Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Conservatism in the United Kingdom

View on Wikipedia

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

Conservatism in the United Kingdom is related to its counterparts in other Western nations, but has a distinct tradition and has encompassed a wide range of theories over the decades of conservatism. The Conservative Party, which forms the mainstream right-wing party in Britain, has developed many different internal factions and ideologies.

History

[edit]Edmund Burke

[edit]

Edmund Burke is often considered the father of modern English conservatism in the English-speaking world.[1][2][3] Burke was a member of a conservative faction of the Whig party;[note 1] the modern Conservative Party however has been described by Lord Norton of Louth as "the heir, and in some measure the continuation, of the old Tory Party",[4] and the Conservatives are often still referred to as Tories.[5] The Australian scholar Glen Worthington has said: "For Edmund Burke and Australians of a like mind, the essence of conservatism lies not in a body of theory, but in the disposition to maintain those institutions seen as central to the beliefs and practices of society."[6]

Tories

[edit]The old established form of English and, after the Act of Union, British conservatism, was the Tory Party. It reflected the attitudes of a rural landowning class, and championed the institutions of the monarchy, the Anglican Church, the family, and property as the best defence of the social order. In the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, it seemed to be totally opposed to a process that seemed to undermine some of these bulwarks, and the new industrial elite were seen by many as enemies to the social order. It split in 1846 following the repeal of the Corn Laws (the tariff on imported corn). Proponents of free trade in the late 19th and early 20th centuries failed to make much headway as "tariff reform" resulted in new tariffs. The coalition of traditional landowners and sympathetic industrialists constituted the new Conservative Party.[7]

One-nation conservatism

[edit]

Conservatism evolved after 1820, embracing imperialism and realisation that an expanded working-class electorate could neutralise the Liberal advantage among the middle classes. Disraeli defined the Conservative approach and strengthened Conservatism as a grassroots political force. Conservatism no longer was the philosophical defence of the landed aristocracy but had been refreshed into redefining its commitment to the ideals of order, both secular and religious, expanding imperialism, strengthened monarchy, and a more generous vision of the welfare state as opposed to the punitive vision of the Whigs and Liberals.[8] As early as 1835, Disraeli attacked the Whigs and utilitarians as slavishly devoted to an industrial oligarchy, while he described his fellow Tories as the only "really democratic party of England" and devoted to the interests of the whole people.[9] Nevertheless, inside the party there was a tension between the growing numbers of wealthy businessmen on the one side, and the aristocracy and rural gentry on the other.[10] The aristocracy gained strength as businessmen discovered that they could use their wealth to buy a peerage and a country estate.

Disraeli set up a Conservative Central Office, established in 1870, and the newly formed National Union (which drew together local voluntary associations), gave the party "additional unity and strength", and Disraeli's views on social reform and the wealth disparity between the richest and poorest in society allegedly "helped the party to break down class barriers", according to the Conservative peer Lord Norton.[4] As a young man, Disraeli was influenced by the romantic movement and medievalism, and developed a critique of industrialism. In his novels, he outlined an England divided into two nations, each living in perfect ignorance of each other. He foresaw, like Karl Marx, the phenomenon of an alienated industrial proletariat. His solution involved a return to an idealised view of a corporate or organic society, in which everyone had duties and responsibilities towards other people or groups.[11]

This "one nation" conservatism is still a significant tradition in British politics, in both the Conservative Party[12][13][14] and Labour,[note 2][15] especially with the rise of the Scottish National Party during the 2015 general election.[16]

Although nominally a Conservative, Disraeli was sympathetic to some of the demands of the Chartists and argued for an alliance between the landed aristocracy and the working class against the increasing power of the middle class, helping to found the Young England group in 1842 to promote the view that the rich should use their power to protect the poor from exploitation by the middle class. The conversion of the Conservative Party into a modern mass organisation was accelerated by the concept of Tory Democracy attributed to Lord Randolph Churchill, father of Winston Churchill.[17]

Early 20th century

[edit]Winston Churchill, although best known as the most prominent conservative since Disraeli, crossed the aisle in 1904 and became a Liberal for two decades. As one of the most active and aggressive orators of his day, he thrilled the left in 1909 by ridiculing the Conservatives as, "the party of the rich against the poor, of the classes ... against the masses, of the lucky, the wealthy, the happy, and the strong against the left-out and the shut-out millions of the weak and poor." His harsh words were hurled back at him when he rejoined the Conservative Party in 1924.[18]

The shock of a landslide defeat in 1906 forced the Conservatives to rethink their operations, and they worked to build grassroots organisations that would help them win votes.[19] Responding to their defeat, the Conservative Party created the Workers Defence Union (WDU), which was designed to frighten the working class into voting for them. Though the WDU initially promoted tariff reform to protect domestic factory jobs, it soon switched to launching xenophobic and antisemitic attacks on immigrant workers and business owners, achieving considerable success by arousing fears of "alien subversion". The WDU's messages found recipients among the middle and upper classes as well, broadening their voter base.[20]

Women played a new role in the early twentieth century, as was signalled in 1906 with the establishment of the Women's Unionist and Tariff Reform Association (WUTRA). When the Liberals failed to support women's suffrage, the Conservatives acted, especially by passing the Representation of the People Act 1918 and the Equal Franchise Act of 1928.[21] They realised that housewives were often conservative in outlook, were averse to the aggressive tone of socialist rhetoric, and supported imperialism and traditional values.[22] Conservatives claimed that they represented orderly politics, peace, and the interests of the ex-serviceman's family.[23] The 1928 Act added five million more women to the electoral roll and had the effect of making women a majority, 52.7%, of the electorate in the 1929 general election,[24] which was termed the "Flapper Election".[25]

A Neo-Tory movement flourished in the 1930s as part of a pan-European reaction against modernity. A network of right-wing intellectuals and allied politicians ridiculed democracy, liberalism and modern capitalism as degenerate. They warned against the emergence of a corporate state in Britain imposed from above. The intellectuals involved followed trends in Italy, France and especially Germany. The exchange of ideas with the continent was at first a source of inspiration, reassurance and hope. After Hitler's rise in 1933 it meant their downfall. War with Germany in 1939 ended British participation in transnational radical conservatism.[26]

Post-war consensus

[edit]During and after World War II, the Conservative Party made concessions to the social democratic policies enacted by the previous Labour government. This compromise was a pragmatic measure to regain power, but also the result of the early successes of central planning and state ownership forming a cross-party consensus. The conservative version was known as Butskellism, after the almost identical Keynesian policies of Rab Butler on behalf of the Conservatives and Hugh Gaitskell for Labour. The "post-war consensus" emerged as an all-party national government under Churchill, who promised Britons a better life after the war. Conservatives especially promoted educational reforms to reach a much larger population. The foundations of the post-war consensus was the Beveridge Report. This was a report by William Beveridge, a Liberal economist who in 1942 formulated the concept of a more comprehensive welfare state in Great Britain.[27] The report sought widespread reform by identifying the "five giants on the road of reconstruction": "Want… Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness".[28] In the report were labelled a number of recommendations: the appointment of a minister to control all the insurance schemes; a standard weekly payment by people in work as a contribution to the insurance fund; old age pensions, maternity grants, funeral grants, pensions for widows and for people injured at work; a new national health service to be established.

In the period between 1945 and 1970 (the years of the consensus), unemployment averaged less than 3%. The post-war consensus included a belief in Keynesian economics,[27] a mixed economy with the nationalisation of major industries, the establishment of the National Health Service and the creation of the modern welfare state in Britain. The policies were instituted by all governments, both Labour and Conservative, in the post-war period. The consensus has been held to characterise British politics until the economic crises of the 1970s (see Secondary banking crisis of 1973–1975) which led to the end of the post-war economic boom and the rise of monetarist economics. The roots of Keynes's economics, however, lie in a critique of the economics of the depression of the interwar period. Keynesianism encouraged a more active role of the government in order to "manage overall demand so that there was a balance between demand and output".[29]

The post-war consensus in favour of the welfare state forced conservative historians, typified by Herbert Butterfield, to re-examine British history. They were no longer optimistic about human nature, nor the possibility of progress, yet neither were they open to liberalism's emphasis on individualism. As a Christian, Butterfield could argue that God had decided the course of history but had not necessarily needed to reveal its meaning to historians.[30] Thanks to Iain Macleod, Edward Heath and Enoch Powell, special attention was paid to "One-nation conservatism" (coined by Disraeli) that promised support for the poorer and working-class elements in the Party coalition.[31]

Rise of Thatcherism

[edit]

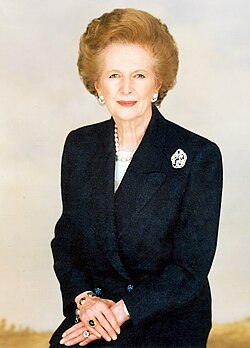

However, in the 1980s, under the leadership of Margaret Thatcher, and the influence of Keith Joseph, there was a dramatic shift in the ideological direction of British conservatism, with a movement towards free-market economic policies and neoliberalism (commonly referred to as Thatcherism).[32] As one commentator explains, "The privatisation of state owned industries, unthinkable before, became commonplace [during Thatcher's government] and has now been imitated all over the world."[33] Thatcher was described as "a radical in a conservative party",[33] and her ideology has been seen as confronting "established institutions" and the "accepted beliefs of the elite",[33] both concepts incompatible with the traditional conception of conservatism as signifying support for the established order and existing social convention (status quo).[34]

Modern conservatism

[edit]Following a third consecutive general election defeat in 2005, the Conservative Party selected David Cameron as party leader, followed by Theresa May in 2016, both of whom have served as Prime Minister and sought to modernise and change the ideological position of British conservatism.[35] From the 2010s to the present, the party has occupied a position on the right-wing of the political spectrum.[43]

In efforts to rebrand and increase the party's appeal, both leaders have adopted policies which align with liberal conservatism.[44][45] This has included a "greener" environmental and energy stance, and adoption of some socially liberal views, such as acceptance of same-sex marriage, which the Liberal Democrat MP Lynne Featherstone initially put forward. Many of these policies have been accompanied by a fiscal conservatism, in which they have maintained a hard stance on bringing down the deficit, and embarked upon a programme of economic austerity.

Other modern policies which align with one-nation conservatism[46] and Christian democracy[47][48] include education reform, extending student loan applicants to postgraduate applicants, and allowing those from poorer backgrounds to go further, whilst still increasing tuition fees and introducing a higher cap. There has also been an emphasis on human rights, in particular the European Convention on Human Rights,[49] whilst also supporting individual initiative.

In 2019 the Conservatives became the first national government in the world to officially declare a climate emergency.[50] A law was passed in 2019 that UK greenhouse gas emissions will be net zero by 2050.[51] The UK was the first major economy to embrace a legal obligation to achieve net zero carbon emissions.[52]

The 2010s saw greater division within the Conservative Party, almost exclusively over Brexit and the direction of the Brexit negotiations. Ahead of the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union, 184 of the 330 Conservative MPs (55.7%) backed Remain, compared to 218 of the 232 Labour MPs (97%), and all MPs from the SNP and Liberal Democrats. Following the vote to leave on the morning of 24 June, Cameron said that he would resign as Prime Minister, and was replaced by Theresa May. In 2019, two new parliamentary caucuses were formed; One Nation Conservatives and Blue Collar Conservatives.[53]

Conservative political parties in the United Kingdom

[edit]- Christian Party

- Christian Peoples Alliance

- Climate Party

- Conservative Party

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Heritage Party

- Reform UK

- Scottish Family Party

- Traditional Unionist Voice

- UK Independence Party

- Ulster Unionist Party

In British Overseas Territories

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ However, Burke lived before the terms "conservative" and "liberal" were used to describe political ideologies, and he dubbed his faction the "Old Whigs". cf. J. C. D. Clark, English Society, 1660–1832 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 5, p. 301.

- ^ See: One Nation Labour.

References

[edit]- ^ D. Von Dehsen 1999, p. 36.

- ^ Eccleshall 1990, p. 39.

- ^ Dobson 2009, p. 73.

- ^ a b Lord Norton of Louth. Conservative Party. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Mehta, Binita (28 May 2015). "'You don't have to be white to vote right': Why young Asians are rebelling by turning Tory". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Worthington, Glen, Conservatism in Australian National Politics, Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library, 19 February 2002

- ^ Anna Gambles, "Rethinking the politics of protection: Conservatism and the corn laws, 1830–52." English Historical Review 113.453 (1998): 928–952 online.

- ^ Gregory Claeys, "Political Thought," in Chris Williams, ed., A Companion to 19th-Century Britain (2006). p 195

- ^ Richmond & Smith 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Auerbach, The Conservative Illusion. (1959), pp. 39–40

- ^ Paterson 2001, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Stephen Evans, "The Not So Odd Couple: Margaret Thatcher and One Nation Conservatism." Contemporary British History 23.1 (2009): 101–121.

- ^ Eaton, George (27 May 2015). "Queen's Speech: Cameron's 'one nation' gloss can't mask the divisions to come". New Statesman. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Vail, Mark I. (18 November 2014). "Between One-Nation Toryism and Neoliberalism: The Dilemmas of British Conservatism and Britain's Evolving Place in Europe". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 53 (1): 106–122. doi:10.1111/jcms.12206. S2CID 142652862.

- ^ Hern, Alex (4 October 2012). "The 'one nation' supercut". New Statesman. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ White, Michael (9 May 2015). "Cameron vows to rule UK as 'one nation' but Scottish question looms". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ Chris Wrigley (2002). Winston Churchill: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-87436-990-8.

- ^ Andrew Roberts (2018). Churchill: Walking with Destiny. Penguin. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-101-98101-6.

- ^ David Thackeray, David. "Rethinking the Edwardian crisis of conservatism." Historical Journal (2011): 191–213 online.

- ^ Alan Sykes, "Radical conservatism and the working classes in Edwardian England: the case of the Workers Defence Union." English Historical Review (1998): 1180–1209 online.

- ^ David Jarvis, "Mrs Maggs and Betty: The Conservative Appeal to Women Voters in the 1920s." Twentieth Century British History 5.2 (1994): 129–152.

- ^ Clarisse Berthezène and Julie Gottlieb, eds., Rethinking Right-Wing Women: Gender And The Conservative Party, 1880s To The Present (Manchester University Press, 2018).

- ^ David Thackeray, "Building a peaceable party: masculine identities in British Conservative politics, c. 1903–24." Historical Research 85.230 (2012): 651–673.

- ^ Heater, Derek (2006). Citizenship in Britain: A History. Edinburgh University Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7486-2672-4.

- ^ "The British General Election of 1929". CQ Researcher by CQ Press. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Bernhard Dietz, "The Neo-Tories and Europe: A Transnational History of British Radical Conservatism in the 1930s." Journal of Modern European History 15.1 (2017): 85–108.

- ^ a b Kenneth O. Morgan, Britain Since 1945: The People's Peace (2001), pp. 4, 6

- ^ White, R. Clyde; Beveridge, William; Board, National Resources Planning (October 1943). "Social Insurance and Allied Services". American Sociological Review. 8 (5): 610. doi:10.2307/2085737. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 2085737.

- ^ Kavanagh, Dennis, Peter Morris, and Dennis Kavanagh. Consensus Politics from Attlee to Major. (Blackwell, 1994) p. 37.

- ^ Reba N. Soffer, "The Conservative historical imagination in the twentieth century." Albion 28.1 (1996): 1–17.

- ^ Robert Walsha, "The one nation group and one nation Conservatism, 1950–2002." Contemporary British History 17.2 (2003): 69–120.

- ^ Scott-Samuel, Alex, et al. "The Impact of Thatcherism on Health and Well-Being in Britain." International Journal of Health Services 44.1 (2014): 53–71.

- ^ a b c Davies, Stephen, Margaret Thatcher and the Rebirth of Conservatism, Ashbrook Center for Public Affairs, July 1993

- ^ Wiktionary:conservatism

- ^ Quinn, Ben (2016-06-30). "Theresa May sets out 'one-nation Conservative' pitch for leadership". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-06-12.

- ^ Kerr, Peter; Hayton, Richard (June 2015). "Whatever Happened to Conservative Party Modernisation?" (PDF). British Politics. 10 (2). London: Palgrave Macmillan: 114–130. doi:10.1057/bp.2015.22. ISSN 1746-918X. S2CID 256510669.

...the financial crisis and the political instability it generated is not enough on its own to explain this turn to the right...there is a consensus throughout this issue that the party has emerged from this junction by steering itself along the road to the right

- ^ Saini, Rima; Bankole, Michael; Begum, Neema (April 2023). "The 2022 Conservative Leadership Campaign and Post-racial Gatekeeping". Race & Class: 1–20. doi:10.1177/03063968231164599.

...the Conservative Party's history in incorporating ethnic minorities, and the recent post-racial turn within the party whereby increasing party diversity has coincided with an increasing turn to the Right

- ^ Bale, Tim (March 2023). The Conservative Party After Brexit: Turmoil and Transformation. Cambridge: Polity. pp. 3–8, 291, et passim. ISBN 978-1-5095-4601-5. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

[...] rather than the installation of a supposedly more 'technocratic' cabinet halting and even reversing any transformation on the part of the Conservative Party from a mainstream centre-right formation into an ersatz radical right-wing populist outfit, it could just as easily accelerate and accentuate it. Of course, radical right-wing populist parties are about more than migration and, indeed, culture wars more generally. Typically, they also put a premium on charismatic leafership and, if in office, on the rights of the executive over other branches of government and any intermediate institutions. And this is exactly what we have seen from the Conservative Party since 2019

- ^ de Geus, Roosmarijn A.; Shorrocks, Rosalind (2022). "Where Do Female Conservatives Stand? A Cross-National Analysis of the Issue Positions and Ideological Placement of Female Right-Wing Candidates". In Och, Malliga; Shames, Shauna; Cooperman, Rosalyn (eds.). Sell-Outs or Warriors for Change? A Comparative Look at Conservative Women in Politics in Democracies. Abingdon/New York: Routledge. pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-1-032-34657-1.

right-wing parties are also increasing the presence of women within their ranks. Prominent female European leaders include Theresa May (until recently) and Angela Merkel, from the right-wing Conservative Party in the UK and the Christian Democratic Party in Germany respectively. This article examines the extent to which women in right-wing parties are similar to their male colleagues, or whether they have a set of distinctive opinions on a range of issues

- ^ Alonso, José M.; Andrews, Rhys (September 2020). "Political Ideology and Social Services Contracting: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design" (PDF). Public Administration Review. 80 (5). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell: 743–754. doi:10.1111/puar.13177. S2CID 214198195.

In particular, there is a clear partisan division between the main left-wing party (Labour) and political parties with pronounced pro-market preferences, such as the right-wing Conservative Party

- ^ Alzuabi, Raslan; Brown, Sarah; Taylor, Karl (October 2022). "Charitable behaviour and political affiliation: Evidence for the UK". Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics. 100 101917. Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2022.101917.

...alignment to the Liberal Democrats (centre to left wing) and the Green Party (left wing) are positively associated with charitable behaviour at both the extensive and intensive margins, relative to being aligned with the right wing Conservative Party.

- ^ Oleart, Alvaro (2021). "Framing TTIP in the UK". Framing TTIP in the European Public Spheres: Towards an Empowering Dissensus for EU Integration. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 153–177. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-53637-4_6. ISBN 978-3-030-53636-7. S2CID 229439399.

the right-wing Conservative Party in government supported TTIP...This logic reproduced also a government-opposition dynamic, whereby the right-wing Conservative Party championed the agreement

- ^ [36][37][38][39][40][41][42]

- ^ "BBC News – David Cameron: I am 'Liberal Conservative'". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "Can Theresa May even sell her new conservatism to her own cabinet?". The Guardian. 2016-07-16. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ Quinn, Ben (2016-06-29). "Theresa May sets out 'one-nation Conservative' pitch for leadership". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ McGuinness, Damien (2016-07-13). "Is Theresa May the UK's Merkel?". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ ""From Big State to Big Society": Is British Conservatism becoming Christian Democratic? | Comment Magazine". www.cardus.ca. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "Where The Tory Leadership Candidates Stand On Human Rights – RightsInfo". 2016-07-04. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "UK Parliament declares climate change emergency". BBC News. 2019-05-01. Retrieved 2025-05-10.

- ^ Shepheard, Marcus (20 April 2020). "UK net zero target". Institute for Government. Archived from the original on 26 June 2024. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ Wren, Gwenyth; Christensen, Thomas (12 July 2021). "UK was First Major Economy to Embrace a Legal Obligation to Achieve Net Zero Carbon Emissions by 2050". Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ "Tory MPs launch rival campaign groups". BBC News. 2019-05-20. Retrieved 2020-03-25.

Bibliography

[edit]- D. Von Dehsen, Christian (1999). Philosophers and Religious Leaders. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-57356-152-5.

- Dobson, Andrew (2009). An Introduction to the Politics and Philosophy of José Ortega Y Gasset. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12331-0.

- Eccleshall, Robert (1990). English Conservatism Since the Restoration: An Introduction & Anthology. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-04-445773-2.

- Paterson, David (2001). Liberalism and Conservatism, 1846-1905. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-43-532737-8.

- Richmond, Charles; Smith, Paul (1998). The Self-Fashioning of Disraeli, 1818-1851. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-149729-9.

Conservatism in the United Kingdom

View on GrokipediaIdeological Foundations

Philosophical Origins

Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France, published in 1790, established the foundational philosophical critique of radical upheaval that underpins British conservatism. Burke, an Anglo-Irish statesman and Whig parliamentarian, warned against the French revolutionaries' reliance on abstract rights and rational reconstruction of society, arguing instead for the preservation of established institutions shaped by historical experience. He contended that society functions as a "partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are dead, and those who are to be born," emphasizing intergenerational continuity over contractual individualism.[9][10] Central to Burke's thought was a rejection of geometric equality and pure reason as guides for political action, favoring instead "prejudice"—understood as accumulated practical wisdom tested by time—alongside the stabilizing roles of religion, property, and hierarchy. He viewed the British constitution as an organic evolution, not a product of deliberate design, capable of reform through prudence rather than demolition and rebuilding. This framework prioritized causal realism in governance, recognizing that human nature's imperfections necessitate checks like tradition and authority to prevent chaos, as evidenced by the French Revolution's descent into terror following the abolition of monarchy and church in 1790-1793. Burke's ideas influenced conservative resistance to subsequent radical reforms in Britain, such as the push for universal suffrage, by advocating incremental change attuned to societal realities.[11][12][8] The philosophical roots of conservatism also draw from earlier Tory traditions emerging in the late 17th century, which defended monarchical prerogative, Anglican establishment, and hereditary order against Whig contractualism and exclusionist policies during the crises of 1678-1681. Toryism embodied skepticism toward human perfectibility and a preference for prescriptive authority rooted in divine right and custom, echoing elements of Thomas Hobbes's absolutism in Leviathan (1651) but tempered by British empiricism. David Hume's empiricist philosophy, particularly his essays on custom as the basis of government and justice (published 1741-1742), profoundly shaped Burke's anti-rationalism, reinforcing conservatism's emphasis on habit, convention, and empirical observation over speculative theory. These strands coalesced in Burke's synthesis, providing a coherent defense of Britain's unwritten constitution against Enlightenment abstractions.[13][14][15]Core Principles and Tenets

British conservatism, as articulated by Edmund Burke in his 1790 work Reflections on the Revolution in France, emphasizes prudence in political change, advocating for gradual, organic evolution rather than abstract rationalist reforms that disrupt established institutions.[3] Burke argued that society is a partnership across generations, where traditions embody accumulated wisdom superior to individual reason, fostering stability through reverence for inherited customs and constitutional arrangements.[16] This tenet rejects revolutionary upheaval, prioritizing empirical experience and incremental adaptation to preserve social cohesion.[8] Core principles include pragmatism, which favors practical judgment and skepticism toward grand ideologies; tradition as the repository of tested wisdom; human imperfection, positing innate flaws and self-interest that require authority and order; the organic society, viewing social bonds as evolving naturally rather than contractually; paternalism, where elites guide the less capable for the common good; and libertarianism (or neo-liberalism), stressing individual liberty, self-reliance, and market mechanisms. Michael Oakeshott elaborated pragmatism as "civil association" guided by traditions rather than rational planning. These principles draw from thinkers like Thomas Hobbes on order and human nature.[17] Conservatives uphold hierarchy as a natural order reflecting differing abilities and roles, with property rights serving as a bulwark against arbitrary power and a foundation for personal responsibility and enterprise.[17] This extends to the promotion of private enterprise and low taxes to incentivize economic growth, while maintaining the rule of law to safeguard freedoms and national security.[18] Variants encompass traditional conservatism, emphasizing hierarchy and authority; one-nation conservatism, incorporating social responsibility and paternalistic welfare; and the New Right, blending neo-liberal economics with neo-conservative social order to restore traditional values. Libertarian influences include Robert Nozick's self-ownership principle and Ayn Rand's objectivism, advocating minimal state intervention and rational self-interest.[18] In the British context, conservatism integrates paternalistic elements, such as support for institutions like the National Health Service as public services, balancing market economics with communal obligations and national sovereignty.[18] It affirms the nation-state's primacy, parliamentary sovereignty, and unionism, opposing fragmentation while valuing family, community, and individual opportunity within a framework of tradition and pragmatism.[19] These principles adapt to circumstances but remain anchored in skepticism toward ideological extremes, favoring practical governance over utopian schemes.[20]Historical Development

Early Roots in Toryism and Burke

Toryism originated during the Exclusion Crisis of 1679–1681, when a faction in the English Parliament opposed Whig efforts to bar James, Duke of York—a Catholic—from succeeding his brother Charles II to the throne, viewing such exclusion as a violation of hereditary right and divine monarchy.[13] This group, labeled "Tories" (a term initially denoting Irish outlaws), coalesced around defense of the Stuart monarchy, the established Church of England, and traditional social hierarchies against perceived republican and dissenting threats.[21] Tories emphasized paternalistic governance by the landed gentry, Anglican orthodoxy, and resistance to contractual theories of authority that undermined prescriptive legitimacy.[22] Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which installed William III and Mary II, Tories initially resisted the settlement due to its breach of hereditary succession, though many pragmatically accepted it while upholding Anglican and monarchical primacy.[23] By the early 18th century, Tory influence waned under Hanoverian rule, which favored Whigs, but the ideology persisted in rural squirearchy and high church circles, prioritizing organic social order over radical innovation. This tradition of skepticism toward abstract rights and preference for inherited customs provided a practical foundation for later conservatism, distinct from Whig constitutionalism's emphasis on liberty through parliamentary sovereignty. Edmund Burke (1729–1797), an Anglo-Irish Whig parliamentarian, articulated a philosophical synthesis of these Tory instincts in his 1790 treatise Reflections on the Revolution in France, condemning the French Revolution's abstract rationalism and egalitarian leveling as destructive to civilizational continuity.[9] Burke argued for societal evolution through prudent, precedent-guided reform rather than wholesale reconstruction, portraying institutions as "latent wisdom" accumulated across generations, akin to an "entailed inheritance" binding past, present, and future.[24] His critique highlighted the Revolution's causal perils—unleashing mob violence and ideological fanaticism absent stabilizing traditions—contrasting it with Britain's 1688 settlement, which preserved hierarchy while adjusting power.[11] Though Burke identified as a Whig reformer, his elevation of prescription, prudence, and anti-utopian realism resonated with Tory antipathy to upheaval, forging an intellectual bridge to 19th-century conservatism that transcended party lines.[25] Subsequent Tory thinkers invoked Burke to legitimize resistance to Jacobinism and reform excesses, embedding his principles—such as the organic state and moral imagination—in British conservative doctrine, despite his earlier support for American independence as a defense of traditional English liberties against metropolitan overreach.[26] This fusion underscored conservatism's roots in empirical caution over ideological purity, prioritizing causal fidelity to proven orders amid revolutionary threats.[12]19th-Century Formation under Peel

Sir Robert Peel emerged as the leader of the Tory Party following its electoral defeats after the Great Reform Act of 1832, which extended the franchise and redrew constituencies, compelling the party to reorganize and adapt to a broader electorate.[27] Peel, who had served as Home Secretary under the Duke of Wellington, sought to reposition the Tories as defenders of established institutions against radical change, marking a shift from ultra-Tory resistance to pragmatic conservatism.[28] This transition involved accepting the Reform Act's permanence while advocating measured reforms, laying the groundwork for the party's evolution into the Conservative Party by the mid-1830s.[1] A pivotal moment came with the Tamworth Manifesto, issued by Peel in December 1834 during his campaign for the Tamworth constituency ahead of the 1835 general election.[29] In this document, Peel declared opposition to the "headlong" measures of Whig radicals, pledged resistance to further organic changes in the constitution, and emphasized the Tory—soon to be Conservative—role in conserving Church, monarchy, and social order through practical improvements rather than ideological purity.[29] Historians regard the manifesto as the foundational statement of modern British conservatism, articulating principles of gradualism and adaptation that unified disparate Tory factions and appealed to middle-class voters wary of both aristocratic reaction and democratic excess.[29] Peel's leadership formalized this ideological framework, with the term "Conservative" gaining currency in party circles by 1834, distinguishing it from the more absolutist Toryism of earlier decades.[1] Peel's first premiership (November 1834 to April 1835) was a minority government that introduced the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, reforming local governance while curbing corruption, further demonstrating his commitment to efficient administration over dogmatic opposition.[30] Re-elected as Prime Minister in 1841 with a majority, Peel's second term (1841–1846) advanced conservative modernization through policies like the Mines Act 1842, limiting child labor in mines; the Factory Act 1844, regulating working hours; and the establishment of a professional civil service via the Northcote–Trevelyan Report in 1854, though implemented post-Peel.[30] These measures reflected Peel's empirical approach, prioritizing national stability and economic efficiency amid industrialization, even as they diverged from laissez-faire extremes.[28] The formation of conservatism under Peel reached a crisis with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Facing the Irish Potato Famine from 1845, which caused over one million deaths and mass emigration, and pressure from the Anti-Corn Law League led by Richard Cobden and John Bright, Peel advocated abolishing the protectionist tariffs on imported grain to avert starvation and stabilize prices.[31] Despite his earlier support for protectionism, Peel secured repeal with Whig and Radical votes on June 25, 1846, betraying the agricultural interests central to Tory support.[31] This decision precipitated a party split: Peel and his free-trade "Peelites" broke from the Protectionist majority under Benjamin Disraeli and Lord Stanley (later Lord Derby), who prioritized landed interests and imperial preference.[31] Peel's resignation followed a defeat on an Irish coercion bill days later, fragmenting the party until the 1860s fusion of Protectionists and Peelites under Derby and Disraeli.[31] The schism underscored tensions in Peelian conservatism between pragmatic adaptation to industrial realities and traditional agrarian conservatism, shaping the party's future ideological contests.[28]One-Nation Conservatism and Edwardian Era

One-nation conservatism emerged as a paternalistic strand of British Toryism, emphasizing social cohesion and state intervention to mitigate class divisions exacerbated by industrialization. The phrase "one nation" was popularized by Benjamin Disraeli in his 1844 Manchester speech and his novel Sybil, or The Two Nations (1845), which depicted Britain as split between wealthy and impoverished classes, advocating for policies to foster unity under traditional hierarchies.[32] Disraeli's vision rejected unbridled laissez-faire economics, promoting instead organic societal bonds preserved through pragmatic reforms that empowered the working classes without undermining property rights or aristocratic leadership.[33] During Disraeli's second premiership (1874–1880), this approach materialized in legislative measures addressing urban squalor and labor conditions, including the Public Health Act 1875, which centralized sanitation oversight and funded improvements via local rates; the Artisans' Dwellings Act 1875, enabling slum clearances; and the Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act 1875, which legalized peaceful picketing to balance worker rights with order.[33] These reforms, enacted amid economic recovery post-1873 depression, aimed to integrate the "condition of the people" question into Conservative statecraft, contrasting with Radical individualism and foreshadowing limited welfare provisions. Disraeli's 1872 Crystal Palace speech further articulated this as elevating the masses through imperial pride and social paternalism, securing broader electoral support via the Reform Act 1867, which doubled the electorate to about 2 million.[32] In the Edwardian era (1901–1910), one-nation principles adapted to intensified social pressures from urbanization, labor unrest, and imperial strains, as the Conservative and Unionist Party navigated free trade orthodoxy against protectionist imperatives. Under Arthur Balfour's leadership until 1906, the party grappled with Joseph Chamberlain's tariff reform campaign, launched in 1903, which sought imperial preference to generate revenue for old-age pensions and worker retraining, explicitly linking economic protectionism to social welfare for national solidarity.[34] Chamberlain, as Colonial Secretary, framed tariffs not as class favoritism but as a tool to avert "two nations" fragmentation by funding programs like the 1908 Old Age Pensions Act precursor discussions, though party divisions over food taxes contributed to the 1906 landslide defeat, reducing Conservatives to 157 seats.[35][36] Post-1906, Edwardian Conservatives under Balfour and later Andrew Bonar Law reoriented toward unionist cohesion, countering Liberal reforms and Irish home rule threats, which risked partitioning the United Kingdom. This period saw embryonic one-nation adaptations in popular conservatism, leveraging mass media and associational culture—such as sporting papers promoting patriotic loyalty—to cultivate deference amid suffrage expansion debates and strikes, like the 1910 Liverpool dockers' action.[37] Despite the "crisis of conservatism" narrative, Unionists rebuilt by 1910 elections, regaining ground through Balfour's tariff truce and emphasis on imperial unity, laying groundwork for interwar paternalism while preserving hierarchical traditions against socialist alternatives.[35] The era's tensions highlighted one-nation conservatism's core tension: reconciling market skepticism with empire-sustaining reforms to avert class warfare.[38]Interwar Period and Post-War Consensus

The Conservative Party achieved dominance in interwar British politics following the 1922 general election, when Andrew Bonar Law's government ended the Lloyd George coalition and emphasized traditional Tory values of stability and imperial unity.[39] Stanley Baldwin, who succeeded Bonar Law as prime minister in 1923, shaped interwar Conservatism through three terms (1923–1924, 1924–1929, and 1935–1937), prioritizing social harmony over ideological rigidity and articulating an early form of "one nation" conservatism that sought to bridge class divides via pragmatic governance.[40] [41] Baldwin's administration navigated the 1926 General Strike by upholding constitutional order while avoiding escalation, reflecting a paternalistic approach that viewed trade unions as partners in national stability rather than adversaries.[39] Economic challenges intensified after the 1929 Wall Street Crash, prompting Baldwin's defeat and a Labour minority government under Ramsay MacDonald.[40] In August 1931, amid a sterling crisis, MacDonald formed the National Government with Conservative support, which quickly secured a landslide victory in the October election, winning 554 of 615 seats and establishing Conservative hegemony until 1940.[42] Under Neville Chamberlain's influence as Chancellor from 1931, the government abandoned the gold standard, implemented budget-balancing measures including 10% cuts to unemployment benefits, and introduced protectionist tariffs via the Import Duties Act of 1932, marking a shift from free trade orthodoxy to imperial preference aimed at shielding British industry.[43] [44] These policies facilitated recovery, with unemployment falling from 22% in 1932 to under 10% by 1939, though critics noted uneven regional impacts favoring the south over deindustrializing areas.[45] The post-war era saw Conservatism adapt to Labour's 1945 landslide victory, which implemented the Beveridge Report's welfare blueprint, including the National Health Service in 1948 and nationalization of key industries like coal and railways.[46] Winston Churchill's Conservatives, returning to power in 1951 with a slim majority, largely preserved these reforms rather than reversing them, endorsing full employment policies and the welfare state as bulwarks against social unrest, in line with Keynesian demand management.[47] [48] This bipartisan "consensus" extended through governments led by Anthony Eden (1955–1957), Harold Macmillan (1957–1963), and Alec Douglas-Home (1963–1964), with Macmillan famously declaring in 1957 that "most of our people have never had it so good," encapsulating rising living standards via state-orchestrated growth averaging 3% annually.[49] [50] One-nation conservatism under Macmillan emphasized organic social unity and moderate interventionism, accepting mixed-economy nationalizations while promoting housing (300,000 units built yearly) and decolonization to maintain imperial ties through the Commonwealth.[51] [49] Yet underlying tensions emerged, as stagnant productivity and balance-of-payments crises by the mid-1960s exposed limits to the consensus model, with Conservatives under Edward Heath (1970–1974) attempting market-oriented reforms like the 1971 Industrial Relations Act to curb union power amid rising inflation exceeding 20% by 1975.[47] The consensus frayed further during the 1970s IMF bailout and "Winter of Discontent" strikes, eroding faith in corporatist solutions and paving the way for freer-market challenges.[47]Thatcherism and Economic Liberalization

Thatcherism emerged as a dominant strain within British conservatism during Margaret Thatcher's tenure as Prime Minister from May 1979 to November 1990, emphasizing free-market reforms, monetarist economics, and a reduction in state intervention to address the stagflation of the 1970s.[52] Influenced by economists like Milton Friedman, Thatcher's government targeted broad money supply growth to curb inflation, which had peaked above 25% in the mid-1970s and stood at 13.4% upon her election.[53] By 1983, inflation fell to 4.6%, though it rose again to around 10% by 1990 amid the Lawson boom.[53] Central to Thatcherism was an extensive privatization program, transferring state-owned enterprises to private ownership to enhance efficiency and reduce public spending. Key privatizations included British Aerospace in 1981, British Telecom in 1984 (raising £3.9 billion), British Gas in 1986, and British Airways in phases from 1987, alongside water and electricity utilities in the late 1980s.[54] These sales generated over £40 billion for the Treasury by 1990 and broadened share ownership, with 5.5 million individuals becoming shareholders by the decade's end, up from under 3 million in 1979.[55] Deregulation complemented this, notably the "Big Bang" reforms on October 27, 1986, which abolished fixed commissions on the London Stock Exchange, permitted electronic trading, and allowed firms to act as both brokers and dealers, transforming the City of London into a global financial hub.[56] Labor market liberalization involved curbing trade union power through legislation like the Employment Acts of 1980 and 1982, which restricted secondary picketing and required secret ballots for strikes. The 1984-1985 miners' strike, led by the National Union of Mineworkers against pit closures, exemplified this shift; after 12 months, the union capitulated without concessions, leading to accelerated closures from 170 pits in 1981 to 50 by 1990 and weakening union influence economy-wide.[57] This broke the post-war consensus on union privileges, enabling wage flexibility but contributing to short-term disruptions.[58] Economic outcomes were mixed: a recession in 1980-1981 saw GDP contract by 2.5% and unemployment double to 10.7% by 1982, peaking at 11.9% in 1984 with over 3 million jobless.[59] Recovery followed, with average annual GDP growth of 3.1% from 1983 to 1989, per capita GDP rising 23% over the decade, and productivity improving relative to peers.[53][52] However, manufacturing employment halved from 7 million to 3.5 million, concentrating job losses in northern regions, while the service sector, particularly finance, expanded.[60] Critics attribute rising income inequality—Gini coefficient increasing from 0.25 in 1979 to 0.34 by 1990—to these policies, though proponents argue they resolved structural inefficiencies inherited from nationalizations and union militancy.[52][61]Post-Thatcher Modernization and Brexit Era

John Major succeeded Margaret Thatcher as Conservative leader and prime minister on 28 November 1990, inheriting a party divided over Europe and facing economic pressures from high interest rates and recession.[62] Major emphasized a "classless society" and pragmatic governance, replacing the community charge with council tax in 1993 and ratifying the Maastricht Treaty in 1993 amid internal rebellions from eurosceptic MPs.[63] However, the government's commitment to the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) culminated in crisis on 16 September 1992, known as Black Wednesday, when speculative attacks forced the suspension of the pound from the ERM after expending approximately £3.3 billion in reserves to defend the currency, severely eroding the party's reputation for economic competence.[64] [65] Major's administration grappled with further scandals, including "sleaze" allegations against MPs and persistent divisions over European integration, which fragmented party unity.[66] In the 1997 general election on 1 May, the Conservatives suffered a landslide defeat, retaining only 165 seats against Labour's 418, marking the end of 18 years in power and ushering in a prolonged period of opposition.[63] During the subsequent opposition years from 1997 to 2005, under leaders William Hague (1997–2001), Iain Duncan Smith (2001–2003), and Michael Howard (2003–2005), the party struggled to formulate a cohesive strategy, achieving minimal gains in vote share—peaking at 32% in 2001 and 2005—while failing to capitalize on Labour's domestic controversies due to internal disarray over Europe and leadership inefficacy.[67] [68] David Cameron's election as leader on 6 December 2005 initiated a deliberate modernization effort to "detoxify" the Conservative brand, broadening appeal through emphasis on environmental policies, social liberalism, and compassionate conservatism, including initiatives like the "Big Society" and rhetoric on hugging "hoodies" to address youth disaffection.[69] [70] This shift moderated stances on issues such as gay rights and multiculturalism, aiming to attract centrist voters, women, and ethnic minorities alienated by Thatcher-era perceptions of divisiveness.[71] Cameron led the party to a hung parliament in the 6 May 2010 election, securing 307 seats, and formed a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, implementing austerity measures from 2010—including public spending cuts totaling £81 billion by 2015—to address the post-2008 fiscal deficit, which reduced the deficit from 10% of GDP in 2009–10 to 3.9% by 2015–16 despite sluggish growth.[72] An unexpected outright majority of 12 seats followed in the 7 May 2015 election, fulfilling a manifesto pledge for an in-out referendum on EU membership by the end of 2017 to resolve intra-party and public divisions.[73] The referendum on 23 June 2016 resulted in 51.9% voting to leave the EU on a 72.2% turnout, prompting Cameron's resignation; Theresa May assumed leadership on 13 July 2016, pledging "Brexit means Brexit" without revealing detailed plans.[74] May called a snap election on 8 June 2017 to strengthen her mandate, but the Conservatives lost their majority, securing 317 seats and relying on a DUP confidence-and-supply agreement.[75] Negotiations produced the Chequers plan in July 2018 and a withdrawal agreement in November 2018, which faced parliamentary rejection three times, including a record 230-vote defeat on 15 January 2019, highlighting divisions between customs union advocates, soft Brexiteers, and hardline withdrawal proponents.[74] [76] May resigned on 24 May 2019 after failing to secure approval. Boris Johnson won the leadership contest on 23 July 2019, appointing a cabinet dominated by Brexit hardliners and proroguing Parliament from 9 September to 14 October 2019—a move later ruled unlawful by the Supreme Court on 24 September.[77] In the 12 December 2019 general election, Johnson's "Get Brexit Done" slogan yielded a landslide victory with 365 seats and an 80-seat majority, flipping numerous Labour "Red Wall" seats in Brexit-voting areas through targeted campaigning on completing withdrawal.[78] [79] The UK formally left the EU on 31 January 2020, with the transition period ending via a trade and cooperation agreement ratified on 24 December 2020, marking the culmination of the Brexit era's fulfillment of eurosceptic commitments dating to the 1990s Maastricht rebellions, though implementation revealed tensions over Northern Ireland protocols and regulatory divergence.[80]Recent Challenges Post-2024 Election

The Conservative Party suffered its worst defeat in over a century in the July 4, 2024, general election, securing only 121 seats—a loss of 244 from 2019—and 23.7% of the vote share, compared to Labour's 412 seats and 33.7%.[81][82] This outcome ended 14 years of Conservative governance under five prime ministers, attributed by analysts to accumulated voter fatigue from policy shortcomings on immigration control, economic instability following the 2022 mini-budget under Liz Truss, protracted NHS waiting lists exceeding 7.6 million in early 2024, and internal scandals eroding public trust.[83][84] The first-past-the-post system amplified the disparity, as the party's vote fragmentation—particularly to Reform UK, which garnered 14.3% and five seats—prevented accountability mechanisms from fully manifesting, leaving Conservatives as the official opposition but with diminished parliamentary leverage.[85][86] Rishi Sunak resigned as leader on July 5, 2024, triggering a leadership contest won by Kemi Badenoch on November 2, 2024, who defeated Robert Jenrick in the final ballot with 57% of party members' votes. Badenoch's tenure has centered on internal reforms to rebuild trust, including vows for annual deportations of 150,000 illegal migrants, scrutiny of cultural institutions for ideological bias, and opposition to Labour's tax hikes and net-zero policies, framed as restoring empirical governance over virtue-signaling.[87][88] However, party membership has plummeted below 100,000, funding constraints limit campaigning, and defections to Reform UK persist, with Badenoch dismissing such moves as futile while acknowledging adaptation requires time amid voter demands for harder lines on borders and crime.[89][90] By October 2025, polls indicate persistent challenges, with two-thirds of Britons deeming the party unready for government and only 22% expecting Badenoch to become prime minister, though a majority anticipate Conservatives regaining opposition primacy over Reform.[91][92] Half of Tory members oppose her leading into the next election, favoring Jenrick or even a merger with Reform to recapture defectors—primarily working-class voters alienated by perceived softness on mass migration and cultural erosion—who represent two-thirds potentially reclaimable through policy shifts.[93][94] Reform's rise poses an existential risk, potentially supplanting Conservatives as the right-wing standard-bearer if fragmentation endures, as evidenced by sustained polling leads in Red Wall seats where immigration concerns dominate causal voter realignment.[95][96] At the October 2025 conference, Badenoch rallied against Labour's "weak" leadership but faced skepticism over unification, underscoring the need for causal reforms addressing empirical failures rather than mere rebranding.[97][98]Political Parties and Organizations

The Conservative and Unionist Party

The Conservative and Unionist Party, commonly referred to as the Conservatives or the Tories, functions as the leading political organization advancing conservative ideology in the United Kingdom. Its roots trace to the Tory parliamentarians of the Restoration era, who defended monarchy and established church against Whig reforms, evolving into a structured party in the 1830s under Robert Peel. Peel's Tamworth Manifesto, issued on 18 December 1834, defined early conservative principles by endorsing limited reforms to address grievances while opposing radical upheaval, thereby positioning the party as a defender of organic constitutional evolution.[1][99] In 1912, the party merged with the Liberal Unionists—dissenters from the Liberal Party over Irish Home Rule—and adopted the name Conservative and Unionist Party to underscore its dedication to preserving the United Kingdom's integrity. This union bolstered its organizational reach, incorporating Liberal Unionist networks and reinforcing opposition to separatism. The party's governance has spanned multiple eras, including 14 prime ministers from Peel to Rishi Sunak, with policies emphasizing pragmatic adaptation to maintain social order and economic vitality.[100][1] Ideologically, the party upholds core tenets of personal liberty, free-market enterprise, fiscal prudence, and national sovereignty, viewing these as essential for prosperity and stability. It advocates reducing state intervention to promote individual responsibility, low taxation to incentivize work and investment, robust law enforcement to deter crime, and controlled immigration to safeguard cultural cohesion. Recent platforms prioritize exiting the European Convention on Human Rights for border security, curbing public spending excesses, and rejecting expansive regulatory burdens that hinder competitiveness.[19][101][102] Organizationally, leadership selection involves MPs nominating candidates, followed by member ballots, as seen in the 2024 contest won by Kemi Badenoch on 2 November with 57% of votes against Robert Jenrick. The 1922 Committee of backbench MPs influences internal dynamics, while Conservative Campaign Headquarters coordinates national strategy and fundraising. Local constituency associations manage grassroots activities, supplemented by youth wings like Conservative Future and affiliated think tanks such as the Centre for Policy Studies.[103][104][1] Electorally, the party has secured victories in 24 of 58 general elections since 1832, governing for over half the period since 1900, including uninterrupted terms from 1951 to 1964 and 1979 to 1997. Its 2019 triumph yielded an 80-seat majority, enabling Brexit completion via the 2020 Withdrawal Agreement. However, the 4 July 2024 election marked a nadir, with only 121 seats retained amid 23.7% vote share, attributable to public fatigue with internal leadership churn, inflationary pressures, and perceived lapses in public service delivery. In opposition as of October 2025, under Badenoch's direction, the party contests Labour's fiscal expansions and net-zero mandates, seeking realignment toward uncompromised conservative priorities amid rivalry from the Reform Party.[1][82][104]

Historical Affiliates and Overseas Variants

The Tory party, emerging as a political faction in England during the late 17th century around 1679–1685, served as the primary historical predecessor to modern British conservatism, emphasizing royalism, Anglicanism, and resistance to radical change during events like the Exclusion Crisis.[13] This grouping evolved into the Conservative Party by the 1830s, formalizing opposition to Whig reforms while retaining core Tory principles of hierarchy and tradition.[2] In 1886, the party allied with the Liberal Unionists—a splinter from the Liberal Party opposing Irish Home Rule—leading to the adoption of the name Conservative and Unionist Party, which strengthened its position through shared commitments to imperial unity and constitutional stability.[105] Key affiliated organizations bolstered grassroots support in the 19th century, including the National Union of Conservative and Constitutional Associations founded in 1867 to coordinate local branches and voter mobilization, which by 1874 had over 400 affiliates.[106] The Primrose League, established in 1883 by Lord Randolph Churchill following electoral defeats, promoted Tory democracy and Conservative values across classes, including women as full members, and significantly aided party recovery by fostering patriotic and hierarchical ideals inspired by Benjamin Disraeli.[107] [108] The league operated until 2004, when its assets transferred to the Conservative Party.[109] In Northern Ireland, the Ulster Unionist Party maintained close institutional ties with the Conservatives for much of the 20th century, aligning on unionism and following Conservative parliamentary leadership until the mid-1970s, with formal electoral pacts like the Ulster Conservatives and Unionists–New Force alliance from 2009 to 2010.[110] [111] Overseas, British conservatism influenced variants in Commonwealth nations through imperial loyalism and shared traditions of hierarchy and organic society. In Canada, Toryism took root via United Empire Loyalists fleeing the American Revolution, fostering a "Red Tory" strain that blends individual liberty with communal responsibilities and state intervention for social cohesion, distinct from U.S. individualism and evident in the Conservative Party's historical emphasis on monarchy and balanced governance.[112] [113] In Australia, conservatism shaped political thought by prioritizing tradition, constitutional monarchy, and incremental reform, influencing the Liberal Party's fusion of free-market policies with cultural preservation, as seen in responses to industrialization and federation in 1901.[114] The Conservative Party's international arm, Conservatives Abroad, maintains branches in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Australasia to support expatriate members and promote core principles globally.[115]Internal Factions and Ideological Strains

Traditionalist and Paternalistic Wings

The traditionalist wing of British conservatism prioritizes the preservation of longstanding institutions, customs, and social hierarchies, viewing them as evolved mechanisms for maintaining societal stability and moral order. This strand traces its intellectual roots to Edmund Burke, whose Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) critiqued abstract ideologies and revolutionary upheaval, advocating instead for incremental change guided by inherited wisdom and "prejudice" as a safeguard against radical error.[11] Burke's emphasis on the organic nature of society, where authority derives from tradition rather than rationalist blueprints, became a cornerstone for conservatives wary of Enlightenment universalism.[116] Paternalistic conservatism complements traditionalism by positing a hierarchical duty akin to noblesse oblige, wherein societal elites bear responsibility for the welfare of subordinates to avert class antagonism and preserve national unity. Emerging prominently in the 19th century among Tory reformers, this approach rejected laissez-faire individualism in favor of state intervention to mitigate industrial hardships, as exemplified by the Young England movement led by Benjamin Disraeli in the 1840s.[117] Disraeli's novel Sybil (1845) portrayed Britain as "two nations" divided by wealth, urging paternal guidance to forge "one nation" through reforms like the Factory Act 1847, which capped women's and children's workdays at 10 hours—a measure backed by paternalist Tory MPs despite opposition from free-marketeers.[32] In Disraeli's premierships (1868 and 1874–1880), paternalism manifested in landmark legislation including the Education Act 1870, establishing elementary schooling, and the Public Health Act 1875, mandating sanitary improvements to curb urban squalor.[118] These policies aimed not at equality but at fostering deference and cohesion, reflecting Tory belief in benevolent authority to preempt revolutionary threats observed on the Continent.[119] The interwar and post-war eras saw this tradition upheld by figures like Stanley Baldwin, who cultivated a paternal image through appeals to rural traditions and imperial duty, and Harold Macmillan, whose 1950s "Middle Way" embraced welfare provisions to sustain the post-war consensus without eroding hierarchical norms.[117] In contemporary terms, the traditionalist-paternalistic synthesis persists through thinkers like Roger Scruton, who founded The Salisbury Review in 1982 to defend cultural inheritance against progressive erosion, arguing that liberty flourishes within settled customs rather than atomized individualism.[120] This wing critiques unchecked globalization and secularism for undermining communal bonds, advocating policies that reinforce family, faith, and national identity—evident in resistance to EU supranationalism and support for institutional continuity like the monarchy.[121] Empirically, such approaches have correlated with Britain's avoidance of the violent upheavals plaguing more egalitarian experiments elsewhere, attributing stability to prudent hierarchy over ideological leveling.[122]Free-Market and Libertarian Influences

The free-market orientation within British conservatism emerged as a distinct influence in the post-war era, challenging the prevailing consensus on state intervention and nationalization. Drawing from classical liberal thinkers and economists skeptical of central planning, this strand emphasized private enterprise, competition, and limited government as drivers of prosperity. The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), founded on 9 February 1955 by businessman Antony Fisher, became a key institutional vehicle for these ideas, publishing works on monetarism, privatization, and deregulation that critiqued the inefficiencies of the post-war mixed economy.[123][124] Friedrich Hayek's ideas profoundly shaped this faction, particularly through his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, which argued that socialist planning inevitably erodes individual freedoms and leads to authoritarianism—a causal mechanism rooted in the knowledge problems of centralized allocation.[125] Although Hayek explicitly rejected the conservative label in his 1960 essay "Why I Am Not a Conservative," critiquing conservatism's resistance to rational reform, his advocacy for spontaneous order and rule-based liberty resonated with UK conservatives seeking alternatives to Labour's 1945-1951 nationalizations.[126] Margaret Thatcher, elected Conservative leader on 11 February 1975, publicly embraced Hayekian principles, reportedly slamming a copy of The Constitution of Liberty (1960) on a table during a 1975 meeting to affirm her commitment to market liberalism over consensus politics. Libertarian influences within this strand prioritize individual autonomy and minimal coercion, extending free-market economics to skepticism of regulatory overreach and fiscal burdens. In the Conservative Party, this manifested in the 1980s through groups like the No Turning Back faction, which pushed for supply-side reforms, including the privatization of British Telecom in 1984 and British Gas in 1986, aiming to unleash entrepreneurial incentives and reduce public sector deficits.[127] These advocates, often aligned with think tanks like the IEA and Adam Smith Institute, argued empirically that such policies correlated with GDP growth accelerations, citing the UK's shift from 1.8% annual growth in the 1970s to 2.5% in the 1980s under Thatcher.[123] Tension persists with paternalistic wings, as libertarians critique welfare expansions for distorting incentives, evidenced by rising dependency ratios post-1997 under New Labour's continuations.[128] Post-Thatcher, free-market and libertarian voices influenced episodes like Liz Truss's September 2022 mini-budget, which proposed £45 billion in tax cuts and deregulation to boost supply-side dynamics, though markets' adverse reaction highlighted short-term credibility risks in high-debt contexts.[127] Despite such volatility, this faction maintains that causal evidence from low-regulation environments, such as Hong Kong's pre-1997 growth, supports deregulation's long-term efficacy over interventionist alternatives.[125]Nationalist and Cultural Conservatism

Nationalist and cultural conservatism within the Conservative Party prioritizes the safeguarding of British sovereignty, national cohesion, and inherited cultural norms, viewing these as essential bulwarks against erosion from globalist institutions, unchecked immigration, and ideologies that subordinate tradition to individualism or state-imposed equality. This strand posits that a nation's endurance depends on shared identity rooted in history, monarchy, and common law, rather than abstract universalism, and critiques multiculturalism for fostering parallel societies that undermine mutual obligations. Proponents argue that causal links exist between rapid demographic shifts and strains on social trust, public services, and institutional stability, drawing on observable patterns in urban enclaves where integration lags. A foundational moment occurred on April 20, 1968, when Enoch Powell delivered his "Rivers of Blood" speech in Birmingham, decrying the 1968 Race Relations Bill and projecting that continued Commonwealth immigration at then-current rates—approximately 1 million arrivals projected over decades—would provoke violent communal conflict, illustrated through anonymized constituent testimonies of cultural displacement and preferential treatment for minorities.[129][130] Though Powell was immediately sacked from the shadow cabinet by Edward Heath for inflaming tensions, the address elevated immigration as a defining political fault line, influencing subsequent party platforms on repatriation and controls.[131][132] The Cornerstone Group, established in 2004 by backbench MPs, institutionalizes these commitments through its motto "Faith, Flag, and Family," advocating policies that reinforce Britain's Anglican heritage, national symbols like the Union Jack, and policies favoring marriage and parental authority over expansive state welfare or educational indoctrination.[133][134] The group has critiqued liberal reforms on issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage, framing them as departures from organic social evolution, and supports robust border enforcement to preserve cultural homogeneity essential for democratic deliberation.[135] In the 21st century, nationalist impulses surged via the 2016 Brexit referendum, interpreted as a mandate to reclaim control over borders and laws from EU supranationalism, with the European Research Group of MPs—numbering around 100 at its peak—pressuring for a "hard" exit to prevent diluted sovereignty.[136] The New Conservatives, formed in July 2021 under MPs Danny Kruger and Miriam Cates, extend this to domestic culture wars, demanding net-zero immigration targets, tax incentives for families, and bans on divisive curricula promoting critical race theory or gender fluidity in schools, contending that elite-driven progressivism erodes working-class solidarity.[137] Prominent voices like Suella Braverman have amplified these themes, as in her May 2023 National Conservatism conference address rejecting political correctness and "multiculturalism dogma" for prioritizing group rights over national unity, and her July 2024 Washington speech attributing Conservative electoral setbacks to insufficient confrontation with liberal institutional capture.[138][139][140] Braverman's advocacy for deporting illegal entrants via the Rwanda scheme exemplified policy translation, linking border integrity to cultural preservation amid data showing small boat crossings exceeding 45,000 annually by 2022.[141] Empirically, adherents cite disparities in integration outcomes—such as higher welfare dependency and parallel legal norms in some migrant cohorts—as evidence warranting restriction, while rejecting media narratives that downplay cohesion costs due to ideological priors favoring openness. This faction contrasts with libertarian or one-nation variants by subordinating economic deregulation to communal stability, as seen in post-Brexit calls for state intervention in housing and family support to counter fertility declines below replacement levels since the 1970s.Policy Impacts and Empirical Outcomes

Economic Achievements and Causal Evidence

Under Margaret Thatcher's Conservative governments from 1979 to 1990, monetarist policies emphasizing control of the money supply contributed to a sharp decline in inflation, which fell from 13.4% in 1979 to an average of 5.9% annually from 1983 onward, breaking the cycle of wage-price spirals that had plagued the 1970s.[53] This stabilization enabled sustained GDP growth averaging 2.5% per year over the decade, with acceleration to 3.3% annually from 1983 to 1989 following initial recessions, as fiscal restraint and reduced public spending as a share of GDP from 45.5% to 39% freed resources for private investment.[52] Causal links are evident in the correlation between monetary targeting and disinflation, independent of external factors like North Sea oil revenues, which econometric analyses attribute primarily to policy-induced reductions in union power and inflationary expectations rather than commodity windfalls alone.[61] Privatization of state-owned enterprises, including British Telecom in 1984 and British Gas in 1986, generated over £20 billion in proceeds by 1990 and enhanced productivity through exposure to market competition, with privatized firms showing average labor productivity gains of 2-3% annually post-reform compared to pre-privatization trends.[55] Deregulation via the "Big Bang" financial reforms in 1986 dismantled exchange controls and boosted the City of London's global role, increasing financial services output by 150% in real terms over the decade and contributing to a reversal of the UK's relative economic decline, as GDP per capita rose from 90% of the G7 average in 1979 to parity by 1990.[142] These outcomes stemmed causally from incentive alignments under private ownership, evidenced by reduced overmanning and investment shifts, though short-term unemployment peaked at 11.9% in 1984 due to necessary restructuring in inefficient sectors like manufacturing.[54] From 2010 to 2024, Conservative-led administrations reduced the budget deficit from 10% of GDP in 2009-10 to a surplus projection by 2019 before external shocks, through spending restraint and tax increases on higher earners, averting a sovereign debt crisis akin to Greece's while maintaining average annual GDP growth of 1.8%.[143] Employment reached record highs, with the rate rising to 76.5% by 2019 and unemployment falling to 3.8%—the lowest since the 1970s—driven by welfare-to-work policies like Universal Credit, which econometric studies link to increased labor participation via conditionality and tapered benefits reducing poverty traps.[144] These fiscal consolidations preserved macroeconomic stability amid the Eurozone crisis and COVID-19, with public sector net debt stabilizing at 98% of GDP by 2019 after peaking at 85% pre-austerity adjustments, underscoring causal efficacy in prioritizing long-term solvency over short-term stimulus.[145]| Key Economic Metric | 1979 (Pre-Thatcher) | 1990 (End of Thatcher Era) | Change Attribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation Rate | 13.4% | 9.5% | Monetarist policy targeting |

| GDP Growth (Annual Avg. 1983-1989) | N/A (prior stagnation) | 3.3% | Structural reforms |

| Public Spending % GDP | 45.5% | 39% | Fiscal restraint |

| Unemployment Rate | 5.3% | 6.7% (post-peak) | Restructuring then recovery |