km (10–60 mi) long, and typically descended from an elevation of 300 m (1,000 ft) above sea level at the source, to 100 m (330 ft) when they reached the reservoirs around the city. Roman engineers used inverted siphons to move water across a valley if they judged it impractical to build a raised aqueduct. The Roman legions were largely responsible for building the aqueducts. Maintenance was often done by slaves.[2]

The Romans were among the first civilizations to harness the power of water. They built some of the first watermills outside of Greece for grinding flour and spread the technology for constructing watermills throughout the Mediterranean region. A famous example occurs at Barbegal in southern France, where no fewer than 16 overshot mills built into the side of a hill were worked by a single aqueduct, the outlet from one feeding the mill below in a cascade.

They were also skilled in mining, building aqueducts needed to supply equipment used in extracting metal ores, e.g. hydraulic mining, and the building of reservoirs to hold the water needed at the minehead. It is known that they were also capable of building and operating mining equipment such as crushing mills and dewatering machines. Large diameter vertical wheels of Roman vintage, for raising water, have been excavated from the Rio Tinto mines in Southwestern Spain. They were closely involved in exploiting gold resources such as those at Dolaucothi in south west Wales and in north-west Spain, a country where gold mining developed on a very large scale in the early part of the first century AD, such as at Las Medulas.

Bridges

[edit]

Roman bridges were among the first large and lasting bridges ever built. They were built with stone, employing the arch as basic structure. Most utilized concrete as well. Built in 142 BC, the Pons Aemilius, later named Ponte Rotto (broken bridge) is the oldest Roman stone bridge in Rome, Italy.

The biggest Roman bridge was Trajan's bridge over the lower Danube, constructed by Apollodorus of Damascus, which remained for over a millennium the longest bridge to have been built both in terms of overall and span length. They were normally at least 18 meters above the body of water.

An example of temporary military bridge construction is the two Caesar's Rhine bridges.

Dams

[edit]The Romans built many dams for water collection, such as the Subiaco dams, two of which fed Anio Novus, the largest aqueduct supplying Rome. One of the Subiaco dams was reputedly the highest ever found or inferred. They built 72 dams in Spain, such as those at Mérida, and many more are known across the empire. At one site, Montefurado in Galicia, they appear to have built a dam across the river Sil to expose alluvial gold deposits in the bed of the river. The site is near the spectacular Roman gold mine of Las Medulas.

Several earthen dams are known from Britain, including a well-preserved example from Roman Lanchester, Longovicium, where it may have been used in industrial-scale smithing or smelting, judging by the piles of slag found at this site in northern England. Tanks for holding water are also common along aqueduct systems, and numerous examples are known from just one site, the gold mines at Dolaucothi in west Wales. Masonry dams were common in North Africa for providing a reliable water supply from the wadis behind many settlements.

Architecture

[edit]

The buildings and architecture of Ancient Rome were impressive. The Circus Maximus, for example, was large enough to be used as a stadium. The Colosseum also provides an example of Roman architecture at its finest. One of many stadiums built by the Romans, the Colosseum exhibits the arches and curves commonly associated with Roman buildings.

The Pantheon in Rome still stands a monument and tomb, and the Baths of Diocletian and the Baths of Caracalla are remarkable for their state of preservation, the former still possessing intact domes. Such massive public buildings were copied in numerous provincial capitals and towns across the empire, and the general principles behind their design and construction are described by Vitruvius writing at the turn of millennium in his monumental work De architectura.

The technology developed for the baths was especially impressive, especially the widespread use of the hypocaust for one of the first types of central heating developed anywhere. That invention was used not just in the large public buildings, but spread to domestic buildings such as the many villas which were built across the Empire.

Materials

[edit]The most common materials used were brick, stone or masonry, cement, concrete and marble. Brick came in many different shapes. Curved bricks were used to build columns, and triangular bricks were used to build walls.

Marble was mainly a decorative material. Augustus once boasted that he had turned Rome from a city of bricks to a city of marble. The Romans had originally brought marble over from Greece, but later found their own quarries in northern Italy.

Cement was made of hydrated lime (calcium oxide) mixed with sand and water. The Romans discovered that substituting or supplementing the sand with a pozzolanic additive, such as volcanic ash, would produce a very hard cement, known as hydraulic mortar or hydraulic cement. They used it widely in structures such as buildings, public baths and aqueducts, ensuring their survival into the modern era.

Mining

[edit]

The Romans were the first to exploit mineral deposits using advanced technology, especially the use of aqueducts to bring water from great distances to help operations at the pithead. Their technology is most visible at sites in Britain such as Dolaucothi where they exploited gold deposits with at least five long aqueducts tapping adjacent rivers and streams. They used the water to prospect for ore by unleashing a wave of water from a tank to scour away the soil and so reveal the bedrock with any veins exposed to sight. They used the same method (known as hushing) to remove waste rock, and then to quench hot rocks weakened by fire-setting.

Such methods could be very effective in opencast mining, but fire-setting was very dangerous when used in underground workings. They were made redundant with the introduction of explosives, although hydraulic mining is still used on alluvial tin ores. They were also used to produce a controlled supply to wash the crushed ore. It is highly likely that they also developed water-powered stamp mills to crush hard ore, which could be washed to collect the heavy gold dust.

At alluvial mines, they applied their hydraulic mining methods on a vast scale, such as Las Medulas in north-west Spain. Traces of tanks and aqueducts can be found at many other early Roman mines. The methods are described in great detail by Pliny the Elder in his Naturalis Historia. He also described deep mining underground, and mentions the need to dewater the workings using reverse overshot water-wheels, and actual examples have been found in many Roman mines exposed during later mining attempts. The copper mines at Rio Tinto were one source of such artefacts, where a set of 16 was found in the 1920s. They also used Archimedean screws to remove water in a similar way.

Military engineering

[edit]Engineering was also institutionally ingrained in the Roman military, who constructed forts, camps, bridges, roads, ramps, palisades, and siege equipment amongst others. One of the most notable examples of military bridge-building in the Roman Republic was Julius Caesar's bridge over the Rhine River. This bridge was completed in only ten days by a team of engineers. Their exploits in the Dacian wars under Trajan in the early 2nd century AD are recorded on Trajan's column in Rome.

The army was also closely involved in gold mining and probably built the extensive complex of leats and cisterns at the Roman gold mine of Dolaucothi in Wales shortly after conquest of the region in 75 AD.

Power technology

[edit]

Water wheel technology was developed to a high level during the Roman period, a fact attested both by Vitruvius (in De architectura) and by Pliny the Elder (in Naturalis Historia). The largest complex of water wheels existed at Barbegal near Arles, where the site was fed by a channel from the main aqueduct feeding the town. It is estimated that the site comprised sixteen separate overshot water wheels arranged in two parallel lines down the hillside. The outflow from one wheel became the input to the next one down in the sequence.

Twelve kilometers north of Arles, at Barbegal, near Fontvieille, where the aqueduct arrived at a steep hill, the aqueduct fed a series of parallel water wheels to power a flourmill. There are two aqueducts which join just north of the mill complex, and a sluice which enabled the operators to control the water supply to the complex. There are substantial masonry remains of the water channels and foundations of the individual mills, together with a staircase rising up the hill upon which the mills are built. The mills apparently operated from the end of the 1st century until about the end of the 3rd century.[3] The capacity of the mills has been estimated at 4.5 tons of flour per day, sufficient to supply enough bread for the 12,500 inhabitants occupying the town of Arelate at that time.[4]

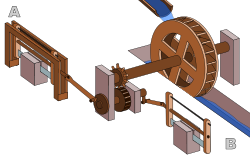

The Hierapolis sawmill was a Roman water-powered stone saw mill at Hierapolis, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Dating to the second half of the 3rd century AD,[5] the sawmill is the earliest known machine to combine a crank with a connecting rod.[6]

The watermill is shown on a raised relief on the sarcophagus of Marcus Aurelius Ammianos, a local miller. A waterwheel fed by a mill race is shown powering two frame saws via a gear train cutting rectangular blocks.[7]

Further crank and connecting rod mechanisms, without gear train, are archaeologically attested for the 6th-century AD water-powered stone sawmills at Gerasa, Jordan, and Ephesus, Turkey.[8] Literary references to water-powered marble saws in Trier, now Germany, can be found in Ausonius's late 4th-century AD poem Mosella. They attest a diversified use of water-power in many parts of the Roman Empire.[9]

A complex of mills also existed on the Janiculum in Rome fed by the Aqua Traiana. The Aurelian Walls were carried up the hill apparently to include the water mills used to grind grain towards providing bread flour for the city. The mill was thus probably built at the same time as or before the walls were built by the emperor Aurelian (reigned 270–275 AD). The mills were supplied from an aqueduct, where it plunged down a steep hill.[10]

The site thus resembles Barbegal, although excavations in the late 1990s suggest that they may have been undershot rather than overshot in design. The mills were in use in 537 AD when the Goths besieging the city cut off their water supply. However they were subsequently restored and may have remained in operation until at least the time of Pope Gregory IV (827–44).[11]

Many other sites are reported from across the Roman Empire, although many remain unexcavated.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Duruy, Victor, and J. P. Mahaffy. History of Rome and the Roman People: From Its Origin to the Establishment of the Christian Empire. London: K. Paul, Trench & Co, 1883. Page 17

- ^ Vinati, Simona and Piaggi, Marco de. "Roman Aqueducts, Aqueducts in Rome." Rome.info. Web. 5/1/2012

- ^ "Ville d'Histoire et de Patrimonie". Archived from the original on 2013-12-06.

- ^ "La meunerie de Barbegal". Archived from the original on 2007-01-17. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 140

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, p. 161

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 139–141

- ^ Ritti, Grewe & Kessener 2007, pp. 149–153

- ^ Wilson 2002, p. 16

- ^ Örjan Wikander, 'Water-mills in Ancient Rome' Opuscula Romana XII (1979), 13–36.

- ^ Örjan Wikander, 'Water-mills in Ancient Rome' Opuscula Romana XII (1979), 13–36.

Bibliography

[edit]- Davies, Oliver (1935). Roman Mines in Europe. Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Healy, A.F. (1999). Pliny the Elder on Science and Technology. Oxford: Clarendon.

- Hodge, T. (2001). Roman aqueducts and Water supply (2nd ed.). Duckworth.

- Ritti, Tullia; Grewe, Klaus; Kessener, Paul (2007), "A Relief of a Water-powered Stone Saw Mill on a Sarcophagus at Hierapolis and its Implications", Journal of Roman Archaeology, 20: 138–163, doi:10.1017/S1047759400005341, S2CID 161937987

- Smith, Norman (1972). A History of Dams. Citadel Press.

- Wilson, Andrew (2002), "Machines, Power and the Ancient Economy", The Journal of Roman Studies, vol. 92, pp. 1–32, doi:10.2307/3184857, JSTOR 3184857, S2CID 154629776

Further reading

[edit]- Cuomo, Serafina. 2008. "Ancient written sources for engineering and technology." In The Oxford handbook of engineering and technology in the classical world. Edited by John P. Oleson, 15–34. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Greene, Kevin. 2003. "Archaeology and technology." In A companion to archaeology. Edited by John L. Bintliff, 155–173. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Humphrey, John W. 2006. Ancient technology. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

- McNeil, Ian, ed. 1990. An encyclopedia of the history of technology. London: Routledge.

- Oleson, John P., ed. 2008. The Oxford handbook of engineering and technology in the classical world. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Rihll, Tracey E. 2013. Technology and society in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. Washington, DC: American Historical Society.

- White, Kenneth D. 1984. Greek and Roman technology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press.