Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

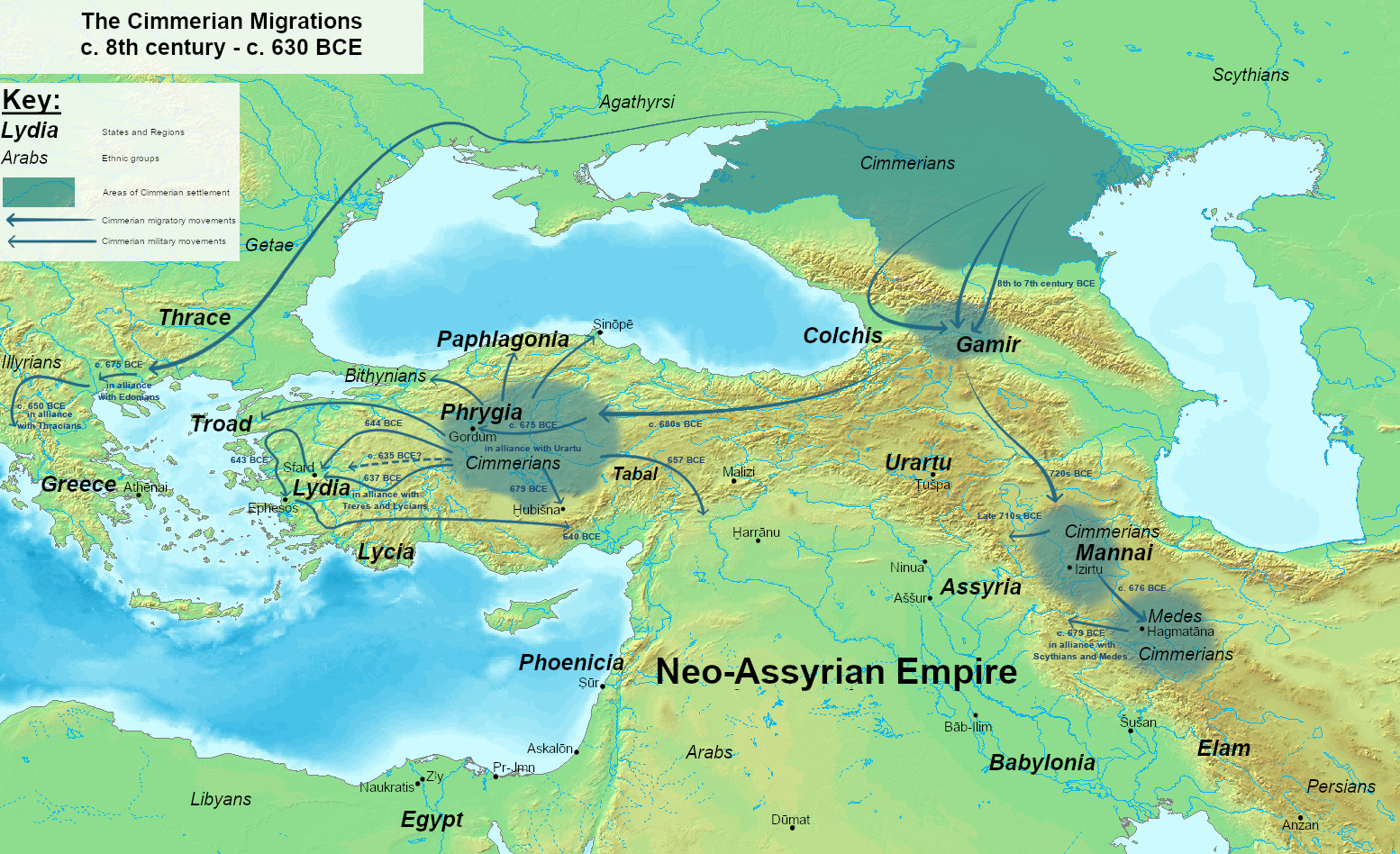

Cimmerians

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

The Cimmerians were an ancient Eastern Iranic equestrian nomadic people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe, part of whom subsequently migrated into West Asia. Although the Cimmerians were culturally Scythian, they formed an ethnic unit separate from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related and who displaced and replaced the Cimmerians.[1]

The Cimmerians themselves left no written records, and most information about them is largely derived from Neo-Assyrian records of the 8th to 7th centuries BC and from Graeco-Roman authors from the 5th century BC and later.

Name

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The English name Cimmerians is derived from Latin Cimmerii, itself derived from the Ancient Greek Kimmerioi (Κιμμέριοι),[2] of an ultimately uncertain origin for which there have been various proposals:

- according to János Harmatta, it was derived from Old Iranic *Gayamira, meaning "union of clans."[3]

- Sergey Tokhtasyev and Igor Diakonoff derived it from an Old Iranic term *Gāmīra or *Gmīra, meaning "mobile unit."[2][4]

- Askold Ivantchik derives the name of the Cimmerians from an original form *Gimĕr- or *Gimĭr-, of uncertain meaning.[5]

- Igor Diakonoff later abandoned his own etymology to support Ivantchik's proposed etymology of the name of the Cimmerians.[6]

- According to Ivantchik, the Greek form of the name Κιμμέριοι started with /k/ rather than with /g/ as in the original name due to its transmission to the Greek language through the intermediary of the Lydian language, which did not distinguish between the voiced and non-voiced velar stops.[5]

The name of the Cimmerians is attested in:

- Neo-Assyrian Akkadian as Gimirrāya (𒆳𒄀𒂆𒀀𒀀 and 𒇽𒄀𒂆𒊏𒀀𒀀),[7][8][9]

- Late Babylonian Akkadian as Gimirri (𒆳𒄀𒈪𒅕[10] and 𒆳𒄀𒂆𒊑[11]);[12]

- and Hebrew as Gōmer (גֹּמֶר).[13][14]

Broader usage

[edit]The Late Babylonian scribes of the Achaemenid Empire used the name "Cimmerians" to designate all the nomad peoples of the steppe, including the Scythians and Saka.[15][16][8]

However, while the Cimmerians were an Iranic people[17] sharing a common language, origins and culture with the Scythians[18] and are archaeologically indistinguishable from the Scythians, all sources contemporary to their activities clearly distinguished the Cimmerians and the Scythians as being two separate political entities.[19]

In 1966, the archaeologist Maurits Nanning van Loon described the Cimmerians as Western Scythians, and referred to the Scythians proper as the Eastern Scythians.[20]

History

[edit]There are three main sources of information on the historical Cimmerians:[21]

- Akkadian cuneiform texts from Mesopotamia;

- Graeco-Roman sources;

- archaeological data from the Pontic-Caspian Steppes, Caucasia, and West Asia.

Origins

[edit]The arrival of the Cimmerians in Europe was part of the larger process of westwards movement of Central Asian Iranic nomads towards Southeast and Central Europe which lasted from the 1st millennium BC to the 1st millennium AD. Other Iranic nomads, such as the Scythians, Sauromatians, Sarmatians, and Alans, would later follow.[22]

Beginning of steppe nomadism

[edit]The formation of genuine nomadic pastoralism itself happened in the early 1st millennium BC due to climatic changes which caused the environment in the Central Asian and Siberian steppes to become cooler and drier than before.[23] These changes caused the sedentary mixed farmers of the Bronze Age to become nomadic pastoralists, so that by the 9th century BC all the steppe settlements of the sedentary Bronze Age populations had disappeared,[24] and therefore led to the development of population mobility and the formation of warrior units necessary to protect herds and take over new areas.[25]

These climatic conditions in turn caused the nomadic groups to become transhumant pastoralists constantly moving their herds from one pasture to another in the steppe,[24] and to search for better pastures to the west, in Ciscaucasia and the forest steppe regions of western Eurasia.[23]

The Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex

[edit]The Cimmerians originated as a section of the first wave[26] of the nomadic populations who originated in the parts of Central Asia corresponding to eastern Kazakhstan or the Altai-Sayan region,[27] and who had, beginning in the 10th century BC and lasting until the 9th to 8th centuries BC,[28] migrated westwards into the Pontic-Caspian Steppe regions, where they formed new tribal confederations which constituted the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex.[29]

Among these tribal confederations were the Cimmerians in the Caspian Steppe, as well as the Agathyrsi in the Pontic Steppe,[29][30][31] and possibly the Sigynnae in the Pannonian Steppe.[32] The archaeological and historical records regarding these migrations are however scarce, and permit to sketch only a very broad outline of this complex development.[33]

The Cimmerians corresponded to a part of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex,[29] to whose development three main cultural influences contributed to:

- present in the development of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex is a strong impact of the native Bilozerka culture, especially in the form of pottery styles and burial traditions;[34]

- the two other influences were of foreign origin:

- attesting of the Inner Asian origin, a strong material influence from the Altai, Aržan and Karasuk cultures from Central Asia and Siberia is visible in the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex[29] of Inner Asian origin were especially dagger and arrowhead types, horse gear such as bits with stirrup-shaped terminals, deer stone-like carved stelae and Animal Style art;[35]

- in addition to this Central Asian influence, the Kuban culture of Ciscaucasia also played an important contribution in the development of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex,[29] especially regarding the adoption of Kuban culture-types of mace heads and bimetallic daggers.[35]

The Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex thus developed natively in the North Pontic region over the course of the 9th to mid-7th centuries BC from elements which had earlier arrived from Central Asia, due to which it itself exhibited similarities with the other early nomadic cultures of the Eurasian steppe and forest steppe which existed before the 7th century BC, such as the Aržan culture, so that these various pre-Scythian early nomadic cultures were thus part of a unified Aržan-Chernogorovka cultural layer originating from Central Asia.[36]

Thanks to their development of highly mobile mounted nomadic pastoralism and the creation of effective weapons suited to equestrian warfare, all based on equestrianism, these nomads from the Pontic-Caspian Steppes were able to gradually infiltrate into Central and Southeast Europe and therefore expand deep into this region over a very long period of time,[37][30] so that the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex covered a wide territory ranging from Central Europe and the Pannonian Plain in the west to Caucasia in the east, including present-day Southern Russia.[2][29]

This in turn allowed the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex itself to strongly influence the Hallstatt culture of Central Europe:[37] among these influences was the adoption of trousers, which were not used by the native populations of Central Europe before the arrival of the Central Asian steppe nomads.[32]

In the Caspian and Ciscaucasian Steppes

[edit]Within the western sections of the Eurasian Steppe, the Cimmerians lived in the Caspian[29][38] and Ciscaucasian Steppes,[39][15][40] situated on the northern and western shores of the Caspian Sea[41][42][29] and along the Araxes river, i.e., the Volga river,[43] which acted as their eastern border separating them from the Scythians;[44][45] to the west, the territory of the Cimmerians extended until the Bosporus, i.e. the Kerch Strait).[46][43]

The Cimmerians were thus the first large nomadic confederation to have inhabited the Ciscaucasian Steppe,[40] and they never formed the basic mass of the population of the Pontic Steppe,[47][29] with neither Hesiod nor Aristeas of Proconnesus ever recording them living in this area;[47] moreover the groups of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex from the Pontic Steppe and Central Europe have so far not been identifiable with the historical Cimmerians.[42] Instead, the main grouping of Iranic nomads of Central Asian origin belonging to the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex in the eastern parts of the Pontic Steppe were the Agathyrsi to the north of the Lake Maeotis.[37][30]

Some later place names mentioned by the ancient Greeks in the 5th century BC as existing in the Bosporan (Kerch Strait) region,[48] might have owed their origin to the historical presence of the Cimmerians in this area,[49][46] such as:

- the "Cimmerian ferry" (Ancient Greek: πορθμήια Κιμμέρια, romanized: porthmḗia Kimméria),

- the "country of Cimmeria" (Ancient Greek: χώρη Κιμμέρια, romanized: khṓrē Kimméria),

- and the "Cimmerian Bosporus" (Ancient Greek: Βόσπορος Κιμμέριος, romanized: Bósporos Kimmérios).

However, a derivation of these names from the historical Cimmerian presence is still very uncertain.[43]

The displacement of the Cimmerians

[edit]Arrival of the Scythians

[edit]A second wave of migration of Iranic nomads corresponded with the arrival of the early Scythians from Central Asia into the Caucasian Steppe,[37][50] which started in the 9th century BC,[51] when a significant movement of the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe started after the early Scythians were expelled out of Central Asia by either the Massagetae, who were a powerful nomadic Iranic tribe from Central Asia closely related to the Scythians,[52][53][54] or by another Central Asian people called the Issedones,[48][41] thus forcing the early Scythians to the west, across the Araxes river and into the Caspian and Ciscaucasian Steppes.[55]

Like the nomads of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex, the Scythians originated in Central Asia[56][45] in the steppes corresponding to either present-day eastern Kazakhstan or the Altai-Sayan region, which is attested by the continuity of Scythian burial rites and weaponry types with the Karasuk culture, as well as by the origin of the typically Scythian Animal Style art in the Mongolo-Siberian region.[57]

Therefore, the Scythians and the nomads of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex were closely related populations who shared a common origin, culture, and language,[18] and the earliest Scythians were therefore part of a common Aržan-Chernogorovka cultural layer originating from Central Asia, with the early Scythian culture being materially indistinguishable from the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex.[58]

This western migration of the early Scythians lasted through the middle 8th century BC,[33] and archaeologically corresponded to the movement of a population originating from Tuva in southern Siberia in the late 9th century BC towards the west, and arriving in the 8th to 7th centuries BC into Europe, especially into Ciscaucasia, which it reached some time between c. 750 and c. 700 BC,[37][2] thus following the same general migration path as the first wave of Central Asian Iranic nomads who had formed the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex.[50]

Migration of the Cimmerians

[edit]The westward migration of the Scythians brought them around c. 750 BC[59][60] to the lands of the Cimmerians,[61][45] who around this time were leaving their homelands in the Caspian Steppe to move into West Asia.[29]

The reasons for the departure of the Cimmerians are unknown,[62] although they might possibly have migrated under the pressure from the Scythians, similarly to how various nomadic peoples drove each other into the peripheries of the steppes in Europe, West Asia and the Iranian Plateau during Late Antiquity and afterwards.[40][42][62]

Ancient West Asia sources are however lacking for any such pressure on the Cimmerians by the Scythians or of any conflict between these two peoples at this early period.[63] Moreover, the arrival of the Scythians in West Asia about 40 years after the Cimmerians did so suggests that there is no available evidence to the later Graeco-Roman account that it was under pressure from the Scythians migrating into their territories that the Cimmerians crossed the Caucasus and moved south into West Asia.[64][65]

The remnants of the Cimmerians in the Caspian Steppe were assimilated by the Scythians,[61] with this absorption being facilitated by their similar ethnic backgrounds and lifestyles,[66] thus transferring the dominance of this region from the Cimmerians to the Scythians who were assimilating them,[43][30] after which the Scythians settled between the Araxes river to the east, the Caucasus mountains to the south, and the Maeotian Sea to the west,[67][37] in the Ciscaucasian Steppe where were located the Scythian kingdom's headquarters.[53]

The arrival of the Scythians and their establishment in this region in the 7th century BC[18] corresponded to a disturbance of the development of the Cimmerian peoples' Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex,[37] which was thus replaced through a continuous process[58] over the course of c. 750 to c. 600 BC by the early Scythian culture in southern Europe, which itself nevertheless still showed links to the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex.[68]

In West Asia

[edit]Over the course of the second half of the 8th century BC and the 7th century BC, the equestrian steppe nomads from Ciscaucasia expanded to the south,[69][63] beginning with the Cimmerians, who migrated from the Caspian Steppe into West Asia,[64][70][29] following the same dynamic of the steppe nomads like the Scythians, Alans and Huns who would later invade West Asia via Caucasia.[71] The Cimmerians entered West Asia by crossing the Caucasus Mountains[72][64][29] through the Alagir, Darial, and Klukhor Passes,[73] which was the same route that Sarmatian detachments would later take to invade the Arsacid Parthian Empire,[71] after which Cimmerians eventually became active in the West Asian regions of Transcaucasia, the Iranian Plateau and Anatolia.[69][74]

Reasons for southwards nomad expansion

[edit]The involvement of the steppe nomads in West Asia happened in the context of the then growth of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which under its kings Sargon II and Sennacherib had expanded from its core region of the Tigris and Euphrates valleys to rule and dominate a large territory ranging from Que (Plain Cilicia) and the Central and Eastern Anatolian mountains in the north to the Syrian Desert in the south, and from the Taurus Mountains and North Syria and the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Iranian Plateau in the east.[75][76]

Surrounding the Neo-Assyrian Empire were several smaller polities:[77][76]

- in Anatolia to the northwest, were the kingdoms of:

- Babylon, conquered several times by the Assyrians, in the south;

- Egypt in the southwest;

- Elam, whose capital was Susa, in the southeast of West Asia and the southwest of the Iranian plateau, where they were the main power, with their ruling classes being divided into pro-Assyrian and pro-Babylonian factions;

- and to the immediate north laid the powerful kingdom of Urartu (centred around Ṭušpa), which had established several installations including a system of fortresses and provincial centres over regional communities in eastern Anatolia and the northwest Iranian Plateau, was contesting its southern borderlands with the Neo-Assyrian Empire;

- in the eastern mountains were several weaker polities:

Beyond the territories under the direct Assyrian rule, especially in its frontiers in Anatolia and the Iranian Plateau, were local rulers who negotiated for their own interests by vacillating between the various rival great powers.[75]

This state of permanent social disruption caused by the rivalries of the great powers of West Asia thus proved to be a very attractive source of opportunities and wealth for the steppe nomads.[78][79] And, as the populations of the nomads of the Ciscaucasian Steppe continued to grow, their aristocrats would lead their followers southwards across the Caucasus Mountains in search of adventure and plunder in the volatile status quo then prevailing in West Asia,[80] not unlike the later Ossetian tradition of the ritual plunder called the balc (балц),[81][82] with the occasional raids eventually leading to longer expeditions, in turn leading to groups of nomads choosing to remain in West Asia in search of opportunities as mercenaries or freebooters.[83]

Thus, the Cimmerians and Scythians became active in West Asia in the 7th century BC,[61] where they would vacillate between supporting either the Neo-Assyrian Empire or other local powers, and serve them as mercenaries, depending on what they considered to be in their interests.[78][84][85] Their activities would over the course of the late-8th to late-7th centuries BC disrupt the balance of power which had prevailed between the states of Elam, Mannai, the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Urartu on one side and the mountaineer and tribal peoples on the other, eventually leading to significant geopolitical changes in this region.[39][86]

Nevertheless, a 9th or 8th century BC barrow grave, belonging from Paphlagonia to a warrior, and containing typical steppe nomad equipment, suggests that nomadic warriors had already been arriving in West Asia since the 9th century BC.[19][76] Such burials imply that some small groups of steppe nomads from Ciscaucasia might have acted as mercenaries, adventurers and settler groups in West Asia, which laid the ground for the later large scale movement of the Cimmerians and Scythians into West Asia.[19]

There appears to have been very little direct connection between the Cimmerians' migration into West Asia and the Scythians' later expansion into this same region.[60] Thus, the arrival of the Scythians in West Asia about 40 years after the Cimmerians did so suggests that there is no available evidence to the later Graeco-Roman account that it was under pressure from the Scythians migrating into their territories that the Cimmerians crossed the Caucasus and moved south into West Asia.[64][65][63]

In Transcaucasia

[edit]During the early phase of their presence in West Asia until the early 660s BC, the Cimmerians moved into Transcaucasia, which acted as their initial centre of operations:[2] after having passed through Colchis and western Caucasia and Georgia,[72][87] during the 8th century BC, the Cimmerians settled in a region located to the east of Colchis, in the areas of central Transcaucasia[88] to the immediate south of the Darial and Klukhor passes[89] and on the Cyrus river,[71] which corresponds to territory of Gori in modern-day central and southern Georgia.[90] Archaeologically, this Cimmerian presence is attested by remains associated to nomadic populations dating from between c. 750 to c. 700 BC.[71]

The presence of the Cimmerians in this area led Mesopotamian sources to call it lit. 'the Land of the Cimmerians' (𒆳𒂵𒂆, māt Gamir).[2][91][92][93]

The territory of the Cimmerians at this time was separated from the kingdom of Urartu by a Urartian vassal country named Quriani, itself located near the countries of Kulḫa and Diaueḫi, to the east and northeast of the Lake Çıldır and the north and northwest of Lake Sevan.[94][95][96]

Conflict with Urartu

[edit]

The Cimmerians appeared to have first become active in the territories to the south of the Caucasus in the c. 720s BC, where they helped the inhabitants of Colchis and of the nearby regions defeat attacks by the kingdom of Urartu.[97]

The oldest known activities of the Cimmerians in West Asia date from the mid-710s BC,[98][99] when they launched a sudden attack on Urartu's province of Uišini (whose capital was Waysi) through the territory of the kingdom of Mannai,[100] after the Mannaean king Ullusunu had invited them to attack Urartu through his kingdom's territory.[101] This attack therefore took the Urartians by surprise[102] and forced the governor of Uišini to ask for support from the king of the neighbouring small state of Muṣaṣir located on the Assyro-Urartian border region.[103]

The first recorded mentions of the Cimmerians date from spring or early summer[104] of 714 BC[105] and are from the intelligence reports of the then superpower of West Asia, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, sent by the crown prince Sennacherib to his father the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II, recording that the Urartian king Rusa I (r. c. 735 – 714 BC) had launched a counter-attack against the Cimmerians:[106] Rusa I had gathered almost all of the Urartian armed forces to campaign against the Cimmerians, with Rusa I himself as well as his commander in chief and thirteen governors personally participating in this campaign.[107] Rusa I's counter-attack was heavily defeated, and the governor of the Urartian province of Uišini was killed while the commander in chief and two governors were captured by the Cimmerian forces, attesting of the significant military power of the Cimmerians.[108]

After this defeat, the Urartian forces retreated to Quriani, while Rusa I left for the Urartian province of Wazaun.[109][96] Although Neo-Assyrian intelligence reports claimed that the Urartians were fearing an attack by the Neo-Assyrian Empire and that panic spread had among them following this defeat,[110] the situation within Urartu remained calm,[104] and the king Urzana of Muṣaṣir personally,[111] as well as a messenger from the kingdom of Ḫubuškia,[112] went to meet Rusa I to reaffirm his allegiance to Urartu.[112]

This defeat against the Cimmerians had nonetheless weakened Urartu significantly enough[89] that, when Sargon II campaigned against Urartu in 714 BC itself,[113] in the month of Tamūzu,[104] he was able to defeat the Urartians[89][114] in the region of mount Wauš, and annex Muṣaṣir,[115][116] while Rusa I consequently committed suicide[117] and his son Melarṭua was crowned as the new king of Urartu.[118] Although Urartu's power was so shaken by these defeats[119] that it stopped harassing Mannai and the Neo-Assyrian provinces on the Iranian Plateau,[101] it nevertheless remained a major power in West Asia under Melarṭua's successor, Argišti II (r. 714 – c. 685 BC).[120]

According to Neo-Assyrian reports from the reign of Sargon II itself, the king of the Cimmerians, whose name was not mentioned in these reports, had set up his camp in a region named Uṣunali. At another point, this Cimmerian king had departed from Mannai to attack Urartu, where he plundered several regions, including the district of Arḫi, and reached the city of Ḫuʾdiadae near the core territory of Urartu, forcing the governor of Uišini to request military aid for the people of Pulia and Suriana from Urzana of Muṣaṣir.[121]

Urartu mobilised its armed forces to fight against this Cimmerian invasion, although the Urartians preferred to wait until it was snowing to attack the Cimmerians, due to how snow could block roads and hinder the mobility of the horses that the Cimmerians depended on to carry on their attacks.[101][121]

Thus, the Cimmerians were attacking Urartu by passing through the routes in Mannai, thanks to which they were able to establish areas of influence on the northeastern borders of Urartu, which also provided them with access to the Anatolian Plateau and allowed them to replace Urartu as the dominant power in some parts of the western Iranian Plateau and Transcaucasia.[121]

Death of Sargon II

[edit]Possibly out of fear from the danger of the Cimmerians, the Phrygian king Midas, who had previously been a bitter opponent of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, ended hostilities with the Neo-Assyrians in 709 BC and sent a delegation to Sargon II to attempt to form an anti-Cimmerian alliance.[122]

In 705 BC, Sargon II led a campaign against a rebellious Neo-Assyrian vassal, the Neo-Hittite kingdom of Tabal in Anatolia, during which he probably also fought the Cimmerians, and was killed in battle against the Tabalian ruler Gurdî of Kulummu.[123]

After Sargon II's death, Gurdî's kingdom grew in power while the Neo-Assyrian Empire lost control of Tabal, which largely came under Gurdî's rule;[121] although Sargon II's son and successor Sennacherib (r. 705 – 681 BC) attacked Gurdî at Til-Garimmu in 695 BC, he was able to evade capture by the Neo-Assyrian forces.[124][121]

Nonetheless, although the Neo-Assyrian Empire stopped intervening in Anatolia, Sennacherib was able to secure the new northwestern Neo-Assyrian borders running from Cilicia to Melid to Ḫarran[119][121] due to which the Cimmerians ceased being mentioned in Neo-Assyrian records under his reign and would re-start being mentioned by the Assyrians only under the reign of Sennacherib's own son and successor Esarhaddon.[125][126][127]

The Cimmerians might however have possibly ended their hostilities with Urartu and acted as mercenaries in the Urartian army during this period,[127] under the reign of Argišti II.[125][128][120] Some of these Cimmerians serving in the Urartian army might have been responsible for the creation of several human funerary statues in the region of Muṣaṣir which resemble the funerary statues of steppe nomads.[129]

Cimmerians in the Assyrian army

[edit]By 680 and 679 BC, Cimmerian detachments composed of individual soldiers were serving in the Neo-Assyrian army. These might have been Cimmerian captives or Cimmerians recruited into the Neo-Assyrian military or merely Assyrian soldiers equipped in the "Cimmerian style," that is using Cimmerian bows and arrows.[130]

Division of the Cimmerians

[edit]During the period corresponding to the rule of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon (r. 681 – 669 BC), the Cimmerians split into two major divisions:[131]

- the bulk of the Cimmerians migrated from Transcaucasia into Anatolia under the leadership of the king Teušpâ, becoming the western division of the Cimmerians;

- a smaller group of the Cimmerians, called the Indaraeans (𒇽𒅔𒁕𒊒𒀀𒀀, Indaruāya[132]) in Neo-Assyrian sources, remained on the Iranian Plateau in the area near Mannai, where they had been settled since the time of Sargon II, thus forming the eastern division of the Cimmerians.

The two groups of the Cimmerians might themselves have continued to remain part of the same steppe nomad polity, which was itself nevertheless organised along various divisions depending on political changes. Such a structure was also present among:[133]

- the ancient Xiongnu, whose princes and nobles were divided into Eastern and Western groups;[134]

- the mediaeval Turkic Oguz people, who were organised into a single kingdom ruled through two divisions, each of which was composed of several tribes and was ruled by a member of the same dynasty.[135]

The Cimmerian and Scythians movements into Anatolia and the Iranian Plateau would act as catalysts for the adoption of Eurasian nomadic military and equestrian equipments by various West Asian states:[84] it was during the 7th and 6th centuries BC that "Scythian-type" socketed arrowheads and sigmoid bows ideal for use by mounted warriors, which were the most advanced shooting weapon of their time and were both technically and ballistically superior to native West Asian archery equipment, were adopted throughout West Asia.[136][84][68]

Cimmerian and Scythian trading posts and settlements on the borders of the various West Asian states at this time also supplied them with goods such as animal husbandry products, not unlike the trade relations which existed the mediaeval period between the eastern steppe nomads and the Chinese Tang Empire.[137]

On the Iranian Plateau

[edit]The eastern group of Cimmerians would remain on the northwestern Iranian plateau, where they were initially active in Mannai before later moving southwards into Media.[138]

In Mannai

[edit]Scythian expansion into West Asia

[edit]After having settled into Ciscaucasia, the Scythians became the second wave of steppe nomads to expand southwards from there, following the western shore of the Caspian Sea[47] and bypassing the Caucasus Mountains to the east through the Caspian Gates,[139] with the Scythians first arriving in Transcaucasia around c. 700 BC,[140] after which they consequently became active in West Asia.[141] This Scythian expansion into West Asia, nonetheless, never lost contact with the core Scythian kingdom located in the Ciscaucasian Steppe and was merely an extension of it, as was the concurrently occurring westward Scythian expansion into the Pontic Steppe.[68]

Once they had finally crossed into West Asia, the Scythians settled in eastern Transcaucasia and the northwest Iranian plateau,[142] between the middle course of the Cyrus and Araxes rivers before expanding into the regions corresponding to present-day Gəncə, Mingəçevir and the Muğan plain[16] in the steppes of what is presently Azerbaijan, which became their centre operations until c. 600 BC,[143][144] and this part of Transcaucasia settled by the Scythians consequently became known in the Akkadian sources from Mesopotamia as māt Iškuzaya (𒆳𒅖𒆪𒍝𒀀𒀀, 'land of the Scythians') after them.[92]

The arrival of the Scythians in West Asia about 40 years after that of the Cimmerians suggests that there is no available evidence to the later Graeco-Roman account of the Cimmerians crossing the Caucasus and moving south into West Asia under pressure from the Scythians migrating into their territories.[64][65][63]

Attacks against the Neo-Assyrian Empire

[edit]

With the Cimmerian victory on Urartu and Sargon II's successful campaign there in 714 BC having eliminated it as a threat against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Mannai had ceased being useful as a buffer zone for Neo-Assyrian power, while the Mannaeans themselves saw the Neo-Assyrian imperial demands as a now unneeded burden. Therefore, the Mannaean king Aḫšēri (r. c. 675 – c. 650 BC) welcomed the Cimmerians and the Scythians as useful allies who could offer both protection and favourable new opportunities to his kingdom, which in turn allowed him to become an opponent of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, with him subsequently remaining an enemy of Sennacherib and his successors Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.[145]

The first ever recorded mention of the Scythians is from the records of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[61][146] of c. 680 BC, which detail the first Scythian activities in West Asia and refer to the first recorded Scythian king, Išpakāya, as an ally of the Mannaeans.[147]

Around this time, Aḫšēri was hindering operations by the Neo-Assyrian Empire between its own territory and Mannai,[148] while the Scythians were recorded by the Neo-Assyrians along with the eastern Cimmerians, Mannaeans and Urartians as possibly menacing communication between the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its vassal of Ḫubuškia, with messengers travelling between the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Hubuskia being at risk of being captured by hostile Cimmerian, Mannaean, Scythian or Urartian forces.[149] Neo-Assyrian records also referred to these joint Cimmerian-Scythian forces, along with the Medes and Mannaeans, as a possible threat against the collection of tribute from Media.[150]

During these attacks, the Scythians, along with the eastern Cimmerians who were located on the border of Mannai,[151][2] were able to reach far beyond the core territories of the Iranian Plateau and attack the Neo-Assyrian provinces of Parsuwaš and Bīt-Ḫambān and even until as far as Yašuḫ, Šamaš-naṣir and Zamuā in the valley of the Diyala river.[152] One Scytho-Cimmerian attack which had invaded Ḫubuškia from Mannai was even able to threaten the core Neo-Assyrian territories by passing through Anisus and Ḫarrāniya on the Lower Zab river and sack the small city of Milqiya near Arbaʾil, close the capital cities of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, where they destroyed the Bīt-Akītī (House of the New Year Festival) of this city, which later had to be rebuilt by Esarhaddon.[153][154] These attacks into their heartlands shocked the Assyrians, who sought to know if they were to face more such invasions through divination.[148]

Meanwhile, Mannai, which had been able to grow in power under Aḫšēri, possibly thanks to its adaptation and incorporation of steppe nomad fighting technologies borrowed from its Cimmerian and Scythian allies,[155] was able to capture the territories including the fortresses of Šarru-iqbi and Dūr-Illil from the Neo-Assyrian Empire and retain them until the c. 650s BC.[156][145]

Under Argišti II, Urartu attempted to restore its power by expanding to the east towards the region of Mount Sabalan, possibly to relieve the pressure on the trade routes across the Iranian Plateau and the steppes from the Scythians, Cimmerians, and Medes.[157] Urartu remained a major power under Argišti II's successor Rusa II (r. c. 685 – c. 645 BC), the latter of whom carried out major fortification construction projects around Lake Van, such as at Rusāipatari, and at Teišebaini near what is presently Yerevan;[124] other fortifications built by Rusa II were Qale Bordjy and Qale Sangar north of Lake Urmia, as well as the fortresses of Pir Chavush, Qale Gavur and Qiz Qale around the administrative centre of Haftavan Tepe to the northwest of the Lake, all intended to monitor the activities of the allied forces of the Scythians, Mannaeans and Medes.[158]

These allied forces of the Cimmerians, Mannaeans and Scythians were defeated some time between c. 680 and c. 677 BC by Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon (r. 681 – 669 BC), who had succeeded him as the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire[159][160][68] and carried out a retaliatory campaign which reached deep into Median territory until Mount Bikni and the country of Patušarra (Patischoria) on the limits of the Great Salt Desert.[161][162] Išpakāya was killed in battle against Esarhaddon's forces during this campaign, and he was succeeded as king of the Scythians by Bartatua,[163] with whom Esarhaddon might have immediately initiated negotiations.[164]

Since the Cimmerians had left their Ciscausian homelands and moved into West Asia to seek booty, they had no interest in the local affairs of the West Asian states and therefore fought for whoever was capable of paying them the most: therefore Esarhaddon took advantage of this and, at some point before c. 675 BC, he started secret negotiations with the eastern Cimmerians, who confirmed to the Assyrians that they would remain neutral and promised not to interfere when Esarhaddon invaded Mannai again in c. 675 BC. Nonetheless, since the Cimmerians were distant foreigners with a very different culture, and therefore did not fear the Mesopotamian gods, Esarhaddon's diviner and advisor Bēl-ušēzib referred to these eastern Cimmerians instead of the Scythians as possible allies of the Mannaeans and advised Esarhaddon to spy on both them and the Mannaeans.[165]

This second Assyrian invasion of Mannai however met little success because the Cimmerians with whom Esarhaddon had negotiated had deceived him by accepting his offer only to attack his invasion force,[166] and the relations between Mannai and the Neo-Assyrian Empire remained hostile while the Cimmerians remained allied to Mannai[167] until the period lasting from 671 to 657 BC.[168] As a result of this failure, the Neo-Assyrian Empire resigned itself to waiting until the Cimmerians were no longer a threat before mounting any further expedition in Mannai.[166]

Around this same time, the Indaraeans were also active around the northern boundary of Elam,[169] and some of them might have moved to the southern Iranian Plateau, where they possibly introduced Bronze articles from the Koban culture into the Luristan bronze culture.[170]

Alliance with the Medes

[edit]The Neo-Assyrian Empire did not remain on a defensive footing in response to the activities of the allied Cimmerian, Mannaean and Scythian forces, and it soon undertook diplomatic initiatives to separate Aḫšēri from his allies: by 672 BC, the Scythians had become the allies of the Neo-Assyrian Empire after Išpakāya's successor, Bartatua, had asked for the hand of the eldest daughter of Esarhaddon, the Neo-Assyrian princess Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, and promised to form an alliance treaty with the Neo-Assyrian Empire in an act of careful diplomacy.[171]

The marriage between Bartatua and the Šērūʾa-ēṭirat likely took place,[172] in consequence of which[68] the Scythians ceased to be referred to as an enemy force in the Neo-Assyrian records[173] and the alliance between the Scythian kingdom and the Neo-Assyrian Empire was concluded,[174][68] following which the Scythian kingdom therefore remained on friendly terms with the Neo-Assyrian Empire and maintained peaceful relations with it.[127]

The eastern Cimmerians meanwhile remained hostile to Assyria,[175] and, along with the Medes, were the allies of Ellipi against an invasion by the Neo-Assyrian Empire between c. 672 and c. 669 BC.[176] The eastern Cimmerians also attacked the Assyrian province of Šubria during this time.[151][2]

It consequently became more difficult for the Neo-Assyrian Empire to control the Median city-states and the various polities in the Zagros Mountains at this point.[160] Soon, the Median chieftains Kaštaritu of Kār-Kaššî and Dusanni of Šaparda became powerful enough that their respective polities were seen by the Neo-Assyrian Empire as major forces in Media.[177] And when Kaštaritu rebelled against the Neo-Assyrian Empire and founded the first independent kingdom of the Medes after successfully liberating them from Neo-Assyrian overlordship in c. 671 to c. 669 BC,[178] the eastern Cimmerians were allied to him.[179]

Around c. 669 BC, the eastern Cimmerians experienced a defeat by the Neo-Assyrian army and were forced to retreat into their own territory,[180] and they were still on the territory of Mannai by c. 667 BC.[2]

However, some time in the late 660s or early 650s BC, the eastern Cimmerians left the Iranian Plateau and retreated to the west into Anatolia to join the western Cimmerians operating there: since Aḫšēri had depended on his alliance with the Cimmerians and Scythians to protect his kingdom from attacks by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, their departure provided Esarhaddon's successor to the Neo-Assyrian kingship, Ashurbanipal (r. 669 – 631 BC), with the opportunity to attack Mannai and recover some of the settlements which the Mannaeans had previously captured. And although Aḫšēri himself was able to withstand the Neo-Assyrian invasion, he had depended on the Cimmerians to suppress internal opposition to his rule, and their absence weakened him enough that he was soon deposed and killed by a popular rebellion which his son Uallî repressed before ascending to the throne of Mannai and submitting to the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[181]

Thus, Ashurbanipal's situation improved once he was finally re-establish Neo-Assyrian overlordship over Mannai thanks to the retreat of the Cimmerians from the Iranian Plateau.[182]

In Anatolia

[edit]At an unknown time,[62] the western Cimmerian group moved into Anatolia,[183] where it would be particularly active in the regions of Tabal, Phrygia and Lydia[184][185] and would be involved in wars against these latter two states as well as against the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[71] which itself avoided confrontations with the Cimmerians unless doing so was necessary.[186]

This Cimmerian movement into Anatolia consisted of a large scale migration, with Cimmerian families taking their mobile possessions, animals, as well as conquered booty, along with them.[185] This migration is archaeologically attested in the form of the expansion of the Scythian culture into this region,[2] although the further details of the exact time and trajectory through which the Cimmerians moved into Anatolia, and whether these movements consisted of a single group or of disparate divisions, are however unknown.[62]

Defeat by Esarhaddon

[edit]Around the same time, the rulers of the Neo-Hittite kingdom of Ḫubišna, which occupied a strategic position containing many settlements and routes linking the Konya Plain with Cilicia, might have demanded help from the Cimmerians against possible Neo-Assyrian attempts to take control of their region following the death of Warpalawas II of Tuwana, or the Cimmerians might have attempted to invade this region on their own.[160] The Neo-Assyrian Empire reacted to maintain its control of Cilicia by conducting a campaign in 679 BC during which Esarhaddon killed the Cimmerian king Teušpâ and annexed a part of the territory of the kingdom of Ḫilakku and of the kingdom of Kundi and Sissû in the region of Que.[187]

Despite this victory, and although Esarhaddon had managed to stop the advance of Cimmerians in the Neo-Assyrian province of Que so that this latter region remained under Neo-Assyrian control,[160] the military operations were not successful enough for the Assyrians to firmly occupy the areas around of Ḫubišna, nor were they able to secure the borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, leaving Que vulnerable to incursions from Tabal, Kuzzurak and Ḫilakku,[188][189] who were allied to the western Cimmerians who were establishing themselves in Anatolia at this time[190] and might still have maintained connections with them even after Esarhaddon's victory at Ḫubišna.[177]

Invasion of Phrygia

[edit]With Urartu incapable of stopping the Cimmerian advance,[124] some time around c. 675 BC,[191] under their king Dugdammî[192][183][127] (the Lygdamis of the Greek authors[183][127][177]), the western Cimmerians invaded and destroyed the empire of Phrygia, whose king Midas committed suicide, and sacked its capital of Gordion,[193] although they appear to have neither settled within the city nor destroyed its fortifications.[194]

The western Cimmerians consequently settled in Phrygia[183] and subdued part of the Phrygians[195][196] so that they controlled a large area consisting of Phrygia from its western limits which bordered on Lydia to its eastern boundaries neighbouring the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[197] after which they made Cappadocia into their centre of operations.[198]

These western Cimmerians soon became sedentary, and by c. 670 BC, they had established their rule over native Anatolian settlements as well as formed their own settlements in Central Anatolia, with the city of Ḫarzallē or Ḫarṣallē being the capital city of the Cimmerian king Dugdammî. Each of these settlements had rulers referred to by Neo-Assyrian sources as lit. 'city-lords' (Neo-Assyrian Akkadian: 𒇽𒂗𒌷𒈨𒌍, romanized: bēl ālāni): these administrators consisted of both Cimmerians and members of other ethnic groups who lived within Dugdammî's kingdom.[199]

According to a tradition later recorded by Stephanus of Byzantium, the Cimmerians found several tens of thousands of medimnoi of wheat in the underground granaries of the Phrygian village of Syassos that they used as food for a long time.[197][186]

Activities in Anatolia

[edit]When Esarhaddon conquered the nearby state of Šubria in 673 BC, Rusa II supported him, attesting of a period of non-aggression between Urartu and Assyria under the reigns of Rusa II and Esarhaddon.[124]

Assyrian sources from around this same time also recorded a Cimmerian presence in the area of the Neo-Hittite state of Tabal.[200]

And between c. 672 and c. 669 BC, an Assyrian oracular text recorded that the Cimmerians, together with the Phrygians and the Cilicians, were threatening the Neo-Assyrian Empire's newly conquered territory of Melid.[201]

The western Cimmerians were thus active in Tabal, Ḫilakku and Phrygia in the 670s BC,[195] and, in alliance with these former two states, were attacking the western Neo-Assyrian provinces.[190][202] At unknown dates, the western Cimmerians also invaded Bithynia and Paphlagonia.[203]

In the early 660s BC, the power of the Cimmerians grew drastically and they became the masters of Anatolia,[204] where they controlled a large territory[205] bordering Lydia in the west, covering Phrygia around Gordion and the Sangarios river, and reaching the Taurus Mountains in Cilicia and the borders of Urartu in the east, and encompassing the area bounded by the Black Sea in the north and the Mediterranean Sea in the south.[206]

The core territories of the western Cimmerians were in Central Anatolia between the Konya Plain and the Neo-Assyrian province of Que, but also extended to parts of the Konya Plain itself, including its western parts, and to Cappadocia, as well as to the west of Tabal,[186][207] implying that some of the Neo-Hittite states in and near the Konya Plain had become subjected to the Cimmerians.[185]

The disturbances experienced by the Neo-Assyrian Empire as result of the activities of the Cimmerians in Anatolia led to many of the rulers of this region to try to break away from Neo-Assyrian overlordship,[192] with Ḫilakku having become an independent polity again under the king Sandašarme[160] by the time that Esarhaddon had been succeeded as king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire by Ashurbanipal, so that by then the Cimmerians had effectively ended Neo-Assyrian control in Anatolia.[208]

Reunification of the Cimmerians

[edit]Soon, in the late 660s or early 650s BC, the western Cimmerians were reinforced by the eastern Cimmerians who had left the western Iranian plateau to move to the west into Anatolia.[182]

First contacts with the Greeks

[edit]

Beginning in the 8th century BC, the ancient Greeks were first starting to make expeditions in the Black Sea, and encounters with friendly native populations quickly stimulated trade relations and the development of more regular commercial transits, which in turn led to the formation of trading settlements.[209] The first Greek colony in the Black Sea, founded by settlers from Miletus around c. 750 BC, was that of Sinope,[54] in whose region the Cimmerians were active at this time.[2][210][184]

The Cimmerians destroyed Sinope during the 7th century BC and killed its founder, Habrōn, after they had invaded Paphlagonia.[211] The Greek colony of Cyzicus might also have been destroyed by the Cimmerians so that it had to be re-founded at a later date.[212] Thus, it was at this time that the Cimmerians first came into contact with the Greeks in Anatolia,[46] constituting the first encounter between the ancient Greeks and steppe nomads.[71][68][213]

In 671 to 670 BC, Cimmerian contingents were serving in the Assyrian army,[2][177] and Neo-Assyrian sources were referring to the spread of military technology and animal husbandry products referred to in Assyrian sources as "Cimmerian leather straps" and "Cimmerian bows" into the Neo-Assyrian Empire from c. 700 to c. 650 BC.[84]

First attack on Lydia

[edit]With their eastern and southeastern borders abutting the Neo-Assyrian, which had been powerful enough to defeat their king Teuspa some years earlier,[214] in the late c. 670s and early c. 660s BC, the Cimmerians under Dugdammî instead redirected their activities towards western Anatolia, where they attacked the kingdom of Lydia,[215] which under its king Gyges had been filling the power vacuum in Anatolia created by the destruction of the Phrygian Empire and was establishing itself as a new rising regional power.[216][217][218]

However, the Lydian forces were initially not able to resist this invasion,[219] and Gyges sought to find help to face the Cimmerian invasions by initiating diplomatic relations with the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 666 BC:[220] without accepting Assyrian overlordship, Gyges started to send regular embassies and diplomatic gifts to Ashurbanipal, with another Lydian embassy to the Neo-Assyrian Empire being attested from c. 665 BC.[221]

Since it was due to the threat of the Cimmerians that Gyges had made friendly overtures to the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Ashurbanipal considered the Cimmerian presence in Anatolia more useful than fighting them. Therefore, he adopted a policy of accepting whatever gifts and praise that Gyges would offer him, in exchange of which Ashurbanipa promised him support from the gods Aššur and Marduk while keeping him waiting and abstaining from providing any military support to Lydia.[182]

These Cimmerian attacks also destroyed the relations between Lydia and Phrygia, and archaeological evidence from the Lydian site of Daskyleion shows that the Cimmerian invasion ended the development of trade and economic production in the early 7th century BC which had contributed to integrating both Lydia and Ionia into the Mediterranean economy.[222] Lower class Ionian Greeks and Carians affected by this Cimmerian invasion appear to have formed a significant part of the colonists who went to set up new settlements throughout the shore of the Black Sea in the 7th century BC, such as the colonies of Borysthenēs, Histria, Apollonia Pontica, Kallatis, and Karōn Limēn.[223]

Gyges's struggle against the Cimmerians soon turned in his favour without Neo-Assyrian support, so that he was able to defeat them between c. 665 and c. 660 BC,[224] possibly through campaigns in western Central Anatolia to the east of Sardis and the south of the core Phrygian territory,[225] after which he sent captured Cimmerian city-lords as diplomatic gifts to Ashurbanipal.[226]

Gyges then stationed Carian and Ionian mercenaries at Abydos,[227] which provided an impetus for the formation of new Greek colonies in the Propontis and therefore made the Black Sea accessible to Greeks from Ionia.[228]

The defeat of the Cimmerians by Gyges in turn weakened their allies, Mugallu of Tabal and Sandašarme of Ḫilakku, enough that they were left with no choice but to submit to the authority of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in c. 662 BC.[229]

Hegemony in the Levant

[edit]Facing resistance from the Lydians in the west, the Cimmerians moved eastwards, against the Neo-Assyrian Empire:[230] despite their defeat by Gyges in the c. 660s BC, the Cimmerians' power soon grew much so that by c. 657 BC they were not only in control of a large territory in Anatolia and were one of the main political forces operating in this region, but were also able conquer part of what had previously been secure western possessions of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, such as the province of Que or even part of the Levant.[231]

These Cimmerian aggressions worried Ashurbanipal about the security of the northwest border of the Neo-Assyrian Empire enough that he sought answers concerning this situation through divination.[232] And, as a result of these Cimmerian conquests, by 657 BC, the Assyrian astrologer Akkullanu was calling the Cimmerian king Dugdammî by the title of šar-kiššati (lit. 'King of the Universe'),[183][155] which in the Mesopotamian worldview was a title that could belong only a single ruler in the world at any given time, and was normally held by the King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This attribution of the title of šar-kiššati to a foreign ruler was an unprecedented situation of which there is no other known occurrence throughout the duration of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[233][207][234]

Akkullanu nevertheless also assured to Ashurbanipal that he would eventually regain the kiššūtu, that is the world hegemony which rightfully belonged to him, from the Cimmerians who had usurped it.[233]

This extraordinary situation meant that, under Dugdammî, who was their most powerful king,[183] the Cimmerians had become a force feared by Ashurbanipal, and the Cimmerians' successes against the Neo-Assyrian Empire meant that they had become recognised in ancient West Asia as equally powerful as Ashurbanipal himself.[233]

This situation remained unchanged throughout the rest of the 650s and the early 640s BC,[235] with the Cimmerian aggressions worrying Ashurbanipal regarding the security of his northwestern border so much that he often sought answers regarding this situation through divination.[236]

These setbacks, along with Ashurbanipal's refusal to provide military support to Lydia, discredited Neo-Assyrian power enough that Gyges understood that he could not rely on Assyrian support against the Cimmerians, and, once the Cimmerians had moved to the east and their attacks on his kingdom decreased, he therefore ended diplomacy with the Neo-Assyrian Empire and instead sent troops to help the Egyptian kinglet Psamtik I of Sais,[237] who had himself been a Neo-Assyrian vassal who was then eliminating the other Neo-Assyrian vassal kinglets in Lower Egypt to unite the whole of Egypt under his own rule.[238][239] Ashurbanipal responded to Gyges's disengagement with the Neo-Assyrian Empire by cursing him.[240][239][214]

Exhaustion of Assyria

[edit]Neo-Assyrian power experienced another significant blow in 652 BC, when Esarhaddon's eldest son, Šamaš-šuma-ukin, who had succeeded him as king of Babylon, rebelled against his younger brother Ashurbanipal: it took Ashurbanipal four years to fully suppress the Babylonian rebellion by 648 BC, and another year to destroy the power of Elam, who had supported Šamaš-šuma-ukin,[155] and, although Ashurbanipal would nevertheless be able to maintain control over Babylonia for the rest of his reign, the Neo-Assyrian Empire finally emerged from this crisis severely worn out.[241]

One of the oracular responses received by Ashurbanipal in 652 BC itself claimed that the goddess Ishtar had promised to him that the Cimmerians would be defeated similarly to how Ashurbanipal himself had defeated the Elamites and killed their king Teumman in 653 BC.[242]

Meanwhile, Dugdammî might have taken advantage of the civil war within the Neo-Assyrian Empire caused by Samas-suma-ukin's rebellion to attack northwestern Neo-Assyrian provinces.[243]

Attack on Šubria

[edit]In the 650s BC, the Cimmerians were allied to Urartu[202][129] and were serving as auxiliaries in the service of its king Rusa II, who was then attempting to attack the newly conquered Assyrian province of Šubria near the Urartian border.[244] Urartu was thus integrating steppe nomad mercenaries into its armed forces, and was also trying to borrow the military technology of these peoples.[121]

Alliance with the Treres

[edit]

Around the c. 660s BC, the Thracian tribe of the Treres migrated across the Thracian Bosporus and invaded Anatolia from the north-west,[204][245][246] after which they allied with the Cimmerians,[2] and, from around the c. 650s BC, the Cimmerians were nomadising in Anatolia along with the Treres.[202][247]

Second attack on Lydia

[edit]The Cimmerians and Treres under Lygdamis and the Treran king Kōbos,[248] and in alliance with the Lycians or Lycaonians, attacked Lydia for a second time in 644 BC:[249] this time they defeated the Lydians and captured their capital city of Sardis except for its citadel, and Gyges was killed during this attack.[250] The Neo-Assyrian sources blamed Gyges's death on his own hubris, that is on his own independent actions, by claiming that the Cimmerians invaded Lydia and killed him as punishment for him providing Psamtik I with the troops he used to eliminate the other pro-Assyrian Egyptian kinglets and unify Egypt under his sole rule.[251][214]

After this attack, Gyges's son Ardys succeeded him as king of Lydia and resumed diplomatic activity with the Neo-Assyrian Empire with the hope of military support which Ashurbanipal again did not provide.[252] As a result, Ardys might possibly have been forced to submit to the Cimmerians,[214] although the Cimmerians themselves never ruled Lydia.[253]

Attack on Ionia and Aeolia

[edit]After sacking Sardis, Lydgamis and Kobos led the Cimmerians and the Treres into invading the Greek city-states of the Troad,[128][2] Aeolia and Ionia on the western coast of Anatolia,[254] where they destroyed the city of Magnesia on the Meander as well as the Artemision of Ephesus.[255] The city of Colophon joined Ephesus and Magnesia in resisting the Cimmerian invasion.[256]

The Cimmerians and Treres remained on the western coast of Anatolia inhabited by the Greeks for three years, from c. 644 to c. 641 BC, where later Greek tradition claimed that Lygdamis had occupied Antandros and Priene, which forced a large number of the inhabitants of the coastal region called Batinētis to flee to the islands of the Aegean Sea.[257]

Activities in Cilicia

[edit]Sensing the exhaustion of Neo-Assyrian power following the suppression of the revolt of Šamaš-šuma-ukin, the Cimmerians and Treres moved to Cilicia on the north-west border of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in c. 640 BC itself, immediately after their third invasion of Lydia and the attack on the Asian Greek cities. There, Dugdammî allied with Mugallu's son and successor as king of the then rebellious Assyrian vassal state of Tabal, Mussi, to attack the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[258]

Although the Urartians had sent tribute to the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 643 BC, the Urartian king Sarduri III (r. c. 645 – c. 625 BC), who had been a Neo-Assyrian vassal, was at this time also forced to accept the suzerainty of the Cimmerians.[259][155][243]

However, Mussi died before the planned attack on Neo-Assyrian Empire and his kingdom collapsed when its elite fled or was deported to Assyria, while Dugdammî carried it out but failed because, according to Neo-Assyrian sources, he became ill and fire broke out in his camp.[260] Following this, Dugdammî was faced with a revolt against himself, after which ended his hostilities against the Neo-Assyrian Empire and sent tribute to Ashurbanipal to form an alliance with him, while Ashurbanipal forced Dugdammi to swear an oath to not attack the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[248][261][262]

Death of Dugdammî

[edit]Dugdammî soon broke his oath and attacked the Neo-Assyrian Empire again, but during his military campaign he contracted a grave illness whose symptoms included paralysis of half of his body and vomiting of blood as well as gangrene of the genitals, and he consequently committed suicide in 640 BC[263] in Cilicia itself.[264]

Dugdammî was succeeded as king of the Cimmerians in Cilicia by his son Sandakšatru,[265] who continued Dugdammî's attacks against the Neo-Assyrian Empire[266] but failed just like his father.[128][267]

The power of the Cimmerians dwindled quickly after the death of Dugdammî,[268][269] although the Lydian kings Ardys and Sadyattes might however have either died fighting the Cimmerians or were deposed for being incapable of efficiently fighting them, respectively in c. 637 and c. 635 BC.[270]

Final defeat

[edit]

Despite these setbacks, the Lydian kingdom was able to grow in power, and the Lydians themselves appear to have adopted Cimmerian military practices such as the use of mounted cavalry, with the Lydians fighting using long spears and archers, both on horseback.[271]

Around c. 635 BC,[272] and with Neo-Assyrian approval,[273] the Scythians under their king Madyes conquered Urartu,[274][275] entered Central Anatolia,[39] and defeated the Cimmerians and Treres.[276] This final defeat of the Cimmerians was carried out by the joint forces of Madyes's Scythians, whom Strabo of Amasia credits with expelling the Treres from Asia Minor, and of the Lydians led by their king Alyattes,[277] who was himself the son of Sadyattes as well as the grandson of Ardys and the great-grandson of Gyges, whom Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Polyaenus of Bithynia claim permanently defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat.[278]

In an inscription from after c. 638 BC, Ashurbanipal thanked the god Marduk for the fate which had struck Sandakšatru, suggesting that he had experienced a horrifying death not unlike his father's.[279]

The Cimmerians completely disappeared from history following this final defeat,[128][68] and they were soon assimilated by the various populations and polities of Anatolia, such as Lydia, Media, and Pteria.[202] It was also around this time that the last still-existing Syro-Hittite and Aramaean states in Anatolia, which had been either independent or vassals of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Phrygia, Urartu, or of the Cimmerians, also disappeared, although the exact circumstances of their end are still very uncertain.[241]

Scythian power in West Asia thus reached its peak under Madyes, with the West Asian territories ruled by the Scythian kingdom extending from the Halys river in Anatolia in the west to the Caspian Sea and the eastern borders of Media in the east, and from Transcaucasia in the north to the northern borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the south.[280][272][281] And, following the defeat of the Cimmerians and the disappearance of these states, it was the new Lydian Empire of Alyattes which became the dominant power of Anatolia,[204][282] while the city of Sinope was re-founded[275][283] by the Milesian Greek colonists Kōos and Krētinēs.[284][285]

Impact in West Asia

[edit]The inroads of the Cimmerians and the Scythians into West Asia over the course of the 8th to 7th centuries BC had destabilised the political balance which had prevailed in the region between the dominant great powers of Assyria, Urartu, and Phrygia,[286] and also caused the decline and destruction of several of these states' power, consequently led to the rise of multiple new powers such as the empires of the Medes and Lydians,[287] thus irreversibly changing the geopolitical situation of West Asia.[39][288]

The Cimmerian and Scythian activities in West Asia also hampered the development of trade, and overland trade routes in the region such as the Great Khorasan Road likely became dangerous to use, while also preventing the formation of new trade routes.[227]

These Cimmerian and Scythian activities also influenced the developments in West Asia through the spread of the steppe nomad military technology brought by them into this region, and which were disseminated during the periods of their respective hegemonies in West Asia.[286]

Possible migration in Europe

[edit]It has been hypothesised that some Cimmerians might have migrated into Eastern, Southeast and Central Europe,[289] although this identification is presently considered very uncertain.[290]

Proponents of a Cimmerian migration into southeastern Europe suggest that it affected as far as Thrace, where between 700 and 650 BC the Edoni allied with the Cimmerians to expand their territories by occupying Mygdonia and the area up to the Axios river at the expense of the Sintians and the Siropaiones.[291]

The proponents of this hypothesis of a Cimmerian invasion also suggest that it would have also affected south-eastern Illyria, where raids by Cimmerians allied to Thracians ended the hegemony of Illyrian tribes around 650 BC, and possibly into Epirus as well, where distinctive Cimmerian horse trappings were found offered in dedication at the temple of Dodona.[292]

Legacy

[edit]Ancient

[edit]In Europe

[edit]The peoples of the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk complex of which the Cimmerians were part of introduced the use of trousers into Central Europe, whose local native populations did not wear trousers before the arrival of the first wave of steppe nomads of Central Asian origin into Europe.[32]

In West Asia

[edit]The inroads of the Cimmerians and the Scythians into West Asia over the course of the 8th to 7th centuries BC, which were early precursors of the later invasions of West Asia by steppe nomads such as the Huns, various Turkic peoples, and the Mongols, in Late Antiquity and the Mediaeval Period,[293] had destabilised the political balance which had prevailed in the region between the dominant great powers of Assyria, Urartu, and Phrygia,[286] and also caused the decline and destruction of several of these states' power, consequently to the rise of multiple new powers such as the empires of the Medes and Lydians,[287] thus irreversibly changing the geopolitical situation of West Asia.[294]

These Cimmerians and Scythians also influenced the developments in West Asia through the spread of the steppe nomad military technology brought by them into this region, and which were disseminated during the periods of their respective hegemonies in West Asia.[286]

After the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and following the conquest of the Neo-Babylonian Empire which had succeeded it by the Persian Achaemenids, the Babylonian scribes of the Achaemenid Persian Empire used the name of the Cimmerians (Gimirri: 𒆳𒄀𒈪𒅕[10] and 𒆳𒄀𒂆𒊑[11]) in Neo-Babylonian Akkadian to indiscriminately and anachronistically refer to all of the nomads of the steppes, including both the Pontic Scythians and the Central Asian Saka, because of their similar nomadic lifestyles.[12] The Achaemenid Babylonian scribes therefore designated the bows used by Saka mounted archers as lit. 'Cimmerian bows' (𒄑𒉼 𒄀𒂆𒊒𒄿𒋾, qaštu Gimirrîti and 𒄑𒉼𒈨 𒄀𒂆𒊒𒀪, qašātu Gimirruʾ).[96] The Greeks similarly used the name of the Scythians as a generalising term for all stepp nomads, and the Byzantines later also similarly used it as an archaising term to designate the Huns, Slavs and other eastern peoples centuries after the actual Scythians had disappeared.[295][92]

The Cimmerians appear in the Hebrew Bible under the name of Gōmer (Hebrew: גֹּמֶר; Ancient Greek: Γαμὲρ, romanized: Gamèr), where Gōmer is closely linked to ʾAškənāz (אשכנז), that is to the Scythians.[296]

Due to the fear that the Cimmerian invasions caused among the Greeks of Ionia, they were remembered in Greek tradition, and an inscription from 283 BC mentioned that the Greek city-states of Samos and Priene were still engaging in a lawsuit disputing the territory of Batinetis which had been abandoned during the Cimmerian invasion of Ionia and Aeolia.[297]

In the mediaeval period, Armenian tradition assigned the name of the Biblical Gōmer to the Konya Plain and to Cappadocia, which was therefore called Gamirkʻ (Գամիրք) in the Armenian language.[183]

In Graeco-Roman literature

[edit]In Homer's Odyssey

[edit]The first mention of the Cimmerians in Graeco-Roman literature dates from the 8th century BC in Homer's Odyssey,[298] which describes them as a people living in a city located at the entrance of Hades beyond the western shore of the Oceanus river which encircles the world, in a land towards which Odysseus sailed to obtain an oracle from the soul of the seer Tiresias, and which was covered with mists and clouds and therefore remained permanently deprived of sunlight although the Sun-god Helios sets there.[299]

This mention of the Cimmerians in the Odyssey was purely poetic and combined fantasy with records of real events, and naturalism with supernatural elements, and therefore contained no reliable information about the real Cimmerian people.[300] This image was created as a poetic opposite of the Laestrygonians and Aethiopians who, in ancient Greek mythology, lived in a permanently sunlit land on the eastern borders of the world.[301][302] Due to this location, the Ancient Greek name of the Cimmerians was identified with the word for mist, kemmeros (κέμμερος).[302]

Homer's passage relating to the Cimmerians had however used as its source the Argonautic myth, which dealt with the region of the Black Sea and the country of Colchis, on whose eastern borders the Cimmerians were still living in the 8th century BC.[303] Thus, Homer's source on the Cimmerians was the Argonautic myth, which itself recorded of their existence when they were still living in northern Transcaucasia:[304][42] the location of the Cimmerians as recorded by the Argonautic myth corresponds to the same one recorded by the late 7th century BC poem Arimaspeia by Aristeas of Proconessus and the later writings of Herodotus of Halicarnassus,[305] who both described the Cimmerians as having once dwelt in the steppe to the immediate north of the Caspian Sea,[305] with the Araxes (Volga) river forming their eastern border separating them from the Scythians.[45]

In the 6th century BC

[edit]The Greeks living in Anatolia in the 6th century BC still evoked the memory of the Cimmerians with fear a century after their disappearance.[87]

The Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus, drawing from information acquired by the Persian army during its invasion of Scythia in 513 BC, later started the tradition of locating Homer's Cimmerians and "Cimmerian" places (such as a "Cimmerian city") in the Scythian-dominated Pontic Steppe[306] between the Araxes and the Bosporus.[43]

According to Herodotus of Halicarnassus

[edit]Herodotus of Halicarnassus wrote a legendary account, partly based on Hecataeus's narrative,[43] of the arrival of the Scythians into the lands of the Cimmerians:[307]

- after the Scythians were expelled from Central Asia by the Massagetae, they moved to the west across the Araxes, and took possession of the Cimmerians' lands after chasing them away;

- the approach of the Scythians led to a civil war among the Cimmerians because the "royal tribe" wanted to remain in their lands and defend themselves from the invaders, while the rest of the people saw no use in fighting and preferred to flee;

- since neither side could be persuaded by the other, the "royal tribe" divided themselves into two equally numerous sides that fought each other till death, after which the commoners buried them by the Tyras river.

Basing himself on Greek folk tales from the city of Tyras, Herodotus claimed the tombs of the Cimmerian princes could still be seen in his days near the Tyras river.[210]

Herodotus also referred to the presence of several "Cimmerian" toponyms as existing in the Bosporan region, such as:[47][48][54]

- "Cimmerian walls" (Ancient Greek: Κιμμέρια τείχεα, romanized: Kimméria teíkhea),

- the "Cimmerian ferry" (Ancient Greek: πορθμήια Κιμμέρια, romanized: porthmḗia Kimméria),

- the "country of Cimmeria" (Ancient Greek: χώρη Κιμμέρια, romanized: khṓrē Kimméria),

- and the "Cimmerian Bosporus" (Ancient Greek: Βόσπορος Κιμμέριος, romanized: Bósporos Kimmérios).

Herodotus likely used Bosporan Greek folk tales as source for these claims, although some of the "Cimmerian" toponyms in the Bosporan region might have originated from a genuine Cimmerian presence in this area.[308][47][46]

The story of the fratricidal war of the Cimmerian "royal tribe," that is of the defeat and destruction of its ruling class, is contradicted by how powerful the Cimmerians were according to the Assyrian records contemporaneous with their presence in West Asia. Another inconsistency in Herodotus's description of the flight of the Cimmerians is the direction through which they retreated: according to this narrative, the Cimmerians moved from the Pontic Steppe to the east into Caucasia to flee from the Scythians, who were themselves moving from the east into the Pontic Steppe.[44]

These inconsistencies suggest that Herodotus's narrative of an eastern flight of the Cimmerians was a later folk tale invented by Greek colonists on the north shore of the Black Sea to explain the existence of ancient tombs, reflecting the motif of assigning old tombs and buildings with mythical heroes or with lost ancient valiant peoples, similarly to how the Greeks within Greece proper claimed similar remains had been built by the Pelasgi and the Cyclops,[47][44][184] or how later Ossetian tradition recounted the death of the Narts.[309]

Herodotus's account of the Cimmerians' flight contracted the actual events into a more condensed story where they moved south by following the shore of the Black Sea under the leadership of Lygdamis, while their Scythian pursuers followed the Caspian Sea's coast, thus leading the Cimmerians into Anatolia and the Scythians into Media.[79][74][310] While Cimmerian activities in Anatolia and Scythian activities in Media are attested, the claim that the Scythians arrived in Media while pursuing the Cimmerians is unsupported by evidence,[79] and the arrival of the Scythians in West Asia about 40 years after that of the Cimmerians suggests that there is no available evidence to the later Graeco-Roman account of the Cimmerians crossing the Caucasus and moving south into West Asia under pressure from the Scythians migrating into their territories.[64][65]

Moreover, Herodotus's account also ignored the earlier Cimmerian activities in West Asia during the reigns of Sargon II to the ascension of Ashurbanipal, including the two separate invasions of Lydia, and instead contracted them into a single event during which Lydgamis led the Cimmerians from the steppes into Anatolia to sack Sardis under the reign of Ardys.[310][311]

In later Graeco-Roman literature

[edit]Drawing on similar older Graeco-Roman sources, Strabo of Amasia claimed that the Cimmerian Bosporus had been named after the Cimmerians,[312] who were once powerful in that region, and that the city of "Kimmerikon" (Ancient Greek: Κιμμερικόν; Latin: Cimmericum) used a trench and a mount to close the isthmus.[67] According to Strabo, there was in Crimea a mountain called Kimmerios (Ancient Greek: Κιμμέριος; Latin: Cimmerius), which had also been named because the Cimmerians had once ruled the region of the Bosporus.[313]

In the 4th century BC, a town called Cimmeris was established in the Sindic Chersonese.[313]

Homer's description of the Cimmerians as living deprived from sunlight and close to the entrance of Hades influenced later Graeco-Roman authors who, writing centuries after the disappearance of the historical Cimmerians, conceptualised of this people as the one described by Homer,[314] and therefore assigned to them various fantastical locations and histories:[42]

- some Classical writers considered the western Mediterranean Sea as having been the setting of the Odyssey, and therefore located the Cimmerians in this region:[314]

- Ephorus of Cyme in the 4th century BC located the Cimmerians near the Campanian city of Cumae in Magna Graecia in southern Italy, where

- following Ephorus's narrative, Strabo and Pliny claimed that a "Cimmerian city" (Latin: Cimmerium oppidum) was located near the Lake Avernus in Italy:[46][285]

- Strabo, himself citing Ephorus, claimed that, because the inhabitants of Magna Graecia placed the setting of the Odyssey's Nekyia around Lake Arvernus, they also depicted the Cimmerians as a people living in this area in underground houses tunnels around the nearby Ploutonion (oracle of the dead) where was believed to be the entrance to Hades; these "underground Cimmerians" visited each other using tunnels through which they would also admit strangers to the also underground oracle: according to this legend, these "underground Cimmerians" had an ancestral custom according to which they should never see the sun and were allowed to go out only at night;[314][315]

- following Ephorus's narrative, Strabo and Pliny claimed that a "Cimmerian city" (Latin: Cimmerium oppidum) was located near the Lake Avernus in Italy:[46][285]

- Ephorus of Cyme in the 4th century BC located the Cimmerians near the Campanian city of Cumae in Magna Graecia in southern Italy, where

- Hecataeus of Abdera claimed that the Cimmerians lived in a "Cimmerian city" (Ancient Greek: Κιμμερὶς πόλις, romanized: Kimmerìs pólis) located in Hyperborea in the north;[67][314][315]

- Aeschylus mentioned a "Cimmerian isthmus"[67] and a "Cimmerian land" in his work, Prometheus Bound;[220]

- Posidonius of Apamea, while trying to explain where the Cimbri came from, elaborated some speculative interpretations of their origins:[2][316][315]

- drawing on the similarity of the names of the Cimmerians and Cimbri, Posidonius equated these two peoples with each other, and then claimed that the Cimmerians who passed into West Asia were merely a small body of exiles, while the bulk of the Cimmerians lived in the thickly wooded and sun-less far north, between the shores of the Oceanus and the Hercynian Forest, and were the same people known as the Cimbri;[317]

- Since the Cimmerians and Cimbri had similar names, and they were also both perceived by the Graeco-Romans as ferocious and barbarian peoples who caused death and destruction, the ancient Greek literary traditions progressively equated and identified them with each other.[315]

- Posidonius then, in turn, argued that the Cimmerian Bosporus (Kerch Strait) had been named after the Cimbri, whom he claimed the Greeks called "Cimmerians."[64]

- Plutarch criticised Posidonius's theories as being based on conjecture rather than on concrete historical evidence.[318]

- Strabo and Diodorus of Sicily, using Posidonius as their sources, also equated the Cimmerians and the Cimbri.[318]

- drawing on the similarity of the names of the Cimmerians and Cimbri, Posidonius equated these two peoples with each other, and then claimed that the Cimmerians who passed into West Asia were merely a small body of exiles, while the bulk of the Cimmerians lived in the thickly wooded and sun-less far north, between the shores of the Oceanus and the Hercynian Forest, and were the same people known as the Cimbri;[317]

- Crates of Mallos, in the 2nd century BC, wrote a commentary on the Iliad and the Odyssey in which he assumed that Homer did not know of the Cimmerians and therefore renamed them in his text as the "Cerberians" (Ancient Greek: Κερβέριοι, romanized: Kerbérioi) because of the Homeric location of this people at the entrance of Hades where dwelt Cerberus.[97]

- According to the Etymologicum Magnum, Proteas of Zeugma renamed the Cimmerians the Kheimerioi (Ancient Greek: Χειμέριοι), lit. 'winter people'.[97]

The eastern Greeks living on the north shore of the Black Sea, who were familiar with the Cimmerian activities in Asia, nevertheless criticised these western locations assigned to the Cimmerians.[46]

Modern

[edit]Basing themselves on the location of the Cimmerians in the Odyssey as living on the western shore of the Oceanus, some earlier modern interpretations tried to locate them in the far north of Europe, such as in Britain and Jutland.[319]