Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Entomology

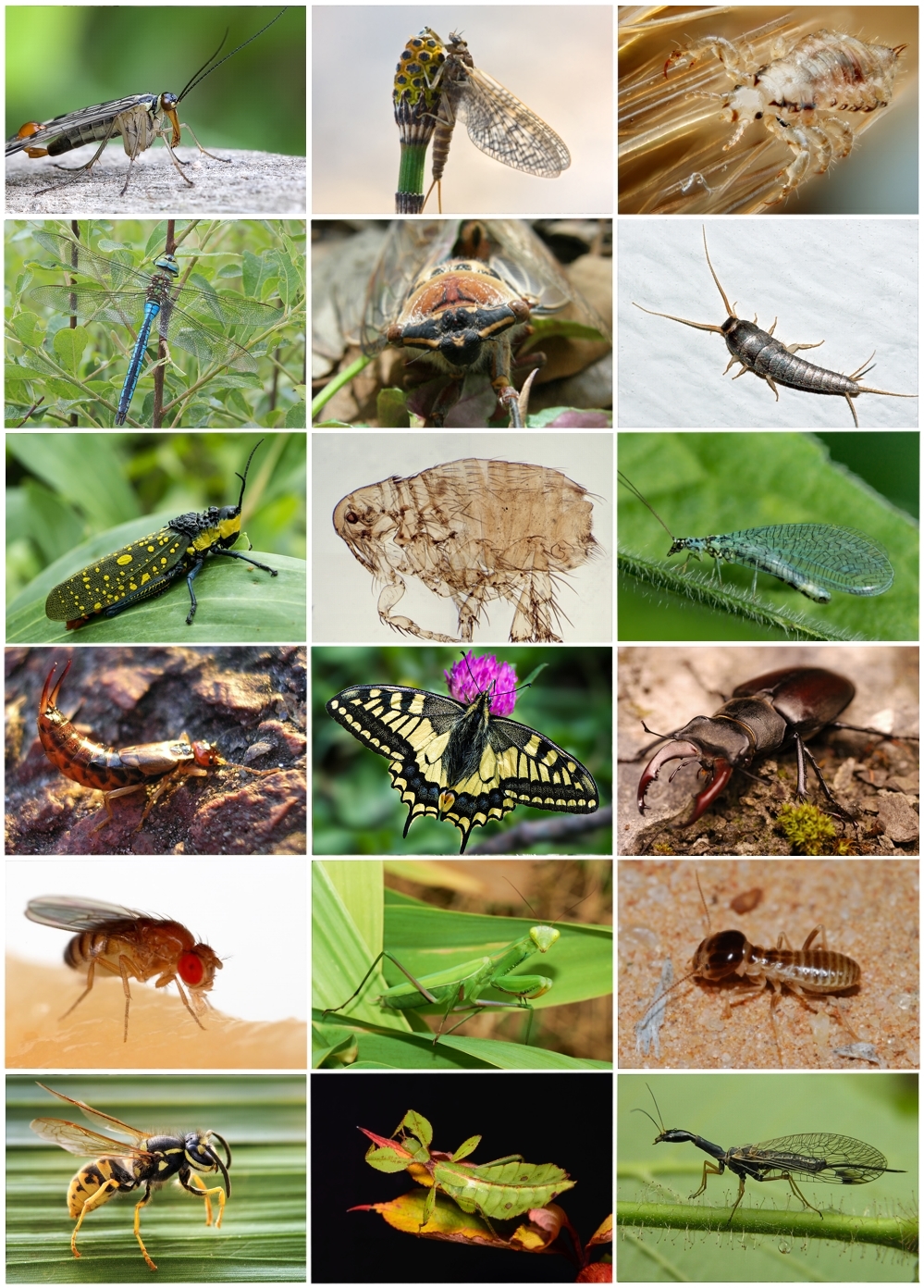

View on Wikipedia Diversity of insects from different orders

|

Entomology (from Ancient Greek ἔντομον (éntomon), meaning "insect", and -logy from λόγος (lógos), meaning "study") [1] is the branch of zoology that focuses on insects. Those who study entomology are known as entomologists. In the past, the term insect was less specific, and historically the definition of entomology would also include the study of animals in other arthropod groups, such as arachnids, myriapods, and crustaceans. The field is also referred to as insectology in American English, while in British English insectology implies the study of the relationships between insects and humans.[2]

Over 1.3 million insect species have been described by entomology.[3]

History

[edit]

Entomology is rooted in nearly all human cultures from prehistoric times, primarily in the context of agriculture (especially biological control and beekeeping).[4] The natural Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) wrote a book on the kinds of insects,[5] while the scientist of Kufa, Ibn al-A'rābī (760–845 CE) wrote a book on flies, Kitāb al-Dabāb (كتاب الذباب). However scientific study in the modern sense began only relatively recently, in the 16th century.[6] Ulisse Aldrovandi's De Animalibus Insectis (Concerning Insect Animals) was published in 1602. Microscopist Jan Swammerdam published History of Insects, correctly describing the reproductive organs of insects and metamorphosis.[7] In 1705, Maria Sibylla Merian published the book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium about the tropical insects of Dutch Surinam.[8]

Early entomological works associated with the naming and classification of species followed the practice of maintaining cabinets of curiosity, predominantly in Europe. This collecting fashion led to the formation of natural history societies, exhibitions of private collections, and journals for recording communications and the documentation of new species. Many of the collectors tended to be from the aristocracy, and there developed a trade involving collectors around the world and traders. This has been called the "era of heroic entomology". William Kirby is widely considered as the father of entomology in England. In collaboration with William Spence, he published a definitive entomological encyclopedia, Introduction to Entomology, regarded as the subject's foundational text. He also helped found the Royal Entomological Society in London in 1833, one of the earliest such societies in the world; earlier antecedents, such as the Aurelian society date back to the 1740s. In the late 19th century, the growth of agriculture, and colonial trade spawned the "era of economic entomology" which created the professional entomologist associated with the rise of the university and training in the field of biology.[9][10]

Entomology developed rapidly in the 19th and 20th centuries and was studied by large numbers of people, including such notable figures as Charles Darwin, Jean-Henri Fabre, Vladimir Nabokov, Karl von Frisch (winner of the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine),[11] and twice Pulitzer Prize winner E. O. Wilson.

There has also been a history of people becoming entomologists through museum curation and research assistance,[12] such as Sophie Lutterlough at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Insect identification is an increasingly common hobby, with butterflies[13] and (to a lesser extent) dragonflies being the most popular.[14]

Most insects can easily be allocated to order, such as Hymenoptera (bees, wasps, and ants) or Coleoptera (beetles). However, identifying to genus or species is usually only possible through the use of identification keys and monographs. Because the class Insecta contains a very large number of species (over 330,000 species of beetles alone) and the characteristics distinguishing them are unfamiliar, and often subtle (or invisible without a microscope), this is often very difficult even for a specialist. This has led to the development of automated species identification systems targeted on insects, for example, Daisy, ABIS, SPIDA and Draw-wing.

Applications

[edit]Pest control

[edit]In 1994, the Entomological Society of America launched a new professional certification program for the pest control industry called the Associate Certified Entomologist (ACE). To qualify as a "true entomologist" an individual would normally require an advanced degree, with most entomologists pursuing a PhD. While not true entomologists in the traditional sense, individuals who attain the ACE certification may be referred to as ACEs or Associate Certified Entomologists.[15]

As such, other credential programs managed by the Entomological Society of America have varying credential requirements. These different programs are known as Public Health Entomology (PHE), Certified IPM Technicians (CITs), and Board Certified Entomologists (BCEs) (ESA Certification Corporation). To be qualified in public health entomology (PHE), one must pass an exam on the types of arthropods that can spread diseases and lead to medical complications (ESA Certification Corporation). These individuals also have to "agree to ascribe to a code of ethical behavior" (ESA Certification Corporation). Individuals who are planning to become Certified IPM Technicians (CITs), need to obtain at around 1–4 years of experience in pest management and successfully pass an exam, that is based on the information, that they are acquainted with (ESA Certification Corporation). Like in Public Health Entomology (PHE), those who want to become Certified IPM Technicians (CITs) also have to "agree to ascribe to a code of ethical behavior" (ESA Certification Corporation). These individuals must also be approved to use pesticides (ESA Certification Corporation). For those who plan on becoming Board Certified Entomologists (BCEs), individuals have to pass two exams and "agree to ascribe to a code of ethical behavior" (ESA Certification Corporation). As with this, they also have to fulfill a certain amount of educational requirements every 12 months (ESA Certification Corporation).[16]

Forensics

[edit]Forensic entomology is a branch of forensic science that studies insects found on corpses or elsewhere around crime scenes. This includes studying the types of insects commonly found on cadavers, their life cycles, their presence in different environments, and how insect assemblages change with decomposition.[17]

Medicine

[edit]Medical entomology is focused upon insects and arthropods that impact human health. Veterinary entomology is included in this category, because many animal diseases can "jump species" and become a human health threat, for example, bovine encephalitis. Medical entomology also includes scientific research on the behavior, ecology, and epidemiology of arthropod disease vectors, and involves a tremendous outreach to the public, including local and state officials and other stake holders in the interest of public safety.

Subdisciplines

[edit]

Many entomologists specialize in a single order or even a family of insects, and a number of these subspecialties are given their own generic names, typically (but not always) derived from the scientific name of the group:

- Coleopterology – beetles

- Dipterology – flies

- Odonatology – dragonflies and damselflies

- Hemipterology – true bugs

- Isopterology – termites

- Lepidopterology – moths and butterflies

- Melittology (or Apiology) – bees

- Myrmecology – ants

- Orthopterology – grasshoppers, crickets, etc.

- Trichopterology – caddisflies

- Vespology – social wasps

Organizations

[edit]Like other scientific specialties, entomologists have a number of local, national, and international organizations. There are also many organizations specializing in specific subareas.

- Amateur Entomologists' Society

- British Entomological and Natural History Society

- Entomological Society of America

- Entomological Society of Canada

- Entomological Society of Japan

- Entomologischer Verein Krefeld

- Royal Entomological Society

- Australian Entomological Society[18]

- Entomological Society of New Zealand[19]

Research collection

[edit]Here is a list of selected very large insect collections, housed in museums, universities, or research institutes.

Asia

[edit]Africa

[edit]- Natal Museum, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa[20]

Australasia

[edit]

- Lincoln University Entomology Research Collection, Lincoln, New Zealand

Europe

[edit]- Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Zoologische Staatssammlung München

United States

[edit]- Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

- Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C.

Canada

[edit]- Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario

- Universtiy of Guelph Insect Collection, Guelph, Ontario

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ "Insectology". www.collinsdictionary.com. Collins. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Chapman, A. D. (2009). Numbers of living species in Australia and the World (2 ed.). Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 60pp. ISBN 978-0-642-56850-2. Archived from the original on 2009-05-19. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Smith, Edward H.; Kennedy, George G (2009). "Chapter 119 - History of Entomology". In Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition). Academic Press. pp. 449–458. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374144-8.00128-4. ISBN 978-0-12-374144-8.

- ^ Naturalis Historia

- ^ Antonio Saltini, Storia delle scienze agrarie, 4 vols, Bologna 1984–89, ISBN 88-206-2412-5, ISBN 88-206-2413-3, ISBN 88-206-2414-1, ISBN 88-206-2415-X

- ^ "Entomology". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 21 March 2024.

- ^ Kristensen, Niels P. (1999). "Historical Introduction". In Kristensen, Niels P. (ed.). Lepidoptera, moths and butterflies: Evolution, Systematics and Biogeography. Volume 4, Part 35 of Handbuch der Zoologie:Eine Naturgeschichte der Stämme des Tierreiches. Arthropoda: Insecta. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-11-015704-8.

- ^ Elias, Scott A. (2014). "A Brief History of the Changing Occupations and Demographics of Coleopterists from the 18th Through the 20th Century". Journal of the History of Biology. 47 (2): 213–242. doi:10.1007/s10739-013-9365-9. JSTOR 43863376. PMID 23928824. S2CID 24812002.

- ^ Clark, John F.M. (2009). Bugs and the Victorians. Yale University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0300150919.

- ^ "Karl von Frisch – Nobel Lecture: Decoding the Language of the Bee".

- ^ Starrs, Siobhan (10 August 2010). "A Scientist and a Tinkerer – A Story in a Frame". National Museum of Natural History Unearthed. National Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Prudic, KL; McFarland, KP; Oliver, JC; Hutchinson, RA; Long, EC; Kerr, JT; Larrivée, M (18 May 2017). "eButterfly: Leveraging Massive Online Citizen Science for Butterfly Consevation". Insects. 8 (2): 53. doi:10.3390/insects8020053. PMC 5492067. PMID 28524117.

- ^ Bried, Jason; Ries, Leslie; Smith, Brenda; Patten, Michael; Abbott, John; Ball-Damerow, Joan; Cannings, Robert; Cordero-Rivera, Adolfo; Córdoba-Aguilar, Alex; De Marco, Paulo; Dijkstra, Klaas-Douwe; Dolný, Aleš; van Grunsven, Roy; Halstead, David; Harabiš, Filip; Hassall, Christopher; Jeanmougin, Martin; Jones, Colin; Juen, Leandro; Kalkman, Vincent; Kietzka, Gabriella; Mazzacano, Celeste Searles; Orr, Albert; Perron, Mary Ann; Rocha-Ortega, Maya; Sahlén, Göran; Samways, Michael; Siepielski, Adam; Simaika, John; Suhling, Frank; Underhill, Les; White, Erin (16 October 2020). "Towards Global Volunteer Monitoring of Odonate Abundance". BioScience. 70 (10): 914–923. doi:10.1093/biosci/biaa092.

- ^ "ACE Certification". ACE Certification. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

- ^ "Roster | Certification - Entomological Society of America". entocert.org. Retrieved 2023-10-08.

- ^ "Forensic Entomology". Explore Forensics. Archived from the original on February 23, 2009. Retrieved 2022-04-10.

- ^ Australian Entomological Society

- ^ Entomological Society of New Zealand

- ^ "KwaZulu-Natal Museum".

Further reading

[edit]"I suppose you are an entomologist?"

"Not quite so ambitious as that, sir. I should like to put my eyes on the individual entitled to that name. No man can be truly called an entomologist, sir; the subject is too vast for any single human intelligence to grasp."

- Capinera, JL (editor). 2008. Encyclopedia of Entomology, 2nd Edition. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-6242-7

- Chiang, H.C. and G. C. Jahn 1996. Entomology in the Cambodia-IRRI-Australia Project. (in Chinese) Chinese Entomol. Soc. Newsltr. (Taiwan) 3: 9–11.

- Davidson, E. 2006. Big Fleas Have Little Fleas: How Discoveries of Invertebrate Diseases Are Advancing Modern Science University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 208 pages, ISBN 0-8165-2544-7.

- Gillot, Cedric. Entomology. Second Edition, Plenum Press, New York, NY / London 1995, ISBN 0-306-44967-6.

- Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82149-5.

- Triplehorn, Charles A. and Norman F. Johnson (2005-05-19). Borror and DeLong's Introduction to the Study of Insects, 7th edition, Thomas Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-03-096835-6. — a classic textbook in North America.

- Wale, Matthew. Making Entomologists: How Periodicals Shaped Scientific Communities in Nineteenth-Century Britain (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2022) online book review