Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

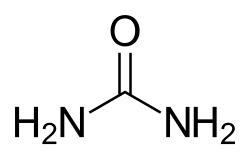

Urine

View on Wikipedia

Urine, excreted by the kidneys, is a liquid containing excess water and water-soluble nitrogen-rich by-products of metabolism including urea, uric acid, and creatinine, which must be cleared from the bloodstream. Urinalysis detects these nitrogenous wastes in mammals.

In placental mammals, urine travels from the kidneys via the ureters to the bladder and exits the urethra through the penis or vulva during urination. Other vertebrates excrete urine through the cloaca.[1]

Urine plays an important role in the earth's nitrogen cycle. In balanced ecosystems, urine fertilizes the soil and thus helps plants to grow. Therefore, urine can be used as a fertilizer. Some animals mark their territories with urine.[2][3] Historically, aged or fermented urine (known as lant) was also used in gunpowder production, household cleaning, leather tanning, and textile dyeing.

Human urine and feces, called human waste or human excreta, are managed via sanitation systems. Livestock urine and feces also require proper management if the livestock population density is high.

Physiology

[edit]

Most animals have excretory systems for elimination of soluble toxic wastes. In humans, soluble wastes are excreted primarily by the urinary system and, to a lesser extent in terms of urea, removed by perspiration.[4] In placental mammals, the urinary system consists of the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra. The system produces urine by a process of filtration, reabsorption, and tubular secretion. The kidneys extract the soluble wastes from the bloodstream, as well as excess water, sugars, and a variety of other compounds. The resulting urine contains high concentrations of urea and other substances, including toxins. Urine flows from the kidneys through the ureter, bladder, and finally the urethra before passing through the urinary meatus.

Duration

[edit]Research looking at the duration of urination in a range of mammal species found that nine larger species urinated for 21 ± 13 seconds irrespective of body size.[5] Smaller species, including rodents and bats, cannot produce steady streams of urine and instead urinate with a series of drops.[5]

Characteristics

[edit]Quantity

[edit]Average urine production in adult humans is around 1.4 L (0.31 imp gal; 0.37 US gal) of urine per person per day with a normal range of 0.6 to 2.6 L (0.13 to 0.57 imp gal; 0.16 to 0.69 US gal) per person per day, produced in around 6 to 8 urinations per day depending on state of hydration, activity level, environmental factors, weight, and the individual's health.[7] Producing too much or too little urine needs medical attention. Polyuria is a condition of excessive production of urine (> 2.5 L/day), oliguria when < 400 mL are produced, and anuria being < 100 mL per day.

Constituents

[edit]

About 91–96% of urine consists of water.[7] The remainder can be broadly characterized into inorganic salts, urea, organic compounds, and organic ammonium salts.[7][8] Urine also contains proteins, hormones, and a wide range of metabolites,[9] varying by what is introduced into the body.[citation needed]

The total solids in urine are on average 59 g (2.1 oz) per day per person.[9] Urea is the largest constituent of the solids, constituting more than 50% of the total. The daily volume and composition of urine varies per person based on the amount of physical exertion, environmental conditions, as well as water, salt, and protein intakes.[7] In healthy persons, urine contains very little protein and an excess is suggestive of illness, as with sugar.[9] Organic matter, in healthy persons, also is reported to at most 1.7 times more matter than minerals.[8] However, any more than that is suggestive of illness.[8]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| pH | 6.2 |

| Total nitrogen | 8,830 mg/L |

| Ammonium/ammonia-N | 460 mg/L |

| Nitrate and nitrite | 0.06 mg/L |

| Chemical oxygen demand | 6,000 mg/L |

| Total phosphorus | 800–2,000 mg/L |

| Potassium | 2,740 mg/L |

| Sulphate | 1,500 mg/L |

| Sodium | 3,450 mg/L |

| Magnesium | 120 mg/L |

| Chloride | 4,970 mg/L |

| Calcium | 230 mg/L |

However, it is important to note that lesser amounts and concentrations of other compounds and ions are often present in urination of humans.[9]

Color

[edit]

Urine varies in appearance, depending principally upon a body's level of hydration, interactions with drugs, compounds and pigments or dyes found in food, or diseases.[9] Normally, urine is a transparent solution ranging from colorless to amber, but is usually a pale yellow.[9] Usually urination color comes primarily from the presence of urobilin.[12] Urobilin is a final waste product resulting from the breakdown of heme from hemoglobin during the destruction of aging blood cells.[13][14]

Colorless urine indicates over-hydration. Colorless urine in drug tests can suggest an attempt to avoid detection of illicit drugs in the bloodstream through over-hydration.

- Bloody urine is termed hematuria, a symptom of a wide variety of medical conditions.

- Reddish or brown urine may be caused by porphyria (not to be confused with the harmless,[9] temporary pink or reddish tint caused by beeturia).

- Pinkish urine can result from the consumption of beets (beeturia)[9]

- Dark yellow urine is often indicative of dehydration.

- Orange urine due to certain medications such as rifampin and phenazopyridine

- Dark orange to brown urine can be a symptom of jaundice, rhabdomyolysis, or Gilbert's syndrome.

- Greenish urine can result from the consumption of asparagus or foods,[citation needed] beverages with green pigments, or from a urinary tract infection.[9]

- Blue urine can be caused by the ingestion of methylene blue (e.g., in medications) or foods or beverages with blue dyes.

- Blue urine stains can be caused by blue diaper syndrome.

- Purple urine may be due to purple urine bag syndrome.

- Black or dark-colored urine is referred to as melanuria and may be caused by a melanoma or non-melanin acute intermittent porphyria.

-

Dark urine due to low fluid intake.

-

Dark red urine due to choluria.

-

Pinkish urine due to consumption of beetroots.

-

Green urine during long term infusion of the sedative propofol.

Odor

[edit]

Sometime after leaving the body, urine may acquire a strong "fish-like" odor because of contamination with bacteria that break down urea into ammonia.[citation needed] This odor is not present in fresh urine of healthy individuals; its presence may be a sign of a urinary tract infection.[citation needed]

The odor of normal human urine can reflect what has been consumed or specific diseases.[9] For example, an individual with diabetes mellitus may present a sweetened urine odor. This can be due to kidney diseases as well, such as kidney stones.[citation needed] Additionally, the presence of amino acids in urine (diagnosed as maple syrup urine disease) can cause it to smell of maple syrup.[16]

Eating asparagus can cause a strong odor reminiscent of the vegetable caused by the body's breakdown of asparagusic acid.[17] Likewise consumption of saffron, alcohol, coffee, tuna fish, and onion can result in telltale scents.[18] Particularly spicy foods can have a similar effect, as their compounds pass through the kidneys without being fully broken down before exiting the body.[19][20]

pH

[edit]The pH normally is within the range of 5.5 to 7 with an average of 6.2.[7] In persons with hyperuricosuria, acidic urine can contribute to the formation of stones of uric acid in the kidneys, ureters, or bladder.[21] Urine pH can be monitored by a physician or at home.[22]

A diet which is high in protein from meat and dairy, as well as alcohol consumption can reduce urine pH, whilst potassium and organic acids, such as from diets high in fruit and vegetables, can increase the pH and make it more alkaline.[7]

Cranberries, popularly thought to decrease the pH of urine, have actually been shown not to acidify urine.[23] Drugs that can decrease urine pH include ammonium chloride, chlorothiazide diuretics, and methenamine mandelate.[24][25]

Density

[edit]Human urine has a specific gravity of 1.003–1.035.[7]

Bacteria and pathogens

[edit]Urine is not sterile, not even in the bladder,[26][27] contrary to longstanding popular belief. This opened a new area of study: the urinary microbiome. In the urethra, epithelial cells lining the urethra are colonized by facultatively anaerobic Gram-negative rod and cocci bacteria.[28] One study conducted in Nigeria isolated a total of 77 distinct bacterial strains from 100 healthy children (ages 5–11) as well as 39 strains from 33 cow urine samples, a considerable amount being pathogens.[29] Pathogens identified and their percentages were:

| Humans aged 5–11 | Bacterial percentage in humans | Bacterial percentage in cows |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus | 10.4% | 5.1% |

| Staphylococcus | 2.6% | 2.6% |

| Citrobacter | 3.9% | 12.8% |

| Klebsiella | 7.8% | 12.8% |

| Escherichia coli | 36.4% | 23.1% |

| Proteus | 18.2% | 23.1% |

| Pseudomonas | 9.1% | 2.6% |

| Salmonella | 3.9% | 5.1% |

| Shigella | 7.8% | 12.8% |

The study also states:

Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) rates recorded in children urinal bacterial species were 37.5–100% (Gram-positive) and 12.5–100% (Gram-negative), while MAR among the cow urinal bacteria was 12.5–75.0% (Gram-positive) and 25.0–100% (Gram-negative).

Examination for medical purposes

[edit]

Many physicians in ancient history resorted to the inspection and examination of the urine of their patients. Hermogenes wrote about the color and other attributes of urine as indicators of certain diseases. Abdul Malik Ibn Habib of Andalusia (d. 862 AD) mentions numerous reports of urine examination throughout the Umayyad empire.[30] Diabetes mellitus got its name because the urine is plentiful and sweet.[31] The name uroscopy refers to any visual examination of the urine,[32] including microscopy, although it often refers to the aforementioned prescientific or Proto-scientific forms of urine examination. Clinical urine tests today duly note the color, turbidity, and odor of urine but also include urinalysis, which chemically analyzes the urine and quantifies its constituents. A culture of the urine is performed when a urinary tract infection is suspected, as bacteriuria without symptoms does not require treatment.[33] A microscopic examination of the urine may be helpful to identify organic or inorganic substrates and help in the diagnosis.

The color and volume of urine can be reliable indicators of hydration level. Clear and copious urine is generally a sign of adequate hydration. Dark urine is a sign of dehydration. The exception occurs when diuretics are consumed, in which case urine can be clear and copious and the person still be dehydrated.

Uses

[edit]

Source of medications

[edit]Urine contains proteins and other substances that are useful for medical therapy and are ingredients in many prescription drugs. Urine from postmenopausal women is rich in gonadotropins that can yield follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone for fertility therapy.[34] One such commercial product is Pergonal.[35]

Urine from pregnant women contains enough human chorionic gonadotropins for commercial extraction and purification to produce hCG medication. Pregnant mare urine is the source of estrogens, namely Premarin.[34] Urine also contains antibodies, which can be used in diagnostic antibody tests for a range of pathogens, including HIV-1.[36]

Urine can also be used to produce urokinase, which is used clinically as a thrombolytic agent.[citation needed]

Fertilizer

[edit]Applying urine as fertilizer has been called "closing the cycle of agricultural nutrient flows" or ecological sanitation or ecosan. Urine fertilizer is usually applied diluted with water because undiluted urine can chemically burn the leaves or roots of some plants, causing plant injury,[37] particularly if the soil moisture content is low. The dilution also helps to reduce odor development following application. When diluted with water (at a 1:5 ratio for container-grown annual crops with fresh growing medium each season or a 1:8 ratio for more general use), it can be applied directly to soil as a fertilizer.[38][39] The fertilization effect of urine has been found to be comparable to that of commercial nitrogen fertilizers.[40][41] Urine may contain pharmaceutical residues (environmental persistent pharmaceutical pollutants).[42] Concentrations of heavy metals such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, commonly found in sewage sludge, are much lower in urine.[43]

Typical design values for nutrients excreted with urine are: 4 kg nitrogen per person per year, 0.36 kg phosphorus per person per year and 1.0 kg potassium per person per year.[44]: 5 Based on the quantity of 1.5 L urine per day (or 550 L per year), the concentration values of macronutrients as follows: 7.3 g/L N; .67 g/L P; 1.8 g/L K.[44]: 5 [45]: 11 These are design values but the actual values vary with diet.[46][a] Urine's nutrient content, when expressed with the international fertilizer convention of N:P2O5:K2O, is approximately 7:1.5:2.2.[45][b] Since urine is rather diluted as a fertilizer compared to dry manufactured nitrogen fertilizers such as diammonium phosphate, the relative transport costs for urine are high as a lot of water needs to be transported.[45]

The general limitations to using urine as fertilizer depend mainly on the potential for buildup of excess nitrogen (due to the high ratio of that macronutrient),[38] and inorganic salts such as sodium chloride, which are also part of the wastes excreted by the renal system. Over-fertilization with urine or other nitrogen fertilizers can result in too much ammonia for plants to absorb, acidic conditions, or other phytotoxicity.[42] Important parameters to consider while fertilizing with urine include salinity tolerance of the plant, soil composition, addition of other fertilizing compounds, and quantity of rainfall or other irrigation.[48] It was reported in 1995 that urine nitrogen gaseous losses were relatively high and plant uptake lower than with labelled ammonium nitrate.[citation needed] In contrast, phosphorus was utilized at a higher rate than soluble phosphate.[49] Urine can also be used safely as a source of nitrogen in carbon-rich compost.[39]Cleaning

[edit]Given that urea in urine breaks down into ammonia, urine has been used for cleaning. In pre-industrial times, urine was used – in the form of lant or aged urine – as a cleaning fluid.[50] Urine was also used for whitening teeth in Ancient Rome.[51]

Gunpowder

[edit]Urine was used before the development of a chemical industry in the manufacture of gunpowder. Urine, a nitrogen source, was used to moisten straw or other organic material, which was kept moist and allowed to rot for several months to over a year. The resulting salts were washed from the heap with water, which was evaporated to allow collection of crude saltpeter crystals, that were usually refined before being used in making gunpowder.[52]

Survival uses

[edit]Urophagia is the consumption of urine. Urine was consumed in several ancient cultures for various health, healing, and cosmetic purposes. People have been known to drink urine in extreme cases of water scarcity.

The US Army Field Manual advises against drinking urine for survival. The manual explains that drinking urine tends to worsen rather than relieve dehydration due to the salts in it, and that urine should not be consumed in a survival situation, even when there is no other fluid available. In hot weather survival situations, where other sources of water are not available, soaking cloth (a shirt for example) in urine and putting it on the head can help cool the body.[53]

During World War I, Germans experimented with numerous poisonous gases as weapons. After the first German chlorine gas attacks, Allied troops were supplied with masks of cotton pads that had been soaked in urine. It was believed that the ammonia in the pad neutralized the chlorine. These pads were held over the face until the soldiers could escape from the poisonous fumes.[citation needed]

Urban legend states that urine works well against jellyfish stings.[54] This scenario has appeared many times in popular culture including in the Friends episode "The One With the Jellyfish", an early episode of Survivor, as well as the films The Real Cancun (2003), The Heartbreak Kid (2007) and The Paperboy (2012). However, at best it is ineffective, and in some cases this treatment may make the injury worse.[55][56][57]

Textiles

[edit]Urine has often been used as a mordant to help prepare textiles, especially wool, for dyeing. In the Scottish Highlands and Hebrides, the process of "waulking" (fulling) woven wool is preceded by soaking in urine, preferably infantile.[58]

Olfactory communication

[edit]Urine plays a role in olfactory communication, since it contains semiochemicals that act as pheromones.[59][60] The urine of predator species often contains kairomones[61] that serve as a repellent against their prey species.[62]

History

[edit]

The fermentation of urine by bacteria produces a solution of ammonia; hence fermented urine was used in Classical Antiquity to wash cloth and clothing, to remove hair from hides in preparation for tanning, to serve as a mordant in dying cloth, and to remove rust from iron.[63] Ancient Romans used fermented human urine (in the form of lant) to cleanse grease stains from clothing.[64] The emperor Nero instituted a tax (Latin: vectigal urinae) on the urine industry, continued by his successor, Vespasian. The Latin saying Pecunia non olet ('money does not smell') is attributed to Vespasian – said to have been his reply to a complaint from his son about the unpleasant nature of the tax. Vespasian's name is still attached to public urinals in France (vespasiennes), Italy (vespasiani), and Romania (vespasiene).

Alchemists spent much time trying to extract gold from urine, which led to discoveries such as white phosphorus by German alchemist Hennig Brand when distilling fermented urine in 1669. In 1773 the French chemist Hilaire Rouelle discovered the organic compound urea by boiling urine dry.

Language

[edit]The English word urine (/ˈjuːrɪn/, /ˈjɜːrɪn/) comes from the Latin urina (-ae, f.), which is cognate with ancient words in various Indo-European languages that concern water, liquid, diving, rain, and urination (for example Sanskrit varṣati meaning 'it rains' or vār meaning 'water' and Greek ourein meaning 'to urinate').[65] The onomatopoetic term piss predates the word urine, but is now considered vulgar.[66][67] Urinate was at first used mostly in medical contexts.[citation needed] Piss is also used in such colloquialisms as to piss off,[66] piss poor, and the slang expression pissing down to mean heavy rain. Euphemisms and expressions used between parents and children (such as wee, pee, number one and many others) have long existed.

Lant is a word for aged urine, originating from the Old English word hland referring to urine in general.

See also

[edit]- Drinking urine (urophagia)

- Ureotelic

- Urine therapy

- Urolagnia, an attraction to urine

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Marvalee H. Wake (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ MacDonald, David W. "Patterns of scent marking with urine and faeces amongst carnivore communities." Symposia of the Zoological Society of London. Vol. 45. No. 107. 1980.

- ^ Ewer, R. F. (2013-12-11). Ethology of Mammals. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4899-4656-0.

- ^ Arthur C. Guyton; John Edward Hall (2006). "25". Textbook of medical physiology (11 ed.). Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-8089-2317-6. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b Yang, P. J.; Pham, J.; Choo, J.; Hu, D. L. (26 June 2014). "Duration of urination does not change with body size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (33): 11932–11937. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11111932Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1402289111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4143032. PMID 24969420.

- ^ Watson, Lyall (2000-04-17). Jacobson's Organ: And the Remarkable Nature of Smell. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-24493-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rose, C.; Parker, A.; Jefferson, B.; Cartmell, E. (2015). "The Characterization of Feces and Urine: A Review of the Literature to Inform Advanced Treatment Technology". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (17): 1827–1879. Bibcode:2015CREST..45.1827R. doi:10.1080/10643389.2014.1000761. ISSN 1064-3389. PMC 4500995. PMID 26246784.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Archived 2017-10-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c "Composition Of The Urine". The British Medical Journal. 1 (579): 133. 1872. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 25231362.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "What Is in Your Urine? Take a Look at the Chemical Composition". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ von Münch, Elisabeth; Winker, Martina (May 2011). Technology review of urine diversion components (PDF). Deutsche Gesellschaft fürInternationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- ^ Udert, K.M.; Larsen, T.A.; Gujer, W. (2006-12-01). "Fate of major compounds in source-separated urine". Water Science and Technology. 54 (11–12): 413–420. Bibcode:2006WSTec..54..413U. doi:10.2166/wst.2006.921. ISSN 0273-1223. PMID 17302346. Archived from the original on 2022-03-08. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ John E. Hall (2016). "The liver as an organ". Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, 13th edition. Elsevier. p. 885. ISBN 978-1455770052.

- ^ Hall, Brantley; Levy, Sophia; Dufault-Thompson, Keith; Arp, Gabriela; Zhong, Aoshu; Ndjite, Glory Minabou; Weiss, Ashley; Braccia, Domenick; Jenkins, Conor; Grant, Maggie R.; Abeysinghe, Stephenie; Yang, Yiyan; Jermain, Madison D.; Wu, Chih Hao; Ma, Bing (January 2024). "BilR is a gut microbial enzyme that reduces bilirubin to urobilinogen". Nature Microbiology. 9 (1): 173–184. doi:10.1038/s41564-023-01549-x. ISSN 2058-5276. PMC 10769871. PMID 38172624.

- ^ Rayne, Elizabeth (2024-01-27). "Gotta go? We've finally found out what makes urine yellow". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

- ^ Miklósi, Ádám (2018-04-03). The Dog: A Natural History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-8999-0.

- ^ "Maple syrup urine disease". National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2022-06-10.

- ^ Lison M, Blondheim SH, Melmed RN (1980). "A polymorphism of the ability to smell urinary metabolites of asparagus". Br Med J. 281 (6256): 1676–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.281.6256.1676. PMC 1715705. PMID 7448566.

- ^ Hashemi, Shervin. "Fate of Nitrogen in Urine Separated Toilet Systems" (PDF). s-space.snu.ac.kr. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

Likewise consumption of saffron, alcohol, coffee, tuna fish, and onion can result in telltale scents.

- ^ Stefan Gates; Max La Riviere-Hedrick (15 March 2006). Gastronaut: adventures in food for the romantic, the foolhardy, and the brave. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 87–. ISBN 978-0-15-603097-7. Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Foods that Affect the Odor of Urine. livestrong.com. December 27, 2010.

- ^ Martín Hernández E, Aparicio López C, Alvarez Calatayud G, García Herrera MA (2001). "[Vesical uric acid lithiasis in a child with renal hypouricemia]". An. Esp. Pediatr. (in Spanish). 55 (3): 273–6. PMID 11676906. Archived from the original on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2008-12-25.

- ^ "Urine pH". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ^ Avorn J, Monane M, Gurwitz JH, Glynn RJ, Choodnovskiy I, Lipsitz LA (1994). "Reduction of bacteriuria and pyuria after ingestion of cranberry juice". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 271 (10): 751–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03510340041031. PMID 8093138.

We did not find evidence that urinary acidification was responsible for the observed effect, since the median pH of urine samples in the cranberry group (6.0) was actually higher than that in the experimental group (5.5). While cranberry juice has been advocated as a urinary acidifier to prevent urinary tract infections, not all studies have shown a reduction in urine pH with cranberry juice ingestion, even with consumption of 2000 mL per day.

- ^ Urine pH: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia . Nlm.nih.gov (2011-03-28). Retrieved on 2011-04-27.

- ^ Discovery Health "Urine PH – Medical Dictionary" Archived 2010-03-30 at the Wayback Machine. Healthguide.howstuffworks.com (2007-05-16). Retrieved on 2011-04-27.

- ^ Hilt, Evann E.; Kathleen McKinley; Meghan M. Pearce; Amy B. Rosenfeld; Michael J. Zilliox; Elizabeth R. Mueller; Linda Brubaker; Xiaowu Gai; Alan J. Wolfe; Paul C. Schreckenberger (26 December 2013). "Urine Is Not Sterile: Use of Enhanced Urine Culture Techniques To Detect Resident Bacterial Flora in the Adult Female Bladder". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 52 (3): 871–876. doi:10.1128/JCM.02876-13. PMC 3957746. PMID 24371246.

- ^ Engelhaupt, Erika (22 May 2014). "Urine is not sterile, and neither is the rest of you". Science News. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ Michael T. Madigan; Thomas D. Brock (2009). Brock biology of microorganisms. Pearson/Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-13-232460-1. Retrieved 10 September 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Ogunshe, Adenike Adedayo O.; Fawole, Abosede Oyeyemi; Ajayi, Victoria Abosede (2010-05-25). "Microbial evaluation and public health implications of urine as alternative therapy in clinical pediatric cases: health implication of urine therapy". The Pan African Medical Journal. 5: 12. doi:10.4314/pamj.v5i1.56188. ISSN 1937-8688. PMC 3032614. PMID 21293739.

- ^ Ibn Habib, Abdul Malik d.862CE/283AH "Kitaab Tib Al'Arab" (The Book of Arabian Medicine), Published by Dar Ibn Hazm, Beirut, Lebanon 2007(Arabic)

- ^ Ahmed, A. M. (2021-06-08). "History of diabetes mellitus - PubMed". Saudi Medical Journal. 23 (4): 373–378. PMID 11953758.

- ^ "Medical Definition of UROSCOPY". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Köves, B; Cai, T; Veeratterapillay, R; Pickard, R; Seisen, T; Lam, TB; Yuan, CY; Bruyere, F; Wagenlehner, F; Bartoletti, R; Geerlings, SE; Pilatz, A; Pradere, B; Hofmann, F; Bonkat, G; Wullt, B (25 July 2017). "Benefits and Harms of Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis by the European Association of Urology Urological Infection Guidelines Panel". European Urology. 72 (6): 865–868. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.014 PMID 28754533.

- ^ a b Carrell, D.T.; Peterson, C.M. (2010). Artificial insemination: intrauterine insemination. 31.3.1.2 Gonadotropins. New York, New York: Springer. p. 489. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1436-1. ISBN 9781441914361. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ^ Adelson, Andrea (1995-02-26). "Wall Street; A Fertility Drug Grows Scarce". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Urine Antibody Tests: New Insights into the Dynamics of HIV-1 Infection – Urnovitz et al. 45 (9): 1602 – Clinical Chemistry Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine. Clinchem.org. Retrieved on 2011-04-27.

- ^ Vines, H. M.; Wedding, R. T. (1960). "Some Effects of Ammonia on Plant Metabolism and a Possible Mechanism for Ammonia Toxicity". Plant Physiology. 35 (6): 820–825. doi:10.1104/pp.35.6.820. JSTOR 4259670. PMC 406045. PMID 16655428.

- ^ a b Morgan, Peter (2004). "10. The Usefulness of urine". An Ecological Approach to Sanitation in Africa: A Compilation of Experiences (CD release ed.). Aquamor, Harare, Zimbabwe. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Steinfeld, Carol (2004). Liquid Gold: The Lore and Logic of Using Urine to Grow Plants. Ecowaters Books. ISBN 978-0-9666783-1-4.[page needed]

- ^ Johansson M, Jönsson H, Höglund C, Richert Stintzing A, Rodhe L (2001). "Urine Separation – Closing the Nitrogen Cycle" (PDF). Stockholm Water Company.

- ^ Pradhan, Surendra K.; Nerg, Anne-Marja; Sjöblom, Annalena; Holopainen, Jarmo K.; Heinonen-Tanski, Helvi (2007). "Use of Human Urine Fertilizer in Cultivation of Cabbage (Brassica oleracea)––Impacts on Chemical, Microbial, and Flavor Quality". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (21): 8657–8663. Bibcode:2007JAFC...55.8657P. doi:10.1021/jf0717891. PMID 17894454.

- ^ a b Winker, Martina (2009). "Pharmaceutical Residues in Urine and Potential Risks related to Usage as Fertiliser in Agriculture". TUHH. doi:10.15480/882.481.

- ^ Håkan Jönsson (2001-10-01). "Urine Separation — Swedish Experiences". EcoEng Newsletter 1. Archived from the original on 2009-04-27. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ^ a b c Jönsson, H., Richert Stintzing, A., Vinnerås, B. and Salomon, E. (2004) Guidelines on the use of urine and faeces in crop production, EcoSanRes Publications Series, Report 2004-2, Sweden [This source seems to truncate the Jönsson & Vinnerås (2004) table by omitting the potassium row. The full version may be found at the original source at RG#285858813]

- ^ a b c von Münch, E., Winker, M. (2011). Technology review of urine diversion components - Overview on urine diversion components such as waterless urinals, urine diversion toilets, and urine storage and reuse systems. Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH

- ^ a b Rose, C; Parker, A; Jefferson, B; Cartmell, E (2015). "The Characterization of Feces and Urine: A Review of the Literature to Inform Advanced Treatment Technology". Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (17): 1827–1879. Bibcode:2015CREST..45.1827R. doi:10.1080/10643389.2014.1000761. PMC 4500995. PMID 26246784.

- ^ "Urine in my garden" (PDF). Rich Earth Institute.

Minimize odors by adding white vinegar or citric acid to the urine collection container before any urine is added. We use 1-2 cups of white vinegar or 1 tablespoon of citric acid per 5-gallon container. Adding vinegar also helps reduce nitrogen loss (via ammonia volatilization) during short-term storage.

- ^ Joensson, H., Richert Stintzing, A., Vinneras, B., Salomon, E. (2004). Guidelines on the Use of Urine and Faeces in Crop Production. Stockholm Environment Institute, Sweden

- ^ Kirchmann, H.; Pettersson, S. (1995). "Human urine - Chemical composition and fertilizer use efficiency". Fertilizer Research. 40 (2): 149–154. doi:10.1007/bf00750100.

- ^ Sueton, Vespasian 23 English Archived 2021-07-13 at the Wayback Machine, Latin Archived 2022-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. Cf. Dio Cassius, Roman History, Book 65, chapter 14,5 English Archived 2022-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, Greek/French (66, 14) Archived 2013-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geissberger, Marc (2010). Esthetic Dentistry in Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Son. p. 6. ISBN 9780813828251.

- ^ Joseph LeConte (1862). Instructions for the Manufacture of Saltpeter. Columbia, S.C.: South Carolina Military Department; printer: Charles P. Pelham. p. 14. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-10-19.

- ^ Water Procurement Archived 2009-06-12 at the Wayback Machine, US Army Field Manual

- ^ Castillo, M. (2017, June 20). Don't Pee On A Jellyfish Sting — It Won't Work | LittleThings.com. Littlethings. https://littlethings.com/entertainment/jellyfish-sting-news[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Old Wives' Tale? Urine as Jellyfish Sting Remedy". ABC News. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Fact or Fiction?: Urinating on a Jellyfish Sting is an Effective Treatment Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine. Scientific American. 4 January 2007. Retrieved on 2011-04-27.

- ^ Jellyfish Sting Treatment – How to Treat a Jellyfish Sting Archived 2008-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Firstaid.about.com. 22 August 2010. Retrieved on 2011-04-27.

- ^ Mentioned by an interviewee in Lomax the Songhunter, a 2004 documentary film.

- ^ Mucignat-Caretta, Carla (2014-02-14). Neurobiology of Chemical Communication. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-5341-5.

- ^ Wyatt, Tristram D. (2014-01-23). Pheromones and Animal Behavior: Chemical Signals and Signatures. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11290-1.

- ^ Osada, Kazumi; Miyazono, Sadaharu; Kashiwayanagi, Makoto (2015). "The scent of wolves: Pyrazine analogs induce avoidance and vigilance behaviors in prey". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 9: 363. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00363. PMC 4595651. PMID 26500485.

- ^ Swihart, Robert K., Joseph J. Pignatello, and Mary Jane I. Mattina. "Aversive responses of white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus, to predator urines." Archived 2021-10-18 at the Wayback Machine Journal of chemical ecology 17.4 (1991): 767-777.

- ^ See:

- Forbes, R.J., Studies in Ancient Technology, vol. 5, 2nd ed. (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1966), pp. 19 Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, 48 Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, and 65 Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine.

- Moeller, Walter O., The Wool Trade of Ancient Pompeii (Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1976), p. 20. Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Faber, G.A. (pseudonym of: Goldschmidt, Günther) (May 1938) "Dyeing and tanning in classical antiquity," Ciba Review, 9 : 277–312. Available at: Elizabethan Costume Archived 2021-01-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, William, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (London, England: John Murray, 1875), article: "Fullo" (i.e., fullers or launderers), pp. 551–553. Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Rousset, Henri (31 March 1917) "The laundries of the Ancients," Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine Scientific American Supplement, 83 (2152) : 197.

- Bond, Sarah E., Trade and Taboo: Disreputable Professions in the Roman Mediterranean (Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2016), p. 112. Archived 2021-07-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Binz, Arthur (1936) "Altes und Neues über die technische Verwendung des Harnes" (Ancient and modern [information] about the technological use of urine), Zeitschrift für Angewandte Chemie, 49 (23) : 355–360. [in German]

- Witty, Michael (December 2016) "Ancient Roman urine chemistry," Acta Archaeologica, 87 (1) : 179–191. Witty speculates that the Romans obtained ammonia in concentrated form by adding wood ash (impure potassium carbonate) to urine that had been fermented for several hours. Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) is thereby precipitated, and the yield of struvite can be increased by then treating the solution with bittern, a magnesium-rich solution that is a byproduct of making salt from sea water. Roasting struvite releases ammonia vapors.

- ^ "Hygiene in Ancient Rome". Archived from the original on 2010-10-18. Retrieved 2010-02-09.

- ^ "Definition of URINE". www.merriam-webster.com. 2024-05-07. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b Harper, D. (n.d.). Etymology of piss. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.etymonline.com/word/piss Archived 2022-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Definition of PISS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

External links

[edit]- Urinanalysis Archived 2007-01-17 at the Wayback Machine at the University of Utah Eccles Health Sciences Library

- Urine Chemistry at drugs.com

![Tigers spray small quantities of urine to mark their territories.[6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/86/Tiger_Tadoba_NP.jpg/1100px-Tiger_Tadoba_NP.jpg)