Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Beach nourishment

View on Wikipedia

Beach nourishment (also referred to as beach renourishment,[2] beach replenishment, or sand replenishment) describes a process by which sediment, usually sand, lost through longshore drift or erosion is replaced from other sources. A wider beach can reduce storm damage to coastal structures by dissipating energy across the surf zone, protecting upland structures and infrastructure from storm surges, tsunamis and unusually high tides.[citation needed] Beach nourishment is typically part of a larger integrated coastal zone management aimed at coastal defense. Nourishment is typically a repetitive process because it does not remove the physical forces that cause erosion; it simply mitigates their effects.

The first nourishment project in the United States was at Coney Island, New York in 1922 and 1923. It is now a common shore protection measure used by public and private entities.[3][4]

History

[edit]The first nourishment project in the U.S. was constructed at Coney Island, New York in 1922–1923.[5][6]

Before the 1970s, nourishment involved directly placing sand on the beach and dunes. Since then more shoreface nourishments have been carried out, which rely on the forces of the wind, waves and tides to further distribute the sand along the shore and onto the beaches and dunes.[7][8]

The number and size of nourishment projects has increased significantly due to population growth and projected relative sea-level rise.[8]

Erosion

[edit]Beach erosion is a specific subset of coastal erosion, which in turn is a type of bioerosion which alters coastal geography through beach morphodynamics. There are numerous incidences of the modern recession of beaches, mainly due to a gradient in longshore drift and coastal development hazards.

Causes of erosion

[edit]Beaches can erode naturally or due to human impact (beach theft/sand mining).[9]

Erosion is a natural response to storm activity. During storms, sand from the visible beach submerges to form sand bars that protect the beach. Submersion is only part of the cycle. During calm weather, smaller waves return sand from bars to the visible beach surface in a process called accretion.

Some beaches do not have enough sand available for coastal processes to respond naturally to storms. When not enough sand is available, the beach cannot recover after storms.

Many areas of high erosion are due to human activities. Reasons can include: seawalls locking up sand dunes, coastal structures like ports and harbors that prevent longshore transport, and dams and other river management structures. Continuous, long-term renourishment efforts, especially in cuspate-cape coastlines, can play a role in longshore transport inhibition and downdrift erosion.[10] These activities interfere with the natural sediment flows either through dam construction (thereby reducing riverine sediment sources) or construction of littoral barriers such as jetties, or by deepening of inlets; thus preventing longshore transport of sediment.[11]

Types of shoreline protection approaches

[edit]

The coastal engineering for the shoreline protection involves:

- Soft engineering: Beach nourishment is a type of soft approach which preserves beach resources and avoids the negative effects of hard structures. Instead, nourishment creates a “soft” (i.e., non-permanent) structure by creating a larger sand reservoir, pushing the shoreline seaward.

- Hard engineering: Beach evolution and beach accretion can be facilitated by the four main types of hard engineering structures in coastal engineering are, namely seawall, revetment, groyne or breakwater. Most commonly used hard structures are seawall and series of "headland breakwater" (breakwater connected to the shore with groyne).

- Managed retreat, the shoreline is left to erode, while buildings and infrastructure are relocated further inland.

Approach

[edit]Assessment

[edit]Advantages

[edit]- Widens the beach.

- Protects structures behind beach.

- Protects from storms.[12]

- Increases land value of nearby properties.

- Grows economy through tourism and recreation.[12][13]

- Expands habitat.[12]

- Practical, environmentally-friendly approach to address erosional pressure.[12]

- Encourages vegetation growth to help stabilize tidal flats.[13]

Disadvantages

[edit]- Added sand may erode because of storms or lack of up-drift sand sources.[13]

- Expensive and requires repeated application.[13]

- Restricted access during nourishment.[13]

- Destroys or buries marine life.[13]

- Difficulty finding appropriate materials.[13]

Considerations

[edit]Costs

[edit]Nourishment is typically a repetitive process, as nourishment mitigates the effects of erosion, but does not remove the causes. A benign environment increases the interval between nourishment projects, reducing costs. Conversely, high erosion rates may render nourishment financially impractical.[14][15]

In many coastal areas, the economic impacts of a wide beach can be substantial. Since 1923, the U.S. has spent $9 billion to rebuild beaches.[16] One of the most notable example is the 10 miles (16 km)–long shoreline fronting Miami Beach, Florida, which was replenished over the period 1976–1981. The project cost approximately US$86 million and revitalized the area's economy.[17] Prior to nourishment, in many places the beach was too narrow to walk along, especially during high tide.

In 1998 an overview was made of all known beach nourishment projects in the USA (418 projects). The total volume of all these nourishments was 648 million cubic yards (495 m3) with a total cost of US$3387 million (adjusted to price level 1996). This is US$6.84 per m3.[17] Between 2000 and 2020 the price per m3 has gone up considerably in the USA (see table below), while in Europe the price has gone down.

| location | year | quantity (million m3) |

cost (million US$) |

cost/m3 (US$) |

cost/m3 (€) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miami Beach[18] | 2017 | 0.388 | 11.5 | 33.7 | 38.1 |

| Myrtle Beach [19] | 1976 | 3.8 | 70.1 | 18.4 | 15.3 |

| Virginia Beach [20] | 2017 | 1.2 | 21.5 | 17.9 | 20.2 |

| Monmouth Beach[21] | 2021 | 0.84 | 26 | 20.1 | 23.7 |

| Carolina & Kure[22] | 2022 | 1.4 | 20.3 | 14.5 | 14.5 |

Around the North Sea prices are much lower. In 2000 an inventory was made by the North Sea Coastal Management Group.[23]

| country | beach nourishment | foreshore nourishment |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 10 - 18 | |

| Belgium | 5-10 | |

| Netherlands | 3.2 - 4.5 | 0.9 - 1.5 |

| Germany | 4.4 | |

| Denmark | 4.2 | 2.6 |

From the Netherlands more detailed data are available, see below in the section on Dutch case studies.

The price for nourishments in areas without an available dredging fleet is often in the order of €20 - €30 per cubic meter.

Storm damage reduction

[edit]A wide beach is a good energy absorber, which is significant in low-lying areas where severe storms can impact upland structures. The effectiveness of wide beaches in reducing structural damage has been proven by field studies conducted after storms and through the application of accepted coastal engineering principles.[12]

Environmental impact

[edit]Beach nourishment has significant impacts on local ecosystems. Nourishment may cause direct mortality to sessile organisms in the target area by burying them under the new sand. The seafloor habitat in both source and target areas are disrupted, e.g. when sand is deposited on coral reefs or when deposited sand hardens. Imported sand may differ in character (chemical makeup, grain size, non-native species) from that of the target environment. Light availability may be reduced, affecting nearby reefs and submerged aquatic vegetation. Imported sand may contain material toxic to local species. Removing material from near-shore environments may destabilize the shoreline, in part by steepening its submerged slope. Related attempts to reduce future erosion may provide a false sense of security that increases development pressure.[24]

Sea turtles

[edit]Newly deposited sand can harden and complicate nest-digging for turtles. However, nourishment can provide more and better habitat for them, as well as for sea birds and beach flora. Florida addressed the concern that dredge pipes would suck turtles into the pumps by adding a special grill to the dredge pipes.[25]

Material used

[edit]The selection of suitable material for a particular project depends upon the design needs, environmental factors and transport costs, considering both short and long-term implications.[26]

The most important material characteristic is the sediment grain size, which must closely match the native material. Excess silt and clay fraction (mud) versus the natural turbidity in the nourishment area disqualifies some materials. Projects with unmatched grain sizes performed relatively poorly. Nourishment sand that is only slightly smaller than native sand can result in significantly narrower equilibrated dry beach widths compared to sand the same size as (or larger than) native sand. Evaluating material fit requires a sand survey that usually includes geophysical profiles and surface and core samples.[26]

| Type | Description | Environmental issues |

|---|---|---|

| Offshore | Exposure to open sea makes this the most difficult operational environment. Must consider the effects of altering depth on wave energy at the shoreline. May be combined with a navigation project. | Impacts on hard bottom and migratory species.[26] |

| Inlet | Sand between jetties in a stabilized inlet. Often associated with dredging of navigational channels and the ebb- or flood-tide deltas of both natural and jettied inlets.[26] | |

| Accretionary Beach | Generally not suitable because of damage to source beach.[26] | |

| Upland | Generally the easiest to obtain permits and assess impacts from a land source. Offers opportunities for mitigation. Limited quantity and quality of economical deposits.[26] | Potential secondary impacts from mining and overland transport. |

| Riverine | Potentially high quality and sizeable quantity. Transport distance a possible cost factor. | May interrupt natural coastal sand supply.[26] |

| Lagoon | Often excessively fine grained. Often close to barrier beaches and in sheltered waters, easing construction. Principal sources are flood-tide deltas.[26] | Can compromise wetlands. |

| Artificial or non-indigenous | Typically, high transport and redistribution costs. Some laboratory experiments done on recycling broken glass. Aragonite from Bahamas a possible source.[26] | |

| Emergency | Deposits near inlets and local sinks and sand from stable beaches with adequate supply. Generally used only following a storm or given no other affordable option. May be combined with a navigation project.[26] | Harm to source site. Poor match to target requirements. |

Some beaches were nourished using a finer sand than the original. Thermoluminescence monitoring reveals that storms can erode such beaches far more quickly. This was observed at a Waikiki nourishment project in Hawaii.[27]

Profile nourishment

[edit]Beach Profile Nourishment describes programs that nourish the full beach profile. In this instance, "profile" means the slope of the uneroded beach from above the water out to sea. The Gold Coast profile nourishment program placed 75% of its total sand volume below low water level. Some coastal authorities overnourish the below water beach (aka "nearshore nourishment") so that over time the natural beach increases in size. These approaches do not permanently protect beaches eroded by human activity, which requires that activity to be mitigated.[citation needed]

Project impact measurements

[edit]

Nourishment projects usually involve physical, environmental and economic objectives.

Typical physical measures include dry beach width/height, post-storm sand volume, post-storm damage avoidance assessments and aqueous sand volume.

Environmental measures include marine life distribution, habitat and population counts.

Economic impacts include recreation, tourism, flood and "disaster" prevention.

Many nourishment projects are advocated via economic impact studies that rely on additional tourist expenditure. This approach is however unsatisfactory. First, nothing proves that these expenditures are incremental (they could shift expenditures from other nearby areas). Second, economic impact does not account for costs and benefits for all economic agents, as cost benefit analysis does.[28] Techniques for incorporating nourishment projects into flood insurance costs and disaster assistance remain controversial.[29]

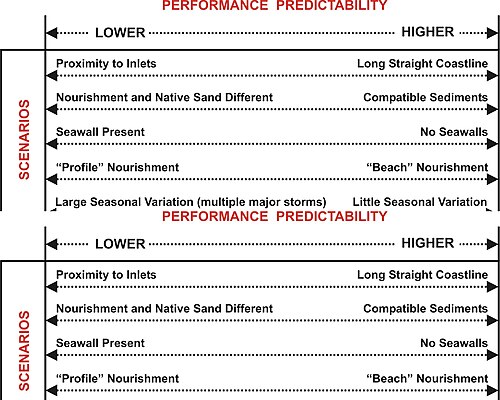

The performance of a beach nourishment project is most predictable for a long, straight shoreline without the complications of inlets or engineered structures. In addition, predictability is better for overall performance, e.g., average shoreline change, rather than shoreline change at a specific location.[citation needed]

Nourishment can affect eligibility in the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program and federal disaster assistance.[citation needed]

Nourishment may have the unintended consequence of promoting coastal development, which increases risk of other coastal hazards.[24]

Other shoreline protection approaches

[edit]Nourishment is not the only technique used to address eroding beaches. Others can be used singly or in combination with nourishment, driven by economic, environmental and political considerations.

Human activities such as dam construction can interfere with natural sediment flows (thereby reducing riverine sediment sources.) Construction of littoral barriers such as jetties and deepening of inlets can prevent longshore sediment transport.

Hard engineering or structural approach

[edit]The structural approach attempts to prevent erosion. Armoring involves building revetments, seawalls, detached breakwaters, groynes, etc. Structures that run parallel to the shore (seawalls or revetments) prevent erosion. While this protects structures, it doesn't protect the beach that is outside the wall. The beach generally disappears over a period that ranges from months to decades.[citation needed]

Groynes and breakwaters that run perpendicular to the shore protect it from erosion. Filling a breakwater with imported sand can stop the breakwater from trapping sand from the littoral stream (the ocean running along the shore.) Otherwise the breakwater may deprive downstream beaches of sand and accelerate erosion there.[30]

Armoring may restrict beach/ocean access, enhance erosion of adjacent shorelines, and requires long-term maintenance.[31]

Managed retreat

[edit]Managed retreat moves structures and other infrastructure inland as the shoreline erodes. Retreat is more often chosen in areas of rapid erosion and in the presence of little or obsolete development.

Soft engineering approaches

[edit]Beach dewatering

[edit]

Beaches grow and shrink depending on tides, precipitation, wind, waves and current. Wet beaches tend to lose sand. Waves infiltrate dry beaches easily and deposit sandy sediment. Generally a beach is wet during falling tide, because the sea sinks faster than the beach drains. As a result, most erosion happens during falling tide. Beach drainage (beach dewatering) using Pressure Equalizing Modules (PEMs) allow the beach to drain more effectively during falling tide. Fewer hours of wet beach translate to less erosion. Permeable PEM tubes inserted vertically into the foreshore connect the different layers of groundwater. The groundwater enters the PEM tube allowing gravity to conduct it to a coarser sand layer, where it can drain more quickly.[32] The PEM modules are placed in a row from the dune to the mean low waterline. Distance between rows is typically 300 feet (91 m) but this is project-specific. PEM systems come in different sizes. Modules connect layers with varying hydraulic conductivity. Air/water can enter and equalize pressure.[citation needed]

PEMs are minimally invasive, typically covering approximately 0.00005% of the beach.[citation needed] The tubes are below the beach surface, with no visible presence. PEM installations have been installed on beaches in Denmark, Sweden, Malaysia and Florida.[32] The effectiveness of beach dewatering has not been proven convincingly on life-sized beaches, in particular for the sand beach case.[33] Dewatering systems have been shown to lower very significantly the watertable but other morphodynamical effects generally overpower any stabilizing effect of dewatering for fine sediments,[34][35][36][37] although some mixed results on upper beach accretion associated to erosion in middle and lower have been reported.[38] This is in line with the current knowledge of swash-groundwater sediment dynamics which states that the effects of in/exfiltration flows through sand beds in the swash zone associated to modification of swash boundary layer and relative weight of the sediment and overall volume loss of the swash tongue are generally lower than other drivers, at least for fine sediments such as sand [39][40]

Recruitment

[edit]Appropriately constructed and sited fences can capture blowing sand, building/restoring sand dunes, and progressively protecting the beach from the wind, and the shore from blowing sand.[citation needed]

Dynamic revetment

[edit]Another approach is to create dynamic revetment, a berm using unmortared, unsorted rocks (cobbles). Seeds scattered among the cobbles can germinate to anchor the cobbles in place. Sand can collect and recreate a sandy beach. Leaving the rocks loose allows them to migrate and settle in a stable location. Separately, near the highest average waterline, a second berm around a meter in height can accelerate the recovery. This approach was employed at Washaway Beach in North Cove, Washington. Once the berms were in place, in one year the beach expanded by some 15 meters, and continued to grow. Projects in Washington, California, Europe, and Guam have adopted aspects of the techniques.[41]

Projects

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

The setting of a beach nourishment project is key to design and potential performance. Possible settings include a long straight beach, an inlet that may be either natural or modified and a pocket beach. Rocky or seawalled shorelines, that otherwise have no sediment, present unique problems.[citation needed]

Cancun, Mexico

[edit]Hurricane Wilma hit the beaches of Cancun and the Riviera Maya in 2005. The initial nourishment project was unsuccessful at a cost of $19 million, leading to a second round that began in September 2009 and was scheduled to complete in early 2010 with a cost of $70 million.[42] The project designers and the government committed to invest in beach maintenance to address future erosion. Project designers considered factors such as the time of year and sand characteristics such as density. Restoration in Cancun was expected to deliver 1.3 billion US gallons (4,900,000 m3) of sand to replenish 450 meters (1,480 ft) of coastline.

Northern Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia

[edit]Gold Coast beaches in Queensland, Australia have experienced periods of severe erosion. In 1967 a series of 11 cyclones removed most of the sand from Gold Coast beaches. The Government of Queensland engaged engineers from Delft University in the Netherlands to advise them. The 1971 Delft Report outlined a series of works for Gold Coast Beaches, including beach nourishment and an artificial reef. By 2005 most of the recommendations had been implemented.

The Northern Gold Coast Beach Protection Strategy (NGCBPS) was an A$10 million investment. NGCBPS was implemented between 1992 and 1999 and the works were completed between 1999 and 2003. The project included dredging 3,500,000 cubic metres (4,600,000 cu yd) of compatible sand from the Gold Coast Broadwater and delivering it through a pipeline to nourish 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) of beach between Surfers Paradise and Main Beach. The new sand was stabilized by an artificial reef constructed at Narrowneck out of huge geotextile sand bags. The new reef was designed to improve wave conditions for surfing. A key monitoring program for the NGCBPS is the ARGUS coastal camera system.

Netherlands

[edit]Background

[edit]More than one-quarter of the Netherlands is below sea level.[43] The coastline along the North Sea (approx. 300 kilometers (190 mi)) is protected against flooding by natural sand dunes (only in the estuaries and behind the barrier islands there are no dunes). This coastline is eroding for centuries; in the 19th and beginning of 20th centuries it was tried to stop erosion by construction of groynes, which was costly and not very successful. Beach nourishment was more successful, but there were questions on the method of funding. In the Coastal Memorandum of 1990 the government decided, after a very detailed study, that all erosion along the full Dutch coastline would be compensated by artificial beach nourishment.[44]

The shoreline is closely monitored by yearly recording of the cross section at points 250 meters (820 ft) apart, to ensure adequate protection. Where long-term erosion is identified, beach nourishment using high-capacity suction dredgers is deployed. In 1990 the Dutch government has decided to compensate in principle all coastal erosion by nourishment. This policy is still ongoing and successful. All costs are covered by the National Budget.[45] [46] [47]

A novel beach nourishment strategy was implemented in South Holland, where a new beach form was created using vast quantities of sand with the expectation that the sand would be distributed by natural processes to nourish the beach over many years (see Sand engine).

Basic Coastline

[edit]The basic coastline in the Netherlands is a representation of the low water line of 1990. This line is used to identify coastal erosion and coastal growth and to take measures if necessary. In the Coastal Memorandum,[44] the Dutch Government decides to maintain the 1990 coastline by beach nourishment. The coastline in question is the low-water line. For practical application, the definition of this does not appear to be unambiguous, which is why the Memorandum also defines the momentary coastline (also called instantaneous coastline) (MKL) and basic Coastline (BKL). Each year, the shoreline to be tested ( TKL) is determined on the basis of the MKL, and if it threatens to come inland from the BKL, a sand nourishment is carried out.

Definition of the instantaneous coastline

[edit]

The problem with the low water line mentioned in the 1990 Coastal Memorandum is that the height of the average low tide is well defined, but the position in the horizontal direction is not. See the attached figure, here the beach profile crosses three times the low water line. In fact, it is also not important to maintain a line, but to maintain the amount of sand in the active beach profile. To determine this volume, two heights are used, the average low water level (glw) and the height of the dune foot (dv). The height of the dune foot is basically determined by finding the intersection of the steep slope of the dune front and of the dry beach. In general, this theoretical dune foot point will be slightly below the sand. It is very difficult to redefine the height of the dune foot every year. Some administrators define the dune foot line as a certain elevation line, on which the dune foot usually lies. In relatively unalterable coastal sections, this is an acceptable approach. The method of determining the MKL is such that it is not very sensitive to the precise choice of the value dv. The location of the dune foot is thus determined by the height above NAP (National Datum, approx. Mean Sea Level) and the distance from that elevation line to the administrative coastline (Xdv). This administrative line has no physical meaning, but is simply the basis for survey work.

The recipe for calculating the position of the MKL is:[48]

- Determine the location of the dune foot

- The height of the average low water (glw) is determined

- The height h of the dune foot above average low water is calculated

- The sand volume A is calculated; A is the volume of sand seaward of the dune foot and above the level (glw-h)

- The position of the momentary coastline (SKL) is defined in relation to the national beach pile line as: (A/2h) - Xdv

The background of this method is that the thickness of the sand layer to be taken must be a function of the measuring wave height; however, it is unknown. But because the elevation of the dune foot is also a function of the measuring wave height, the value h is a good representation of the effect of both tide and wave influences. For the determination of the beach profiles, the so-called JarKus profiles are measured along the coastline. These profiles are roughly 250 metres apart and are measured annually from around 800 meters in the sea to just behind the dunes. These measurements are available throughout the coast from 1965 onwards. From the period from about 1850 there are also profile soundings available in some places, but these are often slightly shifted compared to the jarkus rowing and are therefore more difficult to analyse. In the case of groynes, the sounding is carried out exactly in the middle between the groynes.

The Basic Coastline (BKL)

[edit]

The Basic Coastline is by definition the coastline of 1 January 1990. But of course there are no measurements made on exactly that date, moreover, there are always variations in the measurements. The BKL is therefore determined by taking the beach measurements of the approximately 10 years prior to 1990 and by determining the MKL for each of those years. These values are placed in a graph, a regression line is determined. Where this regression line cuts the date 1-1-1990 lies the basic coastline BKL. In principle, the location of the BKL is immutable. In very special cases, where the coast is substantially altered by a work, it can be decided to shift the BKL. This is not based on a technical or morphological calculation, but actually a political decision. An example of this is the Hondsbossche Zeewering, as sea dike near the village of Petten, where the BKL was actually on the toe of the dike. Due to the construction of a new artificial dune in front of this dike (the Hondsbossche Duinen), a piece of dune was added, of which the intention is to preserve it. So there is the BKL shifted seaward.

The coastline to be tested (TKL)

[edit]

Within the framework of the coastal policy is determined annually whether nourishment is required in a given coastal sector. This is done by determining the coastline (TKL) to be tested before the reference date. This is determined in the same way as the BKL, namely by a regression analysis of the MKL values of the previous years. See the attached graph. In this example, a supplementation was carried out in 1990, causing the MKL to shift far seawards. The number of years over which the regression analysis can be carried out is therefore somewhat limited. If there are too few years available, a regression line is usually adopted parallel to the previous regression line (so it is assumed that the erosion before and after supplementation is approximately the same). By the way, the first year after supplementation is often more than average due to adjustment effects. In this case, it appears that the TKL is still just satisfactory for 1995 and is no longer satisfactory for 1996. In principle, a supplement at this location would be required in the course of 1995. Now the decision to supplement does not depend on a single BKL exceedance, but only if multiple profiles are threatened to become negative. In order to assess this, coastal maps are issued annually by Rijkswaterstaat.[49] These maps indicate whether the coast is growing or eroding with a dark green or light green block. A red block indicates that in that place the TKL has exceeded the BKL, and that something has to happen there. A red hatched indicator means that the TKL has exceeded the BKL, but this coastal section has an accreting tendency, so no urgent works are needed

Beach nourishment design

[edit]A beach nourishment to broaden the beach and maintain the coastline can be designed using mathematical calculation models or on the basis of beach measurements. In the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany, a nourishment design is mainly based on measurement, while mathematical models are mainly used elsewhere. A nourishment design for coastal maintenance and beach widening can be made much more reliable based on measurement data, provided that they are present. If there are no good, long-term series of measurements of the beach profile, one must make the design using calculation models. In the Netherlands, the coast has been measured annually for years (JarKus measurements) and therefore the very reliable method based on measurements is used in the Netherlands for the design of supplements to prevent erosion.

Use of measurements for nourishment design

[edit]To compensate for coastal erosion, the design of a supplementation is actually very simple, every year the same amount of sand has to be applied as erosion disappears annually. The assumption is that there is no significant change in the wave climate and the orientation of the coastline. With most nourishments, this is a correct assumption. In case of substantial changes in the coastal orientation, this method is therefore not always usable (e.g. in the design of the sand engine). In practice, the length of the nourishment must be 20-40 times the width in order to apply this method.

In short, the method consists of the following steps:[50]

- Make sure there are enough measured profiles (at least 10 years).

- Use these profiles to calculate the annual sand loss (in m3/year) for a coastal section.

- Multiply this amount by an appropriate lifetime (e.g. 5 years).

- Add a loss factor (order 40%).

- Place this amount of sand somewhere on the beach between the low water line and the dune foot.

To determine the amount of sand in the profile, the same method can be used as used for the basic Coastline. Given the fact that the instantaneous coastline has been measured for the necessary years and thus the decline of this coastline, determining the loss of sand is quite simple. Suppose the decline of the MKL is 5 m/year, then the annual sand loss is 5*(2h) m3 per year per linear meter of coastline. Here is 2h the height of the active beach profile. Along the Dutch coast, h is near Hoek van Holland in the order of 4 m, so in the above example the erosion would be 40 m3 per year per linear meter of coast. For a nourishment with a length of 4 km and a lifespan of 5 years is therefore 40*4000*5 = 80 000 m3. Because there is extra sand loss immediately after construction, a good amount is 1.4 *80000 = 112 000 m3. This is a seaward shift of 1.4*5*5= 35 m.

In the practice of beach nourishments (from 1990 onwards), this method appears to work very well. Analyses of nourishments in northern Germany also show that this is a reliable method. The starting point is that the grain size of the nourishment sand is equal to the original beach sand. If this is not the case, it must be corrected. In case of finer sand in the win area, the volume of the nourishment will need to increase.[51]

Use of mathematical models for nourishment design

[edit]Single line model

For relatively wide and short nourishment (such as the sand motor), a single-line model can be used. In this model, the coast is represented by a single line (e.g. the instantaneous coastline) and a constant profile along the entire coastline. For each profile, the orientation of the coast is given, and in each profile the sand transport is calculated by the surf induced current. If in a profile 1 the sand transport is larger than in a profile 2, there will be between profile 1 and 2 sedimentation, for details about the model.[52][53] As there is sedimentation, the coastal orientation will change, and thus also the transport of sand. This makes it possible to calculate the coastline change. A classic example is the calculation of a relatively short and wide supplementation with straight waves. The single-line model can very well predict how such supplementation can develop over time. The Unibest calculation model of Deltares is an example of a single-line model.

Field models

[edit]In highly two-dimensional situations, e.g. at a tidal inlet or the mouth of an estuary, or if the nourishment itself has a strong two-dimensional character (as with the Sand Engine), an approach with profile measurements is not possible. A single-line model is often inappropriate. In these cases, a two-dimensional sand transport model is made (usually with models such as Delft3D from Deltares in the Netherlands or Mike 21 of DHI in Denmark). In such a model, the bed of the area is introduced as a depth map. Then there is a tidal flow calculation and a wave penetration calculation. After that, the sand transport is calculated at each mesh-point and from the difference in sand transport between the different mesh-points, the sedimentation and erosion is calculated in all boxes. It can then be assessed whether a nourishment behaves as intended.[54]

The problem with this type of model is that (apart from the fairly long computation times for the computer) the results are rather sensitive to inaccuracies in the input. For example, at the edge of the model, the water levels and flow rates must be properly entered, and the wave climate must be well known. Also variations in the sand composition (grain size) have a great influence.[55]

Channel wall nourishment

[edit]At some places along the Dutch coast tidal channels are very near to the beach. In the years from around 1990 these beaches were also nourished in the classical way, but the problem was that the width of the beach is small. So the amount of sand to be placed is limited, resulting in a short lifetime of the nourishment. It was found that in such cases it is more effective to nourish the landward wall of the channel, and in some cases uses sand from the seaward side of the channel as borrow area. This is in fact moving the tidal channel further from the coastline [56](chapter 4)

Foreshore nourishments

[edit]

Instead of directly supplying the beach, it is also possible to supple the foreshore (underwater bank). The advantage of this is that the implementation of the nourishment is cheaper, and there is no direct effect of the work on the use of the beach. The sand is then transported over time by the waves from deeper water to the coast. A foreshore nourishment is calculated just like a beach nourishment, but the use of measurement data with beach profiles is then less easy, as a foreshore nourishment does not give a new beach line. Therefore, in those cases, a single-line model or a field model is usually used.[57]

In the period 1990-2020 in total 236 million cubic meters has been nourished, mainly as beach nourishment. However after 2004 more focus has been on foreshore nourishment.[56]

In 2006 the costs of some nourishment were analysed in detail. This resulted in:

| Type | Location | Cost (million €) | Volume (million m3) | cost (€/m3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Texel | 1.93 | 1.72 | 1.12 |

| B | Texel | 3.56 | 1.16 | 3.05 |

| F | Callantsoog | 2.44 | 1.90 | 1.29 |

| F | Katwijk | 2.14 | 1.21 | 1.77 |

| F | Wassenaar | 1.39 | 0.92 | 1.51 |

| B | Walcheren | 5.81 | 1.64 | 3.51 |

| B+F | Ameland | 7.50 | 2.88 | 2.61 |

F= Foreshore, B= Beach nourishment, B+F is combination; Price level 2006, excluding VAT.[58]

Hawaii

[edit]Waikiki

[edit]Hawaii planned to replenish Waikiki beach in 2010. Budgeted at $2.5 million, the project covered 1,700 feet (520 m) in an attempt to return the beach to its 1985 width. Prior opponents supported this project, because the sand was to come from nearby shoals, reopening a blocked channel and leaving the overall local sand volume unchanged, while closely matching the "new" sand to existing materials. The project planned to apply up to 24,000 cubic yards (18,000 m3) of sand from deposits located 1,500 to 3,000 feet (460 to 910 m) offshore at a depth of 10 to 20 feet (3.0 to 6.1 m). The project was larger than the prior recycling effort in 2006-07, which moved 10,000 cubic yards (7,600 m3).[59]

Maui

[edit]Maui, Hawaii illustrated the complexities of even small-scale nourishment projects. A project at Sugar Cove transported upland sand to the beach. The sand allegedly was finer than the original sand and contained excess silt that enveloped coral, smothering it and killing the small animals that lived in and around it. As in other projects, on-shore sand availability was limited, forcing consideration of more expensive offshore sources.[60]

A second project, along Stable Road, that attempted to slow rather than halt erosion, was stopped halfway toward its goal of adding 10,000 cubic yards (7,600 m3) of sand. The beaches had been retreating at a "comparatively fast rate" for half a century. The restoration was complicated by the presence of old seawalls, groins, piles of rocks and other structures.[60]

This project used sand-filled geotextile tube groins that were originally to remain in place for up to 3 years. A pipe was to transport sand from deeper water to the beach. The pipe was anchored by concrete blocks attached by fibre straps. A video showed the blocks bouncing off the coral in the current, killing whatever they touched. In places the straps broke, allowing the pipe to move across the reef, "planing it down". Bad weather exacerbated the damaging movement and killed the project.[61] The smooth, cylindrical geotextile tubes could be difficult to climb over before they were covered by sand.[60]

Supporters claimed that 2010's seasonal summer erosion was less than in prior years, although the beach was narrower after the restoration ended than in 2008. Authorities were studying whether to require the project to remove the groins immediately. Potential alternatives to geotextile tubes for moving sand included floating dredges and/or trucking in sand dredged offshore.[60]

A final consideration was sea level rise and that Maui was sinking under its own weight. Both Maui and Hawaii Island surround massive mountains (Haleakala, Mauna Loa, and Mauna Kea) and were expanding a giant dimple in the ocean floor, some 30,000 feet (9,100 m) below the mountain summits.[60]

The Outer Banks

[edit]The Outer Banks off the coast of North Carolina and southeastern Virginia include a number of towns. Five of the six town have undergone beach nourishment since 2011. The projects were as follows:

Duck, North Carolina: the beach nourishment took place in 2017 and cost an estimated $14,057,929.[62]

Southern Shores, North Carolina - the estimated costs for the Southern Shores project was approximately $950,000[63] and was completed in 2017. There is a proposed additional project to widen the beaches in 2022 with an estimated cost of between $9 million and $13.5 million.[64]

Kitty Hawk, North Carolina - the beach nourishment project in Kitty Hawk was completed in 2017 and included 3.58 miles of beaches running from the Southern Shores to Kitty Hawk and cost $18.2 million.[65]

Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina - the beach nourishment project was completed in 2017.

Nags Head, North Carolina - The town's first beach nourishment project took place in 2011 and cost between $36 million and $37 million.[66] The renourishment project in 2019 cost an estimated $25,546,711.[67]

Upcoming Projects - the towns of Duck, Southern Shores, Kitty Hawk and Kill Devil Hills have secured a contract with Coastal Protection Engineering for tentative re-nourishment projects scheduled for 2022.[citation needed]

United States

[edit]Florida - Ninety PEMs (Pressure Equalizing Modules) were installed in February 2008 at Hillsboro Beach. After 18 months the beach had expanded significantly. Most of the PEMs were removed in 2011. Beach volume expanded by 38,500 cubic yards over 3 years compared to an average annual loss of 21,000.[68]

New Jersey - Over decades, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has pour millions of cubic yards of sand slurry along the Jersey Shore.[69] Costs for the project are shared by the Army Corps of Engineers, the state, and local municipalities.[69] Although New Jersey's coastline is 1% of the U.S. coastline, from 1922 to 2022, more than $2.6 billion was expended on beach replenishment projects in the state, about 20% of the nation's total spending on beach replenishment.[69] "Dredge and fill" operations began in 1989.[70] Justifications for the projects, controversial within New Jersey, have included flood control, prevention of damage to waterfront residences, and protection of summer tourism along the shore,[69] as well as public access to beaches.[71] Critics, such as the Sierra Club and Surfrider Foundation, have argued that beach renourishment in the state is wasteful since the sand often washes away quickly; they argue for alternative policies to mitigate the effects of climate change, storm surges and rising sea levels, and argue that renourishment is effectively a subsidy for wealthy homeowners.[69][71]

Hong Kong

[edit]The beach in Gold Coast was built as an artificial beach in the 1990s with HK$60m. Sands are supplied periodically, especially after typhoons, to keep the beach viable.[72]

See also

[edit]- Beach erosion and accretion

- Integrated coastal zone management

- Coastal management, to prevent coastal erosion and creation of beach

- Coastal and oceanic landforms

- Coastal development hazards

- Coastal erosion

- Coastal geography

- Coastal engineering

- Coastal and Estuarine Research Federation (CERF)

- Sedimentation enhancing strategies

- Erosion

- Longshore drift

References

[edit]- ^ "Gold Coast Beach Nourishment Project". Queensland government. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ U.S. Supreme Court Case Stop the Beach Renourishment v. Florida Department of Environmental Protection refers to the practice as beach renourishment rather than beach nourishment.

- ^ Farley, P.P. (1923). "Coney Island public beach and boardwalk improvements. Paper 136". The Municipal Engineers Journal. 9 (4).

- ^ Dornhelm, Rachel (Summer 2004). "Beach Master". Invention & Technology Magazine. 20 (1). Retrieved 2010-07-04.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Farley, P.P. 1923. Coney Island public beach and boardwalk improvements. Paper 136. The Municipal Engineers Journal 9(4).

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ Smith, M. D.; Slott, J. M.; McNamara, D.; Murray, A. B. (2009). "Beach nourishment as a dynamic capital accumulation problem". Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 58 (1): 58–71. Bibcode:2009JEEM...58...58S. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2008.07.011. ISSN 0095-0696.

- ^ a b de Schipper, M. A.; de Vries, S.; Ruessink, G.; de Zeeuw, R. C.; Rutten, J.; van Gelder-Maas, C.; Stive, M. J. (2016). "Initial spreading of a mega feeder nourishment: Observations of the Sand Engine pilot project". Coastal Engineering. 111: 23–38. Bibcode:2016CoasE.111...23D. doi:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2015.10.011.

- ^ Central and Western Planning Areas, Gulf of Mexico Sales 147 and 150 [TX, LA, MS, AL]: Environmental Impact Statement. 1993.

- ^ Ells, Kenneth; Murray, A. Brad (2012-10-16). "Long-term, non-local coastline responses to local shoreline stabilization". Geophysical Research Letters. 39 (19): L19401. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3919401E. doi:10.1029/2012GL052627. ISSN 1944-8007.

- ^ Basco, David; Bellomo, Douglas; Hazelton, John; Jones, Bryan (1997). "The influence of seawalls on subaerial beach volumes with receding shorelines". Coastal Engineering. 30 (3–4): 203–233. Bibcode:1997CoasE..30..203B. doi:10.1016/S0378-3839(96)00044-0.

- ^ a b c d e Dean, Robert G. (2005). "Beach Nourishment: Benefits, Theory and Case Examples". Environmentally Friendly Coastal Protection. NATO Science Series. Vol. 53. SpringerLink. pp. 25–40. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3301-X_2. ISBN 1-4020-3299-4. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Brandon (December 9, 2018). "20 Beach Renourishment Pros and Cons". GreenGarage. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Beach Nourishment and Protection

- ^ Dean, Robert G.; Davis, Richard A. & Erickson, Karyn M. "Beach Nourishment - Coastal Geology - Beach Nourishment: A Guide for Local Government Officials - Beach Nourishment with Emphasis on Geological Characteristics Affecting Project Performance". NOAA Coastal Services Center. Archived from the original on 2010-05-30. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ^ Lisa Song, Al Shaw (2018-09-27). ""A Never-Ending Commitment": The High Cost of Preserving Vulnerable Beaches". ProPublica. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ a b Trembanis, Arthur C.; Pilkey, Orrin H.; Valverde, Hugo R. (2010-10-29). "Comparison of Beach Nourishment along the U.S. Atlantic, Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico, and New England Shorelines". Coastal Management. 27 (4): 329–340. doi:10.1080/089207599263730. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ Daugherty, Alex; Flechas, Joey (2017-10-31). "Replacing Miami's beach sands costs millions. Here's how Congress could make it cheaper". Miami Herald.

- ^ Timothy W., Kana; Kaczkowski, Haiqing Liu. "Myrtle Beach: A history of shore protection and beach restoration". Shore & Beach. 87 (3).

- ^ "Sandbridge Beach Replenishment". 2017. Archived from the original on 2022-07-20. Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ Pallone, Frank (2021-12-20). "Begin beach replenishment today in Deal, Allenhurst and Loch Arbour". Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ Austin Boyers, Anna (2022-02-26). "Army Corp to begin dredging throughout Carolina and Kure Beach". Retrieved 2022-07-20.

- ^ Roelse, Piet (2002). "Water en zand in balans (water and sand in balance)" (in Dutch). Rijkswaterstaat. p. 84.

- ^ a b Armstrong, Scott B.; Lazarus, Eli D.; Limber, Patrick W.; Goldstein, Evan B.; Thorpe, Curtis; Ballinger, Rhoda C. (2016-12-01). "Indications of a positive feedback between coastal development and beach nourishment". Earth's Future. 4 (12): 626–635. Bibcode:2016EaFut...4..626A. doi:10.1002/2016EF000425. ISSN 2328-4277.

- ^ "Development and Evaluation of a Sea Turtle-Deflecting Hopper Dredge Draghead". Storming Media. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Research Council (1995). Beach Nourishment and Protection (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Academy press. pp. 97–99, Table 4-2.

- ^ Waikiki replenishment[permanent dead link]

- ^ Massiani, Jérôme (2013). "How to Value the Benefits of a Recreational Area? A Cost-Benefit Analysis of the Conversion of a Brownfield to a Public Beach in Muggia (Italy)". Review of Economic Analysis. 5 (1): 86–102. hdl:10278/31672. Archived from the original on 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2014-10-25.

- ^ National Research Council, 1995. Beach Nourishment and Protection. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., 334 p. pg. 4, 94., Figure 4-6.

- ^ Bosboom, Judith; Stive, Marcel (2021). Coastal Dynamics. Delft, Netherlands: TU Delft. pp. 393–408. doi:10.5074/T.2021.001. ISBN 978-94-6366-371-7.

- ^ Bosboom, Judith; Stive, Marcel (2021). Coastal Dynamics. Delft, Netherlands: TU Delft. p. 470. doi:10.5074/T.2021.001. ISBN 978-94-6366-371-7.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Kenneth F (2016-02-15). "Passive dewatering, a soft way to extend the life of beach renourishments" (PDF). Florida Shore and Beach Preservation Association. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ Pilkey, Orrin H.; Cooper, J. Andrew G. (2012). ""Alternative" Shoreline Erosion Control Devices: A Review". Pitfalls of Shoreline Stabilization. Coastal Research Library. Vol. 3. Dordrecht: Springer Verlag. pp. 187–214. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4123-2_12. ISBN 978-94-007-4122-5.

- ^ Oh, Tae-Myoung; Dean, Robert G. (1992). "Beach face dynamics as affected by ground water table elevations". aquaticcommons.org. Retrieved 2019-05-23.

- ^ Turner, Ian L.; Leatherman, Stephen P. (1997). "Beach Dewatering as a 'Soft' Engineering Solution to Coastal Erosion: A History and Critical Review". Journal of Coastal Research. 13 (4): 1050–1063. ISSN 0749-0208. JSTOR 4298714.

- ^ Nielsen, Peter; Hibbert, Kevin; Hanslow, David J.; Davis, Greg A. (1992-01-29). "Gravity Drainage: A New Method of Beach Stabilisation Through Drainage of the Watertable". Coastal Engineering 1992. pp. 1129–1141. doi:10.1061/9780872629332.085. ISBN 9780872629332.

- ^ Bowman, Dan; Ferri, Serena; Pranzini, Enzo (2007-11-01). "Efficacy of beach dewatering — Alassio, Italy". Coastal Engineering. 54 (11): 791–800. Bibcode:2007CoasE..54..791B. doi:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2007.05.014. hdl:2158/220163. ISSN 0378-3839.

- ^ Bain, Olivier; Toulec, Renaud; Combaud, Anne; Villemagne, Guillaume; Barrier, Pascal (2016-07-01). "Five years of beach drainage survey on a macrotidal beach (Quend-Plage, northern France)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. Coastal sediment dynamics. 348 (6): 411–421. Bibcode:2016CRGeo.348..411B. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2016.04.003. ISSN 1631-0713.

- ^ Turner, Ian L.; Masselink, Gerhard (1998). "Swash infiltration-exfiltration and sediment transport". Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 103 (C13): 30813–30824. Bibcode:1998JGR...10330813T. doi:10.1029/98JC02606. ISSN 2156-2202. S2CID 140658770.

- ^ Butt, Tony; Russell, Paul; Turner, Ian (2001-01-01). "The influence of swash infiltration–exfiltration on beach face sediment transport: onshore or offshore?". Coastal Engineering. 42 (1): 35–52. Bibcode:2001CoasE..42...35B. doi:10.1016/S0378-3839(00)00046-6. ISSN 0378-3839.

- ^ Trent, Sarah (February 23, 2023). "Washaway No More: An Experimental Beach Barrier Could Be Key to Rebuilding Eroding Coastlines". Hakai Magazine. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ "Beach erosion in the tourist resort of Cancún, Mexico | Geo-Mexico, the geography of Mexico". Geo-Mexico. 6 December 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Dutch Water Facts". Holland.com. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ a b Rijkswaterstaat, RIKZ (1990). "A new coastal defence policy for the Netherlands". Rijkswaterstaat Report. 's-Gravenhage: Ministerie van Verkeer & Waterstaat.

- ^ Pilarczyk, K. W.; Zeidler, Ryszard (1996). "Dutch case studies". Offshore breakwaters and shore evolution control. London: Taylor and Francis. p. 505. ISBN 978-90-5410-627-2.

- ^ French, Peter W (2001). "The importance of dunes in the protection of the Dutch coastline". Coastal defences. London: Routledge. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-415-19845-5.

- ^ "The Netherlands". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

more than one-fourth of the total area of the country actually lies below sea level

- ^ Verhagen, H.J. (1990). "Definitie van waterkering en kustlijn: "De basiskustlijn"". Wba-N-89125(7). Delft: Rijkswatersstaat, Dienst weg- en Waterbouwkunde, nota WBA-N-S9125.

- ^ "kustlijnkaart". Rijkswaterstaat.

- ^ Verhagen, H.J. (1992). "Method for artificial beach nourishment" (pdf). Proc. International Conference on Coastal Engineering. 23rd. ICCE, Venice, Italy, 1992. American Society of Civil Engineers: 12.

- ^ Pilarczyk, K.W.; Van Overeem, J.; Bakker, W.T. (1986). "Design of Beach Nourishment Scheme". Coastal Engineering Proceedings. 20rd. ICCE, Taipei, Taiwan, 19862. 1 (20). American Society of Civil Engineers: 1456–1470. doi:10.9753/icce.v20.107.

- ^ Van der Salm, G.L.S. (2013-02-28). Coastline modelling with UNIBEST: Areas close to structures. TU Delft, MSc Thesis.

- ^ Bosboom, Judith; Stive, Marcel (2021). Coastal Dynamics. Delft, Netherlands: TU Delft. pp. 379–390. doi:10.5074/T.2021.001. ISBN 978-94-6366-371-7.

- ^ Kaji, A.O.; Luijendijk, Arjen P. (2016). "Effect of Different Forcing Processes on the Longshore Sediment Transport at the Sand Motor, The Netherlands". ICCE 2014: Proceedings of 34Th International Conference on Coastal Engineering, Seoul, Korea, 15-20 Juni 2014 (pdf). World Scientific. p. 11.

- ^ Luijendijk, Arjen P. (2017). "The initial morphological response of the Sand Engine: A process-based modelling study" (pdf). Coastal Engineering. 119. Elsevier: 14. Bibcode:2017CoasE.119....1L. doi:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2016.09.005.

- ^ a b Brand, Evelien; Ramaekers, Gemma; Lodder, Quirijn (2022). "Dutch experience with sand nourishments for dynamic coastline conservation – an operational overview". Ocean & Coastal Management. 217 106008. Bibcode:2022OCM...21706008B. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.106008. S2CID 245562221.

- ^ Van Duin, M.J.P.; Wiersma, N.R.; Walstra, D.J.R.; Van Rijn, L.C.; Stive, M.J.F. (2004). "Nourishing the shoreface: Observations and hindcasting of the Egmond case, the Netherlands". Coastal Engineering. 51 (8–9): 813–837. Bibcode:2004CoasE..51..813V. doi:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2004.07.011.

- ^ de Waard, B.J.F. Evaluatie suppleties 2006: inkoop en uitvoering kustlijnzorg suppleties (in Dutch). Rijswijk, Netherlands: Rijkswaterstaat. pp. 31 pp.

- ^ Kubota, Gary T. (June 30, 2010). "Beach to be rebuilt with recovered sand". Hawaii Star-Advertiser.

- ^ a b c d e EAGAR, HARRY (July 25, 2010). "Sand replenishment effort runs aground". Maui, Hi.: Maui News.

- ^ Mawae, Kamuela (5 June 2010). "Maui Reef Taking a Pounding From Sand Dredging Project" – via YouTube.

- ^ "Beach Nourishment FAQ's". Town of Duck, North Carolina. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "County to pay up to $500K for Southern Shores nourishment". The Outer Banks Voice. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Widening Southern Shores beach to cost at least $9 million". The Outer Banks Voice. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Outer Banks Beach Nourishment 2017 - OBX Beach Access..." OBX Beach Access. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "2011 Nourishment". Town Of Nags Head. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "Financing | Nags Head, NC". Town Of Nags Head. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ Christensen, Kenneth W.; Nettles, Sandy; Gable, Frank J. (February 6, 2015). "Passive Dewatering - A soft way to extend the life of beach nourishments" (PDF). fsbpa.com. Retrieved 2019-11-16.

- ^ a b c d e Steven Rodas, Jersey Shore: The disappearing beach, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com (June 22, 2023).

- ^ Dan Radel, 'No end in sight': Coalition argues $1.5B in NJ beach replenishment has been a waste, Asbury Park Press (October 8, 2021).

- ^ a b Steve Strunsky, Beach replenishment hurts the environment, subsidizes wealthy homeowners, group argues, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com (October 7, 2021).

- ^ "Sun特搜:泳灘「愚公移沙」康文署倒錢落海 - 太陽報". the-sun.on.cc.

External links

[edit]- Beach nourishment /NOAA and NOS / Main Page

- Beach Nourishment with Emphasis on Geological Characteristics Affecting Project Performance

- ARGUS Beach Nourishment Monitoring Program at the University of New South Wales

- USGS assessments and mapping of sand and gravel resources in U.S. offshore environments

- Beach nourishment, Coastal Care.org

- "BBC - GCSE Bitesize: Management strategies". Retrieved 2017-02-21.

Beach nourishment

View on GrokipediaBeach nourishment is the artificial addition of sediment, primarily sand, to eroding shorelines to counteract long-term sediment deficits caused by waves, currents, and storms, thereby restoring beach width and elevation.[1][2]

The process typically involves dredging sand from offshore borrow areas or inland sources, transporting it via pipelines or barges, and depositing it directly on the beach or nearshore to mimic natural profiles and provide a buffer against coastal hazards.[3]

Commonly employed in developed coastal regions like the United States Eastern Seaboard and the Netherlands, it aims to protect infrastructure, reduce flood risks, and preserve recreational beaches, with projects often funded publicly despite high recurring expenses.[4][5]

Empirical studies indicate short-term efficacy in dissipating wave energy and averting erosion damage, but sediment dispersal necessitates renourishment every 3 to 10 years on average, escalating costs that can reach tens of millions per project while questioning long-term viability amid sea-level rise.[6][7]

Environmental effects include burial and displacement of benthic organisms during placement and potential smothering of nearshore habitats from dredging, though recovery often occurs within months to years; however, cumulative impacts on species like sea turtles and forage fish warrant scrutiny in project designs.[8][9]

Critiques highlight that nourishment addresses symptoms of erosion rather than root causes like sediment starvation from dams or jetties, potentially fostering dependency on interventions that may prove fiscally burdensome as climate-driven changes intensify coastal retreat.[10][11]

Definition and Principles

Definition and objectives

Beach nourishment constitutes the artificial placement of sediment, typically sand, onto eroded beaches or adjacent nearshore zones to restore protective berms and dunes, thereby mitigating shoreline retreat without reliance on hardened structures such as seawalls.[1] This intervention addresses deficits in the coastal sediment budget by introducing compatible material sourced primarily from offshore dredging or upland deposits, enabling the shoreline to advance seaward and rebuild natural dissipative profiles that absorb wave energy.[2] The process differs fundamentally from beach scraping, which involves only the mechanical redistribution of existing sand from submerged or lower beach areas to the upper berm, yielding no net volumetric gain and thus providing only temporary aesthetic or minor stabilization effects.[12][13] The primary objectives center on enhancing the beach's capacity to buffer against storm surges and everyday wave action, preserving recreational usability, and protecting upland infrastructure like buildings and roads from inundation and erosion.[14] By widening the dry beach—often by 30 to 100 meters or more depending on project scale and local morphology—nourishment restores a functional sediment reservoir that supports dune accretion and long-term coastal resilience, grounded in the principle of equilibrating the littoral system's sand transport imbalances.[15][16] This approach prioritizes soft engineering to mimic natural accretion processes, avoiding the ecological disruptions and downdrift erosion often associated with rigid defenses.[1]Coastal sediment dynamics

Coastal sediment dynamics are governed by wave-induced transport processes that redistribute sand along and across shorelines, often resulting in localized erosion where supply deficits occur. Longshore currents, generated by waves approaching the shore at oblique angles, drive littoral drift, the primary mechanism for parallel-to-shore sediment movement. These currents arise from wave refraction and breaking, which impart shear stresses on the seabed, mobilizing sand grains in the direction of net wave approach. Empirical field measurements indicate longshore transport rates can reach thousands of cubic meters per year on exposed coasts, with direction reversals during seasonal wave shifts leading to alternating erosion and accretion zones.[17][18] Cross-shore transport, involving onshore migration during swash and offshore return via undertow or rip currents, responds to gradients in wave energy and bed slope, typically resulting in net seaward losses during storms that exceed natural supply from rivers or adjacent cells.[19] Wave refraction plays a causal role in modulating these transports by bending wave crests toward shallower bathymetry, concentrating energy in embayments and dispersing it around headlands, thereby altering local current velocities and sediment flux directions. This refraction-induced variability in wave orthogonals creates zones of convergence, where heightened energy promotes erosion, and divergence, fostering deposition, as confirmed by numerical models calibrated against field data from high-energy coasts. Local bathymetric features, such as submerged shoals or channels, further refract waves and steer currents, dominating spatial patterns of transport over broader oceanographic forcings; for instance, nearshore sand waves can amplify longshore gradients by 20-50% in wave height. Wave energy, quantified via parameters like significant wave height and period, sets the transport capacity, with empirical formulas like the CERC equation linking it directly to breaker power dissipation.[20][21] Beaches tend toward dynamic equilibrium profiles shaped by these processes, as hypothesized by Dean in 1977, where the submerged slope follows a power-law form , with as water depth, as offshore distance, and scaling with sediment fall velocity to ensure uniform wave energy dissipation per unit volume across the profile. This form arises from first-principles balance between breaking wave turbulence eroding the bed and gravitational settling rebuilding it, validated by wave tank experiments showing profiles self-adjust to incident wave conditions within hours to days, independent of initial shape. Field observations on sandy coasts corroborate this, with deviations from equilibrium—such as post-storm flattening—driving compensatory onshore transport until stability is restored, underscoring why persistent imbalances from interrupted drift cause chronic recession without sediment replenishment. Sea level rise and storm cycles amplify disequilibrium by shifting the profile seaward or intensifying energy fluxes, but empirical data emphasize that site-specific wave energy and bathymetry dictate baseline erosion rates, with nourishment required to reestablish the dissipative balance for resilience.[22][23][24]Historical Development

Pre-20th century practices

Early coastal management efforts prior to the 20th century focused on rudimentary stabilization techniques rather than large-scale sediment importation, recognizing erosion as a threat to settlements and agriculture through localized interventions that promoted natural sediment accumulation. In medieval Europe, particularly in regions like Zeeland in the Netherlands, legal measures from the 13th century onward prohibited the removal of dune vegetation and grazing on foredunes to prevent sand drift inland, effectively stabilizing beaches by allowing wind-blown sand to accrete and build protective barriers.[25] These practices, enforced by local ordinances, demonstrated an empirical understanding of sediment dynamics, where vegetation such as marram grass trapped aeolian sand, augmenting dune volumes without mechanical addition.[26] By the 17th and 18th centuries, some European coastal areas initiated primitive forms of artificial nourishment, involving manual or small-scale dredging of offshore sand for beach and dune replenishment to counter erosion exacerbated by storms and human activities like deforestation. In the Netherlands, along eroding stretches such as Delfland, communities responded to dune breaches by supplementing natural processes with relocated sand, though efforts remained ad hoc and limited by lacking dredging technology./79/68982/Panorama-of-the-History-of-Coastal-Protection) Similarly, Italian coastal documents from this period reference early sediment supplementation to maintain protective beaches, marking a shift toward human intervention beyond mere stabilization.[27] These interventions yielded temporary accretion but were constrained to small volumes, often tens to hundreds of cubic meters, serving as proof-of-concept for managing erosion without hard structures like seawalls. In the 19th-century United States, harbor jetties constructed post-1870s, such as those at East Coast ports, interrupted longshore sediment transport, inducing downdrift beach loss that prompted initial localized responses including manual sand relocation via carts or barges to eroded sections. However, these efforts were sporadic and small-scale, typically involving nearby borrow sources rather than systematic dredging, reflecting technological limits and a focus on immediate threat mitigation over long-term nourishment. Overall, pre-20th century practices underscored causal links between vegetation loss, sediment deficit, and erosion, establishing foundational principles for later engineered approaches while achieving only transient gains due to manual methods and variable natural forcing.[26]20th century expansion

The institutionalization of beach nourishment accelerated in the early 20th century with initial pilot projects in the United States, such as the filling at Coney Island, New York, in 1922–1923, which marked one of the first documented efforts to replace eroded sediment using dredged material.[28] The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began formal involvement through the establishment of the Beach Erosion Board in 1930, conducting studies and authorizing initial shore protection works under Public Law 71-520.[29] By the 1950s, post-World War II advancements in hydraulic dredging technology, including trailing suction hopper dredgers, enabled the efficient extraction and placement of larger sediment volumes, facilitating projects like the Harrison County, Mississippi, initiative in 1952, which protected 24 miles of shoreline.[29][30] In 1956, Congress passed Public Law 84-826, explicitly authorizing USACE to undertake beach nourishment for shoreline protection, including periodic maintenance, shifting from ad hoc responses to systematic federal programs.[31] This legislation supported the initiation of multiple projects in the late 1950s, with 18 efforts underway by 1958 protecting approximately 35 miles of coast at a cost of $36.9 million.[29] By the 1960s, nourishment had scaled to annual or biennial cycles in high-erosion areas, with early monitoring indicating renourishment intervals of 5–10 years depending on local sediment dynamics and storm frequency.[32] Hopper dredgers proved pivotal, allowing the transport of millions of cubic yards of sand from offshore sources to beaches, as demonstrated in projects like those in Palm Beach County, Florida, authorized in the early 1960s.[29][33] European adoption paralleled U.S. developments, particularly in the Netherlands following the devastating 1953 North Sea flood, which prompted heightened coastal defenses under the Delta Law and a transition from hard structures like dikes and groynes—dominant until the 1950s—to sediment-based nourishment strategies emphasizing large-volume placements.[34][35] Post-1953 reforms integrated beach and dune nourishment into national policy, with initial applications focusing on volume-driven accretion to counteract erosion, supported by similar dredging technologies.[36] These efforts institutionalized nourishment as a proactive measure against sea-level pressures and storms, with early projects demonstrating the feasibility of periodic replenishments to maintain coastal profiles over multi-year intervals.[32]Post-2000 innovations and scale-up

Since the early 2000s, beach nourishment practices have integrated geographic information systems (GIS) and advanced numerical models to enhance precision in sediment placement and predict long-term shoreline evolution, allowing for site-specific adaptations that account for wave dynamics and sediment transport.[37] These tools facilitate empirical refinements, such as optimizing dune profiles and nearshore berms to improve resilience against storms and gradual sea-level rise, with data-driven simulations reducing renourishment frequency in monitored U.S. projects.[38] The 2012 Hurricane Sandy catalyzed a surge in U.S. federal funding, allocating over $5 billion through the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for coastal restoration, including expansive nourishment efforts that replenished dunes and beaches along the Northeast, demonstrating reduced erosion post-storm compared to unnourished segments.[39] A landmark innovation emerged in the Netherlands with the 2011 Sand Engine mega-nourishment, which deposited 21.5 million cubic meters of sand in a concentrated offshore hook to leverage natural currents for broad dispersal, sustaining 20 kilometers of coastline over multiple years and serving as a prototype for "building with nature" strategies amid accelerating erosion.[40] [41] Scale-up has intensified globally, with the Netherlands maintaining annual nourishment volumes of approximately 12 million cubic meters to counteract baseline retreat, while U.S. East Coast initiatives have escalated to counter erosion rates averaging 1-2 meters per year in vulnerable areas.[42] Recent 2025 projects in Florida, including renourishment at Captiva Island and Mexico Beach, have incorporated adaptive profiling to achieve seaward shoreline advancement, as evidenced by American Geophysical Union modeling showing emergent progradation under frequent, coordinated replenishment regimes.[43] [44] [38] These efforts highlight nourishment's capacity for dynamic equilibrium, though sustained efficacy depends on sourcing compatible sediments and monitoring cross-shore redistribution to avoid downstream deficits.[45]Causes of Beach Erosion

Natural processes

Beach erosion arises from geophysical forces including wave refraction, breaking, and associated currents that mobilize and redistribute sediment. As waves approach shore at an angle, they refract, concentrating energy on the beach face where breaking dissipates kinetic energy, transporting sand offshore via undertow or suspending it for longshore movement.[46] In equilibrium profiles, this process maintains dynamic balance, but imbalances in energy flux lead to net sediment loss, with beaches functioning as transient depositional features subject to constant reconfiguration.[47] Storm events amplify erosion through elevated wave heights and durations, which exceed typical dissipative capacities, scouring berms and transporting material to deeper waters or offshore bars. High-energy storm waves suspend and move greater sediment volumes than fair-weather conditions, often eroding seasonal berms and contributing to annual shoreline retreat in exposed coasts.[48] [49] Prolonged storms allow more time for wave attack, exacerbating losses compared to brief events.[49] Longshore sediment transport deficits occur when wave-driven currents carry material away faster than replenishment from updrift sources, resulting in localized erosion at drift-divergent points like headlands.[48] Natural variability in wave direction and climate patterns, such as multi-annual shifts, further modulates these deficits, driving episodic retreat.[50] Geological subsidence lowers land relative to sea level, enhancing wave reach and erosion potential, particularly in tectonically active margins like the U.S. West Coast.[51] Tidal ranges influence erosion by altering water depths and wave run-up extents, with macro-tidal regimes increasing inundation frequency and sediment remobilization during high tides coinciding with storms.[52] United States Geological Survey assessments confirm pre-anthropogenic shoreline variability, with natural erosion rates averaging 0.2 meters per year in regions like Southern California, underscoring beaches' inherent dynamism independent of development.[53]Human-induced acceleration

Human infrastructure, including dams constructed since the early 1900s, has intercepted substantial fluvial sediment en route to U.S. coasts, trapping 50-90% of natural sand loads in many river basins and reducing delivery by billions of metric tons overall.[54][55] For instance, in California, pre-dam annual sand flux to beaches exceeded 10 million cubic meters, now diminished to roughly 7.7 million cubic meters due to impoundment, creating chronic downstream starvation that outpaces natural replenishment.[56] This causal interruption—rooted in water management for flood control, hydropower, and irrigation—alters littoral budgets fundamentally, as rivers historically supplied the bulk of coarse sediments sustaining barrier islands and spits. Jetties at tidal inlets, erected primarily for navigation stability, further accelerate downdrift erosion by blocking longshore drift, with impounded sand accumulating updrift while beaches erode at rates exceeding 1-2 meters per year in affected zones.[57] In the U.S., such structures have documented post-construction losses across the majority of stabilized inlets—estimated at over 70%—as dredging for channels removes additional littoral material without adequate bypassing, disrupting equilibrium profiles and amplifying recession beyond baseline variability.[58][59] Channelization of rivers and estuaries compounds this by confining flows, minimizing bank erosion and meander cutoffs that naturally liberate sediments, thereby halving or more the episodic inputs critical for coastal maintenance in engineered watersheds.[60][61] Regulatory constraints, such as stringent permitting under environmental statutes, hinder sediment reuse from navigation dredging or dam releases, often prioritizing habitat preservation over littoral restoration and thus perpetuating deficits despite technologic feasibility for bypassing.[62] Site-specific assessments reveal these anthropogenic factors dominate acceleration, with sea level rise—rising 8-9 inches globally since 1880 per NOAA records—accounting for a minority share (roughly 20-30% in modeled attributions) compared to infrastructure's direct interception of supply chains.[63][64] Empirical data from USGS and peer-reviewed analyses underscore that while relative sea level trends contribute via inundation and wave-base shifts, localized engineering legacies explain the outsized erosion spikes observed since mid-20th century developments.[61][65]Implementation Techniques

Sand sourcing and compatibility

Offshore dredging constitutes the primary method for sand sourcing in beach nourishment, favored for extracting sediments that closely resemble native beach material in grain size distribution and mineral composition, thereby facilitating seamless integration into the coastal sediment budget.[66][67] Borrow sites are selected to yield sands with median grain diameters typically between 0.2 and 0.5 mm, aligning with prevalent U.S. East and Gulf Coast beach profiles to support stable longshore transport.[68] This preference stems from empirical observations that native-like sands maintain beach equilibrium without inducing excessive offshore losses or downdrift scour.[69] Finer-grained imports, often exceeding 10-20% deviation in distribution from native sands, are generally eschewed due to their susceptibility to rapid dispersion via wave-induced suspension, which accelerates renourishment needs and disrupts adjacent shorelines.[70] Compatibility evaluations prioritize mineralogical matching, with abrasion-resistant silicate sands preferred over carbonates to mitigate breakdown and ensure durability against hydrodynamic forces.[71] Upland mining offers a supplementary sourcing option, particularly where offshore volumes are limited, but demands stringent traceability protocols to verify sediment provenance and preclude contaminants.[72] Sieve analysis serves as the core empirical test, quantifying grain size statistics—mean diameter, sorting, and skewness—to achieve 80-90% overlap with native distributions, thus averting differential erosion rates that could exacerbate downdrift deficits.[73][74] Field-calibrated borrow areas, validated through pre-project sampling, underpin these assessments to forecast performance without reliance on unverified imports.[75] Project-scale volumes commonly span 1 to 5 million cubic meters, calibrated to site-specific erosion rates; for instance, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers initiatives in 2023-2025, such as Miami Beach renourishment, deployed around 640,000 cubic meters from vetted offshore sites to restore 11,400 linear feet of shoreline.[76][77]Placement and profiling methods

Beach nourishment placement typically involves depositing sand via submerged pipelines from trailing suction hopper dredgers or by trucks to construct supra-tidal berms and extend subaqueous profiles, with the design optimized to achieve dynamic equilibrium under local wave and current regimes.[78][32] Dredged sand slurry is pumped ashore at high volumes, often thousands of cubic meters per hour, and discharged through outlets positioned along the beach to distribute material evenly before shaping.[79] Post-deposition, bulldozers redistribute the sand to form a berm crest and slope the profile to approximate the equilibrium form, minimizing rapid offshore losses during wave reworking.[78] Profile nourishment targets subtidal extensions to enhance nearshore bar formation and sediment transport onshore, contrasting with beach fill that prioritizes immediate dry-beach widening for erosion buffering and recreation; hybrid approaches, placing sand across both zones, are prevalent to secure 20-50 meter shoreline gains with reduced total volume requirements.[80][81] These methods leverage natural profile equilibration, where initial steep slopes flatten over weeks to months under storm waves, retaining the bulk of placed sediment within the active coastal zone.[78] Construction often occurs in winter to limit seasonal disruptions, allowing initial storm events to accelerate profile adjustment; empirical data indicate that nourished beaches can retain over two-thirds of the placed volume immediately post-storm, as the designed template resists wholesale erosion.[49][67]Monitoring protocols