Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Decapitation

View on Wikipedia| Decapitation | |

|---|---|

| |

| The Beheading of Saint Paul. Painting by Enrique Simonet in 1887, Málaga Cathedral | |

| Causes | Deliberate (executions, murder or homicide, suicide); unintended (accidents) |

| Prognosis | Invariably fatal |

Decapitation is the total separation of the head from the body. Such an injury is always fatal to humans and all vertebrate animals, since it deprives the brain of oxygenated blood by way of severing through the jugular vein and common carotid artery, while all other organs are deprived of the involuntary functions that are needed for the body to function. The term beheading refers to the act of deliberately decapitating a person, either as a means of murder or as an execution; it may be performed with an axe, sword, or knife, or by mechanical means such as a guillotine. An executioner who carries out executions by beheading is sometimes called a headsman.[1] Accidental decapitation can be the result of an explosion,[2] a car or industrial accident, improperly administered execution by hanging or other violent injury. The national laws of Saudi Arabia and Yemen[3] permit beheading. Under Sharia, which exclusively applies to Muslims, beheading is also a legal punishment in Zamfara State, Nigeria.[4] In practice, Saudi Arabia is the only country that continues to behead its offenders regularly as a punishment for capital crimes. Cases of decapitation by suicidal hanging,[5] suicide by train decapitation[6][7] and by guillotine[8] are known.

Less commonly, decapitation can also refer to the removal of the head from a body that is already dead. This might be done to take the head as a trophy, as a secondary stage of an execution by hanging, for public display, to make the deceased more difficult to identify, for cryonics, or for other, more esoteric reasons.[9][10]

Etymology

[edit]The word decapitation has its roots in the Late Latin word decapitare. The meaning of the word decapitare can be discerned from its morphemes de- (down, from) + capit- (head).[11] The past participle of decapitare is decapitatus[12] which was used to create decapitatio, the noun form of decapitatus, in Medieval Latin, whence the French word décapitation was produced.[12]

History

[edit]

Humans have practiced capital punishment by beheading for millennia. The Narmer Palette (c. 3000 BCE) shows the first known depiction of decapitated corpses. The terms "capital offence", "capital crime", "capital punishment", derive from the Latin caput, "head", referring to the punishment for serious offences involving the forfeiture of the head; i.e. death by beheading.[13]

Some cultures, such as ancient Rome and Greece, regarded decapitation as the most honorable form of death.[14] In the Middle Ages, many European nations continued to reserve the method only for nobles and royalty.[15] In France, the French Revolution made it the only legal method of execution for all criminals regardless of class, one of the period's many symbolic changes.[14]

Others have regarded beheading as dishonorable and contemptuous, such as the Japanese troops who beheaded prisoners during World War II.[14] In recent times, it has become associated with terrorism.[14]

If a headsman's axe or sword is sharp and his aim is precise, decapitation is quick and thought to be a relatively painless form of death. If the instrument is blunt or the executioner is clumsy, repeated strokes might be required to sever the head, resulting in a prolonged and more painful death. Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex,[16] and Mary, Queen of Scots[17] required three strikes at their respective executions. The same could be said for the execution of Johann Friedrich Struensee, favorite of the Danish queen Caroline Matilda of Great Britain. Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury, is said to have required up to 10 strokes before decapitation was achieved.[18] This particular story may, however, be apocryphal, as highly divergent accounts exist. Historian and philosopher David Hume, for example, relates the following about her death:[19]

She refused to lay her head on the block, or submit to a sentence where she had received no trial. She told the executioner, that if he would have her head, he must win it the best way he could: and thus, shaking her venerable grey locks, she ran about the scaffold; and the executioner followed her with his axe, aiming many fruitless blows at her neck before he was able to give the fatal stroke.

To ensure that the blow would be fatal, executioners' swords usually were blade-heavy two-handed swords. Likewise, if an axe was used, it almost invariably was wielded with both hands.

Physiological aspects

[edit]Physiology of death by decapitation

[edit]Decapitation is quickly fatal to humans and most animals. Unconsciousness occurs within seconds without circulating oxygenated blood (brain ischemia).[20] Cell death and irreversible brain damage occur after 3–6 minutes with no oxygen, due to excitotoxicity. Some anecdotes suggest more extended persistence of human consciousness after decapitation,[21] but most doctors consider this unlikely and consider such accounts to be misapprehensions of reflexive twitching rather than deliberate movement, since deprivation of oxygen must cause nearly immediate coma and death ("[Consciousness is] probably lost within 2–3 seconds, due to a rapid fall of intracranial perfusion of blood").[22]

A laboratory study testing for humane methods of euthanasia in awake animals used EEG monitoring to measure the time duration following decapitation for rats to become fully unconscious, unable to perceive distress and pain. It was estimated that this point was reached within 3–4 seconds, correlating closely with results found in other studies on rodents (2.7 seconds, and 3–6 seconds).[23][24][25] The same study also suggested that the massive wave which can be recorded by EEG monitoring approximately one minute after decapitation ultimately reflects brain death. Other studies indicate that electrical activity in the brain has been demonstrated to persist for 13 to 14 seconds following decapitation (although it is disputed as to whether such activity implies that pain is perceived),[26] and a 2010 study reported that decapitation of rats generated responses in EEG indices over a period of 10 seconds that have been linked to nociception across a number of different species of animals, including rats.[27]

Some animals (such as cockroaches) can survive decapitation and die not because of the loss of the head directly, but rather because of starvation.[28] A number of other animals, including snakes, and turtles, have also been known to survive for some time after being decapitated, as they have slower metabolisms and their nervous systems can continue to function at some capacity for a limited time even after connection to the brain is lost, responding to any nearby stimulus.[29][30] In addition, the bodies of chickens and turtles may continue to move temporarily after decapitation.[31]

Although head transplantation by the reattachment of blood vessels has seen some very limited success in animals,[32] a fully functional reattachment of a severed human head (including repair of the spinal cord, muscles, and other critically important tissues) has not yet been achieved.

Technology

[edit]Guillotine

[edit]

Early versions of the guillotine included the Halifax Gibbet, which was used in Halifax, England, from 1286 until the 17th century, and the "Maiden", employed in Edinburgh from the 16th through the 18th centuries.

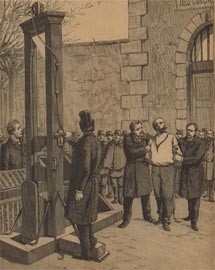

The modern form of the guillotine was invented shortly before the French Revolution with the aim of creating a quick and painless method of execution requiring little skill on the part of the operator. Decapitation by guillotine became a common mechanically assisted form of execution.

The French observed a strict code of etiquette surrounding such executions. For example, a man named Legros, one of the assistants at the execution of Charlotte Corday, was imprisoned for three months and dismissed for slapping the face of the victim after the blade had fallen in order to see whether any flicker of life remained.[33] The guillotine was used in France during the French Revolution and remained the normal judicial method in both peacetime and wartime into the 1970s, although the firing squad was used in certain cases. France abolished the death penalty in 1981.

The guillotine was also used in Algeria before the French relinquished control of it, as shown in Gillo Pontecorvo's film The Battle of Algiers.

Fallbeil

[edit]

Many German states had used a guillotine-like device known as a Fallbeil ("falling axe") since the 17th and 18th centuries, and decapitation by guillotine was the usual means of execution in Germany until the abolition of the death penalty in West Germany in 1949. It was last used in communist East Germany in 1966.

In Nazi Germany, the Fallbeil was reserved for common criminals and people convicted of political crimes, including treason. Members of the White Rose resistance movement, a group of students in Munich that included siblings Sophie and Hans Scholl, were executed by decapitation.

Contrary to popular myth, executions were generally not conducted face-up, and chief executioner Johann Reichhart was insistent on maintaining "professional" protocol throughout the era, having administered the death penalty during the earlier Weimar Republic. Nonetheless, it is estimated that some 16,500 persons were guillotined in Germany and Austria between 1933 and 1945, a number that includes resistance fighters both within Germany itself and in countries occupied by Nazi forces. As these resistance fighters were not part of any regular army, they were considered common criminals and were in many cases transported to Germany for execution. Decapitation was considered a "dishonorable" death, in contrast to execution by firing squad.[citation needed]

Historical practices by nation

[edit]Africa

[edit]Congo

[edit]In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the conflict and ethnic massacre between local army and Kamuina Nsapu rebels has caused several deaths and atrocities such as rape and mutilation. One of them is decapitation, both a fearsome way to intimidate victims as well as an act that may include ritualistic elements. According to a UN report from Congolese refugees, they believed the Bana Mura and Kamuina Nsapu militias have "magical powers" as a result of drinking the blood of decapitated victims, making them invincible.[34]

Besides the massive decapitations (like the beheading of 40 members of the State Police), a globally notorious case happened in March 2017 to Swedish politician Zaida Catalán and American UN expert Michael Sharp, who were kidnapped and executed during a mission near the village of Ngombe in Kasaï Province. The UN was reportedly horrified when video footage of the executions surfaced in April that same year, where some grisly details led to assume ritual components of the beheading: the perpetrators first cut the hair of both victims, and then one of them beheaded Catalán only, because it would "increase his power",[35] which may be linked to the fact that Congolese militias are particularly brutal in their acts of violence toward women and children.[36]

In the trial that followed investigations after the bodies were discovered, and according to a testimony of a primary school teacher from Bunkonde, near the village of Moyo Musuila where the executions took place, he witnessed a teenage militant carrying the young woman's head,[37] but despite the efforts of the investigation, the head was never found. According to a report published on 29 May 2019, the Monusco peacekeeping military mission led by Colonel Luis Mangini, in the search for the missing remains, arrived to a ritual place in Moyo Musila where "parts of bodies, hands and heads" were cut and used for rituals,[38] where they lost track of the victim's head.

Asia

[edit]Azerbaijan

[edit]During the 2016 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes, Yazidi-Armenian serviceman Kyaram Sloyan was decapitated by Azerbaijani servicemen.[39][40][41]

Several reports of decapitation, along with other types of mutilation of Armenian POWs by Azerbaijani soldiers, emerged in 2020 during the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.[42]

China

[edit]

In traditional China, decapitation was considered a more severe form of punishment than strangulation, although strangulation caused more prolonged suffering. This was because in Confucian tradition, a person's body was a gift from their parents, and so it was therefore disrespectful to their ancestors to return their bodies to the grave dismembered. The Chinese, however, had other punishments, such as dismembering the body into multiple pieces (similar to the English quartering). In addition, there was also a practice of cutting the body at the waist, which was a common method of execution before being abolished in the early Qing dynasty due to the lingering death it caused. In some tales, people did not die immediately after decapitation.[43][44][45][46]

India

[edit]The British officer John Masters recorded in his autobiography that Pathans in British India during the Anglo-Afghan Wars would behead enemy soldiers who were captured, such as British and Sikh soldiers.[47][48][49][50]

The Execution of Sambhaji was a significant event in 17th-century Deccan India, where the second Maratha King was put to death by order of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. The conflicts between the Mughals and the Deccan Sultanates, which resulted in the downfall of the Sultanates, paved the way for tensions between the Marathas and the Mughals. Aurangzeb was drawn to Southern India due to the vanquished rebel Akbar fleeing to the Maratha monarch, Sambhaji. The Maratha King was then captured by the Mughal general Muqarrab Khan. Sambhaji and his minister Kavi Kalash were then taken to Tulapur, where they were tortured to death.

Japan

[edit]

In Japan, decapitation was a common punishment, sometimes for minor offences. Samurai were often allowed to decapitate soldiers who had fled from battle, as it was considered cowardly. Decapitation was historically performed as the second step in seppuku (ritual suicide by disembowelment). After the victim had sliced his own abdomen open, another warrior would strike his head off from behind with a katana to hasten death and to reduce the suffering. The blow was expected to be precise enough to leave intact a small strip of skin at the front of the neck—to spare invited and honored guests the indelicacy of witnessing a severed head rolling about, or towards them; such an occurrence would have been considered inelegant and in bad taste. The sword was expected to be used upon the slightest sign that the practitioner might yield to pain and cry out—avoiding dishonor to him and to all partaking in the privilege of observing an honorable demise. As skill was involved, only the most trusted warrior was honored by taking part. In the late Sengoku period, decapitation was performed as soon as the person chosen to carry out seppuku had made the slightest wound to his abdomen.

Decapitation (without seppuku) was also considered a very severe and degrading form of punishment. One of the most brutal decapitations was that of Sugitani Zenjubō (杉谷善住坊), who attempted to assassinate Oda Nobunaga, a prominent daimyō, in 1570.[disputed – discuss] After being caught, Zenjubō was buried alive in the ground with only his head out, and the head was slowly sawn off with a bamboo saw by passers-by for several days (punishment by sawing; nokogiribiki (鋸挽き).[51] These unusual punishments were abolished in the early Meiji era. A similar scene is described in the last page of James Clavell's book Shōgun[dubious – discuss].

Korea

[edit]Historically, decapitation had been the most common method of execution in Korea, until it was replaced by hanging in 1896. Professional executioners were called mangnani (망나니) and they were volunteered from death rows.[citation needed]

Thailand

[edit]Decapitation was the main method of execution in Thailand, until it was replaced by shooting in 1934.

Vietnam

[edit]

Execution by beheading was one of the most common forms of execution in Vietnam under the feudal system. This form of execution still existed in the South Vietnam regime until 1962.

Europe

[edit]Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]During the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995) there were a number of ritual beheadings of Serbs and Croats who were taken as prisoners of war by mujahideen members of the Bosnian Army. At least one case is documented and proven in court by the ICTY where mujahedin, members of 3rd Corps of Army BiH, beheaded Bosnian Serb Dragan Popović.[52][53]

Britain

[edit]

In British history, beheading was typically used for noblemen, while commoners would be hanged; eventually, hanging was adopted as the standard means of non-military executions. The last actual execution by beheading was of Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat on 9 April 1747, while a number of convicts were beheaded posthumously up to the early 19th century.[55] (Typically traitors were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, a method which had already been discontinued.) Beheading was degraded to a secondary means of execution, including for treason, with the abolition of drawing and quartering in 1870 and finally abolished by the Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1973.[56][57] One of the most notable executions by decapitation in Britain was that of King Charles I of England, who was beheaded outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall in 1649, after being captured by parliamentarians during the English Civil War and tried for treason.[58][59]

In England, a bearded axe was used for beheading, with the blade's edge extending downwards from the tip of the shaft.[citation needed]

Celts

[edit]The Celts of western Europe long pursued a "cult of the severed head", as evidenced by both Classical literary descriptions and archaeological contexts.[60] This cult played a central role in their temples and religious practices and earned them a reputation as head hunters among the Mediterranean peoples. Diodorus Siculus, in his 1st-century Historical Library (5.29.4) wrote the following about Celtic head-hunting:

They cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The blood-stained spoils they hand over to their attendants and striking up a paean and singing a song of victory; and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses, just as do those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm in cedar oil the heads of the most distinguished enemies, and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that for this head one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a large sum of money. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold.

Both the Greeks and Romans found the Celtic decapitation practices shocking and the latter put an end to them when Celtic regions came under their control.

According to Paul Jacobsthal, "Amongst the Celts the human head was venerated above all else, since the head was to the Celt the soul, centre of the emotions as well as of life itself, a symbol of divinity and of the powers of the other-world."[61] Arguments for a Celtic cult of the severed head include the many sculptured representations of severed heads in La Tène carvings, and the surviving Celtic mythology, which is full of stories of the severed heads of heroes and the saints who carry their own severed heads, right down to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, where the Green Knight picks up his own severed head after Gawain has struck it off in a beheading game, just as Saint Denis carried his head to the top of Montmartre.[62][63]

A further example of this regeneration after beheading lies in the tales of Connemara's Saint Féchín, who after being beheaded by Vikings carried his head to the Holy Well on Omey Island and on dipping it into the well placed it back upon his neck and was restored to full health.[64]

Classical antiquity

[edit]

Pothinus matched Mark Antony in crime:

They slew the noblest Romans of their time.

The helpless victims they decapitated,

An act of infamy with shame related.

One head was Pompey's, who brought triumphs home,

The other Cicero's, the voice of Rome.

The ancient Greeks and Romans regarded decapitation as a comparatively honorable form of execution for criminals. The traditional procedure, however, included first being tied to a stake and whipped with rods. Axes were used by the Romans, and later swords, which were considered a more honorable instrument of death. Those who could verify that they were Roman citizens were to be beheaded, rather than undergoing crucifixion. In the Roman Republic of the early 1st century BC, it became the tradition for the severed heads of public enemies—such as the political opponents of Marius and Sulla—to be publicly displayed on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum after execution. Perhaps the most famous beheading was that of Cicero who, on instructions from Mark Antony, had his hands (which had penned the Philippicae against Antony) and his head cut off and nailed up for display in this manner.

Archaeological evidence of Roman-period executions by decapitation has also been found in the provinces. In Israel, seven cases of decapitation have been discovered, all dating to the Roman period and involving Jewish individuals.[65] An additional case, uncovered in Jerusalem, appears to date from the early 1st century BCE and may be linked to the Judean Civil War during the reign of Alexander Jannaeus.[65]

France

[edit]In France, until the abolition of capital punishment in 1981, the main method of execution had been by beheading by means of the guillotine. Other than a small number of military cases in which a firing squad was used (including that of Jean Bastien-Thiry), the guillotine was the only legal method of execution from 1791, when it was introduced by the Legislative Assembly during the last days of the kingdom French Revolution, until 1981. Before the revolution, beheading had typically been reserved for noblemen and carried out manually. In 1981, President François Mitterrand abolished capital punishment and issued commutations for those whose sentences had not been carried out.

The first person executed by the guillotine in France was highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier in April 1792. The last execution was of murderer Hamida Djandoubi, in Marseille, in 1977.[66] Throughout its extensive overseas colonies and dependencies, the device was also used, including on St Pierre in 1889 and on Martinique as late as 1965.[67]

Nordic countries

[edit]In Nordic countries, decapitation was the usual means of carrying out capital punishment. Noblemen were beheaded with a sword, and commoners with an axe. The last executions by decapitation in Finland in 1825, Norway in 1876, Faroe Islands in 1609, and in Iceland in 1830 were carried out with axes. The same was the case in Denmark in 1892. Sweden continued the practice for a few decades, executing its second to last criminal—mass murderer Johan Filip Nordlund—by axe in 1900. It was replaced by the guillotine, which was used for the first and only time on Johan Alfred Ander in 1910.

Finland's official beheading axe resides today at the Museum of Crime in Vantaa. It is a broad-bladed two-handed axe. It was last used when murderer Tahvo Putkonen was executed in 1825, the last execution in peacetime in Finland.[68]

Spain

[edit]

In Spain executions were carried out by various methods including strangulation by the garrotte. In the 16th and 17th centuries, noblemen were sometimes executed by means of beheading. Examples include Anthony van Stralen, Lord of Merksem, Lamoral, Count of Egmont and Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horn. They were tied to a chair on a scaffold. The executioner used a knife to cut the head from the body. It was considered to be a more honourable death if the executioner started with cutting the throat.[69]

Middle East

[edit]Iran

[edit]Iran, since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, has alleged it uses beheading as one of the methods of punishment.[70][71]

Iraq

[edit]

Though not officially sanctioned, legal beheadings were carried out against at least 50 prostitutes and pimps under Saddam Hussein as late as 2000.[72]

Beheadings have emerged as another terror tactic especially in Iraq since 2003.[73] Civilians have borne the brunt of the beheadings, although U.S. and Iraqi military personnel have also been targeted. After kidnapping the victim, the kidnappers typically make some sort of demand of the government of the hostage's nation and give a time limit for the demand to be carried out, often 72 hours. Beheading is often threatened if the government fails to heed the wishes of the hostage takers. Sometimes, the beheadings are videotaped and made available on the Internet. One of the most publicized of such executions was that of Nick Berg.[74]

Judicial execution is practiced in Iraq, but is generally carried out by hanging.

Saudi Arabia

[edit]Saudi Arabia has a criminal justice system based on Shari'ah law reflecting a particular state-sanctioned interpretation of Islam. Crimes such as rape, murder, apostasy, and sorcery[75] are punishable by beheading.[76] It is usually carried out publicly by beheading with a sword.

A public beheading will typically take place around 9am. The convicted person is walked into the square and kneels in front of the executioner. The executioner uses a sword to remove the condemned person's head from their body at the neck with a single strike.[77] After the convicted person is pronounced dead, a police official announces the crimes committed by the beheaded alleged criminal and the process is complete. The official might announce the same before the actual execution. This is the most common method of execution in Saudi Arabia.[78]

According to Amnesty International, at least 79 people were executed in Saudi Arabia in 2013.[79] Foreigners are not exempt, accounting for "almost half" of executions in 2013.[79]

In 2015 Ashraf Fayadh (born 1980), a Saudi Arabian poet, was sentenced to be beheaded, but his sentence was later reduced to eight years in prison and 800 lashes, for apostasy.

Syria

[edit]The Syrian government employs hanging as its method of capital punishment. However, the terrorist organisation known as the Islamic State, which controlled territory in much of eastern Syria, had regularly carried out beheadings of people.[80] Syrian rebels attempting to overthrow the Syrian government have been implicated in beheadings too.[81][82][83]

North America

[edit]Mexico

[edit]

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, Ignacio Allende, José Mariano Jiménez and Juan Aldama were tried for treason, executed by firing squad and beheaded during the Mexican independence in 1811. Their heads were on display on the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas, in Guanajuato.

During the Mexican Drug War, some Mexican drug cartels turned to decapitation and beheading of rival cartel members as a method of intimidation.[84] This trend of beheading and publicly displaying the decapitated bodies was started by the Los Zetas, a criminal group composed by former Mexican special forces operators, trained in the infamous US Army School of the Americas, in torture techniques and psychological warfare.[85][86][87][88][89][90]

United States

[edit]The United States government has never employed beheading as a legal method of execution. However, beheading has sometimes been used in mutilations of the dead, particularly during the time of slavery, such as Nat Turner, who led a rebellion against slavery. When caught, he was publicly hanged, flayed, and beheaded. This was a technique used by many enslavers to discourage the "frequent bloody uprisings" that were carried out by "kidnapped Africans". While bodily dismemberment of various kinds was employed to instill terror, Dr. Erasmus D. Fenner noted postmortem decapitation was particularly effective.[91]

During the Vietnam War, as a terror tactic, "some American troops hacked the heads off... dead [Vietnamese] and mounted them on pikes or poles".[92] Correspondent Michael Herr noted "thousands" of photo-albums made by US soldiers "all seemed to contain the same pictures": "the severed head shot, the head often resting on the chest of the dead man or being held up by a smiling Marine, or a lot of the heads, arranged in a row, with a burning cigarette in each of the mouths, the eyes open". Some of the victims were "very young".[93]

General George Patton IV, son of the famous WWII general George S. Patton, was known for keeping "macabre souvenirs", such as "a Vietnamese skull that sat on his desk." Other Americans "hacked the heads off Vietnamese to keep, trade, or exchange for prizes offered by commanders."[94]

Although the Utah Territory permitted a person sentenced to death to choose beheading as a means of execution, no person chose that option, and it was dropped when Utah became a state.[95]

In July 2025, Florida enacted legislation that further expands the state's already extensive capital punishment laws to allow "any execution method not explicitly deemed unconstitutional," which includes beheading. This makes the United States the only country outside of the Islamic world that currently allows executions via beheading.[96][97]

Notable people who have been beheaded

[edit]See also

[edit]- Atlanto-occipital dislocation, where the skull is dislodged from the spine; a generally, but not always, fatal injury.

- Beheading in Islam

- Beheading video

- Blood atonement

- Blood squirt, a result from a decapitation.

- Cephalophore, a martyred saint who is depicted carrying their severed head.

- Chhinnamasta, a Hindu goddess who supposedly decapitates herself and holds her head in her hand.

- Cleveland Torso Murderer, a serial killer who decapitated some of his victims.

- Dismemberment

- François-Jean de la Barre

- Headhunting

- List of methods of capital punishment

- Mike the Headless Chicken

- Head on a spike

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of HEADSMAN". Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "Blows Head Off with Dynamite?". The Rhinelander Daily News. 2 April 1937. p. 7. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Republican Decree – By Law No. [13] For 1994 Concerning the Criminal Procedures" (PDF). 12 October 1994. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 May 2024. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ "Sharia Criminal Procedure Code Law 2005, No. 6 of 2005" (PDF). 23 November 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2023. Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Tracqui, A.; Fonmartin, K.; Géraut, A.; Pennera, D.; Doray, S.; Ludes, B. (1 December 1998). "Suicidal hanging resulting in complete decapitation: a case report". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 112 (1): 55–57. doi:10.1007/s004140050199. ISSN 1437-1596. PMID 9932744. S2CID 7854416. Archived from the original on 20 August 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ Dinkel, Andreas; Baumert, Jens; Erazo, Natalia; Ladwig, Karl-Heinz (January 2011). "Jumping, lying, wandering: Analysis of suicidal behaviour patterns in 1,004 suicidal acts on the German railway net". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 45 (1): 121–125. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.005. PMID 20541771.

- ^ De Giorgio, Fabio; Polacco, Matteo; Pascali, Vincenzo L.; Oliva, Antonio (October 2006). "Death Due to Railway-Related Suicidal Decapitation". Medicine, Science and the Law. 46 (4): 347–348. doi:10.1258/rsmmsl.46.4.347. ISSN 0025-8024. PMID 17191639. S2CID 41916384. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Guillotine death was suicide". BBC News. 24 April 2003. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ^ Francis Larson. Severed: a history of heads lost and heads found Liveright, 2014.

- ^ Fabian, Ann (1 December 2014). "Losing our Heads (review of Larson's "Severed" Chronicle of Higher Education". Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ Dunmore, Charles; Fleischer, Rita (2008). Studies in Etymology (Second ed.). Focus. ISBN 978-1-58510-012-5.

- ^ a b "Decapitation". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, edited by Noah Porter, published by G & C. Merriam Co., 1913

- ^ a b c d Roberson, Cliff; Das, Dilip K. (2008). An Introduction to Comparative Legal Models of Criminal Justice. CRC Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-4200-6593-0. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Giovénal, Carine; Corbellari, Alain (2020). "42 | 2020 Le chief tranché". Babel (in French). 42 (42). doi:10.4000/babel.11036.

- ^ Smollett, T. (1758). A Complete History of England, from the Descent of Julius Caesar. Vol. 4. London. p. 488. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Cheetham, J.K. (2000). On the Trail of Mary Queen of Scots. Glasgow. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-946487-50-9. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Complete Peerage. Vol. XII part II. p. 393.

- ^ Hume, David (1792). The history of the reign of Henry the eighth. London. p. 151. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Turner, Matthew D. (2023). "The Most Gentle of Lethal Methods: The Question of Retained Consciousness Following Decapitation". Cureus. 15 (1) e33830. doi:10.7759/cureus.33830. PMC 9930870. PMID 36819446.

- ^ Gabriel Beaurieux, writing in 1905, quoted in Kershaw, Alister (1958). A History of the Guillotine. John Calder. ISBN 978-1-56619-153-1.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help), cited by "Losing One's Head: A Frustrating Search for the 'Truth' about Decapitation". The Chirurgeon's Apprentice. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014. - ^ Hillman, Harold (27 October 1983). "An Unnatural Way to Die". New Scientist: 276–278. Cited in Shanna Freeman (17 September 2008). "Top 10 Myths About the Brain". How Stuff Works. p. 5: Your Brain Stays Active After You Get Decapitated. Archived from the original on 6 April 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- ^ van Rijn, Clementina M. (27 January 2011). "Decapitation in Rats: Latency to Unconsciousness and the 'Wave of Death'". PLOS ONE. 6 (1) e16514. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616514R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016514. PMC 3029360. PMID 21304584.

- ^ Derr, Robert F. (29 August 1991). "Pain perception in decapitated rat brain". Life Sciences. 49 (19): 1399–1402. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(91)90391-n. PMID 1943446.

- ^ Holson, R. Robert (6 January 1992). "Euthanasia by decapitation: Evidence that this technique produces prompt, painless unconsciousness in laboratory rodents". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 14 (4): 253–257. Bibcode:1992NTxT...14..253H. doi:10.1016/0892-0362(92)90004-t. PMID 1522830.

- ^ Hawkins, Penny (23 August 2016). "A Good Death? Report of the Second Newcastle Meeting on Laboratory Animal Euthanasia". Animals. 6 (50): 50. doi:10.3390/ani6090050. PMC 5035945. PMID 27563926.

- ^ Kongara, Kavitha (January 2014). "Electroencephalographic evaluation of decapitation of the anesthetized rat". Laboratory Animals. 48 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1177/0023677213502016. PMID 24367032. S2CID 24006386. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Choi, Charles. "Fact or Fiction?: A Cockroach Can Live without Its Head". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Leahy, Stephen (7 June 2018). "Decapitated Snake Head Nearly Kills Man – Here's How". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 7 June 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ "AL man battles headless rattlesnake". WSFA 12 News. 7 June 2018. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ Sjøgren, Kristian (13 February 2014). "Why do headless chickens run?". ScienceNordic. Archived from the original on 7 August 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ^ Roach, Mary (2004). Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-393-32482-2.

- ^ Mignet, François, History of the French Revolution from 1789 to 1814, (1824).

- ^ Our Foreign Staff (4 August 2017). "Army of 'bewitched' children involved in Congo massacres as UN reports hundreds of deaths". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Libre. Be, La. "Meurtre de deux experts de l'ONU: la RDC présente une vidéo" [Murder of two UN experts: the DRC presents a video]. Lalibre.be (in French). Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ "UN Experts conclude crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Kasai, warn against risk of new wave of ethnic violence". Ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ "In English Aftonbladet reveals new information about the murders of Zaida Catalán and Michael Sharp". Aftonbladet. 7 October 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "How Uruguayan Peacekeepers Found the Two Dead UN Experts in Congo in 2017". 29 May 2019. Archived from the original on 11 October 2023. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Armenian Soldier Reburied". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Armenian Service. 11 April 2016. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ Beliakov, Dmitry; Franchetti, Mark (10 April 2016). "Former Russian states on brink of renewing war". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2016.

- ^ Kerkonian, Karnig (19 May 2016). "Illinois voters support Senator Kirk's call for pro-peace measures in Nagorno-Karabakh". The Hill. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "Azerbaijan: Armenian Prisoners of War Badly Mistreated". Human Rights Watch. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 23 February 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ^ "原來斬頭係唔會即刻死既(仲識講野)中國有好多斬頭案例!!". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ ""无头人"挑战传统医学 人类还有个"腹脑"?". Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ "福州晚報". Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "换人头". Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Masters, John (1956). Bugles and a tiger: a volume of autobiography. Viking Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-670-19450-6. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Barthorp, Michael; Anderson, Douglas N. (1996). The Frontier Ablaze: The North-west Frontier Rising, 1897–98. Windrow & Greene. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-85915-023-8. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- ^ Clay, John (1992). John Masters: a regimented life. University of Michigan: Michael Joseph. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7181-2945-3. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ Masters, John (2002). Bugles and a Tiger. Cassell Military. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-304-36156-4.

- ^ "善住坊とは". Kotobank.jp. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "UN – TRIBUNAL CONVICTS ENVER HADZIHASANOVIC AND AMIR KUBURA Press Release, March 2006". UN.org. United Nations. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Third Amended Indictment". Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "The Execution of King Charles I". National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander. p. 9.

- ^ Kenny, C. (1936). Outlines of Criminal Law (15th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 323.

- ^ The Chronological Table of the Statutes, 1235–2010. The Stationery Office. 2011. ISBN 978-0-11-840509-6. Part II. p. 1243, read with pages viii and x of Part I.

- ^ Gheeraert-Graffeuille, Claire (2011), "The Tragedy of Regicide in Interregnum and Restoration Histories of the English Civil Wars", Études Épistémè, 20 (20), doi:10.4000/episteme.430

- ^ Holmes, Clive (2010), "The Trial and Execution of Charles I", The Historical Journal, 53 (2): 289–316, doi:10.1017/S0018246X10000026, S2CID 159524099

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (2010). Druids: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 71–72.

- ^ Paul Jacobsthal Early Celtic Art

- ^ Wilhelm, James J. "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Romance of Arthur. Ed. Wilhelm, James J. New York: Garland Publishing, 1994. 399–465.

- ^ Pirlo, Paolo O. (1997). "St. Denis". My First Book of Saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate – Quality Catholic Publications. pp. 238–239. ISBN 971-91595-4-5.

- ^ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 467 n. 82.

- ^ a b Lieberman, Tehillah; Arbiv, Kfir; Nagar, Yossi (2 January 2020). "The Wrath of the Lion: Evidence of a Mass-Burial in Hasmonean Jerusalem". Tel Aviv. 47 (1): 97–98. doi:10.1080/03344355.2020.1707448. ISSN 0334-4355.

- ^ "Il y a 30 ans, avait lieu la dernière exécution" [Thirty years ago, the last execution took place], Le Nouvel Observateur (in French), 10 September 2007, archived from the original on 27 February 2008, retrieved 28 March 2014 (Google translation)

- ^ "Photographic image of newspaper article" (JPG). Grandcolombier.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ Otonkoski, Pirkko-Leena. "Henkirikoksista kuolemaan tuomittujen kohtaloita vuosina 1824–1825 Suomessa" [The fates of those sentenced to death for homicides in 1824–1825 in Finland]. Genos (in Finnish). 68: 55–69, 94–95. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ Execution of the Marquess of Ayamonte on the 11th. of December 1645 Described in "Varios relatos diversos de Cartas de Jesuitas" (1634–1648) Coll. Austral Buones Aires 1953 en Dr. J. Geers "Van het Barokke leven", Baarn 1957 Bl. 183–188.

- ^ "Iran: Violation of Human Rights 1987–1990". Amnesty International. 1 December 1990. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Text of the Iran Democracy Act Archived 5 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine, United States Senate

- ^ "Saddam halshögg 50 prostituerade" [Saddam beheaded 50 prostitutes] (in Swedish). 11 December 2000. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ Ignatieff, Michael (14 November 2004). "The Terrorist as Auteur". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- ^ "Beheading video tops web searches The decapitation of American Nick Berg and the Iraq war have replaced pornography and pop stars as the main internet searches". Al Jazeera. 18 May 2004. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Saudi executioner tells all". BBC News. 5 June 2003. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ Weinberg, Jon (Winter 2008). "Sword of Justice? Beheadings Rise in Saudi Arabia". Harvard International Review. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia: An upsurge in public executions". Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ "Justice by the Sword: Saudi Arabia's Embrace of the Death Penalty". International Business Times. 11 September 2012. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Death Sentences and Executions 2013" (PDF). Amnesty International. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "Syrian Rebels used a child to behead a prisoner". Human Rights Investigation. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ "Jihadist rebels behead 2 Syrian soldiers in northern Syria". AMN – Al-Masdar News. 13 August 2019. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 14 August 2019.

- ^ "Syrian opposition group that killed child 'was in US-vetted alliance'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Nearly 45 regime and Turkish soldiers and rebels killed in shelling and violent battles on Al-Nayrab frontline, east of Idlib". SOHR. 21 February 2020. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Grayson, George W. (February 2009). "La Familia: Another Deadly Mexican Syndicate". Foreign Policy Research Institute. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009.

- ^ Grayson, George W. (2012). The Executioner's Men: Los Zetas, Rogue Soldiers, Criminal Entrepreneurs, and the Shadow State They Created (1st ed.), p. 46, Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-4617-2

- ^ Paterson, Thomas; Clifford, J. Garry; Brigham, Robert; Donoghue, Michael; Hagan, Kenneth (2014). American Foreign Relations: Volume 2: Since 1895. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-285-43333-2. Archived from the original on 8 June 2024. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "US created monsters: Zetas and Kaibiles death squads". Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ badanov. "Borderland Beat: Los Zetas recruit Las Maras in Guatemala". Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ^ "Los Zetas fueron entrenados por la Escuela de las Américas" [The Zetas were trained by the School of the Americas]. cronica.com.mx (in Spanish). La Crónica de Hoy. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "U.S.-trained ex-soldiers form core of "Zetas" | SOA Watch: Close the School of the Americas". 18 April 2017. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017.

- ^ Washington, Harriet A. (2006). Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York. London. Toronto. Sydney. Austin.: Doubleday. p. 126, paragraph 3.

- ^ Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 163.

- ^ Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 162.

- ^ Turse, Nick (2013). Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 161.

- ^ Miller, Wilbur R. (2012). The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America: An Encyclopedia. Sage. p. 1856. ISBN 978-1-4129-8876-6. OCLC 768569594.

- ^ "10 of the worst state laws going into effect in July". 30 June 2025.

- ^ "House Bill 903 (2025) - the Florida Senate".

External links

[edit] Media related to Decapitation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Decapitation at Wikimedia Commons- Crime Library (archived)

- CapitalPunishmentUK.org

Decapitation

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Definition

Decapitation is the complete separation of the head from the body through severance of the neck, encompassing the transection of cervical vertebrae, major blood vessels such as the carotid arteries and jugular veins, spinal cord, trachea, esophagus, and associated musculature including the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[1][2] This process deprives the brain of oxygenated blood supply, causing rapid cerebral ischemia and neuronal death, rendering it invariably fatal in humans and other vertebrates within seconds to minutes due to the brain's high metabolic demands and limited tolerance for hypoxia.[4][8] Medically, decapitation is characterized as a traumatic or induced detachment of the head from the torso, distinct from partial neck injuries or cephalic fractures, and has been employed historically in executions, warfare, accidents, or experimental contexts, though modern forensic analysis emphasizes the precision required for total separation, often occurring between the second and fifth cervical vertebrae depending on neck flexion or extension.[9][10] In non-human applications, such as veterinary euthanasia, it serves as a physical method to halt brain function without chemical residue, but ethical and practical constraints limit its use.[4]Etymology

The term decapitation derives from the French décapitation, which entered English in the mid-17th century, with the earliest attested use in 1650 referring to the act of beheading.[11] [12] This French noun stems from the Late Latin verb decapitare, meaning "to cut off the head," formed by combining the prefix de- (indicating removal or "off" from) with caput (head).[2] [13] The Latin roots reflect a literal description of severing the head from the body, distinct from the Germanic beheading, which originated in Old English behēafdian and emphasizes the directional action of removing the head.[13] In modern usage, decapitation retains its primary sense of physical beheading but has extended metaphorically to denote abrupt removal from authority or position, as in political slang since the 19th century.[12]Physiological Aspects

Anatomy and Mechanism

Decapitation entails the complete separation of the head from the torso, typically transecting the neck between the second (C2) and fifth (C5) cervical vertebrae, where osseous protection is minimal and soft tissues predominate.[3] The neck's anatomy includes the cervical spinal cord, which transmits neural signals between brain and body; paired common carotid arteries supplying oxygenated blood to the brain; internal jugular veins draining deoxygenated blood; the trachea for airflow; the esophagus for swallowing; and critical nerves such as the vagus (for parasympathetic control) and phrenic (for diaphragmatic innervation).[14] The lethal mechanism centers on immediate cerebral ischemia from severed vascular structures, halting arterial inflow via the carotids and vertebrals while permitting rapid venous outflow, causing profound hypotension and oxygen-glucose deprivation to the brain.[1] This triggers anaerobic metabolism, lactic acidosis, glutamate excitotoxicity, and collapse of neuronal membrane potentials.[1] Concurrent spinal cord transection disrupts all supraspinal motor commands and sensory afferents, eliminating reflexive or volitional body responses below the cut.[3] Unconsciousness arises within 3–8 seconds as cerebral perfusion ceases, far below the brain's tolerance for even brief global hypoxia.[1] Electroencephalographic activity may linger 5–15 seconds in animal models, decaying to isoelectricity by 30 seconds, reflecting residual ATP-dependent firing before irreversible damage.[1] Death manifests as global brain failure from prolonged anoxia, with exsanguination accelerating hypovolemic shock, though cerebral events predominate.[15] Human extrapolations from rodent data and historical guillotine observations affirm rapid loss of integrated consciousness, with anecdotal reports of brief ocular or facial movements attributable to subcortical reflexes rather than awareness.[3]Consciousness, Pain, and Time to Death

Decapitation causes rapid cerebral ischemia by severing the carotid and vertebral arteries, leading to a precipitous drop in brain blood flow and oxygen delivery. The human brain, consuming approximately 20% of the body's oxygen despite comprising 2% of body weight, experiences hypoxia within seconds, resulting in loss of consciousness typically estimated at 2 to 7 seconds post-severance based on animal models extrapolating to human physiology.[16][3] Animal studies provide the primary empirical data, with electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings in decapitated rats showing low-voltage fast activity persisting for 8 to 29 seconds, though this reflects residual neural firing rather than sustained awareness. In these models, oxygen tension in the brain declines to levels inducing unconsciousness around 2.7 seconds after decapitation, with no evidence of organized cortical processing beyond initial hypoxic surges. Human inferences rely on similar vascular dynamics, though historical anecdotes suggest possible brief retained consciousness, such as the 1905 observation by Dr. Gabriel Beaurieux of executed criminal Henri Languille's severed head, where the eyes opened and focused upon hearing his name called, accompanied by intentional blinking lasting 25-30 seconds; and French Revolution accounts of heads attempting speech, eyes following crowds, blushing (e.g., Charlotte Corday's head reddening after being slapped), and reactions to medical tests like shouting or pricking. These reports are anecdotal, debated, and generally dismissed as spinal reflexes or muscular twitches devoid of conscious control rather than evidence of awareness; modern science attributes post-decapitation head reactions primarily to nervous reflexes rather than sustained consciousness, though brief awareness is not entirely ruled out, potentially allowing for fleeting perception of pain or disorientation upon severance.[7][17][3][18] Pain perception during decapitation is limited by the brevity of neural transmission to the brain. Nociceptors in the neck and spinal cord transmit signals via ascending pathways, but severance disrupts these before full processing, with the isolated head anatomically unable to register substantial trauma-related pain due to disconnected sensory integration. Any initial nociceptive volley would occur in the 100-200 millisecond range of the blade's transit, followed by immediate hypoperfusion curtailing further sensation; studies conclude that conscious pain experience, if any, endures no longer than the window to unconsciousness.[19][20] Death follows irreversibly within seconds to minutes, defined by cessation of brainstem function and global cerebral anoxia. While isolated neural activity may flicker briefly, clinical brain death—marked by absent pupillary response, corneal reflexes, and EEG flatline—occurs rapidly, with full somatic demise ensuing from cardiac arrest in the body and neuronal necrosis in the head. Peer-reviewed analyses affirm decapitation's physiological efficiency in terminating viability, countering unsubstantiated claims of prolonged survival.[3][21]Methods and Technologies

Manual Techniques

Manual decapitation employs handheld edged weapons, principally swords or axes, to separate the head from the body through a targeted strike at the neck.[5] This method, ancient in origin, relies on the executioner's physical prowess to deliver sufficient force for severance, typically positioning the victim kneeling with the neck extended over a block or held prone.[22][23] Swords, favored for nobility in regions like Germany and Sweden, feature broad, two-handed designs optimized for a sweeping slice rather than thrusting, enabling penetration through flesh, muscle, and bone when sharpened acutely.[24] Axes, conversely, predominate in English practice for commoners, utilizing a heavier head for chopping impact but risking glancing blows if misaimed.[25] The ideal strike targets the intervertebral space between the first and second cervical vertebrae to disrupt the spinal cord and major vasculature instantaneously.[5] Proficiency markedly influences outcomes; expert executioners could achieve decapitation in one blow, minimizing suffering, yet historical records document frequent failures due to dull blades, tremors, or inexperience, necessitating repeated hacks.[26] Notable instances include the 1540 execution of Thomas Cromwell, requiring five blows, and Margaret Pole's 1541 beheading, which demanded eleven strikes amid her resistance and the axeman's youth.[26][27] In modern application, Saudi Arabian authorities perform beheadings with a sword, often succeeding in a solitary, vertical stroke following ritual preparation, underscoring the technique's viability with rigorous training.[28] Improvised manual decapitations, such as those using knives in wartime contexts, prove less efficacious, frequently prolonging the process owing to the tool's limited cutting leverage.[3] Overall, manual methods' efficacy hinges on biomechanical precision, with variability in results reflecting the executioner's skill over inherent weapon superiority.[5]Mechanical Devices

Mechanical decapitation devices emerged in medieval Europe as alternatives to manual beheading, employing gravity-driven weighted blades to ensure more consistent severance of the head from the body. The Halifax Gibbet, used in Halifax, England, from the 16th century onward, featured a heavy iron blade suspended between two vertical wooden posts and released to fall into a lunette, targeting thieves under local customary law.[29] Its last documented execution occurred on April 30, 1650, against coin clippers.[30] In Scotland, the Maiden operated similarly from the mid-16th century, constructed primarily of oak with a steel-edged iron blade weighted by lead, designed for use on nobility to avoid the perceived dishonor of axe executions.[31] The earliest recorded use was in 1564, with notable executions including that of the Earl of Morton on June 2, 1581, for alleged involvement in Lord Darnley's murder; it remained in service until 1710.[29] The guillotine, refined in late 18th-century France, represented an advanced iteration with two upright posts connected by a horizontal crossbar, guiding an oblique-edged blade—typically weighing 70-90 kg—down greased grooves via a counterweighted pulley system for rapid descent at speeds up to 7 meters per second.[32] Proposed by physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin in 1789 to standardize humane capital punishment across social classes, its prototype was developed by surgeon Antoine Louis and executed by German engineer Tobias Schmidt, with official adoption on March 29, 1792, following tests on cadavers and live animals.[33] The first human execution took place on April 25, 1792, against highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier in Paris, initiating its widespread application during the French Revolution, where it severed approximately 17,000 heads in the city alone by 1794. These devices prioritized mechanical reliability over manual skill, reducing variability in execution time and force compared to swords or axes, though early models like the Gibbet occasionally malfunctioned due to blade dulling or misalignment.[29] The guillotine's design influenced variants across Europe, including in Germany, Belgium, and Switzerland, persisting into the 20th century; France's final use was on September 10, 1977, for the decapitation of Hamida Djandoubi.[33]Historical Development

Ancient and Classical Periods

Decapitation served as a method of execution and warfare tactic in ancient Mesopotamia, particularly among the Assyrians from the 9th to 7th centuries BCE, where reliefs depict soldiers presenting severed heads of enemies to kings as proof of victory, emphasizing psychological terror and trophy collection. Assyrian annals, such as those of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BCE), record stacking enemy heads into pyramids during campaigns to demoralize populations. In Hittite texts from the 14th–13th centuries BCE, beheading appears in legal codes as punishment for crimes like murder or treason, often involving public display of the head. In ancient Egypt, decapitation was rare for humans but documented in animal sacrifices and mythological contexts; human executions more commonly involved impalement or drowning, though tomb reliefs from the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BCE) show beheading of prisoners in Nubian campaigns. Greek practices in the Archaic and Classical periods (c. 800–323 BCE) included decapitation primarily in warfare, as described by Herodotus in accounts of Persian conflicts where heads were displayed on spears, but judicial executions favored hemlock poisoning for citizens, reserving beheading for slaves or foreigners. Mythologically, decapitation featured prominently, such as Perseus severing Medusa's head around the 8th century BCE in Hesiod's Theogony, symbolizing heroic triumph over chaos. Roman adoption of decapitation intensified during the Republic and Empire (509 BCE–476 CE), using the secari gladio (beheading by sword) for freeborn citizens convicted of capital crimes like treason, distinguishing it from crucifixion reserved for slaves and provincials. The Twelve Tables (c. 450 BCE) specified decapitation for certain thefts, and emperors like Caligula (r. 37–41 CE) ordered it for political rivals, with heads often exhibited on the Rostra in the Forum. In military contexts, Roman legions collected enemy heads during Gallic and Punic Wars, as noted by Polybius, to count kills and claim rewards, though mass decapitation declined with professionalization under Augustus (27 BCE–14 CE). Celtic tribes encountered by Romans practiced headhunting, venerating severed heads as talismans, evidenced by archaeological finds like the 1st-century BCE Corleck heads from Ireland.Medieval and Early Modern Eras

![Froissart Chronicles execution][float-right] In medieval Europe, decapitation served as a primary method of capital punishment, particularly reserved for nobility and high-status offenders due to its perceived rapidity and relative mercy compared to prolonged methods like hanging or burning.[34] This practice reflected social hierarchies in judicial proceedings, where commoners typically faced less "honorable" executions. Executions were often public spectacles intended to deter crime and reinforce authority, with the condemned frequently kneeling before the block.[35] The procedure relied on manual implements, primarily axes in England and swords on the continent, with executioners required to demonstrate proficiency through practice on animals before human application.[24] A single, clean stroke was ideal for instantaneous death, but botched attempts—requiring multiple blows—occurred due to dull blades, poor technique, or victim movement, prolonging suffering.[34] Swords, designed for two-handed swings and broader blades, allowed the executioner to stand behind the victim for better leverage, while axes demanded a forward stance and were more prone to inaccuracy.[25] Archaeological evidence, such as cut marks on skeletal remains from medieval Irish sites, confirms decapitation's prevalence and occasional post-mortem mutilation for traitors.[36] During the early modern period (c. 1500–1800), decapitation persisted as the standard for elite criminals across Europe, maintaining its association with privilege amid broader punitive innovations like drawing and quartering for treason.[37] In German states, specialized executioner's swords evolved for efficiency, emphasizing judicial ritual over combat utility.[24] Public beheadings continued to draw crowds, serving both punitive and communal functions, though criticisms of inconsistency foreshadowed mechanical alternatives. For instance, in England, the 1649 execution of King Charles I by axe underscored the method's symbolic weight in political upheavals, with the blow delivered on a scaffold before witnesses.[33] Regional variations endured, but the era saw growing emphasis on "humane" execution, setting the stage for 18th-century reforms.[38]Enlightenment to 20th Century

During the Enlightenment, penal reformers advocated for more humane execution methods, emphasizing swift and painless death over prolonged suffering. Influenced by Cesare Beccaria's 1764 treatise On Crimes and Punishments, which criticized torturous punishments, European thinkers pushed for standardized decapitation to ensure equality and efficiency in capital punishment.[33] In France, prior to the Revolution, executions varied by class—nobles often received sword beheading, while commoners faced axe or botched manual methods—leading to inconsistent and sometimes agonizing deaths.[39] The guillotine emerged as a mechanical solution in late 18th-century France. On October 10, 1789, physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed to the National Assembly a device for decapitation that would be quick, painless, and applicable to all classes, aiming to replace arbitrary methods.[33] The apparatus, designed by surgeon Antoine Louis and constructed by German engineer Tobias Schmidt, featured an angled blade dropping between upright posts onto a restrained neck.[39] It underwent testing in early 1792, with the first human execution occurring on April 25, 1792, when highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier was decapitated in Paris.[33] The device was decreed the sole method of capital punishment in France on October 16, 1792, symbolizing revolutionary equality.[40] The guillotine's prominence escalated during the French Revolution, particularly the Reign of Terror (1793–1794), where an estimated 17,000 individuals were executed by it, including King Louis XVI on January 21, 1793.[41] Executions, often public spectacles in Place de la Révolution (now Place de la Concorde), numbered over 1,000 in Paris alone by 1795, with machines deployed across provinces to meet demand.[33] Beyond the Revolution, France retained the guillotine through the 19th and 20th centuries, conducting thousands more executions; public beheadings ended after Eugen Weidmann's in 1939, with the last private one in 1977.[42] Other European nations adopted similar falling-blade devices in the 19th century, inspired by France's model. Germany employed the Fallbeil (guillotine variant) widely, executing approximately 16,500 people between 1933 and 1945 under the Nazi regime alone.[43] Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Greece, and parts of Italy integrated guillotines or equivalents for capital punishment, prioritizing mechanical precision over manual beheading to reduce errors and perceived cruelty.[33] In Sweden, decapitation became mandatory in 1866, shifting to guillotine use by the late 19th century.[33] These adoptions reflected broader Enlightenment-influenced reforms favoring deterministic, efficient state violence over feudal variability, though manual sword or axe beheadings persisted in some regions for ceremonial or practical reasons until the early 20th century.[39]Regional and Cultural Practices

Europe

![Execution of King Charles I by beheading][float-right]In medieval Europe, decapitation served as a form of capital punishment primarily reserved for nobility and those convicted of high treason, regarded as more honorable and less painful than methods like hanging or drawing and quartering applied to commoners.[37] Executioners typically used a sword or axe, with the sword preferred in continental Europe for its precision, aiming for a single swift blow to sever the neck.[34] In England, beheading followed hanging for traitors, as seen in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot conspirators who were hanged before decapitation.[22] Archaeological evidence from sites like late Roman Britain, though predating the medieval focus, indicates decapitation's continuity as a punitive measure, with prone burials and cut marks suggesting judicial enforcement.[44] During the early modern period, practices persisted with regional variations; in Germany and Prussia, executioner's swords—broad, two-handed blades—were employed for beheadings until the 19th century, symbolizing the gravity of offenses like treason or murder.[24] Noblewomen such as Benita von Falkenhayn faced axe beheading in Prussia as late as 1935 for financial crimes, marking one of the final manual decapitations in the region.[45] France transitioned from manual beheading to the guillotine in 1792, following physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin's proposal for a mechanized device to ensure egalitarian and humane execution regardless of class.[46] The guillotine's oblique blade dropped via a weighted mechanism, severing the head rapidly, and was first used on Nicolas Jacques Pelletier on April 25, 1792.[47] The guillotine became emblematic during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror (1793–1794), executing approximately 16,594 individuals, including King Louis XVI on January 21, 1793, to deter counter-revolutionary activity through public spectacle.[46] Its use extended into the 20th century, with public executions ending after Eugen Weidmann's beheading on June 17, 1939, in Versailles, after which privacy concerns prompted indoor proceedings.[48] France conducted the last guillotine execution in Western Europe on Hamida Djandoubi, convicted of murder, on September 10, 1977, in Marseille, prior to capital punishment's abolition in 1981.[29] Across Europe, decapitation declined with the shift to shooting or electrocution, reflecting evolving views on execution's efficacy and public impact, though manual methods lingered in isolated cases until mid-century.[38]