Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Concentrated solar power

View on WikipediaThis article contains promotional content. (May 2025) |

Concentrated solar power (CSP, also known as concentrating solar power, concentrated solar thermal) systems generate solar power by using mirrors or lenses to concentrate a large area of sunlight into a receiver.[1] Electricity is generated when the concentrated light is converted to heat (solar thermal energy), which drives a heat engine (usually a steam turbine) connected to an electrical power generator[2][3][4] or powers a thermochemical reaction.[5][6][7]

As of 2021, global installed capacity of concentrated solar power stood at 6.8 GW.[8] As of 2023, the total was 8.1 GW, with the inclusion of three new CSP projects in construction in China[9] and in Dubai in the UAE.[9] The U.S.-based National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), which maintains a global database of CSP plants, counts 6.6 GW of operational capacity and another 1.5 GW under construction.[10] By comparison, solar power reached 1 TW of global capacity in 2022, of which the overwhelming majority was photovoltaic.

Comparison between CSP and other electricity sources

[edit]As a thermal energy generating power station, CSP has more in common with thermal power stations such as coal, gas, or geothermal. A CSP plant can incorporate thermal energy storage, which stores energy either in the form of sensible heat or as latent heat (for example, using molten salt), which enables these plants to continue supplying electricity whenever it is needed, day or night.[11] This makes CSP a dispatchable form of solar. Dispatchable renewable energy is particularly valuable in places where there is already a high penetration of photovoltaics (PV), such as California,[12] because demand for electric power peaks near sunset just as PV capacity ramps down (a phenomenon referred to as duck curve).[13]

CSP is often compared to photovoltaic solar (PV) since they both use solar energy. While solar PV experienced huge growth during the 2010s due to falling prices,[14][15] solar CSP growth has been slow due to technical difficulties and high prices. In 2017, CSP represented less than 2% of worldwide installed capacity of solar electricity plants.[16] However, CSP can more easily store energy during the night, making it more competitive with dispatchable generators and baseload plants.[17][18][19][20]

The DEWA project in Dubai, under construction in 2019, held the world record for lowest CSP price in 2017 at US$73 per MWh[21] for its 700 MW combined trough and tower project: 600 MW of trough, 100 MW of tower with 15 hours of thermal energy storage daily. Base-load CSP tariff in the extremely dry Atacama region of Chile reached below $50/MWh in 2017 auctions.[22][23]

History

[edit]

A legend has it that Archimedes used a "burning glass" to concentrate sunlight on the invading Roman fleet and repel them from Syracuse. In 1973 a Greek scientist, Dr. Ioannis Sakkas, curious about whether Archimedes could really have destroyed the Roman fleet in 212 BC, lined up nearly 60 Greek sailors, each holding an oblong mirror tipped to catch the sun's rays and direct them at a tar-covered plywood silhouette 49 m (160 ft) away. The ship caught fire after a few minutes; however, historians continue to doubt the Archimedes story.[24]

In 1866, Auguste Mouchout used a parabolic trough to produce steam for the first solar steam engine. The first patent for a solar collector was obtained by the Italian Alessandro Battaglia in Genoa, Italy, in 1886. Over the following years, invеntors such as John Ericsson and Frank Shuman developed concentrating solar-powered dеvices for irrigation, refrigеration, and locomоtion. In 1913 Shuman finished a 55 horsepower (41 kW) parabolic solar thermal energy station in Maadi, Egypt for irrigation.[25][26][27][28] The first solar-power system using a mirror dish was built by Dr. R.H. Goddard, who was already well known for his research on liquid-fueled rockets and wrote an article in 1929 in which he asserted that all the previous obstacles had been addressed.[29]

Professor Giovanni Francia (1911–1980) designed and built the first concentrated-solar plant, which entered into operation in Sant'Ilario, near Genoa, Italy in 1968. This plant had the architecture of today's power tower plants, with a solar receiver in the center of a field of solar collectors. The plant was able to produce 1 MW with superheated steam at 100 bar and 500 °C.[30] The 10 MW Solar One power tower was developed in Southern California in 1981. Solar One was converted into Solar Two in 1995, implementing a new design with a molten salt mixture (60% sodium nitrate, 40% potassium nitrate) as the receiver working fluid and as a storage medium. The molten salt approach proved effective, and Solar Two operated successfully until it was decommissioned in 1999.[31] The parabolic-trough technology of the nearby Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS), begun in 1984, was more workable. The 354 MW SEGS was the largest solar power plant in the world until 2014.

No commercial concentrated solar was constructed from 1990, when SEGS was completed, until 2006, when the Compact linear Fresnel reflector system at Liddell Power Station in Australia was built. Few other plants were built with this design, although the 5 MW Kimberlina Solar Thermal Energy Plant opened in 2009.

In 2007, 75 MW Nevada Solar One was built, a trough design and the first large plant since SEGS. Between 2010 and 2013, Spain built over 40 parabolic trough systems, size constrained at no more than 50 MW by the support scheme. Where not bound in other countries, the manufacturers have adopted up to 200 MW size for a single unit,[32] with a cost soft point around 125 MW for a single unit.

Due to the success of Solar Two, a commercial power plant, called Solar Tres Power Tower, was built in Spain in 2011, later renamed Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant. Gemasolar's results paved the way for further plants of its type. Ivanpah Solar Power Facility was constructed at the same time but without thermal storage, using natural gas to preheat water each morning.

Most concentrated solar power plants use the parabolic trough design, instead of the power tower or Fresnel systems. There have also been variations of parabolic trough systems like the integrated solar combined cycle (ISCC) which combines troughs and conventional fossil fuel heat systems.

CSP was originally treated as a competitor to photovoltaics, and Ivanpah was built without energy storage, although Solar Two included several hours of thermal storage. By 2015, prices for photovoltaic plants had fallen and PV commercial power was selling for 1⁄3 of contemporary CSP contracts.[33][34] However, increasingly, CSP was being bid with 3 to 12 hours of thermal energy storage, making CSP a dispatchable form of solar energy.[35] As such, it is increasingly seen as competing with natural gas and PV with batteries for flexible, dispatchable power.

Current technology

[edit]CSP is used to produce electricity (sometimes called solar thermoelectricity, usually generated through steam). Concentrated solar technology systems use mirrors or lenses with tracking systems to focus a large area of sunlight onto a small area. The concentrated light is then used as heat or as a heat source for a conventional power plant (solar thermoelectricity). The solar concentrators used in CSP systems can often also be used to provide industrial process heating or cooling, such as in solar air conditioning.

Concentrating technologies exist in four optical types, namely parabolic trough, dish, concentrating linear Fresnel reflector, and solar power tower.[36] Parabolic trough and concentrating linear Fresnel reflectors are classified as linear focus collector types, while dish and solar tower are point focus types. Linear focus collectors achieve medium concentration factors (50 suns and over), and point focus collectors achieve high concentration factors (over 500 suns). Although simple, these solar concentrators are quite far from the theoretical maximum concentration.[37][38] For example, the parabolic-trough concentration gives about 1⁄3 of the theoretical maximum for the design acceptance angle, that is, for the same overall tolerances for the system. Approaching the theoretical maximum may be achieved by using more elaborate concentrators based on nonimaging optics.[37][38][39]

Different types of concentrators produce different peak temperatures and correspondingly varying thermodynamic efficiencies due to differences in the way that they track the sun and focus light. New innovations in CSP technology are leading systems to become more and more cost-effective.[40][41]

In 2023, Australia's national science agency CSIRO tested a CSP arrangement in which tiny ceramic particles fall through the beam of concentrated solar energy, the ceramic particles capable of storing a greater amount of heat than molten salt, while not requiring a container that would diminish heat transfer.[42]

Parabolic trough

[edit]

A parabolic trough consists of a linear parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned along the reflector's focal line. The receiver is a tube positioned at the longitudinal focal line of the parabolic mirror and filled with a working fluid. The reflector follows the sun during the daylight hours by tracking along a single axis. A working fluid (e.g. molten salt[43]) is heated to 150–350 °C (302–662 °F) as it flows through the receiver and is then used as a heat source for a power generation system.[44] Trough systems are the most developed CSP technology. The Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS) plants in California, some of the longest-running in the world until their 2021 closure;[45] Acciona's Nevada Solar One near Boulder City, Nevada;[45] and Andasol, Europe's first commercial parabolic trough plant are representative,[46] along with Plataforma Solar de Almería's SSPS-DCS test facilities in Spain.[47]

Enclosed trough

[edit]The design encapsulates the solar thermal system within a greenhouse-like glasshouse. The glasshouse creates a protected environment to withstand the elements that can negatively impact reliability and efficiency of the solar thermal system.[48] Lightweight curved solar-reflecting mirrors are suspended from the ceiling of the glasshouse by wires. A single-axis tracking system positions the mirrors to retrieve the optimal amount of sunlight. The mirrors concentrate the sunlight and focus it on a network of stationary steel pipes, also suspended from the glasshouse structure.[49] Water is carried throughout the length of the pipe, which is boiled to generate steam when intense solar radiation is applied. Sheltering the mirrors from the wind allows them to achieve higher temperature rates and prevents dust from building up on the mirrors.[48]

GlassPoint Solar, the company that created the Enclosed Trough design, states its technology can produce heat for Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) for about $5 per 290 kWh (1,000,000 BTU) in sunny regions, compared to between $10 and $12 for other conventional solar thermal technologies.[50]

Solar power tower

[edit]

A solar power tower consists of an array of dual-axis tracking reflectors (heliostats) that concentrate sunlight on a central receiver atop a tower; the receiver contains a heat-transfer fluid, which can consist of water-steam or molten salt. Optically a solar power tower is the same as a circular Fresnel reflector. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to 500–1000 °C (773–1,273 K or 932–1,832 °F) and then used as a heat source for a power generation or energy storage system.[44] An advantage of the solar tower is the reflectors can be adjusted instead of the whole tower. Power-tower development is less advanced than trough systems, but they offer higher efficiency and better energy storage capability. Beam down tower application is also feasible with heliostats to heat the working fluid.[51] CSP with dual towers are also used to enhance the conversion efficiency by nearly 24%.[52]

The Solar Two in Daggett, California and the CESA-1 in Plataforma Solar de Almeria Almeria, Spain, are the most representative demonstration plants. The Planta Solar 10 (PS10) in Sanlucar la Mayor, Spain, is the first commercial utility-scale solar power tower in the world. The 377 MW Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, located in the Mojave Desert, was the largest CSP facility in the world, and uses three power towers.[53] Ivanpah generated only 0.652 TWh (63%) of its energy from solar means, and the other 0.388 TWh (37%) was generated by burning natural gas.[54][55][56]

Supercritical carbon dioxide can be used instead of steam as heat-transfer fluid for increased electricity production efficiency. However, because of the high temperatures in arid areas where solar power is usually located, it is impossible to cool down carbon dioxide below its critical temperature in the compressor inlet. Therefore, supercritical carbon dioxide blends with higher critical temperatures are currently in development.

Fresnel reflectors

[edit]Fresnel reflectors are made of many thin, flat mirror strips to concentrate sunlight onto tubes through which working fluid is pumped. Flat mirrors allow more reflective surface in the same amount of space than a parabolic reflector, thus capturing more of the available sunlight, and they are much cheaper than parabolic reflectors.[57] Fresnel reflectors can be used in various size CSPs.[58][59]

Fresnel reflectors are sometimes regarded as a technology with a worse output than other methods. The cost efficiency of this model is what causes some to use this instead of others with higher output ratings. Some new models of Fresnel reflectors with Ray Tracing capabilities have begun to be tested and have initially proved to yield higher output than the standard version.[60]

Dish Stirling

[edit]

A dish Stirling or dish engine system consists of a stand-alone parabolic reflector that concentrates light onto a receiver positioned at the reflector's focal point. The reflector tracks the Sun along two axes. The working fluid in the receiver is heated to 250–700 °C (482–1,292 °F) and then used by a Stirling engine to generate power.[44] Parabolic-dish systems provide high solar-to-electric efficiency (between 31% and 32%), and their modular nature provides scalability. The Stirling Energy Systems (SES), United Sun Systems (USS) and Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) dishes at UNLV, and Australian National University's Big Dish in Canberra, Australia are representative of this technology. A world record for solar to electric efficiency was set at 31.25% by SES dishes at the National Solar Thermal Test Facility (NSTTF) in New Mexico on 31 January 2008, a cold, bright day.[61] According to its developer, Ripasso Energy, a Swedish firm, in 2015 its dish Stirling system tested in the Kalahari Desert in South Africa showed 34% efficiency.[62] The SES installation in Maricopa, Phoenix, was the largest Stirling Dish power installation in the world until it was sold to United Sun Systems. Subsequently, larger parts of the installation have been moved to China to satisfy part of the large energy demand.

CSP with thermal energy storage

[edit]In a CSP plant that includes storage, the solar energy is first used to heat molten salt or synthetic oil, which is stored providing thermal/heat energy at high temperature in insulated tanks.[63][64] Later the hot molten salt (or oil) is used in a steam generator to produce steam to generate electricity by steam turbo generator as required.[65] Thus solar energy which is available in daylight only is used to generate electricity round the clock on demand as a load following power plant or solar peaker plant.[66][67] The thermal storage capacity is indicated in hours of power generation at nameplate capacity. Unlike solar PV or CSP without storage, the power generation from solar thermal storage plants is dispatchable and self-sustainable, similar to coal/gas-fired power plants, but without the pollution.[68] CSP with thermal energy storage plants can also be used as cogeneration plants to supply both electricity and process steam round the clock. As of December 2018, CSP with thermal energy storage plants' generation costs have ranged between 5 c € / kWh and 7 c € / kWh, depending on good to medium solar radiation received at a location.[69] Unlike solar PV plants, CSP with thermal energy storage can also be used economically around the clock to produce process steam, replacing polluting fossil fuels. CSP plants can also be integrated with solar PV for better synergy.[70][71][72]

CSP with thermal storage systems are also available using Brayton cycle generators with air instead of steam for generating electricity and/or steam round the clock. These CSP plants are equipped with gas turbines to generate electricity.[73] These are also small in capacity (<0.4 MW), with flexibility to install in few acres' area.[73] Waste heat from the power plant can also be used for process steam generation and HVAC needs.[74] In case land availability is not a limitation, any number of these modules can be installed, up to 1000 MW with RAMS and cost advantages since the per MW costs of these units are lower than those of larger size solar thermal stations.[75]

Centralized district heating round the clock is also feasible with concentrated solar thermal storage plants.[76]

Deployment around the world

[edit]| Country | Total | Added |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | 2,304 | 0 |

| United States | 1,480 | 0 |

| South Africa | 500 | 0 |

| Morocco | 540 | 0 |

| India | 343 | 0 |

| China | 570 | 0 |

| United Arab Emirates | 600 | 300 |

| Saudi Arabia | 50 | 0 |

| Algeria | 25 | 0 |

| Egypt | 20 | 0 |

| Italy | 13 | 0 |

| Australia | 5 | 0 |

| Thailand | 5 | 0 |

| Source: REN21 Global Status Report, 2017 and 2018[77][78][79][80] | ||

An early plant operated in Sicily at Adrano. The US deployment of CSP plants started by 1984 with the SEGS plants. The last SEGS plant was completed in 1990. From 1991 to 2005, no CSP plants were built anywhere in the world. Global installed CSP-capacity increased nearly tenfold between 2004 and 2013 and grew at an average of 50 percent per year during the last five of those years, as the number of countries with installed CSP was growing.[81]: 51 In 2013, worldwide installed capacity increased by 36% or nearly 0.9 gigawatt (GW) to more than 3.4 GW. The record for capacity installed was reached in 2014, corresponding to 925 MW; however, it was followed by a decline caused by policy changes, the 2008 financial crisis, and the rapid decrease in price of the photovoltaic cells. Nevertheless, total capacity reached 6800 MW in 2021.[8]

Spain accounted for almost one third of the world's capacity, at 2,300 MW, despite no new capacity entering commercial operation in the country since 2013.[80] The United States follows with 1,740 MW. Interest is also notable in North Africa and the Middle East, as well as China and India. There is a notable trend towards developing countries and regions with high solar radiation with several large plants under construction in 2017.

| Year | 1984 | 1985 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991-2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Installed | 14 | 60 | 200 | 80 | 0 | 1 | 74 | 55 | 179 | 307 | 629 | 803 | 872 | 925 | 420 | 266 | 101 | 740 | 566 | 38 | -39 | 199 | 300 |

| Cumulative | 14 | 74 | 274 | 354 | 354 | 355 | 429 | 484 | 663 | 969 | 1,598 | 2,553 | 3,425 | 4,335 | 4,705 | 4,971 | 5,072 | 5,812 | 6,378 | 6,416 | 6,377 | 6,576 | 6,876[77] |

| Sources: REN21[78][82]: 146 [81] : 51 [79] · CSP-world.com[83] · IRENA[84] · HeliosCSP[80] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

The global market was initially dominated by parabolic-trough plants, which accounted for 90% of CSP plants at one point.[85]

Since about 2010, central power tower CSP has been favored in new plants due to its higher temperature operation – up to 565 °C (1,049 °F) vs. trough's maximum of 400 °C (752 °F) – which promises greater efficiency.

Among the larger CSP projects are the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility (392 MW) in the United States, which uses solar power tower technology without thermal energy storage, and the Ouarzazate Solar Power Station in Morocco,[86] which combines trough and tower technologies for a total of 510 MW with several hours of energy storage.

Cost

[edit]As early as 2011, the rapid decline of the price of photovoltaic systems led to projections that CSP would no longer be economically viable.[87] As of 2020, the least expensive utility-scale concentrated solar power stations in the United States and worldwide were five times more expensive than utility-scale photovoltaic power stations, with a projected minimum price of 7 cents per kilowatt-hour for the most advanced CSP stations against record lows of 1.32 cents per kWh[88] for utility-scale PV.[89] This five-fold price difference has been maintained since 2018.[90] Some hybrid PV-CSP plants in China have sought to operate profitably on the regional coal tariff of 5 US cents per kWh in 2021.[91]

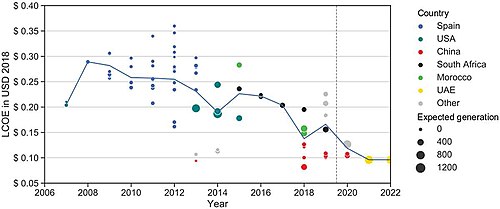

Even though overall deployment of CSP remains limited in the early 2020s, the levelized cost of power from commercial scale plants has decreased since the 2010s. With a learning rate estimated at around 20% cost reduction of every doubling in capacity,[92] the costs were approaching the upper end of the fossil fuel cost range at the beginning of the 2020s, driven by support schemes in several countries, including Spain, the US, Morocco, South Africa, China, and the UAE.

Energy storage

[edit]Some researchers expect CSP in combination with Thermal Energy Storage (TES) to become cheaper than PV with lithium batteries for storage durations above 4 hours per day,[93][94] while others such as NREL expects that by 2030 PV with 10-hour storage lithium batteries will cost the same as PV with 4-hour storage used to cost in 2020, leaving CSP no cost advantage when it comes to energy storage.[95] Regardless of these cost projections, energy storage solutions remain essential, as they improve stability and reliability by reducing the impact of renewable intermittency and power factor mismatch.[96]

Efficiency

[edit]The efficiency of a concentrating solar power system depends on the technology used to convert the solar power to electrical energy, the operating temperature of the receiver and the heat rejection, thermal losses in the system, and the presence or absence of other system losses; in addition to the conversion efficiency, the optical system which concentrates the sunlight will also add additional losses.

Real-world systems claim a maximum thermal to electrical conversion efficiency of 23-35% for "power tower" type systems, operating at temperatures from 250 to 565 °C, with the higher efficiency number assuming a combined cycle turbine. Dish Stirling systems, operating at temperatures of 550-750 °C, claim an efficiency of about 30%,[97] with the record solar-to-grid conversion efficiency of 31.25%, "the highest recorded efficiency for any field solar technology" set by Sandia in 2008,[98] and a slightly slightly higher record of 31.4% solar-to-electric system efficiency reported by the U.S. Department of Energy.[99]

Due to variation in sun incidence during the day, the average conversion efficiency achieved is not equal to these maximum efficiencies, and the net annual solar-to-electricity efficiencies are 7-20% for pilot power tower systems, and 12-25% for demonstration-scale Stirling dish systems.[97]

Theory

[edit]The solar energy to electrical power conversion efficiency is the product of several factors: the fraction of solar energy captured (accounting for optical losses in the solar concentration system), the heating efficiency (accounting for thermal losses in the element receiving the solar energy), and the thermal conversion efficiency (the efficiency of converting heat energy to electrical power).

The maximum conversion efficiency of any thermal to electrical energy system is given by the Carnot efficiency, which represents a theoretical limit to the efficiency that can be achieved by any system, set by the laws of thermodynamics. Real-world systems do not achieve the Carnot efficiency.

The conversion efficiency of the incident solar radiation into mechanical work depends on the thermal radiation properties of the solar receiver and on the heat engine (e.g. steam turbine). Solar irradiation is first concentrated onto the receiver by an optical system and converted into heat by the solar receiver with the efficiency , and subsequently the heat is converted into mechanical energy by the heat engine with the efficiency , using Carnot's principle.[100][101] The mechanical energy is then converted into electrical energy by a generator. For a solar receiver with a mechanical converter (e.g., a turbine), the overall conversion efficiency can be defined as follows:

where represents the fraction of incident light concentrated onto the receiver, the fraction of light incident on the receiver that is converted into heat energy, the efficiency of conversion of heat energy into mechanical energy, and the efficiency of converting the mechanical energy into electrical power.

is:

-

- with , , respectively the incoming solar flux and the fluxes absorbed and lost by the system solar receiver.

The conversion efficiency is at most the Carnot efficiency, which is determined by the temperature of the receiver and the temperature of the heat rejection ("heat sink temperature") ,

The real-world thermal-conversion efficiencies of typical engines achieve 50% to at most 70% of the Carnot efficiency due to losses such as heat loss and windage in the moving parts.

Ideal case

[edit]For a solar flux (e.g. ) concentrated times with an efficiency on the system solar receiver with a collecting area and an absorptivity :

- ,

- ,

For simplicity's sake, one can assume that the losses are only radiative ones (a fair assumption for high temperatures), thus for a reradiating area A and an emissivity applying the Stefan–Boltzmann law yields:

Simplifying these equations by considering perfect optics ( = 1) and without considering the ultimate conversion step into electricity by a generator, collecting and reradiating areas equal and maximum absorptivity and emissivity ( = 1, = 1) then substituting in the first equation gives

The graph shows that the overall efficiency does not increase steadily with the receiver's temperature. Although the heat engine's efficiency (Carnot) increases with higher temperature, the receiver's efficiency does not. On the contrary, the receiver's efficiency is decreasing, as the amount of energy it cannot absorb (Qlost) grows by the fourth power as a function of temperature. Hence, there is a maximum reachable temperature. When the receiver efficiency is null (blue curve on the figure below), Tmax is:

There is a temperature Topt for which the efficiency is maximum, i.e.. when the efficiency derivative relative to the receiver temperature is null:

Consequently, this leads us to the following equation:

Solving this equation numerically allows us to obtain the optimum process temperature according to the solar concentration ratio (red curve on the figure below)

| C | 500 | 1000 | 5000 | 10000 | 45000 (max. for Earth) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tmax | 1720 | 2050 | 3060 | 3640 | 5300 |

| Topt | 970 | 1100 | 1500 | 1720 | 2310 |

Theoretical efficiencies aside, real-world experience of CSP reveals a 25%–60% shortfall in projected production, a good part of which is due to the practical Carnot cycle losses not included in the above analysis.

Incentives and markets

[edit]Spain

[edit]

In 2008, Spain launched the first commercial scale CSP market in Europe. Until 2012, solar-thermal electricity generation was initially eligible for feed-in tariff payments (art. 2 RD 661/2007) – leading to the creation of the largest CSP fleet in the world which at 2.3 GW of installed capacity contributes about 5TWh of power to the Spanish grid every year.[102] The initial requirements for plants in the FiT were:

- Systems registered in the register of systems prior to 29 September 2008: 50 MW for solar-thermal systems.

- Systems registered after 29 September 2008 (PV only).

The capacity limits for the different system types were re-defined during the review of the application conditions every quarter (art. 5 RD 1578/2008, Annex III RD 1578/2008). Prior to the end of an application period, the market caps specified for each system type are published on the website of the Ministry of Industry, Tourism and Trade (art. 5 RD 1578/2008).[103] Because of cost concerns Spain has halted acceptance of new projects for the feed-in-tariff on 27 January 2012[104][105] Already accepted projects were affected by a 6% "solar-tax" on feed-in-tariffs, effectively reducing the feed-in-tariff.[106]

In this context, the Spanish Government enacted the Royal Decree-Law 9/2013[107] in 2013, aimed at the adoption of urgent measures to guarantee the economic and financial stability of the electric system, laying the foundations of the new Law 24/2013 of the Spanish electricity sector.[108] This new retroactive legal-economic framework applied to all the renewable energy systems was developed in 2014 by the RD 413/2014,[109] which abolished the former regulatory frameworks set by the RD 661/2007 and the RD 1578/2008 and defined a new remuneration scheme for these assets.

After a lost decade for CSP in Europe, Spain announced in its National Energy and Climate Plan with the intention of adding 5GW of CSP capacity between 2021 and 2030.[110] Towards this end bi-annual auctions of 200 MW of CSP capacity starting in October 2022 are expected, but details are not yet known.[111]

Australia

[edit]Several CSP dishes have been set up in remote Aboriginal settlements in the Northern Territory: Hermannsburg, Yuendumu and Lajamanu.

So far no commercial scale CSP project has been commissioned in Australia, but several projects have been suggested. In 2017, now-bankrupt American CSP developer SolarReserve was awarded a PPA to realize the 150 MW Aurora Solar Thermal Power Project in South Australia at a record low rate of just AUD$ 0.08/kWh, or close to USD$ 0.06/kWh.[112] However, the company failed to secure financing, and the project was cancelled. Another application for CSP in Australia are mines that need 24/7 electricity but often have no grid connection. Vast Solar, a startup company aiming to commercialize a novel modular third generation CSP design,[113][114] was looking to start construction of a 50 MW combined CSP and PV facility in Mt. Isa of North-West Queensland by 2021,[115] and a 30 MW CSP system with multiple smaller solar towers near Port Augusta, with $180 million Australian Renewable Energy Agency grant plus up to $110 million of other funding after 2025.[116]

At the federal level, under the Large-scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET), in operation under the Renewable Energy Electricity Act 2000, large-scale solar thermal electricity generation from accredited RET power stations may be entitled to create large-scale generation certificates (LGCs). These certificates can then be sold and transferred to liable entities (usually electricity retailers) to meet their obligations under this tradeable certificates scheme. However, as this legislation is technology neutral in its operation, it tends to favour more established RE technologies with a lower levelised cost of generation, such as large-scale onshore wind, rather than solar thermal and CSP.[117] At state level, renewable energy feed-in laws typically are capped by maximum generation capacity in kWp, and are open only to micro or medium scale generation and in a number of instances are only open to solar photovoltaic (PV) generation. This means that larger scale CSP projects would not be eligible for payment for feed-in incentives in many of the State and Territory jurisdictions.

China

[edit]

In 2024, China is offering second generation CSP technology to compete with other on-demand electricity generation methods based on renewable or non-renewable fossil fuels without any direct or indirect subsidies.[11] In the current 14th five-year plan CSP projects are developed in several provinces alongside large GW sized solar PV and wind projects.[91][8]

In 2016, China announced its intention to build a batch of 20 technologically diverse CSP demonstration projects in the context of the 13th five-year plan, with the intention of building up an internationally competitive CSP industry.[118] Since the first plants were completed in 2018, the generated electricity from the plants with thermal storage is supported with an administratively set FiT of RMB 1.5 per kWh.[119] At the end of 2020, China operated a total of 545 MW in 12 CSP plants:[120][121] seven plants (320 MW) are molten-salt towers, another two plants (150 MW) use the proven Eurotrough 150 parabolic trough design,[122] and three plants (75 MW) use linear Fresnel collectors. Plans to build a second batch of demonstration projects were never enacted and further technology specific support for CSP in the upcoming 14th five-year plan is unknown. Federal support projects from the demonstration batch ran out at the end of 2021.[123]

India

[edit]In March 2024, SECI announced that a RfQ for 500 MW would be called in the year 2024.[124]

Solar thermal reactors

[edit]CSP has other uses than electricity. Researchers are investigating solar thermal reactors for the production of solar fuels, making solar a fully transportable form of energy in the future. These researchers use the solar heat of CSP as a catalyst for thermochemistry to break apart molecules of H2O to create hydrogen (H2) from solar energy with no carbon emissions.[125] By splitting both H2O and CO2, other much-used hydrocarbons – for example, the jet fuel used to fly commercial airplanes – could also be created with solar energy rather than from fossil fuels.[126]

Heat from the sun can be used to provide steam used to make heavy oil less viscous and easier to pump. This process is called solar thermal enhanced oil recovery. Solar power towers and parabolic troughs can be used to provide the steam, which is used directly, so no generators are required and no electricity is produced. Solar thermal enhanced oil recovery can extend the life of oilfields with very thick oil which would not otherwise be economical to pump.[1]

Carbon neutral synthetic fuel production using concentrated solar thermal energy at nearly 1500 °C temperature is technically feasible and will be commercially viable in the future if the costs of CSP plants decline.[127] Also, carbon-neutral hydrogen can be produced with solar thermal energy (CSP) using the sulfur–iodine cycle, hybrid sulfur cycle, iron oxide cycle, copper–chlorine cycle, zinc–zinc oxide cycle, cerium(IV) oxide–cerium(III) oxide cycle, or an alternative.

Gigawatt-scale solar power plants

[edit]Around the turn of the millennium up to about 2010, there have been several proposals for gigawatt-size, very-large-scale solar power plants using CSP.[128] They include the Euro-Mediterranean Desertec proposal and Project Helios in Greece (10 GW), both now canceled. A 2003 study concluded that the world could generate 2,357,840 TWh each year from very large-scale solar power plants using 1% of each of the world's deserts. Total consumption worldwide was 15,223 TWh/year[129] (in 2003). The gigawatt size projects would have been arrays of standard-sized single plants. In 2012, the BLM made available 97,921,069 acres (39,627,251 hectares) of land in the southwestern United States for solar projects, enough for between 10,000 and 20,000 GW.[130] The largest single plant in operation is the 510 MW Noor Solar Power Station. In 2022 the 700 MW CSP 4th phase of the 5GW Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Solar Park in Dubai will become the largest solar complex featuring CSP.

Suitable sites

[edit]The locations with highest direct irradiance are dry, at high altitude, and located in the tropics. These locations have a higher potential for CSP than areas with less sun.

Abandoned opencast mines, moderate hill slopes, and crater depressions may be advantageous in the case of power tower CSP, as the power tower can be located on the ground integral with the molten salt storage tank.[131][132]

Environmental effects

[edit]CSP has a number of environmental impacts, particularly by the use of water and land.[133] Water is generally used for cooling and to clean mirrors. Some projects are looking into various approaches to reduce the water and cleaning agents used, including the use of barriers, non-stick coatings on mirrors, water misting systems, and others.[134]

Water use

[edit]Concentrating solar power plants with wet-cooling systems have the highest water-consumption intensities of any conventional type of electric power plant; only fossil-fuel plants with carbon-capture and storage may have higher water intensities.[135] A 2013 study comparing various sources of electricity found that the median water consumption during operations of concentrating solar power plants with wet cooling was 3.1 cubic metres per megawatt-hour (810 US gal/MWh) for power tower plants and 3.4 m3/MWh (890 US gal/MWh) for trough plants. This was higher than the operational water consumption (with cooling towers) for nuclear at 2.7 m3/MWh (720 US gal/MWh), coal at 2.0 m3/MWh (530 US gal/MWh), or natural gas at 0.79 m3/MWh (210 US gal/MWh).[136] A 2011 study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory came to similar conclusions: for power plants with cooling towers, water consumption during operations was 3.27 m3/MWh (865 US gal/MWh) for CSP trough, 2.98 m3/MWh (786 US gal/MWh) for CSP tower, 2.60 m3/MWh (687 US gal/MWh) for coal, 2.54 m3/MWh (672 US gal/MWh) for nuclear, and 0.75 m3/MWh (198 US gal/MWh) for natural gas.[137] The Solar Energy Industries Association noted that the Nevada Solar One trough CSP plant consumes 3.2 m3/MWh (850 US gal/MWh).[138] The issue of water consumption is heightened because CSP plants are often located in arid environments where water is scarce.

In 2007, the US Congress directed the Department of Energy to report on ways to reduce water consumption by CSP. The subsequent report noted that dry cooling technology was available that, although more expensive to build and operate, could reduce water consumption by CSP by 91 to 95 percent. A hybrid wet/dry cooling system could reduce water consumption by 32 to 58 percent.[139] A 2015 report by NREL noted that of the 24 operating CSP power plants in the US, 4 used dry cooling systems. The four dry-cooled systems were the three power plants at the Ivanpah Solar Power Facility near Barstow, California, and the Genesis Solar Energy Project in Riverside County, California. Of 15 CSP projects under construction or development in the US as of March 2015, 6 were wet systems, 7 were dry systems, 1 hybrid, and 1 unspecified.

Although many older thermoelectric power plants with once-through cooling or cooling ponds use more water than CSP, meaning that more water passes through their systems, most of the cooling water returns to the water body available for other uses, and they consume less water by evaporation. For instance, the median coal power plant in the US with once-through cooling uses 138 m3/MWh (36,350 US gal/MWh), but only 0.95 m3/MWh (250 US gal/MWh) (less than one percent) is lost through evaporation.[140]

Effects on wildlife

[edit]

Insects can be attracted to the bright light caused by concentrated solar technology, and as a result birds that hunt them can be killed by being burned if they fly near the point where light is being focused. This can also affect raptors that hunt the birds.[141][142][143][144] Federal wildlife officials were quoted by opponents as calling the Ivanpah power towers "mega traps" for wildlife.[145][146][147]

Some media sources have reported that concentrated solar power plants have injured or killed large numbers of birds due to intense heat from the concentrated sunrays.[148][149] Some of the claims may have been overstated or exaggerated.[150]

According to rigorous reporting, in over six months of its first year of operation, 321 bird fatalities were counted at Ivanpah, of which 133 were related to sunlight being reflected onto the boilers.[151] Over a year, this figure rose to a total count of 415 bird fatalities from known causes, and 288 from unknown causes. Taking into account the search efficiency of the dead bird carcasses, the total avian mortality for the first year was estimated at 1492 for known causes and 2012 from unknown causes. Of the bird deaths due to known causes, 47.4% were burned, 51.9% died of collision effects, and 0.7% died from other causes.[152] Mitigations actions can be taken to reduce these numbers, such as focusing no more than four mirrors on any one place in the air during standby, as was done at Crescent Dunes Solar Energy Project.[153] Over the 2020-2021 period, 288 bird fatalities were directly accounted for at Ivanpah, a figure consistent with the ranges found in previous annual assessments.[154] In more general terms, a 2016 preliminary study assessed that the annual bird mortality per MW of installed power was similar between U.S. concentrated solar power plants and wind power plants, and higher for fossil fuel power plants.[155]

See also

[edit]- Dover Sun House

- Concentrator photovoltaics (CPV)

- Daylighting

- List of concentrating solar thermal power companies

- List of solar thermal power stations

- Luminescent solar concentrator

- Salt evaporation pond

- Solar air conditioning

- Solar thermal energy

- Solar thermal collector

- Solar water heating

- Thermal energy storage

- Thermochemical cycle

- Particle receiver

References

[edit]- ^ a b "How CSP Works: Tower, Trough, Fresnel or Dish". SolarPACES. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Boerema, Nicholas; Morrison, Graham; Taylor, Robert; Rosengarten, Gary (1 November 2013). "High temperature solar thermal central-receiver billboard design". Solar Energy. 97: 356–368. Bibcode:2013SoEn...97..356B. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2013.09.008.

- ^ Law, Edward W.; Prasad, Abhnil A.; Kay, Merlinde; Taylor, Robert A. (1 October 2014). "Direct normal irradiance forecasting and its application to concentrated solar thermal output forecasting – A review". Solar Energy. 108: 287–307. Bibcode:2014SoEn..108..287L. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2014.07.008. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_37349.

- ^ Law, Edward W.; Kay, Merlinde; Taylor, Robert A. (1 February 2016). "Calculating the financial value of a concentrated solar thermal plant operated using direct normal irradiance forecasts". Solar Energy. 125: 267–281. Bibcode:2016SoEn..125..267L. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2015.12.031. hdl:1959.4/unsworks_37350.

- ^ "Sunshine to Petrol" (PDF). Sandia National Laboratories. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Integrated Solar Thermochemical Reaction System". U.S. Department of Energy. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (10 April 2013). "New Solar Process Gets More Out of Natural Gas". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ a b c "Blue Book of China's Concentrating Solar Power Industry, 2021" (PDF). Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b "China". SolarPACES. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "CSP Projects Around the World". SolarPACES. Retrieved 15 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Blue Book of China's Concentrating Solar Power Industry 2023" (PDF). Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "New Chance for US CSP? California Outlaws Gas-Fired Peaker Plants". 13 October 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Deign, Jason (24 June 2019). "Concentrated Solar Power Quietly Makes a Comeback". GreenTechMedia.com.

- ^ "As Concentrated Solar Power bids fall to record lows, prices seen diverging between different regions". Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Chris Clarke (25 September 2015). "Are Solar Power Towers Doomed in California?". KCET.

- ^ Lilliestam, Johan (24 September 2017). "After the Desertec hype: is concentrating solar power still alive?". ETH Zurich. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ Kraemer, Susan (11 October 2017). "CSP Doesn't Compete With PV – it Competes with Gas". SolarPACES. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ smiti (4 June 2019). "Concentrated Solar Power Costs Fell 46% From 2010–2018". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Mills, Robin (25 September 2017). "UAE's push on concentrated solar power should open eyes across world". HELIOSCSP. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Kraemer, Susan (30 October 2017). "Concentrated Solar Power Dropped 50% in Six Months". HELIOSCSP. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.

- ^ "ACWA Power scales up tower-trough design to set record-low CSP price". New Energy Update / CSP Today. 20 September 2017. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ "SolarReserve Bids CSP Under 5 Cents in Chilean Auction". SolarPACES. 29 October 2017. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ susan (13 March 2017). "SolarReserve Bids 24-Hour Solar At 6.3 Cents In Chile". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Thomas W. Africa (1975). "Archimedes through the Looking Glass". The Classical World. 68 (5): 305–308. doi:10.2307/4348211. JSTOR 4348211.

- ^ Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology, Cheshire Books, pp. 66–100, ISBN 0442240058.

- ^ Meyer, CM. "From Troughs to Triumph: SEGS and Gas". EEPublishers.co.za. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Cutler J. Cleveland (23 August 2008). Shuman, Frank. Encyclopedia of Earth.

- ^ Paul Collins (Spring 2002) The Beautiful Possibility. Cabinet Magazine, Issue 6.

- ^ "A New Invention To Harness The Sun" Popular Science, November 1929

- ^ Ken Butti, John Perlin (1980) A Golden Thread: 2500 Years of Solar Architecture and Technology, Cheshire Books, p. 68, ISBN 0442240058.

- ^ "Molten Salt Storage". large.stanford.edu. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ "Power China has begun construction of the world's only 200MW Tower CSP". www.solarpaces.org. 22 March 2024. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "Ivanpah Solar Project Faces Risk of Default on PG&E Contracts". KQED News. 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016.

- ^ "eSolar Sierra SunTower: a History of Concentrating Solar Power Underperformance | Gunther Portfolio". guntherportfolio.com. 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Why Concentrating Solar Power Needs Storage to Survive". Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ Types of solar thermal CSP plants. Tomkonrad.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ a b Chaves, Julio (2015). Introduction to Nonimaging Optics, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-0673-9.

- ^ a b Roland Winston, Juan C. Miñano, Pablo G. Benitez (2004) Nonimaging Optics, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0127597515.

- ^ Norton, Brian (2013). Harnessing Solar Heat. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-7275-5.

- ^ New innovations in solar thermal Archived 21 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Popularmechanics.com (1 November 2008). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ Chandra, Yogender Pal (17 April 2017). "Numerical optimization and convective thermal loss analysis of improved solar parabolic trough collector receiver system with one sided thermal insulation". Solar Energy. 148: 36–48. Bibcode:2017SoEn..148...36C. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2017.02.051.

- ^ Houser, Kristin (12 November 2023). "Aussie scientists hit milestone in concentrated solar power They heated ceramic particles to a blistering 1450 F by dropping them through a beam of concentrated sunlight". Freethink. Archived from the original on 15 November 2023.

- ^ Vignarooban, K.; Xinhai, Xu (2015). "Heat transfer fluids for concentrating solar power systems – A review". Applied Energy. 146: 383–396. Bibcode:2015ApEn..146..383V. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.125.

- ^ a b c Christopher L. Martin; D. Yogi Goswami (2005). Solar energy pocket reference. Earthscan. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-84407-306-1.

- ^ a b "Solar thermal power plants - U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)". www.eia.gov. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Earthprints: Andasol solar power station". Reuters. Retrieved 22 October 2024.

- ^ "Linear-focusing Concentrator Facilities: DCS, DISS, EUROTROUGH and LS3". Plataforma Solar de Almería. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ a b Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Ltd, "Energy & Resources Predictions 2012" Archived 6 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2 November 2011

- ^ Helman, "Oil from the sun", "Forbes", 25 April 2011

- ^ Goossens, Ehren, "Chevron Uses Solar-Thermal Steam to Extract Oil in California", "Bloomberg", 3 October 2011

- ^ "Three solar modules of world's first commercial beam-down tower Concentrated Solar Power project to be connected to grid". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ "World's First Dual-Tower Concentrated Solar Power Plant Boosts Efficiency by 24%". Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Ivanpah - World's Largest Solar Plant in California Desert". BrightSourceEnergy.com.

- ^ "Electricity Data Browser". EIA.gov.

- ^ "Electricity Data Browser". EIA.gov.

- ^ "Electricity Data Browser". EIA.gov.

- ^ Marzouk, Osama A. (September 2022). "Land-Use competitiveness of photovoltaic and concentrated solar power technologies near the Tropic of Cancer". Solar Energy. 243: 103–119. Bibcode:2022SoEn..243..103M. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.07.051. S2CID 251357374.

- ^ Compact CLFR. Physics.usyd.edu.au (12 June 2002). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ Ausra's Compact Linear Fresnel Reflector (CLFR) and Lower Temperature Approach. ese.iitb.ac.in

- ^ Abbas, R.; Muñoz-Antón, J.; Valdés, M.; Martínez-Val, J.M. (August 2013). "High concentration linear Fresnel reflectors". Energy Conversion and Management. 72: 60–68. Bibcode:2013ECM....72...60A. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2013.01.039.

- ^ Sandia, Stirling Energy Systems set new world record for solar-to-grid conversion efficiency, Sandia, Feb. 12, 2008. Retrieved on 21 October 2021.Archived 19 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Barbee, Jeffrey (13 May 2015). "Could this be the world's most efficient solar electricity system?". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

34% of the sun's energy hitting the mirrors is converted directly to grid-available electric power

- ^ "How CSP's Thermal Energy Storage Works - SolarPACES". SolarPACES. 10 September 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- ^ "Molten salt energy storage". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "The Latest in Thermal Energy Storage". July 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Concentrating Solar Power Isn't Viable Without Storage, Say Experts". Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ "How Solar Peaker Plants Could Replace Gas Peakers". 19 October 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Aurora: What you should know about Port Augusta's solar power-tower". 21 August 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "2018, the year in which the Concentrated Solar Power returned to shine". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ "Controllable solar power – competitively priced for the first time in North Africa". Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Morocco Breaks New Record with 800 MW Midelt 1 CSP-PV at 7 Cents". Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ "Morocco Pioneers PV with Thermal Storage at 800 MW Midelt CSP Project". Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ a b "247Solar and Masen Ink Agreement for First Operational Next Generation Concentrated Solar Power Plant". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- ^ "247 solar modular & scalable concentrated solar power tech to be marketed to mining by Rost". Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Capex of modular Concentrated Solar Power plants could halve if 1 GW deployed". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Tibet's first solar district heating plant". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Renewable Energy Capacity Statistics 2024, Irena" (PDF). Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ a b Renewables Global Status Report, REN21, 2017

- ^ a b Renewables 2017: Global Status Report, REN21, 2018

- ^ a b c "Concentrated Solar Power increasing cumulative global capacity more than 11% to just under 5.5 GW in 2018". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ a b REN21 (2014). Renewables 2014: Global Status Report (PDF). ISBN 978-3-9815934-2-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- ^ REN21 (2016). Renewables 2016: Global Status Report (PDF). REN21 Secretariat, UNEP. ISBN 978-3-9818107-0-7.

- ^ "CSP Facts & Figures". csp-world.com. June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "Concentrating Solar Power" (PDF). International Renewable Energy Agency. June 2012. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ Sawin, Janet L. & Martinot, Eric (29 September 2011). "Renewables Bounced Back in 2010, Finds REN21 Global Report". Renewable Energy World. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011.

- ^ Louis Boisgibault, Fahad Al Kabbani (2020): Energy Transition in Metropolises, Rural Areas and Deserts. Wiley - ISTE. (Energy series) ISBN 9781786304995.

- ^ Google cans concentrated solar power project Archived 2012-06-15 at the Wayback Machine Reve, 24 Nov 2011. Accessed: 25 Nov 2011.

- ^ Shahan, Zachary (30 August 2020). "New Record-Low Solar Price Bid — 1.3¢/kWh". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ "Concentrating Solar Power", NREL Annual Technology Baseline, 2020, archived from the original on 21 April 2021, retrieved 23 April 2021

- ^ "Concentrating Solar Power", NERL Annual Technology Baseline, 2018, archived from the original on 23 April 2021, retrieved 23 April 2021

- ^ a b "Three Gorges Seeks EPC Bids for 200 MW of Concentrated Solar Power Under 5 cents/kWh". Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Johan Lilliestam; et al. (2017). "Empirically observed learning rates for concentrating solar power and their responses to regime change". Nature Energy. 2 (17094) 17094. Bibcode:2017NatEn...217094L. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2017.94. S2CID 256727261.

- ^ Schöniger, Franziska; et al. (2021). "Making the sun shine at night: comparing the cost of dispatchable concentrating solar power and photovoltaics with storage". Energy Sources, Part B. 16 (1): 55–74. Bibcode:2021EneSB..16...55S. doi:10.1080/15567249.2020.1843565. hdl:20.500.12708/18282.

- ^ "Making the sun shine at night: comparing the cost of dispatchable concentrating solar power and photovoltaics with storage". Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research. 2021. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 28 October 2024.

- ^ Andy Colthorpe (14 July 2021), US National Renewable Energy Lab forecasts rapid cost reduction for battery storage to 2030, Solar Media Limited

- ^ Energy, Elum (12 September 2025). "What Are the Advantages of Energy Storage Systems?". Elum Energy.

- ^ a b International Renewable Energy Agency, "Table 2.1: Comparison of different CSP Technologies", in Concentrating Solar Power, Volume 1: Power Sector Archived 23 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Renewable energy technologies: Cost analysis series, June 2012, p. 10. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ Andraka, C. E. and Powell, M. P., (2008). "Dish Stirling Development for Utility-Scale Commercialization," 14th Biennial CSP SolarPACES Symposium, Las Vegas, NV. See: https://newsreleases.sandia.gov/releases/2008/solargrid.html. Also reported in https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1431429 (2016)

- ^ Dish Engine, U.S. Department of Energy (2017). Retrieved 31 January 2025.

- ^ E. A. Fletcher (2001). "Solar thermal processing: A review". Journal of Solar Energy Engineering. 123 (2): 63. doi:10.1115/1.1349552.

- ^ Aldo Steinfeld & Robert Palumbo (2001). "Solar Thermochemical Process Technology" (PDF). Encyclopedia of Physical Science & Technology, R.A. Meyers Ed. 15. Academic Press: 237–256. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2014.

- ^ [1] Generation from Spain's Existing 2.3 GW of CSP Showing Steady Annual Increases.

- ^ Feed-in tariff (Régimen Especial). res-legal.de (12 December 2011).

- ^ Spanish government halts PV, CSP feed-in tariffs Archived 5 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Solarserver.com (30 January 2012). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ Spain Halts Feed-in-Tariffs for Renewable Energy. Instituteforenergyresearch.org (9 April 2012). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ Spain introduces 6% energy tax. Evwind.es (14 September 2012). Retrieved on 22 April 2013.

- ^ Royal Decree-Law 9/2013, of 12 July, BOE no. 167, July 13; 2013. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdl/2013/07/12/9

- ^ Law 24/2013, of 26 December, BOE no. 310, December 27; 2013. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2013/12/26/24/con

- ^ Royal Decree 413/2014, of 6 June, BOE no. 140, June 10; 2014. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2014/06/06/413

- ^ "Spanish National Energy and Climate Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2020.

- ^ "El Miteco aprueba la orden para iniciar el calendario de subastas". Miteco.gob.es.

- ^ Kraemer, S. (2017). SolarReserve Breaks CSP Price Record with 6 Cent Contract, Solarpaces [2]

- ^ Kraemer, S. (2019). Sodium-based Vast Solar Combines the Best of Trough & Tower CSP to Win our Innovation Award, Solarpaces [3]

- ^ New Energy Update (2019). CSP mini tower developer predicts costs below $50/MWh [4]

- ^ PV magazine (2020). Vast Solar eyes $600 million solar hybrid plant for Mount Isa [5]

- ^ Barnard, Michael (15 October 2025). "Port Augusta's new solar tower power project: Clever engineering, but is it a decade too late?". Renew Economy.

- ^ A Dangerous Obsession with Least Cost? Climate Change, Renewable Energy Law and Emissions Trading Prest, J. (2009). in Climate Change Law: Comparative, Contractual and Regulatory Considerations, W. Gumley & T. Daya-Winterbottom (eds.) Lawbook Company, ISBN 0455226342

- ^ The dragon awakens: Will China save or conquer concentrating solar power? https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5117648

- ^ "2018 Review: China concentrated solar power pilot projects' development". Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Johan Lilliestam, Richard Thonig, Alina Gilmanova, & Chuncheng Zang. (2020). CSP.guru (Version 2020-07-01) [Data set]. Zenodo. http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4297966

- ^ Thonig, Richard; Gilmanova, Alina; Zhan, Jing; Lilliestam, Johan (May 2022). "Chinese CSP for the World?". AIP Conference Proceedings. Solarpaces 2020: 26th International Conference on Concentrating Solar Power and Chemical Energy Systems. 2445 (1): 050007. Bibcode:2022AIPC.2445e0007T. doi:10.1063/5.0085752. S2CID 248768163.

- ^ Solarpaces (2021), EuroTrough Helped Cut Ramp-Up Time of China's 100 MW Urat CSP https://www.solarpaces.org/eurotrough-cut-ramp-up-in-china-100-mw-urat-csp%E2%80%A8

- ^ HeliosCSP (2020) China mulls withdrawal of subsidies for concentrated solar power (CSP) and offshore wind energy in 2021 http://helioscsp.com/china-mulls-withdrawal-of-subsidies-for-concentrated-solar-power-csp-and-offshore-wind-energy-in-2021/

- ^ "SECI to issue tender for 500-MW concentrated solar-thermal power project". 4 March 2024. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Kraemer, Susan (21 December 2017). "CSP is the Most Efficient Renewable to Split Water for Hydrogen". SolarPACES.org. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ EurekAlert! (15 November 2017). "Desert solar to fuel centuries of air travel". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "A solar tower fuel plant for the thermochemical production of kerosene from H2O and CO2". July 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ "The Sahara: a solar battery for Europe?". 20 December 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- ^ A Study of Very Large Solar Desert Systems with the Requirements and Benefits to those Nations Having High Solar Irradiation Potential. geni.org.

- ^ Solar Resource Data and Maps. Solareis.anl.gov. Retrieved on 22 April 2013.[dubious – discuss]

- ^ "Solar heads for the hills as tower technology turns upside down". Recharge | Renewable energy news and articles. 30 January 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Beam-Down Demos First Direct Solar Storage at 1/2 MWh Scale". HELIOSCSP. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "Environmental Impacts of Solar Power | Union of Concerned Scientists". UCSUSA.org.

- ^ Bolitho, Andrea (20 May 2019). "Smart cooling and cleaning for concentrated solar power plants". euronews.

- ^ Nathan Bracken and others, Concentrating Solar Power and Water Issues in the U.S. Southwest, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A50-61376, March 2015, p.10.

- ^ Meldrum, J.; Nettles-Anderson, S.; Heath, G.; MacKnick, J. (March 2013). "Life cycle water use for electricity generation: A review and harmonization of literature estimates". Environmental Research Letters. 8 (1) 015031. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8a5031M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/015031.

- ^ John Macknick and others, A Review of Operational Water Consumption and Withdrawal Factors for Electricity Generating Technologies Archived 6 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-50900.

- ^ Utility-Scale Solar Power: Responsible Water Resource Management, Solar Energy Industries Association, 18 March 2010.

- ^ Concentrating Solar Power Commercial Application Study Archived 26 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, US Department of Energy, 20 Feb. 2008.

- ^ John Macknick and others, A Review of Operational Water Consumption and Withdrawal Factors for Electricity Generating Technologies Archived 9 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine, NREL, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-50900.

- ^ Roach, John (20 August 2014). "Burned birds become new environmental victims of the energy quest". NBC News.

- ^ Howard, Michael (20 August 2014). "Solar thermal plants have a PR problem, and that PR problem is dead birds catching on fire". Esquire.

- ^ "Emerging solar plants scorch birds in mid-air". Fox News. 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Associated Press News". bigstory.ap.org. Archived from the original on 8 September 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "How a solar farm set hundreds of birds ablaze". Nature World News. 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Full Page Reload". IEEE Spectrum: Technology, Engineering, and Science News. 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Avian Mortality at Solar Energy Facilities in Southern California: A Preliminary Analysis" (PDF). www.kcet.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

- ^ "Solar plant's downside? Birds igniting in midair". CBS News. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014.

- ^ "California's new solar power plant is actually a death ray that's incinerating birds mid-flight". ExtremeTech.com. 20 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014.

- ^ Jake Richardson (22 August 2014). "Bird deaths from solar plant exaggerated by some media sources". Cleantechnica.com.

- ^ "For the birds: How speculation trumped fact at Ivanpah". RenewableEnergyWorld.com. 3 September 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Ho, Clifford K. (31 May 2016). "Review of Avian Mortality Studies at Concentrating Solar Power Plants". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1734 (1). Bibcode:2016AIPC.1734g0017H. doi:10.1063/1.4949164. Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ "One weird trick prevents bird deaths at solar towers". CleanTechnica.com. 16 April 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ California Energy Commission (1 April 2023). IVANPAH SOLAR ELECTRIC GENERATING SYSTEM AVIAN & BAT MONITORING PLAN 2020 – 2021 Annual Report Year 8 (Report). Retrieved 11 November 2024.

- ^ Walston, Leroy J.; Rollins, Katherine E. (July 2016). "A preliminary assessment of avian mortality at utility-scale solar energy facilities in the United States". Renewable Energy. 92: 405–414. Bibcode:2016REne...92..405W. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.02.041.

External links

[edit]- Concentrating Solar Power Utility

- NREL Concentrating Solar Power Program

- Plataforma Solar de Almeria, CSP research center

- ISFOC (Institute of Concentrating Photovoltaic Systems)

- Baldizon, Roberto (5 March 2019). "Innovations on Concentrated Solar Thermal Power". Medium. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

Concentrated solar power

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Operating Principles

Concentrated solar power systems harness solar energy by reflecting and focusing direct normal irradiance using arrays of mirrors or lenses onto a central receiver, thereby concentrating the sunlight to intensities hundreds of times greater than ambient levels and generating temperatures suitable for thermodynamic power cycles.[1] This concentration process exploits the high energy density of direct beam radiation, requiring clear skies and minimal atmospheric scattering, with typical concentration ratios ranging from 30 to 1,000 depending on the optical configuration.[1] The receiver, positioned at the focal point of the concentrators, absorbs the incident solar flux and transfers the thermal energy to a heat transfer fluid (HTF), such as synthetic oils operating up to 400°C, molten salts up to 565°C, or in some designs pressurized steam or air.[1] [14] The heated HTF circulates through pipes to a heat exchanger, where it boils water or another working fluid to produce high-pressure steam that drives a turbine in a conventional Rankine cycle, ultimately coupled to an electrical generator.[15] Alternative cycles, including Brayton gas turbines or Stirling engines, may be employed in specific designs to convert the captured heat to mechanical work. System efficiency is determined by the product of optical efficiency (accounting for mirror reflectivity, cosine losses, and beam interception), receiver thermal efficiency (ratio of absorbed minus lost heat to incident heat), mechanical conversion efficiency in the power block, and generator efficiency, yielding overall solar-to-electric efficiencies of 10-20% under optimal conditions.[6] Unlike photovoltaic systems, CSP's thermal nature enables integration with storage media, often using the HTF itself or phase-change materials to store excess heat for dispatchable generation beyond sunlight hours, enhancing capacity factors to 25-40% or higher.[2][16]Key Components

Concentrated solar power (CSP) systems comprise a solar field of mirrors, a receiver, heat transfer fluid, thermal energy storage, and a power block to generate electricity from concentrated solar heat.[1][17] The solar field consists of tracking mirrors—such as heliostats in tower systems or parabolic troughs in linear systems—that reflect and focus sunlight onto the receiver, achieving concentration ratios from 30 to over 1,000 depending on the technology.[3][17] The receiver, positioned at the mirrors' focal point, absorbs the concentrated solar radiation and transfers heat to a circulating fluid, with operating temperatures ranging from 293°C to 600°C based on the heat transfer medium and design.[3] Common heat transfer fluids include synthetic thermal oils for lower temperatures (up to 393°C) or molten nitrate salts for higher temperatures (up to 600°C), which circulate through the receiver tubes to capture and transport thermal energy.[17][3] Thermal energy storage, typically implemented via two-tank molten salt systems, stores excess heat during peak sunlight hours in a hot tank and releases it to a cold tank when needed, enabling dispatchable power generation for 10 or more hours beyond daylight.[17] The power block utilizes the heated fluid to produce steam in a heat exchanger, driving a conventional steam turbine and generator in a Rankine cycle similar to fossil fuel plants, with capacities varying from small dish systems (5–25 kW) to utility-scale plants exceeding 100 MW.[1][17] Auxiliary systems, including tracking controls and pumps, ensure precise sun-following and fluid circulation for optimal efficiency.[1]Historical Development

Early Experiments and Prototypes

The pioneering efforts in concentrated solar power began in the mid-19th century with attempts to convert solar radiation into mechanical energy via steam generation. In 1860, French inventor Augustin Mouchot developed an early solar engine that employed mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto a boiler, producing steam to power a small mechanism for pumping water.[18] By 1866, Mouchot refined this into a more efficient system using a parabolic reflector to focus rays on a water-filled tube, generating sufficient steam to drive an engine, which he demonstrated to Emperor Napoleon III and received funding for further development.[19] His devices, including a portable "Heliopompe" patented in 1861, achieved outputs capable of operating Archimedean screws for irrigation, though limited by intermittent sunlight and material constraints.[20] Mouchot's 1878 exhibition model at the Paris Universal Exposition featured a larger engine producing 50 liters of distilled water per hour or powering mechanical tools, but French colonial interests shifted to coal imports, halting support.[21] In the early 20th century, American engineer Frank Shuman advanced parabolic trough designs for practical applications. Shuman constructed experimental solar engines in Philadelphia around 1907–1912, using arrays of curved mirrors to heat fluid in tubes and drive low-pressure steam engines.[22] His most notable prototype was a 1913 solar power station in Maadi, Egypt, comprising five 54-meter-long parabolic troughs that concentrated sunlight to generate 60–70 horsepower, enabling an engine to pump 6,000 gallons of Nile water per minute for irrigation across 20 acres.[23] This off-grid facility operated commercially, producing power at a cost competitive with coal (around 4 cents per horsepower-hour), but was dismantled in 1915 amid World War I disruptions and plummeting fossil fuel prices.[22] Shuman's work demonstrated scalability potential, with plans for massive 37,000-acre installations, yet economic dominance of abundant coal deferred widespread adoption.[24] These prototypes highlighted fundamental challenges, including low solar irradiance (typically 0.5–1 kW/m²), thermal losses, and the need for tracking mechanisms to maintain focus, as evidenced by efficiencies below 10% in Mouchot's and Shuman's systems due to rudimentary optics and insulation.[25] Despite interruptions from cheaper conventional energy, the experiments established core principles of heliostat concentration and steam conversion that influenced later developments.[26]Commercialization and Expansion

The commercialization of concentrated solar power (CSP) commenced in the United States during the 1980s, driven by federal tax credits and state incentives amid concerns over fossil fuel dependence following the 1970s oil crises. The Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS) I plant, located in Kramer Junction, California, entered operation on December 20, 1984, marking the first utility-scale commercial CSP facility worldwide; it employed parabolic trough collectors to generate 13.8 MWe using synthetic oil as the heat transfer fluid.[27] This was followed by eight additional SEGS plants (II-IX) built between 1985 and 1991 by the Israel-based Luz International, culminating in a combined capacity of 354 MWe across the Mojave Desert; these plants demonstrated reliable dispatchable power generation, achieving annual capacity factors of 20-25% through integration with natural gas for evening peaking.[27] [28] The SEGS success hinged on economies of scale in trough manufacturing and long-term power purchase agreements, yet commercialization stalled after 1991 when U.S. federal investment tax credits expired, leading to Luz's bankruptcy and a near-decade hiatus in new builds; high upfront capital costs—exceeding $3,000/kWe—and sensitivity to interest rate fluctuations deterred private investment without subsidies.[27] Revitalization occurred in the early 2000s, spurred by European feed-in tariffs and research advancements in higher-temperature receivers. Spain emerged as a hub, with the PS10 solar power tower near Seville achieving commercial operation on March 30, 2007, as the first utility-scale tower plant globally, producing 11 MWe via 624 heliostats focusing sunlight onto a central receiver atop a 115-meter tower; it incorporated molten salt storage for 0.8 hours of dispatchability.[29] This paved the way for Andalusia's expansion, including PS20 (20 MWe, 2009) and the 50 MWe Solnova and 20 MWe Gemasolar plants (2011), leveraging government-backed auctions that prioritized CSP for its storage potential over photovoltaic alternatives.[28] Global expansion accelerated modestly by the late 2000s, with cumulative installed CSP capacity reaching approximately 0.5 GW outside the U.S. SEGS by 2010, concentrated in Spain (about 0.15 GW) and nascent projects in Germany, Italy, and Morocco; however, proliferation remained constrained by levelized costs of electricity (LCOE) 2-3 times higher than combined-cycle gas plants, necessitating ongoing policy support like Spain's premium tariffs averaging €0.27/kWh.[30] In the U.S., loan guarantees revived interest, culminating in approvals for over 2 GW of projects by 2010, though many faced delays due to environmental permitting and transmission bottlenecks.[31] Overall, commercialization highlighted CSP's niche in high-insolation regions with storage needs, yet underscored reliance on subsidies, as unsubsidized viability awaited further cost reductions in heliostats and receivers.[8]Recent Milestones (Post-2010)

In 2013, the Solana Generating Station, a 280 MW parabolic trough CSP plant with six hours of molten salt thermal energy storage, became operational near Gila Bend, Arizona, marking the first utility-scale CSP facility in the United States equipped with integrated storage for dispatchable power.[32] This project demonstrated the feasibility of combining CSP with storage to extend generation beyond daylight hours, producing an expected 940 GWh annually.[32] The Ivanpah Solar Power Facility, commissioned in 2014 in California's Mojave Desert, achieved 392 MW capacity using three central receiver towers and over 173,500 heliostats, becoming the world's largest CSP plant at the time and highlighting the scalability of power tower technology.[33] Unlike earlier trough-dominated designs, Ivanpah operated at higher temperatures, underscoring a post-2010 industry shift toward towers for improved efficiency, with solar flux concentrations enabling steam generation up to 565°C.[34] The Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex in Morocco progressed through phases post-2010, with Noor I (160 MW parabolic trough) operational in 2016, followed by Noor II (200 MW trough) in 2018 and Noor III (150 MW tower with seven hours storage) in 2019, culminating in a 510 MW integrated facility—the largest CSP complex globally—and exemplifying international expansion in regions with high solar irradiance.[35] In 2021, Chile's Cerro Dominador plant, a 110 MW tower with 17.5 hours of molten salt storage, entered operation, representing Latin America's first CSP with extended storage capability for near-24-hour dispatchability.[36] These developments coincided with a 47% decline in CSP levelized cost of electricity since 2010, driven by technological refinements and economies of scale, though deployment slowed amid competition from cheaper photovoltaics.[37]Core Technologies

Parabolic Trough Systems

Parabolic trough systems consist of long, curved mirrors arranged in a parabolic shape that focus direct normal irradiance onto a linear receiver tube running parallel to the focal line. These collectors operate on single-axis tracking, rotating east-west to follow the sun's daily path, achieving geometric concentration ratios typically between 70 and 80. The receiver tube, often coated with selective absorbers to minimize reradiation losses, contains a heat transfer fluid (HTF) such as synthetic thermal oil that absorbs the concentrated solar flux and reaches temperatures up to 400°C.[38][39] The primary components include the reflector structure made from low-iron glass mirrors for high reflectivity (over 93%), support frames of steel or lightweight composites, and the evacuated receiver envelope to reduce convective heat losses. Modules are typically 100-150 meters long and 5-6 meters in aperture width, interconnected in parallel rows to form large fields covering hundreds of hectares. The heated HTF circulates through a heat exchanger to generate steam for a conventional Rankine cycle turbine, with overall solar-to-electric efficiencies ranging from 14% to 18% under optimal conditions.[40][41] Operational since the 1980s, parabolic troughs represent the most mature CSP technology, with cumulative installed capacity exceeding 4 GW globally as of recent assessments. Notable installations include the Solar Energy Generating Systems (SEGS) in California, totaling 354 MW across nine plants operational from 1984 to 1991, and Nevada Solar One, a 64 MW facility commissioned in 2007. These systems demonstrate reliability in desert environments but face challenges from dust accumulation on mirrors, requiring periodic cleaning, and dependence on direct beam radiation, limiting output to clear-sky regions.[42][43]  Advancements include higher-temperature HTFs like molten salts, tested to enable efficiencies closer to 20% and better integration with storage, though traditional oil-based systems dominate due to lower material costs and proven performance. Peak thermal output per unit aperture area reaches about 0.7-0.8 kWth/m², influenced by optical efficiency (around 75%) and receiver losses.[44][45]Solar Power Towers