Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Substance abuse

View on Wikipedia| Substance misuse | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Drug misuse, drug abuse, substance use disorder, substance misuse disorder |

| |

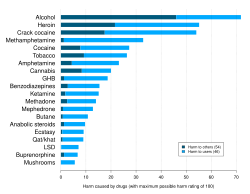

| Table from the 2010 ISCD study ranking various drugs (legal and illegal) based on statements by drug-harm experts.[1] | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Complications | Drug overdose |

| Frequency | 27 million[2][3] |

| Deaths | 1,106,000 US residents (1968–2020)[4] |

Substance misuse, also known as drug misuse or, in older vernacular, substance abuse, is the use of a drug in amounts or by methods that are harmful to the individual or others. It is a form of substance-related disorder, differing definitions of drug misuse are used in public health, medical, and criminal justice contexts. In some cases, criminal or anti-social behavior occurs when some persons are under the influence of a drug, and may result in long-term personality changes in individuals.[5] In addition to possible physical, social, and psychological harm, the use of some drugs may also lead to criminal penalties, although these vary widely depending on the local jurisdiction.[6]

Drugs most often associated with this term include alcohol, amphetamines, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, methaqualone, and opioids. The exact cause of substance abuse is sometimes clear, but there are two predominant theories: either a genetic predisposition or most times a habit learned or passed down from others, which, if addiction develops, manifests itself as a possible chronic debilitating disease.[8] It is not easy to determine why a person misuses drugs, as there are multiple environmental factors to consider. These factors include not only inherited biological influences (genes), but there are also mental health stressors such as overall quality of life, physical or mental abuse, luck and circumstance in life and early exposure to drugs that all play a huge factor in how people will respond to drug use.[9]

In 2010, about 5% of adults (230 million) used an illicit substance.[2] Of these, 27 million have high-risk drug use—otherwise known as recurrent drug use—causing harm to their health, causing psychological problems, and or causing social problems that put them at risk of those dangers.[2][3] In 2015, substance use disorders resulted in 307,400 deaths, up from 165,000 deaths in 1990.[10][11] Of these, the highest numbers are from alcohol use disorders at 137,500, opioid use disorders at 122,100 deaths, amphetamine use disorders at 12,200 deaths, and cocaine use disorders at 11,100.[10]

Classification

[edit]Public health definitions

[edit]

Public health practitioners have attempted to look at substance use from a broader perspective than the individual, emphasizing the role of society, culture, and availability. Some health professionals choose to avoid the terms alcohol or drug "abuse" in favor of language considered more objective, such as "substance and alcohol type problems" or "harmful/problematic use" of drugs. The Health Officers Council of British Columbia — in their 2005 policy discussion paper, A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada — has adopted a public health model of psychoactive substance use that challenges the simplistic black-and-white construction of the binary (or complementary) antonyms "use" vs. "abuse".[12] This model explicitly recognizes a spectrum of use, ranging from beneficial use to chronic dependence.

Medical definitions

[edit]

'Drug abuse' is no longer a current medical diagnosis in either of the most used diagnostic tools in the world, the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), and the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD). According to the DSM, substance use disorder (SUD) is used to describe the wide range of the disorder, from a mild form to a severe state of chronically relapsing, compulsive pattern of drug taking which include cannabis, alcohol, caffeine, hallucinogens, hypnotics, opioids, anxiolytics, inhalants, tobacco, and sedatives as well as other, possibly unknown, substances.[14]

Value judgment

[edit]

History professor Philip Jenkins suggests that there are two issues with the term "drug abuse". First, what constitutes a drug is debatable. For instance, GHB, a naturally occurring substance in the central nervous system is considered a drug, and is illegal in many countries, while nicotine is not officially considered a "drug" in most countries.

Second, the word "abuse" implies a recognized standard of use for any substance. Drinking an occasional glass of wine is considered acceptable in most Western countries, while drinking several bottles is seen as abuse. Strict temperance advocates, who may or may not be religiously motivated, would see drinking even one glass as abuse. Similarly, adopting the view that any (recreational) use of cannabis or substituted amphetamines constitutes drug abuse implies a decision made that the substance is harmful, even in minute quantities.[16] In the U.S., drugs have been legally classified into five categories; these are schedule I, II, III, IV, or V in the Controlled Substances Act. The drugs are classified on their deemed potential for abuse.

The usage of some drugs is strongly correlated.[17] For example, the consumption of seven illicit drugs (amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, legal highs, LSD, and magic mushrooms) is correlated and the Pearson correlation coefficient r>0.4 in every pair of them; consumption of cannabis is strongly correlated (r>0.5) with the usage of nicotine (tobacco), heroin is correlated with cocaine (r>0.4) and methadone (r>0.45), and is strongly correlated with crack (r>0.5)[17]

Drug misuse

[edit]Drug misuse is a term used commonly when prescription medication with sedative, anxiolytic, analgesic, or stimulant properties is used for mood alteration or intoxication ignoring the fact that overdose of such medicines can sometimes have serious adverse effects. It sometimes involves drug diversion from the individual for whom it was prescribed.

Prescription misuse has been defined differently and rather inconsistently based on the status of drug prescription, the uses without a prescription, intentional use to achieve intoxicating effects, route of administration, co-ingestion with alcohol, and the presence or absence of dependence symptoms.[18][19] Chronic use of certain substances leads to a change in the central nervous system known as a "tolerance" to the medicine such that more of the substance is needed in order to produce desired effects. With some substances, stopping or reducing use can cause withdrawal symptoms to occur,[20] but this is highly dependent on the specific substance in question.

The rate of prescription drug misuse is fast overtaking illegal drug use in the United States. According to the National Institute of Drug Abuse, 7 million people were taking prescription drugs for nonmedical use in 2010. Among 12th graders, nonmedical prescription drug use is now second only to cannabis.[21] In 2011, "Nearly 1 in 12 high school seniors reported nonmedical use of Vicodin; 1 in 20 reported such use of OxyContin."[22] Both of these drugs contain opioids. Fentanyl is an opioid that is 100 times more potent than morphine, and 50 times more potent than heroin.[23] A 2017 survey of 12th graders in the United States, found misuse of OxyContin of 2.7 percent, compared to 5.5 percent at its peak in 2005.[24] Misuse of the combination hydrocodone/paracetamol was at its lowest since a peak of 10.5 percent in 2003.[24] This decrease may be related to public health initiatives and decreased availability.[24]

Avenues of obtaining prescription drugs for misuse are varied: sharing between family and friends, illegally buying medications at school or work, and often "doctor shopping" to find multiple physicians to prescribe the same medication, without the knowledge of other prescribers.

Increasingly, law enforcement is holding physicians responsible for prescribing controlled substances without fully establishing patient controls, such as a patient "drug contract". Concerned physicians are educating themselves on how to identify medication-seeking behavior in their patients, and are becoming familiar with "red flags" that would alert them to potential prescription drug abuse.[25]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]| Drug | Drug class | Physical harm |

Dependence liability |

Social harm |

Avg. harm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methamphetamine | CNS stimulant | 3.00 | 2.80 | 2.72 | 2.92 |

| Heroin | Opioid | 2.78 | 3.00 | 2.54 | 2.77 |

| Cocaine | CNS stimulant | 2.33 | 2.39 | 2.17 | 2.30 |

| Barbiturates | CNS depressant | 2.23 | 2.01 | 2.00 | 2.08 |

| Methadone | Opioid | 1.86 | 2.08 | 1.87 | 1.94 |

| Alcohol | CNS depressant | 1.40 | 1.93 | 2.21 | 1.85 |

| Ketamine | Dissociative anesthetic | 2.00 | 1.54 | 1.69 | 1.74 |

| Benzodiazepines | Benzodiazepine | 1.63 | 1.83 | 1.65 | 1.70 |

| Amphetamine | CNS stimulant | 1.81 | 1.67 | 1.50 | 1.66 |

| Tobacco | Tobacco | 1.24 | 2.21 | 1.42 | 1.62 |

| Buprenorphine | Opioid | 1.60 | 1.64 | 1.49 | 1.58 |

| Cannabis | Cannabinoid | 0.99 | 1.51 | 1.50 | 1.33 |

| Solvent drugs | Inhalant | 1.28 | 1.01 | 1.52 | 1.27 |

| 4-MTA | Designer SSRA | 1.44 | 1.30 | 1.06 | 1.27 |

| LSD | Psychedelic | 1.13 | 1.23 | 1.32 | 1.23 |

| Methylphenidate | CNS stimulant | 1.32 | 1.25 | 0.97 | 1.18 |

| Anabolic steroids | Anabolic steroid | 1.45 | 0.88 | 1.13 | 1.15 |

| GHB | Neurotransmitter | 0.86 | 1.19 | 1.30 | 1.12 |

| Ecstasy | Empathogenic stimulant | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.09 |

| Alkyl nitrites | Inhalant | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.92 |

| Khat | CNS stimulant | 0.50 | 1.04 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

Notes about the harm ratings

The Physical harm, Dependence liability, and Social harm scores were each computed from the average of three distinct ratings.[13] The highest possible harm rating for each rating scale is 3.0.[13] Physical harm is the average rating of the scores for acute binge use, chronic use, and intravenous use.[13] Dependence liability is the average rating of the scores for intensity of pleasure, psychological dependence, and physical dependence.[13] Social harm is the average rating of the scores for drug intoxication, health-care costs, and other social harms.[13] Average harm was computed as the average of the Physical harm, Dependence liability, and Social harm scores. | |||||

Depending on the actual compound, drug abuse including alcohol may lead to health problems, social problems, morbidity, injuries, unprotected sex, violence, deaths, motor vehicle accidents, homicides, suicides, physical dependence or psychological addiction.[26]

There is a high rate of suicide in alcoholics and other drug abusers. The reasons believed to cause the increased risk of suicide include the long-term abuse of alcohol and other drugs causing physiological distortion of brain chemistry as well as the social isolation.[27] Another factor is the acute intoxicating effects of the drugs may make suicide more likely to occur. Suicide is also very common in adolescent alcohol abusers, with 1 in 4 suicides in adolescents being related to alcohol abuse.[28] In the US, approximately 30% of suicides are related to alcohol abuse. Alcohol abuse is also associated with increased risks of committing criminal offences including child abuse, domestic violence, rapes, burglaries and assaults.[29]

Drug abuse, including alcohol and prescription drugs, can induce symptomatology which resembles mental illness. This can occur both in the intoxicated state and also during withdrawal. In some cases, substance-induced psychiatric disorders can persist long after detoxification, such as prolonged psychosis or depression after amphetamine or cocaine abuse. A protracted withdrawal syndrome can also occur with symptoms persisting for months after cessation of use. Benzodiazepines are the most notable drug for inducing prolonged withdrawal effects with symptoms sometimes persisting for years after cessation of use. Both alcohol, barbiturate as well as benzodiazepine withdrawal can potentially be fatal. Abuse of hallucinogens, although extremely unlikely, may in some individuals trigger delusional and other psychotic phenomena long after cessation of use. This is mainly a risk with deliriants, and most unlikely with psychedelics and dissociatives.

Cannabis may trigger panic attacks during intoxication and with continued use, it may cause a state similar to dysthymia.[30] Researchers have found that daily cannabis use and the use of or low-potency indoor grown cannabis are independently associated with a higher chance of developing schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders.[31][32][33]

Severe anxiety and depression are often induced by sustained alcohol abuse. Even sustained moderate alcohol use may increase anxiety and depression levels in some individuals. In most cases, these drug-induced psychiatric disorders fade away with prolonged abstinence.[34] Similarly, although substance abuse induces many changes to the brain, there is evidence that many of these alterations are reversed following periods of prolonged abstinence.[35]

Impulsivity

[edit]Impulsivity is characterized by actions based on sudden desires, whims, or inclinations rather than careful thought.[36] Individuals with substance abuse have higher levels of impulsivity,[37] and individuals who use multiple drugs tend to be more impulsive.[37] A number of studies using the Iowa gambling task as a measure for impulsive behavior found that drug using populations made more risky choices compared to healthy controls.[38] There is a hypothesis that the loss of impulse control may be due to impaired inhibitory control resulting from drug induced changes that take place in the frontal cortex.[39] The neurodevelopmental and hormonal changes that happen during adolescence may modulate impulse control that could possibly lead to the experimentation with drugs and may lead to addiction.[40] Impulsivity is thought to be a facet trait in the neuroticism personality domain (overindulgence/negative urgency) which is prospectively associated with the development of substance abuse.[41]

Screening and assessment

[edit]The screening and assessment process of substance use behavior is important for the diagnosis and treatment of substance use disorders. Screeners is the process of identifying individuals who have or may be at risk for a substance use disorder and are usually brief to administer.[42][43] Assessments are used to clarify the nature of the substance use behavior to help determine appropriate treatment.[42] Assessments usually require specialized skills, and are longer to administer than screeners.

Given that addiction manifests in structural changes to the brain, it is possible that non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging could help diagnose addiction in the future.[35]

Targeted assessments

[edit]There are several different screening tools that have been validated for use with adolescents such as the CRAFFT Screening Test[44] and in adults the CAGE questionnaire.[45] Some recommendations for screening tools for substance misuse in pregnancy include that they take less than 10 minutes, should be used routinely, include an educational component. Tools suitable for pregnant women include i.a. 4Ps, T-ACE, TWEAK, TQDH (Ten-Question Drinking History), and AUDIT.[46]

Treatment

[edit]Psychological

[edit]From the applied behavior analysis literature, behavioral psychology, and from randomized clinical trials, several evidenced based interventions have emerged: behavioral marital therapy, motivational Interviewing, community reinforcement approach, exposure therapy, contingency management[47][48] They help suppress cravings and mental anxiety, improve focus on treatment and new learning behavioral skills, ease withdrawal symptoms and reduce the chances of relapse.[49]

In children and adolescents, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)[50] and family therapy[51] currently has the most research evidence for the treatment of substance abuse problems. Well-established studies also include ecological family-based treatment and group CBT.[52] These treatments can be administered in a variety of different formats, each of which has varying levels of research support[53] Research has shown that what makes group CBT most effective is that it promotes the development of social skills, developmentally appropriate emotional regulatory skills and other interpersonal skills.[54] A few integrated[55] treatment models, which combines parts from various types of treatment, have also been seen as both well-established or probably effective.[52] A study on maternal alcohol and other drug use has shown that integrated treatment programs have produced significant results, resulting in higher negative results on toxicology screens.[55] Additionally, brief school-based interventions have been found to be effective in reducing adolescent alcohol and cannabis use and abuse.[56] Motivational interviewing can also be effective in treating substance use disorder in adolescents.[57][58]

Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous are widely known self-help organizations in which members support each other abstain from substances.[59] Social skills are significantly impaired in people with alcoholism due to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol on the brain, especially the prefrontal cortex area of the brain.[60] It has been suggested that social skills training adjunctive to inpatient treatment of alcohol dependence is probably efficacious,[61] including managing the social environment.

Medication

[edit]A number of medications have been approved for the treatment of substance abuse.[62] These include replacement therapies such as buprenorphine and methadone as well as antagonist medications like disulfiram and naltrexone in either short acting, or the newer long acting form. Several other medications, often ones originally used in other contexts, have also been shown to be effective including bupropion and modafinil. Methadone and buprenorphine are sometimes used to treat opiate addiction.[63] These drugs are used as substitutes for other opioids and still cause withdrawal symptoms but they facilitate the tapering off process in a controlled fashion. When a person goes from using fentanyl every day, to not using it at all, they will experience a point where they need to get used to not using the substance. This is called withdrawal.[citation needed]

Antipsychotic medications have not been found to be useful.[64] Acamprostate[65] is a glutamatergic NMDA antagonist, which helps with alcohol withdrawal symptoms because alcohol withdrawal is associated with a hyperglutamatergic system.

Heroin-assisted treatment

[edit]

Three countries in Europe have active HAT programs, namely England, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Despite critical voices by conservative think-tanks with regard to these harm-reduction strategies, significant progress in the reduction of drug-related deaths has been achieved in those countries. For example, the US, devoid of such measures, has seen large increases in drug-related deaths since 2000 (mostly related to heroin use), while Switzerland has seen large decreases. In 2018, approximately 60,000 people have died of drug overdoses in America, while in the same time period, Switzerland's drug deaths were at 260. Relative to the population of these countries, the US has 10 times more drug-related deaths compared to the Swiss Confederation, which in effect illustrates the efficacy of HAT to reduce fatal outcomes in opiate/opioid addiction.[66][67]

Dual diagnosis

[edit]It is common for individuals with drugs use disorder to have other psychological problems.[68] The terms "dual diagnosis" or "co-occurring disorders", refer to having a mental health and substance use disorder at the same time. According to the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP), "symptoms of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety and psychosis are the rule rather than the exception in patients misusing drugs and/or alcohol."[69]

Individuals who have a comorbid psychological disorder often have a poor prognosis if either disorder is untreated.[68] Historically most individuals with dual diagnosis either received treatment only for one of their disorders or they did not receive any treatment all. However, since the 1980s, there has been a push towards integrating mental health and addiction treatment. In this method, neither condition is considered primary and both are treated simultaneously by the same provider.[69]

Epidemiology

[edit]

The initiation of drug use including alcohol is most likely to occur during adolescence, and some experimentation with substances by older adolescents is common. For example, results from 2010 Monitoring the Future survey, a nationwide study on rates of substance use in the United States, show that 48.2% of 12th graders report having used an illicit drug at some point in their lives.[70] In the 30 days prior to the survey, 41.2% of 12th graders had consumed alcohol and 19.2% of 12th graders had smoked tobacco cigarettes.[70] In 2009 in the United States about 21% of high school students have taken prescription drugs without a prescription.[71] And earlier in 2002, the World Health Organization estimated that around 140 million people were alcohol dependent and another 400 million with alcohol-related problems.[72]

Studies have shown that the large majority of adolescents will phase out of drug use before it becomes problematic. Thus, although rates of overall use are high, the percentage of adolescents who meet criteria for substance abuse is significantly lower (close to 5%).[73] According to UN estimates, there are "more than 50 million regular users of morphine diacetate (heroin), cocaine and synthetic drugs".[74]

More than 70,200 Americans died from drug overdoses in 2017.[67] Among these, the sharpest increase occurred among deaths related to fentanyl and synthetic opioids (28,466 deaths).[67] See charts below.

-

Drug use is higher in countries with high economic inequality.

-

Total recorded alcohol per capita consumption (15+), in litres of pure alcohol[75]

-

Total yearly U.S. drug deaths[76]

-

U.S. yearly overdose deaths, and the drugs involved[67]

History

[edit]APA, AMA, and NCDA

[edit]In 1966, the American Medical Association's Committee on Alcoholism with Addiction defined abuse of stimulants (amphetamines, primarily) in terms of 'medical supervision':

...'use' refers to the proper place of stimulants in medical practice; 'misuse' applies to the physician's role in initiating a potentially dangerous course of therapy; and 'abuse' refers to self-administration of these drugs without medical supervision and particularly in large doses that may lead to psychological dependency, tolerance and abnormal behavior.

In 1972, the American Psychiatric Association created a definition that used legality, social acceptability, and cultural familiarity as qualifying factors:

...as a general rule, we reserve the term drug abuse to apply to the illegal, nonmedical use of a limited number of substances, most of them drugs, which have properties of altering the mental state in ways that are considered by social norms and defined by statute to be inappropriate, undesirable, harmful, threatening, or, at minimum, culture-alien.[77]

In 1973, the National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse stated:

...drug abuse may refer to any type of drug or chemical without regard to its pharmacologic actions. It is an eclectic concept having only one uniform connotation: societal disapproval. ... The Commission believes that the term drug abuse must be deleted from official pronouncements and public policy dialogue. The term has no functional utility and has become no more than an arbitrary codeword for that drug use which is presently considered wrong.[78]

DSM

[edit]The first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (published in 1952) grouped alcohol and other drug abuse under "sociopathic personality disturbances", which were thought to be symptoms of deeper psychological disorders or moral weakness.[79] The third edition, published in 1980, was the first to recognize substance abuse (including drug abuse) and substance dependence as conditions separate from substance abuse alone, bringing in social and cultural factors. The definition of dependence emphasised tolerance to drugs, and withdrawal from them as key components to diagnosis, whereas abuse was defined as "problematic use with social or occupational impairment" but without withdrawal or tolerance.

In 1987, the DSM-IIIR category "psychoactive substance abuse", which includes former concepts of drug abuse is defined as "a maladaptive pattern of use indicated by...continued use despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent social, occupational, psychological or physical problem that is caused or exacerbated by the use (or by) recurrent use in situations in which it is physically hazardous". It is a residual category, with dependence taking precedence when applicable. It was the first definition to give equal weight to behavioural and physiological factors in diagnosis. By 1988, the DSM-IV defined substance dependence as "a syndrome involving compulsive use, with or without tolerance and withdrawal"; whereas substance abuse is "problematic use without compulsive use, significant tolerance, or withdrawal". Substance abuse can be harmful to health and may even be deadly in certain scenarios. By 1994, the fourth edition of the DSM issued by the American Psychiatric Association, the DSM-IV-TR, defined substance dependence as "when an individual persists in use of alcohol or other drugs despite problems related to use of the substance, substance dependence may be diagnosed", along with criteria for the diagnosis.[80]

The DSM-IV-TR defines substance abuse as:[81]

- A. A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

- Recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (e.g., repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use; substance-related absences, suspensions or expulsions from school; neglect of children or household)

- Recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (e.g., driving an automobile or operating a machine when impaired by substance use)

- Recurrent substance-related legal problems (e.g., arrests for substance-related disorderly conduct)

- Continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance (e.g., arguments with spouse about consequences of intoxication, physical fights)

- the symptoms have never met the criteria for substance dependence for this class of substance

The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5), was released in 2013, and it revisited this terminology. The principal change was a transition from the abuse-dependence terminology. In the DSM-IV era, abuse was seen as an early form or less hazardous form of the disease characterized with the dependence criteria. However, the APA's dependence term does not mean that physiologic dependence is present but rather means that a disease state is present, one that most would likely refer to as an addicted state. Many involved recognize that the terminology has often led to confusion, both within the medical community and with the general public. The American Psychiatric Association requested input as to how the terminology of this illness should be altered as it moves forward with DSM-5 discussions.[82] In the DSM-5, substance abuse and substance dependence have been merged into the category of substance use disorders and they no longer exist as individual concepts. While substance abuse and dependence were either present or not, substance use disorder has three levels of severity: mild, moderate and severe.[83]

Society and culture

[edit]Legal approaches

[edit]- Related articles: Drug control law, Prohibition (drugs), Arguments for and against drug prohibition, Harm reduction

Most governments have designed legislation to criminalize certain types of drug use. These drugs are often called "illegal drugs" but generally what is illegal is their unlicensed production, distribution, and possession. These drugs are also called "controlled substances". Even for simple possession, legal punishment can be quite severe (including the death penalty in some countries). Laws vary across countries, and even within them, and have fluctuated widely throughout history.

Attempts by government-sponsored drug control policy to interdict drug supply and eliminate drug abuse have been largely unsuccessful. In spite of the huge efforts by the U.S., drug supply and purity has reached an all-time high, with the vast majority of resources spent on interdiction and law enforcement instead of public health.[84][85] In the United States, the number of nonviolent drug offenders in prison exceeds by 100,000 the total incarcerated population in the EU, despite the fact that the EU has 100 million more citizens.[86]

Despite drug legislation (or perhaps because of it), large, organized criminal drug cartels operate worldwide. Advocates of decriminalization argue that drug prohibition makes drug dealing a lucrative business, leading to much of the associated criminal activity.

Some states in the U.S., as of late, have focused on facilitating safe use as opposed to eradicating it. For example, as of 2022, New Jersey has made the effort to expand needle exchange programs throughout the state, passing a bill through legislature that gives control over decisions regarding these types of programs to the state's department of health.[87] This state level bill is not only significant for New Jersey, as it could be used as a model for other states to possibly follow as well. This bill is partly a reaction to the issues occurring at local level city governments within the state of New Jersey as of late. One example of this is in the Atlantic City Government which came under lawsuit after they halted the enactment of said programs within their city.[88] This suit came a year before the passing of this bill, stemming from a local level decision to shut down related operations in Atlantic City made in July that same year. This lawsuit highlights the feelings of New Jersey residents, who had a great influence on this bill passing the legislature.[89] These feelings were demonstrated in front of Atlantic City City hall, where residents exclaimed their desire for these programs. All in all, the aforementioned bill was signed effectively into law just days after it passed legislature, by New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy.[90]

Cost

[edit]Policymakers try to understand the relative costs of drug-related interventions. An appropriate drug policy relies on the assessment of drug-related public expenditure based on a classification system where costs are properly identified.

Labelled drug-related expenditures are defined as the direct planned spending that reflects the voluntary engagement of the state in the field of illicit drugs. Direct public expenditures explicitly labeled as drug-related can be easily traced back by exhaustively reviewing official accountancy documents such as national budgets and year-end reports. Unlabelled expenditure refers to unplanned spending and is estimated through modeling techniques, based on a top-down budgetary procedure. Starting from overall aggregated expenditures, this procedure estimates the proportion causally attributable to substance abuse (Unlabelled Drug-related Expenditure = Overall Expenditure × Attributable Proportion). For example, to estimate the prison drug-related expenditures in a given country, two elements would be necessary: the overall prison expenditures in the country for a given period, and the attributable proportion of inmates due to drug-related issues. The product of the two will give a rough estimate that can be compared across different countries.[91]

Europe

[edit]As part of the reporting exercise corresponding to 2005, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction's network of national focal points set up in the 27 European Union (EU) the member states, Norway, and the candidates' countries to the EU, were requested to identify labeled drug-related public expenditure, at the national level.[91]

This was reported by 10 countries categorized according to the functions of government, amounting to a total of EUR 2.17 billion. Overall, the highest proportion of this total came within the government functions of health (66%) (e.g. medical services), and public order and safety (POS) (20%) (e.g. police services, law courts, prisons). By country, the average share of GDP was 0.023% for health, and 0.013% for POS. However, these shares varied considerably across countries, ranging from 0.00033% in Slovakia, up to 0.053% of GDP in Ireland in the case of health, and from 0.003% in Portugal, to 0.02% in the UK, in the case of POS; almost a 161-fold difference between the highest and the lowest countries for health, and a six-fold difference for POS.

To respond to these findings and to make a comprehensive assessment of drug-related public expenditure across countries, this study compared health and POS spending and GDP in the 10 reporting countries. Results suggest GDP to be a major determinant of the health and POS drug-related public expenditures of a country. Labeled drug-related public expenditure showed a positive association with the GDP across the countries considered: r = 0.81 in the case of health, and r = 0.91 for POS. The percentage change in health and POS expenditures due to a one percent increase in GDP (the income elasticity of demand) was estimated to be 1.78% and 1.23% respectively.

Being highly income elastic, health and POS expenditures can be considered luxury goods; as a nation becomes wealthier it openly spends proportionately more on drug-related health and public order and safety interventions.[91]

United Kingdom

[edit]The UK Home Office estimated that the social and economic cost of drug abuse[92] to the UK economy in terms of crime, absenteeism and sickness is in excess of £20 billion a year.[93] However, the UK Home Office does not estimate what portion of those crimes are unintended consequences of drug prohibition (crimes to sustain expensive drug consumption, risky production and dangerous distribution), nor what is the cost of enforcement. Those aspects are necessary for a full analysis of the economics of prohibition.[94]

United States

[edit]| Year | Cost (billions of dollars)[95] |

|---|---|

| 1992 | 107 |

| 1993 | 111 |

| 1994 | 117 |

| 1995 | 125 |

| 1996 | 130 |

| 1997 | 134 |

| 1998 | 140 |

| 1999 | 151 |

| 2000 | 161 |

| 2001 | 170 |

| 2002 | 181 |

These figures represent overall economic costs, which can be divided in three major components: health costs, productivity losses and non-health direct expenditures.

- Health-related costs were projected to total $16 billion in 2002.

- Productivity losses were estimated at $128.6 billion. In contrast to the other costs of drug abuse (which involve direct expenditures for goods and services), this value reflects a loss of potential resources: work in the labor market and in household production that was never performed, but could reasonably be expected to have been performed absent the impact of drug abuse.

- Included are estimated productivity losses due to premature death ($24.6 billion), drug abuse-related illness ($33.4 billion), incarceration ($39.0 billion), crime careers ($27.6 billion) and productivity losses of victims of crime ($1.8 billion).

- The non-health direct expenditures primarily concern costs associated with the criminal justice system and crime victim costs, but also include a modest level of expenses for administration of the social welfare system. The total for 2002 was estimated at $36.4 billion. The largest detailed component of these costs is for state and federal corrections at $14.2 billion, which is primarily for the operation of prisons. Another $9.8 billion was spent on state and local police protection, followed by $6.2 billion for federal supply reduction initiatives.

According to a report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Medicaid was billed for a significantly higher number of hospitals stays for opioid drug overuse than Medicare or private insurance in 1993. By 2012, the differences were diminished. Over the same time, Medicare had the most rapid growth in number of hospital stays.[96]

Canada

Substance abuse takes a financial toll on Canada's hospitals and the country as a whole. In the year 2011, around $267 million of hospital services were attributed to dealing with substance abuse problems.[97] The majority of these hospital costs in 2011 were related to issues with alcohol. Additionally, in 2014, Canada also allocated almost $45 million towards battling prescription drug abuse, extending into the year 2019.[98] Most of the financial decisions made on substance abuse in Canada can be attributed to the research conducted by the Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (CCSA) which conduct both extensive and specific reports. In fact, the CCSA is heavily responsible for identifying Canada's heavy issues with substance abuse. Some examples of reports by the CCSA include a 2013 report on drug use during pregnancy[99] and a 2015 report on adolescents' use of cannabis.[100]

Special populations

[edit]Immigrants and refugees

[edit]Immigrant and refugees have often been under great stress,[101] physical trauma and depression and anxiety due to separation from loved ones often characterize the pre-migration and transit phases, followed by "cultural dissonance", language barriers, racism, discrimination, economic adversity, overcrowding, social isolation, and loss of status and difficulty obtaining work and fears of deportation are common. Refugees frequently experience concerns about the health and safety of loved ones left behind and uncertainty regarding the possibility of returning to their country of origin.[102][103] For some, substance abuse functions as a coping mechanism to attempt to deal with these stressors.[103]

Immigrants and refugees may bring the substance use and abuse patterns and behaviors of their country of origin,[103] or adopt the attitudes, behaviors, and norms regarding substance use and abuse that exist within the dominant culture into which they are entering.[103][104]

Another factor that can contribute to substance abuse among immigrants is the lack of support that they receive. With few social and economic resources available to them, some turn to drugs as a way to cope through the stress that they are experiencing. When examining an assimilation model it can be concluded that as immigrants settle into their new environment and adapt to the new culture they are in, the amount as which they use begins to match those of their new environment. So in some cases, the amount in which one uses decreases as they adapt to their new society.[105]

Street children

[edit]Street children in many developing countries are a high-risk group for substance misuse, in particular solvent abuse.[106] Drawing on research in Kenya, Cottrell-Boyce argues that "drug use amongst street children is primarily functional—dulling the senses against the hardships of life on the street—but can also provide a link to the support structure of the 'street family' peer group as a potent symbol of shared experience."[107]

Musicians

[edit]In order to maintain high-quality performance, some musicians take chemical substances.[108] Some musicians take drugs such as alcohol to deal with the stress of performing. As a group they have a higher rate of substance abuse.[108] The most common chemical substance which is abused by pop musicians is cocaine,[108] because of its neurological effects. Stimulants like cocaine increase alertness and cause feelings of euphoria, and can therefore make the performer feel as though they in some ways 'own the stage'. One way in which substance abuse is harmful for a performer (musicians especially) is if the substance being abused is aspirated. The lungs are an important organ used by singers, and addiction to cigarettes may seriously harm the quality of their performance.[108] Smoking harms the alveoli, which are responsible for absorbing oxygen.

Veterans

[edit]Substance abuse can be a factor that affects the physical and mental health of veterans. Substance abuse may also harm personal and familial relationships, leading to financial difficulty. There is evidence to suggest that substance abuse disproportionately affects the homeless veteran population. A 2015 Florida study, which compared causes of homelessness between veterans and non-veteran populations in a self-reporting questionnaire, found that 17.8% of the homeless veteran participants attributed their homelessness to alcohol and other drug-related problems compared to just 3.7% of the non-veteran homeless group.[109]

A 2003 study found that homelessness was correlated with access to support from family/friends and services. However, this correlation was not true when comparing homeless participants who had a current substance-use disorders.[110] The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs provides a summary of treatment options for veterans with substance-use disorder. For treatments that do not involve medication, they offer therapeutic options that focus on finding outside support groups and "looking at how substance use problems may relate to other problems such as PTSD and depression".[111]

Sex and gender

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

|

| Biology |

| Medicine and health |

| Neuroscience and psychology |

| Sociology and society |

There are many sex differences in substance abuse.[112][113][114] Men and women express differences in the short- and long-term effects of substance abuse. These differences can be credited to sexual dimorphisms in the brain, endocrine and metabolic systems. Social and environmental factors that tend to disproportionately affect women, such as child and elder care and the risk of exposure to violence, are also factors in the gender differences in substance abuse.[112] Women report having greater impairment in areas such as employment, family and social functioning when abusing substances but have a similar response to treatment. Co-occurring psychiatric disorders are more common among women than men who abuse substances; women more frequently use substances to reduce the negative effects of these co-occurring disorders. Substance abuse puts both men and women at higher risk for perpetration and victimization of sexual violence.[112] Men tend to take drugs for the first time to be part of a group and fit in more so than women. At first interaction, women may experience more pleasure from drugs than men do. Women tend to progress more rapidly from first experience to addiction than men.[113] Physicians, psychiatrists and social workers have believed for decades that women escalate alcohol use more rapidly once they start. Once the addictive behavior is established for women they stabilize at higher doses of drugs than males do. When withdrawing from smoking women experience greater stress response. Males experience greater symptoms when withdrawing from alcohol.[113] There are gender differences when it comes to rehabilitation and relapse rates. For alcohol, relapse rates were very similar for men and women. For women, marriage and marital stress were risk factors for alcohol relapse. For men, being married lowered the risk of relapse.[114] This difference may be a result of gendered differences in excessive drinking. Alcoholic women are much more likely to be married to partners that drink excessively than are alcoholic men. As a result of this, men may be protected from relapse by marriage while women are at higher risk when married. However, women are less likely than men to experience relapse to substance use. When men experience a relapse to substance use, they more than likely had a positive experience prior to the relapse. On the other hand, when women relapse to substance use, they were more than likely affected by negative circumstances or interpersonal problems.[114]

See also

[edit]- ΔFosB

- Combined drug intoxication

- Drug addiction

- Handbook on Drug and Alcohol Abuse

- Harm reduction

- Hedonism

- International Day Against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking

- List of controlled drugs in the United Kingdom

- United States drug overdose death rates and totals over time

- List of deaths from drug overdose and intoxication

- Low-threshold treatment programs

- Needle-exchange programme

- Nihilism

- Poly drug use

- Polysubstance abuse

- Responsible drug use

- Supervised injection site

- Wellness check

References

[edit]- ^ Nutt DJ, King LA, Phillips LD (November 2010). "Drug harms in the UK: a multicriteria decision analysis". Lancet. 376 (9752): 1558–1565. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.690.1283. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61462-6. PMID 21036393. S2CID 5667719.

- ^ a b c United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (June 2012). World Drug Report 2012 (PDF). United Nations. ISBN 978-92-1-148267-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ a b "World Drug Report 2014" (PDF). Drugnet Europe. No. 87. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. July 2014. p. 4. ISSN 0873-5379. Catalogue Number TD-AA-14-003-EN-C. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018.

- ^ Data is from these saved tables from CDC Wonder at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. The tables have totals, rates, and US populations per year. The numbers are continually updated: "This dataset has been updated since this request was saved, which could lead to differences in results." So the numbers in the table at the source may be slightly different.

- 1968–1978 data: Compressed Mortality File 1968–1978. CDC WONDER Online Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd8.html

- 1979–1998 data: Compressed Mortality File 1979–1998. CDC WONDER On-line Database, compiled from Compressed Mortality File CMF 1968–1988, Series 20, No. 2A, 2000 and CMF 1989–1998, Series 20, No. 2E, 2003. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd9.html

- 1999–2020 data: Multiple Cause of Death, 1999–2020 Results. CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

- ^ Ksir, Oakley Ray; Charles (2002). Drugs, society, and human behavior (9th ed.). Boston [u.a.]: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-231963-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mosby's Medical, Nursing, & Allied Health Dictionary (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby. 2002. pp. 552, 2109. ISBN 978-0-323-01430-4. OCLC 48535206..

- ^ Laureen Veevers (1 October 2006). "'Shared banknote' health warning to cocaine users". The Observer. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ^ "Addiction is a Chronic Disease". Archived from the original on 24 June 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Abuse, National Institute on Drug (2018-06-06). "Understanding Drug Use and Addiction DrugFacts | National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)". nida.nih.gov. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ a b GBD 2015 (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". The Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ GBD 2013 (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". The Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "A Public Health Approach" (PDF). Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831. S2CID 5903121.

- ^ Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Fifth ed.). American Psychiatric Association. 2013. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-89042-557-2.

- ^ Fehrman, Elaine; Muhammad, Awaz K.; Mirkes, Evgeny M.; Egan, Vincent; Gorban, Alexander N. (2017). "The Five Factor Model of Personality and Evaluation of Drug Consumption Risk". In Palumbo, Francesco; Montanari, Angela; Vichi, Maurizio (eds.). Data Science. Studies in Classification, Data Analysis, and Knowledge Organization. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 231–242. arXiv:1506.06297. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55723-6_18. ISBN 978-3-319-55722-9. S2CID 45897076.

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (1999). Synthetic Panics: The Symbolic Politics of Designer Drugs. New York: New York University Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-8147-4244-0. OCLC 45733635.

- ^ a b Fehrman, Elaine; Egan, Vincent; Gorban, Alexander N.; Levesley, Jeremy; Mirkes, Evgeny M.; Muhammad, Awaz K. (2019). Personality Traits and Drug Consumption. A Story Told by Data. Springer, Cham. arXiv:2001.06520. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-10442-9. ISBN 978-3-030-10441-2. S2CID 151160405.

- ^ Barrett SP, Meisner JR, Stewart SH (November 2008). "What constitutes prescription drug misuse? Problems and pitfalls of current conceptualizations" (PDF). Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 1 (3): 255–62. doi:10.2174/1874473710801030255. PMID 19630724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-15.

- ^ McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Teter CJ (June 2009). "Subtypes of nonmedical prescription drug misuse". Drug Alcohol Depend. 102 (1–3): 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.007. PMC 2975029. PMID 19278795.

- ^ Antai-Otong, D. (2008). Psychiatric Nursing: Biological & Behavioral Concepts (2nd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning. ISBN 978-1-4180-3872-4. OCLC 173182624.

- ^ "The Prescription Drug Abuse Epidemic". PDMP Center of Excellence. 2010–2013.

- ^ "Topics in Brief: Prescription Drug Abuse". National Institute on Drug Abuse. December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014.

- ^ 宋, 建燮 (2020-05-30). "A Study on the Communication Index and Efficiency Evaluation of Regional Governments: Application of DEA, SEM, Super-SBM Models". National Association of Korean Local Government Studies. 22 (1): 21–49. doi:10.38134/klgr.2020.22.1.021. ISSN 1598-0960. S2CID 225870603.

- ^ a b c "Vaping popular among teens; opioid misuse at historic lows". National Institute on Drug Abuse. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ^ Westgate, Aubrey (22 May 2012). "Combating Prescription Drug Abuse in Your Practice". Physicians Practice. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012.

- ^ Burke PJ, O'Sullivan J, Vaughan BL (November 2005). "Adolescent substance use: brief interventions by emergency care providers". Pediatr Emerg Care. 21 (11): 770–6. doi:10.1097/01.pec.0000186435.66838.b3. PMID 16280955. S2CID 36410538.

- ^ Serafini G, Innamorati M, Dominici G, Ferracuti S, Kotzalidis GD, Serra G (April 2010). "Suicidal Behavior and Alcohol Abuse". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 7 (4). International Journal Environmental Research and Public Health: 1392–1431. doi:10.3390/ijerph7041392. PMC 2872355. PMID 20617037.

- ^ O'Connor, Rory; Sheehy, Noel (29 January 2000). Understanding suicidal behaviour. Leicester: BPS Books. pp. 33–36. ISBN 978-1-85433-290-5.

- ^ Isralowitz, Richard (2004). Drug use: a reference handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 122–123. ISBN 978-1-57607-708-5.

- ^ "SUBSTANCE ABUSE & HEALTH RISKS". University of Miami. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013.

- ^ "High-strength skunk 'now dominates' UK cannabis market". nhs.uk. 28 February 2018. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Di Forti M, Marconi A, Carra E, Fraietta S, Trotta A, Bonomo M, Bianconi F, Gardner-Sood P, O'Connor J, Russo M, Stilo SA, Marques TR, Mondelli V, Dazzan P, Pariante C, David AS, Gaughran F, Atakan Z, Iyegbe C, Powell J, Morgan C, Lynskey M, Murray RM (2015). "Proportion of patients in south London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: a case-control study" (PDF). Lancet Psychiatry. 2 (3): 233–8. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00117-5. PMID 26359901.

- ^ Marta Di Forti (17 December 2013). "Daily Use, Especially of High-Potency Cannabis, Drives the Earlier Onset of Psychosis in Cannabis Users". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 40 (6): 1509–1517. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbt181. PMC 4193693. PMID 24345517.

- ^ Evans, Katie; Sullivan, Michael J. (1 March 2001). Dual Diagnosis: Counseling the Mentally Ill Substance Abuser (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-57230-446-8.

- ^ a b Hampton WH, Hanik I, Olson IR (2019). "[Substance Abuse and White Matter: Findings, Limitations, and Future of Diffusion Tensor Imaging Research]". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 197 (4): 288–298. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.005. PMC 6440853. PMID 30875650.

Given that our the central nervous system is an intricately balanced, complex network of billions of neurons and supporting cells, some might imagine that extrinsic substances could cause irreversible brain damage. Our review paints a less gloomy picture of the substances reviewed, however. Following prolonged abstinence, abusers of alcohol (Pfefferbaum et al., 2014) or opiates (Wang et al., 2011) have white matter microstructure that is not significantly different from non-users. There was also no evidence that the white matter microstructural changes observed in longitudinal studies of cannabis, nicotine, or cocaine were completely irreparable. It is therefore possible that, at least to some degree, abstinence can reverse effects of substance abuse on white matter. The ability of white matter to "bounce back" very likely depends on the level and duration of abuse, as well as the substance being abused.

- ^ VandenBos, G. R. (2007). APA Dictionary of Psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. p. 470. ISBN 978-1-59147-380-0.

- ^ a b Moeller, F. Gerard; Barratt, Ernest S.; Dougherty, Donald M.; Schmitz, Joy M.; Swann, Alan C. (November 2001). "Psychiatric Aspects of Impulsivity". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (11): 1783–1793. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 11691682. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013.

- ^ Bishara AJ, Pleskac TJ, Fridberg DJ, Yechiam E, Lucas J, Busemeyer JR, Finn PR, Stout JC (2009). "Similar Processes Despite Divergent Behavior in Two Commonly Used Measures of Risky Decision Making". J Behav Decis Mak. 22 (4): 435–454. doi:10.1002/bdm.641. PMC 3152830. PMID 21836771.

- ^ Kreek, Mary Jeanne; Nielsen, David A; Butelman, Eduardo R; LaForge, K Steven (26 October 2005). "Genetic influences on impulsivity, risk taking, stress responsivity and vulnerability to drug abuse and addiction". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (11): 1450–1457. doi:10.1038/nn1583. PMID 16251987. S2CID 12589277.

- ^ Chambers RA, Taylor JR, Potenza MN (2003). "Developmental neurocircuitry of motivation in adolescence: a critical period of addiction vulnerability". Am J Psychiatry. 160 (6): 1041–52. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.6.1041. PMC 2919168. PMID 12777258.

- ^ Jeronimus B.F.; Kotov, R.; Riese, H.; Ormel, J. (2016). "Neuroticism's prospective association with mental disorders halves after adjustment for baseline symptoms and psychiatric history, but the adjusted association hardly decays with time: a meta-analysis on 59 longitudinal/prospective studies with 443 313 participants". Psychological Medicine. 46 (14): 2883–2906. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001653. PMID 27523506. S2CID 23548727.

- ^ a b Treatment, Center for Substance Abuse (1997). Chapter 2—Screening for Substance Use Disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US).

- ^ Soltanifar, Mohsen; Lee, Chel Hee (2025). "CMHSU: An R Statistical Software Package to Detect Mental Health Status, Substance Use Status, and Their Concurrent Status in the North American Healthcare Administrative Databases". Psychiatry International. 6 (2): 50. arXiv:2501.06435. doi:10.3390/psychiatryint6020050. ISSN 2673-5318.

- ^ Knight JR, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G (2002). "Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients". JAMA Pediatrics. 156 (6): 607–614. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. PMID 12038895.

- ^ Dhalla S, Kopec JA (2007). "The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: a review of reliability and validity studies". Clinical and Investigative Medicine. 30 (1): 33–41. doi:10.25011/cim.v30i1.447. PMID 17716538.

- ^ Morse, Barbara (1997). Screening for Substance Abuse During Pregnancy: Improving Care, Improving Health (PDF). pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-1-57285-042-2.

- ^ O'Donohue, W; K.E. Ferguson (2006). "Evidence-Based Practice in Psychology and Behavior Analysis". The Behavior Analyst Today. 7 (3): 335–350. doi:10.1037/h0100155. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ Chambless, D.L.; et al. (1998). "An update on empirically validated therapies" (PDF). Clinical Psychology. 49: 5–14. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "NIH Senior Health "Build With You in Mind": Survey". nihseniorhealth.gov. Archived from the original on 2015-08-11. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ^ "Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies – What is CBT?". Archived from the original on 2010-04-21.

- ^ "Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies – What is Family Therapy?". Archived from the original on 2010-06-13.

- ^ a b Hogue, A; Henderson, CE; Ozechowski, TJ; Robbins, MS (2014). "Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use: updates and recommendations 2007–2013". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 43 (5): 695–720. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.915550. PMID 24926870. S2CID 10036629.

- ^ "Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies – Treatment for Substance Use Disorders". Archived from the original on 2010-04-21.

- ^ Engle, Bretton; Macgowan, Mark J. (2009-08-05). "A Critical Review of Adolescent Substance Abuse Group Treatments". Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 6 (3): 217–243. doi:10.1080/15433710802686971. ISSN 1543-3714. PMID 20183675. S2CID 3293758.

- ^ a b "Maternal substance use and integrated treatment programs for women with substance abuse issues and their children: a meta-analysis". crd.york.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ^ Carney, Tara; Myers, Bronwyn J; Louw, Johann; Okwundu, Charles I (2016-01-20). "Brief school-based interventions and behavioural outcomes for substance-using adolescents". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1) CD008969. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008969.pub3. hdl:10019.1/104381. PMC 7119449. PMID 26787125.

- ^ Jensen, Chad D.; Cushing, Christopher C.; Aylward, Brandon S.; Craig, James T.; Sorell, Danielle M.; Steele, Ric G. (2011). "Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 79 (4): 433–440. doi:10.1037/a0023992. PMID 21728400. S2CID 19892519.

- ^ Barnett, Elizabeth; Sussman, Steve; Smith, Caitlin; Rohrbach, Louise A.; Spruijt-Metz, Donna (2012). "Motivational Interviewing for adolescent substance use: A review of the literature". Addictive Behaviors. 37 (12): 1325–1334. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.001. PMC 3496394. PMID 22958865.

- ^ "Self-Help Groups Article". Archived from the original on May 21, 2015. Retrieved May 27, 2015.

- ^ Uekermann J, Daum I (May 2008). "Social cognition in alcoholism: a link to prefrontal cortex dysfunction?". Addiction. 103 (5): 726–35. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02157.x. PMID 18412750.

- ^ Purvis G.; MacInnis D. M. (2009). "Implementation of the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA) in a Long-Standing Addictions Outpatient Clinic" (PDF). Journal of Behavior Analysis of Sports, Health, Fitness and Behavioral Medicine. 2: 133–44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-29.

- ^ "Current Pharmacological Treatment Available for Alchhol Abuse". The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse. 2006–2013.

- ^ Kalat, James W. (2013). Biological Psychology (11th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-111-83100-4. OCLC 772237089.

- ^ Maglione, M; Maher, AR; Hu, J; Wang, Z; Shanman, R; Shekelle, PG; Roth, B; Hilton, L; Suttorp, MJ; Ewing, BA; Motala, A; Perry, T (September 2011). "Off-Label Use of Atypical Antipsychotics: An Update [Internet]". Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 22132426. Report No.: 11-EHC087-EF.

- ^ Lingford-Hughes AR, Welch S, Peters L, Nutt DJ, British Association for Psychopharmacology, Expert Reviewers Group (2012-07-01). "BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7): 899–952. doi:10.1177/0269881112444324. ISSN 0269-8811. PMID 22628390.

- ^ "Drogentote". Swiss Health Observatory (OBSAN). Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Overdose Death Rates". National Institute on Drug Abuse. Archived from the original on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ^ a b Lingford-Hughes A. R.; Welch S.; Peters L.; Nutt D. J. (2012). "BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful use, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7): 899–952. doi:10.1177/0269881112444324. PMID 22628390. S2CID 30030790.

- ^ a b Peterson Ashley L (2013). "Integrating Mental Health and Addictions Services to Improve Client Outcomes". Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 34 (10): 752–756. doi:10.3109/01612840.2013.809830. PMID 24066651. S2CID 11537206.

- ^ a b Johnston, L. D.; O'Malley, P. M.; Bachman, J. G.; Schulenberg, J. E. (2011). "Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010" (PDF). Monitoring the Future. University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2022.

- ^ "CDC Newsroom Press Release June 3, 2010".

- ^ Barker, Philip J. (2003). Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The Craft of Caring. London: Arnold. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-340-81026-2. OCLC 53373798.

- ^ "Effective Child Therapy: Substance Abuse and Dependence". EffectiveChildTherapy. Archived from the original on 3 May 2013.

- ^ "The Global Drugs Trade". BBC News. 2000. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022.

- ^ Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004 (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. ISBN 978-92-4-156272-0. OCLC 60660748. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.]

- ^ Overdose Death Rates. By National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

- ^ Glasscote, Raymond M.; Sussex, James N.; Jaffe, Jerome H.; Ball, John; Brill, Leon (1972). The Treatment of Drug Abuse: Programs, Problems, Prospects (Report). Joint Information Service of the American Psychiatric Association and the National Association for Mental Health.

- ^ National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (March 1973). DRUG USE IN AMERICA – PROBLEM IN PERSPECTIVE (Report). p. 13. NCJ 9518. Archived from the original on 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Transformations: Substance Drug Abuse". Archived from the original on 2012-11-01. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ^ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV-TR (4th TR ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000. ISBN 978-0-89042-024-9. OCLC 43483668.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. Vol. 152 (4th ed.). Washington, DC. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.8.1228. ISBN 978-0-89042-061-4. ISSN 0002-953X. OCLC 29953039.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hasin, Deborah S.; O'Brien, Charles P.; Auriacombe, Marc; Borges, Guilherme; Bucholz, Kathleen; Budney, Alan; Compton, Wilson M.; Crowley, Thomas; Ling, Walter (2013-08-01). "DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorders: Recommendations and Rationale". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (8): 834–851. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12060782. ISSN 0002-953X. PMC 3767415. PMID 23903334.

- ^ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8. ISSN 0950-4125. OCLC 830807378.

- ^ Copeman M (April 2003). "Drug supply and drug abuse". CMAJ. 168 (9): 1113, author reply 1113. PMC 153673. PMID 12719309. Archived from the original on 2009-09-06.

- ^ Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, et al. (January 2003). "Impact of supply-side policies for control of illicit drugs in the face of the AIDS and overdose epidemics: investigation of a massive heroin seizure". CMAJ. 168 (2): 165–9. PMC 140425. PMID 12538544.

- ^ Bewley-Taylor, Dave; Hallam, Chris; Allen, Rob (March 2009). "The Incarceration of Drug Offenders: An Overview" (PDF). The Beckley Foundation Drug Policy Programme. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 June 2013.

- ^ Post, Michelle Brunetti (11 January 2022). "Bill to expand syringe access programs in NJ passes Legislature". The Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Shelly, Molly (29 September 2021). "South Jersey AIDS Alliance, residents file lawsuit to stop Atlantic City needle exchange closure". The Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021.

- ^ Shelly, Molly (6 July 2021). "Advocates gather to save Atlantic City needle exchange". The Press of Atlantic City. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Governor Murphy Signs Legislative Package to Expand Harm Reduction Efforts, Further Commitment to End New Jersey's Opioid Epidemic". Official Site of the State of New Jersey. 18 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Prieto L (2010). "Labelled drug-related public expenditure in relation to gross domestic product (gdp) in Europe: A luxury good?". Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 5 9. doi:10.1186/1747-597x-5-9. PMC 2881082. PMID 20478069.

- ^ "NHS and Drug Abuse". National Health Service (NHS). March 22, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ "Home Office — Tackling Drugs Changing Lives – Drugs in the workplace". 2007-06-09. Archived from the original on 2007-06-09. Retrieved 2016-09-19.

- ^ Thornton, Mark (31 July 2006). "The Economics of Prohibition".

- ^ "The Economic Costs of Drug Abuse in the United States 1992–2002" (PDF). Office of National Drug Control Policy, Executive Office of the President of the United States. December 2004. Publication 207303. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 September 2022.

- ^ Owens PL, Barrett ML, Weiss AJ, Washington RE, Kronick R (August 2014). "Hospital Inpatient Utilization Related to Opioid Overuse Among Adults, 1993–2012". HCUP Statistical Brief (177). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ^ Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse (20 November 2014). "Substance Abuse Costs Canadian Hospitals Hundreds of Millions of Dollars per Year – Alcohol Abuse the Prime Culprit". Canada Newswire. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020.

- ^ "CCSA Recognizes Federal Leadership on Prescription Drug Abuse". Indigenous Health Today. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020.

- ^ Finnegan, Loretta (2013). Licit and Illicit Drug Use during Pregnancy: Maternal, Neonatal and Early Childhood Consequences (PDF) (Report). Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. ISBN 978-1-77178-041-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 August 2021.

- ^ Tony, George; Vaccarino, Franco (2015). The Effects of Cannabis Use during Adolescence (PDF) (Report). Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. ISBN 978-1-77178-261-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2022.

- ^ Drachman, D. (1992). "A stage-of-migration framework for service to immigrant populations". Social Work. 37 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1093/sw/37.1.68.

- ^ Pumariega A. J.; Rothe E.; Pumariega J. B. (2005). "Mental health of immigrants and refugees". Community Mental Health Journal. 41 (5): 581–597. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.6034. doi:10.1007/s10597-005-6363-1. PMID 16142540. S2CID 7326036.

- ^ a b c d National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2005), "Module 10F: Immigrants, Refugees, and Alcohol" (PDF), NIAAA: Social work education for the prevention and treatment of alcohol use disorders, National Institutes of Health, 1 U24 AA11899-04, archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2006

- ^ Caetano R.; Clark C. L.; Tam T. (1998). "Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities: Theory and research". Journal of Alcohol, Health, and Research. 22 (4): 233–241.

- ^ "Alcohol and Drug Use Among Displaced Persons: An Overview | Office of Justice Programs". www.ojp.gov. Retrieved 2025-03-06.

- ^ "Understanding Substance Use Among Street Children" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ Cottrell-Boyce, Joe (2010). "The role of solvents in the lives of Kenyan street children: An ethnographic perspective" (PDF). African Journal of Drug & Alcohol Studies. 9 (2): 93–102. doi:10.4314/ajdas.v9i2.64142. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ a b c d Breitenfeld D.; Thaller V.; Perić B.; Jagetic N.; Hadžić D.; Breitenfeld T. (2008). "Substance abuse in performing musicians". Alcoholism: Journal on Alcoholism and Related Addictions. 44 (1): 37–42. ProQuest 622145760.

- ^ Dunne, Eugene M.; Burrell, Larry E.; Diggins, Allyson D.; Whitehead, Nicole Ennis; Latimer, William W. (2015). "Increased risk for substance use and health-related problems among homeless veterans: Homeless Veterans and Health Behaviors". The American Journal on Addictions. 24 (7): 676–680. doi:10.1111/ajad.12289. PMC 6941432. PMID 26359444.

- ^ Zlotnick, Cheryl; Tam, Tammy; Robertson, Marjorie J. (2003). "Disaffiliation, Substance Use, and Exiting Homelessness". Substance Use & Misuse. 38 (3–6): 577–599. doi:10.1081/JA-120017386. ISSN 1082-6084. PMID 12747398. S2CID 31815225.

- ^ "Treatment Programs for Substance Use Problems – Mental Health". mentalhealth.va.gov. Retrieved 2016-12-17.

- ^ a b c McHugh, R. Kathryn; Votaw, Victoria R.; Sugarman, Dawn E.; Greenfield, Shelly F. (2018-12-01). "Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders". Clinical Psychology Review. Gender and Mental Health. 66: 12–23. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012. ISSN 0272-7358. PMC 5945349. PMID 29174306.

- ^ a b c Becker, Jill B.; McClellan, Michele L.; Reed, Beth Glover (2016-11-07). "Sex differences, gender and addiction". Journal of Neuroscience Research. 95 (1–2): 136–147. doi:10.1002/jnr.23963. ISSN 0360-4012. PMC 5120656. PMID 27870394.

- ^ a b c Walitzer, Kimberly S.; Dearing, Ronda L. (2006-03-01). "Gender differences in alcohol and substance use relapse". Clinical Psychology Review. Relapse in the addictive behaviors. 26 (2): 128–148. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003. ISSN 0272-7358. PMID 16412541.

People overdose drugs to try to forget their problems at home, and some use them for fun because they saw people using drugs at television advertising them.

External links

[edit]- "The Science of Drug Use: A Resource for the Justice Sector". North Bethesda, Maryland: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 26 May 2020. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- School-Based Drug Abuse Prevention: Promising and Successful Programs (PDF). Ottawa, Ontario: Public Safety Canada. 31 January 2018. ISBN 978-1-100-12181-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- Adverse Childhood Experiences: Risk Factors for Substance Misuse and Mental Health. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019 – via YouTube. Dr. Robert Anda of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control describes the relation between childhood adversity and later ill-health, including substance abuse (video)

Substance abuse

View on GrokipediaSubstance use disorder is a chronic condition defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), as a problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, evidenced by at least two of eleven criteria—such as loss of control over use, tolerance, withdrawal, and persistent use despite adverse consequences—manifesting within a 12-month period.[1] This framework replaced earlier distinctions between substance abuse and dependence to reflect a dimensional severity spectrum rather than categorical diagnoses.[2] Affected substances include alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, stimulants, opioids, and sedatives, each capable of hijacking the brain's mesolimbic dopamine reward pathway, fostering compulsive seeking through neuroadaptations that prioritize short-term reinforcement over long-term harms.[3] Globally, substance use disorders afflict roughly 2.2% of the population, with alcohol use disorders comprising the largest share at 1.5%, while drug use disorders impact an estimated 39.5 million individuals as of 2021, though only one in five receives treatment.[4][5] These disorders contribute to substantial morbidity, including over 85,000 annual deaths from drug use alone in recent assessments, alongside profound economic tolls—such as $249 billion yearly in the United States from alcohol misuse and $193 billion from illicit drugs—encompassing healthcare expenditures, lost productivity, and criminal justice costs.[6][7] Empirical evidence points to multifactorial causation, including genetic factors with heritability estimates of 40-60%, neurobiological vulnerabilities in executive function circuits, and environmental contributors like early adversity and poor self-regulation, which interact to erode volitional control once use escalates beyond experimentation.[8][9] Defining characteristics include high relapse rates post-treatment, reflecting entrenched neural changes, and ongoing debates over etiological models—ranging from brain disease paradigms emphasizing compulsion to behavioral frameworks stressing agency and incentives—amid critiques of institutional biases in research that may overpathologize use while underemphasizing personal accountability.[10][11]

![Total recorded alcohol per capita consumption (15+), in litres of pure alcohol[75]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Alcohol_by_Country.png/500px-Alcohol_by_Country.png)

![Total yearly U.S. drug deaths[76]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1a/US_timeline._Number_of_overdose_deaths_from_all_drugs.jpg/330px-US_timeline._Number_of_overdose_deaths_from_all_drugs.jpg)

![U.S. yearly overdose deaths, and the drugs involved[67]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/US_timeline._Drugs_involved_in_overdose_deaths.jpg/330px-US_timeline._Drugs_involved_in_overdose_deaths.jpg)