Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Programming language

View on Wikipedia

This article has an unclear citation style. (August 2025) |

A programming language is an artificial language for expressing computer programs.[1]

Programming languages typically allow software to be written in a human readable manner.

Execution of a program requires an implementation. There are two main approaches for implementing a programming language – compilation, where programs are compiled ahead-of-time to machine code, and interpretation, where programs are directly executed. In addition to these two extremes, some implementations use hybrid approaches such as just-in-time compilation and bytecode interpreters.[2]

The design of programming languages has been strongly influenced by computer architecture, with most imperative languages designed around the ubiquitous von Neumann architecture.[3] While early programming languages were closely tied to the hardware, modern languages often hide hardware details via abstraction in an effort to enable better software with less effort.[citation needed]

Related

[edit]Programming languages have some similarity to natural languages in that they can allow communication of ideas between people. That is, programs are generally human-readable and can express complex ideas. However, the kinds of ideas that programming languages can express are ultimately limited to the domain of computation.[4]

The term computer language is sometimes used interchangeably with programming language[5] but some contend they are different concepts. Some contend that programming languages are a subset of computer languages.[6] Some use computer language to classify a language used in computing that is not considered a programming language.[citation needed] Some regard a programming language as a theoretical construct for programming an abstract machine, and a computer language as the subset thereof that runs on a physical computer, which has finite hardware resources.[7]

John C. Reynolds emphasizes that a formal specification language is as much a programming language as is a language intended for execution. He argues that textual and even graphical input formats that affect the behavior of a computer are programming languages, despite the fact they are commonly not Turing-complete, and remarks that ignorance of programming language concepts is the reason for many flaws in input formats.[8]

History

[edit]Early developments

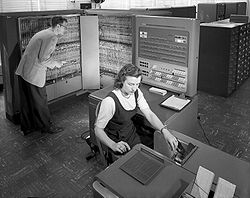

[edit]The first programmable computers were invented during the 1940s, and with them, the first programming languages.[9] The earliest computers were programmed in first-generation programming languages (1GLs), machine language (simple instructions that could be directly executed by the processor). This code was very difficult to debug and was not portable between different computer systems.[10] In order to improve the ease of programming, assembly languages (or second-generation programming languages—2GLs) were invented, diverging from the machine language to make programs easier to understand for humans, although they did not increase portability.[11]

Initially, hardware resources were scarce and expensive, while human resources were cheaper. Therefore, cumbersome languages that were time-consuming to use, but were closer to the hardware for higher efficiency were favored.[12] The introduction of high-level programming languages (third-generation programming languages—3GLs)—revolutionized programming. These languages abstracted away the details of the hardware, instead being designed to express algorithms that could be understood more easily by humans. For example, arithmetic expressions could now be written in symbolic notation and later translated into machine code that the hardware could execute.[11] In 1957, Fortran (FORmula TRANslation) was invented. Often considered the first compiled high-level programming language,[11][13] Fortran has remained in use into the twenty-first century.[14]

1960s and 1970s

[edit]

Around 1960, the first mainframes—general purpose computers—were developed, although they could only be operated by professionals and the cost was extreme. The data and instructions were input by punch cards, meaning that no input could be added while the program was running. The languages developed at this time therefore are designed for minimal interaction.[16] After the invention of the microprocessor, computers in the 1970s became dramatically cheaper.[17] New computers also allowed more user interaction, which was supported by newer programming languages.[18]

Lisp, implemented in 1958, was the first functional programming language.[19] Unlike Fortran, it supported recursion and conditional expressions,[20] and it also introduced dynamic memory management on a heap and automatic garbage collection.[21] For the next decades, Lisp dominated artificial intelligence applications.[22] In 1978, another functional language, ML, introduced inferred types and polymorphic parameters.[18][23]

After ALGOL (ALGOrithmic Language) was released in 1958 and 1960,[24] it became the standard in computing literature for describing algorithms. Although its commercial success was limited, most popular imperative languages—including C, Pascal, Ada, C++, Java, and C#—are directly or indirectly descended from ALGOL 60.[25][14] Among its innovations adopted by later programming languages included greater portability and the first use of context-free, BNF grammar.[26] Simula, the first language to support object-oriented programming (including subtypes, dynamic dispatch, and inheritance), also descends from ALGOL and achieved commercial success.[27] C, another ALGOL descendant, has sustained popularity into the twenty-first century. C allows access to lower-level machine operations more than other contemporary languages. Its power and efficiency, generated in part with flexible pointer operations, comes at the cost of making it more difficult to write correct code.[18]

Prolog, designed in 1972, was the first logic programming language, communicating with a computer using formal logic notation.[28][29] With logic programming, the programmer specifies a desired result and allows the interpreter to decide how to achieve it.[30][29]

1980s to 2000s

[edit]

During the 1980s, the invention of the personal computer transformed the roles for which programming languages were used.[31] New languages introduced in the 1980s included C++, a superset of C that can compile C programs but also supports classes and inheritance.[32] Ada and other new languages introduced support for concurrency.[33] The Japanese government invested heavily into the so-called fifth-generation languages that added support for concurrency to logic programming constructs, but these languages were outperformed by other concurrency-supporting languages.[34][35]

Due to the rapid growth of the Internet and the World Wide Web in the 1990s, new programming languages were introduced to support Web pages and networking.[36] Java, based on C++ and designed for increased portability across systems and security, enjoyed large-scale success because these features are essential for many Internet applications.[37][38] Another development was that of dynamically typed scripting languages—Python, JavaScript, PHP, and Ruby—designed to quickly produce small programs that coordinate existing applications. Due to their integration with HTML, they have also been used for building web pages hosted on servers.[39][40]

2000s to present

[edit]During the 2000s, there was a slowdown in the development of new programming languages that achieved widespread popularity.[41] One innovation was service-oriented programming, designed to exploit distributed systems whose components are connected by a network. Services are similar to objects in object-oriented programming, but run on a separate process.[42] C# and F# cross-pollinated ideas between imperative and functional programming.[43] After 2010, several new languages—Rust, Go, Swift, Zig and Carbon —competed for the performance-critical software for which C had historically been used.[44] Most of the new programming languages use static typing while a few numbers of new languages use dynamic typing like Ring and Julia.[45][46]

Some of the new programming languages are classified as visual programming languages like Scratch, LabVIEW and PWCT. Also, some of these languages mix between textual and visual programming usage like Ballerina.[47][48][49][50] Also, this trend lead to developing projects that help in developing new VPLs like Blockly by Google.[51] Many game engines like Unreal and Unity added support for visual scripting too.[52][53]

Definition

[edit]A language can be defined in terms of syntax (form) and semantics (meaning), and often is defined via a formal language specification.

Syntax

[edit]

A programming language's surface form is known as its syntax. Most programming languages are purely textual; they use sequences of text including words, numbers, and punctuation, much like written natural languages. On the other hand, some programming languages are graphical, using visual relationships between symbols to specify a program.

The syntax of a language describes the possible combinations of symbols that form a syntactically correct program. The meaning given to a combination of symbols is handled by semantics (either formal or hard-coded in a reference implementation). Since most languages are textual, this article discusses textual syntax.

The programming language syntax is usually defined using a combination of regular expressions (for lexical structure) and Backus–Naur form (for grammatical structure). Below is a simple grammar, based on Lisp:

expression ::= atom | list

atom ::= number | symbol

number ::= [+-]?['0'-'9']+

symbol ::= ['A'-'Z''a'-'z'].*

list ::= '(' expression* ')'

This grammar specifies the following:

- an expression is either an atom or a list;

- an atom is either a number or a symbol;

- a number is an unbroken sequence of one or more decimal digits, optionally preceded by a plus or minus sign;

- a symbol is a letter followed by zero or more of any alphabetical characters (excluding whitespace); and

- a list is a matched pair of parentheses, with zero or more expressions inside it.

The following are examples of well-formed token sequences in this grammar: 12345, () and (a b c232 (1)).

Not all syntactically correct programs are semantically correct. Many syntactically correct programs are nonetheless ill-formed, per the language's rules; and may (depending on the language specification and the soundness of the implementation) result in an error on translation or execution. In some cases, such programs may exhibit undefined behavior. Even when a program is well-defined within a language, it may still have a meaning that is not intended by the person who wrote it.

Using natural language as an example, it may not be possible to assign a meaning to a grammatically correct sentence or the sentence may be false:

- "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously." is grammatically well-formed but has no generally accepted meaning.

- "John is a married bachelor." is grammatically well-formed but expresses a meaning that cannot be true.

The following C language fragment is syntactically correct, but performs operations that are not semantically defined (the operation *p >> 4 has no meaning for a value having a complex type and p->im is not defined because the value of p is the null pointer):

complex *p = NULL;

complex abs_p = sqrt(*p >> 4 + p->im);

If the type declaration on the first line were omitted, the program would trigger an error on the undefined variable p during compilation. However, the program would still be syntactically correct since type declarations provide only semantic information.

The grammar needed to specify a programming language can be classified by its position in the Chomsky hierarchy. The syntax of most programming languages can be specified using a Type-2 grammar, i.e., they are context-free grammars.[54] Some languages, including Perl and Lisp, contain constructs that allow execution during the parsing phase. Languages that have constructs that allow the programmer to alter the behavior of the parser make syntax analysis an undecidable problem, and generally blur the distinction between parsing and execution.[55] In contrast to Lisp's macro system and Perl's BEGIN blocks, which may contain general computations, C macros are merely string replacements and do not require code execution.[56]

Semantics

[edit]| Logical connectives | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related concepts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Applications | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Semantics refers to the meaning of content that conforms to a language's syntax.

Static semantics

[edit]Static semantics defines restrictions on the structure of valid texts that are hard or impossible to express in standard syntactic formalisms.[57][failed verification] For compiled languages, static semantics essentially include those semantic rules that can be checked at compile time. Examples include checking that every identifier is declared before it is used (in languages that require such declarations) or that the labels on the arms of a case statement are distinct.[58] Many important restrictions of this type, like checking that identifiers are used in the appropriate context (e.g. not adding an integer to a function name), or that subroutine calls have the appropriate number and type of arguments, can be enforced by defining them as rules in a logic called a type system. Other forms of static analyses like data flow analysis may also be part of static semantics. Programming languages such as Java and C# have definite assignment analysis, a form of data flow analysis, as part of their respective static semantics.[59]

Dynamic semantics

[edit]Once data has been specified, the machine must be instructed to perform operations on the data. For example, the semantics may define the strategy by which expressions are evaluated to values, or the manner in which control structures conditionally execute statements. The dynamic semantics (also known as execution semantics) of a language defines how and when the various constructs of a language should produce a program behavior. There are many ways of defining execution semantics. Natural language is often used to specify the execution semantics of languages commonly used in practice. A significant amount of academic research goes into formal semantics of programming languages, which allows execution semantics to be specified in a formal manner. Results from this field of research have seen limited application to programming language design and implementation outside academia.[59]

Features

[edit]A language provides features for the programmer for develop software. Some notable features are described below.

Type system

[edit]A data type is a set of allowable values and operations that can be performed on these values.[60] Each programming language's type system defines which data types exist, the type of an expression, and how type equivalence and type compatibility function in the language.[61]

According to type theory, a language is fully typed if the specification of every operation defines types of data to which the operation is applicable.[62] In contrast, an untyped language, such as most assembly languages, allows any operation to be performed on any data, generally sequences of bits of various lengths.[62] In practice, while few languages are fully typed, most offer a degree of typing.[62]

Because different types (such as integers and floats) represent values differently, unexpected results will occur if one type is used when another is expected. Type checking will flag this error, usually at compile time (runtime type checking is more costly).[63] With strong typing, type errors can always be detected unless variables are explicitly cast to a different type. Weak typing occurs when languages allow implicit casting—for example, to enable operations between variables of different types without the programmer making an explicit type conversion. The more cases in which this type coercion is allowed, the fewer type errors can be detected.[64]

Commonly supported types

[edit]Early programming languages often supported only built-in, numeric types such as the integer (signed and unsigned) and floating point (to support operations on real numbers that are not integers). Most programming languages support multiple sizes of floats (often called float and double) and integers depending on the size and precision required by the programmer. Storing an integer in a type that is too small to represent it leads to integer overflow. The most common way of representing negative numbers with signed types is twos complement, although ones complement is also used.[65] Other common types include Boolean—which is either true or false—and character—traditionally one byte, sufficient to represent all ASCII characters.[66]

Arrays are a data type whose elements, in many languages, must consist of a single type of fixed length. Other languages define arrays as references to data stored elsewhere and support elements of varying types.[67] Depending on the programming language, sequences of multiple characters, called strings, may be supported as arrays of characters or their own primitive type.[68] Strings may be of fixed or variable length, which enables greater flexibility at the cost of increased storage space and more complexity.[69] Other data types that may be supported include lists,[70] associative (unordered) arrays accessed via keys,[71] records in which data is mapped to names in an ordered structure,[72] and tuples—similar to records but without names for data fields.[73] Pointers store memory addresses, typically referencing locations on the heap where other data is stored.[74]

The simplest user-defined type is an ordinal type, often called an enumeration, whose values can be mapped onto the set of positive integers.[75] Since the mid-1980s, most programming languages also support abstract data types, in which the representation of the data and operations are hidden from the user, who can only access an interface.[76] The benefits of data abstraction can include increased reliability, reduced complexity, less potential for name collision, and allowing the underlying data structure to be changed without the client needing to alter its code.[77]

Static and dynamic typing

[edit]In static typing, all expressions have their types determined before a program executes, typically at compile-time.[62] Most widely used, statically typed programming languages require the types of variables to be specified explicitly. In some languages, types are implicit; one form of this is when the compiler can infer types based on context. The downside of implicit typing is the potential for errors to go undetected.[78] Complete type inference has traditionally been associated with functional languages such as Haskell and ML.[79]

With dynamic typing, the type is not attached to the variable but only the value encoded in it. A single variable can be reused for a value of a different type. Although this provides more flexibility to the programmer, it is at the cost of lower reliability and less ability for the programming language to check for errors.[80] Some languages allow variables of a union type to which any type of value can be assigned, in an exception to their usual static typing rules.[81]

Concurrency

[edit]In computing, multiple instructions can be executed simultaneously. Many programming languages support instruction-level and subprogram-level concurrency.[82] By the twenty-first century, additional processing power on computers was increasingly coming from the use of additional processors, which requires programmers to design software that makes use of multiple processors simultaneously to achieve improved performance.[83] Interpreted languages such as Python and Ruby do not support the concurrent use of multiple processors.[84] Other programming languages do support managing data shared between different threads by controlling the order of execution of key instructions via the use of semaphores, controlling access to shared data via monitor, or enabling message passing between threads.[85]

Exception handling

[edit]Many programming languages include exception handlers, a section of code triggered by runtime errors that can deal with them in two main ways:[86]

- Termination: shutting down and handing over control to the operating system. This option is considered the simplest.

- Resumption: resuming the program near where the exception occurred. This can trigger a repeat of the exception, unless the exception handler is able to modify values to prevent the exception from reoccurring.

Some programming languages support dedicating a block of code to run regardless of whether an exception occurs before the code is reached; this is called finalization.[87]

There is a tradeoff between increased ability to handle exceptions and reduced performance.[88] For example, even though array index errors are common[89] C does not check them for performance reasons.[88] Although programmers can write code to catch user-defined exceptions, this can clutter a program. Standard libraries in some languages, such as C, use their return values to indicate an exception.[90] Some languages and their compilers have the option of turning on and off error handling capability, either temporarily or permanently.[91]

Design and implementation

[edit]One of the most important influences on programming language design has been computer architecture. Imperative languages, the most commonly used type, were designed to perform well on von Neumann architecture, the most common computer architecture.[92] In von Neumann architecture, the memory stores both data and instructions, while the CPU that performs instructions on data is separate, and data must be piped back and forth to the CPU. The central elements in these languages are variables, assignment, and iteration, which is more efficient than recursion on these machines.[93]

Many programming languages have been designed from scratch, altered to meet new needs, and combined with other languages. Many have eventually fallen into disuse.[citation needed] The birth of programming languages in the 1950s was stimulated by the desire to make a universal programming language suitable for all machines and uses, avoiding the need to write code for different computers.[94] By the early 1960s, the idea of a universal language was rejected due to the differing requirements of the variety of purposes for which code was written.[95]

Tradeoffs

[edit]Desirable qualities of programming languages include readability, writability, and reliability.[96] These features can reduce the cost of training programmers in a language, the amount of time needed to write and maintain programs in the language, the cost of compiling the code, and increase runtime performance.[97]

- Although early programming languages often prioritized efficiency over readability, the latter has grown in importance since the 1970s. Having multiple operations to achieve the same result can be detrimental to readability, as is overloading operators, so that the same operator can have multiple meanings.[98] Another feature important to readability is orthogonality, limiting the number of constructs that a programmer has to learn.[99] A syntax structure that is easily understood and special words that are immediately obvious also supports readability.[100]

- Writability is the ease of use for writing code to solve the desired problem. Along with the same features essential for readability,[101] abstraction—interfaces that enable hiding details from the client—and expressivity—enabling more concise programs—additionally help the programmer write code.[102] The earliest programming languages were tied very closely to the underlying hardware of the computer, but over time support for abstraction has increased, allowing programmers to express ideas that are more remote from simple translation into underlying hardware instructions. Because programmers are less tied to the complexity of the computer, their programs can do more computing with less effort from the programmer.[103] Most programming languages come with a standard library of commonly used functions.[104]

- Reliability means that a program performs as specified in a wide range of circumstances.[105] Type checking, exception handling, and restricted aliasing (multiple variable names accessing the same region of memory) all can improve a program's reliability.[106]

Programming language design often involves tradeoffs.[107] For example, features to improve reliability typically come at the cost of performance.[108] Increased expressivity due to a large number of operators makes writing code easier but comes at the cost of readability.[108]

Natural-language programming has been proposed as a way to eliminate the need for a specialized language for programming. However, this goal remains distant and its benefits are open to debate. Edsger W. Dijkstra took the position that the use of a formal language is essential to prevent the introduction of meaningless constructs.[109] Alan Perlis was similarly dismissive of the idea.[110]

Specification

[edit]The specification of a programming language is an artifact that the language users and the implementors can use to agree upon whether a piece of source code is a valid program in that language, and if so what its behavior shall be.

A programming language specification can take several forms, including the following:

- An explicit definition of the syntax, static semantics, and execution semantics of the language. While syntax is commonly specified using a formal grammar, semantic definitions may be written in natural language (e.g., as in the C language), or a formal semantics (e.g., as in Standard ML[111] and Scheme[112] specifications).

- A description of the behavior of a translator for the language (e.g., the C++ and Fortran specifications). The syntax and semantics of the language have to be inferred from this description, which may be written in natural or formal language.

- A reference or model implementation, sometimes written in the language being specified (e.g., Prolog or ANSI REXX[113]). The syntax and semantics of the language are explicit in the behavior of the reference implementation.

Implementation

[edit]An implementation of a programming language is the conversion of a program into machine code that can be executed by the hardware. The machine code then can be executed with the help of the operating system.[114] The most common form of interpretation in production code is by a compiler, which translates the source code via an intermediate-level language into machine code, known as an executable. Once the program is compiled, it will run more quickly than with other implementation methods.[115] Some compilers are able to provide further optimization to reduce memory or computation usage when the executable runs, but increasing compilation time.[116]

Another implementation method is to run the program with an interpreter, which translates each line of software into machine code just before it executes. Although it can make debugging easier, the downside of interpretation is that it runs 10 to 100 times slower than a compiled executable.[117] Hybrid interpretation methods provide some of the benefits of compilation and some of the benefits of interpretation via partial compilation. One form this takes is just-in-time compilation, in which the software is compiled ahead of time into an intermediate language, and then into machine code immediately before execution.[118]

Proprietary languages

[edit]Although most of the most commonly used programming languages have fully open specifications and implementations, many programming languages exist only as proprietary programming languages with the implementation available only from a single vendor, which may claim that such a proprietary language is their intellectual property. Proprietary programming languages are commonly domain-specific languages or internal scripting languages for a single product; some proprietary languages are used only internally within a vendor, while others are available to external users.[citation needed]

Some programming languages exist on the border between proprietary and open; for example, Oracle Corporation asserts proprietary rights to some aspects of the Java programming language,[119] and Microsoft's C# programming language, which has open implementations of most parts of the system, also has Common Language Runtime (CLR) as a closed environment.[120]

Many proprietary languages are widely used, in spite of their proprietary nature; examples include MATLAB, VBScript, and Wolfram Language. Some languages may make the transition from closed to open; for example, Erlang was originally Ericsson's internal programming language.[121]

Open source programming languages are particularly helpful for open science applications, enhancing the capacity for replication and code sharing.[122]

Use

[edit]Thousands of different programming languages have been created, mainly in the computing field.[123] Individual software projects commonly use five programming languages or more.[124]

Programming languages differ from most other forms of human expression in that they require a greater degree of precision and completeness. When using a natural language to communicate with other people, human authors and speakers can be ambiguous and make small errors, and still expect their intent to be understood. However, figuratively speaking, computers "do exactly what they are told to do", and cannot "understand" what code the programmer intended to write. The combination of the language definition, a program, and the program's inputs must fully specify the external behavior that occurs when the program is executed, within the domain of control of that program. On the other hand, ideas about an algorithm can be communicated to humans without the precision required for execution by using pseudocode, which interleaves natural language with code written in a programming language.

A programming language provides a structured mechanism for defining pieces of data, and the operations or transformations that may be carried out automatically on that data. A programmer uses the abstractions present in the language to represent the concepts involved in a computation. These concepts are represented as a collection of the simplest elements available (called primitives).[125] Programming is the process by which programmers combine these primitives to compose new programs, or adapt existing ones to new uses or a changing environment.

Programs for a computer might be executed in a batch process without any human interaction, or a user might type commands in an interactive session of an interpreter. In this case the "commands" are simply programs, whose execution is chained together. When a language can run its commands through an interpreter (such as a Unix shell or other command-line interface), without compiling, it is called a scripting language.[126]

Measuring language usage

[edit]Determining which is the most widely used programming language is difficult since the definition of usage varies by context. One language may occupy the greater number of programmer hours, a different one has more lines of code, and a third may consume the most CPU time. Some languages are very popular for particular kinds of applications. For example, COBOL is still strong in the corporate data center, often on large mainframes;[127][128] Fortran in scientific and engineering applications; Ada in aerospace, transportation, military, real-time, and embedded applications; and C in embedded applications and operating systems. Other languages are regularly used to write many different kinds of applications.

Various methods of measuring language popularity, each subject to a different bias over what is measured, have been proposed:

- counting the number of job advertisements that mention the language[129]

- the number of books sold that teach or describe the language[130]

- estimates of the number of existing lines of code written in the language – which may underestimate languages not often found in public searches[131]

- counts of language references (i.e., to the name of the language) found using a web search engine.

Combining and averaging information from various internet sites, stackify.com reported the ten most popular programming languages (in descending order by overall popularity): Java, C, C++, Python, C#, JavaScript, VB .NET, R, PHP, and MATLAB.[132]

As of June 2024, the top five programming languages as measured by TIOBE index are Python, C++, C, Java and C#. TIOBE provides a list of top 100 programming languages according to popularity and update this list every month.[133]

According to IEEE Spectrum staff, today's most popular programming languages may remain dominant because of how AI works. As a result, new languages will have a harder time gaining popularity since coders will not write many programs in them.[134]

Dialects, flavors and implementations

[edit]A dialect of a programming language or a data exchange language is a (relatively small) variation or extension of the language that does not change its intrinsic nature. With languages such as Scheme and Forth, standards may be considered insufficient, inadequate, or illegitimate by implementors, so often they will deviate from the standard, making a new dialect. In other cases, a dialect is created for use in a domain-specific language, often a subset. In the Lisp world, most languages that use basic S-expression syntax and Lisp-like semantics are considered Lisp dialects, although they vary wildly as do, say, Racket and Clojure. As it is common for one language to have several dialects, it can become quite difficult for an inexperienced programmer to find the right documentation. The BASIC language has many dialects.

Classifications

[edit]Programming languages can be described per the following high-level yet sometimes overlapping classifications:[135]

- Imperative

An imperative programming language supports implementing logic encoded as a sequence of ordered operations. Most popularly used languages are classified as imperative.[136]

- Functional

A functional programming language supports successively applying functions to the given parameters. Although appreciated by many researchers for their simplicity and elegance, problems with efficiency have prevented them from being widely adopted.[137]

- Logic

A logic programming language is designed so that the software, rather than the programmer, decides what order in which the instructions are executed.[138]

- Object-oriented

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is characterized by features such as data abstraction, inheritance, and dynamic dispatch. OOP is supported by most popular imperative languages and some functional languages.[136]

- Markup

Although a markup language is not a programming language per se, it might support integration with a programming language.

- Special

There are special-purpose languages that are not easily compared to other programming languages.[139]

See also

[edit]- Comparison of programming languages (basic instructions)

- Comparison of programming languages

- Computer programming

- Computer science and Outline of computer science

- Domain-specific language

- Domain-specific modeling

- Educational programming language

- Esoteric programming language

- Extensible programming

- Category:Extensible syntax programming languages

- Invariant-based programming

- List of BASIC dialects

- List of open-source programming languages

- Lists of programming languages

- List of programming language researchers

- Programming languages used in most popular websites

- Language-oriented programming

- Logic programming

- Literate programming

- Metalanguage

- Metaprogramming

- Modeling language

- Programming language theory

- Pseudocode

- Rebol § Dialects

- Reflective programming

- Scientific programming language

- Scripting language

- Semantics (logic)

- Syntax (logic)

- Software engineering and List of software engineering topics

References

[edit]- ^ Information technology — Vocabulary.

- ^ Sebesta, Robert W. (2023). Concepts of Programming Languages (12th global ed.). Pearson. pp. 46–51. ISBN 978-1-292-43682-1.

- ^ Sebesta, Robert (2022). Concepts of Programming Languages: Global Edition (12th global ed.). Harlow: Pearson. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-292-43682-1.

- ^ Chauhan, Sharad (2013). "10". Programming Languages - Design and Constructs. University Science Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-93-81159-41-5. Retrieved 10 September 2025.

Like our natural languages, programming languages facilitate the expression and communication between people. However, programming languages differ from natural languages in two ways. First, programming languages also enables communication of ideas between people and computing machines. Second, programming languages have a narrower expressive domain than our natural languages. That is, they facilitate only the communication of computational ideas.

- ^ Robert A. Edmunds, The Prentice-Hall standard glossary of computer terminology, Prentice-Hall, 1985, p. 91

- ^ Pascal Lando, Anne Lapujade, Gilles Kassel, and Frédéric Fürst, Towards a General Ontology of Computer Programs Archived 7 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ICSOFT 2007 Archived 27 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 163–170

- ^ R. Narasimhan, Programming Languages and Computers: A Unified Metatheory, pp. 189—247 in Franz Alt, Morris Rubinoff (eds.) Advances in computers, Volume 8, Academic Press, 1994, ISBN 0-12-012108-5, p.215: "[...] the model [...] for computer languages differs from that [...] for programming languages in only two respects. In a computer language, there are only finitely many names—or registers—which can assume only finitely many values—or states—and these states are not further distinguished in terms of any other attributes. [author's footnote:] This may sound like a truism but its implications are far-reaching. For example, it would imply that any model for programming languages, by fixing certain of its parameters or features, should be reducible in a natural way to a model for computer languages."

- ^ John C. Reynolds, "Some thoughts on teaching programming and programming languages", SIGPLAN Notices, Volume 43, Issue 11, November 2008, p.109

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 519.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 520–521.

- ^ a b c Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 521.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 522.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 524.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 42–44.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 523–524.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 527.

- ^ a b c Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 528.

- ^ "How Lisp Became God's Own Programming Language". twobithistory.org. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 526.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 50.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 701–703.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 524–525.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 525.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 526–527.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 531.

- ^ a b Sebesta 2012, p. 79.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 530.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 532–533.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 534.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 534–535.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 535.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 736.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 536.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 536–537.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 538–539.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 97–99.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 542.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 474–475, 477, 542.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, pp. 542–543.

- ^ Gabbrielli & Martini 2023, p. 544.

- ^ Bezanson, Jeff; Karpinski, Stefan; Shah, Viral B.; Edelman, Alan (2012). "Julia: A Fast Dynamic Language for Technical Computing". arXiv:1209.5145 [cs.PL].

- ^ Ayouni, M. and Ayouni, M., 2020. Data Types in Ring. Beginning Ring Programming: From Novice to Professional, pp.51-98.

- ^ Sáez-López, J.M., Román-González, M. and Vázquez-Cano, E., 2016. Visual programming languages integrated across the curriculum in elementary school: A two year case study using "Scratch" in five schools. Computers & Education, 97, pp.129-141.

- ^ Fayed, M.S., Al-Qurishi, M., Alamri, A. and Al-Daraiseh, A.A., 2017, March. PWCT: visual language for IoT and cloud computing applications and systems. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Internet of things, Data and Cloud Computing (pp. 1-5).

- ^ Kodosky, J., 2020. LabVIEW. Proceedings of the ACM on Programming Languages, 4(HOPL), pp.1-54.

- ^ Fernando, A. and Warusawithana, L., 2020. Beginning Ballerina Programming: From Novice to Professional. Apress.

- ^ Baluprithviraj, K.N., Bharathi, K.R., Chendhuran, S. and Lokeshwaran, P., 2021, March. Artificial intelligence based smart door with face mask detection. In 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems (ICAIS) (pp. 543-548). IEEE.

- ^ Sewell, B., 2015. Blueprints visual scripting for unreal engine. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- ^ Bertolini, L., 2018. Hands-On Game Development without Coding: Create 2D and 3D games with Visual Scripting in Unity. Packt Publishing Ltd.

- ^ Michael Sipser (1996). Introduction to the Theory of Computation. PWS Publishing. ISBN 978-0-534-94728-6. Section 2.2: Pushdown Automata, pp.101–114.

- ^ Jeffrey Kegler, "Perl and Undecidability Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine", The Perl Review. Papers 2 and 3 prove, using respectively Rice's theorem and direct reduction to the halting problem, that the parsing of Perl programs is in general undecidable.

- ^ Marty Hall, 1995, Lecture Notes: Macros Archived 6 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine, PostScript version Archived 17 August 2000 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Aaby, Anthony (2004). Introduction to Programming Languages. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ Michael Lee Scott, Programming language pragmatics, Edition 2, Morgan Kaufmann, 2006, ISBN 0-12-633951-1, p. 18–19

- ^ a b Winskel, Glynn (5 February 1993). The Formal Semantics of Programming Languages: An Introduction. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73103-4.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 244.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 245.

- ^ a b c d Andrew Cooke. "Introduction To Computer Languages". Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 15, 408–409.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 249.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 260.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 250.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 254.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 272–273.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 280.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 289–290.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 255.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 244–245.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 477.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 211.

- ^ Leivant, Daniel (1983). Polymorphic type inference. ACM SIGACT-SIGPLAN symposium on Principles of programming languages. Austin, Texas: ACM Press. pp. 88–98. doi:10.1145/567067.567077. ISBN 978-0-89791-090-3.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 576.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 579.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 585.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 585–586.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 630, 634.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 635.

- ^ a b Sebesta 2012, p. 631.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 261.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 632.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 631, 635–636.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Nofre, Priestley & Alberts 2014, p. 55.

- ^ Nofre, Priestley & Alberts 2014, p. 60.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Frederick P. Brooks, Jr.: The Mythical Man-Month, Addison-Wesley, 1982, pp. 93–94

- ^ Busbee, Kenneth Leroy; Braunschweig, Dave (15 December 2018). "Standard Libraries". Programming Fundamentals – A Modular Structured Approach. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 8, 16.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 18, 23.

- ^ a b Sebesta 2012, p. 23.

- ^ Dijkstra, Edsger W. On the foolishness of "natural language programming." Archived 20 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine EWD667.

- ^ Perlis, Alan (September 1982). "Epigrams on Programming". SIGPLAN Notices Vol. 17, No. 9. pp. 7–13. Archived from the original on 17 January 1999.

- ^ Milner, R.; M. Tofte; R. Harper; D. MacQueen (1997). The Definition of Standard ML (Revised). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-63181-5.

- ^ Kelsey, Richard; William Clinger; Jonathan Rees (February 1998). "Section 7.2 Formal semantics". Revised5 Report on the Algorithmic Language Scheme. Archived from the original on 6 July 2006.

- ^ ANSI – Programming Language Rexx, X3-274.1996

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 28.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 29–30.

- ^ See: Oracle America, Inc. v. Google, Inc.[user-generated source]

- ^ "Guide to Programming Languages | ComputerScience.org". ComputerScience.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ "The basics". ibm.com. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- ^ Abdelaziz, Abdullah I.; Hanson, Kent A.; Gaber, Charles E.; Lee, Todd A. (2023). "Optimizing large real-world data analysis with parquet files in R: A step-by-step tutorial". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 33 (3) e5728. doi:10.1002/pds.5728. PMID 37984998.

- ^ "HOPL: an interactive Roster of Programming Languages". Australia: Murdoch University. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

This site lists 8512 languages.

- ^ Mayer, Philip; Bauer, Alexander (2015). "An empirical analysis of the utilization of multiple programming languages in open source projects". Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering – EASE '15. New York, NY, US: ACM. pp. 4:1–4:10. doi:10.1145/2745802.2745805. ISBN 978-1-4503-3350-4.

Results: We found (a) a mean number of 5 languages per project with a clearly dominant main general-purpose language and 5 often-used DSL types, (b) a significant influence of the size, number of commits, and the main language on the number of languages as well as no significant influence of age and number of contributors, and (c) three language ecosystems grouped around XML, Shell/Make, and HTML/CSS. Conclusions: Multi-language programming seems to be common in open-source projects and is a factor that must be dealt with in tooling and when assessing the development and maintenance of such software systems.

- ^ Abelson, Sussman, and Sussman. "Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vicki, Brown; Morin, Rich (1999). "Scripting Languages". MacTech. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017.

- ^ Georgina Swan (21 September 2009). "COBOL turns 50". Computerworld. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Ed Airey (3 May 2012). "7 Myths of COBOL Debunked". developer.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Nicholas Enticknap. "SSL/Computer Weekly IT salary survey: finance boom drives IT job growth". Computer Weekly. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Counting programming languages by book sales". Radar.oreilly.com. 2 August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008.

- ^ Bieman, J.M.; Murdock, V., Finding code on the World Wide Web: a preliminary investigation, Proceedings First IEEE International Workshop on Source Code Analysis and Manipulation, 2001

- ^ "Most Popular and Influential Programming Languages of 2018". stackify.com. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ "TIOBE Index". Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "IEEE Spectrum". Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 21.

- ^ a b Sebesta 2012, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Sebesta 2012, pp. 22–23.

Further reading

[edit]- Abelson, Harold; Sussman, Gerald Jay (1996). Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (2nd ed.). MIT Press. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

- Raphael Finkel: Advanced Programming Language Design, Addison Wesley 1995.

- Daniel P. Friedman, Mitchell Wand, Christopher T. Haynes: Essentials of Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2001.

- David Gelernter, Suresh Jagannathan: Programming Linguistics, The MIT Press 1990.

- Ellis Horowitz (ed.): Programming Languages, a Grand Tour (3rd ed.), 1987.

- Ellis Horowitz: Fundamentals of Programming Languages, 1989.

- Shriram Krishnamurthi: Programming Languages: Application and Interpretation, online publication Archived 30 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine.

- Gabbrielli, Maurizio; Martini, Simone (2023). Programming Languages: Principles and Paradigms (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3-031-34144-1.

- Bruce J. MacLennan: Principles of Programming Languages: Design, Evaluation, and Implementation, Oxford University Press 1999.

- John C. Mitchell: Concepts in Programming Languages, Cambridge University Press 2002.

- Nofre, David; Priestley, Mark; Alberts, Gerard (2014). "When Technology Became Language: The Origins of the Linguistic Conception of Computer Programming, 1950–1960". Technology and Culture. 55 (1): 40–75. doi:10.1353/tech.2014.0031. ISSN 0040-165X. JSTOR 24468397. PMID 24988794.

- Benjamin C. Pierce: Types and Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2002.

- Terrence W. Pratt and Marvin Victor Zelkowitz: Programming Languages: Design and Implementation (4th ed.), Prentice Hall 2000.

- Peter H. Salus. Handbook of Programming Languages (4 vols.). Macmillan 1998.

- Ravi Sethi: Programming Languages: Concepts and Constructs, 2nd ed., Addison-Wesley 1996.

- Michael L. Scott and Jonathan Aldrich: Programming Language Pragmatics, 5th ed., Morgan Kaufmann Publishers 2025.

- Sebesta, Robert W. (2012). Concepts of Programming Languages (10 ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-13-139531-2.

- Franklyn Turbak and David Gifford with Mark Sheldon: Design Concepts in Programming Languages, The MIT Press 2009.

- Peter Van Roy and Seif Haridi. Concepts, Techniques, and Models of Computer Programming, The MIT Press 2004.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Concepts and Paradigms. Prentice Hall 1990.

- David A. Watt and Muffy Thomas. Programming Language Syntax and Semantics. Prentice Hall 1991.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Processors. Prentice Hall 1993.

- David A. Watt. Programming Language Design Concepts. John Wiley & Sons 2004.

- Wilson, Leslie B. (2001). Comparative Programming Languages, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-71012-9.

Programming language

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A programming language is a formal language consisting of a set of instructions designed to produce various kinds of output, typically executed by a computer to perform computations.[3] Unlike natural languages, which are inherently ambiguous and evolve organically through human use, programming languages are precisely defined with unambiguous rules to ensure deterministic interpretation by machines.[12] Key attributes of a programming language include a vocabulary of keywords, operators, and symbols, combined according to strict grammar rules that dictate valid structures.[12] These elements serve the purpose of providing a human-readable means to control and direct machine behavior, allowing programmers to specify algorithms and data manipulations in a structured way.[2] Programming languages are distinct from markup languages, such as HTML, which structure and present content statically without processing or computational capabilities.[13] They also differ from query languages like SQL, which focus on data retrieval and manipulation within specific domains and are often not Turing complete in their core form, whereas programming languages are generally designed to be Turing complete, enabling the expression of any computable function given sufficient resources.[14] The formalization of concepts underlying programming languages traces back to theoretical foundations in computation, particularly Alan Turing's 1936 paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem," which introduced the idea of mechanical processes for computing functions and served as a conceptual precursor.[15]Syntax

In programming languages, syntax refers to the set of rules that define the valid combinations of symbols and characters forming well-formed expressions, statements, and programs.[16] These rules ensure that source code adheres to the language's structural conventions, distinguishing legal constructs from invalid ones without regard to their meaning or execution behavior.[17] Syntax is typically divided into lexical and phrase-level components. Lexical syntax governs the formation of basic tokens from the raw character stream, including identifiers (e.g., variable names likex or count), literals (e.g., numbers like 42 or strings like "hello"), operators (e.g., +, =), and keywords (e.g., if, while).[18] This phase, known as lexical analysis, is performed by a lexer or scanner, which groups characters into these tokens while ignoring whitespace and comments.[19] Phrase-level syntax, or syntactic grammar, then specifies how tokens combine into higher-level structures like expressions or blocks, using formal notations such as Backus-Naur Form (BNF).[20] BNF employs nonterminal symbols (enclosed in angle brackets) and production rules to describe recursive hierarchies, enabling precise specification of language structure.[21]

To validate syntax, compilers or interpreters use a two-stage parsing process. The lexer first converts the source code into a sequence of tokens, filtering out irrelevant elements like whitespace.[22] The parser then analyzes this token stream against the syntactic grammar, typically building a parse tree or abstract syntax tree to confirm adherence to the rules; if the structure is invalid, a syntax error is reported.[23] This separation allows modular implementation, with lexical rules often modeled as regular expressions for finite automata and syntactic rules as more expressive formal grammars.[24]

A representative example of syntactic grammar is the BNF for simple arithmetic expressions, which enforces operator precedence (multiplication over addition) and left-associativity through recursive nonterminals:

<expr> ::= <expr> + <term> | <term>

<term> ::= <term> * <factor> | <factor>

<factor> ::= <number> | (<expr>)

<expr> ::= <expr> + <term> | <term>

<term> ::= <term> * <factor> | <factor>

<factor> ::= <number> | (<expr>)

<number> is a terminal literal, and the hierarchy ensures expressions like 2 + 3 * 4 parse as 2 + (3 * 4) rather than (2 + 3) * 4.[25] This notation derives from the original ALGOL 60 report and remains foundational for defining expression grammars in many languages.[26]

Programming languages predominantly use context-free grammars (CFGs) for syntax specification, where production rules apply independently of surrounding context, facilitating unambiguous definitions and efficient parsing.[27] CFGs support linear-time parsing via algorithms like LR or LL, making them ideal for compiler design and enabling tools like Yacc or ANTLR to generate parsers automatically; their main drawback is inability to directly capture context-dependent features, such as ensuring identifiers are declared before use, which are deferred to semantic analysis.[28] Context-sensitive grammars (CSGs), which allow rules dependent on adjacent symbols, provide greater expressiveness for such constraints but complicate parsing—often requiring exponential time or undecidable general solutions—thus rarely used for core syntax to avoid impractical compiler complexity.[29]

Semantics

Semantics in programming languages concerns the study of meaning, providing a precise specification of what programs compute or the effects they produce.[30] This involves defining how syntactically valid programs—those that conform to the rules outlined in syntax—are interpreted to yield outputs or alter system states.[31] Semantics operates on abstract representations of programs, ensuring that the meaning is independent of particular implementations. Static semantics encompasses the compile-time constraints that ensure programs are well-formed beyond mere syntactic validity, including type checking, scoping rules, and other checks performed before execution.[30] For instance, scoping rules enforce that variable declarations precede their use, preventing references to undeclared identifiers, while type checking verifies that operations are applied to compatible types, such as ensuring arithmetic is performed only on numeric expressions.[32] These rules contribute to error detection early in the development process and are typically expressed through judgments like , where is a typing environment, is an expression, and is a type.[30] Dynamic semantics describes the runtime behavior of programs, detailing how they evolve during execution to produce results.[30] It includes operational semantics, which models execution as a series of step-by-step transitions between program configurations, such as to represent state changes in an imperative language.[33] For example, in structural operational semantics, an assignment like transitions the store to , where evaluates the arithmetic expression .[30] Denotational semantics, in contrast, assigns mathematical functions to programs, mapping syntactic constructs compositionally to elements in semantic domains; for instance, the meaning of a command sequence is the function composition , transforming input states to output states.[34] Formal methods for semantics often rely on abstract syntax trees (ASTs) to represent programs as hierarchical structures stripped of concrete syntactic details like parentheses or keywords.[32] Evaluation rules are then defined inductively over these trees; for example, in operational semantics, a rule might specify that a let-binding evaluates to the result of substituting the value of for in .[30] This approach facilitates proofs of properties like equivalence, such as showing .[30] Semantics distinguishes between approaches suited to imperative and declarative paradigms: imperative semantics emphasize the "how" of computation through explicit state transformations and execution sequences, as in operational models for languages like C, while declarative semantics focus on the "what" by denoting logical relations or functions independent of order, as in denotational models for functional languages like Haskell.[30]Historical Development

Precursors and Early Concepts

The origins of programming languages trace back to mechanical devices and mathematical theories predating electronic computers, laying foundational concepts for automated computation and instruction sequences. In 1801, Joseph Marie Jacquard invented a loom controlled by punched cards, which automated the weaving of complex textile patterns by selecting warp threads through a series of interchangeable cards linked into a chain.[35] This mechanism represented an early form of programmability, where instructions encoded on physical media directed mechanical operations, influencing later data input methods in computing.[36] Building on such mechanical precedents, Charles Babbage proposed the Analytical Engine in 1837, a general-purpose mechanical computer designed to perform arithmetic operations and execute stored instructions via punched cards.[37] Ada Lovelace, collaborating with Babbage, recognized the device's potential beyond calculation; in her extensive notes on Luigi Menabrea's 1842 article describing the Engine, she outlined algorithms, including the first published algorithm intended for machine implementation to compute Bernoulli numbers.[37] Lovelace's work highlighted the Analytical Engine's capacity for symbolic manipulation, foreshadowing programming as a creative process of composing instructions for non-numerical tasks.[38] Theoretical advancements in the early 20th century provided rigorous mathematical frameworks for computation. Alonzo Church developed lambda calculus in the 1930s as a formal system for expressing functions and their applications, serving as a model of computation equivalent to Turing machines.[39] Church's system, introduced in papers like "An Unsolvable Problem of Elementary Number Theory" (1936), formalized effective calculability through abstraction and substitution rules, influencing functional programming paradigms.[39] Complementing this, Kurt Gödel's incompleteness theorems, published in 1931, demonstrated that in any sufficiently powerful formal axiomatic system, there exist true statements that cannot be proved within the system, profoundly shaping understandings of computability limits and the undecidability inherent in formal languages.[40] Early formal systems further refined these ideas. In the 1920s, Emil Post introduced production systems—rule-based mechanisms for generating strings from axioms through substitutions—which modeled derivation processes in logic and anticipated string rewriting in programming.[41] Post's canonical systems, detailed in his 1921 dissertation and later works, emphasized finite production rules for theorem generation, providing a combinatorial basis for algorithmic specification.[41] Alan Turing's 1936 paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem" defined computability via an abstract machine model now known as the Turing machine, consisting of a tape, read/write head, and state table to simulate any algorithmic process.[15] This model proved the existence of uncomputable functions, establishing a universal standard for what constitutes a programmable computation.[15] Bridging theory to practical design, Konrad Zuse conceived Plankalkül in the early 1940s as the first high-level programming language, featuring variables, loops, conditionals, and array operations for algorithmic expression.[42] Intended for his Z3 computer but not implemented until the 1970s due to World War II disruptions, Plankalkül's notation allowed specification of complex programs like chess algorithms, marking a conceptual shift toward human-readable code over machine code.[42]1940s to 1970s

In the late 1940s, the transition from manual wiring and machine code to more abstract programming began with early efforts on pioneering computers. The ENIAC, completed in 1945, initially relied on physical reconfiguration via switches and cables for programming, but by 1948, assembly languages emerged to represent instructions symbolically, facilitating easier coding for its operations. In 1949, John Mauchly proposed Short Code, also known as Brief Code, as the first high-level programming language, implemented as an interpreter for mathematical problems on the BINAC computer; it used numeric opcodes to abstract arithmetic and control flow, marking a shift toward symbolic expression over binary machine instructions.[43][44][45] The 1950s saw the development of domain-specific high-level languages that prioritized readability and efficiency for emerging computational needs. FORTRAN, introduced in 1957 by John Backus and his team at IBM, was designed for scientific and engineering computations, featuring algebraic notation, subroutines, and automatic memory allocation to simplify complex numerical tasks on the IBM 704.[46][47] COBOL, specified in 1959 by a U.S. Department of Defense committee under CODASYL, targeted business data processing with English-like syntax for records, files, and reports, aiming to bridge non-technical users and computers.[48] Meanwhile, LISP, created in 1958 by John McCarthy at MIT, pioneered symbolic computation for artificial intelligence, using list structures and recursive functions to model mathematical logic and enable early AI research.[49][50] By the 1960s, languages emphasized structured programming and accessibility, influencing future designs. ALGOL 60, formalized in 1960 through international collaboration, introduced block structure for lexical scoping, nested procedures, and a rigorous syntax via Backus-Naur Form, becoming a foundational model for procedural languages despite limited initial adoption.[51][52] BASIC, developed in 1964 by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz at Dartmouth College, democratized computing for education through simple, interactive syntax on time-sharing systems, allowing beginners to write and run programs in minutes.[53][54] Simula 67, released in 1967 by Kristen Nygaard and Ole-Johan Dahl at the Norwegian Computing Center, extended ALGOL with classes and objects for simulation modeling, laying groundwork for object-oriented paradigms by encapsulating data and behavior.[55][56] The 1970s advanced systems-level and declarative approaches, solidifying high-level abstractions. C, developed from 1972 by Dennis Ritchie at Bell Labs, provided low-level control akin to assembly while offering portability and efficiency for Unix implementation, featuring pointers, structured types, and a compact syntax that influenced countless successors.[57][5] Prolog, formalized in 1972 by Alain Colmerauer, Robert Kowalski, and Philippe Roussel, enabled logic programming through declarative rules and unification, supporting automated theorem proving and natural language processing in AI applications.[58][59] Throughout this era, programming evolved from machine-specific codes to portable, high-level abstractions, reducing development time and errors while expanding accessibility across domains. Standardization efforts, such as ANSI's 1966 FORTRAN approval and 1968 COBOL ratification, promoted interoperability and vendor neutrality, fostering wider adoption and compiler improvements.[60][61]1980s to 2000s

The 1980s marked a period of significant diversification in programming languages, driven by the proliferation of personal computers and the need for more structured and safe code in complex systems. C++, developed by Bjarne Stroustrup at Bell Labs, extended the C language by incorporating object-oriented programming (OOP) features such as classes, inheritance, and polymorphism, with its first implementation released in 1985.[62] This allowed programmers to build more modular and reusable code while maintaining C's performance efficiency, influencing systems programming and software engineering practices. Concurrently, Ada, designed under a U.S. Department of Defense contract and standardized in 1983, emphasized reliability for safety-critical applications like avionics and defense systems through strong typing, exception handling, and concurrency support.[63] Towards the decade's end, Perl, created by Larry Wall in 1987 as a Unix scripting tool, gained traction for text processing and report generation, leveraging regular expressions and pragmatic syntax to automate administrative tasks efficiently.[64] Entering the 1990s, the rise of the internet and cross-platform needs spurred languages focused on portability and simplicity. Python, initiated by Guido van Rossum at the Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica in 1989 and first released in 1991, prioritized readability and ease of use with its indentation-based syntax and dynamic typing, making it ideal for rapid prototyping and scripting.[65] Java, developed by James Gosling and his team at Sun Microsystems, debuted in 1995 with the goal of platform independence via the Java Virtual Machine (JVM), enabling "write once, run anywhere" for applets and enterprise applications through automatic memory management and OOP principles.[66] That same year, JavaScript, invented by Brendan Eich at Netscape in just ten days, introduced client-side scripting to web browsers, allowing dynamic HTML manipulation and interactivity without server round-trips.[67] The 2000s saw further maturation with languages integrating multiple paradigms and supporting emerging web ecosystems. C#, introduced by Microsoft in 2000 as part of the .NET Framework, combined C++'s power with Visual Basic's simplicity and Java-like features, including garbage collection and type safety, to streamline Windows development and later cross-platform applications.[68] Ruby, designed by Yukihiro Matsumoto in 1995 but popularized in the 2000s through frameworks like Ruby on Rails (2004), emphasized developer happiness with elegant syntax blending OOP and functional elements, facilitating web application development.[69] Scala, created by Martin Odersky at EPFL and publicly released in 2004, ran on the JVM while fusing functional programming (e.g., higher-order functions) with OOP, appealing to data-intensive and concurrent systems.[70] Key trends during this era included the widespread adoption of garbage collection for automatic memory management, reducing errors in languages like Java, Python, and C#, which improved productivity over manual allocation in earlier systems.[68] Web scripting languages such as JavaScript and Perl enabled dynamic content on the burgeoning internet, transforming static pages into interactive experiences.[67] Cross-platform portability advanced through virtual machines and bytecode compilation, as seen in Java and later Scala, supporting deployment across diverse hardware without recompilation.[66] The open-source movement, exemplified by Python and Ruby's permissive licenses, fostered global collaboration and rapid innovation in community-driven ecosystems.[65]2010s to Present

The 2010s marked a period of innovation in programming languages, driven by the demands of scalable cloud infrastructure, mobile ecosystems, and systems-level reliability. Google's Go, initially developed in 2007 and publicly released in 2009, gained prominence throughout the decade for its built-in support for concurrency through lightweight goroutines and channels, enabling efficient handling of networked and multicore applications without the complexities of traditional threading models.[71] Apple's Swift, introduced in 2014 at the Worldwide Developers Conference, was designed specifically for iOS and macOS development, offering a modern syntax that builds on Objective-C while incorporating features like optionals and protocol-oriented programming to enhance safety and expressiveness in app ecosystems. Meanwhile, Rust achieved its first stable release in 2015, introducing a novel ownership model enforced by a compile-time borrow checker that guarantees memory safety and prevents data races without relying on garbage collection, making it ideal for performance-critical systems where traditional languages like C++ risked vulnerabilities.[72] Entering the 2020s, languages continued to evolve in response to specialized computing needs up to 2025. Julia, first released in 2012, rose in adoption for numerical and scientific computing due to its just-in-time compilation, which delivers C-like performance for mathematical operations while maintaining the interactivity of dynamic languages like Python or MATLAB.[73] Kotlin, announced by JetBrains in 2011 and designated as Android's preferred language by Google in 2017, streamlined mobile development with null safety, coroutines for asynchronous programming, and seamless interoperability with Java, reducing boilerplate code in large-scale applications.[74] WebAssembly, with its minimum viable product shipped in 2017, extended the web platform by allowing compilation of languages such as C++, Rust, and others into a portable binary format that executes at near-native speeds in browsers, bypassing JavaScript's limitations for compute-intensive tasks.[75] Emerging trends in this era highlighted domain-specific adaptations and accessibility. TensorFlow's extensions within Python functioned as embedded domain-specific languages for artificial intelligence, providing high-level abstractions for building and training machine learning models through APIs like Keras, which simplified tensor operations and neural network design without sacrificing underlying flexibility.[76] Microsoft's Q#, released in 2017 as part of the Quantum Development Kit, emerged as a standalone language for quantum algorithm development, integrating classical and quantum control flows to simulate and execute on quantum hardware while abstracting qubit manipulations.[77] Low-code and no-code platforms, proliferating since the mid-2010s, blurred traditional programming boundaries by offering visual interfaces and drag-and-drop components that generate underlying code, enabling non-experts to build applications and thus democratizing software creation.[78] Notable recent developments include Mojo, a superset of Python released in 2023 by Modular, aimed at high-performance AI and machine learning with near-C speeds while preserving Python's usability, and Carbon, announced by Google in 2022 as an experimental successor to C++ focusing on interoperability and safety.[79][80] These developments were shaped by broader influences emphasizing performance, security, sustainability, and inclusivity. Languages like Go and Rust prioritized high performance in distributed systems, with Rust's borrow checker exemplifying zero-cost abstractions for secure concurrency.[81] Sustainability gained focus through energy-efficient designs in languages like Rust, which avoids garbage collection, and ongoing research into optimizing consumption across implementations to minimize computational carbon footprints in data centers.[82] Inclusivity advanced through accessible tools and platforms that lower barriers for diverse developers, fostering broader participation in software engineering.Core Features

Abstraction and Modularity

Abstraction in programming languages refers to the process of simplifying complex systems by hiding implementation details and focusing on essential features, allowing programmers to work at higher levels of conceptualization. This enables the creation of reusable components that manage complexity without exposing underlying intricacies. For instance, abstraction facilitates the definition of procedures or functions that encapsulate specific operations, permitting users to invoke them without understanding their internal mechanics.[83][84] Modularity complements abstraction by organizing code into independent, self-contained units such as modules or packages, which promote separation of concerns and hierarchical structuring. These units define clear interfaces that specify what functionality is available while concealing how it is achieved, thereby supporting scalable software development. Key mechanisms include functions and procedures for grouping actions; classes and interfaces in object-oriented paradigms for encapsulating data and behavior; and namespaces for managing scoping and avoiding naming conflicts.[85][83] The benefits of abstraction and modularity are substantial, including enhanced code reuse across projects, improved maintainability through localized changes, and reduced debugging time by isolating issues to specific components. For example, modular design can decrease debug time proportionally to the number of modules, as errors are confined rather than propagating globally. In practice, ALGOL's block structure exemplifies early modularity by enabling nested scopes for local variables, allowing independent code segments with controlled visibility. Similarly, Python's import system supports modularity by searching for and binding modules to the local scope, enabling hierarchical package organization and efficient code sharing without redundant loading.[86][87][88][89] Abstraction operates at distinct levels, including data abstraction, which involves abstract data types that bundle data with operations while restricting direct access to internals, and control abstraction, which hides procedural details such as iteration in loops or recursion. Data abstraction, for example, allows representation of structures like sets through operations without specifying underlying lists or arrays. Control abstraction, meanwhile, permits defining custom flow constructs, evolving beyond built-in language features. These levels integrate with broader program organization to foster reusable, maintainable designs.[83][84]Control Flow and Structures