Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

List of Canadian flags

View on Wikipedia

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The Department of Canadian Heritage lays out protocol guidelines for the display of flags, including an order of precedence; these instructions are only conventional, however, and are generally intended to show respect for what are considered important symbols of the state or institutions.[1] The sovereign's personal standard is supreme in the order of precedence, followed by those for the monarch's representatives (depending on jurisdiction), the personal flags of other members of the Royal Family,[2] and then the national flag and provincial flags.

Many museums across Canada display historic flags in their exhibits. The Canadian Museum of History, in Hull, Quebec has many culturally important flags in their collections. Settlers, Rails & Trails Inc., in Argyle, Manitoba holds the second largest exhibit - known as the Canadian Flag Collection.

National and provincial flags

[edit]National

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1965–present | National Flag of Canada (The Maple Leaf, l'Unifolié) |

A vertical bicolour triband of red, white, red with a red maple leaf emblem charged in the Canadian pale |

Provincial

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1965–present | Flag of Ontario | A red field with the Royal Union Flag in the canton and the shield of the coat of arms of Ontario charged in the fly |

|

1948–present | Flag of Quebec (The Fleurdelisé) |

A blue field with an ordinary white cross and a white fleur-de-lis in each quadrant |

|

1858 (first use)

1929 (arms adopted) 2013 (flag adopted) –present |

Flag of Nova Scotia | A banner of arms of the coat of arms of Nova Scotia |

|

1965–present | Flag of New Brunswick | A banner of the coat of arms of New Brunswick |

|

Flag of Manitoba | A red field with the Royal Union Flag in the canton and the shield of the coat of arms of Manitoba charged in the fly | |

|

1960–present | Flag of British Columbia | A banner of the coat of arms of British Columbia |

|

1964–present | Flag of Prince Edward Island | A banner of the coat of arms of Prince Edward Island within a bordure compony of red and white |

|

1969–present | Flag of Saskatchewan | A field party per fess, green and yellow, with the shield of the coat of arms of Saskatchewan in the canton and western red lily emblem charged in the fly |

|

1968–present | Flag of Alberta | A blue field with the shield of the coat of arms of Alberta charged in the centre |

|

1980–present | Flag of Newfoundland and Labrador | A blue and white field party per pale (at nombril point) with a white border, white ordinary cross and white saltire, two triangular divisions in the fly lined in red, a golden arrow between two triangular divisions |

Territorial

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1969–present | Flag of the Northwest Territories | A vertical bicolour triband of blue, white, blue with the shield of the coat of arms of the Northwest Territories charged in the Canadian pale |

|

1968–present | Flag of Yukon | A vertical tricolour triband of green, white, blue with the shield of the coat of arms of Yukon above a wreath of fireweed charged in the pale, with pale ratio of 1 to 1.5 to 1 |

|

1999–present | Flag of Nunavut | A field party per pale, yellow and white, with a red inukshuk charged in the centre and a blue star in the upper fly |

Ceremonial

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

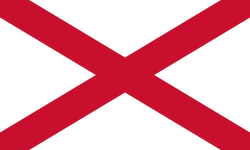

1965–present | Royal Union Flag | The Cross of St. Andrew counterchanged with the Cross of St. Patrick and over all the Cross of St. George. |

Royal

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2023–present | Royal Standard of Charles III, King of Canada | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada undifferentiated |

|

2011–present | Royal standard of the Prince of Wales | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada differentiated by a white three-pointed label and defaced with the Prince of Wales's feathers |

|

2013–present | Royal standard of Princess Anne | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada differentiated by a white three-pointed label; the first and third labels bearing a red cross, the centre label bearing a red heart; and defaced with a royal cypher of Princess Anne |

|

2014–present | Royal standard of Prince Edward, Duke of Edinburgh | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada differentiated by a three-pointed label; the centre label bearing a Tudor rose; and defaced with a royal cypher of Prince Edward |

|

2015–present | Other members of the royal family | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada with a border of ermine |

Viceregal and administrative

[edit]Governor general

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1981–1999 2002–present |

Flag of the governor general of Canada | A blue field with the crest of the Royal Arms of Canada charged in the centre |

Lieutenant governors and commissioners

[edit]Supreme Court of Canada

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2021 | Flag of the Supreme Court of Canada | Gules on a Canadian pale Argent a lozenge lozengy Gules and Argent charged with maple leaves alternately Or and Gules |

Military and civilian law enforcement organizations

[edit]Canadian Armed Forces

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1968–present | Flag of the Canadian Armed Forces | A white field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and the Canadian Armed Forces badge charged in the fly[3] |

|

1920–present | Flag of the Royal Military College of Canada | A field tierced per pale, red, white, and red with the badge of the Royal Military College of Canada charged in the centre |

|

Flag of the Royal Military College Saint-Jean | A field tierced per pale, blue, white, and blue with the badge of the Royal Military College Saint-Jean charged in the centre | |

|

2000–present | Banner of the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation | A field tierced per pale, blue, red, and azure, with the crest of the Royal Arms of Canada charged in the centre |

|

2009–present | Camp flag of the Cadet Instructors Cadre | The badge of the Cadet Instructors Cadre, with the traditional colours of the Navy, Army and the Air Force. The golden border represents the young people that CIC officers work for. |

|

−1965 | King's Colour, as used by the Royal Military College of Canada | King's Colour of the Royal Military College of Canada with the Union Flag. |

Canadian Army

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1939–1944 | Old flag of the Canadian Army | |

|

1968–1998 | ||

|

1998–2013 | ||

|

2013–2016 | ||

|

2016–present | Flag of the Canadian Army | A scarlet red field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and the Canadian Army badge charged in the fly |

|

–present | Flag of the Commander of the Canadian Army |

Royal Canadian Navy

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1968–present | Canadian Naval Ensign (2013-present), naval jack (1968-2013) | A white field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and charged in the fly with an anchor, eagle and naval crown in blue |

|

1979–present[4] | Canadian Forces Auxiliary Jack | A blue field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and charged in the fly with an anchor, eagle and naval crown in white |

|

c. 1964–present | Flag of the Canadian Navy Board | A field party per bend, blue and sanguine, with a fouled anchor in gold charged in the centre |

|

RCN (1911–1965) RCSCC (1905–1965) |

Used as the ensign of the Royal Canadian Navy and some Royal Canadian Sea Cadets corps. Used throughout the entire British Empire by the Royal Navy and by several former British colonies even after they became independent and established their own navies. | White Ensign, St George's Cross with the Union Flag in the canton. |

|

RCN (1957-1965) | The Blue Ensign, worn as a jack by the Royal Canadian Navy | Blue Ensign defaced with the Royal Arms of Canada. The maple leaves at the bottom of the shield are red. |

|

RCN (1921–1957) RCSCC (1929–1953) |

The Blue Ensign, worn as a jack by the Royal Canadian Navy and used by the RCSCC | Blue Ensign defaced with the Royal Arms of Canada. The maple leaves at the bottom of the shield are green. |

|

Naval Service of Canada / Royal Canadian Navy (1910–1911, as ensign; 1911-1921 as jack) RCSCC (1910–1922) |

The Blue Ensign, worn as ensign then jack by the Naval Service of Canada/Royal Canadian Navy | Blue Ensign defaced with the 1868 Great Seal of Canada. Worn as ensign from 1910 to 1913, then jack from 1913 to 1921, after Navy authorized to fly the British White Ensign.[5][6] |

Royal Canadian Air Force

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1921–1940 | Royal Canadian Air Force Ensign | A field of air force blue with the Union Flag in the canton and the Royal Air Force roundel charged in the fly |

|

1941–1968 | A field of air force blue with the Union Flag in the canton and the Royal Canadian Air Force roundel charged in the fly | |

|

1982–present | A field of air force blue with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and the Royal Canadian Air Force roundel charged in the fly |

Canadian Special Operations Forces Command

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Link to file | -present | Flag of the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command | A white field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and the CANSOFCOM badge charged in the fly |

Canada Border Services Agency

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2012–present | Flag of the Canada Border Services Agency | A Blue field with the National Flag of Canada in the canton and the Canada Border Services Agency badge charged in the fly |

Canadian Coast Guard

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1965–present | Jack of the Canadian Coast Guard | A banner of the arms of the Canadian Coast Guard: vertical diband of white and blue, a red maple leaf emblem charged in the hoist and a pair of dolphins in gold and facing opposite directions charged in the fly. Features current 11-point maple leaf designed by Jacques St-Cyr.[7] |

|

1962–1965 | Jack of the Canadian Coast Guard, original design | A white field with blue flank/side one third length of flag at the fly; field charged with a red maple leaf emblem and side at fly charged with a pair of heraldic dolphins in gold, one above the other and facing opposite directions.[nb 1] Features original 13-point maple leaf designed by Alan Beddoe.[9] |

|

1962–1965 | Ensign of the Canadian Coast Guard | Blue Ensign of Canadian Government Ships, defaced with Coat of Arms of Canada |

|

–present | Honorary Commissioner Flag | Governor General's flag in the canton. |

Police services

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1991–present | Ensign of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police | A red field with a blue canton bordered yellow with a representation of the Badge of the RCMP. |

| Link to file | 1998–present | Flag of the Ontario Provincial Police | Blue with the heraldic badge of the OPP. |

|

1983–present | Flag of the Sûreté du Québec | A green field, on a Canadian Pale Yellow charged with the badge of the Sûreté du Québec. |

|

–present | Flag of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary | A blue field with the badge of the RNC in the centre. |

Youth cadets organizations

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1953–1976[10] | Former flag of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets | A white flag with a Union Flag at the canton, with the badge of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets at the fly. This is the basis of the current flag of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets. |

|

1976–present[10] | Flag of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets | A white flag with a Canadian Flag at the canton, with the badge of the Royal Canadian Sea Cadets at the fly. |

|

2009–present[11] | Flag of the Navy League of Canada | A white flag with a Canadian Flag at the canton, with the current badge of the Navy League of Canada at the fly. |

|

1985–present[12] | Banner of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets | A Canadian flag in the same shape as a queen's colour used in the Canadian Armed Forces, with the maple leaf modified with the badge of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets. At the canton, the cypher of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, as former colonel-in-chief of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets. At the fly, a badge representing the Canadian Army (the crown of Saint Edward above crossed swords). |

|

1944–1973 | Flag of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets used by individual Army Cadet Corps used before 1973. | |

|

January 1973–present | Flag of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets used by individual Army Cadet Corps. | |

|

Camp Flag of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets. | On a white field, the badge of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets in the centre. | |

|

1995–present[13] | Flag of the Army Cadet League of Canada. | A banner of the shield of the arms of the Army Cadet League of Canada. According to the heraldic grant, the shield of the arms of the Army Cadet League of Canada is "Argent two swords in saltire Argent fimbriated Gules hilted and pommelled Or surmounted by a maple leaf Gules veined Or all within an orle of twelve maple leaves stems inward Gules."[14] The web site of the Governor General of Canada explains this description as follows: "The white shield, bearing a maple leaf and crossed broad swords, alludes to a central Canadian entity with direct connection to the military. The twelve smaller maple leaves show singleness of purpose but at the Branch level.[14] |

|

1991–present[15][12] | Banner of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets | Based on the design of Queen's Colour for the Royal Canadian Air Force, with the badge of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets replacing the maple leaf. At the canton, the cypher of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, as former air commodore in chief of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets. On the bottom fly, the first badge of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets, a golden maple leaf above an eagle. |

|

1971–present[15] | Ensign of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets | An Air Force blue flag, with a Canadian flag at the canton, with the historical badge of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets. |

|

Squadron Banner of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets | An Air Force blue flag, with the badge of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets and a scroll stating the squadron's name and number (this example, 643 St-Hubert Squadron. | |

|

Camp flag of the Junior Canadian Rangers | A 1/3 red and 2/3 green flag with the badge of the Junior Canadian Rangers on the fly. |

Civil

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1922–1923 | Canadian Civil Aviation Ensign, briefly used by the Air Board. | A field of light blue with the Union Flag in the canton and a shield with white albatross superimposed upon three maple leaves in the middle of the fly. |

Corporations

[edit]Crown corporations

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1992–present | Flag of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | A blue and red field with the logo of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation charged in the centre; logo was first introduced in 1992 |

|

1978–present | Flag of the Royal Canadian Mint | A red field with the logo of the Royal Canadian Mint charged in the centre; logo was first introduced in 1978 |

Hudson's Bay Company

[edit]Religious

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1955–present | Flag of the Anglican Church of Canada | |

|

–present | Flag of the Grand Orange Lodge of Canada |

Ethnic groups

[edit]Indigenous nations

[edit]Francophone peoples

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1884–present | Acadian flag | Tri-coloured flag, blue, white then red. A yellow star representing independence and unique culture from main land France. |

|

1975–present | Flag of the Franco-Ontarians | A field party per pale, green and white, with a white fleur-de-lys charged in the hoist and a green trillium emblem charged in the fly |

|

1976–present | Flag of the Fransaskois | A yellow field with a green Nordic cross centred towards the upper hoist and a red fleur-de-lis charged in the lower fly |

|

1980–present | Flag of the Franco-Manitobans | A white field with yellow over sanguine bars with a green plant emblem in four pieces charged in the hoist |

|

1981–present | Flag of the Franco-Columbians | A white field party per pale by a bar gemelles and dancetty, a fleur-de-lys and Pacific Dogwood emblem charged in the fly; Dogwood is the floral emblem of British Columbia, the blue stripes evoke the Pacific Ocean and the rising mountains beside, the yellow centre of the Dogwood flower represents the sun |

|

1982–present | Flag of the Franco-Albertans | A field party per bend sinister, blue and white, by a bend cotised white and blue with a white fleur-de-lys in the upper hoist and a red wild rose in the lower fly |

|

1985–present | Flag of the Franco-Yukonnais | A blue field and three diagonal stripes set from lower hoist to upper fly. The colours of the stripes are white and golden yellow. The effect created by the arrangement of the stripes is meant to represent Yukon's many mountains. Blue is for the French people and the sky. White is for winter and snow. Yellow represents the gold rush and the Franco-Yukonnais contributions to history of the territory. |

|

1986–present | Flag of the Fédération des Francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador (Franco-Terreneuviens) | Three unequal panels of blue, white, and red, with two yellow sails set on the line between the white and red panels. The sail on top is charged with a spruce twig, while the bottom sail is charged with a pitcher flower. |

|

1992–present | Flag of the Franco-Ténois | A polar bear on a snowy hill, looking forward towards a snowflake/Fleur-de-lis combined, representing the French community of the Northwest Territories of Canada. |

|

2002–present | Flag of the Franco-Nunavois | Blue that represents the Arctic sky and white recalls the snow, abundantly present on the territory. The principal shape represent an igloo, and under this one, the inukshuk which symbolise the human presence. A single dandelion flower grows from beneath it. |

Other ethnic groups

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2006?–present? | Flag of Black Canadians | The Canadian national flag with black instead of red.[16] |

|

2008–present | Flag of Gaelic Canadians | Adopted by the Comhairle na Gàidhlig (The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia), the salmon represents the gift of knowledge in the Gaelic storytelling traditions of Nova Scotia, Scotland and Ireland and the Isle of Man. The "G" represents the Gaelic language and the ripples are the manifestations of the language through its rich culture of song, story, music, dance and custom and belief system.[17] |

|

2021–present | Flag of Black Nova Scotians | The red represents blood and sacrifice. The gold conveys cultural richness. The green symbolizes fertility and growth. The black stands for the people.

The wave in the bottom centre has a dual meaning, representing the ocean and movements as well as honouring the journey of African Nova Scotian ancestors through the middle passage during the slave trade. On the left is half of a stylized heart (a version of the Sankofa symbol) with a yin and yang-like symbol embedded to represent heartbreak balanced with awareness. The image is encompassed with an incomplete circle representing those things absent but yet to come.[18] |

|

2024–present | Flag of Irish Heritage Quebec | A yellow Celtic cross on a green background with a white crenellated border. Inspired by the flag of Quebec City.[19] |

Municipal

[edit]Historical

[edit]Historical national flags

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1497–1707 | Flag on John Cabot's ship, and used during the English colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union. | White Ensign, St George's Cross. |

|

1621–1707 | Flag used during the Scottish colonization of the Americas before the Act of Union. | White saltire on blue ensign, St. Andrew's Cross. |

|

1608 | Etandart François[20] | Possibly flown by Samuel de Champlain at Quebec City.[21] |

|

16th c. on | Ensign of the Royal French Navy | A plain white banner, as naval ensign, also used on land, especially on fortifications, as symbol of authority of the French state.[22] |

|

1664 | Flag of the Compagnie française des Indes occidentales | A white banner defaced with the Arms of France, three golden fleurs-de-lis on a blue escutcheon.[23] |

|

1689 | Merchant Flag of France | |

|

1707 | United Empire Loyalists (British North America) | United Empire loyalist flag which was similar to the earlier version of the Union Jack but had slight changes in the fimbriation width. The United Empire Loyalists brought this flag to British North America when they left the United States. In present-day Canada, the flag continues to be used as symbol of pride and heritage for loyalist townships and organizations.[24] |

|

1801–1964 | Union Flag (1801–1964); Canadian Royal Union Flag (1964–present) |

Royal

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1643 | Royal standard of France | |

|

1534–1763 | Royal Banner of France or "Bourbon Flag" was the most commonly used flag in New France[25][26][27][28] | The banner flag has three gold fleur-de-lis on a dark blue field arranged two and one |

|

1962–2022 | Royal standard of Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada | A banner of the Royal Arms of Canada defaced with a royal cypher of Queen Elizabeth II |

|

2014-2020 | Royal standard of Prince Andrew, Duke of York | No longer used after Andrew's withdrawal from public roles. |

|

2011–2022 | Royal standard of Prince William |

Coronation standards

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1937 and 1953 | Coronations of George VI and Elizabeth and Elizabeth II | Banner of arms of Royal Coat of Arms of Canada |

|

1911 | Coronation of George V and Mary | Banner of arms of Royal Coat of Arms of Canada |

Viceregal

[edit]Civil ensigns

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1892–1922 | Canadian Red Ensign as authorized for use as a civil ensign through Admiralty warrant. Informal use of the Canadian Red Ensign as a symbol of Canada began as early as 1868. | |

|

1907–1922 | 1907 informal version of the Canadian Red Ensign commonly used in western Canada. Note the inclusion of all the provincial emblems. | |

|

1922–1957 | 1922 version of the Canadian Red Ensign used from 1922 to 1957, which was also used as a de facto national flag. | |

|

1957–1965 | 1957 version of the Canadian Red Ensign that had evolved as the de facto national flag until 1965. |

Government ensigns

[edit]| Flag | Date | Description | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1868–1922 | A British colonial Blue Ensign defaced with the 1868 Great Seal of Canada | Since Confederation, worn by Canadian federal government ships, including of the Department of Marine and Fisheries, involved in tending lighthouses, performing search and rescue, ice-breaking, resupply of isolated outposts, and other services. Worn by Canadian government warships prior to formation of Naval Service of Canada/Royal Canadian Navy.[29][30] (Also from 1910-1911 as naval ensign, then 1911-1922 as naval jack.) |

|

1922–1957 | A British colonial Blue Ensign defaced with the 1921 Arms of Canada | Used by ships of various Canadian federal departments, including Department of Transport fleet from 1936 -1957.[31] (Also as naval jack 1922-1957.) |

|

1957–1965 | A British colonial Blue Ensign defaced with the 1957 Arms of Canada | Used by ships of various Canadian federal departments, including Canadian Marine Service (1959-1962), and Canadian Coast Guard (as ensign) from 1962-1965.[32] (Also as naval jack 1957-1965.) |

Newfoundland

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1904–1949 | Dominion of Newfoundland | |

|

1870–1904 | Newfoundland Colony | |

|

1862–1870 |

Rebellions

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1968–1971 | Front de libération du Québec | Flag of the FLQ as seen at demonstrations in Montreal and the U.S. between 1968 and 1971[33] |

|

1812–1821 | Pemmican War | Metis Flag |

|

1837 | Lower Canada Rebellion | This flag was created by Marie-Louise Félix, Émilie Berthelot and Marie-Louise-Zéphirine Labrie in 1837, also involved in the Association of Patriotic Ladies of the Deux-Montagnes County. We see a maple branch surmounted by a muskellunge, surrounded by a crown of cone and pine branches. The C would mean "Canada" (in the sense that this term had for the Patriots at the time) and JB would mean "Jean-Baptiste", the patron saint of "Canadians" since the creation of the Société Saint-Jean- Baptiste in 1834. The original is in Château Ramezay, in Montreal. |

|

1832–1838 | Patriote flag | The proposed flag for the Republic of Lower Canada (1838). It is still used today by some souverainists, in mostly 4 variants: the original, and three versions with the yellow star in the top left corner. Of which, two of them have Henri Julien's Patriot painting of 1904, one in colour and the other stylised in black and white. |

|

1837–1838 | Flag of the Republic of Canada | A blue-white-red vertical tricolour with two white stars representing the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada and a crescent moon representing the "hunter's clubs" that organized and led the insurrection affixed at the hoist.[34] |

|

1869-1870 | North-West Rebellion | Often mistaken as the flag used in the 1885 resistance, the flag used by the Provisional Government of Rupert's Land and the North-West was described in various ways. Most descriptions mention a fleur-de-lys, shamrock and a white background.[35][36] |

|

1885 | Provisional Government of Saskatchewan | The day of the provisional government's proclamation, Father Vital Fourmond, a witness, wrote "As a flag [Riel] chose the white flag of ancient France [with a royal blue shield bearing three golden fleurs de lys], saying that he was called to renew its ancient glories. On it he placed a large image of Mary's immaculate heart."[37] |

Other

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1827 | Flag of the short lived Republic of Madawaska which was situated between Canada and the US. | |

|

1868 | The Canadian Red Ensign used at Dominion Day celebrations in Barkerville, BC in support of Canadian Confederation, as Canada did not have an official flag.[38] | |

| 1910–1913 | Sledge flag used in Antarctica by C.S. Wright, a Canadian member of Robert Falcon Scott's Terra Nova Expedition. | ||

|

Post 1910–c. 1945 | British Empire flag | An unofficial flag of the British Empire featuring symbols of its constituent dominions and India. The Canadian coat of arms are present in the bottom left. It was flown by civilians as a display of patriotism on special occasions such as Empire Day. A surviving specimen from the British Empire Exhibition in 1924 is kept in the Canadian Flag Collection.[39] |

Proposed

[edit]The following is a list of flags proposed for the Canadian state.[40]

| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1895 | Sir Donald A. Smith's proposal | A British colonial Red Ensign with green maple leaf in lower fly.[41] |

|

Sir Sanford Fleming's proposal | A British colonial Red Ensign with a seven-pointed white star in the lower fly that represents the North Star as emblem of Canada its rays symbolizing its then seven provinces.[42][43] | |

|

H. Spencer Howell of the Canadian Club of Hamilton, Ontario's proposal | A British colonial Red Ensign with green maple leaf on white disc in lower fly.[44][45] | |

|

1896 | E. M. Chadwick's Proposed National Flag / Blue Ensign of Canada | A British Blue Ensign with three conjoined maple leaves in gold as emblem on the fly. Chadwick also proposed a Red Ensign with the same gold maple leaves as Canada's colonial/national emblem.[46] |

|

E. M. Chadwick's Proposed National Flag and Red Ensign of Canada | A British Red Ensign with three conjoined maple leaves in green on a white disc as badge on the fly. Chadwick also proposed a Blue Ensign with the same maple leaves in red on a white disc as Canada's colonial/national emblem.[47] | |

|

1897 | Barlow Cumberland's proposal | A British Red Ensign featuring a green maple leaf on a white diamond in the fly. The diamond is to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria and to distinguish the flag among other British colonial ensigns.[48][49] |

|

1902 | Design reported in the Daily Express to have been proposed as part of a series of Empire flags that would replace the Union Jack in representing individual territories of the British Empire[50] | The Cross of Saint George and the crown in the canton would have been present on all Empire flags to represent the English. In the top right would be the emblem of the territory flying the flag, and in this case, the coat of arms of Canada. A large sun in the centre symbolizes "the empire on which the sun never sets." |

|

1916 | Manitoba Free Press Proposal | Design inspired by the Australian flag. A British ensign with a white field, with the seven stars of the Big Dipper/Great Bear plus the North Star placed on the fly.[51] Further development of a proposal originally made in October 1909 by C. F. Hamilton in Collier's Canada (a white ensign as flag of Canada). Hamilton strongly criticized the Manitoba Free Press proposal for its use of 'republican' stars.[52] |

|

1920s | Minnie H. Bowen Proposal | Design featuring the white cross of France on a red field with Union Jack in canton, submitted to PM Mackenzie King's 1925 flag committee.[53] A similar redesign of the red and blue ensigns of Canada was considered by PM Sir Robert Borden's 1919 arms committee.[54] |

|

1925 | A. Fortescue Duguid Proposal | Proposed by Archer Fortescue Duguid as a "Canadian National Flag for Use Ashore" in June 1925. In 1939, the design was adopted as the headquarters flag of the 1st Division of the Canadian Army on the eve of their departure for Europe to serve in the Second World War. It served as the de facto, provisional flag of the Army until officially replaced by the Canadian Red Ensign in 1944. Duguid re-proposed the design as national flag in 1939 at the time it was adopted as the flag of the 1st Canadian Division and, despite the fact that it did not find favor with the troops, again in 1945.[55] |

|

1926 | Winner of the 1926 La Presse contest to design a national flag. Design credited concurrently to Edwin Tappan Adney, Charles Lapierre, Joseph-Edouard Roy, and Isidore Renaud.[56] | The white field recalls the first, "heroic" period of Canada under monarchical France, the Union Jack symbolizes loyalty to Great Britain, and the green maple leaf concretizes the present history of Canada and its aspirations.[57][58] Design submitted to the 1945-46 Parliamentary flag committee and one of the last to be eliminated from consideration.[59][60] |

|

1931 | Gérard Gallienne's Proposal | A blue-red-blue vertical triband fimbriated by white bars (pallets) with the Canadian coat of arms placed in the centre. The blue bars symbolize the Atlantic and Pacific oceans and Canada's National Motto, A mari usque ad mare ('From sea to sea'), and the red Canada's land.[61][62][63][64] |

|

1939 | Ephrem Côté's Proposal | A blue-white-red diagonal triband (white bend sinister on a field party per bend sinister blue and red), with a Union Jack in upper hoist, green maple leaf centre, and white fleur-de-lis lower fly.[65][66] |

|

c.1943 | Ligue du Drapeau National's proposal for Flag of Canada, endorsed by the Native Sons of Canada in 1946 | A red and white field divided diagaonally (per bend) defaced by a green maple leaf placed in the centre. Proposed by the Ligue du Drapeau National c. 1943.[67] One of the two final designs considered by the 1945-1946 parliamentary joint committee to choose a national flag.[68] Adopted and promoted by the Native Sons of Canada from 1946.[69][70] |

|

1944 | Eugène Achard's Proposal | On a blue field, a white symmetric cross surmounted by a red cross, charged by a green maple leaf ringed by nine white five-pointed stars.[71] |

|

1945 | A. Fortescue Duguid's second Proposal | Three red maple leaves conjoined with a single stem on a white field. Originally proposed by Canadian armed forces heraldist and vexillologist Col. A. Fortecue Duguid during the 1945-1946 Parliamentary committee deliberations.[72] Later re-proposed by PM Pearson's parliamentary secretary John R. Matheson in 1963.[73] Publicly supported by ex-PM and opposition leader John Diefenbaker during 1964 Great Flag Debate.[74] |

|

1946 | Parliamentary Joint Committee's final selection | A red British ensign defaced with a large golden maple leaf outlined in white in the fly.[75][76][77] Selected by a 1945-1946 Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons but never submitted to parliament for a vote.[78] |

|

D. F. Stedman's proposal | A blue field with red and white diagonal and vertical bars of varying breadth. Derived from the British Union Jack and French Tricolour and intended to represent British, French, and Native 'founding' peoples.[79] | |

|

1954 | Florian A. Legace's proposal - the 'Canadian Union Jack' | A white cross on a red and blue quartered field, a green maple leaf centre. White "Cross of Sacrifice" after usage of Canadian Legion. Deep red of Union Jack, royal blue quarters intended to be intermediate between dark blue of the Union Jack and azure of the Fleurdelisé Flag of Quebec. The points on the maple leaf symbolize its individual provinces and territories and its green colour Canada's natural resources and the evergreens found coast to coast.[80] |

|

John Lorne MacDougall's proposal | Red field with white side/flank in the hoist charged with a shield featuring the Union Jack of Great Britain and three golden fleurs-de-lis of royalist France/Quebec over which are three green maple leaves and a Tudor crown. One of several variants devised by an all-province study group of Liberal MPs convened by Bona Arsenault in 1954.[81][82] | |

|

Jean-François Pouliot's Proposal | Green, detailed maple leaf on a plain red field.[83][84] | |

|

1955 | Proposal of J.W. Bradfield of the Toronto Young Men's Canadian Club | Quartered banner - upper hoist red with three golden lions, lower fly blue with three white fleurs-de-lis, remaining two white with three red conjoined maple leaves.[85][86] |

|

Alan Beddoe's Proposal | A white field charged by three red maple leaves conjoined on one stem with narrow wavy vertical blue bars at hoist and fly.[87] | |

|

André Barbeau's Proposal | A white square centre panel charged with a forest green maple leaf, flanked by blue, white, red vertical bars at hoist and fly.[88] | |

|

1957 | Alfred Stagg's Proposal | Blue-white-blue vertical triband charged by a red maple leaf encircled by a red ring.[89] The distinctive leaf appears to be a silver maple rather than the more standard sugar maple. |

|

1958 | Jean Dubuc's Proposal | On a white field, a tripartite symmetric cross in red, white and blue, surmounted by a green maple leaf on a white disc. The white of the field symbolizes the First Nations and Inuit "still in possession of vast expanses of snow and ice of this country".[90] |

|

Vincent Dupuis's Proposal | Eleven red, white, and blue stripes with a white canton with green maple leaf. The stripes represent Canada's provinces and territories.[91] | |

|

1959 | Leslie Frost's Proposal | A Canadian Red Ensign with the Dominion Coat of Arms wreathed by ten maple leaves, representing Canada's ten provinces. Designed by the Premier of Ontario.[92] |

|

Marcel Boivin's Proposal | Four bands of white, blue, gold, and red. Recreation based on textual description (orientation of bands not specified).[93] | |

|

1962 | Luc-André Biron's Proposal | A green Compass rose on a white background, symbolizing both the North Star and the North magnetic pole, situated within the territory of Canada, as emblem of all Canadians without regard to race, ethnicity, or national origin.[94][95][96] |

|

1963 | Rolland Lavoie's Proposal | A disc divided in half vertically, coloured red and blue, on a white field. First Prize winner in the 1963 Weekend / Canadian Art magazine design contest.[97][98][99] |

|

James Sanders's Proposal | An abstractly stylized seven-point red maple leaf on a white field. Second Prize winner in the 1963 Weekend / Canadian Art magazine design contest.[100][101] | |

|

Leslie Coppold's Proposal | A blue and white vertically divided field with an abstractly stylized fifteen-point red maple leaf on the square white fly panel. One of five Fourth Prize winners in the 1963 Weekend / Canadian Art magazine design contest.[102][103] | |

|

Carl Dair's Proposal | An abstractly stylized five-point red maple leaf on a white field flanked by vertical blue bars. Honorable Mention in the 1963 Weekend / Canadian Art magazine design contest.[104] | |

|

Grant Hewlett's Proposal | A red field as square panel at fly with a white side or flank at hoist, charged with a green 19-point maple leaf. Honorable Mention in the 1963 Weekend / Canadian Art magazine design contest.[105] | |

|

1964 | Alan Beddoe's second proposal, made during the Great Flag Debate, favored by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson and popularly known as the Pearson Pennant. Parliamentary Committee "Group A" Finalist | A blue field with a white square containing a three-leaf maple. The blue sides were meant to represent John A. Macdonald's description of the Canadian Pacific Railway and Canada's geography, "From sea to sea". Beddoe first submitted a proposed flag of similar design in 1955.[106] The original mid-1964 draft version featured spikey, rounded heraldic maple leaves.[107] |

|

Reid Scott of the New Democratic Party's proposal, made during the Great Flag Debate. | A white field charged with a single red maple leaf and flanked by two vertical blue bars.[108] | |

|

Proposal made during the Great Flag Debate featuring four maple leaves | Four large maple leaves occupy the centre of the flag. Behind them is a white diamond on a blue background. The leaves are arranged similarly to the modern heraldic mark of the Prime Minister, and their stems form the Cross of Saint George in the middle. | |

|

Proposal made during the Great Flag Debate featuring one maple leaf | The background is like the British flag without the diagonal stripes, there is a green maple leaf in the centre and there are three stars on either side in the red stripe and two stars on either side in the vertical red stripe. | |

|

Proposal made during the Great Flag Debate featuring ten maple leaves | Ten maple leaves are spread across the flag, and they likely represent the provinces. On the left are red leaves on a red background. The right side features the same colours inverted. | |

|

Proposal for Flag of Canada, by George F. G. Stanley | A red-white-red vertical triband, a red field with a white pale, containing a single red 15-point maple leaf. Based on the flag of the Royal Military College of Canada, where Stanley served as Dean of Arts.[109][110] One of two designs Stanley suggested to John Matheson during the Great Flag Debate. | |

|

George F. G. Stanley's alternate proposal | A red-white-red horizontal triband, a red field with a white fess, containing a three-leaf maple branch. His second option suggested to John Matheson.[111] | |

|

George Matthias Bist's proposal | A critique and redesign of the Pearson Pennant, offered during the Great Flag Debate. Features a red stylized 9-point maple leaf (black maple) on a white square pale, with an 'air force blue' field, or bars on either side.[112] Design credited by John Matheson with inventing the Canadian pale.[113] | |

|

Proposal made during the Great Flag Debate featuring one maple leaf. "Group C" finalist considered by Parliamentary committee. | Identical to "Group B" final choice of 1964 Committee but with Union Flag and royal French banner with three fleurs-de-lis as cantonal charges in upper hoist and fly. Introduced ostensibly to placate supporters of Canadian Red Ensign,[114][115] eliminated in second to last round of voting. | |

|

Proposal made during Great Flag Debate, Parliamentary Committee "Group B" finalist and Committee final selection. | Final choice of 1964 Parliamentary Joint Committee. Features vertical triband, red-white-red colour scheme, and single maple leaf proposed by George Stanley, George Matthias Bist's broad pale, and 13-point maple leaf designed by Alan Beddoe.[116] | |

|

An intermediate manufactured prototype of the 1964 Parliamentary flag committee's final selection. | An intermediate redesign of the Parliamentary Joint Committee's final selection, featuring a variant 13-point maple leaf. Appears in press images taken in the month of December 1964, including a press agency photograph at the closure of Parliamentary debate[117] and a magazine cover depicting the new flag flying on Parliament Hill.[118] | |

|

1994 | Proposed flag for Canada, known as the Canadian Unity Flag | Blue vertical stripes replacing part of the red bands, in approximate proportion to population of French heritage. |

|

1996 | The Unilisé, a flag used by Canadian federalists in Quebec | A banner combining the flags of Canada and Quebec. Made in 1996 after the Quebec independence referendum by federalists who supported remaining with Canada to represent national unity. |

Regional

[edit]Official

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1994–present | Flag of Cape Breton Island | A white field with four narrow horizontal stripes at the bottom, blue over green over yellow over gray with a narrow black fimbriation. Toward the fly, the green bar rises to silhouette a hill or island. Toward the hoist is a green, stylized eagle in flight.

Despite not being widely used, the Eagle flag was officially recognized and adopted by the Nova Scotian government in 1994.[119] |

|

1938–present | Flag of Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean | A field party per fess, green and yellow, with a red-bordered grey ordinary cross; green represents the region's forests, yellow its agriculture, grey its industry and commerce, and red the vitality of the population |

Unofficial

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Disputed–present | Flag of Cape Breton Island | A field tierced per forest green and white, with a green saltire and yellow circle reading "Cape Breton Island" on the top, and "Canada" on the bottom, with a green stylized map of Cape Breton Island in the middle. The green is taken from the island's tartan.

Though being the most commonly used flag it is not the official flag and is disputed by supporters of the officially recognized 1993 flag designed by Kelly Gooding[119] |

|

1974–present | Flag of Labrador | A field party per fess, white and azure, with a green horizontal band across the centre and a spruce twig in the upper hoist |

|

1880s–present | Newfoundland Tricolour | A field tierced per pale green, white, and pink |

|

1949–present | Flag of Outer Bald Tusket Island | Flag used by one of the first micronations, named Principality of Outer Baldonia, it is sometimes used on fishing boats and on souvenirs. |

|

1988–present | Flag of Vancouver Island | A Blue Ensign defaced with the great seal of the Colony of Vancouver Island. Used informally today.[120] This unofficial flag was designed in the 1980s to retroactively represent the colony (1849–1866). In 1865 the Crown gave colonies permission to place their badges on the fly of the Blue Ensign; thus vexillologists could argue that this flag is official.[121] |

|

1988–present | Flag of Western Canada | Originally used by the Western Independence Party, it was designed in 1988 ahead of the party's first election. |

House flags of Canadian freight companies

[edit]| Flag | Date | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1965–present | Canada Steamship Lines | |

|

1958-1965 | ||

|

1867-1958 | Quebec Steamship Company and Canada Steamship Lines | |

|

1944–present | Coopérative de Transport Maritime et Aérien | The project differs in different periods of the company's activity. |

|

1811–2019 | Bowring Brothers | |

|

1893–1953 | Canadian Australasian Line | |

|

1919–1986 | Canadian National Steamship Company | |

|

1887–2005 | CP Ships | |

|

19th–1967 | Job Brothers & Co., Limited | |

|

1910–1916 | Royal Line |

Yacht clubs of Canada

[edit]| Burgee | Club |

|---|---|

|

Armdale Yacht Club |

|

Barrachois Harbour Yacht Club |

|

Bay of Quinte Yacht Club |

|

Bras d'Or Yacht Club |

|

Bronte Harbour Yacht Club |

|

Buffalo Canoe Club |

|

Dobson Yacht Club |

|

Etobicoke Yacht Club |

|

Northern Yacht Club |

|

Oakville Yacht Squadron |

|

Royal Hamilton Yacht Club |

|

Royal Lake of the Woods Yacht Club |

|

Royal St. Lawrence Yacht Club |

|

Royal Vancouver Yacht Club |

|

Royal Victoria Yacht Club |

|

Royal Canadian Yacht Club |

|

Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron |

|

Windsor Yacht Club |

|

Queen's University at Kingston (College team) |

|

University of British Columbia (College team) |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > Flag Etiquette in Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > Personal Flags and Standards". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ "Confirmation of the blazon of a Flag". Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. Official website of the Governor General. Retrieved 19 March 2025.

- ^ Bertosa, Brian (2023). "It Was Supposed to Be Blue: Roads Not Taken with the Canadian Armed Forces Naval Jack, 1967-68". Northern Mariner / Le Marin du Nord. 32 (4): 545–574. doi:10.25071/2561-5467.1045. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. "History of Canadian naval flags". Canada.ca. Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Perrin, William Gordon (1922). British Flags: Their Early History, and Their Development at Sea; With an Account of the Origin of the Flag as a National Device. London: Cambridge at The University Press. p. 121. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ "1963-1965: The birth of Canada's National Flag — Who's who". Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. 4 January 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ Canadian Heraldic Authority. "Canadian Coast Guard". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 8 April 2025.

- ^ McWilliam, Yvonne (November–December 1963). "The Story Behind Our Flags". News on the DOT. 14 (6): 6–8. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ a b "Flags of National Defence".

- ^ "The Navy League of Canada [Civil Institution]". 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Heritage Structure | Annex A – Cadet Flags". 12 October 2018.

- ^ "The Army Cadet League of Canada [Civil Institution]". 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b "The Army Cadet League of Canada [Civil Institution]". 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b Department of National Defence (2001-01-05). A-AD-200-000/AG-000 The Honours, Flags and Heritage Structure of the Canadian Forces Chap 4 Annex A. Directorate of History and Heritage.

- ^ "Afro-Canadian flags".

- ^ "Gaelic Flags (Canada)".

- ^ Currie, Brooklyn (February 15, 2021). "New official African Nova Scotian flag looking to connect past, present and future". CBC News.

- ^ Christopher Eby (7 January 2025). "Irish Heritage Quebec Unveils New Flag Design at Annual Meeting". The Flag Chronicle. Retrieved 14 May 2025.

- ^ Desjardins, Gustave (1874). Recherches sur les drapeaux français : oriflamme, bannière de France, marques nationales, couleurs du Roi, drapeaux de l'armée, pavillons de la marine. Paris: A. Morel et cie, éditeurs. p. Plate X. Retrieved 4 April 2025.

- ^ Stanley, George F. G. (1972). The Story of Canada's Flag, A Historical Sketch (Revised ed.). Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7700-0197-1. Retrieved 29 March 2025.

- ^ Vachon, Auguste. "Banniére de France et Pavillon Blanc en Nouvelle-France". Heraldic Science Héraldique. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ Vachon, Auguste. "Banniére de France et Pavillon Blanc en Nouvelle-France". Heraldic Science Héraldique. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ "The Loyalist Flag". UELAC. 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2024-12-26.

- ^ New York State Historical Association (1915). Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association with the Quarterly Journal: 2nd-21st Annual Meeting with a List of New Members. The Association.

It is most probable that the Bourbon Flag was used during the greater part of the occupancy of the French in the region extending southwest from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi, known as New France... The French flag was probably blue at that time with three golden fleur - de - lis ....

- ^ "Fleur-de-lys | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca.

At the time of New France (1534 to the 1760s), two flags could be viewed as having national status. The first was the banner of France — a blue square flag bearing three gold fleurs-de-lys. It was flown above fortifications in the early years of the colony. For instance, it was flown above the lodgings of Pierre Du Gua de Monts at Île Sainte-Croix in 1604. There is some evidence that the banner also flew above Samuel de Champlain's habitation in 1608. ..... the completely white flag of the French Royal Navy was flown from ships, forts and sometimes at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ "INQUINTE.CA | CANADA 150 Years of History ~ The story behind the flag". inquinte.ca.

When Canada was settled as part of France and dubbed "New France," two flags gained national status. One was the Royal Banner of France. This featured a blue background with three gold fleurs-de-lis. A white flag of the French Royal Navy was also flown from ships and forts and sometimes flown at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ W. Stewart Wallace (1948). The Encyclopedia of Canada, Vol. II, Toronto, University Associates of Canada. pp. 350–351.

During the French régime in Canada, there does not appear to have been any French national flag in the modern sense of the term. The "Banner of France", which was composed of fleur-de-lys on a blue field, came nearest to being a national flag, since it was carried before the king when he marched to battle, and thus in some sense symbolized the kingdom of France. During the later period of French rule, it would seem that the emblem...was a flag showing the fleur-de-lys on a white ground.... as seen in Florida. There were, however, 68 flags authorized for various services by Louis XIV in 1661; and a number of these were doubtless used in New France

- ^ McWilliam, Yvonne (November–December 1963). "The Story Behind Our Flags". News on the DOT. 14 (6): 6–8. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ "History of icebreaking in Canada". Canadian Coast Guard. Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2025.

- ^ McWilliam, Yvonne (November–December 1963). "The Story Behind Our Flags". News on the DOT. 14 (6): 6–8. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ McWilliam, Yvonne (November–December 1963). "The Story Behind Our Flags". News on the DOT. 14 (6): 6–8. Retrieved 15 March 2025.

- ^ Flags of the World (retrieved on 31 July 2007)

- ^ "Photos for Fort Malden National Historic Park". Yelp.com. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Begg, Alexander. "The Red River Troubles". The Globe (Letter to the Editor).

- ^ Osler, Edmund Boyd (1961). The Man Who Had to Hang Louis Riel. Longmans Green. p. 69.

- ^ Payment, Diane P (February 2009). "A National Feast Day, a Flag, and Anthem". The Free People - Li Gens Libres: A History of the Métis Community of Batoche, Saskatchewan (2 ed.). Calgary, AB, Canada: University of Calgary Press. ISBN 978-1-55238-239-4.

- ^ "Dominion Day and the "New" Canadian Flag". Barkerville Historic Town & Park. 1 July 2019. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Stevenson, Lorraine (23 May 2018). "Argyle museum waves the flag – all 1,300 of them". The Manitoba Co-operator. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Canada, flag proposals".

- ^ "Change in the national flag, discussed by Sir Donald A. Smith". The Montreal Star. May 25, 1895. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Sir Sandford Fleming, 1895". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 20 March 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 80

- ^ Howell, H. Spencer (Jul 10, 1895). "Flag Emblems Criticised". The Hamilton Spectator. Retrieved 31 March 2025.

- ^ Vachon, Auguste. "Banniére de France et Pavillon Blanc en Nouvelle-France". Heraldic Science Héraldique. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ Chadwick, E. M. (1896). "The Canadian Flag". Canadian Almanac. Toronto: The Copp, Clark Co., Ltd. pp. 227–228, plate facing 232. Retrieved 16 March 2025.

- ^ Chadwick (1896), pp. 227–228, plate facing 232

- ^ Cumberland, Barlow (1897). The story of the Union Jack: How it grew and what it is, particularly in its connection with the history of Canada. Toronto: William Briggs. pp. 176, 229–230. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Patterson, Bruce (2016). "The Red Ensign and the Maple Leaf: Canada's Two Flag Traditions" (PDF). Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 23: 4. doi:10.5840/raven2016233. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "A British Empire Flag". The New York Times. The London Express. 9 February 1902. p. 3. Retrieved 20 August 2023 – via The New York Times Archives.

- ^ W.J.H. (January 26, 1916). "Heliograms". Manitoba Free Press. p. 9. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ "A Contribution to the Flag Discussion". Manitoba Free Press. February 11, 1920. p. 20. Retrieved 27 March 2025.

- ^ Brenda, Hartwell; Robinson, Jody. "Minnie H. Bowen Canadian Flag - c. 1920s". The Identity of English-speaking Quebec in 100 Objects. Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network.

- ^ Matheson, John Ross (1986). Canada's Flag: A Search for a Country. Belleville, Ontario: Mika Publishing Company. p. 15. ISBN 0-919303-01-3.

- ^ Reynolds, Ken (2007). ""To make the unmistakable signal 'Canada'": The Canadian Army's "Battle Flag" during the Second World War". Raven: A Journal of Vexillology. 14: 1–33. doi:10.5840/raven2007141. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ "Le modèle de drapeau primé par le jury au concour organisé par la "Presse" rappelle les temps héroiques du Canada, sa loyauté, et symbolise ses aspirations". No. 189, 42nd year. La Presse. 29 May 1926. pp. 17, 42. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ "Le modèle de drapeau primé par le jury au concour organisé par la "Presse" rappelle les temps héroiques du Canada, sa loyauté, et symbolise ses aspirations". No. 189, 42nd year. La Presse. 29 May 1926. pp. 17, 42. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ "Le drapeau national du Canada". La Presse. 11 January 1930. p. 24. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- ^ Matheson (1986), p. 62

- ^ "Il en reste 4 modèles". La Presse. 23 May 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 30 June 2025.

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Gérard Gallienne, 1931". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 23 August 2025.

- ^ "Un projet de drapeau canadien". Le Soleil. 3 September 1932. Retrieved 23 August 2025.

- ^ "Un projet de drapeau". Le Devoir. 9 March 1938. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ Gallienne, Gérard V. (11 August 1931). "Drapeau National Pour Le Canada". Scientific Canadian Mechanics' Magazine And Patent Office Record. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 101

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Ephrem Côté, 1939". The Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 21 October 2025.

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Ligue du drapeau national, c. 1943". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Stanley (1972), p. 55

- ^ La ligue du drapeau national du Canada (11 December 1948). "LE DRAPEAU CANADIEN QU'IL NOUS FAUT!" (PDF). L'Événement Journal. Retrieved 26 July 2025.

- ^ "Maple Maple Leaf flag campaign". CBC. CBC Newsmagazine. 28 December 1958. Retrieved 10 April 2025.

- ^ Patterson (2016), p. 6

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Fortescue Duguid and John Matheson, 1945-1964". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 20 March 2025.

- ^ Matheson (1986), p. 128

- ^ "Diefenbaker makes his flag choices". CBC. CBC. 16 December 1964. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: Parliamentary Committee, 1946". The Public Register of Arms, Flags, and Badges of Canada. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Bone, James (20 May 2021). "Donald Nelson Baird and the 1945–46 Parliamentary Flag Design Committee". Library and Archives Canada Blog. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- ^ Archbold, Rick (2002). I stand for Canada : the story of the Maple Leaf flag. Toronto: Macfarlane Walter & Ross. p. 64. ISBN 9781551991085. Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Matheson (1986), p. 63

- ^ Stedman, D. F. (1946-12-09). "A Flag Discussion: Width of Bars May Be Changed, Designs Are Heraldically Equivalent, (Chapter 7: Proportions of the Flag Design)". The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ Clingen, Ron (1961-04-03). "Determined Salesman: Coast-to-Coast Effort To Promote New Flag". Standard-Freeholder. Retrieved 20 April 2025.

- ^ McKeown, Robert (13 March 1954). "How Do You Like These Canadian Flags?". Vol. 4, no. 11. Weekend Picture Magazine. Retrieved 3 June 2025.

- ^ Nicholson, Patrick (25 January 1954). "Vancouver M.P. May Father Canada's Flag". The Vancouver News-Herald. Retrieved 3 June 2025.

- ^ Bain, George (25 September 1954). "Ottawa Letter by George Bain". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 8 September 2025.

- ^ Patterson (2016), p. 8

- ^ "Canada, flag proposals". Flags of the World (FOTW). FOTW. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ "Members of the Commons flag committee are surrounded by 1,200 designs for a new Canadian flag which they are considering". Library and Archves Canada. Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. 25 November 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 21

- ^ "New Flag Design". Star-Phoenix. CP Photo. 10 November 1955. Retrieved 29 May 2025.

- ^ "No Controversy in New Flag Plan". The Ottawa Citizen. 15 July 1957. Retrieved 21 April 2025.

- ^ Pass, Forrest (11 February 2025). "A Sweet Proposal… for a New Canadian Flag". The Discover Blog. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 10 April 2025.

- ^ "Design for National Flag". The Leader-Post. 4 July 1958. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ "'This Is The Flag I Like'--Mr. Frost". The Toronto Star. 17 January 1959. Retrieved 24 June 2025.

- ^ "Un drapeau sans artifice à quatre bandes, de couleur". Le Devoir. DNC. 30 January 1959. Retrieved 24 June 2025.

- ^ Biron, Luc-André (1962). Le drapeau canadien. Éditions de l'Homme. p. 83. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ "City Archivist Urges Truly National Flag". The Montreal Star. May 30, 1963. Retrieved 17 September 2025.

- ^ Patterson (2016), p. 9

- ^ "In Search of a Meaningful Canadian Symbolism". No. 87. Weekend/Canadian Art. September 1963. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 65

- ^ "Proposed Flag for Canada: the Canadian Art / Weekend Magazine, 1963". The Public Register of Arms. The Governor General of Canada. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ "In Search of a Meaningful Canadian Symbolism". No. 87. Canadian Art. September 1963. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 65

- ^ "In Search of a Meaningful Canadian Symbolism". No. 87. Canadian Art. September 1963. p. 273. Retrieved 25 April 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 65

- ^ "In Search of a Meaningful Canadian Symbolism". No. 87. Canadian Art. September 1963. Retrieved 3 April 2025.

- ^ "In Search of a Canadian Flag". No. 36. Weekend Magazine. September 1963. Archived from the original on 25 April 2025. Retrieved 30 May 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 21

- ^ "Legionnaires boo PM Pearson over flag design". CBC. CBC. 19 May 1964. Retrieved 11 April 2025.

- ^ "Debate Will Open Monday". The Standard. Canadian Press. 11 June 1964. Retrieved 1 May 2025.

- ^ Stanley, George F. G. "Dr. G.F.G. Stanley's Flag Memorandum to John Matheson, 23 March 1964". Retrieved 17 March 2025.

- ^ Stanley, George F. G. (25 November 2016). "Letter from G.F.G. Stanley, Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College of Canada, to John Matheson, Member of Parliament for Leeds, Ontario, relating to the design of a new Canadian flag". Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. Government of Canada / Gouvernement du Canada. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ Stanley, George F. G. (25 November 2016). "Letter from G.F.G. Stanley, Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College of Canada, to John Matheson, Member of Parliament for Leeds, Ontario, relating to the design of a new Canadian flag". Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. Government of Canada / Gouvernement du Canada. Retrieved 19 April 2025.

- ^ Bist, George Matthias (25 November 2016). "Flag Design". Library and Archives Canada/Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. Retrieved 14 March 2025.

- ^ Matheson (1986), pp. 125–6, 249

- ^ Matheson (1986), p. 146

- ^ "Are the Conservatives playing politics with the Canadian flag? - National | Globalnews.ca".

- ^ "1963-1965: The birth of Canada's National Flag — Who's who". Government of Canada/Gouvernement du Canada. 4 January 2023. Retrieved 18 March 2025.

- ^ Matheson, John. "The Great Flag Debate". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ Archbold (2002), p. 107

- ^ a b "Woman wants Cape Breton flag designed by her daughter recognized | Saltwire". www.capebretonpost.com. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ FOTW Flags of the World: Vancouver Island (British Colony, Canada)

- ^ Flags of Canada: British Columbia

External links

[edit]List of Canadian flags

View on GrokipediaThe list of Canadian flags enumerates the official and historical ensigns associated with Canada, prominently featuring the national flag—a red-white-red tricolour with an eleven-pointed red maple leaf at the centre, adopted following the Great Flag Debate and proclaimed by Queen Elizabeth II on January 28, 1965, before its first hoisting on Parliament Hill on February 15, 1965.[1] This catalogue extends to the distinct flags of Canada's ten provinces and three territories, which embody regional heraldic traditions and were incorporated into the national order of precedence;[2] personal standards for members of the Royal Family, with Canada leading Commonwealth realms in designing such individualized banners beyond the sovereign's;[3] and various institutional flags for entities like the Canadian Armed Forces, the Governor General, and the Supreme Court, alongside historical precedents including the Union Jack and the Canadian Red Ensign used de facto from the late 19th century until 1965.[4]

National, Provincial, and Territorial Flags

National flags

The National Flag of Canada consists of two vertical red bands of equal width on the hoist and fly sides, separated by a white central field bearing a stylized red maple leaf with eleven points. Approved by Parliament on December 15, 1964, it was proclaimed by Queen Elizabeth II on January 28, 1965, and first raised on Parliament Hill on February 15, 1965, marking the end of the Great Flag Debate.[1] [5] The design, inspired by a proposal from military historian George Stanley, symbolizes Canadian identity and unity, drawing from the maple leaf's long-standing cultural significance.[6] Prior to 1965, the Canadian Red Ensign served as the de facto national flag from 1868, featuring the British Red Ensign base with the shield of Canada's coat of arms in the fly.[7] This flag gained official status for maritime use in 1895 and was widely flown on government buildings, though never formally designated as the national flag by statute.[8] The Royal Union Flag, representing Canada's ties to the United Kingdom, was also recognized as an official flag alongside the Red Ensign until the maple leaf design's adoption.[7] These predecessors reflected Canada's evolution from colonial dependency toward distinct nationhood, with the 1965 change emphasizing independence from overt British symbolism.[1]Provincial flags

The ten provinces of Canada maintain distinct official flags, adopted primarily in the mid-20th century to symbolize regional history, geography, and identity. These flags often draw from coats of arms, British colonial heritage, natural resources, and cultural elements, reflecting the provinces' unique contributions to the federation. Most were formalized between 1948 and 1980, coinciding with a period of national flag development and provincial assertion of symbols. Alberta's flag, proclaimed into force on June 1, 1968, displays the provincial shield of arms centered on a royal ultramarine blue field representing the province's skies. The shield depicts snow-capped Rocky Mountains, green foothills and prairies, and golden wheat fields under a St. George's Cross, with proportions of 1:2 and the shield occupying 7/11 of the flag's height.[9] British Columbia adopted its flag on July 20, 1960, featuring a white field with the Royal Union Flag in the upper third defaced by a golden crown symbolizing ties to the monarchy, three wavy blue bars below representing the Pacific Ocean, and a setting golden sun in the upper hoist evoking the province's role as a western gateway.[10] Manitoba's flag received royal approval in October 1965 and was officially proclaimed that year, resembling a red ensign with the Union Jack in the upper hoist quarter and the provincial shield in the fly: a white Cross of St. George charged with the provincial coat featuring a red bison on green prairies.[11] New Brunswick's flag was proclaimed on February 24, 1965, based on the coat of arms granted in 1868, showing a yellow field with a red lion passant in chief, a white-sailed galleon on waves in base, and the motto "Spem Reduxit" (Hope Restored).[12] Newfoundland and Labrador's flag, designed by Christopher Pratt and adopted in 1980, consists of a white field symbolizing snow and ice, with blue triangles from the lower corners representing the sea, a red central panel for human effort, and a gold arrowhead pointing forward denoting confidence in the future; the design evokes the province's two main landmasses.[13] Nova Scotia's flag, rooted in a 1625 Scottish royal grant and officially recognized in 1929, bears a white field with a blue saltire (St. Andrew's Cross) and at its center the shield of Scotland's Royal Arms: a red lion rampant on gold within a double red tressure.[14] Ontario's flag was adopted in 1965, featuring a red field with the Union Jack in the upper hoist canton—acknowledging British heritage—and the provincial shield in the fly: a white St. George's Cross bearing three gold maple leaves on green.[15] Prince Edward Island's flag, modeled on the coat of arms from a 1905 royal warrant and adopted in 1964, comprises red-white-red vertical tribands bordered on three edges by alternating red and white rectangles, with the arms spanning the center: a red lion passant over three silver oak saplings on green.[16] Quebec, the first province to adopt an official flag on January 21, 1948, uses a blue field with a white cross dividing it into four quadrants, each containing a white fleur-de-lis recalling French royal banners and the province's Catholic heritage.[17] Saskatchewan's flag, adopted in 1969, divides horizontally into green (northern forests) over gold (wheat fields), with the shield of arms—featuring a lion holding a sheaf of wheat above two more sheaves—centered in the upper third.[18]Territorial flags

The three territories of Canada—Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut—each have official flags adopted to symbolize their unique geography, history, and cultural elements. These flags were selected through legislative processes or public competitions, reflecting the territories' distinct identities within the Canadian federation. Unlike provincial flags, territorial flags often emphasize natural features and Indigenous influences, with designs approved by territorial councils or the Governor General.[19] The flag of Yukon features three nearly equal vertical stripes of green, white, and sky blue from left to right, with the territorial coat of arms centered on the white stripe. The green stripe represents the territory's forests, the white evokes snow-covered tundra, and the blue signifies abundant lakes and rivers. The coat of arms, granted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1960, includes a mountain ram and a trapper's provisions, underscoring Yukon's rugged landscape and resource-based heritage. The design emerged as the winner of a 1967 territory-wide competition and was officially adopted via ordinance assented to on December 1, 1967, taking effect on March 1, 1968.[20][21] The flag of the Northwest Territories displays the territorial coat of arms centered on a white field, bordered by narrow horizontal blue stripes at the top and bottom representing the northern skies and waters. The coat of arms, granted by royal warrant on December 31, 1956, incorporates a black and white polar bear atop a jagged white field symbolizing ice floes, flanked by two gold foxes and a red wavy line denoting the Mackenzie River, with a compass rose above evoking exploration. These elements highlight the territory's Arctic environment, wildlife, and historical fur trade economy. The flag was adopted by ordinance of the Council of the Northwest Territories, assented to on January 1, 1969, replacing the Union Jack as the primary territorial ensign.[22][23] The flag of Nunavut is a vertical bicolour divided equally between yellow (or gold) on the hoist side and white on the fly, with a red inuksuk silhouette centered astride the division and a blue eight-pointed star-like shape arching above it to evoke the aurora borealis. The inuksuk, a traditional Inuit stone landmark used for navigation and hunting, symbolizes safety, hospitality, and unity; the gold represents the mineral wealth of the land, white the snow, and blue the northern skies and compassion of the people. The design was chosen from public submissions and granted by warrant from Governor General Roméo LeBlanc on April 1, 1999, coinciding with Nunavut's creation as a territory carved from the eastern Northwest Territories.[24]Royal Flags

Standards of the monarch

The Royal Standard of Canada serves as the personal flag of the monarch in their capacity as Sovereign of Canada, flown to indicate the monarch's presence on buildings, residences, and vehicles used during official visits.[25] It takes precedence over all other flags when displayed and is reserved for official use, with reproduction prohibited without authorization.[25] The flag consists of the banner form of the escutcheon from the Royal Arms of Canada, adopted as a permanent design for all future monarchs.[3] The design features a quartered shield representing the historic ties to England (three golden lions passant guardant on red), Scotland (a red lion rampant within a double tressure on gold), Ireland (a gold harp on blue), and France (three golden fleurs-de-lis on blue), with three red maple leaves conjoined at the stem on a white chief symbolizing Canada.[25] Unlike the personal flag used by Queen Elizabeth II from 1962 to 2022, which incorporated a blue disc bearing her cypher, the current standard omits such individualized elements to ensure its timeless application.[3] Approved by King Charles III in May 2023 prior to his coronation, the flag was prepared by the Canadian Heraldic Authority and first unveiled to mark the commencement of his reign as King of Canada on September 8, 2022.[25] The Royal Arms of Canada, upon which the standard is based, were originally proclaimed by royal warrant on November 21, 1921.[25]Standards of other royal family members

Personal standards for other members of the Canadian royal family are heraldic flags developed by the Canadian Heraldic Authority to denote the bearer's presence, typically flown from vehicles or buildings during official visits. Canada became the first Commonwealth realm to create such distinct personal flags for non-sovereign royals, with designs based on the banner of the Royal Arms of Canada, differenced by a white label of three points and a central blue roundel encircled by a wreath of golden maple leaves containing the individual's cypher or badge.[3] These standards take precedence over other flags but do not displace the national flag or the sovereign's standard.[26] The standard of the Prince of Wales, the heir apparent, features the banner of the Arms of Canada charged with a three-point white label and a central blue disc bearing a wreath of golden maple leaves enclosing the badge of the Prince of Wales (a plume of three ostrich feathers argent issuant from a coronet or). It was approved by Queen Elizabeth II on May 31, 2011, and registered on September 15, 2011.[27] [3] The Princess Royal's standard employs the same base elements, with the white label's chief point bearing a red heart surmounted by a crown, and the other points red crosses, alongside a central blue disc with her cypher "A" beneath a coronet within the maple wreath. Approved on May 8, 2013, and registered July 15, 2013, it reflects her position as the sovereign's eldest daughter.[28] [3] The Duke of York's standard includes a white label with a blue anchor in the dexter chief point, and a central disc with his cypher "A" and coronet. It was approved on May 15, 2014.[29] [3] The Duke of Edinburgh's standard bears a white label charged with a Tudor rose in the sinister chief point, paired with his cypher "E" and coronet in the central disc. Created in the mid-2010s alongside others, it signifies his role as a son of the late sovereign.[3] A generic standard exists for other royal family members lacking personal flags, featuring the banner of the Arms of Canada differenced by an undifferenced white label of three points (the chief with a red cross of St. George) and a central blue roundel with a plain maple wreath, without an individualized cypher.[30]Viceregal and Administrative Flags

Governor General's flags